- Yale Divinity School

Reflections

You are here, seeking god’s splendor: thoughts on art and faith.

Can beauty be a way to God? How can art deepen the church’s impact? Is art a neglected topic in today’s congregational world? Is beauty in the life of faith a luxury … or a necessity? Such questions animate this Spring issue of Reflections , and we we invited answers from several Yale Divinity School students who have a commitment to the arts. Their replies suggest approaches that will shape future relationships between religion and art. Most of the YDS students featured here are dually enrolled in the Yale Institute of Sacred Music, an interdisciplinary graduate center that educates leaders to engage the sacred through music, worship, and the arts. Located at Sterling Divinity Quadrangle, the ISM operates in partnership with YDS, the Yale School of Music, and other academic units at Yale. (See ism.yale.edu )

What the World Needs Now By Megan Mitchell

In a world of immense suffering, is art a luxury, limited to those with the time and resources to spare? Beauty doesn’t feed people, doesn’t stop wars. What does it do?

I have stood in opulently glorious churches, both enraptured by their beauty yet sick with the awareness that histories of hypocrisy and exploitation lurk beneath the glittering surfaces. In less extreme ways, all churches today face the dilemma of how to allocateresources: “Should we tune the organ, commission a sculpture for the altar, or keep upthe foreign missions fund?”

For Christians trying to follow the example of Christ and the early church by caring for the poor and living simply, a focus on art can seem self-serving. The urgent needs of the world force artists of faith to ask what truly matters in each note, paint stroke, or stanza.

Yet my conviction is that art goes beyond luxury. Art and beauty address the human need for hope. For me, hope is functionally inseparable from beauty, for beauty is a reminder that there is, in the words of Abraham Heschel, “meaning beyond absurdity.”

Beauty helps me believe that divine good does prevail. Seeking to bring the Kingdom of God to earth includes restoring the beauty that is present in creation – and adding to it.

Facilitating public murals in the U.S., Africa, and Haiti, I have come to see the process of collaboration itself as art. The effort of people making a mural together involves creative problem-solving and communication. Participants must learn to voice their own opinions but also be willing to make sacrifices for the unity of the whole. Art-making is metaphorically linked to other life-building processes – and helps people tap into the transformative resources already present within themselves.

I saw this happen last summer in neighborhoods of Brooklyn, the Bronx, and Queens, where I worked with Groundswell, an organization that employs high-school and college-age youth to create murals in their communities that respond to social justice issues they face. I saw these young artists take a new kind of ownership of their neighborhoods and histories and develop new ideas for their futures.

Art is about making space – both physical and mental – for listening, searching, and expressing. Art cultivates the ability to imagine a future and so transcend the present moment. This is inherently hopeful.

In her poem “Upstream,” Mary Oliver writes, “attention is the beginning of devotion.” Art gives us the space for attention, which looks quite a lot like prayer. That’s what the world needs now: space to take notice of each other, our own souls, and the still small voice of the Lord who calls but will not force us to hear if we do not desire to listen.

To give hope to the hurting, the church must be invested in the question of what is truly beautiful – both in the work we create and the way we create.

Megan Mitchell will graduate in May with an M.A.R. in religion and the arts. She earned a B.A. in Community Art and Missions from Wheaton College.

God at the Gallergy By Jeremy Hamilton-Arnold

If ever I forget art’s capacity for transcendence, I simply return to work. My place of employment is a sacred treasury – the Yale University Art Gallery.

There I can rely upon some giants of Western Modernism: Van Gogh, Kandinsky, Mondrian, Rothko. All have given the world paintings that inspire near-universal adoration, and all have expressed, through both pigment and the written word, spiritual motivations for their art. Knowing their intentions, I am keen to look in their daubs and hues for evidence of divinity.

I find the sacred wading in the art of many other greats at the museum too, regardless of the artist’s “spiritual” stance. To me, the sacred resides in the congress of colors in Helen Frankenthaller’s canvas, in the powerful gaze of Kerry James Marshall’s painted artist, in the dingy soft glow of light in Joseph Stella’s Brooklyn Bridge. The sacred is felt in the serious humor of Duchamp, the hpeful lament of Anselm Kiefer, and the daring of Picasso.

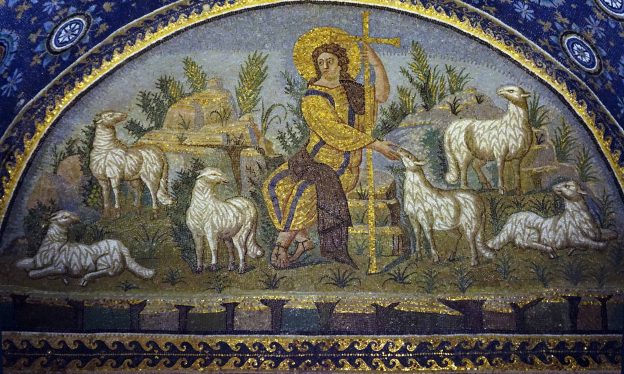

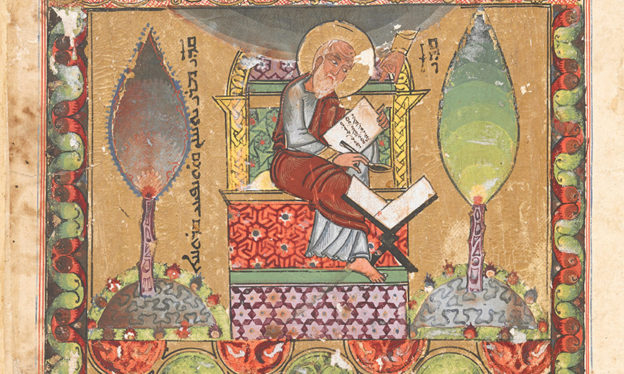

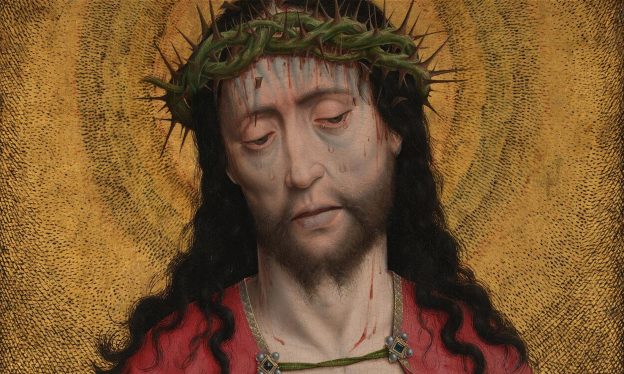

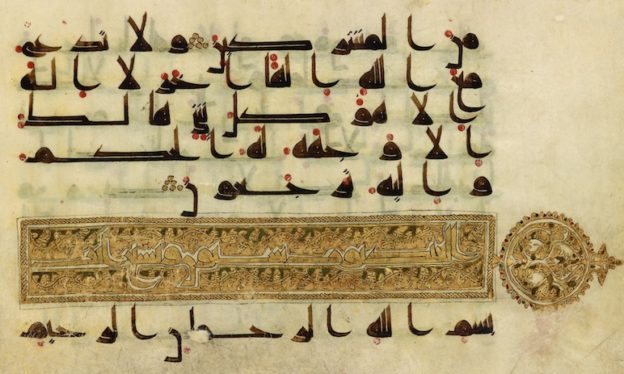

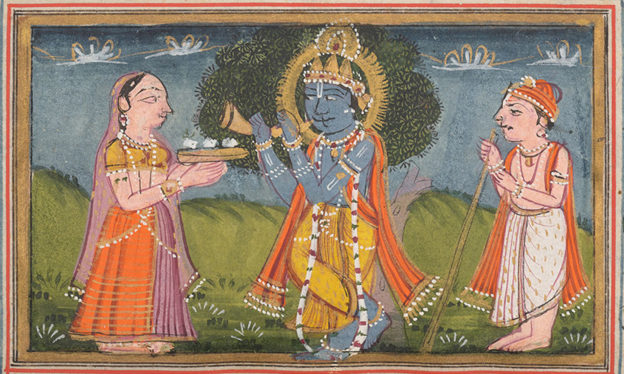

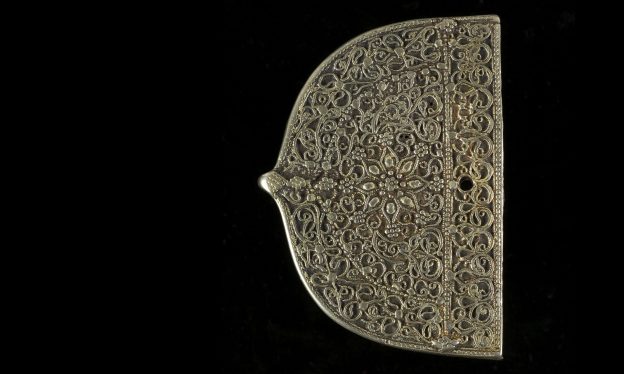

Divinity (of course!) abounds in the devotion and innovation of the early European icon-painters. The sacral motivations of religious individuals and communities beyond the West are abundant in the museum as well – around virtually every corner.

