- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

4 The Ethics of Character Evidence

- Published: March 2015

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter considers the moral arguments against the use of bad character evidence in a criminal trial. It begins by looking at one of the challenges faced by these moral arguments: the need to explain their own defeasibility or limited applicability. It then examines moral accounts, all of which seem to revolve around the central theme of the significance of desistance from crime. The chapter concludes that arguments which have been put forward for a ‘moralized’ exclusionary rule are unconvincing.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Accessibility controls

Bad character evidence, introduction, the legal framework, the seven gateways, power of the court to stop the case, proving convictions and other reprehensible conduct, bad character of non-defendants.

The admissibility of bad character evidence in criminal proceedings is governed by Part 11 Criminal Justice Act 2003 (Sections 98 -113), section 99 of which abolished the existing common law rules. The only qualification to the abolition of the common law rules is in section 99(2) which, for the purposes of bad character evidence, allows for proof of a person’s bad character by the calling of evidence as to his reputation.

The provisions of the 2003 Act also do not affect section 27(3) of the Theft Act 1968 which makes provision for proof of guilty knowledge on a charge of handling stolen goods by proof of previous convictions for handling or theft.

“Bad character” evidence is defined in section 98 of the Act which provides that:

“References in this Chapter to evidence of a person’s ‘bad character’ are to evidence of, or of a disposition towards, misconduct on his part, other than evidence which –

- Has to do with the alleged facts of the offence with which the defendant is charged, or

- Is evidence of misconduct in connection with the investigation or prosecution of that offence”.

“Misconduct’ is defined in section 112 of the Act as “the commission of an offence or of other reprehensible behaviour” . What is capable of constituting reprehensible behaviour will be fact specific and has been held to include;

- Drinking to excess and taking illegal drugs - R v M [2014] EWCA Crim 1457

- Membership of a violent gang - R v Lewis [2014] EWCA Crim 48

‘Criminal proceedings’ are defined in section 112 as ‘criminal proceedings to which the strict rules of evidence apply’ and have been held to include:

- A trial or newton hearing - R v Bradley [2005] EWCA Crim 20

- A preparatory hearing (section 30 of the Criminal Procedure and Investigation Act 1996) - R v H [2006] 1 Cr App R 4

- A hearing pursuant to section 4A of the Criminal Procedure (Insanity) Act 1964 – finding of fact hearing further to a finding of unfit to plead - R v Chal [2007] EWCA Crim 2647

Evidence falling with section 98(b) would encompass evidence relating to, for example, the telling of lies in an interview or the intimidation of witnesses (where not the subject of a separate charge).

It is of crucial importance to identify what evidence “has to do” with the alleged facts of an offence because if it does relate to the alleged facts, it will not be subject to the statutory regime of gateways and safeguards provided by the Act.

An offence which could not be proved without reference to bad character would clearly be one that would fall within section 98(a) . Examples of these would include driving whilst disqualified contrary to section 103 of the Road Traffic Act 1988 or possession of a firearm having previously been convicted of an offence of imprisonment contrary to section 21 of the Firearms Act 1968 where the fact of a previous conviction constitutes an element of the actus reus .

In other cases where proof of bad character is not an essential element of the offence, the question of whether or not the evidence has to do with the facts of the offence is not always straightforward. In R v McNeill [2007] EWCA Crim 2927 it was said that

“the words of the statute ‘has to do with’ are words of prima facie broad application, albeit constituting a phrase that has to be construed in the overall context of the bad character provisions of the 2003 Act…..It would be a sufficient working model of these words if one said that they either clearly encompass evidence relating to the alleged facts of an offence which would have been admissible under the common law outside the context of bad character of propensity, even before the Act, or alternatively as embracing anything directly relevant to the offence charged, provided at any rate they were reasonably contemporaneous with and closely associated with its alleged facts ”.

The nexus envisaged by the court in McNeill was temporal (statement of a threat to kill made two days after an alleged offence of a threat to kill admissible under the terms of section 98 ). The temporal nexus was endorsed in R v Tirnaveanu [2007] EWCA Crim 1239 where the misconduct sought to be adduced showed little more than propensity (possession of papers showing involvement in illegal entry of Romanian nationals of occasions other than subject to the offence charged-if admissible at all then through one of the gateways-see below). More recent authorities have suggested that a temporal requirement is but one way of establishing a nexus; thus where the evidence is relied upon to establish motive, there is no such temporal requirement (see R v Sule [2012] EWCA Crim 1130 and R v Ditta [2016] EWCA Crim 8 ). However, as to evidence of motive, see below – ‘important explanatory evidence’.

In this regard, the case of R v Lunkulu [2015] EWCA Crim 1350 offers some assistance where it was stated that

“ Section 98(a) included no necessary temporal qualification and applied to evidence of incidents whenever they occurred so long as they were to do with the alleged facts of the offence” (evidence of previous shooting and conviction for attempted murder relevant to establish an on-going gang related feud where the issue was identity).

