- Teaching Tips

The Ultimate Guide to Grading Student Work

Strategies, best practices and practical examples to make your grading process more efficient, effective and meaningful

Top Hat Staff

This ultimate guide to grading student work offers strategies, tips and examples to help you make the grading process more efficient and effective for you and your students. The right approach can save time for other teaching tasks, like lecture preparation and student mentoring.

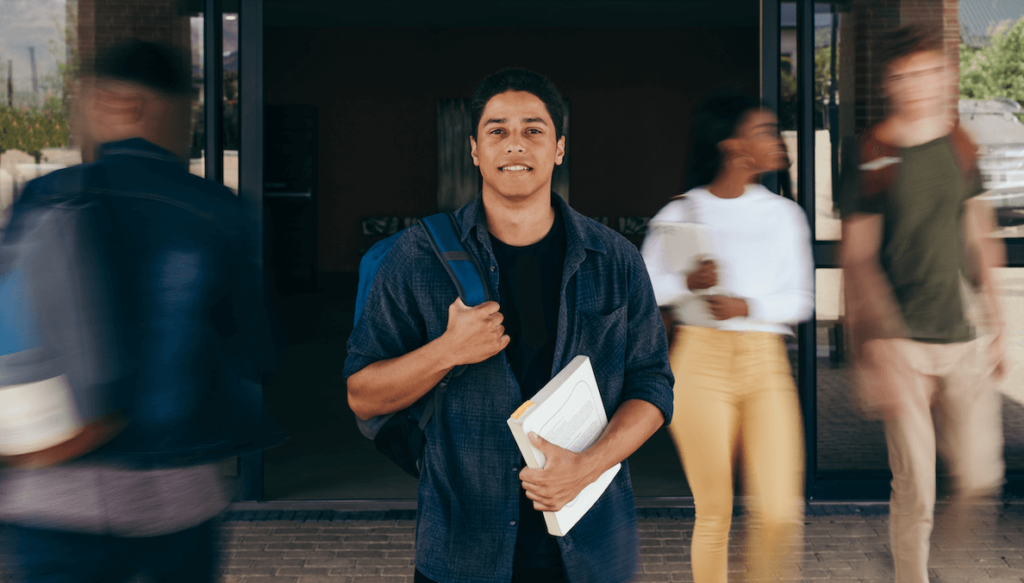

Grading is one of the most painstaking responsibilities of postsecondary teaching. It’s also one of the most crucial elements of the educational process. Even with an efficient system, grading requires a great deal of time—and even the best-laid grading systems are not entirely immune to student complaints and appeals. This guide explores some of the common challenges in grading student work along with proven grading techniques and helpful tips to communicate expectations and set you and your students up for success, especially those who are fresh out of high school and adjusting to new expectations in college or university.

What is grading?

Grading is only one of several indicators of a student’s comprehension and mastery, but understanding what grading entails is essential to succeeding as an educator. It allows instructors to provide standardized measures to evaluate varying levels of academic performance while providing students valuable feedback to help them gauge their own understanding of course material and skill development. Done well, effective grading techniques show learners where they performed well and in what areas they need improvement. Grading student work also gives instructors insights into how they can improve the student learning experience.

Grading challenges: Clarity, consistency and fairness

No matter how experienced the instructor is, grading student work can be tricky. No such grade exists that perfectly reflects a student’s overall comprehension or learning. In other words, some grades end up being inaccurate representations of actual comprehension and mastery. This is often the case when instructors use an inappropriate grading scale, such as a pass/fail structure for an exam, when a 100-point system gives a more accurate or nuanced picture.

Grading students’ work fairly but consistently presents other challenges. For example, grades for creative projects or essays might suffer from instructor bias, even with a consistent rubric in place. Instructors can employ every strategy they know to ensure fairness, accessibility, accuracy and consistency, and even so, some students will still complain about their grades. Handling grade point appeals can pull instructors away from other tasks that need their attention.

Many of these issues can be avoided by breaking things down into logical steps. First, get clear on the learning outcomes you seek to achieve, then ensure the coursework students will engage in is well suited to evaluating those outcomes and last, identify the criteria you will use to assess student performance.

What are some grading strategies for educators?

There are a number of grading techniques that can alleviate many problems associated with grading, including the perception of inconsistent, unfair or arbitrary practices. Grading can use up a large portion of educators’ time. However, the results may not improve even if the time you spend on it does. Grading, particularly in large class sizes, can leave instructors feeling burnt out. Those who are new to higher education can fall into a grading trap, where far too much of their allocated teaching time is spent on grading. As well, after the graded assignments have been handed back, there may be a rush of students wanting either to contest the grade, or understand why they got a particular grade, which takes up even more of the instructor’s time. With some dedicated preparation time, careful planning and thoughtful strategies, grading student work can be smooth and efficient. It can also provide effective learning opportunities for the students and good information for the instructor about the student learning (or lack of) taking place in the course. These grading strategies can help instructors improve their accuracy in capturing student performance .

Establishing clear grading criteria

Setting grading criteria helps reduce the time instructors spend on actual grading later on. Such standards add consistency and fairness to the grading process, making it easier for students to understand how grading works. Students also have a clearer understanding of what they need to do to reach certain grade levels.

Establishing clear grading criteria also helps instructors communicate their performance expectations to students. Furthermore, clear grading strategies give educators a clearer picture of content to focus on and how to assess subject mastery. This can help avoid so-called ‘busywork’ by ensuring each activity aligns clearly to the desired learning outcome.

Step 1: Determine the learning outcomes and the outputs to measure performance. Does assessing comprehension require quizzes and/or exams, or will written papers better capture what the instructor wants to see from students’ performance? Perhaps lab reports or presentations are an ideal way of capturing specific learning objectives, such as behavioral mastery.

Step 2: Establish criteria to determine how you will evaluate assigned work. Is it precision in performing steps, accuracy in information recall, or thoroughness in expression? To what extent will creativity factor in the assessment?

Step 3: Determine the grade weight or value for each assignment. These weights represent the relative importance of each assignment toward the final grade and a student’s GPA. For example, how much will the final exam count relative to a research paper or essay? Once the weights are in place, it’s essential to stratify grades that distinguish performance levels. For example:

- A grade = excellent

- B grade = very good

- C grade = adequate

- D grade = poor but passing

- F grade = unacceptable

Making grading efficient

Grading efficiency depends a great deal on devoting appropriate amounts of time to certain grading tasks. For instance, some assignments deserve less attention than others. That’s why some outcomes, like attendance or participation work, can help save time by getting a simple pass/fail grade or acknowledgment of completion using a check/check-plus/check-minus scale.

However, other assignments like tests or papers need to show more in-depth comprehension of the course material. These items need more intricate scoring schemes and require more time to evaluate, especially if student responses warrant feedback.

When appropriate, multiple-choice questions can provide a quick grading technique. They also provide the added benefit of grading consistency among all students completing the questions. However, multiple-choice questions are more difficult to write than most people realize. These questions are most useful when information recall and conceptual understanding are the primary learning outcomes.

Instructors can maximize their time for more critical educational tasks by creating scheduled grading strategies and sticking to it. A spreadsheet is also essential for calculating many students’ grades quickly and exporting data to other platforms.

Making grading more meaningful in higher education

Grading student work is more than just routine, despite what some students believe. The better students understand what instructors expect them to take away from the course, the more meaningful the grading structure will be. Meaningful grading strategies reflect effective assignments, which have distinct goals and evaluation criteria. It also helps avoid letting the grading process take priority over teaching and mentoring.

Leaving thoughtful and thorough comments does more than rationalize a grade. Providing feedback is another form of teaching and helps students better understand the nuances behind the grade. Suppose a student earns a ‘C’ on a paper. If the introduction was outstanding, but the body needed improvement, comments explaining this distinction will give a clearer picture of what the ‘C’ grade represents as opposed to ‘A-level’ work.

Instructors should limit comments to elements of their work that students can actually improve or build upon. Above all, comments should pertain to the original goal of the assignment. Excessive comments that knit-pick a student’s work are often discouraging and overwhelming, leaving the student less able or willing to improve their effort on future projects. Instead, instructors should provide comments that point to patterns of strengths and areas needing improvement. It’s also helpful to leave a summary comment at the end of the assignment or paper.

