Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 27 December 2018

Prevalence and phenomenology of violent ideation and behavior among 200 young people at clinical high-risk for psychosis: an emerging model of violence and psychotic illness

- Gary Brucato 1 ,

- Paul S. Appelbaum 1 ,

- Michael D. Masucci 1 ,

- Stephanie Rolin 1 ,

- Melanie M. Wall 1 ,

- Mark Levin 1 ,

- Rebecca Altschuler 1 ,

- Michael B. First 1 ,

- Jeffrey A. Lieberman 1 &

- Ragy R. Girgis 1

Neuropsychopharmacology volume 44 , pages 907–914 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

1935 Accesses

16 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Risk factors

- Signs and symptoms

In a previously reported longitudinal study of violent ideation (VI) and violent behavior (VB) among 200 youths at clinical high-risk (CHR) for psychosis, we found that VI, hitherto underinvestigated, strongly predicted transition to first-episode psychosis (FEP) and VB, in close temporal proximity. Here, we present participants’ baseline characteristics, examining clinical and demographic correlates of VI and VB. These participants, aged 13–30, were examined at Columbia University Medical Center’s Center of Prevention and Evaluation, using clinical interviews and the structured interview for psychosis-risk syndromes (SIPS). At the onset of our longitudinal study, we gathered demographics, signs and symptoms, and descriptions of VI and VB. One-third of participants reported VI ( n = 65, 32.5%) at baseline, experienced as intrusive and ego-dystonic, and associated with higher suspiciousness and overall positive symptoms. Less than one-tenth reported VB within 6 months of baseline ( n = 17, 8.5%), which was unrelated to SIPS-positive symptoms, any DSM diagnosis or other clinical characteristic. The period from conversion through post-FEP stabilization may be characterized by heightened risk of behavioral disinhibition and violence. We provide a preliminary model of how violence risk may peak at various points in the course of psychotic illness.

You have full access to this article via your institution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Suicidal behavior across a broad range of psychiatric disorders

Self-harm behaviour and externally-directed aggression in psychiatric outpatients: a multicentre, prospective study (viormed-2 study)

Borderline personality disorder: associations with psychiatric disorders, somatic illnesses, trauma, and adverse behaviors

Introduction.

Schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders are generally preceded by an attenuated or clinical high-risk (CHR) phase, characterized by delusional ideas, perceptual disturbances, and disorganization of thought, with lower levels of conviction, intensity, frequency, and behavioral impact than seen in full-blown psychosis [ 1 ]. Such subthreshold positive symptoms are evaluated using the structured interview for psychosis-risk syndromes (SIPS) [ 2 ], a measure that delineates an attenuated positive symptom syndrome (APSS). This construct served as the basis for the attenuated psychosis syndrome (APS), included in the current edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) as a condition warranting further research [ 3 ]. Both the APS and APSS are highly heterogeneous, with regard to diagnosis, encompassing individuals with possible features of a number of other DSM categories, but who display a specific constellation of symptoms suggestive of potential emergent psychosis. Such persons are uncommon, with an estimated prevalence in the general population as low as 0.3% and an estimated annual incidence of 1/10,000 [ 4 ]. Furthermore, relatively few CHR individuals, generally not more than 30–35% in the most robust samples, actually progress to full-blown psychotic illness [ 1 ].

A newly emerging line of inquiry suggests that the CHR state may constitute a period of increased risk for violence, a topic of considerable current interest. Although most individuals with mental illness are not dangerous and the majority of violence is committed by people without mental disorders, there is some evidence that positive symptoms of full-blown schizophrenia and other psychoses [ 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ], such as delusions and hallucinations, are related to VB [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ]. Nonadherence to medications [ 16 , 17 ] and poor insight [ 18 ] have been shown to mediate this. Nielssen and Large [ 19 ], examining the prevalence of homicide in psychosis, reported that approximately 1 in 9000 persons with psychosis who have received treatment commit homicide each year, while 1 homicide occurs for every 629 presentations of first-episode psychosis. Other research suggests that alcohol [ 20 , 21 ] or drug abuse [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ] are the key mediating factors, and may account for more of the risk than psychosis [ 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 ]. Langeveld et al. [ 31 ] prospectively examined violence, as well as multiple clinical characteristics, including substance use, among 178 first-episode participants for 10 years. A decade postbaseline, 20% of participants had been arrested or incarcerated, though most of these events occurred before baseline. At the 10-year follow-up, 15% had exposed others to threats or violence in the prior year. Illegal drug use at baseline and the 5-year mark was predictive of violence in the year preceding endpoint evaluation.

Other possible mediating factors have been identified. A report from the UK National EDEN study [ 32 ] suggested that there may be multiple pathways to violence in first-episode psychosis and that lifelong antisocial traits should be considered alongside psychotic symptomatology. A meta-regression analysis of 100 studies by Witt et al. [ 33 ] found criminal history, substance, or alcohol use, nonadherence with psychotherapy and medication, poor impulse control, and prior hostile behavior to be associated with violence. Coid et al. [ 34 ] particularly implicate paranoid ideation as the link between violence and psychosis.

Violence risk in the CHR phase of psychotic illness has been far less frequently examined. Marshall et al. [ 35 ] reported that 24% of 442 CHR individuals described violent content during SIPS interviews, with 12% reporting multiple types of violent content. Such content was associated with more severe positive symptoms, anxiety, negative beliefs about oneself, and being the target of bullying prior to age 16. Notably, violent content was defined to include thoughts of harm to the self by others—that is to say, suspicious concerns with violent content—which constituted the most common subtype. Content surrounding hurting others (11.54%) and perceptual disturbances related to interpersonal violence (3.17%) were less common. Violent content in relation to actual violent behaviors was not investigated.

Recently, we presented results of a longitudinal study of 200 CHR youth, ages 13–30. Each was examined for up to 2 years for VI and VB using the SIPS and clinical interview [ 36 ]. Violent content was rated according to categories drawn from the MacArthur Community Violence Interview [ 29 ]. VB within the 6 months preceding initial assessment and VI at baseline both very strongly predicted transition to first-episode psychosis (FEP), as well as VB within an average of 1 week (SD = 35 days) following conversion. This promising finding was independent of more than 40 clinical and demographic variables. Moreover, the targets of the participants’ baseline VI were found to be entirely different than those ultimately attacked, perhaps suggesting impulsivity, and loss of executive control with the transition to frank psychosis.

The hypothesis that violence risk may increase as CHR individuals approach conversion to frank psychosis has some independent empirical support. More prominent psychotic symptoms and less insight have been found to increase the risk of violent acts [ 18 , 24 , 37 ]. Moreover, the aforementioned meta-analysis by Nielssen and Large [ 19 ] found that 38.5% of homicides committed by individuals with psychotic illness occur during the FEP, prior to first receiving treatment. We know of no reports of a higher prevalence of homicide in the psychosis-risk state. A prior meta-analysis by Fazel et al. [ 38 ] also reported that schizophrenia and other psychoses are associated with violence, particularly homicide, and that the relationship between violence (excluding homicide) and psychosis may be largely related to comorbid substance use. However, individual studies considering the temporal relationship between violence and first onset of psychotic symptoms were not examined.

In the present report, we examine the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of a comparatively large cohort of CHR individuals. Our specific aim was to describe clinical correlates of VI and VB in the 6 months prior to baseline, considering associations with specific signs and symptoms assessed by the SIPS.

Data were collected at the Center of Prevention and Evaluation (COPE), an outpatient research program for the evaluation and treatment of attenuated positive symptoms at the New York State Psychiatric Institute (NYSPI)/Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) in New York City. The NYSPI Institutional Review Board approved the research. All adults provided written informed consent, while minors provided written assent, with written informed consent obtained from a parent.

