Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Justifying gender discrimination in the workplace: The mediating role of motherhood myths

Contributed equally to this work with: Catherine Verniers, Jorge Vala

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Paris Descartes University, Sorbonne Paris Cité, Paris, France, Institute of Social Sciences, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Institute of Social Sciences, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal

- Catherine Verniers,

- Published: January 9, 2018

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190657

- Reader Comments

18 Jul 2018: Verniers C, Vala J (2018) Correction: Justifying gender discrimination in the workplace: The mediating role of motherhood myths. PLOS ONE 13(7): e0201150. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201150 View correction

The issue of gender equality in employment has given rise to numerous policies in advanced industrial countries, all aimed at tackling gender discrimination regarding recruitment, salary and promotion. Yet gender inequalities in the workplace persist. The purpose of this research is to document the psychosocial process involved in the persistence of gender discrimination against working women. Drawing on the literature on the justification of discrimination, we hypothesized that the myths according to which women’s work threatens children and family life mediates the relationship between sexism and opposition to a mother’s career. We tested this hypothesis using the Family and Changing Gender Roles module of the International Social Survey Programme. The dataset contained data collected in 1994 and 2012 from 51632 respondents from 18 countries. Structural equation modellings confirmed the hypothesised mediation. Overall, the findings shed light on how motherhood myths justify the gender structure in countries promoting gender equality.

Citation: Verniers C, Vala J (2018) Justifying gender discrimination in the workplace: The mediating role of motherhood myths. PLoS ONE 13(1): e0190657. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190657

Editor: Luís A. Nunes Amaral, Northwestern University, UNITED STATES

Received: October 6, 2017; Accepted: December 18, 2017; Published: January 9, 2018

Copyright: © 2018 Verniers, Vala. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are available from the GESIS Data Archive (doi: 10.4232/1.2620 and doi: 10.4232/1.12661 ).

Funding: This work was conducted at the Institute of Social Sciences, University of Lisbon, Portugal, and supported by a travel grant of the European Association for Social Psychology, http://www.easp.eu/ , and a travel grant of the Association pour la Diffusion de la Recherche en Psychologie Sociale, http://www.adrips.org/wp/ , attributed to the first author. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

The latest release from the World Economic Forum—the Gender Gap Report 2016 [ 1 ]–indicates that in the past 10 years, the global gender gap across education and economic opportunity and politics has closed by 4%, while the economic gap has closed by 3%. Extrapolating this trajectory, the report underlines that it will take the world another 118 years—or until 2133 –to close the economic gap entirely. Gender inequalities are especially blatant in the workplace. For instance, on average women are more likely to work part-time, be employed in low-paid jobs and not take on management positions [ 2 , 3 ].

There is evidence that gender inequalities in the workplace stem, at least in part, from the discrimination directed against women. Indeed, several studies have documented personal discrimination against women by decision makers (for meta-analyses see [ 4 , 5 ], some of them having more specifically examined the role of the decision makers’ level of sexist attitudes on discriminatory practices. For instance, Masser and Abrams [ 6 ] found in an experimental study that the higher the participants scored in hostile sexism, the more they were likely to recommend a male candidate rather than a female one for a managerial position. In spite of consistent evidence that higher sexism is related to greater bias toward working women [ 7 ], little is known regarding the underlying processes linking sexism to discrimination. This question remains an important one, especially because the persistence of gender discrimination contradicts the anti-discrimination rules promoted in modern societies. In fact, the issue of gender equality in employment has given rise to numerous policies and institutional measures in advanced industrial countries, all aimed at tackling gender discrimination with respect to recruitment, promotion and job assignment. In the USA, for instance, the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1963 Equal Pay Act provided the legal foundation for the implementation of anti-discrimination laws within the workplace. The Treaty on the European Union and the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU, all contain provisions relating to the promotion of equality between women and men in all areas, and the prohibition of discrimination on any ground, including sex. The member states of the European Union must comply with these provisions [ 8 ]. In this respect, some countries have incorporated legislation on equal treatment of women and men into general anti-discrimination laws (e.g., Austria, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Germany, Ireland, Poland, Slovenia, Sweden, Great Britain), while other countries have opted for a specific gender equality act (e.g., Spain). Comparable policies have been implemented in the Asian-Pacific area, with countries including gender equality into broad anti-discrimination laws (e.g., Australia), and other countries having passed laws especially dedicated to addressing discrimination against women (e.g., Japan, the Philippines). The purpose of this research is to further explore the psychosocial process involved in the stubborn persistence of gender discrimination in the workplace, using a comparative and cross-sectional perspective of national representative samples.

Psychosocial processes involved in justified discrimination

According to several lines of research [ 9 – 13 ], the expression of prejudice in contexts where social and political anti-discrimination values are prevalent implies justifications. Crandall and Eshleman [ 10 ] defined justifications as “any psychological or social process that can serve as an opportunity to express genuine prejudice without suffering external or internal sanction”. According to social dominance theory, justification of practices that sustain social inequality arises through the endorsement of legitimizing myths [ 13 ]. Moreover, research conducted in the field of system justification theory has extensively documented an increased adherence to legitimizing ideologies (including social stereotypes, meritocracy, political conservatism, etc.) in contexts where motivation to justify unequal social arrangements is heightened [ 14 – 17 ]. Relying on this literature Pereira, Vala and Costa-Lopes [ 18 ] provided evidence of the mediational role of myths about social groups on the prejudice-support for discriminatory measures relationship. Specifically, they demonstrated that the myths according to which immigrants take jobs away from the host society members and increase crime rates mediated the relationship between prejudice and opposition to immigration (see also [ 19 ]). We assume that an equivalent mediational process underlies the justification of gender discrimination in the workplace or, put differently, that the sexism-opposition to women’s career relationship is mediated by legitimizing myths. Glick and Fiske [ 20 ] conceptualised sexism as a multidimensional construct that encompasses hostile and benevolent sexism, both of which having three components: paternalism, gender differentiation and heterosexuality. We suspect that the gender differentiation component of sexism in particular may be related to gender discrimination in the workplace, because the maintenance of power asymmetry through traditional gender roles is at the core of this component [ 20 ]. Accordingly, it is assumed that the higher the endorsement of sexist attitudes regarding gender roles in the family, the higher the opposition to women’s work. In support of this assumption, Glick and Fiske [ 21 ] stated that gender roles are part of the more general interdependence between women and men occurring in the context of family relationships and, importantly, that these traditional, complementary gender roles shape sex discrimination. However, given that the expression of hostility towards women became socially disapproved [ 22 , 23 ] and that gender discrimination in the workplace is subjected to sanctions (see for instance [ 24 ]), the release of sexism with regard to women’s role in the family and women’s professional opportunities may require justification [ 10 , 19 ].

Motherhood myths as a justification for gender discrimination

Compared with other intergroup relations, gender relations present some unique features (e.g., heterosexual interdependence; [ 25 , 26 ] and accordingly comprise specific myths and ideologies aimed at maintaining the traditional system of gender relations [ 27 – 29 ]. For instance, the belief that marriage is the most meaningful and fulfilling adult relationship appears as a justifying myth, on which men and women rely when the traditional system of gender relations is challenged by enhanced gender equality measured at the national level [ 30 ]. Drawing on this literature, we propose that beliefs that imbue women with specific abilities for domestic and parental work ensure that the traditional distribution of gender roles is maintained. In particular, we suggest that motherhood myths serve a justification function regarding gender discrimination against women in the workplace. Motherhood myths include the assumptions that women, by their very nature, are endowed with parenting abilities, that at-home mothers are bonded to their children, providing them unrivalled nurturing surroundings [ 31 , 32 ]. Conversely, motherhood myths pathologised alternative mothering models, depicting employed mothers as neglecting their duty of caring, threatening the family relationships and jeopardizing mother-children bondings (see [ 33 ] for a critical review of these myths). Motherhood myths have the potential to create psychological barriers impairing women’s attempt to seek power in the workplace [ 34 ] and men’s involvement in child care [ 35 – 37 ]. We suggest that beyond their pernicious influence at the individual level of parental choices, motherhood myths might operate more broadly as justifications for gender discrimination regarding career opportunity. This question is of particular relevance given that equal treatment in the workplace appears even more elusive for women with children—the maternal wall [ 38 ] (see also [ 39 – 45 ]). At the same time, recognizing the pervasive justifying function of motherhood myths may help understand the psychosocial barriers faced not only by women who are mothers, but by women as a whole since "women are expected to become mothers sooner or later" (Dambrin & Lambert [ 46 ], p. 494; see also [ 47 ]). Relying on previous work documenting the mediational role of legitimizing myths on the prejudice—discrimination relationship [ 18 , 19 ] we suggest that the myths according to which women pursuing a career threaten the well-being of the family mediates the relationship between sexist attitudes regarding gender roles and opposition to women’s work.

