Early Childhood Education: How to do a Child Case Study-Best Practice

- Creating an Annotated Bibliography

- Lesson Plans and Rubrics

- Children's literature

- Podcasts and Videos

- Cherie's Recommended Library

- Great Educational Articles

- Great Activities for Children

- Professionalism in the Field and in a College Classroom

- Professional Associations

- Pennsylvania Certification

- Manor's Early Childhood Faculty

- Manor Lesson Plan Format

- Manor APA Formatting, Reference, and Citation Policy for Education Classes

- Conducting a Literature Review for a Manor education class

- Manor College's Guide to Using EBSCO Effectively

- How to do a Child Case Study-Best Practice

- ED105: From Teacher Interview to Final Project

- Pennsylvania Initiatives

Description of Assignment

During your time at Manor, you will need to conduct a child case study. To do well, you will need to plan ahead and keep a schedule for observing the child. A case study at Manor typically includes the following components:

- Three observations of the child: one qualitative, one quantitative, and one of your choice.

- Three artifact collections and review: one qualitative, one quantitative, and one of your choice.

- A Narrative

Within this tab, we will discuss how to complete all portions of the case study. A copy of the rubric for the assignment is attached.

- Case Study Rubric (Online)

- Case Study Rubric (Hybrid/F2F)

Qualitative and Quantitative Observation Tips

Remember your observation notes should provide the following detailed information about the child:

- child’s age,

- physical appearance,

- the setting, and

- any other important background information.

You should observe the child a minimum of 5 hours. Make sure you DO NOT use the child's real name in your observations. Always use a pseudo name for course assignments.

You will use your observations to help write your narrative. When submitting your observations for the course please make sure they are typed so that they are legible for your instructor. This will help them provide feedback to you.

Qualitative Observations

A qualitative observation is one in which you simply write down what you see using the anecdotal note format listed below.

Quantitative Observations

A quantitative observation is one in which you will use some type of checklist to assess a child's skills. This can be a checklist that you create and/or one that you find on the web. A great choice of a checklist would be an Ounce Assessment and/or work sampling assessment depending on the age of the child. Below you will find some resources on finding checklists for this portion of the case study. If you are interested in using Ounce or Work Sampling, please see your program director for a copy.

Remaining Objective

For both qualitative and quantitative observations, you will only write down what your see and hear. Do not interpret your observation notes. Remain objective versus being subjective.

An example of an objective statement would be the following: "Johnny stacked three blocks vertically on top of a classroom table." or "When prompted by his teacher Johnny wrote his name but omitted the two N's in his name."

An example of a subjective statement would be the following: "Johnny is happy because he was able to play with the block." or "Johnny omitted the two N's in his name on purpose."

- Anecdotal Notes Form Form to use to record your observations.

- Guidelines for Writing Your Observations

- Tips for Writing Objective Observations

- Objective vs. Subjective

Qualitative and Quantitative Artifact Collection and Review Tips

For this section, you will collect artifacts from and/or on the child during the time you observe the child. Here is a list of the different types of artifacts you might collect:

Potential Qualitative Artifacts

- Photos of a child completing a task, during free play, and/or outdoors.

- Samples of Artwork

- Samples of writing

- Products of child-led activities

Potential Quantitative Artifacts

- Checklist

- Rating Scales

- Product Teacher-led activities

Examples of Components of the Case Study

Here you will find a number of examples of components of the Case Study. Please use them as a guide as best practice for completing your Case Study assignment.

- Qualitatitive Example 1

- Qualitatitive Example 2

- Quantitative Photo 1

- Qualitatitive Photo 1

- Quantitative Observation Example 1

- Artifact Photo 1

- Artifact Photo 2

- Artifact Photo 3

- Artifact Photo 4

- Artifact Sample Write-Up

- Case Study Narrative Example Although we do not expect you to have this many pages for your case study, pay close attention to how this case study is organized and written. The is an example of best practice.

Narrative Tips

The Narrative portion of your case study assignment should be written in APA style, double-spaced, and follow the format below:

- Introduction : Background information about the child (if any is known), setting, age, physical appearance, and other relevant details. There should be an overall feel for what this child and his/her family is like. Remember that the child’s neighborhood, school, community, etc all play a role in development, so make sure you accurately and fully describe this setting! --- 1 page

- Observations of Development : The main body of your observations coupled with course material supporting whether or not the observed behavior was typical of the child’s age or not. Report behaviors and statements from both the child observation and from the parent/guardian interview— 1.5 pages

- Comment on Development: This is the portion of the paper where your professional analysis of your observations are shared. Based on your evidence, what can you generally state regarding the cognitive, social and emotional, and physical development of this child? Include both information from your observations and from your interview— 1.5 pages

- Conclusion: What are the relative strengths and weaknesses of the family, the child? What could this child benefit from? Make any final remarks regarding the child’s overall development in this section.— 1page

- Your Case Study Narrative should be a minimum of 5 pages.

Make sure to NOT to use the child’s real name in the Narrative Report. You should make reference to course material, information from your textbook, and class supplemental materials throughout the paper .

Same rules apply in terms of writing in objective language and only using subjective minimally. REMEMBER to CHECK your grammar, spelling, and APA formatting before submitting to your instructor. It is imperative that you review the rubric of this assignment as well before completing it.

Biggest Mistakes Students Make on this Assignment

Here is a list of the biggest mistakes that students make on this assignment:

- Failing to start early . The case study assignment is one that you will submit in parts throughout the semester. It is important that you begin your observations on the case study before the first assignment is due. Waiting to the last minute will lead to a poor grade on this assignment, which historically has been the case for students who have completed this assignment.

- Failing to utilize the rubrics. The rubrics provide students with guidelines on what components are necessary for the assignment. Often students will lose points because they simply read the descriptions of the assignment but did not pay attention to rubric portions of the assignment.

- Failing to use APA formatting and proper grammar and spelling. It is imperative that you use spell check and/or other grammar checking software to ensure that your narrative is written well. Remember it must be in APA formatting so make sure that you review the tutorials available for you on our Lib Guide that will assess you in this area.

- << Previous: Manor College's Guide to Using EBSCO Effectively

- Next: ED105: From Teacher Interview to Final Project >>

- Last Updated: Apr 3, 2024 2:53 PM

- URL: https://manor.libguides.com/ece

Manor College Library

700 fox chase road, jenkintown, pa 19046, (215) 885-5752, ©2017 manor college. all rights reserved..

Click here to search FAQs

- History of the College

- Purpose and Mandate

- Act and Regulations

- By-laws and Policies

- Council and Committees

- Annual Reports

- News Centre

- Fair Registration Practices Report

- Executive Leadership Team

- Career Opportunities

- Accessibility

- About RECEs

- Public Register

- Professional Regulation

- Code and Standards

- Unregulated Persons

- Approval of Education Programs

- CPL Program

- Standards in Practice

- Sexual Abuse Prevention Program

- New Member Resources

- Wellness Resources

- Annual Meeting of Members

- Beyond the College

- Apply to the College

- Who Is Required to Be a Member?

- Requirements and FAQs for Registration

- Education Programs

- Request for Review by the Registration Appeals Committee FAQs

- Individual Assessment of Educational Qualifications

Case Studies and Scenarios

Case studies.

Each case study describes the real experience of a Registered Early Childhood Educator. Each one profiles a professional dilemma, incorporates participants with multiple perspectives and explores ethical complexities. Case studies may be used as a source for reflection and dialogue about RECE practice within the framework of the Code of Ethics and Standards of Practice.

