Ideas for Great Group Work

Many students, particularly if they are new to college, don’t like group assignments and projects. They might say they “work better by themselves” and be wary of irresponsible members of their group dragging down their grade. Or they may feel group projects take too much time and slow down the progression of the class. This blog post by a student— 5 Reasons I Hate Group Projects —might sound familiar to many faculty assigning in-class group work and longer-term projects in their courses.

We all recognize that learning how to work effectively in groups is an essential skill that will be used by students in practically every career in the private sector or academia. But, with the hesitancy of students towards group work and how it might impact their grade, how do we make group in-class work, assignments, or long-term projects beneficial and even exciting to students?

The methods and ideas in this post have been compiled from Duke faculty who we have consulted with as part of our work in Learning Innovation or have participated in one of our programs. Also included are ideas from colleagues at other universities with whom we have talked at conferences and other venues about group work practices in their own classrooms.

Have clear goals and purpose

Students want to know why they are being assigned certain kinds of work – how it fits into the larger goals of the class and the overall assessment of their performance in the course. Make sure you explain your goals for assigning in-class group work or projects in the course. You may wish to share:

- Information on the importance of developing skills in group work and how this benefits the students in the topics presented in the course.

- Examples of how this type of group work will be used in the discipline outside of the classroom.

- How the assignment or project benefits from multiple perspectives or dividing the work among more than one person.

Some faculty give students the option to come to a consensus on the specifics of how group work will count in the course, within certain parameters. This can help students feel they have some control over their own learning process and and can put less emphasis on grades and more on the importance of learning the skills of working in groups.

Choose the right assignment

Some in-class activities, short assignments or projects are not suitable for working in groups. To ensure student success, choose the right class activity or assignment for groups.

- Would the workload of the project or activity require more than one person to finish it properly?

- Is this something where multiple perspectives create a greater whole?

- Does this draw on knowledge and skills that are spread out among the students?

- Will the group process used in the activity or project give students a tangible benefit to learning in and engagement with the course?

Help students learn the skills of working in groups

Students in your course may have never been asked to work in groups before. If they have worked in groups in previous courses, they may have had bad experiences that color their reaction to group work in your course. They may have never had the resources and support to make group assignments and projects a compelling experience.

One of the most important things you can do as an instructor is to consider all of the skills that go into working in groups and to design your activities and assignments with an eye towards developing those skills.

In a group assignment, students may be asked to break down a project into steps, plan strategy, organize their time, and coordinate efforts in the context of a group of people they may have never met before.

Consider these ideas to help your students learn group work skills in your course.

- Give a short survey to your class about their previous work in groups to gauge areas where they might need help: ask about what they liked best and least about group work, dynamics of groups they have worked in, time management, communication skills or other areas important in the assignment you are designing.

- Allow time in class for students in groups to get to know each other. This can be a simple as brief introductions, an in-class active learning activity or the drafting of a team charter.

- Based on the activity you are designing and the skills that would be involved in working as a group, assemble some links to web resources that students can draw on for more information, such as sites that explain how to delegate and share responsibilities, conflict resolution, or planning a project and time management. You can also address these issues in class with the students.

- Have a plan for clarifying questions or possible problems that may emerge with an assignment or project. Are there ways you can ask questions or get draft material to spot areas where students are having difficulty understanding the assignment or having difficulty with group dynamics that might impact the work later?

Designing the assignment or project

The actual design of the class activity or project can help the students transition into group work processes and gain confidence with the skills involved in group dynamics. When designing your assignment, consider these ideas.

- Break the assignment down into steps or stages to help students become familiar with the process of planning the project as a group.

- Suggest roles for participants in each group to encourage building expertise and expertise and to illustrate ways to divide responsibility for the work.

- Use interim drafts for longer projects to help students manage their time and goals and spot early problems with group projects.

- Limit their resources (such as giving them material to work with or certain subsets of information) to encourage more close cooperation.

- Encourage diversity in groups to spread experience and skill levels and to get students to work with colleagues in the course who they may not know.

Promote individual responsibility

Students always worry about how the performance of other students in a group project might impact their grade. A way to allay those fears is to build individual responsibility into both the course grade and the logistics of group work.

- Build “slack days” into the course. Allow a prearranged number of days when individuals can step away from group work to focus on other classes or campus events. Individual students claim “slack days” in advance, informing both the members of their group and the instructor. Encourage students to work out how the group members will deal with conflicting dates if more than one student in a group wants to claim the same dates.

- Combine a group grade with an individual grade for independent write-ups, journal entries, and reflections.

- Have students assess their fellow group members. Teammates is an online application that can automate this process.

- If you are having students assume roles in group class activities and projects, have them change roles in different parts of the class or project so that one student isn’t “stuck” doing one task for the group.

Gather feedback

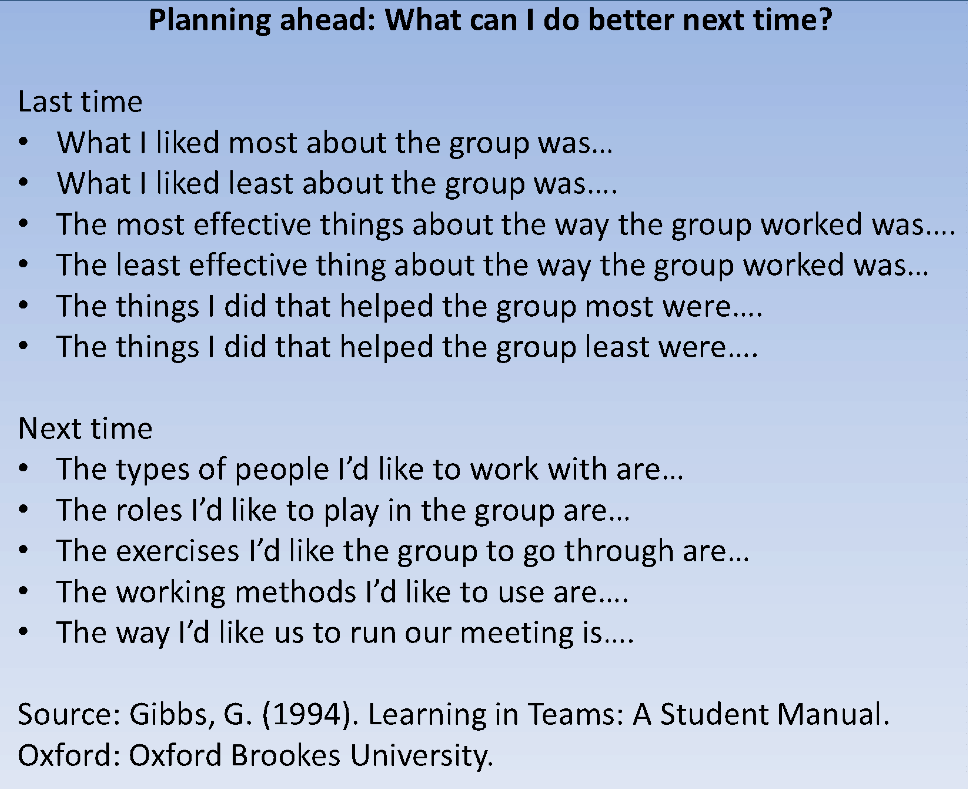

To improve your group class activities and assignments, gather reflective feedback from students on what is and isn’t working. You can also share good feedback with future classes to help them understand the value of the activities they’re working on in groups.

- For in-class activities, have students jot down thoughts at the end of class on a notecard for you to review.

- At the end of a larger project, or at key points when you have them submit drafts, ask the students for an “assignment wrapper”—a short reflection on the assignment or short answers to a series of questions.