Exploring gender and time as possible moderators of the hypothesized mediation

Besides the test of the main mediational hypothesis, the present research sought to explore time and gender as possible moderators of the assumed relationship between sexism, motherhood myths and discrimination. A review of the historical development of gender equality policies confirms that the implementation of laws and regulations aimed at eliminating gender discrimination in the workplace is a lengthy process (e.g., for the European countries see [ 48 ]; for the USA see [ 49 ]). In fact, although the basic principle of anti-discrimination has been enacted by many countries in the second half of the 20 th century, some measures are still adopted nowadays, such as the obligation for employers to publish information by 2018 about their bonuses for men and women as part of their gender pay gap reporting, a provision recently taken by the UK government. As egalitarian principles have gradually progressed in societies, it is likely that the expression of intergroup bias has become steadily subjected to social sanction. Thus, “as with racism, normative and legislative changes have occurred in many industrialized societies that make it less acceptable to express sexist ideas openly” (Tougas, Brown, Beaton, & Joly, [ 50 ], p. 843; see also [ 51 ]). Accordingly, gender discrimination within organizations became less intense and more ambiguous [ 52 – 54 ]. In line with this reasoning, the use of motherhood myths as a justification for unequal career opportunities may have increased over time. Conversely, it has been suggested that along with the increasing female participation in the labour market over the last decades, a positive attitude regarding the government-initiated women-friendly policies now coexists with an adherence to traditional family values and norms [ 55 ]. There is a possibility that the coexistence of contradictory norms in the same culture may leave some room for the expression of gender bias (i.e., a normative compromise, [ 56 ]), reducing slightly the need to rely on justifications to discriminate against working women. The present research will examine these possibilities by studying the role of motherhood myths on the sexism—discrimination relationship in 1994 and 2012.

Another possible moderator examined in the present study is the respondents' gender. Basically, the reason why people rely on justifications is to express their genuine prejudices without appearing biased. Consistent evidence, however, suggests that the perpetrator’s gender affects people’s perception of sexism towards women: given that sexism is generally conceived as involving a man discriminating against a woman, men are perceived as prototypical of the perpetrator [ 57 , 58 ]. As a consequence, sexist behaviours carried out by males are perceived as more sexist than the same behaviours enacted by females [ 59 , 60 ]. Moreover, the expression of sexism by women may go undetected due to the reluctance of women to recognize that they might be harmed by a member of their own gender group [ 22 ]. Taken together, these findings suggest that a woman is more likely than a man to express sexist bias without being at risk of appearing sexist. In line with this reasoning, one could assume that men need to rely on justifications to discriminate to a greater extent than women do. Alternatively, women expressing sexism against their ingroup members are at risk of being negatively evaluated for violating the prescription of feminine niceness [ 61 , 62 ]. As a consequence, women might be inclined to use justifications to discriminate in order to maintain positive interpersonal evaluations. An additional argument for assuming that women may rely on motherhood myths lies in the system justification motive. According to system justification theory [ 63 , 64 ], people are motivated to defend and justify the status quo, even at the expense of their ingroup. From this perspective, the belief that every group in society possesses some advantages and disadvantages increases the belief that the system is balanced and fair [ 29 , 65 ]. Motherhood myths imbue women with a natural, instinctual and biologically rooted capacity to raise children that men are lacking [ 66 ]. In addition, they convey gender stereotype describing women in positive terms (e.g., considerate, warm, nurturing) allowing a women-are-wonderful perception [ 27 ]. As a consequence, women are likely to rely on motherhood myths to restore the illusion that, despite men structural advantage [ 67 , 68 ], women as a group still possess some prerogatives [ 34 ].

The aim of the present study is to test the main hypothesis (H1) that motherhood myths are a justification that mediates the relationship between sexism and opposition to women’s work following the birth of a child. Additionally, two potential moderators of this mediational process are considered. The present research tests the exploratory hypotheses that (H2) the assumed mediational process is moderated by time and (H3) by participants’ gender. We tested these hypotheses using the Family and Changing Gender Roles module of the International Social Survey Programme [ 69 , 70 ]. This international academic project, based on a representative probabilistic national sample, deals with gender related issues, including attitudes towards women’s employment and household management. Hence this database enables a test of the proposed mediational model on a large sample of female and male respondents and data gathered 18 years apart.

We used the 2012 and 1994 waves of the ISSP Family and Changing Gender Roles cross-national survey [ 69 , 70 ]. The ISSP published fully anonymized data so that individual survey participants cannot be identified. The two databases slightly differed regarding the involved countries, some of which did not participate in the two survey waves. In order to maintain consistency across the analyses, we selected 18 countries that participated in both survey waves (i.e., Austria, Australia, Bulgaria, Canada, Czech Republic, Germany, Great Britain, Ireland, Israel, Japan, Norway, Philippines, Poland, Russia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and the USA). The data file for the 2012 survey wave included 24222 participants (54.4% female participants), mean age = 49.38, SD = 17.54, and the data file for the 1994 survey wave included 27410 participants (54.4% female participants), mean age = 44.26, SD = 17.07.

The main variables used in this study are the following:

One indicator was used to capture sexism: “A man's job is to earn money; a woman's job is to look after the home and family”. This item taps into the gender differentiation component of sexism [ 20 , 25 ]. Participants answered on a 5 point likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree. Data was recoded so that the higher scores reflected higher sexism.

Motherhood myths.

Two indicators were used that capture the myths about the aversive consequence of mother’s work for her child and the family: “A preschool child is likely to suffer if his or her mother works” and “All in all, family life suffers when the woman has a full-time job”. Participants answered on a 5 point likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree. Data was recoded so that the higher scores reflected higher endorsement of motherhood myths.

Opposition to women’s career.

Two indicators were used to capture the opposition to women’s professional career following the birth of a child: “Do you think that women should work outside the home full-time, part-time or not at all when there is a child under school age?” and “Do you think that women should work outside the home full-time, part-time or not at all after the youngest child starts school?” Participants answered on a scale ranging from 1 = work full time, 2 = work part-time, 3 = stay at home.

In addition, the first step of our analyses involved the following control variables: participant’s gender and age, partnership status, educational level, subjective social status, attendance of religious services and political orientation.

The following section presents the results of a four-step analysis: The first step consists of a preliminary hierarchical regression analysis to establish the respective contributions of demographical variables, sexism and motherhood myths to opposition to women’s work. The second step is dedicated to a test of the construct validity of the proposed measurement model using Confirmatory Factor Analyses. The third step involves a test of the hypothesized mediation. Finally, the last step is a test of the hypothesized moderated mediations.