Maintaining a complaint-free grading system

In many instances, an appropriate response to a grade complaint might simply be, “It’s in the syllabus.” Nevertheless, one of the best strategies to curtail grade complaints is to limit or prohibit discussions of grades during class time. Inform students that they can discuss grades outside of class or during office hours.

Instructors can do many things before the semester or term begins to reduce grade complaints. This includes detailed explanations in the grading system’s syllabus, the criteria for earning a particular letter grade, policies on late work, and other standards that inform grading. It also doesn’t hurt to remind students of each assignment’s specific grading criteria before it comes due. Instructors should avoid changing their grading policies; doing so will likely lead to grade complaints.

Assigning student grades

Since not all assignments may count equally toward a final course grade, instructors should figure out which grading scales are appropriate for each assignment. They should also consider that various assignments assess student work differently; therefore, their grading structure should reflect those differences. For example, some exams might warrant a 100-point scale rather than a pass/fail grade. Requirements like attendance or class participation might be used to reward effort; therefore, merely completing that day’s requirement is sufficient.

Grading essays and open-ended writing

Some writing projects might seem like they require more subjective grading standards than multiple-choice tests. However, instructors can implement objective standards to maintain consistency while acknowledging students’ individual approaches to the project.

Instructors should create a rubric or chart against which they evaluate each assignment. A rubric contains specific grading criteria and the point value for each. For example, out of 100 points, a rubric specifies that a maximum of 10 points are given to the introduction. Furthermore, an instructor can include even more detailed elements that an introduction should include, such as a thesis statement, attention-getter, and preview of the paper’s main points.

Grading creative work

While exams, research papers, and math problems tend to have more finite grading criteria, creative works like short films, poetry, or sculptures can seem more difficult to grade. Instructors might apply technical evaluations that adhere to disciplinary standards. However, there is the challenge of grading how students apply their subject talent and judgment to a finished product.

For creative projects that are more visual, instructors might ask students to submit a written statement along with their assignment. This statement can provide a reflection or analysis of the finished product, or describe the theory or concept the student used. This supplement can add insight that informs the grade.

Grading for multi-section courses

Professors or course coordinators who oversee several sections of a course have the added responsibility of managing other instructors or graduate student teaching assistants (TAs) in addition to their own grading. Course directors need to communicate regularly and consistently with all teaching staff about the grading standards and criteria to ensure they are applied consistently across all sections.

If possible, the course director should address students from all sections in one gathering to explain the criteria, expectations, assignments, and other policies. TAs should continue to communicate grading-related information to the students in their classes. They also should maintain contact with each other and the course director to address inconsistencies, stay on top of any changes and bring attention to problems.

To maintain consistency and objectivity across all sections, the course director might consider assigning TAs to grade other sections besides their own. Another strategy that can save time and maintain consistency is to have each TA grade only one exam portion. It’s also vital to compare average grades and test scores across sections to see if certain groups of students are falling behind or if some classes need changes in their teaching strategies.

Types of grading

- Absolute grading : A grading system where instructors explain performance standards before the assignment is completed. grades are given based on predetermined cutoff levels. Here, each point value is assigned a letter grade. Most schools adopt this system, where it’s possible for all students to receive an A.

- Relative grading : An assessment system where higher education instructors determine student grades by comparing them against those of their peers.

- Weighted grades : A method ussed in higher education to determine how different assessments should count towards the final grade. An instructor may choose to make the results of an exam worth 50 percent of a student’s total class grade, while assignments account for 25 percent and participation marks are worth another 25 percent.

- Grading on a curve : This system adjusts student grades to ensure that a test or assignment has the proper distribution throughout the class (for example, only 20% of students receive As, 30% receive Bs, and so on), as well as a desired total average (for example, a C grade average for a given test). We’ve covered this type of grading in more detail in the blog post The Ultimate Guide to Grading on A Curve .

Ungrading is an education model that prioritizes giving feedback and encouraging learning through self-reflection rather than a letter grade. Some instructors argue that grades cannot objectively assess a student’s work. Even when calculated down to the hundredth of a percentage point, a “B+” on an English paper doesn’t paint a complete picture about what a student can do, what they understand or where they need help. Alfie Kohn, lecturer on human behavior, education, and parenting, says that the basis for grades is often subjective and uninformative. Even the final grade on a STEM assignment is more of a reflection of how the assignment was written, rather than the student’s mastery of the subject matter. So what are educators who have adopted ungrading actually doing? Here are some practices and strategies that decentralize the role of assessments in the higher ed classroom.

- Frequent feedback: Rather than a final paper or exam, encourage students to write letters to reflect on their progress and learning throughout the term. Students are encouraged to reflect on and learn from both their successes and their failures, both individually and with their peers. In this way, conversations and commentary become the primary form of feedback, rather than a letter grade.

- Opportunities for self-reflection: Open-ended questions help students to think critically about their learning experiences. Which course concepts have you mastered? What have you learned that you are most excited about? Simple questions like these help guide students towards a more insightful understanding of themselves and their progress in the course.

- Increasing transparency: Consider informal drop-in sessions or office hours to answer student questions about navigating a new style of teaching and learning. The ungrading process has to begin from a place of transparency and openness in order to build trust. Listening to and responding to student concerns is vital to getting students on board. But just as important is the quality of feedback provided, ensuring both instructors and students remain on the same page.

Grading on a curve

Instructors will grade on a curve to allow for a specific distribution of scores, often referred to as “normal distribution.” To ensure there is a specific percentage of students receiving As, Bs, Cs and so forth, the instructor can manually adjust grades.

When displayed visually, the distribution of grades ideally forms the shape of a bell. A small number of students will do poorly, another small group will excel and most will fall somewhere in the middle. Students whose grades settle in the middle will receive a C-average. Students with the highest and the lowest grades fall on either side.

Some instructors will only grade assignments and tests on a curve if it is clear that the entire class struggled with the exam. Others use the bell curve to grade for the duration of the term, combining every score and putting the whole class (or all of their classes, if they have more than one) on a curve once the raw scores are tallied.

How to make your grading techniques easier

Grading is a time-consuming exercise for most educators. Here are some tips to help you become more efficient and to lighten your load.

- Schedule time for grading: Pay attention to your rhythms and create a grading schedule that works for you. Break the work down into chunks and eliminate distractions so you can stay focused.

- Don’t assign ‘busy work’: Each student assignment should map clearly to an important learning outcome. Planning up front ensures each assignment is meaningful and will avoid adding too much to your plate.

- Use rubrics to your advantage: Clear grading criteria for student assignments will help reduce the cognitive load and second guessing that can happen when these tools aren’t in place. Having clear standards for different levels of performance will also help ensure fairness.

- Prioritize feedback: It’s not always necessary to provide feedback on every assignment. Also consider bucketing feedback into what was done well, areas for improvement and ways to improve. Clear, pointed feedback is less time-consuming to provide and often more helpful to students.

- Reward yourself: Grading is taxing work. Be realistic about how much you can do and in what time period. Stick to your plan and make sure to reward yourself with breaks, a walk outside or anything else that will help you refresh.

