Subscribe or renew today

Every print subscription comes with full digital access

Science News

Social media harms teens’ mental health, mounting evidence shows. what now.

Understanding what is going on in teens’ minds is necessary for targeted policy suggestions

Most teens use social media, often for hours on end. Some social scientists are confident that such use is harming their mental health. Now they want to pinpoint what explains the link.

Carol Yepes/Getty Images

Share this:

By Sujata Gupta

February 20, 2024 at 7:30 am

In January, Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Facebook’s parent company Meta, appeared at a congressional hearing to answer questions about how social media potentially harms children. Zuckerberg opened by saying: “The existing body of scientific work has not shown a causal link between using social media and young people having worse mental health.”

But many social scientists would disagree with that statement. In recent years, studies have started to show a causal link between teen social media use and reduced well-being or mood disorders, chiefly depression and anxiety.

Ironically, one of the most cited studies into this link focused on Facebook.

Researchers delved into whether the platform’s introduction across college campuses in the mid 2000s increased symptoms associated with depression and anxiety. The answer was a clear yes , says MIT economist Alexey Makarin, a coauthor of the study, which appeared in the November 2022 American Economic Review . “There is still a lot to be explored,” Makarin says, but “[to say] there is no causal evidence that social media causes mental health issues, to that I definitely object.”

The concern, and the studies, come from statistics showing that social media use in teens ages 13 to 17 is now almost ubiquitous. Two-thirds of teens report using TikTok, and some 60 percent of teens report using Instagram or Snapchat, a 2022 survey found. (Only 30 percent said they used Facebook.) Another survey showed that girls, on average, allot roughly 3.4 hours per day to TikTok, Instagram and Facebook, compared with roughly 2.1 hours among boys. At the same time, more teens are showing signs of depression than ever, especially girls ( SN: 6/30/23 ).

As more studies show a strong link between these phenomena, some researchers are starting to shift their attention to possible mechanisms. Why does social media use seem to trigger mental health problems? Why are those effects unevenly distributed among different groups, such as girls or young adults? And can the positives of social media be teased out from the negatives to provide more targeted guidance to teens, their caregivers and policymakers?

“You can’t design good public policy if you don’t know why things are happening,” says Scott Cunningham, an economist at Baylor University in Waco, Texas.

Increasing rigor

Concerns over the effects of social media use in children have been circulating for years, resulting in a massive body of scientific literature. But those mostly correlational studies could not show if teen social media use was harming mental health or if teens with mental health problems were using more social media.

Moreover, the findings from such studies were often inconclusive, or the effects on mental health so small as to be inconsequential. In one study that received considerable media attention, psychologists Amy Orben and Andrew Przybylski combined data from three surveys to see if they could find a link between technology use, including social media, and reduced well-being. The duo gauged the well-being of over 355,000 teenagers by focusing on questions around depression, suicidal thinking and self-esteem.

Digital technology use was associated with a slight decrease in adolescent well-being , Orben, now of the University of Cambridge, and Przybylski, of the University of Oxford, reported in 2019 in Nature Human Behaviour . But the duo downplayed that finding, noting that researchers have observed similar drops in adolescent well-being associated with drinking milk, going to the movies or eating potatoes.

Holes have begun to appear in that narrative thanks to newer, more rigorous studies.

In one longitudinal study, researchers — including Orben and Przybylski — used survey data on social media use and well-being from over 17,400 teens and young adults to look at how individuals’ responses to a question gauging life satisfaction changed between 2011 and 2018. And they dug into how the responses varied by gender, age and time spent on social media.

Social media use was associated with a drop in well-being among teens during certain developmental periods, chiefly puberty and young adulthood, the team reported in 2022 in Nature Communications . That translated to lower well-being scores around ages 11 to 13 for girls and ages 14 to 15 for boys. Both groups also reported a drop in well-being around age 19. Moreover, among the older teens, the team found evidence for the Goldilocks Hypothesis: the idea that both too much and too little time spent on social media can harm mental health.

“There’s hardly any effect if you look over everybody. But if you look at specific age groups, at particularly what [Orben] calls ‘windows of sensitivity’ … you see these clear effects,” says L.J. Shrum, a consumer psychologist at HEC Paris who was not involved with this research. His review of studies related to teen social media use and mental health is forthcoming in the Journal of the Association for Consumer Research.

Cause and effect

That longitudinal study hints at causation, researchers say. But one of the clearest ways to pin down cause and effect is through natural or quasi-experiments. For these in-the-wild experiments, researchers must identify situations where the rollout of a societal “treatment” is staggered across space and time. They can then compare outcomes among members of the group who received the treatment to those still in the queue — the control group.

That was the approach Makarin and his team used in their study of Facebook. The researchers homed in on the staggered rollout of Facebook across 775 college campuses from 2004 to 2006. They combined that rollout data with student responses to the National College Health Assessment, a widely used survey of college students’ mental and physical health.

The team then sought to understand if those survey questions captured diagnosable mental health problems. Specifically, they had roughly 500 undergraduate students respond to questions both in the National College Health Assessment and in validated screening tools for depression and anxiety. They found that mental health scores on the assessment predicted scores on the screenings. That suggested that a drop in well-being on the college survey was a good proxy for a corresponding increase in diagnosable mental health disorders.

Compared with campuses that had not yet gained access to Facebook, college campuses with Facebook experienced a 2 percentage point increase in the number of students who met the diagnostic criteria for anxiety or depression, the team found.

When it comes to showing a causal link between social media use in teens and worse mental health, “that study really is the crown jewel right now,” says Cunningham, who was not involved in that research.

A need for nuance

The social media landscape today is vastly different than the landscape of 20 years ago. Facebook is now optimized for maximum addiction, Shrum says, and other newer platforms, such as Snapchat, Instagram and TikTok, have since copied and built on those features. Paired with the ubiquity of social media in general, the negative effects on mental health may well be larger now.

Moreover, social media research tends to focus on young adults — an easier cohort to study than minors. That needs to change, Cunningham says. “Most of us are worried about our high school kids and younger.”

And so, researchers must pivot accordingly. Crucially, simple comparisons of social media users and nonusers no longer make sense. As Orben and Przybylski’s 2022 work suggested, a teen not on social media might well feel worse than one who briefly logs on.

Researchers must also dig into why, and under what circumstances, social media use can harm mental health, Cunningham says. Explanations for this link abound. For instance, social media is thought to crowd out other activities or increase people’s likelihood of comparing themselves unfavorably with others. But big data studies, with their reliance on existing surveys and statistical analyses, cannot address those deeper questions. “These kinds of papers, there’s nothing you can really ask … to find these plausible mechanisms,” Cunningham says.

One ongoing effort to understand social media use from this more nuanced vantage point is the SMART Schools project out of the University of Birmingham in England. Pedagogical expert Victoria Goodyear and her team are comparing mental and physical health outcomes among children who attend schools that have restricted cell phone use to those attending schools without such a policy. The researchers described the protocol of that study of 30 schools and over 1,000 students in the July BMJ Open.

Goodyear and colleagues are also combining that natural experiment with qualitative research. They met with 36 five-person focus groups each consisting of all students, all parents or all educators at six of those schools. The team hopes to learn how students use their phones during the day, how usage practices make students feel, and what the various parties think of restrictions on cell phone use during the school day.

Talking to teens and those in their orbit is the best way to get at the mechanisms by which social media influences well-being — for better or worse, Goodyear says. Moving beyond big data to this more personal approach, however, takes considerable time and effort. “Social media has increased in pace and momentum very, very quickly,” she says. “And research takes a long time to catch up with that process.”

Until that catch-up occurs, though, researchers cannot dole out much advice. “What guidance could we provide to young people, parents and schools to help maintain the positives of social media use?” Goodyear asks. “There’s not concrete evidence yet.”

More Stories from Science News on Science & Society

Aimee Grant investigates the needs of autistic people

In ‘Get the Picture,’ science helps explore the meaning of art

What Science News saw during the solar eclipse

During the awe of totality, scientists studied our planet’s reactions

Your last-minute guide to the 2024 total solar eclipse

Protein whisperer Oluwatoyin Asojo fights neglected diseases

How a 19th century astronomer can help you watch the total solar eclipse

Timbre can affect what harmony is music to our ears

Subscribers, enter your e-mail address for full access to the Science News archives and digital editions.

Not a subscriber? Become one now .

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Supreme Court tackles social media and free speech

Nina Totenberg

In a major First Amendment case, the Supreme Court heard arguments on the federal government's ability to combat what it sees as false, misleading or dangerous information online.

ARI SHAPIRO, HOST:

At the Supreme Court today, a majority of the justices seemed highly skeptical of claims that federal officials may be broadly barred from contacts with social media platforms. At issue was a sweeping 5th Circuit Court of Appeals decision. That ruling blocked officials from the White House, the FBI, the CDC and other agencies from asking social media companies to remove certain content. NPR legal affairs correspondent Nina Totenberg reports.

NINA TOTENBERG, BYLINE: Five individuals and two Republican-dominated states claim that the government is violating the First Amendment by systematically pressuring social media companies to take down what the government sees as false and misleading information. The Biden administration counters that White House and agency officials are well within their rights to persuade social media companies about what they see as erroneous information about COVID-19 or foreign interference in an election or even election information about where to vote. Two justices who once worked in the White House - Brett Kavanaugh, a Trump appointee, and Elena Kagan, an Obama appointee - were the most outspoken about the long history of government contacts with media companies. Here's Kavanaugh.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

BRETT KAVANAUGH: I've experienced government press people throughout the federal government who regularly call up the media and berate them.

TOTENBERG: Justice Kagan echoed that sentiment.

ELENA KAGAN: Like Justice Kavanaugh, I've had some experience encouraging press...

