- Skip to Nav

- Skip to Main

- Skip to Footer

Why PE matters for student academics and wellness right now

Please try again

This story about PE teachers was produced by The Hechinger Report , a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s newsletter .

Amanda Amtmanis, an elementary physical education instructor in Middletown, Connecticut, handed out cards with QR codes to a class of third graders, and told them to start running.

The kids sprinted off around the baseball field in a light drizzle, but by the end of the first lap, a fifth of a mile, many were winded and walking. They paused to scan the cards, which track their mileage, on their teacher’s iPad and got some encouragement from an electronic coach — “Way to run your socks off!” or “Leave it all on the track!”

A boy in a red Nike shirt surged ahead, telling Amtmanis his goal was to run 5 miles. “Whoa, look at Dominic!” another boy exclaimed.

“We don’t need to compare ourselves to others,” Amtmanis reminded him.

The third graders finished a third lap, alternating running and walking, and were about to start on a scavenger hunt when the rain picked up, forcing them inside. Amtmanis thanked her students for their willingness to adjust — a skill many of them have practiced far more often than running these past 18 months.

The full impact of the pandemic on kids’ health and fitness won’t be known for some time. But it’s already caused at least a short-term spike in childhood obesity Rates of overweight and obesity in 5- through 11-year-olds rose nearly 10 percentage points in the first few months of 2020.

Amtmanis’ “mileage club,” which tracks students’ running, both in and out of school, and rewards them with Pokémon cards when they hit certain targets, is an example of how PE teachers around the country are trying to get kids back in shape.

But inclement weather isn’t the only thing PE teachers are up against as they confront what might be called “physical learning loss.” Physical education as a discipline has long fought to be taken as seriously as its academic counterparts. Even before the pandemic, fewer than half the states set any minimum amount of time for students to participate in physical education, according to the Society of Health and Physical Educators (SHAPE), which represents PE and health instructors.

Now, as schools scramble to help kids catch up academically, there are signs that PE is taking a back seat to the core subjects yet again. In some California schools, administrators are shifting instructional minutes from PE to academic subjects — or canceling class altogether so PE teachers can sub for classroom teachers; in others, they’re growing class sizes in the gym, so they can shrink them in the classroom.

Meanwhile, innovative instructors like Amtmanis, who has worked in her district for more than 20 years, are struggling to get their ideas off the ground. Over the summer, the principal of Macdonough Elementary, one of two schools where Amtmanis teaches, approved her request to participate in another running program called The Daily Mile, in which kids walk or run 15 minutes a day during school hours.

Daily running breaks “boost attentiveness, which has positive effects on academics,” Amtmanis argued.

But two weeks into the school year, not a single teacher had bought into the idea.

“The issue is their packed schedule,” Amtmanis said.

Last year, many schools conducted gym class remotely, with students joining in from their bedrooms and living rooms.

The online format presented several challenges. Many students lacked the equipment, space, or parental support to participate fully. And many instructors grappled with how to teach and assess motor skills and teamwork online.

Though instructors found creative ways to keep students moving — substituting rolled-up socks for balls, and “disguising fitness” in scavenger hunts and beat-the-teacher challenges — they still fretted that online gym wasn’t giving students the same benefits as in-person classes.

Compounding their concern was the fact that many students were also missing out on recess and extracurricular sports.

In a March 2021 survey conducted by the Cooper Institute, maker of the popular FitnessGram assessments, close to half the PE teachers and school and district administrators responding said their students were “significantly less” physically active during their schools’ closure than before it.

Schools that reopened last year faced their own set of challenges, including bans on shared equipment that made even a simple game of catch impossible. Schools that were open for in-person learning were also much more likely to cut back on PE instructional time, or eliminate it altogether, the survey found.

The consequences of these reductions in physical activity are hard to quantify, especially since many schools suspended fitness testing during the pandemic and have yet to resume it, but some PE teachers say they’re seeing more kids with locomotor delays and weaker stamina than normal.

“The second graders are like first graders, and some are even like kindergarteners,” said Robin Richardson, an elementary PE instructor in Kentucky. They can jump and hop, she said, but they can’t leap. They’re exhausted after 20 seconds of jumping jacks.

An unusually high number of Richardson’s first graders can’t skip or do windmills. Some lack the spatial awareness that’s essential to group games.

“They don’t know how to move without running into each other,” she said.

Other instructors are seeing an increase in cognitive issues, such as difficulty paying attention or following directions, particularly among kids who remained remote for most or all of last year.

Kyle Bragg, an elementary PE instructor in Arizona, has seen kids sitting with their backs to him, staring off into space when he’s talking. “I say ‘Knees, please,’ so they spin around to face me,” he said.

And some PE teachers say their students’ social-emotional skills have suffered more than their gross motor skills. “They forgot how to share; how to be nice to each other; how to relate to each other,” said Donn Tobin, an elementary PE instructor in New York.

PE has a key role to play in boosting those skills, which affect how kids interact in other classes, said Will Potter, an elementary PE teacher in California.

“We’re uniquely situated to handle the social-emotional needs that came out of the pandemic, in a way classroom teachers are not,” Potter said.

Amtmanis, for her part, worries about her students’ mental health. She sees the little signs of strain daily — the kid who got upset because he couldn’t pick his group, for example, and the one who was distressed that his Mileage Club card had gotten mixed up in the front office.

“Their emotional reserves are low,” she said.

Yet not all instructors are reporting drops in their students’ fitness and skill development. Teachers in some middle- and upper-income districts said they haven’t noticed much of a change at all. In some communities, families seemed to spend more time outdoors.

“We saw the skyrocketing sale of bicycles, we saw families going for walks,” said Dianne Wilson-Graham, executive director of the California Physical Education and Health Project.

But in Title I schools like Macdonough, where more than half the students are low-income, some kids didn’t even have access to a safe place to exercise or play during school closures.

“Not only are they not in soccer leagues, but sometimes they don’t even have a park,” Amtmanis said.

Amtmanis came up with the idea of doing the Daily Mile after spring fitness tests revealed drops in her students’ strength, flexibility and endurance.

But many schools still aren’t sure how much physical learning loss their students have experienced as a result of the pandemic. Most schools pressed pause on fitness testing last year, and some elementary-school instructors are reluctant to restart it. They say the tests aren’t valid with young children, even in ordinary times, and argue the time they take could be better spent on Covid catch-up.

