Places on our 2024 summer school are filling fast. Don’t miss out. Enrol now to avoid disappointment

- 40 Useful Words and Phrases for Top-Notch Essays

To be truly brilliant, an essay needs to utilise the right language. You could make a great point, but if it’s not intelligently articulated, you almost needn’t have bothered.

Developing the language skills to build an argument and to write persuasively is crucial if you’re to write outstanding essays every time. In this article, we’re going to equip you with the words and phrases you need to write a top-notch essay, along with examples of how to utilise them.

It’s by no means an exhaustive list, and there will often be other ways of using the words and phrases we describe that we won’t have room to include, but there should be more than enough below to help you make an instant improvement to your essay-writing skills.

If you’re interested in developing your language and persuasive skills, Oxford Royale offers summer courses at its Oxford Summer School , Cambridge Summer School , London Summer School , San Francisco Summer School and Yale Summer School . You can study courses to learn english , prepare for careers in law , medicine , business , engineering and leadership.

General explaining

Let’s start by looking at language for general explanations of complex points.

1. In order to

Usage: “In order to” can be used to introduce an explanation for the purpose of an argument. Example: “In order to understand X, we need first to understand Y.”

2. In other words

Usage: Use “in other words” when you want to express something in a different way (more simply), to make it easier to understand, or to emphasise or expand on a point. Example: “Frogs are amphibians. In other words, they live on the land and in the water.”

3. To put it another way

Usage: This phrase is another way of saying “in other words”, and can be used in particularly complex points, when you feel that an alternative way of wording a problem may help the reader achieve a better understanding of its significance. Example: “Plants rely on photosynthesis. To put it another way, they will die without the sun.”

4. That is to say

Usage: “That is” and “that is to say” can be used to add further detail to your explanation, or to be more precise. Example: “Whales are mammals. That is to say, they must breathe air.”

5. To that end

Usage: Use “to that end” or “to this end” in a similar way to “in order to” or “so”. Example: “Zoologists have long sought to understand how animals communicate with each other. To that end, a new study has been launched that looks at elephant sounds and their possible meanings.”

Adding additional information to support a point

Students often make the mistake of using synonyms of “and” each time they want to add further information in support of a point they’re making, or to build an argument . Here are some cleverer ways of doing this.

6. Moreover

Usage: Employ “moreover” at the start of a sentence to add extra information in support of a point you’re making. Example: “Moreover, the results of a recent piece of research provide compelling evidence in support of…”

7. Furthermore

Usage:This is also generally used at the start of a sentence, to add extra information. Example: “Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that…”

8. What’s more

Usage: This is used in the same way as “moreover” and “furthermore”. Example: “What’s more, this isn’t the only evidence that supports this hypothesis.”

9. Likewise

Usage: Use “likewise” when you want to talk about something that agrees with what you’ve just mentioned. Example: “Scholar A believes X. Likewise, Scholar B argues compellingly in favour of this point of view.”

10. Similarly

Usage: Use “similarly” in the same way as “likewise”. Example: “Audiences at the time reacted with shock to Beethoven’s new work, because it was very different to what they were used to. Similarly, we have a tendency to react with surprise to the unfamiliar.”

11. Another key thing to remember

Usage: Use the phrase “another key point to remember” or “another key fact to remember” to introduce additional facts without using the word “also”. Example: “As a Romantic, Blake was a proponent of a closer relationship between humans and nature. Another key point to remember is that Blake was writing during the Industrial Revolution, which had a major impact on the world around him.”

12. As well as

Usage: Use “as well as” instead of “also” or “and”. Example: “Scholar A argued that this was due to X, as well as Y.”

13. Not only… but also

Usage: This wording is used to add an extra piece of information, often something that’s in some way more surprising or unexpected than the first piece of information. Example: “Not only did Edmund Hillary have the honour of being the first to reach the summit of Everest, but he was also appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire.”

14. Coupled with

Usage: Used when considering two or more arguments at a time. Example: “Coupled with the literary evidence, the statistics paint a compelling view of…”

15. Firstly, secondly, thirdly…

Usage: This can be used to structure an argument, presenting facts clearly one after the other. Example: “There are many points in support of this view. Firstly, X. Secondly, Y. And thirdly, Z.

16. Not to mention/to say nothing of

Usage: “Not to mention” and “to say nothing of” can be used to add extra information with a bit of emphasis. Example: “The war caused unprecedented suffering to millions of people, not to mention its impact on the country’s economy.”

Words and phrases for demonstrating contrast

When you’re developing an argument, you will often need to present contrasting or opposing opinions or evidence – “it could show this, but it could also show this”, or “X says this, but Y disagrees”. This section covers words you can use instead of the “but” in these examples, to make your writing sound more intelligent and interesting.

17. However

Usage: Use “however” to introduce a point that disagrees with what you’ve just said. Example: “Scholar A thinks this. However, Scholar B reached a different conclusion.”

18. On the other hand

Usage: Usage of this phrase includes introducing a contrasting interpretation of the same piece of evidence, a different piece of evidence that suggests something else, or an opposing opinion. Example: “The historical evidence appears to suggest a clear-cut situation. On the other hand, the archaeological evidence presents a somewhat less straightforward picture of what happened that day.”

19. Having said that

Usage: Used in a similar manner to “on the other hand” or “but”. Example: “The historians are unanimous in telling us X, an agreement that suggests that this version of events must be an accurate account. Having said that, the archaeology tells a different story.”

20. By contrast/in comparison

Usage: Use “by contrast” or “in comparison” when you’re comparing and contrasting pieces of evidence. Example: “Scholar A’s opinion, then, is based on insufficient evidence. By contrast, Scholar B’s opinion seems more plausible.”

21. Then again

Usage: Use this to cast doubt on an assertion. Example: “Writer A asserts that this was the reason for what happened. Then again, it’s possible that he was being paid to say this.”

22. That said

Usage: This is used in the same way as “then again”. Example: “The evidence ostensibly appears to point to this conclusion. That said, much of the evidence is unreliable at best.”

Usage: Use this when you want to introduce a contrasting idea. Example: “Much of scholarship has focused on this evidence. Yet not everyone agrees that this is the most important aspect of the situation.”

Adding a proviso or acknowledging reservations

Sometimes, you may need to acknowledge a shortfalling in a piece of evidence, or add a proviso. Here are some ways of doing so.

24. Despite this

Usage: Use “despite this” or “in spite of this” when you want to outline a point that stands regardless of a shortfalling in the evidence. Example: “The sample size was small, but the results were important despite this.”

25. With this in mind

Usage: Use this when you want your reader to consider a point in the knowledge of something else. Example: “We’ve seen that the methods used in the 19th century study did not always live up to the rigorous standards expected in scientific research today, which makes it difficult to draw definite conclusions. With this in mind, let’s look at a more recent study to see how the results compare.”

26. Provided that

Usage: This means “on condition that”. You can also say “providing that” or just “providing” to mean the same thing. Example: “We may use this as evidence to support our argument, provided that we bear in mind the limitations of the methods used to obtain it.”

27. In view of/in light of

Usage: These phrases are used when something has shed light on something else. Example: “In light of the evidence from the 2013 study, we have a better understanding of…”

28. Nonetheless

Usage: This is similar to “despite this”. Example: “The study had its limitations, but it was nonetheless groundbreaking for its day.”

29. Nevertheless

Usage: This is the same as “nonetheless”. Example: “The study was flawed, but it was important nevertheless.”

30. Notwithstanding

Usage: This is another way of saying “nonetheless”. Example: “Notwithstanding the limitations of the methodology used, it was an important study in the development of how we view the workings of the human mind.”

Giving examples

Good essays always back up points with examples, but it’s going to get boring if you use the expression “for example” every time. Here are a couple of other ways of saying the same thing.

31. For instance

Example: “Some birds migrate to avoid harsher winter climates. Swallows, for instance, leave the UK in early winter and fly south…”

32. To give an illustration

Example: “To give an illustration of what I mean, let’s look at the case of…”

Signifying importance

When you want to demonstrate that a point is particularly important, there are several ways of highlighting it as such.

33. Significantly

Usage: Used to introduce a point that is loaded with meaning that might not be immediately apparent. Example: “Significantly, Tacitus omits to tell us the kind of gossip prevalent in Suetonius’ accounts of the same period.”

