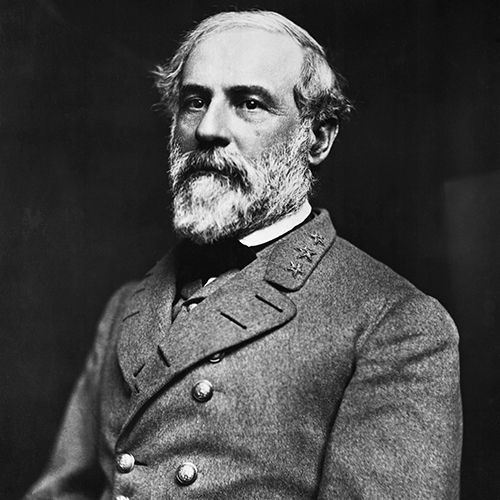

A Surprising New Bio of Robert E. Lee

A new book about about General Robert E. Lee offers support to those who argue for removing confederate monuments. Its author taught history at West Point, and he has nothing good to say about the man idolized by many in the South.

As a kid, Ty Seidule aspired to be a Southern gentleman like Robert E. Lee. His school text books were filled with praise, and wherever he went in Virginia Lee was a hero.

“I was bused across town in Alexandria from the white elementary school to the segregated all black school," he recalls, "and what was the name of that school? Robert E. Lee Elementary, named in 1961.”

Later he would attend Washington and Lee University, but while getting his PhD in history at Ohio State, Seidule learned some unsavory things about the General. Lee was, for example, a wealthy slaveholder who inherited a plantation from his in-laws.

“Where his father-in-law kept families together, he didn’t do that. He actually broke every family apart for a profit," Seidule says. "He ordered his enslaved people whipped and said to ‘lay it on well and pour brine water on their wounds,’ so he was seen by the enslaved people at Arlington as a cruel, cruel person.”

And when the nation prepared for Civil War, Seidule argues Lee showed himself to be a traitor by going against the Union.

“There were eight U.S. Army Colonels from Virginia. They were all West Point graduates. Seven of those colonels stay with the United States, and one and only one – Robert E. Lee – chooses to do that. He commits treason.”

During the war, he affirmed his racist beliefs.

“When he went north into Gettysburg, his army captured freed black people to bring them back for sale into Virginia, and at the Battle of the Crater in 1864 his soldiers slaughtered black prisoners of war.”

And at his alma mater, West Point, Lee was remembered that way.

“In the 19 th century, West Point banished Lee from their collective memory, because he was a traitor," Seidule explains. "He only came back in the 1930’s – the memory of him, things named after him – because it was a reaction to integration, in the 1950’s when the army started integrating, in the 1970’s when black cadets started coming in great numbers.”

During those times, he says, textbooks were rewritten to tell lies about the Civil War and Reconstruction.

“One, the war wasn’t fought over slavery, which is just a bald-faced lie. Two, that enslaved people were happy – that it was the best form of labor, which is another monstrous lie. Slavery featured the lash, rape, torture, murder, and the worst thing for enslaved families – breaking these families apart and selling them to the Deep South.”

When he served as a professor at West Point, Seidule was anxious to remind students of Lee’s true nature, but he got into big trouble for that.

“I couldn’t talk about these things openly in uniform. It was just too hot, particularly under the Trump administration I couldn’t talk about these subjects. It brought too much heat to the army and West Point.”

But now he’s teaching at Hamilton College in upstate New York – sharing his views through a book called Robert E. Lee and Me. In it he argues that taking down statues of Lee and other confederates does not erase history, but it does end commemoration.

“Commemoration is who we honor as a society, and who we honor should represent our values today, not those values of 1860 or 1930. We have an opportunity to do that now in a way that we haven’t in the past – to honor the diversity, the value and courage of real Americans.”

By doing that, he says, this country can finally confront slavery – what he calls the virus in our soil – and continue the progress made through the civil rights movement.

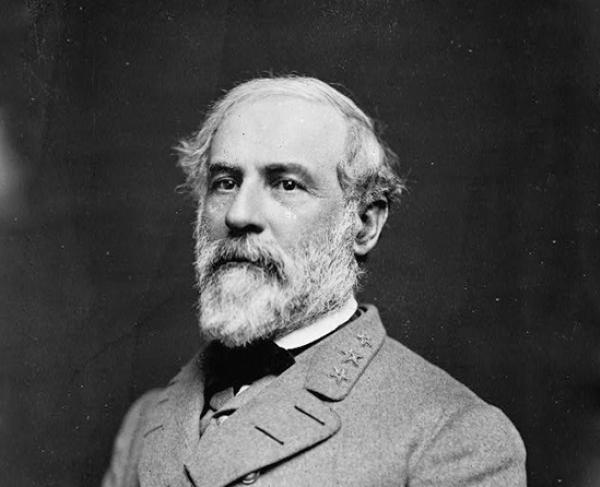

Robert E. Lee

Robert E. Lee was the leading Confederate general during the U.S. Civil War and has been venerated as a heroic figure in the American South.

We may earn commission from links on this page, but we only recommend products we back.

Who Was Robert E. Lee?

Robert E. Lee became military prominence during the U.S. Civil War, commanding his home state's armed forces and becoming general-in-chief of the Confederate troops toward the end of the conflict. Though the Union won the war, Lee earned renown as a military tactician for scoring several significant victories on the battlefield. He became president of Washington College and, renamed Washington and Lee University after he died in 1870.

Quick Facts

FULL NAME: Robert Edward Lee BORN: January 19, 1807 DIED: October 12, 1870 BIRTHPLACE: Stratford, Virginia SPOUSE: Mary Custis (1831-1870) CHILDREN: George Washington Custis, William “Rooney,” Robert Jr, Mary, Anne, Eleanor Agnes, and Mildred ASTROLOGICAL SIGN: Capricorn

Early Years

A Confederate general who led southern forces against the Union Army in the U.S. Civil War, Robert Edward Lee was born on Jan. 19, 1807, at his family home of Stratford Hall in northeastern Virginia.

Lee saw himself as an extension of his family's greatness. At 18, he enrolled at West Point Military Academy, where he put his drive and serious mind to work. He placed second in his graduating class after four spotless years without a demerit and wrapped up his studies with perfect scores in artillery, infantry, and cavalry.

Wife and Children

After graduating from West Point, Lee married Mary Custis, the great-granddaughter of Martha Washington (from her first marriage before meeting George Washington) in 1831. The couple wed on Mary Custis’s family plantation in Arlington, Virginia, just outside Washington, D.C. They would make the estate their primary home for the next 30 years. In 1857, Mary inherited the Arlington plantation outright following her father’s death. However, after the outbreak of the Civil War, Union troops occupied the plantation, and the federal government seized the land. In 1864, the government began constructing a new national cemetery to bury and honor the war’s military dead. After that, the former Custis/Lee home was transformed into one of the most hallowed places in American history— Arlington National Cemetery .

Together, they had seven children: four daughters (Mary, Annie, Agnes, and Mildred) and three sons (Custis, Rooney, and Rob) who followed their father to serve in the Confederate Army during the Civil War.

Early Military Career

While Mary and the children spent their lives on Mary's father's plantation, Lee stayed committed to his military obligations. His loyalties moved him around the country, from Savannah to St. Louis to New York.

In 1846, Lee got the chance he had been waiting for his whole military career when the United States went to war with Mexico. Serving under General Winfield Scott, Lee distinguished himself as a brave battle commander and a brilliant tactician. In the aftermath of the U.S. victory over its neighbor, Lee was held up as a hero. Scott showered Lee with particular praise, saying that if the United States went into another war, the government should consider taking out a life insurance policy on the commander.

But life away from the battlefield proved difficult for Lee to handle. He struggled with the mundane tasks associated with his work and life. For a time, he returned to his wife's family's plantation to manage the estate following the death of his father-in-law. The property had fallen under hard times, and for two long years, he tried to make it profitable again.

Robert E. Lee and Slavery

Lee did not own slaves in his youth, but he and Mary Custis Lee inherited enslaved people from both his mother and her father, and it’s believed Lee himself owned between 10-15 enslaved people during his lifetime. His racial attitudes reflected much of his background, and while he wrote to Mary about the moral and political evils of slavery, he held views of white superiority. He saw slavery as necessary to maintain order between races. He opposed abolitionism, which he saw as a northern effort to inflict political will on the South.

When Lee’s father-in-law died in 1857, Lee became executor of his estate, tasked with managing the Arlington plantation. During this period, despite his father-in-law’s decree that his slaves be freed within five years of his death, Lee was accused of being a cruel and harsh overseer, with reports of beatings of some of the 200 enslaved people under his control, particularly those who had tried to escape.

