164 Phrases and words You Should Never Use in an Essay—and the Powerful Alternatives you Should

This list of words you should never use in an essay will help you write compelling, succinct, and effective essays that impress your professor.

Writing an essay can be a time-consuming and laborious process that seems to take forever.

But how often do you put your all into your paper only to achieve a lame grade?

You may be left scratching your head, wondering where it all went wrong.

Chances are, like many students, you were guilty of using words that completely undermined your credibility and the effectiveness of your argument.

Our professional essay editors have seen it time and time again: The use of commonplace, seemingly innocent, words and phrases that weaken the power of essays and turn the reader off.

But can changing a few words here and there really make a difference to your grades?

Absolutely.

If you’re serious about improving your essay scores, you must ensure you make the most of every single word and phrase you use in your paper and avoid any that rob your essay of its power (check out our guide to editing an essay for more details).

Here is our list of words and phrases you should ditch, together with some alternatives that will be so much more impressive. For some further inspiration, check out our AI essay writer .

Vague and Weak Words

What are vague words and phrases.

Vague language consists of words and phrases that aren’t exact or precise. They can be interpreted in multiple ways and, as such, can confuse the reader.

Essays that contain vague language lack substance and are typically devoid of any concrete language. As such, you should keep your eyes peeled for unclear words when proofreading your essay .

Why You Shouldn’t Use VAGUE Words in Essays

Professors detest vagueness.

In addition to being ambiguous, vague words and phrases can render a good piece of research absolutely useless.

Let’s say you have researched the link between drinking soda and obesity. You present the findings of your literature review as follows:

“Existing studies have found that drinking soda leads to weight gain.”

Your professor will ask:

What research specifically? What/who did it involve? Chimpanzees? Children? OAPs? Who conducted the research? What source have you used?

And the pat on the back you deserve for researching the topic will never transpire.

Academic essays should present the facts in a straightforward, unambiguous manner that leaves no doubt in the mind of the reader.

Key takeaway: Be very specific in terms of what happened, when, where, and to whom.

VAGUE Words and Phrases You Shouldn’t Use in an Essay

Flabby words and expressions, what are flabby expressions.

Flabby expressions and words are wasted phrases. They don’t add any value to your writing but do take up the word count and the reader’s headspace.

Flabby expressions frequently contain clichéd, misused words that don’t communicate anything specific to the reader. For example, if someone asks you how you are feeling and you reply, “I’m fine,” you’re using a flabby expression that leaves the inquirer none the wiser as to how you truly are.

Why Should Flabby Words be Removed from an Essay?

Flabby words are fine in everyday conversation and even blog posts like this.

However, they are enemies of clear and direct essays. They slow down the pace and dilute the argument.

When grading your essay, your professor wants to see the primary information communicated clearly and succinctly.

Removing the examples of flabby words and expressions listed below from your paper will automatically help you to take your essay to a higher level.

Key takeaway: When it comes to essays, brevity is best.

Flabby Words and Expressions You Shouldn’t Use in an Essay

Words to avoid in an essay: redundant words, what are redundant words.

Redundant words and phrases don’t serve any purpose.

In this context, redundant means unnecessary.

Many everyday phrases contain redundant vocabulary; for example, add up, as a matter of fact, current trends, etc.

We have become so accustomed to using them in everyday speech that we don’t stop to question their place in formal writing.

Why You Shouldn’t Use Redundant Words in Essays

Redundant words suck the life out of your essay.

They can be great for adding emphasis in a conversational blog article like this, but they do not belong in formal academic writing.

Redundant words should be avoided for three main reasons:

- They interrupt the flow of the essay and unnecessarily distract the reader.

- They can undermine the main point you are trying to make in your paper.

- They can make you look uneducated.

The most effective essays are those that are concise, meaningful, and astute. If you use words and phrases that carry no meaning, you’ll lose the reader and undermine your credibility.

Key takeaway: Remove any words that don’t serve a purpose.

Redundant Words and Phrases You Shouldn’t Use in an Essay

Colloquial expressions and grammar expletives, what are colloquial expressions.

A colloquial expression is best described as a phrase that replicates the way one would speak.

The use of colloquial language represents an informal, slang style of English that is not suitable for formal and academic documents.

For example:

Colloquial language: “The findings of the study appear to be above board.”

Suitable academic alternative: “The findings of the study are legitimate.”

What are Grammar Expletives?

Grammar expletives are sentences that start with here , there, or it .

We frequently use constructions like these when communicating in both spoken and written language.

But did you know they have a distinct grammatical classification?

They do; the expletive.

Grammar expletives (not to be confused with cuss words) are used to introduce clauses and delay the subject of the sentence. However, unlike verbs and nouns, which play a specific role in expression, expletives do not add any tangible meaning. Rather, they act as filler words that enable the writer to shift the emphasis of the argument. As such, grammar expletives are frequently referred to as “empty words.”

Removing them from your writing can help to make it tighter and more succinct. For example:

Sentence with expletive there : There are numerous reasons why it was important to write this essay. Sentence without expletive: It was important to write this essay for numerous reasons.

Why Should Colloquial Expressions and Grammar Expletives be Removed from an Essay?

While colloquial expressions and grammar expletives are commonplace in everyday speech and are completely acceptable in informal emails and chatroom exchanges, they can significantly reduce the quality of formal essays.

Essays and other academic papers represent formal documents. Frequent use of slang and colloquial expressions will undermine your credibility, make your writing unclear, and confuse the reader. In addition, they do not provide the exactness required in an academic setting.

Make sure you screen your essay for any type of conversational language; for example, figures of speech, idioms, and clichés.

Key takeaway: Grammar expletives use unnecessary words and make your word count higher while making your prose weaker.

Words and Phrases You Shouldn’t Use in an Essay

Nominalization, what is normalization.

A normalized sentence is one that is structured such that the abstract nouns do the talking.

For example, a noun, such as solution , can be structured to exploit its hidden verb, solve .

The act of transforming a word from a verb into a noun is known as normalization.

Should normalization be Removed from an Essay?

This is no universal agreement as to whether normalization should be removed from an essay. Some scholars argue that normalization is important in scientific and technical writing because abstract prose is more objective. Others highlight how normalizations can make essays more difficult to understand .

The truth is this: In the majority of essays, it isn’t possible to present an entirely objective communication; an element of persuasion is inherently incorporated. Furthermore, even the most objective academic paper will be devoid of meaning unless your professor can read it and make sense of it. As such, readability is more important than normalization.

You will need to take a pragmatic approach, but most of the time, your writing will be clearer and more direct if you rely on verbs as opposed to abstract nouns that were formed from verbs. As such, where possible, you should revise your sentences to make the verbs do the majority of the work.

For example,

Use: “This essay analyses and solves the pollution problem.”

Not: “This essay presents an evaluation of the pollution issue and presents a solution.”

While normalized sentences are grammatically sound, they can be vague.

In addition, humans tend to prefer vivid descriptions, and verbs are more vivid, informative, and powerful than nouns.

Key takeaway: Normalization can serve a purpose, but only use it if that purpose is clear.

normalization You Shouldn’t Use in an Essay

That’s a lot to take in.

You may be wondering why you should care?

Cutting the fat helps you present more ideas and a deeper analysis.

Don’t be tempted to write an essay that is stuffed with pompous, complex language: It is possible to be smart and simple.

Bookmark this list now and return to it when you are editing your essays. Keep an eye out for the words you shouldn’t use in an essay, and you’ll write academic papers that are more concise, powerful, and readable.

- Order Proofreading Order Resume Writing Additional services for: Academics Authors Businesses

- Get Proofreading

- All Services

- Free Samples

List of 125 Words and Phrases You Should Never Use in an Essay

Made in the USA (we edit US , UK , Australian , and Canadian English). © 2024 ProofreadingServices.com, LLC | Terms | Privacy | Accessibility

- Subscribe for Discounts and Tips

Please choose your service:

Proofreading and editing.