Participants

Potential participants were referred to COPE between 2003 and 2016 by a network of academic centers, private practitioners, clinics, and hospitals, or were self-referred after reviewing the center’s web site, for evaluation of possible emergent psychotic symptoms. Participants were between the ages of 13 and 30 and were required to have symptoms that meet criteria for at least one of the psychosis-risk syndromes delineated in the SIPS (see Supplementary Material for specific definitions). These include the aforementioned APSS, the genetic risk and functional decline syndrome and the brief intermittent psychosis syndrome (BIPS). However, it should be noted that all 200 participants met APSS criteria and none met BIPS criteria. Exclusion criteria included lack of proficiency in English; a current or lifetime DSM psychotic disorder, including affective psychoses; a DSM disorder better accounting for the clinical presentation; I.Q. < 70; medical conditions affecting the central nervous system; marked risk of harm to self or others; unwillingness to participate in research; geographic distance; or a DSM diagnosis of current substance or alcohol abuse or dependence. Use of antipsychotic medication was not exclusionary, provided that there was clear evidence that positive symptoms of an attenuated, but never fully psychoticlevel syndrome were present at medication onset. The study sample is described in Table 1 .

The data presented here were collected at baseline. In addition to a general clinical interview, each participant was also evaluated with either the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies [ 39 ] or Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P); [ 40 ]. Those under age 16 completed the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia, Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL) [ 41 ].

The SIPS [ 42 ], with which all participants were examined, involves a semistructured interview that probes for past and current signs and symptoms of attenuated versus threshold psychotic illness. It defines criteria for psychosis-risk states, as well as threshold psychosis. The measure contains 19 subscales, divided into positive, negative, disorganization, and general symptom components. The critical items for determining attenuated versus full-blown psychosis, are the five positive symptoms: P.1.: unusual thought content/delusional ideas, P.2.: suspiciousness/persecutory ideas, P.3.: grandiose ideas, P.4.: perceptual abnormalities/hallucinations, and P.5.: disorganized communication. These are scored 0–6 according to specific anchors provided for each symptom that distinguish among degrees of frequency, conviction, and behavioral impact: 0, absent; 1, questionably present; 2, mild; 3, moderate; 4, moderately severe; 5, severe, but not psychotic; and 6, psychotic, delusional conviction, at least intermittently. Negative, disorganization, and general signs and symptoms are rated from 0 (absent) to 6 (extreme) (see Supplementary Material for specific subscales).

APSS criteria, satisfied by all participants described here, require that one or more of the 5 positive symptoms occurs at a score of 3–5 and is new or has worsened by 1 or more points in the past 12 months, and no score of 6 on a positive symptom has ever been achieved. SIPS administrators were certified and established scoring consensus.

Frank psychosis is defined by the SIPS as having met criteria for a score of 6 on one or more positive symptoms in one’s lifetime for at least 1 h per day at an average frequency of 4 days per week over one month, and/or serious danger or disorganization as the result of the positive symptom(s).

VI and VB were coded as “present” or “not present.” Information about VB in the 6 months prior to baseline was amassed via the SIPS, the clinical interview, and collateral information from prior records, family members and referral sources. It was defined as any violent or aggressive act, including those with a deadly weapon, any assault producing injury, threat with a deadly weapon in hand, sexual assault, assault producing no injury (e.g., pushing or slapping), or use of a weapon without threats or injury. These were defined based on the categories for violence and other aggressive acts established in the MacArthur Community Violence Interview [ 29 ]. In accord with this framework, assault with no injury was categorized as Other Aggressive Acts (OAA). VI encompassed any violent or aggressive fantasies or thoughts directed toward others, intrusive or nonintrusive, which we categorized by adapting the MacArthur interview framework to score VI at baseline in the same manner as VB and OAA.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22 [ 43 ]. Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test of associations and continuous variables with t-tests. The dependent variables were the presences of either VI or VB. A Fisher’s exact p value was calculated for chi-square analyses with small expected cell counts. For tests failing Levene’s test for equality of variance, a corrected test statistic was calculated.

Violent ideation

Approximately, one-third of the sample presented with VI ( n = 65, 32.5%; see Table 2 ), almost uniformly experienced as ego-dystonic and intrusive in nature. To better understand this, ideational content was divided into the subcategories of “severe” violence and ideation related to OAA. Severe VI was defined as thought content involving serious harm to another person, with or without a weapon. Within this category, 20 respondents reported thoughts or mental images of causing serious harm to another with their fists, feet or other body parts. Eighteen described VI of harming another person with a weapon (including guns, knives, saws, and razors), six reported VI that was sexual in nature (rape and sexual assault), and two described VI involving killing others with bombs. In three cases, VI involved causing the death of another person in an unspecified manner. Four respondents described VI in which they caused both serious injury with a weapon and sexual harm. Two endorsed thoughts and mental images of causing serious harm with a weapon and with fire, and one had thoughts of causing serious sexual harm, as well as harm without a weapon.

Ideation related to OAA involves violence toward another that might not result in serious harm. This group ( n = 9) included 8 individuals with VI of shoving, slapping, throwing people a short distance, and/or nonserious hitting. One individual reported minor VI of an unspecified nature.

There were no sex or ethnic (i.e., Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic) differences between individuals with and without VI. Interestingly, individuals identifying as Caucasian reported less VI than other racial groups. Those with VI were more likely to have symptoms that met criteria for schizotypal personality disorder (SPD; χ 2 (1) = 5.88; p = 0.015), comorbid with the SIPS APSS category, and to report histories of nonsexual trauma ( χ 2 (1) = 4.93; p = 0.026). Medication status; suicidality, including both suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior; and history of sexual trauma did not distinguish between those with and without VI. Comorbid DSM diagnoses did not significantly differ between those with and without VI.

Individuals with VI reported higher degrees of suspiciousness, as well as total overall positive symptoms than those without (see Table 3 ). A statistical association between VI and SIPS symptom P.1.: unusual thought content/delusional ideas was observed, though this is undoubtedly due to the fact that VI was frequently reported by participants when responding to P.1. inquiries probing for intrusive ideas and a sense of one’s thoughts being out of one’s control.

There was no significant difference in negative symptoms among those with and without VI. Individuals with VI exhibited higher scores for unusual behavior and appearance; more bizarre ideas (e.g., ideas which are not scientifically plausible and are difficult to understand); and higher total disorganization scores. Individuals with VI were also noted to experience more severely dysphoric mood states. Other SIPS symptom subscales were comparable between those with and without VI.

Violent behavior

Evidence and/or self-report of VB in the 6 months preceding baseline were found in less than one-tenth of the sample ( n = 17, 8.5%). When present, VB was unrelated to sex, ethnicity, or race. There were no differences in terms of sexual or nonsexual trauma histories, suicidal ideation, suicidal behavior, medication status, or comorbid DSM diagnoses between individuals with and without prebaseline VB. There were no differences between individuals with and without VB with regard to any individual SIPS subscale, or in terms of positive, negative, disorganization, or general symptoms.

The present study describes violent behaviors and thoughts reported by 200 young people at clinical high-risk of psychotic illness at the onset of a 2-year longitudinal study. The prospective aspects of the study have been previously described [ 36 ]. Here, we explore relationships between violent thoughts at baseline, violent actions in the 6-month period preceding research participation, and psychiatric diagnoses and SIPS interview subscales, advancing our understanding of how psychosis and violence risk may coexist or develop in tandem in certain individuals.

Analyses revealed that thoughts and mental images with violent content, generally experienced as intrusive and ego-dystonic, were common in our sample, occurring in one-third of participants. The content of this ideation was found typically to be severe in nature, involving physical harm to others using one’s body or a weapon. Sexual content was uncommon. Violent thoughts appear to be relatively common in attenuated psychosis. Thus, violent thoughts of this nature may constitute part of the phenomenology of attenuated psychosis, analogous to suicidal thoughts in a significant number of depressed persons. However, actual suicide attempts in depression and violence in the CHR state are far less common. The frequency of VI in our CHR cohort is potentially important: as noted in our previous report, VI was an extremely good predictor in our cohort of both conversion to threshold psychosis and, within an average of seven days (SD = 35 days) postpsychosis onset, violent actions toward others. However, given the potential stigmatization of the already marginalized CHR population, we should emphasize that most individuals in our cohort who described VI never actually progressed to VB. Furthermore, it should be noted that violence among CHR persons may be multidetermined, or entirely unrelated to VI or psychotic symptoms.