KAGAN: ...To suppress their own speech. You just wrote a story that's filled with factual errors. Here are the 10 reasons why you shouldn't do that again. I mean, this happens literally thousands of times a day in the federal government.

TOTENBERG: She and Justice Barrett postulated that the FBI might contact social media companies to tell them that while they might not realize it, they've been posting information from a terrorist group aimed at secret recruitment. Louisiana's solicitor general, Benjamin Aguinaga, argued that when government officials contact social media companies, even encouraging, amounts to unconstitutional pressuring. That prompted this from Justice Barrett.

BENJAMIN AGUINAGA: I mean...

AMY CONEY BARRETT: Just plain, vanilla encouragement, or does it have to be some kind of, like, significant encouragement? - because encouragement would sweep in an awful lot.

TOTENBERG: Aguinaga, however, didn't have a clear line of differentiation, except to claim that pressuring print and other media outlets is different from pressuring social media platforms. What about publishing classified information, asked Justice Kavanaugh. Are you suggesting the government can't try to get that taken down? Or what about factual inaccuracies? Justice Jackson asked about matters of public safety. What if young people were being injured or killed, carrying out a new online fad that called for jumping out of windows? Couldn't the government legitimately ask platforms to take that down? When the Louisiana solicitor general fudged, Chief Justice Roberts followed up.

JOHN ROBERTS: Under my colleague's hypothetical, it was not necessarily eliminate viewpoints. It was to eliminate some game that is seriously harming children around the country. And they say, we encourage you to stop that.

AGUINAGA: Your honor, I agree. As a policy matter, it might be great for the government to be able to do that. But the moment that the government identifies an entire category of content that it wishes to not be in the modern public sphere, that is a First Amendment problem.

TOTENBERG: Several justices questioned the record in the case. Justice Kagan said she did not see even one item that supported barring government contacts. Justice Sotomayor put it this way.

SONIA SOTOMAYOR: I have such a problem with your brief, Counselor. You omit information that changes the context of some of your claims. You attribute things to people who it didn't happen to. I'm not sure how we get to prove direct injury in any way.

TOTENBERG: Representing the Biden administration today, Deputy Solicitor General Brian Fletcher took incoming fire, mainly from Justices Alito and Thomas. But he stuck to his contention that when the government seeks to persuade a social media platform to take down a post, that is an attempt at persuasion not coercion. Unlike some of his conservative colleagues, Justice Alito was skeptical of all aspects of the government's argument.

SAMUEL ALITO: There is constant pestering of Facebook and some of the other platforms, and they want to have regular meetings. They suggest rules that should be applied. And I thought, wow, I cannot imagine federal officials taking that approach to the print media.

TOTENBERG: Nina Totenberg, NPR News, Washington.

Copyright © 2024 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- The State of Online Harassment

Roughly four-in-ten Americans have experienced online harassment, with half of this group citing politics as the reason they think they were targeted. Growing shares face more severe online abuse such as sexual harassment or stalking

Table of contents.

- 1. Personal experiences with online harassment

- 2. Characterizing people’s most recent online harassment experience

- 3. Americans’ views on how online harassment should be addressed

- Acknowledgments

- Methodology

Pew Research Center has a history of studying online harassment. This report focuses on American adults’ experiences and attitudes related to online harassment. For this analysis, we surveyed 10,093 U.S. adults from Sept. 8 to 13, 2020. Everyone who took part is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology . Here are the questions used for this report , along with responses, and its methodology .

Stories about online harassment have captured headlines for years. Beyond the more severe cases of sustained , aggressive abuse that make the news, name-calling and belittling, derisive comments have come to characterize how many view discourse online – especially in the political realm.

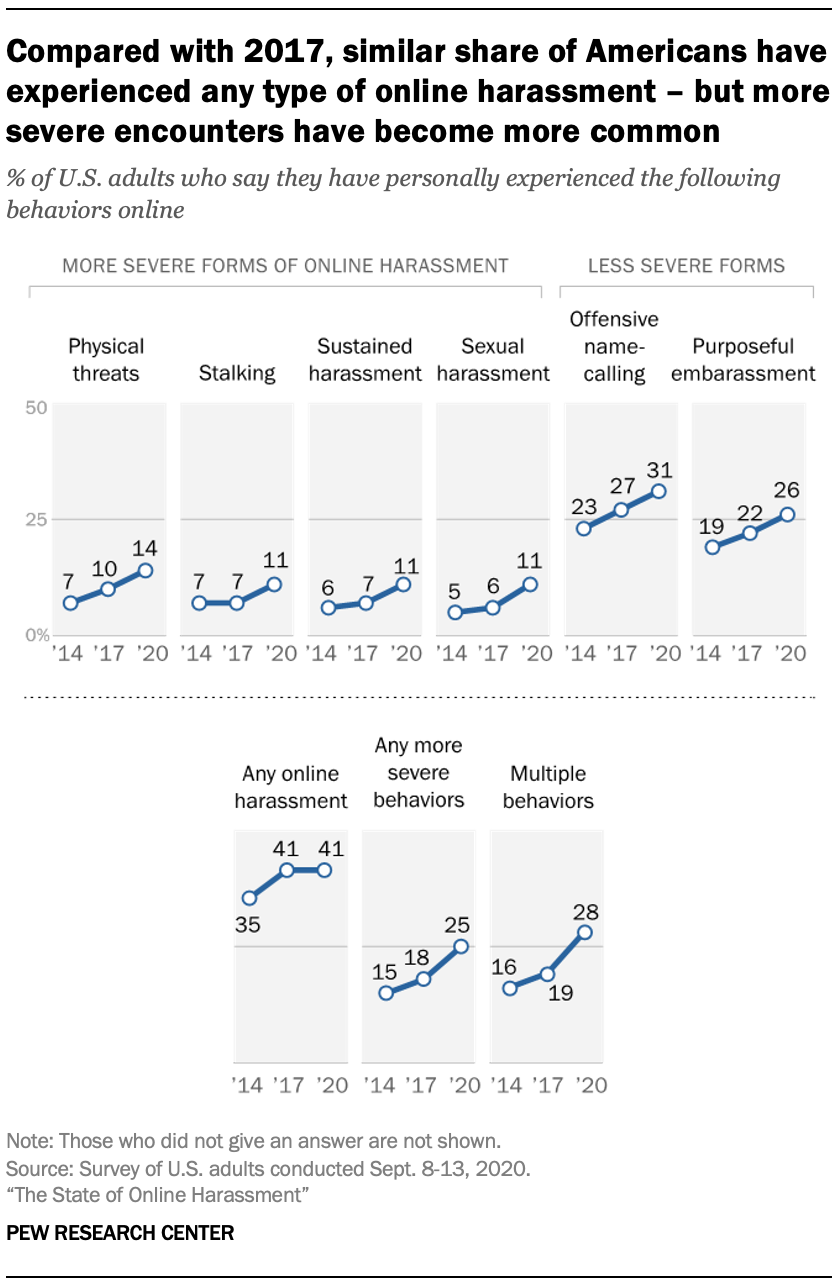

A Pew Research Center survey of U.S. adults in September finds that 41% of Americans have personally experienced some form of online harassment in at least one of the six key ways that were measured. And while the overall prevalence of this type of abuse is the same as it was in 2017, there is evidence that online harassment has intensified since then.

To begin with, growing shares of Americans report experiencing more severe forms of harassment, which encompasses physical threats, stalking, sexual harassment and sustained harassment. Some 15% experienced such problems in 2014 and a slightly larger share (18%) said the same in 2017. 1 That group has risen to 25% today. Additionally, those who have been the target of online abuse are more likely today than in 2017 to report that their most recent experience involved more varied types and more severe forms of online abuse.

In a political environment where Americans are stressed and frustrated and antipathy has grown , online venues often serve as platforms for highly contentious or even extremely offensive political debate. And for those who have experienced online abuse, politics is cited as the top reason for why they think they were targeted.

Defining online harassment

This report measures online harassment using six distinct behaviors:

- Offensive name-calling

- Purposeful embarrassment

- Physical threats

- Harassment over a sustained period of time

- Sexual harassment

Respondents who indicate they have personally experienced any of these behaviors online are considered targets of online harassment in this report. Further, this report distinguishes between “more severe” and “less severe” forms of online harassment. Those who have only experienced name-calling or efforts to embarrass them are categorized in the “less severe” group, while those who have experienced any stalking, physical threats, sustained harassment or sexual harassment are categorized in the “more severe” group.

