Module 5: Choosing and Researching a Topic

Narrowing your topic, learning objectives.

Describe strategies for narrowing a topic.

Once you’ve selected a speech topic, your next step is to narrow it. Many beginning public speakers start with a topic that is much too broad and become overwhelmed. The problem with a broad topic is that you will not be able to adequately address it in the allotted time, you will spend unnecessary time researching it, and you will tend to only be able to present superficial details on a general topic. It is almost always more effective and interesting to speak in depth about a focused topic than to try to superficially cover a broad topic.

So, how do you narrow your topic? This section will outline three strategies for narrowing a topic:

- Inverted Pyramid

- Initial Research

Let’s say you’ve chosen to speak about yoga. That’s a great start, but is still too broad. Using the topic of yoga as an example, we’ll apply the three strategies to creating a focused, doable topic.

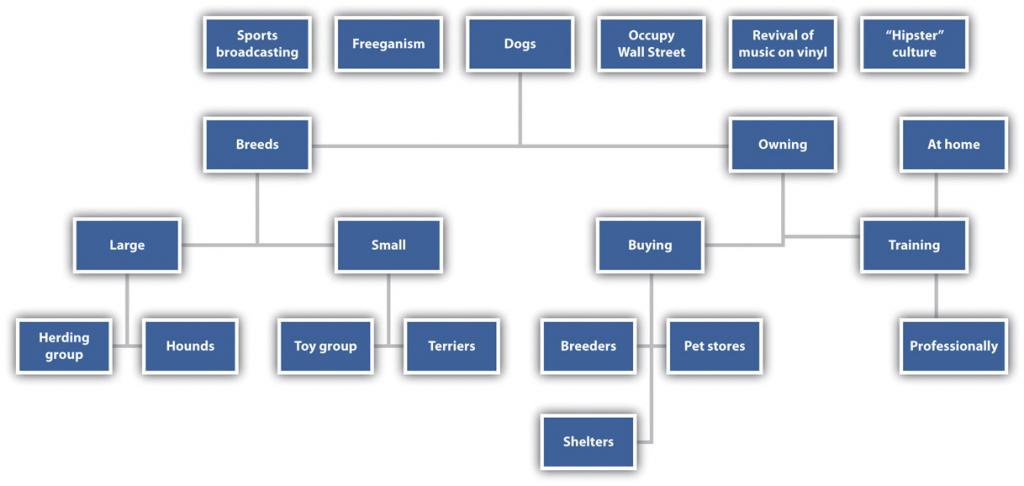

Clustering allows you to explore and identify related subtopics to your general topic. Write your general topic (“yoga”) in the center bubble on a piece of paper, then draw lines and more bubbles and fill those with a variety of related sub-topics. Some of these sub-topics will generate sub-sub and sub-sub-sub topics and so. on It might look something like this:

This student began to make a mind map about Yoga. At this stage in the process, the student is exploring the benefits of yoga to see if that would be a good way to narrow down the topic. It could narrow even further to “academic benefits,” for instance. This chart was generated with a free online tool called miro, at miro.com.

As you cluster, you will start to identify more focused topics that interest you and your audience. You will also be able to edit out topics that aren’t relevant to you and your audience.

The Inverted Pyramid is another visual technique where you start with your broad topic at the top, then make it more specific step-by-step. Each topic should be a sub-topic of the one above it, so your pyramid follows the same thread. As always, focus on areas of your topic that interest and relate to you and your audience. Your narrowed speech topic might be what you end up with at the bottom of your inverted pyramid, or part-way down. For instance, in the following illustration, you might ultimately decide on the speech topic of “How Yoga Practice Can Help College Students Manage Anxiety.”

A final strategy to narrow your speech topic is to explore your broad topic with initial research , which can take different forms. Using the topic of yoga, your research might include a conversation with your yoga instructor to find out what aspects of the practice might be most interesting and relevant for your audience. If you use social media, you might poll your friends and family about what aspects of your topic they are most curious about. A face-to face discussion with classmates, co-workers, friends, and family members about your topic is also a great option! Finally, use Internet search engines to read some articles and discover more about your topic. Since your audience for this class will be college students, adding the phrase “for college students” to your search query can be helpful for some topics. For instance, you might search “benefits of yoga for college students.” Initial research will help you identify more focused variations of your broad topic.

Clustering , Inverted Pyramid , and Initial Research are strategies that will help you take a broad topic and narrow it so it is manageable, is interesting, and allows you to go in-depth in your research and what you ultimately present to your audience.

- Narrowing Your Topic. Authored by : Susan Bagley-Koyle with Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

6.2 Selecting a Topic

Learning objectives.

- Understand the four primary constraints of topic selection.

- Demonstrate an understanding of how a topic is narrowed from a broad subject area to a manageable specific purpose.

Wonderlane – Fork in the road, decision tree – CC BY 2.0.

One of the most common stumbling blocks for novice public speakers is selecting their first speech topic. Generally, your public speaking instructor will provide you with some fairly specific parameters to make this a little easier. You may be assigned to tell about an event that has shaped your life or to demonstrate how to do something. Whatever your basic parameters, at some point you as the speaker will need to settle on a specific topic. In this section, we’re going to look at some common constraints of public speaking, picking a broad topic area, and narrowing your topic.

Common Constraints of Public Speaking

When we use the word “constraint” with regard to public speaking, we are referring to any limitation or restriction you may have as a speaker. Whether in a classroom situation or in the boardroom, speakers are typically given specific instructions that they must follow. These instructions constrain the speaker and limit what the speaker can say. For example, in the professional world of public speaking, speakers are often hired to speak about a specific topic (e.g., time management, customer satisfaction, entrepreneurship). In the workplace, a supervisor may assign a subordinate to present certain information in a meeting. In these kinds of situations, when a speaker is hired or assigned to talk about a specific topic, he or she cannot decide to talk about something else.

Furthermore, the speaker may have been asked to speak for an hour, only to show up and find out that the event is running behind schedule, so the speech must now be made in only thirty minutes. Having prepared sixty minutes of material, the speaker now has to determine what stays in the speech and what must go. In both of these instances, the speaker is constrained as to what he or she can say during a speech. Typically, we refer to four primary constraints: purpose, audience, context, and time frame.

The first major constraint someone can have involves the general purpose of the speech. As mentioned earlier, there are three general purposes: to inform, to persuade, and to entertain. If you’ve been told that you will be delivering an informative speech, you are automatically constrained from delivering a speech with the purpose of persuading or entertaining. In most public speaking classes, this is the first constraint students will come in contact with because generally teachers will tell you the exact purpose for each speech in the class.

The second major constraint that you need to consider as a speaker is the type of audience you will have. As discussed in the chapter on audience analysis, different audiences have different political, religious, and ideological leanings. As such, choosing a speech topic for an audience that has a specific mindset can be very tricky. Unfortunately, choosing what topics may or may not be appropriate for a given audience is based on generalizations about specific audiences. For example, maybe you’re going to give a speech at a local meeting of Democratic leaders. You may think that all Democrats are liberal or progressive, but there are many conservative Democrats as well. If you assume that all Democrats are liberal or progressive, you may end up offending your audience by making such a generalization without knowing better. Obviously, the best way to prevent yourself from picking a topic that is inappropriate for a specific audience is to really know your audience, which is why we recommend conducting an audience analysis, as described in Chapter 5 “Audience Analysis” .

The third major constraint relates to the context. For speaking purposes, the context of a speech is the set of circumstances surrounding a particular speech. There are countless different contexts in which we can find ourselves speaking: a classroom in college, a religious congregation, a corporate boardroom, a retirement village, or a political convention. In each of these different contexts, the expectations for a speaker are going to be unique and different. The topics that may be appropriate in front of a religious group may not be appropriate in the corporate boardroom. Topics appropriate for the corporate boardroom may not be appropriate at a political convention.

The last—but by no means least important—major constraint that you will face is the time frame of your speech. In speeches that are under ten minutes in length, you must narrowly focus a topic to one major idea. For example, in a ten-minute speech, you could not realistically hope to discuss the entire topic of the US Social Security program. There are countless books, research articles, websites, and other forms of media on the topic of Social Security, so trying to crystallize all that information into ten minutes is just not realistic.

Instead, narrow your topic to something that is more realistically manageable within your allotted time. You might choose to inform your audience about Social Security disability benefits, using one individual disabled person as an example. Or perhaps you could speak about the career of Robert J. Myers, one of the original architects of Social Security 1 . By focusing on information that can be covered within your time frame, you are more likely to accomplish your goal at the end of the speech.

