- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- African Literatures

- Asian Literatures

- British and Irish Literatures

- Latin American and Caribbean Literatures

- North American Literatures

- Oceanic Literatures

- Slavic and Eastern European Literatures

- West Asian Literatures, including Middle East

- Western European Literatures

- Ancient Literatures (before 500)

- Middle Ages and Renaissance (500-1600)

- Enlightenment and Early Modern (1600-1800)

- 19th Century (1800-1900)

- 20th and 21st Century (1900-present)

- Children’s Literature

- Cultural Studies

- Film, TV, and Media

- Literary Theory

- Non-Fiction and Life Writing

- Print Culture and Digital Humanities

- Theater and Drama

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

The salem witch trials.

- Abram C. Van Engen Abram C. Van Engen Washington University in St. Louis

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.139

- Published online: 22 November 2016

The Salem witch trials have gripped American imaginations ever since they occurred in 1692. At the end of the 17th century, after years of mostly resisting witch hunts and witch trial prosecutions, Puritans in New England suddenly found themselves facing a conspiracy of witches in a war against Satan and his minions. What caused this conflict to erupt? Or rather, what caused Puritans to think of themselves as engaged, at that moment, in such a cosmic battle? These are some of the mysteries that the Salem witch trials have left behind, taken up and explored not just by each new history of the event but also by the literary imaginations of many American writers.

The primary explanations of Salem set the crisis within the context of larger developments in Puritan society. Though such developments could be traced to the beginning of Puritan settlement in New England, most commentators focus on shifts occurring near the end of the century. This was a period of intense economic change, with new markets emerging and new ways of making money. It was also a time when British imperial interests were on the rise, tightening and expanding an empire that had, at times, been somewhat loosely held together. In the midst of those expansions, British colonists and settlers faced numerous wars on their frontiers, especially in northern New England against French Catholics and their Wabanaki allies. Finally, New England underwent, resented, and sometimes resisted intense shifts in government policy as a result of the changing monarchy in London. Under James II, Massachusetts Bay lost its original charter, which had upheld the Puritan way for over fifty years. A new government imposed royal rule and religious tolerance. With the overthrow of James II in the Glorious Revolution, the Massachusetts Bay government carried on with no official charter or authority from 1689 until 1691. When a new charter arrived during the midst of the Salem witch hunt, it did not restore all the privileges, positions, or policies of the original “New England Way,” and many lamented what they had lost. In other words, in 1692, New England faced economic, political, and religious uncertainty while suffering from several devastating battles on its northern frontier. All of these factors have been used to explain Salem.

When Governor William Phips finally halted the trials, nineteen had been executed, five had died in prison, and one man had been pressed to death for refusing to speak. Protests began almost immediately with the first examinations of the accused, and by the time the trials ended, almost all agreed that something had gone terribly wrong. Even so, the population could not necessarily agree on an explanation for what had occurred. Publishing any talk of the trials was prohibited, but that ban was quickly broken. Since 1695, interpretations have rolled from the presses, and American literature—in poems, plays, and novels—has attempted to make its own sense and use of what one scholar calls the mysterious and terrifying “specter of Salem.”

- witch-hunting

- New England

- 17th century

- cultural memory

What Happened in Salem

The fits began in January 1692 . Betty Parris, the minister’s nine-year-old daughter, and Abigail Williams, the minister’s eleven-year-old niece, were the first to be afflicted. As members of the minister’s household, they presented an embarrassing situation. The fits suggested that Satan could make his way even into the pastor’s house, possessing or demonizing beyond the minister’s ability to protect or defend. Moreover, Puritan theology taught that such afflictions usually came as chastisements from God, requiring the minister, Samuel Parris, to examine his ways and repent. Either because of his embarrassment or because he genuinely repented, Parris did not suspect witches for many weeks. He prayed. He fasted. He waited. After more than a month of continued fits, he finally called a doctor. When the doctor pronounced the girls bewitched, it both relieved a burden and added a new one. The girls were not possessed; they were attacked. But who the devil was bewitching them?

Mary Sibley, Parris’s neighbor, knew one way to find out. She ordered Parris’s slaves Tituba and John Indian to bake a witch cake—a rye bread mixed with urine from the afflicted children. This was called white magic, or countermagic, and it was long used and widely practiced in Puritan New England. Though uniformly condemned by the clergy (they believed all magic, for whatever purpose, worked only through the power of Satan), the practice of countermagic continued through the 17th and 18th centuries. Lay people did not necessarily associate magic with the devil, but approached it more pragmatically: if it healed it was good, and if it harmed it was bad.

The witch cake Sibley ordered apparently worked. When the dog ate it, the children identified their tormenters. It also produced collateral damage, however, for the same day the witch cake was baked, two more children fell ill: twelve-year-old Ann Putnam Jr., and seventeen-year-old Elizabeth Hubbard, the doctor’s maid. The four girls collectively named three witches, and Samuel Parris had good reason to be relieved. Now, finally, he could lay the blame elsewhere. Not only were these witches the ones at work, but Sibley’s condemned usage of countermagic had “raised the devil” in Salem. He rebuked Sibley and forced her to confess before the church. Then he used the evidence she procured through countermagic to begin proceedings against the witches.

The first suspects were the predictable ones: Tituba, a slave from the West Indies; Sarah Good, a poor beggar who offended everyone; and Sarah Osborne, a bedridden widow who had scandalized the town by marrying her servant. 1 As many have shown, witch hunts were often directed primarily at women, and especially at poor, marginalized women or those who had transgressed social norms. As Carol Karlsen succinctly writes: “The story of witchcraft is primarily the story of women … Especially in its Western incarnation, witchcraft confronts us with ideas about women, with fears about women, with the place of women in society, and with women themselves. It confronts us too with systematic violence against women.” 2 Salem thus began as a limited witch hunt aimed at notorious women, a ritual that was not very common in New England compared to Europe, but one which certainly had its precedents. The community would purge itself of those who did not fit, and then it would reunite through the process of uncovering and overcoming the devil. 3 The local magistrates, John Hathorne, Jonathan Corwin, and Bartholomew Gedney, presided over the first phase of examinations. Beginning with Sarah Good, Hathorne interrogated the defendants in an attempt to force confessions. Questions led with an assumption of guilt. Rather than asking whether Good injured the four children, Hathorne simply asked why she did. Good claimed her innocence, and each denial of guilt evoked a series of fits from the four afflicted girls. Finally, Good accused Osborne, attempting to shift the blame, but when the magistrates examined Osborne, much the same occurred.

It was when the court finally heard from Tituba that Salem exploded into an unprecedented affair. Under Hathorne’s pressure, Tituba confessed to being a witch, and that confession yielded several dramatic results. First, the afflictions of the girls ceased, confirming that confessions were the best way both to prevent further harm to the girls and to legitimate the actions of the court. Second, Tituba’s confession enabled her to detail the actions of other witches, her supposed accomplices. According to the trusted Puritan theologian William Perkins, a confessed witch who accused others offered valid testimony against them. Tituba explained that Good and Osborne had forced her to harm the girls, and the court believed her. Third, Tituba offered several elements in her confession—all guided by Judge Hathorne—that would become routine in future confessions: the devil’s book, the witches’ meetings, the description of a “black man,” Satanic masses, and the naming of other suspects. 4 Finally, and most significantly, Tituba claimed that Good and Osborne did not act alone. Tituba eventually testified to a total of nine witches, though she could not say who they were. Suddenly, a full witch conspiracy was underway, a war of Satan against the Puritan churches of New England. To survive, the godly would have to unmask their foes. 5

Ann Putnam Jr., took the lead in identifying these other witches, who turned out not to conform to the usual stereotypes. The next accused included Dorothy Good, Sarah’s four-year-old daughter; Martha Cory, a member of Samuel Parris’s church; and Rebecca Nurse, a widely respected matriarch, member of the nearby Salem Town church, and godly grandmother in the community. Meanwhile, the afflicted multiplied. Adults began to suffer fits, including Ann’s mother and Tituba’s husband, John Indian, and the fits spread to Mary Warren, the servant of John and Elizabeth Proctor. John Proctor responded by beating her, which seemed to cure her of the problem, and apparently he proclaimed that if he were left alone with John Indian, he could beat the devil out of him as well. But when Mary recovered and turned against the afflicted, the afflicted turned against her: she was soon accused of witchcraft herself, revealing in its early days how difficult it would be to oppose the supposedly bewitched. 6 Before the judges, Mary claimed that “the afflicted persons did but dissemble.” Fits immediately ensued, so convincing in their performance that Mary reacted with fits of her own and was taken back to prison, unable to speak. In court the next day, Mary confessed to signing the devil’s book, but only because she had been tricked into doing it by the Proctors. Then she accused Giles Cory. She rejoined the ranks of the afflicted and spun out accusations in tandem with them, saving her own life but costing the lives of many more.

