Suggestions or feedback?

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Machine learning

- Social justice

- Black holes

- Classes and programs

Departments

- Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Architecture

- Political Science

- Mechanical Engineering

Centers, Labs, & Programs

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

- Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Lincoln Laboratory

- School of Architecture + Planning

- School of Engineering

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

- Sloan School of Management

- School of Science

- MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

What 126 studies say about education technology

Press contact :.

Previous image Next image

In recent years, there has been widespread excitement around the transformative potential of technology in education. In the United States alone, spending on education technology has now exceeded $13 billion . Programs and policies to promote the use of education technology may expand access to quality education, support students’ learning in innovative ways, and help families navigate complex school systems.

However, the rapid development of education technology in the United States is occurring in a context of deep and persistent inequality . Depending on how programs are designed, how they are used, and who can access them, education technologies could alleviate or aggravate existing disparities. To harness education technology’s full potential, education decision-makers, product developers, and funders need to understand the ways in which technology can help — or in some cases hurt — student learning.

To address this need, J-PAL North America recently released a new publication summarizing 126 rigorous evaluations of different uses of education technology. Drawing primarily from research in developed countries, the publication looks at randomized evaluations and regression discontinuity designs across four broad categories: (1) access to technology, (2) computer-assisted learning or educational software, (3) technology-enabled nudges in education, and (4) online learning.

This growing body of evidence suggests some areas of promise and points to four key lessons on education technology.

First, supplying computers and internet alone generally do not improve students’ academic outcomes from kindergarten to 12th grade, but do increase computer usage and improve computer proficiency. Disparities in access to information and communication technologies can exacerbate existing educational inequalities. Students without access at school or at home may struggle to complete web-based assignments and may have a hard time developing digital literacy skills.

Broadly, programs to expand access to technology have been effective at increasing use of computers and improving computer skills. However, computer distribution and internet subsidy programs generally did not improve grades and test scores and in some cases led to adverse impacts on academic achievement. The limited rigorous evidence suggests that distributing computers may have a more direct impact on learning outcomes at the postsecondary level.

Second, educational software (often called “computer-assisted learning”) programs designed to help students develop particular skills have shown enormous promise in improving learning outcomes, particularly in math. Targeting instruction to meet students’ learning levels has been found to be effective in improving student learning, but large class sizes with a wide range of learning levels can make it hard for teachers to personalize instruction. Software has the potential to overcome traditional classroom constraints by customizing activities for each student. Educational software programs range from light-touch homework support tools to more intensive interventions that re-orient the classroom around the use of software.

Most educational software that have been rigorously evaluated help students practice particular skills through personalized tutoring approaches. Computer-assisted learning programs have shown enormous promise in improving academic achievement, especially in math. Of all 30 studies of computer-assisted learning programs, 20 reported statistically significant positive effects, 15 of which were focused on improving math outcomes.

Third, technology-based nudges — such as text message reminders — can have meaningful, if modest, impacts on a variety of education-related outcomes, often at extremely low costs. Low-cost interventions like text message reminders can successfully support students and families at each stage of schooling. Text messages with reminders, tips, goal-setting tools, and encouragement can increase parental engagement in learning activities, such as reading with their elementary-aged children.

Middle and high schools, meanwhile, can help parents support their children by providing families with information about how well their children are doing in school. Colleges can increase application and enrollment rates by leveraging technology to suggest specific action items, streamline financial aid procedures, and/or provide personalized support to high school students.

Online courses are developing a growing presence in education, but the limited experimental evidence suggests that online-only courses lower student academic achievement compared to in-person courses. In four of six studies that directly compared the impact of taking a course online versus in-person only, student performance was lower in the online courses. However, students performed similarly in courses with both in-person and online components compared to traditional face-to-face classes.

The new publication is meant to be a resource for decision-makers interested in learning which uses of education technology go beyond the hype to truly help students learn. At the same time, the publication outlines key open questions about the impacts of education technology, including questions relating to the long-term impacts of education technology and the impacts of education technology on different types of learners.

To help answer these questions, J-PAL North America’s Education, Technology, and Opportunity Initiative is working to build the evidence base on promising uses of education technology by partnering directly with education leaders.

Education leaders are invited to submit letters of interest to partner with J-PAL North America through its Innovation Competition . Anyone interested in learning more about how to apply is encouraged to contact initiative manager Vincent Quan .

Share this news article on:

Related links.

- J-PAL Education, Technology, and Opportunity Initiative

- Education, Technology, and Opportunity Innovation Competition

- Article: "Will Technology Transform Education for the Better?"

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab

- Department of Economics

Related Topics

- School of Humanities Arts and Social Sciences

- Education, teaching, academics

- Technology and society

- Computer science and technology

Related Articles

J-PAL North America calls for proposals from education leaders

J-PAL North America’s Education, Technology, and Opportunity Innovation Competition announces inaugural partners

New learning opportunities for displaced persons

J-PAL North America announces new partnerships with three state and local governments

A new way to measure women’s and girls’ empowerment in impact evaluations

Previous item Next item

More MIT News

Nuh Gedik receives 2024 National Brown Investigator Award

Read full story →

Reducing carbon emissions from long-haul trucks

Mouth-based touchpad enables people living with paralysis to interact with computers

Advocating for science funding on Capitol Hill

Unique professional development course prepares students for future careers

New technique reveals how gene transcription is coordinated in cells

- More news on MIT News homepage →

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA, USA

- Map (opens in new window)

- Events (opens in new window)

- People (opens in new window)

- Careers (opens in new window)

- Accessibility

- Social Media Hub

- MIT on Facebook

- MIT on YouTube

- MIT on Instagram

Education Technology: What Is Edtech? A Guide.

Edtech, or education technology, is the combination of IT tools and educational practices aimed at facilitating and enhancing learning.

What Is Edtech?

Edtech, or education technology, is the practice of introducing information and communication technology tools into the classroom to create more engaging, inclusive and individualized learning experiences.

Today’s classrooms have moved beyond the clunky desktop computers that were once the norm and are now tech-infused with tablets, interactive online courses and even robots that can take notes and record lectures for absent students.

The influx of edtech tools are changing classrooms in a variety of ways. For instance, edtech robots , virtual reality lessons and gamified classroom activities make it easier for students to stay engaged through fun forms of learning. And edtech IoT devices are hailed for their ability to create digital classrooms for students, whether they’re physically in school, on the bus or at home. Even machine learning and blockchain tools are assisting teachers with grading tests and holding students accountable for homework.

The potential for scalable individualized learning has played an important role in the edtech industry’s ascendance . The way we learn, how we interact with classmates and teachers, and our overall enthusiasm for the same subjects is not a one-size-fits-all situation. Everyone learns at their own pace and in their own style. Edtech tools make it easier for teachers to create individualized lesson plans and learning experiences that foster a sense of inclusivity and boost the learning capabilities of all students, no matter their age or learning abilities.

And it looks like technology in the classroom is here to stay. In a 2018 study , 86 percent of eighth-grade teachers agreed that using technology to teach students is important. And 75 percent of the study’s teachers said technology use improved the academic performance of students. For that reason, many would argue it’s vital to understand the benefits edtech brings in the form of increased communication, collaboration and overall quality of education.

Related Reading 13 Edtech Examples You Should Know

How Does Edtech Help Students and Teachers?

Benefits of edtech for students.

An influx of technology is opening up new avenues of learning for students of all ages, while also promoting collaboration and inclusivity in the classroom. Here are five major ways edtech is directly impacting the way students learn.

Increased Collaboration

Cloud-enabled tools and tablets are fostering collaboration in the classroom. Tablets loaded with learning games and online lessons give children the tools to solve problems together. Meanwhile, cloud-based apps let students upload their homework and digitally converse with one another about their thought processes and for any help they may need.

24/7 Access to Learning

IoT devices are making it easier for students to have full access to the classroom in a digital environment. Whether they’re at school, on the bus or at home, connected devices are giving students Wi-Fi and cloud access to complete work at their own pace — and on their own schedules — without being hampered by the restriction of needing to be present in a physical classroom.

Various apps also help students and teachers stay in communication in case students have questions or need to alert teachers to an emergency.