Step 1: Hierarchical regression analysis

Inspection of the correlation matrix ( Table 1 ) indicates that all the correlations are positive, ranging from moderate to strong. The pair of items measuring motherhood myths presents the strongest correlation ( r (48961) = .633), followed by the pair of items measuring opposition to women’s career ( r (45178) = .542).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190657.t001

We conducted a hierarchical regression analysis to establish the respective contributions of demographical variables, sexism and motherhood myths to opposition to women’s work. In block 1, participant’s gender (male = -1, female = 1) and partnership (no partner = -1, partner = 1) were entered together with standardized scores of age, years of schooling, subjective social status, attendance of religious services and political orientation. Block 2 included sexism, the myths about the aversive consequence of mother’s work for her child and for family (all standardized). Predictors in block 1 accounted for 9% of the variance, F (7, 10140) = 157.89, p < .001. The analysis revealed the significant effects of participant’s gender ( B = -.033, SE = .006, p < .001), age ( B = .058, SE = .006, p < .001), years of schooling ( B = -.135, SE = .007, p < .001), subjective social status ( B = -.057, SE = .007, p < .001), religiosity ( B = .076, SE = .006, p < .001) and political orientation ( B = .04, SE = .006, p < .001). Partnership was unrelated to opposition to women’s career ( B = .002, SE = .006, p = .77). Taken together the results indicate that the higher the time of education and the subjective social status, the lower the opposition to women’s work. Conversely, the higher the age, religiosity and political conservatism, the higher the opposition to women’s work. Finally, results indicate that opposition to women’s work is more pronounced amongst men than amongst women. When entered in block 2, sexism and motherhood myths accounted for an additional 18% of the variance, indicating that these variables significantly improved the model’s ability to predict opposition to women’s work, over and above the contributions of gender, partnership, education, social status, religiosity and political orientation (Δ R 2 = .18), Δ F (3, 10137) = 854.04, p < .001. Specifically, the analysis revealed the significant effects of sexism ( B = .151, SE = .006, p < .001), myth about the aversive consequence of mother’s work for her child ( B = .10, SE = .007, p < .001) and myth about the aversive consequence of women’s work for family ( B = .09, SE = .007, p < .001). It should be noted that the effect of participant’s gender virtually disappeared after controlling for sexism and motherhood myths ( Table 2 ). In addition, we performed this hierarchical regression analysis separately for the two waves and consistently found that the variables of our model (sexism and the motherhood myths) explained more variance than the demographical variables.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190657.t002

Step 2: Confirmatory factor analyses

We conducted a CFA to check the construct validity of the proposed measurement model. CFA and subsequent analyses were all performed using R. 3.4.1 and the Lavaan package [ 71 ]. The loading of the single indicator of the sexism variable and the loading of the first indicator of the motherhood myths and opposition variables were constrained to 1.00 [ 72 ], and the three variables were allowed to correlate. Results show a good fit to the data, χ 2 (3, N = 42997) = 400.36, p < .001, CFI = .993, RMSEA = .05 [90% CI = .05, .06], SRMR = .01, AIC = 540804. In addition, we estimated an alternative model in which all items loaded on a unique latent variable. This alternative model shows a poorer fit to the data, χ 2 (5, N = 42997) = 8080.28, p < .001, CFI = .867, RMSEA = .19 [90% CI = .19, .19], SRMR = .07, AIC = 548480. The comparison of the two models indicates that the proposed measurement model fits the data better than the alternative one, Δ χ 2 (2, 42997) = 7679.9, p < .001. We repeated this comparison in each country and results confirm that the proposed measurement model fits better in all countries (see S1 Table for comparative test of the goodness of fit of the hypothesized measurement model vs. alternative measurement model in each country).

We tested the measurement invariance of the CFA model across the two survey waves. To do this, we conducted a model comparison to test for configural and metric invariances. Results indicate that the configural invariance can be retained, χ 2 (6, N = 42997) = 513.05, p < .001, CFI = .991, RMSEA = .06 [90% CI = .05, .06], SRMR = .01, AIC = 537580. When constraining the loadings to be equal across waves fit indices remain satisfactory, χ 2 (8, N = 42997) = 679.58, p < .001, CFI = .989, RMSEA = .06 [90% CI = .05, .06], SRMR = .02, AIC = 537743. The change in CFI is below the cutpoint of .01, indicating that the metric invariance can be retained and that further comparisons of the relationships between constructs across survey waves can be performed [ 73 , 74 ]. Furthermore, we repeated this comparison in each country and results support the configural invariance of the CFA model across survey waves in all countries. In addition, the full metric invariance is obtained in all but three countries—Poland, Slovenia and the USA. In these countries, the CFIs are larger than the cutpoint of .01, indicating a lack of full metric invariance. Nonetheless, we were able to retain a partial metric invariance of the CFA model across the survey waves by setting free one non-invariant loading [ 75 ], (see S2 Table for the test of the invariance of the measurement model across survey waves by country).

We tested the measurement invariance of the CFA model across gender groups using the same procedure as for the test of the measurement invariance across survey waves. The baseline model constraining the factor structure to be equal in the two gender groups shows good fit to the data, χ 2 (6, N = 42943) = 440.95, p < .001, CFI = 0.993, RMSEA = .05 [90% CI = .05, .06], SRMR = .01, AIC = 539573, indicating that the configural invariance is achieved for the two groups. Then we fitted a more restricted model in which the factor loadings were constrained to be equal across groups. This model allows testing for the metric invariance (equal loadings) of the model across gender. Once again, the results indicate that this constrained model show good fit to the data, χ 2 (8, N = 42943) = 469.14, p < .001, CFI = 0.992, RMSEA = .05 [90% CI = .04, .05], SRMR = .01, AIC = 539598. Furthermore, the Δ CFI is below the cutpoint of .01, indicating that the metric invariance can be retained [ 75 ]. This result confirms that cross gender comparisons of the relationships between constructs can reasonably be performed. Furthermore, we repeated this procedure in each country. Once again, the Δ CFIs are below the cutpoint of .01, indicating that the configural invariance of the CFA model across gender groups is achieved in all countries (see S3 Table for the test of the invariance of the measurement model across gender groups by country).

Step 3. Mediation analysis

Overview of the analysis strategy..

This study main hypothesis is that (H1) the more people hold sexist attitude regarding gender roles, the more they endorse motherhood myths, which in turn enhances the opposition to women’s career after the birth of a child. In order to test this assumption, we ran mediational analyses using structural equation modelling. First, we examined the goodness of fit of the hypothesized mediational model and compared it with the goodness of fit of two alternative models. In the first alternative model, motherhood myths predict sexism that, in turn, predicts opposition. In the second alternative model, opposition to women’s career predicts motherhood myths. After having established that the hypothesized model adequately fit the data, we examined the coefficients for the hypothesized relationships between variables.

Goodness of fit of the models.

Inspection of the fit indices indicates that the hypothesized model fits the data better than the first alternative model in 16 out of the 18 analysed countries ( Table 3 ). Thus, in these countries the data is better accounted for by a model stating motherhood myths as a mediator of the sexism-opposition to women’s career relationship, rather than by a model stating sexism as a mediator of the myths-opposition to women’s career relationship. The comparison of the fit indices indicates that the two models fit the data to almost the same extent in the two remaining countries (i.e., Czech Republic, and Philippines). Finally, the second alternative model—where opposition to women’s career predicted motherhood myths and sexism—shows very poor fit to the data in all countries. This result suggests that endorsement of motherhood myths is not a mere consequence of discrimination.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190657.t003

Test of the relationships between variables.

