What this handout is about

This handout will provide a broad overview of gathering and using evidence. It will help you decide what counts as evidence, put evidence to work in your writing, and determine whether you have enough evidence. It will also offer links to additional resources.

Introduction

Many papers that you write in college will require you to make an argument ; this means that you must take a position on the subject you are discussing and support that position with evidence. It’s important that you use the right kind of evidence, that you use it effectively, and that you have an appropriate amount of it. If, for example, your philosophy professor didn’t like it that you used a survey of public opinion as your primary evidence in your ethics paper, you need to find out more about what philosophers count as good evidence. If your instructor has told you that you need more analysis, suggested that you’re “just listing” points or giving a “laundry list,” or asked you how certain points are related to your argument, it may mean that you can do more to fully incorporate your evidence into your argument. Comments like “for example?,” “proof?,” “go deeper,” or “expand” in the margins of your graded paper suggest that you may need more evidence. Let’s take a look at each of these issues—understanding what counts as evidence, using evidence in your argument, and deciding whether you need more evidence.

What counts as evidence?

Before you begin gathering information for possible use as evidence in your argument, you need to be sure that you understand the purpose of your assignment. If you are working on a project for a class, look carefully at the assignment prompt. It may give you clues about what sorts of evidence you will need. Does the instructor mention any particular books you should use in writing your paper or the names of any authors who have written about your topic? How long should your paper be (longer works may require more, or more varied, evidence)? What themes or topics come up in the text of the prompt? Our handout on understanding writing assignments can help you interpret your assignment. It’s also a good idea to think over what has been said about the assignment in class and to talk with your instructor if you need clarification or guidance.

What matters to instructors?

Instructors in different academic fields expect different kinds of arguments and evidence—your chemistry paper might include graphs, charts, statistics, and other quantitative data as evidence, whereas your English paper might include passages from a novel, examples of recurring symbols, or discussions of characterization in the novel. Consider what kinds of sources and evidence you have seen in course readings and lectures. You may wish to see whether the Writing Center has a handout regarding the specific academic field you’re working in—for example, literature , sociology , or history .

What are primary and secondary sources?

A note on terminology: many researchers distinguish between primary and secondary sources of evidence (in this case, “primary” means “first” or “original,” not “most important”). Primary sources include original documents, photographs, interviews, and so forth. Secondary sources present information that has already been processed or interpreted by someone else. For example, if you are writing a paper about the movie “The Matrix,” the movie itself, an interview with the director, and production photos could serve as primary sources of evidence. A movie review from a magazine or a collection of essays about the film would be secondary sources. Depending on the context, the same item could be either a primary or a secondary source: if I am writing about people’s relationships with animals, a collection of stories about animals might be a secondary source; if I am writing about how editors gather diverse stories into collections, the same book might now function as a primary source.

Where can I find evidence?

Here are some examples of sources of information and tips about how to use them in gathering evidence. Ask your instructor if you aren’t sure whether a certain source would be appropriate for your paper.

Print and electronic sources

Books, journals, websites, newspapers, magazines, and documentary films are some of the most common sources of evidence for academic writing. Our handout on evaluating print sources will help you choose your print sources wisely, and the library has a tutorial on evaluating both print sources and websites. A librarian can help you find sources that are appropriate for the type of assignment you are completing. Just visit the reference desk at Davis or the Undergraduate Library or chat with a librarian online (the library’s IM screen name is undergradref).

Observation

Sometimes you can directly observe the thing you are interested in, by watching, listening to, touching, tasting, or smelling it. For example, if you were asked to write about Mozart’s music, you could listen to it; if your topic was how businesses attract traffic, you might go and look at window displays at the mall.

An interview is a good way to collect information that you can’t find through any other type of research. An interview can provide an expert’s opinion, biographical or first-hand experiences, and suggestions for further research.

Surveys allow you to find out some of what a group of people thinks about a topic. Designing an effective survey and interpreting the data you get can be challenging, so it’s a good idea to check with your instructor before creating or administering a survey.

Experiments

Experimental data serve as the primary form of scientific evidence. For scientific experiments, you should follow the specific guidelines of the discipline you are studying. For writing in other fields, more informal experiments might be acceptable as evidence. For example, if you want to prove that food choices in a cafeteria are affected by gender norms, you might ask classmates to undermine those norms on purpose and observe how others react. What would happen if a football player were eating dinner with his teammates and he brought a small salad and diet drink to the table, all the while murmuring about his waistline and wondering how many fat grams the salad dressing contained?

Personal experience

Using your own experiences can be a powerful way to appeal to your readers. You should, however, use personal experience only when it is appropriate to your topic, your writing goals, and your audience. Personal experience should not be your only form of evidence in most papers, and some disciplines frown on using personal experience at all. For example, a story about the microscope you received as a Christmas gift when you were nine years old is probably not applicable to your biology lab report.

Using evidence in an argument

Does evidence speak for itself.

Absolutely not. After you introduce evidence into your writing, you must say why and how this evidence supports your argument. In other words, you have to explain the significance of the evidence and its function in your paper. What turns a fact or piece of information into evidence is the connection it has with a larger claim or argument: evidence is always evidence for or against something, and you have to make that link clear.

As writers, we sometimes assume that our readers already know what we are talking about; we may be wary of elaborating too much because we think the point is obvious. But readers can’t read our minds: although they may be familiar with many of the ideas we are discussing, they don’t know what we are trying to do with those ideas unless we indicate it through explanations, organization, transitions, and so forth. Try to spell out the connections that you were making in your mind when you chose your evidence, decided where to place it in your paper, and drew conclusions based on it. Remember, you can always cut prose from your paper later if you decide that you are stating the obvious.

Here are some questions you can ask yourself about a particular bit of evidence:

- OK, I’ve just stated this point, but so what? Why is it interesting? Why should anyone care?

- What does this information imply?

- What are the consequences of thinking this way or looking at a problem this way?

- I’ve just described what something is like or how I see it, but why is it like that?

- I’ve just said that something happens—so how does it happen? How does it come to be the way it is?

- Why is this information important? Why does it matter?

- How is this idea related to my thesis? What connections exist between them? Does it support my thesis? If so, how does it do that?

- Can I give an example to illustrate this point?

Answering these questions may help you explain how your evidence is related to your overall argument.

How can I incorporate evidence into my paper?

There are many ways to present your evidence. Often, your evidence will be included as text in the body of your paper, as a quotation, paraphrase, or summary. Sometimes you might include graphs, charts, or tables; excerpts from an interview; or photographs or illustrations with accompanying captions.

When you quote, you are reproducing another writer’s words exactly as they appear on the page. Here are some tips to help you decide when to use quotations:

- Quote if you can’t say it any better and the author’s words are particularly brilliant, witty, edgy, distinctive, a good illustration of a point you’re making, or otherwise interesting.

- Quote if you are using a particularly authoritative source and you need the author’s expertise to back up your point.

- Quote if you are analyzing diction, tone, or a writer’s use of a specific word or phrase.

- Quote if you are taking a position that relies on the reader’s understanding exactly what another writer says about the topic.

Be sure to introduce each quotation you use, and always cite your sources. See our handout on quotations for more details on when to quote and how to format quotations.

Like all pieces of evidence, a quotation can’t speak for itself. If you end a paragraph with a quotation, that may be a sign that you have neglected to discuss the importance of the quotation in terms of your argument. It’s important to avoid “plop quotations,” that is, quotations that are just dropped into your paper without any introduction, discussion, or follow-up.