In late 1862, to fulfill the terms of his father-in-law’s will, Lee signed deeds freeing some 150 of the enslaved workers at Arlington and other Custis plantations. Just a few months later, the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect in January 1863, freeing enslaved peoples in Confederate territory. Despite the Proclamation, Lee, during his Gettysburg campaign later that year, continued his practice of seizing freed Blacks in Union territory to be sent into slavery in the South. Towards the end of the war, with the Confederacy desperate for recruits, he supported the idea of allowing enslaved peoples to serve in the army in exchange for their freedom. Still, the war ended before the policy was enacted.

Confederate Leader

In October 1859, Lee was summoned to put an end to an enslaved person insurrection led by John Brown at Harper's Ferry. Lee's orchestrated attack took just an hour to end the revolt, and his success put him on a shortlist of names to lead the Union Army should the nation go to war.

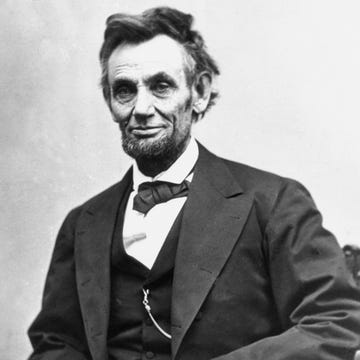

But Lee's commitment to the Army was superseded by his commitment to Virginia. After turning down an offer from President Abraham Lincoln to command the Union forces, Lee resigned from the military and returned home. While Lee had misgivings about centering a war on the slavery issue, after Virginia voted to secede from the nation on April 17, 1861, Lee agreed to help lead the Confederate forces.

Over the next year, Lee again distinguished himself on the battlefield. On June 1, 1862, he took control of the Army of Northern Virginia and drove back the Union Army during the Seven Days Battles near Richmond. In August of that year, he gave the Confederacy a crucial victory at Second Manassas (also known as the Second Battle of Bull Run).

But not all went well. He courted disaster when he tried to cross the Potomac at the Battle of Antietam on Sept. 17, barely escaping the site of the bloodiest single-day skirmish of the war, which left some 22,000 combatants dead.

From July 1-3, 1863, Lee's forces suffered another round of heavy casualties in Pennsylvania. The three-day stand-off, known as the Battle of Gettysburg , wiped out a vast chunk of Lee's army, halting his invasion of the North while helping to turn the tide for the Union.

By the fall of 1864, Union General Ulysses S. Grant had gained the upper hand, decimating much of Richmond, the Confederacy's capital, and Petersburg. By early 1865, the fate of the war was clear, a fact driven home on April 2 when Lee was forced to abandon Richmond. A week later, a reluctant and despondent Lee surrendered to Grant at a private home in Appomattox, Virginia.

"I suppose there is nothing for me to do but go and see General Grant," he told an aide. "And I would rather die a thousand deaths."

Final Years and Death

Saved from being hanged as a traitor by a forgiving Lincoln and Grant, Lee returned to his family in April 1865. He eventually accepted a job as president of Washington College in western Virginia and devoted his efforts toward boosting the institution's enrollment and financial support.

In late September 1870, Lee suffered a massive stroke. He died at his home in Lexington, Virginia, surrounded by family, on Oct. 12. He was buried in a chapel at nearby Washington College. Shortly afterward, the college was renamed Washington and Lee University.

Disputed Legacy and Statue

In the decades after the Civil War, sympathizers regarded Lee as a heroic figure of the South. Several monuments to the late general sprung up before the end of the 19th century, notably in New Orleans, Louisiana, and Dallas, Texas. Lee’s birthday is commemorated in several southern states. Until 2020, Lee-Jackson Day (also commemorating Civil War General Stonewall Jackson ) was celebrated each January in Virginia. Texas celebrates Lee on his Jan. 19th birthday as part of Confederate Heroes Day. Mississippi and Alabama celebrate a combined state holiday in late January honoring both Lee and civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr , while Florida commemorates Robert E. Lee Day as an unofficial state holiday.

Lee's complicated legacy became part of the culture wars that engulfed the country more than a century later. While some sought to have statues of Confederate leaders removed from public view, others argued that doing so represented an attempt to erase history. In 2017, after the City Council of Charlottesville, Virginia, voted to move a Lee statue from a park, Charlottesville became the site of several protests and counter-protests; in August, numerous demonstrators clashed, resulting in one death and 19 injuries.

In late October 2017, President Donald Trump 's chief of staff, John Kelly, further fanned the flames of the controversy with his appearance on Fox News. Addressing the topic of a Virginia church's decision to remove plaques that honored both Lee and Washington, Kelly called the Confederate general an "honorable man" and pointed to the "lack of an ability to compromise" as the cause of the Civil War. This analysis drew the ire of opponents.

Robert E. Lee in Movies

Robert E. Lee has been the subject of numerous biographies, documentaries, and novels, including several “alternative history” books depicting the South as winning the Civil War. Among the most popular books featuring Lee is a trilogy of novels . The first, written by Jeffrey Shaara, was the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Killer Angels, which became the basis for the 1993 film Gettysburg , starring Martin Sheen as Lee. After Jeffrey’s death, his son Michael completed the trilogy, publishing Gods and Generals and The Last Full Measure , the former of which was adapted into a 2003 film of the same name, starring Robert Duvall—himself a descendant of Robert E. Lee—as the famed general.

- I suppose there is nothing for me to do but go and see General Grant. And I would rather die a thousand deaths.

- Do your duty in all things. You cannot do more; you should never wish to do less.

- I cannot trust a man to control others who cannot control himself.

- Whiskey: I like it, I always did, and that is the reason I never use it.

- Obedience to lawful authority is the foundation of manly character.

- The education of a man is never completed until he dies.

- Never do a wrong thing to make a friend or keep one.

- You cannot be a true man until you learn to obey.

- In this enlightened age, there are few, I believe, but what will acknowledge that slavery as an institution is a moral and political evil in any country.

- You see what a poor sinner I am and how unworthy to possess what was given me; for that reason, it has been taken away.

- Everybody kind of perceives me as being angry. It's not anger, it's motivation.

- It is good that war is so horrible, or we might grow to like it.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us !

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Civil War Figures

The 13 Most Cunning Military Leaders

Clara Barton

Abraham Lincoln

The Story of President Ulysses S. Grant’s Arrest

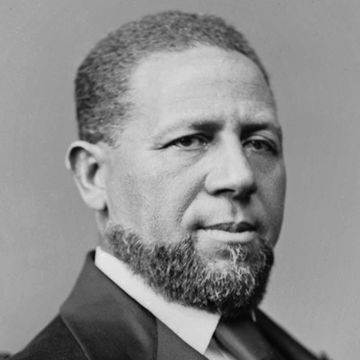

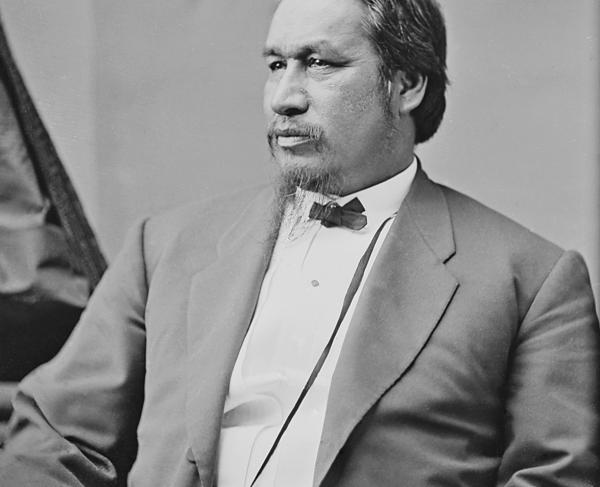

Hiram R. Revels

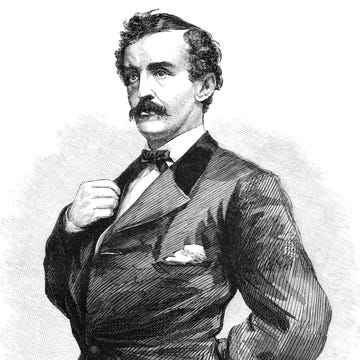

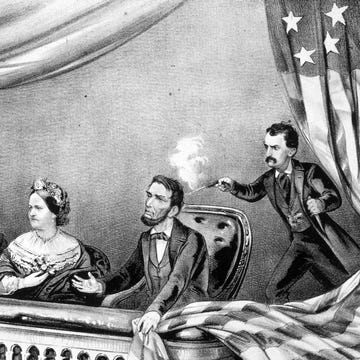

John Wilkes Booth

The Final Days of Abraham Lincoln

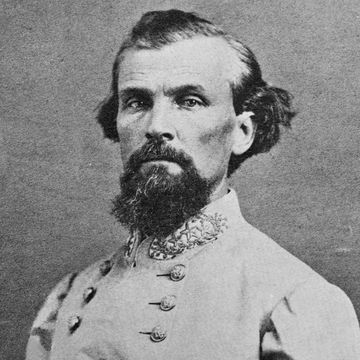

Stonewall Jackson

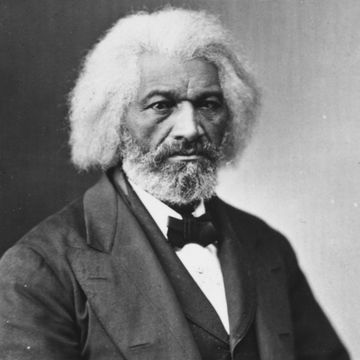

Frederick Douglass

Nathan Bedford Forrest

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Robert E. Lee

By: History.com Editors

Updated: August 29, 2022 | Original: October 29, 2009

Robert E. Lee was a Confederate general who led the South’s attempt at secession during the Civil War . He challenged Union forces during the war’s bloodiest battles, including Antietam and Gettysburg , before surrendering to Union General Ulysses S. Grant in 1865 at Appomattox Court House in Virginia, marking the end of the devastating conflict that nearly split the United States.