GET A QUOTE

Translation

Publishing and marketing for authors, resumes, cvs, and cover letters, ghostwriting books, please select from the options below:, memoir ghostwriting, ghostwriting for ceos.

back to the other services

- Translators

- Graphic Designers

Please enter the email address you used for your account. Your sign in information will be sent to your email address after it has been verified.

Avoid These Words and Phrases in Your Academic Writing

When writing an academic essay, thesis, or dissertation, your professor or advisor usually gives you a rubric with detailed expectations to guide you during the process. While the rubric will identify the major requirements for the paper, it will probably not tell you what words or phrases you need to avoid. Whether you want to earn a stellar grade on your next paper or you're hoping to get published in an academic journal, keep reading to discover words and phrases you need to avoid in your academic writing.

"A great deal of"

I encounter the phrase a great deal of in most academic papers that I edit. Avoid using this vague phrase, because your academic writing should be specific and informative. Instead of saying a great deal of, provide exact measurements or specific quantities.

"A lot"

Similar to the previous phrase (a great deal of), a lot is too vague and informal for an academic paper. Use precise quantities instead of this overly general phrase.

"Always"

Avoid using the word always in your academic writing, because it can generalize a statement and convey an absolute that might not be accurate. If you want to state something about all the participants in your study, use specific language to clarify that the statement applies to a consistent action among the participants in your study.

It is almost a cliché to tell you to avoid clichés, but it is an essential piece of writing advice. Clichés are unoriginal and will weaken your writing. In academic writing, using clichés will erode your credibility and take away from all the research and hard work you have put into your project.

What qualifies as a cliché? According to Dictionary.com , A cliché is an expression, idea, or action that has been overused to the point of seeming worn out, stale, ineffective, or meaningless. Your words should be original, carry meaning, and resonate with your readers, and this is especially important for academic writing. Most clichés have been used so frequently in so many different contexts that they have lost their meaning. To eliminate clichés, scan your paper for any phrases that you could type into an internet browser and find millions of search results from all different topic areas. If you are unsure if your favorite phrases are overused clichés, consult this Cliché List for a comprehensive list.

Contractions

Academic writing should be formal and professional, so refrain from using contractions. Dictionary.com offers the following advice regarding contractions: Contractions such as isn't, couldn't, can't, weren't, he'll, they're occur chiefly, although not exclusively, in informal speech and writing. They are common in personal letters, business letters, journalism, and fiction; they are rare in scientific and scholarly writing. Contractions occur in formal writing mainly as representations of speech. When you proofread your paper, change any contractions back to the original formal words.

Double negatives

Double negatives will confuse your readers and dilute the power of your words. For example, consider the following sentence:

"He was not unwilling to participate in the study."

The word not and the prefix un- are both negatives, so they cancel each other out and change the meaning of the sentence. If you want to convey that someone reluctantly participated in the study, express that clearly and explicitly.

"Etc."

The abbreviation etc. is short for the Latin word et cetera , which means and others; and so forth; and so on. Dictionary.com specifies that etc. is used to indicate that more of the same sort or class might have been mentioned, but for brevity have been omitted. I discourage writers from using etc. in academic writing, because if you are writing an academic paper, you are writing to share information or scholarly research, and you are not conveying any new information with the abbreviation etc. Instead of writing etc., explicitly state the words or list that you are alluding to with your use of etc. If you absolutely must use etc. , make sure you only use it if readers can easily identify what etc. represents, and only use etc. at the end of lists that are within parentheses.

"For all intents and purposes" and "for all intensive purposes"

These two phrases are often used interchangeably, but you should avoid both of them in your academic writing. Avoid the second phrase in all of your writing: For all intensive purposes is an eggcorn (a word or phrase that is mistakenly used for another word or phrase because it sounds similar). For all intents and purposes is generally a filler phrase that does not provide any new information, so you can usually omit it without replacing it.

An idiom is an expression whose meaning is not predictable from the usual meanings of its constituent elements. Idioms include phrases such as he kicked the bucket, and they are particularly problematic in academic writing, because non-native English speakers might not understand your intended meaning. Below are three of the idioms I encounter most frequently when editing academic papers:

- All things being equal : All things being equal is usually an unnecessary or redundant phrase that you can simply omit without replacing with anything else.

- In a nutshell : Instead of saying in a nutshell, use a more universal phrase such as in summary or in conclusion.

- On the other hand : Idioms such as on the other hand are informal and will weaken your paper. Instead of writing the phrase on the other hand, consider using conversely.

In-text ampersands ("&")

Do not use ampersands in place of the word and in sentences. Most style guides dictate that you use an ampersand for parenthetical in-text citations, but you need to spell out the word and in your paper. An ampersand within the text of your paper is too informal for an academic paper.

"I think"

You do not need to include the phrase I think when explaining your point of view. This is your paper, and it should contain your original thoughts or findings, so it is redundant to include the phrase I think. Doing so will weaken your writing and your overall argument.

"Never"

Similar to the word " always, " avoid using the word never in your academic writing. Always and never will overgeneralize your statements. If you absolutely must use never in your academic writing, make sure that you specify that it applies only to the participants in your study and should not be applied to the general population.

"Normal"

Avoid using subjective terms such a normal in your academic papers. Instead, use scientific or academic terms such as control group or standard. Remember that what you consider normal might be abnormal to someone else, but a control group or standard should be objective and definable.

Passive voice

Passive voice is one of the most frequent issues that I correct when editing academic papers. Some students think passive voice provides a more formal tone, but it actually creates more confusion for your readers while also adding to your word count. As the UNC Writing Center explained , The primary reason why your instructors frown on the passive voice is that they often have to guess what you mean. Most style guidelines (APA, MLA, Chicago) also specify that writers should avoid passive sentences. Whether you're writing your first draft or proofreading for what feels like the hundredth time, you can change passive sentences by making sure that the subject of your sentence is performing the action.

One way to look out for passive voice is to pay attention anytime you use by or was. These two words do not always indicate passive voice, but if you pay attention, they can help you spot passive voice. For example, the following sentence uses passive voice:

"The study was conducted in 2021."

If your style guideline allows you to use personal pronouns, specify a subject and reword the sentence to say:

"We conducted the study in 2021."

If your style guideline dictates that you avoid personal pronouns, you can make the sentence active by saying:

"The researchers conducted the study in 2021."

There are exceptions to most writing tips, but not this one: You should never use profanity in your academic writing. Profanity is informal, and many people might find it offensive, crude, or rude. Even if you enjoy creating controversy or getting a rise out of your readers, avoid profane words that might offend professors or other readers.

Academic writing can feel overwhelming, but hopefully this list of words and phrases to avoid in academic writing will help you as you navigate your next big assignment. Although there are exceptions to some items on this list, you will grow as a writer if you learn to avoid these words and phrases. If you consult your professor or advisor's rubric, adhere to style guidelines, and avoid the words or phrases on this list, you might even have fun the next time you have to stay up all night to finish an academic paper.

- Academic Writing Advice

- All Blog Posts

- Writing Advice

- Admissions Writing Advice

- Book Writing Advice

- Short Story Advice

- Employment Writing Advice

- Business Writing Advice

- Web Content Advice

- Article Writing Advice

- Magazine Writing Advice

- Grammar Advice

- Dialect Advice

- Editing Advice

- Freelance Advice

- Legal Writing Advice

- Poetry Advice

- Graphic Design Advice

- Logo Design Advice

- Translation Advice

- Blog Reviews

- Short Story Award Winners

- Scholarship Winners

Need an academic editor before submitting your work?