Selecting a Broad Subject Area

Once you know what the basic constraints are for your speech, you can then start thinking about picking a topic. The first aspect to consider is what subject area you are interested in examining. A subject area is a broad area of knowledge. Art, business, history, physical sciences, social sciences, humanities, and education are all examples of subject areas. When selecting a topic, start by casting a broad net because it will help you limit and weed out topics quickly.

Furthermore, each of these broad subject areas has a range of subject areas beneath it. For example, if we take the subject area “art,” we can break it down further into broad categories like art history, art galleries, and how to create art. We can further break down these broad areas into even narrower subject areas (e.g., art history includes prehistoric art, Egyptian art, Grecian art, Roman art, Middle Eastern art, medieval art, Asian art, Renaissance art, modern art). As you can see, topic selection is a narrowing process.

Narrowing Your Topic

Narrowing your topic to something manageable for the constraints of your speech is something that takes time, patience, and experience. One of the biggest mistakes that new public speakers make is not narrowing their topics sufficiently given the constraints. In the previous section, we started demonstrating how the narrowing process works, but even in those examples, we narrowed subject areas down to fairly broad areas of knowledge.

Think of narrowing as a funnel. At the top of the funnel are the broad subject areas, and your goal is to narrow your topic further and further down until just one topic can come out the other end of the funnel. The more focused your topic is, the easier your speech is to research, write, and deliver. So let’s take one of the broad areas from the art subject area and keep narrowing it down to a manageable speech topic. For this example, let’s say that your general purpose is to inform, you are delivering the speech in class to your peers, and you have five to seven minutes. Now that we have the basic constraints, let’s start narrowing our topic. The broad area we are going to narrow in this example is Middle Eastern art. When examining the category of Middle Eastern art, the first thing you’ll find is that Middle Eastern art is generally grouped into four distinct categories: Anatolian, Arabian, Mesopotamian, and Syro-Palestinian. Again, if you’re like us, until we started doing some research on the topic, we had no idea that the historic art of the Middle East was grouped into these specific categories. We’ll select Anatolian art, or the art of what is now modern Turkey.

You may think that your topic is now sufficiently narrow, but even within the topic of Anatolian art, there are smaller categories: pre-Hittite, Hittite, Uratu, and Phrygian periods of art. So let’s narrow our topic again to the Phrygian period of art (1200–700 BCE). Although we have now selected a specific period of art history in Anatolia, we are still looking at a five-hundred-year period in which a great deal of art was created. One famous Phrygian king was King Midas, who according to myth was given the ears of a donkey and the power of a golden touch by the Greek gods. As such, there is an interesting array of art from the period of Midas and its Greek counterparts representing Midas. At this point, we could create a topic about how Phrygian and Grecian art differed in their portrayals of King Midas. We now have a topic that is unique, interesting, and definitely manageable in five to seven minutes. You may be wondering how we narrowed the topic down; we just started doing a little research using the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s website ( http://www.metmuseum.org ).

Overall, when narrowing your topic, you should start by asking yourself four basic questions based on the constraints discussed earlier in this section:

- Does the topic match my intended general purpose?

- Is the topic appropriate for my audience?

- Is the topic appropriate for the given speaking context?

- Can I reasonably hope to inform or persuade my audience in the time frame I have for the speech?

Key Takeaways

- Selecting a topic is a process. We often start by selecting a broad area of knowledge and then narrowing the topic to one that is manageable for a given rhetorical situation.

- When finalizing a specific purpose for your speech, always ask yourself four basic questions: (1) Does the topic match my intended general purpose?; (2) Is the topic appropriate for my audience?; (3) Is the topic appropriate for the given speaking context?; and (4) Can I reasonably hope to inform or persuade my audience in the time frame I have for the speech?

- Imagine you’ve been asked to present on a new technology to a local business. You’ve been given ten minutes to speak on the topic. Given these parameters, take yourself through the narrowing process from subject area (business) to a manageable specific purpose.

- Think about the next speech you’ll be giving in class. Show how you’ve gone from a large subject area to a manageable specific purpose based on the constraints given to you by your professor.

1 See, for example, Social Security Administration (1996). Robert J. Myers oral history interview. Retrieved from http://www.ssa.gov/history/myersorl.html

Stand up, Speak out Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1-Research Questions

2. Narrowing a Topic

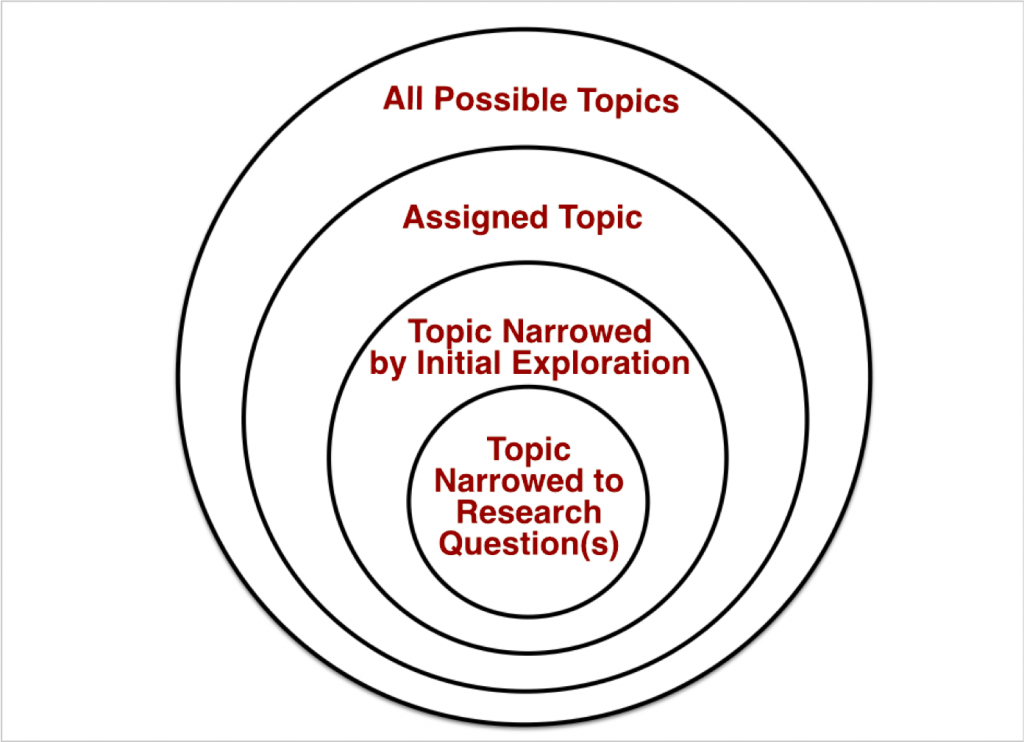

For many students, having to start with a research question is the biggest difference between how they did research in high school and how they are required to carry out their college research projects. It’s a process of working from the outside in: you start with the world of all possible topics (or your assigned topic) and narrow down until you’ve focused your interest enough to be able to tell precisely what you want to find out, instead of only what you want to “write about.”

Process of Narrowing a Topic

All Possible Topics -You’ll need to narrow your topic in order to do research effectively. Without specific areas of focus, it will be hard to even know where to begin.

Assigned Topics – When professors assign a topic you have to narrow, they have already started the narrowing process. Narrowing a topic means making some part of it more specific. Ideas about a narrower topic can come from anywhere. Often, a narrower topic boils down to deciding what’s interesting to you. One way to get ideas is to read background information from a source like Wikipedia.

Topic Narrowed by Initial Exploration – It’s wise to do some more reading about that narrower topic to a) learn more about it and b) learn specialized terms used by professionals and scholars who study it.

Topic Narrowed to Research Question(s) – A research question defines exactly what you are trying to find out. It will influence most of the steps you take to conduct the research.

ACTIVITY: Which Topic Is Narrower?

When we talk about narrowing a topic, we’re talking about making it more specific. You can make it more specific by singling out at least one part or aspect of the original to decrease the scope of the original. Now here’s some practice for you to test your understanding.

Why Narrow a Topic?

Once you have a need for research—say, an assignment—you may need to prowl around a bit online to explore the topic and figure out what you actually want to find out and write about.

For instance, maybe your assignment is to develop a poster about the season “spring” for an introductory horticulture course. The instructor expects you to narrow that topic to something you are interested in and that is related to your class.