WATCH: Civil War Journal on HISTORY Vault

Who Was Robert E. Lee?

Robert Edward Lee was born in Stratford Hall, a plantation in Virginia, on January 19, 1807, to a wealthy and socially prominent family. His mother, Anne Hill Carter, also grew up on a plantation and his father, Colonel Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee, was descended from colonists and become a Revolutionary War leader and three-term governor of Virginia.

But the family hit hard times when Lee’s father made a series of bad investments that left him in debtors’ prison. He fled to the West Indies and died in 1818 while trying to return to Virginia when Lee was barely a teen.

With little money for his education, Lee went to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point for a military education. He graduated second in his class in 1829—and the following month he would lose his mother.

Did you know? Robert E. Lee graduated second in his class from West Point. He did not receive a single demerit during his four years at the academy.

Robert E. Lee's Children

After graduation, Lee’s military career quickly took off as he chose a position with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers .

A year later, he began courting a childhood connection, Mary Custis Washington. Given his father’s diminished reputation, Lee had to propose twice to win approval to wed Mary, the great-granddaughter of Martha Washington and the step-great-granddaughter of President George Washington .

The pair married in 1831; Lee and his wife had seven children, including three sons, George, William and Robert, who followed him into the military to fight for the Confederate States during the Civil War.

As the couple were establishing their family, Lee frequently travelled with the military on engineering projects. He first distinguished himself in battle during the Mexican-American War under General Winfield Scott in the battles of Veracruz , Churubusco and Chapultepec. Scott once declared that Lee was “the very best soldier that I ever saw in the field.”

Was Robert E. Lee a Slave Owner?

Lee did not grow up on a large plantation, but his wife inherited an enslaved worker in 1857 from her father, George Washington Park Custis.

Lee executed his father-in-law's will, which included Arlington House near Washington, D.C., a poorly managed plantation with debts and nearly 200 enslaved people, whom Custis wanted freed within five years of his death.

As a result of his father-in-law, Lee became owner of hundreds of enslaved workers. While historical accounts vary, Lee’s treatment of the enslaved peoples was described as being so combative and harsh that it led to revolts.

Lee at Harpers Ferry

During the 1850s, tensions between the abolitionist movement and slave owners reached a boiling point, and the union of states was near a breaking point. Lee entered the fray by halting a raid at Harpers Ferry in 1859, capturing radical abolitionist John Brown and his followers.

The following year, Abraham Lincoln was elected president, prompting seven Southern states — Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas — to secede in protest. U.S. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis became the president of the Confederate States of America.

The first attack of the Civil War came on April 12, 1861, when Confederates took control of South Carolina’s Fort Sumter .

Lee’s home state of Virginia seceded less than a week later, creating the defining moment of his career. When he was asked to lead Union forces, he resigned from military service rather than fight against his Virginia friends and neighbors.

General Robert E. Lee

Lee wasn’t a secessionist, but he immediately joined the Confederates and was named general and commander of the South’s fight for secession.

Lee has been widely criticized for his aggressive strategies that led to mass casualties. In the Battle of Antietam, on September 17, 1862, Lee made his first attempt at invading the North in the bloodiest single day of the war.

Antietam ended with roughly 23,000 casualties and the Union claiming victory for General George McClellan . Less than a week later, President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation .

The battles continued through the cold, harsh winter and into the summer of 1863, when Lee’s troops challenged Union forces in Pennsylvania during the three-day Battle of Gettysburg, which claimed 28,000 Confederate soldiers’ lives and 23,000 casualties on the Union side.

The war dragged on for two more years until a victory for Lee became impossible. With a dwindling army, Lee surrendered to Grant on April 9, 1865, at Appomattox Court House in Virginia, effectively ending the Civil War.

Arlington House

At the start of the war, Lee and his family headed South, leaving Arlington House, but they did not reclaim their property.

The federal government seized the estate (now the site of Arlington National Cemetery ) and used it for military graves for thousands of fallen Union soldiers, possibly to prevent Lee from ever returning home.

The Lee family residence is now managed by the National Park Service as Arlington House: the Robert E. Lee Memorial , and is open to the public for tours.

As a well-educated man with considerable social and military experience, Lee is known for many of his quotes regarding slavery , duty and military service, including:

- In this enlightened age, there are few I believe, but what will acknowledge, that slavery as an institution, is a moral and political evil in any country.

- Whiskey — I like it, I always did, and that is the reason I never use it.

- It is well that war is so terrible — lest we should grow too fond of it.

- So far from engaging in a war to perpetuate slavery, I am rejoiced that slavery is abolished. I believe it will be greatly for the interest of the South.

- I cannot trust a man to control others who cannot control himself.

- The education of a man is never completed until he dies.

- Do your duty in all things. You cannot do more, you should never wish to do less.

Robert E. Lee Day

In August of 1865, soon after the end of the war, Lee was invited to serve as president of Washington College (now Washington and Lee University ), where he and his family are buried.

Since his death at age 63 on October 12, 1870, following a stroke, he has retained a place of distinction in most Southern states.

Lee’s January 19 birthday is observed (to varying degrees) on the third Monday in January as Robert E. Lee Day, an official state holiday in Mississippi and Alabama, and on January 19 in Florida and Tennessee.

Robert E. Lee Statues

The Confederate general remains one of the most divisive figures in American history.

Statues and other memorials built in his honor have become flashpoints in cities such as New Orleans , Louisiana, Baltimore, Maryland and Dallas, Texas. Many Robert. E. Lee statues have been removed, but Virginia’s 2017 decision to take one down sparked a violent protest that turned deadly in Charlottesville.

While Lee did not support secession, he never defended the rights of enslaved peoples. Instead, he led the Confederates as they attempted to dissolve the United States that his own father helped create.

Robert E. Lee. PBS American Experience . Arlington House. Arlington National Cemetery . Robert E. Lee. Washington & Lee University . Robert E. Lee. Stratford Hall . The Civil War. American Battlefield Trust . Robert E. Lee Quotes. Son of the South . The Reader’s Companion to American History. Eric Foner and John A. Garraty, Editors. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Robert E. Lee

Born to Revolutionary War hero Henry "Light-Horse Harry" Lee in Stratford Hall, Virginia, Robert Edward Lee seemed destined for military greatness. Despite financial hardship that caused his father to depart to the West Indies, young Robert secured an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point, where he graduated second in the class of 1829. Two years later, he married Mary Anna Randolph Custis, a descendant of George Washington 's adopted son, John Parke Custis . Yet with all his military pedigree, Lee had not set foot on a battlefield. Instead, he served seventeen years as an officer in the Corps of Engineers, supervising and inspecting the construction of the nation's coastal defenses. Service during the 1846 war with Mexico, however, changed that. As a member of General Winfield Scott 's staff, Lee distinguished himself, earning three brevets for gallantry, and emerging from the conflict with the rank of colonel.

From 1852 to 1855, Lee served as superintendent of West Point, and was therefore responsible for educating many of the men who would later serve under him - and those who would oppose him - on the battlefields of the Civil War. In 1855 he left the academy to take a position in the cavalry and in 1859 was called upon to put down abolitionist John Brown ’s raid at Harpers Ferry.

Because of his reputation as one of the finest officers in the United States Army, Abraham Lincoln offered Lee the command of the Federal forces in April 1861. Lee declined and tendered his resignation from the army when the state of Virginia seceded on April 17, arguing that he could not fight against his own people. Instead, he accepted a general’s commission in the newly formed Confederate Army. His first military engagement of the Civil War occurred at Cheat Mountain, Virginia (now West Virginia) on September 11, 1861. It was a Union victory but Lee’s reputation withstood the public criticism that followed. He served as military advisor to President Jefferson Davis until June 1862 when he was given command of the wounded General Joseph E. Johnston 's embattled army on the Virginia peninsula.