There is a fine line between evidence said to do with the facts of the alleged offence and evidence the admissibility of which may fall to be considered through one of the gateways. Thus in R v Okokono [2014] EWCA Crim 2521 evidence of a previous conviction for possession of a knife was considered to be ‘highly relevant’ to a charge of a gang related killing applying section 98(a) but would also have been admissible under one of the statutory gateways. See also R v M [2006] EWCA Crim 193 where the complainant in a rape case was cross examined about why she had, after an alleged rape, made no complaint and had got into a car with her attacker. That line of questioning permitted evidence of her account of previous threats to shoot her and her belief that M had a gun. The court said this evidence ‘had to do with’ the facts of the alleged offence but, if not, would have been admissible under gateway (c) as ‘important explanatory evidence’.

Care should be taken when considering what evidence to adduce as part of the Crown’s case and whether an application for the admission of bad character evidence is necessary. In some cases where there is some doubt about whether evidence can be said to be to do with the alleged facts, it may be appropriate for an application to be made in any event for the evidence to be adduced either as important explanatory evidence or evidence relevant to an important matter in issue between the prosecution and the defendant.

Defendant Bad Character Evidence

The admissibility of evidence that falls outside the definition of bad character within the meaning of section 98 is governed by section 101 of the Act which provides that

“In criminal proceedings evidence of the defendant’s bad character is admissible if, but only if –

- all parties to the proceedings agree to the evidence being admissible;

- the evidence is adduced by the defendant himself or is given in answer to a question asked by him in cross examination and intended to elicit it;

- it is important explanatory evidence;

- it is relevant to an important matter in issue between the defendant and the prosecution;

- it has substantial probative value in relation to an important matter in issue between the defendant and a co-defendant;

- it is evidence to correct a false impression given by the defendant; or

- the defendant has made an attack on another person’s character.

Agreement of the Parties – section 101(1)(a)

This provision enables matters to be admitted by agreement. It does not empower advocates to agree evidence between them which may require judicial control, for example, third party material disclosed in respect of a non-defendant – R v DJ [2010] EWCA Crim 385 – This case emphasized the need to always inform the judge of any proposed agreement between advocates as to the admissibility of bad character evidence which will enable the court to identify both relevance and purpose of the evidence.

Where there are multiple defendants, the consent of all accused is required – Ferdinand [2014] EWCA Crim 1243 .

Evidence adduced or elicited by the defendant – section 101(1)(b)

Evidence adduced through this gateway is limited to the purpose for which it was elicited.

Important Explanatory Evidence – section 101(1)(c)

This is an important gateway for the prosecution and there is considerable overlap with evidence that ‘has to do with’ the alleged facts of the offence with which a defendant is charged. It reflects broadly the common law rule under which evidence of background was admitted without which a case would be incomplete – see R v Pettman unreported May 2 1985.

S101(1)(c) should be considered together with section 102 which provides that;

“For the purposes of section 101(1)(c) evidence is important explanatory evidence if –

- without it, the court or jury would find it impossible or difficult properly to understand other evidence in the case, and

- its value for understanding the case as a whole is substantial.

The requirements of section 102 should be given proper consideration. Evidence that simply “fills out the picture” is not the same as saying that the rest of the picture is either impossible or difficult to see without it – see R v Lee (Peter Bruce) [2012] EWCA Crim 316

There may be an issue about whether evidence of motive is admissible through this gateway. Under the common law, evidence of motive was always admissible to show that it was more probable that it was the accused who had committed the offence and it was generally considered that such evidence would form part of the background and be explanatory evidence. However, the Court of Appeal in R v Sule ante held that such evidence had to do with the facts of the alleged offence and thereby fell within the scope of section 98 .

Care should be taken when considering the route to admissibility of bad character evidence not to seek admissibility through this gateway when the proper approach is gateway (d). The case of Leatham and Mallett [2017] EWCA Crim 42 is illustrative of the approach of the Court in the application of section 101(1)(c) and the relationship with section 101(1)(d) . In that case, L and M were charged with conspiracy to burgle based entirely on circumstantial evidence. The court admitted evidence of L’s previous convictions for similar offences on the basis it provided an explanation for what were otherwise completely incomprehensible explanations provided by both accused. The commentary in the Criminal Law Review [2017] Crim LR 788 illustrates the difficulties and complexity of the provision and its overlap with section 101(1)(d) – below.

Important matter in Issue between the Defendant and the Prosecution – section 101(1)(d)

The 2003 Act introduced a revolutionary change to the admissibility of bad character evidence in criminal proceedings. Whereas under the common law the premise was that evidence of bad character was inadmissible save for where the evidence was admissible as similar fact in accordance with the test in DPP v P [1991] 2 A.C. 447 and the limited instances permitted by the Criminal Evidence Act 1898, the 2003 Act presumes that all relevant evidence will be admissible, even if it is evidence of bad character, subject to the discretion of the court to exclude in cases where the prosecution seek to adduce the evidence( see below under ‘Fairness).