Ideas about a narrower topic can come from anywhere. In this case, a narrower topic boils down to deciding what’s interesting to you about “spring” that is related to what you’re learning in your horticulture class and small enough to manage in the time you have.

One way to get ideas would be to read about spring in Wikipedia, looking for things that seem interesting and relevant to your class, and then letting one thing lead to another as you keep reading and thinking about likely possibilities that are more narrow than the enormous “spring” topic. (Be sure to pay attention to the references at the bottom of most Wikipedia pages and pursue any that look interesting. Your instructor is not likely to let you cite Wikipedia, but those references may be citable scholarly sources that you could eventually decide to use.)

Or, instead, if it is spring at the time you could start by just looking around, admire the blooming trees on campus, and decide you’d like your poster to be about bud development on your favorites, the crabapple trees.

What you’re actually doing to narrow your topic is making at least one aspect of your topic more specific. For instance, assume your topic is the maintenance of the 130 miles of sidewalks on OSU’s Columbus campus. If you made maintenance more specific, your narrower topic might be snow removal on Columbus OSU’s sidewalks. If instead, you made the 130 miles of sidewalks more specific, your narrower topic might be maintenance of the sidewalks on all sides of Mirror Lake.

Anna Narrows Her Topic and Works on a Research Question

The Situation: Anna, an undergraduate, has been assigned a research paper on Antarctica. Her professor expects students to (1) narrow the topic on something more specific about Antarctica because they won’t have time to cover that whole topic. Then they are to (2) come up with a research question that their paper will answer.

The professor explained that the research question should be something they are interested in answering and that it must be more complicated than what they could answer with a quick Google search. He also said that research questions often, but not always, start with either the word “how” or “why.”

What you should do:

- Read what Anna is thinking below as she tries to do the assignment.

- After the reading, answer the questions at the end of the monologue in your own mind.

- Check your answers with ours at the end of Anna’s interior monologue.

- Keep this demonstration in mind the next time you are in Anna’s spot, and you can mimic her actions and think about your own topic.

Anna’s Interior Monologue

Okay, I am going to have to write something—a research paper—about Antarctica. I don’t know anything about that place—I think it’s a continent. I can’t think of a single thing I’ve ever wanted to know about Antarctica. How will I come up with a research question about that place? Calls for Wikipedia, I guess.

At https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antarctica . Just skimming. Pretty boring stuff. Oh, look– Antarctica’s a desert! I guess “desert” doesn’t have to do with heat. That’s interesting. What else could it have to do with? Maybe lack of precipitation? But there’s lots of snow and ice there. Have to think about that—what makes a desert a desert?

It says one to five thousand people live there in research stations. Year-round. Definitely, the last thing I’d ever do. “…there is no evidence that it was seen by humans until the 19th century.” I never thought about whether anybody lived in Antarctica first, before the scientists and stuff.

Lots of names—explorer, explorer… boring. It says Amundson reached the South Pole first. Who’s Amundson? But wait. It says, “One month later, the doomed Scott Expedition reached the pole.” Doomed? Doomed is always interesting. Where’s more about the Scott Expedition? I’m going to use that Control-F technique and type in Scott to see if I can find more about him on this page. Nothing beyond that one sentence shows up. Why would they have just that one sentence? I’ll have to click on the Scott Expedition link.

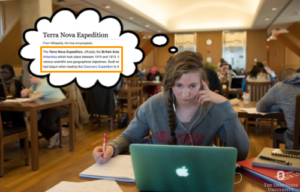

But it gives me a page called Terra Nova Expedition. What does that have to do with Scott? And just who was Scott? And why was his expedition doomed? There he is in a photo before going to Antarctica. Guess he was English. Other photos show him and his team in the snow. Oh, the expedition was named Terra Nova after the ship they sailed this time—in 1911. Scott had been there earlier on another ship.

Lots of stuff about preparing for the trip. Then stuff about expedition journeys once they were in Antarctica. Not very exciting—nothing about being doomed. I don’t want to write about this stuff.

Wait. The last paragraph of the first section says “For many years after his death, Scott’s status as a tragic hero was unchallenged,” but then it says that in the 20th-century people looked closer at the expedition’s management and at whether Scott and some of his team could be personally blamed for the catastrophe. That “remains controversial,” it says. Catastrophe? Personally blamed? Hmm.

Back to skimming. It all seems horrible to me. They actually planned to kill their ponies for meat, so when they actually did it, it was no surprise. Everything was extremely difficult. And then when they arrived at the South Pole, they found that the explorer Amundsen had beaten them. Must have been a big disappointment.

The homeward march was even worse. The weather got worse. The dog sleds that were supposed to meet them periodically with supplies didn’t show up. Or maybe the Scott group was lost and didn’t go to the right meeting places. Maybe that’s what that earlier statement meant about whether the decisions that were made were good ones. Scott’s diary said the crystallized snow made it seem like they were pushing and pulling the sledges through dry sand .

It says that before things turned really bad ( really bad? You’ve already had to eat your horses !), Scott allowed his men to put 30 pounds of rocks with fossils on the sledges they were pushing and dragging. Now was that sensible? The men had to push or pull those sledges themselves. What if it was those rocks that actually doomed those men?

But here it says that those rocks are the proof of continental drift. So how did they know those rocks were so important? Was that knowledge worth their lives? Could they have known?

Wow–there is drama on this page! Scott’s diary is quoted about their troubles on the expedition—the relentless cold, frostbite, and the deaths of their dogs. One entry tells of a guy on Scott’s team “now with hands as well as feet pretty well useless” voluntarily leaving the tent and walking to his death. The diary says that the team member’s last words were ”I am just going outside and may be some time.” Ha!

They all seem lost and desperate but still have those sledges. Why would you keep pulling and pushing those sledges containing an extra 30 pounds of rock when you are so desperate and every step is life or death?

Then there’s Scott’s last diary entry, on March 29, 1912. “… It seems a pity but I do not think I can write more.” Well.

That diary apparently gave lots of locations of where he thought they were but maybe they were lost. It says they ended up only 11 miles from one of their supply stations. I wonder if anybody knows how close they were to where Scott thought they were.

I’d love to see that diary. Wouldn’t that be cool? Online? I’ll Google it.

Yes! At the British museum. Look at that! I can see Scott’s last entry IN HIS OWN HANDWRITING!

Actually, if I decide to write about something that requires reading the diary, it would be easier to not have to decipher his handwriting. Wonder whether there is a typed version of it online somewhere?

Maybe I should pay attention to the early paragraph on the Terra Nova Expedition page in Wikipedia—about it being controversial whether Scott and his team made bad decisions so that they brought most of their troubles on themselves. Can I narrow my topic to just the controversy over whether bad decisions of Scott and his crew doomed them? Maybe it’s too big a topic if I consider the decisions of all team members. Maybe I should just consider Scott’s decisions.

So what research question could come from that? Maybe: how did Scott’s decisions contribute to his team’s deaths in Antarctica? But am I talking about his decisions before or after they left for Antarctica? Or the whole time they were a team? Probably too many decisions involved. More focused: How did Scott’s decisions after reaching the South Pole help or hurt the chances of his team getting back safely? That’s not bad—maybe. If people have written about that. There are several of his decisions discussed on the Wikipedia page, and I know there are sources at the bottom of that page.

Let me think—what else did I see that was interesting or puzzling about all this? I remember being surprised that Antarctica is a desert. So maybe I could make Antarctica as a desert my topic. My research question could be something like: Why is Antarctica considered a desert? But there has to be a definition of deserts somewhere online, so that doesn’t sound complicated enough. Once you know the definition of desert, you’d know the answer to the question. Professor Sanders says research questions are more complicated than regular questions.

What’s a topic I could care about? A question I really wonder about? Maybe those rocks with the fossils in them. It’s just so hard to imagine desperate explorers continuing to push those sledges with an extra 30 pounds of rocks on them. Did they somehow know how important they would be? Or were they just curious about them? Why didn’t they ditch them? Or maybe they just didn’t realize how close to death they were. Maybe I could narrow my Antarctica topic to those rocks.

Maybe my narrowed topic could be something like: The rocks that Scott and his crew found in Antarctica that prove continental drift. Maybe my research question could be: How did Scott’s explorers choose the rocks they kept?

Well, now all I have is questions about my questions. Like, is my professor going to think the question about the rocks is still about Antarctica? Or is it all about continental drift or geology or even the psychology of desperate people? And what has been written about the finding of those rocks? Will I be able to find enough sources? I’m also wondering whether my question about Scott’s decisions is too big—do I have enough time for it?

