Dissertations and research projects

- Book a session

- Planning your research

Developing a theoretical framework

Reflecting on your position, extended literature reviews, presenting qualitative data.

- Quantitative research

- Writing up your research project

- e-learning and books

- SkillsCheck This link opens in a new window

- ⬅ Back to Skills Centre This link opens in a new window

- Review this resource

What is a theoretical framework?

Developing a theoretical framework for your dissertation is one of the key elements of a qualitative research project. Through writing your literature review, you are likely to have identified either a problem that need ‘fixing’ or a gap that your research may begin to fill.

The theoretical framework is your toolbox . In the toolbox are your handy tools: a set of theories, concepts, ideas and hypotheses that you will use to build a solution to the research problem or gap you have identified.

The methodology is the instruction manual: the procedure and steps you have taken, using your chosen tools, to tackle the research problem.

Why do I need a theoretical framework?

Developing a theoretical framework shows that you have thought critically about the different ways to approach your topic, and that you have made a well-reasoned and evidenced decision about which approach will work best. theoretical frameworks are also necessary for solving complex problems or issues from the literature, showing that you have the skills to think creatively and improvise to answer your research questions. they also allow researchers to establish new theories and approaches, that future research may go on to develop., how do i create a theoretical framework for my dissertation.

First, select your tools. You are likely to need a variety of tools in qualitative research – different theories, models or concepts – to help you tackle different parts of your research question.

When deciding what tools would be best for the job of answering your research questions or problem, explore what existing research in your area has used. You may find that there is a ‘standard toolbox’ for qualitative research in your field that you can borrow from or apply to your own research.

You will need to justify why your chosen tools are best for the job of answering your research questions, at what stage they are most relevant, and how they relate to each other. Some theories or models will neatly fit together and appear in the toolboxes of other researchers. However, you may wish to incorporate a model or idea that is not typical for your research area – the ‘odd one out’ in your toolbox. If this is the case, make sure you justify and account for why it is useful to you, and look for ways that it can be used in partnership with the other tools you are using.

You should also be honest about limitations, or where you need to improvise (for example, if the ‘right’ tool or approach doesn’t exist in your area).

This video from the Skills Centre includes an overview and example of how you might create a theoretical framework for your dissertation:

How do I choose the 'right' approach?

When designing your framework and choosing what to include, it can often be difficult to know if you’ve chosen the ‘right’ approach for your research questions. One way to check this is to look for consistency between your objectives, the literature in your framework, and your overall ethos for the research. This means ensuring that the literature you have used not only contributes to answering your research objectives, but that you also use theories and models that are true to your beliefs as a researcher.

Reflecting on your values and your overall ambition for the project can be a helpful step in making these decisions, as it can help you to fully connect your methodology and methods to your research aims.

Should I reflect on my position as a researcher?

If you feel your position as a researcher has influenced your choice of methods or procedure in any way, the methodology is a good place to reflect on this. Positionality acknowledges that no researcher is entirely objective: we are all, to some extent, influenced by prior learning, experiences, knowledge, and personal biases. This is particularly true in qualitative research or practice-based research, where the student is acting as a researcher in their own workplace, where they are otherwise considered a practitioner/professional. It's also important to reflect on your positionality if you belong to the same community as your participants where this is the grounds for their involvement in the research (ie. you are a mature student interviewing other mature learners about their experences in higher education).

The following questions can help you to reflect on your positionality and gauge whether this is an important section to include in your dissertation (for some people, this section isn’t necessary or relevant):

- How might my personal history influence how I approach the topic?

- How am I positioned in relation to this knowledge? Am I being influenced by prior learning or knowledge from outside of this course?

- How does my gender/social class/ ethnicity/ culture influence my positioning in relation to this topic?

- Do I share any attributes with my participants? Are we part of a s hared community? How might this have influenced our relationship and my role in interviews/observations?

- Am I invested in the outcomes on a personal level? Who is this research for and who will feel the benefits?

One option for qualitative projects is to write an extended literature review. This type of project does not require you to collect any new data. Instead, you should focus on synthesising a broad range of literature to offer a new perspective on a research problem or question.

The main difference between an extended literature review and a dissertation where primary data is collected, is in the presentation of the methodology, results and discussion sections. This is because extended literature reviews do not actively involve participants or primary data collection, so there is no need to outline a procedure for data collection (the methodology) or to present and interpret ‘data’ (in the form of interview transcripts, numerical data, observations etc.) You will have much more freedom to decide which sections of the dissertation should be combined, and whether new chapters or sections should be added.

Here is an overview of a common structure for an extended literature review:

Introduction

- Provide background information and context to set the ‘backdrop’ for your project.

- Explain the value and relevance of your research in this context. Outline what do you hope to contribute with your dissertation.

- Clarify a specific area of focus.

- Introduce your research aims (or problem) and objectives.

Literature review

You will need to write a short, overview literature review to introduce the main theories, concepts and key research areas that you will explore in your dissertation. This set of texts – which may be theoretical, research-based, practice-based or policies – form your theoretical framework. In other words, by bringing these texts together in the literature review, you are creating a lens that you can then apply to more focused examples or scenarios in your discussion chapters.

Methodology

As you will not be collecting primary data, your methodology will be quite different from a typical dissertation. You will need to set out the process and procedure you used to find and narrow down your literature. This is also known as a search strategy.

Including your search strategy

A search strategy explains how you have narrowed down your literature to identify key studies and areas of focus. This often takes the form of a search strategy table, included as an appendix at the end of the dissertation. If included, this section takes the place of the traditional 'methodology' section.

If you choose to include a search strategy table, you should also give an overview of your reading process in the main body of the dissertation. Think of this as a chronology of the practical steps you took and your justification for doing so at each stage, such as:

- Your key terms, alternatives and synonyms, and any terms that you chose to exclude.

- Your choice and combination of databases;

- Your inclusion/exclusion criteria, when they were applied and why. This includes filters such as language of publication, date, and country of origin;

- You should also explain which terms you combined to form search phrases and your use of Boolean searching (AND, OR, NOT);

- Your use of citation searching (selecting articles from the bibliography of a chosen journal article to further your search).

- Your use of any search models, such as PICO and SPIDER to help shape your approach.

- Search strategy template A simple template for recording your literature searching. This can be included as an appendix to show your search strategy.

The discussion section of an extended literature review is the most flexible in terms of structure. Think of this section as a series of short case studies or ‘windows’ on your research. In this section you will apply the theoretical framework you formed in the literature review – a combination of theories, models and ideas that explain your approach to the topic – to a series of different examples and scenarios. These are usually presented as separate discussion ‘chapters’ in the dissertation, in an order that you feel best fits your argument.

Think about an order for these discussion sections or chapters that helps to tell the story of your research. One common approach is to structure these sections by common themes or concepts that help to draw your sources together. You might also opt for a chronological structure if your dissertation aims to show change or development over time. Another option is to deliberately show where there is a lack of chronology or narrative across your case studies, by ordering them in a fragmentary order! You will be able to reflect upon the structure of these chapters elsewhere in the dissertation, explaining and defending your decision in the methodology and conclusion.