Paraphrasing

When you paraphrase, you take a specific section of a text and put it into your own words. Putting it into your own words doesn’t mean just changing or rearranging a few of the author’s words: to paraphrase well and avoid plagiarism, try setting your source aside and restating the sentence or paragraph you have just read, as though you were describing it to another person. Paraphrasing is different than summary because a paraphrase focuses on a particular, fairly short bit of text (like a phrase, sentence, or paragraph). You’ll need to indicate when you are paraphrasing someone else’s text by citing your source correctly, just as you would with a quotation.

When might you want to paraphrase?

- Paraphrase when you want to introduce a writer’s position, but their original words aren’t special enough to quote.

- Paraphrase when you are supporting a particular point and need to draw on a certain place in a text that supports your point—for example, when one paragraph in a source is especially relevant.

- Paraphrase when you want to present a writer’s view on a topic that differs from your position or that of another writer; you can then refute writer’s specific points in your own words after you paraphrase.

- Paraphrase when you want to comment on a particular example that another writer uses.

- Paraphrase when you need to present information that’s unlikely to be questioned.

When you summarize, you are offering an overview of an entire text, or at least a lengthy section of a text. Summary is useful when you are providing background information, grounding your own argument, or mentioning a source as a counter-argument. A summary is less nuanced than paraphrased material. It can be the most effective way to incorporate a large number of sources when you don’t have a lot of space. When you are summarizing someone else’s argument or ideas, be sure this is clear to the reader and cite your source appropriately.

Statistics, data, charts, graphs, photographs, illustrations

Sometimes the best evidence for your argument is a hard fact or visual representation of a fact. This type of evidence can be a solid backbone for your argument, but you still need to create context for your reader and draw the connections you want them to make. Remember that statistics, data, charts, graph, photographs, and illustrations are all open to interpretation. Guide the reader through the interpretation process. Again, always, cite the origin of your evidence if you didn’t produce the material you are using yourself.

Do I need more evidence?

Let’s say that you’ve identified some appropriate sources, found some evidence, explained to the reader how it fits into your overall argument, incorporated it into your draft effectively, and cited your sources. How do you tell whether you’ve got enough evidence and whether it’s working well in the service of a strong argument or analysis? Here are some techniques you can use to review your draft and assess your use of evidence.

Make a reverse outline

A reverse outline is a great technique for helping you see how each paragraph contributes to proving your thesis. When you make a reverse outline, you record the main ideas in each paragraph in a shorter (outline-like) form so that you can see at a glance what is in your paper. The reverse outline is helpful in at least three ways. First, it lets you see where you have dealt with too many topics in one paragraph (in general, you should have one main idea per paragraph). Second, the reverse outline can help you see where you need more evidence to prove your point or more analysis of that evidence. Third, the reverse outline can help you write your topic sentences: once you have decided what you want each paragraph to be about, you can write topic sentences that explain the topics of the paragraphs and state the relationship of each topic to the overall thesis of the paper.

For tips on making a reverse outline, see our handout on organization .

Color code your paper

You will need three highlighters or colored pencils for this exercise. Use one color to highlight general assertions. These will typically be the topic sentences in your paper. Next, use another color to highlight the specific evidence you provide for each assertion (including quotations, paraphrased or summarized material, statistics, examples, and your own ideas). Lastly, use another color to highlight analysis of your evidence. Which assertions are key to your overall argument? Which ones are especially contestable? How much evidence do you have for each assertion? How much analysis? In general, you should have at least as much analysis as you do evidence, or your paper runs the risk of being more summary than argument. The more controversial an assertion is, the more evidence you may need to provide in order to persuade your reader.

Play devil’s advocate, act like a child, or doubt everything

This technique may be easiest to use with a partner. Ask your friend to take on one of the roles above, then read your paper aloud to them. After each section, pause and let your friend interrogate you. If your friend is playing devil’s advocate, they will always take the opposing viewpoint and force you to keep defending yourself. If your friend is acting like a child, they will question every sentence, even seemingly self-explanatory ones. If your friend is a doubter, they won’t believe anything you say. Justifying your position verbally or explaining yourself will force you to strengthen the evidence in your paper. If you already have enough evidence but haven’t connected it clearly enough to your main argument, explaining to your friend how the evidence is relevant or what it proves may help you to do so.

Common questions and additional resources

- I have a general topic in mind; how can I develop it so I’ll know what evidence I need? And how can I get ideas for more evidence? See our handout on brainstorming .

- Who can help me find evidence on my topic? Check out UNC Libraries .

- I’m writing for a specific purpose; how can I tell what kind of evidence my audience wants? See our handouts on audience , writing for specific disciplines , and particular writing assignments .

- How should I read materials to gather evidence? See our handout on reading to write .

- How can I make a good argument? Check out our handouts on argument and thesis statements .

- How do I tell if my paragraphs and my paper are well-organized? Review our handouts on paragraph development , transitions , and reorganizing drafts .

- How do I quote my sources and incorporate those quotes into my text? Our handouts on quotations and avoiding plagiarism offer useful tips.

- How do I cite my evidence? See the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

- I think that I’m giving evidence, but my instructor says I’m using too much summary. How can I tell? Check out our handout on using summary wisely.

- I want to use personal experience as evidence, but can I say “I”? We have a handout on when to use “I.”

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Lunsford, Andrea A., and John J. Ruszkiewicz. 2016. Everything’s an Argument , 7th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Miller, Richard E., and Kurt Spellmeyer. 2016. The New Humanities Reader , 5th ed. Boston: Cengage.

University of Maryland. 2019. “Research Using Primary Sources.” Research Guides. Last updated October 28, 2019. https://lib.guides.umd.edu/researchusingprimarysources .

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Write Clearly: Using Evidence Effectively

How do i select evidence, how do i analyze evidence.

- Incorporating Evidence

Ask Us: Chat, email, visit or call

Get assistance

The library offers a range of helpful services. All of our appointments are free of charge and confidential.

- Book an appointment

Much of how to use evidence is about finding a clear and logical relation between the evidence you use and your claim. For example, if you are asked to write a paper on the effects of pollution on watersheds, you would not use a story your grandfather told you about the river he used to swim in that is now polluted. You would look for peer-reviewed journal articles by experts on the subject.

Once you have found the appropriate type of evidence, it is important to select the evidence that supports your specific claim. For example, if you are writing a psychology paper on the role of emotions in decision-making, you would look for psychology journal articles that connect these two elements.

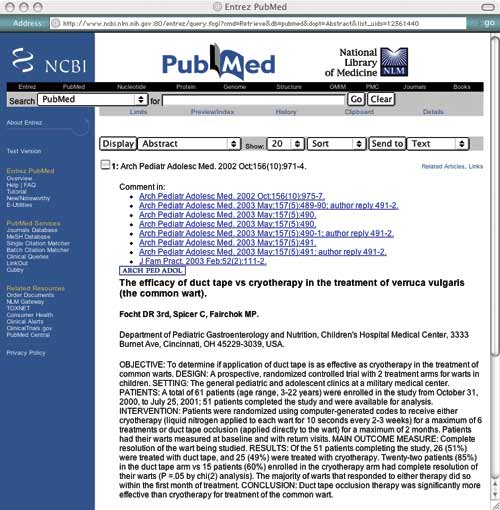

For example:

By referencing the study in the first example and supplying textual evidence in the second, the initial statement in the paragraph moves from opinion to supported argument; however, you must still analyze your evidence.

Once you have selected your evidence it is important to tell you reader why the evidence supports your claim. Evidence does not speak for itself: some readers may draw different conclusions from your evidence, or may not understand the relation between your evidence and your claim. It is up to you to walk your reader through the significance of the evidence to your claim and your larger argument. In short, you need a reason why the evidence supports the claim – you need to analyze the evidence.