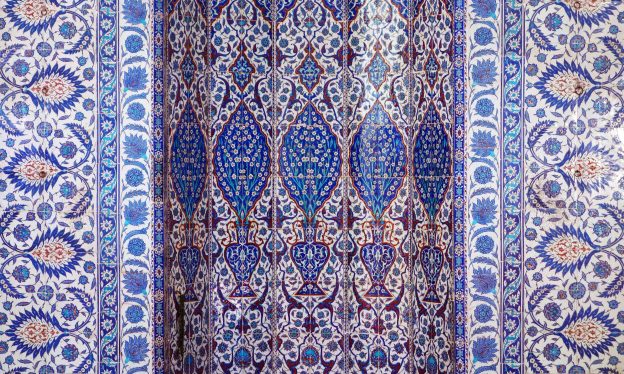

I’m not alone in this experience. Religious groups come into the Gallery all the time. They seek the religiously motivated and motivating – the ancient synagogue tiles from Dura Europos, the Islamic miniature paintings from northern India, the Boddhisatva Guanyin from China, the Baga D’mba mask from Guinea.

Even those who do not come to “see God” still venerate their favorite artists and works. They uplift the art museum space as “sacred,” comporting themselves with religious-like postures. They hush and clasp their hands before dimly lit images. The works seem to elicit awe and reverence.

Ultimately, however, I see the divine most clearly not in the works themselves, but in the budding curiosity and unfurling excitement of young visitors – the people I lead on teaching tours throughout the museum. In their expressed wonder before Bierstadt’s Yosemite Valley, Glacier Point Trail and their imaginative narrations at seeing Hopper’s Sunlight in a Cafeteria, I see the sacred.

For you who seek to bring art to your religious communities, I encourage you to find ways to display art on the walls of your place of worship (reproductions are an option!). Support local artists. Encourage creativity among your own congregants.

I especially urge you to bring your community to the art: Visit (repeatedly) your local art museums and galleries. Once there, find something new; spend more time with fewer works; leave the labels until the very end; converse with one another; ask difficult questions; sketch in silence; linger as long as you are able with a work you find boring, irksome, or downright ugly – and do the same with a work you love. Few spaces can match the power of art museums, those revered storehouses of the sacred.

Jeremy Hamilton-Arnold plans to graduate next year as an M.A.R. in religion and the visual arts and material culture. He has a B.A. from Texas Christian University in Fort Worth, TX., and an M.A. from Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, CA.

Re-envisioning the Gallery by Meredith Jane Day

One Saturday last December in New York City, I sat in a circle with an intimate group of 20 souls preparing for Advent. At an early-20th century Episcopal retreat center on the Upper East Side, we spent nearly eight hours together in a wood-carved library, hearing only the faintest of horn honks from the frantic taxi drivers on Park Avenue.

Our curator for the day showed us photographs of famous paintings from the nearby Metropolitan Museum of Art while we methodically spent time in silence, wonder, and discussion of the pieces. I still remember the way Caravaggio’s “Holy Family” glowed in the afternoon light. Something about Mary’s penetrating black eyes and young Jesus’ crucifix-like posture engulfed me in empathy for their future pain.

The room was full of brilliant seminarians, clergy, and academics, but it was the art that gave us something we could not have offered on our own. It provided a spiritual avenue for confronting our humanity, at the same time assuring us of a mysterious glory within.

A few weeks later, I found myself in a much different place – near the stage of the candlelit Bluebird Cafe in Nashville, TN. I sat with a table of friends (Jack Daniel included) to watch a round of four local songwriters play some of their most treasured music. When Lori McKenna sang her first song, the air in the room turned electric, and the space was transformed. A few songs went by before Barry Dean gripped the audience with a new tune:

Now my heart is falling apart like a confession

My prayers are making a church out of this room

My tears, salt of the past and sweet redemption

I’ve been standing like a mountain

I was just waiting to be moved.**

I managed to break away from the enchantment long enough to scan the room to see that every eye was salty, but clear. It was grace, I think – the kind that can’t quite be articulated for fear that, in doing so, something might be left behind.

When human beings, as creations of God, create or encounter the creativity of others, something full circle happens. We suddenly occupy a holy space that connects us to our humanity and yet is permeated by God’s glorious and merciful presence.

Whether it takes place in church, a retreat center in NYC, or a bar in Nashville doesn’t seem to matter so much. It is the way the Spirit moves through art that grips me most tightly. No matter the kind of art, it provides a way forward during this often oversaturated, overstated, and unimaginative moment in the American church. Art can serve as a means to re-translate and re-envision the story of faith and redemption for this world.

Thanks be to (this creative) God.

Meredith Jane Day has a background in singing/songwriting, poetry, theatre creative writing, and theology/arts integration. She will graduate this spring with an M.Div. degree and is a member of the Yale Institute of Sacred Music. For more information see Meredithjaneday.com or tweet her @mereday.

** Barry Dean, Natalie Hemby, and Sean McConnell, “Waiting to Be Moved,” Creative Nation Publishing, Nashville, 2014 .

Glimpsing the Light By Tyler Gathro

By the time I was six years old I knew I wanted to be an artist. I devoted myself to artmaking with a concentrated ardor, while simultaneously growing in my Mormon Christian faith. My spirituality became the very center of my life, around which art revolved.

In 2009, after serving for two years as a full-time missionary to the people of Los Angeles, I returned to my studies at the Cooper Union School of Art in New York City to continue my passion as an artist.

However, after two years of strengthening families, helping people overcome addictions and get jobs, doing community service, and being a direct influence for good in people’s lives, creating art seemed pointless. A dead Damien Hirst tiger shark in formaldehyde or an Andy Warhol can of soup will not save the soul of anyone today or tomorrow. I struggled to understand the spiritual role of art and how it could be of any real use when millions around the world were suffering and needed peace and a helping hand. I sought guidance from God. I fasted and prayed for weeks, wanting to know what to do and how to proceed as a self-declared artist. Around this time I had profound experiences and received revelation regarding the subject, and yet it would be futile to attempt to explain the unexplainable. However, one thing is for sure – I have learned that the visual impacts the spiritual.

With this knowledge, I began to create work that would visually express and capture the spiritual experiences I had and the revelation I had received. It was both a spiritual process for myself and a hope that this art could bring spiritual experiences for others.

You see … it is as if there is a world of ideal beauty, and between it and me hangs only a veil. Often that veil hangs motionless, until that beautiful moment when the wind blows and the curtain flutters aside. It is then that I catch a glimpse of the celestial world beyond – only a glimpse – but in that moment when all my physical senses seem to be turned off, my hair stands on end while a transcendent feeling flows through me, lifting me off the ground and filling me with light.

These glimpses of light and the creation of this artwork have enriched my Christian faith and brought me closer to God. This is what elevates me in life and drives me to seek the ideal.

Jacksonville native Tyler Gathro will graduate next year with an M.A.R. in religion and the visual arts and material culture. He holds a Bachelors of Fine Art from the Cooper Union School of Art in New York City. A devout Mormon, he is looking forward to marrying his fiancé this summer and working as an artist and photographer post-graduation.

Don’t forget your Cane by Mark Koyama

Whoever, then, thinks that he understands the Holy Scriptures, or any part of them, but puts such an interpretation upon them as does not tend to build up this twofold love of God and our neighbor, does not yet understand them as he ought. – St. Augustine

Monday morning I’m up and out before daybreak to be sure to beat the Hartford traffic as I head south from western Massachusetts to my weekday abode in Bellamy Hall at YDS. From that moment on, my doings are governed by the myriad imperatives of Prospect Street – the humming precincts of Sterling Quad, with its lectures and worship services, seminars and colloquia, discussion sections, intersections and collisions.

Friday, late, I shove the week’s laundry in the backseat of my ’97 Nissan (along with a capricious assortment of tomes liturgical), and hightail-it north into the Massachusetts hilltowns where, at length, I will turn with a sigh of relief onto Greenfield Road. The boys are asleep, but my wife is still up. She is pleased to see me. In my absence, the compost has been fermenting and the cat boxes have taken a decided turn for the worse.

The word “commute” comes from the Latin commutare , which combines com (“altogether”) and mutare (“to change”). Yes, I commute between two worlds, but I try to mitigate the “altogether” bit. One hundred miles may separate the storied halls of Yale Divinity School from the child-begrimed walls of my circa-1875 farmhouse, and an even greater gulf may divide the ambient discourses of my two sitz im leben. Nevertheless I insist that the two worlds do, and indeed, must inform each other if I am to succeed in my earnest hope to throw a stole over my shoulders and process down the center aisle as an ordained minister of the Christian faith.

Each world is too full of delicate wonder to be deprived of the other.

During the last two years of my mother’s life, I was her healthcare advocate, her caretaker and finally, her nurse. At that time, a phrase often came out of my mouth:

“Don’t forget your cane …”

These words remain with me today, not for their practical application, but for their spiritual frankness – their quiet insistence that love governs. Good theology – the habit of mind behind good Christian ministry – follows from a Don’t Forget Your Cane biblical hermeneutic.