I think my professor is the only one who can tell me whether my question about the rocks has enough to do with Antarctica. Since he’s the one who will be grading my paper. But a librarian can help me figure out the other things.

So Dr. Sanders and a librarian are next.

Reflection Questions

- Was Anna’s choice to start with Wikipedia a good choice? Why or why not?

- Have you ever used that Control-F technique?

- At what points does Anna think about where to look for information?

- At the end of this session, Anna hasn’t yet settled on a research question. So what did she accomplish? What good was all this searching and thinking?

Our Answers:

- Was Anna’s choice to start with Wikipedia a good choice? Why or why not? Wikipedia is a great place to start a research project. Just make sure you move on from there, because it’s a not a good place to end up with your project. One place to move on to is the sources at the bottom of most Wikipedia pages.

- Have you ever used that Control-F technique? If you haven’t used the Control-F technique, we hope you will. It can save you a lot of time and effort reading online material.

- At what points does Anna think about where to look for information ? When she began; when she wanted to know more about the Scott expedition; when she wonders whether she could read Scott’s diary online; when she thinks about what people could answer her questions.

- At the end of this session, Anna hasn’t yet settled on a research question. So what did she accomplish? What good was all this reading and thinking? There are probably many answers to this question. Ours includes that Anna learned more about Antarctica, the subject of her research project. She focused her thinking (even if she doesn’t end up using the possible research questions she’s considering) and practiced critical thinking skills, such as when she thought about what she could be interested in, when she worked to make her potential research questions more specific, and when she figured out what questions still needed answering at the end. She also practiced her skills at making meaning from what she read, investigating a story that she didn’t expect to be there and didn’t know had the potential of being one that she is interested in. She also now knows what questions she needs answered and whom to ask. These thinking skills are what college is all about. Anna is way beyond where she was when she started.

Choosing & Using Sources: A Guide to Academic Research Copyright © 2015 by Teaching & Learning, Ohio State University Libraries is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Importance of Narrowing the Research Topic

Whether you are assigned a general issue to investigate, must choose a problem to study from a list given to you by your professor, or you have to identify your own topic to investigate, it is important that the scope of the research problem is not too broad, otherwise, it will be difficult to adequately address the topic in the space and time allowed. You could experience a number of problems if your topic is too broad, including:

- You find too many information sources and, as a consequence, it is difficult to decide what to include or exclude or what are the most relevant sources.

- You find information that is too general and, as a consequence, it is difficult to develop a clear framework for examining the research problem.

- A lack of sufficient parameters that clearly define the research problem makes it difficult to identify and apply the proper methods needed to analyze it.

- You find information that covers a wide variety of concepts or ideas that can't be integrated into one paper and, as a consequence, you trail off into unnecessary tangents.

Lloyd-Walker, Beverly and Derek Walker. "Moving from Hunches to a Research Topic: Salient Literature and Research Methods." In Designs, Methods and Practices for Research of Project Management . Beverly Pasian, editor. ( Burlington, VT: Gower Publishing, 2015 ), pp. 119-129.

Strategies for Narrowing the Research Topic

A common challenge when beginning to write a research paper is determining how and in what ways to narrow down your topic . Even if your professor gives you a specific topic to study, it will almost never be so specific that you won’t have to narrow it down at least to some degree [besides, it is very boring to grade fifty papers that are all about the exact same thing!].

A topic is too broad to be manageable when a review of the literature reveals too many different, and oftentimes conflicting or only remotely related, ideas about how to investigate the research problem. Although you will want to start the writing process by considering a variety of different approaches to studying the research problem, you will need to narrow the focus of your investigation at some point early in the writing process. This way, you don't attempt to do too much in one paper.

Here are some strategies to help narrow the thematic focus of your paper :

- Aspect -- choose one lens through which to view the research problem, or look at just one facet of it [e.g., rather than studying the role of food in South Asian religious rituals, study the role of food in Hindu marriage ceremonies, or, the role of one particular type of food among several religions].

- Components -- determine if your initial variable or unit of analysis can be broken into smaller parts, which can then be analyzed more precisely [e.g., a study of tobacco use among adolescents can focus on just chewing tobacco rather than all forms of usage or, rather than adolescents in general, focus on female adolescents in a certain age range who choose to use tobacco].

- Methodology -- the way in which you gather information can reduce the domain of interpretive analysis needed to address the research problem [e.g., a single case study can be designed to generate data that does not require as extensive an explanation as using multiple cases].

- Place -- generally, the smaller the geographic unit of analysis, the more narrow the focus [e.g., rather than study trade relations issues in West Africa, study trade relations between Niger and Cameroon as a case study that helps to explain economic problems in the region].

- Relationship -- ask yourself how do two or more different perspectives or variables relate to one another. Designing a study around the relationships between specific variables can help constrict the scope of analysis [e.g., cause/effect, compare/contrast, contemporary/historical, group/individual, child/adult, opinion/reason, problem/solution].

- Time -- the shorter the time period of the study, the more narrow the focus [e.g., restricting the study of trade relations between Niger and Cameroon to only the period of 2010 - 2020].

- Type -- focus your topic in terms of a specific type or class of people, places, or phenomena [e.g., a study of developing safer traffic patterns near schools can focus on SUVs, or just student drivers, or just the timing of traffic signals in the area].

- Combination -- use two or more of the above strategies to focus your topic more narrowly.

NOTE: Apply one of the above strategies first in designing your study to determine if that gives you a manageable research problem to investigate. You will know if the problem is manageable by reviewing the literature on your more narrowed problem and assessing whether prior research is sufficient to move forward in your study [i.e., not too much, not too little]. Be careful, however, because combining multiple strategies risks creating the opposite problem--your problem becomes too narrowly defined and you can't locate enough research or data to support your study.

Booth, Wayne C. The Craft of Research . Fourth edition. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2016; Coming Up With Your Topic. Institute for Writing Rhetoric. Dartmouth College; Narrowing a Topic. Writing Center. University of Kansas; Narrowing Topics. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Strategies for Narrowing a Topic. University Libraries. Information Skills Modules. Virginia Tech University; The Process of Writing a Research Paper. Department of History. Trent University; Ways to Narrow Down a Topic. Contributing Authors. Utah State OpenCourseWare.

- << Previous: Reading Research Effectively

- Next: Broadening a Topic Idea >>

- Last Updated: Jun 12, 2024 8:53 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Unit 5: Conducting Independent Research

34 Choosing and Narrowing a Topic

Preview Questions:

- What should you keep in mind when choosing a topic?

- How can you determine if a topic is suitable for you?

- What are some problems you might encounter with topics? How can you know if a topic is feasible for research or not?

- How can you narrow a topic?

Choosing a Topic

When selecting a topic, ask yourself:

- What am I interested in?

- What have I read recently or heard in the news that’s interesting to me?

- Is there anything in any of my classes that I can connect to the essay topic?

- Is there anything that is affecting me personally right now that might connect to the essay topic?

Exploring potential topics

Two places to start exploring topics are these databases, accessible through the UW-Madison Libraries homepage . Select “databases” from the drop-down menu:

- Opposing Viewpoints

- CQ Researcher

An additional source to further explore the various sides to your topic is Procon.org

Narrowing a Topic

Narrow your topic so that it can be discussed within the page limit of an assignment. Below are some examples of how topics can be narrowed.

| Children | Children’s rights | Child labor in developing countries, like X country | Is it a good idea to make child labor in the clothing industry in X country illegal? |

| Organic food | Labelling of organic foods | labelling of organic foods in the United states | What are the most important criteria the US Department of Agriculture should consider when labelling foods as organic? |

| Refugee crisis | Immigrants coming to the United States | Immigration policies for people from X country seeking asylum in the United States | How will raising the quota for accepting people from X country to come to the United States impact the US economy? |

| Animal rights | Genetic engineering of extinct animals | Using genetic engineering to bring back extinct animals for research | Should scientists be allowed to use genetic engineering to create extinct animals for research purposes? |

| Recycling | Single-use plastics recycling | X country’s efforts to ban single-use plastics to reduce pollution | Is X country’s ban on single-use plastic products effective in reducing pollution? |

Watch the video on Developing a Research Question

From: Steely Library NIKU

Academic Writing I Copyright © by UW-Madison ESL Program is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

5.5: Text- Ways to Narrow Down a Topic

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 59093

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

When to Narrow a Topic

Most students will have to narrow down their topic at least a little. The first clue is that your paper needs to be narrowed is simply the length your professor wants it to be. You can’t properly discuss “war” in 1,000 words, nor talk about orange rinds for 12 pages.