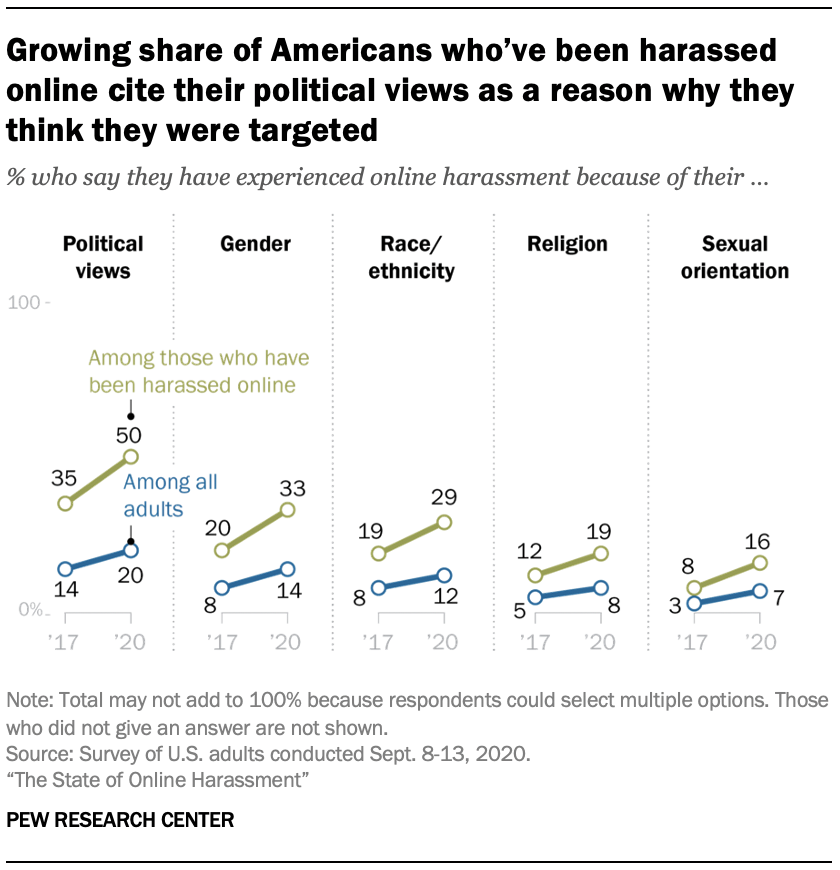

Indeed, 20% of Americans overall – representing half of those who have been harassed online – say they have experienced online harassment because of their political views. This is a notable increase from three years ago, when 14% of all Americans said they had been targeted for this reason. Beyond politics, more also cite their gender or their racial and ethnic background as reasons why they believe they were harassed online.

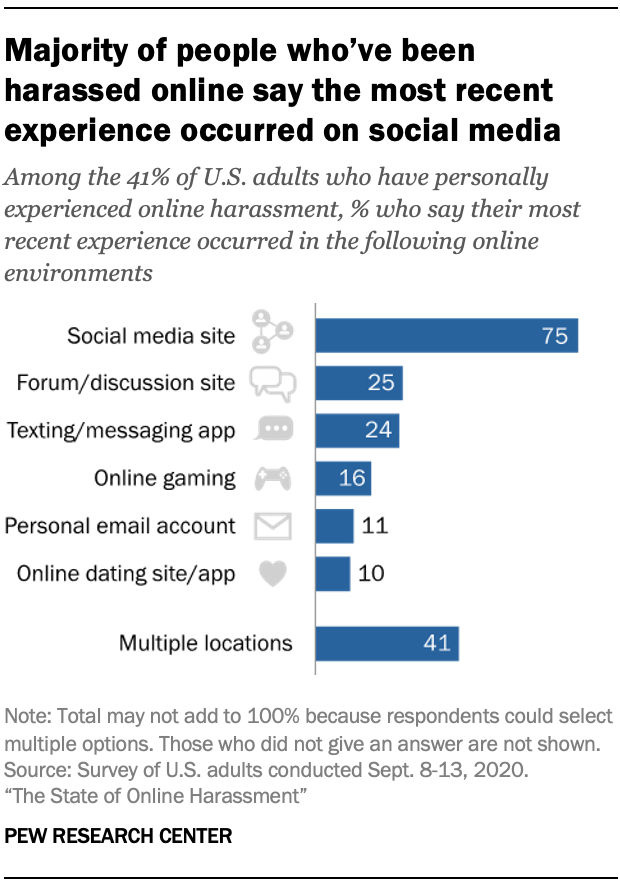

While these kinds of negative encounters may occur anywhere online, social media is by far the most common venue cited for harassment – a pattern consistent across the Center’s work over the years on this topic. The latest survey finds that 75% of targets of online abuse – equaling 31% of Americans overall – say their most recent experience was on social media.

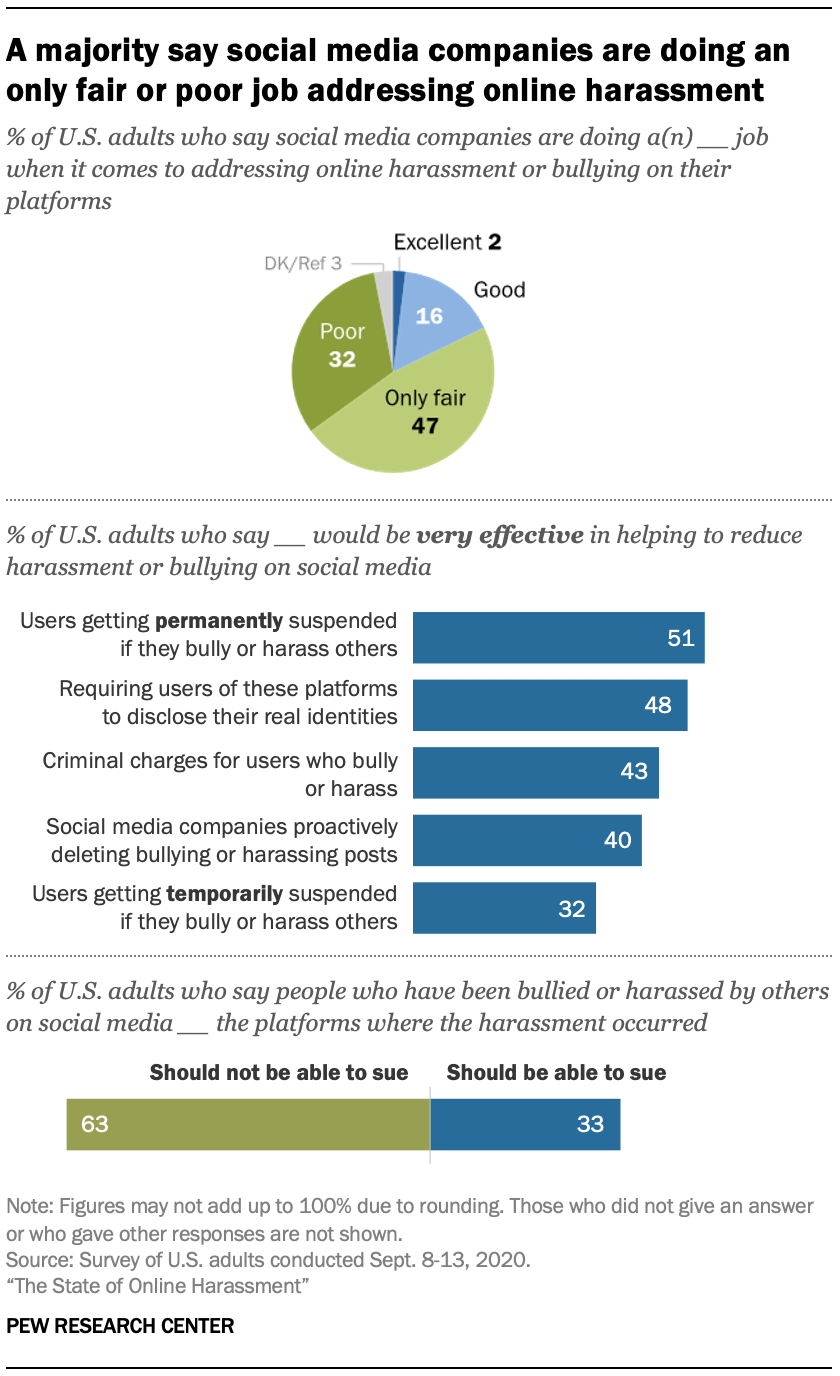

As online harassment permeates social media, the public is highly critical of the way these companies are tackling the issue. Fully 79% say social media companies are doing an only fair or poor job at addressing online harassment or bullying on their platforms.

But even as social media companies receive low ratings for handling abuse on their sites, a minority of Americans back the idea of holding these platforms legally responsible for harassment that happens on their sites. Just 33% of Americans say that people who have experienced harassment or bullying on social media sites should be able to sue the platforms on which it occurred.

These are some of the key findings from a nationally representative survey of 10,093 U.S. adults conducted online Sept. 8 to 13, 2020, using Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel . The following are among the major findings.

41% of U.S. adults have personally experienced online harassment, and 25% have experienced more severe harassment

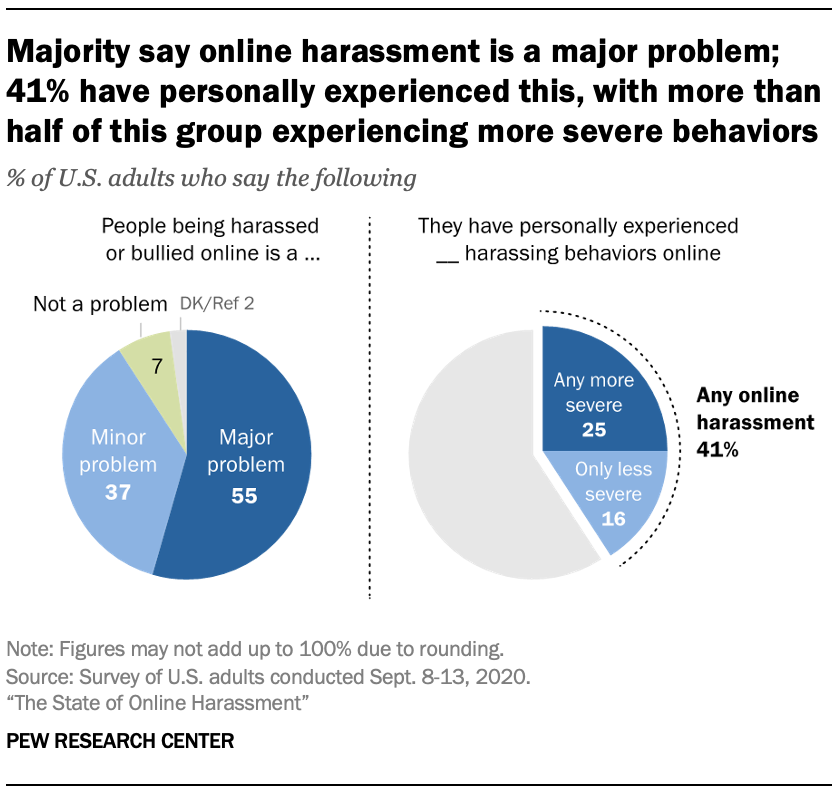

On a broad level, Americans agree that online harassment is a problem plaguing digital spaces. Roughly nine-in-ten Americans say people being harassed or bullied online is a problem, including 55% who consider it a major problem.