With the confession of Abigail Hobbs of Topsfield, who would also soon join the afflicted, the trials turned their attention to Maine. Hobbs claimed to have become a witch in the woods of Casco Bay. All along the Maine frontier, the English Puritans were losing in a long war against the French and their Wabanaki allies. Wabanaki raids repeatedly wiped out Puritan towns, and several of the afflicted girls were orphans and refugees from the conflict. With Maine’s woes now present in the courtroom, accusations focused on the former Salem minister who had moved back to that frontier: George Burroughs. Burroughs was a Puritan minister with Baptist leanings who had preached in the divided Salem Village church a decade before; he had a reputation for mistreating wives and an uncanny ability to survive Indian raids. Both aspects made him suspect. At Salem, he became identified as the ringleader of the conspiracy, the minister of an inverted covenant of witches. He presided over black masses and bloody sacraments. He killed wives. He bewitched neighbors. He recruited the formerly godly to war against New England. When the court took up his case, more than thirty witnesses volunteered to damn him.

Until June, the examinations of the accused witches had not been able to proceed to actual trials because the colony lacked an official charter and an ability to try capital offenses. In June, the newly appointed governor, William Phips, arrived from England with a new charter, heard about the crisis in Salem, and immediately established a Court of Oyer and Terminer (“to hear and determine”). Stocked with high-ranking officials from Boston, this court could move from the initial depositions, testimonials, and examinations to grand jury indictments and finally jury trials. The court first tried Bridget Bishop on June 2. Bishop denied her guilt, which would prove a good way to die in Salem. The trial proceeded quickly, and on June 10, she was hanged.

At that point, Salem paused. Accusations and examinations had swept up a series of accused witches, mostly from Salem Village and its immediate vicinity. But now it had executed its first witch, a woman who disconcertingly refused to confess even on the scaffold. Before proceeding, the magistrates wanted some approval from Puritan ministers. Asked for their thoughts on the matter, several prominent ministers took two days to respond. Their response, “The Return of Several Ministers,” suggested caution, especially in the use of “spectral evidence” (seeing someone’s specter, or shape, harming either oneself or another). The strange use of spectral evidence—the claims of the afflicted to see, experience, know, and testify about the invisible world, along with the court’s reliance on such testimony to suspect, convict, and execute the accused—would become one of Salem’s most anomalous mysteries. The judges at Salem approached spectral evidence in direct violation of precedent and principle. Yet although “The Return of Several Ministers” urged caution in this regard, it did not overtly condemn the proceedings or the judges and ended by encouraging a “vigorous prosecution.” It was all the court wanted to hear. Ignoring all other ambiguities and cautions, the court pressed on, turning its attention in a second phase of trials from Salem Village to the nearby town of Andover, where a great number of accused persons quickly confessed—many doing so explicitly to save their lives. 7

The suffering of the accused did not begin with that first hanging of Bridget Bishop. It began rather with the accusation itself, the taint of dark magic and ungodly ways, the loss of reputation. For those like Rebecca Nurse, who was a church member, the suffering continued with an official excommunication before execution. And suffering extended elsewhere as well, to the forfeiture of property and constrained conditions for surviving children, and to the prisons, which were wretched, unsanitary, overcrowded, and dangerous. The first to die at Salem was not Bridget Bishop but Sarah Osborne, the bedridden widow, who perished in jail a month before her case could even be heard. In total, nineteen would be executed, one man would be pressed to death between boards, and at least five would die in jail before Governor Phips, under growing opposition, would finally close down the Court of Oyer and Terminer—much to the dismay and indignation of its presiding judge, William Stoughton. Phips created another court to hear the remaining cases, and this second court cleared the jails, refused to accept former confessions, and acquitted all but three. Governor Phips immediately reprieved the convicted three. No one else would die for witchcraft in New England.

Explanations of the Salem Witch Trials

Most scholars agree on the basic narrative of the Salem witch trials. 8 Why it happened, however, is far from clear. Disagreements abound, with alternative explanations for the afflicted, the accused, the judges, the ministers, the magistrates, and the proceedings as a whole. Much about Salem begs for explanation. Not only was the witch hunt larger and more extensive than anything New England had ever seen, but those in authority acted quite differently than had their colleagues in prior cases. Young girls and others had fallen into fits and afflictions before; in fact, almost simultaneously with Salem, the same kinds of fits with the same sorts of accusations were beginning among a small group of girls in Hartford, Connecticut. Yet neither in neighboring Hartford in 1692 nor in the previous six decades did such afflictions lead to stuffed jails and mass executions.

No one has better laid out the full culture of witchcraft in Puritan New England than John Demos, and in the updated version of his book Entertaining Satan , Demos emphasizes two fundamental “themes”: that witchcraft in New England belonged to “the regular business of life in pre-modern times”—a part of the basic functioning of community—and that witchcraft was “a profoundly ‘emotional’ phenomenon (with fear and anger at its center, and lots of affect-laden fantasy flowing out in all directions).” 9 Yet Demos focuses on sporadic witch accusations and trials across New England, not massive witch hunts, and he offers no account of Salem. At Salem, something beyond the regular business of life broke out. What made Salem go so wrong?

Three prominent and overlapping explanations have come to the fore, each emphasizing a particular aspect. One early and influential account laid all the blame on economic development and communal division. In Salem Possessed , Paul Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum saw Salem Village at war with forces of modernization that threatened a close-knit, traditional agricultural society. Mapping the houses of the afflicted against the houses of the accused, they found that most of the afflicted came from the western, more agricultural areas of Salem Village, while the accused tended to come from the eastern, more merchant-oriented society of Salem Town. From this map and other evidence, Boyer and Nissenbaum claimed that the coming of modern capitalism caused irreparable harm to the self-understanding and social fabric of the community, leading to a witch hunt. The cause of the Salem witch hunt was finally the economy, along with all the social factors that economic division and development entails. 10

A second major interpretation puts the primary emphasis on political instability. In 1684 , King James II revoked the colony’s founding charter and imposed a new government with a royally appointed governor named Edmond Andros. Andros was everything the Puritans hated: an autocratic, aristocratic Anglican who ignored the locals’ opinions and advice. When the Glorious Revolution occurred in 1689 , replacing James II with William and Mary, Massachusetts’s colonists jailed Andros and packed him off to England. From 1689 through 1691 , the colony had no charter and thus no official government. During this interim, it returned to the administration of the first charter, waiting for the outcome of negotiations between Increase Mather and the new king and queen. The new charter, which arrived in the midst of the Salem panic, mixed features of the first and second governments. Returning many rights to the Massachusetts citizens, it nonetheless retained a royally appointed governor and still required religious tolerance. Many opposed the charter, and some began to wonder if Puritan New England had run its course. This political instability, some have argued, caused the witch hunt. Salem can be understood as an attempt to reclaim a Puritan New England ideal that was constantly under attack during hated, missing, or compromised governmental charters. 11

Finally, others have seen a similar mentality at work, but from a different cause: New England was under attack, but much more literally. In King William’s War ( 1688–1697 ), New England suffered devastating defeats at the hands of the French and Indians along its northern border. Almost every attempt to mount a counteroffensive failed miserably. Towns were razed, casualties mounted, and captives were taken north and forced into Catholicism. In the guise of his minions, Satan wanted to destroy the godly community, and because of New England’s sins, God was allowing Satan to succeed. No one would be safe without a thoroughgoing reformation. Closer to Salem, these northern wars touched the lives of several participants in the witch hunt: some of the afflicted were war refugees, orphaned and traumatized; some of the accused, especially George Burroughs, had close ties to Maine; and some of the judges were responsible for terrible defeats and financial losses during the wars. Hunting witches allowed the judges to fight Satan on their own turf and win; and for the afflicted—several of whom may have been suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder—Salem might have made them feel that someone was finally taking up their cause. 12

