How to Write a Case Study - All You Wanted to Know

What do you study in your college? If you are a psychology, sociology, or anthropology student, we bet you might be familiar with what a case study is. This research method is used to study a certain person, group, or situation. In this guide from our dissertation writing service , you will learn how to write a case study professionally, from researching to citing sources properly. Also, we will explore different types of case studies and show you examples — so that you won’t have any other questions left.

What Is a Case Study?

A case study is a subcategory of research design which investigates problems and offers solutions. Case studies can range from academic research studies to corporate promotional tools trying to sell an idea—their scope is quite vast.

What Is the Difference Between a Research Paper and a Case Study?

While research papers turn the reader’s attention to a certain problem, case studies go even further. Case study guidelines require students to pay attention to details, examining issues closely and in-depth using different research methods. For example, case studies may be used to examine court cases if you study Law, or a patient's health history if you study Medicine. Case studies are also used in Marketing, which are thorough, empirically supported analysis of a good or service's performance. Well-designed case studies can be valuable for prospective customers as they can identify and solve the potential customers pain point.

Case studies involve a lot of storytelling – they usually examine particular cases for a person or a group of people. This method of research is very helpful, as it is very practical and can give a lot of hands-on information. Most commonly, the length of the case study is about 500-900 words, which is much less than the length of an average research paper.

The structure of a case study is very similar to storytelling. It has a protagonist or main character, which in your case is actually a problem you are trying to solve. You can use the system of 3 Acts to make it a compelling story. It should have an introduction, rising action, a climax where transformation occurs, falling action, and a solution.

Here is a rough formula for you to use in your case study:

Problem (Act I): > Solution (Act II) > Result (Act III) > Conclusion.

Types of Case Studies

The purpose of a case study is to provide detailed reports on an event, an institution, a place, future customers, or pretty much anything. There are a few common types of case study, but the type depends on the topic. The following are the most common domains where case studies are needed:

- Historical case studies are great to learn from. Historical events have a multitude of source info offering different perspectives. There are always modern parallels where these perspectives can be applied, compared, and thoroughly analyzed.

- Problem-oriented case studies are usually used for solving problems. These are often assigned as theoretical situations where you need to immerse yourself in the situation to examine it. Imagine you’re working for a startup and you’ve just noticed a significant flaw in your product’s design. Before taking it to the senior manager, you want to do a comprehensive study on the issue and provide solutions. On a greater scale, problem-oriented case studies are a vital part of relevant socio-economic discussions.

- Cumulative case studies collect information and offer comparisons. In business, case studies are often used to tell people about the value of a product.

- Critical case studies explore the causes and effects of a certain case.

- Illustrative case studies describe certain events, investigating outcomes and lessons learned.

Need a compelling case study? EssayPro has got you covered. Our experts are ready to provide you with detailed, insightful case studies that capture the essence of real-world scenarios. Elevate your academic work with our professional assistance.

Case Study Format

The case study format is typically made up of eight parts:

- Executive Summary. Explain what you will examine in the case study. Write an overview of the field you’re researching. Make a thesis statement and sum up the results of your observation in a maximum of 2 sentences.

- Background. Provide background information and the most relevant facts. Isolate the issues.

- Case Evaluation. Isolate the sections of the study you want to focus on. In it, explain why something is working or is not working.

- Proposed Solutions. Offer realistic ways to solve what isn’t working or how to improve its current condition. Explain why these solutions work by offering testable evidence.

- Conclusion. Summarize the main points from the case evaluations and proposed solutions. 6. Recommendations. Talk about the strategy that you should choose. Explain why this choice is the most appropriate.

- Implementation. Explain how to put the specific strategies into action.

- References. Provide all the citations.

How to Write a Case Study

Let's discover how to write a case study.

Setting Up the Research

When writing a case study, remember that research should always come first. Reading many different sources and analyzing other points of view will help you come up with more creative solutions. You can also conduct an actual interview to thoroughly investigate the customer story that you'll need for your case study. Including all of the necessary research, writing a case study may take some time. The research process involves doing the following:

- Define your objective. Explain the reason why you’re presenting your subject. Figure out where you will feature your case study; whether it is written, on video, shown as an infographic, streamed as a podcast, etc.

- Determine who will be the right candidate for your case study. Get permission, quotes, and other features that will make your case study effective. Get in touch with your candidate to see if they approve of being part of your work. Study that candidate’s situation and note down what caused it.

- Identify which various consequences could result from the situation. Follow these guidelines on how to start a case study: surf the net to find some general information you might find useful.

- Make a list of credible sources and examine them. Seek out important facts and highlight problems. Always write down your ideas and make sure to brainstorm.

- Focus on several key issues – why they exist, and how they impact your research subject. Think of several unique solutions. Draw from class discussions, readings, and personal experience. When writing a case study, focus on the best solution and explore it in depth. After having all your research in place, writing a case study will be easy. You may first want to check the rubric and criteria of your assignment for the correct case study structure.

Read Also: ' WHAT IS A CREDIBLE SOURCES ?'

Although your instructor might be looking at slightly different criteria, every case study rubric essentially has the same standards. Your professor will want you to exhibit 8 different outcomes:

- Correctly identify the concepts, theories, and practices in the discipline.

- Identify the relevant theories and principles associated with the particular study.

- Evaluate legal and ethical principles and apply them to your decision-making.

- Recognize the global importance and contribution of your case.

- Construct a coherent summary and explanation of the study.

- Demonstrate analytical and critical-thinking skills.

- Explain the interrelationships between the environment and nature.

- Integrate theory and practice of the discipline within the analysis.

Need Case Study DONE FAST?

Pick a topic, tell us your requirements and get your paper on time.

Case Study Outline

Let's look at the structure of an outline based on the issue of the alcoholic addiction of 30 people.

Introduction

- Statement of the issue: Alcoholism is a disease rather than a weakness of character.

- Presentation of the problem: Alcoholism is affecting more than 14 million people in the USA, which makes it the third most common mental illness there.