A summary of your key findings – what you have concluded from your research, and how far you have been able to successfully answer your research questions.

- Recommendations – for improvements to your own study, for future research in the area, and for your field more widely.

- Emphasise your contributions to knowledge and what you have achieved.

Alternative structure

Depending on your research aims, and whether you are working with a case-study type approach (where each section of the dissertation considers a different example or concept through the lens established in your literature review), you might opt for one of the following structures:

Splitting the literature review across different chapters:

This structure allows you to pull apart the traditional literature review, introducing it little by little with each of your themed chapters. This approach works well for dissertations that attempt to show change or difference over time, as the relevant literature for that section or period can be introduced gradually to the reader.

Whichever structure you opt for, remember to explain and justify your approach. A marker will be interested in why you decided on your chosen structure, what it allows you to achieve/brings to the project and what alternatives you considered and rejected in the planning process. Here are some example sentence starters:

In qualitative studies, your results are often presented alongside the discussion, as it is difficult to include this data in a meaningful way without explanation and interpretation. In the dsicussion section, aim to structure your work thematically, moving through the key concepts or ideas that have emerged from your qualitative data. Use extracts from your data collection - interviews, focus groups, observations - to illustrate where these themes are most prominent, and refer back to the sources from your literature review to help draw conclusions.

Here's an example of how your data could be presented in paragraph format in this section:

Example from 'Reporting and discussing your findings ', Monash University .

- << Previous: Planning your research

- Next: Quantitative research >>

- Last Updated: Apr 17, 2024 1:52 PM

- URL: https://libguides.shu.ac.uk/researchprojects

Chapter 2. Research Design

Getting started.

When I teach undergraduates qualitative research methods, the final product of the course is a “research proposal” that incorporates all they have learned and enlists the knowledge they have learned about qualitative research methods in an original design that addresses a particular research question. I highly recommend you think about designing your own research study as you progress through this textbook. Even if you don’t have a study in mind yet, it can be a helpful exercise as you progress through the course. But how to start? How can one design a research study before they even know what research looks like? This chapter will serve as a brief overview of the research design process to orient you to what will be coming in later chapters. Think of it as a “skeleton” of what you will read in more detail in later chapters. Ideally, you will read this chapter both now (in sequence) and later during your reading of the remainder of the text. Do not worry if you have questions the first time you read this chapter. Many things will become clearer as the text advances and as you gain a deeper understanding of all the components of good qualitative research. This is just a preliminary map to get you on the right road.

Research Design Steps

Before you even get started, you will need to have a broad topic of interest in mind. [1] . In my experience, students can confuse this broad topic with the actual research question, so it is important to clearly distinguish the two. And the place to start is the broad topic. It might be, as was the case with me, working-class college students. But what about working-class college students? What’s it like to be one? Why are there so few compared to others? How do colleges assist (or fail to assist) them? What interested me was something I could barely articulate at first and went something like this: “Why was it so difficult and lonely to be me?” And by extension, “Did others share this experience?”

Once you have a general topic, reflect on why this is important to you. Sometimes we connect with a topic and we don’t really know why. Even if you are not willing to share the real underlying reason you are interested in a topic, it is important that you know the deeper reasons that motivate you. Otherwise, it is quite possible that at some point during the research, you will find yourself turned around facing the wrong direction. I have seen it happen many times. The reason is that the research question is not the same thing as the general topic of interest, and if you don’t know the reasons for your interest, you are likely to design a study answering a research question that is beside the point—to you, at least. And this means you will be much less motivated to carry your research to completion.

Researcher Note

Why do you employ qualitative research methods in your area of study? What are the advantages of qualitative research methods for studying mentorship?

Qualitative research methods are a huge opportunity to increase access, equity, inclusion, and social justice. Qualitative research allows us to engage and examine the uniquenesses/nuances within minoritized and dominant identities and our experiences with these identities. Qualitative research allows us to explore a specific topic, and through that exploration, we can link history to experiences and look for patterns or offer up a unique phenomenon. There’s such beauty in being able to tell a particular story, and qualitative research is a great mode for that! For our work, we examined the relationships we typically use the term mentorship for but didn’t feel that was quite the right word. Qualitative research allowed us to pick apart what we did and how we engaged in our relationships, which then allowed us to more accurately describe what was unique about our mentorship relationships, which we ultimately named liberationships ( McAloney and Long 2021) . Qualitative research gave us the means to explore, process, and name our experiences; what a powerful tool!

How do you come up with ideas for what to study (and how to study it)? Where did you get the idea for studying mentorship?

Coming up with ideas for research, for me, is kind of like Googling a question I have, not finding enough information, and then deciding to dig a little deeper to get the answer. The idea to study mentorship actually came up in conversation with my mentorship triad. We were talking in one of our meetings about our relationship—kind of meta, huh? We discussed how we felt that mentorship was not quite the right term for the relationships we had built. One of us asked what was different about our relationships and mentorship. This all happened when I was taking an ethnography course. During the next session of class, we were discussing auto- and duoethnography, and it hit me—let’s explore our version of mentorship, which we later went on to name liberationships ( McAloney and Long 2021 ). The idea and questions came out of being curious and wanting to find an answer. As I continue to research, I see opportunities in questions I have about my work or during conversations that, in our search for answers, end up exposing gaps in the literature. If I can’t find the answer already out there, I can study it.

—Kim McAloney, PhD, College Student Services Administration Ecampus coordinator and instructor

When you have a better idea of why you are interested in what it is that interests you, you may be surprised to learn that the obvious approaches to the topic are not the only ones. For example, let’s say you think you are interested in preserving coastal wildlife. And as a social scientist, you are interested in policies and practices that affect the long-term viability of coastal wildlife, especially around fishing communities. It would be natural then to consider designing a research study around fishing communities and how they manage their ecosystems. But when you really think about it, you realize that what interests you the most is how people whose livelihoods depend on a particular resource act in ways that deplete that resource. Or, even deeper, you contemplate the puzzle, “How do people justify actions that damage their surroundings?” Now, there are many ways to design a study that gets at that broader question, and not all of them are about fishing communities, although that is certainly one way to go. Maybe you could design an interview-based study that includes and compares loggers, fishers, and desert golfers (those who golf in arid lands that require a great deal of wasteful irrigation). Or design a case study around one particular example where resources were completely used up by a community. Without knowing what it is you are really interested in, what motivates your interest in a surface phenomenon, you are unlikely to come up with the appropriate research design.

These first stages of research design are often the most difficult, but have patience . Taking the time to consider why you are going to go through a lot of trouble to get answers will prevent a lot of wasted energy in the future.

There are distinct reasons for pursuing particular research questions, and it is helpful to distinguish between them. First, you may be personally motivated. This is probably the most important and the most often overlooked. What is it about the social world that sparks your curiosity? What bothers you? What answers do you need in order to keep living? For me, I knew I needed to get a handle on what higher education was for before I kept going at it. I needed to understand why I felt so different from my peers and whether this whole “higher education” thing was “for the likes of me” before I could complete my degree. That is the personal motivation question. Your personal motivation might also be political in nature, in that you want to change the world in a particular way. It’s all right to acknowledge this. In fact, it is better to acknowledge it than to hide it.