Thus, evidence of bad character is admissible where it is relevant to an important matter in issue between the prosecution and the defence and can be used, for example, to rebut the suggestion of coincidence (see R v Howe [2017] EWCA Crim 2400 – evidence of previous convictions for burglary probative of the identification of the accused on a charge of burglary) or to rebut a defence of innocent association (see R v Cambridge [2011] EWCA Crim 2009 – on a charge of possessing a firearm with intent to endanger life, evidence of a previous incident in which the accused had discarded an imitation firearm and for which he had received a formal warning was admissible to rebut the explanation proffered by the accused for his fingerprints being found on the outside and the inside of the bag in which the firearm the subject of the present charge was found) .

When seeking to admit evidence through this gateway, it is essential therefore that the issues in the case are identified and the relevance to that issue of the bad character evidence is clearly identified. For evidence to pass this gateway, it has to be relevant to an important matter in issue between the parties; this is defined in section 112 as meaning “a matter of substantial importance in the context of the case as a whole”. Thus prosecutors must not lose sight of the need to focus on the important issues in the case and should never seek to adduce bad character evidence as probative of peripheral or relatively unimportant issues in the context of the case as a whole.

One of the most radical departures from the common law was to permit evidence of propensity to be used as probative of an issue in the case. Section 103(1) provides that matters in issue between the defendant and the prosecution include –

- the question whether the defendant has a propensity to commit offences of the kind with which he is charged, except where his having such a propensity makes it no more likely that he is guilty of the offence;

- the question whether the defendant has a propensity to be untruthful, except where it is not suggested that the defendant’s case is untruthful in any respect.

By subsection 2

Where subsection (1)(a) applies, a defendant’s propensity to commit offences of the kind with which he is charged may (without prejudice to any other way of doing so) be established by evidence that he has been convicted of

- an offence of the same description as the one with which he is charged, or

- an offence of the same category as the one with which he is charged.

Subsection 4 provides that for the purposes of subsection (2) –

- two offences are of the same description as each other if the statement of the offence in a written charge or indictment would, in each case, be in the same terms;

- two offences are of the same category as each other if they belong to the same category of offences prescribed for the purposes of this section by an order made by the Secretary of State.

For offences of the same category under section 103(4)(b) , please refer to the Criminal Justice Act 2003 (Categories of Offences) Order 2004 (S.I. 2004 No 3346) and Parts 1 and 2 of the Schedule. Part 1 lists offences under the heading “Theft Category” and contains offences under the Theft Acts 1968 and 1978. Part 2 is headed “Sexual Offences (Persons under the age of 16) Category” and lists offences under the Sexual Offences Act 1956 and 2003 as well as under the Indecency with Children Act 1960, the Criminal Law Act 1977, the Mental Health Act 1959 and the Sexual Offences (Amendment) Act 2003.

The leading case on propensity evidence remains R v Hanson: R v Gilmour; R v P [2005] EWCA Crim 824 ; in brief, the Court of Appeal provided the following guidance;

- Does the history of conviction(s) establish a propensity to commit offences of the kind with which he is charged?;

- If so, does the propensity make it more likely that the defendant committed the crime?;

- There was no minimum number of events necessary to demonstrate such a propensity, though the fewer the number of convictions, the weaker was likely to be the evidence of propensity; a single previous conviction for an offence of the same description or category would often not show propensity but it might do so where, for example, it showed a tendency to unusual behaviour (see for example, R v Balazs [2014] EWCA Crim 947-single offence of rape admitted where it was of a strikingly similar nature of R v Bennabbou [2012] EWCA Crim 1256 - old conviction and dissimilar circumstances);

- The strength of the prosecution case must be considered; if there was no, or little, other evidence against a defendant it was unlikely to be just to admit his previous convictions whatever they were (see R v Darnley [2012] EWCA Crim 1148;

- It would often be necessary to examine each individual conviction rather than merely looking at the name of the offence.

The basis of admissibility for such evidence is, effectively, to rebut any defence of mistake or innocent association on the basis of unlikelihood of coincidence (see DPP v Boardman [1975] AC 421). See also R v Chopra [2007] 1 Cr App R 225.). See the following for illustrations of the application of propensity evidence as probative of an important matter in issue in the case;

- R v Suleman [2012] 2 Cr App R 30 – evidence of a series of similar offences such that the jury would be entitled to infer they were the work of the same person – issue of identity;

- R v O’Leary [2013] EWCA Crim 1371 – evidence in respect of each count that victim of fraud was a dementia sufferer cross admissible to rebut defence that accused believed victims to be compos mentis and as probative of deliberate targeting of vulnerable victims.