Many Americans have also had their own experience with being targeted online. While about four-in-ten Americans (41%) have experienced some form of online harassment, growing shares have faced more severe and multiple forms of harassment. For example, in 2014, 15% of Americans said they had been subjected to more severe forms of online harassment. That share is now 25%. There has also been a double-digit increase in those experiencing multiple types of online abuse – rising from 16% to 28% since 2014. This number is also up since 2017, when 19% of Americans had experienced multiple forms of harassing behaviors online.

Many individual types of behaviors are on the rise as well. The shares of Americans who say they have been called an offensive name, purposefully embarrassed or physically threatened while online have all risen since 2014. However, the share who have experienced any of the less severe behaviors is largely on par with that of 2017 (37% in 2020 vs. 36% in 2017).

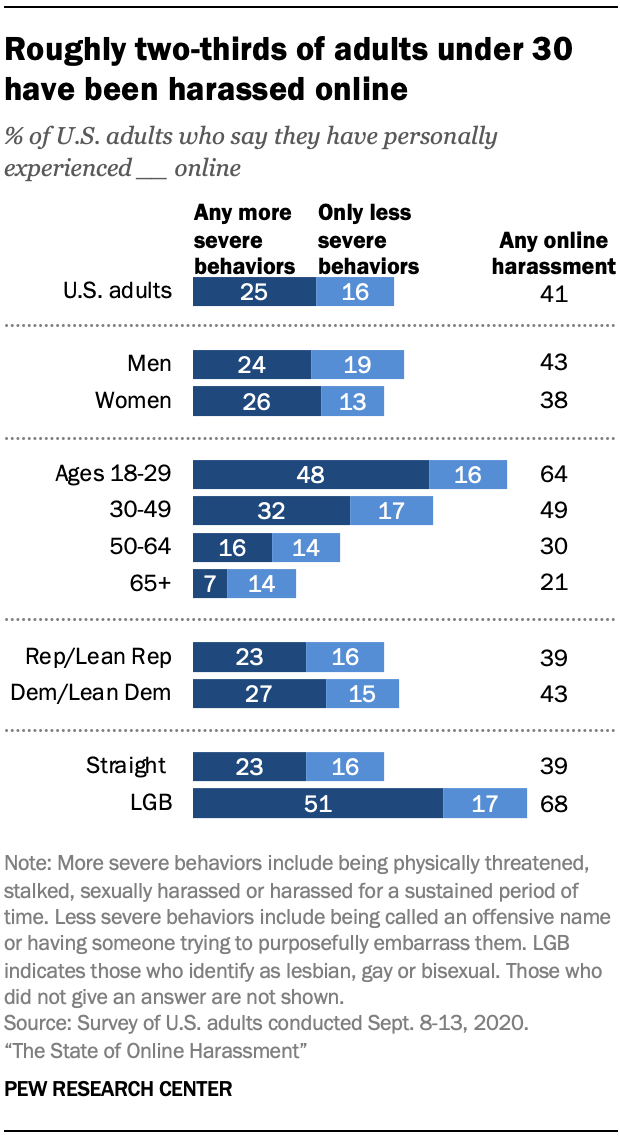

A majority of younger adults have encountered harassment online

Online harassment is a particularly common feature of online life for younger adults, and they are especially prone to facing harassing behaviors that are more serious. Roughly two-thirds of adults under 30 (64%) have experienced any form of the online harassment activities measured in this survey – making this the only age group in which a majority have been subjected to these behaviors. Still, about half of 30- to 49-year-olds have been the target of online harassment, while smaller shares of those ages 50 and older (26%) have encountered at least one of these harassing activities.

A similar pattern is present when looking at those who have faced more severe forms of online abuse: 48% of 18- to 29-year-olds have been targeted online with more severe behaviors, compared with 32% of those ages 30 to 49 and just 12% of those 50 and older.

Gender also plays a role in the types of harassment people are likely to encounter online. Overall, men are somewhat more likely than women to say they have experienced any form of harassment online (43% vs. 38%), but similar shares of men and women have faced more severe forms of this kind of abuse. There are also differences across individual types of online harassment in the types of negative incidents they have personally encountered online. Some 35% of men say they have been called an offensive name versus 26% of women, and being physically threatened online is more common occurrence for men rather than women (16% vs. 11%).

Women, on the other hand, are more likely than men to report having been sexually harassed online (16% vs. 5%) or stalked (13% vs. 9%). Young women are particularly likely to have experienced sexual harassment online. Fully 33% of women under 35 say they have been sexually harassed online, while 11% of men under 35 say the same.

Lesbian, gay or bisexual adults are particularly likely to face harassment online. Roughly seven-in-ten have encountered any harassment online and fully 51% have been targeted for more severe forms of online abuse. By comparison, about four-in-ten straight adults have endured any form of harassment online, and only 23% have undergone any of the more severe behaviors.

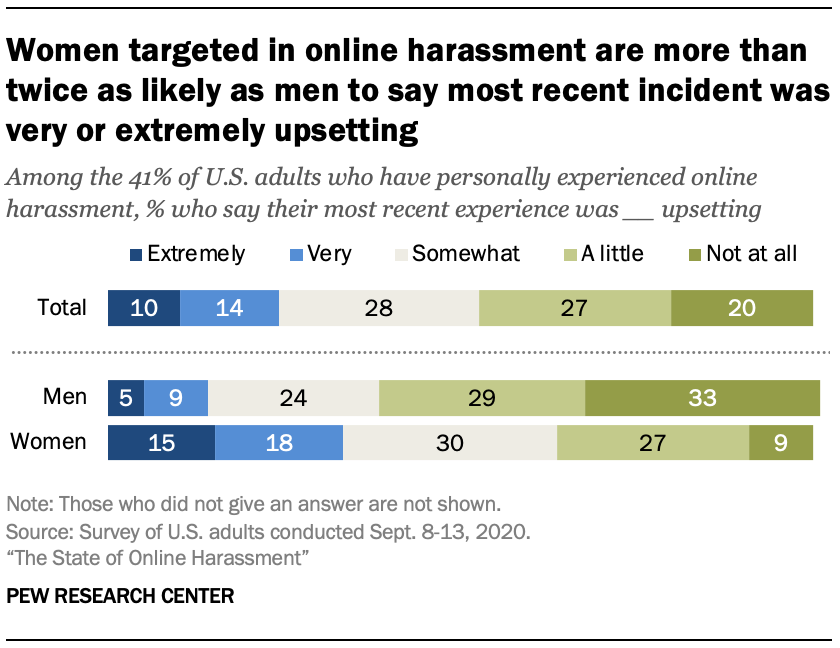

While men are somewhat more likely than women to experience harassment online, women are more likely to be upset about it and think it is a major problem. Some 61% of women say online harassment is a major problem, while 48% of men agree. In addition, women who have been harassed online are more than twice as likely as men to say they were extremely or very upset by their most recent encounter (34% vs. 14%). Conversely, 61% of men who have been harassed online say they were not at all or a little upset by their most recent incident, while 36% of women said the same. Overall, 24% of those who have experienced online harassment say that their most recent incident was extremely (10%) or very (14%) upsetting.

One-in-five adults report being harassed online for their political views

Those who have been harassed were then asked whether they believed certain personal characteristics – political views, gender, race or ethnicity, religion or sexual orientation – played a role in the attacks. Fully 20% of all adults – or 50% of online harassment targets – say they have been harassed online because of their political views. At the same time, 14% of U.S. adults (33% of people who have been harassed online) say they have been harassed based on their gender, while 12% say this occurred because of their race or ethnicity (29% of online harassment targets). Smaller shares point to their religion or their sexual orientation as a reason for their harassment.

Each of these reasons has risen since the Center last asked these questions in 2017. There have been 6 percentage point increases in the shares of Americans attributing their harassment to their political views as well as gender. Race or ethnicity, sexual orientation and religion each saw a modest rise since 2017.