Steps to Narrowing a Topic

- Who? (American Space Exploration)

- What? (Manned Space Missions)

- Where? (Moon Exploration)

- When? (Space exploration in the 1960’s)

- Why? (Quest to leave Earth)

- How? (Rocket to the Moon: Space Exploration)

- Problems faced? (Sustaining Life in Space: Problems with space exploration)

- Problems overcome? (Effects of zero gravity on astronauts)

- Motives? (Beating the Russians: Planning a moon mission)

- Effects on a group? (Renewing faith in science: aftershock of the Moon mission)

- Member group? (Designing a moon lander: NASA engineers behind Apollo 11)

- Group affected? (From Test Pilots to Astronauts: the new heroes of the Air force)

- Group benefited? (Corporations that made money from the American Space Program)

- Group responsible for/paid for _____ (The billion dollar bill: taxpayer reaction to the cost of sending men to the moon)

- S = Similarities (Similar issues to overcome between the 1969 moon mission and the planned 2009 Mars Mission)

- O = Opposites (American pro and con opinions about the first mission to the moon)

- C = Contrasts (Protest or patriotism: different opinions about cost vs. benefit of the moon mission)

- R = Relationships (the NASA family: from the scientists on earth to the astronauts in the sky)

- A = Anthropomorphisms [interpreting reality in terms of human values] (Space: the final frontier)

- P = Personifications [giving objects or descriptions human qualities] (the eagle has landed: animal symbols and metaphors in the space program)

- R = Repetition (More missions to the moon: Pro and Con American attitudes to landing more astronauts on the moon)

- Revision and Adaptation. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Ways to Narrow Down a Topic. Provided by : Utah State University. Located at : http://ocw.usu.edu/English/intermediate-writing/english-2010/-2010/narrowing-topics.html . License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

18.1: Selecting and Narrowing a Topic

Learning objectives.

- Determine the general purpose of a speech.

- List strategies for narrowing a speech topic.

- Compose an audience-centered, specific purpose statement for a speech.

- Compose a thesis statement that summarizes the central idea of a speech.

Many people do not approach speech preparation in an informed and systematic way, which results in poorly planned or executed speeches that are not pleasant to sit through as an audience member and don’t reflect well on the speaker. Good speaking skills can help you stand out from the crowd in increasingly competitive environments. While a polished delivery is important and will be discussed later in this chapter, good speaking skills must be practiced much earlier in the speech-making process.

Analyze Your Audience

Audience analysis is key for a speaker to achieve his or her speech goal. While there are some generalizations you can make about an audience, a competent speaker always assumes there is a diversity of opinion and background among his or her listeners. You can’t assume from looking that everyone in your audience is the same age, race, sexual orientation, religion, or many other factors. Even if you did have a fairly homogenous audience, with only one or two people who don’t match up, you should still consider those one or two people. When I have a class with one or two second-career students, I still consider the different age demographics even though thirty or more other students are eighteen to twenty-two years old. In short, a good speaker shouldn’t intentionally alienate even one audience member. Of course, a speaker could unintentionally alienate certain audience members, especially in persuasive speaking situations. While this may be unavoidable, speakers can still think critically about what content they include in the speech and the effects it may have.

Even though you should remain conscious of the differences among audience members, you can also focus on commonalities. When delivering a speech in a college classroom, you can rightfully assume that everyone in your audience is currently living in the general area of the school, is enrolled at the school, and is currently taking the same Advanced Professional Communication class. In professional speeches, you can often assume that everyone is part of the same professional organization if you present at a conference, employed at the same place or in the same field if you are giving a sales presentation, or experiencing the nervousness of starting a new job if you are leading an orientation or training. You may not be able to assume much more, but that’s enough to add some tailored points to your speech that will make the content more relevant.

Demographic Audience Analysis

Demographics are broad sociocultural categories, such as age, gender, race, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, education level, religion, ethnicity, and nationality that are used to segment a larger population. Since you are always going to have diverse demographics among your audience members, it would be unwise to focus solely on one group over another. As a speaker, being aware of diverse demographics is useful in that you can tailor and vary examples to appeal to different groups. As discussed in the “Getting Real” feature in this chapter, engaging in audience segmentation based on demographics is much more targeted in some careers.

Psychological Audience Analysis

Psychological audience analysis considers your audience’s psychological dispositions toward the topic, speaker, and occasion and the ways in which their attitudes, beliefs, and values inform those dispositions. When considering your audience’s disposition toward your topic, you want to assess your audience’s knowledge of the subject. You wouldn’t include a lesson on calculus in an introductory math course. You also wouldn’t go into the intricacies of a heart transplant to an audience with no medical training. A speech on how to give a speech would be redundant in a public speaking class, but it could be useful for high school students or older adults who are going through a career transition.

The audience may or may not have preconceptions about you as a speaker. One way to positively engage your audience is to make sure you establish your credibility. You want the audience to see you as competent, trustworthy, and engaging. If the audience is already familiar with you, they may already see you as a credible speaker because they’ve seen you speak before, have heard other people evaluate you positively, or know that you have credentials and/or experience that make you competent. If you know you have a reputation that isn’t as positive, work hard to overcome those perceptions. To establish your trustworthiness, incorporate good supporting material into your speech, verbally cite sources, and present information and arguments in a balanced, noncoercive, and nonmanipulative way. To establish yourself as engaging, have a well-delivered speech, which requires you to practice, get feedback, and practice some more. Your verbal and nonverbal delivery should be fluent and appropriate to the audience and occasion.

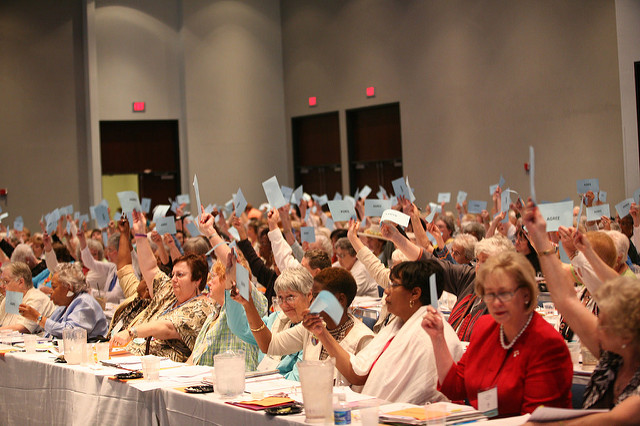

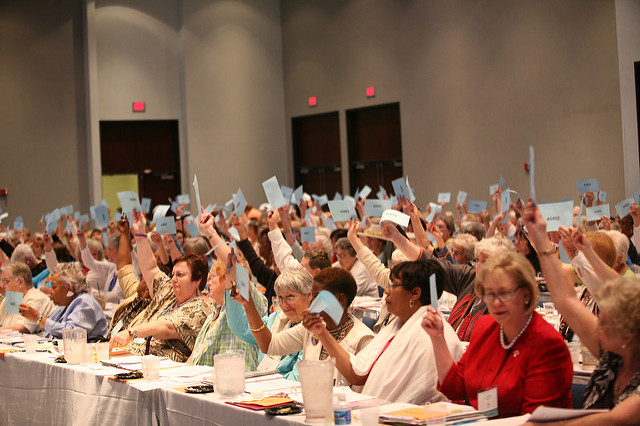

The circumstances that led your audience to attend your speech will affect their view of the occasion. A captive audience includes people who are required to attend your presentation. Mandatory meetings are common in workplace settings. Whether you are presenting for a group of your employees, coworkers, classmates, or even residents in your dorm if you are a resident advisor, you shouldn’t let the fact that the meeting is required give you license to give a half-hearted speech. In fact, you should build common ground with your audience to overcome any potential resentment for the required gathering.

In your Advanced Professional Communication class, your classmates are captive audience members. View having a captive classroom audience as a challenge, and use this space as a public speaking testing laboratory. You can try new things and push your boundaries more, because this audience is very forgiving and understanding, since they have to go through the same things you do. In general, you may have to work harder to maintain the attention of a captive audience. Since coworkers may expect to hear the same content they hear every time this particular meeting comes around, and classmates have to sit through dozens and dozens of speeches, use your speech as an opportunity to stand out from the crowd or from what’s been done before.