- Explanation of the terms: In the past, alcoholism was commonly referred to as alcohol dependence or alcohol addiction. Alcoholism is now the more severe stage of this addiction in the disorder spectrum.

- Hypotheses: Drinking in excess can lead to the use of other drugs.

- Importance of your story: How the information you present can help people with their addictions.

- Background of the story: Include an explanation of why you chose this topic.

- Presentation of analysis and data: Describe the criteria for choosing 30 candidates, the structure of the interview, and the outcomes.

- Strong argument 1: ex. X% of candidates dealing with anxiety and depression...

- Strong argument 2: ex. X amount of people started drinking by their mid-teens.

- Strong argument 3: ex. X% of respondents’ parents had issues with alcohol.

- Concluding statement: I have researched if alcoholism is a disease and found out that…

- Recommendations: Ways and actions for preventing alcohol use.

Writing a Case Study Draft

After you’ve done your case study research and written the outline, it’s time to focus on the draft. In a draft, you have to develop and write your case study by using: the data which you collected throughout the research, interviews, and the analysis processes that were undertaken. Follow these rules for the draft:

| 📝 Step | 📌 Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Draft Structure | 🖋️ Your draft should contain at least 4 sections: an introduction; a body where you should include background information, an explanation of why you decided to do this case study, and a presentation of your main findings; a conclusion where you present data; and references. |

| 2. Introduction | 📚 In the introduction, you should set the pace very clearly. You can even raise a question or quote someone you interviewed in the research phase. It must provide adequate background information on the topic. The background may include analyses of previous studies on your topic. Include the aim of your case here as well. Think of it as a thesis statement. The aim must describe the purpose of your work—presenting the issues that you want to tackle. Include background information, such as photos or videos you used when doing the research. |

| 3. Research Process | 🔍 Describe your unique research process, whether it was through interviews, observations, academic journals, etc. The next point includes providing the results of your research. Tell the audience what you found out. Why is this important, and what could be learned from it? Discuss the real implications of the problem and its significance in the world. |

| 4. Quotes and Data | 💬 Include quotes and data (such as findings, percentages, and awards). This will add a personal touch and better credibility to the case you present. Explain what results you find during your interviews in regards to the problem and how it developed. Also, write about solutions which have already been proposed by other people who have already written about this case. |

| 5. Offer Solutions | 💡 At the end of your case study, you should offer possible solutions, but don’t worry about solving them yourself. |

Use Data to Illustrate Key Points in Your Case Study

Even though your case study is a story, it should be based on evidence. Use as much data as possible to illustrate your point. Without the right data, your case study may appear weak and the readers may not be able to relate to your issue as much as they should. Let's see the examples from essay writing service :

With data: Alcoholism is affecting more than 14 million people in the USA, which makes it the third most common mental illness there. Without data: A lot of people suffer from alcoholism in the United States.

Try to include as many credible sources as possible. You may have terms or sources that could be hard for other cultures to understand. If this is the case, you should include them in the appendix or Notes for the Instructor or Professor.

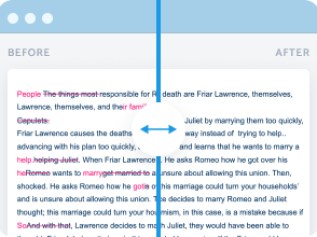

Finalizing the Draft: Checklist

After you finish drafting your case study, polish it up by answering these ‘ask yourself’ questions and think about how to end your case study:

- Check that you follow the correct case study format, also in regards to text formatting.

- Check that your work is consistent with its referencing and citation style.

- Micro-editing — check for grammar and spelling issues.

- Macro-editing — does ‘the big picture’ come across to the reader? Is there enough raw data, such as real-life examples or personal experiences? Have you made your data collection process completely transparent? Does your analysis provide a clear conclusion, allowing for further research and practice?

Problems to avoid:

- Overgeneralization – Do not go into further research that deviates from the main problem.

- Failure to Document Limitations – Just as you have to clearly state the limitations of a general research study, you must describe the specific limitations inherent in the subject of analysis.

- Failure to Extrapolate All Possible Implications – Just as you don't want to over-generalize from your case study findings, you also have to be thorough in the consideration of all possible outcomes or recommendations derived from your findings.

How to Create a Title Page and Cite a Case Study

Let's see how to create an awesome title page.

Your title page depends on the prescribed citation format. The title page should include:

- A title that attracts some attention and describes your study

- The title should have the words “case study” in it

- The title should range between 5-9 words in length

- Your name and contact information

- Your finished paper should be only 500 to 1,500 words in length.With this type of assignment, write effectively and avoid fluff

Here is a template for the APA and MLA format title page:

There are some cases when you need to cite someone else's study in your own one – therefore, you need to master how to cite a case study. A case study is like a research paper when it comes to citations. You can cite it like you cite a book, depending on what style you need.

Citation Example in MLA Hill, Linda, Tarun Khanna, and Emily A. Stecker. HCL Technologies. Boston: Harvard Business Publishing, 2008. Print.

Citation Example in APA Hill, L., Khanna, T., & Stecker, E. A. (2008). HCL Technologies. Boston: Harvard Business Publishing.

Citation Example in Chicago Hill, Linda, Tarun Khanna, and Emily A. Stecker. HCL Technologies.

Case Study Examples

To give you an idea of a professional case study example, we gathered and linked some below.

Eastman Kodak Case Study

Case Study Example: Audi Trains Mexican Autoworkers in Germany

To conclude, a case study is one of the best methods of getting an overview of what happened to a person, a group, or a situation in practice. It allows you to have an in-depth glance at the real-life problems that businesses, healthcare industry, criminal justice, etc. may face. This insight helps us look at such situations in a different light. This is because we see scenarios that we otherwise would not, without necessarily being there. If you need custom essays , try our research paper writing services .