34. Notably

Usage: This can be used to mean “significantly” (as above), and it can also be used interchangeably with “in particular” (the example below demonstrates the first of these ways of using it). Example: “Actual figures are notably absent from Scholar A’s analysis.”

35. Importantly

Usage: Use “importantly” interchangeably with “significantly”. Example: “Importantly, Scholar A was being employed by X when he wrote this work, and was presumably therefore under pressure to portray the situation more favourably than he perhaps might otherwise have done.”

Summarising

You’ve almost made it to the end of the essay, but your work isn’t over yet. You need to end by wrapping up everything you’ve talked about, showing that you’ve considered the arguments on both sides and reached the most likely conclusion. Here are some words and phrases to help you.

36. In conclusion

Usage: Typically used to introduce the concluding paragraph or sentence of an essay, summarising what you’ve discussed in a broad overview. Example: “In conclusion, the evidence points almost exclusively to Argument A.”

37. Above all

Usage: Used to signify what you believe to be the most significant point, and the main takeaway from the essay. Example: “Above all, it seems pertinent to remember that…”

38. Persuasive

Usage: This is a useful word to use when summarising which argument you find most convincing. Example: “Scholar A’s point – that Constanze Mozart was motivated by financial gain – seems to me to be the most persuasive argument for her actions following Mozart’s death.”

39. Compelling

Usage: Use in the same way as “persuasive” above. Example: “The most compelling argument is presented by Scholar A.”

40. All things considered

Usage: This means “taking everything into account”. Example: “All things considered, it seems reasonable to assume that…”

How many of these words and phrases will you get into your next essay? And are any of your favourite essay terms missing from our list? Let us know in the comments below, or get in touch here to find out more about courses that can help you with your essays.

At Oxford Royale Academy, we offer a number of summer school courses for young people who are keen to improve their essay writing skills. Click here to apply for one of our courses today, including law , business , medicine and engineering .

Comments are closed.

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

Words to Use in an Essay: 300 Essay Words

Hannah Yang

Table of Contents

Words to use in the essay introduction, words to use in the body of the essay, words to use in your essay conclusion, how to improve your essay writing vocabulary.

It’s not easy to write an academic essay .

Many students struggle to word their arguments in a logical and concise way.

To make matters worse, academic essays need to adhere to a certain level of formality, so we can’t always use the same word choices in essay writing that we would use in daily life.

If you’re struggling to choose the right words for your essay, don’t worry—you’ve come to the right place!

In this article, we’ve compiled a list of over 300 words and phrases to use in the introduction, body, and conclusion of your essay.

The introduction is one of the hardest parts of an essay to write.

You have only one chance to make a first impression, and you want to hook your reader. If the introduction isn’t effective, the reader might not even bother to read the rest of the essay.

That’s why it’s important to be thoughtful and deliberate with the words you choose at the beginning of your essay.

Many students use a quote in the introductory paragraph to establish credibility and set the tone for the rest of the essay.

When you’re referencing another author or speaker, try using some of these phrases:

To use the words of X

According to X

As X states

Example: To use the words of Hillary Clinton, “You cannot have maternal health without reproductive health.”

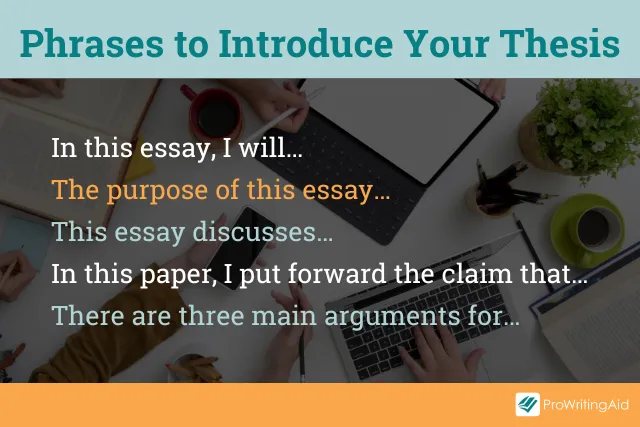

Near the end of the introduction, you should state the thesis to explain the central point of your paper.

If you’re not sure how to introduce your thesis, try using some of these phrases:

In this essay, I will…

The purpose of this essay…

This essay discusses…

In this paper, I put forward the claim that…

There are three main arguments for…

Example: In this essay, I will explain why dress codes in public schools are detrimental to students.

After you’ve stated your thesis, it’s time to start presenting the arguments you’ll use to back up that central idea.

When you’re introducing the first of a series of arguments, you can use the following words:

First and foremost

First of all

To begin with

Example: First , consider the effects that this new social security policy would have on low-income taxpayers.

All these words and phrases will help you create a more successful introduction and convince your audience to read on.

The body of your essay is where you’ll explain your core arguments and present your evidence.

It’s important to choose words and phrases for the body of your essay that will help the reader understand your position and convince them you’ve done your research.

Let’s look at some different types of words and phrases that you can use in the body of your essay, as well as some examples of what these words look like in a sentence.

Transition Words and Phrases

Transitioning from one argument to another is crucial for a good essay.

It’s important to guide your reader from one idea to the next so they don’t get lost or feel like you’re jumping around at random.

Transition phrases and linking words show your reader you’re about to move from one argument to the next, smoothing out their reading experience. They also make your writing look more professional.

The simplest transition involves moving from one idea to a separate one that supports the same overall argument. Try using these phrases when you want to introduce a second correlating idea:

Additionally

In addition

Furthermore

Another key thing to remember

In the same way

Correspondingly

Example: Additionally , public parks increase property value because home buyers prefer houses that are located close to green, open spaces.

Another type of transition involves restating. It’s often useful to restate complex ideas in simpler terms to help the reader digest them. When you’re restating an idea, you can use the following words:

In other words

To put it another way

That is to say

To put it more simply

Example: “The research showed that 53% of students surveyed expressed a mild or strong preference for more on-campus housing. In other words , over half the students wanted more dormitory options.”

Often, you’ll need to provide examples to illustrate your point more clearly for the reader. When you’re about to give an example of something you just said, you can use the following words:

For instance

To give an illustration of

To exemplify

To demonstrate

As evidence

Example: Humans have long tried to exert control over our natural environment. For instance , engineers reversed the Chicago River in 1900, causing it to permanently flow backward.

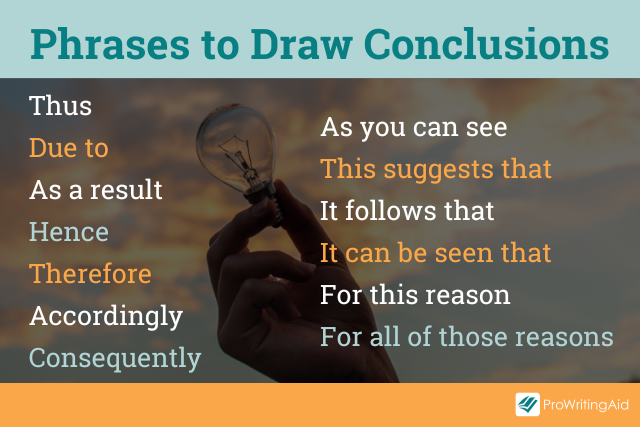

Sometimes, you’ll need to explain the impact or consequence of something you’ve just said.

When you’re drawing a conclusion from evidence you’ve presented, try using the following words:

As a result

Accordingly

As you can see

This suggests that

It follows that

It can be seen that

For this reason

For all of those reasons

Consequently

Example: “There wasn’t enough government funding to support the rest of the physics experiment. Thus , the team was forced to shut down their experiment in 1996.”

When introducing an idea that bolsters one you’ve already stated, or adds another important aspect to that same argument, you can use the following words:

What’s more

Not only…but also

Not to mention

To say nothing of

Another key point

Example: The volcanic eruption disrupted hundreds of thousands of people. Moreover , it impacted the local flora and fauna as well, causing nearly a hundred species to go extinct.

Often, you'll want to present two sides of the same argument. When you need to compare and contrast ideas, you can use the following words:

On the one hand / on the other hand

Alternatively

In contrast to

On the contrary

By contrast

In comparison

Example: On the one hand , the Black Death was undoubtedly a tragedy because it killed millions of Europeans. On the other hand , it created better living conditions for the peasants who survived.