Andjelka Pavlovic, director of research and education for the Cooper Institute, said its tests are scientifically proven to be valid for students who are 10 and up, or roughly starting in fourth grade.

Fitness testing requirements vary by state, county or even district. Some states specify how often students must be tested; others leave it largely to the teacher.

Bragg, the Arizona teacher, said he has put testing “on the backburner” because “right now it’s not at the forefront of what’s important.”

Richardson said she is avoiding testing because she doesn’t want to use up precious instructional time or demoralize her students. “I want my kids to enjoy movement,” she said. If they perform poorly on the tests, “they may not feel as strong.”

In Connecticut, where schools are required to test fourth graders’ fitness annually, Amtmanis approached testing cautiously last year. She didn’t want to embarrass her students, so she made it into a series of games.

Instead of Sit-and-Reach, they had a “flexibility contest,” in which kids broke into teams for tag then had to perform stretches if they were tagged. She measured the distances stretched with curling ribbon, tied the ribbons together, and attached a balloon to the end. The team whose balloon soared the highest won fidget putty.

Pushups became a Bingo game, with the center space representing pushups.

“My goal was to get through it without ever using the words ‘fitness” or ‘testing,’” she said.

As the pandemic drags on, some instructors are taking a similar approach to fitness remediation and acceleration.

Bragg likes a warmup called “ Touch Spots ,” in which first graders listen as the instructor reads off the name of a color, then run and touch a corresponding dot on the floor. It works on reaction time, cardiovascular endurance, spatial awareness and sequencing — but the kids don’t know that.

“Students are having so much fun that they don’t realize how much fitness they are doing,” Bragg said.

Differentiation — tailoring instruction to meet individual students’ needs — has become even more essential, with former remote learners often lagging behind their in-person peers, Bragg said.

When playing catch, for example, he offers his students different sized balls — the smaller ones are more challenging.

Potter, the California teacher, spent the first two weeks of school teaching his students how to connect with their partners, stressing the importance of eye contact and body language.

“When you’re on Zoom, you look at the camera to make eye contact,” he said. “It’s a very different environment.”

Bragg reminds his students how to include kids who are standing on the sidelines, modeling excited body language and tone of voice. Lately, he’s noticed that kids who were remote last year are being excluded from groups.

“Social interaction needs to be practiced, just like how to throw a ball,” he said.

Richardson, the Kentucky PE teacher, is trying to build up her students’ stamina gradually, through progressively longer intervals of exercise.

But she works in a school with pods, so she sees each group of kids for five consecutive days, every third week. The two weeks in between, she has to hope that teachers will provide recess and “movement breaks.” She’s trying to get them to give kids breaks “when they get glassy-eyed and frustrated.”

Recently, Richardson was at a staff training session at which depleted teachers were “popping candy in the back.” When she raised her hand and requested a break in the training, her colleagues cheered. She told them to remember how they felt when their students return to the building.

“I always say, ‘If your bum is numb, your brain is the same,’” she said.

Convincing classroom teachers to set aside more time for movement can be challenging, though. As students return from months of online learning, teachers are under enormous pressure to get them caught up academically.

Kate Cox, an elementary and middle-school PE teacher in California, wishes schools would “realize what they’re missing when they cut PE because of learning loss in other areas.” Physical education is “readying their minds and bodies to be more successful in other areas,” Cox said.

Terri Drain, the president of SHAPE, argued that schools fail students when they treat physical learning loss as less serious than its academic counterpart.

“In the primary grades, children develop fundamental motor skills, such as throwing, catching, running, kicking and jumping,” she said. Unless schools commit to helping kids catch up, “the impacts of this ‘missed learning’ will be lifelong.”

In Connecticut, Amtmanis hasn’t given up on convincing teachers to carve out time for the Daily Mile. She recently sent them a list of suggestions on how to fit 15 minutes of running into the day, including by incorporating it as an active transition between academic blocks.

“While it may seem like there aren’t minutes to spare,” she wrote, “the energizing effect of the active transition should result in more on-task behavior and more efficient working.”

In the meantime, Amtmanis plans to keep using the mileage club to motivate her students to run and to monitor their progress.

“I don’t want to call attention to the fact that not everyone is fit,” she said. “This is an unobtrusive way to keep the data.”

Physical education for healthier, happier, longer and more productive living

The time children and adults all over the world spend engaging in physical activity is decreasing with dire consequences on their health, life expectancy, and ability to perform in the classroom, in society and at work.

In a new publication, Quality Physical Education, Guidelines for Policy Makers , UNESCO urges governments and educational planners to reverse this trend, described by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a pandemic that contributes to the death of 3.2 million people every year, more than twice as many as die of AIDS.

The Guidelines will be released on the occasion of a meeting of UNESCO’s Intergovernmental Committee for Physical Education and Sport (CIGEPS) in Lausanne, Switzerland, (28-30 January).*

UNESCO calls on governments to reverse the decline in physical education (PE) investment that has been observed in recent years in many parts of the world, including some of the wealthiest countries. According to European sources, for example, funding and time allocation for PE in schools has been declining progressively over more than half of the continent, and conditions are not better in North America.

The new publication on PE, produced in partnership with several international and intergovernmental organizations**, advocates quality physical education and training for PE teachers. It highlights the benefits of investing in PE versus the cost of not investing (cf self-explanatory infographics ).

“The stakes are high,” says UNESCO Director-General Irina Bokova. “Public investment in physical education is far outweighed by high dividends in health savings and educational objectives. Participation in quality physical education has been shown to instil a positive attitude towards physical activity, to decrease the chances of young people engaging in risky behaviour and to impact positively on academic performance, while providing a platform for wider social inclusion.”

The Guidelines seek to address seven areas of particular concern identified last year in UNESCO’s global review of the state of physical education , namely: 1. Persistent gaps between PE policy and implementation; 2. Continuing deficiencies in curriculum time allocation; 3. Relevance and quality of the PE curriculum; 4. Quality of initial teacher training programmes; 5. Inadequacies in the quality and maintenance of facilities; 6. Continued barriers to equal provision and access for all; 7. Inadequate school-community coordination.