“Flipping” the Classroom

Edtech tools are flipping the traditional notion of classrooms and education. Traditionally, students have to listen to lectures or read in class then work on projects and homework at home. With video lectures and learning apps, students can now watch lessons at home at their own pace, using class time to collaboratively work on projects as a group. This type of learning style helps foster self-learning, creativity and a sense of collaboration among students.

Personalized Educational Experiences

Edtech opens up opportunities for educators to craft personalized learning plans for each of their students. This approach aims to customize learning based on a student’s strengths, skills and interests.

Video content tools help students learn at their own pace and because students can pause and rewind lectures, these videos can help students fully grasp lessons. With analytics, teachers can see which students had trouble with certain lessons and offer further help on the subject.

Instead of relying on stress-inducing testing to measure academic success, educators are now turning to apps that consistently measure overall aptitude . Constant measurements display learning trends that teachers can use to craft specialized learning plans based on each student’s strengths and weaknesses or, more importantly, find negative trends that can be proactively thwarted with intervention.

Attention-Grabbing Lessons

Do you remember sitting in class, half-listening, half-day dreaming? Now, with a seemingly infinite number of gadgets and outside influences vying for a student’s attention, it’s imperative to craft lesson plans that are both gripping and educational. Edtech proponents say technology is the answer. Some of the more innovative examples of students using tech to boost classroom participation include interacting with other classrooms around the world via video, having students submit homework assignments as videos or podcasts and even gamifying problem-solving .

Benefits of Edtech

- Personalized education caters to different learning styles.

- On-demand video lectures allow classroom time to focus on collaboration.

- Gamified lessons engage students more deeply.

- Cloud computing with 24/7 access lets students work from anywhere.

- Automated grading and classroom management tools help teachers balance responsibilities.

Benefits of Edtech for Teachers

Students aren’t the only group benefitting from edtech. Teachers are seeing educational tech as a means to develop efficient learning practices and save time in the classroom. Here are four ways edtech is helping teachers get back to doing what they do — teaching.

Automated Grading

Artificially intelligent edtech tools are making grading a breeze. These apps use machine learning to analyze and assess answers based on the specifications of the assignment. Using these tools, especially for objective assignments like true/false or fill-in-the-blank assessments, frees up hours that teachers usually spend grading assignments. Extra free time for teachers provides more flexibility for less prep and one-on-one time with both struggling and gifted students.

Classroom Management Tools

Let’s face it, trying to get a large group of kids to do anything can be challenging. Educational technology has the potential to make everything — from the way teachers communicate with their students to how students behave — a little easier. There are now apps that help send parents and students reminders about projects or homework assignments, as well as tools that allow students to self-monitor classroom noise levels. The addition of management tools in the classroom brings forth a less-chaotic, more collaborative environment.

Read Next Assistive Technology in the Classroom Is Reimagining the Future of Education

Paperless Classrooms

Printing budgets, wasting paper and countless time spent at the copy machine are a thing of the past thanks to edtech. Classrooms that have gone digital bring about an easier way to grade assignments, lessen the burden of having to safeguard hundreds of homework files and promote overall greener policies in the classroom.

Eliminating Guesswork

Teachers spend countless hours attempting to assess the skills or areas of improvement of their students. Edtech can change all of that. There are currently myriad tools, data platforms and apps that constantly assess student’s skills and needs, and they relay the data to the teacher.

Sometimes harmful studying trends aren’t apparent to teachers for months, but some tools that use real-time data can help teachers discover a student’s strengths, weaknesses and even signs of learning disabilities, setting in motion a proactive plan to help.

66 Edtech Companies Changing the Way We Learn

The growing edtech industry creates adaptive interfaces, classroom engagement boosters, education-specific fundraising sites, and more.

Need to Boost Your Math Skills? Try Gaming.

Can ai help people overcome dyslexia.

Is Your Interview Technique Stuck in a Rut?

What Role Should AI Play in College Admissions?

Is an MBA Worth It?

19 Online Learning Platforms Transforming Education

16 Machine Learning in Education Examples

What Are Children Learning When They Learn to Code?

Press Tab to Accept: How AI Redefines Authorship

What I Learned From Pushing Redis Cluster to Its Limits

4 online learning platforms to pique your curiousity.

Continuous learning is essential to success in the tech economy. Fortunately, it’s never been easier to make gaining new skills fit into you

7 Ways Tech Is Changing for the Better in 2020

Great companies need great people. that's where we come in..

Is technology good or bad for learning?

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, saro mohammed, ph.d. smp saro mohammed, ph.d. partner - the learning accelerator @edresearchworks.

May 8, 2019

I’ll bet you’ve read something about technology and learning recently. You may have read that device use enhances learning outcomes . Or perhaps you’ve read that screen time is not good for kids . Maybe you’ve read that there’s no link between adolescents’ screen time and their well-being . Or that college students’ learning declines the more devices are present in their classrooms .

If ever there were a case to be made that more research can cloud rather than clarify an issue, technology use and learning seems to fit the bill. This piece covers what the research actually says, some outstanding questions, and how to approach the use of technology in learning environments to maximize opportunities for learning and minimize the risk of doing harm to students.

In my recent posts , I have frequently cited the mixed evidence about blended learning, which strategically integrates in-person learning with technology to enable real-time data use, personalized instruction, and mastery-based progression. One thing that this nascent evidence base does show is that technology can be linked to improved learning . When technology is integrated into lessons in ways that are aligned with good in-person teaching pedagogy, learning can be better than without technology.

A 2018 meta-analysis of dozens of rigorous studies of ed tech , along with the executive summary of a forthcoming update (126 rigorous experiments), indicated that when education technology is used to individualize students’ pace of learning, the results overall show “ enormous promise .” In other words, ed tech can improve learning when used to personalize instruction to each student’s pace.

Further, this same meta-analysis, along with other large but correlational studies (e.g., OECD 2015 ), also found that increased access to technology in school was associated with improved proficiency with, and increased use of, technology overall. This is important in light of the fact that access to technology outside of learning environments is still very unevenly distributed across ethnic, socio-economic, and geographic lines. Technology for learning, when deployed to all students, ensures that no student experiences a “21st-century skills and opportunity” gap.

More practically, technology has been shown to scale and sustain instructional practices that would be too resource-intensive to work in exclusively in-person learning environments, especially those with the highest needs. In multiple , large-scale studies where technology has been incorporated into the learning experiences of hundreds of students across multiple schools and school systems, they have been associated with better academic outcomes than comparable classrooms that did not include technology. Added to these larger bodies of research are dozens, if not hundreds, of smaller , more localized examples of technology being used successfully to improve students’ learning experiences. Further, meta-analyses and syntheses of the research show that blended learning can produce greater learning than exclusively in-person learning.

All of the above suggest that technology, used well, can drive equity in learning opportunities. We are seeing that students and families from privileged backgrounds are able to make choices about technology use that maximize its benefits and minimize its risks , while students and families from marginalized backgrounds do not have opportunities to make the same informed choices. Intentional, thoughtful inclusion of technology in public learning environments can ensure that all students, regardless of their ethnicity, socioeconomic status, language status, special education status, or other characteristics, have the opportunity to experience learning and develop skills that allow them to fully realize their potential.

On the other hand, the evidence is decidedly mixed on the neurological impact of technology use. In November 2016, the American Association of Pediatrics updated their screen time guidelines for parents, generally relaxing restrictions and increasing the recommended maximum amount of time that children in different age groups spend interacting with screens. These guidelines were revised not because of any new research, but for two far more practical reasons. First, the nuance of the existing evidence–especially the ways in which recommendations change as children get older–was not adequately captured in the previous guidelines. Second, the proliferation of technology in our lives had made the previous guidelines almost impossible to follow.

The truth is that infants, in particular, learn by interacting with our physical world and with other humans, and it is likely that very early (passive) interactions with devices–rather than humans–can disrupt or misinform neural development . As we grow older, time spent on devices often replaces time spent engaging in physical activity or socially with other people, and it can even become a substitute for emotional regulation, which is detrimental to physical, social, and emotional development.

In adolescence and young adulthood, the presence of technology in learning environments has also been associated with (but has not been shown to be the cause of) negative variables such as attention deficits or hyperactivity , feeling lonely , and lower grades . Multitasking is not something our brains can do while learning , and technology often represents not just one more “task” to have to attend to in a learning environment, but multiple additional tasks due to the variety of apps and programs installed on and producing notifications through a single device.