Results also indicated that violent thoughts are generally related to overall positive symptoms, and particularly to suspiciousness. A review by Darrell-Berry et al. [ 44 ] of 15 studies examining the relationship between paranoia and violence found that, in the most rigorous investigations, a positive association emerged between these factors. It is intriguing, however, that, in our research, VI was virtually never elicited by questions inquiring about suspicious ideas on the SIPS [ 36 ]. It is unclear whether this may relate to the wording of suspiciousness inquiries in the SIPS. However, rather than suggest that CHR persons with some degree of paranoia are more likely to harbor violent thoughts, it may be that both suspiciousness and VI are commonly co-occurring, but not necessarily related, manifestations of a nascent psychotic illness in some individuals. The finding that a history of non-sexual trauma is associated with VI has some support in Marshall et al.'s [ 35 ] finding that violent content on the SIPS was linked with more incidents of bullying prior to age 16. The findings that, in our cohort, VI was statistically associated with non-Caucasian race and comorbid SPD have no precedent in the CHR literature. Additional research is needed before meaningful interpretations can be ventured.

By contrast, violent actions in the 6-month period preceding baseline were remarkably uncommon, occurring in less than one-tenth of the cohort. Given that information regarding prebaseline violence was dependent on self-report by participants, as well as collateral information from family members and referrers, it is unclear to what degree information about prebaseline violent acts may be underrepresented, although there are reasons to believe that self and collateral report offer more complete data than official records [ 29 ].

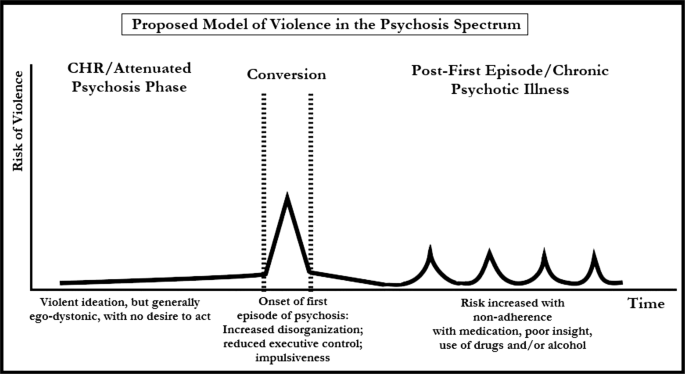

These results demonstrating relationships between VI and positive symptoms are consistent with Marshall et al.’s [ 35 ] finding regarding the frequency of violent content in an independent CHR sample, as well as VB in syndromal psychosis [ 45 ]. The collective data reveal that individuals with psychotic illness may be at the highest risk for violence around the time of conversion to psychosis through the remission of the FEP. Moreover, some data suggest that periods of intensification of symptoms (e.g., the perihospitalization period) during the chronic state of psychotic illness also represent periods of slightly increased risk for violence, though the risk may not be as high as during the FEP period [ 29 ]. Thus, the overall picture, which we have incorporated into a preliminary model (see Fig. 1 ), suggests that, in the phase of attenuated positive symptoms that generally precedes full-blown psychosis, violent thoughts and mental images are commonly experienced, but are either not acted upon or dismissed as inconsistent with individuals’ actual thoughts and desires. However, such thoughts are strongly associated with later progression to threshold psychosis and subsequent aggression, such that they may constitute critical aspects of assessments of conversion status and violence risk, if independently validated, in future research. Moreover, it is with the conversion to FEP that one is most likely to act out aggressively.

Proposed model of violence in the psychosis spectrum

The literature and our research, on balance, suggest that this window of increased risk closes only after the FEP has stabilized, perhaps following a period of treatment. Furthermore, our previously described data tell us that this postconversion aggression is generally unfocused and impulsive in nature, affecting targets other than those initially envisioned by participants in thoughts and mental images [ 36 ]. This point is intriguing in light of our finding here that a SIPS index of unusual behavior and appearance was associated with VI in our cohort. The facts may collectively indicate that violence risk is associated with gradual deterioration of executive behavioral controls as one transitions to psychosis. What is unclear is whether the reduced risk after the first episode is related to medications, psychotherapy, the natural progression of the condition, or some other compensatory factor, which warrants further research.

Among the limitations of our research is that it was conducted at a single site, reducing the generalizability of our findings, pending attempts at replication. Generalizability may have also been impacted by the elimination of persons with certain clinical features from our CHR sample; specifically, those whose presentations meet criteria for current substance or alcohol abuse or dependence [ 26 , 33 ] or who were deemed too clinically acute to participate in research (i.e., at imminent risk of violence and requiring evaluation in the emergency room). These exclusions may have significantly affected reports of both past and current violent thoughts and behaviors. Moreover, excluding individuals with histories of substance or alcohol abuse and/or risk of imminent serious aggression may have reduced the number of participants with symptoms associated with comorbid conduct disorder in childhood or antisocial personality disorder in adulthood, which may also have affected the degree of violence in our population. There is some literature to suggest that a history of delinquent behaviors may increase the likelihood of violence in psychotic illness [ 32 , 45 ]. Additionally, a very small number of individuals did not complete baseline screening beyond the SIPS, such that we have some missing data. It also unclear to what degree social bias may have led to minimization of reporting of VI and VB. Finally, all participants were voluntarily presenting for treatment, which may distinguish this sample from nonhelp-seeking CHR persons.

However, our sample size of 200 participants is comparatively large, as individuals whose symptoms meet criteria for attenuated psychotic illness are decidedly uncommon. Another strength of the study lies in the inclusion of VI, and not solely VB, in the variables we examined. We believe that our collective findings regarding the frequency of VI in the CHR state and its predictive nature may, with time and additional study, offer a promising new window for research and clinical intervention.

Funding and disclosure

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health: Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (grant numbers UL1TR000040, 2KL2RR024157, K23MH066279, R21MH086125, R01P50MH086385, R01MH093398-01, K23MH106746). This project was supported by the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation; Lieber Center for Schizophrenia Research; and the New York State Office of Mental Health Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene.

Fusar-Poli P, Borgwardt S, Bechdolf A, Addington J, Richer-Rossler A, Schultze-Lutter F, et al. The psychosis high-risk state: a comprehensive state-of-the-art review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:107–20.

Article Google Scholar

Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, Cadenhead K, Cannon T, Ventura J, et al. Prodromal assessment with the structured interview for prodromal syndromes and the scale of prodromal symptoms: predictive validity, interrater reliability, and training to reliability. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29:703–15.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5 edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Book Google Scholar

Addington J, Cadenhead KS, Cannon TD, Cornblatt B, McGlashan TH, Perkins DO, et al. North American Prodromal Longitudinal Study: a collaborative multisite approach to prodromal schizophrenia research. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:665–72.

Douglas KS, Guy LS, Hart SD. Psychosis as a risk factor for violence to others: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2009;135:679–706.

Hodgins S, Mednick SA, Brennan PA, Schulsinger F, Engberg M. Mental disorder and crime. Evidence from a Danish birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:489–96.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Lindqvist P, Allebeck P. Schizophrenia and crime. A longitudinal follow-up of 644 schizophrenics in Stockholm. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157:345–50.

Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Essock SM, Osher FC, Wagner HR, Goodman LA, et al. The social-environmental context of violent behavior in persons treated for severe mental illness. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1523–31.

Taylor PJ, Bragado-Jimenez MD. Women, psychosis and violence. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2009;32:56–64.

Coid JW, Ullrich S, Kallis C, Keers R, Barker D, Cowden F, et al. The relationship between delusions and violence: findings from the East London first episode psychosis study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:465–71.

Keers R, Ullrich S, Destavola BL, Coid JW. Association of violence with emergence of persecutory delusions in untreated schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:332–9.

McNiel DE, Eisner JP, Binder RL. The relationship between command hallucinations and violence. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51:1288–92.