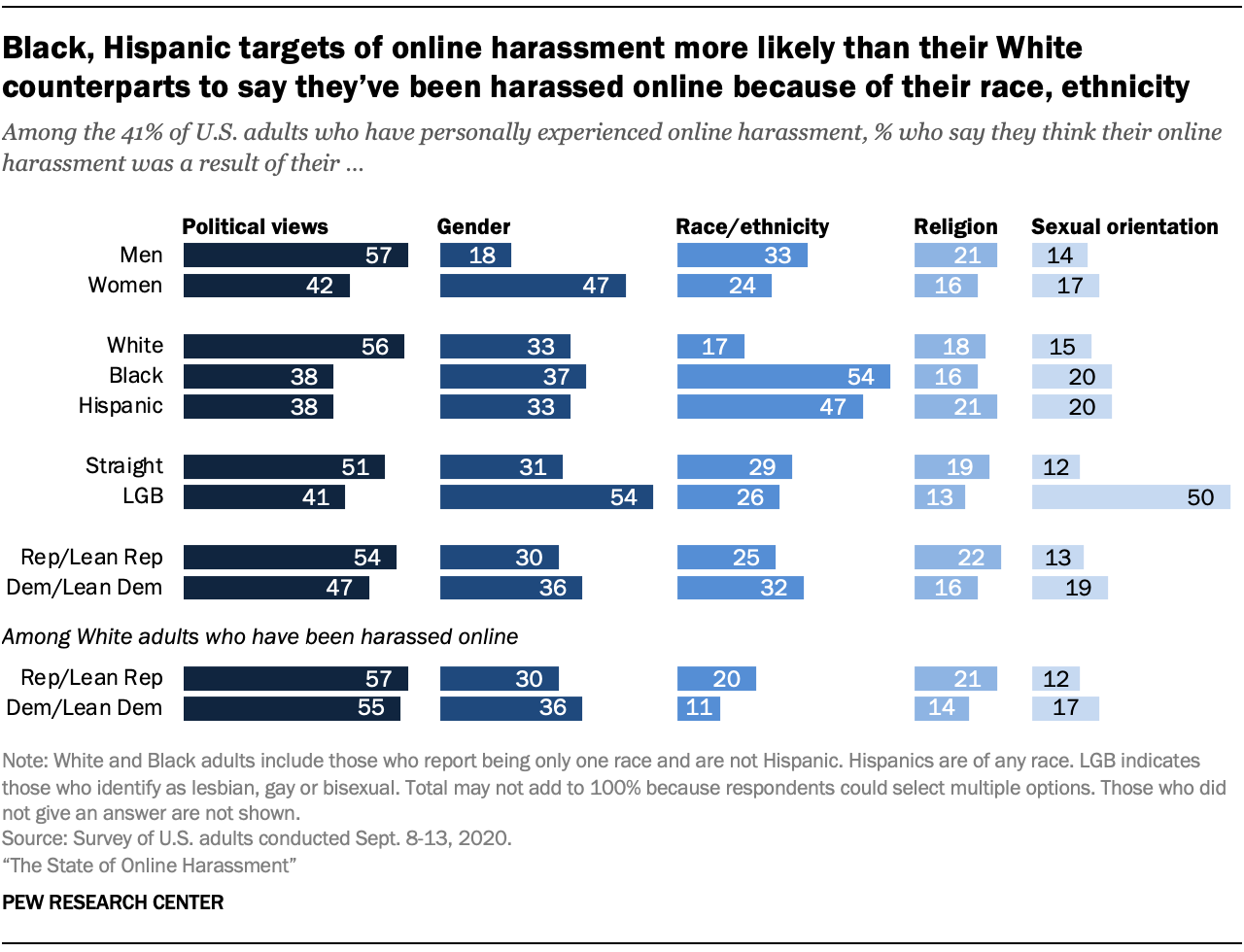

There are several demographic differences regarding who has been harassed online for their gender or their race or ethnicity. Among adults who have been harassed online, roughly half of women (47%) say they think they have encountered harassment online because of their gender, whereas 18% of men who have been harassed online say the same. Similarly, about half or more Black (54%) or Hispanic online harassment targets (47%) say they were harassed due to their race or ethnicity, compared with 17% of White targets.

While small shares overall say their harassment was due to their sexual orientation, 50% of lesbian, gay or bisexual adults who have been harassed online say they think it occurred because of their sexual orientation. 2 By comparison, only 12% of straight online harassment targets say the same. Lesbian, gay or bisexual online harassment targets are also more likely to report having encountered harassment online because of their gender (54%) compared with their straight counterparts (31%).

Men and White adults who have been harassed online are particularly likely to say this harassment was a result of their political views. Harassed men are a full 15 percentage points more likely than their female counterparts to cite political views as the reason they were harassed online (57% vs. 42%). Similarly, White online harassment targets are 18 points more likely than Black or Hispanic targets to point to their political views as the reason they were targeted for abuse online.

And while there are some partisan differences in citing political views as the perceived catalyst for facing harassment, these differences do not hold when accounting for race and ethnicity. For example, White Democrats and Republicans, including independents who lean toward each respective party, who have been harassed are about equally likely to say their political views were the reason they were harassed (55% vs. 57%).

Most online harassment targets say their most recent experience occurred on social media

As was true in previous Center surveys about online harassment, social media continue to be the most commonly cited online venues where harassment takes place. When asked where their most recent experience with online harassment occurred, 75% of targets of this type of abuse say it happened on social media.

By comparison, much smaller shares of this group mention online forums or discussion sites (25%) or texting or messaging apps (24%) as the location where their most recent experience occurred, while about one-in-ten or more cite online gaming, their personal email account or a dating site or app. In total, 41% of targets of online harassment say their most recent experience of harassment spanned more than one venue.

While social media are the most commonly cited online spaces for both men and women to say they have been harassed, women who have been harassed online are more likely than men to say their most recent experience was on social media (a 13 percentage point gap). On the other hand, men are more likely than women to report their most recent experience occurred while they were using an online forum or discussion site or while online gaming (both with a 13-point gap).

Most Americans are critical of how social media companies address online harassment; only a minority say users should be able to hold sites legally responsible

While most Americans feel that harassment and bullying are a problem online, the way to address this issue remains up for debate. The policies used to combat harassment and the transparency in reporting how content is being moderated vary drastically across online platforms. Social media companies have been highly criticized for their current tactics in addressing harassment, with advocates saying these companies should be doing more.

The public is similarly critical of social media companies. When asked to rate how well these companies are addressing online harassment or bullying on their platforms, just 18% say social media companies are doing an excellent or good job. Much larger shares – roughly eight-in-ten – say these companies are doing an only fair or poor job.

Despite most Americans being critical of the job social media companies are doing to address harassment, some are optimistic about a variety of possible solutions asked about in the survey that could be enacted to combat online harassment.

About half of Americans say permanently suspending users if they bully or harass others (51%) or requiring users of these platforms to disclose their real identities (48%) would be very effective in helping to reduce harassment or bullying on social media.

Around four-in-ten say criminal charges for users who bully or harass (43%) or social media companies proactively deleting bullying or harassing posts (40%) would be very effective.

Temporary bans are deemed the least effective solution about which respondents were asked. A third (32%) of Americans say users getting temporarily suspended if they bully or harass others would be a very effective measure against harassment. When it comes to holding social media companies accountable for the harassment on their platforms, few think personal lawsuits should be the solution. A third of adults say people who have been bullied or harassed by others on social media should be able to sue the platforms where the harassment occurred, whereas a much larger share – 63% – believe targets of online abuse should not be able to bring legal action against social media sites.

- The 2014 data was reweighted to be comparable to the data collected in 2017. See the 2017 report’s methodology for more information about how this was done. ↩

- Because of the relatively small sample size and a reduction in precision due to weighting, we are not able to analyze lesbian, gay or bisexual respondents by demographic categories such as gender, age or education. ↩

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

Most Popular

Report materials.

- American Trends Panel Wave 74

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

- Publications

Uses and Abuses of Social Media

Lisa Garbe ( WZB - Berlin Social Science Center), Marc Owen Jones (Hamad bin Khalifa University), David Herbert (UiB) and Lovise Aalen (CMI)

Social media have been hailed as the ultimate democratic tool, enabling users to self-organise and build communities, sometimes even contributing to the fall of dictatorships, as during the Arab Spring. But can social media also reinforce existing power relationships? What happens when access to social media is shut down? When social media are manipulated, so that only one story is shared?

Lovise Aalen

- [email protected]

- +47 41087082

Recent CMI publications:

Refugees find employment in very different settlement contexts.

Tiit Tammaru, Kadi Kalm, Anneli Kährik, Alis Tammur

IS-terror utan ende?

Arne Strand

The role of trust and norms in tax compliance in Africa

Odd-Helge Fjeldstad and Ingrid Hoem Sjursen

Human Development Report 2023-2024 "Breaking the gridlock: Reimagining cooperation in a polarized world"

Unsettling expectations of stay: probationary immigration policies in Canada and Norway

Jessica Schultz

Comparative Migration Studies

The Sudan war: The potential of civil and democratic forces

Munzoul Assal

‘There is No Compulsion in Marriage’. Divorce and Gendered Change in Afghanistan during the Islamic Republic

Torunn Wimpelmann, Masooma Saadat

British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies

Oceanic geographies and maritime heritage in the making: Producing history, memory and territory. International Journal of Heritage Studies (forthcoming)

Edyta Roszko and Tim Winter

Introduction: theorising heritage for the seas

International Journal of Heritage Studies

Research and Advisory Work on Taxation and Public Finance Management in Tanzania 1993-2023

Odd-Helge Fjeldstad

Heritagising the South China Sea: appropriation and dispossession of maritime heritage through museums and exhibitions in Southern China

Edyta Roszko

Courts and Transitional Justice

Oxford Handbook of Comparative Judicial Behaviour

Uncertainty at the needle point: Vaccine hesitancy, trust, and public health communication in Norway during swine flu and COVID-19

Karine Aasgaard Jansen

Vaccine hesitancy in the Nordic countries. Trust and distrust during the COVID-19 pandemic. Editors: Lars Borin, Mia-Marie Hammarlin, Dimitrios Kokkinakis, Fredrik Miegel.

- All Stories

- Journalists

- Expert Advisories

- Media Contacts

- X (Twitter)

- Arts & Culture

- Business & Economy

- Education & Society

- Environment

- Law & Politics

- Science & Technology

- International

- Michigan Minds Podcast

- Michigan Stories

- 2024 Elections

- Artificial Intelligence

- Abortion Access

- Mental Health

Hate speech in social media: How platforms can do better

- Morgan Sherburne

With all of the resources, power and influence they possess, social media platforms could and should do more to detect hate speech, says a University of Michigan researcher.