Get Help Form Qualified Writers

Crafting a case study is not easy. You might want to write one of high quality, but you don’t have the time or expertise. If you’re having trouble with your case study, help with essay request - we'll help. EssayPro writers have read and written countless case studies and are experts in endless disciplines. Request essay writing, editing, or proofreading assistance from our custom case study writing service , and all of your worries will be gone.

Don't Know Where to Start?

Crafting a case study is not easy. You might want to write one of high quality, but you don’t have the time or expertise. Request ' write my case study ' assistance from our service.

What Is A Case Study?

How to cite a case study in apa, how to write a case study.

Daniel Parker

is a seasoned educational writer focusing on scholarship guidance, research papers, and various forms of academic essays including reflective and narrative essays. His expertise also extends to detailed case studies. A scholar with a background in English Literature and Education, Daniel’s work on EssayPro blog aims to support students in achieving academic excellence and securing scholarships. His hobbies include reading classic literature and participating in academic forums.

is an expert in nursing and healthcare, with a strong background in history, law, and literature. Holding advanced degrees in nursing and public health, his analytical approach and comprehensive knowledge help students navigate complex topics. On EssayPro blog, Adam provides insightful articles on everything from historical analysis to the intricacies of healthcare policies. In his downtime, he enjoys historical documentaries and volunteering at local clinics.

.webp)

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

| Research question | Case study |

|---|---|

| What are the ecological effects of wolf reintroduction? | Case study of wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone National Park |

| How do populist politicians use narratives about history to gain support? | Case studies of Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and US president Donald Trump |

| How can teachers implement active learning strategies in mixed-level classrooms? | Case study of a local school that promotes active learning |

| What are the main advantages and disadvantages of wind farms for rural communities? | Case studies of three rural wind farm development projects in different parts of the country |

| How are viral marketing strategies changing the relationship between companies and consumers? | Case study of the iPhone X marketing campaign |

| How do experiences of work in the gig economy differ by gender, race and age? | Case studies of Deliveroo and Uber drivers in London |

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved August 12, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write a Case Study | Examples & Methods

What is a case study?

A case study is a research approach that provides an in-depth examination of a particular phenomenon, event, organization, or individual. It involves analyzing and interpreting data to provide a comprehensive understanding of the subject under investigation.

Case studies can be used in various disciplines, including business, social sciences, medicine ( clinical case report ), engineering, and education. The aim of a case study is to provide an in-depth exploration of a specific subject, often with the goal of generating new insights into the phenomena being studied.

When to write a case study

Case studies are often written to present the findings of an empirical investigation or to illustrate a particular point or theory. They are useful when researchers want to gain an in-depth understanding of a specific phenomenon or when they are interested in exploring new areas of inquiry.

Case studies are also useful when the subject of the research is rare or when the research question is complex and requires an in-depth examination. A case study can be a good fit for a thesis or dissertation as well.

Case study examples

Below are some examples of case studies with their research questions:

| How do small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in developing countries manage risks? | Risk management practices in SMEs in Ghana |

| What factors contribute to successful organizational change? | A case study of a successful organizational change at Company X |

| How do teachers use technology to enhance student learning in the classroom? | The impact of technology integration on student learning in a primary school in the United States |

| How do companies adapt to changing consumer preferences? | Coca-Cola’s strategy to address the declining demand for sugary drinks |

| What are the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the hospitality industry? | The impact of COVID-19 on the hotel industry in Europe |

| How do organizations use social media for branding and marketing? | The role of Instagram in fashion brand promotion |

| How do businesses address ethical issues in their operations? | A case study of Nike’s supply chain labor practices |

These examples demonstrate the diversity of research questions and case studies that can be explored. From studying small businesses in Ghana to the ethical issues in supply chains, case studies can be used to explore a wide range of phenomena.

Outlying cases vs. representative cases

An outlying case stud y refers to a case that is unusual or deviates significantly from the norm. An example of an outlying case study could be a small, family-run bed and breakfast that was able to survive and even thrive during the COVID-19 pandemic, while other larger hotels struggled to stay afloat.

On the other hand, a representative case study refers to a case that is typical of the phenomenon being studied. An example of a representative case study could be a hotel chain that operates in multiple locations that faced significant challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic, such as reduced demand for hotel rooms, increased safety and health protocols, and supply chain disruptions. The hotel chain case could be representative of the broader hospitality industry during the pandemic, and thus provides an insight into the typical challenges that businesses in the industry faced.

Steps for Writing a Case Study

As with any academic paper, writing a case study requires careful preparation and research before a single word of the document is ever written. Follow these basic steps to ensure that you don’t miss any crucial details when composing your case study.

Step 1: Select a case to analyze

After you have developed your statement of the problem and research question , the first step in writing a case study is to select a case that is representative of the phenomenon being investigated or that provides an outlier. For example, if a researcher wants to explore the impact of COVID-19 on the hospitality industry, they could select a representative case, such as a hotel chain that operates in multiple locations, or an outlying case, such as a small bed and breakfast that was able to pivot their business model to survive during the pandemic. Selecting the appropriate case is critical in ensuring the research question is adequately explored.

Step 2: Create a theoretical framework

Theoretical frameworks are used to guide the analysis and interpretation of data in a case study. The framework should provide a clear explanation of the key concepts, variables, and relationships that are relevant to the research question. The theoretical framework can be drawn from existing literature, or the researcher can develop their own framework based on the data collected. The theoretical framework should be developed early in the research process to guide the data collection and analysis.

To give your case analysis a strong theoretical grounding, be sure to include a literature review of references and sources relating to your topic and develop a clear theoretical framework. Your case study does not simply stand on its own but interacts with other studies related to your topic. Your case study can do one of the following:

- Demonstrate a theory by showing how it explains the case being investigated

- Broaden a theory by identifying additional concepts and ideas that can be incorporated to strengthen it

- Confront a theory via an outlier case that does not conform to established conclusions or assumptions

Step 3: Collect data for your case study

Data collection can involve a variety of research methods , including interviews, surveys, observations, and document analyses, and it can include both primary and secondary sources . It is essential to ensure that the data collected is relevant to the research question and that it is collected in a systematic and ethical manner. Data collection methods should be chosen based on the research question and the availability of data. It is essential to plan data collection carefully to ensure that the data collected is of high quality

Step 4: Describe the case and analyze the details

The final step is to describe the case in detail and analyze the data collected. This involves identifying patterns and themes that emerge from the data and drawing conclusions that are relevant to the research question. It is essential to ensure that the analysis is supported by the data and that any limitations or alternative explanations are acknowledged.