The goodness of fit of the proposed mediational model having been established in 16 countries out of 18, we next examined the coefficients for the hypothesized relationships in these countries. Table 4 shows the results of the mediation analysis in the 16 retained countries. The total effect of sexism on opposition to women’s career is positive and significant in all countries. The direct effect is reduced in all countries when controlling for the indirect effect through motherhood myths. As recommended in the literature, the indirect effects were subjected to follow-up bootstrap analyses using 1000 bootstrapping resamples [ 76 ]. The null hypothesis is rejected and the indirect effect is considered significant if the 95% confidence intervals (CI) do not include zero. All bias corrected 95% CI for the indirect effect excluded zero, indicating that in line with H1, endorsement of motherhood myths is a significant mediator of the relationship between sexism and opposition to women’s career in all countries.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190657.t004

In order to provide an overview of the proposed mediational model, we next present the analyses conducted on the total of the 16 countries retained. The hypothesized mediational model shows acceptable fit to the data, χ 2 (4, N = 38178) = 971.09, p < .001, CFI = .983, RMSEA = .08 [90% CI = .07, .08], SRMR = .04, AIC = 473476. Inspection of the fit indices of the first alternative model where endorsement of motherhood myths predicted sexism that, in turn, predicted opposition confirms that this alternative model shows poorer fit to the data than the proposed model, χ 2 (4, N = 38178) = 7583.1, p < .001, CFI = .870, RMSEA = .22 [90% CI = .21, .22], SRMR = .13, AIC = 480088. The second alternative model, where opposition to women’s career predicted motherhood myths shows poor fit to the data, χ 2 (5, N = 38178) = 14224.61, p < .001, CFI = .756, RMSEA = .27 [90% CI = .26, .27], SRMR = .21, AIC = 486728, and accordingly fits the data less well than the proposed mediational model, Δ χ 2 (1, 38178) = 13254 p < .001. As can be seen in Fig 1 , the standardized regression coefficient for the direct effect of sexism on opposition to women’s career is significant ( β = .16, p < .001). In addition, the unstandardized estimate for the indirect effect excludes zero (.13, SE = 0.003, bias corrected 95% CI [.12, .13]) and, therefore, is significant. Taken together, analyses conducted on the whole sample, as well as on each country separately, support our main assumption that endorsement of motherhood myths is a significant mediator of the relationship between sexism and opposition to women’s career.

The coefficient in parentheses represents parameter estimate for the total effect of prejudice on opposition to women’s career. *** p < .001.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190657.g001

Step 4. Moderated mediation analyses

Indirect effect through survey waves..

The moderated mediation model was estimated using a multiple group approach. This model exhibits good fit to the data, χ 2 (6, N = 38178) = 438.88, p < .001, CFI = .992, RMSEA = .06 [90% CI = .05, .06], SRMR = .01. The standardized coefficients for the total effect are .50 in the 2012 survey, and .52 in the 1994 survey. The unstandardized estimates for the indirect effect is .10, SE = 0.003, bias corrected 95% CI [.10, .11] in the 2012 survey, and .11, SE = 0.003, bias corrected 95% CI [.10, .11] in the 1994 survey. The intervals do not include zero, indicating that motherhood myths are a significant mediator of the relationship between sexism and opposition to women’s career in both survey waves. The difference between the indirect effect in 2012 and 1994 is not significant (-.003, SE = 0.004, bias corrected 95% CI [.-.01, .00]). We repeated the moderated mediation analysis in each country. As can be seen in Table 5 , the indirect effect reaches significance in each survey wave in all countries. The indirect effect is not moderated by the survey year, except in Great Britain where the indirect effect, although still significant, decreased between 1994 and 2012, and Bulgaria, Poland, and Russia where the indirect effect slightly increased between 1994 and 2012.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190657.t005

Indirect effect as a function of the respondents’ gender.

The moderated mediation model exhibits good fit to the data, χ 2 (6, N = 38124) = 402.46, p < .001, CFI = .993, RMSEA = .06 [90% CI = .05, .06], SRMR = .01. The total effect of sexism on opposition to women’s career is positive and significant for both men ( β = .52, p < .001) and women ( β = .50, p < .001). The standardized indirect effect of sexism on opposition to women’s career through motherhood myths is .27 in the male subsample, and .29 in the female subsample. The unstandardized estimates for the indirect effect is .11, SE = 0.003, bias corrected 95% CI [.10, 12] in the male sample, and .10, SE = 0.003, bias corrected 95% CI [.09, .10] in the female sample. The intervals do not include zero, indicating that motherhood myths are a significant mediator of the relationship between sexism and opposition to women’s career among both men and women respondents. The difference between the indirect effect among men and women is not statistically significant (.01, SE = 0.004, bias corrected 95% CI [.00, .01]). We repeated this analysis in each country separately (see Table 6 ). Results confirm that the indirect effect of sexism on opposition to women’s career through motherhood myths is not moderated by the respondents’ gender in 15 out of the 16 countries. The only exception is Poland. In this country, the indirect effect is stronger for the female than for the male respondents.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190657.t006

Using a large representative sample of respondents from various countries the present research documented a psychosocial process of justification of discrimination against working women with children. As a preliminary step, hierarchical regression analysis established that sexism and motherhood myths predict opposition to women’s work, over and above gender, partnership, education, social status, religiosity and political orientation. Furthermore, structural equation modellings on the whole sample, as well as on each country separately, confirmed our main hypothesis that endorsement of motherhood myths mediates the relationship between sexism and opposition to women’s career following a birth. In addition, test of the moderated mediation indicated that the indirect effect reaches significance in each survey wave in almost all countries examined without substantial difference. Only in Bulgaria, Poland, and Russia did the indirect effect slightly increase between 1994 and 2012, suggesting that motherhood myths is more a justification for the expression of sexism nowadays than in the late 20 th century. Great Britain shows a reverse pattern with a slight decrease of the indirect effect between the two waves. However, besides these minor variations, it should be noted that motherhood myths remain a significant mediator of the sexism-opposition to women’s career relationship in all countries. The present research also considered participants' gender as a potential moderator of the indirect effect, and results indicated that the process of justification of discrimination against working women does not differ as a function of the respondents' gender. The only exception to this finding is Poland where the indirect effect is indeed stronger among women than among men. An examination of the specific features of female employment in this country sheds some light on this result. Young women in Poland are better educated than young men and are more likely to have permanent employment than men [ 77 ]. At the same time however, working women spend on average two and a half hours per day on unpaid work more than men—which is reflected by the fact that more than 1 in 3 women reduce their paid hours to part-time, while only 1 in 10 men do the same—and are predominant users of parental leave [ 3 ]. It is noteworthy that reduced working hours (and long periods of leave) hinders female career progression through less training, fewer opportunities for advancement, occupational segregation, and lower wages [ 78 , 79 ]. Accordingly, in Poland women earn 9% less than men (one of the lowest gender pay gap in OECD) but the pay gap reaches 22% by presence of children (above the OECD average of 16%; [ 77 ]). The fact that women appear even more inclined than men to rely on motherhood myths to justify gender discrimination is consistent with a system justification perspective [ 63 ]. Drawing on the logic of cognitive dissonance theory, system justification theory in its strong form posits that members of disadvantaged groups may be even more likely than members of advantaged groups to support existing social inequalities [ 64 ]. The rational is that members of disadvantaged groups would experience psychological discomfort stemming from the concurrent awareness of their ingroup's inferiority within the system, and of their ingroup's contribution to that system. Justification of the status quo would therefore reduce dissonance [ 80 ]. The finding that women strongly rely on motherhood myths to justify gender discrimination precisely in a country with strong motherhood penalty can be regarded as an expression of this system justification motive.

The present research sheds new light on the effect of macrolevel inequality on the justification of discrimination, and more broadly on the process of legitimation of gender inequalities [ 9 , 81 ]. In a recent study, Yu and Lee [ 82 ] found a negative association between women’s relative status in society and support for gender equality at home. More specifically, the authors found that although respondents in countries with smaller gender gaps express greater support for women’s participation in the labour force, they still exhibit less approval for egalitarian gender roles within the household, in particular regarding the share of domestic chores and childcare. As an explanation, the authors argued that the less traditional the gender division of labour is in a society, the more people need to express their freedom of maintaining these roles and to defend the gender system, leading to the endorsement of gender differentiation in the private sphere. However, the present research allows an alternative explanation for this seemingly paradoxical finding to be suggested. At a macrolevel, higher gender equality conveys strong suppressive factors (which reduce the expression of prejudice) by demonstrating that the society promotes egalitarianism between women and men. In parallel, the gender specialization in the division of the household responsibilities and especially regarding childcare provides a strong justifying factor (which releases prejudice) by emphasising essential differences between gender groups [ 26 ]. Thus, the counterintuitive finding that the more egalitarian a society is, the less people support gender equality at home may indeed reflect an attempt to justify the release of genuine sexism. Conversely, it is likely that a less egalitarian society brings with it some degree of tolerance towards gender discrimination, reducing the need to rely on justifications to express sexism. A closer look at our results regarding Norway and Japan supports this view. Norway and Japan appears as especially contrasted regarding gender equality, in particular with regard to economic participation and opportunity [ 1 ]. According to the World Economic Forum, Norway has the second smallest gender gap in the world. In addition, gender equality promotion is frequently mobilised both in political debates and in mainstream society [ 55 ]. For its part, Japan ranks 101 st on the overall gender gap index, which makes Japan well below average compared to other advanced industrial countries [ 83 ]. Besides this gender gap, consistent research reports a unique trivialisation of anti-gender equality discourses in the media [ 84 ] and of gender-based discriminatory behaviours in the workplace, including sexual harassment [ 85 ]. Comparing the strength of the indirect effect of sexism on opposition to women’s career through motherhood myths in these two countries ( Table 4 ), it is noteworthy that the coefficient is larger in Norway than in Japan. This result gives support to the assumption that macrolevel gender (in)equality affects the psychological process of justification at the individual level. Future studies should clarify how macrolevel inequalities impact societal norms, which in turn influence legitimation processes.