How Top Hat streamlines grading

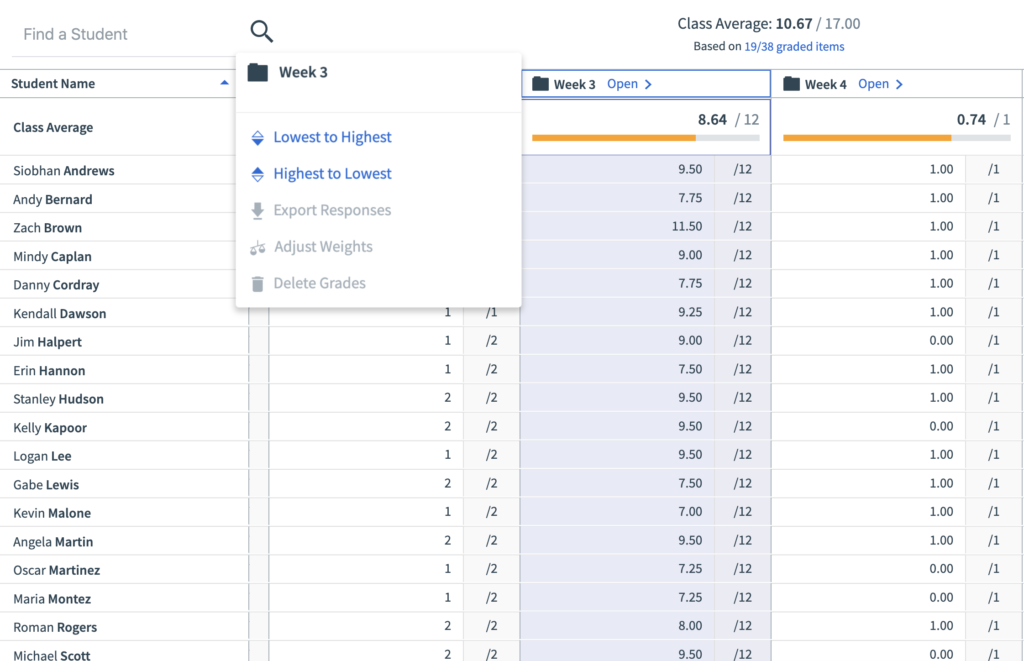

There are many tools available to college educators to make grading student work more consistent and efficient. Top Hat’s all-in-one teaching platform allows you to automate a number of grading processes, including tests and quizzes using a variety of different question types. Attendance, participation, assignments and tests are all automatically captured in the Top Hat Gradebook , a sophisticated data management tool that maintains multiple student records.

In the Top Hat Gradebook, you can access individual and aggregate grades at a glance while taking advantage of many different reporting options. You can also sync grades and other reporting directly to your learning management system (LMS).

Grading is one of the most essential components of the teaching and learning experience. It requires a great deal of strategy and thought to be executed well. While it certainly isn’t without its fair share of challenges, clear expectations and transparent practice ensure that students feel included as part of the process and can benefit from the feedback they receive. This way, they are able to track their own progress towards learning goals and course objectives.

Click here to learn more about Gradebook, Top Hat’s all-in-one solution designed to help you monitor student progress with immediate, real-time feedback.

Recommended Readings

25 Effective Instructional Strategies For Educators

The Complete Guide to Effective Online Teaching

Subscribe to the top hat blog.

Join more than 10,000 educators. Get articles with higher ed trends, teaching tips and expert advice delivered straight to your inbox.

Center for Teaching

Grading student work.

Print Version

What Purposes Do Grades Serve?

Developing grading criteria, making grading more efficient, providing meaningful feedback to students.

- Maintaining Grading Consistency in Multi-Sectioned Courses

Minimizing Student Complaints about Grading

Barbara Walvoord and Virginia Anderson identify the multiple roles that grades serve:

- as an evaluation of student work;

- as a means of communicating to students, parents, graduate schools, professional schools, and future employers about a student’s performance in college and potential for further success;

- as a source of motivation to students for continued learning and improvement;

- as a means of organizing a lesson, a unit, or a semester in that grades mark transitions in a course and bring closure to it.

Additionally, grading provides students with feedback on their own learning , clarifying for them what they understand, what they don’t understand, and where they can improve. Grading also provides feedback to instructors on their students’ learning , information that can inform future teaching decisions.

Why is grading often a challenge? Because grades are used as evaluations of student work, it’s important that grades accurately reflect the quality of student work and that student work is graded fairly. Grading with accuracy and fairness can take a lot of time, which is often in short supply for college instructors. Students who aren’t satisfied with their grades can sometimes protest their grades in ways that cause headaches for instructors. Also, some instructors find that their students’ focus or even their own focus on assigning numbers to student work gets in the way of promoting actual learning.

Given all that grades do and represent, it’s no surprise that they are a source of anxiety for students and that grading is often a stressful process for instructors.

Incorporating the strategies below will not eliminate the stress of grading for instructors, but it will decrease that stress and make the process of grading seem less arbitrary — to instructors and students alike.

Source: Walvoord, B. & V. Anderson (1998). Effective Grading: A Tool for Learning and Assessment . San Francisco : Jossey-Bass.

- Consider the different kinds of work you’ll ask students to do for your course. This work might include: quizzes, examinations, lab reports, essays, class participation, and oral presentations.

- For the work that’s most significant to you and/or will carry the most weight, identify what’s most important to you. Is it clarity? Creativity? Rigor? Thoroughness? Precision? Demonstration of knowledge? Critical inquiry?

- Transform the characteristics you’ve identified into grading criteria for the work most significant to you, distinguishing excellent work (A-level) from very good (B-level), fair to good (C-level), poor (D-level), and unacceptable work.

Developing criteria may seem like a lot of work, but having clear criteria can

- save time in the grading process

- make that process more consistent and fair

- communicate your expectations to students

- help you to decide what and how to teach

- help students understand how their work is graded

Sample criteria are available via the following link.

- Analytic Rubrics from the CFT’s September 2010 Virtual Brownbag

- Create assignments that have clear goals and criteria for assessment. The better students understand what you’re asking them to do the more likely they’ll do it!

- letter grades with pluses and minuses (for papers, essays, essay exams, etc.)

- 100-point numerical scale (for exams, certain types of projects, etc.)

- check +, check, check- (for quizzes, homework, response papers, quick reports or presentations, etc.)

- pass-fail or credit-no-credit (for preparatory work)

- Limit your comments or notations to those your students can use for further learning or improvement.

- Spend more time on guiding students in the process of doing work than on grading it.

- For each significant assignment, establish a grading schedule and stick to it.

Light Grading – Bear in mind that not every piece of student work may need your full attention. Sometimes it’s sufficient to grade student work on a simplified scale (minus / check / check-plus or even zero points / one point) to motivate them to engage in the work you want them to do. In particular, if you have students do some small assignment before class, you might not need to give them much feedback on that assignment if you’re going to discuss it in class.

Multiple-Choice Questions – These are easy to grade but can be challenging to write. Look for common student misconceptions and misunderstandings you can use to construct answer choices for your multiple-choice questions, perhaps by looking for patterns in student responses to past open-ended questions. And while multiple-choice questions are great for assessing recall of factual information, they can also work well to assess conceptual understanding and applications.

Test Corrections – Giving students points back for test corrections motivates them to learn from their mistakes, which can be critical in a course in which the material on one test is important for understanding material later in the term. Moreover, test corrections can actually save time grading, since grading the test the first time requires less feedback to students and grading the corrections often goes quickly because the student responses are mostly correct.

Spreadsheets – Many instructors use spreadsheets (e.g. Excel) to keep track of student grades. A spreadsheet program can automate most or all of the calculations you might need to perform to compute student grades. A grading spreadsheet can also reveal informative patterns in student grades. To learn a few tips and tricks for using Excel as a gradebook take a look at this sample Excel gradebook .

- Use your comments to teach rather than to justify your grade, focusing on what you’d most like students to address in future work.

- Link your comments and feedback to the goals for an assignment.

- Comment primarily on patterns — representative strengths and weaknesses.

- Avoid over-commenting or “picking apart” students’ work.

- In your final comments, ask questions that will guide further inquiry by students rather than provide answers for them.

Maintaining Grading Consistency in Multi-sectioned Courses (for course heads)

- Communicate your grading policies, standards, and criteria to teaching assistants, graders, and students in your course.

- Discuss your expectations about all facets of grading (criteria, timeliness, consistency, grade disputes, etc) with your teaching assistants and graders.

- Encourage teaching assistants and graders to share grading concerns and questions with you.

- have teaching assistants grade assignments for students not in their section or lab to curb favoritism (N.B. this strategy puts the emphasis on the evaluative, rather than the teaching, function of grading);

- have each section of an exam graded by only one teaching assistant or grader to ensure consistency across the board;

- have teaching assistants and graders grade student work at the same time in the same place so they can compare their grades on certain sections and arrive at consensus.

- Include your grading policies, procedures, and standards in your syllabus.

- Avoid modifying your policies, including those on late work, once you’ve communicated them to students.

- Distribute your grading criteria to students at the beginning of the term and remind them of the relevant criteria when assigning and returning work.

- Keep in-class discussion of grades to a minimum, focusing rather on course learning goals.