Further resources

Information for faculty

Best practices for designing group projects (Eberly Center, Carnegie Mellon)

Building Teamwork Process Skills in Students (Shannon Ciston, UC Berkeley)

Working with Student Teams (Bart Pursel, Penn State)

Barkley, E.F., Cross, K.P., and Major, C.H. (2005). Collaborative learning techniques: A handbook for college faculty. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Johnson, D.W., Johnson, R., & Smith, K. (1998). Active learning: Cooperation in the college classroom. Edina, MN: Interaction Book Company.

Thompson, L.L. (2004). Making the team: A guide for managers. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education Inc.

Information for students

10 tips for working effectively in groups (Vancouver Island University Learning Matters)

Teamwork skills: being an effective group member (University of Waterloo Centre for Teaching Excellence)

5 ways to survive a group project in college (HBCU Lifestyle)

Group project tips for online courses (Drexel Online)

Group Writing (Writing Center at UNC-Chapel Hill)

7 Tips to More Effectively Work on Group Projects

Want to work more effectively on group projects in your college classes? Check out these tips to help you and your group streamline the process.

- News and Events

Tags in Article

- Tips & Best Practices

- Graduate Degree Programs

- Saint Leo Learning

- Undergraduate Studies

When you're in college, it is up to you to complete the work necessary to earn your degree. That said, assigning group projects is a common practice in higher education. Not to mention, many job roles require that you work as a team. So, the sooner you learn to master this type of interaction, the better. These seven tips can help, making your group project a success.

1. Start off the group project on the right foot.

Before you even begin the group project, meet as a group and introduce yourselves. Maybe even do a quick ice breaker, such as asking each member what they ate for breakfast or the best book they ever read. Taking a moment to get to know each other starts the group on the right foot. It helps each of you develop a greater level of comfortability, which is going to be important as you strive to work cohesively in the days and weeks ahead. If you are all in the same vicinity, perhaps you can hold this meeting in person. If you are scattered about, hold this meeting virtually so everyone can attend. Online platforms such as Microsoft Teams or Zoom can be used for this purpose.

2. Designate a group leader.

Although it is important to hold each member of the group on the same level, designating someone as a leader gives each of you someone to go to if problems arise. Assigning someone to oversee the entire project also creates one more point of checks and balances. Ask for volunteers. If more than one person wants this role, have a group vote. If no one raises their hand, consider stepping up. This is a great opportunity to build your leadership skills, which can serve you well once you enter your career.

3. Set clear expectations for all group members.

One reason some groups fail to meet their objective is that the members aren't really clear about what they are responsible for completing. Avoid this by deciding upfront who will do what. Be extremely clear so every member knows what they must do to contribute to the final project. The clearer you are when setting these expectations, the fewer misunderstandings you will have as the group project progresses.

4. Be honest about your abilities.

Ideally, each group member should be assigned a task that matches his or her strengths. This leads to a higher quality finished product, a project that allows each member to shine. If you are competitive by nature, it may be tempting to want to be responsible for a task that is above your abilities. Stretching yourself is great, but not when it is at the expense of your team. With that in mind, don't promise something you can't deliver. Be honest about your strengths so the team can decide how you can best meet its needs.

5. Set deadlines and stick to them.

Napoleon Hill once said that " a goal is a dream with a deadline ." Setting mini-deadlines throughout the project keeps the team on task. It enables you to achieve your ultimate goal, which is to turn in the best project possible. Each project is different so, as a team, create a timeline that is realistic and allows you to submit your project on time. Decide what needs to be done at each step. The more specific you are, the better.

6. Meet regularly to check in.

Regular check-ins create accountability. It encourages members to complete their portion of the project on time because they know that they'll have to face the rest of the group on a pre-set day and time. Meeting often also gives the team the opportunity to step in if something goes off course. Maybe a member had an emergency that prevented them from doing their part. Other members can quickly step in and pick up the slack. As with the initial meeting, these check-ins can be done in person or online. Be sure to choose a time when everyone is available. This may require some flexibility as you work around different schedules.

7. Be respectful to all members…always.

Above all, always be respectful to each group member. Keep in mind that people have varying communication styles and some are naturally better at working as a team. Knocking them for their weaknesses doesn't further the group as a whole, nor does it speak well for you on a personal level. One strategy for always acting respectfully is to imagine that the other person is a family member that you respect—such as a sibling, parent, or grandparent—and treat them accordingly. Remember that the way you interact with them shapes the way you are viewed. Would you rather be known as someone who is patient and considerate or someone who easily loses their temper and puts their needs above those of the group?

The Bottom Line on Group Projects

Working in a group isn't always easy. However, following these seven tips can make your team project a greater success, and it will better prepare you for team projects once you complete your degree and enter your field.

Saint Leo University See more from this author

The 3Rs - by Alex Quigley

3 Rs is my fortnightly newsletter where I’ll share interesting w®iting, reading, and interesting research from the world of education and beyond.

Success! Now Check Your Email

To complete Subscribe, click the confirmation link in your inbox. If it doesn’t arrive within 3 minutes, check your spam folder.

Top 10 Group Work Strategies

If I am continually vexed by any one question in education it is ‘how can we enhance student motivation?‘ Of course, I do not have the answer, and if there is one it is multi-faceted, complex and, frankly, not going to be solved in this blog post. From my position

If I am continually vexed by any one question in education it is ‘ how can we enhance student motivation? ‘ Of course, I do not have the answer, and if there is one it is multi-faceted, complex and, frankly, not going to be solved in this blog post.

From my position as a classroom teacher, I am always on the look out for those strategies that create a state when students are motivated and in their element , where they work furiously without even realising they are doing so, without realising the clock is ticking down to the end of the lesson. There is no better compliment than when students question how long there is left and express genuine surprise at how fast time has passed, and that they have actually enjoyed that lesson.

My, admittedly non-scientific, observations are that many of the times students are in ‘ flow ‘, or their element, in my lessons is when they are collaborating in group work.

Why is this then? I believe that we are obviously social beings and we naturally learn in such groups (not always effectively it must be said), but that, more importantly, when working in a group we are able to correct, support, encourage, question and develop ideas much more effectively. The power of the group, guided by the expertise of the teacher, accelerates learning, makes it richer and demands a learning consensus that can push people beyond their habitual assumptions.

Don’t get me wrong, there are pitfalls and obstacles to group work. This constructivist approach should build upon expert teacher led pedagogy – ensuring that students have a good grounding in the relevant knowledge before undertaking in-depth group work. Group work can also be beset by issues in many nuanced forms: whether it is subtle intellectual bullying, where the student who shouts loudest prevails; or the encouragement of mediocrity and laziness, as students let others do all the work; or simply by poor, distracting behaviour.

Another issue is ‘group think’ miscomprehension – indeed, how does prejudice flourish if not in social groups? Yet, this failure is often great for learning as long as the teacher can illuminate the error of their ways. Of course, no teaching strategy is foolproof and plain good teaching should remedy many of the potential ills of group work, just as good teaching can make more traditional teacher-led ‘direct instruction’ wholly engaging and effective.

I am intrigued by the idea of ‘ social scaffolding ‘ (Vygotsky) – the concept that most of our learning is undertaken in group situations, where we learn through dialogue and debate with others, not simply by listening to that voice in our head! That being said, I am not talking teachers out of a classroom here.

The role of the teacher in devising and planning a successful group task takes skill, rigour and utter clarity and precision. Students need to be clear about a whole host of things: from their role, to the purpose of the task and the parameters of expected outcomes to name but a few. Teachers need to keep groups on track, intervene appropriately to improve learning and regularly regain student focus. Teachers have a pivotal role in guiding the group work at every stage.