Libby Hemphill

In a report from the Anti-Defamation League , Libby Hemphill, an associate research professor at U-M’s Institute for Social Research and an ADL Belfer Fellow, explores social media platforms’ shortcomings when it comes to white supremacist speech and how it differs from general or nonextremist speech, and recommends ways to improve automated hate speech identification methods.

“We also sought to determine whether and how white supremacists adapt their speech to avoid detection,” said Hemphill, who is also a professor at U-M’s School of Information. “We found that platforms often miss discussions of conspiracy theories about white genocide and Jewish power and malicious grievances against Jews and people of color. Platforms also let decorous but defamatory speech persist.”

How platforms can do better

White supremacist speech is readily detectable, Hemphill says, detailing the ways it is distinguishable from commonplace speech in social media, including:

- Frequently referencing racial and ethnic groups using plural noun forms (whites, etc.)

- Appending “white” to otherwise unmarked terms (e.g., power)

- Using less profanity than is common in social media to elude detection based on “offensive” language

- Being congruent on both extremist and mainstream platforms

- Keeping complaints and messaging consistent from year to year

- Describing Jews in racial, rather than religious, terms

“Given the identifiable linguistic markers and consistency across platforms, social media companies should be able to recognize white supremacist speech and distinguish it from general, nontoxic speech,” Hemphill said.

The research team used commonly available computing resources, existing algorithms from machine learning and dynamic topic modeling to conduct the study.

“We needed data from both extremist and mainstream platforms,” said Hemphill, noting that mainstream user data comes from Reddit and extremist website user data comes from Stormfront.

What should happen next?

Even though the research team found that white supremacist speech is indentifiable and consistent—with more sophisticated computing capabilities and additional data—social media platforms still miss a lot and struggle to distinguish nonprofane, hateful speech from profane, innocuous speech.

“Leveraging more specific training datasets, and reducing their emphasis on profanity can improve platforms’ performance,” Hemphill said.

The report recommends that social media platforms: 1) enforce their own rules; 2) use data from extremist sites to create detection models; 3) look for specific linguistic markers; 4) deemphasize profanity in toxicity detection; and 5) train moderators and algorithms to recognize that white supremacists’ conversations are dangerous and hateful.

“Social media platforms can enable social support, political dialogue and productive collective action. But the companies behind them have civic responsibilities to combat abuse and prevent hateful users and groups from harming others,” Hemphill said. “We hope these findings and recommendations help platforms fulfill these responsibilities now and in the future.”

More information:

- Report: Very Fine People: What Social Media Platforms Miss About White Supremacist Speech

- Related: Video: ISR Insights Speaker Series: Detecting white supremacist speech on social media

- Podcast: Data Brunch Live! Extremism in Social Media

412 Maynard St. Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1399 Email [email protected] Phone 734-764-7260 About Michigan News

- Engaged Michigan

- Global Michigan

- Michigan Medicine

- Public Affairs

Publications

- Michigan Today

- The University Record

Office of the Vice President for Communications © 2024 The Regents of the University of Michigan

Regulating free speech on social media is dangerous and futile

Subscribe to the center for technology innovation newsletter, niam yaraghi niam yaraghi nonresident senior fellow - governance studies , center for technology innovation @niamyaraghi.

September 21, 2018

Amid recent news about Google’s post 2016 elections meeting , multiple Congressional hearings , and attacks by President Trump , social media platforms and technology companies are facing unprecedented criticism from both parties. According to Gallup’s survey , 79 percent of Americans believe that these companies should be regulated.

We know that an overwhelming majority of technology entrepreneurs subscribe to a liberal ideology . Despite the claims by companies such as Google , I believe that political biases affect how these companies operate. As my colleague Nicol Turner-Lee explains here , “while computer programmers may not create algorithms that start out being discriminatory, the collection and curation of social preferences eventually can become adaptive algorithms that embrace societal biases.” If we accept that the implicit bias of developers could unintentionally lead their algorithms to be discriminatory, then, with the same token, we should also expect the political biases of such programmers to lead to discriminatory algorithms that favor their ideology.

Empirical evidence support this intuition; By analyzing a dataset consisting of 10.1 million U.S. Facebook users, a 2014 study demonstrated that liberal users are less likely than their conservative counterparts to get exposed to news content that oppose their political views. Another analysis of Yahoo! search queries concluded that “more right-leaning a query it is, the more negative sentiments can be found in its search results.”

The First Amendment restricts government censorship

The calls for regulating social media and technology companies are politically motivated. Conservatives who support these policies argue that their freedom of speech is being undermined by social media companies who censor their voice. Conservatives who celebrate constitutional originalism should remember that the First Amendment protects against censorship by government. Social media companies are all private businesses with discretion over the content they wish to promote, and any effort by government to influence what social media platforms promote risks violating the First Amendment.

Moreover, the current position of the conservatives are in direct contrast to their positions on “Fairness Doctrine”. As my colleague Tom Wheeler explains here , “when the Fairness Doctrine was repealed in the Reagan Administration, it was hailed by Republicans as a victory for free speech.” Republicans should apply the same standard to both traditional media and the modern day social media. If they believe requiring TV and radio channels to present a fair balance of both sides is a violation of free speech, how can they favor imposing the exact same requirement on social media platforms?

Furthermore, the government intervention that they propose is potentially more damaging than the problem they want to solve. If conservatives believe that certain businesses have enough power and influence to infringe on their freedom of speech, how can they propose government, a much more powerful and influential entity, to enter this space? While President Trump’s administration and a Republican controlled Congress may set policies that would favor conservatives in the short term, they will also be setting a very dangerous precedent which would allow later governments to interfere with these companies and other news organizations in future. If they believe that today’s Twitter has enough power and will to censor them, they should be terrified of allowing tomorrow’s government to do so.

Breaking UP social media Companies does not help consumers

The second argument that supporters of regulating social media companies make is that these companies have created monopolies and therefore antitrust laws should be used to break them down and allow smaller competitors to emerge. While it is true that these companies have created very large monopolies, we should not neglect the unique nature of social media in which users will benefit the most only if they are a member of a dominant platform. The value of a platform for its users grows with the number of other users. After all, what is the use of Facebook if your friends are not there?

If conservatives genuinely believe in the value of competition and free choice, and at the same time believes that a more conservative social media platform would be of value to consumers, they should start a new platform rather than demanding the existing private platforms to become more inclusive of conservative ideas. Just like cable news channels are built to promote ideologies of a particular political party, social media platforms could also be built to promote conservative values.

Mandating ideological diversity is impossible

Others argue that social media and technology companies should become more ideologically diverse and inclusive by hiring more conservatives. I believe in the value of ideological and intellectual diversity. As an academic, I experience it on a daily basis through my interaction with students and colleagues from many different backgrounds. This helps me polish my ideas and create new and exciting ones. New ideas are more likely to emerge and flourish in an intellectually diverse environment.

However, measuring and mandating ideological diversity is impossible. Ideology is a spectrum, not binary. Rarely anyone agrees with all positions of a single party even if they are a member of it. Although in an extremely polarized political environment, Americans are increasingly favoring the more extreme ends of the political ideologies in both parties, many of the Republicans do not agree with current immigration policies of President Trump, just like many Democrats who do not agree that ICE should be abolished. Unlike other forms of diversity that promote gender, racial, and sexual equality in the work force, political ideology cannot be categorized within a limited number of groups. While we can look at the racial composition of the employees of a company and demand that they hire a representative sample of all races, it is not possible to demand for a representative sample of political ideologies in the workforce.

Acting to increase ideological diversity would be impossible. A candidate would hesitate to disclose party affiliation to an employer who may use it to make hiring decisions. What are the chances that a candidate tries to conceal a conservative ideology during an interview for a six-figure-salary job in an overtly liberal Silicon Valley company? If another company wants to become more diverse by hiring conservatives, would liberal candidates be inclined to present as conservative?

The political bias of social media companies becomes more concerning as more Americans turn to these platforms for receiving news and effectively turn them into news organizations. Despite these concerns, I believe that we should accept such bias as a fact and refrain from regulating social media platforms or mandating them to attain a politically diverse workforce.

Facebook and Google are donors to the Brookings Institution. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions posted in this piece are solely those of the author and not influenced by any donation.

Related Content

Mark MacCarthy

April 9, 2021

John Villasenor

October 27, 2022

Bill Baer, Caitlin Chin-Rothmann

June 1, 2021

Related Books

Bruce L.R. Smith, Jeremy D. Mayer, A. Lee Fritschler

August 11, 2008

James A. Reichley

June 1, 1981

Stephen Hess

March 28, 2017

Social Media Technology Policy & Regulation

Governance Studies

Center for Technology Innovation

Online Only

2:00 pm - 3:00 pm EDT

Nicol Turner Lee

March 28, 2024

Jacob Larson, James S. Denford, Gregory S. Dawson, Kevin C. Desouza

March 26, 2024

- Skip to content

- Skip to navigation

Header Menu

Search form

You are here, why ai struggles to recognize toxic speech on social media.

Automated speech police can score highly on technical tests but miss the mark with people, new research shows.

Facebook says its artificial intelligence models identified and pulled down 27 million pieces of hate speech in the final three months of 2020 . In 97 percent of the cases, the systems took action before humans had even flagged the posts.

That’s a huge advance, and all the other major social media platforms are using AI-powered systems in similar ways. Given that people post hundreds of millions of items every day, from comments and memes to articles, there’s no real alternative. No army of human moderators could keep up on its own.

But a team of human-computer interaction and AI researchers at Stanford sheds new light on why automated speech police can score highly accurately on technical tests yet provoke a lot dissatisfaction from humans with their decisions. The main problem: There is a huge difference between evaluating more traditional AI tasks, like recognizing spoken language, and the much messier task of identifying hate speech, harassment, or misinformation — especially in today’s polarized environment.