Some questions you could consider are:

- Why is this evidence interesting or effective?

- What are the consequences or implications of this evidence?

- Why is this information important?

- How has it been important to my paper or to the field I am studying?

- How is this idea related to my thesis?

- This evidence points to a result of an experiment or study, can I explain why these results are important or what caused them?

- Can I give an example to illustrate this point?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the evidence presented?

If we look to our first examples, they may look like this once we add analysis to our evidence:

- Emotions play a larger role in rational decision-making than most us think ( claim ). Subjects deciding to wear a seatbelt demonstrated an activity in the ventromedial frontal lobe, the part of the brain that governs emotion (Shibata 2001) ( evidence ). This suggests that people making rational decisions, even when performing naturalized tasks such as putting on a seatbelt, rely on their emotions ( analysis ).

Or, when we look at the example of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde:

- The physical descriptions of the laboratory and the main house, in Dr Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, metaphorically point to the gothic elements in the novel ( claim ). The main house had "a great air of wealth and comfort" (13), while the laboratory door "which was equipped with neither bell nor knocker, was blistered and distained" (3) ( evidence ). The comforting and welcoming look of the main house is in sharp contrast to the door of the laboratory, which does not even have a bell to invite people in. The laboratory door is eerie and gothic highlighting the abnormal and mystical events that take place behind it ( analysis ).

- << Previous: Start Here

- Next: Incorporating Evidence >>

- Last Updated: Jul 12, 2022 1:00 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uoguelph.ca/UseEvidenceEffectively

Suggest an edit to this guide

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

- Joyner Library

- Laupus Health Sciences Library

- Music Library

- Digital Collections

- Special Collections

- North Carolina Collection

- Teaching Resources

- The ScholarShip Institutional Repository

- Country Doctor Museum

Evidence-Based Practice for Nursing: Evaluating the Evidence

- What is Evidence-Based Practice?

- Asking the Clinical Question

- Finding Evidence

- Evaluating the Evidence

- Articles, Books & Web Resources on EBN

Evaluating Evidence: Questions to Ask When Reading a Research Article or Report

For guidance on the process of reading a research book or an article, look at Paul N. Edward's paper, How to Read a Book (2014) . When reading an article, report, or other summary of a research study, there are two principle questions to keep in mind:

1. Is this relevant to my patient or the problem?

- Once you begin reading an article, you may find that the study population isn't representative of the patient or problem you are treating or addressing. Research abstracts alone do not always make this apparent.

- You may also find that while a study population or problem matches that of your patient, the study did not focus on an aspect of the problem you are interested in. E.g. You may find that a study looks at oral administration of an antibiotic before a surgical procedure, but doesn't address the timing of the administration of the antibiotic.

- The question of relevance is primary when assessing an article--if the article or report is not relevant, then the validity of the article won't matter (Slawson & Shaughnessy, 1997).

2. Is the evidence in this study valid?

- Validity is the extent to which the methods and conclusions of a study accurately reflect or represent the truth. Validity in a research article or report has two parts: 1) Internal validity--i.e. do the results of the study mean what they are presented as meaning? e.g. were bias and/or confounding factors present? ; and 2) External validity--i.e. are the study results generalizable? e.g. can the results be applied outside of the study setting and population(s) ?

- Determining validity can be a complex and nuanced task, but there are a few criteria and questions that can be used to assist in determining research validity. The set of questions, as well as an overview of levels of evidence, are below.

For a checklist that can help you evaluate a research article or report, use our checklist for Critically Evaluating a Research Article

- How to Critically Evaluate a Research Article

How to Read a Paper--Assessing the Value of Medical Research

Evaluating the evidence from medical studies can be a complex process, involving an understanding of study methodologies, reliability and validity, as well as how these apply to specific study types. While this can seem daunting, in a series of articles by Trisha Greenhalgh from BMJ, the author introduces the methods of evaluating the evidence from medical studies, in language that is understandable even for non-experts. Although these articles date from 1997, the methods the author describes remain relevant. Use the links below to access the articles.

- How to read a paper: Getting your bearings (deciding what the paper is about) Not all published research is worth considering. This provides an outline of how to decide whether or not you should consider a research paper. more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997b). How to read a paper. Getting your bearings (deciding what the paper is about). BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7102), 243–246.

- Assessing the methodological quality of published papers This article discusses how to assess the methodological validity of recent research, using five questions that should be addressed before applying recent research findings to your practice. more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997a). Assessing the methodological quality of published papers. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7103), 305–308.

- How to read a paper. Statistics for the non-statistician. I: Different types of data need different statistical tests This article and the next present the basics for assessing the statistical validity of medical research. The two articles are intended for readers who struggle with statistics more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997f). How to read a paper. Statistics for the non-statistician. I: Different types of data need different statistical tests. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7104), 364–366.

- How to read a paper: Statistics for the non-statistician II: "Significant" relations and their pitfalls The second article on evaluating the statistical validity of a research article. more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997). Education and debate. how to read a paper: Statistics for the non-statistician. II: "significant" relations and their pitfalls. BMJ: British Medical Journal (International Edition), 315(7105), 422-425. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7105.422

- How to read a paper. Papers that report drug trials more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997d). How to read a paper. Papers that report drug trials. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7106), 480–483.

- How to read a paper. Papers that report diagnostic or screening tests more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997c). How to read a paper. Papers that report diagnostic or screening tests. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7107), 540–543.

- How to read a paper. Papers that tell you what things cost (economic analyses) more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997e). How to read a paper. Papers that tell you what things cost (economic analyses). BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7108), 596–599.

- Papers that summarise other papers (systematic reviews and meta-analyses) more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997i). Papers that summarise other papers (systematic reviews and meta-analyses). BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7109), 672–675.

- How to read a paper: Papers that go beyond numbers (qualitative research) A set of questions that could be used to analyze the validity of qualitative research more... less... Greenhalgh, T., & Taylor, R. (1997). Papers that go beyond numbers (qualitative research). BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7110), 740–743.

Levels of Evidence

In some journals, you will see a 'level of evidence' assigned to a research article. Levels of evidence are assigned to studies based on the methodological quality of their design, validity, and applicability to patient care. The combination of these attributes gives the level of evidence for a study. Many systems for assigning levels of evidence exist. A frequently used system in medicine is from the Oxford Center for Evidence-Based Medicine . In nursing, the system for assigning levels of evidence is often from Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt's 2011 book, Evidence-based Practice in Nursing and Healthcare: A Guide to Best Practice . The Levels of Evidence below are adapted from Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt's (2011) model.

Uses of Levels of Evidence : Levels of evidence from one or more studies provide the "grade (or strength) of recommendation" for a particular treatment, test, or practice. Levels of evidence are reported for studies published in some medical and nursing journals. Levels of Evidence are most visible in Practice Guidelines, where the level of evidence is used to indicate how strong a recommendation for a particular practice is. This allows health care professionals to quickly ascertain the weight or importance of the recommendation in any given guideline. In some cases, levels of evidence in guidelines are accompanied by a Strength of Recommendation.

About Levels of Evidence and the Hierarchy of Evidence : While Levels of Evidence correlate roughly with the hierarchy of evidence (discussed elsewhere on this page), levels of evidence don't always match the categories from the Hierarchy of Evidence, reflecting the fact that study design alone doesn't guarantee good evidence. For example, the systematic review or meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are at the top of the evidence pyramid and are typically assigned the highest level of evidence, due to the fact that the study design reduces the probability of bias ( Melnyk , 2011), whereas the weakest level of evidence is the opinion from authorities and/or reports of expert committees. However, a systematic review may report very weak evidence for a particular practice and therefore the level of evidence behind a recommendation may be lower than the position of the study type on the Pyramid/Hierarchy of Evidence.