For a comprehensive look at grading, see the chapter “Grading Practices” from Barbara Gross Davis’s Tools for Teaching.

Teaching Guides

- Online Course Development Resources

- Principles & Frameworks

- Pedagogies & Strategies

- Reflecting & Assessing

- Challenges & Opportunities

- Populations & Contexts

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

Scoring & Grading Practices

Introduction*.

Assigning students grades is an important component of teaching, and many school districts issue progress reports, interim reports, or midterm grades as well as final semester grades. Traditionally, these reports were printed on paper and sent home with students or mailed to students’ homes. Increasingly, school districts are using web-based grade management systems that allow parents to access their child’s grades on each assessment and the progress reports and final grades.

Grading can be frustrating for teachers as there are many factors to consider. In addition, report cards typically summarize in brief format a variety of assessments and so cannot provide much information about students’ strengths and weaknesses. This means that report cards focus more on assessment of learning than assessment for learning. Several decisions must be made when assigning students’ grades, and schools often have detailed policies that teachers must follow. In this chapter, we consider major questions associated with grading.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to

- Define the purpose of grading;

- Identify classroom-level grading practices that align with purpose;

- Implement researched-based grading & reporting practices;

- Analyze the effectiveness of traditional grading practices to report student learning fully.

Purpose of Grading

Beginning with an understanding of purpose is key to developing effective grading practices. Susan Brookhart has written a lot about grading practices and encourages educators to focus first on determining what they believe about the purpose of grading. In “ Starting the Conversation about Grading ” (2011), Brookhart asserted:

I cannot emphasize strongly enough that getting sidetracked with details of scaling (letters, percentages, or rubrics? Zeros or not? No Ds or Fs?) or policies (What should we do with late or missing work? How can we report behavior? What will we do about academic honors and awards?) before you tackle the question of what a grade means in the first place will lead to trouble . Logic, my own experience, and the research and practice of others (Cox & Olsen, 2009; Guskey & Bailey, 2010; McMunn, Schenck, & McColskey, 2003) all scream that this is the case.

Grading scales and reporting policies can be discussed productively once you agree on the main purpose of grades. For example, if a school decides that academic grades should reflect achievement only, then teachers need to handle missed work in some other way than assigning an F or a zero. Once a school staff gets to this point, there are plenty of resources they can use to work out the details (see Brookhart, 2011; O’Connor, 2009). The important thing is to examine beliefs and assumptions about the meaning and purpose of grades first . Without a clear sense of what grading reform is trying to accomplish, not much will happen.

Take some time to reflect on what you believe a grade should represent. Consider how the school districts below define the purpose of grading in their grading philosophy and compare it to a district you work in or are familiar with.

- Glenpool School District Grading Philosophy (OK)

- West Des Moines Community Schools Grading Philosophy (IA)

According to Brookhart, it is essential that educators first answer the question, “What is the purpose of a grade?” before deciding on grading practices within their classroom. Once a teacher defines their purpose, they should then check to make sure their purpose aligns with the school’s grading policy. A good supporting question when defining the purpose of a grade might be, “Is your purpose as a teacher to select talent, or is it to develop talent?” The answer will define not only how you approach grading but probably most aspects of your teaching practice.

According to Guskey (2015), researchers found that teachers and school leaders identify six common purposes for grades:

- Communicate information about student learning to parents;

- Provide information to students for self-reflection;

- Select, identify, or group students;

- Incentivize students to learn;

- Evaluate the quality of instruction; and

- Provide evidence of a student’s lack of effort.

No single grading instrument can accurately report all six of the aspects above to the fullest extent. Therefore, in an attempt to make their grading system more transparent and consistent, some schools have done the hard work of clarifying their purpose for grading. In the next section, we will explore a particular approach to grading with a specific purpose that seems to be a growing trend in schools across the country.

Reflection Questions

Accuracy Question: Do the grades I report accurately reflect my students’ true level of understanding?

Confidence Question: Do my grading practices contribute to student confidence or do they raise anxiety?

(Schimmer, 2016)

Adopting a Standards-Based Mindset

Many school districts have started looking for ways to make their grading practices more transparent. One of the biggest trends you will find in the literature is the idea of standards-based grading, sometimes also referred to as standards-referenced, criterion-referenced, or mastery grading. There are various forms of this idea being implemented and tested. As a novice educator, you should be aware of this concept as you may end up in a district that uses a version of this grading philosophy, or you may find that certain aspects may align strongly with your philosophy and choose to integrate them into your future grading practices at the classroom level.

School districts that shift their grading practices to a standards-based approach have a clearly defined purpose for what grades represent. Educational experts contend that in a standards-based grading mindset, the purpose of grading is to report where a student is in relation to a specific learning target (Brookhart, 2009; Dueck, 2014; Guskey, 2015; Popham, 2017; Schimmer, 2016). In adopting this belief, student effort, participation, past attempts, attendance, behavior, punctuality, etc. are not a factor in the final grade but are reported separately. This belief that grades should reflect student mastery or understanding of specific standards only contrasts with traditional grading practices that often factor in non-academic skills and dispositions. For an example, consider reading how Adam Dyche , Social Studies Dept. Chair at Waubonsie Valley High School defines a Standards-Based Mindset .

“The standards-based mindset is not about establishing flawless formulas, but rather a way for teachers to THINK as they examine the evidence of learning students produce” (Schimmer, 2016, p.61).

Common Grading Practices

Take some time to reflect on the problems identified in the article Why It’s Crucial – And Really Hard – To Talk About More Equitable Grading to see how different grading practices can not only present misleading information to students and parents, but also undermine a clear purpose of grading.

Defining the purpose of grading is only effective if the practices used to determine students’ grades support the stated purpose. According to Guskey (2015), most teachers agree that grades should reflect how well students have demonstrated mastery of the established learning goals. Still, teachers use a variety of criteria to determine grades that often don’t align with that purpose. By not reflecting on grading practices, a teacher may inadvertently assign scores to students in a manner that does not align with their beliefs about what that grade should represent. Traditional methods of calculating grades include weighted averages, averaging, and total points earned. The key takeaway here is not that every teacher should assume the same grading procedures but that all teachers should take a moment to reflect on how their grading practices align with either the school’s or their purpose of grading statement.

The best way to align grading practices with purpose is through sound assessment practices. The problem is that too often, we as teachers adopt grading practices that do not align with effective assessment practices (Schimmer, 2016). Some commonly used grading practices may be in direct opposition to assigning a grade that reports student mastery of learning objectives, including averaging scores, assigning zeros, giving extra credit, and assessing penalties for behavior (Guskey, 2015; Schimmer, 2016; Dueck, 2014). The problem with these grading practices is that they distort the ability of the grade to accurately report student understanding of the learning objectives. Next, we will present some questions you can ask yourself when you begin to set up your grading policies and discuss some potential strengths and weaknesses of common approaches.

How are various assignments and assessments weighted?*

Students typically complete various assignments during a grading period, such as homework, quizzes, performance assessments, etc. Teachers have to decide—preferably before the grading period begins—how each assignment will be weighted. For example, a sixth-grade math teacher may decide to weight the grades in the following manner:

Deciding how to weight assignments should be done carefully as it communicates to students and parents what teachers believe is important, and also may be used to decide how much effort students will exert (e.g. “If homework is only worth 5 percent, it is not worth completing twice a week”). Notice in the presentation below how your choices in how many points to assign a particular assignment may impact the final grade calculation.

Read or Listen to Jennifer Gonzalez’s blog post, How Accurate Are Your Grades? Gonzalez presents questions teachers should consider when planning how their grading process will work in their classroom.

Should scores be averaged to calculate the final grade?