Where a prosecutor considers propensity evidence, it is essential not to lose sight of the need for relevance. Accordingly, in R v Samuel [2014] EWCA Crim 2349 - evidence of the accused’s previous convictions for assaulting his partner were not relevant to the issue in the case on a charge of assault which was whether he had the specific intent necessary where he claimed he was too intoxicated to form the necessary mens rea. This can be contrasted with R v B [2017] EWCA Crim 35 where, on charges of sexual offences and child cruelty committed against his children, evidence of previous assaults committed upon his wife were admitted to rebut his assertion that he was simply a strict disciplinarian by demonstrating his propensity to use excessive violence against members of his family.

Section 101(1)(d) is the relevant gateway for determining the issue of cross admissibility where there are multiple accusations against a defendant made by different complainants. Section 112(2) provides.

“Where a defendant is charged with two or more offences in the same criminal proceedings, this Chapter (except section 101(3) ) has effect as if each offence were charged in separate proceedings; and references to the offence with which the defendant is charged are to be read accordingly”.

Accordingly, where prosecutors seek cross-admissibility of a number of counts as probative of an issue in the case, a formal application will be necessary.

Previous acquittals are capable of being bad character evidence if the facts are relevant to an important matter in issue. The use of previous acquittals was thought to be objectionable until the decision of the House of Lords in Z [2000] 2 AC 483 where the evidence of three complainants who had each given evidence in three previous trials for rape was held to be admissible in a fourth rape trial to rebut the defence raised on the basis that the cumulative evidence possessed the degree of probative value required. However, where consideration is given to relying on conduct that has not resulted in a conviction, the case law directs that particular care is required. In R v McKenzie [2008] EWCA Crim 758 Toulson J emphasized the need to consider whether the admission of such evidence would result in the trial becoming unnecessarily complex as well as the need to avoid the litigation of satellite issues which would complicate the issues the jury had to decide.

The purpose of the bad character provisions is to assist in the evidence based conviction of the guilty without putting the innocent at risk of conviction by prejudice. Prosecution applications to adduce bad character evidence as being relevant to an important matter in issue between the prosecution and the defence and should not be made as a matter of routine simply because the defendant has previous convictions. An application should never be made to bolster a weak case.

- Collusion or Contamination

The probative value of a number of complainants who each give evidence of similar conduct committed against them by the accused is derived from the unlikelihood that a person would find himself falsely accused of the same or similar offence by a number of different and independent individuals. However, the probative value of such evidence is lost if there is contamination or collusion between complainants. Section 109 provides that references in the Act to the relevance or probative value of evidence which the parties seek to admit through the gateways are based on the assumption that it is true subject to the exception in section 109(2) where it appears that no court or jury could reasonably find it to be true.

- Propensity Evidence – Untruthfulness

Such evidence is unlikely to be limited to cases where lying is an element of the crime e.g. perjury – see R v Jarvis [2008] EWCA Crim 488 where the Court of Appeal, obiter, stated that there was no warrant in the statute for such a restrictive view of evidence demonstrating a propensity to untruthfulness (evidence of lying and dishonesty in relation to previous business dealings). See - Norris [2014] EWCA Crim 419 – evidence of previous sustained lying in a court context in mitigation.

Important Matter in Issue between defendant and co-defendant – section 101(1)(e)

By section 104(1)

“Evidence which is relevant to the question whether the defendant has a propensity to be untruthful is admissible on that basis under section 101(1)(e) only if the nature or conduct of his defence is such as to undermine the co-defendant’s defence.

By section 104(2)

“Only evidence –

- Which is to be (or has been) adduced by the co-defendant, or

- Which a witness is to be invited to give (or has given) in cross examination by the co-defendant,

is admissible under section 101(1)(e) ”,

This is the gateway intended to deal with ‘cut-throat’ defences. Application is made by the defence. Once the evidence meets the criteria for admissibility, there is no discretion to exclude.

Correcting a False Impression – section 101(1)(f)

Statutory guidance is provided by section 105 which provides that, for the purposes of section 101(1)(f) .

- The defendant gives a false impression if he is responsible for the making of an express or implied assertion which is apt to give the court or jury a false or misleading impression about the defendant;

- Evidence to correct such an impression is evidence which has probative value in correcting it.

A defendant is treated as being responsible for the making of an assertion of

- The assertion is made by the defendant in the proceedings (whether or not in evidence given by him),

- On being questioned under caution, before charge, about the offence with which he is being charged, or

- On being charged with the offence or officially informed that he might be prosecuted for it,

and evidence of the assertion is given in the proceedings.

- The assertion is made by a witness called by the defendant,

- The assertion is made by any witness in cross examination in response to a question asked by the defendant that is intended to elicit it, or is likely to do so, or

- The assertion was made by any person out of court, and the defendant adduces evidence of it in the proceedings. ( section 105(2) ).

Only prosecution evidence is admissible through this gateway i.e. evidence which is to be (or has been) adduced by the prosecution, or which a witness is to be invited to give (or has given) in cross examination by the prosecution ( section 112 ). Only evidence that is necessary to correct the false impression is admissible through this gateway ( sections 105(6) and (7) )

Section 105(3) permits a defendant to withdraw from an assertion or disassociate himself from it.