Lee renamed his command the Army of Northern Virginia, and under his direction it would become the most famous and successful of the Confederate armies. This same organization also boasted some of the Confederacy's most inspiring military figures, including James Longstreet , Stonewall Jackson and the flamboyant cavalier J.E.B. Stuart . With these trusted subordinates, Lee commanded troops that continually manhandled their blue-clad adversaries and embarrassed their generals no matter what the odds.

Yet despite foiling several attempts to seize the Confederate capital, Lee recognized that the key to ultimate success was a victory on Northern soil. In September 1862, he launched an invasion into Maryland with the hope of shifting the war's focus away from Virginia. But when a misplaced dispatch outlining the invasion plan was discovered by Union commander George McClellan the element of surprise was lost, and the two armies faced off at the battle of Antietam . Though his plans were no longer a secret, Lee nevertheless managed to fight McClellan to a stalemate on September 17, 1862. Following the bloodiest one-day battle of the war, heavy casualties compelled Lee to withdraw under the cover of darkness. The remainder of 1862 was spent on the defensive, parrying Union thrusts at Fredericksburg and, in May of the following year, Chancellorsville .

The masterful victory at Chancellorsville gave Lee great confidence in his army, and the Rebel chief was inspired once again to take the fight to enemy soil. In late June of 1863, he began another invasion of the North, meeting the Union host at the crossroads town of Gettysburg , Pennsylvania. For three days Lee assailed the Federal army under George G. Meade in what would become the most famous battle of the entire war. Accustomed to seeing the Yankees run in the face of his aggressive troops, Lee attacked strong Union positions on high ground. This time, however, the Federals wouldn't budge. The Confederate war effort reached its high water mark on July 3, 1863 when Lee ordered a massive frontal assault against Meade's center, spear-headed by Virginians under Maj. Gen. George E. Pickett . The attack known as Pickett's charge was a failure and Lee, recognizing that the battle was lost, ordered his army to retreat. Taking full responsibility for the defeat, he wrote Jefferson Davis offering his resignation, which Davis refused to accept.

After the simultaneous Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg , Mississippi, Ulysses S. Grant assumed command of the Federal armies. Rather than making Richmond the aim of his campaign, Grant chose to focus the myriad resources at his disposal on destroying Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. In a relentless and bloody campaign, the Federal juggernaut bludgeoned the under-supplied Rebel band. In spite of his ability to make Grant pay in blood for his aggressive tactics, Lee had been forced to yield the initiative to his adversary, and he recognized that the end of the Confederacy was only a matter of time. By the summer of 1864, the Confederates had been forced into waging trench warfare outside of Petersburg . Though President Davis named the Virginian General-in-Chief of all Confederate forces in February 1865, only two months later, on April 9, 1865, Lee was forced to surrender his weary and depleted army to Grant at Appomattox Court House , effectively ending the Civil War.

Lee returned home on parole and eventually became the president of Washington College in Virginia (now known as Washington and Lee University). He remained in this position until his death on October 12, 1870 in Lexington, Virginia.

Test Your Knowledge

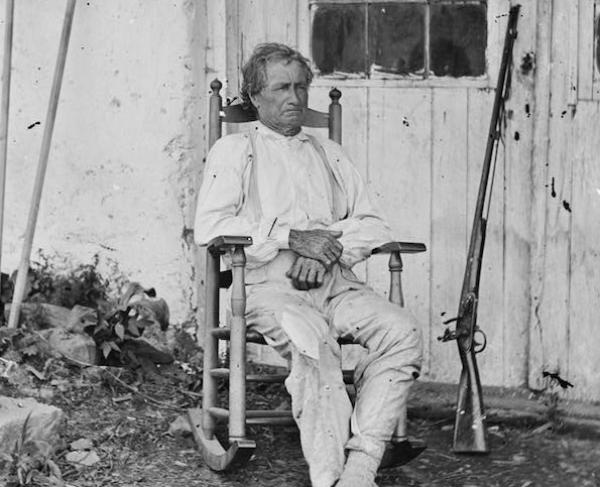

John L. Burns

Joseph H. De Castro

Related battles, you may also like.

The Civil War

A Smithsonian magazine special report

Making Sense of Robert E. Lee

“It is well that war is so terrible, or we should grow too fond of it.”— Robert E. Lee, at Fredericksburg

Roy Blount, Jr.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/lee_father.jpg)

Few figures in American history are more divisive, contradictory or elusive than Robert E. Lee, the reluctant, tragic leader of the Confederate Army, who died in his beloved Virginia at age 63 in 1870, five years after the end of the Civil War. In a new biography, Robert E. Lee , Roy Blount, Jr., treats Lee as a man of competing impulses, a “paragon of manliness” and “one of the greatest military commanders in history,” who was nonetheless “not good at telling men what to do.”

Blount, a noted humorist, journalist, playwright and raconteur, is the author or coauthor of 15 previous books and the editor of Roy Blount’s Book of Southern Humor . A resident of New York City and western Massachusetts, he traces his interest in Lee to his boyhood in Georgia. Though Blount was never a Civil War buff, he says “every Southerner has to make his peace with that War. I plunged back into it for this book, and am relieved to have emerged alive.”

“Also,” he says, “Lee reminds me in some ways of my father.”

At the heart of Lee’s story is one of the monumental choices in American history: revered for his honor, Lee resigned his U.S. Army commission to defend Virginia and fight for the Confederacy, on the side of slavery. “The decision was honorable by his standards of honor—which, whatever we may think of them, were neither self-serving nor complicated,” Blount says. Lee “thought it was a bad idea for Virginia to secede, and God knows he was right, but secession had been more or less democratically decided upon.” Lee’s family held slaves, and he himself was at best ambiguous on the subject, leading some of his defenders over the years to discount slavery’s significance in assessments of his character. Blount argues that the issue does matter: “To me it’s slavery, much more than secession as such, that casts a shadow over Lee’s honorableness.”

In the excerpt that follows, the general masses his troops for a battle over three humid July days in a Pennsylvania town. Its name would thereafter resound with courage, casualties and miscalculation: Gettysburg.

In his dashing (if sometimes depressive) antebellum prime, he may have been the most beautiful person in America, a sort of precursorcross between Cary Grant and Randolph Scott. He was in his element gossiping with belles about their beaux at balls. In theaters of grinding, hellish human carnage he kept a pet hen for company. He had tiny feet that he loved his children to tickle None of these things seems to fit, for if ever there was a grave American icon, it is Robert Edward Lee—hero of the Confederacy in the Civil War and a symbol of nobility to some, of slavery to others.

After Lee’s death in 1870, Frederick Douglass, the former fugitive slave who had become the nation’s most prominent African-American, wrote, “We can scarcely take up a newspaper . . . that is not filled with nauseating flatteries” of Lee, from which “it would seem . . . that the soldier who kills the most men in battle, even in a bad cause, is the greatest Christian, and entitled to the highest place in heaven.” Two years later one of Lee’s ex-generals, Jubal A. Early, apotheosized his late commander as follows: “Our beloved Chief stands, like some lofty column which rears its head among the highest, in grandeur, simple, pure and sublime.”

In 1907, on the 100th anniversary of Lee’s birth, President Theodore Roosevelt expressed mainstream American sentiment, praising Lee’s “extraordinary skill as a General, his dauntless courage and high leadership,” adding, “He stood that hardest of all strains, the strain of bearing himself well through the gray evening of failure; and therefore out of what seemed failure he helped to build the wonderful and mighty triumph of our national life, in which all his countrymen, north and south, share.”

We may think we know Lee because we have a mental image: gray. Not only the uniform, the mythic horse, the hair and beard, but the resignation with which he accepted dreary burdens that offered “neither pleasure nor advantage”: in particular, the Confederacy, a cause of which he took a dim view until he went to war for it. He did not see right and wrong in tones of gray, and yet his moralizing could generate a fog, as in a letter from the front to his invalid wife: “You must endeavour to enjoy the pleasure of doing good. That is all that makes life valuable.” All right. But then he adds: “When I measure my own by that standard I am filled with confusion and despair.”

His own hand probably never drew human blood nor fired a shot in anger, and his only Civil War wound was a faint scratch on the cheek from a sharpshooter’s bullet, but many thousands of men died quite horribly in battles where he was the dominant spirit, and most of the casualties were on the other side. If we take as a given Lee’s granitic conviction that everything is God’s will, however, he was born to lose.

As battlefield generals go, he could be extremely fiery, and could go out of his way to be kind. But in even the most sympathetic versions of his life story he comes across as a bit of a stick—certainly compared with his scruffy nemesis, Ulysses S. Grant; his zany, ferocious “right arm,” Stonewall Jackson; and the dashing “eyes” of his army, J.E.B. “Jeb” Stuart. For these men, the Civil War was just the ticket. Lee, however, has come down in history as too fine for the bloodbath of 1861-65. To efface the squalor and horror of the war, we have the image of Abraham Lincoln freeing the slaves, and we have the image of Robert E. Lee’s gracious surrender. Still, for many contemporary Americans, Lee is at best the moral equivalent of Hitler’s brilliant field marshal Erwin Rommel (who, however, turned against Hitler, as Lee never did against Jefferson Davis, who, to be sure, was no Hitler).