There are also academic and professional motivations for a particular study. If you are an absolute beginner, these may be difficult to find. We’ll talk more about this when we discuss reviewing the literature. Simply put, you are probably not the only person in the world to have thought about this question or issue and those related to it. So how does your interest area fit into what others have studied? Perhaps there is a good study out there of fishing communities, but no one has quite asked the “justification” question. You are motivated to address this to “fill the gap” in our collective knowledge. And maybe you are really not at all sure of what interests you, but you do know that [insert your topic] interests a lot of people, so you would like to work in this area too. You want to be involved in the academic conversation. That is a professional motivation and a very important one to articulate.

Practical and strategic motivations are a third kind. Perhaps you want to encourage people to take better care of the natural resources around them. If this is also part of your motivation, you will want to design your research project in a way that might have an impact on how people behave in the future. There are many ways to do this, one of which is using qualitative research methods rather than quantitative research methods, as the findings of qualitative research are often easier to communicate to a broader audience than the results of quantitative research. You might even be able to engage the community you are studying in the collecting and analyzing of data, something taboo in quantitative research but actively embraced and encouraged by qualitative researchers. But there are other practical reasons, such as getting “done” with your research in a certain amount of time or having access (or no access) to certain information. There is nothing wrong with considering constraints and opportunities when designing your study. Or maybe one of the practical or strategic goals is about learning competence in this area so that you can demonstrate the ability to conduct interviews and focus groups with future employers. Keeping that in mind will help shape your study and prevent you from getting sidetracked using a technique that you are less invested in learning about.

STOP HERE for a moment

I recommend you write a paragraph (at least) explaining your aims and goals. Include a sentence about each of the following: personal/political goals, practical or professional/academic goals, and practical/strategic goals. Think through how all of the goals are related and can be achieved by this particular research study . If they can’t, have a rethink. Perhaps this is not the best way to go about it.

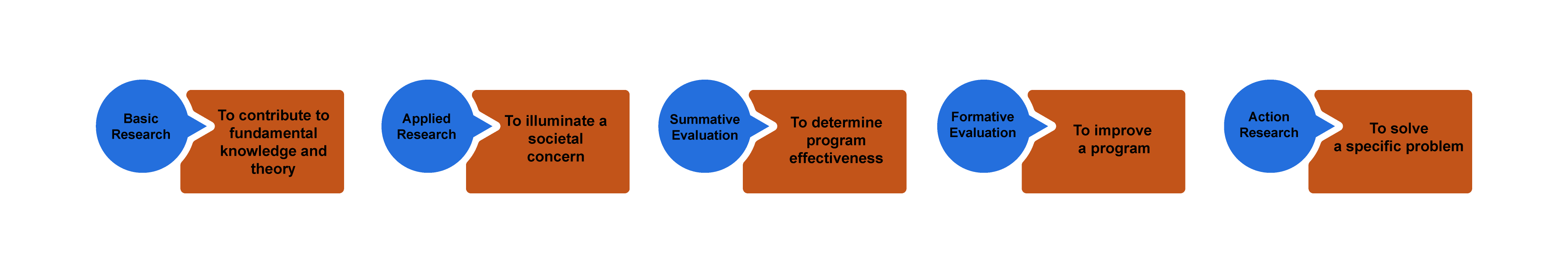

You will also want to be clear about the purpose of your study. “Wait, didn’t we just do this?” you might ask. No! Your goals are not the same as the purpose of the study, although they are related. You can think about purpose lying on a continuum from “ theory ” to “action” (figure 2.1). Sometimes you are doing research to discover new knowledge about the world, while other times you are doing a study because you want to measure an impact or make a difference in the world.

Basic research involves research that is done for the sake of “pure” knowledge—that is, knowledge that, at least at this moment in time, may not have any apparent use or application. Often, and this is very important, knowledge of this kind is later found to be extremely helpful in solving problems. So one way of thinking about basic research is that it is knowledge for which no use is yet known but will probably one day prove to be extremely useful. If you are doing basic research, you do not need to argue its usefulness, as the whole point is that we just don’t know yet what this might be.

Researchers engaged in basic research want to understand how the world operates. They are interested in investigating a phenomenon to get at the nature of reality with regard to that phenomenon. The basic researcher’s purpose is to understand and explain ( Patton 2002:215 ).

Basic research is interested in generating and testing hypotheses about how the world works. Grounded Theory is one approach to qualitative research methods that exemplifies basic research (see chapter 4). Most academic journal articles publish basic research findings. If you are working in academia (e.g., writing your dissertation), the default expectation is that you are conducting basic research.

Applied research in the social sciences is research that addresses human and social problems. Unlike basic research, the researcher has expectations that the research will help contribute to resolving a problem, if only by identifying its contours, history, or context. From my experience, most students have this as their baseline assumption about research. Why do a study if not to make things better? But this is a common mistake. Students and their committee members are often working with default assumptions here—the former thinking about applied research as their purpose, the latter thinking about basic research: “The purpose of applied research is to contribute knowledge that will help people to understand the nature of a problem in order to intervene, thereby allowing human beings to more effectively control their environment. While in basic research the source of questions is the tradition within a scholarly discipline, in applied research the source of questions is in the problems and concerns experienced by people and by policymakers” ( Patton 2002:217 ).

Applied research is less geared toward theory in two ways. First, its questions do not derive from previous literature. For this reason, applied research studies have much more limited literature reviews than those found in basic research (although they make up for this by having much more “background” about the problem). Second, it does not generate theory in the same way as basic research does. The findings of an applied research project may not be generalizable beyond the boundaries of this particular problem or context. The findings are more limited. They are useful now but may be less useful later. This is why basic research remains the default “gold standard” of academic research.

Evaluation research is research that is designed to evaluate or test the effectiveness of specific solutions and programs addressing specific social problems. We already know the problems, and someone has already come up with solutions. There might be a program, say, for first-generation college students on your campus. Does this program work? Are first-generation students who participate in the program more likely to graduate than those who do not? These are the types of questions addressed by evaluation research. There are two types of research within this broader frame; however, one more action-oriented than the next. In summative evaluation , an overall judgment about the effectiveness of a program or policy is made. Should we continue our first-gen program? Is it a good model for other campuses? Because the purpose of such summative evaluation is to measure success and to determine whether this success is scalable (capable of being generalized beyond the specific case), quantitative data is more often used than qualitative data. In our example, we might have “outcomes” data for thousands of students, and we might run various tests to determine if the better outcomes of those in the program are statistically significant so that we can generalize the findings and recommend similar programs elsewhere. Qualitative data in the form of focus groups or interviews can then be used for illustrative purposes, providing more depth to the quantitative analyses. In contrast, formative evaluation attempts to improve a program or policy (to help “form” or shape its effectiveness). Formative evaluations rely more heavily on qualitative data—case studies, interviews, focus groups. The findings are meant not to generalize beyond the particular but to improve this program. If you are a student seeking to improve your qualitative research skills and you do not care about generating basic research, formative evaluation studies might be an attractive option for you to pursue, as there are always local programs that need evaluation and suggestions for improvement. Again, be very clear about your purpose when talking through your research proposal with your committee.