Scenarios are snapshots of experiences in the professional practice of a Registered Early Childhood Educator. Each scenario includes a series of questions meant to help RECEs reflect on the situation.

Case Study 1: Sara’s Confusing Behaviour

Case study 2: getting bumps and taking lumps, case study 3: no qualified staff, case study 4: denton’s birthday cupcakes, case study 5: new kid on the block, case study 6: new responsibilities and challenges, case study 7: valuing inclusivity and privacy, case study 8: balancing supervisory responsibilities, case study 9: once we were friends, scenarios, communication and collaboration.

Barbara, an RECE, is working as a supply staff at various centres across the city. During her week at a centre where she helps out in two different rooms each day, she finds that her experience in the school-age program isn’t as straightforward as when she was in the toddler room. Barbara feels completely lost in this program.

Do You Really Know Who Your Friends Are?

Joe is an RECE at an elementary school and works with children between the ages of nine and 12 years old. One afternoon, he finds a group of children huddled around the computer giggling and whispering. Joe quickly discovers they’re going through his party photos on Facebook as one of the children’s parents recently added him as a friend.

Conflicting Approaches

Amina, an experienced RECE, has recently started a new position with a child care centre. She’s assigned to work in the infant room with two colleagues who have worked in the room together for ten years. As Amina settles into her new role, she is taken aback by some of the child care approaches taken by her colleagues.

What to do about Lisa?

Shane, an experienced supervisor at a child care centre, receives a complaint about an RECE who had roughly handled a child earlier that day. The interaction had been witnessed by a parent who confronted the RECE. After some words were exchanged, the RECE left in tears.

Duty to Report

Zoë works as an RECE in a drop-in program at a family support centre. She has a great rapport for a family over a 10-month period and beings to notice a change in the mom and child. One day, as the child is getting dressed to go home for the day, she notices something alarming and brings it to the attention of her supervisor.

Posting on Social Media

Allie, an RECE who has worked at the same child care centre for the last three years, recently started a private social media group to collaborate and discuss programming ideas. As the group takes a negative turn with rude and offensive comments, it’s brought to her supervisor’s attention.

- Our Mission

Making Learning Relevant With Case Studies

The open-ended problems presented in case studies give students work that feels connected to their lives.

To prepare students for jobs that haven’t been created yet, we need to teach them how to be great problem solvers so that they’ll be ready for anything. One way to do this is by teaching content and skills using real-world case studies, a learning model that’s focused on reflection during the problem-solving process. It’s similar to project-based learning, but PBL is more focused on students creating a product.

Case studies have been used for years by businesses, law and medical schools, physicians on rounds, and artists critiquing work. Like other forms of problem-based learning, case studies can be accessible for every age group, both in one subject and in interdisciplinary work.

You can get started with case studies by tackling relatable questions like these with your students:

- How can we limit food waste in the cafeteria?

- How can we get our school to recycle and compost waste? (Or, if you want to be more complex, how can our school reduce its carbon footprint?)

- How can we improve school attendance?

- How can we reduce the number of people who get sick at school during cold and flu season?

Addressing questions like these leads students to identify topics they need to learn more about. In researching the first question, for example, students may see that they need to research food chains and nutrition. Students often ask, reasonably, why they need to learn something, or when they’ll use their knowledge in the future. Learning is most successful for students when the content and skills they’re studying are relevant, and case studies offer one way to create that sense of relevance.

Teaching With Case Studies

Ultimately, a case study is simply an interesting problem with many correct answers. What does case study work look like in classrooms? Teachers generally start by having students read the case or watch a video that summarizes the case. Students then work in small groups or individually to solve the case study. Teachers set milestones defining what students should accomplish to help them manage their time.

During the case study learning process, student assessment of learning should be focused on reflection. Arthur L. Costa and Bena Kallick’s Learning and Leading With Habits of Mind gives several examples of what this reflection can look like in a classroom:

Journaling: At the end of each work period, have students write an entry summarizing what they worked on, what worked well, what didn’t, and why. Sentence starters and clear rubrics or guidelines will help students be successful. At the end of a case study project, as Costa and Kallick write, it’s helpful to have students “select significant learnings, envision how they could apply these learnings to future situations, and commit to an action plan to consciously modify their behaviors.”

Interviews: While working on a case study, students can interview each other about their progress and learning. Teachers can interview students individually or in small groups to assess their learning process and their progress.

Student discussion: Discussions can be unstructured—students can talk about what they worked on that day in a think-pair-share or as a full class—or structured, using Socratic seminars or fishbowl discussions. If your class is tackling a case study in small groups, create a second set of small groups with a representative from each of the case study groups so that the groups can share their learning.

4 Tips for Setting Up a Case Study

1. Identify a problem to investigate: This should be something accessible and relevant to students’ lives. The problem should also be challenging and complex enough to yield multiple solutions with many layers.

2. Give context: Think of this step as a movie preview or book summary. Hook the learners to help them understand just enough about the problem to want to learn more.

3. Have a clear rubric: Giving structure to your definition of quality group work and products will lead to stronger end products. You may be able to have your learners help build these definitions.

4. Provide structures for presenting solutions: The amount of scaffolding you build in depends on your students’ skill level and development. A case study product can be something like several pieces of evidence of students collaborating to solve the case study, and ultimately presenting their solution with a detailed slide deck or an essay—you can scaffold this by providing specified headings for the sections of the essay.

Problem-Based Teaching Resources

There are many high-quality, peer-reviewed resources that are open source and easily accessible online.

- The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science at the University at Buffalo built an online collection of more than 800 cases that cover topics ranging from biochemistry to economics. There are resources for middle and high school students.

- Models of Excellence , a project maintained by EL Education and the Harvard Graduate School of Education, has examples of great problem- and project-based tasks—and corresponding exemplary student work—for grades pre-K to 12.

- The Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning at Purdue University is an open-source journal that publishes examples of problem-based learning in K–12 and post-secondary classrooms.

- The Tech Edvocate has a list of websites and tools related to problem-based learning.

In their book Problems as Possibilities , Linda Torp and Sara Sage write that at the elementary school level, students particularly appreciate how they feel that they are taken seriously when solving case studies. At the middle school level, “researchers stress the importance of relating middle school curriculum to issues of student concern and interest.” And high schoolers, they write, find the case study method “beneficial in preparing them for their future.”