Attack on Another Person’s Character – section 101(1)(g)

By section 106 , for the purposes of section 101(1)(g) , a defendant makes an attack on another person’s character if

- He adduces evidence attacking the other person’s character,

- He (or any legal representative appointed under section 38(4) of the Youth Justice and Criminal Evidence Act 1999 to cross examine a witness in his interests) asks questions in cross examination that are intended to elicit such evidence, or are likely to do so, or

- On being questioned under caution, before charge, about the offence with which he is charged, or

- On being charged with the offence or officially informed that he might be prosecuted for it.

Evidence attacking another person’s character means evidence to the effect that the other person –

- Has committed an offence (whether a different offence from the one with which the defendant is charged or the same one), or

- Has behaved, or is disposed to behave, in a reprehensible way; and imputation about the other person means an assertion to that effect. ( Section 106(2) ).

Section 106(3) provides that only prosecution evidence is admissible under section 101(1)(g) .

The mere denial of the prosecution case will not be sufficient to trigger this gateway – see R v Fitzgerald [2017] EWCA Crim 556 of where it is being suggested not merely that prosecution witnesses are lying but have conspired to pervert the course of justice by putting their heads together to concoct a false allegation - R v Pedley [2014] EWCA Crim 848 .

Unlike section 105 , section 106 does not contain a provision allowing a defendant to disassociate himself from an imputation. Prosecutors should therefore be cautious when seeking to rely on this gateway on the basis of matters raised by the defendant outside the trial but not relied on in evidence. See the comments in R v Nelson [2006] EWCA Crim 3412 ; “It would have been improper for the prosecution to seek to get such comments before a jury simply to provide a basis for satisfying gateway (g) and getting the defendant's previous convictions put in evidence. Whilst it was not suggested that that had been the motivation of the prosecution in the present case, objectively speaking, that had to have been the situation which had arisen. It followed that that was not a proper basis for meeting the requirements of gateway (g) on admissibility”

Use of Bad Character Evidence

Once admitted, the weight to be attached to bad character evidence is a matter for the jury, subject to the judge’s power to stop a case where the evidence is contaminated (see section 107 – below). Once evidence has been admitted through one of the gateways, it can be used for any purpose for which it is relevant. See R v Highton [2005] 1 WLR 3472 . What is essential however is that the court should be directed clearly as to the reason for the admission of the evidence with an explanation of its relevance and the use to which such evidence can be put (see Chapter 12 of the Crown Court Compendium ).

Evidence upon which the prosecution seek to rely through gateways (d) or (g) is subject to section 101(3) which provides

“The court must not admit evidence under subsection (1)(d) or (g) if, on application by the defendant to exclude it, it appears to the court that the admission of the evidence would have such an adverse effect on the fairness of the proceedings that the court ought not to admit it”.

This exclusionary power comes into play on the application of the defence. The wording in section 101(3) – “must not admit” is stronger than the wording found in section 78 Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1978 (LINK) – “may refuse to allow” –see R v Hanson and R v Weir [2005] EWCA Crim 2866 . There is no specific exclusion of section 78 from the provisions of Part 11 of the 2003 Act but the preferred view now is that if the conditions under section 78 are satisfied, the Court has no discretion under section 78 – see R v Tirnaveanu . This is important because section 101(3) does not apply to gateways (c ) and (f) and any application by the defence would have to be made further to section 78 and it is only right that the discretion afforded to the court to exclude evidence upon which the prosecution propose to rely should be the same whatever route to admissibility.

It should be noted that section 78 cannot apply to evidence admitted via gateway (e) –evidence adduced on application by the co-defendant.

Section 103(3) of the Act, in relation to propensity evidence, provides that section 103(2) will not apply

“in the case of a particular defendant if the court is satisfied, by reason of the length of time since the conviction or for any other reason, that it would be unreasonable for it to apply in this case”.

Section 107 gives the court the power to discharge a jury or order an acquittal where evidence has been admitted through any of the gateways (c ) to (g) of section 101(1) where it is apparent that the evidence is contaminated and, as a consequence, any conviction would be unsafe.

To enable a court to determine whether previous convictions or other reprehensible behaviour are admissible through any of the gateways, it is important that the court is furnished with as much accurate information as possible. In some cases, the fact of a previous conviction or convictions will be sufficient to determine relevance and previous convictions can be proved by production of a certificate of conviction together with proof that the person named in the certificate is the person whose conviction is to be proved – section 73 Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984. In other cases however, the details of the previous convictions (or other reprehensible conduct) will be necessary to enable a judge to determine the admissibility of the bad character evidence. See R v M [2012] EWCA Crim 1588 where the Court of Appeal stated that it was imperative that the court is supplied with detailed and accurate information about the conduct to be relied upon.