Each of these explanations has been used to make sense of Salem, and all have been found wanting. 13 More recently, scholars have emphasized the role of religion in accounts that combine features from all previous explanations. Even before Mary Beth Norton highlighted the wars of the northern frontier, Richard Godbeer noted them and combined them with several additional factors that served as “a series of external forces assault[ing] the colonists, imperiling not only their integrity as a political and spiritual community but even their very survival.” This “common trauma,” he noted, was often described in the language of invasion and external threat. 14 In Satan and Salem , Benjamin Ray similarly argues that “far from being precipitated by a single key person or circumstance, the Salem crisis was the result of a perfect storm of factors.” 15 That storm of factors, he explains, shared a common language of Satan’s attack. Likewise, Emerson Baker, publishing the same year as Ray, titled his comprehensive account of the crisis A Storm of Witchcraft . This idea of a perfect “storm” emphasizes the coming together of multiple factors. King William’s War certainly matters, as Norton demonstrates; but so do other factors, such as economic instability, the lack of a stable government, the inexperience of a new governor, the past failings of ruling magistrates, and the personalities of Samuel Parris, Thomas Putnam, and many others. Overall, it seems, what mattered most was that New England Puritans, in the midst of these crises—and partly as a result of them—saw themselves as God’s chosen people at war with a newly unleashed and angered Satan. It was a war they wanted to win, and the most self-assured Puritans became convinced that they could win this war by purging the land of all those who allied themselves with Satan and Satan’s cause. They came to see the devil anywhere, and they sought to defeat him everywhere.

The Many Participants in the Salem Witch Trials

Beyond attempting to explain why Salem happened at all, scholars have also sought to examine the particular mysteries of the various groups involved: the afflicted, the accused, the magistrates, and the ministers. These groups often have defining characteristics, though they also divide into their own subgroups (local magistrates vs. Boston magistrates, for example, or the ministers in support of the trials vs. the ministers who opposed them). In addition, there are several individuals who significantly affected Salem: Samuel Parris, the town’s minister; Tituba, the minister’s slave who first confessed; Thomas Putnam Jr., the man whose family seemed particularly afflicted and whose depositions were especially successful against the accused; Governor Phips, who supported the trials, then closed them down, then tried to claim that he never knew what was happening; Increase Mather and his son Cotton, the prominent Boston ministers who divided over Salem while trying to make it appear as though they actually agreed. These personalities and groups have all received their own attention as important factors at Salem.

Salem begins with the afflicted: there are no trials without the seizures, screams, and fits. These afflictions began with young girls who would remain the core group of the afflicted, but they spread to a host of others, including males and adults (such as John Indian and Ann Putnam, Sr.). What explains the bewitched? A variety of notions have been advanced, and the only one consistently refuted has been the one that dominates popular imagination: ergot poisoning. According to this idea, the afflicted consumed a fungus that grows on moldy rye bread, causing symptoms similar to those of LSD. All scholars rule out this possibility. Much more likely is that the girls simply faked it. The very evidence that rules out ergot poisoning—the intervals of affliction, the lack of serious harm to the afflicted, and the idea that these afflictions seemed to be able to start and stop on command—suggests the possibility of fraud. All scholars agree that at least some fraud was involved, and certain members of the afflicted group, such as Mary Warren, seem particularly suspect. The Proctors’ servant ceased having fits, faced an accusation of witchcraft, became “afflicted” all over again, then laid the blame on the Proctors. Such survival strategies seem to indicate clear cases of fraud. 16

At the same time, the kinds of stress Mary endured could cause mental breakdowns that might blur the lines between fraud, fatigue, and fear. If friends, family members, respected ministers, and magistrates all believe that you are tormented by specters, at what point do you begin to believe them? So, too, hysteria can be contagious. Is it fraud to fall when others fall, or fear when others fear? Such lines can sometimes be hard to draw. As Emerson Baker usefully points out, cases of contagious fear, anxiety, and hysteria have broken out in modern times as well, even as recently as 2011 in New York public schools amid teenage girls who suffered symptoms quite similar to those of Salem. 17 The afflictions at Salem may have begun as genuine symptoms of anxiety or PTSD; at court, these fits might have continued as fraud, especially when the magistrates required repeat performances of affliction to convict the accused. 18

As for the accused, how did their names come to the afflicted? The first three names make sense: they fit the usual description of witches. But once witchcraft expanded to church members and Puritan ministers, does any rationale explain how one person came to be accused while another person escaped? Theories abound, beginning primarily with the economic disparities proposed in Salem Possessed , but most recent scholarship settles on the idea of religious division within the community. When the witch hunt began in Salem Village, the afflicted came primarily from families who supported Samuel Parris, and the accused came primarily from families who opposed him. As the witch hunt passed on from Salem Village to surrounding communities, accusers seemed to seek out those who were religiously corrupt in some way—those who failed to attend church regularly, who did not participate in sacraments, who failed to become full members of a church, or who had some kind of connection to Quakers, Baptists, or other religious dissidents. This religious rationale does not explain all accusations, but it seems to make the most sense of identifying the accused.

When the accused stood before the court, they came into the presence of another influential group: the judges. It is one thing for young girls to become afflicted and accuse others of witchcraft; it is quite another for court magistrates to believe them and to prosecute almost every name they produced. Recently, attention has turned from the local antagonisms of the afflicted and the accused to the role of the judges and magistrates who seemed to push the trials forward. As Baker has written, “[N]o one would have died without the sanction of the judges. The judges of the Court of Oyer and Terminer hold the answers to many of Salem’s riddles.” 19 These judges have become all the more interesting lately because scholarship has demonstrated just how oddly they behaved. At Salem, magistrates disregarded both precedent and advice. In the previous sixty years of Puritan settlement, there had been sixty-one prosecutions for witchcraft, with at most sixteen convictions and executions, a rate of 26.2 percent. 20 For many years, Puritan magistrates and ministers had prevented the conviction and killing of supposed witches, in part because they had a different understanding of witchcraft than did most commoners. The elite defined the deed as a covenant with the devil; most of the non-elite saw it as a harmful use of magic. Common citizens brought their testimony of harm to magistrates, but harm in itself proved nothing. Successful prosecutions required either a confession or two witnesses to confirm that someone had made a pact with the devil. For sixty years, confessions were hard to come by and pacts with the devil were hard to prove. More important, in the previous several decades of Puritan New England, ministers and magistrates were decidedly uneasy about spectral evidence; it could identify a potential suspect , but it could never be used to convict. At Salem, spectral evidence convicted. It was relied upon as insight into the unknown, as valid testimony of the invisible world. The changed use of spectral evidence would be one of the strangest and most unsettling aspects of Salem, one that informs the work of writers such as Nathaniel Hawthorne and an element that scholars continue trying to explain. 21 But spectral evidence was not the only anomaly. New England law had previously limited accusations of witchcraft and other crimes by requiring the posting of a bond; in order to curtail frivolous cases, people had to pay money in order to lodge a case with the court. At Salem, that requirement was dropped. As a result of the conditions surrounding witchcraft before Salem, not only were there fewer complaints made in previous decades, but those complaints were far less successfully prosecuted. For sixty years, commoners and lay people had pressed for the conviction of witches, and for just as many years their political and religious superiors had pressed back even harder. 22

At Salem, all of these precedents would be ignored or reversed. Bonds were not required for many months, swelling the number of complaints. Confessions, some of which were produced by illegal torture, saved the lives of those who confessed. Those doomed by their denials of guilt, meanwhile, were often convicted almost exclusively on the basis of spectral evidence. As the accused protested their innocence, the afflicted girls would fall, twist, scream and writhe, pointing to an invisible tormenter. Since all could see the torment itself, two witnesses of witchcraft were not required—assuming, that is, that one could trust the spectral evidence. The court ignored the tomes on witchcraft that previous courts so carefully studied. Rather than tamping down and resisting the common people’s desire for prosecution, the magistrates at Salem accepted and encouraged it. Where the conviction rate hovered just above 26 percent in previous decades, the rate at Salem would be 100 percent. 23 No one who came to trial would be acquitted. As one scholar aptly explains, “It is hard to avoid the conclusion that for whatever motives, the Salem judges wanted convictions.” 24

Why did the judges want convictions? Political instability may offer some psychological rationale for the behavior of court judges: several of them had worked for Andros’s hated government, and some had been involved in the defeats of King William’s War. Perhaps these judges needed a way to prove they were on the side of godly Puritans, while also finding a conspiracy of witches to be a handy excuse for their failures. 25 Religious tensions and perhaps a sense of spiritual unworthiness among these second-generation stalwart Puritans may also play a role: five of the nine judges had attended Harvard College in preparation for the ministry, but all had abandoned that path for other pursuits. In addition, as Baker reveals, these judges were mostly related to each other through marriage. The only unrelated judge was Nathaniel Saltonstall, and Saltonstall was the only judge to resign from the court in protest. 26 Yet it is important to realize that all the judges seemed to have been transformed at Salem: several had been involved previously in acquitting accused witches, questioning the spectral evidence they would come to rely upon at Salem. Why they suddenly sought convictions is difficult to determine, but if the judges had not so desperately wanted the prosecution to succeed, the witch hunt could never have taken off. For whatever reason, the magistrates must have had a great deal to gain in 1692 .