The recommendations to policy-makers and education stake-holders are matched by case studies about programmes, often led by community-based nongovernmental organizations. Success stories in Africa, North and Latin America, Asia and Europe illustrate what can be achieved by quality physical education: young people learn how to plan and monitor progress in reaching a goal they set themselves, with a direct impact on their self-confidence, social skills and ability to perform in the classroom.

While schools alone cannot provide the full daily hour of physical activity recommended for all young people, a well-planned policy should promote PE synergies between formal education and the community. Experiences such as Magic Bus (India) which uses physical activity to help bring school drop outs back to the classroom highlight the potential of such school-leisure coordination.

The publication promotes the concept of “physical literacy,” defined by Canada’s Passport for Life organization of physical and health educators as the ability to move “with competence and confidence in a wide variety of physical activities in multiple environments that benefit the healthy development of the whole person. Competent movers tend to be more successful academically and socially. They understand how to be active for life and are able to transfer competence from one area to another. Physically literate individuals have the skills and confidence to move any way they want. They can show their skills and confidence in lots of different physical activities and environments; and use their skills and confidence to be active and healthy.”

For society to reap the benefit of quality physical education, the guidelines argue, planners must ensure that it is made available as readily to girls as it is to boys, to young people in school and to those who are not.

The Guidelines were produced at the request of UNESCO’s Intergovernmental Committee for Physical Education and Sport (CIGEPS) and participants at the Fifth International Conference of Ministers and Senior Officials Responsible for Physical Education and Sport (Berlin 2013). UNESCO and project partners will proceed to work with a number of countries that will engage in a process of policy revision in this area, as part of UNESCO’s work to support national efforts to adapt their educational systems to today’s needs (see Quality physical education contributes to 21st century education ).

Media contact: Roni Amelan, UNESCO Press Service, r.amelan(at)unesco.org , +33 (0)1 45 68 16 50

Photos are available here: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/media-services/multimedia/photos/photo-gallery-quality-physical-education/

* More about the CIGEPS meeting

** The European Commission, the International Council of Sport Science and Physical Education (ICSSPE), the International Olympic Committee (IOC), UNDP, UNICEF, UNOSDP and WHO.

Related items

- Country page: Switzerland

Other recent news

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Health Education Research

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction.

- < Previous

‘Physical education makes you fit and healthy’. Physical education's contribution to young people's physical activity levels

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

S. Fairclough, G. Stratton, ‘Physical education makes you fit and healthy’. Physical education's contribution to young people's physical activity levels, Health Education Research , Volume 20, Issue 1, February 2005, Pages 14–23, https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyg101

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The purpose of this study was to assess physical activity levels during high school physical education lessons. The data were considered in relation to recommended levels of physical activity to ascertain whether or not physical education can be effective in helping young people meet health-related goals. Sixty-two boys and 60 girls (aged 11–14 years) wore heart rate telemeters during physical education lessons. Percentages of lesson time spent in moderate-and-vigorous (MVPA) and vigorous intensity physical activity (VPA) were recorded for each student. Students engaged in MVPA and VPA for 34.3 ± 21.8 and 8.3 ± 11.1% of lesson time, respectively. This equated to 17.5 ± 12.9 (MVPA) and 3.9 ± 5.3 (VPA) min. Boys participated in MVPA for 39.4 ± 19.1% of lesson time compared to the girls (29.1 ± 23.4%; P < 0.01). High-ability students were more active than the average- and low-ability students. Students participated in most MVPA during team games (43.2 ± 19.5%; P < 0.01), while the least MVPA was observed during movement activities (22.2 ± 20.0%). Physical education may make a more significant contribution to young people's regular physical activity participation if lessons are planned and delivered with MVPA goals in mind.

Regular physical activity participation throughout childhood provides immediate health benefits, by positively effecting body composition and musculo-skeletal development ( Malina and Bouchard, 1991 ), and reducing the presence of coronary heart disease risk factors ( Gutin et al. , 1994 ). In recognition of these health benefits, physical activity guidelines for children and youth have been developed by the Health Education Authority [now Health Development Agency (HDA)] ( Biddle et al. , 1998 ). The primary recommendation advocates the accumulation of 1 hour's physical activity per day of at least moderate intensity (i.e. the equivalent of brisk walking), through lifestyle, recreational and structured activity forms. A secondary recommendation is that children take part in activities that help develop and maintain musculo-skeletal health, on at least two occasions per week ( Biddle et al. , 1998 ). This target may be addressed through weight-bearing activities that focus on developing muscular strength, endurance and flexibility, and bone health.

School physical education (PE) provides a context for regular and structured physical activity participation. To this end a common justification for PE's place in the school curriculum is that it contributes to children's health and fitness ( Physical Education Association of the United Kingdom, 2004 ; Zeigler, 1994 ). The extent to which this rationale is accurate is arguable ( Koslow, 1988 ; Michaud and Andres, 1990 ) and has seldom been tested. However, there would appear to be some truth in the supposition because PE is commonly highlighted as a significant contributor to help young people achieve their daily volume of physical activity ( Biddle et al. , 1998 ; Corbin and Pangrazi, 1998 ). The important role that PE has in promoting health-enhancing physical activity is exemplified in the US ‘Health of the Nation’ targets. These include three PE-associated objectives, two of which relate to increasing the number of schools providing and students participating in daily PE classes. The third objective is to improve the number of students who are engaged in beneficial physical activity for at least 50% of lesson time ( US Department of Health and Human Services, 2000 ). However, research evidence suggests that this criterion is somewhat ambitious and, as a consequence, is rarely achieved during regular PE lessons ( Stratton, 1997 ; US Department of Health and Human Services, 2000 ; Levin et al. , 2001 ; Fairclough, 2003a ).

The potential difficulties of achieving such a target are associated with the diverse aims of PE. These aims are commonly accepted by physical educators throughout the world ( International Council of Sport Science and Physical Education, 1999 ), although their interpretation, emphasis and evaluation may differ between countries. According to Simons-Morton ( Simons-Morton, 1994 ), PE's overarching goals should be (1) for students to take part in appropriate amounts of physical activity during lessons, and (2) become educated with the knowledge and skills to be physically active outside school and throughout life. The emphasis of learning during PE might legitimately focus on motor, cognitive, social, spiritual, cultural or moral development ( Sallis and McKenzie, 1991 ; Department for Education and Employment/Qualifications and Curriculum Authority, 1999 ). These aspects may help cultivate students' behavioural and personal skills to enable them to become lifelong physical activity participants [(thus meeting PE goal number 2 ( Simons-Morton, 1994 )]. However, to achieve this, these aspects should be delivered within a curriculum which provides a diverse range of physical activity experiences so students can make informed decisions about which ones they enjoy and feel competent at. However, evidence suggests that team sports dominate English PE curricula, yet bear limited relation to the activities that young people participate in, out of school and after compulsory education ( Sport England, 2001 ; Fairclough et al. , 2002 ). In order to promote life-long physical activity a broader base of PE activities needs to be offered to reinforce the fact that it is not necessary for young people to be talented sportspeople to be active and healthy.