How we think about learning influences how we grade, and our actions (grading) show our students what we value about learning. One teacher action that a common grading practice is to average scores to tabulate a final grade. When averaging grades, teachers calculate the sum of all points earned during a grading period and divide that sum by the total number of points possible. This process determines the mean, or average, which can be reported as a percentage or letter grade (i.e., C- may be equivalent to 70%). The problem with averaging scores to determine grades is that it may not accurately describe current levels of student understanding. Consider the example of two students in Figure 1. Student 1 completed all homework assignments (HW) for full credit but showed limited understanding on quizzes (Qz) and tests. Student 2 did not complete assigned homework but demonstrated sufficient understanding on quizzes and tests. Critics of using the averaging approach would argue that averaging the scores for these students does not provide an accurate representation of their current level of understanding.

| Student | HW1 | HW2 | HW3 | Qz1 | HW4 | HW5 | HW6 | HW7 | Qz2 | HW8 | Test | Avg. | Grade |

| 1 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 6 | 10 | 63 | 77 | C |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 89 | 53 | F |

Should zeros or penalties be assigned for missing and late work?

In the previous example (Figure 1), Student 2 was assigned zeros for missing work. This practice of assigning zeros is similar to assigning penalties to student work based on behavioral issues such as late submission. Penalties decrease the accuracy of our grading and are not proven to increase student interest or effort (Schimmer, 2016). Especially when using a 100-point grading scale, using zeros unproportionally pulls a student’s grade down. Similarly, penalties are used to encourage things like timeliness, but that is not reported during the grading process, only the lower score, which, after being penalized, now reflects a lower degree of understanding.

Should homework scores be included in the final grade calculation?

To give homework or to not give homework? This question has been debated and researched with mixed results. John Hattie’s work looking at the effect size of homework on student learning suggests that overall, homework has a small to modest effect on student learning. However, there seems to be a greater effect for students as they age (HS > MS > Elem), and that homework seems most impactful when it is short, focused on material students are ready for, and when students have input. In the end, the question may not be whether you should give homework, but what you should do with it once students complete it.

In a classroom using traditional grading practices, homework typically accounts for a significant portion of the final grade. Even if the homework is a small percentage of the final grade, it is a form of summative assessment. In a standards-based classroom, homework is often viewed as practice and an opportunity to receive feedback without a score or for a very small score. In other words, using homework as a formative assessment.

A common concern teachers have is that if homework is not graded, students will not do it. Schimmer (2016) argues that adopting the mindset of, “if I don’t grade it, they won’t do it” suggests that students have no interest in learning and reduces school to an exercise of accumulating points. Another disadvantage of including homework in the final grade calculation is that it can distort the final grade due to factors such as cheating, confusion, unreadiness, and factors outside of the student’s control.

Should social skills or effort be included?*

- Read an article by Douglas Reeves, Lee Ann Jung, and Ken O’Connor (2017) for an overview of four common grading practices that may do more harm than good .

- Read what Joe Feldman says about What Traditional Classroom Grading Gets Wrong .

- Rick Wormeli writes a lot about grading practices. See what he identifies as Grading Malpractice .

- Ken O’Connor’s 15 Fixes for Grading

Elementary school teachers are more likely than middle or high school teachers to include some social skills in report cards (Popham, 2005). These may be included as separate criteria in the report card or weighted into the grade for that subject. For example, the grade for mathematics may include an assessment of group cooperation or self-regulation during mathematics lessons. Some schools and teachers endorse including social skills in the grading process, arguing that developing such skills is important for young students and that students need to learn to work with others and manage their behaviors to be successful. Others believe that grades in subject areas should be based on cognitive performances—and that if assessments of social skills are made, they should be separated from the subject grade on the report card. Clear criteria, such as those contained in analytical scoring rubrics, should be used if social skills are graded.

Teachers often find it difficult to decide whether effort and improvement should be included as a component of grades. One approach is for teachers to ask students to submit drafts of an assignment and make improvements based on the feedback they receive. The grade for the assignment may include some combination of the score for the drafts, the final version, and the amount of improvement the students made based on the feedback provided.

A more controversial approach is basing grades on effort when students try really hard day after day but still cannot complete their assignments well. These students could have identified special needs or be recent immigrants that have limited English skills. Some school districts have guidelines for handling such cases. One disadvantage of using improvement as a component of grades is that the most competent students in the class may do very well initially and have little room for improvement—unless teachers are skilled at providing additional assignments that will help challenge these students.

Teachers often use “hodgepodge grading,” i.e. a combination of achievement, effort, growth, attitude or class conduct, homework, and class participation. A survey of over 8,500 middle and high school students in the US state of Virginia supported the hodgepodge practices commonly used by their teachers (Cross & Frary, 1999).

Should grades be calculated on a curve?*

Two options are commonly used: absolute grading and relative grading. In absolute grading, grades are assigned based on criteria the teacher has devised. If an English teacher has established a level of proficiency needed to obtain an A and no student meets that level, then no A’s will be given. Alternatively, if every student meets the established level, then all the students will get A’s (Popham, 2005). Absolute grading systems may use letter grades or pass/fail.

In relative grading, the teacher ranks students’ performances from worst to best (or best to worst); those at the top get high grades, those in the middle moderate grades, and those at the bottom low. This is often described as “grading on the curve” and can be useful to compensate for an examination or assignment that students find much easier or harder than the teacher expected.

However, relative grading can be unfair to students because the comparisons are typically within one class, so an A in one class may not represent the level of performance of an A in another class. Relative grading systems may discourage students from helping each other improve as students compete for limited rewards. Bishop (1999) argues that grading on the curve gives students a personal interest in persuading each other not to study as a serious student makes it more difficult for others to get good grades.

What kinds of grade descriptions should be used?*

Traditionally, a letter grade system is used (e.g. A, B, C, D, F ) for each subject. The advantages of these grade descriptions are they are convenient, simple, and can be averaged easily. However, they do not indicate what objectives the student has or has not met or students’ specific strengths and weaknesses (Linn & Miller 2005). Elementary schools often use a pass-fail (or satisfactory-unsatisfactory) system, and some high schools and colleges do as well. Pass-fail systems in high school and college allow students to explore new areas and take risks on subjects that they may have limited preparation for or is not part of their major (Linn & Miller 2005). While a pass-fail system is easy to use, it offers even less information about students’ level of learning.

A pass-fail system is also used in classes taught under a mastery-learning approach in which students are expected to demonstrate mastery of all the objectives to receive course credit. Under these conditions, it is clear that a pass means that the student has demonstrated mastery of all the objectives.

Some schools have implemented a checklist of the objectives in subject areas to replace the traditional letter grade system. Students are rated on each objective using descriptors such as Proficient, Partially Proficient, and Needs Improvement. For example, the checklist for students in a fourth-grade class in California may include the four types of writing that are required by the English language state content standards

- writing narratives

- writing responses to literature

- writing information reports

- writing summaries

The advantages of this approach are that it communicates students’ strengths and weaknesses clearly, and it reminds the students and parents of the objectives of the school. However, if too many objectives are included, the lists can become so long that they are difficult to understand.

Grading In PE (or skills-based classrooms)

If you are currently teaching, or plan to teach in a heavily skills-based content area (i.e., physical education, art, music, world language, etc.), then you may be thinking that this grading discussion doesn’t pertain to you. If that is the case, then you should check out Joey Feith ’s blog titled Meaningful Grades in Physical Education . The emphasis is on PE, but the ideas and practices could easily be applied to other skill-based content areas and traditional classroom settings.

Grading Practices to Consider

There may be no perfect answer to the problem of assigning student grades. However, there are a few practices that you might consider making a part of your grading policy if your goal is for your grades to accurately depict student achievement of learning objectives.

Identify Standards to Assess

The first place you should start is by identifying specific learning targets for your grading period. The best way to fight grade inflation (or deflation) is through clearly defined standards and quality assessments that align with those standards (Guskey, 2015; Heff, 2019). Similar to writing learning objectives for your daily lessons and assignments, identify the main objectives that you plan to summatively assess for the semester up front. From there, you can track student progress throughout the semester. You might also consider having your students track their progress, see how Dan Meyer used a concept checklist in his math classes.

Use a 4 Point Scale

Consider switching from the traditional 100-point grading scale to a 4-point scale. According to Guskey (2015), a four-point scale provides a smaller number of grading categories, which will result in a more reliable score of student learning. In the traditional 100-point scale, each grade category has a 10-point spread (ex. C 70-79). In addition, there are 60 levels of failure (0-59) and only 40 levels of passing (60-100). This creates an imbalance in the final grade calculation. The 4-point model removes this issue by assigning each grade level a single-point spread (0-F, 1-D, 2-C, 3-B, 4-A).