The pragmatic

The current takeaway from the research is that there are potential benefits and risks to deploying technology in learning environments. While we can’t wrap this topic up with a bow just yet–there are still more questions than answers–there is evidence that technology can amplify effective teaching and learning when in the hands of good teachers. The best we can do today is understand how technology can be a valuable tool for educators to do the complex, human work that is teaching by capitalizing on the benefits while remaining fully mindful of the risks as we currently understand them.

We must continue to build our understanding of both the risks and benefits as we proceed. With that in mind, here are some “Dos” and “Don’ts” for using technology in learning environments:

Related Content

Saro Mohammed, Ph.D.

November 3, 2017

June 16, 2017

September 27, 2017

Education Technology K-12 Education

Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy

Jing Liu, Cameron Conrad, David Blazar

May 1, 2024

Hannah C. Kistler, Shaun M. Dougherty

April 9, 2024

Darrell M. West, Joseph B. Keller

February 12, 2024

New global data reveal education technology’s impact on learning

The promise of technology in the classroom is great: enabling personalized, mastery-based learning; saving teacher time; and equipping students with the digital skills they will need for 21st-century careers. Indeed, controlled pilot studies have shown meaningful improvements in student outcomes through personalized blended learning. 1 John F. Pane et al., “How does personalized learning affect student achievement?,” RAND Corporation, 2017, rand.org. During this time of school shutdowns and remote learning , education technology has become a lifeline for the continuation of learning.

As school systems begin to prepare for a return to the classroom , many are asking whether education technology should play a greater role in student learning beyond the immediate crisis and what that might look like. To help inform the answer to that question, this article analyzes one important data set: the 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), published in December 2019 by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Every three years, the OECD uses PISA to test 15-year-olds around the world on math, reading, and science. What makes these tests so powerful is that they go beyond the numbers, asking students, principals, teachers, and parents a series of questions about their attitudes, behaviors, and resources. An optional student survey on information and communications technology (ICT) asks specifically about technology use—in the classroom, for homework, and more broadly.

In 2018, more than 340,000 students in 51 countries took the ICT survey, providing a rich data set for analyzing key questions about technology use in schools. How much is technology being used in schools? Which technologies are having a positive impact on student outcomes? What is the optimal amount of time to spend using devices in the classroom and for homework? How does this vary across different countries and regions?

From other studies we know that how education technology is used, and how it is embedded in the learning experience, is critical to its effectiveness. This data is focused on extent and intensity of use, not the pedagogical context of each classroom. It cannot therefore answer questions on the eventual potential of education technology—but it can powerfully tell us the extent to which that potential is being realized today in classrooms around the world.

Five key findings from the latest results help answer these questions and suggest potential links between technology and student outcomes:

- The type of device matters—some are associated with worse student outcomes.

- Geography matters—technology is associated with higher student outcomes in the United States than in other regions.

- Who is using the technology matters—technology in the hands of teachers is associated with higher scores than technology in the hands of students.

- Intensity matters—students who use technology intensely or not at all perform better than those with moderate use.

- A school system’s current performance level matters—in lower-performing school systems, technology is associated with worse results.

This analysis covers only one source of data, and it should be interpreted with care alongside other relevant studies. Nonetheless, the 2018 PISA results suggest that systems aiming to improve student outcomes should take a more nuanced and cautious approach to deploying technology once students return to the classroom. It is not enough add devices to the classroom, check the box, and hope for the best.

What can we learn from the latest PISA results?

How will the use, and effectiveness, of technology change post-covid-19.

The PISA assessment was carried out in 2018 and published in December 2019. Since its publication, schools and students globally have been quite suddenly thrust into far greater reliance on technology. Use of online-learning websites and adaptive software has expanded dramatically. Khan Academy has experienced a 250 percent surge in traffic; smaller sites have seen traffic grow fivefold or more. Hundreds of thousands of teachers have been thrown into the deep end, learning to use new platforms, software, and systems. No one is arguing that the rapid cobbling together of remote learning under extreme time pressure represents best-practice use of education technology. Nonetheless, a vast experiment is underway, and innovations often emerge in times of crisis. At this point, it is unclear whether this represents the beginning of a new wave of more widespread and more effective technology use in the classroom or a temporary blip that will fade once students and teachers return to in-person instruction. It is possible that a combination of software improvements, teacher capability building, and student familiarity will fundamentally change the effectiveness of education technology in improving student outcomes. It is also possible that our findings will continue to hold true and technology in the classroom will continue to be a mixed blessing. It is therefore critical that ongoing research efforts track what is working and for whom and, just as important, what is not. These answers will inform the project of reimagining a better education for all students in the aftermath of COVID-19.

PISA data have their limitations. First, these data relate to high-school students, and findings may not be applicable in elementary schools or postsecondary institutions. Second, these are single-point observational data, not longitudinal experimental data, which means that any links between technology and results should be interpreted as correlation rather than causation. Third, the outcomes measured are math, science, and reading test results, so our analysis cannot assess important soft skills and nonacademic outcomes.

It is also worth noting that technology for learning has implications beyond direct student outcomes, both positive and negative. PISA cannot address these broader issues, and neither does this paper.

But PISA results, which we’ve broken down into five key findings, can still provide powerful insights. The assessment strives to measure the understanding and application of ideas, rather than the retention of facts derived from rote memorization, and the broad geographic coverage and sample size help elucidate the reality of what is happening on the ground.

Finding 1: The type of device matters

The evidence suggests that some devices have more impact than others on outcomes (Exhibit 1). Controlling for student socioeconomic status, school type, and location, 2 Specifically, we control for a composite indicator for economic, social, and cultural status (ESCS) derived from questions about general wealth, home possessions, parental education, and parental occupation; for school type “Is your school a public or a private school” (SC013); and for school location (SC001) where the options are a village, hamlet or rural area (fewer than 3,000 people), a small town (3,000 to about 15,000 people), a town (15,000 to about 100,000 people), a city (100,000 to about 1,000,000 people), and a large city (with more than 1,000,000 people). the use of data projectors 3 A projector is any device that projects computer output, slides, or other information onto a screen in the classroom. and internet-connected computers in the classroom is correlated with nearly a grade-level-better performance on the PISA assessment (assuming approximately 40 PISA points to every grade level). 4 Students were specifically asked (IC009), “Are any of these devices available for you to use at school?,” with the choices being “Yes, and I use it,” “Yes, but I don’t use it,” and “No.” We compared the results for students who have access to and use each device with those who do not have access. The full text for each device in our chart was as follows: Data projector, eg, for slide presentations; Internet-connected school computers; Desktop computer; Interactive whiteboard, eg, SmartBoard; Portable laptop or notebook; and Tablet computer, eg, iPad, BlackBerry PlayBook.

On the other hand, students who use laptops and tablets in the classroom have worse results than those who do not. For laptops, the impact of technology varies by subject; students who use laptops score five points lower on the PISA math assessment, but the impact on science and reading scores is not statistically significant. For tablets, the picture is clearer—in every subject, students who use tablets in the classroom perform a half-grade level worse than those who do not.

Some technologies are more neutral. At the global level, there is no statistically significant difference between students who use desktop computers and interactive whiteboards in the classroom and those who do not.

Finding 2: Geography matters

Looking more closely at the reading results, which were the focus of the 2018 assessment, 5 PISA rotates between focusing on reading, science, and math. The 2018 assessment focused on reading. This means that the total testing time was two hours for each student, of which one hour was reading focused. we can see that the relationship between technology and outcomes varies widely by country and region (Exhibit 2). For example, in all regions except the United States (representing North America), 6 The United States is the only country that took the ICT Familiarity Questionnaire survey in North America; thus, we are comparing it as a country with the other regions. students who use laptops in the classroom score between five and 12 PISA points lower than students who do not use laptops. In the United States, students who use laptops score 17 PISA points higher than those who do not. It seems that US students and teachers are doing something different with their laptops than those in other regions. Perhaps this difference is related to learning curves that develop as teachers and students learn how to get the most out of devices. A proxy to assess this learning curve could be penetration—71 percent of US students claim to be using laptops in the classroom, compared with an average of 37 percent globally. 7 The rate of use excludes nulls. The United States measures higher than any other region in laptop use by students in the classroom. US = 71 percent, Asia = 40 percent, EU = 35 percent, Latin America = 31 percent, MENA = 21 percent, Non-EU Europe = 41 percent. We observe a similar pattern with interactive whiteboards in non-EU Europe. In every other region, interactive whiteboards seem to be hurting results, but in non-EU Europe they are associated with a lift of 21 PISA points, a total that represents a half-year of learning. In this case, however, penetration is not significantly higher than in other developed regions.