Group work certainly isn’t the lazy option: it takes skill in the planning and the execution, and sometimes, despite our best laid plans, it still fails. That shouldn’t put us off – aren’t all teaching and learning strategies subject to such risks?

If I was to define a simple and straight-forward basis for the rules for group work it would be:

– Have clearly defined tasks, with sharp timings and with the appropriate tools organised – Have clearly defined group roles – Have clear ground rules for talk, listening and fair allocation of workload etc. – Target your support and interventions throughout the task, but make them interdependent of one another, not dependent upon you – Always be prepared to curtail group work if students don’t follow your high expectations.

So here it is, my entirely subjective top 10 strategies for group work that I believe to be effective (ideas for which I must thank a multitude of sources):

1. ‘Think-pair-share’ and ‘Think-pair-square’.

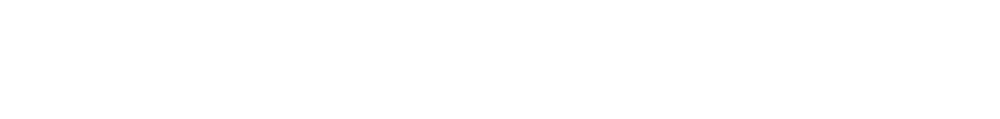

Well, no-one said this top ten had to be original! This strategy is one of those techniques that we employ so readily that we can almost forget about it, it is simply so automatic for most teachers; yet, because of that we can easily forget it in our planning. We need to use it regularly because it is the very best of scaffolded learning; it almost always facilitates better quality feedback by allowing proper thinking time and for students to sound out their ideas and receive instantaneous feedback from peers. ‘Think-pair-square’ adds a touch of added flavour, involving linking two pairs together (to form the ‘square’ to share their ideas before whole class feedback). I defer to this blog post by @headguruteacher for the skinny on ‘Think-pair-share’ here .

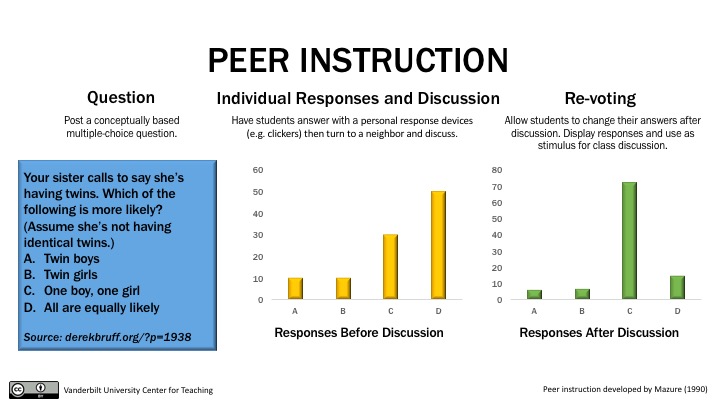

2. Snowballing or the Jigsaw method

Similar to the ‘square’ approach mentioned in ‘Think-Pair-Square’, the ‘snowballing’ activity is another simple but very effective way of building upon ideas by starting with small groups and expanding the groups in a structured way. As the metaphor of the snowball suggests, you can begin with an individual response to a question; followed by then pairing up students up; then creating a four and so on. It does allow for quick, flexible group work that doesn’t necessarily require much planning, but does keep shaping viewpoints and challenging ‘answers’ is a constructive fashion.

The ‘jigsaw method’ is slightly more intricate. David Didau describes here how it is the “ultimate teaching method”, but that it benefits greatly from careful planning. Put simply, when researching a topic, like the causes of the Second World War, each member of a group is allocated an area for which they need to become the ‘ expert ‘, such as ‘the impact of the Treaty of Versailles’, or ‘issues with the dissolution of Austria-Hungary’ for example. With five or six ‘ Home ‘ groups identified, the ‘ experts ‘ then leave that group to come together to pool their expertise on the one topic; they question one another and combine research, ideas and their knowledge. Then each ‘ expert ‘ returns to their ‘ home ‘ group to share their findings. It is a skilful way of varying group dynamics as well as scaffolding learning.

3. Debating (using clear rules)

As you probably know, our own inspiring leader, Michael Gove, was the President of the Oxford Union. Clearly, these ancient skills of rhetoric and debate have seen him rise to dizzying heights. Perhaps we need to teach debating with great skill if we are to produce citizens who can debate with the best of them…and with Michael Gove. The premise of a debate, and its value in enriching the learning of logic, developing understanding and the simultaneous sharpening and opening our minds, is quite obvious so I will not elaborate. If you are ever stuck for a debate topic then this website will be of great use: http://idebate.org/debatabase . The Oxford rules model is an essential model for the classroom in my view. It provides a clear structure and even a level of formality which is important, provide coherence and greater clarity to the debate. The rules, familiar steps though they are for many, are as follows:

Four speakers in each team (for and against the motion) First speaker introduces all the ideas that team has generated Second speaker outlines two or three more ideas in some depth Third speaker outlines two or three ideas in some depth Fourth speaker criticises the points made by the other team Each individual speaker has two minutes to speak (or more of course), with protected time of thirty seconds at the beginning or the end The rest of the team is the ‘ Floor ‘ and can interject at any time by calling out ‘ Point of Information ‘ and standing. The speaker can accept or reject an interjection.

You may wish to have the other groups work as feedback observers on the debate being undertaking (a little like Socratic circles – number 8 ). This has the benefit of keeping the whole class engaged and actively listening to the debate.

4. Project Based Learning/Problem Based Learning

I have to admit I have only ever undertaken project style work on a small scale, but in the last year I have been startled by the quality of work I have observed in project based learning across the world. The principals of Project Based Learning are key: such as identifying real audiences and purposes for student work (a key factor in enhancing motivation); promoting interdependent student work, often subtly guided by the teacher at most stages; letting students undertake roles and manage the attendant challenges that arise; learning is most often integrated and spans subject areas; and students constructing their own questions and knowledge. Truly the best guide is to survey these great examples:

The Innovation Unit has also produced this brilliant must-read guide to PBL in great depth here .

‘Problem based learning’ is clearly related to the project model, but it explicitly starts with a problem to be solved. It is based primarily upon the model from medicine – think Dr House (although he is hardly a team player!). David Didau sagely recommends that the teacher, or students in collaboration, find a specifically local problem – this raises the stakes of the task. Clearly, in Mathematics, real problem based learning can be a central way to approach mathematical challenges in a collaborative way; in Science or Philosophy, the options to tackle ethical and scientific problems are endless. There is criticism of this approach – that students struggle with the ‘ cognitive load’ without more of a working memory. Ideally, this learning approach follows some high quality direct instruction, and teacher led worked examples, to ensure that students have effective models to work from and some of the aforementioned working memory.

5. Group Presentations

I would ideally label this strategy: ‘ questions, questions, questions ‘ as it is all about creating, and modelling, a culture of enquiry by asking students questions about a given topic, rather than didactically telling them the answer – then helping shape their research. The teacher leads with a ‘ big question ‘; then it is taken on by groups who (given materials, such as books, magazines, essays, iPads, laptops, or access to the library or an ICT suite etc.) have to interrogate the question, forming their own sub-set of questions about the question/ topic. They then source and research the key information, before finally agreeing to the answers to the questions they had themselves formed. The crucial aspect about presentations is giving students enough time to make the presentation worthwhile, as well as allocating clear roles. High quality presentations take time to plan, research and execute.

Personally, I find the timekeeper role a waste of time (I can do that for free!), but other roles, such as leader, designer and scribe etc. have value. Also, the teaching needs to be carefully planned so the entire presentation is not reliant solely upon any one person or piece of technology. Developing a shared understanding of the outcome and the different parameters of the presentation is key: including features like banning text on PowerPoints; or making it an expectation that there is some element of audience participation; to agreeing what subject specific language should be included. The devil is in the detail!