Finally, when you’re introducing a new angle that contradicts your previous idea, you can use the following phrases:

Having said that

Differing from

In spite of

With this in mind

Provided that

Nevertheless

Nonetheless

Notwithstanding

Example: Shakespearean plays are classic works of literature that have stood the test of time. Having said that , I would argue that Shakespeare isn’t the most accessible form of literature to teach students in the twenty-first century.

Good essays include multiple types of logic. You can use a combination of the transitions above to create a strong, clear structure throughout the body of your essay.

Strong Verbs for Academic Writing

Verbs are especially important for writing clear essays. Often, you can convey a nuanced meaning simply by choosing the right verb.

You should use strong verbs that are precise and dynamic. Whenever possible, you should use an unambiguous verb, rather than a generic verb.

For example, alter and fluctuate are stronger verbs than change , because they give the reader more descriptive detail.

Here are some useful verbs that will help make your essay shine.

Verbs that show change:

Accommodate

Verbs that relate to causing or impacting something:

Verbs that show increase:

Verbs that show decrease:

Deteriorate

Verbs that relate to parts of a whole:

Comprises of

Is composed of

Constitutes

Encompasses

Incorporates

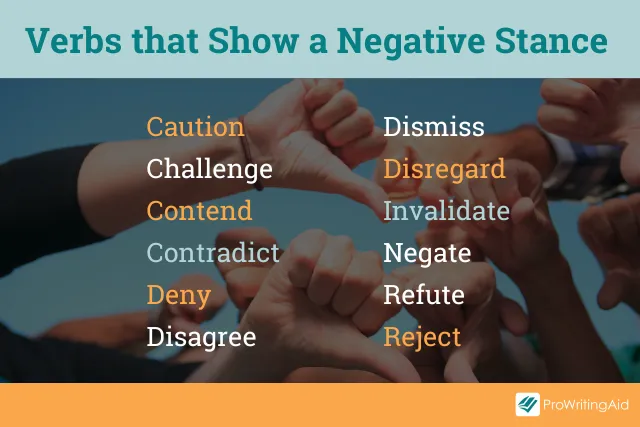

Verbs that show a negative stance:

Misconstrue

Verbs that show a positive stance:

Substantiate

Verbs that relate to drawing conclusions from evidence:

Corroborate

Demonstrate

Verbs that relate to thinking and analysis:

Contemplate

Hypothesize

Investigate

Verbs that relate to showing information in a visual format:

Useful Adjectives and Adverbs for Academic Essays

You should use adjectives and adverbs more sparingly than verbs when writing essays, since they sometimes add unnecessary fluff to sentences.

However, choosing the right adjectives and adverbs can help add detail and sophistication to your essay.

Sometimes you'll need to use an adjective to show that a finding or argument is useful and should be taken seriously. Here are some adjectives that create positive emphasis:

Significant

Other times, you'll need to use an adjective to show that a finding or argument is harmful or ineffective. Here are some adjectives that create a negative emphasis:

Controversial

Insignificant

Questionable

Unnecessary

Unrealistic

Finally, you might need to use an adverb to lend nuance to a sentence, or to express a specific degree of certainty. Here are some examples of adverbs that are often used in essays:

Comprehensively

Exhaustively

Extensively

Respectively

Surprisingly

Using these words will help you successfully convey the key points you want to express. Once you’ve nailed the body of your essay, it’s time to move on to the conclusion.

The conclusion of your paper is important for synthesizing the arguments you’ve laid out and restating your thesis.

In your concluding paragraph, try using some of these essay words:

In conclusion

To summarize

In a nutshell

Given the above

As described

All things considered

Example: In conclusion , it’s imperative that we take action to address climate change before we lose our coral reefs forever.

In addition to simply summarizing the key points from the body of your essay, you should also add some final takeaways. Give the reader your final opinion and a bit of a food for thought.

To place emphasis on a certain point or a key fact, use these essay words:

Unquestionably

Undoubtedly

Particularly

Importantly

Conclusively

It should be noted

On the whole

Example: Ada Lovelace is unquestionably a powerful role model for young girls around the world, and more of our public school curricula should include her as a historical figure.

These concluding phrases will help you finish writing your essay in a strong, confident way.

There are many useful essay words out there that we didn't include in this article, because they are specific to certain topics.

If you're writing about biology, for example, you will need to use different terminology than if you're writing about literature.

So how do you improve your vocabulary skills?

The vocabulary you use in your academic writing is a toolkit you can build up over time, as long as you take the time to learn new words.

One way to increase your vocabulary is by looking up words you don’t know when you’re reading.

Try reading more books and academic articles in the field you’re writing about and jotting down all the new words you find. You can use these words to bolster your own essays.

You can also consult a dictionary or a thesaurus. When you’re using a word you’re not confident about, researching its meaning and common synonyms can help you make sure it belongs in your essay.

Don't be afraid of using simpler words. Good essay writing boils down to choosing the best word to convey what you need to say, not the fanciest word possible.

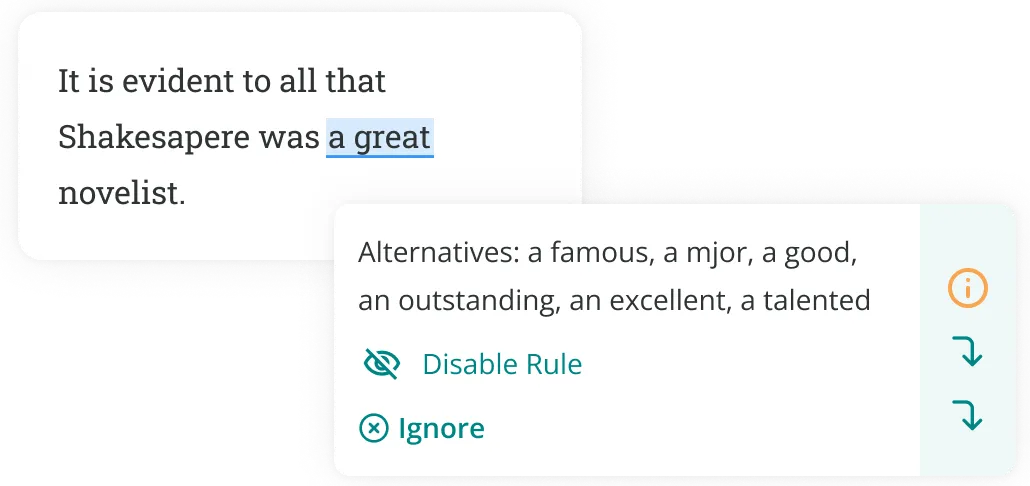

Finally, you can use ProWritingAid’s synonym tool or essay checker to find more precise and sophisticated vocabulary. Click on weak words in your essay to find stronger alternatives.

There you have it: our compilation of the best words and phrases to use in your next essay . Good luck!

Good writing = better grades

ProWritingAid will help you improve the style, strength, and clarity of all your assignments.

Hannah Yang is a speculative fiction writer who writes about all things strange and surreal. Her work has appeared in Analog Science Fiction, Apex Magazine, The Dark, and elsewhere, and two of her stories have been finalists for the Locus Award. Her favorite hobbies include watercolor painting, playing guitar, and rock climbing. You can follow her work on hannahyang.com, or subscribe to her newsletter for publication updates.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Words To Use In Essays: Amplifying Your Academic Writing

Use this comprehensive list of words to use in essays to elevate your writing. Make an impression and score higher grades with this guide!

Words play a fundamental role in the domain of essay writing, as they have the power to shape ideas, influence readers, and convey messages with precision and impact. Choosing the right words to use in essays is not merely a matter of filling pages, but rather a deliberate process aimed at enhancing the quality of the writing and effectively communicating complex ideas. In this article, we will explore the importance of selecting appropriate words for essays and provide valuable insights into the types of words that can elevate the essay to new heights.

Words To Use In Essays

Using a wide range of words can make your essay stronger and more impressive. With the incorporation of carefully chosen words that communicate complex ideas with precision and eloquence, the writer can elevate the quality of their essay and captivate readers.

This list serves as an introduction to a range of impactful words that can be integrated into writing, enabling the writer to express thoughts with depth and clarity.