Finding 3: It matters whether technology is in the hands of teachers or students

The survey asks students whether the teacher, student, or both were using technology. Globally, the best results in reading occur when only the teacher is using the device, with some benefit in science when both teacher and students use digital devices (Exhibit 3). Exclusive use of the device by students is associated with significantly lower outcomes everywhere. The pattern is similar for science and math.

Again, the regional differences are instructive. Looking again at reading, we note that US students are getting significant lift (three-quarters of a year of learning) from either just teachers or teachers and students using devices, while students alone using a device score significantly lower (half a year of learning) than students who do not use devices at all. Exclusive use of devices by the teacher is associated with better outcomes in Europe too, though the size of the effect is smaller.

Finding 4: Intensity of use matters

PISA also asked students about intensity of use—how much time they spend on devices, 8 PISA rotates between focusing on reading, science, and math. The 2018 assessment focused on reading. This means that the total testing time was two hours for each student, of which one hour was reading focused. both in the classroom and for homework. The results are stark: students who either shun technology altogether or use it intensely are doing better, with those in the middle flailing (Exhibit 4).

The regional data show a dramatic picture. In the classroom, the optimal amount of time to spend on devices is either “none at all” or “greater than 60 minutes” per subject per week in every region and every subject (this is the amount of time associated with the highest student outcomes, controlling for student socioeconomic status, school type, and location). In no region is a moderate amount of time (1–30 minutes or 31–60 minutes) associated with higher student outcomes. There are important differences across subjects and regions. In math, the optimal amount of time is “none at all” in every region. 9 The United States is the only country that took the ICT Familiarity Questionnaire survey in North America; thus, we are comparing it as a country with the other regions. In reading and science, however, the optimal amount of time is greater than 60 minutes for some regions: Asia and the United States for reading, and the United States and non-EU Europe for science.

The pattern for using devices for homework is slightly less clear cut. Students in Asia, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), and non-EU Europe score highest when they spend “no time at all” on devices for their homework, while students spending a moderate amount of time (1–60 minutes) score best in Latin America and the European Union. Finally, students in the United States who spend greater than 60 minutes are getting the best outcomes.

One interpretation of these data is that students need to get a certain familiarity with technology before they can really start using it to learn. Think of typing an essay, for example. When students who mostly write by hand set out to type an essay, their attention will be focused on the typing rather than the essay content. A competent touch typist, however, will get significant productivity gains by typing rather than handwriting.

Would you like to learn more about our Social Sector Practice ?

Finding 5: the school systems’ overall performance level matters.

Diving deeper into the reading outcomes, which were the focus of the 2018 assessment, we can see the magnitude of the impact of device use in the classroom. In Asia, Latin America, and Europe, students who spend any time on devices in their literacy and language arts classrooms perform about a half-grade level below those who spend none at all. In MENA, they perform more than a full grade level lower. In the United States, by contrast, more than an hour of device use in the classroom is associated with a lift of 17 PISA points, almost a half-year of learning improvement (Exhibit 5).

At the country level, we see that those who are on what we would call the “poor-to-fair” stage of the school-system journey 10 Michael Barber, Chinezi Chijoke, and Mona Mourshed, “ How the world’s most improved school systems keep getting better ,” November 2010. have the worst relationships between technology use and outcomes. For every poor-to-fair system taking the survey, the amount of time on devices in the classroom associated with the highest student scores is zero minutes. Good and great systems are much more mixed. Students in some very highly performing systems (for example, Estonia and Chinese Taipei) perform highest with no device use, but students in other systems (for example, Japan, the United States, and Australia) are getting the best scores with over an hour of use per week in their literacy and language arts classrooms (Exhibit 6). These data suggest that multiple approaches are effective for good-to-great systems, but poor-to-fair systems—which are not well equipped to use devices in the classroom—may need to rethink whether technology is the best use of their resources.

What are the implications for students, teachers, and systems?

Looking across all these results, we can say that the relationship between technology and outcomes in classrooms today is mixed, with variation by device, how that device is used, and geography. Our data do not permit us to draw strong causal conclusions, but this section offers a few hypotheses, informed by existing literature and our own work with school systems, that could explain these results.

First, technology must be used correctly to be effective. Our experience in the field has taught us that it is not enough to “add technology” as if it were the missing, magic ingredient. The use of tech must start with learning goals, and software selection must be based on and integrated with the curriculum. Teachers need support to adapt lesson plans to optimize the use of technology, and teachers should be using the technology themselves or in partnership with students, rather than leaving students alone with devices. These lessons hold true regardless of geography. Another ICT survey question asked principals about schools’ capacity using digital devices. Globally, students performed better in schools where there were sufficient numbers of devices connected to fast internet service; where they had adequate software and online support platforms; and where teachers had the skills, professional development, and time to integrate digital devices in instruction. This was true even accounting for student socioeconomic status, school type, and location.

COVID-19 and student learning in the United States: The hurt could last a lifetime

Second, technology must be matched to the instructional environment and context. One of the most striking findings in the latest PISA assessment is the extent to which technology has had a different impact on student outcomes in different geographies. This corroborates the findings of our 2010 report, How the world’s most improved school systems keep getting better . Those findings demonstrated that different sets of interventions were needed at different stages of the school-system reform journey, from poor-to-fair to good-to-great to excellent. In poor-to-fair systems, limited resources and teacher capabilities as well as poor infrastructure and internet bandwidth are likely to limit the benefits of student-based technology. Our previous work suggests that more prescriptive, teacher-based approaches and technologies (notably data projectors) are more likely to be effective in this context. For example, social enterprise Bridge International Academies equips teachers across several African countries with scripted lesson plans using e-readers. In general, these systems would likely be better off investing in teacher coaching than in a laptop per child. For administrators in good-to-great systems, the decision is harder, as technology has quite different impacts across different high-performing systems.

Third, technology involves a learning curve at both the system and student levels. It is no accident that the systems in which the use of education technology is more mature are getting more positive impact from tech in the classroom. The United States stands out as the country with the most mature set of education-technology products, and its scale enables companies to create software that is integrated with curricula. 11 Common Core State Standards sought to establish consistent educational standards across the United States. While these have not been adopted in all states, they cover enough states to provide continuity and consistency for software and curriculum developers. A similar effect also appears to operate at the student level; those who dabble in tech may be spending their time learning the tech rather than using the tech to learn. This learning curve needs to be built into technology-reform programs.

Taken together, these results suggest that systems that take a comprehensive, data-informed approach may achieve learning gains from thoughtful use of technology in the classroom. The best results come when significant effort is put into ensuring that devices and infrastructure are fit for purpose (fast enough internet service, for example), that software is effective and integrated with curricula, that teachers are trained and given time to rethink lesson plans integrating technology, that students have enough interaction with tech to use it effectively, and that technology strategy is cognizant of the system’s position on the school-system reform journey. Online learning and education technology are currently providing an invaluable service by enabling continued learning over the course of the pandemic; this does not mean that they should be accepted uncritically as students return to the classroom.

Jake Bryant is an associate partner in McKinsey’s Washington, DC, office; Felipe Child is a partner in the Bogotá office; Emma Dorn is the global Education Practice manager in the Silicon Valley office; and Stephen Hall is an associate partner in the Dubai office.

The authors wish to thank Fernanda Alcala, Sujatha Duraikkannan, and Samuel Huang for their contributions to this article.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Safely back to school after coronavirus closures

How the world’s most improved school systems keep getting better

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

What we know about online learning and the homework gap amid the pandemic

America’s K-12 students are returning to classrooms this fall after 18 months of virtual learning at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Some students who lacked the home internet connectivity needed to finish schoolwork during this time – an experience often called the “ homework gap ” – may continue to feel the effects this school year.

Here is what Pew Research Center surveys found about the students most likely to be affected by the homework gap and their experiences learning from home.