- Eligibility

- Support Agencies

- Session reports

- Change of circumstances

- Program review

- First Nations children can get more hours of subsidised care

- List of registered child care software

- Session reports for previous financial years

- Providing care to relatives

- Third-party payment of gap fees

- Overpayments and debts

- Balancing Child Care Subsidy

- About the child wellbeing subsidy

- Identifying a child at risk

- Examples to help you understand when a child is at risk

- Talking with the family

- Establishing eligibility for child wellbeing

- Reporting obligations

- Issuing a child wellbeing certificate

- Applying for a child wellbeing determination

- Grandparents

- Temporary financial hardship

- Transition to work

- Special circumstances grant

- Priority areas for disadvantaged and vulnerable communities grant

- Community Child Care Fund restricted grant review

- Notification of serious incidents

- Restricted grant: notification of Work Health and Safety incidents

- Connected Beginnings sites

- Priority areas for limited supply grant

- Business support

- Inclusion Agencies

- Inclusion Development Fund

- Inclusion Support Portal

- Inclusion Support Program review

- About the approval process

- Check your eligibility

- Get ready to apply

- Submit your application

- After you apply

- Add, remove or relocate a service

- Suspension of approvals

- Family Assistance Law

- Persons with management or control obligations

- Persons with management or control by organisation type

- Fit and proper

- Working with children checks

- Inducement and advertising at your service

- Electronic payment of gap fees

- Financial reporting obligations for large providers

- Family Assistance Law civil penalty provisions

- What to do if you get a section 158 or 67FH notice

- Compliance Pilot

- Children who are on holiday

- Educators who are not providing care

- Caring for relatives – the less than 50% rule

- Entitlement to CCS or ACCS when caring for own children or siblings

- Charging fees

- Fit and proper person

- Background checks

- Reporting actual attendance times

- Past enforcement action registers

- Collecting gap fees

- Notifications and reporting

- Record keeping

- Support by region

- Emergency support by region

- National Children’s Education and Care Workforce Strategy

- Paid practicum subsidy

- Practicum exchange

- Professional development subsidy

- How to acquit professional development and paid practicum subsidies

- Stakeholder kit: professional development for early childhood workforce

- Support for early childhood teachers and educators

- Educator discounts

- Finding staff

- Approved learning frameworks

- Expert advisory group

- Preschool Outcomes Measure

- Preschool Reform Funding Agreement

- Previous funding arrangements

- National vision for early childhood education and care frequently asked questions

- Early Years Strategy

- Australian Competition and Consumer Commission child care price inquiry

- Productivity Commission inquiry into ECEC

- December quarter 2023

- September quarter 2023

- June quarter 2023

- March quarter 2023

- December quarter 2022

- September quarter 2022

- June quarter 2022

- March quarter 2022

- December quarter 2021

- September quarter 2021

- June quarter 2021

- March quarter 2021

- December quarter 2020

- September quarter 2020

- March quarter 2020

- December quarter 2019

- September quarter 2019

- June quarter 2019

- March quarter 2019

- December quarter 2018

- Financial year 2018-19

- September quarter 2018

- 2021 results

- 2016 results

- 2013 results

- 2010 results

- Pre-2010 results

- Australian Early Development Census

- Case Study: Lady Gowrie Tasmania pathway to traineeship program

- Case study: From the Ground Up

- Case study: Jenny’s Early Learning Centre’s Bendigo Traineeships

- Case study: Ngroo Education Aboriginal Corporation, western Sydney

- Online learning

- Provider tool kit

- Announcements

Early childhood case studies

Our case studies showcase successful early childhood education and care initiatives.

From the Ground Up leadership program inspires early learning educators.

Traineeships a winner for the early childhood workforce.

Tasmanian program gives taste of life working in early childhood education and care.

Stronger local communities by linking support services through playgroups

Eager to Learn: Educating Our Preschoolers (2001)

Chapter: 9	findings, conclusions, and recommendations, 9 findings, conclusions, and recommendations.

T HE RESEARCH ON EARLY CHILDHOOD learning and program effectiveness reviewed in this report provides some very powerful findings:

Young children are capable of understanding and actively building knowledge, and they are highly inclined to do so. While there are developmental constraints on children’s competence, those constraints serve as a ceiling below which there is enormous room for variation in growth, skill acquisition, and understanding.

Development is dependent on and responsive to experience, allowing children to grow far more quickly in domains in which a rich experiential base and guided exposure to complex thinking are available than in those where they receive no such support. Environment—including cultural context—exerts a large influence on both cognitive and emotional development. Genetic endowment is far more responsive to experience than was once thought. Rapid growth of the brain in the early years provides an opportunity for the environment to influence the physiology of development.

Education and care in the early years are two sides of the same coin. Research suggests that secure attachment improves

both social competence and the ability to exploit learning opportunities.

Furthermore, research on early childhood curricula and pedagogy has implications for how early childhood programs can effectively promote development:

Cognitive, social-emotional (mental health), and physical development are complementary, mutually supportive areas of growth all requiring active attention in the preschool years. Social skills and physical dexterity influence cognitive development, just as cognition plays a role in children’s social understanding and motor competence. All are therefore related to early learning and later academic achievement and are necessary domains of early childhood pedagogy.

Responsive interpersonal relationships with teachers nur ture young children’s dispositions to learn and their emerging abilities. Social competence and school achievement are influenced by the quality of early teacher-child relationships, and by teachers’ attentiveness to how the child approaches learning.

While no single curriculum or pedagogical approach can be identified as best, children who attend well-planned, high- quality early childhood programs in which curriculum aims are specified and integrated across domains tend to learn more and are better prepared to master the complex demands of formal schooling. Particular findings of relevance in this regard include the following:

Children who have a broad base of experience in domain-specific knowledge (for example, in mathematics or an area of science) move more rapidly in acquiring more complex skills

More extensive language development—such as a rich vocabulary and listening comprehension—is related to early literacy learning.

Children are better prepared for school when early childhood programs expose them to a variety of classroom structures, thought processes, and discourse patterns. This does not mean adopting the methods and curriculum of the elementary school; rather it is a matter of providing children with a mix of whole

class, small group, and individual interactions with teachers, the experience of different kinds of discourse patterns, and such mental strategies as categorizing, memorizing, reasoning, and metacognition.

While the committee does not endorse any particular cur riculum, the cognitive science literature suggests principles of learning that should be incorporated into any curriculum:

Teaching and learning will be most effective if they engage and build on children’s existing understandings.

Key concepts involved in each domain of preschool learning (e.g., representational systems in early literacy, the concept of quantity in mathematics, causation in the physical world) must go hand in hand with information and skill acquisition (e.g., identifying numbers and letters and acquiring information about the natural world).

Metacognitive skill development allows children to solve problems more effectively. Curricula that encourage children to reflect, predict, question, and hypothesize (examples: How many will there be after two numbers are added? What happens next in the story? Will it sink or float?) set them on course for effective, engaged learning.

young children who are living in circumstances that place them at greater risk of school failure—including poverty, low level of maternal education, maternal depression, and other fac tors that can limit their access to opportunities and resources that enhance learning and development—are much more likely to succeed in school if they attend well-planned, high-quality early childhood programs. Many children, especially those in low-income households, are served in child care programs of such low quality that learning and development are not enhanced and may even be jeopardized.

The importance of teacher responsiveness to children’s differences, knowledge of children’s learning processes and capabilities, and the multiple developmental goals that a quality pre-

school program must address simultaneously all point to the centrality of teacher education and preparation.

The professional development of teachers is related to the quality of early childhood programs, and program quality pre dicts developmental outcomes for children. Formal early childhood education and training has been linked consistently to positive caregiver behaviors. The strongest relationship is found between the number of years of education and training and the appropriateness of a teacher’s classroom behavior.

Programs found to be highly effective in the United States and exemplary programs abroad actively engage teachers and provide high-quality supervision. Teachers are trained and encouraged to reflect on their practice and on the responsiveness of their children to classroom activities, and to revise and plan their teaching accordingly.

Both class size and adult-child ratios are correlated with greater program effects. Low ratios of children to adults are associated with more extensive teacher-child interaction, more individualization, and less restrictive and controlling teacher behavior. Smaller group size has been associated with more child initiations, more opportunities for teachers to work on extending language, mediating children’s social interactions, and encouraging and supporting exploration and problem solving.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

What is now known about the potential of the early years, and of the promise of high-quality preschool programs to help realize that potential for all children, stands in stark contrast to practice in many—perhaps most—early childhood settings. How can we bring what we know to bear on what we do?