Action research takes a further step beyond evaluation, even formative evaluation, to being part of the solution itself. This is about as far from basic research as one could get and definitely falls beyond the scope of “science,” as conventionally defined. The distinction between action and research is blurry, the research methods are often in constant flux, and the only “findings” are specific to the problem or case at hand and often are findings about the process of intervention itself. Rather than evaluate a program as a whole, action research often seeks to change and improve some particular aspect that may not be working—maybe there is not enough diversity in an organization or maybe women’s voices are muted during meetings and the organization wonders why and would like to change this. In a further step, participatory action research , those women would become part of the research team, attempting to amplify their voices in the organization through participation in the action research. As action research employs methods that involve people in the process, focus groups are quite common.

If you are working on a thesis or dissertation, chances are your committee will expect you to be contributing to fundamental knowledge and theory ( basic research ). If your interests lie more toward the action end of the continuum, however, it is helpful to talk to your committee about this before you get started. Knowing your purpose in advance will help avoid misunderstandings during the later stages of the research process!

The Research Question

Once you have written your paragraph and clarified your purpose and truly know that this study is the best study for you to be doing right now , you are ready to write and refine your actual research question. Know that research questions are often moving targets in qualitative research, that they can be refined up to the very end of data collection and analysis. But you do have to have a working research question at all stages. This is your “anchor” when you get lost in the data. What are you addressing? What are you looking at and why? Your research question guides you through the thicket. It is common to have a whole host of questions about a phenomenon or case, both at the outset and throughout the study, but you should be able to pare it down to no more than two or three sentences when asked. These sentences should both clarify the intent of the research and explain why this is an important question to answer. More on refining your research question can be found in chapter 4.

Chances are, you will have already done some prior reading before coming up with your interest and your questions, but you may not have conducted a systematic literature review. This is the next crucial stage to be completed before venturing further. You don’t want to start collecting data and then realize that someone has already beaten you to the punch. A review of the literature that is already out there will let you know (1) if others have already done the study you are envisioning; (2) if others have done similar studies, which can help you out; and (3) what ideas or concepts are out there that can help you frame your study and make sense of your findings. More on literature reviews can be found in chapter 9.

In addition to reviewing the literature for similar studies to what you are proposing, it can be extremely helpful to find a study that inspires you. This may have absolutely nothing to do with the topic you are interested in but is written so beautifully or organized so interestingly or otherwise speaks to you in such a way that you want to post it somewhere to remind you of what you want to be doing. You might not understand this in the early stages—why would you find a study that has nothing to do with the one you are doing helpful? But trust me, when you are deep into analysis and writing, having an inspirational model in view can help you push through. If you are motivated to do something that might change the world, you probably have read something somewhere that inspired you. Go back to that original inspiration and read it carefully and see how they managed to convey the passion that you so appreciate.

At this stage, you are still just getting started. There are a lot of things to do before setting forth to collect data! You’ll want to consider and choose a research tradition and a set of data-collection techniques that both help you answer your research question and match all your aims and goals. For example, if you really want to help migrant workers speak for themselves, you might draw on feminist theory and participatory action research models. Chapters 3 and 4 will provide you with more information on epistemologies and approaches.

Next, you have to clarify your “units of analysis.” What is the level at which you are focusing your study? Often, the unit in qualitative research methods is individual people, or “human subjects.” But your units of analysis could just as well be organizations (colleges, hospitals) or programs or even whole nations. Think about what it is you want to be saying at the end of your study—are the insights you are hoping to make about people or about organizations or about something else entirely? A unit of analysis can even be a historical period! Every unit of analysis will call for a different kind of data collection and analysis and will produce different kinds of “findings” at the conclusion of your study. [2]

Regardless of what unit of analysis you select, you will probably have to consider the “human subjects” involved in your research. [3] Who are they? What interactions will you have with them—that is, what kind of data will you be collecting? Before answering these questions, define your population of interest and your research setting. Use your research question to help guide you.

Let’s use an example from a real study. In Geographies of Campus Inequality , Benson and Lee ( 2020 ) list three related research questions: “(1) What are the different ways that first-generation students organize their social, extracurricular, and academic activities at selective and highly selective colleges? (2) how do first-generation students sort themselves and get sorted into these different types of campus lives; and (3) how do these different patterns of campus engagement prepare first-generation students for their post-college lives?” (3).

Note that we are jumping into this a bit late, after Benson and Lee have described previous studies (the literature review) and what is known about first-generation college students and what is not known. They want to know about differences within this group, and they are interested in ones attending certain kinds of colleges because those colleges will be sites where academic and extracurricular pressures compete. That is the context for their three related research questions. What is the population of interest here? First-generation college students . What is the research setting? Selective and highly selective colleges . But a host of questions remain. Which students in the real world, which colleges? What about gender, race, and other identity markers? Will the students be asked questions? Are the students still in college, or will they be asked about what college was like for them? Will they be observed? Will they be shadowed? Will they be surveyed? Will they be asked to keep diaries of their time in college? How many students? How many colleges? For how long will they be observed?

Recommendation

Take a moment and write down suggestions for Benson and Lee before continuing on to what they actually did.

Have you written down your own suggestions? Good. Now let’s compare those with what they actually did. Benson and Lee drew on two sources of data: in-depth interviews with sixty-four first-generation students and survey data from a preexisting national survey of students at twenty-eight selective colleges. Let’s ignore the survey for our purposes here and focus on those interviews. The interviews were conducted between 2014 and 2016 at a single selective college, “Hilltop” (a pseudonym ). They employed a “purposive” sampling strategy to ensure an equal number of male-identifying and female-identifying students as well as equal numbers of White, Black, and Latinx students. Each student was interviewed once. Hilltop is a selective liberal arts college in the northeast that enrolls about three thousand students.

How did your suggestions match up to those actually used by the researchers in this study? It is possible your suggestions were too ambitious? Beginning qualitative researchers can often make that mistake. You want a research design that is both effective (it matches your question and goals) and doable. You will never be able to collect data from your entire population of interest (unless your research question is really so narrow to be relevant to very few people!), so you will need to come up with a good sample. Define the criteria for this sample, as Benson and Lee did when deciding to interview an equal number of students by gender and race categories. Define the criteria for your sample setting too. Hilltop is typical for selective colleges. That was a research choice made by Benson and Lee. For more on sampling and sampling choices, see chapter 5.

Benson and Lee chose to employ interviews. If you also would like to include interviews, you have to think about what will be asked in them. Most interview-based research involves an interview guide, a set of questions or question areas that will be asked of each participant. The research question helps you create a relevant interview guide. You want to ask questions whose answers will provide insight into your research question. Again, your research question is the anchor you will continually come back to as you plan for and conduct your study. It may be that once you begin interviewing, you find that people are telling you something totally unexpected, and this makes you rethink your research question. That is fine. Then you have a new anchor. But you always have an anchor. More on interviewing can be found in chapter 11.