About Levels of Evidence and Strength of Recommendation : The fact that a study is located lower on the Hierarchy of Evidence does not necessarily mean that the strength of recommendation made from that and other studies is low--if evidence is consistent across studies on a topic and/or very compelling, strong recommendations can be made from evidence found in studies with lower levels of evidence, and study types located at the bottom of the Hierarchy of Evidence. In other words, strong recommendations can be made from lower levels of evidence.

For example: a case series observed in 1961 in which two physicians who noted a high incidence (approximately 20%) of children born with birth defects to mothers taking thalidomide resulted in very strong recommendations against the prescription and eventually, manufacture and marketing of thalidomide. In other words, as a result of the case series, a strong recommendation was made from a study that was in one of the lowest positions on the hierarchy of evidence.

Hierarchy of Evidence for Quantitative Questions

The pyramid below represents the hierarchy of evidence, which illustrates the strength of study types; the higher the study type on the pyramid, the more likely it is that the research is valid. The pyramid is meant to assist researchers in prioritizing studies they have located to answer a clinical or practice question.

For clinical questions, you should try to find articles with the highest quality of evidence. Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses are considered the highest quality of evidence for clinical decision-making and should be used above other study types, whenever available, provided the Systematic Review or Meta-Analysis is fairly recent.

As you move up the pyramid, fewer studies are available, because the study designs become increasingly more expensive for researchers to perform. It is important to recognize that high levels of evidence may not exist for your clinical question, due to both costs of the research and the type of question you have. If the highest levels of study design from the evidence pyramid are unavailable for your question, you'll need to move down the pyramid.

While the pyramid of evidence can be helpful, individual studies--no matter the study type--must be assessed to determine the validity.

Hierarchy of Evidence for Qualitative Studies

Qualitative studies are not included in the Hierarchy of Evidence above. Since qualitative studies provide valuable evidence about patients' experiences and values, qualitative studies are important--even critically necessary--for Evidence-Based Nursing. Just like quantitative studies, qualitative studies are not all created equal. The pyramid below shows a hierarchy of evidence for qualitative studies.

Adapted from Daly et al. (2007)

Help with Research Terms & Study Types: Cut through the Jargon!

- CEBM Glossary

- Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine|Toronto

- Cochrane Collaboration Glossary

- Qualitative Research Terms (NHS Trust)

- << Previous: Finding Evidence

- Next: Articles, Books & Web Resources on EBN >>

- Last Updated: Jan 12, 2024 10:03 AM

- URL: https://libguides.ecu.edu/ebn

- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code

Gen ed writes, writing across the disciplines at harvard college.

- Evidence and Analysis

Why It Matters

An assignment prompt’s guidance on evidence and analysis sets parameters for the content and form of a writing assignment: What kinds of sources should you be working with? Where should you find those sources? How should you be working with them?

More on "Evidence and Analysis"

The evidence and analysis you're asked to use (or not use) for a writing assignment often reflect the genre and size of the assignment at hand. With any writing assignment prompt, it’s important to step back and make sure you’re clear about the scope of evidence and analysis you’ll be working with. For example:

In terms of evidence,

- what kinds of evidence should be used (peer-reviewed articles versus op-ed pieces),

- which evidence in particular and how much (3–5 readings from class versus independent research), and

- why (because op-ed pieces capture a kind of public discourse better than peer-reviewed articles, or because 3–5 readings from class is manageable for a 4-page essay and also reinforces the readings assigned for the course, etc.).

In terms of analysis,

- is the assignment asking you to make an argument? If so, what kind of argument? (e.g., a rhetorical analysis weighing the pros and cons of a think piece, or a policy memo making normative claims about recommended courses of action, or a test a theory essay assessing the applicability of a framework to real-world cases?)

- if not, what is it asking you to do with evidence? (e.g., summarize a source’s argument, or draft a research question based on an annotated bibliography or data set)

- why? (because it’s important to establish other thinkers’ positions accurately before taking your own position, or because asking questions before moving on to a thesis or conclusion will make the research process more compelling).

What It Looks Like

- Science & Technology in Society

- Ethics & Civics

- Histories, Societies, Individuals

- Aesthetics & Culture

STEP 1: PROPOSAL WITH ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Length: 250–500 words, not including annotated bibliography. The annotated bibliography must have at least 5 different references from outside the course and 5 different references from the syllabus.

Source requirements:

- Minimum 5 different references from outside the course (at least 3 must be peer-reviewed scholarly sources) [1]

- Minimum 5 different references from Gen Ed 1093 reading assignments listed on the syllabus; lectures do not count toward the reference requirement, and Reimagining Global Health will only count as one reference [2]

- Citation format either AAA or APA [3] , consistent throughout the paper

- Careful attention to academic integrity and appropriate citation practices

- The annotated bibliography does not count toward your word count, but in-text citations do. [4]

__________ [1] Explicit guidance about what kinds of sources and how many sources to include [2] Clarification about what does / doesn't count toward the required number of sources [3] Clear guidance about citation format [4] Clarification about what does / doesn't count toward the required word count

Adapted from Gen Ed 1093 : Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Cares? Reimagining Global Health | Fall 2020

On p 13 of Why not Socialism?, G. A. Cohen states that the principle of “socialist equality of opportunity” is a principle of justice. What is the principle of “socialist equality of opportunity,” why does Cohen think it is a principle of justice, why does he think it is a desirable principle, and why does he think it is feasible? Which part of his argument do you think is most vulnerable to objections? Formulate some objections and explore how Cohen could respond. Do you think the objections succeed, or is Cohen’s view correct?

Proceed as follows: [1] State what socialist equality of opportunity is, by way of contrast with the two other kinds of equality of opportunity identified by Cohen. Explain why Cohen thinks, as a matter of justice, socialist equality of opportunity is preferable to the other two, and explain why an additional principle of community is needed to supplement that principle of justice. Then assess whether Cohen offers additional reasons (beyond the superiority of his principle over the alternatives) as to why equality and community are desirable, both for the camping trip and society at large. In a next step briefly summarize what he says about the feasibility of the principle. Devote about two thirds of your discussion to the tasks sketched so far, and then devote the remaining third to your exploration of the objections to parts of Cohen’s argument and an exploration of their success.

General Guidance

In section, your TF will discuss general guidelines to writing a philosophy paper. [2] Please also consult the “Advice on Written Assignments” posted on Canvas before writing the paper. Recall that you will write three papers in this course. The assignments get progressively more demanding. In the first paper, the emphasis is on reconstructing arguments, allowing you to develop the skill of logical reconstruction rather than narrative summary of a text. …The second paper goes beyond reconstruction, putting more emphasis on the critically evaluating arguments. The third paper gives you an opportunity to develop a well-reasoned defense in support of your own view regarding one of the central issues of the class. [3]

__________ [1] Students are given clear advice about how to use evidence differently at different points in their assignment. [2] Students are assured that they will learn guidelines for working with evidence and analysis in a more disciplinary kind of writing (with which many of them will likely be unfamiliar). [3] The move from “reconstruction” to “critically evaluating” to “well-reasoned defense” signals a scaffolded development of ways to work with evidence, along with reasons why students are being are being asked to work with evidence in a certain way for this first essay, viz., “ to develop the skill of logical reconstruction."

Adapted from Gen Ed 1121 : Economic Justice | Spring 2020 Professor Mathias Risse

Research Requirements

All projects, regardless of which modality you adopt, will need to include [1]

- an annotated bibliography that includes at least 5 scholarly sources. These sources can include scholarly articles, books, or websites. For a website, please check with the TFs to confirm the viability of it as a source. [2] There are legitimately scholarly websites, but many content-related sites are not scholarly.