A committee of the National Research Council recently addressed that question with regard to K-12 education (National Research Council, 1999). While the focus of this report differs from theirs, the conceptual framework for using research knowledge to influence educational practice applies. In this model, the impact of research knowledge on classroom practice—the ultimate goal—is mediated through four arenas, as depicted in Fig-

FIGURE 9–1 Arenas through which research knowledge influences classroom practice.

ure 9–1 . When teachers are directly engaged in using research-based programs or curricula, the effect can be direct. This is the case in some model programs. But if research knowledge is to be used systematically in early childhood education and care programs, preservice and in-service education that effectively transmits that knowledge to those who staff the programs will be required.

While we have argued that the teacher is central, effective teachers work with curricula and teaching materials. In Chapter 5 we refer to exemplary curricula that incorporate research knowledge. Changing practice requires that teachers know about, and have access to, a store of teaching materials.

Quality preschool programs can be encouraged or thwarted by public policy. Regulations and standards can incorporate research knowledge to put a floor under program quality. Public funding and the rules that shape its availability can encourage quality above that floor, and can ensure accessibility to those most in need. And finally, program administrators and teachers, as well as policy makers, are ultimately accountable to parents and to the

public. Parents’ expectations of, and support for, preschool programs, as well as their participation in activities that support early development, can contribute to program success.

The chance of effectively changing early childhood education will increase if the four arenas that influence practice are addressed simultaneously and in a mutually supportive fashion. The committee’s recommendations address each of these four arenas of influence.

Professional Development

At the heart of the effort to promote quality preschool, from the committee’s perspective, is a substantial investment in the education and training of preschool teachers.

Recommendation 1: Each group of children in an early childhood education and care program should be assigned a teacher who has a bachelor’s degree with specialized education related to early childhood (e.g., developmental psychology, early childhood education, early childhood special education). Achieving this goal will require a significant public investment in the professional development of current and new teachers.

Sadly, there is a great disjunction between what is optimal pedagogically for children’s learning and development and the level of preparation that currently typifies early childhood educators. Progress toward a high-quality teaching force will require substantial public and private support and incentive systems, including innovative educational programs, scholarship and loan programs, and compensation commensurate with the expectations of college graduates.

Recommendation 2: Education programs for teachers should provide them with a stronger and more specific foundational knowledge of the development of children’s social and affective behavior, thinking, and language.

Few programs currently do. This foundation should be linked to teachers’ knowledge of mathematics, science, linguistics, literature, etc., as well as to instructional practices for young children.

Recommendation 3: Teacher education programs should require mastery of information on the pedagogy of teaching preschool-aged children, including:

Knowledge of teaching and learning and child development and how to integrate them into practice.

Information about how to provide rich conceptual experiences that promote growth in specific content areas, as well as particular areas of development, such as language (vocabulary) and cognition (reasoning).

Knowledge of effective teaching strategies, including organizing the environment and routines so as to promote activities that build social-emotional relationships in the classroom.

Knowledge of subject-matter content appropriate for preschool children and knowledge of professional standards in specific content areas.

Knowledge of assessment procedures (observation/performance records, work sampling, interview methods) that can be used to inform instruction.

Knowledge of the variability among children, in terms of teaching methods and strategies that may be required, including teaching children who do not speak English, children from various economic and regional contexts, and children with identified disabilities.

Ability to work with teams of professionals.

Appreciation of the parents’ role and knowledge of methods of collaboration with parents and families.

Appreciation of the need for appropriate strategies for accountability.

Recommendation 4: A critical component of preservice preparation should be a supervised, relevant student teaching or internship experience in which new teachers receive ongoing guidance and feedback from a qualified supervisor.

There are a number of models (e.g., National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education) that suggest the value of this sort of supervised student teaching experience. A principal goal of this experience should be to develop the student teacher’s ability to integrate and apply the knowledge base in practice. Col-

laborative support by the teacher preparation institution and the field placement is essential. Supervision of this experience should be shared by a master teacher and a regular or clinical university faculty member.

Recommendation 5: All early childhood education and child care programs should have access to a qualified supervisor of early childhood education.

Teachers should be provided with opportunities to reflect on practice with qualified supervisors. This supervisor should be both an expert teacher of young children and an expert teacher mentor. Such supervisors are needed to provide in-service collaborative experiences, in-service materials (including interactive videodisc materials), and professional development opportunities directed toward improvement of early childhood pedagogy.

Recommendation 6: Federal and state departments of education, human services, and other agencies interested in young children and their families should initiate programs of research and development aimed at learning more about effective preparation of early childhood teachers.

Of particular concern are strategies directed toward bringing experienced early childhood educators, such as child care providers and prekindergarten and Head Start teachers, into compliance with standards for higher education and certification. Such programs should ensure that the field takes full advantage of the knowledge and expertise of existing staff and builds on diversity and strong community bonds represented in the current early childhood care and education work force. At the same time, it should assure that the fields of study described above are mastered by those in the existing workforce. These programs should include development of materials for early childhood professional education. Material development should entail cycles of field testing and revision to assure effectiveness.

Recommendation 7: The committee recommends the development of demonstration schools for professional development.

Many people, including professional educators of older chil-

dren, do not know what an early childhood program should look like, what should be taught, or the kind of pedagogical strategies that are most effective. Demonstration schools would provide contextual understanding of these issues.

The Department of Education should collaborate with universities in developing the demonstration schools and in using them as sites for ongoing research:

on the efficacy of various models, including pairing demonstration schools in partnership with community programs, and pairing researchers and in-service teachers with exemplary community-based programs;

to identify conditions under which the gains of mentoring, placement of pre-service teachers in demonstration schools, and supervised student teaching can be sustained once teachers move into community-based programs.

Educational Materials

Good teachers must be equipped with good curricula. The content of early childhood curricula should be organized systematically into a coherent program with overarching objectives integrated across content and developmental areas. They should include multiple activities, such as systematic exploration and representation, planning and problem solving, creative expression, oral expression, and the ability and willingness to listen to and incorporate information presented by a teacher, sociodramatic and exercise play, and arts activities.

Important curriculum areas are often omitted from early education programs, although there is research to support their inclusion (provided they are addressed in an appropriate manner). Methods of scientific investigation, number concepts, phonological awareness, cultural knowledge, languages, and computer technology all fall into this category.

Because children differ in so many respects, teaching strategies used with any curriculum, from the committee’s perspective, need to be flexibly adapted to meet the specific needs and prior knowledge and understanding of individual children. Embedded in the curriculum should be opportunities to assess children’s

prior understanding and mastery of the skills and knowledge being taught.

Teachers will also need to provide different levels of instruction in activities and use a range of techniques, including direct instruction, scaffolding, indirect instruction (taking advantage of moments of opportunity), and opportunities for children to learn on their own (self-directed learning). The committee believes it is particularly important to maintain children’s enthusiasm for learning by integrating their self-directed interests with the teacher-directed curriculum.

Recommendation 8: The committee recommends that the U.S. Department of Education, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and their equivalents at the state level fund efforts to develop, design, field test, and evaluate curricula that incorporate what is known about learning and thinking in the early years, with companion assessment tools and teacher guides.

Each curriculum should emphasize what is known from research about children’s thinking and learning in the area it addresses. Activities should be included that enable children with different learning styles and strengths to learn.

Each curriculum should include a companion guide for teachers that explains the teaching goals, alerts the teacher to common misconceptions, and suggests ways in which the curriculum can be used flexibly for students at different developmental levels. In the teacher’s guide, the description of methods of assessment should be linked to instructional planning so that the information acquired in the process of assessment can be used as a basis for making pedagogical decisions at the level of both the group and the individual child.