A voluntary audience includes people who have decided to come to hear your speech. This is perhaps one of the best compliments a speaker can receive, even before they’ve delivered the speech. Speaking for a voluntary audience often makes speakers have more speaking anxiety, because they know the audience may have preconceived notions or expectations that they must live up to. This is something to be aware of if you are used to speaking in front of captive audiences. To help adapt to a voluntary audience, ask yourself what the audience members expect. Why are they here? If they’ve decided to come and see you, they must be interested in your topic or you as a speaker. Perhaps you have a reputation for being humorous, being able to translate complicated information into more digestible parts, or being interactive with the audience and responding to questions. Whatever the reason or reasons, it’s important to make sure you deliver on those aspects. If people are voluntarily giving up their time to hear you, you want to make sure they get what they expected.

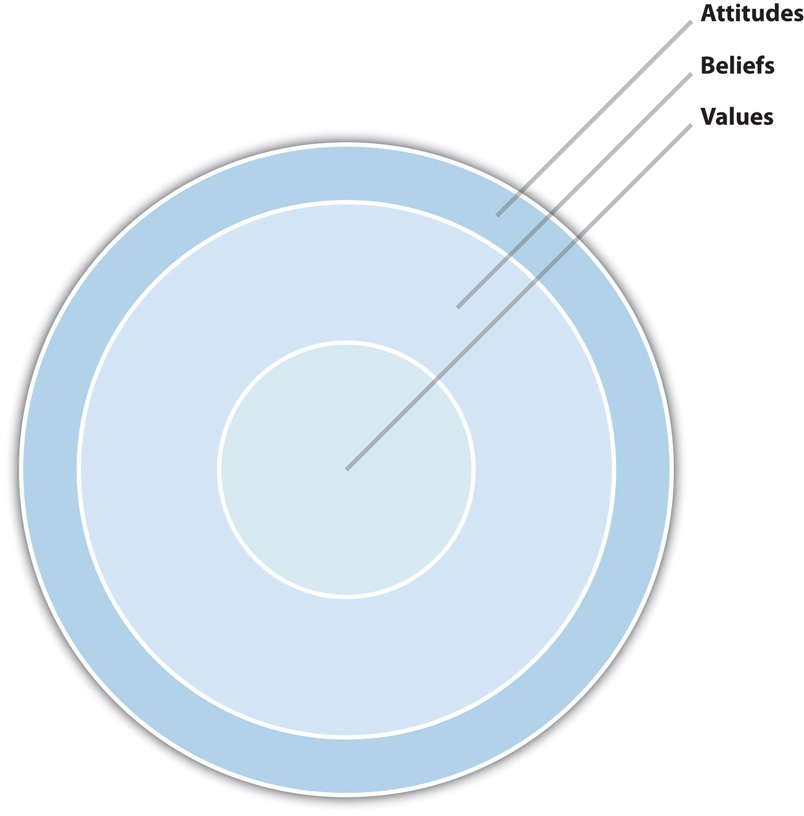

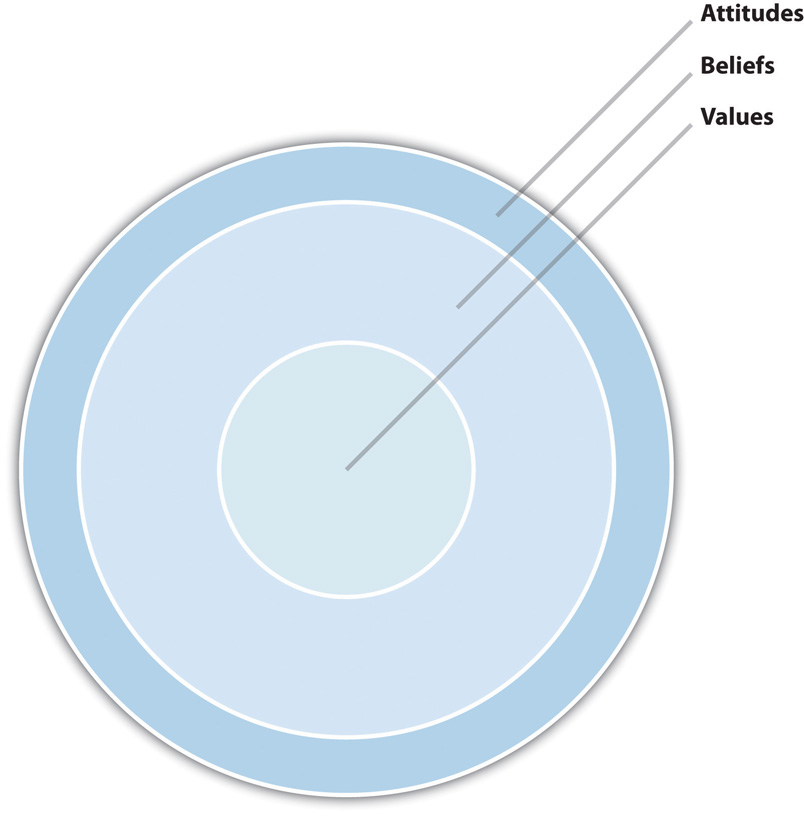

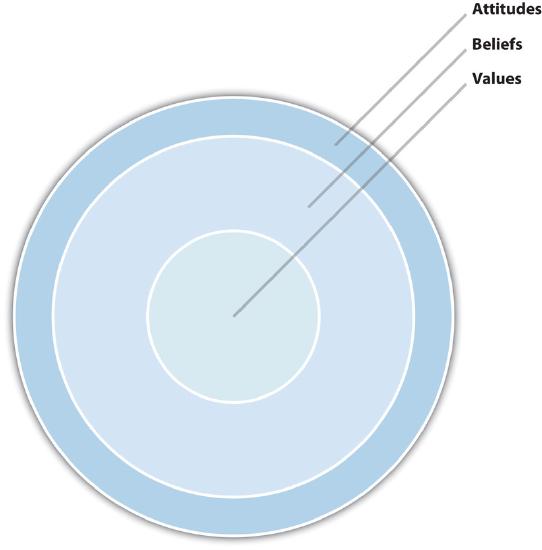

A final aspect of psychological audience analysis involves considering the audience’s attitudes, beliefs, and values, as they will influence all the perceptions mentioned previously. As you can see in Figure 18.1.1 “Psychological Analysis: Attitudes, Beliefs, and Values”, we can think of our attitudes, beliefs, and values as layers that make up our perception and knowledge.

At the outermost level, attitudes are our likes and dislikes, and they are easier to influence than beliefs or values because they are often reactionary. If you’ve ever followed the approval rating of a politician, you know that people’s likes and dislikes change frequently and can change dramatically based on recent developments. This seesaw of attitudes can be useful for a speaker to consider. If there is something going on in popular culture or current events that has captured people’s attention and favor or disfavor, then you can tap into that as a speaker to better relate to your audience. Be careful if the issue is highly controversial, though.

When considering beliefs, we are dealing with what we believe “is or isn’t” or “true or false.” We come to hold our beliefs based on what we are taught, experience for ourselves, or have faith in. Our beliefs change if we encounter new information or experiences that counter previous ones. As people age and experience more, their beliefs are likely to change, which is natural. Being aware of your audience’s beliefs can help you deliver your message in a way that wouldn’t be found offensive and might help learn something, understand something better, or perhaps even question some of their beliefs.

Situational Audience Analysis

Situational audience analysis considers the physical surroundings and setting of a speech. It’s always a good idea to visit the place where you will be speaking ahead of time so you know what to expect. If you expect to have a lectern and arrive to find only a table at the front of the room, that little difference could increase your anxiety and diminish your speaking effectiveness. Take note of the seating arrangement, the presence of technology and its compatibility with what you plan on using, the layout of the room including windows and doors, and anything else that’s relevant to your speech. Knowing your physical setting ahead of time allows you to alter the physical setting, when possible, or alter your message or speaking strategies if needed. For instance, you might open or close blinds, move seats around, plug your computer in to make sure it works, practice some or all of your presentation, revise a speech to be more interactive and informal if it turns out you will speak in a lounge rather than a lecture hall, etc.