- a 1-page artist statement.

See “How tos_Annotated Bibliography_your Artist Statement” for specific instructions for both the annotated bibliography and the artist statement. [3]

__________ [1] Explicit guidance about what kinds of sources and how many to include [2] Advice on how to get help evaluating whether a source counts as viable evidence [3] Additional resources (tied to guidelines and process) that help explain the roles of evidence and analysis in the assignment

Adapted from Gen Ed 1099 : Pyramid Schemes: What Can Ancient Egyptian Civilization Teach Us? Professor Peter der Manuelian

Introduce yourself to another student in the class by making a virtual mixtape for them. ⋮ Your tape should contain the following (in any order): [1]

- The greeting on the Golden Record that best describes you (or record your own)

- One piece of music included on the Golden Record

- Your personal summer hit of 2020

- A “found sound” (recorded in your environment that seems characteristic or interesting)

- A piece of music that best describes you

- Your favorite piece/song by a musician outside the US/Canada

Use these guidelines as a starting point for your mixtape. Feel free to get creative. The mixtape should say something important about YOU. (There will be no written text accompanying your file. The sounds have to say it all.) [2]

__________ [1] Students are given a clear checklist of what to include in their assignment. [2] In this assignment, the evidence makes its argument through curation, rather than additional written analysis. Making sure students understand that particular relationship of evidence to analysis ahead of time frames the assignment’s purpose and genre.

Adapted from Gen Ed 1006 : Music from Earth | Fall 2020 Professor Alex Rehding

- DIY Guides for Analytical Writing Assignments

- Types of Assignments

- Style and Conventions

- Specific Guidelines

- Advice on Process

- Receiving Feedback

Assignment Decoder

- What is the best evidence and how to find it

Why is research evidence better than expert opinion alone?

In a broad sense, research evidence can be any systematic observation in order to establish facts and reach conclusions. Anything not fulfilling this definition is typically classified as “expert opinion”, the basis of which includes experience with patients, an understanding of biology, knowledge of pre-clinical research, as well as of the results of studies. Using expert opinion as the only basis to make decisions has proved problematic because in practice doctors often introduce new treatments too quickly before they have been shown to work, or they are too slow to introduce proven treatments.

However, clinical experience is key to interpret and apply research evidence into practice, and to formulate recommendations, for instance in the context of clinical guidelines. In other words, research evidence is necessary but not sufficient to make good health decisions.

Which studies are more reliable?

Not all evidence is equally reliable.

Any study design, qualitative or quantitative, where data is collected from individuals or groups of people is usually called a primary study. There are many types of primary study designs, but for each type of health question there is one that provides more reliable information.

For treatment decisions, there is consensus that the most reliable primary study is the randomised controlled trial (RCT). In this type of study, patients are randomly assigned to have either the treatment being tested or a comparison treatment (sometimes called the control treatment). Random really means random. The decision to put someone into one group or another is made like tossing a coin: heads they go into one group, tails they go into the other.

The control treatment might be a different type of treatment or a dummy treatment that shouldn't have any effect (a placebo). Researchers then compare the effects of the different treatments.

Large randomised trials are expensive and take time. In addition sometimes it may be unethical to undertake a study in which some people were randomly assigned not to have a treatment. For example, it wouldn't be right to give oxygen to some children having an asthma attack and not give it to others. In cases like this, other primary study designs may be the best choice.

Laboratory studies are another type of study. Newspapers often have stories of studies showing how a drug cured cancer in mice. But just because a treatment works for animals in laboratory experiments, this doesn't mean it will work for humans. In fact, most drugs that have been shown to cure cancer in mice do not work for people.

Very rarely we cannot base our health decisions on the results of studies. Sometimes the research hasn't been done because doctors are used to treating a condition in a way that seems to work. This is often true of treatments for broken bones and operations. But just because there's no research for a treatment doesn't mean it doesn't work. It just means that no one can say for sure.

Why we shouldn’t read studies

An enormous amount of effort is required to be able to identify and summarise everything we know with regard to any given health intervention. The amount of data has soared dramatically. A conservative estimation is there are more than 35,000 medical journals and almost 20 million research articles published every year. On the other hand, up to half of existing data might be unpublished.

How can anyone keep up with all this? And how can you tell if the research is good or not? Each primary study is only one piece of a jigsaw that may take years to finish. Rarely does any one piece of research answer either a doctor's, or a patient's questions.

Even though reading large numbers of studies is impractical, high-quality primary studies, especially RCTs, constitute the foundations of what we know, and they are the best way of advancing the knowledge. Any effort to support or promote the conduct of sound, transparent, and independent trials that are fully and clearly published is worth endorsing. A prominent project in this regard is the All trials initiative.

Why we should read systematic reviews

Most of the time a single study doesn't tell us enough. The best answers are found by combining the results of many studies.

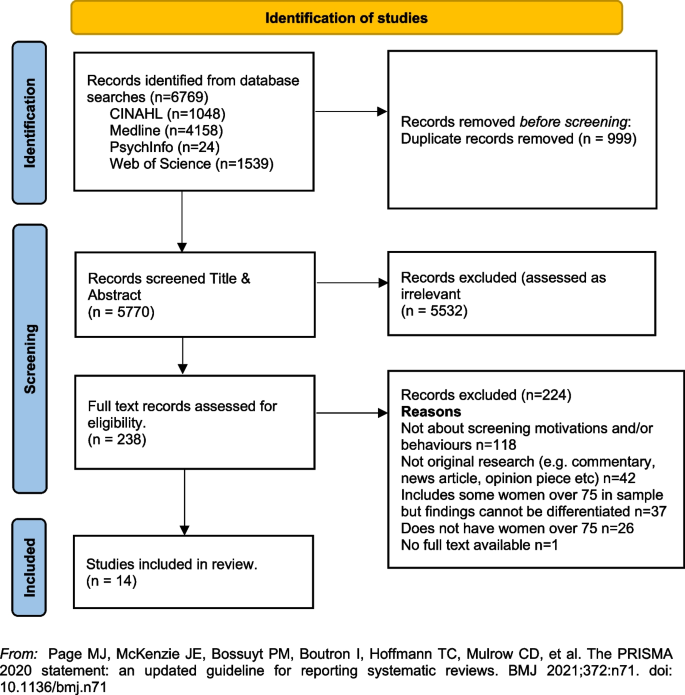

A systematic review is a type of research that looks at the results from all of the good-quality studies. It puts together the results of these individual studies into one summary. This gives an estimate of a treatment's risks and benefits. Sometimes these reviews include a statistical analysis, called a meta-analysis , which combines the results of several studies to give a treatment effect.

Systematic reviews are increasingly being used for decision making because they reduce the probability of being misled by looking at one piece of the jigsaw. By being systematic they are also more transparent, and have become the gold standard approach to synthesise the ever-expanding and conflicting biomedical literature.

Systematic reviews are not fool proof. Their findings are only as good as the studies that they include and the methods they employ. But the best reviews clearly state whether the studies they include are good quality or not.

Three reasons why we shouldn’t read (most) systematic reviews

Firstly, systematic reviews have proliferated over time. From 11 per day in 2010, they skyrocketed up to 40 per day or more in 2015.[1][2] Some have described this production as having reached epidemic proportions where the large majority of produced systematic reviews and meta-analyses are unnecessary, misleading, and/or conflicted.[3][4] So, finding more than one systematic review for a question is the rule more than the exception, and it is not unusual to find several dozen for the hottest questions.