Recommendation 9: The committee recommends that the U.S. Department of Education and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services support the use of effective technology, including videodiscs for preschool teachers and Internet communication groups.

The process of early childhood education is one in which interaction between the adult/teacher and the child/student is the

most critical feature. Opportunities to see curriculum and pedagogy in action are likely to promote understanding of complexity and nuance not easily communicated in the written word. Internet communication groups could provide information on curricula, results of field tests, and opportunities for teachers using a common curriculum to discuss experiences, query each other, and share ideas.

States can play a significant role in promoting program quality with respect to both teacher preparation and curriculum and pedagogy.

Recommendation 10: All states should develop program standards for early childhood programs and monitor their implementation. These standards should recognize the variability in the development of young children and adapt kindergarten and primary programs, as well as preschool programs, to this diversity. This means, for instance, that kindergartens must be readied for children. In some schools, this will require smaller class sizes and professional development for teachers and administrators regarding appropriate teaching practice, so that teachers can meet the needs of individual children, rather than teaching to the “average” child. The standards should outline essential components and should include, but not be limited to, the following categories:

School-home relationships;

Class size and teacher-student ratios;

Specification of pedagogical goals, content, and methods;

Assessment for instructional improvement;

Educational requirements for early childhood educators; and

Monitoring quality/external accountability.

Recommendation 11: Because research has identified content that is appropriate and important for inclusion in early childhood programs, content standards should be developed

and evaluated regularly to ascertain whether they adhere to current scientific understanding of children’s learning.

The content standards should ensure that children have access to rich and varied opportunities to learn in areas that are now omitted from many curricula—such as phonological awareness, number concepts, methods of scientific investigation, cultural knowledge, and language.

Recommendation 12: A single career ladder for early childhood teachers, with differentiated pay levels, should be specified by each state.

This career ladder should include, at a minimum, teaching assistants (with child development associate certification), teachers (with bachelor’s degrees), and supervisors.

Recommendation 13: The committee recommends that the federal government fund well-planned, high-quality center-based preschool programs for all children at high risk of school failure.

Such programs can prevent school failure and significantly enhance learning and development in ways that benefit the entire society.

Policies that support the provision of quality preschool on a broad scale are unlikely without widespread public support. To engender that support, it is important for the public to understand both the potential of the preschool years, and the quality of programming required to realize that potential.

Recommendation 14: Organizations and government bodies concerned with the education of young children should actively promote public understanding of early childhood education and care.

Beliefs that are at odds with scientific understanding—that maturation automatically accounts for learning, for example, or that children can learn concrete skills only through drill and practice—must be challenged. Systematic and widespread public

education should be undertaken to increase public awareness of the importance of providing stimulating educational experiences in the lives of all young children. The message that the quality of children’s relationships with adult teachers and child care providers is critical in preparation for elementary school should be featured prominently in communication efforts. Parents and other caregivers, as well as the public, should be the targets of such efforts.

Recommendation 15: Early childhood programs and centers should build alliances with parents to cultivate complementary and mutually reinforcing environments for young children at home and at the center.

FUTURE RESEARCH NEEDS

Research on early learning, child development, and education can and has influenced the development of early childhood curriculum and pedagogy. But the influences are mutual. By evaluating outcomes of early childhood programs we have come to understand more about children’s development and capacities. The committee believes that continued research efforts along both these lines can expand understanding of early childhood education and care, and the ability to influence them for the better.

Research on Early Childhood Learning and Development

Although it is apparent that early experiences affect later ones, there are a number of important developmental questions to be studied regarding how, when, and which early experiences support development and learning.

Recommendation 16: The committee recommends a broad empirical research program to better understand:

The range of inputs that can contribute to supporting environments that nurture young children’s eagerness to learn;

Development of children’s capacities in the variety of cog-

nitive and socioemotional areas of importance in the preschool years, and the contexts that enhance that development;

The components of adult-child relationships that enhance the child’s development during the preschool years, and experiences affecting that development for good or for ill;

Variation in brain development, and its implications for sensory processing, attention, and regulation;

The implications of developmental disabilities for learning and development and effective approaches for working with children who have disabilities;

With regard to children whose home language is not English, the age and level of native language mastery that is desirable before a second language is introduced and the trajectory of second language development.

Research on Programs and Curricula

Recommendation 17: The next generation of research must examine more rigorously the characteristics of programs that produce beneficial outcomes for all children. In addition, research is needed on how programs can provide more helpful structures, curricula, and methods for children at high risk of educational difficulties, including children from low-income homes and communities, children whose home language is not English, and children with developmental and learning disabilities.

Much of the program research has focused on economically disadvantaged children because they were the targets of early childhood intervention efforts. But as child care becomes more widespread, it becomes more important to understand the components of early childhood education that have developmental benefits for all children.

With respect to disadvantaged children, we know that quality intervention programs are effective, but better understanding the features that make them effective will facilitate replication on a large scale. The Abecedarian program, for example, shows many developmental gains for the children who participate. But in addition to the educational activities, there is a health and nutrition component. And child care workers are paid at a level

comparable to local public school teachers, with a consequent low turnover rate in staff. Whether the program effect is caused by the education component, the health component, or stability of caregiver, or some necessary combination of the three, is not possible to assess. Research on programs for this population should pay careful attention to home-school partnerships and their effect, since this is an aspect of the programs that research suggests is important.

Research on programs for any population of children should examine such program variations as age groupings, adult-child ratios, curricula, class size, looping, and program duration. These questions can best be answered through random assignment, longitudinal studies. Such studies raise concerns because some children receive better services than others, and because they are expensive. However, random assignment between programs that have very similar quality features, but vary on a single dimension (a math curriculum, for example, or class size) would seem less controversial. The cost of conducting such research must, of course, be weighed against the benefits. Given the dramatic expansion in the hours that children spend in out-of-home care in the preschool years, new knowledge can have a very high payoff.

Research is also needed on the interplay between an individual child’s characteristics, the immediate contexts of the home and classroom, and the larger contexts of the formal school environment in developing and assessing curricula. An important line of research is emerging in this area and needs continued support.

Recommendation 18: A broad program of research and development should be undertaken to advance the state of the art of assessment in three areas: (1) classroom-based assessment to support learning (including studies of the impact of methods of instructional assessment on pedagogical technique and children’s learning), (2) assessment for diagnostic purposes, and (3) assessment of program quality for accountability and other reasons of public policy.

All assessments, and particularly assessments for accountability, must be used carefully and appropriately if they are to resolve, and not create, educational problems. Assessment of young

children poses greater challenges than people generally realize. The first five years of life are a time of incredible growth and learning, but the course of development is uneven and sporadic. The status of a child’s development as of any given day can change very rapidly. Consequently assessment results—in particular, standardized test scores that reflect a given point in time— can easily misrepresent children’s learning.

Assessment itself is in a state of flux. There is widespread dissatisfaction with traditional norm-referenced standardized tests, which are based on early 20th century psychological theory. There are a number of promising new approaches to assessment, among them variations on the clinical interview and performance assessment, but the field must be described as emergent. Much more research and development are needed for a productive fusion of assessment and instruction to occur and if the potential benefits of assessment for accountability are to be fully realized.

Research on Ways to Create Universal High Quality

The growing consensus regarding the importance of early education stands in stark contrast to the disparate system of care and education available to children in the United States in the preschool years. America’s programs for preschoolers vary widely in quality, content, organization, sponsorship, source of funding, relationship to the public schools, and government regulation.