- Thesis & Dissertation Editing

- Books and Journal Articles

- Coaching and Consultation

- Research Assistance

- Quantitative

- Qualitative

- Document Review Service

- Meet The Team

- Client Testimonials

- Join Our Team

- Get In Touch

- Make Payment

Most Popular

Chatgpt and similar ai is not going to kill you, but ignoring it might.

11 days ago

Writing a Personal Essay From the Start

10 days ago

Schools Bet on Performance-Based Salaries for Teachers. Did It Pay Off?

Overcoming challenges in analytical essay writing, how should i format my college essay properly, words to avoid in academic writing.

“Very” creates an overstatement. Take the sentence, “She was very radiant.” Radiant is a powerful word already. Let it do its work alone without adding extra emphasis.

Words to use instead: genuinely, veritably, undoubtedly, profoundly, indubitably.

2. Of course

A reader is often unfamiliar with the material you are presenting. If you use of course , the reader may believe they are not smart enough or feel you are not explaining your material well enough. Simply present your case without fluff-language. If you feel you have to use “of course,” use the words below:

Words to use instead: clearly, definitely, indeed, naturally, surely.

It seems when we do not know how to describe an object or phenomena, we use “thing.” Writing, especially in the academic realm, is about being specific. Using “thing” does not provide any specificity whatsoever.

What to write instead: Discuss your subject directly. For instance:

“I loved the thing she did,” could be changed to, “I loved her salsa dancing on Friday nights by Makelmore Harbor.”

Do you know of a person, place, or phenomena that “always” does an action? “Always” is almost always not true.

What to write instead: Consider how often your subject does an action. Say someone at your work is consistently late, but is on time occasionally. Some people might write, “He is always late to work.” As an alternative, you could write, “He is late to work most of the time.” If you are writing a serious paper, consider going further and give exact numbers, such as, “He is late to work 88.6% of the time in the mornings, during the months of September, August, and May.”

Similar to “always,” do you know of any person, place, or object that “never” does a certain action?

What to write instead: Let us look at this sentence: “Maggie never lost her temper because she was a good girl.” A better way to approach this sentence would be to say, “Maggie rarely lost her temper, as she was brought up in believing that displaying her anger was the worst form of human expression.”

6. (Contractions) Can’t, won’t, you’ve…

When you are writing an essay, a research paper, or a review, you are presenting yourself as an expert or professional that wants to send your message across to an audience. Most readers are not wanting to be written to in a casual way. They expect we respect them and that respect is in the form of the language we use. Contractions show we are either lazy or are talking to a lower-level audience.

Instead of writing contractions, simply use the original form of the word.

Akin to “very,” it is not necessary to use and is a form of overstatement.

Words to use instead: extremely, remarkably, unusually, consequently, accurate.

Using “a lot” refers to a quantity, but it does not tell the reader how much exactly. Keep the idea of specificity in your mind when you write. It is better to state the exact amount or at least hand over an educated guess.

What to write instead:

Here is an incorrect sentence first: “I ate a lot of ice cream this morning.” The correct version: “I ate two dinner-sized bowls of ice cream this morning.”

It does not give an appropriate description of a subject. It is recommended to be more specific.

Words to use instead: commendable, reputable, satisfactory, honorable, pleasing.

What does “stuff” mean, anyways?

Words to use instead: belongings, gear, goods, possessions, substance.

This word is vague. It generally means “satisfactory,” but a reader cannot be entirely sure.

Words to use instead: admirable, cordial, favorable, genial, obliging.

A hollow word that does not add much value.

Words to use instead: precisely, assuredly, veritably, distinctly, unequivocally.

Sometimes, writers stamp “many” down on a page without realizing that it means almost nothing to a reader. If you want your audience to know about a quantity, why not state its specifics? But if you cannot provide the details, try these:

Words to use instead: copious, bountiful, myriad, prevalent, manifold.

14. In conclusion

Your readers know it is your conclusion by being the last paragraph(s) and that you are summarizing. There is no reason to state it is your conclusion.

What to write instead: Exclude cookie cutter phrases. Go straight to your summary and afterthought.

15. Firstly, secondly, thirdly…

Your readers knows where your first, second, and third body paragraphs are because they can count. You do not need to state the obvious.

What to write instead: Lead into your body paragraphs by beginning with a topic sentence that follows the concepts outlined in your thesis statement.

16. Finally/lastly

Your readers can see it is your ending point by being the last section in your paragraph(s). And even if the placement of your final point is not clear, there is no real reason to state that it is the last topic.

What to write instead: Write your transitions naturally, without plastic, pre-made phrases. Relate your transitions to the content that was before it.

17. Anything

“Anything” could be, well, “anything.” Specifics, specifics, specifics.

What to write instead: The common phrase, “It can be anything,” can be broken down into details that relate to your composition. Say you are writing about topics for poetry. Instead of stating that, “Poetry can be written about anything,” why not list some possibilities: “Your loneliness in a new city, a recent divorce, how an insect flies through wind filled with tree fluff, your disgust of politics in Buenos Aires, how you wished you could transform into a clock: all these topics and more are valid when writing poetry.”

18. Kind of

A casual version of saying:

“type of” “in the category of” “within the parameters of”

19. Find out

Imagine you are Sherlock Holmes. I bet when you finished a case, you would not say, “I found out the reason that….” No, you would be stately and expound, “I have examined , investigated, interrogated, discovered, realized that Mr. Shuman was tied counter-clockwise to the rope that was set by the food agency’s mole to convert a missionary to blasphemy.”

20. Various/variety

The fathers of ambiguity, these words does not relate to any concrete object, person, or phenomena. It is best to list the “various” or a “variety” of objects, people, or places you are examining in your piece of writing. But if you cannot come up with a proper list, you can insert one of the following words in place of various or variety :

What to write instead: discrete, disparate, diverse, multifarious, divergent.

Similarly, if you see any of these words in a paper, most likely it wasn’t written by a professional. Such works are better not to be trusted as reliable sources. Even the best essay writing services prove that knowledgeable writers avoid these constructions when completing tasks.

Follow us on Reddit for more insights and updates.

Comments (0)

Welcome to A*Help comments!

We’re all about debate and discussion at A*Help.

We value the diverse opinions of users, so you may find points of view that you don’t agree with. And that’s cool. However, there are certain things we’re not OK with: attempts to manipulate our data in any way, for example, or the posting of discriminative, offensive, hateful, or disparaging material.

Comments are closed.

More from Writing Essentials

Dec 17 2014

10 Rules of Creative Writing

< 1 min read

Jun 04 2014

Relevant Sources

May 15 2014

Evidence Support

Samples for words to avoid in academic writing, presentation of words to avoid essay sample, example.

Remember Me

What is your profession ? Student Teacher Writer Other

Forgotten Password?

Username or Email

- Tips & Guides

How To Avoid Using “We,” “You,” And “I” in an Essay

- Posted on October 27, 2022 October 27, 2022

Maintaining a formal voice while writing academic essays and papers is essential to sound objective.

One of the main rules of academic or formal writing is to avoid first-person pronouns like “we,” “you,” and “I.” These words pull focus away from the topic and shift it to the speaker – the opposite of your goal.

While it may seem difficult at first, some tricks can help you avoid personal language and keep a professional tone.

Let’s learn how to avoid using “we” in an essay.

What Is a Personal Pronoun?

Pronouns are words used to refer to a noun indirectly. Examples include “he,” “his,” “her,” and “hers.” Any time you refer to a noun – whether a person, object, or animal – without using its name, you use a pronoun.

Personal pronouns are a type of pronoun. A personal pronoun is a pronoun you use whenever you directly refer to the subject of the sentence.

Take the following short paragraph as an example:

“Mr. Smith told the class yesterday to work on our essays. Mr. Smith also said that Mr. Smith lost Mr. Smith’s laptop in the lunchroom.”