It is also worth noting that the justifying function of motherhood myths is established in all analysed countries despite some notable differences between parental leaves policies and practices. For instance, the United States are the only OECD country to offer no nationwide entitlement to paid leave, neither for mothers nor for fathers [ 86 ]. On the other hand, the Nordic nations, with Norway and Sweden in the lead, are in the vanguard of progressive policy-making regarding shared parental leave entitlement: Sweden was the first country in the world in 1974 to offer fathers the possibility of taking paid parental leave, quickly joined by Norway in 1978 [ 87 ]. More recently in 2007, Germany introduced a new law aiming at encouraging shared parental leave. In practice, the length of the financial support for parental leave can increase from 12 to 14 months provided that fathers use the parental benefit for at least 2 months. Recent research aiming at investigating whether German men who take parental leave are judged negatively in the workplace revealed that, in contrast with women who experience penalty for motherhood [ 40 ], fathers do not face backlash effect when they take a long parental leave [ 88 ]. The authors concluded that "gender role attitudes have changed". Tempering this view, the present study indicates that even in countries promoting incentives for fathers to take parental leave, motherhood myths—and specifically the belief that mother's work threatens the family—are still a justification for gender discrimination in the workplace. With regard to practices, it should be noted that shared parental leave policies, whose purpose is to foster gender equality in the labor market, often fail to meet this objective, with the majority of fathers actually taking the minimum length of leave entitlement, or no parental leave at all, and the majority of mothers still facing the majority of childcare [ 88 ]. Once again, more research is needed to document the process of mutual influences between changing family policies and the maintenance of the gender status quo via justifying beliefs.

Limitations and future directions

Although the hypothesized mediational process is supported by the data, and is in line with previous experimental findings [ 19 ], conclusion regarding causality are necessarily limited due to the correlational nature of the research. We hope that these preliminary findings will open the way to experimental studies allowing for a conclusion on the direction of causality between variables and the further documenting of the behavioural consequences of the endorsement of motherhood myths. For instance, future studies should consider the extent to which motherhood myths interact with organizational norms to constrain the hiring and promotion of women. Castilla and Benard [ 89 ] showed that when an organization explicitly values meritocracy, managers favour a male employee over an equally qualified female employee. One explanation for this seemingly paradoxical results lies in the legitimation function of meritocracy [ 17 ] which is likely to release the expression of sexism. We suggest that when organizations promote egalitarian norms, or put differently, when organizations set suppression factors, then motherhood myths may serve as a justification for unequal gender treatment regarding career outcomes.

Due to constraints related to the availability of data in the ISSP base, only one indicator was used to capture sexism. This can be regarded as a limitation providing that sexism is typically defined as a complex construct [ 20 ]. We argue that measuring the gender differentiation component of sexism through a single item represents a valid approach, as suggested by previous research indicating that single-item measures may be as reliable as aggregate scales [ 90 – 94 ]. However, using a multiple-item measure of sexism in future studies would provide a more comprehensive examination of the relations between the different components of sexism and opposition to gender equality in the workplace.

The present research focused on opposition to mothers' work as an indicator of gender discrimination. However, evidence suggests that motherhood myths may justify discrimination towards women as a whole rather than mothers only. First, as previously mentioned social roles create gender expectations [ 95 ] so that all women are expected to become mothers [ 47 ]. Furthermore, research using implicit association test indicate that people automatically associate women with family role [ 96 ]. As a consequence, it is plausible that employers rely on motherhood myths to discriminate against women in general regarding recruitement, performance evaluation, and rewards, arguing that women will sooner or later be less involved in work and less flexible for advancement than men [ 97 ]. This justification is compatible with the employers' reluctance to hire women and promote them to the highest positions even in the absence of productivity differences [ 98 ].

Practical implications

In this study we were able to document that motherhood myths are a widespread justification for gender discrimination in the workplace, including in countries with anti-discrimination laws and advanced family policies. From this regard, the present findings help understand the paradoxical effects of family-friendly policies on women's economic attainment. Mandel and Semyonov [ 99 ], using data from 20 countries, found evidence that family policies aimed at supporting women's economic independence, and including provision of childcare facilities and paid parental leaves, increase rather than decrease gender earning gaps. This unexpected effect is due to the fact that family policies are disproportionally used by mothers rather than fathers, with the consequence that mothers are concentrated in part-time employment, female-typed occupations, yet underrepresented in top positions. The authors concluded that "there are distinct limits to the scope for reducing gender wage inequality in the labor market as long as women bear the major responsibility for household duties and child care" (p. 965). We would add that there are strong barriers to the scope for attaining gender equality at home as long as motherhood myths are uncritically accepted and used as justification for unequal gender arrangements. Recent works provided evidence of the efficiency of interventions aimed at reducing sexist beliefs [ 100 ] and at recognizing everyday sexism [ 101 ]. In the same vain, interventions aimed at informing people that motherhood myths are socially constructed and maintained [ 33 ], and that they affect women's advancement and fathers' involvement [ 35 ], would represent a first step towards the reduction of discrimination by depriving individuals of a justification for gender inequalities.

The present research builds on and extends past findings by demonstrating that men and women rely on the belief that women’s work threatens the well-being of youth and family to justify discrimination against working women. If, at an individual level, this process allows discrimination to be exhibited without appearing prejudiced [ 10 ], at the group and societal levels, such a process may contribute to the legitimation and reinforcement of the hierarchical power structure [ 63 ]. By documenting a pervasive process by which people invoke motherhood myths to hinder women’s economic participation, the present research emphasizes the need to be vigilant about any attempts to promote a return to traditional gender roles, an issue of central importance given the contemporary rollback of women’s rights in advanced industrial countries [ 102 ].

Supporting information

S1 table. comparative test of the goodness of fit of the hypothesized measurement model vs. alternative measurement model..

All differences are significant at p < .001.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190657.s001

S2 Table. Test of the invariance of the measurement model across survey waves by country.

In Poland and Slovenia partial metric invariance of the measurement model was attained by setting free the loading of the item “ Do you think that women should work outside the home full-time , part-time or not at all after the youngest child starts school ?” on the “opposition” latent variable. This partly constrained model show good fit indices in Poland, χ 2 (7, N = 2248) = 36.18, p = .006, CFI = .990, RMSEA = .06 [90% CI = .04, .08], and Slovenia, χ 2 (7, N = 1867) = 12.92, p = .058, ns , CFI = .999, RMSEA = .03 [90% CI = .00, .05]. In the USA, partial metric invariance of the measurement model was attained by setting free the loading of the item “ All in all , family life suffers when the woman has a full-time job ” on the “motherhood myths” latent variable, χ 2 (7, N = 2117) = 11.08, p = .069, ns , CFI = .999, RMSEA = .02 [90% CI = .00, .04].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190657.s002

S3 Table. Test of the invariance of the measurement model across gender groups by count.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190657.s003

S1 Supplementary Information. Additional details concerning the way the research was conducted.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190657.s004

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Virginie Bonnot, Cícero Pereira, and several anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper.