As the nation moves toward voluntary universal early childhood programs, parents, and public officials face important policy choices, choices that should be informed by careful research.

Recommendation 19: Research to fully develop and evaluate alternatives for organizing, regulating, supporting, and financing early childhood programs should be conducted to provide an empirical base for the decisions being made.

Compare the effects of program variations on short-term and long-term outcomes, including studies of inclusion of children with disabilities and auspices of program regulation.

Examine preschool administration at local, county, and state levels to assess the relative quality of the administrative and support systems now in place.

Consider quality, infrastructure, and cost-effectiveness.

Review the evidence that should inform state standards and licensing, including limits on group size and square footage requirements.

Develop instruments and strategies to monitor the achievement of young children that meet state and national accountability requirements, respect young children’s unique learning and developmental needs, and do not interfere with teachers’ instructional decision making.

At a time when the importance of education to individual fulfillment and economic success has focused attention on the need to better prepare children for academic achievement, the research literature suggests ways to make gains toward that end. Parents are relying on child care and preschool programs in ever larger numbers. We know that the quality of the programs in which they leave their children matters. If there is a single critical component to quality, it rests in the relationship between the child and the teacher/caregiver, and in the ability of the adult to be responsive to the child. But responsiveness extends in many directions: to the child’s cognitive, social, emotional, and physical characteristics and development.

Much research still needs to be done. But from the committee’s perspective, the case for a substantial investment in a high-quality system of child care and preschool on the basis of what is already known is persuasive. Moreover, the considerable lead by other developed countries in the provision of quality preschool programs suggests that it can, indeed, be done on a large scale.

Clearly babies come into the world remarkably receptive to its wonders. Their alertness to sights, sounds, and even abstract concepts makes them inquisitive explorers—and learners—every waking minute. Well before formal schooling begins, children's early experiences lay the foundations for their later social behavior, emotional regulation, and literacy. Yet, for a variety of reasons, far too little attention is given to the quality of these crucial years. Outmoded theories, outdated facts, and undersized budgets all play a part in the uneven quality of early childhood programs throughout our country.

What will it take to provide better early education and care for our children between the ages of two and five? Eager to Learn explores this crucial question, synthesizing the newest research findings on how young children learn and the impact of early learning. Key discoveries in how young children learn are reviewed in language accessible to parents as well as educators: findings about the interplay of biology and environment, variations in learning among individuals and children from different social and economic groups, and the importance of health, safety, nutrition and interpersonal warmth to early learning. Perhaps most significant, the book documents how very early in life learning really begins. Valuable conclusions and recommendations are presented in the areas of the teacher-child relationship, the organization and content of curriculum, meeting the needs of those children most at risk of school failure, teacher preparation, assessment of teaching and learning, and more. The book discusses:

- Evidence for competing theories, models, and approaches in the field and a hard look at some day-to-day practices and activities generally used in preschool.

- The role of the teacher, the importance of peer interactions, and other relationships in the child's life.

- Learning needs of minority children, children with disabilities, and other special groups.

- Approaches to assessing young children's learning for the purposes of policy decisions, diagnosis of educational difficulties, and instructional planning.

- Preparation and continuing development of teachers.

Eager to Learn presents a comprehensive, coherent picture of early childhood learning, along with a clear path toward improving this important stage of life for all children.

READ FREE ONLINE

Welcome to OpenBook!

You're looking at OpenBook, NAP.edu's online reading room since 1999. Based on feedback from you, our users, we've made some improvements that make it easier than ever to read thousands of publications on our website.

Do you want to take a quick tour of the OpenBook's features?

Show this book's table of contents , where you can jump to any chapter by name.

...or use these buttons to go back to the previous chapter or skip to the next one.

Jump up to the previous page or down to the next one. Also, you can type in a page number and press Enter to go directly to that page in the book.

Switch between the Original Pages , where you can read the report as it appeared in print, and Text Pages for the web version, where you can highlight and search the text.

To search the entire text of this book, type in your search term here and press Enter .

Share a link to this book page on your preferred social network or via email.

View our suggested citation for this chapter.

Ready to take your reading offline? Click here to buy this book in print or download it as a free PDF, if available.

Get Email Updates

Do you enjoy reading reports from the Academies online for free ? Sign up for email notifications and we'll let you know about new publications in your areas of interest when they're released.

Advertisement

Entering Kindergarten After Years of Play: A Cross-Case Analysis of School Readiness Following Play-Based Education

- Open access

- Published: 15 November 2022

- Volume 52 , pages 167–179, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Lisa Fyffe ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4073-2137 1 ,

- Pat L. Sample 1 ,

- Angela Lewis 2 ,

- Karen Rattenborg 3 &

- Anita C. Bundy 1

5240 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Cross-case study research was used to explore the school readiness of four 5-year-old children entering kindergarten during the 2020–2021 school year after three or more years of play-based early childhood education at a Reggio Emilia-inspired early childhood education center. Data included a series of three 1-h individual interviews with four mothers and three kindergarten teachers, field visits during remote learning, and artifact collection over the course of the school year. Themes describing the children’s school readiness were developed through cross-case analysis. Participants described the children as learners, explorers, communicators, and empathizers. The learner theme centers on the children’s responsiveness to instruction; the explorer theme describes how the children approached learning; the communicator theme illustrates the children’s prowess with social connection and self-advocacy, and the empathizer theme shows the thoughtfulness and emotional sensitivity these children displayed. Findings suggest that play-based learning prepared these children for successful kindergarten experiences and was a viable early childhood education pedagogy fostering school readiness.

Similar content being viewed by others

“Could that be Play?”: Exploring Pre-service Teachers’ Perceptions of Play in Kindergarten

Inclusive Play-Based Learning: Approaches from Enacting Kindergarten Teachers

Play in kindergarten: an interview and observational study in three canadian classrooms.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

School readiness is a culmination of a lifetime of experiences that prepare children to enter a group learning context where they must modify their actions in response to feedback, establish relationships with peers and adults, and apply new knowledge within a variety of learning contexts. Thus, children benefit from formal education when they have developed processes that support learning, such as establishing social relationships, self-management, and positive approaches to learning (Eggum-Wilkins et al., 2014 ; Ginsburg, 2007 ; Pistorova & Slutsky, 2018 ).

The National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC, 2017 ) promotes the use of play as an educational pedagogy during early childhood to facilitate the social adaptation, inquisitiveness, and self-regulation necessary for comprehending academic content and general knowledge. NAEYC ( 2017 ) described play in early childhood education as “a valuable pedagogical tool in that it features the precise contexts that facilitate learning… mental activation, engagement, social interaction, and meaningful connections” (p. 3). Play has been considered the foundation of children’s learning dating back to the days of Plato (427–347 BC) and Aristotle (387–322 BC), both of whom wrote about the virtues of play as necessary to develop children into competent adults. Vygotsky ( 1978 ) described that exploring culturally instilled roles through play developed attention, memory, abstract thought, and self-monitoring. Elkonin ( 1978 ) extended this discussion by saying that play fostered children’s mental representation, motivation and intentionality, awareness of multiple perspectives, behavior modification in accordance with social norms, and promotes internal morality as children create, follow, adapt, and enforce rules.

More recently, the American Academy of Pediatrics (Ginsburg, 2007 ) described play as “essential to the cognitive, physical, social and emotional well-being of children and youth” and called for “the inclusion of play as we... prepare our children to be academically, socially, and emotionally equipped to lead us into the future” (p. 183). Zosh et al. ( 2017 ) concurred, stating that “content only serves children as far as they can apply and build on it… children also need a deep conceptual understanding to connect concepts and skills, apply knowledge and spark new ideas” (p. 5). Given that play fosters the social reciprocity, self-management and creative thought processes deemed necessary for school readiness, time spent playing provides essential preparation for learning receptivity and responsiveness.