6. ‘Devise the Display’

I have a troubled relationship with displays! I very rarely devise my own display as I think displays become wallpaper far too soon considering the effort taken to provide them – like newspapers, they become unused within days. I much prefer a ‘ working wall ‘, that can be constantly changed or updated (or a ‘learning continuum’ for an entire topic when can be periodically added to each lesson). That being said, I do think there is real high quality learning potential in the process of students devising and creating wall displays. It is great formative feedback to devise a wall display once you are well under way a topic. It makes the students identify and prioritise the key elements of their knowledge and the skills they are honing.

I find the most valuable learning is actually during the design ideas stage.You can ‘snowball’ design ideas with the students; beginning individually, before getting groups to decide collaboratively on their design; then having a whole class vote. I do include stipulations for what they must include, such as always including worked examples. Then, the sometimes chaotic, but enjoyable activity it to create the display. I always aim for the ‘ 60 Minute Makeover ‘ approach – quick and less painful (it also makes you less precious about the finer details)!

I think they also learn a whole host of valuable skills involving team work, empathy and not to annoy me by breaking our wall staplers! I think it is then important to not let any display fester and waste, but to pull it down and start afresh with a new topic. I know this strategy does put some people off, because it can be like organised chaos, but if everyone has a clear role and responsibility the results can be amazing. [Warning – some designs can look like they have been produced by Keith Richards on a spectacular acid trip!]

7. Gallery Critique

This stems from the outstanding work of on Berger. Both a teacher and a craftsman himself, Berger explains the value of critique as rich feedback in his brilliant book ‘ The Ethic of Excellence ‘. It can be used during the draft/main process or as a summative task. This strategy does have some specific protocols students should follow. The work of the whole group should be displayed in a gallery style for a short time. Students are expected to first undertake a short silent viewing (making notes to reflect is also useful here). The students make comments on the work – post it notes being ideal for this stage. Then the next step is a group discussion of ‘ what they noticed ‘ in particular, with debate and discussion encouraged – of course, the feedback should be both kind and constructive. The next step for discussion is talking about ‘ what they liked ‘, evaluating the work. The final stage has the teacher synthesise viewpoints and express their own; before ensuring students make notes and reflect upon useful observations for making improvements.

8. Socratic Talk

I have spoken about this strategy before here . What is key is that like the debating rules above, a clear and defined structure is in place, particularly with ‘ Socratic circles ‘ which embeds feedback and debate in a seamless way. It takes some skill in teaching students how to talk in this fashion, but once taught, it can become a crucial tool in the repertoire. In my experience, some of the most sensitive insights have emerged from this strategy and the listening skills encouraged are paramount and have an ongoing positive impact. It also allows for every student to have a role and quality feedback becomes an expectation.

9. Talking Triads

Another simple, but highly effective strategy. It is a strategy that gets people to explore a chosen topic, but with a really rigorous analysis of ideas and views. The triad comprises of a speaker , a questioner and a recorder/analyst . You can prepare questions, or you can get the questioner and the analyst to prepare questions whilst the speaker prepares or reflects upon potential answers. This can be done in front of the class as a gallery of sorts, or you can have all triads working simultaneously. If they do work simultaneously, then a nice addition is to raise your hand next to a particular triad, which signals for other groups to stop and listen whilst that specific triad continues, allowing for some quality listening opportunities.

10. Mastery Modelling

This involves a form of formative assessment from students, whereat the teacher gives a group a series of models, both exemplar models and lesser models, including some with common errors that students would likely identify. The students need to do a critical appraisal of the these models as a group and identify their summary assessment of the models first, before then devising and presenting a ‘mastery model’ that is a composite exemplar model of work. This strategy works in pretty much every subject, with the subject being either an essay, a piece of art, or a mathematical problem. This presentation should include an explicit focus upon the steps taken leading to create the ‘ mastery model ‘ during the feedback – this unveils the process required for mastery for the whole class.

Useful links:

A great research paper that analyses group work and its importance: ‘Toward a social pedagogy of classroom group work’ By Peter Blatchford, Peter Kutnick, Ed Baines, and Maurice Galton

An excellent National Strategies booklet from back in the day when the DfE was interested in pedagogy. I particularly like the ‘ different grouping criteria’/’size of grouping’ tables: Pedagogy and Practice: Teaching and Learning in Secondary Schools Unit 10: Group work

Nice step by step guide to the implementation and the delivery of group work ‘ Implementing Group Work in the Classroom ‘

The 3Rs - Reading, writing, and research to be interested in #40

Adaptive Teaching: Scaffolds, Scale, Structure and Style

Adaptive teaching may be tricky to define, but we must define it well, and exemplify it, otherwise it will prove an empty buzzword. I’ve tried to characterise it into broadly two types of adaptations: * Microadaptations (Corno, 2008). Sensitive, moment-to-moment adaptations responding to pupils’ learning e.g. deploying flexible grouping

The 3Rs - Reading, writing, and research to be interested in #39

Alex Quigley (The Confident Teacher) is a blog by the author, Alex Quigley - @AlexJQuigley - sharing ideas and evidence about education, teaching and learning.

Copyright © 2024 Alex Quigley. Published with Ghost and Alex Quigley .

- Effective Teaching Strategies

10 Recommendations for Improving Group Work

- September 12, 2014

- Maryellen Weimer, PhD

Many faculty now have students do some graded work in groups. The task may be, for example, preparation of a paper or report, collection and analysis of data, a presentation supported with visuals, or creation of a website. Faculty make these assignments with high expectations. They want the groups to produce quality work—better than what the students could do individually—and they want the students to learn how to work productively with others. Sometimes those expectations are realized, but most of the time there is room for improvement—sometimes lots of it. To that end, below is a set of suggestions for improving group projects. A list in the article referenced below provided a starting place for these recommendations.

- Emphasize the importance of teamwork—

- Teach teamwork skills—Most students don’t come to group work knowing how to function effectively in groups. Whether in handouts, online resources, or discussions in class, teachers need to talk about the responsibilities members have to the group (such as how sometimes individual goals and priorities must be relinquished in favor of group goals) and about what members have the right to expect from their groups. Students need strategies for dealing with members who are not doing their fair share. They need ideas about constructively resolving disagreement. They need advice on time management.

- Use team-building exercises to build cohesive groups—Members need the chance to get to know each other, and they should be encouraged to talk about how they’d like to work together. Sometimes a discussion of worst group experiences makes clear to everyone that there are behaviors to avoid. This might be followed with a discussion of what individual members need from the group in order to do their best work. Things like picking a group name and creating a logo also help create a sense of identity for the group, which in turn fosters the commitment groups need from their members in order to succeed.

- Thoughtfully consider group formation—Most students prefer forming their own groups, and in some studies these groups are more productive. In other research, students in these groups “enjoy” the experience of working together, but they don’t always get a lot done. In most professional contexts, people don’t get to choose their project partners. If the goal is for students to learn how to work with others whom they don’t know, then the teacher should form the groups. There are many ways groups can be formed and many criteria that can be used to assemble groups. Groups should be formed in a way that furthers the learning goals of the group activity.

- Make the workload reasonable and the goals clear—Yes, the task can be larger than what one individual can complete. But students without a lot of group work experience may struggle with large, complex tasks. Whatever the task, the teacher’s goals and objectives should be clear. Students shouldn’t have to spend a lot of time trying to figure out what they are supposed to be doing.