The manner in which you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard academic paper, with separate sections or chapters for the methods section , results section , and discussion section , while others are structured more like a standalone literature review.

Regardless of the topic you choose to pursue, writing a case study requires a systematic and rigorous approach to data collection and analysis. By following the steps outlined above and using examples from existing literature, researchers can create a comprehensive and insightful case study that contributes to the understanding of a particular phenomenon.

Preparing Your Case Study for Publication

After completing the draft of your case study, be sure to revise and edit your work for any mistakes, including grammatical errors , punctuation errors , spelling mistakes, and awkward sentence structure . Ensure that your case study is well-structured and that your arguments are well-supported with language that follows the conventions of academic writing . To ensure your work is polished for style and free of errors, get English editing services from Wordvice, including our paper editing services and manuscript editing services . Let our academic subject experts enhance the style and flow of your academic work so you can submit your case study with confidence.

How to Write a Case Study: A Step-by-Step Guide (+ Examples)

by Todd Brehe

on Jan 3, 2024

If you want to learn how to write a case study that engages prospective clients, demonstrates that you can solve real business problems, and showcases the results you deliver, this guide will help.

We’ll give you a proven template to follow, show you how to conduct an engaging interview, and give you several examples and tips for best practices.

Let’s start with the basics.

What is a Case Study?

A business case study is simply a story about how you successfully delivered a solution to your client.

Case studies start with background information about the customer, describe problems they were facing, present the solutions you developed, and explain how those solutions positively impacted the customer’s business.

Do Marketing Case Studies Really Work?

Absolutely. A well-written case study puts prospective clients into the shoes of your paying clients, encouraging them to engage with you. Plus, they:

- Get shared “behind the lines” with decision makers you may not know;

- Leverage the power of “social proof” to encourage a prospective client to take a chance with your company;

- Build trust and foster likeability;

- Lessen the perceived risk of doing business with you and offer proof that your business can deliver results;

- Help prospects become aware of unrecognized problems;

- Show prospects experiencing similar problems that possible solutions are available (and you can provide said solutions);

- Make it easier for your target audience to find you when using Google and other search engines.

Case studies serve your clients too. For example, they can generate positive publicity and highlight the accomplishments of line staff to the management team. Your company might even throw in a new product/service discount, or a gift as an added bonus.

But don’t just take my word for it. Let’s look at a few statistics and success stories:

5 Winning Case Study Examples to Model

Before we get into the nuts and bolts of how to write a case study, let’s go over a few examples of what an excellent one looks like.

The five case studies listed below are well-written, well-designed, and incorporate a time-tested structure.

1. Lane Terralever and Pinnacle at Promontory

This case study example from Lane Terralever incorporates images to support the content and effectively uses subheadings to make the piece scannable.

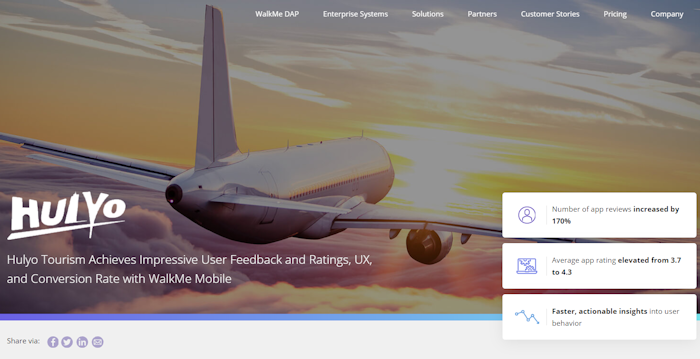

2. WalkMe Mobile and Hulyo

This case study from WalkMe Mobile leads with an engaging headline and the three most important results the client was able to generate.

In the first paragraph, the writer expands the list of accomplishments encouraging readers to learn more.

3. CurationSuite Listening Engine

This is an example of a well-designed printable case study . The client, specific problem, and solution are called out in the left column and summarized succinctly.

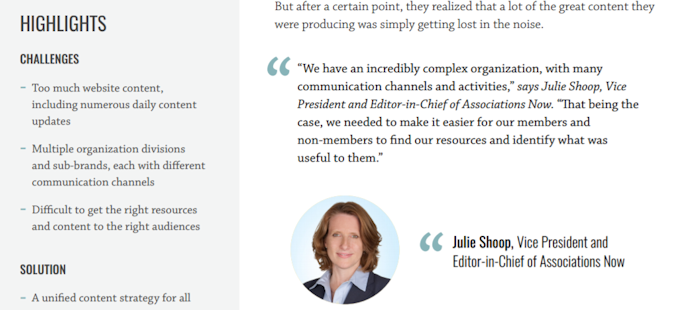

4. Brain Traffic and ASAE

This long format case study (6 pages) from Brain Traffic summarizes the challenges, solutions, and results prominently in the left column. It uses testimonials and headshots of the case study participants very effectively.

5. Adobe and Home Depot

This case study from Adobe and Home Depot is a great example of combining video, attention-getting graphics, and long form writing. It also uses testimonials and headshots well.

Now that we’ve gone over the basics and showed a few great case study examples you can use as inspiration, let’s roll up our sleeves and get to work.