The above sentence contains no pronouns at all. There are three places where you would insert a pronoun, but only two where you would put a personal pronoun. See the revised sentence below:

“Mr. Smith told the class yesterday to work on our essays. He also said that he lost his laptop in the lunchroom.”

“He” is a personal pronoun because we are talking directly about Mr. Smith. “His” is not a personal pronoun (it’s a possessive pronoun) because we are not speaking directly about Mr. Smith. Rather, we are talking about Mr. Smith’s laptop.

If later on you talk about Mr. Smith’s laptop, you may say:

“Mr. Smith found it in his car, not the lunchroom!”

In this case, “it” is a personal pronoun because in this point of view we are making a reference to the laptop directly and not as something owned by Mr. Smith.

Why Avoid Personal Pronouns in Essay Writing

We’re teaching you how to avoid using “I” in writing, but why is this necessary? Academic writing aims to focus on a clear topic, sound objective, and paint the writer as a source of authority. Word choice can significantly impact your success in achieving these goals.

Writing that uses personal pronouns can unintentionally shift the reader’s focus onto the writer, pulling their focus away from the topic at hand.

Personal pronouns may also make your work seem less objective.

One of the most challenging parts of essay writing is learning which words to avoid and how to avoid them. Fortunately, following a few simple tricks, you can master the English Language and write like a pro in no time.

Alternatives To Using Personal Pronouns

How to not use “I” in a paper? What are the alternatives? There are many ways to avoid the use of personal pronouns in academic writing. By shifting your word choice and sentence structure, you can keep the overall meaning of your sentences while re-shaping your tone.

Utilize Passive Voice

In conventional writing, students are taught to avoid the passive voice as much as possible, but it can be an excellent way to avoid first-person pronouns in academic writing.

You can use the passive voice to avoid using pronouns. Take this sentence, for example:

“ We used 150 ml of HCl for the experiment.”

Instead of using “we” and the active voice, you can use a passive voice without a pronoun. The sentence above becomes:

“150 ml of HCl were used for the experiment.”

Using the passive voice removes your team from the experiment and makes your work sound more objective.

Take a Third-Person Perspective

Another answer to “how to avoid using ‘we’ in an essay?” is the use of a third-person perspective. Changing the perspective is a good way to take first-person pronouns out of a sentence. A third-person point of view will not use any first-person pronouns because the information is not given from the speaker’s perspective.

A third-person sentence is spoken entirely about the subject where the speaker is outside of the sentence.

Take a look at the sentence below:

“In this article you will learn about formal writing.”

The perspective in that sentence is second person, and it uses the personal pronoun “you.” You can change this sentence to sound more objective by using third-person pronouns:

“In this article the reader will learn about formal writing.”

The use of a third-person point of view makes the second sentence sound more academic and confident. Second-person pronouns, like those used in the first sentence, sound less formal and objective.

Be Specific With Word Choice

You can avoid first-personal pronouns by choosing your words carefully. Often, you may find that you are inserting unnecessary nouns into your work.

Take the following sentence as an example:

“ My research shows the students did poorly on the test.”

In this case, the first-person pronoun ‘my’ can be entirely cut out from the sentence. It then becomes:

“Research shows the students did poorly on the test.”

The second sentence is more succinct and sounds more authoritative without changing the sentence structure.

You should also make sure to watch out for the improper use of adverbs and nouns. Being careful with your word choice regarding nouns, adverbs, verbs, and adjectives can help mitigate your use of personal pronouns.

“They bravely started the French revolution in 1789.”

While this sentence might be fine in a story about the revolution, an essay or academic piece should only focus on the facts. The world ‘bravely’ is a good indicator that you are inserting unnecessary personal pronouns into your work.

We can revise this sentence into:

“The French revolution started in 1789.”

Avoid adverbs (adjectives that describe verbs), and you will find that you avoid personal pronouns by default.

Closing Thoughts

In academic writing, It is crucial to sound objective and focus on the topic. Using personal pronouns pulls the focus away from the subject and makes writing sound subjective.

Hopefully, this article has helped you learn how to avoid using “we” in an essay.

When working on any formal writing assignment, avoid personal pronouns and informal language as much as possible.

While getting the hang of academic writing, you will likely make some mistakes, so revising is vital. Always double-check for personal pronouns, plagiarism , spelling mistakes, and correctly cited pieces.

You can prevent and correct mistakes using a plagiarism checker at any time, completely for free.

Quetext is a platform that helps you with all those tasks. Check out all resources that are available to you today.

Sign Up for Quetext Today!

Click below to find a pricing plan that fits your needs.

You May Also Like

How to Write Polished, Professional Emails With AI

- Posted on May 30, 2024

A Safer Learning Environment: The Impact of AI Detection on School Security

- Posted on May 17, 2024

Rethinking Academic Integrity Policies in the AI Era

- Posted on May 10, 2024 May 10, 2024

Jargon Phrases to Avoid in Business Writing

- Posted on May 3, 2024 May 3, 2024

Comparing Two Documents for Plagiarism: Everything You Need to Know

- Posted on April 26, 2024 April 26, 2024

Mastering Tone in Email Communication: A Guide to Professional Correspondence

- Posted on April 17, 2024

Mastering End-of-Sentence Punctuation: Periods, Question Marks, Exclamation Points, and More

- Posted on April 12, 2024

Mastering the Basics: Understanding the 4 Types of Sentences

- Posted on April 5, 2024

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Scholarly Voice: Commonly Confused Words

Diction for academic writing.

Diction refers to an author’s word choice. The APA manual stresses the importance of proper word choice because academic writing should be as precise as possible. Follow the word choice guidelines below to make sure you are communicating in a clear, precise manner.

Accept and except: "Accept " means to agree; "except " suggests exclusion. Example: I accepted all the applicants except Mr. Lee.

Advice and advise: "Advice " is a noun and is a suggestion; "advise " is a verb and is the act of giving that suggestion. Example: I advise all of my clients to get more sleep; most of them take this advice.

Affect and effect: "Affect " is a verb that refers to the influence that something has on something else; "effect " is a noun that refers to a result. Example: Did Vitamin C affect the patients? I am curious if it had any effect.

Allude and elude: "Allude " is in indirect reference to something else; "elude " means to avoid. Example: The criminal was able to elude the police when his friend alluded that the shopkeeper was responsible for the crime.

Although and while: "Although" is a conjunction that indicates a contrast (despite something being the case). "While" is a conjunction that indicates a time and is also a noun referring to a period of time. Example: Although he disliked rain, he went out while it was raining to find his missing cat. Note that in APA style, use of "while" is more restrictive than in common usage.

Among and between: "Between" is reserved for two items; "among" is used for three or more. Example: It was easy to choose between the peach cobbler and the apple crisp; however, it was difficult to decide among the brownie, ice cream, and custard.

Any body, anybody, any one, and anyone: "Any body" and "any one" are adjectives modifying a noun. Example: I like to swim in any body of water. I could not single out any one person. "Anybody" and "anyone" are pronouns. Example: He would go to prom with anyone. Anybody would do!

Assume and presume: To "assume" something is to base information on nothing. Example: I assume that next year’s party will be fun. To "presume" something is to base information on evidence or facts. Example: I presume the shirt is on sale because it was on the sale rack.

Assure, ensure, and insure: "Assure" means to confirm (usually with an individual or group of individuals); "ensure" means to make sure that something is accomplished; and "insure" means to protect from harm (usually referring to protection from financial loss). Example: I assured the home owners that their homes were insured. I ensured this protection by providing them with a sound policy.