Read the study: The Disagreement Deconvolution: Bringing Machine Learning Performance Metrics In Line With Reality

“It appears as if the models are getting almost perfect scores, so some people think they can use them as a sort of black box to test for toxicity,’’ says Mitchell Gordon, a PhD candidate in computer science who worked on the project. “But that’s not the case. They’re evaluating these models with approaches that work well when the answers are fairly clear, like recognizing whether ‘java’ means coffee or the computer language, but these are tasks where the answers are not clear.”

The team hopes their study will illuminate the gulf between what developers think they’re achieving and the reality — and perhaps help them develop systems that grapple more thoughtfully with the inherent disagreements around toxic speech.

Too Much Disagreement

There are no simple solutions, because there will never be unanimous agreement on highly contested issues. Making matters more complicated, people are often ambivalent and inconsistent about how they react to a particular piece of content.

In one study, for example, human annotators rarely reached agreement when they were asked to label tweets that contained words from a lexicon of hate speech. Only 5 percent of the tweets were acknowledged by a majority as hate speech, while only 1.3 percent received unanimous verdicts. In a study on recognizing misinformation, in which people were given statements about purportedly true events, only 70 percent agreed on whether most of the events had or had not occurred.

Despite this challenge for human moderators, conventional AI models achieve high scores on recognizing toxic speech — .95 “ROCAUC” — a popular metric for evaluating AI models in which 0.5 means pure guessing and 1.0 means perfect performance. But the Stanford team found that the real score is much lower — at most .73 — if you factor in the disagreement among human annotators.

Reassessing the Models

In a new study, the Stanford team re-assesses the performance of today’s AI models by getting a more accurate measure of what people truly believe and how much they disagree among themselves.

The study was overseen by Michael Bernstein and Tatsunori Hashimoto , associate and assistant professors of computer science and faculty members of the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HAI). In addition to Gordon, Bernstein, and Hashimoto, the paper’s co-authors include Kaitlyn Zhou, a PhD candidate in computer science, and Kayur Patel, a researcher at Apple Inc.

To get a better measure of real-world views, the researchers developed an algorithm to filter out the “noise” — ambivalence, inconsistency, and misunderstanding — from how people label things like toxicity, leaving an estimate of the amount of true disagreement. They focused on how repeatedly each annotator labeled the same kind of language in the same way. The most consistent or dominant responses became what the researchers call "primary labels," which the researchers then used as a more precise dataset that captures more of the true range of opinions about potential toxic content.

The team then used that approach to refine datasets that are widely used to train AI models in spotting toxicity, misinformation, and pornography. By applying existing AI metrics to these new “disagreement-adjusted” datasets, the researchers revealed dramatically less confidence about decisions in each category. Instead of getting nearly perfect scores on all fronts, the AI models achieved only .73 ROCAUC in classifying toxicity and 62 percent accuracy in labeling misinformation. Even for pornography — as in, “I know it when I see it” — the accuracy was only .79.

Someone Will Always Be Unhappy. The Question Is Who?

Gordon says AI models, which must ultimately make a single decision, will never assess hate speech or cyberbullying to everybody’s satisfaction. There will always be vehement disagreement. Giving human annotators more precise definitions of hate speech may not solve the problem either, because people end up suppressing their real views in order to provide the “right” answer.

But if social media platforms have a more accurate picture of what people really believe, as well as which groups hold particular views, they can design systems that make more informed and intentional decisions.

In the end, Gordon suggests, annotators as well as social media executives will have to make value judgments with the knowledge that many decisions will always be controversial.

“Is this going to resolve disagreements in society? No,” says Gordon. “The question is what can you do to make people less unhappy. Given that you will have to make some people unhappy, is there a better way to think about whom you are making unhappy?”

Stanford HAI's mission is to advance AI research, education, policy and practice to improve the human condition. Learn more .

Why AI Struggles To Recognize Toxic Speech on Social Media - by Edmund L. Andrews - Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence - July 13, 2021

Via : hai.stanford.edu

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Terms of Use

- Copyright Complaints

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

What to Know About the Supreme Court Arguments on Social Media Laws

Both Florida and Texas passed laws regulating how social media companies moderate speech online. The laws, if upheld, could fundamentally alter how the platforms police their sites.

By David McCabe

McCabe reported from Washington.

Social media companies are bracing for Supreme Court arguments on Monday that could fundamentally alter the way they police their sites.

After Facebook, Twitter and YouTube barred President Donald J. Trump in the wake of the Jan. 6, 2021, riots at the Capitol, Florida made it illegal for technology companies to ban from their sites a candidate for office in the state. Texas later passed its own law prohibiting platforms from taking down political content.

Two tech industry groups, NetChoice and the Computer & Communications Industry Association, sued to block the laws from taking effect. They argued that the companies have the right to make decisions about their own platforms under the First Amendment, much as a newspaper gets to decide what runs in its pages.

So what’s at stake?

The Supreme Court’s decision in those cases — Moody v. NetChoice and NetChoice v. Paxton — is a big test of the power of social media companies, potentially reshaping millions of social media feeds by giving the government influence over how and what stays online.

“What’s at stake is whether they can be forced to carry content they don’t want to,” said Daphne Keller, a lecturer at Stanford Law School who filed a brief with the Supreme Court supporting the tech groups’ challenge to the Texas and Florida laws. “And, maybe more to the point, whether the government can force them to carry content they don’t want to.”

If the Supreme Court says the Texas and Florida laws are constitutional and they take effect, some legal experts speculate that the companies could create versions of their feeds specifically for those states. Still, such a ruling could usher in similar laws in other states, and it is technically complicated to accurately restrict access to a website based on location.

Critics of the laws say the feeds to the two states could include extremist content — from neo-Nazis, for example — that the platforms previously would have taken down for violating their standards. Or, the critics say, the platforms could ban discussion of anything remotely political by barring posts about many contentious issues.

What are the Florida and Texas social media laws?

The Texas law prohibits social media platforms from taking down content based on the “viewpoint” of the user or expressed in the post. The law gives individuals and the state’s attorney general the right to file lawsuits against the platforms for violations.

The Florida law fines platforms if they permanently ban from their sites a candidate for office in the state. It also forbids the platforms from taking down content from a “journalistic enterprise” and requires the companies to be upfront about their rules for moderating content.

Proponents of the Texas and Florida laws, which were passed in 2021, say that they will protect conservatives from the liberal bias that they say pervades the platforms, which are based in California.

“People the world over use Facebook, YouTube, and X (the social-media platform formerly known as Twitter) to communicate with friends, family, politicians, reporters, and the broader public,” Ken Paxton, the Texas attorney general, said in one legal brief. “And like the telegraph companies of yore, the social media giants of today use their control over the mechanics of this ‘modern public square’ to direct — and often stifle — public discourse.”

Chase Sizemore, a spokesman for the Florida attorney general, said the state looked “forward to defending our social media law that protects Floridians.” A spokeswoman for the Texas attorney general did not provide a comment.

What are the current rights of social media platforms?

They now decide what does and doesn’t stay online.

Companies including Meta’s Facebook and Instagram, TikTok, Snap, YouTube and X have long policed themselves, setting their own rules for what users are allowed to say while the government has taken a hands-off approach.

In 1997, the Supreme Court ruled that a law regulating indecent speech online was unconstitutional, differentiating the internet from mediums where the government regulates content. The government, for instance, enforces decency standards on broadcast television and radio.

For years, bad actors have flooded social media with misleading information , hate speech and harassment, prompting the companies to come up with new rules over the last decade that include forbidding false information about elections and the pandemic. Platforms have banned figures like the influencer Andrew Tate for violating their rules, including against hate speech.

But there has been a right-wing backlash to these measures, with some conservatives accusing the platforms of censoring their views — and even prompting Elon Musk to say he wanted to buy Twitter in 2022 to help ensure users’ freedom of speech.

What are the social media platforms arguing?

The tech groups say that the First Amendment gives the companies the right to take down content as they see fit, because it protects their ability to make editorial choices about the content of their products.

In their lawsuit against the Texas law, the groups said that just like a magazine’s publishing decision, “a platform’s decision about what content to host and what to exclude is intended to convey a message about the type of community that the platform hopes to foster.”

Still, some legal scholars are worried about the implications of allowing the social media companies unlimited power under the First Amendment, which is intended to protect the freedom of speech as well as the freedom of the press.

“I do worry about a world in which these companies invoke the First Amendment to protect what many of us believe are commercial activities and conduct that is not expressive,” said Olivier Sylvain, a professor at Fordham Law School who until recently was a senior adviser to the Federal Trade Commission chair, Lina Khan.

How does this affect Big Tech’s liability for content?

A federal law known as Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act shields the platforms from lawsuits over most user content. It also protects them from legal liability for how they choose to moderate that content.

That law has been criticized in recent years for making it impossible to hold the platforms accountable for real-world harm that flows from posts they carry, including online drug sales and terrorist videos.

The cases being argued on Monday do not challenge that law head-on. But the Section 230 protections could play a role in the broader arguments over whether the court should uphold the Texas and Florida laws. And the state laws would indeed create new legal liability for the platforms if they take down certain content or ban certain accounts.

Last year, the Supreme Court considered two cases, directed at Google’s YouTube and Twitter, that sought to limit the reach of the Section 230 protections. The justices declined to hold the tech platforms legally liable for the content in question.

What comes next?

The court will hear arguments from both sides on Monday. A decision is expected by June.

Legal experts say the court may rule that the laws are unconstitutional, but provide a road map on how to fix them. Or it may uphold the companies’ First Amendment rights completely.

Carl Szabo, the general counsel of NetChoice, which represents companies including Google and Meta and lobbies against tech regulations, said that if the group’s challenge to the laws fails, “Americans across the country would be required to see lawful but awful content” that could be construed as political and therefore covered by the laws.