Children across the United States are returning to physical classrooms this fall after 18 months at home, raising questions about how digital disparities at home will affect the existing homework gap between certain groups of students.

Methodology for each Pew Research Center poll can be found at the links in the post.

With the exception of the 2018 survey, everyone who took part in the surveys is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

The 2018 data on U.S. teens comes from a Center poll of 743 U.S. teens ages 13 to 17 conducted March 7 to April 10, 2018, using the NORC AmeriSpeak panel. AmeriSpeak is a nationally representative, probability-based panel of the U.S. household population. Randomly selected U.S. households are sampled with a known, nonzero probability of selection from the NORC National Frame, and then contacted by U.S. mail, telephone or face-to-face interviewers. Read more details about the NORC AmeriSpeak panel methodology .

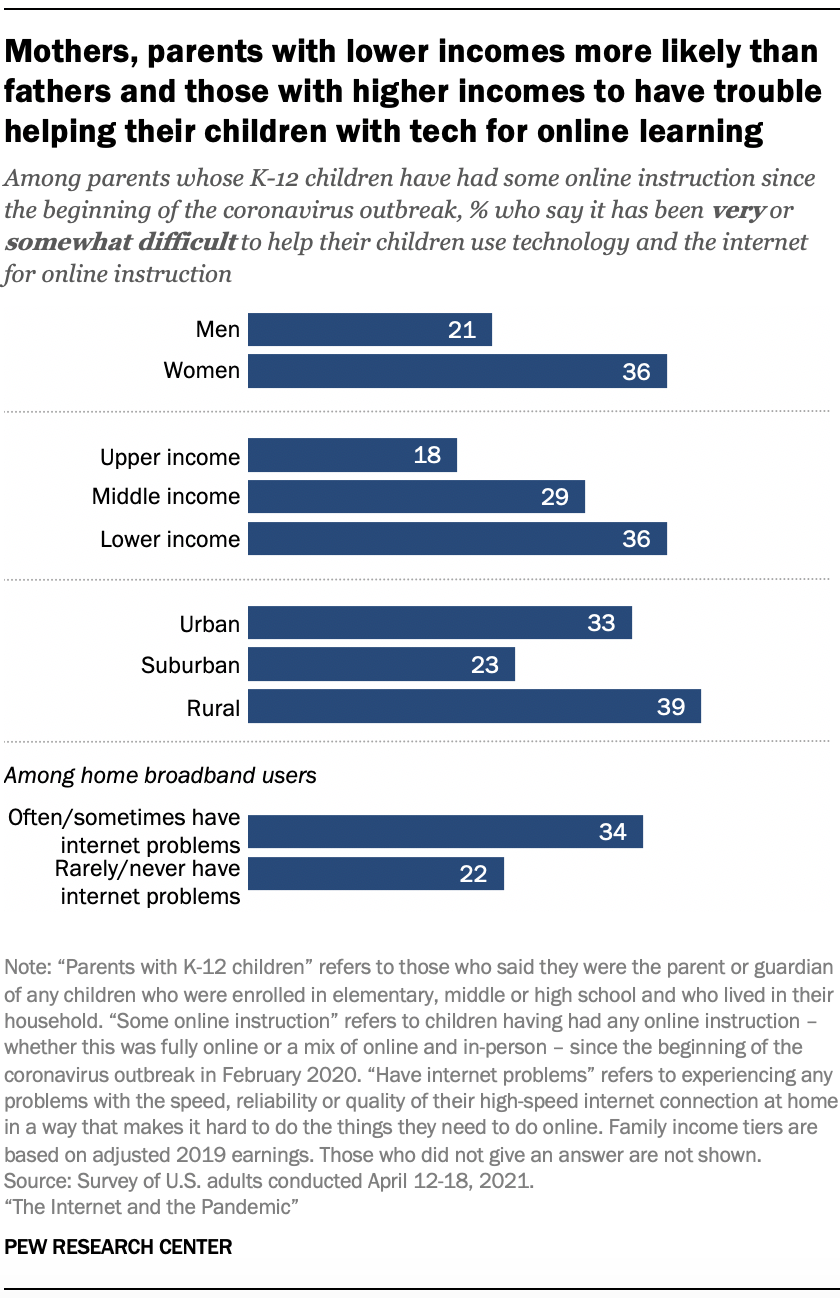

Around nine-in-ten U.S. parents with K-12 children at home (93%) said their children have had some online instruction since the coronavirus outbreak began in February 2020, and 30% of these parents said it has been very or somewhat difficult for them to help their children use technology or the internet as an educational tool, according to an April 2021 Pew Research Center survey .

Gaps existed for certain groups of parents. For example, parents with lower and middle incomes (36% and 29%, respectively) were more likely to report that this was very or somewhat difficult, compared with just 18% of parents with higher incomes.

This challenge was also prevalent for parents in certain types of communities – 39% of rural residents and 33% of urban residents said they have had at least some difficulty, compared with 23% of suburban residents.

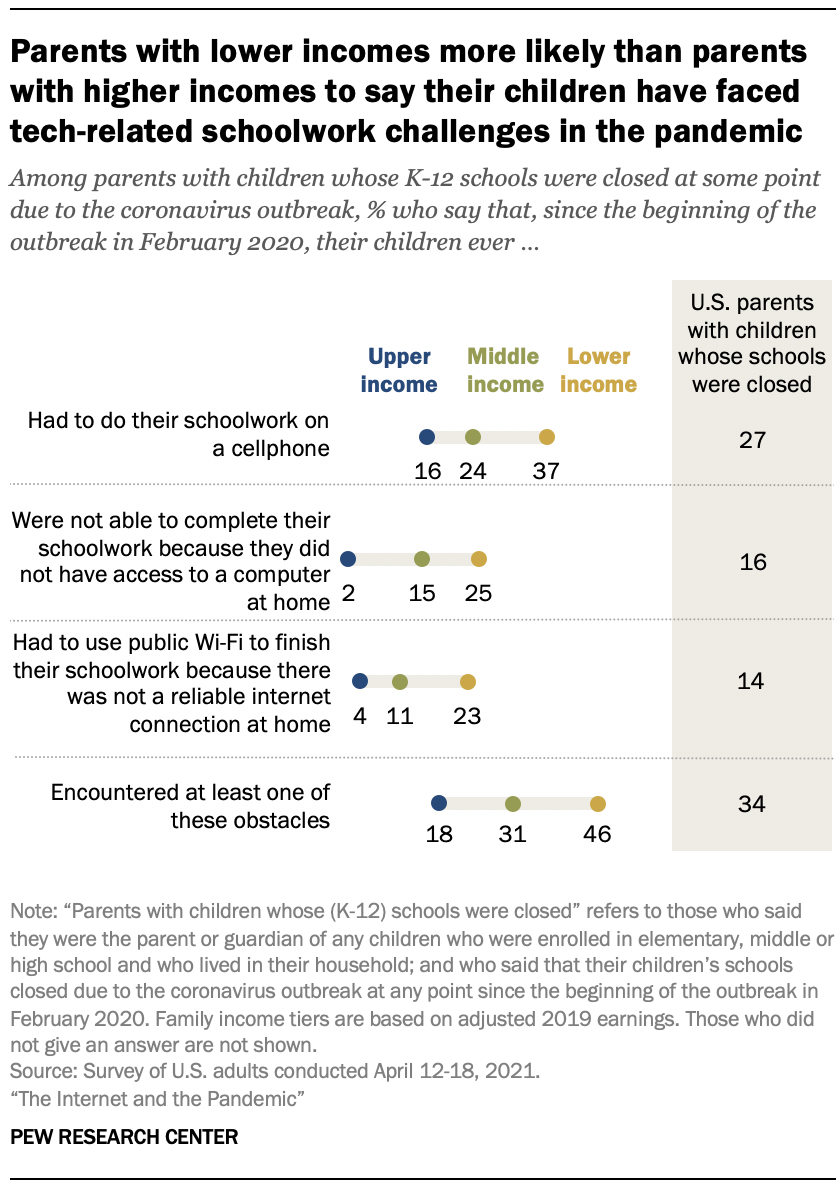

Around a third of parents with children whose schools were closed during the pandemic (34%) said that their child encountered at least one technology-related obstacle to completing their schoolwork during that time. In the April 2021 survey, the Center asked parents of K-12 children whose schools had closed at some point about whether their children had faced three technology-related obstacles. Around a quarter of parents (27%) said their children had to do schoolwork on a cellphone, 16% said their child was unable to complete schoolwork because of a lack of computer access at home, and another 14% said their child had to use public Wi-Fi to finish schoolwork because there was no reliable connection at home.