A Case Study Structure That Pros Use

Let’s break down the structure of a compelling case study:

Choose Your Case Study Format

In this guide, we focus on written case studies. They’re affordable to create, and they have a proven track record. However, written case studies are just one of four case study formats to consider:

- Infographic

If you have the resources, video (like the Adobe and Home Depot example above) and podcast case studies can be very compelling. Hearing a client discuss in his or her own words how your company helped is an effective content marketing strategy

Infographic case studies are usually one-page images that summarize the challenge, proposed solution, and results. They tend to work well on social media.

Follow a Tried-and-True Case Study Template

The success story structure we’re using incorporates a “narrative” or “story arc” designed to suck readers in and captivate their interest.

Note: I recommend creating a blog post or landing page on your website that includes the text from your case study, along with a downloadable PDF. Doing so helps people find your content when they perform Google and other web searches.

There are a few simple SEO strategies that you can apply to your blog post that will optimize your chances of being found. I’ll include those tips below.

Craft a Compelling Headline

The headline should capture your audience’s attention quickly. Include the most important result you achieved, the client’s name, and your company’s name. Create several examples, mull them over a bit, then pick the best one. And, yes, this means writing the headline is done at the very end.

SEO Tip: Let’s say your firm provided “video editing services” and you want to target this primary keyword. Include it, your company name, and your client’s name in the case study title.

Write the Executive Summary

This is a mini-narrative using an abbreviated version of the Challenge + Solution + Results model (3-4 short paragraphs). Write this after you complete the case study.

SEO Tip: Include your primary keyword in the first paragraph of the Executive Summary.

Provide the Client’s Background

Introduce your client to the reader and create context for the story.

List the Customer’s Challenges and Problems

Vividly describe the situation and problems the customer was dealing with, before working with you.

SEO Tip: To rank on page one of Google for our target keyword, review the questions listed in the “People also ask” section at the top of Google’s search results. If you can include some of these questions and their answers into your case study, do so. Just make sure they fit with the flow of your narrative.

Detail Your Solutions

Explain the product or service your company provided, and spell out how it alleviated the client’s problems. Recap how the solution was delivered and implemented. Describe any training needed and the customer’s work effort.

Show Your Results

Detail what you accomplished for the customer and the impact your product/service made. Objective, measurable results that resonate with your target audience are best.

List Future Plans

Share how your client might work with your company in the future.

Give a Call-to-Action

Clearly detail what you want the reader to do at the end of your case study.

Talk About You

Include a “press release-like” description of your client’s organization, with a link to their website. For your printable document, add an “About” section with your contact information.

And that’s it. That’s the basic structure of any good case study.

Now, let’s go over how to get the information you’ll use in your case study.

How to Conduct an Engaging Case Study Interview

One of the best parts of creating a case study is talking with your client about the experience. This is a fun and productive way to learn what your company did well, and what it can improve on, directly from your customer’s perspective.

Here are some suggestions for conducting great case study interviews:

When Choosing a Case Study Subject, Pick a Raving Fan

Your sales and marketing team should know which clients are vocal advocates willing to talk about their experiences. Your customer service and technical support teams should be able to contribute suggestions.

Clients who are experts with your product/service make solid case study candidates. If you sponsor an online community, look for product champions who post consistently and help others.

When selecting a candidate, think about customer stories that would appeal to your target audience. For example, let’s say your sales team is consistently bumping into prospects who are excited about your solution, but are slow to pull the trigger and do business with you.

In this instance, finding a client who felt the same way, but overcame their reluctance and contracted with you anyway, would be a compelling story to capture and share.

Prepping for the Interview

If you’ve ever seen an Oprah interview, you’ve seen a master who can get almost anyone to open up and talk. Part of the reason is that she and her team are disciplined about planning.

Before conducting a case study interview, talk to your own team about the following:

- What’s unique about the client (location, size, industry, etc.) that will resonate with our prospects?

- Why did the customer select us?

- How did we help the client?

- What’s unique about this customer’s experience?

- What problems did we solve?

- Were any measurable, objective results generated?

- What do we want readers to do after reading this case study analysis?

Pro Tip: Tee up your client. Send them the questions in advance.

Providing questions to clients before the interview helps them prepare, gather input from other colleagues if needed, and feel more comfortable because they know what to expect.

In a moment, I’ll give you an exhaustive list of interview questions. But don’t send them all. Instead, pare the list down to one or two questions in each section and personalize them for your customer.

Nailing the Client Interview

Decide how you’ll conduct the interview. Will you call the client, use Skype or Facetime, or meet in person? Whatever mode you choose, plan the process in advance.

Make sure you record the conversation. It’s tough to lead an interview, listen to your contact’s responses, keep the conversation flowing, write notes, and capture all that the person is saying.

A recording will make it easier to write the client’s story later. It’s also useful for other departments in your company (management, sales, development, etc.) to hear real customer feedback.

Use open-ended questions that spur your contact to talk and share. Here are some real-life examples:

Introduction

- Recap the purpose of the call. Confirm how much time your contact has to talk (30-45 minutes is preferable).

- Confirm the company’s location, number of employees, years in business, industry, etc.

- What’s the contact’s background, title, time with the company, primary responsibilities, and so on?

Initial Challenges

- Describe the situation at your company before engaging with us?

- What were the initial problems you wanted to solve?

- What was the impact of those problems?

- When did you realize you had to take some action?

- What solutions did you try?

- What solutions did you implement?

- What process did you go through to make a purchase?

- How did the implementation go?

- How would you describe the work effort required of your team?

- If training was involved, how did that go?

Results, Improvements, Progress

- When did you start seeing improvements?

- What were the most valuable results?

- What did your team like best about working with us?

- Would you recommend our solution/company? Why?

Future Plans

- How do you see our companies working together in the future?

Honest Feedback

- Our company is very focused on continual improvement. What could we have done differently to make this an even better experience?

- What would you like us to add or change in our product/service?

During the interview, use your contact’s responses to guide the conversation.

Once the interview is complete, it’s time to write your case study.

How to Write a Case Study… Effortlessly

Case study writing is not nearly as difficult as many people make it out to be. And you don’t have to be Stephen King to do professional work. Here are a few tips:

- Use the case study structure that we outlined earlier, but write these sections first: company background, challenges, solutions, and results.