Consistent with these views, early childhood education programs have been historically grounded in child-directed play experiences with a primary focus on developing social relationships, approaches to learning, and self-regulation (Burchinal et al., 2008 ). Play as the focus of early childhood education remained essentially unchallenged in the United States until 1983, when the National Commission on Excellence in Education issued a report entitled A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Education Reform . This Presidential-commissioned report described education in the United States as “a rising tide of mediocrity” citing American children’s poor academic performance, rampant illiteracy among adults and teens and declining scores on standardized achievement tests measuring academic competency. The authors recommended sweeping educational reforms with higher expectations of student performance and rising academic achievement test scores as the cornerstone of a stronger American education system (National Commission on Excellence in Education, 1983 ). Congress responded by enacting educational reforms, beginning with America First (1991), a comprehensive education reform act aimed at improving school readiness.

America First defined school readiness along five domains: physical health and wellbeing, social-emotional development, language development, general knowledge and cognition, and approaches to learning. Most states evaluated school readiness by measuring general knowledge and cognition, placing less focus on the other four domains. Subsequent educational reform legislation, No Child Left Behind (NCLB; 2002) and Race to the Top-Early Learning Challenge (RTTT-ELC; 2013), further cemented administration of standardized assessments prior to kindergarten entry. This represented a substantial shift from formative assessments of early childhood education, where teachers evaluated children over time (Hustedt et al., 2018 ).

As early childhood educators navigated increasing pressures for proficiency in early literacy and numeracy, the content of many early childhood education programs emphasized academic content (Fleer, 2021 ; Nicolopoulou, 2010 ; Taylor & Boyer, 2019 ). However, academic instruction in preschool is controversial; some early childhood educators have expressed concern about the developmental appropriateness of direct instruction practices (NAEYC, 2017 ; Zosh et al., 2017 ). This philosophical split left some early childhood programs grounded in play-based, child-directed experiential learning while others emphasized direct academic instruction. Durkin et al. ( 2022 ) stated that direct instruction in early childhood education produces short-term gains in constrained literacy skills (e.g., recognizing the alphabet), but not the unconstrained literacy and numeracy skills associated with long-term academic success (e.g., comprehension, problem-solving). This suggests that content-heavy preschool curricula most aligned with school readiness assessments may fail to capture the foundational aptitudes children need for academic achievement.

School readiness is a complicated and nuanced concept; children need more than general knowledge and academic skills to thrive at school. Hustedt et al. ( 2018 ) found that kindergarten teachers favored non-academic skills as most valuable: caring for personal needs, exhibiting self-control, communicating needs and preferences, modifying behavior and interacting cooperatively. Pistorova and Stutsky (2018) further argued that the twenty-first century learner must be fluent with “critical thinking, communication, collaboration and creativity” (p. 495); these are learned through capitalizing on children’s natural curiosity and inquisitiveness. Zosh et al. ( 2017 ) stated that optimal learning occurs within a playful context where children experience joyfulness through engagement in meaningful activities. Play-based learning allows children to develop and test theories and make new discoveries, thus expanding their capacity for problem-solving and construction of higher-order conceptual schemas (Fleer, 2021 ; Sim & Xu, 2017 ). Finally, peer play and social relationships have been associated with higher levels of global teacher-rated kindergarten competence including following directions, academic receptivity, self-regulation, and cooperative interactions (Eggum-Wilkins et al., 2014 ).

Johansson and Samuelsson (2006) argued that play and learning in young children are integrated, and researchers must seek to understand the relationship between play and learning rather than dichotomize them with false distinctions. Nilsson et al. ( 2018 ) advocated for a play-as-learning approach to early childhood education, where learning “is not just understood in the narrow cognitive sense…but more broadly as transformations driven by different kinds of experiences that lead to sustained change” (p. 232). This suggests a need for research aimed at explicating the ways in which play contributes to readiness for formal education. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to describe how teachers and parents interpreted the school readiness of four children as they navigated kindergarten after three or more years of play-based early childhood education at a Reggio Emilia-inspired school.

This manuscript is part of a larger, longitudinal study exploring how children fared as kindergarteners following play-based early childhood education, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Occupation and Rehabilitation Science at Colorado State University for first author LF. Data were collected from September 2020 through May 2021. This study was approved through the Colorado State University Institutional Review Board (approval 19-9519H).

Research Design

We used Yin’s ( 2018 ) cross-case study approach to synthesize findings from the cases. We collected data at the onset, midpoint, and conclusion of the kindergarten year. Each data cache informed subsequent data collection.

Participants

We recruited participants from a Reggio Emilia-inspired play-based early childhood center in Northern Colorado. Reggio Emilia is a highly regarded approach to early childhood education where children collaborate with their teachers to explore their interests through projects which are thoughtfully designed and documented (McNally & Slutsky, 2017 ). We enrolled four participant clusters in the summer preceding the child’s kindergarten enrollment; each cluster ideally included a parent and a kindergarten teacher associated with an individual child. Mothers were the parent informant for all four clusters and provided contact information for their child’s kindergarten teacher. Three of four kindergarten teachers participated; one declined due to concerns with the COVID-19 pandemic-affected school year.

Kindergarten teachers represented three different curricular foci: Core Knowledge, International Baccalaureate. and Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM). The research team deemed dissimilar kindergarten foci desirable to offer variation in kindergarten experience, but this was not a participant requirement. Table 1 contains a description of cluster members organized by child.

Pandemic Influence

Public health orders related to the COVID-19 pandemic affected the kindergarten year. Over half of the kindergarten year occurred through remote learning and all in-person school days were affected by public health orders. Requirements of face masks, social distancing, and isolated classroom cohorts limited participation in specials, lunchroom, recess, and group learning experiences. Teacher participants described challenges translating learning activities to remote platforms, altering the scope and sequence of the curriculum, and emotional and behavioral challenges engaging students during in-person learning.

Public health orders also altered data collection as visitors were not allowed in public schools. We adapted to these restrictions by completing home visits during remote learning days, requesting work samples and test scores from participants, and using video conferencing for most interviews.