The same principle applies when I write sonnets. I search for language that quietly insists on telling of the twofold love of God and neighbor.

A Sonnet for An Old Farmhouse at Bedtime

And when, at last, the boys begin to snore

I head downstairs, turn off the kitchen light,

Make sure the dog’s been let in for the night

And throw the deadbolt on the mudroom door.

There’s a local squirrel who makes offshore

Deposits in our ceiling, out of sight

Of the cats, who flick their tails left to right

Like irk’d Egyptian goddesses of war.

Shuffling round in my pajama vestments,

I settle all these final farmhouse cares –

These fitful little bedtime sacraments.

And lying down, I hear the closing prayers

Performed by those unwitting penitents –

The dog’s long claws click-clicking up the stairs.

Mark Koyama M.Div. ’15 studied Buddhism at Bates College, has an M.A. from Union Theological Seminary and an M.F.A. in fiction from UMass-Amherst. He plans to become a United Church of Christ minister.

The World’s Collective Spirit By Yolanda Richard

When I ponder my ancestral material memory, I think of Islamic etchings in the sand of Hispaniola, clay pots fashioned by dark hands dewed with labor’s sweat, cosmic ancestral symbols weaved over and under Catholic crosses, Protestant hymnals drumming to the beat of audible spirit, West African dress that reminds us where we were birthed: In-between cultures.

As a Haitian American woman, my intersectional identity was only obliquely echoed when I navigated the halls of the usual “well-curated” gallery. Leisurely walks through such spaces typically consigned me to African Art collections and modern pieces depicting the black body and traditional renditions of the black experience. My journey to a deeper love for material culture of all traditions had a rough start.

I entered the world of visual art filled with curiosity, seeking models for engaging material culture that resonated with me. Instead, I was met with the many clichés of the art world. I encountered visitors who commodified their gallery experience as intellectual capital, a way to reinforce their own elitism. I witnessed people approach famous works with vague intimidation or over-excitement, stirred by awareness of the work’s monetary value, not the work’s aesthetic beauty or radical message.

I became privy to the dissonance between gallery culture and an authentic engagement with the art. For a while, I simply mimicked the cadences of “gallery goers.” Hands glued behind the back, backs crooked forward, curved necks attempting at angles to see “everything” – the frame, the paint, the cracks in the panel, the exposed fibers of the canvas, the second layer of varnish that makes you cringe, and finally the label.

This experience eerily translated into a monolithic construction of history. It felt flattened, devoid of faith. Sadly, the impression persists that one must know about art before one can engage with it. Or we expect curators and docents to draw interpretive lines for us. And when they don’t, we are left feeling cheated or confused. Overall, gallery spaces felt more like an intellectual exercise than an exercise of the soul.

I needed a new lens.

In my final year at YDS an internship at the Yale Chaplain’s Office allowed me to explore interfaith conversation within the context of art. I began organizing small group interfaith discussions in front of religious pieces at the Yale Art Gallery. These campus dialogues gave me a new intercultural perspective – weaving me into the cloth of the fabric of human history, making my engagement with art an exercise of my mind, my heart, and my soul.

I began listening – to the story of the work encased in its visual presentation, historical setting, and the artist’s intent. I began questioning – the curator, the artist, and myself. I began learning – how to linger with the art for more than a few seconds and challenge my inclination to generalize whole collections unfamiliar to me. I began conversing – through time, culture, and faith.

Art is the human story of how we have connected with God and imagined the world around us. It is the preservation of the world’s collective spirit in all of its complexity. Interfaith dialogue and art have allowed me to stretch my gaze, connecting me to those beyond a society’s ostensible barriers.

Yolanda Richard graduates with an M.Div. in May. She has served as a Wurtele Gallery Teacher at the Yale University Art Gallery for the past three years, teaching K-12 students from original works of art. After graduation, Yolanda will serve as the Earl Hall Chaplaincy Fellow at Columbia University, focusing on interfaith dialogue among undergraduates.

Rejecting the “Beautiful” By Joshua Sullivan

Step into a gallery or the museum, and a familiar response (at least from my Christian parents) is soon heard: “How is that art?” or “ I could do that!” or “Well, that’s just offensive!”

The two worlds of “fine arts” and “church” have loomed large as stout opponents in my life. Both make demands on my intellectual and spiritual outlook.

The artist’s role as “questioner” and “critic,” I thought, would bar me from ever playing a part in a Christian community. Likewise I feared that being a “confessional” Lutheran would strip me of my credentials as an artist. Yet this dichotomy between fine artist and person of faith is a false one. As a Christian and an artist, I am fascinated by the tension between individual and community. I am interested in the range of non-linguistic communication that visual works can achieve.

It would be foolish to attempt to define the entire range of contemporary fine arts, but I venture to say that much of it now has far more to do with critical cultural dialogue and the material qualities and substances of art than any Platonic or Enlightenment- style quest for the “beautiful.” Churches could take a lesson from this modern insight. Churches hastily turn away from contemporary fine art because of a hostility to art that isn’t “beautiful” by some traditional definition.

But a church’s visual culture itself is not outside a working notion of “fine art” – all production of visual materials in any given community is art. It is a Christian community’s responsibility to take ownership of its visual cultures (be it architecture, carpet color, stained glass, or Sunday school crafts). Taking ownership means understanding the reasons it decided on such visual material. It means giving it prominence as a mode of group intelligibility rather than as objects of “beauty.” An “amateur” piece of artwork produced by a church and a nihilistic piece of work hung in a gallery are on equal footing as modes or vehicles of communication.

The plethora of visual matter in the Christian community’s life – the graphic design of Sunday bulletins, the sanctuary’s architecture, that mainstay portrait of Jesus from the 60s in the church lounge, the little cotton ball lambs made by the preschool kids – are not outside the purview of the fine arts, regardless of their “beauty” or “ugliness.” The church is not off the hook!

Philip Guston’s paintings are “ugly” on purpose. Marina Abramovic`’s performance works are antagonisitc and transgressive. Jenny Holtzer’s installations are terse and scathing. What these and other artists have, and what perhaps the church often lacks, is a razor-sharp grasp of the milieus they are communicating in and about.

Christian communities can take heart by rejecting the “beautiful” as an end in itself. Beauty, like God, will show up when and if it chooses. Visual culture, whether in the gallery or the sanctuary, is about a dialectical relationship between a creator and a community of viewers, not the reign of a pre-existing idea of beauty.

As Karl Barth noted in his Church Dogmatics , “God may speak to us through Russian communism, through a flute concerto, through a blossoming shrub or through a dead dog. We shall do well to listen to [God] if [God] really does so.”

A graduate of the Rhode Island School of Design, Joshua Sullivan will receive an M.Div. degree from YDS in 2016. Experienced as a painter, musician, and conceptual artist, he was Visual Arts Minister at Marquand Chapel this year. He is pursuing ordination in the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.

Beauty Begets Beauty By Jon Seals

I heard it said once that we don’t truly remember an event, place, or person – rather, we only remember the ways in which we remembered them the last time they were recalled. Our memories become copies of copies, and with each recollection comes a loss in clarity and accuracy. As a visual artist, I’ve given a lot of fearful thought to that fragile, degenerative condition: we are only as good as our last memory. Or so I thought.

My recent quest through the literary epic tradition has taught me different. (Important to me was the YDS course “Human Image: Classical and Biblical Traditions,” taught by Peter Hawkins.) From Gilgamesh to Homer’s Odyssey , Virgil’s Aeneid , Augustine’s Confessions , and Dante’s Inferno , epics reveal themselves to be expansive re-imaginings of what it means to be human in relation to others and to a divine being. Through their revelatory example, I’ve learned the truth that all of life is a collage of sorts – an experience of recollection not degenerative but regenerative.

I n her 1999 book On Beauty and Being Just , Elaine Scarry wrote that “beauty brings copies of itself into being,” so that beauty begets beauty. She quotes Ludwig Wittgenstein, “When the eye sees something beautiful, the hand wants to draw it.” Clearly this finds expression in the evolution of the epic. Instead of eclipsing or deteriorating the layer beneath, new versions of the epic build on one another, through twists and turns in fresh and interesting ways, revealing the vast complexity of human experience. With each new edition, the epic tradition is enlarged.

What of those big themes of the epic journey – sorrow, pain, and death? I know only a bit of suffering, but it is real and I am learning through it. I had my own descent or katabasis when I was brought low by the death of my brother. In my encounter with his death, I have learned some things crucial to being alive – mostly that faith, art, and others are the only things worth living for. Each of these is knit together and eternal. I am beginning to think of my art as less my own and more as an extension of others around me. Somewhere in the transaction of involving myself creatively with the lives of others I learn more of the presence and character of God.

My art is not a distraction or an entertainment. It is my way through. When I relinquish control of the materials I’m using and allow the spirit of creation to channel through me after intense bouts of struggle, the work produces a powerful catharsis. To achieve this outcome, both the inhale of my doing and the exhale of my giving in are necessary. In many of my drawings I leave behind pentimenti – repentances in Italian – as I work, evidence of where I have been on the paper or canvas, so that I can see the process of building up, adjusting, and making both mistakes and corrections as I go along. Pentimenti keep me honest.