Prosecutors should therefore seek from the police detailed information in the MG3 about the evidence said to amount to bad character. This should include not only the fact of the previous convictions but as much detail as possible. It will be good practice to obtain the original MG3, relevant statements and the accused’s response to the allegation in their police interview. If a person pleaded guilty, it should be clarified whether or not there was a basis of plea. If there was, the written document should be obtained. All of this material should be obtained as early as possible, preferably in advance of charge.

An accused is entitled to dispute the fact or facts of a conviction. It is expected that the accused should give proper notice of this objection in accordance with the Criminal Procedure Rules in force.

If the fact of conviction is disputed, section 74 PACE 1984 provides that a person’s conviction as proved by a certificate further to section 73 is proof that he did commit the offence of which he was convicted unless he proves that he did not commit the offence, the burden of proof being upon him. In R v C [2010] EWCA Crim 2971 the Court of Appeal provided guidance as to how this issue should be dealt with in the course of a trial to enable the court to achieve the overriding objective of the Criminal Procedure Rules which is that criminal cases be dealt with justly. This would include the provision of a detailed Defence Statement which would enable the prosecution to consider calling any evidence to confirm the guilt of the earlier convictions. A mere assertion that the fact or facts of previous convictions are incorrect will not suffice.

Where the facts of a previous conviction were disputed, clearly section 74 would be of little application. Guidance in such cases was provided in R v Humphris [2005] EWCA Crim 2030 where the Lord Chief Justice said

“[This case]… emphasises the importance of the Crown deciding that if they want more than the evidence of the conviction and the matters that can be formally established by relying on PACE ,they must ensure that they have available the necessary evidence to support what they require. That will normally require the availability of either a statement by the complainant relating to the previous convictions [in a sexual case] or the complainant to be available to give first-hand evidence of what happened”.

The court emphasized the need to avoid satellite litigation and in particular the need to avoid, if at all possible, the re-calling of witnesses to give evidence about matters the subject of previous convictions. The parties were reminded of the need to seek agreement.

If there is a dispute about previous convictions that cannot be resolved by agreed facts, prosecutors should give very careful consideration to appropriate witness care which will include arranging with the police a witness care plan with consideration being given to special measures applications. It may also be appropriate to have regard to the hearsay provisions of the Chapter 2 of Part 11 of the Criminal Justice Act 2003 .

Section 108 of the Act limits the admissibility of evidence of previous convictions as bad character evidence where the accused is charged with offences alleged to have been committed by them when aged 21 years or over and the previous conviction or convictions were for offences committed before the age of 14 to cases where

- Both of the offences are triable only on indictment, and

- The court is satisfied that the interests of justice require the evidence to be admissible.

A caution is capable of proving bad character. It can be the subject of dispute in the same way that a conviction may be disputed. In the event a caution is disputed by an accused, the court will exercise considerable care in admitting the caution as evidence of bad character particularly where the caution was accepted in the absence of legal advice. A conviction is significantly different to a caution and the court will carefully consider its powers of exclusion under section 101(3) - R v Olu [2010] EWCA Crim 2975 .

A Penalty Notice does not contain an admission of guilt and does not affect the good character of a person who accepts one – see R v Gore and Maher [2009] EWCA Crim 1424 . They are therefore inadmissible as evidence of bad character ( R v Hamer [2010] EWCA Crim 2053 ).

Prosecutors should give very careful consideration to seeking admission of convictions that are spent under the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act 1974. Section 7(2)(a) of the 1974 Act expressly excludes criminal proceedings from the operation of the general rule that a person whose convictions are spent is to be treated as a person of good character. However, some protection is afforded to a defendant by Criminal Practice Direction V, 21A.3 which provides that no one should refer in open court to a spent conviction without the authority of the judge which authority should not be given unless the interests of justice so require. Accordingly, cases where an application is made by the prosecution to adduce bad character evidence in relation to a spent conviction will be exceptional.

The admissibility of bad character evidence of non-defendants is governed by section 100 of the Act. This provides that such evidence of a person other than the accused is admissible if and only if –

- It is important explanatory evidence,

- Is a matter in issue in the proceedings, and

- Is of substantial importance in the context of the case as a whole, or

- All parties to the proceedings agree to the evidence being admissible.

Evidence is important explanatory evidence if, without it, the court or jury would find it impossible or difficult properly to understand other evidence in the case and its value for understanding the case as a whole is substantial ( section 100(2) ). This subsection mirrors the provision in section 101(1)(c) and it was intended that the same test would be of application to defendants and non-defendants alike.

Section 100(3) of the Act directs the court, when assessing the probative value of the evidence for the purposes of section 100(1)(b) to have regard to

- The nature and number of events, or other things, to which the evidence relates;

- When those events or things are alleged to have happened or existed;

- The evidence is evidence of a person’s misconduct, and

- It is suggested that the evidence has probative value by reason of similarity between that misconduct and other alleged misconduct

the nature and extent of the similarities and dissimilarities between each of the alleged instances of misconduct;

- The evidence is evidence of a person’s misconduct,

- It is suggested that that person is also responsible for the misconduct charged, and

- The identity of the person responsible for the misconduct charged is disputed

the extent to which the evidence shows or tends to show that the same person was responsible each time.