Let’s imagine Benson and Lee also observed college students as they went about doing the things college students do, both in the classroom and in the clubs and social activities in which they participate. They would have needed a plan for this. Would they sit in on classes? Which ones and how many? Would they attend club meetings and sports events? Which ones and how many? Would they participate themselves? How would they record their observations? More on observation techniques can be found in both chapters 13 and 14.

At this point, the design is almost complete. You know why you are doing this study, you have a clear research question to guide you, you have identified your population of interest and research setting, and you have a reasonable sample of each. You also have put together a plan for data collection, which might include drafting an interview guide or making plans for observations. And so you know exactly what you will be doing for the next several months (or years!). To put the project into action, there are a few more things necessary before actually going into the field.

First, you will need to make sure you have any necessary supplies, including recording technology. These days, many researchers use their phones to record interviews. Second, you will need to draft a few documents for your participants. These include informed consent forms and recruiting materials, such as posters or email texts, that explain what this study is in clear language. Third, you will draft a research protocol to submit to your institutional review board (IRB) ; this research protocol will include the interview guide (if you are using one), the consent form template, and all examples of recruiting material. Depending on your institution and the details of your study design, it may take weeks or even, in some unfortunate cases, months before you secure IRB approval. Make sure you plan on this time in your project timeline. While you wait, you can continue to review the literature and possibly begin drafting a section on the literature review for your eventual presentation/publication. More on IRB procedures can be found in chapter 8 and more general ethical considerations in chapter 7.

Once you have approval, you can begin!

Research Design Checklist

Before data collection begins, do the following:

- Write a paragraph explaining your aims and goals (personal/political, practical/strategic, professional/academic).

- Define your research question; write two to three sentences that clarify the intent of the research and why this is an important question to answer.

- Review the literature for similar studies that address your research question or similar research questions; think laterally about some literature that might be helpful or illuminating but is not exactly about the same topic.

- Find a written study that inspires you—it may or may not be on the research question you have chosen.

- Consider and choose a research tradition and set of data-collection techniques that (1) help answer your research question and (2) match your aims and goals.

- Define your population of interest and your research setting.

- Define the criteria for your sample (How many? Why these? How will you find them, gain access, and acquire consent?).

- If you are conducting interviews, draft an interview guide.

- If you are making observations, create a plan for observations (sites, times, recording, access).

- Acquire any necessary technology (recording devices/software).

- Draft consent forms that clearly identify the research focus and selection process.

- Create recruiting materials (posters, email, texts).

- Apply for IRB approval (proposal plus consent form plus recruiting materials).

- Block out time for collecting data.

- At the end of the chapter, you will find a " Research Design Checklist " that summarizes the main recommendations made here ↵

- For example, if your focus is society and culture , you might collect data through observation or a case study. If your focus is individual lived experience , you are probably going to be interviewing some people. And if your focus is language and communication , you will probably be analyzing text (written or visual). ( Marshall and Rossman 2016:16 ). ↵

- You may not have any "live" human subjects. There are qualitative research methods that do not require interactions with live human beings - see chapter 16 , "Archival and Historical Sources." But for the most part, you are probably reading this textbook because you are interested in doing research with people. The rest of the chapter will assume this is the case. ↵

One of the primary methodological traditions of inquiry in qualitative research, ethnography is the study of a group or group culture, largely through observational fieldwork supplemented by interviews. It is a form of fieldwork that may include participant-observation data collection. See chapter 14 for a discussion of deep ethnography.

A methodological tradition of inquiry and research design that focuses on an individual case (e.g., setting, institution, or sometimes an individual) in order to explore its complexity, history, and interactive parts. As an approach, it is particularly useful for obtaining a deep appreciation of an issue, event, or phenomenon of interest in its particular context.

The controlling force in research; can be understood as lying on a continuum from basic research (knowledge production) to action research (effecting change).

In its most basic sense, a theory is a story we tell about how the world works that can be tested with empirical evidence. In qualitative research, we use the term in a variety of ways, many of which are different from how they are used by quantitative researchers. Although some qualitative research can be described as “testing theory,” it is more common to “build theory” from the data using inductive reasoning , as done in Grounded Theory . There are so-called “grand theories” that seek to integrate a whole series of findings and stories into an overarching paradigm about how the world works, and much smaller theories or concepts about particular processes and relationships. Theory can even be used to explain particular methodological perspectives or approaches, as in Institutional Ethnography , which is both a way of doing research and a theory about how the world works.

Research that is interested in generating and testing hypotheses about how the world works.

A methodological tradition of inquiry and approach to analyzing qualitative data in which theories emerge from a rigorous and systematic process of induction. This approach was pioneered by the sociologists Glaser and Strauss (1967). The elements of theory generated from comparative analysis of data are, first, conceptual categories and their properties and, second, hypotheses or generalized relations among the categories and their properties – “The constant comparing of many groups draws the [researcher’s] attention to their many similarities and differences. Considering these leads [the researcher] to generate abstract categories and their properties, which, since they emerge from the data, will clearly be important to a theory explaining the kind of behavior under observation.” (36).

An approach to research that is “multimethod in focus, involving an interpretative, naturalistic approach to its subject matter. This means that qualitative researchers study things in their natural settings, attempting to make sense of, or interpret, phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them. Qualitative research involves the studied use and collection of a variety of empirical materials – case study, personal experience, introspective, life story, interview, observational, historical, interactional, and visual texts – that describe routine and problematic moments and meanings in individuals’ lives." ( Denzin and Lincoln 2005:2 ). Contrast with quantitative research .

Research that contributes knowledge that will help people to understand the nature of a problem in order to intervene, thereby allowing human beings to more effectively control their environment.

Research that is designed to evaluate or test the effectiveness of specific solutions and programs addressing specific social problems. There are two kinds: summative and formative .

Research in which an overall judgment about the effectiveness of a program or policy is made, often for the purpose of generalizing to other cases or programs. Generally uses qualitative research as a supplement to primary quantitative data analyses. Contrast formative evaluation research .

Research designed to improve a program or policy (to help “form” or shape its effectiveness); relies heavily on qualitative research methods. Contrast summative evaluation research

Research carried out at a particular organizational or community site with the intention of affecting change; often involves research subjects as participants of the study. See also participatory action research .

Research in which both researchers and participants work together to understand a problematic situation and change it for the better.

The level of the focus of analysis (e.g., individual people, organizations, programs, neighborhoods).

The large group of interest to the researcher. Although it will likely be impossible to design a study that incorporates or reaches all members of the population of interest, this should be clearly defined at the outset of a study so that a reasonable sample of the population can be taken. For example, if one is studying working-class college students, the sample may include twenty such students attending a particular college, while the population is “working-class college students.” In quantitative research, clearly defining the general population of interest is a necessary step in generalizing results from a sample. In qualitative research, defining the population is conceptually important for clarity.