Attribute and contribute: An "attribute" is a noun that refers to a characteristic of something. Example: His best attribute was his sense of humor. To "attribute," as a transitive verb, is to explain something by noting its cause. Example: I attribute my winning personality to my humor. To contribute is to give something to help people or causes. Example: She likes to contribute time to her local soup kitchen.

Because: See Since and because.

Between: See Among and between.

Casual and causal: "Casual" refers to something that is informal or unplanned. Example: They wore casual clothes for the party. "Causal" refers to the cause of something or to something that makes things happen. Example: The causal factor in the students’ declining energy was the absence of lunch.

Causal: See Casual and causal.

Cite, sight, and site: "Cite" means to refer to another source for a claim you make. Example: Make sure to cite the author of each source you discuss. "Sight" means the visual sense (what you can see). Example: Using sight as well as smell, the dog navigated the maze. "Site " means a location, as in a study site. Example: The researcher found the middle school to be a useful site for studying bullying behaviors.

Complement and compliment: "Complement " suggests that one item helps complete another one; "compliment " is an act of praise. Example: I complimented Dustin on how his eyes complemented his complexion.

Conscience and conscious: "Conscience " refers to one’s morality; "conscious " is in reference to one’s awareness of his or her surroundings. Example: The hypnotist had no conscience when his subjects were unconscious.

Consequently and subsequently: "Consequently " suggests causation; "subsequently " refers to something that happens later and is not caused by the previously mentioned action. Example: Vera lost her dog, and Doug subsequently lost his cat. Consequently, they met each other at the Humane Society.

Contribute: See Attribute and contribute.

Desert and dessert: The "desert " is a region you would visit. "Dessert " is usually the last part of a meal. Example: We went to the desert and ate a dessert. Helpful hint: the extra "s" is in the food because you always want more.

Dragged and drug: The past tense of the word "drag " is "dragged." Example: She dragged her brother out of bed. "Drug " refers to a chemical substance (noun) or to administer such a substance (verb).

Drug and dragged: See Dragged and drug.

Effect: See Affect and effect.

Elude: See Allude and elude.

Ensure: See Assure, ensure, and insure.

Every day and everyday: " Every day " is an adjective and a noun; "everyday " is just an adjective asserting that something is commonplace. Example: I brush my teeth every day; it is part of my everyday hygiene routine.

Every one and everyone: " Every one " is an adjective and a pronoun; "everyone " is a pronoun. Example: I counted every one. This seemed to satisfy everyone at the party.

Except and accept: See Accept and except.

Explicit and implicit: "Explicit " suggests that something is overt; "implicit " means that something is indirectly implied. Example: His explicit instructions were that I should clean; he made it implicitly clear that I do a good job.

Farther and further: " Farther " refers to a physical distance; "further " refers to time. Example: Until further notice, you are not allowed to go any farther.

Fewer and less: " Fewer " should be used with things that can be counted; "less " should be used for amounts you cannot count. Example: Fewer boys than girls were upset; however, the girls were less upset than anticipated.

Former and latter: These terms should be used sparingly and only when referring to two items. "Former " means the first item referred to (remember both "former" and "first" begin with "f"), and "latter " means the last item (both "latter" and "last" begin with "l"). Example: Writing specialists like reading and writing; students prefer the former. (This means students prefer reading.)

If and whether: "If " and "whether " are often interchangeable. However, it is important to use "if " when referring to something that is conditional. Example: Bring your key if you come to the house. (This sentence is conditional because you only need to bring the key if you come to the house.) Example: Bring your key whether or not you come to the house. (This sentence is not conditional because you will have to bring your key either way.)

Implicit: See Explicit and implicit.

Imply and infer: See Infer and imply.

Infer and imply: "Infer " means to deduce something and is what readers do. "Imply " means to hint or suggest, and it is what writers do. Example: She described a red, octagonal sign in the parking lot. I inferred it was a stop sign. Example: The teacher implied that there might be pop quiz tomorrow.

Insure: See Assure, ensure, and insure.

Its and it’s: "Its" is the possessive form of "it"; "it’s" is a contraction meaning "it is." Example: The baby saw the dog and grabbed its tail. It’s interesting that she would do that. Note that in APA style, you should avoid contractions, so you would never use "it’s" for a paper in APA style.

Latter and former: See Former and latter.

Lay and lie: "Lay " means to put down an object. Example: She lays the baby in the crib. "Lie " means to put yourself down or to recline. Example: I lie in bed, dreaming of summer.

Less: See Fewer and less.

Lie: See Lay and lie.

Loose and lose: "Loose " suggests that something is not properly attached; "lose " means to misplace something. Example: Her loose-fitting clothes caused her to lose her balance.

May be and maybe: " May be " is a verb phrase; "maybe " is an adverb. Example: Obiwan Kenobi may be our last hope, or maybe someone else will save us.

Nor and or: Use "nor " with "neither " and "or " with "either." Example: Neither Kenneth nor Christine got to work on time. The boss may fire either Kenneth or Christine.

Peak, peek, and pique: "Peak " means the top or maximum of something. Example: I climbed to the peak of the mountain. "Peek " means to sneak a look at something. Example: The girl peeked at her birthday present when her parents were out. "Pique " means a sudden anger or annoyance at being offended (noun) or to make someone angry (verb). Example: In a fit of pique, she threw her phone across the room. As a verb, "pique " can also mean to raise someone’s curiosity. Example: The book’s cover piqued my interest.

Peek: See peak, peek, and pique.

Pique: See peak, peek, and pique.

Precede and proceed: "Precede " suggests that something comes before; proceed is an invitation to continue. Example: According to league rules, the game could not proceed unless “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” preceded the bottom of the sixth inning.

Presume: See Assume and presume.

Principal and principle: As a noun, "principal " refers to an individual; as an adjective, it suggests that something is significant. "Principle" suggests that something is grounded in theory. Example: The principal insisted that the principal component of the school’s success was its teachers. The principal insisted that the teachers taught Darwinian principles.

Proceed: See Precede and proceed.

Sight: See Cite, sight, and site.

Since and because: "Since " is used to indicate time. For example, the dog hasn’t been walked since you started school. "Because " should be used in all other instances, such as causal relationships and to show causation. For example, I want to go to school because I don’t like walking the dog.

Site: See Cite, sight, and site.

Subsequently: See Consequently and subsequently.

Than and then: " Than " suggests a comparison; "then " explains what follows. Example: Ben was faster than Mark. We then knew who the second fastest member of the team was.

That and which: "That " is a restrictive pronoun, meaning what follows is necessary for the reader to understand. "Which " is unrestrictive, suggesting that the following information is an aside. Example: Sticks of dynamite, which we planted last night, will destroy the vault. The vault that was next door, however, was indestructible.

That and who: Use "that " for objects and "who " for people. I know she likes marshmallows that are burnt. (Here the word "that " refers to the marshmallows.) I know someone who likes burnt marshmallows. (Here the word "who " refers to someone.)

Their, there, and they’re: "Their " is a pronoun. "There " is a noun referring to a place. "They’re " is a contraction meaning "they are." Example: They’re going over there. It is their anniversary. Note that in APA style, you should not use contractions.

Then: See Than and then.

To, too, and two: "To" is generally used as a preposition. "Too " means in addition. "Two " refers to the number. Example: You will need two pots to cook spaghetti. You will need a cauldron, too.

Whether and if: See If and whether.

Which: See That and which.

While: See Although and while.

Who: See That and who.

Who’s and whose: "Who’s" is a contraction meaning "who is"; "whose " is a possessive form of "who." Example: Who’s missing a pair of gloves? I’ would like to know whose these are.

Your and you’re: "Your " is a possessive form of you; "you’re" is a contraction meaning "you are." Example: This is your mug. You're going to take that home with you, right? Remember that in APA style, you should not use contractions.