On his father’s side, Lee’s family was among Virginia’s and therefore the nation’s most distinguished. Henry, the scion who was to become known in the Revolutionary War as Light-Horse Harry, was born in 1756. He graduated from Princeton at 19 and joined the Continental Army at 20 as a captain of dragoons, and he rose in rank and independence to command Lee’s light cavalry and then Lee’s legion of cavalry and infantry. Without the medicines, elixirs, and food Harry Lee’s raiders captured from the enemy, George Washington’s army would not likely have survived the harrowing winter encampment of 1777-78 at Valley Forge. Washington became his patron and close friend. With the war nearly over, however, Harry decided he was underappreciated, so he impulsively resigned from the army. In 1785, he was elected to the Continental Congress, and in 1791 he was elected governor of Virginia. In 1794 Washington put him in command of the troops that bloodlessly put down the Whiskey Rebellion in western Pennsylvania. In 1799 he was elected to the U.S. Congress, where he famously eulogized Washington as “first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.”

Meanwhile, though, Harry’s fast and loose speculation in hundreds of thousands of the new nation’s acres went sour, and in 1808 he was reduced to chicanery. He and his second wife, Ann Hill Carter Lee, and their children departed the Lee ancestral home, where Robert was born, for a smaller rented house in Alexandria. Under the conditions of bankruptcy that obtained in those days, Harry was still liable for his debts. He jumped a personal appearance bail—to the dismay of his brother, Edmund, who had posted a sizable bond—and wangled passage, with pitying help from President James Monroe, to the West Indies. In 1818, after five years away, Harry headed home to die, but got only as far as Cumberland Island, Georgia, where he was buried. Robert was 11.

Robert appears to have been too fine for his childhood, for his education, for his profession, for his marriage, and for the Confederacy. Not according to him. According to him, he was not fine enough. For all his audacity on the battlefield, he accepted rather passively one raw deal after another, bending over backward for everyone from Jefferson Davis to James McNeill Whistler’s mother. (When he was superintendent of the U.S. Military Academy, Lee acquiesced to Mrs. Whistler’s request on behalf of her cadet son, who was eventually dismissed in 1854.)

By what can we know of him? The works of a general are battles, campaigns and usually memoirs. The engagements of the Civil War shape up more as bloody muddles than as commanders’ chess games. For a long time during the war, “Old Bobbie Lee,” as he was referred to worshipfully by his troops and nervously by the foe, had the greatly superior Union forces spooked, but a century and a third of analysis and counteranalysis has resulted in no core consensus as to the genius or the folly of his generalship. And he wrote no memoir. He wrote personal letters—a discordant mix of flirtation, joshing, lyrical touches, and stern religious adjuration—and he wrote official dispatches that are so impersonal and (generally) unselfserving as to seem above the fray.

During the postbellum century, when Americans North and South decided to embrace R. E. Lee as a national as well as a Southern hero, he was generally described as antislavery. This assumption rests not on any public position he took but on a passage in an 1856 letter to his wife. The passage begins: “In this enlightened age, there are few I believe, but what will acknowledge, that slavery as an institution, is a moral & political evil in any Country. It is useless to expatiate on its disadvantages.” But he goes on: “I think it however a greater evil to the white than to the black race, & while my feelings are strongly enlisted in behalf of the latter, my sympathies are more strong for the former. The blacks are immeasurably better off here than in Africa, morally, socially & physically. The painful discipline they are undergoing, is necessary for their instruction as a race, & I hope will prepare & lead them to better things. How long their subjugation may be necessary is known & ordered by a wise Merciful Providence.”

The only way to get inside Lee, perhaps, is by edging fractally around the record of his life to find spots where he comes through; by holding up next to him some of the fully realized characters—Grant, Jackson, Stuart, Light-Horse Harry Lee, John Brown—with whom he interacted; and by subjecting to contemporary skepticism certain concepts—honor, “gradual emancipation,” divine will—upon which he unreflectively founded his identity.

He wasn’t always gray. Until war aged him dramatically, his sharp dark brown eyes were complemented by black hair (“ebon and abundant,” as his doting biographer Douglas Southall Freeman puts it, “with a wave that a woman might have envied”), a robust black mustache, a strong full mouth and chin unobscured by any beard, and dark mercurial brows. He was not one to hide his looks under a bushel. His heart, on the other hand . . . “The heart, he kept locked away,” as Stephen Vincent Benét proclaimed in “John Brown’s Body,” “from all the picklocks of biographers.” Accounts by people who knew him give the impression that no one knew his whole heart, even before it was broken by the war. Perhaps it broke many years before the war. “You know she is like her papa, always wanting something,” he wrote about one of his daughters. The great Southern diarist of his day, Mary Chesnut, tells us that when a lady teased him about his ambitions, he “remonstrated—said his tastes were of the simplest. He only wanted a Virginia farm—no end of cream and fresh butter—and fried chicken. Not one fried chicken or two—but unlimited fried chicken.” Just before Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, one of his nephews found him in the field, “very grave and tired,” carrying around a fried chicken leg wrapped in a piece of bread, which a Virginia countrywoman had pressed upon him but for which he couldn’t muster any hunger.

One thing that clearly drove him was devotion to his home state. “If Virginia stands by the old Union,” Lee told a friend, “so will I. But if she secedes (though I do not believe in secession as a constitutional right, nor that there is sufficient cause for revolution), then I will follow my native State with my sword, and, if need be, with my life.”

The North took secession as an act of aggression, to be countered accordingly. When Lincoln called on the loyal states for troops to invade the South, Southerners could see the issue as defense not of slavery but of homeland. A Virginia convention that had voted 2 to 1 against secession, now voted 2 to 1 in favor.

When Lee read the news that Virginia had joined the Confederacy, he said to his wife, “Well, Mary, the question is settled,” and resigned the U.S. Army commission he had held for 32 years.

The days of July 1-3, 1863, still stand among the most horrific and formative in American history. Lincoln had given up on Joe Hooker, put Maj. Gen. George G. Meade in command of the Army of the Potomac, and sent him to stop Lee’s invasion of Pennsylvania. Since Jeb Stuart’s scouting operation had been uncharacteristically out of touch, Lee wasn’t sure where Meade’s army was. Lee had actually advanced farther north than the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, when he learned that Meade was south of him, threatening his supply lines. So Lee swung back in that direction. On June 30 a Confederate brigade, pursuing the report that there were shoes to be had in Gettysburg, ran into Federal cavalry west of town, and withdrew. On July 1 a larger Confederate force returned, engaged Meade’s advance force, and pushed it back through the town—to the fishhook-shaped heights comprising Cemetery Hill, Cemetery Ridge, Little Round Top, and Round Top. It was almost a rout, until Maj. Gen. O. O. Howard, to whom Lee as West Point superintendent had been kind when Howard was an unpopular cadet, and Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock rallied the Federals and held the high ground. Excellent ground to defend from. That evening Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, who commanded the First Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia, urged Lee not to attack, but to swing around to the south, get between Meade and Washington, and find a strategically even better defensive position, against which the Federals might feel obliged to mount one of those frontal assaults that virtually always lost in this war. Still not having heard from Stuart, Lee felt he might have numerical superiority for once. “No,” he said, “the enemy is there, and I am going to attack him there.”

The next morning, Lee set in motion a two-part offensive: Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell’s corps was to pin down the enemy’s right flank, on Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill, while Longstreet’s, with a couple of extra divisions, would hit the left flank—believed to be exposed—on Cemetery Ridge. To get there Longstreet would have to make a long march under cover. Longstreet mounted a sulky objection, but Lee was adamant. And wrong.

Lee didn’t know that in the night Meade had managed by forced marches to concentrate nearly his entire army at Lee’s front, and had deployed it skillfully—his left flank was now extended to Little Round Top, nearly three-quarters of a mile south of where Lee thought it was. The disgruntled Longstreet, never one to rush into anything, and confused to find the left flank farther left than expected, didn’t begin his assault until 3:30 that afternoon. It nearly prevailed anyway, but at last was beaten gorily back. Although the two-pronged offensive was ill-coordinated, and the Federal artillery had knocked out the Confederate guns to the north before Ewell attacked, Ewell’s infantry came tantalizingly close to taking Cemetery Hill, but a counterattack forced them to retreat.