Significantly

Furthermore

Nonetheless

Nevertheless

Consequently

Accordingly

Subsequently

In contrast

Alternatively

Implications

Substantially

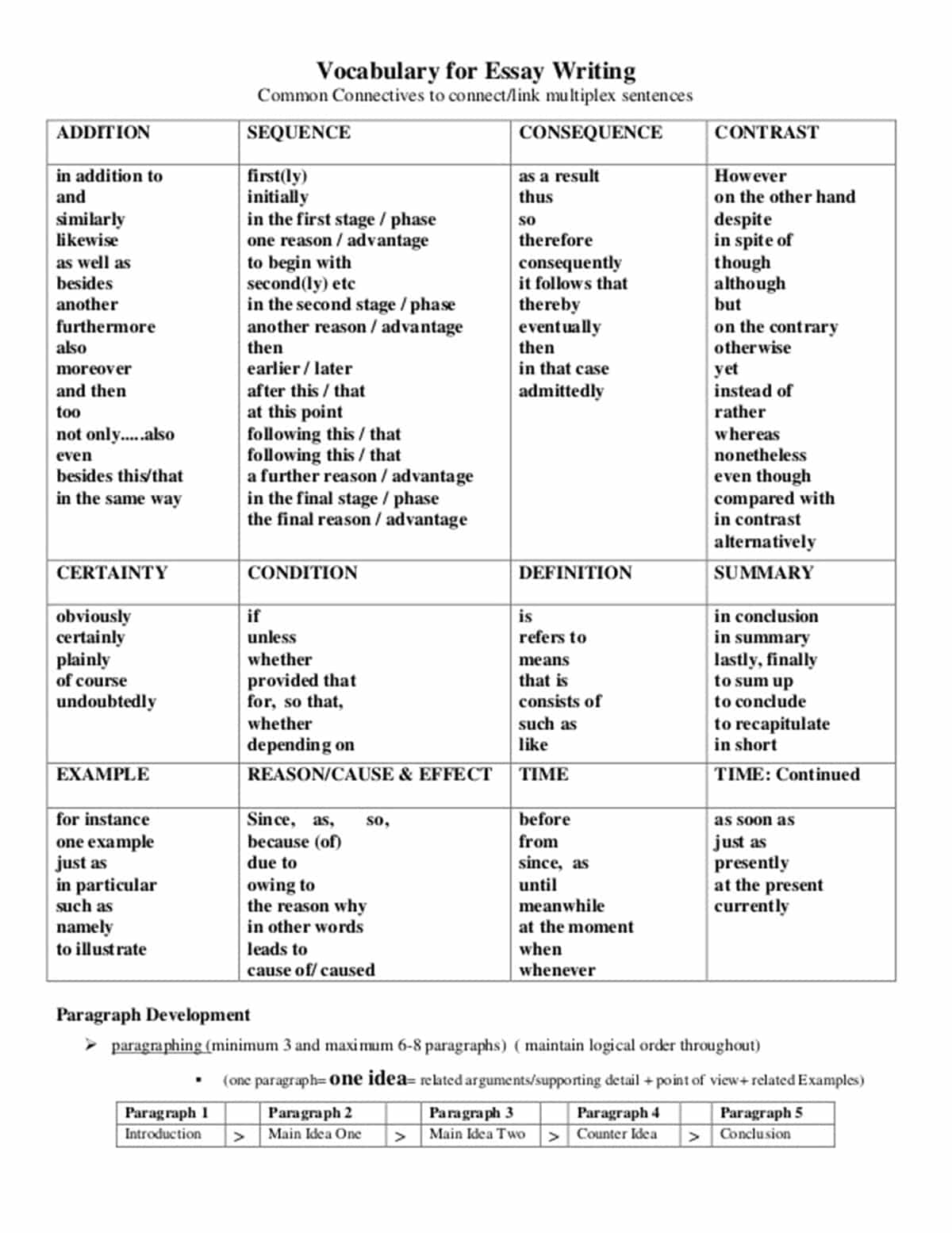

Transition Words And Phrases

Transition words and phrases are essential linguistic tools that connect ideas, sentences, and paragraphs within a text. They work like bridges, facilitating the transitions between different parts of an essay or any other written work. These transitional elements conduct the flow and coherence of the writing, making it easier for readers to follow the author’s train of thought.

Here are some examples of common transition words and phrases:

Furthermore: Additionally; moreover.

However: Nevertheless; on the other hand.

In contrast: On the contrary; conversely.

Therefore: Consequently; as a result.

Similarly: Likewise; in the same way.

Moreover: Furthermore; besides.

In addition: Additionally; also.

Nonetheless: Nevertheless; regardless.

Nevertheless: However; even so.

On the other hand: Conversely; in contrast.

These are just a few examples of the many transition words and phrases available. They help create coherence, improve the organization of ideas, and guide readers through the logical progression of the text. When used effectively, transition words and phrases can significantly guide clarity for writing.

Strong Verbs For Academic Writing

Strong verbs are an essential component of academic writing as they add precision, clarity, and impact to sentences. They convey actions, intentions, and outcomes in a more powerful and concise manner. Here are some examples of strong verbs commonly used in academic writing:

Analyze: Examine in detail to understand the components or structure.

Critique: Assess or evaluate the strengths and weaknesses.

Demonstrate: Show the evidence to support a claim or argument.

Illuminate: Clarify or make something clearer.

Explicate: Explain in detail a thorough interpretation.

Synthesize: Combine or integrate information to create a new understanding.

Propose: Put forward or suggest a theory, idea, or solution.

Refute: Disprove or argue against a claim or viewpoint.

Validate: Confirm or prove the accuracy or validity of something.

Advocate: Support or argue in favor of a particular position or viewpoint.

Adjectives And Adverbs For Academic Essays

Useful adjectives and adverbs are valuable tools in academic writing as they enhance the description, precision, and depth of arguments and analysis. They provide specific details, emphasize key points, and add nuance to writing. Here are some examples of useful adjectives and adverbs commonly used in academic essays:

Comprehensive: Covering all aspects or elements; thorough.

Crucial: Extremely important or essential.

Prominent: Well-known or widely recognized; notable.

Substantial: Considerable in size, extent, or importance.

Valid: Well-founded or logically sound; acceptable or authoritative.

Effectively: In a manner that produces the desired result or outcome.

Significantly: To a considerable extent or degree; notably.

Consequently: As a result or effect of something.

Precisely: Exactly or accurately; with great attention to detail.

Critically: In a careful and analytical manner; with careful evaluation or assessment.

Words To Use In The Essay Introduction

The words used in the essay introduction play a crucial role in capturing the reader’s attention and setting the tone for the rest of the essay. They should be engaging, informative, and persuasive. Here are some examples of words that can be effectively used in the essay introduction:

Intriguing: A word that sparks curiosity and captures the reader’s interest from the beginning.

Compelling: Conveys the idea that the topic is interesting and worth exploring further.

Provocative: Creates a sense of controversy or thought-provoking ideas.

Insightful: Suggests that the essay will produce valuable and thought-provoking insights.

Startling: Indicates that the essay will present surprising or unexpected information or perspectives.

Relevant: Emphasizes the significance of the topic and its connection to broader issues or current events.

Timely: Indicates that the essay addresses a subject of current relevance or importance.

Thoughtful: Implies that the essay will offer well-considered and carefully developed arguments.

Persuasive: Suggests that the essay will present compelling arguments to convince the reader.

Captivating: Indicates that the essay will hold the reader’s attention and be engaging throughout.

Words To Use In The Body Of The Essay

The words used in the body of the essay are essential for effectively conveying ideas, providing evidence, and developing arguments. They should be clear, precise, and demonstrate a strong command of the subject matter. Here are some examples of words that can be used in the body of the essay:

Evidence: When presenting supporting information or data, words such as “data,” “research,” “studies,” “findings,” “examples,” or “statistics” can be used to strengthen arguments.

Analysis: To discuss and interpret the evidence, words like “analyze,” “examine,” “explore,” “interpret,” or “assess” can be employed to demonstrate a critical evaluation of the topic.

Comparison: When drawing comparisons or making contrasts, words like “similarly,” “likewise,” “in contrast,” “on the other hand,” or “conversely” can be used to highlight similarities or differences.

Cause and effect: To explain the relationship between causes and consequences, words such as “because,” “due to,” “leads to,” “results in,” or “causes” can be utilized.