A 4-point scale is familiar to students as it reflects the GPA format and can be converted to a percentage score for grade reporting. Schimmer (2016) suggests that 4-point scores could be averaged at the end of the grading cycle and converted to a traditional grading scale. For example, averages between 3.25 and 4.0 would equate to an A, 2.50 to 3.24 equal a B, 1.75 to 2.49 equal a C, and 1.00 to 1.74 equal a D. Some schools have even suggested reviewing all of the scores for student learning and considering the median and mode scores rather relying solely on the average score. For example, see how Bremerton Schools outlines how student grades will be calculated using a 4-point scale .

Remove Grade Distortion

The potential for grade distortion when applying penalties and zeroes to students’ grades has been addressed earlier in the chapter. Removing these practices from your grading may help your final grades more accurately reflect student understanding. A similar practice is offering extra credit. When extra credit is added to a student’s score, the grade may or may not reflect the student’s current level of understanding. For example, suppose a student was to earn extra credit points for bringing items to class, attending an event, or completing some task that is not directly aligned with the objective(s) of the assessment. In that case, the additional points earned distort the grade. An alternative to offering extra credit to improve a score would be to allow students to revise their work without penalty. Reassessment is a key component of ensuring that your grades reflect the current level of understanding of your students. Consider adjusting scores to reflect current understanding after students have revised work or completed alternative assessments. For example, see how North Jr High allows students to retest and revise assessments (slides 10 & 11). Also, consider Guskey’s (2023) defense for how reassessment is supported by research in his article, Giving Retakes Their Best Chance to Improve Learning . Lastly, consider the strategies suggested for limiting the number of retake opportunities in the article, How Many Retakes Should Students Get?

Examples of Standards-Based Grading Approaches in Different Content Areas

- Math-Dan Meyer

- Math-Dane Ehlert

- Social Studies

Discussion Questions

- Do grades motivate learning? Why or why not?

- What does a grade represent? What does it tell us about a student? What does it not tell us?

- If I get an A and you get a C, is that “fair”? Does it need to be? Is that a reasonable expectation in a classroom?

- What are some potential problems with the traditional A–F grading system in a classroom? What are the benefits?

- What are some potential pedagogical benefits of removing grades from a classroom? Are there potential downsides? How could we avoid those issues?

- How have grades affected your approach to learning in the past?

- Think of a time when grading helped you improve. What was helpful about it specifically? Why has it stuck with you?

- Think of a time when grading has impacted you negatively. How did it impact you? How did it affect your approach going forward? Why has it stuck with you?

Discussion Questions by Liz Delf, Rob Drummond, and Kristy Kelly are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

There are many things to consider before entering your classroom for the first time, and how you grade your students should be one area that you give some considerable thought. You probably won’t have your perfect grading policy figured out the first time. However, you should begin by asking yourself, what is the purpose of grades in my classroom? From there, you can review any policies your district might have and ensure that your thoughts about grading align with your district. Regardless, you should take the time to think through how your grading policies will encourage students to engage in the learning process and how your final reporting will reflect student learning.

Extend Your Learning

- I strongly recommend Dueck’s book, Grading Smarter Not Harder . It is an easy read and has a lot of great ideas and resources for use in the classroom.

- If you are interested in hearing more about Dueck’s ideas, consider watching his webinar . I think this might be a great conversation starter with other teachers.

- If Rick Wormeli’s ideas interest you, then you can find numerous videos online where he discusses these ideas in greater detail. If you start with his video on Redo’s, Retakes, and Do-Overs , then you can follow the trail to other videos. Or, google “Rick Wormeli grading videos” and you can pick based on your interest.

- If you are teaching or plan to teach math, then you should check out Dan Meyer’s The Comprehensive Math Assessment Resource . The ideas presented here could easily be translated into any content area, so don’t shy away just because it is math related.

- Can’t get enough? Check out these Suggested Readings

Summarizing Key Understandings

References & attribution.

Attribution: Sections noted with “*” were adapted in part from Ch. 15 Teacher made assessment strategies by Kevin Seifert and Rosemary Sutton, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Brookhart, S. M. (2009). Grading (2nd ed.). New York: Merrill.

Dueck, M. (2014). Grading smarter not harder. ASCD

Guskey, T. R. (2015). On your mark: Challenging the conventions of grading and reporting. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press

Popham, J. W. (2017). Classroom assessment: What teachers need to know (8th ed.). New York: Pearson

Schimmer, T. (2016). Grading from the inside out: Bringing accuracy to student assessment through standards-based mindset. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press

Teaching Methods & Practices Copyright © by Jason Proctor is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Log in with your Gradescope account

Or log in with, deliver and grade your assessments anywhere.

Grade All Subjects

Gradescope supports variable-length assignments (problem sets & projects) as well as fixed-template assignments (worksheets, quizzes, bubble sheets, and exams)..

Total Points

Autograder score, failed tests, style - manual grading.

Use Your Existing Assignments

No need to alter your assignments. grade paper-based, digital, and code assignments in half the time..

Quick, Flexible Grading

Apply detailed feedback with just one click. make rubric changes that apply to previously graded work..

Gain Valuable Insight

See question and rubric-level statistics to better understand what your students know. easily export grades and data..

Feedback Delivered Instantly

Return graded assignments with a single click (optional). handle regrade requests online, freeing up office hours..

Answer Groups & AI-assisted Grading

Grade groups of similar answers at once. for some question types, gradescope ai automatically forms groups for you to review..

Built by Instructors

Our team cares deeply about your grading experience. we built gradescope for ourselves while in grad school and love feedback from our users., join over 140,000 instructors.

Sign up as an...

Assessment Rubrics

A rubric is commonly defined as a tool that articulates the expectations for an assignment by listing criteria, and for each criteria, describing levels of quality (Andrade, 2000; Arter & Chappuis, 2007; Stiggins, 2001). Criteria are used in determining the level at which student work meets expectations. Markers of quality give students a clear idea about what must be done to demonstrate a certain level of mastery, understanding, or proficiency (i.e., "Exceeds Expectations" does xyz, "Meets Expectations" does only xy or yz, "Developing" does only x or y or z). Rubrics can be used for any assignment in a course, or for any way in which students are asked to demonstrate what they've learned. They can also be used to facilitate self and peer-reviews of student work.

Rubrics aren't just for summative evaluation. They can be used as a teaching tool as well. When used as part of a formative assessment, they can help students understand both the holistic nature and/or specific analytics of learning expected, the level of learning expected, and then make decisions about their current level of learning to inform revision and improvement (Reddy & Andrade, 2010).

Why use rubrics?

Rubrics help instructors:

Provide students with feedback that is clear, directed and focused on ways to improve learning.

Demystify assignment expectations so students can focus on the work instead of guessing "what the instructor wants."

Reduce time spent on grading and develop consistency in how you evaluate student learning across students and throughout a class.

Rubrics help students:

Focus their efforts on completing assignments in line with clearly set expectations.

Self and Peer-reflect on their learning, making informed changes to achieve the desired learning level.

Developing a Rubric

During the process of developing a rubric, instructors might:

Select an assignment for your course - ideally one you identify as time intensive to grade, or students report as having unclear expectations.

Decide what you want students to demonstrate about their learning through that assignment. These are your criteria.

Identify the markers of quality on which you feel comfortable evaluating students’ level of learning - often along with a numerical scale (i.e., "Accomplished," "Emerging," "Beginning" for a developmental approach).

Give students the rubric ahead of time. Advise them to use it in guiding their completion of the assignment.

It can be overwhelming to create a rubric for every assignment in a class at once, so start by creating one rubric for one assignment. See how it goes and develop more from there! Also, do not reinvent the wheel. Rubric templates and examples exist all over the Internet, or consider asking colleagues if they have developed rubrics for similar assignments.

Sample Rubrics

Examples of holistic and analytic rubrics : see Tables 2 & 3 in “Rubrics: Tools for Making Learning Goals and Evaluation Criteria Explicit for Both Teachers and Learners” (Allen & Tanner, 2006)

Examples across assessment types : see “Creating and Using Rubrics,” Carnegie Mellon Eberly Center for Teaching Excellence and & Educational Innovation

“VALUE Rubrics” : see the Association of American Colleges and Universities set of free, downloadable rubrics, with foci including creative thinking, problem solving, and information literacy.