Parents with lower incomes whose children’s schools closed amid COVID-19 were more likely to say their children faced technology-related obstacles while learning from home. Nearly half of these parents (46%) said their child faced at least one of the three obstacles to learning asked about in the survey, compared with 31% of parents with midrange incomes and 18% of parents with higher incomes.

Of the three obstacles asked about in the survey, parents with lower incomes were most likely to say that their child had to do their schoolwork on a cellphone (37%). About a quarter said their child was unable to complete their schoolwork because they did not have computer access at home (25%), or that they had to use public Wi-Fi because they did not have a reliable internet connection at home (23%).

A Center survey conducted in April 2020 found that, at that time, 59% of parents with lower incomes who had children engaged in remote learning said their children would likely face at least one of the obstacles asked about in the 2021 survey.

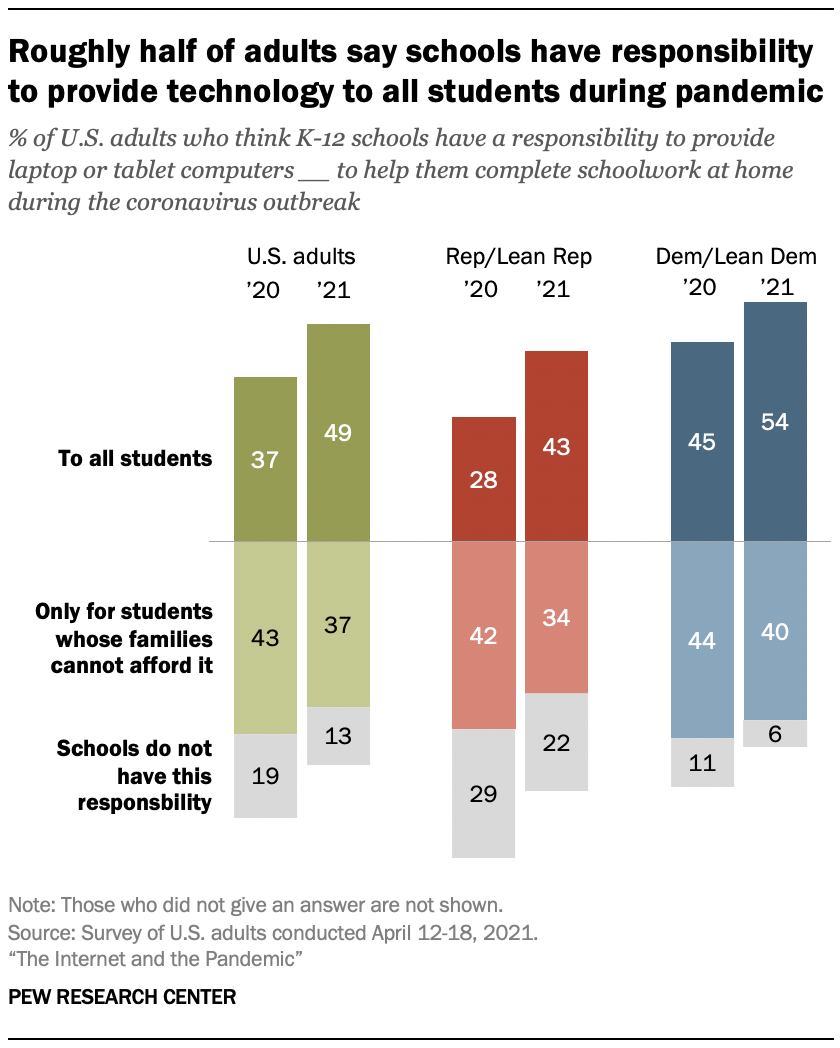

A year into the outbreak, an increasing share of U.S. adults said that K-12 schools have a responsibility to provide all students with laptop or tablet computers in order to help them complete their schoolwork at home during the pandemic. About half of all adults (49%) said this in the spring 2021 survey, up 12 percentage points from a year earlier. An additional 37% of adults said that schools should provide these resources only to students whose families cannot afford them, and just 13% said schools do not have this responsibility.

While larger shares of both political parties in April 2021 said K-12 schools have a responsibility to provide computers to all students in order to help them complete schoolwork at home, there was a 15-point change among Republicans: 43% of Republicans and those who lean to the Republican Party said K-12 schools have this responsibility, compared with 28% last April. In the 2021 survey, 22% of Republicans also said schools do not have this responsibility at all, compared with 6% of Democrats and Democratic leaners.

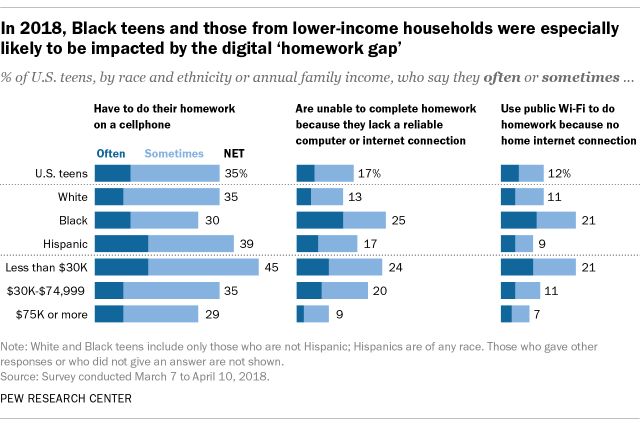

Even before the pandemic, Black teens and those living in lower-income households were more likely than other groups to report trouble completing homework assignments because they did not have reliable technology access. Nearly one-in-five teens ages 13 to 17 (17%) said they are often or sometimes unable to complete homework assignments because they do not have reliable access to a computer or internet connection, a 2018 Center survey of U.S. teens found.

One-quarter of Black teens said they were at least sometimes unable to complete their homework due to a lack of digital access, including 13% who said this happened to them often. Just 4% of White teens and 6% of Hispanic teens said this often happened to them. (There were not enough Asian respondents in the survey sample to be broken out into a separate analysis.)

A wide gap also existed by income level: 24% of teens whose annual family income was less than $30,000 said the lack of a dependable computer or internet connection often or sometimes prohibited them from finishing their homework, but that share dropped to 9% among teens who lived in households earning $75,000 or more a year.

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- COVID-19 & Technology

- Digital Divide

- Education & Learning Online

Katherine Schaeffer is a research analyst at Pew Research Center .

How Americans View the Coronavirus, COVID-19 Vaccines Amid Declining Levels of Concern

Online religious services appeal to many americans, but going in person remains more popular, about a third of u.s. workers who can work from home now do so all the time, how the pandemic has affected attendance at u.s. religious services, mental health and the pandemic: what u.s. surveys have found, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

Digital homework tools should be more than just the textbook as an app

Academic and Lecturer , CQUniversity Australia

Senior Lecturer in Educational Technology, CQUniversity Australia

Assistant researcher, CQUniversity Australia

Disclosure statement

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

CQUniversity Australia provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Schools are increasingly incorporating digital technologies into their teaching practice, raising questions about whether these technologies actually enhance the learning process.

We’re particularly interested the role of technology in homework. Is homework – particularly in digitally aligned STEM areas such as mathematics – any different on a digital device? And, if not, should it be?

We have found that the range of educational websites and apps currently available fail to capitalise on the unique opportunities of digital technology. Working together, technologists and educators could design tools for digital homework that are interactive, instructive, and allow teachers to monitor their students’ progress – leading to better learning outcomes for all.

Read more: Technology in the classroom can improve primary mathematics

The (negligible) value of homework

Despite the prevalence of homework in many schools, the research community is still unsure whether homework actually provides a benefit for students . Recent research from CQUniversity indicates that homework for primary school students is of negligible value, and students are better served by spending this time engaged in structured play or improving their reading abilities.

Even for students in high school, the traditional write-and-check style of homework has shown very little benefit for students . After all, if you don’t know how to do a problem, then how is more practice going to help?