Sequence: When discussing a series of events or steps, words like “first,” “next,” “then,” “finally,” “subsequently,” or “consequently” can be used to indicate the order or progression.

Emphasis: To emphasize a particular point or idea, words such as “notably,” “significantly,” “crucially,” “importantly,” or “remarkably” can be employed.

Clarification: When providing further clarification or elaboration, words like “specifically,” “in other words,” “for instance,” “to illustrate,” or “to clarify” can be used.

Integration: To show the relationship between different ideas or concepts, words such as “moreover,” “furthermore,” “additionally,” “likewise,” or “similarly” can be utilized.

Conclusion: When summarizing or drawing conclusions, words like “in conclusion,” “to summarize,” “overall,” “in summary,” or “to conclude” can be employed to wrap up ideas.

Remember to use these words appropriately and contextually, ensuring they strengthen the coherence and flow of arguments. They should serve as effective transitions and connectors between ideas, enhancing the overall clarity and persuasiveness of the essay.

Words To Use In Essay Conclusion

The words used in the essay conclusion are crucial for effectively summarizing the main points, reinforcing arguments, and leaving a lasting impression on the reader. They should bring a sense of closure to the essay while highlighting the significance of ideas. Here are some examples of words that can be used in the essay conclusion:

Summary: To summarize the main points, these words can be used “in summary,” “to sum up,” “in conclusion,” “to recap,” or “overall.”

Reinforcement: To reinforce arguments and emphasize their importance, words such as “crucial,” “essential,” “significant,” “noteworthy,” or “compelling” can be employed.

Implication: To discuss the broader implications of ideas or findings, words like “consequently,” “therefore,” “thus,” “hence,” or “as a result” can be utilized.

Call to action: If applicable, words that encourage further action or reflection can be used, such as “we must,” “it is essential to,” “let us consider,” or “we should.”

Future perspective: To discuss future possibilities or developments related to the topic, words like “potential,” “future research,” “emerging trends,” or “further investigation” can be employed.

Reflection: To reflect on the significance or impact of arguments, words such as “profound,” “notable,” “thought-provoking,” “transformative,” or “perspective-shifting” can be used.

Final thought: To leave a lasting impression, words or phrases that summarize the main idea or evoke a sense of thoughtfulness can be used, such as “food for thought,” “in light of this,” “to ponder,” or “to consider.”

How To Improve Essay Writing Vocabulary

Improving essay writing vocabulary is essential for effectively expressing ideas, demonstrating a strong command of the language, and engaging readers. Here are some strategies to enhance the essay writing vocabulary:

- Read extensively: Reading a wide range of materials, such as books, articles, and essays, can give various writing styles, topics, and vocabulary. Pay attention to new words and their usage, and try incorporating them into the writing.

- Use a dictionary and thesaurus: Look up unfamiliar words in a dictionary to understand their meanings and usage. Additionally, utilize a thesaurus to find synonyms and antonyms to expand word choices and avoid repetition.

- Create a word bank: To create a word bank, read extensively, write down unfamiliar or interesting words, and explore their meanings and usage. Organize them by categories or themes for easy reference, and practice incorporating them into writing to expand the vocabulary.

- Contextualize vocabulary: Simply memorizing new words won’t be sufficient; it’s crucial to understand their proper usage and context. Pay attention to how words are used in different contexts, sentence structures, and rhetorical devices.

How To Add Additional Information To Support A Point

When writing an essay and wanting to add additional information to support a point, you can use various transitional words and phrases. Here are some examples:

Furthermore: Add more information or evidence to support the previous point.

Additionally: Indicates an additional supporting idea or evidence.

Moreover: Emphasizes the importance or significance of the added information.

In addition: Signals the inclusion of another supporting detail.

Furthermore, it is important to note: Introduces an additional aspect or consideration related to the topic.

Not only that, but also: Highlights an additional point that strengthens the argument.

Equally important: Emphasizes the equal significance of the added information.

Another key point: Introduces another important supporting idea.

It is worth noting: Draws attention to a noteworthy detail that supports the point being made.

Additionally, it is essential to consider: Indicates the need to consider another aspect or perspective.

Using these transitional words and phrases will help you seamlessly integrate additional information into your essay, enhancing the clarity and persuasiveness of your arguments.

Words And Phrases That Demonstrate Contrast

When crafting an essay, it is crucial to effectively showcase contrast, enabling the presentation of opposing ideas or the highlighting of differences between concepts. The adept use of suitable words and phrases allows for the clear communication of contrast, bolstering the strength of arguments. Consider the following examples of commonly employed words and phrases to illustrate the contrast in essays:

However: e.g., “The experiment yielded promising results; however, further analysis is needed to draw conclusive findings.”

On the other hand: e.g., “Some argue for stricter gun control laws, while others, on the other hand, advocate for individual rights to bear arms.”

Conversely: e.g., “While the study suggests a positive correlation between exercise and weight loss, conversely, other research indicates that diet plays a more significant role.”

Nevertheless: e.g., “The data shows a decline in crime rates; nevertheless, public safety remains a concern for many citizens.”

In contrast: e.g., “The economic policies of Country A focus on free-market principles. In contrast, Country B implements more interventionist measures.”

Despite: e.g., “Despite the initial setbacks, the team persevered and ultimately achieved success.”

Although: e.g., “Although the participants had varying levels of experience, they all completed the task successfully.”

While: e.g., “While some argue for stricter regulations, others contend that personal responsibility should prevail.”

Words To Use For Giving Examples

When writing an essay and providing examples to illustrate your points, you can use a variety of words and phrases to introduce those examples. Here are some examples:

For instance: Introduces a specific example to support or illustrate your point.

For example: Give an example to clarify or demonstrate your argument.

Such as: Indicates that you are providing a specific example or examples.

To illustrate: Signals that you are using an example to explain or emphasize your point.

One example is: Introduces a specific instance that exemplifies your argument.

In particular: Highlights a specific example that is especially relevant to your point.

As an illustration: Introduces an example that serves as a visual or concrete representation of your point.

A case in point: Highlights a specific example that serves as evidence or proof of your argument.

To demonstrate: Indicates that you are providing an example to show or prove your point.

To exemplify: Signals that you are using an example to illustrate or clarify your argument.

Using these words and phrases will help you effectively incorporate examples into your essay, making your arguments more persuasive and relatable. Remember to give clear and concise examples that directly support your main points.

Words To Signifying Importance

When writing an essay and wanting to signify the importance of a particular point or idea, you can use various words and phrases to convey this emphasis. Here are some examples:

Crucially: Indicates that the point being made is of critical importance.

Significantly: Highlights the importance or significance of the idea or information.

Importantly: Draws attention to the crucial nature of the point being discussed.

Notably: Emphasizes that the information or idea is particularly worthy of attention.

It is vital to note: Indicates that the point being made is essential and should be acknowledged.

It should be emphasized: Draws attention to the need to give special importance or focus to the point being made.

A key consideration is: Highlight that the particular idea or information is a central aspect of the discussion.

It is critical to recognize: Emphasizes that the understanding or acknowledgment of the point is crucial.

Using these words and phrases will help you convey the importance and significance of specific points or ideas in your essay, ensuring that readers recognize their significance and impact on the overall argument.

Exclusive Scientific Content, Created By Scientists

Mind the Graph platform provides scientists with exclusive scientific content that is created by scientists themselves. This unique feature ensures that the platform offers high-quality and reliable information tailored specifically for the scientific community. The platform serves as a valuable resource for researchers, offering a wide range of visual tools and templates that enable scientists to create impactful and visually engaging scientific illustrations and graphics for their publications, presentations, and educational materials.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Exclusive high quality content about effective visual communication in science.

Unlock Your Creativity

Create infographics, presentations and other scientifically-accurate designs without hassle — absolutely free for 7 days!

Content tags

100+ Useful Words and Phrases to Write a Great Essay

By: Author Sophia

Posted on Last updated: October 25, 2023

Sharing is caring!

How to Write a Great Essay in English! This lesson provides 100+ useful words, transition words and expressions used in writing an essay. Let’s take a look!

The secret to a successful essay doesn’t just lie in the clever things you talk about and the way you structure your points.

Useful Words and Phrases to Write a Great Essay

Overview of an essay.