- 1. The Global Gender Gap Report: 2016. Geneva: World Economic Forum; 2016.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 3. European Union. Tackling the gender pay gap in the European Union. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2014.

- PubMed/NCBI

- 8. Burri S, van Eijken H. Gender equality law in 33 European countries how are EU rules transposed into national law?. Brussels: European Commission; 2014 [cited 2016 Mar 11]. http://bookshop.europa.eu/uri?target=EUB:NOTICE:DSAD14001:EN:HTML

- 11. Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL. Aversive Racism. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology, Vol 36. San Diego, CA, US: Elsevier Academic Press; 2004. pp. 1–52.

- 12. Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL. Prejudice, discrimination, and racism. Orlando : Academic Press; 1986.

- 13. Sidanius J, Pratto F. Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press; 1999.

- 21. Glick P, Fisk ST. Sex discrimination: The psychological approach. In: Crosby F. J., Stockdale M. S., Ropp S. A., editors. Sex discrimination in the workplace: Multidisciplinary perspectives. Malden, MA: Blackwell; 2007. pp. 155–187.

- 24. Velez et al. v. Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation, 04 Civ.09194; 2010.

- 26. Rudman LA, Glick P. The social psychology of gender: How power and intimacy shape gender relations. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 2008.

- 31. Hays S. The cultural contradictions of motherhood. New Haven; London: Yale University Press; 1998.

- 48. Timmer A, Senden L. A comparative analysis of gender equality law in Europe 2015: A comparative analysis of the implementation of EU gender equality law in the EU Member States, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Montenegro, Norway, Serbia and Turkey. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2016 [cited 2016 Nov 7]. http://bookshop.europa.eu/uri?target=EUB:NOTICE:DS0416376:EN:HTML

- 49. McBride DE, Parry JA. Women’s rights in the USA: policy debates and gender roles. Fifth edition. New York; London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group; 2016.

- 56. Boltanski L, Thévenot L. On justification: economies of worth. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2006.

- 66. Hrdy SB. Mother nature: maternal instincts and how they shape the human species. 1st ed. New York: Ballantine Books; 2000.

- 67. Goodwin SA, Fiske ST. Power and gender: The double-edged sword of ambivalence. In: Unger RK, Unger RK (Ed), editors. Handbook of the psychology of women and gender. Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2001. pp. 358–366.

- 69. ISSP Research Group. International Social Survey Programme: Family and Changing Gender Roles II—ISSP 1994; 1997 GESIS. Data Archive, Cologne. ZA2620 Data file Version 1.0.0, 10.4232/1.2620.

- 70. ISSP Research Group. International Social Survey Programme: Family and Changing Gender Roles IV—ISSP 2012; 2016. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA5900 Data file Version 4.0.0, 10.4232/1.12661.

- 71. R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria; 2017.

- 77. OECD. Closing the gender gap: act now. Paris: OECD; 2012.

- 85. Hidaka T. Salaryman masculinity the continuity of and change in the hegemonic masculinity in Japan [Internet]. Leiden; Boston: Brill; 2010 [cited 2016 Jun 13]. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004183032.i-224

- 86. OECD. Parental leave: Where are the fathers? Paris: OECD; 2016.

REVIEW article

Gender inequalities in the workplace: the effects of organizational structures, processes, practices, and decision makers’ sexism.

- Department of Psychology, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada

Gender inequality in organizations is a complex phenomenon that can be seen in organizational structures, processes, and practices. For women, some of the most harmful gender inequalities are enacted within human resources (HRs) practices. This is because HR practices (i.e., policies, decision-making, and their enactment) affect the hiring, training, pay, and promotion of women. We propose a model of gender discrimination in HR that emphasizes the reciprocal nature of gender inequalities within organizations. We suggest that gender discrimination in HR-related decision-making and in the enactment of HR practices stems from gender inequalities in broader organizational structures, processes, and practices. This includes leadership, structure, strategy, culture, organizational climate, as well as HR policies. In addition, organizational decision makers’ levels of sexism can affect their likelihood of making gender biased HR-related decisions and/or behaving in a sexist manner while enacting HR practices. Importantly, institutional discrimination in organizational structures, processes, and practices play a pre-eminent role because not only do they affect HR practices, they also provide a socializing context for organizational decision makers’ levels of hostile and benevolent sexism. Although we portray gender inequality as a self-reinforcing system that can perpetuate discrimination, important levers for reducing discrimination are identified.

Introduction

The workplace has sometimes been referred to as an inhospitable place for women due to the multiple forms of gender inequalities present (e.g., Abrams, 1991 ). Some examples of how workplace discrimination negatively affects women’s earnings and opportunities are the gender wage gap (e.g., Peterson and Morgan, 1995 ), the dearth of women in leadership ( Eagly and Carli, 2007 ), and the longer time required for women (vs. men) to advance in their careers ( Blau and DeVaro, 2007 ). In other words, workplace discrimination contributes to women’s lower socio-economic status. Importantly, such discrimination against women largely can be attributed to human resources (HR) policies and HR-related decision-making. Furthermore, when employees interact with organizational decision makers during HR practices, or when they are told the outcomes of HR-related decisions, they may experience personal discrimination in the form of sexist comments. Both the objective disadvantages of lower pay, status, and opportunities at work, and the subjective experiences of being stigmatized, affect women’s psychological and physical stress, mental and physical health ( Goldenhar et al., 1998 ; Adler et al., 2000 ; Schmader et al., 2008 ; Borrel et al., 2010 ),job satisfaction and organizational commitment ( Hicks-Clarke and Iles, 2000 ), and ultimately, their performance ( Cohen-Charash and Spector, 2001 ).