But shouldn’t the interactive and intelligent nature of digital devices make mathematics homework more beneficial for students?

More than a practice problem book

We started reviewing different educational sites and apps addressing mathematics and found they fell into three groups:

- traditional tutorials

- minimally digital tutorials

- digitally enhanced tutorials.

The more traditionally designed online maths tutorials, such as Basic Mathematics and Ezy Math Tutoring , provide a decent amount of depth in their instructions, but they lack a proper curriculum, and any sort of video tutorial or feedback mechanism.

The minimally digital tutorials, such as Study Ladder and Mathletics , have a well-designed curriculum, but lack quality tutorial videos and feedback on the work students do.

The digitally enhanced, such as Khan Academy and Maths Online , provide a well-designed curriculum for any age or grade level, comprehensive instructions, videos, and feedback on student work. They still, however, lack any sort of tutorial prompts during the quizzes.

Enhancing the ‘e’ in e-homework

As you can see, even the best mathematics technologies are not really technological at all – apart from the fact that students use them on a computer or a pad. All the different websites or apps aimed at helping student in mathematics are missing the technological components of technology.

The tools are not interactive. Questions do not increase or decrease in difficulty based on the student’s response to the last question. It would be useful if the practice questions students worked on intuitively increased in difficulty based on the success the student has on the previous question.

Read more: Why digital apps can be good gifts for young family members

None of the tools provide instructive cues to remind students of steps and procedures. And they don’t provide cognitive scaffolding when students are struggling, such as instant instructional advice if a student misses a question.

The tools also fail to provide teachers with data collected about the reason for errors. If they did, teachers could create a learning analysis overviews and specialised learning programs for each student they teach.

It’s clear we need better digital design in our education apps, and particularly those used without a teacher present. But how do we do that?

Bringing educators and technologists together

What need to establish a closer connection between the technologists and the educators.

The tech people need help designing the technology, and they need to design more than just the textbook as an app. Educators can help technologists envision what instruction could look like if the digital device had to do the teaching (and not just the practice) – and then build apps and sites that are innovative and interactive.

Read more: Online learning can prepare students for a fast-changing future – wherever they are

Educators also need to learn from the technologists so they can maximise the use of the devices in their classes. Many educators lack training to use the technological devices to their full potential.

Finally, digital technology designers must consult with educational psychology specialists who provide training for teachers.

We need new technology that isn’t just a copy of educational tools that already exist. Only then will we see the benefits of true digital homework.

Head of School, School of Arts & Social Sciences, Monash University Malaysia

Chief Operating Officer (COO)

Clinical Teaching Fellow

Data Manager

Director, Social Policy

Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

Image credit: Claire Scully

New advances in technology are upending education, from the recent debut of new artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots like ChatGPT to the growing accessibility of virtual-reality tools that expand the boundaries of the classroom. For educators, at the heart of it all is the hope that every learner gets an equal chance to develop the skills they need to succeed. But that promise is not without its pitfalls.

“Technology is a game-changer for education – it offers the prospect of universal access to high-quality learning experiences, and it creates fundamentally new ways of teaching,” said Dan Schwartz, dean of Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE), who is also a professor of educational technology at the GSE and faculty director of the Stanford Accelerator for Learning . “But there are a lot of ways we teach that aren’t great, and a big fear with AI in particular is that we just get more efficient at teaching badly. This is a moment to pay attention, to do things differently.”

For K-12 schools, this year also marks the end of the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funding program, which has provided pandemic recovery funds that many districts used to invest in educational software and systems. With these funds running out in September 2024, schools are trying to determine their best use of technology as they face the prospect of diminishing resources.

Here, Schwartz and other Stanford education scholars weigh in on some of the technology trends taking center stage in the classroom this year.

AI in the classroom

In 2023, the big story in technology and education was generative AI, following the introduction of ChatGPT and other chatbots that produce text seemingly written by a human in response to a question or prompt. Educators immediately worried that students would use the chatbot to cheat by trying to pass its writing off as their own. As schools move to adopt policies around students’ use of the tool, many are also beginning to explore potential opportunities – for example, to generate reading assignments or coach students during the writing process.

AI can also help automate tasks like grading and lesson planning, freeing teachers to do the human work that drew them into the profession in the first place, said Victor Lee, an associate professor at the GSE and faculty lead for the AI + Education initiative at the Stanford Accelerator for Learning. “I’m heartened to see some movement toward creating AI tools that make teachers’ lives better – not to replace them, but to give them the time to do the work that only teachers are able to do,” he said. “I hope to see more on that front.”

He also emphasized the need to teach students now to begin questioning and critiquing the development and use of AI. “AI is not going away,” said Lee, who is also director of CRAFT (Classroom-Ready Resources about AI for Teaching), which provides free resources to help teach AI literacy to high school students across subject areas. “We need to teach students how to understand and think critically about this technology.”

Immersive environments

The use of immersive technologies like augmented reality, virtual reality, and mixed reality is also expected to surge in the classroom, especially as new high-profile devices integrating these realities hit the marketplace in 2024.

The educational possibilities now go beyond putting on a headset and experiencing life in a distant location. With new technologies, students can create their own local interactive 360-degree scenarios, using just a cell phone or inexpensive camera and simple online tools.

“This is an area that’s really going to explode over the next couple of years,” said Kristen Pilner Blair, director of research for the Digital Learning initiative at the Stanford Accelerator for Learning, which runs a program exploring the use of virtual field trips to promote learning. “Students can learn about the effects of climate change, say, by virtually experiencing the impact on a particular environment. But they can also become creators, documenting and sharing immersive media that shows the effects where they live.”

Integrating AI into virtual simulations could also soon take the experience to another level, Schwartz said. “If your VR experience brings me to a redwood tree, you could have a window pop up that allows me to ask questions about the tree, and AI can deliver the answers.”

Gamification

Another trend expected to intensify this year is the gamification of learning activities, often featuring dynamic videos with interactive elements to engage and hold students’ attention.

“Gamification is a good motivator, because one key aspect is reward, which is very powerful,” said Schwartz. The downside? Rewards are specific to the activity at hand, which may not extend to learning more generally. “If I get rewarded for doing math in a space-age video game, it doesn’t mean I’m going to be motivated to do math anywhere else.”

Gamification sometimes tries to make “chocolate-covered broccoli,” Schwartz said, by adding art and rewards to make speeded response tasks involving single-answer, factual questions more fun. He hopes to see more creative play patterns that give students points for rethinking an approach or adapting their strategy, rather than only rewarding them for quickly producing a correct response.

Data-gathering and analysis

The growing use of technology in schools is producing massive amounts of data on students’ activities in the classroom and online. “We’re now able to capture moment-to-moment data, every keystroke a kid makes,” said Schwartz – data that can reveal areas of struggle and different learning opportunities, from solving a math problem to approaching a writing assignment.

But outside of research settings, he said, that type of granular data – now owned by tech companies – is more likely used to refine the design of the software than to provide teachers with actionable information.

The promise of personalized learning is being able to generate content aligned with students’ interests and skill levels, and making lessons more accessible for multilingual learners and students with disabilities. Realizing that promise requires that educators can make sense of the data that’s being collected, said Schwartz – and while advances in AI are making it easier to identify patterns and findings, the data also needs to be in a system and form educators can access and analyze for decision-making. Developing a usable infrastructure for that data, Schwartz said, is an important next step.

With the accumulation of student data comes privacy concerns: How is the data being collected? Are there regulations or guidelines around its use in decision-making? What steps are being taken to prevent unauthorized access? In 2023 K-12 schools experienced a rise in cyberattacks, underscoring the need to implement strong systems to safeguard student data.

Technology is “requiring people to check their assumptions about education,” said Schwartz, noting that AI in particular is very efficient at replicating biases and automating the way things have been done in the past, including poor models of instruction. “But it’s also opening up new possibilities for students producing material, and for being able to identify children who are not average so we can customize toward them. It’s an opportunity to think of entirely new ways of teaching – this is the path I hope to see.”