- Consider roles for group members—Not all the literature recommends assigning roles, although some does. Roles can emerge on their own as members see what functions the group needs and step up to fill those roles. However, this doesn’t always happen when students are new to group work. The teacher can decide on the necessary roles and suggest them to a group with the group deciding who does what. The teacher can assign the roles, but should realize that assigning roles doesn’t guarantee that students will assume those roles. Assigned roles can stay the same or they can rotate. However they’re implemented, roles are taken more seriously if groups are required to report who filled what role in the group.

- Provide some class time for meetings—It is very hard for students to orchestrate their schedules. Part of what they need to be taught about group work is the importance of coming to meetings with an agenda—some expectation about what needs to get done. They also need to know that significant amounts of work can be done in short periods of time, provided the group knows what needs to be done next. Working online is also increasingly an option, but being able to convene even briefly in class gives groups the chance to touch base and get organized for the next steps.

- Request interim reports and group process feedback—One of the group’s first tasks ought to be the creation of a time line—what they expect to have done by when. That time line should guide instructor requests for progress reports from the group, and the reports should be supported with evidence. It’s not good enough for the group to say it’s collecting references. A list of references collected should be submitted with the report. Students should report individually on how well the group is working together, including their contributions to the group. Ask students what else could they contribute that would make the group function even more effectively.

- Require individual members to keep track of their contributions—The final project should include a report from every member identifying their contribution to the project. If two members report contributing the same thing, the teacher defers to the student who has evidence that supports what the student claims to have done.

- Include peer assessment in the evaluation process—What a student claims to have contributed to the group and its final product can also be verified with a peer assessment in which members rate or rank (or both) the contributions of others. A formative peer assessment early in the process can help members redress what the group might identify as problems they are experiencing at this stage.

Students, like the rest of us, aren’t born knowing how to work well in a group. Fortunately, it’s a skill that can be taught and learned. Teacher design and management of group work on projects can do much to ensure that the lessons students learn about working with others are the ones that will serve them well the next time they work in groups.

Reference: Hansen, R.S. (2006). Benefits and problems with student teams: Suggestions for improving team projects. Journal of Education for Business, September/October, 11-19.

Reprinted from Improving Group Projects. The Teaching Professor, 27.6 (2013): 4-5. © Magna Publications. All rights reserved.

This Post Has 7 Comments

Maryellen, I don't know how you continue to "hit it out of the park" — everything you share is right on! Thanks for your dedication to helping us teach better!

Thanks. Very helpful!

Pingback: How to Effectively Improve Student Group Work

Pingback: 10 Recommendations for Improving Group Work - KidScholastic

Pingback: Spotlight on Presentations | interlochenblog

Pingback: Problems In America: Group Projects | haleyfossitt

Pingback: Another Year Over… | foundations for learning

Comments are closed.

Stay Updated with Faculty Focus!

Get exclusive access to programs, reports, podcast episodes, articles, and more!

- Opens in a new tab

Welcome Back

Username or Email

Remember Me

Already a subscriber? log in here.

- Jump to menu

- Student Home

- Accept your offer

- How to enrol

- Student ID card

- Set up your IT

- Orientation Week

- Fees & payment

- Academic calendar

- Special consideration

- Transcripts

- The Nucleus: Student Hub

- Referencing

- Essay writing

- Learning abroad & exchange

- Professional development & UNSW Advantage

- Employability

- Financial assistance

- International students

- Equitable learning

- Postgraduate research

- Health Service

- Events & activities

- Emergencies

- Volunteering

- Clubs and societies

- Accommodation

- Health services

- Sport and gym

- Arc student organisation

- Security on campus

- Maps of campus

- Careers portal

- Change password

Guide to Group Work

This page will inform you about the nature of group work, about what you should expect and the expectations teachers have of you in group learning situations.

Learning and working effectively as part of a team or group is an extremely important skill, and one that you will refine and use throughout your working life. Group projects should be among the most valuable and rewarding learning experiences. For many students, however, they are also among the most frustrating.

Here are some pointers to help you work effectively on your group tasks and assignments. These are mostly general principles that you should apply to group work here, in other courses and in the workplace.

Why we use group learning tasks

Learning in groups means that you need to share your knowledge and ideas with other students. There are two principal ways that you benefit from doing this:

- you need to think carefully about your own ideas in order to explain them to others

- you expand your own awareness by taking account of the knowledge and ideas of others.

When you work as a group on a project or assignment, then you have the opportunity to draw on the different strengths of group members, to produce a more extensive and higher quality project or assignment than you could complete on your own.

To do this effectively you need to learn group work skills, which are an extremely important part of your professional development. In most professions people are required to work in multidisciplinary project teams or teams with a responsibility for a specific task. Many professional organisations and employer groups stress the importance of interpersonal and group skills, such as communication, negotiation, problem solving, and teamwork. These skills can be as important as your subject knowledge in enabling you to be an effective professional.

This kind of group work is actually an ongoing process of generating ideas and planning as a group, working as an individual to carry out parts of that plan and then communicating as a group to draw the individual components together and plan the next step.

Skills in group work

Group work requires both interpersonal and process management skills. Group work is included in a course to provide a safe environment in which you can try out new ideas and practices and learn some group skills. Some of the skills you need to develop are outlined here, you will discover some others for yourself.

Interpersonal skills

- Building positive working relationships

- Communicating effectively in meetings

- Negotiating to agree on tasks and resolve conflicts

- Accommodating people with different cultural orientations and work habits

Process management skills

- Identifying group goals and dividing work

- Planning and complying with meeting schedules and deadlines

- Managing time to meet group expectations

- Monitoring group processes and intervening to correct problems

Interpersonal skills and considerations

- Take some time early on to chat with and get to know each of your group mates. The better you know one another and the more comfortable you are communicating with one another, the more effectively you will be able to work together. The online discussion set up for your group can be used to exchange information about backgrounds and interests as an icebreaker that elicits information that may not normally be available. The online discussion often helps people who are shy or reluctant to speak in a conversational way.

- feel comfortable voicing their opinions, and feel that these opinions will be listened to.

- feel that all group members are contributing positively to the tasks by keeping to agreed procedures and plans and producing good quality work, on time.

- feel that their feelings are being considered by team members, yet the goals and objectives of the group are not being compromised to accommodate the whim or the wants of a few members.

Make sure that you both express your views and listen to others. There is nothing wrong with disagreeing with your group mates, no matter how confident they may seem to be about what they are saying. When you disagree, be constructive and focus on the issue rather than the person. Likewise when someone disagrees with you, respect what they are saying and the risk that they took in expressing their opinion. Try to find a way forward that everybody can agree to and that isn't the opinion of just one confident or outspoken member.

Managing the process

Effective group work does not happen by accident. It involves deliberate effort, and because there are many people involved it must not be left up to memory; good note taking is essential. Following these steps will help you and your group to work effectively together.

- Have clear objectives . At each stage you should try to agree on goals. These include a timetable for progress on the project as well as more immediate goals (e.g. to agree on an approach to the assignment by Friday). Each meeting or discussion should also begin with a goal in mind (e.g. to come up with a list of tasks that need to be done).

- Set ground rules . Discussions can become disorderly and can discourage shyer group members from participating if you don't have procedures in place for encouraging discussion, coming to resolution without becoming repetitive, and resolving differences of opinion. Set rules at the outset and modify them as necessary along the way. An interesting rule that one group made was that anybody who missed a meeting would buy the rest of the group a cup of coffee from the coffee shop. Nobody ever missed a meeting after that.

- Communicate efficiently . Make sure you communicate regularly with group members. Try to be clear and positive in what you say without going on or being repetitive.

- Build consensus . People work together most effectively when they are working toward a goal that they have agreed to. Ensure that everyone has a say, even if you have to take time to get more withdrawn members to say something. Make sure you listen to everyone's ideas and then try to come to an agreement that everyone shares and has contributed to.