While motor, cognitive, social, spiritual, cultural and moral development are valid areas of learning, they can be inconsistent with maximizing participation in health-enhancing physical activity [i.e. PE goal number 1 ( Simons-Morton, 1994 )]. There is no guidance within the English National Curriculum for PE [NCPE ( Department for Education and Employment/Qualifications and Curriculum Authority, 1999 )] to inform teachers how they might best work towards achieving this goal. Moreover, it is possible that the lack of policy, curriculum development or teacher expertise in this area contributes to the considerable variation in physical activity levels during PE ( Stratton, 1996a ). However, objective research evidence suggests that this is mainly due to differences in pedagogical variables [i.e. class size, available space, organizational strategies, teaching approaches, lesson content, etc. ( Borys, 1983 ; Stratton, 1996a )]. Furthermore, PE activity participation may be influenced by inter-individual factors. For example, activity has been reported to be lower among students with greater body mass and body fat ( Brooke et al. , 1975 ; Fairclough, 2003c ), and higher as students get older ( Seliger et al. , 1980 ). In addition, highly skilled students are generally more active than their lesser skilled peers ( Li and Dunham, 1993 ; Stratton, 1996b ) and boys tend to engage in more PE activity than girls ( Stratton, 1996b ; McKenzie et al. , 2000 ). Such inter-individual factors are likely to have significant implications for pedagogical practice and therefore warrant further investigation.

In accordance with Simons-Morton's ( Simons-Morton, 1994 ) first proposed aim of PE, the purpose of this study was to assess English students' physical activity levels during high school PE. The data were considered in relation to recommended levels of physical activity ( Biddle et al. , 1998 ) to ascertain whether or not PE can be effective in helping children be ‘fit and healthy’. Specific attention was paid to differences between sex and ability groups, as well as during different PE activities.

Subjects and settings

One hundred and twenty-two students (62 boys and 60 girls) from five state high schools in Merseyside, England participated in this study. Stage sampling was used in each school to randomly select one boys' and one girls' PE class, in each of Years 7 (11–12 years), 8 (12–13 years) and 9 (13–14 years). Three students per class were randomly selected to take part. These students were categorized as ‘high’, ‘average’ and ‘low’ ability, based on their PE teachers' evaluation of their competence in specific PE activities. Written informed consent was completed prior to the study commencing. The schools taught the statutory programmes of study detailed in the NCPE, which is organized into six activity areas (i.e. athletic activities, dance, games, gymnastic activities, outdoor activities and swimming). The focus of learning is through four distinct aspects of knowledge, skills and understanding, which relate to; skill acquisition, skill application, evaluation of performance, and knowledge and understanding of fitness and health ( Department for Education and Employment/Qualifications and Curriculum Authority, 1999 ). The students attended two weekly PE classes in mixed ability, single-sex groups. Girls and boys were taught by male and female specialist physical educators, respectively.

Instruments and procedures

The investigation received ethical approval from the Liverpool John Moores Research Degrees Ethics Committee. The study involved the monitoring of heart rates (HRs) during PE using short-range radio telemetry (Vantage XL; Polar Electro, Kempele, Finland). Such systems measure the physiological load on the participants' cardiorespiratory systems, and allow analysis of the frequency, duration and intensity of physical activity. HR telemetry has been shown to be a valid and reliable measure of young people's physical activity ( Freedson and Miller, 2000 ) and has been used extensively in PE settings ( Stratton, 1996a ).

The students were fitted with the HR telemeters while changing into their PE uniforms. HR was recorded once every 5 s for the duration of the lessons. Telemeters were set to record when the teachers officially began the lessons, and stopped at the end of lessons. Total lesson ‘activity’ time was the equivalent of the total recorded time on the HR receiver. At the end of the lessons the telemeters were removed and data were downloaded for analyses. Resting HRs were obtained on non-PE days while the students lay in a supine position for a period of 10 min. The lowest mean value obtained over 1 min represented resting HR. Students achieved maximum HR values following completion of the Balke treadmill test to assess cardiorespiratory fitness ( Rowland, 1993 ). This data was not used in the present study, but was collated for another investigation assessing children's health and fitness status. Using the resting and maximum HR values, HR reserve (HRR, i.e. the difference between resting and maximum HR) at the 50% threshold was calculated for each student. HRR accounts for age and gender HR differences, and is recommended when using HR to assess physical activity in children ( Stratton, 1996a ). The 50% HRR threshold represents moderate intensity physical activity ( Stratton, 1996a ), which is the minimal intensity required to contribute to the recommended volume of health-related activity ( Biddle et al. , 1998 ). Percentage of lesson time spent in health enhancing moderate-and-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) was calculated for each student by summing the time spent ≥50% HRR threshold. HRR values ≥75% corresponded to vigorous intensity physical activity (VPA). This threshold represents the intensity that may stimulate improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness ( Morrow and Freedson, 1994 ) and was used to indicate the proportion of lesson time that students were active at this higher level.

Sixty-six lessons were monitored over a 12-week period, covering a variety of group and individual activities ( Table I ). In order to allow statistically meaningful comparisons between different types of activities, students were classified as participants in activities that shared similar characteristics. These were, team games [i.e. invasion (e.g. football and hockey) and striking games (e.g. cricket and softball)], individual games (e.g. badminton, tennis and table tennis), movement activities (e.g. dance and gymnastics) and individual activities [e.g. athletics, fitness (circuit training and running activities) and swimming]. The intention was to monitor equal numbers of students during lessons in each of the four designated PE activity categories. However, timetable constraints and student absence meant that true equity was not possible, and so the number of boys and girls monitored in the different activities was unequal.