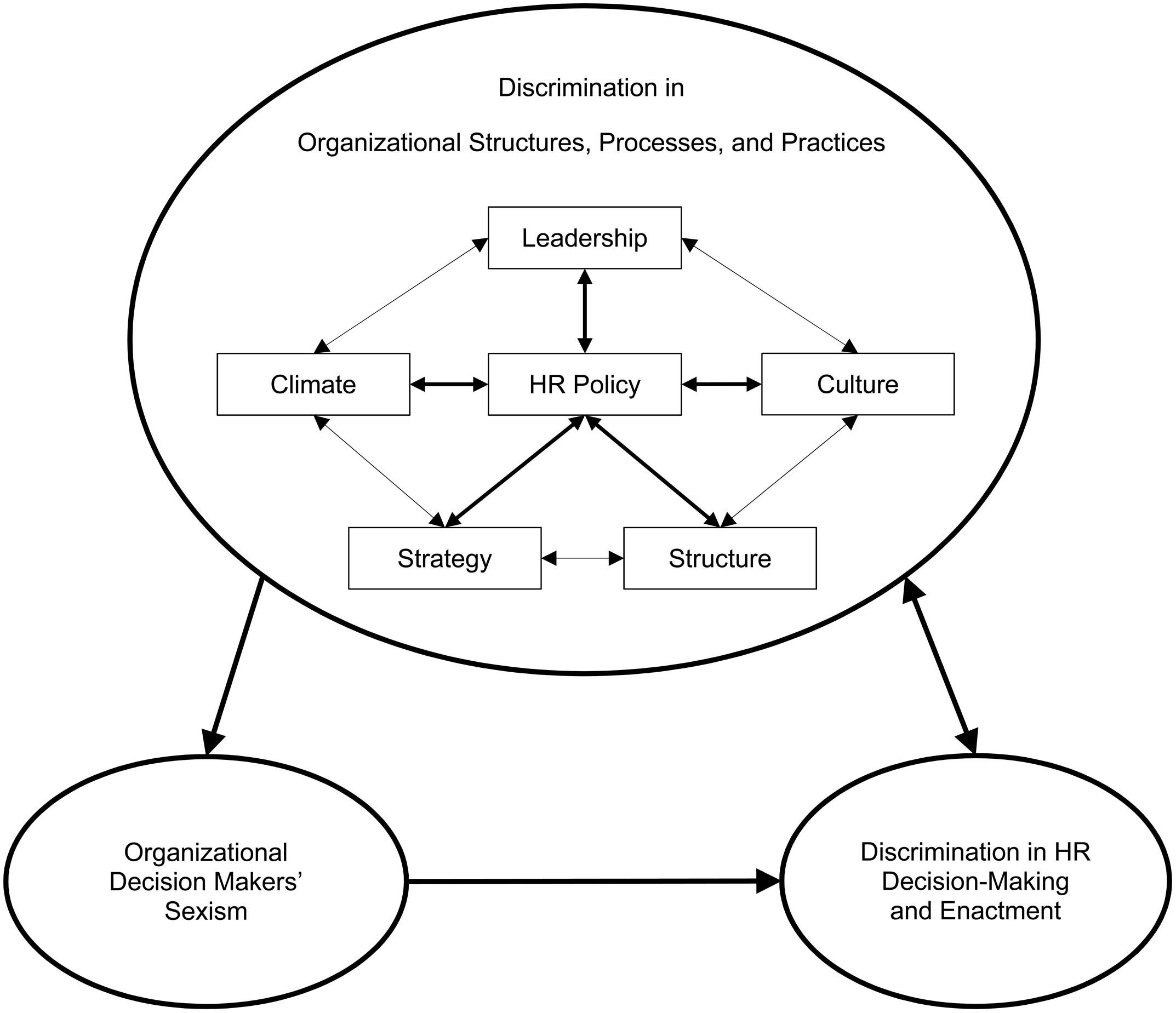

Within this paper, we delineate the nature of discrimination within HR policies, decisions, and their enactment, as well as explore the causes of such discrimination in the workplace. Our model is shown in Figure 1 . In the Section “Discrimination in HR Related Practices: HR Policy, Decisions, and their Enactment,” we explain the distinction between HR policy, HR-related decision-making, and HR enactment and their relations to each other. Gender inequalities in HR policy are a form of institutional discrimination. We review evidence of institutional discrimination against women within HR policies set out to determine employee selection, performance evaluations, and promotions. In contrast, discrimination in HR-related decisions and their enactment can result from organizational decision makers’ biased responses: it is a form of personal discrimination. Finally, we provide evidence of personal discrimination against women by organizational decision makers in HR-related decision-making and in the enactment of HR policies.

FIGURE 1. A model of the root causes of gender discrimination in HR policies, decision-making, and enactment.

In the Section “The Effect of Organizational Structures, Processes, and Practices on HR Practices,” we focus on the link between institutional discrimination in organizational structures, processes, and practices that can lead to personal discrimination in HR practices (see Figure 1 ). Inspired by the work of Gelfand et al. (2007) , we propose that organizational structures, processes, and practices (i.e., leadership, structure, strategy, culture, climate, and HR policy) are interrelated and may contribute to discrimination. Accordingly, gender inequalities in each element can affect the others, creating a self-reinforcing system that can perpetuate institutional discrimination throughout the organization and that can lead to discrimination in HR policies, decision-making, and enactment. We also propose that these relations between gender inequalities in the organizational structures, processes, and practices and discrimination in HR practices can be bidirectional (see Figure 1 ). Thus, we also review how HR practices can contribute to gender inequalities in organizational structures, processes, and practices.

In the Section “The Effect of Hostile and Benevolent Sexism on How Organizational Decision Makers’ Conduct HR Practices,” we delineate the link between organizational decision makers’ levels of sexism and their likelihood of making gender-biased HR-related decisions and/or behaving in a sexist manner when enacting HR policies (e.g., engaging in gender harassment). We focus on two forms of sexist attitudes: hostile and benevolent sexism ( Glick and Fiske, 1996 ). Hostile sexism involves antipathy toward, and negative stereotypes about, agentic women. In contrast, benevolent sexism involves positive but paternalistic views of women as highly communal. Whereas previous research on workplace discrimination has focused on forms of sexism that are hostile in nature, we extend this work by explaining how benevolent sexism, which is more subtle, can also contribute in meaningful yet distinct ways to gender discrimination in HR practices.

In the Section “The Effect of Organizational Structures, Processes, and Practices on Organizational Decision Makers’ Levels of Hostile and Benevolent Sexism,” we describe how institutional discrimination in organizational structures, processes, and practices play a critical role in our model because not only do they affect HR-related decisions and the enactment of HR policies, they also provide a socializing context for organizational decision makers’ levels of hostile and benevolent sexism. In other words, where more institutional discrimination is present, we can expect higher levels of sexism—a third link in our model—which leads to gender bias in HR practices.

In the Section “How to Reduce Gender Discrimination in Organizations,” we discuss how organizations can reduce gender discrimination. We suggest that, to reduce discrimination, organizations should focus on: HR practices, other closely related organizational structures, processes, and practices, and the reduction of organizational decision makers’ level of sexism. Organizations should take such a multifaceted approach because, consistent with our model, gender discrimination is a result of a complex interplay between these factors. Therefore, a focus on only one factor may not be as effective if all the other elements in the model continue to promote gender inequality.

The model we propose for understanding gender inequalities at work is, of course, limited and not intended to be exhaustive. First, we only focus on women’s experience of discrimination. Although men also face discrimination, the focus of this paper is on women because they are more often targets ( Branscombe, 1998 ; Schmitt et al., 2002 ; McLaughlin et al., 2012 ) and discrimination is more psychologically damaging for women than for men ( Barling et al., 1996 ; Schmitt et al., 2002 ). Furthermore, we draw on research from Western, individualistic countries conducted between the mid-1980s to the mid-2010s that might not generalize to other countries or time frames. In addition, this model derives from research that has been conducted primarily in sectors dominated by men. This is because gender discrimination ( Mansfield et al., 1991 ; Welle and Heilman, 2005 ) and harassment ( Mansfield et al., 1991 ; Berdhal, 2007 ) against women occur more in environments dominated by men. Now that we have outlined the sections of the paper and our model, we now turn to delineating how gender discrimination in the workplace can be largely attributed to HR practices.

Discrimination in HR Related Practices: HR Policy, Decisions, and their Enactment

In this section, we explore the nature of gender discrimination in HR practices, which involves HR policies, HR-related decision-making, and their enactment by organizational decision makers. HR is a system of organizational practices aimed at managing employees and ensuring that they are accomplishing organizational goals ( Wright et al., 1994 ). HR functions include: selection, performance evaluation, leadership succession, and training. Depending on the size and history of the organization, HR systems can range from those that are well structured and supported by an entire department, led by HR specialists, to haphazard sets of policies and procedures enacted by managers and supervisors without formal training. HR practices are critically important because they determine the access employees have to valued reward and outcomes within an organization, and can also influence their treatment within an organization ( Levitin et al., 1971 ).

Human resource practices can be broken down into formal HR policy, HR-related decision-making, and the enactment of HR policies and decisions. HR policy codifies practices for personnel functions, performance evaluations, employee relations, and resource planning ( Wright et al., 1994 ). HR-related decision-making occurs when organizational decision makers (i.e., managers, supervisors, or HR personnel) employ HR policy to determine how it will be applied to a particular situation and individual. The enactment of HR involves the personal interactions between organizational decision makers and job candidates or employees when HR policies are applied. Whereas HR policy can reflect institutional discrimination, HR-related decision-making and enactment can reflect personal discrimination by organizational decision makers.

Institutional Discrimination in HR Policy

Human resource policies that are inherently biased against a group of people, regardless of their job-related knowledge, skills, abilities, and performance can be termed institutional discrimination. Institutional discrimination against women can occur in each type of HR policy from the recruitment and selection of an individual into an organization, through his/her role assignments, training, pay, performance evaluations, promotion, and termination. For instance, if women are under-represented in a particular educational program or a particular job type and those credentials or previous job experience are required to be considered for selection, women are being systematically, albeit perhaps not intentionally, discriminated against. In another example, there is gender discrimination if a test is used in the selection battery for which greater gender differences emerge, than those that emerge for job performance ratings ( Hough et al., 2001 ). Thus, institutional discrimination can be present within various aspects of HR selection policy, and can negatively affect women’s work outcomes.