- Define roles . Split the work to be done into different tasks that make use of individual strengths. Having roles both in the execution of your tasks and in meetings / discussions (e.g. Arani is responsible for summarising discussions, Joseph for ensuring everybody has a say and accepts resolutions etc.) can help to make a happy, effective team. See Sharing and organising work for more information.

- Clarify . When a decision is made, this must be clarified in such a way that everyone is absolutely clear on what has been agreed, including deadlines.

- Keep good records . Communicating on the online discussion for your group provides a good record of discussion. Try to summarise face-to-face discussions and especially decisions, and post them to the online discussion so that you can refer back to them. This includes lists of who has agreed to do what.

- Stick to the plan . If you agreed to do something as part of the plan, then do it. Your group are relying on you to do what you said you would do not what you felt like doing. If you think the plan should be revised, then discuss this.

- Monitor progress and stick to deadlines . As a group, discuss progress in relation to your timetable and deadlines. Make sure that you personally meet deadlines to avoid letting your group down.

Set up a contract

A useful tool to help with the steps above is a contract. Within the first week of each group task you and your group will need to negotiate and agree to a contract. In this signed agreement, you will outline what you are going to do, who is going to do what, and by when. As a guide to negotiating your group contracts a contract proforma is reproduced at the end of this document.

Sharing and organising work online

Two kinds of work must be shared: to make the team function and the task to be performed.

Making the team function

An effective team requires the following roles to work efficiently. It is useful to explicitly allocate these functions.

- Facilitator or leader (depending on context) for making sure the aims of the meeting are clarified and for summarising discussions and decisions; to ensure the meeting keeps on track and ground rules are followed.

- Note taker to keep a record of ideas that are discussed and decisions that are made and who is doing what.

- Time keeper to make sure that you discuss everything you need to in the time available for the meeting.

- Progress chaser to chase people up and make sure that the jobs get done by the time agreed and sort out problems if they are not.

- Process watcher someone who has an eye on process rather than content and can bring problems to the attention of the team. It is important to be positive in this role and not judgemental.

- Editor to compile contributions, identify gaps or overlaps, and ensure consistency in the final submission.

Sharing the task

Tasks need to be broken down into smaller parts and scheduled. Sometimes one part cannot be started until another part is finished so it may be worth drawing a simple time line.

- Consider the resources that you have and those that you will need to find.

- Define the outcome required.

- Consider how will you know when you have done it well enough?

- Divide the tasks among the team and

- Set the deadlines for the sub-tasks and times for future meetings.

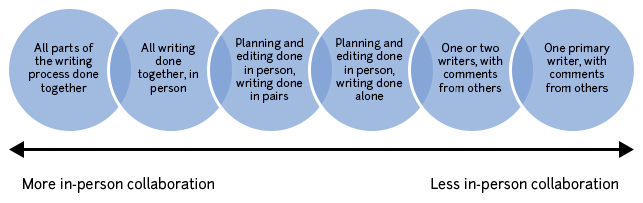

Team writing

Three methods are possible (and acceptable).

- One person writes the lot -this tends to mean a narrow range of idea are used and the rest of the team don’t learn from the activity of preparing the report.

- Each person writes one bit - it is then hard to make a single coherent report and you don’t learn about much except your own section.

- Joint writing. This is the most productive way of approaching group tasks, and ensures the greatest benefits from collaboration. Eg: Each section has a writer and at least one reviewer with each team member being both a writer and a reviewer of some section. The final product should be reviewed by all team members prior to finalisation by the editor. Alternatively you can have a single writer with others editing, adding and proof reading and someone tidying up the finished report.

Check the following:

- Is the objective of the exercise clear from the report?

- Are the conclusions or recommendations clear?

- Do conclusions follow from the body of the report?

- Do the sections fit together well?

- Does the report achieve the objectives (and the assessment criteria)?

- Are the required components adequately covered?

Whichever method you use, all group members should agree on the process, and how they are going to maximise the collaborative approach to writing.

Collaborative writing

Writing collaboratively is one of the trickiest parts of group work. There are many ways to do this, and your group will have to resolve how to divide the work of writing, collating, editing and putting the final touches on your work. Writing by committee (six people crowded around a keyboard) is a recipe for conflict and lack of progress. The other extreme, where one person takes the most responsibility and ends up doing most of the work, is also unproductive and promotes resentment.

Try to divide the initial writing into tasks, and tackle these individually or in pairs. Once the first drafts of the components have been written, circulate all the components and read them. You will probably need to get together to discuss how to marry them together so that they are consistent with one another. Any members who were not involved in the initial writing can do some of this work. Then edit, improve and polish the manuscript.

Circulate the files as online discussion attachments, or set up a Google doc or Wiki for everyone to add to. If using attachments, ensure that everybody knows who has and is working on the current version; otherwise it becomes

Monitoring group effectives and overcoming problems

The checklist at the end of this document provides a list of common issues that emerge in group work. Use it regularly to identify problems before they get out of hand. If major problems and tensions do arise, use it to identify where things may be going wrong. First answer each question about yourself, then answer it about the group as a whole. Then get together as a group and discuss where each of you think there may be problems and consider how you might overcome these problems.

Group tasks and assignments may mean that marks are assigned to everybody in the group based on the result for the whole group. It is in everybody's interest to ensure an effective contribution from all group members, to make sure that the finished assignment is of high quality. Sometimes a system of peer assessment will be used to determine the relative contributions of everyone to the group process. This could be used to moderate the marks for the assignment, or simply as a way to provide feedback on your group work skills.

Teamwork checklist

Each member should complete this checklist. You will need time to reflect in order to make this a worthwhile exercise. You should complete this exercise reasonably regularly in order to monitor and improve how effectively your group is working.

- Answer each question regarding your own performance in the group.

- Answer each question regarding the rest of the group.

- Get together with your whole group and discuss where you think any problems are arising.

Discuss what you are going to do to overcome these problems.

Adapted from Scoufis (2000).

Teamwork contract

Here's an example of how you might format a group contract.

We, the members of .....(group name)..... agree to the following plan of action regarding our work toward the group assignment tasks:

(The following is a list of items you may wish to include in your contract).

Meetings and communication

- Times and places for in person meetings.

- Frequency of checks to WebCT discussion area.

- Rules and procedures during face-to-face meetings.

- Who will summarise decisions, when will he/she post them on the discussion area.

Work and deadlines

- How will the group come to agreement on a topic (what research are members expected to do before you meet / go online to discuss the topic)?

- When will you make a final decision on a topic?

- Who will write the first draft of and who will first edit each component? Deadlines.

- Who will collate the whole submission and then circulate it for the group to comment on? Deadline.

- Who will prepare and submit the final submission? Deadline.

- What happens if members don’t meet agreed-to deadlines?

- What happens if members do not contribute / come to meetings?

The agreement should be finalised within the first week. It must be signed and dated by the group members. Each member should get a copy, a copy should be posted on the discussion area and the original should be submitted to your tutor.

Acknowledgement

This document (version: BA300112) was developed by staff at the Learning and Teaching Unit at UNSW, and includes material adapted from handouts developed by faculty teaching staff at UNSW.

- Gibbs, G. (1994). Learning in Teams: A student Manual. Oxford: The Oxford Centre for Staff Development.

- Scoufis, M. (2000). Integrating Graduate Attributes into the Undergraduate Curricula. University of Western Sydney. (ISBN 1863418725).

Lectures, tutorials, group work

- Discussion skills

- ^ More support

Hexamester 3: Library 101 Webinar 8 May 2024

Scholarly Resources 4 Students | scite.ai 21 May 2024

- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code

fa51e2b1dc8cca8f7467da564e77b5ea

- Make a Gift

- Join Our Email List

Many students have had little experience working in groups in an academic setting. While there are many excellent books and articles describing group processes, this guide is intended to be short and simply written for students who are working in groups, but who may not be very interested in too much detail. It also provides teachers (and students) with tips on assigning group projects, ways to organize groups, and what to do when the process goes awry.