- Write the headline, executive summary, future plans, and call-to-action (CTA) last.

- In each section, include as much content from your interview as you can. Don’t worry about editing at this point

- Tell the story by discussing their trials and tribulations.

- Stay focused on the client and the results they achieved.

- Make their organization and employees shine.

- When including information about your company, frame your efforts in a supporting role.

Also, make sure to do the following:

Add Testimonials, Quotes, and Visuals

The more you can use your contact’s words to describe the engagement, the better. Weave direct quotes throughout your narrative.

Strive to be conversational when you’re writing case studies, as if you’re talking to a peer.

Include images in your case study that visually represent the content and break up the text. Photos of the company, your contact, and other employees are ideal.

If you need to incorporate stock photos, here are three resources:

- Deposit p hotos

And if you need more, check out Smart Blogger’s excellent resource: 17 Sites with High-Quality, Royalty-Free Stock Photos .

Proofread and Tighten Your Writing

Make sure there are no grammar, spelling, or punctuation errors. If you need help, consider using a grammar checker tool like Grammarly .

My high school English teacher’s mantra was “tighten your writing.” She taught that impactful writing is concise and free of weak, unnecessary words . This takes effort and discipline, but will make your writing stronger.

Also, keep in mind that we live in an attention-diverted society. Before your audience will dive in and read each paragraph, they’ll first scan your work. Use subheadings to summarize information, convey meaning quickly, and pull the reader in.

Be Sure to Use Best Practices

Consider applying the following best practices to your case study:

- Stay laser-focused on your client and the results they were able to achieve.

- Even if your audience is technical, minimize the use of industry jargon . If you use acronyms, explain them.

- Leave out the selling and advertising.

- Don’t write like a Shakespearean wannabe. Write how people speak. Write to be understood.

- Clear and concise writing is not only more understandable, it inspires trust. Don’t ramble.

- Weave your paragraphs together so that each sentence is dependent on the one before and after it.

- Include a specific case study call-to-action (CTA).

- A recommended case study length is 2-4 pages.

- Commit to building a library of case studies.

Get Client Approval

After you have a final draft, send it to the client for review and approval. Incorporate any edits they suggest.

Use or modify the following “Consent to Publish” form to get the client’s written sign-off:

Consent to Publish

Case Study Title:

I hereby confirm that I have reviewed the case study listed above and on behalf of the [Company Name], I provide full permission for the work to be published, in whole or in part, for the life of the work, in all languages and all formats by [Company publishing the case study].

By signing this form, I affirm that I am authorized to grant full permission.

Company Name:

E-mail Address:

Common Case Study Questions (& Answers)

We’ll wrap things up with a quick Q&A. If you have a question I didn’t answer, be sure to leave it in a blog comment below.

Should I worry about print versions of my case studies?

Absolutely.

As we saw in the CurationSuite and Brain Traffic examples earlier, case studies get downloaded, printed, and shared. Prospects can and will judge your book by its cover.

So, make sure your printed case study is eye-catching and professionally designed. Hire a designer if necessary.

Why are good case studies so effective?

Case studies work because people trust them.

They’re not ads, they’re not press releases, and they’re not about how stellar your company is.

Plus, everyone likes spellbinding stories with a hero [your client], a conflict [challenges], and a riveting resolution [best solution and results].

How do I promote my case study?

After you’ve written your case study and received the client’s approval to use it, you’ll want to get it in front of as many eyes as possible.

Try the following:

- Make sure your case studies can be easily found on your company’s homepage.

- Tweet and share the case study on your various social media accounts.

- Have your sales team use the case study as a reason to call on potential customers. For example: “Hi [prospect], we just published a case study on Company A. They were facing some of the same challenges I believe your firm is dealing with. I’m going to e-mail you a copy. Let me know what you think.”

- Distribute printed copies at trade shows, seminars, or during sales presentations.

- If you’re bidding on a job and have to submit a quote or a Request for Proposal (RFP), include relevant case studies as supporting documents.

Ready to Write a Case Study That Converts?

If you want to stand out and you want to win business, case studies should be an integral part of your sales and marketing efforts.

Hopefully, this guide answered some of your questions and laid out a path that will make it faster and easier for your team to create professional, sales-generating content.

Now it’s time to take action and get started. Gather your staff, select a client, and ask a contact to participate. Plan your interview and lead an engaging conversation. Write up your client’s story, make them shine, and then share it.

Get better at the case study process by doing it more frequently. Challenge yourself to write at least one case study every two months.

As you do, you’ll be building a valuable repository of meaningful, powerful content. These success stories will serve your business in countless ways, and for years to come.

Todd A. Brehe is a professional B2B freelance writer helping SaaS companies create sales-generating case studies, white papers, and blog content. Check out his work or contact him at: https://toddbrehe.com .

Content Marketing

The ultimate toolkit for becoming one of the highest-paid writers online. Premium training. Yours for free.

Written by Todd Brehe

6 thoughts on “how to write a case study: a step-by-step guide (+ examples)”.

Just the guide I needed for case studies! Great job with this one!

Hey Todd, great post here. I liked that you listed some prompting questions. Really demonstrates you know what you’re talking about. There are a bunch of Ultimate Guides out there who list the theories such as interview your customer, talk about results, etc. but really don’t help you much.

Thanks, Todd. I’ve planned a case study and this will really come in handy. Bookmarked.

Very good read. Thanks, Todd. Are there any differences between a case study and a use case, by the way?

Hi Todd, Very well-written article. This is the ultimate guide I have read till date. It has actionable points rather than some high-level gyan. Creating a new case study always works better when (1) you know the structure to follow and (2) you work in a group of 3-4 members rather than individually. Thanks for sharing this guide.

Hi Todd. Very useful guide. I learn step by step. Looking forward to continually learning from you and your team. Thanks

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Latest from the blog.