Evidence of a non-defendant’s bad character cannot be adduced without the leave of the court unless the parties agree. However, once a judge has determined that the criteria for admissibility are met, there is no exclusionary discretion save for the exercise of the case management powers governing, for example, manner and length of cross examination ( R v Brewster and Cromwell [2010] EWCA Crim 1194 ). Prosecutors should only agree to the admission of bad character when one or both of the other gateways are satisfied or it is in the interests of justice to do so.

This section applies to both witnesses and those not called to give evidence except where the issue is one of credibility as the credibility of a non-witness will never be a matter in issue. The section also covers those who are deceased.

The creditworthiness of a witness is a “matter in issue in the proceedings” for the purposes of section 100(1)(b) (see R v S (Andrew) [2006] EWCA Crim 1303 ) However, such bad character evidence will only be admissible if it is “of substantial importance in the context of the case as a whole”.

A successful application by the defence may provide the basis for an application for the admission of defendant bad character under section 101(1)(g) of the Act ( an attack on another person’s character) subject to the court’s discretion to exclude under section 101(3) .

In cases where cross examination is restricted by statute, such as section 41 of the Youth Justice and Criminal Evidence Act 1999 where, upon the trial of a sexual offence, the defence seek to cross examine the complainant as to sexual behaviour or to adduce evidence on that matter, if the matter falls within the definition of bad character evidence, the judge will have to be satisfied as to both the requirements of section 100 and section 41.

The procedure for the admissibility of bad character evidence is governed by Part 21 of the Criminal Procedure Rules.. The importance of complying with the rules governing procedure was stressed in R v Bovell; R v Dowds [2005] EWCA Crim 1091 and subsequent cases have stressed the need to provide information in relation to convictions and other evidence of bad character in good time.

A party wishing to adduce evidence of a defendant’s bad character must serve notice in accordance with CrimPR 21.4 on the court officer and each other party:

- Not more than 20 business days after the defendant pleads not guilty in the magistrates’ court, or

- Not more than 10 business days after the defendant pleads not guilty in the Crown Court.

A party who objects to the admission of the bad character evidence must apply to the court to determine the objection and serve the application not more than 10 business days after after service of the notice.

Notice must be given by a defendant, either orally or in writing, of an intention to adduce evidence of his own bad character as soon as reasonably practicable any in any event before the evidence is introduced by the defendant or in reply to a question asked by the defendant of another party’s witness in order to obtain evidence (CrimPR 21.4(8)).

A court must give reasons for any decision to either allow or refuse the application (Crim PR 21.5). This requirement is imposed by section 110 of the Act.

The court has power, under CrimPR 21.6 to vary the requirements under this Part of the Criminal Procedure Rules which includes a power to dispense with a requirement for notice. Any party seeking an extension must apply when serving the application and explain the delay.

These can be accessed in the Forms section of the Criminal Procedure Rules.

The Code for Crown Prosecutors

The Code for Crown Prosecutors is a public document, issued by the Director of Public Prosecutions that sets out the general principles Crown Prosecutors should follow when they make decisions on cases.

Continue reading

Prosecution guidance

This guidance assists our prosecutors when they are making decisions about cases. It is regularly updated to reflect changes in law and practice.

Help us to improve our website; let us know what you think by taking our short survey

Go to the survey >

How to Write a Character Analysis Essay

A character analysis essay is a challenging type of essay students usually write for literature or English courses. In this article, we will explain the definition of character analysis and how to approach it. We will also touch on how to analyze characters and guide you through writing character analysis essays.

Typically, this kind of writing requires students to describe the character in the story's context. This can be fulfilled by analyzing the relationship between the character in question and other personas. Although, sometimes, giving your personal opinion and analysis of a specific character is also appropriate.

Let's explain the specifics of how to do a character analysis by getting straight to defining what is a character analysis. Our term paper writers will have you covered with a thorough guide!

What Is a Character Analysis Essay?

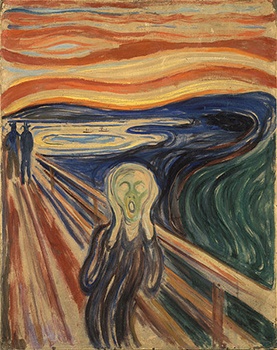

The character analysis definition explains the in-depth personality traits and analyzes characteristics of a certain hero. Mostly, the characters are from literature, but sometimes other art forms, such as cinematography. In a character analysis essay, your main job is to tell the reader who the character is and what role they play in the story. Therefore, despite your personal opinion and preferences, it is really important to use your critical thinking skills and be objective toward the character you are analyzing. A character analysis essay usually involves the character's relationship with others, their behavior, manner of speaking, how they look, and many other characteristics.