Andrade, H. 2000. Using rubrics to promote thinking and learning. Educational Leadership 57, no. 5: 13–18. Arter, J., and J. Chappuis. 2007. Creating and recognizing quality rubrics. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Merrill Prentice Hall. Stiggins, R.J. 2001. Student-involved classroom assessment. 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Reddy, Y., & Andrade, H. (2010). A review of rubric use in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation In Higher Education, 35(4), 435-448.

Tips for Grading Efficiently and Fairly

How do i grade well on a deadline, ten tips for fair and efficient grading.

- Develop clear assignment expectations before the assignment is handed out and share them with your students.

- Use a rubric to specify grading criteria.

- Grade all responses to the same question together.

- Anonymize assignments when grading.

- Skim a sample of the assignment submissions before grading.

- Limit the scope of your feedback to 2-3 major corrections when possible.

- Create a bank of comments.

- Take regular breaks.

- Create wrappers for your assignments.

- Prepare for grading challenges.

Read below for more explanation, description, examples, and resource links.

1. Develop clear assignment expectations before the assignment is handed out and share them with your students.

Remember your students will come from a variety of different backgrounds and have different amounts of support in completing their work. Students of privilege will be less impacted by poor directions because they are supported by a network that has informal knowledge about college. For underserved student populations, like first-generation college students, students of color, and other minoritized populations, the lack of clear expectations can cause them to stumble—not because they can’t do what you’re asking of them, but because they didn’t understand what you were asking of them. For this reason, focus on providing clear and widely understood expectations and directions. Doing this is one of the best ways to benefit all of your students and make grading less frustrating for you as well!

With your teaching team, create a grading policy to give students at the beginning of the course. This should include things like: how you will handle late assignments, how students can ask questions about grades, a clear process for how students can challenge a grade respectfully, how quickly students can expect feedback, and how grades and feedback will be shared.

2. Use a Rubric to specify grading criteria.

A rubric shows students how an assignment will be scored, and typically outlines specific criteria students must meet and what constitutes a complete and successful assignment. See examples and read more about Grading and Performance Rubrics from the Eberly Center. You will see more about grading with rubrics in Canvas in an upcoming page. In developing a Rubric, you should work with your teaching team.

3. Grade all responses to the same question together.

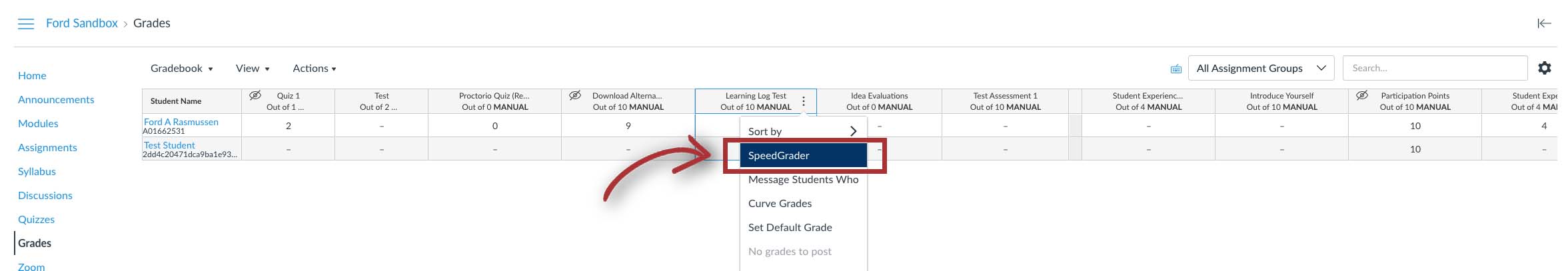

Imagine you are grading an exam with multiple questions. Whether they are essay responses, or lengthy calculations, your grading will be more consistent for each student if you grade all responses to question 1 before grading question 2. You will be better able to track themes or common problems across students, and be able to more easily apply consistent feedback. Later in today’s content, we will cover Speedgrader, which allows you to grade by question.

4. Anonymize assignments when grading.

To “anonymize” an assignment means you remove student identifying information, so you don’t know which student you are grading. This practice helps to minimize bias, and is commonly used in screening job applications. Even the most well-intentioned teachers still have feelings and implicit biases, i.e. attitudes that unconsciously affect actions, that affect their grading (Boysen & Vogel, 2009). Information on how to anonymize assignments when grading in Canvas can be found here: Anonymous Grading in Canvas .

5. Skim a sample of the assignment submissions before grading.

Especially when you are new to grading and to a particular assignment, it can be hard to calibrate your expectations. Often, the first grades you assign will be too harsh or too easy. As you grade more students’ assignments you will start to find the right balance of how discriminating you want to be, the amount and level of corrections you offer, and the time you can spend on each assignment. By skimming the assignments beforehand or assigning grades in pencil, you can help ensure all of your students are receiving consistent treatment.

6. Limit the scope of your feedback to 2-3 major corrections when possible.

You don’t always need to comment on everything that is wrong on an assignment. This is inefficient both in terms of your time and student learning. Focus on the most important and clear corrections, and provide instructions for improvement. This will make it easier for your students to understand the most important aspects of the assignment.

7. Create a bank of comments.

You will likely find yourself offering the same comments repeatedly. To save time you can create abbreviations (e.g. NC = needs citation) or a numbered bank of comments with detailed corrections which you share with the students. Then, as you grade, all you need to do is put the appropriate abbreviation or number that corresponds to the comment and correction in your bank.

8. Take regular breaks.

Grading all of your assignments without a break may mean you are more likely to be tired or frustrated at the end. This may make you more harsh or less detailed in your feedback. Instead, make a schedule with breaks and rewards during the time you allot for grading.

9. Create wrappers for your assignments.

Wrappers are short worksheets that come before or after an assignment. These can help identify student preferences for feedback as well as serve as reflection tools, which aid in student learning. Wrappers can ask things like: What grade do you expect to receive on this assignment? What are you most proud of in this assignment? Is there anything in particular you want me to focus on or provide feedback on while grading this assignment?

This information can help you decide how best to provide feedback. It can also help students make connections between their effort, your feedback, their grade, and how they can improve ( TEAL Center Fact Sheet No. 4 , n.d.). Read more about Metacognitive Wrapper Questions.

10. Prepare for grading challenges.

A student challenging a grade can be both an intimidating and stressful situation. This is an area where it is extremely important to be on the same page as your lead instructor. Make sure you discuss this eventuality beforehand as well as any individual cases that arise. Having a clear policy will help you navigate the situation easily in the moment. Discuss this with your teaching team!

Consider creating a policy in your course that creates space and time for you and the student to review the assignment and then have a calm discussion. Some policy suggestions include: asking students to wait at least 24 hours to contact you about their grade, asking students to email you to schedule a face-to-face or private virtual meeting and summarize their complaint, or specifying that you will not re-grade the assignment with the student present. Don’t be afraid to do what you think is right. Sometimes, the student will be mistaken and you can stand by what you originally said. Other times, you might have made a mistake – simply acknowledge it and correct it. It is not a sign of weakness for you to admit the mistake. Review L&S Grade Appeal Information if you are teaching an L&S course.