A fictional name assigned to give anonymity to a person, group, or place. Pseudonyms are important ways of protecting the identity of research participants while still providing a “human element” in the presentation of qualitative data. There are ethical considerations to be made in selecting pseudonyms; some researchers allow research participants to choose their own.

A requirement for research involving human participants; the documentation of informed consent. In some cases, oral consent or assent may be sufficient, but the default standard is a single-page easy-to-understand form that both the researcher and the participant sign and date. Under federal guidelines, all researchers "shall seek such consent only under circumstances that provide the prospective subject or the representative sufficient opportunity to consider whether or not to participate and that minimize the possibility of coercion or undue influence. The information that is given to the subject or the representative shall be in language understandable to the subject or the representative. No informed consent, whether oral or written, may include any exculpatory language through which the subject or the representative is made to waive or appear to waive any of the subject's rights or releases or appears to release the investigator, the sponsor, the institution, or its agents from liability for negligence" (21 CFR 50.20). Your IRB office will be able to provide a template for use in your study .

An administrative body established to protect the rights and welfare of human research subjects recruited to participate in research activities conducted under the auspices of the institution with which it is affiliated. The IRB is charged with the responsibility of reviewing all research involving human participants. The IRB is concerned with protecting the welfare, rights, and privacy of human subjects. The IRB has the authority to approve, disapprove, monitor, and require modifications in all research activities that fall within its jurisdiction as specified by both the federal regulations and institutional policy.

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Cookies on this website

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you click 'Accept all cookies' we'll assume that you are happy to receive all cookies and you won't see this message again. If you click 'Reject all non-essential cookies' only necessary cookies providing core functionality such as security, network management, and accessibility will be enabled. Click 'Find out more' for information on how to change your cookie settings.

Tips for a qualitative dissertation

Veronika Williams

17 October 2017

Tips for students

This blog is part of a series for Evidence-Based Health Care MSc students undertaking their dissertations.

Undertaking an MSc dissertation in Evidence-Based Health Care (EBHC) may be your first hands-on experience of doing qualitative research. I chatted to Dr. Veronika Williams, an experienced qualitative researcher, and tutor on the EBHC programme, to find out her top tips for producing a high-quality qualitative EBHC thesis.

1) Make the switch from a quantitative to a qualitative mindset

It’s not just about replacing numbers with words. Doing qualitative research requires you to adopt a different way of seeing and interpreting the world around you. Veronika asks her students to reflect on positivist and interpretivist approaches: If you come from a scientific or medical background, positivism is often the unacknowledged status quo. Be open to considering there are alternative ways to generate and understand knowledge.

2) Reflect on your role

Quantitative research strives to produce “clean” data unbiased by the context in which it was generated. With qualitative methods, this is neither possible nor desirable. Students should reflect on how their background and personal views shape the way they collect and analyse their data. This will not only add to the transparency of your work but will also help you interpret your findings.

3) Don’t forget the theory

Qualitative researchers use theories as a lens through which they understand the world around them. Veronika suggests that students consider the theoretical underpinning to their own research at the earliest stages. You can read an article about why theories are useful in qualitative research here.

4) Think about depth rather than breadth

Qualitative research is all about developing a deep and insightful understanding of the phenomenon/ concept you are studying. Be realistic about what you can achieve given the time constraints of an MSc. Veronika suggests that collecting and analysing a smaller dataset well is preferable to producing a superficial, rushed analysis of a larger dataset.

5) Blur the boundaries between data collection, analysis and writing up

Veronika strongly recommends keeping a research diary or using memos to jot down your ideas as your research progresses. Not only do these add to your audit trail, these entries will help contribute to your first draft and the process of moving towards theoretical thinking. Qualitative researchers move back and forward between their dataset and manuscript as their ideas develop. This enriches their understanding and allows emerging theories to be explored.

6) Move beyond the descriptive

When analysing interviews, for example, it can be tempting to think that having coded your transcripts you are nearly there. This is not the case! You need to move beyond the descriptive codes to conceptual themes and theoretical thinking in order to produce a high-quality thesis. Veronika warns against falling into the pitfall of thinking writing up is, “Two interviews said this whilst three interviewees said that”.

7) It’s not just about the average experience

When analysing your data, consider the outliers or negative cases, for example, those that found the intervention unacceptable. Although in the minority, these respondents will often provide more meaningful insight into the phenomenon or concept you are trying to study.

8) Bounce ideas

Veronika recommends sharing your emerging ideas and findings with someone else, maybe with a different background or perspective. This isn’t about getting to the “right answer” rather it offers you the chance to refine your thinking. Be sure, though, to fully acknowledge their contribution in your thesis.

9) Be selective

In can be a challenge to meet the dissertation word limit. It won’t be possible to present all the themes generated by your dataset so focus! Use quotes from across your dataset that best encapsulate the themes you are presenting. Display additional data in the appendix. For example, Veronika suggests illustrating how you moved from your coding framework to your themes.

10) Don’t panic!

There will be a stage during analysis and write up when it seems undoable. Unlike quantitative researchers who begin analysis with a clear plan, qualitative research is more of a journey. Everything will fall into place by the end. Be sure, though, to allow yourself enough time to make sense of the rich data qualitative research generates.

Related course:

Qualitative research methods.

Short Course

Donate to Refugee Education UK

- See all events

- Add an event

- The EP community

- Thesis directory

- View vacancies

- Choosing edpsy jobs

- Recruiter dashboard

- Educational Psychology

- Northern Ireland

- The edpsy team

- Email updates

- Write for us

Home >> Blog >> Tips on writing a qualitative dissertation or thesis, from Braun & Clarke – Part 1

Tips on writing a qualitative dissertation or thesis, from Braun & Clarke – Part 1

Our advice here relates to many forms of qualitative research, and particularly to research involving the use of thematic analysis (TA).

Based on our experience of supervising students over two decades, as well as our writing on qualitative methodologies, we discuss what we think constitutes good practice – and note some common problems to avoid.

Our first tip is always to check local requirements ! Check what is required in your university context with regard to the format and presentation of your dissertation/thesis; if our advice clashes with this, discuss it with your supervisor. Sometimes requirements are “rules”, and sometimes they’re more norms and conventions, and there’s room to do things differently.

Qualitative centric research writing

Why might our advice here clash with what your local context expects or requires? The simple answer is that there isn’t a widely agreed on single standard for reporting qualitative research. Broadly speaking, there are two styles of qualitative research reporting – let’s call these “add qualitative research and stir” and “qualitative centric”. The “add qualitative and stir” style reflects the default conventions for reporting quantitative research slightly tweaked for qualitative research. Some characteristics of this style of reporting include:

- third-person/passive voice

- searching out and identifying a “gap” in the literature in the introduction

- methodological critique of existing research;

- and, when it comes to reporting the analysis, separate “results” and “discussion” sections.

This style of reporting is far more widely understood and accepted than the other.

What we advocate for is a “qualitative centric” style of reporting – one that is more in line with the ethos and values of qualitative research. This style departs from quantitative norms of empirical research reporting, and is consequently less widely recognised and understood.