Institutional discrimination against women also occurs in performance evaluations that are used to determine organizational rewards (e.g., compensation), opportunities (e.g., promotion, role assignments), and punishments (e.g., termination). Gender discrimination can be formalized into HR policy if criteria used by organizational decision makers to evaluate job performance systematically favor men over women. For instance, “face time” is a key performance metric that rewards employees who are at the office more than those who are not. Given that women are still the primary caregivers ( Acker, 1990 ; Fuegen et al., 2004 ), women use flexible work arrangements more often than men and, consequently, face career penalties because they score lower on face time ( Glass, 2004 ). Thus, biased criteria in performance evaluation policies can contribute to gender discrimination.

Human resource policies surrounding promotions and opportunities for advancement are another area of concern. In organizations with more formal job ladders that are used to dictate and constrain workers’ promotion opportunities, women are less likely to advance ( Perry et al., 1994 ). This occurs because job ladders tend to be divided by gender, and as such, gender job segregation that is seen at entry-level positions will be strengthened as employees move up their specific ladder with no opportunity to cross into other lines of advancement. Thus, women will lack particular job experiences that are not available within their specific job ladders, making them unqualified for advancement ( De Pater et al., 2010 ).

In sum, institutional discrimination can be present within HR policies set out to determine employee selection, performance evaluations, and promotions. These policies can have significant effects on women’s careers. However, HR policy can only be used to guide HR-related decision-making. In reality, it is organizational decision-makers, that is, managers, supervisors, HR personnel who, guided by policy, must evaluate job candidates or employees and decide how policy will be applied to individuals.

Personal Discrimination in HR-Related Decision-Making

The practice of HR-related decision-making involves social cognition in which others’ competence, potential, and deservingness are assessed by organizational decision makers. Thus, like all forms of social cognition, HR-related decision-making is open to personal biases. HR-related decisions are critically important because they determine women’s pay and opportunities at work (e.g., promotions, training opportunities). Personal discrimination against women by organizational decision makers can occur in each stage of HR-related decision-making regarding recruitment and selection, role assignments, training opportunities, pay, performance evaluation, promotion, and termination.

Studies with varying methodologies show that women face personal discrimination when going through the selection process (e.g., Goldberg, 1968 ; Rosen and Jerdee, 1974 ). Meta-analyses reveal that, when being considered for male-typed (i.e., male dominated, believed-to-be-for-men) jobs, female candidates are evaluated more negatively and recommended for employment less often by study participants, compared with matched male candidates (e.g., Hunter et al., 1982 ; Tosi and Einbender, 1985 ; Olian et al., 1988 ; Davison and Burke, 2000 ). For example, in audit studies, which involve sending ostensibly real applications for job openings while varying the gender of the applicant, female applicants are less likely to be interviewed or called back, compared with male applicants (e.g., McIntyre et al., 1980 ; Firth, 1982 ). In a recent study, male and female biology, chemistry, and physics professors rated an undergraduate science student for a laboratory manager position ( Moss-Racusin et al., 2012 ). The male applicant was rated as significantly more competent and hireable, offered a higher starting salary (about $4000), and offered more career mentoring than the female applicant was. In summary, women face a distinct disadvantage when being considered for male-typed jobs.

There is ample evidence that women experience biased performance evaluations on male-typed tasks. A meta-analysis of experimental studies reveals that women in leadership positions receive lower performance evaluations than matched men; this is amplified when women act in a stereotypically masculine, that is, agentic fashion ( Eagly et al., 1992 ). Further, in masculine domains, women are held to a higher standard of performance than men are. For example, in a study of military cadets, men and women gave their peers lower ratings if they were women, despite having objectively equal qualifications to men ( Boldry et al., 2001 ). Finally, women are evaluated more poorly in situations that involve complex problem solving; in these situations, people are skeptical regarding women’s expertise and discredit expert women’s opinions but give expert men the benefit of the doubt ( Thomas-Hunt and Phillips, 2004 ).

Sometimes particular types of women are more likely to be discriminated against in selection and performance evaluation decisions. Specifically, agentic women, that is, those who behave in an assertive, task-oriented fashion, are rated as less likeable and less hireable than comparable agentic male applicants ( Heilman and Okimoto, 2007 ; Rudman and Phelan, 2008 ; Rudman et al., 2012 ). In addition, there is evidence of discrimination against pregnant women when they apply for jobs ( Hebl et al., 2007 ; Morgan et al., 2013 ). Further, women who are mothers are recommended for promotion less than women who are not mothers or men with or without children ( Heilman and Okimoto, 2008 ). Why might people discriminate specifically against agentic women and pregnant women or mothers, who are seemingly very different? The stereotype content model, accounts for how agentic women, who are perceived to be high in competence and low in warmth, will be discriminated against because of feelings of competition; whereas, pregnant women and mothers, who are seen as low in competence, but high in warmth, will be discriminated against because of a perceived lack of deservingness ( Fiske et al., 1999 , 2002 ; Cuddy et al., 2004 ). Taken together, research has uncovered that different forms of bias toward specific subtypes of women have the same overall effect—bias in selection and performance evaluation decisions.

Women are also likely to receive fewer opportunities at work, compared with men, resulting in their under-representation at higher levels of management and leadership within organizations ( Martell et al., 1996 ; Eagly and Carli, 2007 ). Managers give women fewer challenging roles and fewer training opportunities, compared with men ( King et al., 2012 ; Glick, 2013 ). For instance, female managers ( Lyness and Thompson, 1997 ) and midlevel workers ( De Pater et al., 2010 ) have less access to high-level responsibilities and challenges that are precursors to promotion. Further, men are more likely to be given key leadership assignments in male-dominated fields and in female-dominated fields (e.g., Maume, 1999 ; De Pater et al., 2010 ). This is detrimental given that challenging roles, especially developmental ones, help employees gain important skills needed to excel in their careers ( Spreitzer et al., 1997 ).

Furthermore, managers rate women as having less promotion potential than men ( Roth et al., 2012 ). Given the same level of qualifications, managers are less likely to grant promotions to women, compared with men ( Lazear and Rosen, 1990 ). Thus, men have a faster ascent in organizational hierarchies than women ( Cox and Harquail, 1991 ; Stroh et al., 1992 ; Blau and DeVaro, 2007 ). Even minimal amounts of gender discrimination in promotion decisions for a particular job or level can have large, cumulative effects given the pyramid structure of most hierarchical organizations ( Martell et al., 1996 ; Baxter and Wright, 2000 ). Therefore, discrimination by organizational decision makers results in the under-promotion of women.

Finally, women are underpaid, compared with men. In a comprehensive US study using data from 1983 to 2000, after controlling for human capital factors that could affect wages (e.g., education level, work experience), the researchers found that women were paid 22% less than men ( U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2003 ). Further, within any given occupation, men typically have higher wages than women; this “within-occupation” wage gap is especially prominent in more highly paid occupations ( U.S. Census Bureau, 2007 ). In a study of over 2000 managers, women were compensated less than men were, even after controlling for a number of human capital factors ( Ostroff and Atwater, 2003 ). Experimental work suggests that personal biases by organizational decision makers contribute to the gender wage gap. When participants are asked to determine starting salaries for matched candidates that differ by gender, they pay men more (e.g., Steinpreis et al., 1999 ; Moss-Racusin et al., 2012 ). Such biases are consequential because starting salaries determine life-time earnings ( Gerhart and Rynes, 1991 ). In experimental studies, when participants evaluate a man vs. a woman who is matched on job performance, they choose to compensate men more ( Marini, 1989 ; Durden and Gaynor, 1998 ; Lips, 2003 ). Therefore, discrimination in HR-related decision-making by organizational decision makers can contribute to women being paid less than men are.

Taken together, we have shown that there is discrimination against women in decision-making related to HR. These biases from organizational decision makers can occur in each stage of HR-related decision-making and these biased HR decisions have been shown to negatively affect women’s pay and opportunities at work. In the next section, we review how biased HR practices are enacted, which can involve gender harassment.

Personal Discrimination in HR Enactment