Useful Phrases for Proficiency Essays

Developing the argument

- The first aspect to point out is that…

- Let us start by considering the facts.

- The novel portrays, deals with, revolves around…

- Central to the novel is…

- The character of xxx embodies/ epitomizes…

The other side of the argument

- It would also be interesting to see…

- One should, nevertheless, consider the problem from another angle.

- Equally relevant to the issue are the questions of…

- The arguments we have presented… suggest that…/ prove that…/ would indicate that…

- From these arguments one must…/ could…/ might… conclude that…

- All of this points to the conclusion that…

- To conclude…

Ordering elements

- Firstly,…/ Secondly,…/ Finally,… (note the comma after all these introductory words.)

- As a final point…

- On the one hand, …. on the other hand…

- If on the one hand it can be said that… the same is not true for…

- The first argument suggests that… whilst the second suggests that…

- There are at least xxx points to highlight.

Adding elements

- Furthermore, one should not forget that…

- In addition to…

- Moreover…

- It is important to add that…

Accepting other points of view

- Nevertheless, one should accept that…

- However, we also agree that…

Personal opinion

- We/I personally believe that…

- Our/My own point of view is that…

- It is my contention that…

- I am convinced that…

- My own opinion is…

Others’ opinions

- According to some critics… Critics:

- believe that

- suggest that

- are convinced that

- point out that

- emphasize that

- contend that

- go as far as to say that

- argue for this

Introducing examples

- For example…

- For instance…

- To illustrate this point…

Introducing facts

- It is… true that…/ clear that…/ noticeable that…

- One should note here that…

Saying what you think is true

- This leads us to believe that…

- It is very possible that…

- In view of these facts, it is quite likely that…

- Doubtless,…

- One cannot deny that…

- It is (very) clear from these observations that…

- All the same, it is possible that…

- It is difficult to believe that…

Accepting other points to a certain degree

- One can agree up to a certain point with…

- Certainly,… However,…

- It cannot be denied that…

Emphasizing particular points

- The last example highlights the fact that…

- Not only… but also…

- We would even go so far as to say that…

Moderating, agreeing, disagreeing

- By and large…

- Perhaps we should also point out the fact that…

- It would be unfair not to mention the fact that…

- One must admit that…

- We cannot ignore the fact that…

- One cannot possibly accept the fact that…

Consequences

- From these facts, one may conclude that…

- That is why, in our opinion, …

- Which seems to confirm the idea that…

- Thus,…/ Therefore,…

- Some critics suggest…, whereas others…

- Compared to…

- On the one hand, there is the firm belief that… On the other hand, many people are convinced that…

How to Write a Great Essay | Image 1

How to Write a Great Essay | Image 2

Phrases For Balanced Arguments

Introduction

- It is often said that…

- It is undeniable that…

- It is a well-known fact that…

- One of the most striking features of this text is…

- The first thing that needs to be said is…

- First of all, let us try to analyze…

- One argument in support of…

- We must distinguish carefully between…

- The second reason for…

- An important aspect of the text is…

- It is worth stating at this point that…

- On the other hand, we can observe that…

- The other side of the coin is, however, that…

- Another way of looking at this question is to…

- What conclusions can be drawn from all this?

- The most satisfactory conclusion that we can come to is…

- To sum up… we are convinced that…/ …we believe that…/ …we have to accept that…

How to Write a Great Essay | Image 3

- Recent Posts

- Plural of Process in the English Grammar - October 3, 2023

- Best Kahoot Names: Get Creative with These Fun Ideas! - October 2, 2023

- List of Homophones for English Learners - September 30, 2023

Related posts:

- How to Write a Formal Letter | Useful Phrases with ESL Image

- 50+ Questions to Start a Conversation with Anyone in English

- Useful English Greetings and Expressions for English Learners

- Asking for Help, Asking for Opinions and Asking for Approval

Nur Syuhadah Zainuddin

Friday 19th of August 2022

thank u so much its really usefull

12thSeahorse

Wednesday 3rd of August 2022

He or she who masters the English language rules the world!

Friday 25th of March 2022

Thank you so so much, this helped me in my essays with A+

Theophilus Muzvidziwa

Friday 11th of March 2022

Monday 21st of February 2022

Academic Phrasebank

Being critical.

- GENERAL LANGUAGE FUNCTIONS

- Being cautious

- Classifying and listing

- Compare and contrast

- Defining terms

- Describing trends

- Describing quantities

- Explaining causality

- Giving examples

- Signalling transition

- Writing about the past

As an academic writer, you are expected to be critical of the sources that you use. This essentially means questioning what you read and not necessarily agreeing with it just because the information has been published. Being critical can also mean looking for reasons why we should not just accept something as being correct or true. This can require you to identify problems with a writer’s arguments or methods, or perhaps to refer to other people’s criticisms of these. Constructive criticism goes beyond this by suggesting ways in which a piece of research or writing could be improved. … being against is not enough. We also need to develop habits of constructive thinking. Edward de Bono

Highlighting inadequacies of previous studies

Previous studies of X have not dealt with … Researchers have not treated X in much detail. Such expositions are unsatisfactory because they … Most studies in the field of X have only focused on … Such approaches, however, have failed to address … Previous published studies are limited to local surveys. Half of the studies evaluated failed to specify whether … The research to date has tended to focus on X rather than published studies on the effect of X are not consistent. Smith’s analysis does not take account of …, nor does she examine …

The existing accounts fail to resolve the contradiction between X and Y. Most studies of X have only been carried out in a small number of areas. However, much of the research up to now has been descriptive in nature … The generalisability of much published research on this issue is problematic. Research on the subject has been mostly restricted to limited comparisons of … However, few writers have been able to draw on any systematic research into … Short-term studies such as these do not necessarily show subtle changes over time … Although extensive research has been carried out on X, no single study exists which … However, these results were based upon data from over 30 years ago and it is unclear if … The experimental data are rather controversial, and there is no general agreement about …

Identifying a weakness in a single study or paper

Offering constructive suggestions.

The study would have been more interesting if it had included … These studies would have been more useful if they had focused on … The study would have been more relevant if the researchers had asked … The questionnaire would have been more useful if it had asked participants about … The research would have been more relevant if a wider range of X had been explored

Introducing problems and limitations: theory or argument

Smith’s argument relies too heavily on … The main weakness with this theory is that … The key problem with this explanation is that … However, this theory does not fully explain why … One criticism of much of the literature on X is that … Critics question the ability of the X theory to provide … However, there is an inconsistency with this argument.

A serious weakness with this argument, however, is that … However, such explanations tend to overlook the fact that … One of the main difficulties with this line of reasoning is that … Smith’s interpretation overlooks much of the historical research … Many writers have challenged Smith’s claim on the grounds that … The X theory has been criticised for being based on weak evidence. A final criticism of the theory of X is that it struggles to explain some aspects of …

Introducing problems and limitations: method or practice

The limitation of this approach is that … A major problem with the X method is that … One major drawback of this approach is that … A criticism of this experimental design is that … The main limitation of this technique, however, is … Selection bias is another potential concern because …

Perhaps the most serious disadvantage of this method is that … In recent years, however, this approach has been challenged by … Non-government agencies are also very critical of the new policies. All the studies reviewed so far, however, suffer from the fact that … Critics of laboratory-based experiments contend that such studies … There are certain problems with the use of focus groups. One of these is that there is less …

Using evaluative adjectives to comment on research

Introducing general criticism.

Critics question the ability of poststructuralist theory to provide … Non-government agencies are also very critical of the new policies. Smith’s meta-analysis has been subjected to considerable criticism. The most important of these criticisms is that Smith failed to note that … The X theory has been vigorously challenged in recent years by a number of writers. These claims have been strongly contested in recent years by a number of writers. More recent arguments against X have been summarised by Smith and Jones (1982): Critics have also argued that not only do surveys provide an inaccurate measure of X, but the … Many analysts now argue that the strategy of X has not been successful. Jones (2003), for example, argues that …

Introducing the critical stance of particular writers

Smith (2014) disputes this account of … Jones (2003) has also questioned why … However, Jones (2015) points out that … The author challenges the widely held view that … Smith (1999) takes issue with the contention that … The idea that … was first challenged by Smith (1992). Smith is critical of the tendency to compartmentalise X. However, Smith (1967) questioned this hypothesis and …

Jones (2003) has challenged some of Smith’s conclusions, arguing that … Another major criticism of Smith’s study, made by Jones (2003), is that … Jones (2003) is probably the best-known critic of the X theory. He argues that … In her discussion of X, Smith further criticises the ways in which some authors … Smith’s decision to reject the classical explanation of X merits some discussion … In a recent article in Academic Journal, Smith (2014) questions the extent to which … The latter point has been devastatingly critiqued by Jones (2003), who argues that … A recently published article by Smith et al. (2011) casts doubt on Jones’ assumption that … Other authors (see Smith, 2012; Jones, 2014) question the usefulness of such an approach.