This is why you might experience a clash between what we recommend as good practice and what is required in your local context. We experience this clash of reporting values all the time – we have been required by reviewers and editors on numerous occasions to turn our qualitative centric research papers into something more conventional, and our students have sometimes been required by examiners to turn their qualitative centric theses into something more conventional (e.g., by separating out an integrated “results and discussion” and including methodological critique in the introduction).

We want to be open about the fact that there can be risks in a qualitative centric style of reporting! One of the aims of this blog post, and the Twitter thread on which it is based, is to increase understanding of qualitative centric reporting styles so that fewer qualitative researchers are required to rework their research report into something less reflective of the ethos of qualitative research.

So, what are some of the features of a qualitative centric reporting style? Let’s work through a report section by section.

Introduction

Think of the opening section of your report not as a literature review but as an introduction – the introduction is highly likely to include discussion of relevant literature, but the goal of the introduction is not to review the literature and find a “gap”. Instead, your goal in this section is to provide a context and rationale for your research.

If you do discuss bodies of literature, try to avoid summarising study after study after study… instead overview and synthesise a body of literature (What questions have been asked? What, if any, assumptions have been made? What are some of the common themes across the literature?). Have the confidence to tell the reader something about the state of the literature from your perspective.

Theoretical consistency in your introduction

If you embrace fully the ethos and values of qualitative research, you don’t just understand qualitative research as providing you with tools and techniques to generate and analyse data; you’re unlikely to be a committed positivist or (simple/pure) realist. So if you’re not a positivist or realist when conducting and reporting your own research, how should you handle reporting research in your introduction that is positivist/realist? We think it’s important to be theoretically consistent across your report!

That means not being a positivist/realist in your introduction when discussing quantitative research, then shifting to being something else when reporting your research. It means you need to think carefully about how you present and frame the findings of quantitative research. As an example, don’t present results from other projects as statements of fact (e.g. by stating “gay men are more likely than straight men to experience poor body image”), but rather as what other research has reported e.g. by saying “several quantitative studies suggest that gay men are more likely than straight men to experience poor body image”. It’s a subtle but important difference. It shows the reader that you understand your theoretical approach, and that it doesn’t (necessarily) align with the philosophical assumptions underpinning the quantitative research.

We would also advise against engaging in methodological critique based on the values and assumptions of quantitative research in an introduction (methodological critique consistent with the philosophical assumptions of your research may be appropriate).

Framing your research: inverted triangles or stacked boxes?

Ideally, your introduction will make an argument for your research and frame it within relevant wider contexts . It will flow beautifully – the reader will always know why they are being told something and where they are being taken next. There will be no jumping around from one to another seemingly unrelated topic.

To help with flow and structure, work out if your introduction is the classic “inverted triangle” (starts broad and gets increasingly more specific) or what we call the “stacking boxes” structure. With the latter, you have several different topics to discuss but they aren’t easily classifiable as broader or more specific, they are all roughly at the same level. Your task is to decide how to order or stack the boxes! This is a judgement call and you will often need to figure out what works best as you write . We regularly advise our students to reorder their stack of boxes; we do the same with our own work. You can’t always know ahead of writing how things will flow.

With a “stacking boxes” introduction, we strongly recommend having some signposting or an overview at the start of the introduction to help the reader understand what you will cover and where things are going. Try to have linking sentences between different topics or sections to signal transitions to the reader (we’ve been here, now we are going there…).

Research questions/aims

Typically, we’d advise you to end the introduction with your research questions/aims*. Any question (or questions) and aims should make sense to the reader – they definitely should not come as a surprise! – in light of the context you have presented. You want the reader to almost expect and anticipate your research question; you want your research question to make sense .

*Though, in some instances, this might work best at the start, ahead of your box stack! In such cases, you should come back to it at the end or before the start of the methodology. This works within a qualitative-centric introduction because you are not building towards a great “reveal” of the “gap” you have identified.

Make sure you formulate your research question in a way that is consistent with the ethos and values of qualitative research. Don’t frame your research question(s) as hypotheses or, indeed, discuss what you expect to find. A common error is to formulate a research question in terms of the impact or effect of X on Y – which is essentially a poorly-disguised quantitative hypothesis! Our book Successful Qualitative Research provides a detailed discussion of formulating research questions for qualitative research. If you’re using TA, we have recently published a paper Conceptual and Design Thinking for Thematic Analysis t hat includes guidance on appropriate research questions for reflective TA – the approach to TA that we developed and first wrote about in 2006 .

Circling back to the title

Let us circle around to thesis/dissertation titles here too – qualitative research is nothing if not recursive! Double check your title to make sure it isn’t implicitly quantitatively framed either. You really don’t want the reader to read your title and the introduction and be expecting a quantitative study when they get to your research questions! Ideally a good title tells the reader something about the topic, the methodological approach and perhaps also a key message from the analysis. Short, evocative quotations from participants can make great titles. Here’s an example from a project on gay fathers .

Read Part 2 of this blog.

Victoria Clarke and Virginia Braun’s forthcoming book is Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide . They have websites on thematic analysis and the story completion method . You can find them both on Twitter – @drvicclarke and @ginnybraun – where they tweet regularly about qualitative research.

More from edpsy:

Job: Educational Psychologist - Portsmouth

About Victoria Clarke

Victoria is an Associate Professor in Qualitative and Critical Psychology at the University of the West of England, Bristol, UK. You can find her on Twitter - @drvicclarke - regularly tweeting about qualitative research.

View all posts by Victoria Clarke

About Virginia Braun

Virginia is a Professor in Psychology at The University of Auckland, Aotearoa New Zealand. You can find her on Twitter - @ginnybraun – (re)tweeting about qualitative research and other issues.

View all posts by Virginia Braun

Sign up for updates

Find out about new blogs, jobs, features and events by email

We will never share your data

3 Comments so far:

[…] this morning, my supervisor shared this blog post in which Clarke and Braun (2021) share some useful tips on writing a qualitative thesis. In this […]

[…] is an additive model of knowledge. Knowledge is stable and more is continually added. Gap critics say this isn’t the situation in […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More: edpsy.org.uk/blog/2021/tips-on-writing-a-qualitative-dissertation-or-thesis-from-braun-clarke-part-1/ […]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Find out more about us Spotted something wrong? let us know

Community guidelines | Reusing our content | Cookies and privacy

edpsy ltd Piccadilly Business Centre, Aldow Enterprise Park, Manchester, England, M12 6AE Company number: 12669513 (registered in England and Wales)

How To Write The Results/Findings Chapter

For qualitative studies (dissertations & theses).

By: Jenna Crossley (PhD). Expert Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | August 2021

So, you’ve collected and analysed your qualitative data, and it’s time to write up your results chapter. But where do you start? In this post, we’ll guide you through the qualitative results chapter (also called the findings chapter), step by step.

Overview: Qualitative Results Chapter

- What (exactly) the qualitative results chapter is

- What to include in your results chapter

- How to write up your results chapter

- A few tips and tricks to help you along the way

- Free results chapter template

What exactly is the results chapter?