While the judges may have suffered from paranoia and guilt about the wars or their involvement in Andros’s government, on a more local level, the afflicted, their parents, and the prosecutors all seemed to dwell in a paranoid, anxious, and traumatized community. The records of the Salem witch trials are an endless testimony of suffering. Loss, despair, anxiety, and sorrow pour out of the testimonies. 27 And all of that heartache could finally be given an object, a scapegoat—someone to blame. Without witchcraft, all these losses would register as afflictions requiring repentance; but with witches to blame, the guilt could be alleviated. Rather than losing children because of one’s sins, such losses could be understood as Satan’s attack, possibly launched against someone precisely because that person had remained faithful to God. Witches, in other words, changed the dynamics and experience of loss.

That may not have been the explicit rationale for many witnesses, but it certainly seems to have guided the thinking of Samuel Parris. Parris, the embattled minister whose children started throwing themselves at open flames, was the fourth pastor of Salem Village. The first three had short tenures, invited by one faction but opposed by another. Few had their salaries paid; all would leave Salem for less than stellar careers; and one, George Burroughs, would be hanged as a witch. Salem Village offered one of the lowest ministerial salaries in the entire colony, and its reputation of bitter factional divisions preceded it. In 1689 , no one with an actual divinity degree could be lured to its parish. Samuel Parris had completed three years at Harvard before leaving to take over his father’s plantation in Barbados, which quickly failed. He tried his hand as a merchant in Boston and failed there, too. Finally, Salem Village asked him to preach. For a year, he wrangled about the terms of his salary, his wood supply, and the ownership of the parsonage. In his first sermon, he demanded that congregants love, serve, and obey him. He told them that by bringing sacraments to the church (allowed for the first time since it was established), he was removing the Lord’s reproach. Then he removed the Halfway Covenant that allowed God-fearing congregants who were not full members to baptize their children. These “halfway” congregants, whom Parris railed against, would either have to become full members by making a profession of faith before the church and undergoing the church’s scrutiny, or they would have to forgo baptizing their children. It was clear from the start that Samuel Parris would not heal this divided church.

The trouble with Parris seems especially evident from his preaching. Parris spoke unambiguously of the good and the bad, the godly and the ungodly, assigning “halfway” God-fearing congregants consistently to the latter category. As scholars have shown, Parris posed no neutral ground: all people were either of God or the devil, and his goal was to parse and separate. 28 Lacking the hesitation and self-doubt of many other Puritan ministers, Samuel Parris often presented himself as a Christ-like figure opposed by anti-Christian forces. From the moment he first began preaching, Parris spoke of cosmic battles. He emphasized Satan’s attack against the godly and interpreted resistance as the diabolical plot of the devil. On the Sunday before the first fits began in his home, Parris preached explicitly that Satan was attempting to “pull down” the church. Frequently, the concerned faction supporting Parris met at his house to discuss the crisis facing the church, strategizing how to deal with all those who opposed him. It makes sense, then, that his house is where the fits began. Without Parris, there would be no context for believing the testimony of the minister’s slave that a conspiracy of witches gathered outside his home and sought to overthrow his church. 29

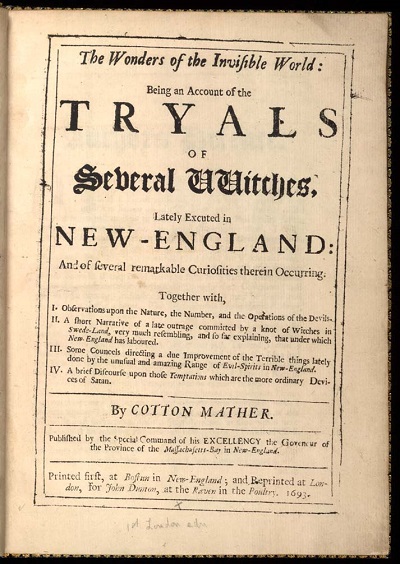

But Parris was not the only Puritan to see Satan at work, gathering forces for a violent battle against godly New England. Nowhere does this perception of war appear more clearly than in the introductory frame of Cotton Mather’s Wonders of the Invisible World ( 1693 ). Written at the behest of the governor, deputy governor, and chief magistrate of the Salem witch trials, this text chooses five cases, selectively presents the evidence, and defends the court in its work for Christ. The overall defense of the court’s actions lay in the broader context the book establishes: “The New Englanders are a people of God settled in those, which were once the devil’s territories,” Cotton Mather explains. Because they brought the gospel to Satan’s lands, Satan had become especially enraged and now pursued a grand plot to destroy the godly society that the Puritans had built. Like Samuel Parris, Cotton Mather’s book couched the Salem witch trials within the context of a cosmic battle.

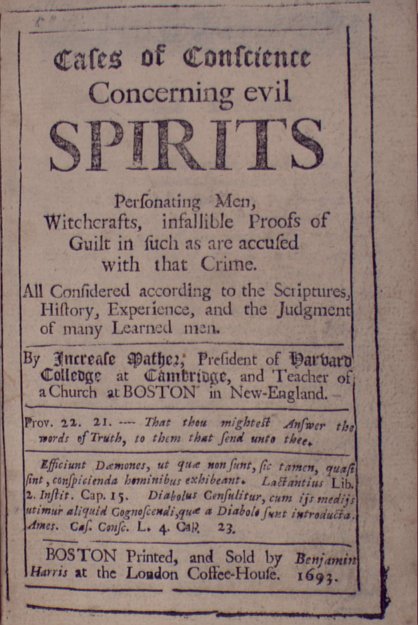

Governor Phips liked that account of things. He sent Wonders of the Invisible World to London as the official history of Salem and prohibited anyone else from publishing on the subject once the trials ended. But the very need to silence opposition proved how few agreed with Cotton Mather. Resistance started mounting immediately, propelled by the case of Rebecca Nurse; during her examination, more than three dozen citizens signed a petition proclaiming her innocence and defending her good character. Petitions continued to grow during the trials, with more and more brave persons signing documents attempting to save the lives of their neighbors. No petition worked. Yet the rising cry of protest did finally have an effect, bringing the noise of opposition and resistance to those who held the most power in the colony. Soon Increase Mather joined the protests, publishing his own account of Salem while the trials were underway. In Cases of Conscience , Increase specifically delegitimized the court’s use of spectral evidence, undercutting the primary source of convictions. That book, along with the protests of several leading Boston ministers, finally convinced Governor Phips to stop the trials.

The trips to Salem by Increase and Cotton Mather reveal their different mentalities. When Cotton Mather went to Salem, he witnessed a group execution that included the supposed “King of Hell,” George Burroughs. At the scaffold, Burroughs composed himself with so much calm and seeming godliness, including a perfect recitation of the Lord’s Prayer (thought impossible for a witch), that many in the crowd began to turn against the executions. Burroughs looked more like a Protestant saint from the pages of John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs than like a satanic wizard bent on the destruction of Christianity. 30 As the crowd started to protest, Cotton Mather mounted a horse and convinced the crowd that the devil often appeared as an angel of light, winning them back to the executions, which then continued.

Yet that line of thinking—that the devil might appear as an angel of light—could also damn the very trials it was meant to support. In fact, such an idea served Increase Mather’s argument rejecting spectral evidence. If the devil could appear in any shape, then perhaps the devil had taken the shape of someone innocent. Crying out against specters might be playing right into the devil’s hands. When Increase Mather traveled to Salem, therefore, he did not go to encourage the executions; instead, he visited the jails and spoke with the accused, including many who had confessed. There he learned about the extreme pressures applied to them and found that many had confessed because they believed it would save their lives. While talking with them, he witnessed the suffering of innocent persons in terrible, sickening jails, and he turned against the trials for good. When Increase returned home, he wrote the book that would help bring them to a close.