Taylor PJ, Leese M, Williams D, Butwell M, Daly R, Larkin E. Mental disorder and violence. A special (high security) hospital study. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172:218–26.

Ullrich S, Keers R, Coid JW. Delusions, anger, and serious violence: new findings from the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:1174–81.

Bartels SJ, Drake RE, Wallach MA, Freeman DH. Characteristic hostility in schizophrenic outpatients. Schizophr Bull. 1991;17:163–71.

Elbogen EB, Van Dorn RA, Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Monahan J. Treatment engagement and violence risk in mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:354–60.

Yesavage JA. Inpatient violence and the schizophrenic patient: an inverse correlation between danger-related events and neuroleptic levels. Biol Psychiatry. 1982;17:1331–7.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Buckley PF, Hrouda DR, Friedman L, Noffsinger SG, Resnick PJ, Camlin-Shingler K. Insight and its relationship to violent behavior in patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1712–4.

Nielssen O, Large M. Rates of homicide during the first episode of psychosis and after treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:702–12.

Eronen M, Tiihonen J, Hakola P. Schizophrenia and homicidal behavior. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22:83–89.

Rasanen P, Tiihonen J, Isohanni M, Rantakallio P, Lehtonen J, Moring J. Schizophrenia, alcohol abuse, and violent behavior: a 26-year followup study of an unselected birth cohort. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24:437–41.

Elbogen EB, Johnson SC. The intricate link between violence and mental disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:152–61.

Rolin SA, Marino LA, Pope LG, Compton MT, Lee RJ, Rosenfeld B, et al. (2018). Recent violence and legal involvement among young adults with early psychosis enrolled in Coordinated Specialty Care. Early Interv Psychiatry 1–9. E-pub ahead May 9, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12675 .

Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Hiday VA, Borum R, Wagner HR, Burns BJ. Violence and severe mental illness: the effects of substance abuse and nonadherence to medication. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:226–31.

Arseneault L, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor PJ, Silva PA. Mental disorders and violence in a total birth cohort: results from the Dunedin Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:979–86.

Fazel S, Langstrom N, Hjern A, Grann M, Lichtenstein P. Schizophrenia, substance abuse, and violent crime. J Am Med Assoc. 2009b;301:2016–23.

Foley SR, Kelly BD, Clarke M, McTigue O, Gervin M, Kamali M, et al. Incidence and clinical correlates of aggression and violence at presentation in patients with first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2005;72:161–8.

Appelbaum PS, Robbins PC, Monahan J. Violence and delusions: data from the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:566–72.

Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, Robbins PC, Appelbaum PS, Grisso T, et al. Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:393–401.

Chang WC, Chan SS, Hui CL, Chan SK, Lee EH, Chen EY. Prevalence and risk factors for violent behavior in young people presenting with first-episode psychosis in Hong Kong: a 3-year follow-up study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49:914–22.

Langeveld J, Bjørkly S, Auestad B, Barder H, Evensen J, Ten Velden Hegelstad W, et al. Treatment and violent behavior in persons with first episode psychosis during a 10-year prospective follow-up study. Schizophr Res. 2014;156:272–6.

Winsper C, Singh SP, Marwaha S, Amos T, Lester H, Everard L, et al. Pathways to violent behavior during first-episode psychosis: a report from the UK National EDEN Study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:1287–93.

Witt K, van Dorn R, Fazel S. Risk factors for violence in psychosis: systematic review and meta-regression analysis of 110 studies. PloS ONE. 2013;8:e55942.

Coid JW, Ullrich S, Bebbington P, Fazel S, Keers R. Paranoid ideation and violence: meta-analysis of individual subject data of 7 population surveys. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42:907–15.

Marshall C, Deighton S, Cadenhead KS, Cannon TD, Cornblatt BA, McGlashan TH, et al. The violent content in attenuated psychotic symptoms. Psychiatry Res. 2016;242:61–66.

Brucato G, Appelbaum PS, Lieberman JA, Wall MM, Feng T, Masucci MD, et al. A longitudinal study of violent behavior in a psychosis-risk cohort. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43:264–71.

Arango C, Barba AC, Gonzalez-Salvador T, Ordoriez AC. Violence in inpatients with schizophrenia: a prospective study. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25:493–503.

Fazel S, Gulati G, Linsell L, Geddes JR, Grann M. Schizophrenia and violence: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2009a;6:e1000120.

Nurnberger JI Jr, Blejar MC, Kaufmann CA, York-Cooler C, Simpson SG, Harkavy-Friedman J, et al. Diagnostic interview for genetic studies. Rationale, unique features, and training. Arch General Psychiatry. 1994;51:849–59.

First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW (2002). Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition. (SCID-I/P). New York: Biometrics Research, NYSPI.

Kaufman JB, Birmaher D, Brent D, Rao U, Ryan N. Kiddie-Sads-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL). Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Department of Psychiatry; 1996.

Google Scholar

McGlashan TH, Miller TJ, Woods SW, Hoffman RE, Davidson LA. A scale for the assessment of prodromal symptoms and states. In: Miller TJ, Mednick SA, McGlashan TH, Liberger J, Johannessen JO, (editors). Early Intervention in Psychotic Disorders. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2001. p. 135–49.

Chapter Google Scholar

IBM Corporation. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. 22.0 edn. Armonk, NY: IBM Corporation; 2013.

Darrell-Berry H, Berry K, Bucci S. The relationship between paranoia and aggression in psychosis: a systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2016;172:169–76.

Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Van Dorn RA, Elbogen EB, Wagner HR, Rosenheck RA, et al. A national study of violent behavior in persons with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:490–9.

Download references

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the individuals who participated in this study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

The New York State Psychiatric Institute/Columbia, University Medical Center, New York, NY, USA

Gary Brucato, Paul S. Appelbaum, Michael D. Masucci, Stephanie Rolin, Melanie M. Wall, Mark Levin, Rebecca Altschuler, Michael B. First, Jeffrey A. Lieberman & Ragy R. Girgis

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Gary Brucato .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

R.G. acknowledges receiving research support from Otsuka, Allergan/Forest, BioAvantex, and Genentech. J.L. has received support administered through his institution in the form of funding or medication supplies for investigator initiated research from Lilly, Denovo, Biomarin, Novartis, Taisho, Teva, Alkermes, and Boehringer Ingelheim, and is a member of the advisory board of Intracellular Therapies and Pierre Fabre. He neither accepts nor receives any personal financial remuneration for consulting, advisory board or research activities. He holds a patent from Repligen and receives royalty payments from “SHRINKS: The Untold Story of Psychiatry.” The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary material, rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Brucato, G., Appelbaum, P.S., Masucci, M.D. et al. Prevalence and phenomenology of violent ideation and behavior among 200 young people at clinical high-risk for psychosis: an emerging model of violence and psychotic illness. Neuropsychopharmacol. 44 , 907–914 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-018-0304-5

Download citation

Received : 19 September 2018

Revised : 14 December 2018

Accepted : 16 December 2018

Published : 27 December 2018

Issue Date : April 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-018-0304-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Psychometric properties of an arabic translation of the long (12 items) and short (7 items) forms of the violent ideations scale (vis) in a non-clinical sample of adolescents.

- Feten Fekih-Romdhane

- Diana Malaeb

- Souheil Hallit

BMC Psychiatry (2024)

Feasibility and Utility of Different Approaches to Violence Risk Assessment for Young Adults Receiving Treatment for Early Psychosis

- Stephanie A. Rolin

- Jennifer Scodes

- Paul S. Appelbaum

Community Mental Health Journal (2022)

Bullying in clinical high risk for psychosis participants from the NAPLS-3 cohort

- Jean Addington

Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology (2022)

The Impact of Increasing Community-Directed State Mental Health Agency Expenditures on Violent Crime

- John S. Palatucci

- Alan C. Monheit

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 23 January 2017

Mental illness and violent behavior: the role of dissociation

- Aliya R. Webermann 1 &

- Bethany L. Brand 2

Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation volume 4 , Article number: 2 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

43k Accesses

12 Citations

67 Altmetric

Metrics details

The role of mental illness in violent crime is elusive, and there are harmful stereotypes that mentally ill people are frequently violent criminals. Studies find greater psychopathology among violent offenders, especially convicted homicide offenders, and higher rates of violence perpetration and victimization among those with mental illness. Emotion dysregulation may be one way in which mental illness contributes to violent and/or criminal behavior. Although there are many stereotyped portrayals of individuals with dissociative disorders (DDs) being violent, the link between DDs and crime is rarely researched.