One of the alluring qualities of epic literature is that it can be at once local and global, deeply personal and vastly communal. Whether I work with paint, graphite, collaged paper, or other materials, this is my aspiration too.

Jon Seals has an M.F.A. degree in painting from Savannah College of Art and Design, and worked for seven years as chair of the visual art department at a college prep school in Clearwater, FL. His artwork has been widely exhibited. He graduates from YDS in May with an M.A.R. in religion and the visual arts and material culture, with dual enrollment at the ISM.

The Eros Divine By Timothy D Cahill

Beauty is vain, says Proverbs. Beauty is truth, says Keats. To begin, I make my own list of likenesses: Of beauty as order, as harmony, as clarity. Of beauty as vigor and compassion, justice and faith. Of beauty as mystery. Beauty as grace. But my aim is not to define beauty. I want to stand in its vastness.

To the reasonable mind, my claims are outlandish. The Enlightenment settled the question long ago, drawing a distinction between the tame allure of the “beautiful” and the bracing wildness of the “sublime.” (Yeats undid this when he wrote of “a terrible beauty,” but no matter.) In the middle of the last century, painter Barnett Newman became the voice of our age when he declared, “The impulse of modern art is the desire to destroy beauty.” He was speaking on behalf of the masters who had blazed his trail, from Manet to Picasso, and of his own avant-garde confrères (Pollack, de Kooning, et. al.), and too, for waves of future MFAs. But suspicion of beauty is not restricted to artists alone. We sing of purple mountain majesties, but the churchy sentimentalities of America the Beautiful (the lyrics were first published in a weekly called The Congregationalist ) cannot resist modernity’s ironic derision. There is something grandiose about beauty that rubs against the American grain. My working-class relations rarely used the word, preferring the leveling action of the banal: A grand vista was “nice,” a starry night “pretty,” a comely face “good-looking.”

As compensation, from the chromium brightness of Cold War-era cars to the brushed aluminum of the Apple Store, America domesticated beauty to a cash crop of glamor. (What is more unbeautiful than Project Runway? ) In 1949, Barnett Newman sought to destroy beauty; by the 1960s, Andy Warhol just laughed at it. Who can speak of beauty today without some frisson of self-consciousness?

So where do I come off with my pretensions? I am not as interested in what beauty is as what it does.

Beauty sparks desire. Observe how everything that debases us is devoid of beauty. Blight in its indifference, greed in its cruelty, vengeance in its blindness – all undercut aspiration and disorder appetite. Yet something of virtue sticks to the beautiful. As

Plato and Dante both knew, even carnal lusts may point toward nobler instincts. Base impulses are unexamined expressions of the soul’s instinct for wholeness. Beauty is the juice of the good – the illuminating desire, the eros divine. It always points in the same direction, toward love-in-action.

Beauty cannot feed the hungry, prevent disease, cure injustice. Cynics rightly observe it does not stop the carnage of war. Yet as modernist critiques become more threadbare, we better understand beauty’s necessity. Destroy the beautiful and our humanity erodes too. Compassion, generosity, praise all atrophy, and by slow degrees a capacity for the suffering of others increases. Our eyes, actions, and ideals affirm one truth. Before we made beauty, beauty made us.

Timothy D. Cahill is a cultural journalist and commentator. He was formerly arts correspondent and photography critic for The Christian Science Monitor, and is a past Fellow with the PEW National Arts Journalism Program at Columbia University. In 2008, he founded a non-profit initiative to engage contemporary art with values of compassion ethics. He is enrolled at the ISM and Yale Divinity School (M.A.R. in religion and the arts, 2016).

Spiritual Alchemies By Robert Pennoyer

As a native New Yorker from a religious-but-not-spiritual family, I enjoyed an unremarkable religious upbringing. What shattered familiar molds and made God credible was my artistic exposure. As a boy, I spent five years singing in the children’s chorus of the Metropolitan Opera. Most days, after school (and frequently during it), I’d leave my classroom, cross Central Park, and get to work making music with some of the world’s greatest musicians. Onstage at the Met, performing in a production of Cavalleria Rusticana, I experienced the first of those unexpected, overwhelming moments when the world’s capacity for beauty, love, and goodness seemed so ripe and so real that it could only be a sign of the givenness of our existence and a hint of its giver.

But if my musical experience suggested a spiritual dimension to the universe, it was poetry that rescued my faith in it from disillusion, a kind of Death by Church. There seemed an unbridgeable gulf between what I’d experienced at the Met and what I was experiencing in the church of my youth. My church’s vocabulary of faith seemed full of stale words, cheapened by overuse and calcified by overconfidence about what they meant. (I’d blame adolescent obstinacy for my resistance to many formulations of faith expressed in church, but age hasn’t cured me. I remain allergic to certitude and find it, in most forms, morally suspect and aesthetically stifling.)

After leaving home to attend an Episcopal boarding school, I discovered in The Book of Common Prayer words I didn’t quite understand arranged in cadences of stunning musicality, and the combination of sound and sense made for a strange alchemy: The ineffable opacity of God lifted, or seemed to, if only for brief moments. Such was poetry’s effect on me, and it wasn’t long before I was regularly turning to literary accounts of belief and unbelief that matched my experiences and made my halting faith feel less lonely.

W. H. Auden called poetry “the clear expression of mixed feeling.” That ability to hold together dissonant meanings, intuitions, and beliefs has allowed poetry to give expression to my faith – and to enrich it. My time at Yale and in the ISM has affirmed what I’d learned by accident – that music can point us towards God; that poetry can revivify our tired language of faith; and that beauty can express and reveal the wondrous love of God.

Robbie Pennoyer grew up singing in the children’s chorus of the Metropolitan Opera and juggling in Central Park. He has an English degree from Harvard, where he composed musical comedies and co-founded S.T.A.G.E., an after-school theater program for inner-city children. He graduates with an M.Div. next year and is pursuing Episcopal ordination.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

The reformation.

Erasmus of Rotterdam

Hans Holbein the Younger (and Workshop(?))

Martin Luther (1483–1546)

Workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder

- The Last Supper

Designed by Bernard van Orley

The Fifteen Mysteries and the Virgin of the Rosary

Netherlandish (Brussels) Painter

Albrecht Dürer

Four Scenes from the Passion

Follower of Bernard van Orley

Friedrich III (1463–1525), the Wise, Elector of Saxony

Lucas Cranach the Elder and Workshop

Martin Luther as an Augustinian Monk

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Johann I (1468–1532), the Constant, Elector of Saxony

The Last Judgment

Joos van Cleve

Chancellor Leonhard von Eck (1480–1550)

Barthel Beham

Anne de Pisseleu (1508–1576), Duchesse d'Étampes

Attributed to Corneille de Lyon

Virgin and Child with Saint Anne

Christ and the Adulteress

Lucas Cranach the Younger and Workshop

The Calling of Saint Matthew

Copy after Jan Sanders van Hemessen

Christ Blessing the Children

Satire on the Papacy

Melchior Lorck

Christ Blessing, Surrounded by a Donor Family

German Painter

Jacob Wisse Stern College for Women, Yeshiva University

October 2002

Unleashed in the early sixteenth century, the Reformation put an abrupt end to the relative unity that had existed for the previous thousand years in Western Christendom under the Roman Catholic Church . The Reformation, which began in Germany but spread quickly throughout Europe, was initiated in response to the growing sense of corruption and administrative abuse in the church. It expressed an alternate vision of Christian practice, and led to the creation and rise of Protestantism, with all its individual branches. Images, especially, became effective tools for disseminating negative portrayals of the church ( 53.677.5 ), and for popularizing Reformation ideas; art, in turn, was revolutionized by the movement.

Though rooted in a broad dissatisfaction with the church, the birth of the Reformation can be traced to the protests of one man, the German Augustinian monk Martin Luther (1483–1546) ( 20.64.21 ; 55.220.2 ). In 1517, he nailed to a church door in Wittenberg, Saxony, a manifesto listing ninety-five arguments, or Theses, against the use and abuse of indulgences, which were official pardons for sins granted after guilt had been forgiven through penance. Particularly objectionable to the reformers was the selling of indulgences, which essentially allowed sinners to buy their way into heaven, and which, from the beginning of the sixteenth century, had become common practice. But, more fundamentally, Luther questioned basic tenets of the Roman Church, including the clergy’s exclusive right to grant salvation. He believed human salvation depended on individual faith, not on clerical mediation, and conceived of the Bible as the ultimate and sole source of Christian truth. He also advocated the abolition of monasteries and criticized the church’s materialistic use of art. Luther was excommunicated in 1520, but was granted protection by the elector of Saxony, Frederick the Wise (r. 1483–1525) ( 46.179.1 ), and given safe conduct to the Imperial Diet in Worms and then asylum in Wartburg.