The mysteries of Salem are many, various, and difficult to solve. Why were these people afflicted? Why were those people accused? What explains the motivations and behavior of Samuel Parris, and how much was Parris’s temperament able to set the terms that enabled the tragedy to occur? Why did the judges reverse decades of precedent in an effort to convict and execute as many as they could? And how did the ministers respond? Who supported the trials, who opposed them, and why? These kinds of questions have produced contested answers, all attempting to balance the relative weight of importance behind each actor or cause. Salem is filled with questions. And while extensive records survive, those records seldom offer answers able to settle all disputes.

Reading and Remembering the Salem Witch Trials

The abiding mystery of Salem seems one reason for its enduring legacy. Governor Phips attempted to ban any discussion of Salem, but within three years that ban was violated, and no future silencing could take place. Thomas Maule, a Quaker, was the first to challenge the official proscription, with Truth Held Forth and Maintained in 1695 . The book had a long chapter criticizing the government for its handling of Salem. It was burned and Maule was arrested, spending several months in prison before facing many of the same judges and prosecutors he had attacked. Yet Maule stood by what he wrote. First, he defended its claims; then, slyly, he argued that his authorship could not be proven: anyone could have put his name on the title page. The grand jury found him not guilty, and the ban was broken. From that moment forward, critiques and reassessments of Salem have poured from the presses. 31

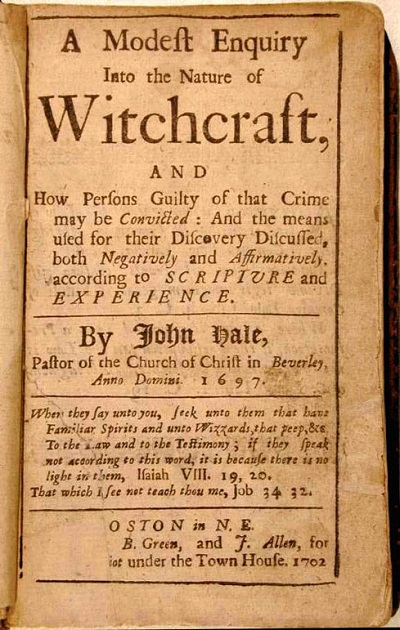

Yet many of these skeptical voices were not so clear about what exactly had happened: mistakes were made, to be sure, but the precise nature of those errors could not be determined. The minister John Hale, for example, who was first an advocate and later a skeptic at Salem, explained, “Such was the darkness of the day, the tortures and lamentations of the afflicted, and the power of former presidents [i.e., precedents], that we walked in the clouds, and could not see our way.” 32 Apologies eventually appeared from many involved, including the jury foreman, the afflicted girl Ann Putnam Jr., and the judge Samuel Sewall, who desired “to take the blame and shame of it.” 33 Yet most of these apologies came in Hale’s variety; they were, for the most part, apologies of the confused. Something had gone wrong, but who was to blame? In 1706 , Ann Putnam Jr., now twenty-nine, desired “to lie in the dust, and earnestly beg forgiveness from God and from all those unto whom I have given just cause of sorrow and offence.” But she did not say she faked her afflictions. Instead, she explained, “[I]t was a great delusion of Satan that deceived me in that sad time.” 34

The darkness of Salem often seems the aspect most remembered today. In popular histories, the Puritans usually appear as stock figures of backward superstition—hateful, unenlightened religious bigots who saw witches in every shadow and enjoyed nothing so much as a good hanging. 35 As Gretchen Adams has shown, such accounts of Salem emerged most prominently in the nation’s first schoolbooks, when American historians praised their country for its moral progress. 36 Yet many have demonstrated that such an assessment fails to fit the evidence: after all, many of those involved at Salem welcomed the new sciences emerging in Europe. Some were among the most intelligent and advanced figures of their day. Cotton Mather, for example, would become the first New Englander inducted into the British Royal Society, and his work promoting smallpox inoculation in later years would save far more lives than Salem lost. As Sarah Rivett has carefully demonstrated, the way in which Puritans approached evidence and testimony during the Salem witch trials—even and especially spectral evidence—was inflected through their embrace of empiricism. “Rather than a symbol of a fading occult worldview,” Rivett writes, “the devil in Salem represented a phase of an emerging Enlightenment modernity.” Against popular histories that caricature the Puritans as premodern, irrational religious fanatics, Rivett writes simply and convincingly: “Irrationality does not suffice as an adequate explanation of Salem.” 37

Still, something seemed to change at Salem—or rather, Salem seemed to demonstrate that something drastic had already shifted. The Salem witch trials have been presented in various ways as the end of Puritan New England. Perhaps Salem helped usher in a new age of religious skepticism, though belief in witchcraft persisted. More important, the relationship of state to church seemed to change. As Ray writes, “[N]ever again would the state ask the church for advice.” 38 But Salem seemed to happen in part because the magistrates disregarded the ministers’ advice, while at the same time still feeling compelled to ask for it. The ministers, too, seemed to recognize their weakening authority in their ambiguous responses and their inability (at least in most cases) to confront the magistrates openly. 39 This deepening divide between magistrates and ministers suggests not only that the Salem witch crisis caused the breakdown of Puritan New England, but that it also resulted in part from the ministers’ loss of authority.

Histories of the Salem witch trials begin with the records of the trials, and those documents raise their own sorts of questions. Secondhand accounts from several witnesses survive, along with confessions, petitions, and many of the preparatory documents for trial (such as depositions, indictments, and examinations), but the records of the actual trials before the Court of Oyer and Terminer have gone missing. In addition, the record book of the Salem Village Church does not contain the crucial years. Beyond a catalogue of what exists or not, we also have to take into consideration who did the recording, an aspect of the records made newly available by the extraordinary 2009 edition Records of the Salem Witch-Hunt . We know now, for example, that Thomas Putnam Jr., recorded (or “authored”) a great many depositions and testimonials—more than 120, amounting to more than one-third of the total number. Thomas Putnam and his extended family (including his afflicted wife, daughter, and servant) would account for 160 accusations and the prosecution of fifty-eight people, one-third of the total number accused and arrested. Moreover, Putnam’s ability to write or record these documents proved the power of his pen: his depositions were unusually successful. 40

The question of who wrote what and how documents were stylized, as well as questions of language and genre, shape our understanding of the surviving records and accounts. For example, Thomas Putnam has been noted for his use of stock phrases. Ray points out that the phrase “most grievously” appears 172 times in his descriptions of the suffering of the afflicted, while the phrases “grievously tortured” and “grievously tormented” appear forty-five times. 41 Was the use of such phrases responsible for Putnam’s strong results, and what does that tell us about the power of narrative or the expectations of audience during the Salem witch trials? As scholars have also highlighted, Putnam particularly loved to involve the heart. The depositions he “recorded” would often have an afflicted person saying: “I verily believe in my heart that [so-and-so] is a witch.” 42 These details about Putnam’s writings open the door to larger examinations of language and its effects. What stock phrases worked, and what made them work? Who else was involved in writing records, and how did their styles differ? Literary analysis could yield fresh results about how to read the records of the Salem witch trials.

Those fresh readings would be bolstered by two related approaches: borderlands studies and performance studies. For many years now, literary scholars have asked how to read and understand the texts produced at the meeting of two cultures. In particular, a methodology inflected by the concept of the “borderlands” offers ways of reading against the grain, helping, for instance, to locate Native American actors and Native American voices in texts written almost exclusively by Europeans. In the case of the Salem records we have a similar situation: How do we understand the actions and the voices of the accused in records written almost exclusively by the prosecution? How do we read the Salem witch trial records against the grain? It has always been known that the prosecution wrote most of the records that survive, but only recently have we learned just how much they were composed by particular individuals, such as Thomas Putnam Jr. With that understanding, we can now ask in new ways how to read what he and others produced. Performance studies could also open Salem with its rich theoretical understanding of “performance” and identity. Many have likened the Salem court to a stage. In fact, the spectacle of Salem, which brought together the afflicted, the accused, and the public, not only went against advice and precedent—previously, judges were urged to separate all parties and keep the afflicted individuals apart—it also provided the evidence later used to convict the accused. The spectral torments witnessed and performed during examinations became the basis of conviction. Performance studies thus has much to teach us about how to read Salem.