Second, most systematic reviews address a narrow question. It is difficult to put them in the context of all of the available alternatives for an individual case. Reading multiple reviews to assess all of the alternatives is impractical, even more if we consider they are typically difficult to read for the average clinician, who will need to solve several questions each day.[5]

Third, systematic reviews do not tell you what to do, or what is advisable for a given patient or situation. Indeed, good systematic reviews explicitly avoid making recommendations.

So, even though systematic reviews play a key role in any evidence-based decision-making process, most of them are low-quality or outdated, and they rarely provide all the information needed to make decisions in the real world.

How to find the best available evidence?

Considering the massive amount of information available, we can quickly discard periodically reviewing our favourite journals as a means of sourcing the best available evidence.

The traditional approach to search for evidence has been using major databases, such as PubMed or EMBASE . These constitute comprehensive sources including millions of relevant, but also irrelevant articles. Even though in the past they were the preferred approach to searching for evidence, information overload has made them impractical, and most clinicians would fail to find the best available evidence in this way, however hard they tried.

Another popular approach is simply searching in Google. Unfortunately, because of its lack of transparency, Google is not a reliable way to filter current best evidence from unsubstantiated or non-scientifically supervised sources.[6]

Three alternatives to access the best evidence

Alternative 1 - Pick the best systematic review Mastering the art of identifying, appraising, and applying high-quality systematic reviews into practice can be very rewarding. It is not easy, but once mastered it gives a view of the bigger picture: of what is known, and what is not known.

The best single source of highest-quality systematic reviews is produced by an international organisation called the Cochrane Collaboration, named after a well-known researcher.[4] They can be accessed at The Cochrane Library .

Unfortunately, Cochrane reviews do not cover all of the existing questions and they are not always up to date. Also, there might be non-Cochrane reviews out-performing Cochrane reviews.

There are many resources that facilitate access to systematic reviews (and other resources), such as Trip database , PubMed Health , ACCESSSS , or Epistemonikos (the Cochrane Collaboration maintains a comprehensive list of these resources).

Epistemonikos database is innovative both in simultaneously searching multiple resources and in indexing and interlinking relevant evidence. For example, Epistemonikos connects systematic reviews and their included studies, and thus allows clustering of systematic reviews based on the primary studies they have in common. Epistemonikos is also unique in offering an appreciable multilingual user interface, multilingual search, and translation of abstracts in more than nine languages.[6] This database includes several tools to compare systematic reviews, including the matrix of evidence, a dynamic table showing all of the systematic reviews, and the primary studies included in those reviews.

Additionally, Epistemonikos partnered with Cochrane, and during 2017 a combined search in both the Cochrane Library and Epistemonikos was released.

Alternative 2 - Read trustworthy guidelines Although systematic reviews can provide a synthesis of the benefits and harms of the interventions, they do not integrate these factors with patients’ values and preferences or resource considerations to provide a suggested course of action. Also, to fully address the questions, clinicians would need to integrate the information of several systematic reviews covering all the relevant alternatives and outcomes. Most clinicians will likely prefer guidance rather than interpreting systematic reviews themselves.

Trustworthy guidelines, especially if developed with high standards, such as the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation ( GRADE ) approach, offer systematic and transparent guidance in moving from evidence to recommendations.[7]

Many online guideline websites promote themselves as “evidence based”, but few have explicit links to research findings.[8] If they don’t have in-line references to relevant research findings, dismiss them. If they have, you can judge the strength of the commitment to evidence to support inference, checking whether statements are based on high-quality versus low-quality evidence using alternative 1 explained above.

Unfortunately, most guidelines have serious limitations or are outdated.[9][10] The exercise of locating and appraising the best guideline is time consuming. This is particularly challenging for generalists addressing questions from different conditions or diseases.

Alternative 3 - Use point-of-care tools Point-of-care tools, such as BMJ Best Practice, have been developed as a response to the genuine need to summarise the ever-expanding biomedical literature on an ever-increasing number of alternatives in order to make evidence-based decisions. In this competitive market, the more successful products have been those delivering innovative, user-friendly interfaces that improve the retrieval, synthesis, organisation, and application of evidence-based content in many different areas of clinical practice.

However, the same impossibility in catching up with new evidence without compromising quality that affects guidelines also affects point-of-care tools. Clinicians should become familiar with the point-of-care information resource they want or can access, and examine the in-line references to relevant research findings. Clinicians can easily judge the strength of the commitment to evidence checking whether statements are based on high-quality versus low-quality evidence using alternative 1 explained above. Comprehensiveness, use of GRADE approach, and independence are other characteristics to bear in mind when selecting among point-of-care information summaries.

A comprehensive list of these resources can be found in a study by Kwag et al .

Finding the best available evidence is more challenging than it was in the dawn of the evidence-based movement, and the main cause is the exponential growth of evidence-based information, in any of the flavours described above.

However, with a little bit of patience and practice, the busy clinician will discover evidence-based practice is far easier than it was 5 or 10 years ago. We are entering a stage where information is flowing between the different systems, technology is being harnessed for good, and the different players are starting to generate alliances.

The early adopters will surely enjoy the first experiments of living systematic reviews (high-quality, up-to-date online summaries of health research that are updated as new research becomes available), living guidelines, and rapid reviews tied to rapid recommendations, just to mention a few. [13][14][15]

It is unlikely that the picture of countless low-quality studies and reviews will change in the foreseeable future. However, it would not be a surprise if, in 3 to 5 years, separating the wheat from the chaff becomes trivial. Maybe the promise of evidence-based medicine of more effective, safer medical intervention resulting in better health outcomes for patients could be fulfilled.

Author: Gabriel Rada

Competing interests: Gabriel Rada is the co-founder and chairman of Epistemonikos database, part of the team that founded and maintains PDQ-Evidence, and an editor of the Cochrane Collaboration.

Related Blogs

Living Systematic Reviews: towards real-time evidence for health-care decision making

- Bastian H, Glasziou P, Chalmers I. Seventy-five trials and eleven systematic reviews a day: how will we ever keep up? PLoS Med. 2010 Sep 21;7(9):e1000326. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000326

- Epistemonikos database [filter= systematic review; year=2015]. A Free, Relational, Collaborative, Multilingual Database of Health Evidence. https://www.epistemonikos.org/en/search?&q=*&classification=systematic-review&year_start=2015&year_end=2015&fl=14542 Accessed 5 Jan 2017.

- Ioannidis JP. The Mass Production of Redundant, Misleading, and Conflicted Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses. Milbank Q. 2016 Sep;94(3):485-514. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12210.

- Page MJ, Shamseer L, Altman DG, et al. Epidemiology and reporting characteristics of systematic reviews of biomedical research: a cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2016;13(5):e1002028.

- Del Fiol G, Workman TE, Gorman PN. Clinical questions raised by clinicians at the point of care: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2014 May;174(5):710-8. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.368.

- Agoritsas T, Vandvik P, Neumann I, Rochwerg B, Jaeschke R, Hayward R, et al. Chapter 5: finding current best evidence. In: Users' guides to the medical literature: a manual for evidence-based clinical practice. Chicago: MacGraw-Hill, 2014.