The results chapter in a dissertation or thesis (or any formal academic research piece) is where you objectively and neutrally present the findings of your qualitative analysis (or analyses if you used multiple qualitative analysis methods ). This chapter can sometimes be combined with the discussion chapter (where you interpret the data and discuss its meaning), depending on your university’s preference. We’ll treat the two chapters as separate, as that’s the most common approach.

In contrast to a quantitative results chapter that presents numbers and statistics, a qualitative results chapter presents data primarily in the form of words . But this doesn’t mean that a qualitative study can’t have quantitative elements – you could, for example, present the number of times a theme or topic pops up in your data, depending on the analysis method(s) you adopt.

Adding a quantitative element to your study can add some rigour, which strengthens your results by providing more evidence for your claims. This is particularly common when using qualitative content analysis. Keep in mind though that qualitative research aims to achieve depth, richness and identify nuances , so don’t get tunnel vision by focusing on the numbers. They’re just cream on top in a qualitative analysis.

So, to recap, the results chapter is where you objectively present the findings of your analysis, without interpreting them (you’ll save that for the discussion chapter). With that out the way, let’s take a look at what you should include in your results chapter.

What should you include in the results chapter?

As we’ve mentioned, your qualitative results chapter should purely present and describe your results , not interpret them in relation to the existing literature or your research questions . Any speculations or discussion about the implications of your findings should be reserved for your discussion chapter.

In your results chapter, you’ll want to talk about your analysis findings and whether or not they support your hypotheses (if you have any). Naturally, the exact contents of your results chapter will depend on which qualitative analysis method (or methods) you use. For example, if you were to use thematic analysis, you’d detail the themes identified in your analysis, using extracts from the transcripts or text to support your claims.

While you do need to present your analysis findings in some detail, you should avoid dumping large amounts of raw data in this chapter. Instead, focus on presenting the key findings and using a handful of select quotes or text extracts to support each finding . The reams of data and analysis can be relegated to your appendices.

While it’s tempting to include every last detail you found in your qualitative analysis, it is important to make sure that you report only that which is relevant to your research aims, objectives and research questions . Always keep these three components, as well as your hypotheses (if you have any) front of mind when writing the chapter and use them as a filter to decide what’s relevant and what’s not.

Need a helping hand?

How do I write the results chapter?

Now that we’ve covered the basics, it’s time to look at how to structure your chapter. Broadly speaking, the results chapter needs to contain three core components – the introduction, the body and the concluding summary. Let’s take a look at each of these.

Section 1: Introduction

The first step is to craft a brief introduction to the chapter. This intro is vital as it provides some context for your findings. In your introduction, you should begin by reiterating your problem statement and research questions and highlight the purpose of your research . Make sure that you spell this out for the reader so that the rest of your chapter is well contextualised.

The next step is to briefly outline the structure of your results chapter. In other words, explain what’s included in the chapter and what the reader can expect. In the results chapter, you want to tell a story that is coherent, flows logically, and is easy to follow , so make sure that you plan your structure out well and convey that structure (at a high level), so that your reader is well oriented.

The introduction section shouldn’t be lengthy. Two or three short paragraphs should be more than adequate. It is merely an introduction and overview, not a summary of the chapter.

Pro Tip – To help you structure your chapter, it can be useful to set up an initial draft with (sub)section headings so that you’re able to easily (re)arrange parts of your chapter. This will also help your reader to follow your results and give your chapter some coherence. Be sure to use level-based heading styles (e.g. Heading 1, 2, 3 styles) to help the reader differentiate between levels visually. You can find these options in Word (example below).

Section 2: Body

Before we get started on what to include in the body of your chapter, it’s vital to remember that a results section should be completely objective and descriptive, not interpretive . So, be careful not to use words such as, “suggests” or “implies”, as these usually accompany some form of interpretation – that’s reserved for your discussion chapter.

The structure of your body section is very important , so make sure that you plan it out well. When planning out your qualitative results chapter, create sections and subsections so that you can maintain the flow of the story you’re trying to tell. Be sure to systematically and consistently describe each portion of results. Try to adopt a standardised structure for each portion so that you achieve a high level of consistency throughout the chapter.

For qualitative studies, results chapters tend to be structured according to themes , which makes it easier for readers to follow. However, keep in mind that not all results chapters have to be structured in this manner. For example, if you’re conducting a longitudinal study, you may want to structure your chapter chronologically. Similarly, you might structure this chapter based on your theoretical framework . The exact structure of your chapter will depend on the nature of your study , especially your research questions.

As you work through the body of your chapter, make sure that you use quotes to substantiate every one of your claims . You can present these quotes in italics to differentiate them from your own words. A general rule of thumb is to use at least two pieces of evidence per claim, and these should be linked directly to your data. Also, remember that you need to include all relevant results , not just the ones that support your assumptions or initial leanings.

In addition to including quotes, you can also link your claims to the data by using appendices , which you should reference throughout your text. When you reference, make sure that you include both the name/number of the appendix , as well as the line(s) from which you drew your data.

As referencing styles can vary greatly, be sure to look up the appendix referencing conventions of your university’s prescribed style (e.g. APA , Harvard, etc) and keep this consistent throughout your chapter.

Section 3: Concluding summary

The concluding summary is very important because it summarises your key findings and lays the foundation for the discussion chapter . Keep in mind that some readers may skip directly to this section (from the introduction section), so make sure that it can be read and understood well in isolation.

In this section, you need to remind the reader of the key findings. That is, the results that directly relate to your research questions and that you will build upon in your discussion chapter. Remember, your reader has digested a lot of information in this chapter, so you need to use this section to remind them of the most important takeaways.

Importantly, the concluding summary should not present any new information and should only describe what you’ve already presented in your chapter. Keep it concise – you’re not summarising the whole chapter, just the essentials.

Tips for writing an A-grade results chapter

Now that you’ve got a clear picture of what the qualitative results chapter is all about, here are some quick tips and reminders to help you craft a high-quality chapter:

- Your results chapter should be written in the past tense . You’ve done the work already, so you want to tell the reader what you found , not what you are currently finding .

- Make sure that you review your work multiple times and check that every claim is adequately backed up by evidence . Aim for at least two examples per claim, and make use of an appendix to reference these.

- When writing up your results, make sure that you stick to only what is relevant . Don’t waste time on data that are not relevant to your research objectives and research questions.

- Use headings and subheadings to create an intuitive, easy to follow piece of writing. Make use of Microsoft Word’s “heading styles” and be sure to use them consistently.

- When referring to numerical data, tables and figures can provide a useful visual aid. When using these, make sure that they can be read and understood independent of your body text (i.e. that they can stand-alone). To this end, use clear, concise labels for each of your tables or figures and make use of colours to code indicate differences or hierarchy.

- Similarly, when you’re writing up your chapter, it can be useful to highlight topics and themes in different colours . This can help you to differentiate between your data if you get a bit overwhelmed and will also help you to ensure that your results flow logically and coherently.