Related Resource

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Using Academic Diction

- Next Page: Verb Choice

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Academic Writing Style

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Academic writing refers to a style of expression that researchers use to define the intellectual boundaries of their disciplines and specific areas of expertise. Characteristics of academic writing include a formal tone, use of the third-person rather than first-person perspective (usually), a clear focus on the research problem under investigation, and precise word choice. Like specialist languages adopted in other professions, such as, law or medicine, academic writing is designed to convey agreed meaning about complex ideas or concepts within a community of scholarly experts and practitioners.

Academic Writing. Writing Center. Colorado Technical College; Hartley, James. Academic Writing and Publishing: A Practical Guide . New York: Routledge, 2008; Ezza, El-Sadig Y. and Touria Drid. T eaching Academic Writing as a Discipline-Specific Skill in Higher Education . Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 2020.

Importance of Good Academic Writing

The accepted form of academic writing in the social sciences can vary considerable depending on the methodological framework and the intended audience. However, most college-level research papers require careful attention to the following stylistic elements:

I. The Big Picture Unlike creative or journalistic writing, the overall structure of academic writing is formal and logical. It must be cohesive and possess a logically organized flow of ideas; this means that the various parts are connected to form a unified whole. There should be narrative links between sentences and paragraphs so that the reader is able to follow your argument. The introduction should include a description of how the rest of the paper is organized and all sources are properly cited throughout the paper.

II. Tone The overall tone refers to the attitude conveyed in a piece of writing. Throughout your paper, it is important that you present the arguments of others fairly and with an appropriate narrative tone. When presenting a position or argument that you disagree with, describe this argument accurately and without loaded or biased language. In academic writing, the author is expected to investigate the research problem from an authoritative point of view. You should, therefore, state the strengths of your arguments confidently, using language that is neutral, not confrontational or dismissive.

III. Diction Diction refers to the choice of words you use. Awareness of the words you use is important because words that have almost the same denotation [dictionary definition] can have very different connotations [implied meanings]. This is particularly true in academic writing because words and terminology can evolve a nuanced meaning that describes a particular idea, concept, or phenomenon derived from the epistemological culture of that discipline [e.g., the concept of rational choice in political science]. Therefore, use concrete words [not general] that convey a specific meaning. If this cannot be done without confusing the reader, then you need to explain what you mean within the context of how that word or phrase is used within a discipline.

IV. Language The investigation of research problems in the social sciences is often complex and multi- dimensional . Therefore, it is important that you use unambiguous language. Well-structured paragraphs and clear topic sentences enable a reader to follow your line of thinking without difficulty. Your language should be concise, formal, and express precisely what you want it to mean. Do not use vague expressions that are not specific or precise enough for the reader to derive exact meaning ["they," "we," "people," "the organization," etc.], abbreviations like 'i.e.' ["in other words"], 'e.g.' ["for example"], or 'a.k.a.' ["also known as"], and the use of unspecific determinate words ["super," "very," "incredible," "huge," etc.].

V. Punctuation Scholars rely on precise words and language to establish the narrative tone of their work and, therefore, punctuation marks are used very deliberately. For example, exclamation points are rarely used to express a heightened tone because it can come across as unsophisticated or over-excited. Dashes should be limited to the insertion of an explanatory comment in a sentence, while hyphens should be limited to connecting prefixes to words [e.g., multi-disciplinary] or when forming compound phrases [e.g., commander-in-chief]. Finally, understand that semi-colons represent a pause that is longer than a comma, but shorter than a period in a sentence. In general, there are four grammatical uses of semi-colons: when a second clause expands or explains the first clause; to describe a sequence of actions or different aspects of the same topic; placed before clauses which begin with "nevertheless", "therefore", "even so," and "for instance”; and, to mark off a series of phrases or clauses which contain commas. If you are not confident about when to use semi-colons [and most of the time, they are not required for proper punctuation], rewrite using shorter sentences or revise the paragraph.

VI. Academic Conventions Among the most important rules and principles of academic engagement of a writing is citing sources in the body of your paper and providing a list of references as either footnotes or endnotes. The academic convention of citing sources facilitates processes of intellectual discovery, critical thinking, and applying a deliberate method of navigating through the scholarly landscape by tracking how cited works are propagated by scholars over time . Aside from citing sources, other academic conventions to follow include the appropriate use of headings and subheadings, properly spelling out acronyms when first used in the text, avoiding slang or colloquial language, avoiding emotive language or unsupported declarative statements, avoiding contractions [e.g., isn't], and using first person and second person pronouns only when necessary.

VII. Evidence-Based Reasoning Assignments often ask you to express your own point of view about the research problem. However, what is valued in academic writing is that statements are based on evidence-based reasoning. This refers to possessing a clear understanding of the pertinent body of knowledge and academic debates that exist within, and often external to, your discipline concerning the topic. You need to support your arguments with evidence from scholarly [i.e., academic or peer-reviewed] sources. It should be an objective stance presented as a logical argument; the quality of the evidence you cite will determine the strength of your argument. The objective is to convince the reader of the validity of your thoughts through a well-documented, coherent, and logically structured piece of writing. This is particularly important when proposing solutions to problems or delineating recommended courses of action.

VIII. Thesis-Driven Academic writing is “thesis-driven,” meaning that the starting point is a particular perspective, idea, or position applied to the chosen topic of investigation, such as, establishing, proving, or disproving solutions to the questions applied to investigating the research problem. Note that a problem statement without the research questions does not qualify as academic writing because simply identifying the research problem does not establish for the reader how you will contribute to solving the problem, what aspects you believe are most critical, or suggest a method for gathering information or data to better understand the problem.

IX. Complexity and Higher-Order Thinking Academic writing addresses complex issues that require higher-order thinking skills applied to understanding the research problem [e.g., critical, reflective, logical, and creative thinking as opposed to, for example, descriptive or prescriptive thinking]. Higher-order thinking skills include cognitive processes that are used to comprehend, solve problems, and express concepts or that describe abstract ideas that cannot be easily acted out, pointed to, or shown with images. Think of your writing this way: One of the most important attributes of a good teacher is the ability to explain complexity in a way that is understandable and relatable to the topic being presented during class. This is also one of the main functions of academic writing--examining and explaining the significance of complex ideas as clearly as possible. As a writer, you must adopt the role of a good teacher by summarizing complex information into a well-organized synthesis of ideas, concepts, and recommendations that contribute to a better understanding of the research problem.

Academic Writing. Writing Center. Colorado Technical College; Hartley, James. Academic Writing and Publishing: A Practical Guide . New York: Routledge, 2008; Murray, Rowena and Sarah Moore. The Handbook of Academic Writing: A Fresh Approach . New York: Open University Press, 2006; Johnson, Roy. Improve Your Writing Skills . Manchester, UK: Clifton Press, 1995; Nygaard, Lynn P. Writing for Scholars: A Practical Guide to Making Sense and Being Heard . Second edition. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2015; Silvia, Paul J. How to Write a Lot: A Practical Guide to Productive Academic Writing . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2007; Style, Diction, Tone, and Voice. Writing Center, Wheaton College; Sword, Helen. Stylish Academic Writing . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012.

Strategies for...

Understanding Academic Writing and Its Jargon

The very definition of research jargon is language specific to a particular community of practitioner-researchers . Therefore, in modern university life, jargon represents the specific language and meaning assigned to words and phrases specific to a discipline or area of study. For example, the idea of being rational may hold the same general meaning in both political science and psychology, but its application to understanding and explaining phenomena within the research domain of a each discipline may have subtle differences based upon how scholars in that discipline apply the concept to the theories and practice of their work.