We reviewed the extant literature on DDs and violence and found it is limited to case study reviews. The present study addresses this gap through assessing 6-month criminal justice involvement among 173 individuals with DDs currently in treatment. We investigated whether their criminal behavior is predicted by patient self-reported dissociative, posttraumatic stress disorder and emotion dysregulation symptoms, as well as clinician-reprted depressive disorders and substance use disorder.

Past 6 month criminal justice involvement was notably low: 13% of the patients reported general police contact and 5% reported involvement in a court case, although either of these could have involved the DD individual as a witness, victim or criminal. Only 3.6% were recent criminal witnesses, 3% reported having been charged with an offense, 1.8% were fined, and 0.6% were incarcerated in the past 6 months. No convictions or probations in the prior 6 months were reported. None of the symptoms reliably predicted recent criminal behavior.

Conclusions

In a representative sample of individuals with DDs, recent criminal justice involvement was low, and symptomatology did not predict criminality. We discuss the implications of these findings and future directions for research.

Stereotypes abound in the media regarding violent behavior and crimes among those with mental illness. One need not look further than popular crime television shows, the latest blockbuster film or news stories on perpetrators of atrocities such as school shootings or terrorist attacks. Researchers have worked to unpack the complex question of what role mental illness plays in violence, if any, especially in light of mass shootings in the United States at Sandy Hook Elementary, Virginia Tech University and Pulse Nightclub, among others. Researchers generally agree that there is some relationship between mental illness and the risk for violence, such that mental illness increases the risk for violence perpetration as well as victimization, but there is less consensus on the specific psychopathology and symptoms that contribute to violence.

A brief literature review on mental illness and violent behavior

Stereotypes about mental illness and violence are common among the general public. Link, Phelan, Bresnahan, Stueve and Pescosolido [ 1 ] presented a large sample ( N = 1444) with vignettes of people with mental illness, in which no violent behavior or thoughts were described, and inquired how likely it was that the “patient” would be violent. Many participants believed it likely that the hypothetical mentally ill individual would perpetrate violence: 17% of respondents endorsed violence as likely among those with minor interpersonal problems, and 33% and 61% thought violence was likely among people with major depression or schizophrenia, respectively. Individuals with mental illness are frequently aware of others’ negative perceptions of them, which can worsen isolation, negative affect and treatment adherence [ 2 , 3 ].

Individuals with psychological disorders that are highly stigmatized and misunderstood, such as schizophrenia, borderline personality disorder (BPD) and dissociative identity disorder (DID), often face harmful and inaccurate stereotypes which portray them as dangerous and untreatable menaces who require psychiatric or forensic institutionalization. However, as we will review in this study, it is a myth that individuals with DID are the most likely patients in the mental health system to be violent. Various methodologies have been used to study the link between mental illness and violence including: reporting on the prevalence of mental illness among convicted violent offenders, typically homicide defendants; examining violent behavior and crime among clinical populations; and assessing prevalence of violent behavior and crime among those with mental illness in the general population (see Tables 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 and 5 below for the results of studies utilizing each of these methodologies). Many studies examine only violence perpetration, but some examine victimization as well [ 4 – 6 ] (Table 1 ).

In research on the prevalence of mental illness among violent offenders, multiple studies have found the highest rates of violence among individuals with substance use disorders, rather than schizophrenia, BPD and other psychotic disorders [ 7 – 11 ] (Tables 2 and 3 ). Rates of substance use disorders (including alcohol use disorders and illicit substance use disorders) among self-reported violent offenders range from 20 to 42% [ 7 , 11 , 12 ] (Table 2 ). Rates of substance use disorders among convicted homicide offenders are lower but still noteworthy, ranging from 1 to 20% [ 8 , 9 , 13 , 14 ] (Table 3 ).

Other studies have approached the question of how mental illness intersects with violence through examining rates of violent behavior among clinical populations. These studies tend to focus on severe/serious mental illness (SMI), that is, disorders which cause or are associated with serious functional impairment or limitations on major life activities [ 15 ]. The majority of studies on violent behavior among SMI patients focus on schizophrenia, although some also include other SMIs such as bipolar disorder and antisocial personality disorder (Table 4 ). Studies on violent behavior and homicide among individuals with schizophrenia indicate these individuals are at increased risk for both violence perpetration and victimization, but that violence is often predicted by comorbid substance use, medication noncompliance and a recent history of being assaulted [ 16 – 18 ]. Studies on violent behavior among individuals with BPD indicate that emotion dysregulation is a longitudinal mediator of violent behavior and may be a primary mechanism that increases risk for violence in this population [ 19 , 20 ]. The complex DDs, including DID, have been conceptualized as disorders of emotional dysregulation and are often highly comorbid with BPD [ 21 ]. The association of emotion dysregulation with violence in DDs should be further examined.

Dissociative disorders and violent behavior

Notably missing from almost all studies on the intersection of mental illness and violent crime are individuals with dissociative disorders (DDs), including DID and DD not otherwise specified (DDNOS in DSM-IV)/other specified DD (OSDD in DSM-5). This is true of mixed clinical population studies [ 22 – 25 ], studies on violence and mental illness in the general population [ 7 , 11 , 12 , 26 ], as well as forensic studies of convicted violent offenders [ 8 , 9 , 13 , 14 , 27 ]. Although DID is missing from almost all the research on mental illness and violence, it gets an inordinate amount of focus in films about mental illness, particularly those in the horror and thriller genres such as Split , Psycho, Fight Club or Secret Window which portray people with dissociative self-states as prone to violence including homicide, or within comedies that poke fun at the “outlandishness” of dissociative self-states, such as Me, Myself and Irene. Given the paucity of research on violent behavior among individuals with DDs, coupled with the saturation of stereotypic portrayals of DDs in the media, misunderstanding abounds regarding what role dissociation plays in violent behavior, if any.

A few studies have examined dissociative symptoms, rather than DDs, as a predictor of violent interpersonal behavior within mixed clinical populations (Table 4 ). They typically focus on trait dissociation, that is, chronic and enduring dissociative experiences across multiple contexts [ 28 ], compared to state dissociation, e.g., transient, not enduring and time-limited dissociative experiences [ 29 ], the latter of which are often anecdotally reported by violent offenders, such as amnesia for a violent episode and violence-related dissociative episodes [ 30 ]. Quimby and Putnam [ 31 ] found that among adult psychiatric inpatients, trait dissociation was positively correlated with patient sexual aggression via staff reports. Kaplan and colleagues [ 32 ] found a positive correlation between trait dissociation and patient-reported general aggression among psychiatric outpatients. Dissociation has also been posited to play a role in the intergenerational transmission of domestic violence: grouping young mothers who were survivors of childhood maltreatment based on whether or not they abused their own children, Egeland and Susman-Stillman [ 33 ] found significantly greater trait dissociation among mothers who were abusive as compared to those who were not.