The movement Luther initiated spread and grew in popularity—especially in Northern Europe, though reaction to the protests against the church varied from country to country. In 1529, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V tried, for the most part unsuccessfully, to stamp out dissension among German Catholics. Elector John the Constant (r. 1525–32) ( 46.179.2 ), Frederick’s brother and successor, was actively hostile to the emperor and one of the fiercest defenders of Protestantism. By the middle of the century, most of north and west Germany had become Protestant. King Henry VIII of England (r. 1509–47), who had been a steadfast Catholic, broke with the church over the pope’s refusal to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, the first of Henry’s six wives. With the Act of Supremacy in 1534, Henry was made head of the Church of England, a title that would be shared by all future kings. John Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian Religion (1536) codified the doctrines of the new faith, becoming the basis for Presbyterianism. In the moderate camp, Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam (ca. 1466–1536), though an opponent of the Reformation, remained committed to the reconciliation of Catholics and Protestants—an ideal that would be at least partially realized in 1555 with the Religious Peace of Augsburg, a ruling by the Diet of the Holy Roman Empire granting freedom of worship to Protestants.

With recognition of the reformers’ criticism and acceptance of their ideology, Protestants were able to put their beliefs on display in art ( 17.190.13–15 ). Artists sympathetic to the movement developed a new repertoire of subjects, or adapted traditional ones, to reflect and emphasize Protestant ideals and teaching ( 1982.60.35 ; 1982.60.36 ; 71.155 ; 1975.1.1915 ). More broadly, the balance of power gradually shifted from religious to secular authorities in western Europe, initiating a decline of Christian imagery in the Protestant Church. Meanwhile, the Roman Church mounted the Counter-Reformation, through which it denounced Lutheranism and reaffirmed Catholic doctrine. In Italy and Spain, the Counter-Reformation had an immense impact on the visual arts; while in the North , the sound made by the nails driven through Luther’s manifesto continued to reverberate.

Wisse, Jacob. “The Reformation.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/refo/hd_refo.htm (October 2002)

Further Reading

Coulton, G. G. Art and the Reformation . 2d ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1953.

Koerner, Joseph Leo. The Reformation of the Image . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

Additional Essays by Jacob Wisse

- Wisse, Jacob. “ Northern Mannerism in the Early Sixteenth Century .” (October 2002)

- Wisse, Jacob. “ Prague during the Rule of Rudolf II (1583–1612) .” (November 2013)

- Wisse, Jacob. “ Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) .” (October 2002)

- Wisse, Jacob. “ Burgundian Netherlands: Court Life and Patronage .” (October 2002)

- Wisse, Jacob. “ Burgundian Netherlands: Private Life .” (October 2002)

- Wisse, Jacob. “ Pieter Bruegel the Elder (ca. 1525–1569) .” (October 2002)

Related Essays

- Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

- Baroque Rome

- Elizabethan England

- The Papacy and the Vatican Palace

- The Papacy during the Renaissance

- Abraham and David Roentgen

- Ceramics in the French Renaissance

- The Crucifixion and Passion of Christ in Italian Painting

- European Tapestry Production and Patronage, 1400–1600

- Genre Painting in Northern Europe

- The Holy Roman Empire and the Habsburgs, 1400–1600

- How Medieval and Renaissance Tapestries Were Made

- Late Medieval German Sculpture: Images for the Cult and for Private Devotion

- Monasticism in Western Medieval Europe

- Music in the Renaissance

- Northern Mannerism in the Early Sixteenth Century

- Painting the Life of Christ in Medieval and Renaissance Italy

- Pastoral Charms in the French Renaissance

- Patronage at the Later Valois Courts (1461–1589)

- Pieter Bruegel the Elder (ca. 1525–1569)

- Portrait Painting in England, 1600–1800

- Portraiture in Renaissance and Baroque Europe

- Profane Love and Erotic Art in the Italian Renaissance

- Sixteenth-Century Painting in Lombardy

List of Rulers

- List of Rulers of Europe

- Central Europe (including Germany), 1400–1600 A.D.

- Central Europe (including Germany), 1600–1800 A.D.

- Eastern Europe and Scandinavia, 1400–1600 A.D.

- France, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Great Britain and Ireland, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Iberian Peninsula, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Low Countries, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Rome and Southern Italy, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Venice and Northern Italy, 1400–1600 A.D.

- 16th Century A.D.

- 17th Century A.D.

- The Annunciation

- Baroque Art

- Central Europe

- Central Italy

- Christianity

- The Crucifixion

- Gilt Silver

- Great Britain and Ireland

- High Renaissance

- Holy Roman Empire

- Literature / Poetry

- Madonna and Child

- Monasticism

- The Nativity

- The Netherlands

- Northern Italy

- Printmaking

- Religious Art

- Renaissance Art

- Southern Italy

- Virgin Mary

Artist or Maker

- Beham, Barthel

- Cranach, Lucas, the Elder

- Cranach, Lucas, the Younger

- Daucher, Hans

- De Lyon, Corneille

- De Pannemaker, Pieter

- Dürer, Albrecht

- Holbein, Hans, the Younger

- Tom Ring, Ludger, the Younger

- Van Cleve, Joos

- Van Der Weyden, Goswijn

- Van Hemessen, Jan Sanders

- Van Orley, Bernard

Tools for understanding religion in art

For millennia, images have acted as a bridge to the invisible and the transcendent.

Beginner's guide

The five major religions (by number of modern adherents): Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism and Judaism.

- The five major world religions

- A brief history of religion in art

Christianity

- View all content

The biblical Jesus, described in the Gospels as the son of a carpenter, was a Jew and a champion of the underdog.

Christianity, an introduction

The Christian Bible

Standard scenes from the life of Christ in art

Who's who? Recognizing saints...

The audacity of Christian art

Islam was founded by Muhammad, a 6th century merchant from the city of Mecca, in modern-day Saudi Arabia. Mecca was then a well-established trading city. The Kaaba, in Mecca, is the focus of pilgrimage and prayer for muslims around the world.

Introduction to Islam

Five pillars of Islam

Introduction to mosque architecture

Hinduism is neither monotheistic nor is it polytheistic. Hinduism’s emphasis on the universal spirit, or Brahman, allows for the existence of a pantheon of divinities while remaining devoted to a particular god.

Hinduism and Buddhism, an introduction

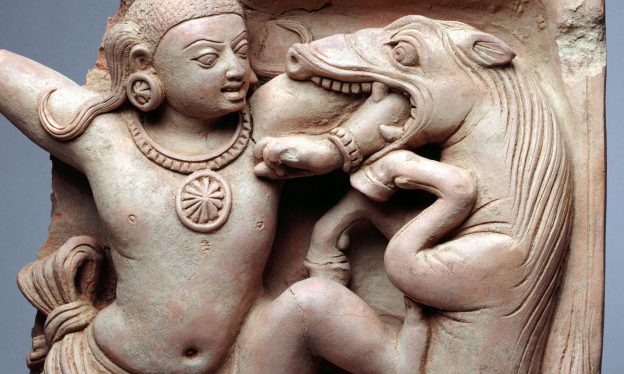

Beliefs made visible, Hindu art in South Asia

Hindu Temples

Varanasi: sacred city

Sacred texts in Hinduism

Among the founders of the world’s major religions, the Buddha was the only teacher who did not claim to be other than an ordinary human being. Other teachers were either God or were directly inspired by God. The Buddha was simply a human being who claimed no inspiration from any God or external power.

The Historical Buddha

Aniconic vs. Iconic Depictions of the Buddha in India

Four Buddhas at the AMNH

Bodh Gaya: center of the Buddhist world

Judaism stems from a collection of stories that describe the origins of the “children of Israel” and the laws that their deity commanded of them. The stories explain how the Israelites came to settle, construct a Temple for their one God, and eventually establish a monarchy—as divinely instructed—in the ancient Land of Israel.

Judaism, an introduction

Jewish History to the Middle Ages

Jewish History 1750-WWII

Jewish History in the post-war period

All content | tools for understanding religion in art.

Get familiar with the concepts that underlie the study of religion and art.

How to recognize a bodhisattva

How to recognize the Four Evangelists

How to recognize the Buddha

Bodhisattvas, an introduction

Bodh Gaya: The Site of the Buddha’s Enlightenment

Buddhist meditation and chant

Introduction to Buddhism

Hindu deities

The complex geometry of Islamic design

Stories of the modern pilgrimage

Islamic pilgrimages and sacred spaces

The lives of Christ and the Virgin in Byzantine art

Selected contributors.