Number and type of monitored PE lessons

| . | . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boy | Girls | All students | |||

| Team games | 15 | 7 | 22 | ||

| Movement activities | 3 | 13 | 16 | ||

| Individual activities | 7 | 10 | 17 | ||

| Individual games | 7 | 4 | 11 | ||

| Total | 32 | 34 | 66 | ||

| . | . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boy | Girls | All students | |||

| Team games | 15 | 7 | 22 | ||

| Movement activities | 3 | 13 | 16 | ||

| Individual activities | 7 | 10 | 17 | ||

| Individual games | 7 | 4 | 11 | ||

| Total | 32 | 34 | 66 | ||

Student sex, ability level and PE activity category were the independent variables, with percent of lesson time spent in MVPA and VPA set as the dependent variables. Exploratory analyses were conducted to establish whether data met parametric assumptions. Shapiro–Wilk tests revealed that only boys' MVPA were normally distributed. Subsequent Levene's tests confirmed the data's homogeneity of variance, with the exception of VPA between the PE activities. Though much of the data violated the assumption of normality, the ANOVA is considered to be robust enough to produce valid results in this situation ( Vincent, 1999 ). Considering this, alongside the fact that the data had homogenous variability, it was decided to proceed with ANOVA for all analyses, with the exception of VPA between different PE activities.

Sex × ability level factorial ANOVAs compared the physical activity of boys and girls who differed in PE competence. A one-way ANOVA was used to identify differences in MVPA during the PE activities. Post-hoc analyses were performed using Hochberg's GT2 correction procedure, which is recommended when sample sizes are unequal ( Field, 2000 ). A non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA calculated differences in VPA during the different activities. Post-hoc Mann–Whitney U -tests determined where identified differences occurred. To control for type 1 error the Bonferroni correction procedure was applied to these tests, which resulted in an acceptable α level of 0.008. Although these data were ranked for the purposes of the statistical analysis, they were presented as means ± SD to allow comparison with the other results. All data were analyzed using SPSS version 11.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

The average duration of PE lessons was 50.6 ± 20.8 min, although girls' (52.6 ± 25.4 min) lessons generally lasted longer than boys' (48.7 ± 15.1 min). When all PE activities were considered together, students engaged in MVPA and VPA for 34.3 ± 21.8 and 8.3 ± 11.1% of PE time, respectively. This equated to 17.5 ± 12.9 (MVPA) and 3.9 ± 5.3 (VPA) min. The high-ability students were more active than the average- and low-ability students, who took part in similar amounts of activity. These trends were apparent in boys and girls ( Table II ).

Mean (±SD) MVPA and VPA of boys and girls of differing abilities

| Boys | high | 22 | 49.9 ± 19.8 | 13.2 ± 13.5 |

| average | 21 | 35.7 ± 17.7 | 7.4 ± 9.3 | |

| low | 19 | 39.3 ± 20.0 | 10.1 ± 10.5 | |

| combined abilities | 62 | 39.4 ± 19.1 | 10.3 ± 11.4 | |

| Girls | high | 22 | 33.7 ± 22.9 | 8.8 ± 12.4 |

| average | 18 | 25.5 ± 23.2 | 3.3 ± 7.5 | |

| low | 20 | 27.3 ± 24.5 | 5.9 ± 10.0 | |

| combined abilities | 60 | 29.1 ± 23.4 | 6.2 ± 10.4 | |

| Boys and girls | high | 44 | 38.3 ± 21.7 | 11.1 ± 13.0 |

| average | 39 | 31.0 ± 20.8 | 5.5 ± 8.7 | |

| low | 39 | 33.1 ± 22.9 | 8.0 ± 10.3 | |

| combined abilities | 122 | 34.3 ± 21.8 | 8.3 ± 11.1 |

| Boys | high | 22 | 49.9 ± 19.8 | 13.2 ± 13.5 |

| average | 21 | 35.7 ± 17.7 | 7.4 ± 9.3 | |

| low | 19 | 39.3 ± 20.0 | 10.1 ± 10.5 | |

| combined abilities | 62 | 39.4 ± 19.1 | 10.3 ± 11.4 | |

| Girls | high | 22 | 33.7 ± 22.9 | 8.8 ± 12.4 |

| average | 18 | 25.5 ± 23.2 | 3.3 ± 7.5 | |

| low | 20 | 27.3 ± 24.5 | 5.9 ± 10.0 | |

| combined abilities | 60 | 29.1 ± 23.4 | 6.2 ± 10.4 | |

| Boys and girls | high | 44 | 38.3 ± 21.7 | 11.1 ± 13.0 |

| average | 39 | 31.0 ± 20.8 | 5.5 ± 8.7 | |

| low | 39 | 33.1 ± 22.9 | 8.0 ± 10.3 | |

| combined abilities | 122 | 34.3 ± 21.8 | 8.3 ± 11.1 |

Boys > girls, P < 0.01.

Boys > girls, P < 0.05.

Boys engaged in MVPA for 39.4% ± 19.1 of lesson time compared to the girls' value of 29.1 ± 23.4 [ F (1, 122) = 7.2, P < 0.01]. When expressed as absolute units of time, these data were the equivalent of 18.9 ± 10.5 (boys) and 16.1 ± 14.9 (girls) min. Furthermore, a 4% difference in VPA was observed between the two sexes [ Table II ; F (1, 122) = 4.6, P < 0.05]. There were no significant sex × ability interactions for either MVPA or VPA.

Students participated in most MVPA during team games [43.2 ± 19.5%; F (3, 121) = 6.0, P < 0.01]. Individual games and individual activities provided a similar stimulus for activity, while the least MVPA was observed during movement activities (22.2 ± 20.0%; Figure 1 ). A smaller proportion of PE time was spent in VPA during all activities. Once more, team games (13.6 ± 11.3%) and individual activities (11.8 ± 14.0%) were best suited to promoting this higher intensity activity (χ 2 (3) =30.0, P < 0.01). Students produced small amounts of VPA during individual and movement activities, although this varied considerably in the latter activity ( Figure 2 ).

Mean (±SD) MVPA during different PE activities. ** Team games > movement activities ( P < 0.01). * Individual activities > movement activities ( P < 0.05).