+44 (0) 161 306 6000

The University of Manchester Oxford Rd Manchester M13 9PL UK

Connect With Us

The University of Manchester

- Subject Guides

Academic writing: a practical guide

Criticality in academic writing.

- Academic writing

- The writing process

- Academic writing style

- Structure & cohesion

- Working with evidence

- Referencing

- Assessment & feedback

- Dissertations

- Reflective writing

- Examination writing

- Academic posters

- Feedback on Structure and Organisation

- Feedback on Argument, Analysis, and Critical Thinking

- Feedback on Writing Style and Clarity

- Feedback on Referencing and Research

- Feedback on Presentation and Proofreading

Being critical is at the heart of academic writing, but what is it and how can you incorporate it into your work?

What is criticality?

What is critical thinking.

Have you ever received feedback in a piece of work saying 'be more critical' or 'not enough critical analysis' but found yourself scratching your head, wondering what that means? Dive into this bitesize workshop to discover what it is and how to do it:

Critical Thinking: What it is and how to do it (bitesize workshop)[YouTube]

University-level work requires both descriptive and critical elements. But what's the difference?

Descriptive

Being descriptive shows what you know about a topic and provides the evidence to support your arguments. It uses simpler processes like remembering , understanding and applying . You might summarise previous research, explain concepts or describe processes.

Being critical pulls evidence together to build your arguments; what does it all mean together? It uses more complex processes: analysing , evaluating and creating . You might make comparisons, consider reasons and implications, justify choices or consider strengths and weaknesses.

Bloom's Taxonomy is a useful tool to consider descriptive and critical processes:

Bloom's Taxonomy [YouTube] | Bloom's Taxonomy [Google Doc]

Find out more about critical thinking:

What is critical writing?

Academic writing requires criticality; it's not enough to just describe or summarise evidence, you also need to analyse and evaluate information and use it to build your own arguments. This is where you show your own thoughts based on the evidence available, so critical writing is really important for higher grades.

Explore the key features of critical writing and see it in practice in some examples:

Introduction to critical writing [Google Slides]

While we need criticality in our writing, it's definitely possible to go further than needed. We’re aiming for that Goldilocks ‘just right’ point between not critical enough and too critical. Find out more:

Critical reading

Criticality isn't just for writing, it is also important to read critically. Reading critically helps you:

- evaluative whether sources are suitable for your assignments.

- know what you're looking for when reading.

- find the information you need quickly.

Critical reading [Interactive tutorial] | Critical reading [Google Doc]

Find out more on our dedicated guides:

Using evidence critically

Academic writing integrates evidence from sources to create your own critical arguments.

We're not looking for a list of summaries of individual sources; ideally, the important evidence should be integrated into a cohesive whole. What does the evidence mean altogether? Of course, a critical argument also needs some critical analysis of this evidence. What does it all mean in terms of your argument?

Find out more about using evidence to build critical arguments in our guide to working with evidence:

Critical language

Critical writing is going to require critical language. Different terms will give different nuance to your argument. Others will just keep things interesting! In the document below we go through some examples to help you out:

Assignment titles: critical or descriptive?

Assignment titles contain various words that show where you need to be descriptive and where you need to be critical. Explore some of the most common instructional words:

Descriptive instructional words

define : give the precise meaning

examine : look at carefully; consider different aspects

explain : clearly describe how a process works, why a decision was made, or give other information needed to understand the topic

illustrate : explain and describe using examples

outline : give an overview of the key information, leaving out minor details

Critical instructional words

analyse : break down the information into parts, consider how parts work together

discuss : explain a topic, make comparisons, consider strengths & weaknesses, give reasons, consider implications

evaluate : assess something's worth, value or suitability for a purpose - this often leads to making a choice afterwards

justify : show the reasoning behind a choice, argument or standpoint

synthesise : bring together evidence and information to create a cohesive whole, integrate ideas or issues

CC BY-NC-SA Learnhigher

More guidance on breaking down assignment titles:

- << Previous: Structure & cohesion

- Next: Working with evidence >>

- Last Updated: Apr 3, 2024 4:02 PM

- URL: https://subjectguides.york.ac.uk/academic-writing

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

How to Write an Essay Introduction (with Examples)

The introduction of an essay plays a critical role in engaging the reader and providing contextual information about the topic. It sets the stage for the rest of the essay, establishes the tone and style, and motivates the reader to continue reading.

Table of Contents

What is an essay introduction , what to include in an essay introduction, how to create an essay structure , step-by-step process for writing an essay introduction , how to write an introduction paragraph , how to write a hook for your essay , how to include background information , how to write a thesis statement .

- Argumentative Essay Introduction Example:

- Expository Essay Introduction Example

Literary Analysis Essay Introduction Example

Check and revise – checklist for essay introduction , key takeaways , frequently asked questions .

An introduction is the opening section of an essay, paper, or other written work. It introduces the topic and provides background information, context, and an overview of what the reader can expect from the rest of the work. 1 The key is to be concise and to the point, providing enough information to engage the reader without delving into excessive detail.

The essay introduction is crucial as it sets the tone for the entire piece and provides the reader with a roadmap of what to expect. Here are key elements to include in your essay introduction:

- Hook : Start with an attention-grabbing statement or question to engage the reader. This could be a surprising fact, a relevant quote, or a compelling anecdote.

- Background information : Provide context and background information to help the reader understand the topic. This can include historical information, definitions of key terms, or an overview of the current state of affairs related to your topic.

- Thesis statement : Clearly state your main argument or position on the topic. Your thesis should be concise and specific, providing a clear direction for your essay.

Before we get into how to write an essay introduction, we need to know how it is structured. The structure of an essay is crucial for organizing your thoughts and presenting them clearly and logically. It is divided as follows: 2

- Introduction: The introduction should grab the reader’s attention with a hook, provide context, and include a thesis statement that presents the main argument or purpose of the essay.

- Body: The body should consist of focused paragraphs that support your thesis statement using evidence and analysis. Each paragraph should concentrate on a single central idea or argument and provide evidence, examples, or analysis to back it up.

- Conclusion: The conclusion should summarize the main points and restate the thesis differently. End with a final statement that leaves a lasting impression on the reader. Avoid new information or arguments.

Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to write an essay introduction:

- Start with a Hook : Begin your introduction paragraph with an attention-grabbing statement, question, quote, or anecdote related to your topic. The hook should pique the reader’s interest and encourage them to continue reading.

- Provide Background Information : This helps the reader understand the relevance and importance of the topic.

- State Your Thesis Statement : The last sentence is the main argument or point of your essay. It should be clear, concise, and directly address the topic of your essay.

- Preview the Main Points : This gives the reader an idea of what to expect and how you will support your thesis.

- Keep it Concise and Clear : Avoid going into too much detail or including information not directly relevant to your topic.

- Revise : Revise your introduction after you’ve written the rest of your essay to ensure it aligns with your final argument.

Here’s an example of an essay introduction paragraph about the importance of education:

Education is often viewed as a fundamental human right and a key social and economic development driver. As Nelson Mandela once famously said, “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” It is the key to unlocking a wide range of opportunities and benefits for individuals, societies, and nations. In today’s constantly evolving world, education has become even more critical. It has expanded beyond traditional classroom learning to include digital and remote learning, making education more accessible and convenient. This essay will delve into the importance of education in empowering individuals to achieve their dreams, improving societies by promoting social justice and equality, and driving economic growth by developing a skilled workforce and promoting innovation.

This introduction paragraph example includes a hook (the quote by Nelson Mandela), provides some background information on education, and states the thesis statement (the importance of education).