Dr. Jennifer Freeman

Dr. Jessica Hammerman

Dr. Shaina Hammerman

Dr. Laurel Kendall

Dr. Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis

Dr. Jennifer N. McIntire

Dr. Cristin McKnight Sethi

Dr. Melody Rod-ari

Dr. Nancy Ross

Dr. Monique Scott

Dr. Karen Shelby

Kendra Weisbin

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

Brill | Nijhoff

Brill | Wageningen Academic

Brill Germany / Austria

Böhlau

Brill | Fink

Brill | mentis

Brill | Schöningh

Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht

V&R unipress

Open Access

Open Access for Authors

Open Access and Research Funding

Open Access for Librarians

Open Access for Academic Societies

Discover Brill’s Open Access Content

Organization

Stay updated

Corporate Social Responsiblity

Investor Relations

Policies, rights & permissions

Review a Brill Book

Author Portal

How to publish with Brill: Files & Guides

Fonts, Scripts and Unicode

Publication Ethics & COPE Compliance

Data Sharing Policy

Brill MyBook

Ordering from Brill

Author Newsletter

Piracy Reporting Form

Sales Managers and Sales Contacts

Ordering From Brill

Titles No Longer Published by Brill

Catalogs, Flyers and Price Lists

E-Book Collections Title Lists and MARC Records

How to Manage your Online Holdings

LibLynx Access Management

Discovery Services

KBART Files

MARC Records

Online User and Order Help

Rights and Permissions

Latest Key Figures

Latest Financial Press Releases and Reports

Annual General Meeting of Shareholders

Share Information

Specialty Products

Press and Reviews

Share link with colleague or librarian

Stay informed about this journal!

- Get New Issue Alerts

- Get Advance Article alerts

- Get Citation Alerts

Keeping the Faith

Religion, gender, and the arts in the twenty-first century.

In many cultures, women are the “keepers of the faith,” despite the fact that masculine pronouns are often used to identify deity or deities in most of the world’s major religions. In addition, many foundational leaders of these faiths were male—Abraham, Moses, Jesus, Muhammed, and Siddhartha Gautama (the Buddha). This double issue of Religion and the Arts seeks to explore the ways in which contemporary artists who identify as women or are non-binary or third gender engage with spirituality, both in the context of different faith traditions and as unaffiliated spiritual seekers. The essays include: Scholarly explorations of contemporary artists’ engagement with religion and/or spirituality in the context of cultural roots; faith, religion and/or spirituality as a source of inspiration in art making for women artists, inclusive of trans and gender non-conforming people; relationships between religious traditions and gender fluidity as explored by contemporary artists; consideration of how women and gender non-conforming artists around the world are grappling with religiosity in their cultures and personal artistic practices; and the role of contemporary art made by women and/or gender-fluid artists in encouraging dialogue around religious belief.

- 1 Introduction

In many cultures, women are the “keepers of the faith,” despite the fact that masculine pronouns are often used to identify deity or deities in a number of the world’s major religions. In addition, many foundational leaders of these faiths were male—Abraham, Moses, Jesus, Muhammed, and Siddhartha Gautama (the Buddha). Tony Walter and Grace Davie explored this phenomenon in the West in their essay, “The Religiosity of Women in the Modern West,” published in The British Journal of Sociology in 1998. More recent studies by the Pew Research Center on Religion and Public Life indicate that “globally, women are more devout than men by several standard measures of religious commitment,” despite the fact that men show higher engagement in formal religious practice in some cultures and religious groups (“The Gender Gap”). A 2014 survey that the organization conducted in the United States revealed that 60 % of women said religion was “very important” in their lives, as compared with 47 % of men (Pew Research Center “The Gender Gap”). The Research Center collected data about gender and religion across six faith traditions around the world (Christians, Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus, Jews, and the religiously unaffiliated) between 2008 and 2015 and has also made projections looking as far ahead as 2050. While they conclude that women, globally, are more devout than men, they also found that in some countries or within certain religious groups, men showed a higher level of religious commitment, and in some cases, gender differences were not obvious; for instance, Christian women show deeper religious commitment than Christian men, whereas Muslim women and men showed roughly equal levels of religious commitment, although men more frequently worshipped at a mosque (Pew Research Center “The Gender Gap”).

Psychological and sociological factors have often been pointed to as explanations for this gap. Historically, men were more involved in labor and the workforce, leaving less time for religious devotion, which some sociologists viewed as a factor; others saw socialization, and the emphasis on nurturing and domesticity in socializing females versus the focus on aggressiveness and competition for males, as determinants (Sullins 839). If one thinks of religious devotion as a way of seeking help, this may provide another explanation. In the U.S. , “middle-aged white men have the highest rates of suicide,” even while men and women have similar rates of depression; this is largely explained by male reluctance to seek help (Bruinius 20).

Some scholars, such as Rodney Stark, have argued that physiology plays a role in this “gender gap,” specifically arguing that males are more likely to be risk-takers and are, therefore, less likely to be strongly connected to religion (Stark). However, others, such as Donald Paul Sullins, have disputed this conclusion. While admitting that social scientists, for more than a century, have generally accepted that women are “universally” more religious than men, Sullins argues that the situation is far more complex, especially when examining different religious traditions (841). He also argues for looking at “affective” vs. “active” approaches to faith—personal devotion vs. engagement with organized religion; women tend to dominate the former, but not the latter, especially within Islam and Judaism (Sullins 838). Sullins also points out an interesting irony, “Both religious and gender scholars have been intrigued by the paradox that women continue to be more supportive than men of religious institutions that generally perpetuate patriarchy” (840).

One of the measures used by the Pew Research Center is religious affiliation. As of 2010, the Center found that globally, women were more likely to formally affiliate with a religion—83.4 % vs. 79.9 % of men (Pew Research Center “The Gender Gap”). At the same time, numerous other studies see a shift in some parts of the world, including the United States, away from traditional and mainstream religion in favor of exploration of more diverse faith practices and unaffiliated spirituality. Between 2007 and 2014, people in the United States indicating that they were unaffiliated went up from 16.1 % to 22.8 %; those identifying as “spiritual but not religious” remained steady at 0.3 % (Pew Research Center “Chapter 1: The Changing Religious Composition of the U.S. ”). Numerous surveys and studies now show “unaffiliated” as the most rapidly growing religious identity in America (Henao et al.).

A recent article in The New York Times titled “400 Years Ago, They Would Be Witches. Today, They Can Be Your Coach” quotes Erica Carrico as saying, “Women who were healers, who were connected to the moon cycle and nature, they were considered witches” (Worthen). Carrico is a “spiritual coach,” a role most often filled by a woman, a role that seems to be growing as people migrate away from mainstream religious organizations. As the Times article points out:

Spiritual coaches are a new chapter in the long history of female religious entrepreneurship in America—a tradition that runs from Boston in the 1630s, when Anne Hutchinson’s packed religious meetings outraged Puritan ministers, to today’s evangelical conference circuit, dominated by demure yet forceful female evangelists who are not ordained but whose books and podcasts constitute major media empires. By blending eclectic religious practices with the gospel of entrepreneurship, spiritual coaches pitch their clients (who, like the coaches, are mostly women) the things that religion has always promised. They offer a path to meaning in the midst of suffering and tools to recover a sense of agency in a world that flings us around by our heels. Worthen

Spiritual coaching is a subcategory of life coaching, which emerged in the 1970s. Life coaching, too, is dominated by women, with 75 percent of practitioners in North America being women. Carrico earned over one million dollars for her coaching in 2021 (Worthen).

Two decades ago, Darren Sherkat published a study documenting the religious commitments of gay men, lesbians, and bisexuals in the United States. Among his findings: homosexual men showed higher levels of religious participation than homosexual women and bisexuals (Sherkat 313). Looking at four areas of religious engagement—church attendance, frequency of prayer, apostate, and Bible as actual or inspired word of God—female heterosexuals showed the highest level of church attendance, though gay men were only slightly less likely to attend church than heterosexual men; heterosexual women had the highest frequency of prayer, with gay men only slightly less frequent and well above heterosexual men; lesbians and gay males, however, were most likely to be apostate; and heterosexuals of both genders were more likely to take the Bible as the word of God than homosexual or bisexual men and women (Sherkat 318).

The experience of transgender individuals with modern, established religion is likewise complex. For example, Catholics in the United States are finding that different dioceses have different policies in terms of ministering to the trans community. Over the past two years, six dioceses have, in some way, established restrictions for transgender people. For example, the Archdiocese of Milwaukee recently barred church staff from using the preferred pronouns reflecting the gender identity of trans congregants, and the Diocese of Marquette in Michigan moved to deny the sacraments to “unrepentant” trans, gay, and nonbinary Catholics (Crary 11A). On the other hand, a “small but growing number of parishes have formed LGBTQ support groups and welcome transgender people” (Crary 11A). Saint Patrick-Saint Anthony Church in Hartford, Connecticut, for example, hosts an annual Transgender Day of Remembrance, during which those who were killed as a result of anti-trans violence are commemorated (Crary 11A).