Boysen, G. A., & Vogel, D. L. (2009). Bias in the Classroom: Types, Frequencies, and Responses. Teaching of Psychology , 36 (1), 12–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00986280802529038

Staats Cheryl et al. (2017). State of the Science: Implicit Bias Review 2017. Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity. Retrieved June 21, 2020, from http://kirwaninstitute.osu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/2017-SOTS-final-draft-02.pdf

TEAL Center Fact Sheet No. 4: Metacognitive Processes . (n.d.). LINCS | Adult Education and Literacy | U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved June 24, 2020, from https://lincs.ed.gov/state-resources/federal-initiatives/teal/guide/metacognitive

- Help Center

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Submit feedback

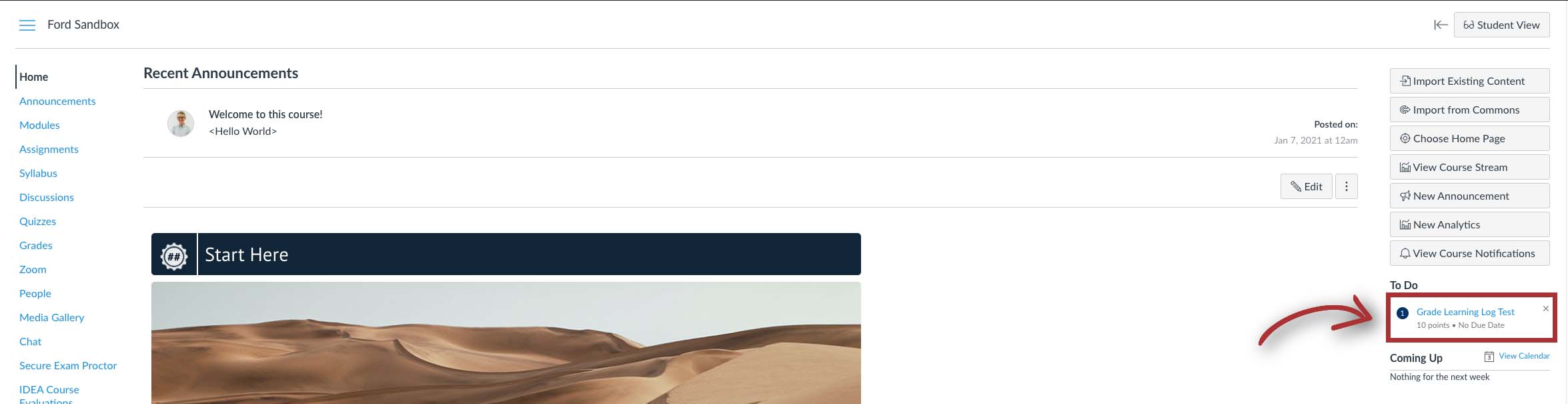

- Announcements

- Grade and track assignments

- Grade assignments

Grade & return an assignment

This article is for teachers.

In Classroom, you can give a numeric grade, leave comment-only feedback, or do both. You can also return assignments without grades.

You can grade and return work from:

- The Student work page.

- The Classroom grading tool.

- The Grades page.

For Grades page instructions, go to View or update your gradebook .

For practice sets, learn how to grade a practice set assignment .

You can download grades for one assignment or for all assignments in a class.

Display assignments & import quiz grades

Before viewing a student's assignment, you can see the status of student work, and the number of students in each category.

Go to classroom.google.com and click Sign In.

Sign in with your Google Account. For example, [email protected] or [email protected] . Learn more .

- Click the class.

- At the top, click Classwork .

- Select the assignment to display.

- Tip: You can only get to the student work page when the number isn't "0" for both "Turned in" and "Assigned."

- Assigned —Work that students have to turn in, including missing or unsubmitted work

- Turned in —Work that students turned in

- Graded —Graded work you’ve returned

- Returned —Ungraded (non-graded) work you’ve returned

- (Optional) To see the students in a category, click Turned in , Assigned , Graded , or Returned .

- To check a student’s submission, click on the assignment thumbnail.

- At the top-right, click Import Grades .

- Click Import to confirm. The grades autofill next to the students’ names. Note: Importing grades overwrites any grades already entered.

- (Optional) To return grades, next to each student whose grade you want to return, check the box and click Return . Students can see their grade in Classroom and Forms.

Enter, review, or change grades

- Red—Missing work.

- Green—Turned in work or draft grade.

- Black—Returned work.

- Click the Student Work tab.

The default grading scale is numerical based on the total points of the assignment. For expanded grading scales option, Education Plus and Teaching and Learning Upgrade editions have it. You can align Classroom grading to your school's system whether:

- For example, letter grades A to F or proficiency unsatisfactory to excellent.

- For example, 4 point scales.

- For example, emojis.

Grading scales features work with:

- Average grade calculation

- SIS integration

- Practice sets and Forms auto-grading

You can enter a grade either for the number of points or, if you have grading scales set up, based on the levels on the grading scale. For example, if you have letter grades set up in your class and you assign a 10 point assignment, under “Grade,” you can:

- Select Good 8/10 from the dropdown menu

- You and your co-teachers can find all grades in both points value and the level it corresponds to.

A student can find both the points value and the level it corresponds to if a grade is returned.

- Next to the student's name, enter the grade. The grade saves automatically.

- Enter grades for any other students.

You can enter grades and personalize your students feedback with the Classroom grading tool.

- Go to classroom.google.com .

- Optional: Under the classwork filter, select a grading period. Learn how to create or edit grading periods .

- Next to the student’s name, and under the relevant assignment, enter the grade.

- The grade saves as a draft.

- Select Good 8/10 from the dropdown menu.

- If a grade returns, a student can find both the points value and the level it corresponds to.

- Optional: Enter grades for any other students and assignments.

Tip: You can return assignments without a grade.

- On the left, click a student's name.

- Click See history .

- Next to a student’s name, click the grade you want to change.

- Enter a new number. The new grade saves automatically.

Return work or download grades

Students can’t edit any files attached to an assignment until you return it. When you return work, students get notifications if they’re turned on. You can return work, with or without a grade, to one or more students at a time.

You can start with the default grading scale options, or create your own grading scale.

- Proficiency

- Letter grades

- 4 point scale

- Create your own: Creates a custom grading scale.

- Edit the level and values of your grading scale.

- Click Select .

- At the top right, click Save .

- When you edit a default grading scale, it becomes a custom grading scale.

- When you remove a custom grading scale that was previously used in a class, a confirmation dialog displays, and you won’t be able to access it again.

- Next to the student's name, and under the relevant assignment, enter the grade.

- The student’s assignment is marked Returned.

- On the left, check the box next to each student whose assignment you want to return.

- Click Return and confirm.

Download grades to Sheets

Download grades to a CSV file

- To download grades for one assignment, select Download these grades as CSV .

- To download all grades for the class, select Download all grades as CSV . The file saves to your computer.

Related topics

- Set up grading

- Give feedback on assignments

- Grade and return question answers

- Create and grade quizzes

- Grade & track practice set assignments

- Use a screen reader with Classroom on your computer

- Export grades to your SIS

Was this helpful?

Need more help, try these next steps:.

Assessing Learning

Grading + Rubrics

Some of the most difficult and time-consuming work that instructors and TAs do is grading student work. Whether you’re an experienced teacher, or just starting out, you will find tips on this page to improve grading efficiency, make grading more equitable, fair, and clear to your students.

Efficient Grading Equitable Grading Rubrics

Purpose of Grading

Ultimately, your assessments should be structured and graded in ways that motivate learning, rather than punish mistakes. We grade student work to provide feedback, open lines of communication, motivate improvement, and evaluate performance.

Provide Feedback - Grading gives the opportunity to provide short, targeted feedback. Limit overly critical feedback, and where possible, highlight at least one thing students did well, and one area they can improve upon.

Open Lines of Communication - The goal of assessment is to enable both parties, teacher and student, to learn where they stand relative to the learning goals. Our grading should facilitate students’ reflection on their learning, allow them to demonstrate what they understand, and discover where they are struggling.

Motivate Improvement - It’s important for our assessments to validate students’ progress, while encouraging them to learn from mistakes. Use light-touch feedback techniques , and provide opportunities for students to improve their grades. Where possible, let them redo, revise, and repeat.

Evaluate Performance - Grades are an evaluation of performance on a given task. Use specific performance criteria derived from the course learning objectives in your grading, and communicate to students what those performance criteria are before the assessment.

Make Grading Efficient

It benefits our students to receive feedback on their work in a timely manner, and we generally want to cut down the time we spend grading. You can strategize ways to make grading more efficient by using simplified metrics appropriate for the assignment, timing tools, and incorporating technologies.

UCSB Educational Technologies for Grading

Grading Assignments u sing Gradescope

Using Rubrics in Canvas

Using Gradescope for handwritten work and multiple-choice exams

iClicker for participation, polling and measuring student understanding

Simplified Grading Metrics or ‘Light Grading’

For some lower-stakes assessments, consider using simplified metrics like plus-check-minus rather than letter grades or percentages so you can grade more quickly.

Plus-Check-Minus