Mean (±SD) VPA during different PE activities. ** Team games > movement activities ( Z (3) = −4.9, P < 0.008) and individual games ( Z (3) = −3.8, P < 0.008). † Individual activities > movement activities ( Z (3) = −3.3, P < 0.008). ‡ Individual game > movement activities ( Z (3) = −2.7, P < 0.008).

This study used HR telemetry to assess physical activity levels during a range of high school PE lessons. The data were considered in relation to recommended levels of physical activity ( Biddle et al. , 1998 ) to investigate whether or not PE can be effective in helping children be ‘fit and healthy’. Levels of MVPA were similar to those reported in previous studies ( Klausen et al. , 1986 ; Strand and Reeder, 1993 ; Fairclough, 2003b ) and did not meet the US Department of Health and Human Services ( US Department of Health and Human Services, 2000 ) 50% of lesson time criterion. Furthermore, the data were subject to considerable variance, which was exemplified by high standard deviation values ( Table II , and Figures 1 and 2 ). Such variation in activity levels reflects the influence of PE-specific contextual and pedagogical factors [i.e. lesson objectives, content, environment, teaching styles, etc. ( Stratton, 1996a )]. The superior physical activity levels of the high-ability students concurred with previous findings ( Li and Dunham, 1993 ; Stratton, 1996b ). However, the low-ability students engaged in more MVPA and VPA than the average-ability group. While it is possible that the teachers may have inaccurately assessed the low and average students' competence, it could have been that the low-ability group displayed more effort, either because they were being monitored or because they associated effort with perceived ability ( Lintunen, 1999 ). However, these suggestions are speculative and are not supported by the data. The differences in activity levels between the ability groups lend some support to the criticism that PE teachers sometimes teach the class as one and the same rather than planning for individual differences ( Metzler, 1989 ). If this were the case then undifferentiated activities may have been beyond the capability of the lesser skilled students. This highlights the importance of motor competence as an enabling factor for physical activity participation. If a student is unable to perform the requisite motor skills to competently engage in a given task or activity, then their opportunities for meaningful participation become compromised ( Rink, 1994 ). Over time this has serious consequences for the likelihood of a young person being able or motivated enough to get involved in physical activity which is dependent on a degree of fundamental motor competence.

Boys spent a greater proportion of lesson time involved in MVPA and VPA than girls. These differences are supported by other HR studies in PE ( Mota, 1994 ; Stratton, 1997 ). Boys' activity levels equated to 18.9 min of MVPA, compared to 16.1 min for the girls. It is possible that the characteristics and aims of some of the PE activities that the girls took part in did not predispose them to engage in whole body movement as much as the boys. Specifically, the girls participated in 10 more movement lessons and eight less team games lessons than the boys. The natures of these two activities are diverse, with whole body movement at differing speeds being the emphasis during team games, compared to aesthetic awareness and control during movement activities. The monitored lessons reflected typical boys' and girls' PE curricula, and the fact that girls do more dance and gymnastics than boys inevitably restricts their MVPA engagement. Although unrecorded contextual factors may have contributed to this difference, it is also possible that the girls were less motivated than the boys to physically exert themselves. This view is supported by negative correlations reported between girls' PE enjoyment and MVPA ( Fairclough, 2003b ). Moreover, there is evidence ( Dickenson and Sparkes, 1988 ; Goudas and Biddle, 1993 ) to suggest that some pupils, and girls in particular ( Cockburn, 2001 ), may dislike overly exerting themselves during PE. Although physical activity is what makes PE unique from other school subjects, some girls may not see it as such an integral part of their PE experience. It is important that this perception is clearly recognized if lessons are to be seen as enjoyable and relevant, whilst at the same time contributing meaningfully to physical activity levels. Girls tend to be habitually less active than boys and their levels of activity participation start to decline at an earlier age ( Armstrong and Welsman, 1997 ). Therefore, the importance of PE for girls as a means of them experiencing regular health-enhancing physical activity cannot be understated.

Team games promoted the highest levels of MVPA and VPA. This concurs with data from previous investigations ( Strand and Reeder, 1993 ; Stratton, 1996a , 1997 ; Fairclough, 2003a ). Because these activities require the use of a significant proportion of muscle mass, the heart must maintain the oxygen demand by beating faster and increasing stroke volume. Moreover, as team games account for the majority of PE curriculum time ( Fairclough and Stratton, 1997 ; Sport England, 2001 ), teachers may actually be more experienced and skilled at delivering quality lessons with minimal stationary waiting and instruction time. Similarly high levels of activity were observed during individual activities. With the exception of throwing and jumping themes during athletics lessons, the other individual activities (i.e. swimming, running, circuit/station work) involved simultaneous movement of the arms and legs over variable durations. MVPA and VPA were lowest during movement activities, which mirrored previous research involving dance and gymnastics ( Stratton, 1997 ; Fairclough, 2003a ). Furthermore, individual games provided less opportunity for activity than team games. The characteristics of movement activities and individual games respectively emphasize aesthetic appreciation and motor skill development. This can mean that opportunities to promote cardiorespiratory health may be less than in other activities. However, dance and gymnastics can develop flexibility, and muscular strength and endurance. Thus, these activities may be valuable to assist young people in meeting the HDA's secondary physical activity recommendation, which relates to musculo-skeletal health ( Biddle et al. , 1998 ).

The question of whether PE can solely contribute to young people's cardiorespiratory fitness was clearly answered. The students engaged in small amounts of VPA (4.5 and 3.3 min per lesson for boys and girls, respectively). Combined with the limited frequency of curricular PE, these were insufficient durations for gains in cardiorespiratory fitness to occur ( Armstrong and Welsman, 1997 ). Teachers who aim to increase students' cardiorespiratory fitness may deliver lessons focused exclusively on high intensity exercise, which can effectively increase HR ( Baquet et al. , 2002 ), but can sometimes be mundane and have questionable educational value. Such lessons may undermine other efforts to promote physical activity participation if they are not delivered within an enjoyable, educational and developmental context. It is clear that high intensity activity is not appropriate for all pupils, and so opportunities should be provided for them to be able to work at developmentally appropriate levels.