“There’s a lot of stuff that gets couched as political content,” he said. “Terrorist recruitment is arguably political content.”

But if the Supreme Court rules that the laws violate the Constitution, it will entrench the status quo: Platforms, not anybody else, will determine what speech gets to stay online.

Adam Liptak contributed reporting.

David McCabe covers tech policy. He joined The Times from Axios in 2019. More about David McCabe

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Media & Tech Articles & More

How to use social media wisely and mindfully, it's time to be clear about how social media affects our relationships and well-being—and what our intentions are each time we log on..

It was no one other than Facebook’s former vice president for user growth, Chamath Palihapitiya, who advised people to take a “hard break” from social media. “We have created tools that are ripping apart the social fabric of how society works,” he said recently .

His comments echoed those of Facebook founding president Sean Parker . Social media provides a “social validation feedback loop (‘a little dopamine hit…because someone liked or commented on a photo or a post’),” he said. “That’s exactly the thing a hacker like myself would come up with because you’re exploiting a vulnerability in human psychology.”

Are their fears overblown? What is social media doing to us as individuals and as a society?

Since over 70 percent of American teens and adults are on Facebook and over 1.2 billion users visit the site daily—with the average person spending over 90 minutes a day on all social media platforms combined—it’s vital that we gain wisdom about the social media genie, because it’s not going back into the bottle. Our wish to connect with others and express ourselves may indeed come with unwanted side effects.

The problems with social media

Social media is, of course, far from being all bad. There are often tangible benefits that follow from social media use. Many of us log on to social media for a sense of belonging, self-expression, curiosity, or a desire to connect. Apps like Facebook and Twitter allow us to stay in touch with geographically dispersed family and friends, communicate with like-minded others around our interests, and join with an online community to advocate for causes dear to our hearts.

Honestly sharing about ourselves online can enhance our feelings of well-being and online social support, at least in the short term. Facebook communities can help break down the stigma and negative stereotypes of illness, while social media, in general, can “serve as a spring board” for the “more reclusive…into greater social integration,” one study suggested.

But Parker and Palihapitiya are on to something when they talk about the addictive and socially corrosive qualities of social media. Facebook “addiction” (yes, there’s a test for this) looks similar on an MRI scan in some ways to substance abuse and gambling addictions. Some users even go to extremes to chase the highs of likes and followers. Twenty-six-year-old Wu Yongning recently fell to his death in pursuit of selfies precariously taken atop skyscrapers.

Facebook can also exacerbate envy . Envy is nothing if not corrosive of the social fabric, turning friendship into rivalry, hostility, and grudges. Social media tugs at us to view each other’s “highlight reels,” and all too often, we feel ourselves lacking by comparison. This can fuel personal growth, if we can turn envy into admiration, inspiration, and self-compassion ; but, instead, it often causes us to feel dissatisfied with ourselves and others.

For example, a 2013 study by Ethan Kross and colleagues showed quite definitively that the more time young adults spent on Facebook, the worse off they felt. Participants were texted five times daily for two weeks to answer questions about their well-being, direct social contact, and Facebook use. The people who spent more time on Facebook felt significantly worse later on, even after controlling for other factors such as depression and loneliness.

Interestingly, those spending significant time on Facebook, but also engaging in moderate or high levels of direct social contact, still reported worsening well-being. The authors hypothesized that the comparisons and negative emotions triggered by Facebook were carried into real-world contact, perhaps damaging the healing power of in-person relationships.

More recently, Holly Shakya and Nicholas Christakis studied 5,208 adult Facebook users over two years, measuring life satisfaction and mental and physical health over time. All these outcomes were worse with greater Facebook use, and the way people used Facebook (e.g., passive or active use, liking, clicking, or posting) didn’t seem to matter.

“Exposure to the carefully curated images from others’ lives leads to negative self-comparison, and the sheer quantity of social media interaction may detract from more meaningful real-life experiences,” the researchers concluded.

How to rein in social media overuse

So, what can we do to manage the downsides of social media? One idea is to log out of Facebook completely and take that “hard break.” Researcher Morten Tromholt of Denmark found that after taking a one-week break from Facebook, people had higher life satisfaction and positive emotions compared to people who stayed connected. The effect was especially pronounced for “heavy Facebook users, passive Facebook users, and users who tend to envy others on Facebook.”

We can also become more mindful and curious about social media’s effects on our minds and hearts, weighing the good and bad. We should ask ourselves how social media makes us feel and behave, and decide whether we need to limit our exposure to social media altogether (by logging out or deactivating our accounts) or simply modify our social media environment. Some people I’ve spoken with find ways of cleaning up their newsfeeds—from hiding everyone but their closest friends to “liking” only reputable news, information, and entertainment sources.

Knowing how social media affects our relationships, we might limit social media interactions to those that support real-world relationships. Instead of lurking or passively scrolling through a never-ending bevy of posts, we can stop to ask ourselves important questions, like What are my intentions? and What is this online realm doing to me and my relationships?

We each have to come to our own individual decisions about social media use, based on our own personal experience. Grounding ourselves in the research helps us weigh the good and bad and make those decisions. Though the genie is out of the bottle, we may find, as Shakya and Christakis put it, that “online social interactions are no substitute for the real thing,” and that in-person, healthy relationships are vital to society and our own individual well-being. We would do well to remember that truth and not put all our eggs in the social media basket.

About the Author

Ravi Chandra

Ravi Chandra is a psychiatrist, writer, and compassion educator in San Francisco, and a distinguished fellow of the American Psychiatric Association. Here’s his linktree .

You May Also Enjoy

This article — and everything on this site — is funded by readers like you.

Become a subscribing member today. Help us continue to bring “the science of a meaningful life” to you and to millions around the globe.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

How the internet changed the way we write – and what to do about it

The usual evolution of English has been accelerated online, leading to a less formal – but arguably more expressive – language than the one we use IRL. So use those emojis wisely …

English has always evolved – that’s what it means to be a living language – and now the internet plays a pivotal role in driving this evolution. It’s where we talk most freely and naturally, and where we generally pay little heed to whether or not our grammar is “correct”.

Should we be concerned that, as a consequence, English is deteriorating? Is it changing at such a fast pace that older generations can’t keep up? Not quite. At a talk in 2013, linguist David Crystal , author of Internet Linguistics, said: “The vast majority of English is exactly the same today as it was 20 years ago.” And his collected data indicated that even e-communication isn’t wildly different: “Ninety per cent or so of the language you use in a text is standard English, or at least your local dialect.”

It’s why we can still read an 18th-century transcript of a speech George Washington gave to his troops and understand it in its entirety, and why grandparents don’t need a translator when sending an email to their grandchildren.

However, the way we communicate – the punctuation (or lack thereof), the syntax, the abbreviations we use – is dependent on context and the medium with which we are communicating. We don’t need to reconcile the casual way we talk in a text or on social media with, say, the way we string together sentences in a piece of journalism, because they’re different animals.

On Twitter, emojis and new-fangled uses of punctuation, for instance, open doors to more nuanced casual expression. For example, the ~quirky tilde pair~ or full. stops. in. between. words. for. emphasis. While you are unlikely to find a breezy caption written in all lowercase and without punctuation in the New York Times, you may well find one in a humorous post published on BuzzFeed .

As the author of the BuzzFeed Style Guide , I crafted a set of guidelines that were flexible and applicable to hard news stories as well as the more lighthearted posts our platform publishes, such as comical lists and takes on celebrity goings-on, as well as to our social media posts. For instance, I decided, along with my team of copy editors, to include a rule that we should put emojis outside end punctuation not inside, because the consensus was that it simply looks cleaner to end a sentence as you normally would and then use an emoji. Our style guide also has comprehensive sections on how to write appropriately about serious topics, such as sexual assault and suicide.

Language shifts and proliferates due to chance and external factors, such as the influence the internet has on slang and commonplace abbreviations. (I believe that “due to” and “because of” can be used interchangeably, because it’s the way we use those phrases in speech; using one rather than the other has no impact on clarity.) So while some of Strunk and White’s famous grammar and usage rules – for example, avoiding the passive voice, never ending a sentence with a preposition – are no longer valuable, it doesn’t mean we’re putting clarity at stake. Sure, there’s no need to hyphenate a modifying phrase that includes an adverb – as in, for example, “a successfully executed plan” – because adverbs by definition modify the words they precede, but putting a hyphen after “successfully” would be no cause for alarm. It’s still a perfectly understandable expression.

Writers and editors, after consulting their house style guide, should rely on their own judgment when faced with a grammar conundrum. Prescriptivism has the potential to make a piece of writing seem dated or stodgy. That doesn’t mean we need to pepper our prose with emojis or every slang word of the moment. It means that by observing the way we’re using words and applying those observations methodically, we increase our chances of connecting with our readers – prepositions at the end of sentences and all. Descriptivism FTW!

- Digital media

- Social media

Independent in talks to take over BuzzFeed and HuffPost in UK and Ireland

‘Like Icarus – now everyone is burnt’: how Vice and BuzzFeed fell to earth

Comments (…), most viewed.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Cybercrime Victimization and Problematic Social Media Use: Findings from a Nationally Representative Panel Study

Eetu marttila.

Economic Sociology, Department of Social Research, University of Turku, Assistentinkatu 7, 20014 Turku, Finland

Aki Koivula

Pekka räsänen, associated data.

The survey data used in this study will be made available through via Finnish Social Science Data Archive (FSD, http://www.fsd.uta.fi/en/ ) after the manuscript acceptance. The data are also available from the authors on scholarly request.

Analyses were run with Stata 16.1. The code is also available from the authors on request for replication purposes.