Beyond the actual events at Salem and their surviving records, there is also the remembering and remaking of Salem that has occurred ever since. Each generation has written its own account of Salem, though that writing proliferated in the wake of expanding education requirements and the new schoolbooks written to meet demand beginning in the early 1800s. In attempts to give the new nation a history and a tradition, Salem was invoked as a moral lesson: it represented the dark parts of the colonial past that the new United States had left behind. Novels, plays, and poetry dwelt on the tragedy as well. The first literary treatment of the trials, according to Gretchen Adams, was the 1817 epic poem The Sorceress, or Salem Delivered by Jonathan Scott. But as Adams explains, “By midcentury many notable nineteenth-century literary figures, including New England natives John Neal, John William De Forest, John Greenleaf Whittier, and of course Nathaniel Hawthorne produced major novels using the witchcraft trials as significant plot elements.” 43

As Adams indicates, perhaps the most famous author to wrestle with Salem was Nathaniel Hawthorne, a descendant of Judge Hathorne who added the “w” to his name in order to distinguish himself from his ancestor. Salem lies at the heart of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The House of the Seven Gables as well as several short stories, especially “Alice Doane’s Appeal” and “Young Goodman Brown.” In the short stories, Hawthorne dwells on the problem of spectral evidence. According to Michael Colacurcio, the link between the two tales told at Salem Gallows Hill in “Alice Doane’s Appeal” is that “both concern the Puritan problem of ‘specter evidence,’” in each case pointing readers to perceive “the truth of specter evidence as guilty projection”: that is, “in both cases the charges of diabolical evil probably reveals more about the accuser than the accused,” and such tendencies continue beyond a superstitious past. 44 The same concern with spectral evidence frames “Young Goodman Brown,” but here the question has changed to take up an issue from the trials themselves: if the devil can take any shape, and if those shapes were being used to identify the accused, then could the devil be trusted? In other words, and more deeply, how could one gain adequate knowledge of the invisible world and the true constitution of one’s neighbors and fellow church members? As Colacurcio aptly summarizes, the problem identified in “Young Goodman Brown” is that “the difficulty of detecting a witch is distressingly similar to the radically Puritan problem of discovering a saint.” And if one cannot adequately or accurately do either, then the Puritan experiment itself will fail. In “Young Goodman Brown,” Hawthorne essentially claims that Salem revealed the fundamental flaw in Puritanism: the inability to discover the invisible through the visible, to judge the status of another’s soul through visible practice or deed. As Colacurcio puts it, “Ultimately, evidence fails.” 45

Meanwhile, some 19th-century literary treatments of Salem turned to the tragedy for a homegrown American sensationalism, lending Gothic features to American fiction. This was certainly the case with John Neal’s novel Rachel Dyer ( 1828 ) and, in more nuanced ways, it continued with Hawthorne’s The House of the Seven Gables . Lawrence Buell analyzes such works as what he calls “provincial Gothic,” meaning “the use of Gothic conventions to anatomize the pathology of regional culture.” 46 In his account of this Gothic trend and its appeal, Buell gives one of the best summaries of how and why Salem made its way into the literary imagination of the nation and the nation’s writers in the 19th century. He writes, “We owe the fact that the Salem delusion is the best-known episode of early New England history next to the voyage of the Mayflower largely to Hawthorne and fellow gothicizers of his era, to whom witchcraft appealed … for a mixture of reasons: as an opportunity for proxy war against religious conservatives, as that instance from the regional past that resonated most strongly with the supernaturalism of traditional Gothic, and as a proof that New England culture was not so humdrum as early national critics had feared.” 47 But the appeal of Salem was not limited to the provincial Gothic; it also provides the plot and setting of several works by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. As Chadwick Hansen showed long ago, Longfellow’s play Giles Cory of Salem Farms , written in the wake of the Civil War, was the first account to transform Tituba into a half-black slave. 48 After Longfellow, others metamorphosed Tituba fully into an African American and finally into an African who was kidnapped as a child, even though nothing in the existing records lends support to such a claim and most scholars reject it. Tituba is one of many characters who has received her own rewritings through the years, including in the more recent and well-received novel, I, Tituba, Black Witch of Salem ( 1986 ) by Maryse Condé, which won the French Grand Prix award for women’s literature and was translated into English in 1992 .

As Condé’s novel reveals, the cultural memory and literary imagination of Salem lives on. During the Cold War, for example, Arthur Miller famously turned to Salem for a model that would lay bare the persecutions of supposed communists and subversives led by the House Un-American Activities Committee and Senator Joseph McCarthy. Here again, the primary problem was one of evidence: What counts as a clear indication of either patriotism or subversion, a good soul or a soul bent against the common good? The evidence would prove “spectral” in its own way, and Miller found Salem to be a good site for showing why. As The Crucible continues being regularly performed, joined by ever fresher retellings and reimaginings, the cultural memory and function of Salem seems rich for even further exploration. While individual readings of particular literary usages abound (especially for Hawthorne), no specifically literary history of Salem exists—no study of its changing shape and operation in plays, poems, and fiction from 1817 to the present day. What does Salem do for us, and why do certain accounts of Salem predominate over others? Popular understandings of the event often emphasize the girls’ fortune-telling practices, Tituba’s “voodoo” spells, and ergot poisoning—all theories invented after the Civil War and all rejected by most scholars. Yet the tales live on. What do such stories do for the cultural memory of Salem that more accurate, scholarly accounts fail to accomplish? More generally, why do Americans keep remembering, reliving, and remaking Salem? What need does it meet?

However Salem is approached or remembered, it is clear that scholars and the general public will keep grappling with what happened there in 1692 . The Salem witch trials have formed one of the cornerstone cultural memories of American history, a turning point from Puritan New England to a province more aligned with British imperial interests. How much actually changed as a result of the trials is open to question, and scholars have offered a wide variety of answers. Some have even tried to link the trials to the eventual coming of the American Revolution, though such approaches seem rather shaky at best. Nonetheless, all agree that something changed, or that the tragedy came about because of deep shifts in the culture and control of Puritan New England. The significance of Salem lies in the meaning and perception of that change, along with all the possible explanations for why and how it occurred. Yet for all the answers proposed, the enduring legacy of the witch trials arises primarily from the persistent aura of mystery that surround them—this tragic event erupting against precedent and probability, supported and opposed by people at every level of society and in every station of life, spun out of control by eager magistrates and frightened girls, resulting in a massive injustice that New England would reckon with for many years, and that Americans would be haunted by ever since.

Select Primary Sources

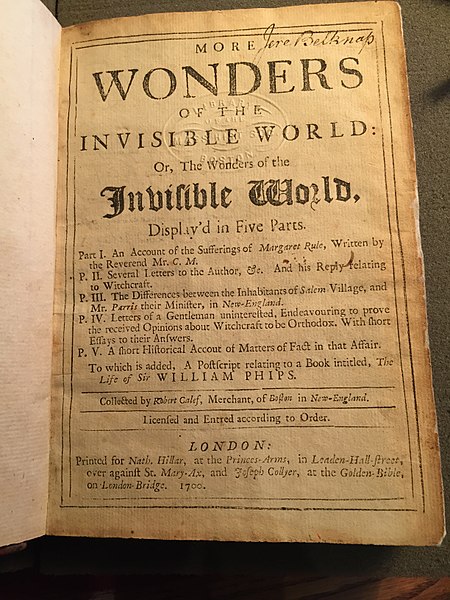

- Calef, Robert . More Wonders of the Invisible World . Salem, 1700. Reprint, Breinigsville, PA: Nabu Public Domain Reprints, 2011.

- Hall, David D. Witch-Hunting in Seventeenth-Century New England: A Documentary History, 1638–1693 . 2d ed. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1999.

- Mather, Cotton . Wonders of the Invisible World (London, 1693). Reprint, Lincoln, NB: Zea Books, 2011.

- Mather, Increase . Cases of Conscience Concerning Evil Spirits Personating Men (Boston, 1693) .

- Rosenthal, Bernard , ed. Records of the Salem Witch-Hunt . New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive and Transcription Project .

Select Literary Sources

- Condé, Maryse . I, Tituba, Black Witch of Salem . Translated by Richard Philcox . Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1992.

- de Forest, John William . Witching Times . New York: Putnam’s Magazine, 1856.