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924-926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347

- Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017

- Alonso-Coello P, Irfan A, Solà I, Gich I, Delgado-Noguera M, Rigau D, Tort S, Bonfill X, Burgers J, Schunemann H. The quality of clinical practice guidelines over the last two decades: a systematic review of guideline appraisal studies. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010 Dec;19(6):e58. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2010.042077

- Martínez García L, Sanabria AJ, García Alvarez E, Trujillo-Martín MM, Etxeandia-Ikobaltzeta I, Kotzeva A, Rigau D, Louro-González A, Barajas-Nava L, Díaz Del Campo P, Estrada MD, Solà I, Gracia J, Salcedo-Fernandez F, Lawson J, Haynes RB, Alonso-Coello P; Updating Guidelines Working Group. The validity of recommendations from clinical guidelines: a survival analysis. CMAJ. 2014 Nov 4;186(16):1211-9. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.140547

- Kwag KH, González-Lorenzo M, Banzi R, Bonovas S, Moja L. Providing Doctors With High-Quality Information: An Updated Evaluation of Web-Based Point-of-Care Information Summaries. J Med Internet Res. 2016 Jan 19;18(1):e15. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5234

- Banzi R, Cinquini M, Liberati A, Moschetti I, Pecoraro V, Tagliabue L, Moja L. Speed of updating online evidence based point of care summaries: prospective cohort analysis. BMJ. 2011 Sep 23;343:d5856. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5856

- Elliott JH, Turner T, Clavisi O, Thomas J, Higgins JP, Mavergames C, Gruen RL. Living systematic reviews: an emerging opportunity to narrow the evidence-practice gap. PLoS Med. 2014 Feb 18;11(2):e1001603. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001603

- Vandvik PO, Brandt L, Alonso-Coello P, Treweek S, Akl EA, Kristiansen A, Fog-Heen A, Agoritsas T, Montori VM, Guyatt G. Creating clinical practice guidelines we can trust, use, and share: a new era is imminent. Chest. 2013 Aug;144(2):381-9. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-0746

- Vandvik PO, Otto CM, Siemieniuk RA, Bagur R, Guyatt GH, Lytvyn L, Whitlock R, Vartdal T, Brieger D, Aertgeerts B, Price S, Foroutan F, Shapiro M, Mertz R, Spencer FA. Transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement for patients with severe, symptomatic, aortic stenosis at low to intermediate surgical risk: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ. 2016 Sep 28;354:i5085. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i5085

Discuss EBM

- What does evidence-based actually mean?

- Simply making evidence simple

- Six proposals for EBMs future

- Promoting informed healthcare choices by helping people assess treatment claims

- The blind leading the blind in the land of risk communication

- Transforming the communication of evidence for better health

- Clinical search, big data, and the hunt for meaning

- Living systematic reviews: towards real-time evidence for health-care decision making

- The rise of rapid reviews

- Evidence for the Brave New World on multimorbidity

- Genetics and personalised medicine: where’s the revolution?

- Policy, practice, and politics

- The straw men of integrative health and alternative medicine

- Where’s the evidence for teaching evidence-based medicine?

EBM Toolkit home

Learn, Practise, Discuss, Tools

Developing Deeper Analysis & Insights

Analysis is a central writing skill in academic writing. Essentially, analysis is what writers do with evidence to make meaning of it. While there are specific disciplinary types of analysis (e.g., rhetorical, discourse, close reading, etc.), most analysis involves zooming into evidence to understand how the specific parts work and how their specific function might relate to a larger whole. That is, we usually need to zoom into the details and then reflect on the larger picture. In this writing guide, we cover analysis basics briefly and then offer some strategies for deepening your analysis. Deepening your analysis means pushing your thinking further, developing a more insightful and interesting answer to the “so what?” question, and elevating your writing.

Analysis Basics

Questions to Ask of the Text:

- Is the evidence fully explained and contextualized? Where in the text/story does this evidence come from (briefly)? What do you think the literal meaning of the quote/evidence is and why? Why did you select this particular evidence?

- Are you selecting a long enough quote to work with and analyze? While over-quoting can be a problem, so too can under-quoting.

- Do you connect each piece of evidence explicitly to the claim or focus of the paper?

Strategies & Explanation

- Sometimes turning the focus of the paper into a question can really help someone to figure out how to work with evidence. All evidence should answer the question--the work of analysis is explaining how it answers the question.

- The goal of evidence in analytical writing is not just to prove that X exists or is true, but rather to show something interesting about it--to push ideas forward, to offer insights about a quote. To do this, sometimes having a full sentence for a quote helps--if a writer is only using single-word quotes, for example, they may struggle to make meaning out of it.

Deepening Analysis

Not all of these strategies work every time, but usually employing one of them is enough to really help elevate the ideas and intellectual work of a paper:

- Bring the very best point in each paragraph into the topic sentence. Often these sentences are at the very end of a paragraph in a solid draft. When you bring it to the front of the paragraph, you then need to read the paragraph with the new topic sentence and reflect on: what else can we say about this evidence? What else can it show us about your claim?

- Complicate the point by adding contrasting information, a different perspective, or by naming something that doesn’t fit. Often we’re taught that evidence needs to prove our thesis. But, richer ideas emerge from conflict, from difference, from complications. In a compare and contrast essay, this point is very easy to see--we get somewhere further when we consider how two things are different. In an analysis of a single text, we might look at a single piece of evidence and consider: how could this choice the writer made here be different? What other choices could the writer have made and why didn’t they? Sometimes naming what isn’t in the text can help emphasize the importance of a particular choice.

- Shift the focus question of the essay and ask the new question of each piece of evidence. For example, a student is looking at examples of language discrimination (their evidence) in order to make an argument that answers the question: what is language discrimination? Questions that are definitional (what is X? How does Y work? What is the problem here?) can make deeper analysis challenging. It’s tempting to simply say the equivalent of “Here is another example of language discrimination.” However, a strategy to help with this is to shift the question a little bit. So perhaps the paragraphs start by naming different instances of language discrimination, but the analysis then tackles questions like: what are the effects of language discrimination? Why is language discrimination so problematic in these cases? Who perpetuates language discrimination and how? In a paper like this, it’s unlikely you can answer all of those questions--but, selecting ONE shifted version of a question that each paragraph can answer, too, helps deepen the analysis and keeps the essay focused.

- Examine perspective--both the writer’s and those of others involved with the issue. You might reflect on your own perspectives as a unique audience/reader. For example, what is illuminated when you read this essay as an engineer? As a person of color? As a first-generation student at Cornell? As an economically privileged person? As a deeply religious Christian? In order to add perspective into the analysis, the writer has to name these perspectives with phrases like: As a religious undergraduate student, I understand X to mean… And then, try to explain how the specificity of your perspective illuminates a different reading or understanding of a term, point, or evidence. You can do this same move by reflecting on who the intended audience of a text is versus who else might be reading it--how does it affect different audiences differently? Might that be relevant to the analysis?

- Qualify claims and/or acknowledge limitations. Before college level writing and often in the media, there is a belief that qualifications and/or acknowledging the limitations of a point adds weakness to an argument. However, this actually adds depth, honesty, and nuance to ideas. It allows you to develop more thoughtful and more accurate ideas. The questions to ask to help foster this include: Is this always true? When is it not true? What else might complicate what you’ve said? Can we add nuance to this idea to make it more accurate? Qualifications involve words like: sometimes, may effect, often, in some cases, etc. These terms are not weak or to be avoided, they actually add accuracy and nuance.

A Link to a PDF Handout of this Writing Guide

Critically Analyzing Information Sources: Critical Appraisal and Analysis

- Critical Appraisal and Analysis

Initial Appraisal : Reviewing the source

- What are the author's credentials--institutional affiliation (where he or she works), educational background, past writings, or experience? Is the book or article written on a topic in the author's area of expertise? You can use the various Who's Who publications for the U.S. and other countries and for specific subjects and the biographical information located in the publication itself to help determine the author's affiliation and credentials.

- Has your instructor mentioned this author? Have you seen the author's name cited in other sources or bibliographies? Respected authors are cited frequently by other scholars. For this reason, always note those names that appear in many different sources.