Because so many religious traditions anthropomorphize their deity, the “gendering” of God also plays a role in people’s experience of religion. Feminist author Barbara G. Walker has noted:

Our culture has been deeply penetrated by the notion that “man”—not woman—is created in the image of God. This notion persists, despite the likelihood that the creation goes in the other direction: that God is a human projection of the image of man. No known religion, past or present, ever succeeded in establishing a completely sexless deity. Worship was always accorded either a female or a male, occasionally a sexually united couple or an androgynous symbol of them; but deities had a sex just as people have a sex. The ancient Greeks and others whose culture accepted homosexuality naturally worshipped homosexual gods. (See Hermes .) Walker vii

The generally accepted notion of deity as male within the Judeo-Christian tradition has recently been explored in depth by Francesca Stavrakopoulou in her book God: An Anatomy . She argues that this corporeal image of God as anthropomorphic and male was a result of the circumstances and experiences of the cultures creating the foundational texts (Stavrakopoulou 2–3). She situates the origins of the Judeo-Christian Yahweh/God within a broader pantheon of deities in the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age Levant, headed by a male progenitor, generally the god El (Stavrakopoulou 19). Though Walker argues that Christianity actually has its roots in Middle Eastern goddess worship, she notes that as “a salvation cult,” it placed inordinate emphasis on the wickedness of females, privileging males (Walker viii). A contemporary example of this, noted by Stavrakopoulou, was the criticism leveled at Pope Francis when, soon after his elevation to the papacy in 2013, he washed, dried, and kissed the feet of two women as part of the traditional Easter Week reenactment of Christ washing the feet of his disciples (81). She goes on to point out that when Peter protests having Jesus wash his feet, his master explains that it is only through this process that his followers will be made ready to enter “the presence of the divine” (Stavrakopoulou 83). In other words, refusing to wash women’s feet also effectively barred them from entering the Kingdom of Heaven. This symbolic ritual, however, has been complicated by the long history of the eroticization and fetishization of feet in the Ancient World, with “feet” often being a euphemism for genitals (Stavrakopoulou 84–86). Indeed, the penis and semen were the ultimate expressions of power in many cultures. As Stavrakopoulou points out, “To a certain extent, the cultural privileging of the penis in these ancient societies is a stark reflection of the androcentric, elite perspectives of the scribes creating and compiling the texts on which we rely for information about the worlds in which they lived. This literature tended overwhelmingly to be produced by men, for men—and it was usually about men” (119). Further, the equating of circumcision with the covenant in Jewish tradition is preceded, according to Stavrakopoulou, by an Ugaritic myth that describes the circumcision of the Late Bronze Age god El (129). Islam, the world’s fastest-growing religion, poses similar challenges to those who are not heteronormative (Pew Research Center, “The Future of World Religions”).

This masculine construct is belied by many other faith traditions, which present gender-fluid and feminine deities. This is quite common in a wide range of Indigenous spiritual traditions. Even within Judaism, and particularly the Kabbalah, there is a feminine manifestation of God, expressed as Shekinah, which engages and unites with the masculine expression of deity (Stavrakopoulou 88, Baring, “Shekinah”). More recently, in nineteenth-century New England, Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of Christian Science, identified God as Father and Mother (256 and 530). She also argued against an anthropomorphic God, defining deity as spiritual qualities (Eddy 587). The World Mission Society Church of God also argues for a gender-inclusive God (“God the Mother—Female Image of God”). These examples, however, remain outliers within Christianity.

Even Hinduism, with its rich tradition of female deities and early connections to Tantrism, has strictly defined gender roles within its religious practice (Walker 973). Nevertheless, it presents powerful females as objects of worship, having its own “trinity,” embodied by Kali, “the Hindu Triple Goddess of creation, preservation, and destruction” (Walker 488). Durga, “the Queen-Mother” is another very powerful Hindu deity, who fights ferociously as a mother defending her children (Walker 257). Durga, a manifestation of the mother goddess Devi, is among the most revered deities in the Hindu pantheon. Similarly powerful female imagery is at the core of Tantric Buddhism, which venerates Shakti (Wayman 23). The Shaktisangama Tantra states:

Woman is the creator of the universe, the universe is her form; woman is the foundation of the world, she is the true form of the body. In woman is the form of all things, of all that lives and moves in the world. There is no jewel rarer than woman, no condition superior to that of a woman. Bose 115

Shakti, Walker points out, can be translated as “Cosmic Energy” (929).

Walker noted in the late twentieth century that increasing numbers of women were being drawn away from the three major Western religions, which emphasize a patriarchal tradition, and towards exploring earlier traditions of goddess worship, which goes all the way back to the Vedas . She writes that, “Through making God in his own image, man has almost forgotten that woman once made the Goddess in hers” (Walker xi). She argues, for example, that war is a patriarchal construct that was largely absent in matriarchal societies (Walker 1058). “In the Tantric morality which probably was planned by women, at least in part, war is entirely unacceptable” (Walker 1063).

- 2 Art as an Expression of Faith and Spirituality

Although scholars have been engaged for decades in research and debate about gender difference in religious practice and the reasons behind it, less attention has been paid to its influence on the arts as expressions of and commentary on faith and spirituality, particularly in contemporary art. Those essays that have appeared hint at the complexity of the topic. Susan Platt’s 2003 article, “Public Politics and Domestic Rituals: Contemporary Art by Women in Turkey, 1980–2000,” explores the work of Istanbul artist Suzy Hug-Levy, whose dress-like sculptures are her personal response to the rise of Islamic conservatism in her country and its impact on women (19). Platt notes that the artist’s “shroud-like forms signify the isolation of women by tradition and taboo” (19). Interestingly, Platt points out that contemporary women artists in Turkey are heir to two distinct constructs of womanhood, which are in tension with one another. One is the goddess tradition of prehistoric Anatolia, which served as a model during the period of the early Republic; the other is the emergence of political Islamism over the past 40 years. Hug-Levy, herself of Jewish background, explores this tension in her art (Platt 23). The goddess tradition has been explored by another artist cited by Platt, Tomur Atagök, who developed a series of monumental paintings on steel in the 1990s dedicated to the Anatolian mother goddess. Platt points out that “Atagök’s impulse to turn to the goddess tradition was inspired both by the Republican celebration of the pre-Islamic female and the encouragement of American feminist artists, some of whom also celebrate the goddess as a powerful model” (24).

Makda Teklemichael has explored the intersection of contemporary art by women artists with the Ethiopian Orthodox Church ( EOC ), which has been a major patron of the arts since the 4th century C.E. While over the centuries there have been some important women patrons of religious art in the country, there have been few women artists involved in its production, largely because of limits placed on the education and training of girls and women. Indeed, Teklemichael found it difficult to locate women artists who work in the EOC tradition, though several were identified. Woyzero Lemlem Gebremeskal is from a small village in Tigrai; she took to art as a child and later went on foot to a neighboring town to purchase supplies and gain basic instruction from a local artist (Teklemichael 40). A largely self-taught artist in a peasant village, Woyzero Lemlem largely bases her art on examples she has seen when visiting the town of Aksum, where she has been able to see the work of other artists; indeed, the churches in her own village are decorated with paintings brought from Aksum. Emahoy Wolate-Yohannes Sebehatu became a nun in order to focus her life on religious painting. She learned the techniques of traditional painting from a priest while living and working in a church on Lake Tana. Yordanos Berhanemeskal is the daughter of a traditional EOC painter. From a young age, she joined her father and brothers in the family workshop and imitated their techniques (Teklemichael 41).

In many patriarchal religious traditions, women are seen as “unclean” during their monthly menstrual cycles. With the rise of feminism in the later twentieth century, this aspect of being a woman has been embraced by a number of contemporary artists, a theme explored by Barbara Kutis in “The Contemporary Art of Menstruation: Embracing Taboos, Breaking Boundaries, and Making Art.” She notes that Simone de Beauvoir was among the first to articulate how patriarchal views of menstruation were used to oppress women in her groundbreaking 1949 book, The Second Sex (Kutis 110). Kutis also points to Lisa Saltzman’s research on the ways in which mid-twentieth century painter Helen Frankenthaler’s soak-staining technique was equated with female menstruation and passivity, while Morris Louis and other male artists who took up the approach were written about using decisive masculine terminology more closely aligning the staining process with male orgasm (Saltzman 377 and Kutis 112). With the rise of second-wave feminism in the 1970s, artists like Judy Chicago and Carolee Schneemann began to explicitly deal with women’s monthly cycles in their art (Kutis 113–114). Kutis then goes on to discuss the work of several fourth-wave feminist artists, among them Sarah Maple; she, too, has dealt with menstruation (fig. 1), but in addition, her “humorous works … deal with taboos of Islam at the intersection of Western culture” (118). Her work grows out of her personal struggles living as a Muslim woman in a largely Christian society (fig. 2). In a 2014 interview, she explained:

Many people interpreted my work as me commenting on oppressed Muslim women being forced into wearing the hijab or Burka. I wasn’t saying this at all. I wanted to challenge the perception of the Muslim woman as the victim, or even in general. At the time there was a lot of negativity about Muslims in the media. In this work I was looking at how in the “west” there is an obsession with physical appearance and with women being sexually attractive in a very limited and narrow way. I was looking at how this may be seen as a form of oppression and that there may be a freedom in covering up. It was also at a time on reflecting on my own religious beliefs and “faith”. In my opinion, the aim of religion is ultimately trying to make us better people and if we were better people then we may live in a more equal society. “Interview with God is a Feminist Artist, Sarah Maple”

Menstruate with Pride . Sarah Maple, 2010–2011. Oil on canvas, 215 × 275 cm

Citation: Religion and the Arts 27, 1-2 (2023) ; 10.1163/15685292-02701001

- Download Figure

- Download figure as PowerPoint slide

God Is a Feminist . Sarah Maple, 2009. Oil, acrylic, and gloss on canvas, 190 × 150 cm

Indigenous photographer Cara Romero is a member of the Chemehuevi tribe. In her culture, females are the source of creation. She has chosen to photograph her friends and relatives “from a Native American female perspective” (“Cara Romero Photography”). She says of her work, “Sometimes I portray old stories, such as creation stories or animal stories, in a contemporary context to show that each grows and evolves with ensuing generations” (“Cara Romero Photography”). 1 In this way, she sees herself as a keeper of the faith.