Although it's not a section about your job experience or education on a resume, sometimes it is appropriate to give your personal opinion and analysis of a particular character.

What Is the Purpose of a Character Analysis Essay

More than fulfilling a requirement, this type of essay mainly helps the reader understand the character and their world. One of the essential purposes of a character analysis essay is to look at the anatomy of a character in the story and dissect who they are. We must be able to study how the character was shaped and then learn from their life.

A good example of a character for a character analysis essay is Daisy Buchanan from 'The Great Gatsby.' The essay starts off by explaining who Daisy is and how she relates to the main character, Jay Gatsby. Depending on your audience, you need to decide how much of the plot should be included. If the entire class writes an essay on Daisy Buchanan, it is logical to assume everyone has read the book. Although, if you know for certain that your audience has little to no knowledge of who she is, it is crucial to include as much background information as possible.

After that, you must explain the character through certain situations involving her and what she said or did. Make sure to explain to the reader why you included certain episodes and how they have showcased the character. Finally, summarize everything by clearly stating the character's purpose and role in the story.

We also highly recommend reading how to write a hook for an essay .

Still Need Help with Your Character Analysis Essay?

Different types of characters.

To make it clear how a reader learns about a character in the story, you should note that several characters are based on their behaviors, traits, and roles within a story. We have gathered some of them, along with vivid examples from famous literature and cinema pieces:

Types of Characters

- Major : These are the main characters; they run the story. Regularly, there are only one or two major characters. Major characters are usually of two types: the protagonist – the good guy, and the antagonist: the bad guy or the villain.

- Protagonist (s) (heroes): The main character around whom most of the plot revolves.

For example, Othello from Shakespeare's play, Frodo from The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien, Harry Potter from the Harry Potter series by J.K. Rowling, and Elizabeth Bennet from 'Pride and Prejudice' by Jane Austen.

- Antagonist (s): This is the person that is in opposition to the protagonist. This is usually the villain, but it could also be a natural power, set of circumstances, majestic being, etc.

For example, Darth Vader from the Star Wars series by George Lucas, King Joffrey from Game of Thrones, or the Wicked Queen from 'Snow White and Seven Dwarfs.'

- Minor : These characters help tell the major character's tale by letting them interact and reveal their personalities, situations, and/or stories. They are commonly static (unchanging). The minor characters in The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien would be the whole Fellowship of the ring. In their own way, each member of the Fellowship helps Frodo get the ring to Mordor; without them, the protagonist would not be a protagonist and would not be able to succeed. In the Harry Potter series by J.K. Rowling, minor characters are Ronald Weasley and Hermione Granger. They consistently help Harry Potter on his quests against Voldemort, and, like Frodo, he wouldn't have succeeded without them.

On top of being categorized as a protagonist, antagonist, or minor character, a character can also be dynamic, static, or foil.

- Dynamic (changing): Very often, the main character is dynamic.

An example would also be Harry Potter from the book series by J.K. Rowling. Throughout the series, we see Harry Potter noticing his likeness to Voldemort. Nevertheless, Harry resists these traits because, unlike Voldemort, he is a good person and resists any desire to become a dark wizard.

- Static (unchanging): Someone who does not change throughout the story is static.

A good example of a static character is Atticus Finch from “How to Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee. His character and views do not change throughout the book. He is firm and steady in his beliefs despite controversial circumstances.

- Foils : These characters' job is to draw attention to the main character(s) to enhance the protagonist's role.

A great example of a foil charact e r is Dr. Watson from the Sherlock Holmes series by Arthur Conan Doyle.

How to Analyze a Character

While preparing to analyze your character, make sure to read the story carefully.

- Pay attention to the situations where the character is involved, their dialogues, and their role in the plot.

- Make sure you include information about what your character achieves on a big scale and how they influence other characters.

- Despite the categories above, try thinking outside the box and explore your character from around.

- Avoid general statements and being too basic. Instead, focus on exploring the complexities and details of your character(s).

How to Write a Character Analysis Essay?

To learn how to write a character analysis essay and gather a more profound sense of truly understanding these characters, one must completely immerse themself in the story or literary piece.

- Take note of the setting, climax, and other important academic parts.

- You must be able to feel and see through the characters. Observe how analysis essay writer shaped these characters into life.

- Notice how little or how vast the character identities were described.

- Look at the characters' morals and behaviors and how they have affected situations and other characters throughout the story.

- Finally, observe the characters whom you find interesting.

Meanwhile, if you need help writing a paper, leave us a message ' write my paper .'

How Do You Start a Character Analysis Essay

When writing a character analysis essay, first, you have to choose a character you'd like to write about. Sometimes a character will be readily assigned to you. It's wise to consider characters who play a dynamic role in the story. This will captivate the reader as there will be much information about these personas.

Read the Story