Given this, it is important that specialist terminology [i.e., jargon] must be used accurately and applied under the appropriate conditions . Subject-specific dictionaries are the best places to confirm the meaning of terms within the context of a specific discipline. These can be found by either searching in the USC Libraries catalog by entering the disciplinary and the word dictionary [e.g., sociology and dictionary] or using a database such as Credo Reference [a curated collection of subject encyclopedias, dictionaries, handbooks, guides from highly regarded publishers] . It is appropriate for you to use specialist language within your field of study, but you should avoid using such language when writing for non-academic or general audiences.

Problems with Opaque Writing

A common criticism of scholars is that they can utilize needlessly complex syntax or overly expansive vocabulary that is impenetrable or not well-defined. When writing, avoid problems associated with opaque writing by keeping in mind the following:

1. Excessive use of specialized terminology . Yes, it is appropriate for you to use specialist language and a formal style of expression in academic writing, but it does not mean using "big words" just for the sake of doing so. Overuse of complex or obscure words or writing complicated sentence constructions gives readers the impression that your paper is more about style than substance; it leads the reader to question if you really know what you are talking about. Focus on creating clear, concise, and elegant prose that minimizes reliance on specialized terminology.

2. Inappropriate use of specialized terminology . Because you are dealing with concepts, research, and data within your discipline, you need to use the technical language appropriate to that area of study. However, nothing will undermine the validity of your study quicker than the inappropriate application of a term or concept. Avoid using terms whose meaning you are unsure of--do not just guess or assume! Consult the meaning of terms in specialized, discipline-specific dictionaries by searching the USC Libraries catalog or the Credo Reference database [see above].

Additional Problems to Avoid

In addition to understanding the use of specialized language, there are other aspects of academic writing in the social sciences that you should be aware of. These problems include:

- Personal nouns . Excessive use of personal nouns [e.g., I, me, you, us] may lead the reader to believe the study was overly subjective. These words can be interpreted as being used only to avoid presenting empirical evidence about the research problem. Limit the use of personal nouns to descriptions of things you actually did [e.g., "I interviewed ten teachers about classroom management techniques..."]. Note that personal nouns are generally found in the discussion section of a paper because this is where you as the author/researcher interpret and describe your work.

- Directives . Avoid directives that demand the reader to "do this" or "do that." Directives should be framed as evidence-based recommendations or goals leading to specific outcomes. Note that an exception to this can be found in various forms of action research that involve evidence-based advocacy for social justice or transformative change. Within this area of the social sciences, authors may offer directives for action in a declarative tone of urgency.

- Informal, conversational tone using slang and idioms . Academic writing relies on excellent grammar and precise word structure. Your narrative should not include regional dialects or slang terms because they can be open to interpretation. Your writing should be direct and concise using standard English.

- Wordiness. Focus on being concise, straightforward, and developing a narrative that does not have confusing language . By doing so, you help eliminate the possibility of the reader misinterpreting the design and purpose of your study.

- Vague expressions (e.g., "they," "we," "people," "the company," "that area," etc.). Being concise in your writing also includes avoiding vague references to persons, places, or things. While proofreading your paper, be sure to look for and edit any vague or imprecise statements that lack context or specificity.

- Numbered lists and bulleted items . The use of bulleted items or lists should be used only if the narrative dictates a need for clarity. For example, it is fine to state, "The four main problems with hedge funds are:" and then list them as 1, 2, 3, 4. However, in academic writing, this must then be followed by detailed explanation and analysis of each item. Given this, the question you should ask yourself while proofreading is: why begin with a list in the first place rather than just starting with systematic analysis of each item arranged in separate paragraphs? Also, be careful using numbers because they can imply a ranked order of priority or importance. If none exists, use bullets and avoid checkmarks or other symbols.

- Descriptive writing . Describing a research problem is an important means of contextualizing a study. In fact, some description or background information may be needed because you can not assume the reader knows the key aspects of the topic. However, the content of your paper should focus on methodology, the analysis and interpretation of findings, and their implications as they apply to the research problem rather than background information and descriptions of tangential issues.

- Personal experience. Drawing upon personal experience [e.g., traveling abroad; caring for someone with Alzheimer's disease] can be an effective way of introducing the research problem or engaging your readers in understanding its significance. Use personal experience only as an example, though, because academic writing relies on evidence-based research. To do otherwise is simply story-telling.

NOTE: Rules concerning excellent grammar and precise word structure do not apply when quoting someone. A quote should be inserted in the text of your paper exactly as it was stated. If the quote is especially vague or hard to understand, consider paraphrasing it or using a different quote to convey the same meaning. Consider inserting the term "sic" in brackets after the quoted text to indicate that the quotation has been transcribed exactly as found in the original source, but the source had grammar, spelling, or other errors. The adverb sic informs the reader that the errors are not yours.

Academic Writing. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Academic Writing Style. First-Year Seminar Handbook. Mercer University; Bem, Daryl J. Writing the Empirical Journal Article. Cornell University; College Writing. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Murray, Rowena and Sarah Moore. The Handbook of Academic Writing: A Fresh Approach . New York: Open University Press, 2006; Johnson, Eileen S. “Action Research.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education . Edited by George W. Noblit and Joseph R. Neikirk. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020); Oppenheimer, Daniel M. "Consequences of Erudite Vernacular Utilized Irrespective of Necessity: Problems with Using Long Words Needlessly." Applied Cognitive Psychology 20 (2006): 139-156; Ezza, El-Sadig Y. and Touria Drid. T eaching Academic Writing as a Discipline-Specific Skill in Higher Education . Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 2020; Pernawan, Ari. Common Flaws in Students' Research Proposals. English Education Department. Yogyakarta State University; Style. College Writing. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Invention: Five Qualities of Good Writing. The Reading/Writing Center. Hunter College; Sword, Helen. Stylish Academic Writing . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012; What Is an Academic Paper? Institute for Writing Rhetoric. Dartmouth College.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Improving Academic Writing

To improve your academic writing skills, you should focus your efforts on three key areas: 1. Clear Writing . The act of thinking about precedes the process of writing about. Good writers spend sufficient time distilling information and reviewing major points from the literature they have reviewed before creating their work. Writing detailed outlines can help you clearly organize your thoughts. Effective academic writing begins with solid planning, so manage your time carefully. 2. Excellent Grammar . Needless to say, English grammar can be difficult and complex; even the best scholars take many years before they have a command of the major points of good grammar. Take the time to learn the major and minor points of good grammar. Spend time practicing writing and seek detailed feedback from professors. Take advantage of the Writing Center on campus if you need help. Proper punctuation and good proofreading skills can significantly improve academic writing [see sub-tab for proofreading you paper ].

Refer to these three basic resources to help your grammar and writing skills:

- A good writing reference book, such as, Strunk and White’s book, The Elements of Style or the St. Martin's Handbook ;

- A college-level dictionary, such as, Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary ;

- The latest edition of Roget's Thesaurus in Dictionary Form .

3. Consistent Stylistic Approach . Whether your professor expresses a preference to use MLA, APA or the Chicago Manual of Style or not, choose one style manual and stick to it. Each of these style manuals provide rules on how to write out numbers, references, citations, footnotes, and lists. Consistent adherence to a style of writing helps with the narrative flow of your paper and improves its readability. Note that some disciplines require a particular style [e.g., education uses APA] so as you write more papers within your major, your familiarity with it will improve.

II. Evaluating Quality of Writing

A useful approach for evaluating the quality of your academic writing is to consider the following issues from the perspective of the reader. While proofreading your final draft, critically assess the following elements in your writing.

- It is shaped around one clear research problem, and it explains what that problem is from the outset.

- Your paper tells the reader why the problem is important and why people should know about it.

- You have accurately and thoroughly informed the reader what has already been published about this problem or others related to it and noted important gaps in the research.

- You have provided evidence to support your argument that the reader finds convincing.