A number of case study reviews, conducted nearly three decades ago, reported high rates of violent behavior among patients with DID, according to reports by their treating clinicians [ 34 – 38 ] (Table 5 ). These studies were typically conducted with small samples derived from the authoring clinician’s case load, relied on clinician reports rather than patient self-report, utilized adult lifetime reporting timeframes rather than specified time frames (the latter is more typical of current studies on violence and mental illness), and did not attempt to objectively verify violent behavior through criminal records or other official documentation. Many studies inquired about DID patients’ violent and/or homicidal dissociative self-states. Footnote 1 Therapists reported that between 33 and 70% of DID patients had violent self-states [ 34 – 37 ]. At times, aggressive self-states within individuals with DID threaten other self-states, which some patients perceive to be internalized homicidal ideation and/or threats, but if carried out, would result in suicide and not homicide. Some of the studies reviewed above did not distinguish violent self-states who were violent towards the individual themselves versus those who were externally violent toward others [ 34 – 36 ]. Putnam and colleagues [ 37 ] make the distinction that while 70% of those with DID had violent or homicidal self-states, 53% of the aggressive self-states were “internally homicidal,” that is, with homicidal ideation toward another self-state. Some DID patients may misperceive these internally aggressive self-states as external violent people, rather than the patient being self-destructive or suicidal [ 39 ]. Putnam and colleagues [ 37 ] describe internalized homicidal behavior as occurring among 53% of their 100 DID patient sample. Some DID patients may also experience flashbacks of past violence perpetrated by another person against them and mistakenly believe they are perpetrating violence against someone else when in fact they are experiencing an intrusive recollection of the past [ 39 ].

Within these aforementioned case studies, clinicians reported that 38–55% of their DID patients had a history of any violent behavior [ 34 , 36 – 38 ]. Ross and Norton [ 38 ] reported that of 236 DID patients, 29% of the males and 10% of females reported being convicted of a crime, and the same percentage reported a history of incarceration. While the type of conviction and reason for incarceration were not specified, Ross and Norton [ 38 ] describe more antisocial behavior among men than women. Loewenstein and Putnam [ 36 ] and Putnam and colleagues [ 37 ] report high rates of sexual assault perpetration among their DID patient samples. Among an all-male sample, Loewenstein and Putnam [ 36 ] reported 13% of patients reported having perpetrated a sexual assault, while in a predominately female sample, Putnam and colleagues [ 37 ] reported 20% of patients reported having perpetrated sexual assault. Lewis, Yeager, Swica, Pincus and Lewis [ 40 ] reported severe childhood maltreatment and adult psychopathology among 12 DID inmates who were incarcerated for homicide. Two studies found 19% of DID patients had completed homicide [ 36 , 37 ]. Loewenstein and Putnam [ 36 ] attribute this extremely high rate of violent behavior to the childhood maltreatment these patients experienced which increases their risk for aggression and violence, as well as their reliance on an all-male sample, who have higher rates of violence. Alternatively, Putnam and colleagues [ 37 ] describe confusion about “personified intraphysic conflicts” among the patients leading to misperceptions about the degree of actual violence among DID patients, as described above.

These numbers are concerning, but they are not consistent with more recent studies of DD patients and clinicians that utilize different sampling techniques and designs. Within the international prospective Treatment of Patients with DD (TOP DD) Network Study, only 2% of clinicians and 4–7% of patients report that DD (including both DID and DDNOS/OSDD) patients perpetrated sexual coercion or sexual assault toward a partner in their adult lifetime [ 41 ]. Additionally, rates of perpetration of intimate partner violence were low among DD patients, according to therapists: only 3.5% of DD patients were reported by their TOP DD therapists as having perpetrated physical or sexual abuse toward a partner in their adult lifetime [ 6 ].

To date, no studies have examined the variables that might contribute to violence and/or criminal behavior among individuals with DDs. Given the important role that emotion dysregulation has had in predicting violence among individuals with BPD, emotion dysregulation should be examined as a possible contributing factor among individuals with DDs. Dissociative and PTSD symptoms may also be associated with violence or criminal behavior due to the possibility that when highly symptomatic, individuals with DDs may be overwhelmed and unable to manage their symptoms such that they become vulnerable to dyscontrol. Lastly, potential psychological comordities to DDs related to violent behavior within the literature, such as mood and substance use disorders, should be examined as potential explanatorty variables for recent criminal justice involvement.

The present study

Many questions remain regarding what role mental illness plays in violence. Are mentally ill individuals more likely to perpetrate violence compared to people who do not have mental illness? What psychiatric diagnoses are most highly associated with violent behavior and crime? Are individuals with DDs particularly likely to engage in violent and/or criminal behavior? The present study attempts to provide evidence on violent behavior and crime among individuals with DDs engaged in outpatient treatment.

The purpose of our study was threefold; first, to provide a review of the extant literature on DDs and violent behavior; second, to describe the prevalence of recent criminal justice involvement among a sample of treatment-engaged individuals with DDs; and third, to assess symptomatic predictors of violent behavior and crime among individuals with DDs, including dissociative, emotion dysregulation, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depressive symptoms, as well as problematic substance use. We hypothesized that crime rates would be low in our sample of individuals with DDs, with the majority of patients reporting no recent criminal history or involvement with the criminal justice system, unless their involvement was as victims of crime. Additionally, we hypothesized that the aforementioned symptoms (dissociation, emotion dysregulation, PTSD, depression and substance use) would not be significantly associated with recent criminal behavior and justice system involvement.

Overview and recruitment

Clinician and patient participants were recruited through the Treatment of Patients with Dissociative Disorders (TOP DD) Network study. The TOP DD Network study is a longitudinal educational intervention study of patients with DDs who are diagnosed with either DID or DDNOS/OSDD. Over the course of 1 year, patients and clinicians watched weekly 7–15 min psychoeducational and skills training videos and completed written reflection and behavioral exercises. Additionally, therapist and patient participants completed surveys every 6 months (at baseline, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months) that provided additional clinical and behavioral data.

Clinicians were recruited through listservs for mental health professionals, professional trauma conferences and emails to participated in the first TOP DD study [ 42 , 43 ]. Clinicians were asked to enroll as a dyad with one DD patient from their caseload. All clinician and patient participants completed a voluntary consent process, and the study was approved by the Towson University Institutional Review Board. Eligibility requirements for patients in the TOP DD Network study included a DD diagnosis (DID, DDNOS or OSDD); being in treatment with their current clinician for at least 3 months prior to starting the study; reading English at an 8 th grade level; being willing to continue in individual therapy and complete approximately 2 ½ hours weekly of study activities; and being able to tolerate references to trauma, dissociation and safety struggles.

Participants

The total TOP DD Network study included 242 patients who completed baseline measures, presented after the screening measures which verified study eligibility. TOP DD Network study patient participants were majority female (88.6%), Caucasian (82.1%), middle-aged ( Median = 41), highly-educated (50.9% had at least a college diploma), and primarily resided in the United States (42.3%), although the study recruited internationally with a sizeable portion derived from Norway (27.5%) as well as other countries (30.2%). About half of participants (55.2%) were either in a dating or married relationship. Patients were primarily diagnosed by their therapists as having DID (63.4%). Clinician participants were primarily female (80%) and Caucasian (91.3%). Most reported years of experience as therapists ( Median = 15), as well as in treating trauma ( Median = 13), and dissociation ( Median = 8). Clinicians primarily worked in private practice (81.1%) or in an outpatient clinic or hospital (41.6%).

Patient measures

Criminal justice involvement.

DD patients were asked about involvement with the criminal justice system in the last 6 months including contact with the police, charges, convictions, court cases, fines, incarceration, probation, referral to mental health through the criminal justice system, and serving as a criminal witness. Participants could respond yes or no to these questions. Clinicians were not asked about their patients’ recent criminal justice involvement.

Trait dissociation

Trait dissociation was measured at baseline by the Dissociative Experiences Scale-II (DES) [ 28 ]. DES is a 28-item, 10-point scale (ranging from 0 to 100% of the time) where the participant indicates what percentage of the time a particular dissociative experience occurred within the past month. A meta-analysis by van Ijzendoorn and Schuengel [ 44 ] demonstrated test-retest reliability of .78–.93, α = .93, and convergent validity of r = .67. The measure was scored by adding the item frequency values and dividing by the total number of items, yielding an average summary score for each participant.