Some reasons to ask students to work in groups

Asking students to work in small groups allows students to learn interactively. Small groups are good for:

- generating a broad array of possible alternative points of view or solutions to a problem

- giving students a chance to work on a project that is too large or complex for an individual

- allowing students with different backgrounds to bring their special knowledge, experience, or skills to a project, and to explain their orientation to others

- giving students a chance to teach each other

- giving students a structured experience so they can practice skills applicable to professional situations

Some benefits of working in groups (even for short periods of time in class)

- Students who have difficulty talking in class may speak in a small group.

- More students, overall, have a chance to participate in class.

- Talking in groups can help overcome the anonymity and passivity of a large class or a class meeting in a poorly designed room.

- Students who expect to participate actively prepare better for class.

Caveat: If you ask students to work in groups, be clear about your purpose, and communicate it to them. Students who fear that group work is a potential waste of valuable time may benefit from considering the reasons and benefits above.

Large projects over a period of time

Faculty asking students to work in groups over a long period of time can do a few things to make it easy for the students to work:

- The biggest student complaint about group work is that it takes a lot of time and planning. Let students know about the project at the beginning of the term, so they can plan their time.

- At the outset, provide group guidelines and your expectations.

- Monitor the groups periodically to make sure they are functioning effectively.

- If the project is to be completed outside of class, it can be difficult to find common times to meet and to find a room. Some faculty members provide in-class time for groups to meet. Others help students find rooms to meet in.

Forming the group

- Forming the group. Should students form their own groups or should they be assigned? Most people prefer to choose whom they work with. However, many students say they welcome both kinds of group experiences, appreciating the value of hearing the perspective of another discipline, or another background.

- Size. Appropriate group size depends on the nature of the project. If the group is small and one person drops out, can the remaining people do the work? If the group is large, will more time be spent on organizing themselves and trying to make decisions than on productive work?

- Resources for students. Provide a complete class list, with current email addresses. (Students like having this anyway so they can work together even if group projects are not assigned.)

- Students that don't fit. You might anticipate your response to the one or two exceptions of a person who really has difficulty in the group. After trying various remedies, is there an out—can this person join another group? work on an independent project?

Organizing the work

Unless part of the goal is to give people experience in the process of goal-setting, assigning tasks, and so forth, the group will be able to work more efficiently if they are provided with some of the following:

- Clear goals. Why are they working together? What are they expected to accomplish?

- Ways to break down the task into smaller units

- Ways to allocate responsibility for different aspects of the work

- Ways to allocate organizational responsibility

- A sample time line with suggested check points for stages of work to be completed

Caveat: Setting up effective small group assignments can take a lot of faculty time and organization.

Getting Started

- Groups work best if people know each others' names and a bit of their background and experience, especially those parts that are related to the task at hand. Take time to introduce yourselves.

- Be sure to include everyone when considering ideas about how to proceed as a group. Some may never have participated in a small group in an academic setting. Others may have ideas about what works well. Allow time for people to express their inexperience and hesitations as well as their experience with group projects.

- Most groups select a leader early on, especially if the work is a long-term project. Other options for leadership in long-term projects include taking turns for different works or different phases of the work.

- Everyone needs to discuss and clarify the goals of the group's work. Go around the group and hear everyone's ideas (before discussing them) or encourage divergent thinking by brainstorming. If you miss this step, trouble may develop part way through the project. Even though time is scarce and you may have a big project ahead of you, groups may take some time to settle in to work. If you anticipate this, you may not be too impatient with the time it takes to get started.

Organizing the Work

- Break up big jobs into smaller pieces. Allocate responsibility for different parts of the group project to different individuals or teams. Do not forget to account for assembling pieces into final form.

- Develop a timeline, including who will do what, in what format, by when. Include time at the end for assembling pieces into final form. (This may take longer than you anticipate.) At the end of each meeting, individuals should review what work they expect to complete by the following session.

Understanding and Managing Group Processes

- Groups work best if everyone has a chance to make strong contributions to the discussion at meetings and to the work of the group project.

- At the beginning of each meeting, decide what you expect to have accomplished by the end of the meeting.

- Someone (probably not the leader) should write all ideas, as they are suggested, on the board, a collaborative document, or on large sheets of paper. Designate a recorder of the group's decisions. Allocate responsibility for group process (especially if you do not have a fixed leader) such as a time manager for meetings and someone who periodically says that it is time to see how things are going (see below).

- What leadership structure does the group want? One designated leader? rotating leaders? separately assigned roles?

- Are any more ground rules needed, such as starting meetings on time, kinds of interruptions allowed, and so forth?

- Is everyone contributing to discussions? Can discussions be managed differently so all can participate? Are people listening to each other and allowing for different kinds of contributions?

- Are all members accomplishing the work expected of them? Is there anything group members can do to help those experiencing difficulty?

- Are there disagreements or difficulties within the group that need to be addressed? (Is someone dominating? Is someone left out?)

- Is outside help needed to solve any problems?

- Is everyone enjoying the work?

Including Everyone and Their Ideas

Groups work best if everyone is included and everyone has a chance to contribute ideas. The group's task may seem overwhelming to some people, and they may have no idea how to go about accomplishing it. To others, the direction the project should take may seem obvious. The job of the group is to break down the work into chunks, and to allow everyone to contribute. The direction that seems obvious to some may turn out not to be so obvious after all. In any event, it will surely be improved as a result of some creative modification.

Encouraging Ideas

The goal is to produce as many ideas as possible in a short time without evaluating them. All ideas are carefully listened to but not commented on and are usually written on the board or large sheets of paper so everyone can see them, and so they don't get forgotten or lost. Take turns by going around the group—hear from everyone, one by one.

One specific method is to generate ideas through brainstorming. People mention ideas in any order (without others' commenting, disagreeing or asking too many questions). The advantage of brainstorming is that ideas do not become closely associated with the individuals who suggested them. This process encourages creative thinking, if it is not rushed and if all ideas are written down (and therefore, for the time-being, accepted). A disadvantage: when ideas are suggested quickly, it is more difficult for shy participants or for those who are not speaking their native language. One approach is to begin by brainstorming and then go around the group in a more structured way asking each person to add to the list.

Examples of what to say:

- Why don't we take a minute or two for each of us to present our views?

- Let's get all our ideas out before evaluating them. We'll clarify them before we organize or evaluate them.

- We'll discuss all these ideas after we hear what everyone thinks.

- You don't have to agree with her, but let her finish.

- Let's spend a few more minutes to see if there are any possibilities we haven't thought of, no matter how unlikely they seem.

Group Leadership

- The leader is responsible for seeing that the work is organized so that it will get done. The leader is also responsible for understanding and managing group interactions so that the atmosphere is positive.

- The leader must encourage everyone's contributions with an eye to accomplishing the work. To do this, the leader must observe how the group's process is working. (Is the group moving too quickly, leaving some people behind? Is it time to shift the focus to another aspect of the task?)

- The leader must encourage group interactions and maintain a positive atmosphere. To do this the leader must observe the way people are participating as well as be aware of feelings communicated non-verbally. (Are individuals' contributions listened to and appreciated by others? Are people arguing with other people, rather than disagreeing with their ideas? Are some people withdrawn or annoyed?)

- The leader must anticipate what information, materials or other resources the group needs as it works.

- The leader is responsible for beginning and ending on time. The leader must also organize practical support, such as the room, chalk, markers, food, breaks.