How to Write a Book in 2024: Everything You Need to Know

How to Create a Swipe File: A Guide for Bloggers & Writers

What is Freelance Copywriting? & How to Get Started in 2024

With over 300k subscribers and 4 million readers, Smart Blogger is one of the world's largest websites dedicated to writing and blogging.

Best of the Blog

© 2012-2024 Smart Blogger — Boost Blog Traffic, Inc.

Terms | Privacy Policy | Refund Policy | Affiliate Disclosure

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 30 January 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organisation, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating, and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyse the case.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

| Research question | Case study |

|---|---|

| What are the ecological effects of wolf reintroduction? | Case study of wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone National Park in the US |

| How do populist politicians use narratives about history to gain support? | Case studies of Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and US president Donald Trump |

| How can teachers implement active learning strategies in mixed-level classrooms? | Case study of a local school that promotes active learning |

| What are the main advantages and disadvantages of wind farms for rural communities? | Case studies of three rural wind farm development projects in different parts of the country |

| How are viral marketing strategies changing the relationship between companies and consumers? | Case study of the iPhone X marketing campaign |

| How do experiences of work in the gig economy differ by gender, race, and age? | Case studies of Deliveroo and Uber drivers in London |

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

Unlike quantitative or experimental research, a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

If you find yourself aiming to simultaneously investigate and solve an issue, consider conducting action research . As its name suggests, action research conducts research and takes action at the same time, and is highly iterative and flexible.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience, or phenomenon.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews, observations, and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data .

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis, with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results , and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyse its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, January 30). Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved 12 August 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/case-studies/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, correlational research | guide, design & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, descriptive research design | definition, methods & examples.

What is case study research?

Last updated

8 February 2023

Reviewed by

Cathy Heath

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

Suppose a company receives a spike in the number of customer complaints, or medical experts discover an outbreak of illness affecting children but are not quite sure of the reason. In both cases, carrying out a case study could be the best way to get answers.

Organization

Case studies can be carried out across different disciplines, including education, medicine, sociology, and business.

Most case studies employ qualitative methods, but quantitative methods can also be used. Researchers can then describe, compare, evaluate, and identify patterns or cause-and-effect relationships between the various variables under study. They can then use this knowledge to decide what action to take.

Another thing to note is that case studies are generally singular in their focus. This means they narrow focus to a particular area, making them highly subjective. You cannot always generalize the results of a case study and apply them to a larger population. However, they are valuable tools to illustrate a principle or develop a thesis.

Analyze case study research

Dovetail streamlines case study research to help you uncover and share actionable insights

- What are the different types of case study designs?

Researchers can choose from a variety of case study designs. The design they choose is dependent on what questions they need to answer, the context of the research environment, how much data they already have, and what resources are available.

Here are the common types of case study design:

Explanatory

An explanatory case study is an initial explanation of the how or why that is behind something. This design is commonly used when studying a real-life phenomenon or event. Once the organization understands the reasons behind a phenomenon, it can then make changes to enhance or eliminate the variables causing it.

Here is an example: How is co-teaching implemented in elementary schools? The title for a case study of this subject could be “Case Study of the Implementation of Co-Teaching in Elementary Schools.”

Descriptive

An illustrative or descriptive case study helps researchers shed light on an unfamiliar object or subject after a period of time. The case study provides an in-depth review of the issue at hand and adds real-world examples in the area the researcher wants the audience to understand.

The researcher makes no inferences or causal statements about the object or subject under review. This type of design is often used to understand cultural shifts.

Here is an example: How did people cope with the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami? This case study could be titled "A Case Study of the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami and its Effect on the Indonesian Population."

Exploratory

Exploratory research is also called a pilot case study. It is usually the first step within a larger research project, often relying on questionnaires and surveys . Researchers use exploratory research to help narrow down their focus, define parameters, draft a specific research question , and/or identify variables in a larger study. This research design usually covers a wider area than others, and focuses on the ‘what’ and ‘who’ of a topic.

Here is an example: How do nutrition and socialization in early childhood affect learning in children? The title of the exploratory study may be “Case Study of the Effects of Nutrition and Socialization on Learning in Early Childhood.”

An intrinsic case study is specifically designed to look at a unique and special phenomenon. At the start of the study, the researcher defines the phenomenon and the uniqueness that differentiates it from others.

In this case, researchers do not attempt to generalize, compare, or challenge the existing assumptions. Instead, they explore the unique variables to enhance understanding. Here is an example: “Case Study of Volcanic Lightning.”

This design can also be identified as a cumulative case study. It uses information from past studies or observations of groups of people in certain settings as the foundation of the new study. Given that it takes multiple areas into account, it allows for greater generalization than a single case study.

The researchers also get an in-depth look at a particular subject from different viewpoints. Here is an example: “Case Study of how PTSD affected Vietnam and Gulf War Veterans Differently Due to Advances in Military Technology.”

Critical instance

A critical case study incorporates both explanatory and intrinsic study designs. It does not have predetermined purposes beyond an investigation of the said subject. It can be used for a deeper explanation of the cause-and-effect relationship. It can also be used to question a common assumption or myth.

The findings can then be used further to generalize whether they would also apply in a different environment. Here is an example: “What Effect Does Prolonged Use of Social Media Have on the Mind of American Youth?”

Instrumental

Instrumental research attempts to achieve goals beyond understanding the object at hand. Researchers explore a larger subject through different, separate studies and use the findings to understand its relationship to another subject. This type of design also provides insight into an issue or helps refine a theory.

For example, you may want to determine if violent behavior in children predisposes them to crime later in life. The focus is on the relationship between children and violent behavior, and why certain children do become violent. Here is an example: “Violence Breeds Violence: Childhood Exposure and Participation in Adult Crime.”

Evaluation case study design is employed to research the effects of a program, policy, or intervention, and assess its effectiveness and impact on future decision-making.

For example, you might want to see whether children learn times tables quicker through an educational game on their iPad versus a more teacher-led intervention. Here is an example: “An Investigation of the Impact of an iPad Multiplication Game for Primary School Children.”