Students engaged in MVPA for around 18 min during the monitored PE lessons. This approximates a third of the recommended daily hour ( Biddle et al. , 1998 ). When PE activity is combined with other forms of physical activity support is lent to the premise that PE lessons can directly benefit young people's health status. Furthermore, for the very least active children who should initially aim to achieve 30 min of activity per day ( Biddle et al. , 1998 ), PE can provide the majority of this volume. However, a major limitation to PE's utility as a vehicle for physical activity participation is the limited time allocated to it. The government's aspiration is for all students to receive 2 hours of PE per week ( Department for Education and Employment/Qualifications and Curriculum Authority, 1999 ), through curricular and extra-curricular activities. While some schools provide this volume of weekly PE, others are unable to achieve it ( Sport England, 2001 ). The HDA recommend that young people strive to achieve 1 hour's physical activity each day through many forms, a prominent one of which is PE. The apparent disparity between recommended physical activity levels and limited curriculum PE time serves to highlight the complementary role that education, along with other agencies and voluntary organizations must play in providing young people with physical activity opportunities. Notwithstanding this, increasing the amount of PE curriculum time in schools would be a positive step in enabling the subject to meet its health-related goals. Furthermore, increased PE at the expense of time in more ‘academic’ subjects has been shown not to negatively affect academic performance ( Shephard, 1997 ; Sallis et al. , 1999 ; Dwyer et al. , 2001 ).

Physical educators are key personnel to help young people achieve physical activity goals. As well as their teaching role they are well placed to encourage out of school physical activity, help students become independent participants and inform them about initiatives in the community ( McKenzie et al. , 2000 ). Also, they can have a direct impact by promoting increased opportunities for physical activity within the school context. These could include activities before school ( Strand et al. , 1994 ), during recess ( Scruggs et al. , 2003 ), as well as more organized extra-curricular activities at lunchtime and after school. Using time in this way would complement PE's role by providing physical activity opportunities in a less structured and pedagogically constrained manner.

This research measured student activity levels during ‘typical’, non-intensified PE lessons. In this sense it provided a representative picture of the frequency, intensity and duration of students' physical activity engagement during curricular PE. However, some factors should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, the data were cross-sectional and collected over a relatively short time frame. Tracking students' activity levels over a number of PE activities may have allowed a more accurate account of how physical activity varies in different aspects of the curriculum. Second, monitoring a larger sample of students over more lessons may have enabled PE activities to be categorized into more homogenous groups. Third, monitoring lessons in schools from a wider geographical area may have enabled stronger generalization of the results. Fourth, it is possible that the PE lessons were taught differently, and that the students acted differently as a result of being monitored and having the researchers present during lessons. As this is impossible to determine, it is unknown how this might have affected the results. Fifth, HR telemetry does not provide any contextual information about the monitored lessons. Also, HR is subject to emotional and environmental factors when no physical activity is occurring. Future work should combine objective physical activity measurement with qualitative or quantitative methods of observation.

During PE, students took part in health-enhancing activity for around one third of the recommended 1-hour target ( Biddle et al. , 1998 ). PE obviously has potential to help meet this goal. However, on the basis of these data, combined with the weekly frequency of PE lessons, it is clear that PE can only do so much in supplementing young people's daily volume of physical activity. Students need to be taught appropriate skills, knowledge and understanding if they are to optimize their physical activity opportunities in PE. For improved MVPA levels to occur, health-enhancing activity needs to be recognized as an important element of lessons. PE may make a more significant contribution to young people's regular physical activity participation if lessons are planned and delivered with MVPA goals in mind.

Armstrong, N. and Welsman, J.R. ( 1997 ) Young People and Physical Activity , Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Baquet, G., Berthoin, S. and Van Praagh, E. ( 2002 ) Are intensified physical education sessions able to elicit heart rate at a sufficient level to promote aerobic fitness in adolescents? Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport , 73 , 282 –288.

Biddle, S., Sallis, J.F. and Cavill, N. (eds) ( 1998 ) Young and Active? Young People and Health-Enhancing Physical Activity—Evidence and Implications. Health Education Authority, London.

Borys, A.H. ( 1983 ) Increasing pupil motor engagement time: case studies of student teachers. In Telema, R. (ed.), International Symposium on Research in School Physical Education. Foundation for Promotion of Physical Culture and Health, Jyvaskyla, pp. 351–358.

Brooke, J., Hardman, A. and Bottomly, F. ( 1975 ) The physiological load of a netball lesson. Bulletin of Physical Education , 11 , 37 –42.

Cockburn, C. ( 2001 ) Year 9 girls and physical education: a survey of pupil perceptions. Bulletin of Physical Education , 37 , 5 –24.

Corbin, C.B. and Pangrazi, R.P. ( 1998 ) Physical Activity for Children: A Statement of Guidelines. NASPE Publications, Reston, VA.

Department for Education and Employment/Qualifications and Curriculum Authority ( 1999 ) Physical Education—The National Curriculum for England. DFEE/QCA, London.

Dickenson, B. and Sparkes, A. ( 1988 ) Pupil definitions of physical education. British Journal of Physical Education Research Supplement , 2 , 6 –7.

Dwyer, T., Sallis, J.F., Blizzard, L., Lazarus, R. and Dean, K. ( 2001 ) Relation of academic performance to physical activity and fitness in children. Pediatric Exercise Science , 13 , 225 –237.

Fairclough, S. ( 2003 a) Physical activity levels during key stage 3 physical education. British Journal of Teaching Physical Education , 34 , 40 –45.

Fairclough, S. ( 2003 b) Physical activity, perceived competence and enjoyment during high school physical education. European Journal of Physical Education , 8 , 5 –18.

Fairclough, S. ( 2003 c) Girls' physical activity during high school physical education: influences of body composition and cardiorespiratory fitness. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education , 22 , 382 –395.

Fairclough, S. and Stratton, G. ( 1997 ) Physical education curriculum and extra-curriculum time: a survey of secondary schools in the north-west of England. British Journal of Physical Education , 28 , 21 –24.

Fairclough, S., Stratton, G. and Baldwin, G. ( 2002 ) The contribution of secondary school physical education to lifetime physical activity. European Physical Education Review , 8 , 69 –84.

Field, A. ( 2000 ) Discovering Statistics using SPSS for Windows. Sage, London.

Freedson, P.S. and Miller, K. ( 2000 ) Objective monitoring of physical activity using motion sensors and heart rate. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport , 71 (Suppl.), S21 –S29.

Goudas, M. and Biddle, S. ( 1993 ) Pupil perceptions of enjoyment in physical education. Physical Education Review , 16 , 145 –150.