(Note: In addition to all this, the leader must take part in thc discussion and participate otherwise as a group member. At these times, the leader must be careful to step aside from the role of leader and signal participation as an equal, not a dominant voice.)

Concerns of Individuals That May Affect Their Participation

- How do I fit in? Will others listen to me? Am I the only one who doesn't know everyone else? How can I work with people with such different backgrounds and expericnce?

- Who will make the decisions? How much influence can I have?

- What do I have to offer to the group? Does everyone know more than I do? Does anyone know anything, or will I have to do most of the work myself?

Characteristics of a Group that is Performing Effectively

- All members have a chance to express themselves and to influence the group's decisions. All contributions are listened to carefully, and strong points acknowledged. Everyone realizes that the job could not be done without the cooperation and contribution of everyone else.

- Differences are dealt with directly with the person or people involved. The group identifies all disagreements, hears everyone's views and tries to come to an agreement that makes sense to everyone. Even when a group decision is not liked by someone, that person will follow through on it with the group.

- The group encourages everyone to take responsibility, and hard work is recognized. When things are not going well, everyone makes an effort to help each other. There is a shared sense of pride and accomplishment.

Focusing on a Direction

After a large number of ideas have been generated and listed (e.g. on the board), the group can categorize and examine them. Then the group should agree on a process for choosing from among the ideas. Advantages and disadvantages of different plans can be listed and then voted on. Some possibilities can be eliminated through a straw vote (each group member could have 2 or 3 votes). Or all group members could vote for their first, second, and third choices. Alternatively, criteria for a successful plan can be listed, and different alternatives can be voted on based on the criteria, one by one.

Categorizing and evaluating ideas

- We have about 20 ideas here. Can we sort them into a few general categories?

- When we evaluate each others' ideas, can we mention some positive aspects before expressing concerns?

- Could you give us an example of what you mean?

- Who has dealt with this kind of problem before?

- What are the pluses of that approach? The minuses?

- We have two basic choices. Let's brainstorm. First let's look at the advantages of the first choice, then the disadvantages.

- Let's try ranking these ideas in priority order. The group should try to come to an agreement that makes sense to everyone.

Making a decision

After everyone's views are heard and all points of agreement and disagreement are identified, the group should try to arrive at an agreement that makes sense to everyone.

- There seems to be some agreement here. Is there anyone who couldn't live with solution #2?

- Are there any objections to going that way?

- You still seem to have worries about this solution. Is there anything that could be added or taken away to make it more acceptable? We're doing fine. We've agreed on a great deal. Let's stay with this and see if we can work this last issue through.

- It looks as if there are still some major points of disagreement. Can we go back and define what those issues are and work on them rather than forcing a decision now.

How People Function in Groups

If a group is functioning well, work is getting done and constructive group processes are creating a positive atmosphere. In good groups the individuals may contribute differently at different times. They cooperate and human relationships are respected. This may happen automatically or individuals, at different times, can make it their job to maintain the atmospbere and human aspects of the group.

Roles That Contribute to the Work

Initiating —taking the initiative, at any time; for example, convening the group, suggesting procedures, changing direction, providing new energy and ideas. (How about if we.... What would happen if... ?)

Seeking information or opinions —requesting facts, preferences, suggestions and ideas. (Could you say a little more about... Would you say this is a more workable idea than that?)

Giving information or opinions —providing facts, data, information from research or experience. (ln my experience I have seen... May I tell you what I found out about...? )

Questioning —stepping back from what is happening and challenging the group or asking other specific questions about the task. (Are we assuming that... ? Would the consequence of this be... ?)

Clarifying —interpreting ideas or suggestions, clearing up confusions, defining terms or asking others to clarify. This role can relate different contributions from different people, and link up ideas that seem unconnected. (lt seems that you are saying... Doesn't this relate to what [name] was saying earlier?)

Summarizing —putting contributions into a pattern, while adding no new information. This role is important if a group gets stuck. Some groups officially appoint a summarizer for this potentially powerful and influential role. (If we take all these pieces and put them together... Here's what I think we have agreed upon so far... Here are our areas of disagreement...)

Roles That Contribute to the Atmosphere

Supporting —remembering others' remarks, being encouraging and responsive to others. Creating a warm, encouraging atmosphere, and making people feel they belong helps the group handle stresses and strains. People can gesture, smile, and make eye-contact without saying a word. Some silence can be supportive for people who are not native speakers of English by allowing them a chance to get into discussion. (I understand what you are getting at...As [name] was just saying...)

Observing —noticing the dynamics of the group and commenting. Asking if others agree or if they see things differently can be an effective way to identify problems as they arise. (We seem to be stuck... Maybe we are done for now, we are all worn out... As I see it, what happened just a minute ago.. Do you agree?)

Mediating —recognizing disagreements and figuring out what is behind the differences. When people focus on real differences, that may lead to striking a balance or devising ways to accommodate different values, views, and approaches. (I think the two of you are coming at this from completely different points of view... Wait a minute. This is how [name/ sees the problem. Can you see why she may see it differently?)

Reconciling —reconciling disagreements. Emphasizing shared views among members can reduce tension. (The goal of these two strategies is the same, only the means are different… Is there anything that these positions have in common?)

Compromising —yielding a position or modifying opinions. This can help move the group forward. (Everyone else seems to agree on this, so I'll go along with... I think if I give in on this, we could reach a decision.)

Making a personal comment —occasional personal comments, especially as they relate to the work. Statements about one's life are often discouraged in professional settings; this may be a mistake since personal comments can strengthen a group by making people feel human with a lot in common.

Humor —funny remarks or good-natured comments. Humor, if it is genuinely good-natured and not cutting, can be very effective in relieving tension or dealing with participants who dominate or put down others. Humor can be used constructively to make the work more acceptable by providing a welcome break from concentration. It may also bring people closer together, and make the work more fun.

All the positive roles turn the group into an energetic, productive enterprise. People who have not reflected on these roles may misunderstand the motives and actions of people working in a group. If someone other than the leader initiates ideas, some may view it as an attempt to take power from the leader. Asking questions may similarly be seen as defying authority or slowing down the work of the group. Personal anecdotes may be thought of as trivializing the discussion. Leaders who understand the importance of these many roles can allow and encourage them as positive contributions to group dynamics. Roles that contribute to the work give the group a sense of direction and achievement. Roles contributing to the human atmosphere give the group a sense of cooperation and goodwill.

Some Common Problems (and Some Solutions)

Floundering —While people are still figuring out the work and their role in the group, the group may experience false starts and circular discussions, and decisions may be postponed.

- Here's my understanding of what we are trying to accomplish... Do we all agree?

- What would help us move forward: data? resources?

- Let's take a few minutes to hear everyone's suggestions about how this process might work better and what we should do next.

Dominating or reluctant participants —Some people might take more than their share of the discussion by talking too often, asserting superiority, telling lengthy stories, or not letting others finish. Sometimes humor can be used to discourage people from dominating. Others may rarely speak because they have difficulty getting in the conversation. Sometimes looking at people who don't speak can be a non-verbal way to include them. Asking quiet participants for their thoughts outside the group may lead to their participation within the group.

- How would we state the general problem? Could we leave out the details for a moment? Could we structure this part of the discussion by taking turns and hearing what everyone has to say?

- Let's check in with each other about how the process is working: Is everyone contributing to discussions? Can discussions be managed differently so we can all participate? Are we all listening to each other?

Digressions and tangents —Too many interesting side stories can be obstacles to group progress. It may be time to take another look at the agenda and assign time estimates to items. Try to summarize where the discussion was before the digression. Or, consider whether there is something making the topic easy to avoid.

- Can we go back to where we were a few minutes ago and see what we were trying to do ?