A systematic review of factors influencing students’ behavioral intention to adopt online homework

- Published: 19 September 2023

Cite this article

- Liu Chen ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0005-8361-9718 1 ,

- Su Luan Wong 1 , 2 &

- Shwu Pyng How 1 , 2

329 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

As a format of homework delivery, online homework promises the usage of technology to help students learn better in the modern era. However, evidence has shown that many students are reluctant to adopt online homework for learning. Behavioral intention is acknowledged as a critical factor predicting the adoption of technology among users. Relevant studies targeted specifically on online homework in terms of behavioral intention are scattered till now. Thus, a review of the literature was conducted to identify factors influencing students’ behavioral intention to adopt online homework. Abiding by the inclusion and exclusion criteria with the guide of PRISMA, 25 articles were selected from four databases. In the current study, the included studies’ characteristics were outlined first. Then, based on the UTAUT model, the findings showed that performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions impact students’ behavioral intention to adopt online homework. Other factors, such as content design, functions, attitudes, and so on, are also associated with students’ behavioral intention to adopt online homework. Further studies and limitations are also included in this study.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Adoption of online mathematics learning in Ugandan government universities during the COVID-19 pandemic: pre-service teachers’ behavioural intention and challenges

Modeling the factors that influence schoolteachers’ work engagement and continuance intention when teaching online

Effects of a homework implementation method (MITCA) on self-regulation of learning

Data availability.

Not applicable.

Albelbisi, N. A., & Yusop, F. D. (2018). Secondary school students’ use of and attitudes toward online mathematics homework. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 17 (1), 144–153.

Google Scholar

Alshehri, A. A. (2017). The perception created of online homework by high school students, their teacher and parents in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Education and Practice, 8 (13), 85–100.

Balta, N., Perera-Rodríguez, V., & Hervás-Gómez, C. (2018). Using Socrative as an online homework platform to increase students’ exam scores. Education and Information Technologies, 23 (12), 837–850. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-017-9638-6

Article Google Scholar

Chao, C. M. (2019). Factors determining the behavioral intention to use mobile learning: An application and extension of the UTAUT model. Frontiers in Psychology, 10 , 1652. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01652

Chen, C., & Du, X. (2021). Teaching and learning Chinese as a foreign language through intercultural online collaborative projects. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher . https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-020-00543-549

Chen, L., Wong, S. L., & How, S. P. (2023). A systematic review of factors influencing student interest in online homework. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 18 , 39. https://doi.org/10.58459/rptel.2023.18039

Dos Santos, L. M. (2021). Developing bilingualism in nursing students: Learning foreign language beyond the nursing curriculum. Healthcare, 9 (3), 326. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9030326

Dos Santos, L. M. (2022). Online learning after the COVID-19 pandemic: Learners’ motivations. Frontiers in Education, 7 , 879091. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.879091

Elias, A. L., Elliott, D. G., & Elliott, J. A. W. (2017). Student perceptions and instructor experiences in implementing an online homework system in a large second-year engineering course. Education for Chemical Engineers, 21 , 40–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ece.2017.07.005

Elmehdi, H. (2013). An evaluation of web-based homework (WBH) delivery system: University of Sharjah experience. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 8 (4), 57–62. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v8i4.2966

Fatmawati, O. A. (2021). Does Kahoot Challenge Mode Motivate Students’ Better Than Google Form in Doing Online Homework? Journal of English Language Teaching Learning and Literature, 4 (2), 15–27.

Fries, R., Cross, B., Rossow, M., & Woehl, D. (2013). Student perceptions of online statics homework tools. Journal of Online Engineering Education, 4 (2), 1–7.

Gerhart, L. M., & Anderton, B. N. (2021). Engaging students through online video homework assignments: A case study in a large-enrollment ecology and evolution course. Ecology and Evolution, 11 , 5777–5789. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.7547

González, J. A., Giuliano, M., & Pérez, S. N. (2022). Measuring the effectiveness of online problem solving for improving academic performance in a probability course. Education and Information Technologies, 27 (5), 6437–6457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10876-7

Hampton, K. N., Robertson, C. T., Fernandez, L., Shin, I., & Bauer, J. M. (2021). How variation in internet access, digital skills, and media use are related to rural student outcomes: GPA, SAT, and educational aspirations. Telematics and Informatics, 63 , 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2021.101666

Ho, C.-T.B., Chou, Y.-H.D., & Fang, H.-Y. (2016). Technology adoption of podcast in language learning: Using Taiwan and China as examples. International Journal of e-Education, e-Business, e-Management and e-Learning, 6 (1), 1–12.

Hoque, R., & Sorwar, G. (2017). Understanding factors influencing the adoption of mHealth by the elderly: An extension of the UTAUT model. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 101 , 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2017.02.002

Huang, F., Teo, T., & Zhou, M. M. (2019). Chinese students’ intention to use the internet-based technology for learning. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68 , 575–591. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-019-09695-y

Ingalls, V. (2018). Incentivizing with bonus in a college statistics course. Journal of Research in Mathematics Education, 7 (1), 93–103. https://doi.org/10.17583/redimat.2018.2497

Kersey, E., Max, B., Akarsu, M., Bloome, L., Suazo, E., & Hoffman, A. (2019). Use of written curriculum in applied calculus. International Journal of Research in Education and Science, 5 (2), 457–467.

Khechine, H., Raymond, B., & Augier, M. (2020). The adoption of a social learning system: Intrinsic value in the UTAUT model. British Journal of Educational Technology, 51 (6), 2306–2325. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12905

Lazarova, K. (2015). The role of online homework in low-enrollment college introductory physics courses. Journal of College Science Teaching, 44 (3), 17–21.

Liberatore, M. W., Morrish, R. M., & Vestal, C. R. (2017). Effectiveness of just in time teaching on student achievement in an introductory thermodynamics course. Advances in Engineering Education, 6 (1), 1–15.

Magalhães, P., Ferreira, D., Cunha, J., & Rosário, P. (2020). Online vs traditional homework: A systematic review on the benefits to students’ performance. Computer & Education, 152 , 103869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.103869

McCollum, B., Morsch, L., Shokoples, B., & Skagen, D. (2019). Overcoming barriers for implementing international online collaborative assignments in chemistry. Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning . https://doi.org/10.5206/cjsotl-rcacea.2019.1.8004

Mikko, V., Stefan, R., & Gottfried, M. (2018). Online homework in engineering mathematics: Can we narrow the performance gap. International Journal of Engineering Pedagogy, 8 (1), 29–42. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijep.v8i1.7526

Mohammad, T. H. N., & Elaine, L. D. (2014). Online assessments in pharmaceutical calculations for enhancing feedback and practice opportunities. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, 6 , 807–814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cptl.2014.07.010

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altaman, D. C. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151 (4), 264–269. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535

Morgan, A. (2013a). Factors influencing student use of online homework management systems. Recognizing Excellence in Business Education, 98 , 98–112.

Morgan, A. (2013b). Building a model to measure the impact of an online homework manager on student learning in accounting courses. Business Education Innovation Journal, 5 (1), 67–73.

Mouza, C., & Lavigne, N. (2013). Introduction to emerging technologies for the classroom: A learning sciences perspective. Explorations in the Learning Sciences, Instructional Systems and Performance Technologies, 1–12.

Murphy, R., Roschelle, J., Feng, M. Y., & Mason, C. A. (2020). Investigating efficacy, moderators and mediators for an online mathematics homework intervention. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 13 (2), 235–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2019.1710885

Mzoughi, T. (2015). An investigation of student web activity in a “flipped” introductory physics class. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 191 , 235–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.558

Parker, L. L., & Loudon, G. M. (2013). Case study using online homework in undergraduate organic chemistry: Results and student attitudes. Journal of Chemical Education, 90 , 37–44.

Powers, K. L., Brooks, P. J., Galazyn, M., & Donnell, S. (2016). Testing the efficacy of MyPsychLab to replace traditional instruction in a hybrid course. Psychology Learning and Teaching, 15 (1), 6–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475725716636514

Raines, J. (2016). Student perceptions on using MyMathLab to complete homework online. Journal of Student Success and Retention, 3 (1), 1–31.

Rentler, B. R., & Apple, D. (2020). Understanding the acceptance of e-learning in a Japanese university English program using the technology acceptance model. APU Journal of Language Research, 5 , 22–37. https://doi.org/10.34409/apujlr.5.0_22

Richards-Babb, M., Drelick, J., Henry, Z., & Robertson-Honecker, J. (2011). Online homework, help or hindrance? What students think and how they perform. Journal of College Science Teaching, 40 (4), 81–93.