- Is the author associated with a reputable institution or organization? What are the basic values or goals of the organization or institution?

B. Date of Publication

- When was the source published? This date is often located on the face of the title page below the name of the publisher. If it is not there, look for the copyright date on the reverse of the title page. On Web pages, the date of the last revision is usually at the bottom of the home page, sometimes every page.

- Is the source current or out-of-date for your topic? Topic areas of continuing and rapid development, such as the sciences, demand more current information. On the other hand, topics in the humanities often require material that was written many years ago. At the other extreme, some news sources on the Web now note the hour and minute that articles are posted on their site.

C. Edition or Revision

Is this a first edition of this publication or not? Further editions indicate a source has been revised and updated to reflect changes in knowledge, include omissions, and harmonize with its intended reader's needs. Also, many printings or editions may indicate that the work has become a standard source in the area and is reliable. If you are using a Web source, do the pages indicate revision dates?

D. Publisher

Note the publisher. If the source is published by a university press, it is likely to be scholarly. Although the fact that the publisher is reputable does not necessarily guarantee quality, it does show that the publisher may have high regard for the source being published.

E. Title of Journal

Is this a scholarly or a popular journal? This distinction is important because it indicates different levels of complexity in conveying ideas. If you need help in determining the type of journal, see Distinguishing Scholarly from Non-Scholarly Periodicals . Or you may wish to check your journal title in the latest edition of Katz's Magazines for Libraries (Olin Reference Z 6941 .K21, shelved at the reference desk) for a brief evaluative description.

Critical Analysis of the Content

Having made an initial appraisal, you should now examine the body of the source. Read the preface to determine the author's intentions for the book. Scan the table of contents and the index to get a broad overview of the material it covers. Note whether bibliographies are included. Read the chapters that specifically address your topic. Reading the article abstract and scanning the table of contents of a journal or magazine issue is also useful. As with books, the presence and quality of a bibliography at the end of the article may reflect the care with which the authors have prepared their work.

A. Intended Audience

What type of audience is the author addressing? Is the publication aimed at a specialized or a general audience? Is this source too elementary, too technical, too advanced, or just right for your needs?

B. Objective Reasoning

- Is the information covered fact, opinion, or propaganda? It is not always easy to separate fact from opinion. Facts can usually be verified; opinions, though they may be based on factual information, evolve from the interpretation of facts. Skilled writers can make you think their interpretations are facts.

- Does the information appear to be valid and well-researched, or is it questionable and unsupported by evidence? Assumptions should be reasonable. Note errors or omissions.

- Are the ideas and arguments advanced more or less in line with other works you have read on the same topic? The more radically an author departs from the views of others in the same field, the more carefully and critically you should scrutinize his or her ideas.

- Is the author's point of view objective and impartial? Is the language free of emotion-arousing words and bias?

C. Coverage

- Does the work update other sources, substantiate other materials you have read, or add new information? Does it extensively or marginally cover your topic? You should explore enough sources to obtain a variety of viewpoints.

- Is the material primary or secondary in nature? Primary sources are the raw material of the research process. Secondary sources are based on primary sources. For example, if you were researching Konrad Adenauer's role in rebuilding West Germany after World War II, Adenauer's own writings would be one of many primary sources available on this topic. Others might include relevant government documents and contemporary German newspaper articles. Scholars use this primary material to help generate historical interpretations--a secondary source. Books, encyclopedia articles, and scholarly journal articles about Adenauer's role are considered secondary sources. In the sciences, journal articles and conference proceedings written by experimenters reporting the results of their research are primary documents. Choose both primary and secondary sources when you have the opportunity.

D. Writing Style

Is the publication organized logically? Are the main points clearly presented? Do you find the text easy to read, or is it stilted or choppy? Is the author's argument repetitive?

E. Evaluative Reviews

- Locate critical reviews of books in a reviewing source , such as the Articles & Full Text , Book Review Index , Book Review Digest, and ProQuest Research Library . Is the review positive? Is the book under review considered a valuable contribution to the field? Does the reviewer mention other books that might be better? If so, locate these sources for more information on your topic.

- Do the various reviewers agree on the value or attributes of the book or has it aroused controversy among the critics?

- For Web sites, consider consulting this evaluation source from UC Berkeley .

Permissions Information

If you wish to use or adapt any or all of the content of this Guide go to Cornell Library's Research Guides Use Conditions to review our use permissions and our Creative Commons license.

- Next: Tips >>

- Last Updated: Apr 18, 2022 1:43 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.cornell.edu/critically_analyzing

- U.S. Locations

- UMGC Europe

- Learn Online

- Find Answers

- 855-655-8682

- Current Students

Online Guide to Writing and Research

The research process, explore more of umgc.

- Online Guide to Writing

Planning and Writing a Research Paper

Collect Evidence

The evidence you collect will shape your research paper tremendously. You will have to decide what evidence is appropriate for your audience, purpose, and thesis. To help you make this decision, consider what kind of appeal you are making to your audience—logical, emotional, or ethical. Click on the tabs below for more information.

- LOGOS OR LOGICAL APPEAL

- PATHOS OR EMOTIONAL APPEAL

- ETHOS OR ETHICAL APPEAL

You appeal to the reader’s intellect through factual or objective evidence.

You appeal to the reader’s feelings and their heart.

You appeal to the reader’s sense of justice, fair play or trust. The writer is seen to have authority regarding what they are writing about.

EXAMPLE OF A RESEARCH QUESTION AND ARGUMENT

Here is an example that describes research evidence to support an observable trend; this collection of evidence appeals to the readers’ logic and intelligence.

Research Question: What trends in research led to the computer industry segmentation that has occurred since the 1960s?

Argument Appealing to Logic and Intelligence: You might learn from early research that the initial phase of the US space program generated much interest in robotics and in programmable machines. That interest led to government funding for research in these areas during the 1960s. This evidence might suggest to you that the government’s role in financing research was instrumental in nurturing the fledgling computer industry of the 1960s. At the same time, you might learn that the government came into conflict with proponents of the growing industry in the 1970s by attempting to curtail domination by a single manufacturer through enforcement of the Sherman Antitrust Act. This evidence, in turn, will help you write about and explain the industry segmentation that has occurred since the 1960s, with its attendant competitive emphasis on constant improvement and innovation, realized in paradigm shifts such as those that occur in object-oriented programming.

Key Takeaways

- The evidence you collect will shape your research paper tremendously.

- To help you make this decision, consider what kind of appeal you are making to your audience—logical, emotional, or ethical.

Mailing Address: 3501 University Blvd. East, Adelphi, MD 20783 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License . © 2022 UMGC. All links to external sites were verified at the time of publication. UMGC is not responsible for the validity or integrity of information located at external sites.

Table of Contents: Online Guide to Writing

Chapter 1: College Writing

How Does College Writing Differ from Workplace Writing?

What Is College Writing?

Why So Much Emphasis on Writing?

Chapter 2: The Writing Process

Doing Exploratory Research

Getting from Notes to Your Draft

Introduction

Prewriting - Techniques to Get Started - Mining Your Intuition

Prewriting: Targeting Your Audience

Prewriting: Techniques to Get Started

Prewriting: Understanding Your Assignment

Rewriting: Being Your Own Critic

Rewriting: Creating a Revision Strategy

Rewriting: Getting Feedback

Rewriting: The Final Draft

Techniques to Get Started - Outlining

Techniques to Get Started - Using Systematic Techniques

Thesis Statement and Controlling Idea

Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Freewriting

Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Summarizing Your Ideas

Writing: Outlining What You Will Write

Chapter 3: Thinking Strategies

A Word About Style, Voice, and Tone