On the third morning, July 3, Lee’s plan was roughly the same, but Meade seized the initiative by pushing forward on his right and seizing Culp’s Hill, which the Confederates held. So Lee was forced to improvise. He decided to strike straight ahead, at Meade’s heavily fortified midsection. Confederate artillery would soften it up, and Longstreet would direct a frontal assault across a mile of open ground against the center of Missionary Ridge. Again Longstreet objected; again Lee wouldn’t listen. The Confederate artillery exhausted all its shells ineffectively, so was unable to support the assault—which has gone down in history as Pickett’s charge because Maj. Gen. George Pickett’s division absorbed the worst of the horrible bloodbath it turned into.

Lee’s idolaters strained after the war to shift the blame, but the consensus today is that Lee managed the battle badly. Each supposed major blunder of his subordinates—Ewell’s failure to take the high ground of Cemetery Hill on July 1, Stuart’s getting out of touch and leaving Lee unapprised of what force he was facing, and the lateness of Longstreet’s attack on the second day—either wasn’t a blunder at all (if Longstreet had attacked earlier he would have encountered an even stronger Union position) or was caused by a lack of forcefulness and specificity in Lee’s orders.

Before Gettysburg, Lee had seemed not only to read the minds of Union generals but almost to expect his subordinates to read his. He was not in fact good at telling men what to do. That no doubt suited the Confederate fighting man, who didn’t take kindly to being told what to do—but Lee’s only weakness as a commander, his otherwise reverent nephew Fitzhugh Lee would write, was his “reluctance to oppose the wishes of others, or to order them to do anything that would be disagreeable and to which they would not consent.” With men as well as with women, his authority derived from his sightliness, politeness, and unimpeachability. His usually cheerful detachment patently covered solemn depths, depths faintly lit by glints of previous and potential rejection of self and others. It all seemed Olympian, in a Christian cavalier sort of way. Officers’ hearts went out to him across the latitude he granted them to be willingly, creatively honorable. Longstreet speaks of responding to Lee at another critical moment by “receiving his anxious expressions really as appeals for reinforcement of his unexpressed wish.” When people obey you because they think you enable them to follow their own instincts, you need a keen instinct yourself for when they’re getting out of touch, as Stuart did, and when they are balking for good reason, as Longstreet did. As a father Lee was fond but fretful, as a husband devoted but distant. As an attacking general he was inspiring but not necessarily cogent.

At Gettysburg he was jittery, snappish. He was 56 and bone weary. He may have had dysentery, though a scholar’s widely publicized assertion to that effect rests on tenuous evidence. He did have rheumatism and heart trouble. He kept fretfully wondering why Stuart was out of touch, worrying that something bad had happened to him. He had given Stuart broad discretion as usual, and Stuart had overextended himself. Stuart wasn’t frolicking. He had done his best to act on Lee’s written instructions: “You will . . . be able to judge whether you can pass around their army without hindrance, doing them all the damage you can, and cross the [Potomac] east of the mountains. In either case, after crossing the river, you must move on and feel the right of Ewell’s troops, collecting information, provisions, etc.” But he had not, in fact, been able to judge: he met several hindrances in the form of Union troops, a swollen river that he and his men managed only heroically to cross, and 150 Federal wagons that he captured before he crossed the river. And he had not sent word of what he was up to.

When on the afternoon of the second day Stuart did show up at Gettysburg, after pushing himself nearly to exhaustion, Lee’s only greeting to him is said to have been, “Well, General Stuart, you are here at last.” A coolly devastating cut: Lee’s way of chewing out someone who he felt had let him down. In the months after Gettysburg, as Lee stewed over his defeat, he repeatedly criticized the laxness of Stuart’s command, deeply hurting a man who prided himself on the sort of dashing freelance effectiveness by which Lee’s father, Maj. Gen. Light-Horse Harry, had defined himself. A bond of implicit trust had been broken. Loving-son figure had failed loving-father figure and vice versa.

In the past Lee had also granted Ewell and Longstreet wide discretion, and it had paid off. Maybe his magic in Virginia didn’t travel. “The whole affair was disjointed,” Taylor the aide said of Gettysburg. “There was an utter absence of accord in the movements of the several commands.”

Why did Lee stake everything, finally, on an ill-considered thrust straight up the middle? Lee’s critics have never come up with a logical explanation. Evidently he just got his blood up, as the expression goes. When the usually repressed Lee felt an overpowering need for emotional release, and had an army at his disposal and another one in front of him, he couldn’t hold back. And why should Lee expect his imprudence to be any less unsettling to Meade than it had been to the other Union commanders?

The spot against which he hurled Pickett was right in front of Meade’s headquarters. (Once, Dwight Eisenhower, who admired Lee’s generalship, took Field Marshal Montgomery to visit the Gettysburg battlefield. They looked at the site of Pickett’s charge and were baffled. Eisenhower said, “The man [Lee] must have got so mad that he wanted to hit that guy [Meade] with a brick.”)

Pickett’s troops advanced with precision, closed up the gaps that withering fire tore into their smartly dressed ranks, and at close quarters fought tooth and nail. Acouple of hundred Confederates did break the Union line, but only briefly. Someone counted 15 bodies on a patch of ground less than five feet wide and three feet long. It has been estimated that 10,500 Johnny Rebs made the charge and 5,675—roughly 54 percent—fell dead or wounded. As a Captain Spessard charged, he saw his son shot dead. He laid him out gently on the ground, kissed him, and got back to advancing.

As the minority who hadn’t been cut to ribbons streamed back to the Confederate lines, Lee rode in splendid calm among them, apologizing. “It’s all my fault,” he assured stunned privates and corporals. He took the time to admonish, mildly, an officer who was beating his horse: “Don’t whip him, captain; it does no good. I had a foolish horse, once, and kind treatment is the best.” Then he resumed his apologies: “I am very sorry—the task was too great for you—but we mustn’t despond.” Shelby Foote has called this Lee’s finest moment. But generals don’t want apologies from those beneath them, and that goes both ways. After midnight, he told a cavalry officer, “I never saw troops behave more magnificently than Pickett’s division of Virginians. . . . ” Then he fell silent, and it was then that he exclaimed, as the officer later wrote it down, “Too bad! Too bad! OH! TOO BAD!”

Pickett’s charge wasn’t the half of it. Altogether at Gettysburg as many as 28,000 Confederates were killed, wounded, captured, or missing: more than a third of Lee’s whole army. Perhaps it was because Meade and his troops were so stunned by their own losses—about 23,000—that they failed to pursue Lee on his withdrawal south, trap him against the flooded Potomac, and wipe his army out. Lincoln and the Northern press were furious that this didn’t happen.

For months Lee had been traveling with a pet hen. Meant for the stewpot, she had won his heart by entering his tent first thing every morning and laying his breakfast egg under his Spartan cot. As the Army of Northern Virginia was breaking camp in all deliberate speed for the withdrawal, Lee’s staff ran around anxiously crying, “ Where is the hen? ” Lee himself found her nestled in her accustomed spot on the wagon that transported his personal matériel. Life goes on.

After Gettysburg, Lee never mounted another murderous head-on assault. He went on the defensive. Grant took over command of the eastern front and 118,700 men. He set out to grind Lee’s 64,000 down. Lee had his men well dug in. Grant resolved to turn his flank, force him into a weaker position, and crush him.

On April 9, 1865, Lee finally had to admit that he was trapped. At the beginning of Lee’s long, combative retreat by stages from Grant’s overpowering numbers, he had 64,000 men. By the end they had inflicted 63,000 Union casualties but had been reduced themselves to fewer than 10,000.

To be sure, there were those in Lee’s army who proposed continuing the struggle as guerrillas or by reorganizing under the governors of the various Confederate states. Lee cut off any such talk. He was a professional soldier. He had seen more than enough of governors who would be commanders, and he had no respect for ragtag guerrilladom. He told Col. Edward Porter Alexander, his artillery commander, . . . the men would become mere bands of marauders, and the enemy’s cavalry would pursue them and overrun many wide sections they may never have occasion to visit. We would bring on a state of affairs it would take the country years to recover from.”

“And, as for myself, you young fellows might go to bushwhacking, but the only dignified course for me would be, to go to Gen. Grant and surrender myself and take the consequences.” That is what he did on April 9, 1865, at a farmhouse in the village of Appomattox Court House, wearing a fulldress uniform and carrying a borrowed ceremonial sword which he did not surrender.

Thomas Morris Chester, the only black correspondent for a major daily newspaper (the Philadelphia Press ) during the war, had nothing but scorn for the Confederacy, and referred to Lee as a “notorious rebel.” But when Chester witnessed Lee’s arrival in shattered, burned-out Richmond after the surrender, his dispatch sounded a more sympathetic note. After Lee “alighted from his horse, he immediately uncovered his head, thinly covered with silver hairs, as he had done in acknowledgment of the veneration of the people along the streets,” Chester wrote. “There was a general rush of the small crowd to shake hands with him. During these manifestations not a word was spoken, and when the ceremony was through, the General bowed and ascended his steps. The silence was then broken by a few voices calling for a speech, to which he paid no attention. The General then passed into his house, and the crowd dispersed.”