- 3 Essays in this Issue

This double issue of Religion and the Arts seeks to explore the ways in which contemporary artists who identify as women, are nonbinary, or third-gender, engage with spirituality, both in the context of different faith traditions and as unaffiliated spiritual seekers. The essays include scholarly explorations of contemporary artists’ engagement with religion and/or spirituality in the context of cultural roots; faith, religion and/or spirituality as a source of inspiration in art making; relationships between religious traditions and gender fluidity, historically and as explored by contemporary artists; consideration of how women and gender non-conforming artists around the world are grappling with religiosity in their cultures and personal artistic practices; and the role of contemporary art made by women and/or transgender or nonbinary artists in encouraging dialogue around religious belief. Contributors are both scholars and artists from around the world, providing an international perspective.

The first essay, by Karen Zukowski, focuses on Louise Nevelson’s designs for the Erol Beker Chapel of the Good Shepherd, commissioned in 1977 by Reverend Ralph Peterson and St Peter’s Lutheran Church in New York City. Currently undergoing a much-needed restoration, the space was designed as a place of peace created through abstract art. Christopher Rothko has referred to it as a “womb for the soul” (“Renewing a Masterpiece”). Zukowski examines the history of the project, including the roles of artist and patron, how it functions as a sacred space in the twenty-first century, and the factors being considered as the chapel undergoes restoration.

Nevelson’s space was among the many sources of inspiration for Korean-born artist Sook Jin Jo, who is also known for her sculptural assemblages. Using discarded materials, Jo explores the ideas of rebirth and time informed by Asian religious and philosophical traditions such as Zen Buddhism and Taoism; yet her own New York City Meditation Space (2000) grew out of earlier projects creating sacred and meditative spaces that developed out of the artist’s memories of finding peace of mind in Nevelson’s chapel. Soojung Hyun explores Jo’s concept of spirituality and how it has informed her work from the 1980s to the present.

Elizabeth Hawley and Sooran Choi both explore aspects of the influence of indigenous religious traditions on contemporary artists. Hawley’s focus is on two Diné artists, visual artist Bean (Jolene) Nenibah Yazzie and their partner, poet and tribal health advocate Hannabah Blue (also Diné), who decided to get married. Despite a long, pre-colonial tradition of more freely defined gender roles that included recognition of non-binary identities, the couple were unable to find a Diné healer willing to bless their union. In an interview, the author explores with the two the challenges and successes they have faced as they seek to “decolonize” Diné worldviews. Choi examines the influence of Korean shamanism and other indigenous practices in the work of late twentieth and twenty-first century artists who sought alternatives to the rigid gender roles proscribed by the mainstream nationalist neo-Confucian and imperial Christian conservatism that dominated Korean culture during the post-World War II period to the 1980s, and which especially oppressed women and gender non-conforming people. The essay focuses on the intersection of Korean feminism, queerism, and shamanistic practices/spirituality as an alternative to an increasingly materialistic and authoritarian culture. Singapore-based scholar Louis Ho sees a similar anti-materialist undercurrent in the work of artist Zarina Muhammad, who was born Malay-Muslim but identifies as a queer animist. Her focus on magic, ritual, and the immaterial provides a powerful alternative to Singapore’s emphasis on modernity, technology, and its “Smart Nation” initiative.

Zainab Abdali explores the role of faith in the notion of “belonging” among diasporic Muslim women. In particular, Abdali unpacks the interplay of religion, nationalism, and Muslim womanhood in the work of Pakistani-American artist Shahzia Sikander and examines how the politics and rhetoric of the War on Terror have shaped her artistic practice.

Shriya Srindharan investigates the role of women in contemporary Hindu temple construction and decoration in South India, with a specific focus on the kolam s drawn by women on the floors of temples in the state of Tamil Nadu, and what this ephemeral art form conveys about the connections between women’s status in a Hindu temple context and the nature of this particular artistic activity.

Contemporary performance art and its intersection with faith and religion is the focus of co-editor Kyunghee Pyun’s essay, which provides a close reading of American artist Linda Mary Montano’s Anorexia Nervosa , exploring the artist’s spiritual journey with a particular focus on her evolution away from and then back to Catholicism. Montano, a former Maryknoll nun, is also contextualized within the history of art making by Catholic nuns and within the broader sphere of expressions of Catholicism in contemporary art by women and nonbinary individuals.

In addition to these scholarly explorations, two artists share more intimate looks at how their individual spiritual journeys, including responses to the coronavirus pandemic, have informed their artistic practices. Japanese-born Yasuyo Tanaka emigrated to New York in 1994; exploring her Japanese roots and the influences of Shinto and Buddhist faith traditions within the context of her new American home has led Tanaka to focus on issues around world peace as an ongoing theme. Similarly, issues surrounding climate change and our need to treasure and revitalize our planet are close to the artist’s heart. During the COVID pandemic, Tanaka, who sees art as a tool for education and healing, led a workshop in which participants created medicine balls, brought together by their desire for health, long life, and peace. Finally, artist/writer/philosopher Andy Izenson explores the Jewish anarchist mystic tradition with its links to the Dada movement, with particular emphasis on the cut-up, and then examines its relevance to their own rejection of a gender binary.

Romero’s work was included in the Museum of Modern Art’s recent exhibition “Our Selves: Photographs by Women Artists from Helen Kornblum,” April 16 to October 10, 2022. An audio of the artist speaking of her background was presented among the resources: https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/685 , accessed August 4, 2022.

- Works Cited

Baring , Anne . “ The Shekinah of Kabbalah .” https://www.annebaring.com/the-shekinah-of-kabbalah/ . Accessed 28 February, 2022.

- Search Google Scholar

- Export Citation

Bose , Mandakranta . Faces of the Feminine in Ancient, Medieval, and Modern India . New York : Oxford University Press , 2000 .

Bruinius , Harry . “ Why these men find the phrase ‘toxic masculinity’ to be toxic .” The Christian Science Monitor , Vol. 114 , issue 16 (March 7, 2022 ), 18 – 21 .

“ Cara Romero Photography .” https://www.cararomerophotography.com/ . Accessed April 14, 2022 .

Crary , David . “ Transgender Catholics face pushback .” The Journal News , February 28, 2022 , 11A.

Eddy , Mary Baker . Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures . Boston : The Christian Science Publishing Society , 1875 .

“ God the Mother—Female Image of God .” World Mission Society Church of God . https://wmscog.com/god-the-mother/female-image-of-god/ . Accessed May 26, 2022.

Henao , Luis Andres , Kwasi Gyamfi Asiedu and David Crary . “ What’s Your Religion? ‘None’ is fastest-growing group in US surveys asking about religious identity .” December 14 , 2021 . https://www.ksl.com/article/50311623/whats-your-religion-none-is-fastest-growing-group-in-us-surveys-asking-about-religious-identity . Accessed 28 February, 2022.

“ Interview with God is a Feminist Artist, Sarah Maple .” Aesthetica. Posted February 20 , 2014 . https://aestheticamagazine.com/interview-god-feminist-artist-sarah-maple/ , Accessed June 30, 2022.

Kutis , Barbara . “ The Contemporary Art of Menstruation: Embracing Taboos, Breaking Boundaries, and Making Art .” Menstruation Now: What Does Blood Perform? Ed. Kaite Berkeley . Bradford ON : Demeter Press , 2019 .109–133.

Pew Research Center . “ Chapter 1: The Changing Religious Composition of the U.S .” America’s Changing Religious Landscape , May 12, 2015 , https://www.pewforum.org/2015/05/12/chapter-1-the-changing-religious-composition-of-the-u-s/ . Accessed 9 February, 2022.

Pew Research Center . The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010–2050 . April 2, 2015. https://www.pewforum.org/2015/04/02/religious-projections-2010-2050/ . Accessed 28 February, 2022.

Pew Research Center . The Gender Gap in Religion Around the World . March 22, 2016 , https://www.pewforum.org/2016/03/22/the-gender-gap-in-religion-around-the-world/ . Accessed 9 February, 2022.

Platt , Susan N. “ Public Politics and Domestic Rituals: Contemporary Art by Women in Turkey, 1980–2000 ,” Frontiers: A Journal of Women’s Studies 21. 1 ( 2003 ): 19 – 37 .

“ Renewing a Masterpiece .” Nevelson Chapel , https://www.nevelsonchapel.org/ . Accessed 9 February, 2022.