- The paper includes a description of how and why particular evidence was collected and analyzed, and why specific theoretical arguments or concepts were used.

- The paper is made up of paragraphs, each containing only one controlling idea.

- You indicate how each section of the paper addresses the research problem.

- You have considered counter-arguments or counter-examples where they are relevant.

- Arguments, evidence, and their significance have been presented in the conclusion.

- Limitations of your research have been explained as evidence of the potential need for further study.

- The narrative flows in a clear, accurate, and well-organized way.

Boscoloa, Pietro, Barbara Arféb, and Mara Quarisaa. “Improving the Quality of Students' Academic Writing: An Intervention Study.” Studies in Higher Education 32 (August 2007): 419-438; Academic Writing. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Academic Writing Style. First-Year Seminar Handbook. Mercer University; Bem, Daryl J. Writing the Empirical Journal Article. Cornell University; Candlin, Christopher. Academic Writing Step-By-Step: A Research-based Approach . Bristol, CT: Equinox Publishing Ltd., 2016; College Writing. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Style . College Writing. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Invention: Five Qualities of Good Writing. The Reading/Writing Center. Hunter College; Sword, Helen. Stylish Academic Writing . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012; What Is an Academic Paper? Institute for Writing Rhetoric. Dartmouth College.

Writing Tip

Considering the Passive Voice in Academic Writing

In the English language, we are able to construct sentences in the following way: 1. "The policies of Congress caused the economic crisis." 2. "The economic crisis was caused by the policies of Congress."

The decision about which sentence to use is governed by whether you want to focus on “Congress” and what they did, or on “the economic crisis” and what caused it. This choice in focus is achieved with the use of either the active or the passive voice. When you want your readers to focus on the "doer" of an action, you can make the "doer"' the subject of the sentence and use the active form of the verb. When you want readers to focus on the person, place, or thing affected by the action, or the action itself, you can make the effect or the action the subject of the sentence by using the passive form of the verb.

Often in academic writing, scholars don't want to focus on who is doing an action, but on who is receiving or experiencing the consequences of that action. The passive voice is useful in academic writing because it allows writers to highlight the most important participants or events within sentences by placing them at the beginning of the sentence.

Use the passive voice when:

- You want to focus on the person, place, or thing affected by the action, or the action itself;

- It is not important who or what did the action;

- You want to be impersonal or more formal.

Form the passive voice by:

- Turning the object of the active sentence into the subject of the passive sentence.

- Changing the verb to a passive form by adding the appropriate form of the verb "to be" and the past participle of the main verb.

NOTE: Consult with your professor about using the passive voice before submitting your research paper. Some strongly discourage its use!

Active and Passive Voice. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Diefenbach, Paul. Future of Digital Media Syllabus. Drexel University; Passive Voice. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina.

- << Previous: 2. Preparing to Write

- Next: Applying Critical Thinking >>

- Last Updated: May 30, 2024 9:38 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

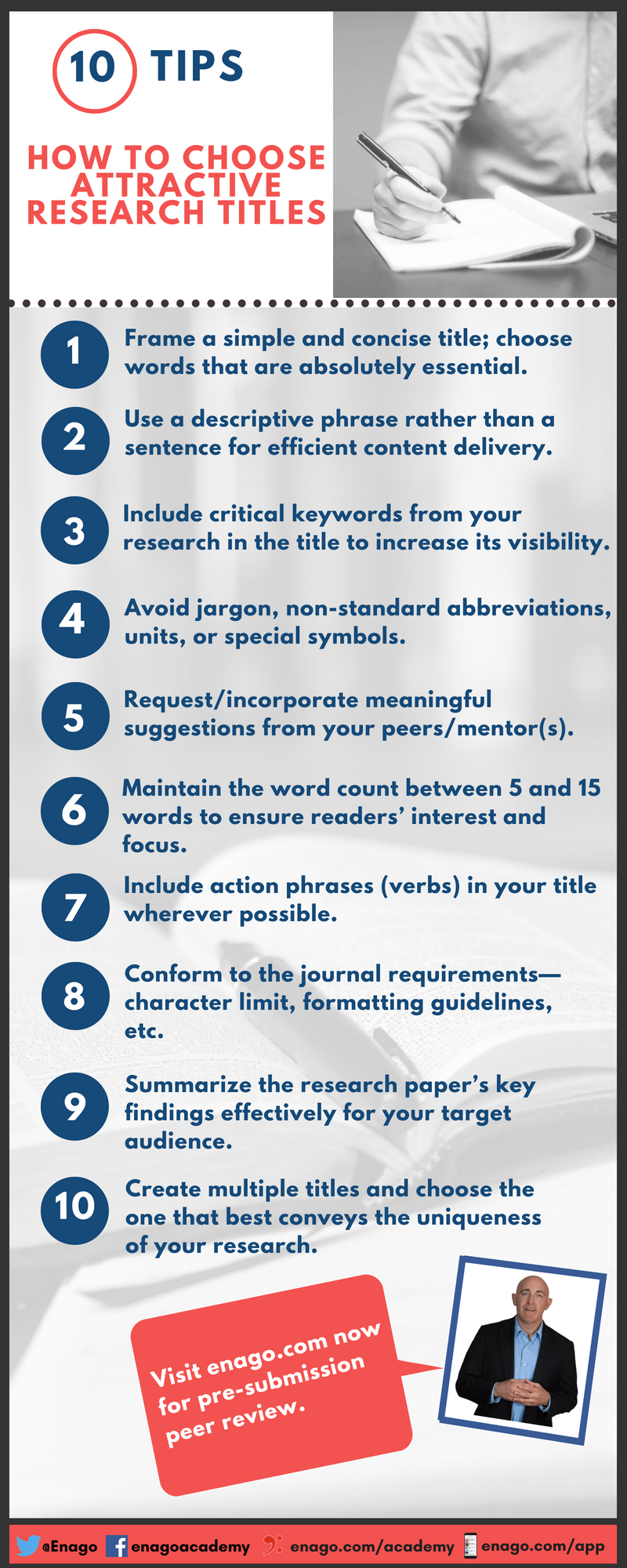

Writing a Good Research Title: Things to Avoid

When writing manuscripts , too many scholars neglect the research title. This phrase, along with the abstract, is what people will mostly see and read online. Title research of publications shows that the research paper title does matter a lot . Both bibliometrics and altmetrics tracking of citations are now, for better or worse, used to gauge a paper’s “success” for its author(s) and the journal publishing it. Interesting research topics coupled with good or clever yet accurate research titles can draw more attention to your work from peers and the public alike.

It would be helpful to have a list of what should never go into the title of a journal article. With this “don’ts” list, authors could have a handy tool to maximize the impact of their research. Titles for research manuscripts need not be complex. It can even have style. They can state the main result or idea of the paper (i.e., declarative). Alternatively, they can indicate the subject covered by the paper (i.e., descriptive). A third form, which should be used sparingly, conveys the research in the form of an open question.

A Handy List of Don’ts

- The period generally has no place in a title (even a declarative phrase can work without a period)

- Likewise, any kind of dashes to separates title parts (however, hyphens to link words is fine)

- Chemical formula, like H 2 O, CH 4 , etc. (instead use their common or generic names)

- Avoid roman numerals (e.g., III, IX, etc.)

- Semi-colons, as in “;” (the colon, however, is very useful to make two-part titles)

- The taxonomic hierarchy of species of plants, animals, fungi, etc. is not needed

- Abbreviations (except for RNA, DNA which is standard now and widely known)

- Initialisms and acronyms (e.g., “Ca” may get confused with CA, which denotes cancer)

- Avoid question marks (this tends to decrease citations, but posing a question is useful in economics and philosophy papers or when the results are not so clear-cut as hoped for)

- Uncommon words (a few are okay, but too many can influence altmetric scoring)