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

Advertisement

Supported by

The Making and the Breaking of the Legend of Robert E. Lee

- Share full article

By Eric Foner

- Aug. 28, 2017

In the Band’s popular song “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” an ex-Confederate soldier refers to Robert E. Lee as “the very best.” It is difficult to think of another song that mentions a general by name. But Lee has always occupied a unique place in the national imagination. The ups and downs of his reputation reflect changes in key elements of Americans’ historical consciousness — how we understand race relations, the causes and consequences of the Civil War and the nature of the good society.

Born in 1807, Lee was a product of the Virginia gentry — his father a Revolutionary War hero and governor of the state, his wife the daughter of George Washington’s adopted son. Lee always prided himself on following the strict moral code of a gentleman. He managed to graduate from West Point with no disciplinary demerits, an almost impossible feat considering the complex maze of rules that governed the conduct of cadets.

While opposed to disunion, when the Civil War broke out and Virginia seceded, Lee went with his state. He won military renown for defeating (until Gettysburg) a succession of larger Union forces. Eventually, he met his match in Ulysses S. Grant and was forced to surrender his army in April 1865. At Appomattox he urged his soldiers to accept the war’s outcome and return to their homes, rejecting talk of carrying on the struggle in guerrilla fashion. He died in 1870, at the height of Reconstruction, when biracial governments had come to power throughout the South.

But, of course, what interests people who debate Lee today is his connection with slavery and his views about race. During his lifetime, Lee owned a small number of slaves. He considered himself a paternalistic master but could also impose severe punishments, especially on those who attempted to run away. Lee said almost nothing in public about the institution. His most extended comment, quoted by all biographers, came in a letter to his wife in 1856. Here he described slavery as an evil, but one that had more deleterious effects on whites than blacks. He felt that the “painful discipline” to which they were subjected benefited blacks by elevating them from barbarism to civilization and introducing them to Christianity. The end of slavery would come in God’s good time, but this might take quite a while, since to God a thousand years was just a moment. Meanwhile, the greatest danger to the “liberty” of white Southerners was the “evil course” pursued by the abolitionists, who stirred up sectional hatred. In 1860, Lee voted for John C. Breckinridge, the extreme pro-slavery candidate. (A more moderate Southerner, John Bell, carried Virginia that year.)

Lee’s code of gentlemanly conduct did not seem to apply to blacks. During the Gettysburg campaign, he did nothing to stop soldiers in his army from kidnapping free black farmers for sale into slavery. In Reconstruction, Lee made it clear that he opposed political rights for the former slaves. Referring to blacks (30 percent of Virginia’s population), he told a Congressional committee that he hoped the state could be “rid of them.” Urged to condemn the Ku Klux Klan’s terrorist violence, Lee remained silent.

By the time the Civil War ended, with the Confederate president, Jefferson Davis, deeply unpopular, Lee had become the embodiment of the Southern cause. A generation later, he was a national hero. The 1890s and early 20th century witnessed the consolidation of white supremacy in the post-Reconstruction South and widespread acceptance in the North of Southern racial attitudes. A revised view of history accompanied these developments, including the triumph of what David Blight, in his influential book “Race and Reunion” (2001), calls a “reconciliationist” memory of the Civil War. The war came to be seen as a conflict in which both sides consisted of brave men fighting for noble principles — union in the case of the North, self-determination on the part of the South. This vision was reinforced by the “cult of Lincoln and Lee,” each representing the noblest features of his society, each a figure Americans of all regions could look back on with pride. The memory of Lee, this newspaper wrote in 1890, was “the possession of the American people.”

Reconciliation excised slavery from a central role in the story, and the struggle for emancipation was now seen as a minor feature of the war. The Lost Cause, a romanticized vision of the Old South and Confederacy, gained adherents throughout the country. And who symbolized the Lost Cause more fully than Lee?

This outlook was also taken up by the Southern Agrarians, a group of writers who idealized the slave South as a bastion of manly virtue in contrast to the commercialism and individualism of the industrial North. At a time when traditional values appeared to be in retreat, character trumped political outlook, and character Lee had in spades. Frank Owsley, the most prominent historian among the Agrarians, called Lee “the soldier who walked with God.” (Many early biographies directly compared Lee and Christ.) Moreover, with the influx of millions of Catholics and Jews from southern and eastern Europe alarming many Americans, Lee seemed to stand for a society where people of Anglo-Saxon stock controlled affairs.

Historians in the first decades of the 20th century offered scholarly legitimacy to this interpretation of the past, which justified the abrogation of the constitutional rights of Southern black citizens. At Columbia University, William A. Dunning and his students portrayed the granting of black suffrage during Reconstruction as a tragic mistake. The Progressive historians — Charles Beard and his disciples — taught that politics reflected the clash of class interests, not ideological differences. The Civil War, Beard wrote, should be understood as a transfer of national power from an agricultural ruling class in the South to the industrial bourgeoisie of the North; he could tell the entire story without mentioning slavery except in a footnote. In the 1920s and 1930s, a group of mostly Southern historians known as the revisionists went further, insisting that slavery was a benign institution that would have died out peacefully. A “blundering generation” of politicians had stumbled into a needless war. But the true villains, as in Lee’s 1856 letter, were the abolitionists, whose reckless agitation poisoned sectional relations. This interpretation dominated teaching throughout the country, and reached a mass audience through films like “The Birth of a Nation,” which glorified the Klan, and “Gone With the Wind,” with its romantic depiction of slavery. The South, observers quipped, had lost the war but won the battle over its history.

As far as Lee was concerned, the culmination of these trends came in the publication in the 1930s of a four-volume biography by Douglas Southall Freeman, a Virginia-born journalist and historian. For decades, Freeman’s hagiography would be considered the definitive account of Lee’s life. Freeman warned readers that they should not search for ambiguity, complexity or inconsistency in Lee, for there was none — he was simply a paragon of virtue. Freeman displayed little interest in Lee’s relationship to slavery. The index to his four volumes contained 22 entries for “devotion to duty,” 19 for “kindness,” 53 for Lee’s celebrated horse, Traveller. But “slavery,” “slave emancipation” and “slave insurrection” together received five. Freeman observed, without offering details, that slavery in Virginia represented the system “at its best.” He ignored the postwar testimony of Lee’s former slave Wesley Norris about the brutal treatment to which he had been subjected. In 1935 Freeman was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in biography.

That same year, however, W. E. B. Du Bois published “Black Reconstruction in America,” a powerful challenge to the mythologies about slavery, the Civil War and Reconstruction that historians had been purveying. Du Bois identified slavery as the fundamental cause of the war and emancipation as its most profound outcome. He portrayed the abolitionists as idealistic precursors of the 20th-century struggle for racial justice, and Reconstruction as a remarkable democratic experiment — the tragedy was not that it was attempted but that it failed. Most of all, Du Bois made clear that blacks were active participants in the era’s history, not simply a problem confronting white society. Ignored at the time by mainstream scholars, “Black Reconstruction” pointed the way to an enormous change in historical interpretation, rooted in the egalitarianism of the civil rights movement of the 1960s and underpinned by the documentary record of the black experience ignored by earlier scholars. Today, Du Bois’s insights are taken for granted by most historians, although they have not fully penetrated the national culture.

Inevitably, this revised view of the Civil War era led to a reassessment of Lee, who, Du Bois wrote elsewhere, possessed physical courage but not “the moral courage to stand up for justice to the Negro.” Even Lee’s military career, previously viewed as nearly flawless, underwent critical scrutiny. In “The Marble Man” (1977), Thomas Connelly charged that “a cult of Virginia authors” had disparaged other Confederate commanders in an effort to hide Lee’s errors on the battlefield. James M. McPherson’s “Battle Cry of Freedom,” since its publication in 1988 the standard history of the Civil War, compared Lee’s single-minded focus on the war in Virginia unfavorably with Grant’s strategic grasp of the interconnections between the eastern and western theaters.

Lee’s most recent biographer , Michael Korda, does not deny his subject’s admirable qualities. But he makes clear that when it came to black Americans, Lee never changed. Lee was well informed enough to know that, as the Confederate vice president, Alexander H. Stephens, declared, slavery and “the great truth that the Negro is not equal to the white man” formed the “cornerstone” of the Confederacy; he chose to take up arms in defense of a slaveholders’ republic. After the war, he could not envision an alternative to white supremacy.

What Korda calls Lee’s “legend” needs to be retired. And whatever the fate of his statues and memorials, so long as the legacy of slavery continues to bedevil American society, it seems unlikely that historians will return Lee, metaphorically speaking, to his pedestal.

Eric Foner is the author of “The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery,” winner of the Pulitzer Prize for history. His most recent book is “Battles for Freedom: The Use and Abuse of American History. Essays From The Nation.”