Spotlight: “Getting Real”

Marketing Careers and Audience Segmentation

Advertisers and marketers use sophisticated people and programs to ensure that their message is targeted to particular audiences. These people are often called marketing specialists (Career Cruising, 2012). They research products and trends in markets and consumer behaviors and may work for advertising agencies, marketing firms, consulting firms, or other types of agencies or businesses. The pay range is varied, from $35,000 to $166,000 a year for most, and good communication, creativity, and analytic thinking skills are a must. If you stop to think about it, we are all targeted based on our demographics, psychographics, and life situations. Whereas advertisers used to engage in more mass marketing, to undifferentiated receivers, the categories are now much more refined and the target audiences more defined. We only need to look at the recent increase in marketing toward “tweens” or the eight-to-twelve age group. Although this group was once lumped in with younger kids or older teens, they are now targeted because they have “more of their own money to spend and more influence over familial decisions than ever before” (Siegel et al., 2004).

Whether it’s Red Bull aggressively marketing to the college-aged group or gyms marketing to single, working, young adults, much thought and effort goes into crafting a message with a particular receiver in mind. Some companies even create an “ideal customer,” going as far as to name representative audience members, create a psychological and behavioural profile for them, and talk about them as if they were real during message development (Solomon, 2006).

Facebook has revolutionized targeted marketing, which has led to some controversy and backlash (Greenwell, 2012). The “Like” button on Facebook that was introduced in 2010 is now popping up on news sites, company pages, and other websites. When you click the “Like” button, you are providing important information about your consumer behaviours that can then be fed into complicated algorithms that also incorporate demographic and psychographic data pulled from your Facebook profile and even information from your friends. All this is in an effort to more directly market to you, which became easier in January of 2012 when Facebook started allowing targeted advertisements to go directly into users’ “newsfeeds.”

Markets are obviously segmented based on demographics like gender and age, but here are some other categories and examples of market segments: geography (region, city size, climate), lifestyle (couch potato, economical/frugal, outdoorsy, status seeker), family life cycle (bachelors, newlyweds, full nesters, empty nesters), and perceived benefit of use (convenience, durability, value for the money, social acceptance), just to name a few (Schiffman & Kanuk, 2000).

Self-reflection and critical thinking questions:

- Make a list of the various segments you think marketers might put you in. Have you ever thought about these before? Why or why not?

- Take note of the advertisements that catch your eye over a couple days. Do they match up with any of the segments you listed in the first question?

- Are there any groups that you think it would be unethical to segment and target for marketing? Explain your answer.

Determine Your Purpose, Topic, and Thesis

General purpose.

Your speeches will usually fall into one of three categories. In some cases we speak to inform, meaning we attempt to teach our audience using factual, objective evidence. In other cases, we speak to persuade, as we try to influence an audience’s beliefs, attitudes, values, or behaviors. Last, we may speak to entertain or amuse our audience. In summary, the general purpose of your speech will be to inform, to persuade, or to entertain.

You can see various topics that may fit into the three general purposes for speaking in Table 18.1.1 “General Purposes and Speech Topics” . Some of the topics listed could fall into another general purpose category depending on how the speaker approached the topic, or they could contain elements of more than one general purpose. For example, you may have to inform your audience about your topic in one main point before you can persuade them, or you may include some entertaining elements in an informative or persuasive speech to make the content more engaging for the audience. There should not be elements of persuasion included in an informative speech, however, since persuading is contrary to the objective approach that defines an informative general purpose. In any case, while there may be some overlap between general purposes, most speeches can be placed into one of the categories based on the overall content of the speech.

Table 18.1.1 General Purposes and Speech Topics

| To Inform | To Persuade | To Entertain |

|---|---|---|

| Civil rights movement | Gun control | Comedic monologue |

| Renewable energy | Privacy rights | My craziest adventure |

| Reality television | Prison reform | A “roast” |

Choosing a Topic

Once you have determined (or been assigned) your general purpose, you can begin the process of choosing a topic. In most academic, professional, and personal settings, there will be some parameters set that will help guide your topic selection. (In our class, you will be presenting the main findings and recommendations of your Research Report.) Speeches in a class will likely be organized around the content covered in the class. Speeches delivered at work will usually be directed toward a specific goal such as welcoming new employees, informing about changes in workplace policies, or presenting quarterly sales figures. We are also usually compelled to speak about specific things in our personal lives, like addressing a problem at our child’s school by speaking out at a school board meeting. In short, it’s not often that you’ll be starting from scratch when you begin to choose a topic.

Whether you’ve received parameters that narrow your topic range or not, the first step in choosing a topic is brainstorming. Brainstorming involves generating many potential topic ideas in a fast-paced and nonjudgmental manner. Brainstorming can take place multiple times as you narrow your topic. For example, you may begin by brainstorming a list of your personal interests that can then be narrowed down to a speech topic. It makes sense that you will enjoy speaking about something that you care about or find interesting. The research and writing will be more interesting, and the delivery will be easier since you won’t have to fake enthusiasm for your topic. Speaking about something you’re familiar with and interested in can also help you manage speaking anxiety.

Overall you can follow these tips as you select and narrow your topic:

- Brainstorm topics that you are familiar with, interest you, and/or are currently topics of discussion.

- Choose a topic appropriate for the assignment/occasion.

- Choose a topic that you can make relevant to your audience.

- Choose a topic that you have the resources to research (access to information, people to interview, etc.).

Specific Purpose

Once you have brainstormed, narrowed, and chosen your topic, you can begin to draft your specific purpose statement. Your specific purpose is a one-sentence statement that includes the objective you want to accomplish in your speech. You would not necessarily mention your specific purpose aloud during your speech use , but you should use it to guide your researching, organization, and writing. A good specific purpose statement is audience centred, agrees with the general purpose, addresses one main idea, and is realistic.

An audience-centred specific purpose statement usually contains an explicit reference to the audience—for example, “my audience” or “the audience.” Since a speaker may want to see if s/he effectively met a specific purpose, the objective should be written in such a way that it could be measured or assessed, and since a speaker actually wants to achieve his/her speech goal, the specific purpose should also be realistic. You won’t be able to teach the audience a foreign language or persuade an atheist to Christianity in a six- to nine-minute speech. The following is a good example of a good specific purpose statement for an informative speech: “By the end of my speech, the audience will be better informed about the effects the green movement has had on schools in our region.” The statement is audience centered and matches with the general purpose by stating, “the audience will be better informed.” The speaker could also test this specific purpose by asking the audience to write down, at the end of the speech, three effects the green movement has had on schools in your region.

Thesis Statement

Your thesis statement is a one-sentence summary of the central idea of your speech that you either explain or defend. You would explain the thesis statement for an informative speech, since these speeches are based on factual, objective material. In fact, in the case of informative speeches, your “thesis” will be more of a summary statement, since you will be summarizing relevant information rather than generating an argument of your own. You would defend your thesis statement for a persuasive speech, because these speeches are argumentative and your thesis should clearly indicate a stance on a particular issue. In order to make sure your thesis is argumentative and your stance clear, it is helpful to start your thesis with the words “My analysis shows that,” “My recommendation is to…,” etc. When starting to work on a persuasive speech, it can also be beneficial to write out a counterargument to your thesis to ensure that it is arguable.

The thesis statement is different from the specific purpose in two main ways. First, the thesis statement is content centred, while the specific purpose statement is audience centered. Second, the thesis statement is incorporated into the spoken portion of your speech, while the specific purpose serves as a guide for your research and writing and an objective that you can measure, and it isn’t always mentioned aloud. A good thesis statement is declarative, agrees with the general and specific purposes, and focuses and narrows your topic. Although you will likely end up revising and refining your thesis as you research and write, it is good to draft a thesis statement soon after drafting a specific purpose to help guide your progress. As with the specific purpose statement, your thesis helps ensure that your research, organizing, and writing are focused so you don’t end up wasting time with irrelevant materials. Keep your specific purpose and thesis statement handy (drafting them at the top of your working outline is a good idea) so you can reference them often.

For your presentation in COMM 6019, your purpose and thesis would be those established for your Research Report — that is, unless you decide to change your topic to some extent, either because you were not happy with your Report grade or because you have since been able to come up with additional ideas.

The following examples show how a general purpose, specific purpose, and thesis statement match up with a topic area:

Topic: My Craziest Adventure

General purpose: To Entertain

Specific purpose: By the end of my speech, the audience will appreciate the lasting memories that result from an eighteen-year-old visiting New Orleans for the first time.

Thesis statement: New Orleans offers young tourists outstanding opportunities for fun and excitement — especially a, b, and c.

Topic: Renewable Energy

General purpose: To Inform

Specific purpose: By the end of my speech, the audience will be able to explain the basics of using biomass as fuel.

Thesis/ summary statement: Biomass is a renewable resource that releases gases that can be used for fuel.