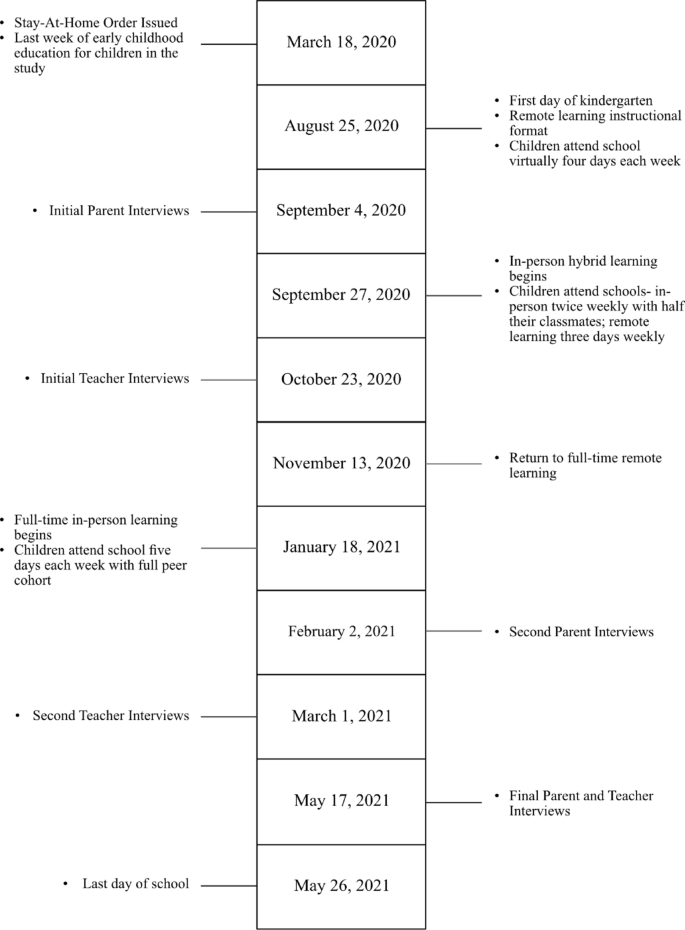

We used semi-structured interviews with participants as the primary data source. Each participant completed three in-depth semi-structured interviews lasting approximately one hour per encounter. The interviews coincided with the start of the school year and planned instructional format shifts. We recorded all interviews; a professional service transcribed them verbatim. See Fig. 1 for an illustration of the timing of interviews alongside of the start and end of the school year and district-wide instructional shifts.

Timeline of public health orders related to COVID-19, district-wide instructional format shifts, and participant interview schedule

We developed separate but parallel interview protocols for the participant groups prior to each interview. Some questions were written for both groups; others were written only for parents or teachers. We wanted to capitalize on each participant’s unique vantage point, while allowing for comparisons of perspectives within and across cases. For example, we asked both parents and teachers about the child’s school readiness based on Colorado’s early learning standards. We asked teachers to describe how the child fit within their classroom expectations and parents to describe how their child had grown over the course of the school year. See Table 2 for interview protocol examples.

In the case of the child whose teacher did not participate (Nadine), we used the same parent interview protocol with her mother as we did with the other parent participants. Nadine’s mother provided work samples and school-generated reports. We blended Nadine’s data within the cross-case analysis as appropriate, acknowledging that we had half the data for her as other participants.

Data Analysis

Congruent with Yin’s ( 2018 ) case-based approach, we analyzed each participant interview upon its conclusion and merged the interviews by case to complete the initial within-case analysis. Once we identified themes from an individual case, we looked for replication across cases, remaining sensitive to congruences and differences as we identified patterns. By comparing patterns across cases, we constructed common themes.

Within-Case Analysis

In the initial phase of analysis, first author LF read each transcript multiple times for familiarity, documented any reactions and biases, and listed all topics emphasized by the participants for each case. In the second phase, these preliminary topics provided an organizational structure for grouping the data into conceptual clusters. In the third phase, authors LF, PS and AB systematically worked through groupings and developed initial codes with extrapolated, verbatim text illustrating the themes under consideration. In the fourth phase, author LF defined and described the themes from the individual cases and selected representative quotes for illustration.

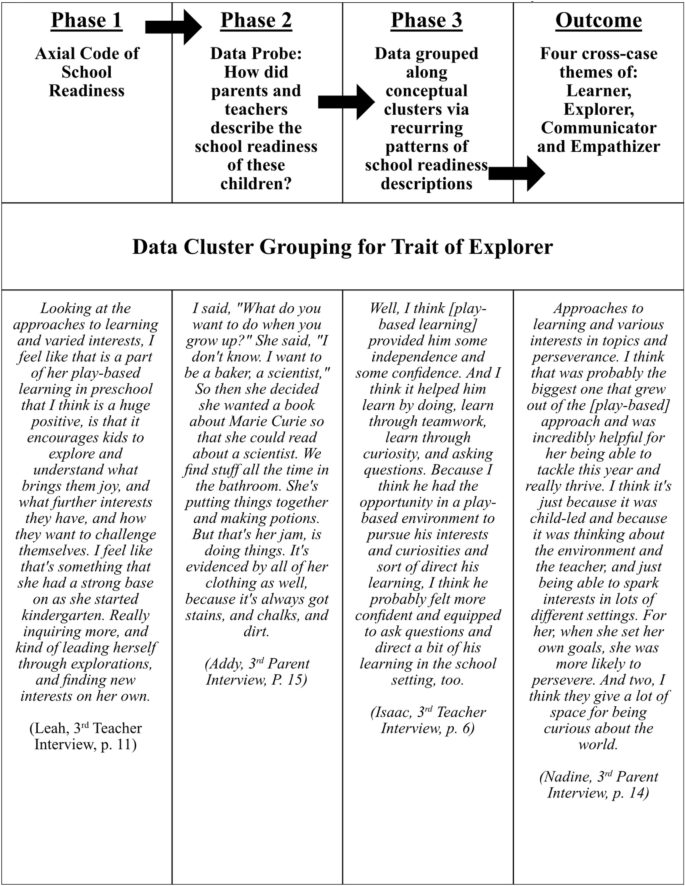

Cross-Case Analysis

Cross-case analysis occurred after individual case analyses. First, author LF reduced the data set to focus on the most significant conceptual clusters; these became axial codes linking the data across cases. For this manuscript, school readiness was the axial code of interest (kindergarten performance and adaptation were the other axial codes and will be the foci of subsequent papers). In the second phase, author LF operationalized school readiness into a probing question ( How are parents and teachers describing the school readiness of these children? ), which guided the cross-case analysis. Finally, authors LF, PS and AB constructed cross-case themes using inductive coding to extrapolate the major descriptors of school readiness common to all cases. First author LF served as the primary coder, PS was the second coder and both PS and AB engaged in ongoing conversations with LF to define, clarify, and construct the final themes. These themes were then presented to the entire research team for discussion until consensus was reached. See Fig. 2 for a graphic illustrating this process.

Explorer theme construction: within-case analysis to cross-case analysis

Quality Assurance

We took many steps to safeguard the quality of the study data, as well as the data analysis. We remained engaged with participants for a full academic year which allowed for data triangulation and opportunities for member checking. We practiced highly disciplined subjectivity through data trail audits, explicit links between interpretation and participant excerpts, and constant comparative analysis within and across cases (Yin, 2018 ). We held recurring meetings to discuss the findings and arrive at consensus with all members of the research team.

Positionality

Author LF supervised occupational therapy students completing internships at the play-based early childhood center where the children were enrolled prior to entering kindergarten. Author PS has expertise in qualitative research methodology but had not worked with early childhood research prior to this study. Author AL is an early childhood education teacher educator and coached teacher candidates at the research site. Author KR was the Executive Director of the center during the time when this study occurred. Author AB is an expert in play and has many years of school-based experience as an occupational therapist and researcher.

Participants believed the children were well prepared for kindergarten. Four themes were identified through the data analysis process that illustrate their school readiness: learners, explorers, communicators, and empathizers . See Table 3 for full definitions of each theme.

Theme 1: Learners

We defined learner as a child who is highly receptive to acquiring new knowledge. Data within this theme described children’s responses to classroom instruction and teacher feedback. Teachers reported that the children arrived at kindergarten ready to learn and were quick to integrate new knowledge and concepts. They noted well-developed language, eagerness for learning, and willingness to embrace feedback and challenge. Isaac’s teacher described him by stating.

What I could tell is that he was ready to learn. He was really engaged with letters and numbers, and he was eager. It was the perfect time to start teaching him how to read and write… (Isaac, 3rd Teacher Interview, p. 13)

Addy’s teacher described her by saying.