- Hawthorne, Nathaniel . The House of the Seven Gables . Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1851.

- Hawthorne, Nathaniel . “Alice Doane’s Appeal” (1835). Reprint in Complete Short Stories (Garden City, NY: Hanover House, 1959), and other collections.

- Hawthorne, Nathaniel . “Young Goodman Brown” (1846). Reprint in Complete Short Stories (Garden City, NY: Hanover House, 1959), and other collections.

- Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth . “Giles Corey of the Salem Farms.” In The New England Tragedies , by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow . Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1868.

- Miller, Arthur . The Crucible . New York: Viking, 1951.

Further Reading

- Adams, Gretchen . The Specter of Salem: Remembering the Witch Trials in Nineteenth-Century America . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

- Baker, Emerson . A Storm of Witchcraft: The Salem Trials and the American Experience . New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Boyer, Paul , and Stephen Nissenbaum . Salem Possessed: The Social Origins of Witchcraft . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1974.

- Breslaw, Elaine . Tituba, Reluctant Witch of Salem: Devilish Indians and Puritan Fantasies . New York: New York University Press, 1996.

- Demos, John . Entertaining Satan: Witchcraft and the Culture of Early New England . Updated ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Godbeer, Richard . The Devil’s Dominion: Magic and Religion in Early New England . New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- Karlsen, Carol . The Devil in the Shape of a Woman: Witchcraft in Colonial New England . New York: Norton, 1987.

- Norton, Mary Beth . In the Devil’s Snare: The Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692 . New York: Vintage, 2003.

- Ray, Benjamin . Satan and Salem: The Witch-Hunt Crisis of 1692 . Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2015.

- Reis, Elizabeth . Damned Women: Sinners and Witches in Puritan New England . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997.

1. Tituba is consistently described as an “Indian Woman, servant” in the records of the Salem witch hunt. In the lore and scholarship that arose about Salem, Tituba was transformed into a half-Indian and then into an African slave, sparking the crisis by practicing voodoo with the girls. There is no evidence for such a tale. For the most recent and persuasive scholar to argue for her African heritage, see Peter Charles Hoffer , The Devil’s Disciples: Makers of the Salem Witchcraft Trials (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), 2 . In the prologue, he claims that Tituba was kidnapped into slavery from “the southeast of present-day Nigeria—Yorubaland,” and this Yoruba background becomes important to his story of Salem. Elaine Breslaw, in contrast, identifies her as an Indian who lived in Barbados and probably came from South America. See Breslaw , Tituba, Reluctant Witch of Salem: Devilish Indians and Puritan Fantasies (New York: New York University Press, 1996) . Bernard Rosenthal has thoroughly debunked the myth that Tituba practiced magic rites with the girls and frightened them into their afflictions. See Bernard Rosenthal , Salem Story (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1993) , chap. 2, and Bernard Rosenthal , “Tituba’s Story,” New England Quarterly 71.2 (1998): 190–203 . Regardless of her identity or motives, the court certainly saw her as a valuable witness, interrogating her five separate times.

2. Carol Karlsen , The Devil in the Shape of a Woman: Witchcraft in Colonial New England (New York: Norton, 1987), xii . See also Elizabeth Reis , Damned Women: Sinners and Witches in Puritan New England (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997) .

3. On Puritan communal rituals, including a discussion of witchcraft cases, see David Hall , Worlds of Wonder, Days of Judgement: Popular Religious Belief in Early New England (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989) .

4. Benjamin Ray , “‘The Salem Witch Mania’: Recent Scholarship and American History Textbooks,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 78.1 (2010): 48–49 .

5. Hathorne probably beat Tituba into confessing, and he certainly directed her confession with his questions. As Ray explains, “The record of her testimony clearly demonstrates that Tituba’s confession was a collaborative confession.” Benjamin Ray , Satan and Salem: The Witch-Hunt Crisis of 1692 (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2015), 35 . At the same time, the expansion of witches beyond Good and Osborne seems Tituba’s own invention. Others see Tituba exercising more autonomy. As Breslaw writes, “Tituba the storyteller prolonged her life in 1692 through an imaginative ability to weave and embellish plausible tales.” Breslaw, Tituba, Reluctant Witch of Salem , xx.

6. Martha Cory also distrusted the afflicted girls and urged the judges to suspect them—a fact which might have led to an accusation against her in the early days. See Ray, Satan and Salem , 54: “The girls’ accusation of Cory would be their first retaliatory strike against an individual who cast doubt upon their legitimacy.”

7. As scholars have shown more recently, the witch hunt should not be thought of as a single episode, but rather as a series of phases. By mid-July, the Salem Village phase had passed, and no new accusations surfaced in that town; instead the witch hunt moved to Andover, which had far more accusations and confessions than Salem Village. Phases also included individual witch hunts in several Essex towns. See Ray, “‘The Salem Witch Mania,’” 44–45; and Ray, Satan and Salem , chap. 7.

8. For perhaps the best short narrative of what happened in Salem, see Emerson Baker , A Storm of Witchcraft: The Salem Trials and the American Experience (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015) , chap. 1. For a day-by-day account of what happened, see Marilynne K. Roach , The Salem Witch Trials: A Day-by-Day Chronicle of a Community under Siege (New York: Cooper Square, 2002) .

9. John Demos , Entertaining Satan: Witchcraft and the Culture of Early New England (updated ed.; New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), viii . Demos goes on to say that scholarship has long confirmed the first of these themes, but that the second “seems as yet underappreciated, but remains (to my way of thinking) an absolutely fundamental piece—in effect, the energy-source for each and every episode of witch-hunting.”

10. The arguments of Boyer and Nissenbaum have been strongly challenged. In a special issue of William and Mary Quarterly devoted to a reassessment of Salem Possessed , Benjamin Ray contests the geography of their map, and Richard Latner challenges the economic divisions of the afflicted and the accused. See Ray , “The Geography of Witchcraft Accusations in 1692 Salem Village,” William and Mary Quarterly 65.3 (2008): 449–478 ; Latner , “Salem Witchcraft, Factionalism, and Social Change Reconsidered: Were Salem’s Witch-Hunters Modernization’s Failures?” William and Mary Quarterly 65.3 (2008): 423–448 . Baker, Storm of Witchcraft , 119, offers some tentative support for Boyer and Nissenbaum, observing that “[w]itchcraft in both Europe and America was tied to the economic uncertainties of the early modern period.”

11. As Ray shows, these first two views—of economic and political instability—are older, standard narratives of Salem that still dominate American history textbooks. See Ray, “The Salem Witch Mania,” 40–64.

12. The leading source for this explanation remains Mary Beth Norton , In the Devil’s Snare: The Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692 (New York: Vintage, 2003) .

13. For critiques of each of these overall explanations, see Ray, Satan and Salem , 3–5; Ray, “‘The Salem Witch Mania,’” 40–64.

14. Richard Godbeer , The Devil’s Dominion: Magic and Religion in Early New England (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 186 .

15. Ray, Satan and Salem , 6.

16. For the strongest support of the fraud hypothesis, see Rosenthal, Salem Story .

17. Baker, Storm of Witchcraft , 99–100.

18. Ray, Satan and Salem , 65, explains: “If the girls’ initial fear of the devil was genuine, as seems likely, the court, in requiring them to reenact their trauma in the presence of every new defendant, was retraumatizing them on an almost weekly basis in the courtroom.” Ray also highlights the fact that the girls had no exit. As early as the case of Rebecca Nurse, Judge Hathorne claimed that if the girls were dissembling, they were as good as murderers. Ray, Satan and Salem , 64: “Even if they began to entertain doubts, there was no turning back, a lesson Mary Warren had learned at her peril.”

19. Baker, Storm of Witchcraft , 164.

20. Godbeer, Devil’s Dominion , 158.

21. For an account of the laws at work in the Salem witch trials, see Richard Trask , “Legal Procedures Used during the Salem Witch Trials and a Brief History of the Published Version of the Records,” in Records of the Salem Witch-Hunt , edited by Bernard Rosenthal (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 44–63 . See also David Konig , Law and Society in Puritan Massachusetts: Essex County, 1629–1692 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1979) .