- Emotion dysregulation

Emotional dysregulation was measured at baseline by the Difficulties with Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) [ 45 ]. DERS is a 36-item, 5-point scale (ranging from almost never [0–10% of the time] to almost always [91–100% of the time]) where the participant indicates what percentage of the time a particular difficulty with emotion regulation applies to them. The DERS has six subscales encompassing difficulties with accepting emotions, goal-directed behavior, impulse control, as well as lack of emotional awareness, emotional clarity and emotion regulation strategies. Gratz and Roemer [ 45 ] reported α > .80 for the six DERS subscales, while Mitsopoulou, Kafetsios, Karademas, Papastefanakis & Simos [ 46 ] demonstrated a test-retest reliability ranging from .63 to 81 for the six DERS subscales. The measure was scored by summing the item frequency values.

Posttraumatic stress disorder

PTSD symptomatology and severity was measured with PTSD Checklist-Civilian (PCL-C) [ 47 ]. The PCL-C is a 17-item, 5-point scale (ranging from not at all to extremely) where a participant indicates how often they have experienced a particular PTSD symptom within the past month. A total score of 50 points is the typical cutoff indicating a possible PTSD diagnosis [ 48 ]. Weathers and colleagues [ 47 ] reported a test–retest reliability of .96 with a retest interval of 2 to 3 days [ 47 ]. The measure was scored by summing all items together.

Depressive disorders were assessed by having clinicians report whether their patient currently had a diagnosis of either dysthymia or major depression (yielding answers of yes or no). Major depressive disorder and persistent depressive disorder (e.g., dysthymia) were assessed as potential predictors of criminal behavior.

Substance use

Substance use disorders were assessed by having clinicians report whether their patient currently had a diagnosis of a substance use disorder (differentiated from a substance/medication-induced mental disorder; answers were yes or no.)

Binary logistic regression was utilized to assess symptomatic predictors of recent criminal justice involvement in individuals with DDs. Logistic regression was chosen because it predicts membership for a dichotomous dependent variable (i.e., criminal justice involvement) from multiple independent variables, and is appropriate in cases of unequal group sample sizes. We ran eight separate logistic regressions to assess symptomatic predictors of each of the eight criminal justice involvement variables. We report Nagelkerke R squared effect sizes on the significant omnibus models. We adjusted alpha levels to account for multiple hypothesis testing, and the critical p -value = 0.0062. The sample size for the logistic regression models was N = 125, as variables were used from both clinician and patient surveys, and both pre-baseline screening and baseline surveys, which each contained slightly different sample sizes.

Prevalence of recent criminal justice involvement

Among 173 DD patients, 12.7% reported contact with the police within the last 6 months; the reasons for this contact were not queried. The patients reported low rates of recent criminal behavior in the last 6 months (Table 6 ): 4.8% reported involvement in a court case, although it is unknown what role the patient played in the court proceedings (e.g., witness, victim, alleged criminal); 3.6% were witnesses in a criminal case; 3% reported a legal charge; 1.8% reported a fine (s); 1.2% reported a criminal justice mental health referral; and 0.6% reported having been incarcerated. None of the 173 DD patients reported convictions or probation during the most recent 6 months.

Regarding the nature of criminal justice involvement, patients had the option of explaining criminal justice involvement they labeled as “other.” Eight individuals elected to complete the “other” open text box, indicating the following: calling the non-emergency police due to loud neighbors; reporting a substance abusing child to the police; reporting criminal offenses; participating in divorce court and domestic violence orders; receiving a traffic ticket; “[meeting] with secret service;” reporting a suspicious vehicle; and being admitted to the hospital with police involvement.

Symptomatic predictors of criminal justice involvement

Within binary logistic regressions assessing symptomatic predictors of eight types of recent criminal justice involvement, symptomatology significantly predicted recent contact with police, χ 2 (6) = 13.28, p < .05, Nagelkerke R 2 = 0.17. Post-hoc tests indicated that only PTSD symptoms (via the PCL-C) significantly predicted recent contact with police, p < .01. However, after applying the critical p -value = 0.0062, neither the omnibus model nor the post-hoc tests remained significant.

Symptomatology also significantly predicted recent contact with the court system, χ 2 (6) = 26.18, p < .001, Nagelkerke R 2 = 0.59. Post-hoc tests indicated that PTSD symptoms (via the PCL-C) significantly predicted recent contact with the court system, p < 01, as well as a substance use disorder diagnosis (via clinician report), p < .01. However, after applying the critical p -value = 0.0062, the post-hoc tests did not remain significant.

The present study had three aims: first, to provide a review of the extant literature on DDs and violent behavior; second, to describe the prevalence of recent criminal justice involvement among a sample of treatment-engaged individuals with DDs; and third, to assess symptomatic predictors of recent criminal justice involvement within the DD sample.

As we hypothesized, criminal justice involvement among individuals with DDs within the prior 6 months was low, according to patient self-reports. Specifically, patients reported the following in the prior 6 months: 4.8% were involved in a court proceeding, 3.6% were witnesses in a criminal case, 3% had a legal charge, 1.8% received a fine (s), 1.2% received a criminal justice mental health referral, and only 0.6% had been incarcerated. None of the DD patients reported convictions or probation during the past 6 months. This contrasts with prior case study reviews of DID patients in which clinicians reported a history of violent behavior among 29–55% of DID patients, and severely violent crime (e.g., homicide and sexual assault) among upwards of 20% of patients [ 34 , 36 – 38 ]. While the prior studies assess lifetime rates, as compared to the present study’s 6-month time frame, and relied on clinician reports rather than patient self-reports, the inconsistencies are instructive. The contrasting results may mean that as sampling and assessment techniques develop, research on individuals with DDs will increasingly suggest they are not as prone to violence or crime as initially thought, as violence towards self may have been conflated with violence towards others. Individuals with DD seem to pose a greater threat to themselves then to anyone else, as reflected in their very high rates of self-injurious behavior and frequent suicide attempts [ 42 , 43 , 49 ].

Additionally, our hypothesis that symptoms of emotion dysregulation, dissociation, PTSD, depression (major depressive disorder and persistent depressive disorder), and substance use disorder were not associated with criminal justice involvement in our sample was supported. Out of eight different types of recent criminal justice involvement, symptoms were able to significantly predict only DD patients’ recent contact with police, as well as recent court involvement, but the former omnibus model did not remain significant after applying the critical alpha which adjusted for Type I error due to multiple hypothesis testing. Regarding recent court involvement, PTSD symptoms and substsance use disorder symptoms significantly predicted recent court involvement, but again, these post-hoc tests did not remain significant after applying the critical alpha. Thus, no symptoms reliably predicted criminal behavior among those with DDs. More importantly, dissociative symptoms did not significantly predict any type of criminal justice involvement among our sample of DD patients. This counters the notion that dissociative symptoms increase risk for criminal and violent behavior. It is also possible that given the high level of dissociation and PTSD among our sample, the strength of the relationships could have been attenuated due to a ceiling effect.

Our study’s major limitations concern selection bias and the nature of data available on patients’ criminal justice involvement. First, our participants are in psychotherapeutic treatment and thus may not be representative of those with DDs who do not present to treatment, nor of those in the criminal justice system who have DDs and dissociation. Additionally, by definition, our sample experience severe and chronic trait dissociation, but some criminal behavior may be more related to state dissociation [ 29 , 30 ]. Second, our data on patients’ criminal justice system involvement was limited: we did not collect clinician reports of patients’ recent criminal justice involvement, details regarding the nature of patients’ recent criminal justice involvement (i.e., our data on police contact and court cases are ambiguous as to whether they indicate possible criminal behavior or being involved as a witness or victim), nor data on lifetime criminal justice involvement. Many studies on mental illness and violent behavior use lifetime rates, and thus this would facilitate comparisons across studies.

Using patient self-reports of criminal justice involvement in the present study may have provided more accurate responses than only using clinician reports, as it is possible that patients would not report criminal behavior to their clinicians due to social desirability concerns and taboos around criminality, although clinician reports would have been a useful adjunct to patient self-reports. Future studies should review criminal justice records for this population because lifetime memories can be difficult to accurately solicit due to amnesia, and due to the confusion some patients may experience between past and present as well as internal versus external events [ 39 ]. Future studies should assess both lifetime and recent criminal justice involvement, utilizing clinician reports and criminal justice records in addition to patient self-reports.