Topic: Privacy Rights

General purpose: To Persuade

Specific purpose : By the end of my speech, my audience will believe that parents should not be able to use tracking devices to monitor their teenage child’s activities.

Thesis statement: I believe that it is a violation of a child’s privacy to be electronically monitored by the parents.

Key Takeaways

- Demographic, psychographic, and situational audience analysis help tailor your speech content to your audience.

- The general and specific purposes of your speech are based on the speaking occasion and include the objective you would like to accomplish by the end of your speech. Determining these early in the speech-making process will help focus your research and writing.

- Brainstorm to identify topics that fit within your interests, and then narrow your topic based on audience analysis and the guidelines provided.

- A thesis statement summarizes the central idea of your speech and will be explained or defended using supporting material. Referencing your thesis statement often will help ensure that your speech is coherent.

- Conduct some preliminary audience analysis of your class and your classroom. What are some demographics that might be useful for you to consider? What might be some attitudes, beliefs, and values people have that might be relevant to your speech topics? What situational factors might you want to consider before giving your speech?

- Pay attention to the news (in the paper, on the Internet, television, or radio). Identify two informative and two persuasive speech topics that are based in current events.

Career Cruising. (n.d.) Marketing specialist. Career cruising: Explore careers , accessed January 24, 2012, http://www.careercruising.com .

Greenwell, D. (2012, Jan. 13). You might not ‘like’ Facebook so much after reading this…” The Times (London) , sec. T2, 4–5.

Siegel, D. L., Coffey, T. J., and Livingston, G. (2004). The great tween buying machine. Dearborn Trade.

Solomon, M. R. (2006). Consumer behavior: Buying, having, and being (7th ed.), 10-11. Pearson.

Advanced Professional Communication Copyright © 2021 by Melissa Ashman; Arley Cruthers; eCampusOntario; Ontario Business Faculty; and University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Research Tips and Tricks

- Getting Started

- Understanding the Assignment

- Topic Selection Tips

Topic Narrowing

Ways to narrow your topic, be careful, tools to help, youtube videos about narrowing a topic.

- Breaking Topic Into Keywords

- Developing A Search Strategy

- Scholarly vs Popular Sources

- What Are Primary Sources?

- Finding Scholarly Articles

- Finding Scholarly Books

- Finding Primary Sources

- Citing My Sources This link opens in a new window

Instructional Librarian

Talk to your professor

A common challenge when beginning to write a research paper is determining how to narrow down your topic.

Even if your professor gives you a topic to study, it will seldom be specific enough that you will not have to narrow it down, at least to some degree.

A topic is too broad to be manageable when you find that you have too many different, conflicting or only remotely related ideas.

Although you will want to start the writing process by considering a variety of different approaches to studying the research problem, you will need to narrow the focus of your investigation at some point early in the writing process - this way you don't attempt to do too much in one paper.

Here are some strategies to help narrow your topic :

Aspect -- choose one lens through which to view the research problem, or look at just one facet of it.

- e.g., rather than studying the role of food in South Asian religious rituals, explore the role of food in Hindu ceremonies or the role of one particular type of food among several religions.

Components -- determine if your initial variable or unit of analysis can be broken into smaller parts, which can then be analyzed more precisely.

- e.g., a study of tobacco use among adolescents can focus on just chewing tobacco rather than all forms of usage or, rather than adolescents in general, focus on female adolescents in a specific age range who choose to use tobacco.

Methodology -- how you gather information can reduce the domain of interpretive analysis needed to address the research problem.

- e.g., a single case study can be designed to generate data that does not require as extensive an explanation as using multiple cases.

Place -- generally, the smaller the geographic unit of analysis, the more narrow the focus.

- e.g., rather than study trade relations in North America, study trade relations between Mexico and the United States.

Relationship -- ask yourself how do two or more different perspectives or variables relate to one another. Designing a study around the relationships between specific variables can help constrict the scope of analysis.

- e.g., cause/effect, compare/contrast, contemporary/historical, group/individual, male/female, opinion/reason, problem/solution.

Time -- the shorter the time period of the study, the more narrow the focus.

- e.g., study of relations between Russia and the United States during the Vietnam War.

Type -- focus your topic in terms of a specific type or class of people, places, or phenomena.

- e.g., a study of developing safer traffic patterns near schools can focus on SUVs, or just student drivers, or just the timing of traffic signals in the area.

Cause -- focus your topic to just one cause for your topic.

- e.g., rather than writing about all the causes of WW1, just write about nationalism.

When narrowing your topic, make sure you don't narrow it too much. A topic is too narrow if you can state it in just a few words.

For example:

- How many soldiers died during the first world war?

- Who was the first President of the United States?

- Why is ocean water salty?

- Why are Pringles shaped the way they are?

- Developing a Research Topic This exercise is designed to help you develop a thoughtful topic for your research assignment, including methods for narrowing your topic.

- What Makes a Good Research Question?

- Narrowing Your topic

- Four Steps To Narrow Your Research Topic

- << Previous: Topic Selection Tips

- Next: Breaking Topic Into Keywords >>

- Last Updated: Apr 9, 2024 10:45 AM

- URL: https://kingsu.libguides.com/research

Text: Ways to Narrow Down a Topic

When to narrow a topic.

Most students will have to narrow down their topic at least a little. The first clue is that your paper needs to be narrowed is simply the length your professor wants it to be. You can’t properly discuss “war” in 1,000 words, nor talk about orange rinds for 12 pages.

Steps to Narrowing a Topic

- Who? (American Space Exploration)

- What? (Manned Space Missions)

- Where? (Moon Exploration)

- When? (Space exploration in the 1960’s)

- Why? (Quest to leave Earth)

- How? (Rocket to the Moon: Space Exploration)

- Problems faced? (Sustaining Life in Space: Problems with space exploration)

- Problems overcome? (Effects of zero gravity on astronauts)

- Motives? (Beating the Russians: Planning a moon mission)

- Effects on a group? (Renewing faith in science: aftershock of the Moon mission)

- Member group? (Designing a moon lander: NASA engineers behind Apollo 11)

- Group affected? (From Test Pilots to Astronauts: the new heroes of the Air force)

- Group benefited? (Corporations that made money from the American Space Program)

- Group responsible for/paid for _____ (The billion dollar bill: taxpayer reaction to the cost of sending men to the moon)

- S = Similarities (Similar issues to overcome between the 1969 moon mission and the planned 2009 Mars Mission)

- O = Opposites (American pro and con opinions about the first mission to the moon)

- C = Contrasts (Protest or patriotism: different opinions about cost vs. benefit of the moon mission)

- R = Relationships (the NASA family: from the scientists on earth to the astronauts in the sky)

- A = Anthropomorphisms [interpreting reality in terms of human values] (Space: the final frontier)

- P = Personifications [giving objects or descriptions human qualities] (the eagle has landed: animal symbols and metaphors in the space program)

- R = Repetition (More missions to the moon: Pro and Con American attitudes to landing more astronauts on the moon)

- Revision and Adaptation. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Ways to Narrow Down a Topic. Provided by : Utah State University. Retrieved from : http://ocw.usu.edu/English/intermediate-writing/english-2010/-2010/narrowing-topics.html. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1.4 Selecting and Narrowing Down Your Topic

Learning objectives.

- Employ audience analysis.

- Determine the general purpose of a speech.

- List strategies for narrowing a speech topic.

- Compose an audience-centered, specific purpose statement for a speech.

- Compose a thesis statement that summarizes the central idea of a speech.

There are many steps that go into the speech-making process. Many people do not approach speech preparation in an informed and systematic way, which results in many poorly planned or executed speeches that are not pleasant to sit through as an audience member and don’t reflect well on the speaker. Good speaking skills can help you stand out from the crowd in increasingly competitive environments. While a polished delivery is important and will be discussed more in Chapter 10 “Delivering a Speech” , good speaking skills must be practiced much earlier in the speech-making process.

Analyze Your Audience

Audience analysis is key for a speaker to achieve his or her speech goal. One of the first questions you should ask yourself is “Who is my audience?” While there are some generalizations you can make about an audience, a competent speaker always assumes there is a diversity of opinion and background among his or her listeners. You can’t assume from looking that everyone in your audience is the same age, race, sexual orientation, religion, or many other factors.

Even if you did have a fairly homogenous audience, with only one or two people who don’t match up, you should still consider those one or two people. When I have a class with one or two older students, I still consider the different age demographics even though twenty other students are eighteen to twenty-two years old.