22. In fact, as Godbeer points out, witch accusations were dropping off through the 1670s and 1680s, probably because people had learned how hard it was to convict a witch. Instead, they turned to countermagic for protection where the courts had failed. Moreover, he points out that the lack of witch cases in previous decades perhaps created a backlog of complaints, all of which came tumbling out at Salem; much of the evidence presented against the accused concerned actions and incidents from years before. See Godbeer, Devil’s Dominion , 177–182. For an excellent account of the magisterial and ministerial restraint toward witchcraft prosecution in the previous six decades and how that changed at Salem, see John Murrin , “Coming to Terms with the Salem Witch Trials,” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 110.2 (2003): 309–348 .

23. Only one person, Nehemiah Abbot, would be found innocent after initial questioning, but all twenty-eight tried before the Court of Oyer and Terminer were found guilty; Baker, Storm of Witchcraft , 186.

24. Bernard Rosenthal , “General Introduction,” in Records of the Salem Witch-Hunt , edited by Bernard Rosenthal (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 34 .

25. For the strongest proponent of this thesis, see Norton, In the Devil’s Snare .

26. See Baker, Storm of Witchcraft , 161–170.

27. “On the stories flowed,” writes David Hall, “stories mainly rooted in the suffering of bewildered people who watched children or their spouses die or suffer agonizing fits”; David Hall, Worlds of Wonder , 191.

28. See James F. Cooper and Kenneth P. Minkema , eds., The Sermon Notebook of Samuel Parris, 1689–1694 (Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 1993) , especially the editors’ introduction.

29. For more on Parris as central to the outbreak, see Ray, Satan and Salem , chap. 1.

30. For the influence of John Foxe and his modeling of martyrdom, see David Hall, Worlds of Wonder , 186–195. See also Adrian Weimer , Martyrs’ Mirror: Persecution and Holiness in Early New England (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011) .

31. For a great, brief account of Thomas Maule, see Baker, Storm of Witchcraft , 213–219. Baker argues that the attempted government cover-up is responsible, in part, for its prominent place in American cultural memory.

32. Quoted in Norton, In the Devil’s Snare , 312. Norton, chap. 8, has an excellent account of the massive and sudden turning of opinion against Salem witch trial convictions.

33. Quoted in Baker, Storm of Witchcraft , 223.

34. Quoted in Baker, Storm of Witchcraft , 235.

35. For the most recent popular history, see Stacy Schiff , The Witches: Salem, 1692 (New York: Little, Brown, 2015) . Popular history is important, but it often thrives on caricature. For a trenchant criticism of Schiff’s book, see Jane Kamensky , “‘ The Witches: Salem, 1692,’ by Stacy Schiff ,” Sunday Book Review, The New York Times (October 27, 2015) .

36. Gretchen A. Adams , The Specter of Salem: Remembering the Witch Trials in Nineteenth-Century America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008) .

37. Sarah Rivett , Science of the Soul in Colonial New England (Chapel Hill: Omohundro Institute for University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 226 .

38. Ray, “‘The Salem Witch Mania,’” 60.

39. Ray, “‘The Salem Witch Mania,’” 49: “Indeed, the magistrates may have refused to listen to the Boston clergy because all of them had recently been appointed to the Governor’s Council by the Crown and did not owe any allegiance to the clergy.” According to Murrin, “Coming to Terms,” 340: “Most historians have concluded that by late June the judges had decided to ignore the advice of the ministers altogether and were willing to convict on the basis of spectral evidence alone.”

40. For the number of depositions, testimonials, and accusations made by Thomas Putnam and his family, see Ray, Satan and Salem , 94–95. For more on the recording of the depositions, trials and other documents of Salem, see Peter Grund , “From Tongue to Text: The Transmission of the Salem Witchcraft Records,” American Speech 82 (2007): 119–150 .

41. Ray, Satan and Salem , 100.

42. Ray, Satan and Salem , 96. Much at Salem turned on the heart. Since the afflicted seemed so genuinely tormented, all were expected to sympathize with them in their distress. When an accused witch laughed, derided the court, or simply failed to weep for the torments of the tortured girls, that visible lack of fellow feeling could be used as a sign of guilt. Such evidence appears through a close tracking of language about “sympathy,” “dry eyes,” and the “heart.” See Abram Van Engen , Sympathetic Puritans: Calvinist Fellow Feeling in Early New England (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 199–210 .

43. Adams, Specter of Salem , 61. See her chap. 2 for the broader case about schoolbooks.

44. Michael Colacurcio , The Province of Piety: Moral History in Hawthorne’s Early Tales (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1995) . For his full reading of the short story, see 78–93.

45. Colacurcio, Province of Piety , 286, 300.

46. Lawrence Buell , New England Literary Culture: From Revolution Through Renaissance (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 351 .

47. Buell, New England Literary Culture , 360.

48. Chadwick Hansen , “The Metamorphosis of Tituba, or Why American Intellectuals Can’t Tell an Indian Witch from a Negro,” New England Quarterly 47.1 (1974): 3–12 .

Related Articles

- Colonial Writing in North America

- Mather, Cotton

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Literature. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 02 June 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.194.105.172]

- 185.194.105.172

Character limit 500 /500

What Caused the Salem Witch Trials?

Looking into the underlying causes of the Salem Witch Trials in the 17th century.

In February 1692, the Massachusetts Bay Colony town of Salem Village found itself at the center of a notorious case of mass hysteria: eight young women accused their neighbors of witchcraft. Trials ensued and, when the episode concluded in May 1693, fourteen women, five men, and two dogs had been executed for their supposed supernatural crimes.

The Salem witch trials occupy a unique place in our collective history. The mystery around the hysteria and miscarriage of justice continue to inspire new critiques, most recently with the recent release of The Witches: Salem, 1692 by Pulitzer Prize-winning Stacy Schiff.

But what caused the mass hysteria, false accusations, and lapses in due process? Scholars have attempted to answer these questions with a variety of economic and physiological theories.

The economic theories of the Salem events tend to be two-fold: the first attributes the witchcraft trials to an economic downturn caused by a “little ice age” that lasted from 1550-1800; the second cites socioeconomic issues in Salem itself.

Emily Oster posits that the “little ice age” caused economic deterioration and food shortages that led to anti-witch fervor in communities in both the United States and Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Temperatures began to drop at the beginning of the fourteenth century, with the coldest periods occurring from 1680 to 1730. The economic hardships and slowdown of population growth could have caused widespread scapegoating which, during this period, manifested itself as persecution of so-called witches, due to the widely accepted belief that “witches existed, were capable of causing physical harm to others and could control natural forces.”

Salem Village, where the witchcraft accusations began, was an agrarian, poorer counterpart to the neighboring Salem Town, which was populated by wealthy merchants. According to the oft-cited book Salem Possessed by Paul Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum, Salem Village was being torn apart by two opposing groups–largely agrarian townsfolk to the west and more business-minded villagers to the east, closer to the Town. “What was going on was not simply a personal quarrel, an economic dispute, or even a struggle for power, but a mortal conflict involving the very nature of the community itself. The fundamental issue was not who was to control the Village, but what its essential character was to be.” In a retrospective look at their book for a 2008 William and Mary Quarterly Forum , Boyer and Nissenbaum explain that as tensions between the two groups unfolded, “they followed deeply etched factional fault lines that, in turn, were influenced by anxieties and by differing levels of engagement with and access to the political and commercial opportunities unfolding in Salem Town.” As a result of increasing hostility, western villagers accused eastern neighbors of witchcraft.

But some critics including Benjamin C. Ray have called Boyer and Nissenbaum’s socio-economic theory into question . For one thing –the map they were using has been called into question. He writes: “A review of the court records shows that the Boyer and Nissenbaum map is, in fact, highly interpretive and considerably incomplete.” Ray goes on:

Contrary to Boyer and Nissenbaum’s conclusions in Salem Possessed, geo graphic analysis of the accusations in the village shows there was no significant villagewide east-west division between accusers and accused in 1692. Nor was there an east-west divide between households of different economic status.

On the other hand, the physiological theories for the mass hysteria and witchcraft accusations include both fungus poisoning and undiagnosed encephalitis.

Linnda Caporael argues that the girls suffered from convulsive ergotism, a condition caused by ergot, a type of fungus, found in rye and other grains. It produces hallucinatory, LSD-like effects in the afflicted and can cause victims to suffer from vertigo, crawling sensations on the skin, extremity tingling, headaches, hallucinations, and seizure-like muscle contractions. Rye was the most prevalent grain grown in the Massachusetts area at the time, and the damp climate and long storage period could have led to an ergot infestation of the grains.