Studies on psychopathology and violent behavior should include DD individuals in their samples. Small forensic studies have assessed DDs in violent offenders [ 40 ] but larger epidemiological studies of violent offenders have not included DDs, despite assessing a range of psychopathology among offenders [ 7 – 9 , 11 – 14 , 26 , 27 ].

In summary, recent criminal justice involvement among our DD clinical sample is low, according to patient self-reports and is not predicted by dissociative, PTSD or emotion dysregulation symptoms, nor by clinician reported substance abuse disorders or mood disorders. This provides compelling evidence contradicting public and media misconceptions and stereotypes of those with DDs as highly prone to criminality and violence. Public awareness about DDs needs to improve through thoughtful and accurate portrayals of DD, as well as all mental illnesses, in media and literature so that stereotypes and stigma are replaced with understanding and scientifically based knowledge. Enduring stigmas portraying those with mental illness as violent may have considerable negative impacts on their treatment engagement, ability to seek out social support, and overall quality of life [ 2 , 3 ]. Reductions in stereotypes and stigma will allow those with mental illness to live more comfortably and safely and allow the general public to also be less fearful and more compassionate towards those with DDs and all forms of mental illness.

Sometimes referred to as personalities, identities or parts.

Abbreviations

Borderline personality disorder

- Dissociative disorders

Dissociative disorder not otherwise specified

Difficulties with Emotion Regulation Scale

Dissociative Experiences Scale

Dissociative identity disorder

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

Other specified dissociative disorder

PTSD Checklist-Civilian

Severe mental illness

Treatment of Patients with Dissociative Disorders Network Study

Link BG, Phelan JC, Bresnahan M, Stueve A, Pescosolido BA. Public conceptions of mental illness: Labels, causes, dangerousness, and social distance. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1328–33.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gonzales L, Davidoff KC, Nadal KL, Yanos PT. Microaggressions experienced by persons with mental illnesses: An exploratory study. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2015;38(3):234–41.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Stuart H. Media portrayal of mental illness and its treatments: What effect does it have on people with mental illness? CNS Drugs. 2006;20(2):99–106.

Crisanti AS, Frueh BC, Archambeau O, Steffen JJ, Wolff N. Prevalence and correlates of criminal victimization among new admissions to outpatient mental health services in Hawaii. Community Ment Health J. 2014;50(3):296–304.

Teplin LA, McClelland GM, Abram KM, Weiner DA. Crime victimization in adults with severe mental Illness: Comparison with the National Crime Victimization Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(8):911–21.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Webermann AR, Brand BL, Chasson GS. Childhood maltreatment and intimate partner violence in dissociative disorder patients. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2014;5:1–8.

Article Google Scholar

Elbogen EB, Johnson SC. The intricate link between violence and mental disorder: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(2):152–61.

Fazel S, Grann M. Psychiatric morbidity among homicide offenders: A Swedish population study. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(11):2129–31.

Flynn S, Abel KM, While D, Mehta H, Shaw J. Mental illness, gender and homicide: A population-based descriptive study. Psychiatry Res. 2011;185(3):368–75.

González RA, Igoumenou A, Kallis C, Coid JW. Borderline personality disorder and violence in the UK population: Categorical and dimensional trait assessment. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:1–10.

Swanson JW, Holzer CE, Ganju VK, Jono RT. Violence and psychiatric disorder in the community: Evidence from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area surveys. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1990;41(7):761–70.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Coker KL, Smith PH, Westphal A, Zonana HV, McKee SA. Crime and psychiatric disorders among youth in the US population: An analysis of the national comorbidity survey–adolescent supplement. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(8):888–98.

Rodway C, Flynn S, While D, Rahman MS, Kapur N, Appleby L, Shaw J. Patients with mental illness as victims of homicide: A national consecutive case series. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(2):129–34.

Simpson AF, McKenna B, Moskowitz A, Skipworth J, Barry-Walsh J. Homicide and mental illness in New Zealand, 1970–2000. British J Psychiatry. 2004;185(5):394–8.

Behavioral health trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 15–4927, NSDUH Series H-50). Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2015. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FRR1-2014/NSDUH-FRR1-2014.pdf . Retrieved 3 Aug 2016.

Gourion D. Schizophrenia and violence: A common developmental pathway? In: Verrity PM, editor. Violence and aggression around the globe. Hauppauge: Nova; 2007. p. 29–44.

Google Scholar

Swanson JW, Borum R, Swartz MS, Monahan J. Psychotic symptoms and disorders and the risk of violent behaviour in the community. Crim Behav Ment Health. 1996;6(4):309–29.

Walsh E, Gilvarry C, Samele C, Harvey K, Manley C, Tattan T, Tyrer P, Creed F, Murray R, Fahy T. Predicting violence in schizophrenia: A prospective study. Schizophr Res. 2004;67(2–3):247–52.

Newhill CE, Eack S, Mulvey EP. A growth curve analysis of emotion dysregulation as a mediator for violence in individuals with and without borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord. 2012;26(3):452–67.

Scott LN, Stepp SD, Pilkonis PA. Prospective associations between features of borderline personality disorder, emotion dysregulation, and aggression. Pers Disord. 2014;5(3):278–88.

Brand BL, Lanius RA. Chronic complex dissociative disorders and borderline personality disorder: Disorders of emotion dysregulation? Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregul. 2014;1:13.

Bruce M, Cobb D, Clisby H, Ndegwa D, Hodgins S. Violence and crime among male inpatients with severe mental illness: Attempting to explain ethnic differences. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(4):549–58.

Hodgins S, Alderton J, Cree A, Aboud A, Mak T. Aggressive behaviour, victimisation and crime among severely mentally ill patients requiring hospitalisation. British J Psychiatry. 2007;191(4):343–50.

Matejkowski JC, Cullen SW, Solomon PL. Characteristics of persons with severe mental illness who have been incarcerated for murder. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2008;36(1):74–86.

PubMed Google Scholar

Jordan B, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, Caddell JM. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among incarcerated women: Convicted felons entering prison. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(6):513–9.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Crime in the United States, 2014. United States Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation.2015. https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2014/crime-in-the-u.s.-2014/cius-home . Retrieved 3 Aug 2016.

Wilcox DE. The relationship of mental illness to homicide. Am J Forensic Psychiatry. 1985;6(1):3–15.

Carlson EB, Putnam FW. An update on the Dissociative Experiences Scale. Dissociation. 1993;6(1):16–27.

Kruger C, Mace CJ. Psychometric validation of the State Scale of Dissociation (SSD). Psychol Psychother Theory Res Pract. 2002;75:33–51.

Moskowitz A. Dissociation and violence: A review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2004;5(1):21–46.

Quimby LG, Putnam FW. Dissociative symptoms and aggression in a state mental hospital. Diss. 1991;4(1):21–4.

Kaplan ML, Erensaft M, Sanderson WC, Wetzler S, Foote B, Asnis GM. Dissociative symptomatology and aggressive behavior. Compr Psychiatry. 1998;39(5):271–6.

Egeland B, Susman-Stillman A. Dissociation as a mediator of child abuse across generations. Child Abuse Negl. 1996;20(11):1123–32.

Dell PF, Eisenhower JW. Adolescent multiple personality disorder: A preliminary study of eleven cases. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1990;29(3):359–66.

Kluft RP. The parental fitness of mothers with multiple personality disorder: A preliminary study. Child Abuse Negl. 1987;11(2):273–80.

Loewenstein RJ, Putnam FW. The clinical phenomenology of males with MPD: A report of 21 cases. Dissociation. 1990;3(3):135–43.

Putnam FW, Guroff JJ, Silberman EK, Barban L, Post RM. Clinical phenomenology of multiple personality disorder: review of 100 recent cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 1986;47(6):285–93.

Ross CA, Norton GR. Differences between men and women with multiple personality disorder. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1989;40(2):186–8.