This is one of the key steps in how to write an essay introduction. Crafting a compelling hook is vital because it sets the tone for your entire essay and determines whether your readers will stay interested. A good hook draws the reader in and sets the stage for the rest of your essay.

- Avoid Dry Fact : Instead of simply stating a bland fact, try to make it engaging and relevant to your topic. For example, if you’re writing about the benefits of exercise, you could start with a startling statistic like, “Did you know that regular exercise can increase your lifespan by up to seven years?”

- Avoid Using a Dictionary Definition : While definitions can be informative, they’re not always the most captivating way to start an essay. Instead, try to use a quote, anecdote, or provocative question to pique the reader’s interest. For instance, if you’re writing about freedom, you could begin with a quote from a famous freedom fighter or philosopher.

- Do Not Just State a Fact That the Reader Already Knows : This ties back to the first point—your hook should surprise or intrigue the reader. For Here’s an introduction paragraph example, if you’re writing about climate change, you could start with a thought-provoking statement like, “Despite overwhelming evidence, many people still refuse to believe in the reality of climate change.”

Including background information in the introduction section of your essay is important to provide context and establish the relevance of your topic. When writing the background information, you can follow these steps:

- Start with a General Statement: Begin with a general statement about the topic and gradually narrow it down to your specific focus. For example, when discussing the impact of social media, you can begin by making a broad statement about social media and its widespread use in today’s society, as follows: “Social media has become an integral part of modern life, with billions of users worldwide.”

- Define Key Terms : Define any key terms or concepts that may be unfamiliar to your readers but are essential for understanding your argument.

- Provide Relevant Statistics: Use statistics or facts to highlight the significance of the issue you’re discussing. For instance, “According to a report by Statista, the number of social media users is expected to reach 4.41 billion by 2025.”

- Discuss the Evolution: Mention previous research or studies that have been conducted on the topic, especially those that are relevant to your argument. Mention key milestones or developments that have shaped its current impact. You can also outline some of the major effects of social media. For example, you can briefly describe how social media has evolved, including positives such as increased connectivity and issues like cyberbullying and privacy concerns.

- Transition to Your Thesis: Use the background information to lead into your thesis statement, which should clearly state the main argument or purpose of your essay. For example, “Given its pervasive influence, it is crucial to examine the impact of social media on mental health.”

A thesis statement is a concise summary of the main point or claim of an essay, research paper, or other type of academic writing. It appears near the end of the introduction. Here’s how to write a thesis statement:

- Identify the topic: Start by identifying the topic of your essay. For example, if your essay is about the importance of exercise for overall health, your topic is “exercise.”

- State your position: Next, state your position or claim about the topic. This is the main argument or point you want to make. For example, if you believe that regular exercise is crucial for maintaining good health, your position could be: “Regular exercise is essential for maintaining good health.”

- Support your position: Provide a brief overview of the reasons or evidence that support your position. These will be the main points of your essay. For example, if you’re writing an essay about the importance of exercise, you could mention the physical health benefits, mental health benefits, and the role of exercise in disease prevention.

- Make it specific: Ensure your thesis statement clearly states what you will discuss in your essay. For example, instead of saying, “Exercise is good for you,” you could say, “Regular exercise, including cardiovascular and strength training, can improve overall health and reduce the risk of chronic diseases.”

Examples of essay introduction

Here are examples of essay introductions for different types of essays:

Argumentative Essay Introduction Example:

Topic: Should the voting age be lowered to 16?

“The question of whether the voting age should be lowered to 16 has sparked nationwide debate. While some argue that 16-year-olds lack the requisite maturity and knowledge to make informed decisions, others argue that doing so would imbue young people with agency and give them a voice in shaping their future.”

Expository Essay Introduction Example

Topic: The benefits of regular exercise

“In today’s fast-paced world, the importance of regular exercise cannot be overstated. From improving physical health to boosting mental well-being, the benefits of exercise are numerous and far-reaching. This essay will examine the various advantages of regular exercise and provide tips on incorporating it into your daily routine.”

Text: “To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee

“Harper Lee’s novel, ‘To Kill a Mockingbird,’ is a timeless classic that explores themes of racism, injustice, and morality in the American South. Through the eyes of young Scout Finch, the reader is taken on a journey that challenges societal norms and forces characters to confront their prejudices. This essay will analyze the novel’s use of symbolism, character development, and narrative structure to uncover its deeper meaning and relevance to contemporary society.”

- Engaging and Relevant First Sentence : The opening sentence captures the reader’s attention and relates directly to the topic.

- Background Information : Enough background information is introduced to provide context for the thesis statement.

- Definition of Important Terms : Key terms or concepts that might be unfamiliar to the audience or are central to the argument are defined.

- Clear Thesis Statement : The thesis statement presents the main point or argument of the essay.

- Relevance to Main Body : Everything in the introduction directly relates to and sets up the discussion in the main body of the essay.

Writing a strong introduction is crucial for setting the tone and context of your essay. Here are the key takeaways for how to write essay introduction: 3

- Hook the Reader : Start with an engaging hook to grab the reader’s attention. This could be a compelling question, a surprising fact, a relevant quote, or an anecdote.

- Provide Background : Give a brief overview of the topic, setting the context and stage for the discussion.

- Thesis Statement : State your thesis, which is the main argument or point of your essay. It should be concise, clear, and specific.

- Preview the Structure : Outline the main points or arguments to help the reader understand the organization of your essay.

- Keep it Concise : Avoid including unnecessary details or information not directly related to your thesis.

- Revise and Edit : Revise your introduction to ensure clarity, coherence, and relevance. Check for grammar and spelling errors.

- Seek Feedback : Get feedback from peers or instructors to improve your introduction further.

The purpose of an essay introduction is to give an overview of the topic, context, and main ideas of the essay. It is meant to engage the reader, establish the tone for the rest of the essay, and introduce the thesis statement or central argument.

An essay introduction typically ranges from 5-10% of the total word count. For example, in a 1,000-word essay, the introduction would be roughly 50-100 words. However, the length can vary depending on the complexity of the topic and the overall length of the essay.

An essay introduction is critical in engaging the reader and providing contextual information about the topic. To ensure its effectiveness, consider incorporating these key elements: a compelling hook, background information, a clear thesis statement, an outline of the essay’s scope, a smooth transition to the body, and optional signposting sentences.

The process of writing an essay introduction is not necessarily straightforward, but there are several strategies that can be employed to achieve this end. When experiencing difficulty initiating the process, consider the following techniques: begin with an anecdote, a quotation, an image, a question, or a startling fact to pique the reader’s interest. It may also be helpful to consider the five W’s of journalism: who, what, when, where, why, and how. For instance, an anecdotal opening could be structured as follows: “As I ascended the stage, momentarily blinded by the intense lights, I could sense the weight of a hundred eyes upon me, anticipating my next move. The topic of discussion was climate change, a subject I was passionate about, and it was my first public speaking event. Little did I know , that pivotal moment would not only alter my perspective but also chart my life’s course.”

Crafting a compelling thesis statement for your introduction paragraph is crucial to grab your reader’s attention. To achieve this, avoid using overused phrases such as “In this paper, I will write about” or “I will focus on” as they lack originality. Instead, strive to engage your reader by substantiating your stance or proposition with a “so what” clause. While writing your thesis statement, aim to be precise, succinct, and clear in conveying your main argument.

To create an effective essay introduction, ensure it is clear, engaging, relevant, and contains a concise thesis statement. It should transition smoothly into the essay and be long enough to cover necessary points but not become overwhelming. Seek feedback from peers or instructors to assess its effectiveness.

References

- Cui, L. (2022). Unit 6 Essay Introduction. Building Academic Writing Skills .

- West, H., Malcolm, G., Keywood, S., & Hill, J. (2019). Writing a successful essay. Journal of Geography in Higher Education , 43 (4), 609-617.

- Beavers, M. E., Thoune, D. L., & McBeth, M. (2023). Bibliographic Essay: Reading, Researching, Teaching, and Writing with Hooks: A Queer Literacy Sponsorship. College English, 85(3), 230-242.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- What is an Argumentative Essay? How to Write It (With Examples)

- How to Paraphrase Research Papers Effectively

- How to Cite Social Media Sources in Academic Writing?

- How Long Should a Chapter Be?

Similarity Checks: The Author’s Guide to Plagiarism and Responsible Writing