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

Salman Rushdie’s new memoir, “Knife,” addresses the attack that maimed him in 2022, and pays tribute to his wife who saw him through .

Recent books by Allen Bratton, Daniel Lefferts and Garrard Conley depict gay Christian characters not usually seen in queer literature.

What can fiction tell us about the apocalypse? The writer Ayana Mathis finds unexpected hope in novels of crisis by Ling Ma, Jenny Offill and Jesmyn Ward .

At 28, the poet Tayi Tibble has been hailed as the funny, fresh and immensely skilled voice of a generation in Māori writing .

Amid a surge in book bans, the most challenged books in the United States in 2023 continued to focus on the experiences of L.G.B.T.Q. people or explore themes of race.

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

Marketplace

Listen live.

Fresh Air opens the window on contemporary arts and issues with guests from worlds as diverse as literature and economics. Terry Gross hosts this multi-award-winning daily interview and features program.

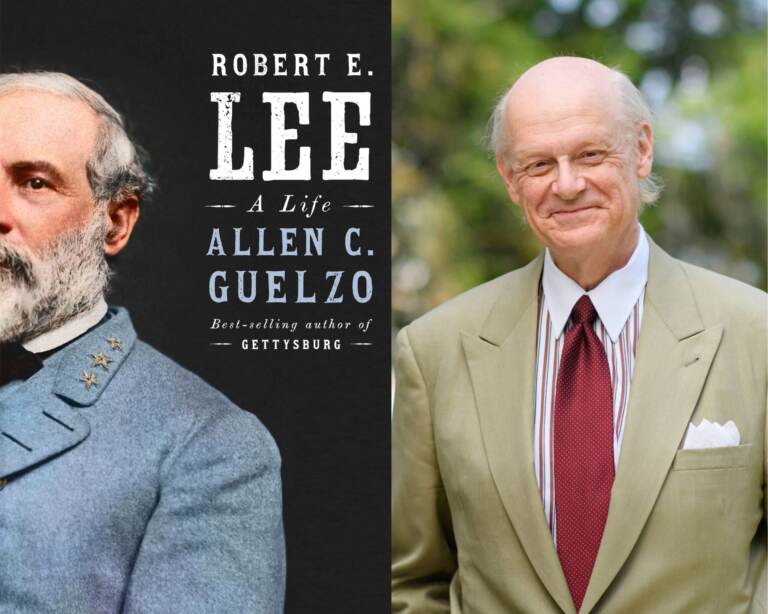

‘Robert E. Lee: A Life’

Author allen c. guelzo joins us to share his latest biography, a character study of a complicated civil war figure..

Photos via Penguin Random House/Allen C. Guelzo

Robert E. Lee: A Life is a new biography that examines one of the most well-known and controversial Civil War figures. Author ALLEN C. GUELZO , professor and historian at Princeton University, covers Lee’s life starting with his traumatic childhood that involved the disappearance of his father, to the ultimate betrayal of his country. When General Lee violated his oath to the US Army and commanded Confederate soldiers, his treason was accompanied by praise and admiration, and while he claimed to believe slavery was immoral, he vigorously and strategically fought to defend it. This hour, as our nation grapples with removing statues of confederate leaders and changing school buildings that bear Lee’s name, Guelzo joins us to share his character study of a complicated figure.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

Brought to you by Radio Times

Radio Times

WHYY's Radio Times is an engaging and timely call-in program that tackles wide-ranging issues of concern to listeners in the Delaware Valley.

Subscribe for free

You may also like.

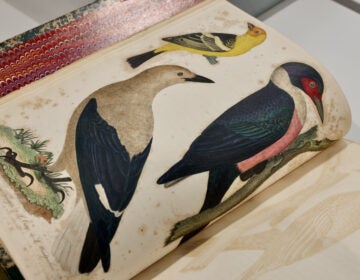

Several birds named after Philadelphians will be renamed as part of an effort to stop honoring enslavers and racists

The American Ornithological Society will remove people’s names from birds. Many of those birds are now named after prominent Philadelphia scientists.

12 hours ago

Wilmington author tackles Latino representation gap with children’s books featuring Dominican culture

Jasdomin Santana champions diversity in children's literature by incorporating Dominican culture into her storytelling.

A Pa. congressional race could test Democrats who have criticized Israel’s handling of war

Summer Lee is the first Black woman elected to Congress from Pa. If defeated, she would be the first Democratic incumbent in Congress to lose a primary this year.

Want a digest of WHYY’s programs, events & stories? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Together we can reach 100% of WHYY’s fiscal year goal

Workers remove the monument of Confederate General Robert E. Lee on Saturday, July 10, 2021 in Charlottesville, Va. The removal of the Lee statue follows years of contention, community anguish and legal fights. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

John C. Clark / AP

A new Robert E. Lee biography and why it’s relevant today

Historian Allen Guelzo has written a biography: Robert E. Lee – A Life , that has a new relevancy today. A racial reckoning over the past two years and a nation that is re-examining its past has put Lee back in the news.

Lee was looked upon as an icon in the south and respected as a military leader after commanding the Confederate army in the Civil War. But Lee has come under scrutiny for leading an army that was fighting to maintain slavery and was a slaveholder himself.

Guelzo’s book addresses the question of whether Robert E. Lee committed treason against the United States when he resigned from the U.S. Army to join the Confederacy and take up arms against a country he had sworn to defend. The history books most often say Lee said he “couldn’t raise his sword against Virginia” his home state. Guelzo writes there may have been more personal thinking to Lee’s decision.

Dr. Allen Guelzo was featured in a virtual Midtown Scholar Bookstore event recently and is on today’s Smart Talk .

See video of the interview here.

- Uncategorized

Support for WITF is provided by:

Become a WITF sponsor today »

- Regional & State News

- National & World News

- Politics & Policy

- Climate & Energy

- The Morning Agenda Podcast

- The Purple Buck Newsletter

- Atomic Cannon

- Centralia, Washington

- Corridor Counts

- Mental Health Behind Bars

- September 11: 20 Years Later

- Three Mile Island

- Toward Racial Justice

Toward Racial Justice: Voices from the Midstate

- Archived Projects

The days of journalism’s one-way street of simply producing stories for the public have long been over. Now, it’s time to find better ways to interact with you and ensure we meet your high standards of what a credible media organization should be.

- Connect With Our Journalists

- Get the WITF Mobile App

- Subscribe to Our Newsletters

- Watch WITF Productions

- Brighter Days

- Careers That Work

- PNC C-Speak: The Language of Executives

- Spelling Bee

- Transforming Health

- The Melanin Report

- Watch WITF Online

- TV Schedules

- Video On Demand

- WITF Passport

- WITF Mosaic

- PBS Programs

- PBS NewsHour Live Stream

- Listen to WITF Online

- Radio Schedule

- NPR Programs

- On-Air Hosts

- Closed Captioning

- Become a Sponsor

- Ready, Set, Explore!

- Kids’ Night Out

- Slide into Summer Camp

- Ready, Set, Explore Kindergarten!

- Explore in the Classroom

- Professional Development

- Lesson Plans

- Making the Most of Screen Time

- Ready Set Music

- K-2 STEM Resources

- Watch WITFK PBS KIDS 24/7

- PBS LearningMedia

- Civilian Soldier School

- Overlooked Art

- The Cookery

- The Spark Features

- The To Do List

- Mosaic on YouTube

- Ticket Giveaways

- Pick of the Month

- WITF Travel

- Monthly Giving

- Premier Circle

- Vehicle Donations

- Stocks, IRA, etc.

- Planned Giving

- Matching Gifts

- Tribute Gifts

- Membership FAQs

- Update Payment Method

- Donor Privacy Policy

- Contact WITF

- Event Sponsorships

- Volunteering

- Protect My Public Media

- /witfmosaic

- Newsletters

Supply chain problems affecting economic recovery

Needs subhed for next in json.

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: $23.95 $23.95 FREE delivery: Monday, April 29 on orders over $35.00 shipped by Amazon. Ships from: Amazon Sold by: Caladan Knowledge

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Buy used: $15.26

Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) is a service we offer sellers that lets them store their products in Amazon's fulfillment centers, and we directly pack, ship, and provide customer service for these products. Something we hope you'll especially enjoy: FBA items qualify for FREE Shipping and Amazon Prime.

If you're a seller, Fulfillment by Amazon can help you grow your business. Learn more about the program.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Robert E. Lee: A Life Hardcover – Deckle Edge, September 28, 2021

Purchase options and add-ons

- Print length 608 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Knopf

- Publication date September 28, 2021

- Dimensions 6.66 x 1.53 x 9.57 inches

- ISBN-10 1101946229

- ISBN-13 978-1101946220

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Similar items that may ship from close to you

Editorial Reviews

About the author, excerpt. © reprinted by permission. all rights reserved., product details.