- When do you use case studies?

Case studies are ideal when you want to gain a contextual, concrete, or in-depth understanding of a particular subject. It helps you understand the characteristics, implications, and meanings of the subject.

They are also an excellent choice for those writing a thesis or dissertation, as they help keep the project focused on a particular area when resources or time may be too limited to cover a wider one. You may have to conduct several case studies to explore different aspects of the subject in question and understand the problem.

- What are the steps to follow when conducting a case study?

1. Select a case

Once you identify the problem at hand and come up with questions, identify the case you will focus on. The study can provide insights into the subject at hand, challenge existing assumptions, propose a course of action, and/or open up new areas for further research.

2. Create a theoretical framework

While you will be focusing on a specific detail, the case study design you choose should be linked to existing knowledge on the topic. This prevents it from becoming an isolated description and allows for enhancing the existing information.

It may expand the current theory by bringing up new ideas or concepts, challenge established assumptions, or exemplify a theory by exploring how it answers the problem at hand. A theoretical framework starts with a literature review of the sources relevant to the topic in focus. This helps in identifying key concepts to guide analysis and interpretation.

3. Collect the data

Case studies are frequently supplemented with qualitative data such as observations, interviews, and a review of both primary and secondary sources such as official records, news articles, and photographs. There may also be quantitative data —this data assists in understanding the case thoroughly.

4. Analyze your case

The results of the research depend on the research design. Most case studies are structured with chapters or topic headings for easy explanation and presentation. Others may be written as narratives to allow researchers to explore various angles of the topic and analyze its meanings and implications.

In all areas, always give a detailed contextual understanding of the case and connect it to the existing theory and literature before discussing how it fits into your problem area.

- What are some case study examples?

What are the best approaches for introducing our product into the Kenyan market?

How does the change in marketing strategy aid in increasing the sales volumes of product Y?

How can teachers enhance student participation in classrooms?

How does poverty affect literacy levels in children?

Case study topics

Case study of product marketing strategies in the Kenyan market

Case study of the effects of a marketing strategy change on product Y sales volumes

Case study of X school teachers that encourage active student participation in the classroom

Case study of the effects of poverty on literacy levels in children

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 6 February 2023

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 April 2023

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

Definition and Introduction

Case analysis is a problem-based teaching and learning method that involves critically analyzing complex scenarios within an organizational setting for the purpose of placing the student in a “real world” situation and applying reflection and critical thinking skills to contemplate appropriate solutions, decisions, or recommended courses of action. It is considered a more effective teaching technique than in-class role playing or simulation activities. The analytical process is often guided by questions provided by the instructor that ask students to contemplate relationships between the facts and critical incidents described in the case.

Cases generally include both descriptive and statistical elements and rely on students applying abductive reasoning to develop and argue for preferred or best outcomes [i.e., case scenarios rarely have a single correct or perfect answer based on the evidence provided]. Rather than emphasizing theories or concepts, case analysis assignments emphasize building a bridge of relevancy between abstract thinking and practical application and, by so doing, teaches the value of both within a specific area of professional practice.

Given this, the purpose of a case analysis paper is to present a structured and logically organized format for analyzing the case situation. It can be assigned to students individually or as a small group assignment and it may include an in-class presentation component. Case analysis is predominately taught in economics and business-related courses, but it is also a method of teaching and learning found in other applied social sciences disciplines, such as, social work, public relations, education, journalism, and public administration.

Ellet, William. The Case Study Handbook: A Student's Guide . Revised Edition. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2018; Christoph Rasche and Achim Seisreiner. Guidelines for Business Case Analysis . University of Potsdam; Writing a Case Analysis . Writing Center, Baruch College; Volpe, Guglielmo. "Case Teaching in Economics: History, Practice and Evidence." Cogent Economics and Finance 3 (December 2015). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2015.1120977.

How to Approach Writing a Case Analysis Paper

The organization and structure of a case analysis paper can vary depending on the organizational setting, the situation, and how your professor wants you to approach the assignment. Nevertheless, preparing to write a case analysis paper involves several important steps. As Hawes notes, a case analysis assignment “...is useful in developing the ability to get to the heart of a problem, analyze it thoroughly, and to indicate the appropriate solution as well as how it should be implemented” [p.48]. This statement encapsulates how you should approach preparing to write a case analysis paper.

Before you begin to write your paper, consider the following analytical procedures:

- Review the case to get an overview of the situation . A case can be only a few pages in length, however, it is most often very lengthy and contains a significant amount of detailed background information and statistics, with multilayered descriptions of the scenario, the roles and behaviors of various stakeholder groups, and situational events. Therefore, a quick reading of the case will help you gain an overall sense of the situation and illuminate the types of issues and problems that you will need to address in your paper. If your professor has provided questions intended to help frame your analysis, use them to guide your initial reading of the case.

- Read the case thoroughly . After gaining a general overview of the case, carefully read the content again with the purpose of understanding key circumstances, events, and behaviors among stakeholder groups. Look for information or data that appears contradictory, extraneous, or misleading. At this point, you should be taking notes as you read because this will help you develop a general outline of your paper. The aim is to obtain a complete understanding of the situation so that you can begin contemplating tentative answers to any questions your professor has provided or, if they have not provided, developing answers to your own questions about the case scenario and its connection to the course readings,lectures, and class discussions.

- Determine key stakeholder groups, issues, and events and the relationships they all have to each other . As you analyze the content, pay particular attention to identifying individuals, groups, or organizations described in the case and identify evidence of any problems or issues of concern that impact the situation in a negative way. Other things to look for include identifying any assumptions being made by or about each stakeholder, potential biased explanations or actions, explicit demands or ultimatums , and the underlying concerns that motivate these behaviors among stakeholders. The goal at this stage is to develop a comprehensive understanding of the situational and behavioral dynamics of the case and the explicit and implicit consequences of each of these actions.