Gutin, B., Islam, S., Manos, T., Cucuzzo, N., Smith, C. and Stachura, M.E. ( 1994 ) Relation of body fat and maximal aerobic capacity to risk factors for atherosclerosis and diabetes in black and white seven-to-eleven year old children. Journal of Pediatrics , 125 , 847 –852.

International Council of Sport Science and Physical Education ( 1999 ) Results and Recommendations of the World Summit on Physical Education , Berlin, November.

Klausen, K., Rasmussen, B. and Schibye, B. ( 1986 ) Evaluation of the physical activity of school children during a physical education lesson. In Rutenfranz, J., Mocellin, R. and Klint, F. (eds), Children and Exercise XII. Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL, pp. 93–102.

Koslow, R. ( 1988 ) Can physical fitness be a primary objective in a balanced PE program? Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance , 59 , 75 –77.

Levin, S., McKenzie, T.L., Hussey, J., Kelder, S.H. and Lytle, L. ( 2001 ) Variability of physical activity during physical education lesson across school grades. Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise Science , 5 , 207 –218.

Li, X. and Dunham, P. ( 1993 ) Fitness load and exercise time in secondary physical education classes. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education , 12 , 180 –187.

Lintunen, T. ( 1999 ) Development of self-perceptions during the school years. In Vanden Auweele, Y., Bakker, F., Biddle, S., Durand, M. and Seiler, R. (eds), Psychology for Physical Educators. Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL, pp. 115–134.

Malina, R.M. and Bouchard, C. ( 1991 ) Growth , Maturation and Physical Activity . Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL.

McKenzie, T.L., Marshall, S.J., Sallis, J.F. and Conway, T.L. ( 2000 ). Student activity levels, lesson context and teacher behavior during middle school physical education. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport , 71 , 249 –259.

Metzler, M.W. ( 1989 ) A review of research on time in sport pedagogy. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education , 8 , 87 –103.

Michaud, T.J. and Andres, F.F. ( 1990 ) Should physical education programs be responsible for making our youth fit? Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance , 61 , 32 –35.

Morrow, J. and Freedson, P. ( 1994 ) Relationship between habitual physical activity and aerobic fitness in adolescents. Pediatric Exercise Science , 6 , 315 –329.

Mota, J. ( 1994 ) Children's physical education activity, assessed by telemetry. Journal of Human Movement Studies , 27 , 245 –250.

Physical Education Association of the United Kingdom ( 2004 ) PEA UK Policy on the Physical Education Curriculum . Available: http://www.pea.uk.com/menu.html ; retrieved: 28 April, 2004.

Rink, J.E. ( 1994 ) Fitting fitness into the school curriculum. In Pate, R.R. and Hohn, R.C. (eds), Health and Fitness Through Physical Education. Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL, pp. 67–74.

Rowland, T.W. ( 1993 ) Pediatric Laboratory Exercise Testing . Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL.

Sallis, J.F., McKenzie, R.D., Kolody, B., Lewis, S., Marshall, S.J. and Rosengard, P. ( 1999 ) Effects of health-related physical education on academic achievement: Project SPARK. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport , 70 , 127 –134.

Sallis, J.F. and McKenzie, T.L. ( 1991 ) Physical education's role in public health. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport , 62 , 124 –137.

Scruggs, P.W., Beveridge, S.K. and Watson, D.L. ( 2003 ) Increasing children's school time physical activity using structured fitness breaks. Pediatric Exercise Science , 15 , 156 –169.

Seliger, V., Heller, J., Zelenka, V., Sobolova, V., Pauer, M., Bartunek, Z. and Bartunkova, S. ( 1980 ) Functional demands of physical education lessons. In Berg, K. and Eriksson, B.O. (eds), Children and Exercise IX . University Park Press, Baltimore, MD, vol. 10, pp. 175–182.

Shephard, R.J. ( 1997 ) Curricular physical activity and academic performance. Pediatric Exercise Science , 9 , 113 –126.

Simons-Morton, B.G. ( 1994 ) Implementing health-related physical education. In Pate, R.R. and Hohn, R.C. (eds), Health and Fitness Through Physical Education. Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL, pp. 137–146.

Sport England ( 2001 ) Young People and Sport in England 1999 . Sport England, London.

Strand, B. and Reeder, S. ( 1993 ) Analysis of heart rate levels during middle school physical education activities. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance , 64 , 85 –91.

Strand, B., Quinn, P.B., Reeder, S. and Henke, R. ( 1994 ) Early bird specials and ten minute tickers. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance , 65 , 6 –9.

Stratton, G. ( 1996 a) Children's heart rates during physical education lessons: a review. Pediatric Exercise Science , 8 , 215 –233.

Stratton, G. ( 1996 b) Physical activity levels of 12–13 year old schoolchildren during European handball lessons: gender and ability group differences. European Physical Education Review , 2 , 165 –173.

Stratton, G. ( 1997 ) Children's heart rates during British physical education lessons, Journal of Teaching in Physical Education . 16 , 357 –367.

US Department of Health and Human Services ( 2000 ) Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health . USDHHS, Washington DC.

Vincent, W. ( 1999 ) Statistics in Kinesiology , Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL.

Zeigler, E. ( 1994 ) Physical education's 13 principal principles. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance , 65 , 4 –5.

Author notes

1REACH Group and School of Physical Education, Sport and Dance, Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool L17 6BD and 2REACH Group and Research Institute for Sport and Exercise Sciences, Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool L3 2ET, UK

- physical activity

- valproic acid

- physical education

- high schools

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| November 2016 | 18 |

| December 2016 | 12 |

| January 2017 | 46 |

| February 2017 | 92 |

| March 2017 | 194 |

| April 2017 | 211 |

| May 2017 | 124 |

| June 2017 | 38 |

| July 2017 | 16 |

| August 2017 | 37 |

| September 2017 | 65 |

| October 2017 | 92 |

| November 2017 | 285 |

| December 2017 | 1,232 |

| January 2018 | 1,427 |

| February 2018 | 1,549 |

| March 2018 | 2,837 |

| April 2018 | 3,171 |

| May 2018 | 2,891 |

| June 2018 | 3,020 |

| July 2018 | 2,591 |

| August 2018 | 3,755 |

| September 2018 | 3,961 |

| October 2018 | 4,994 |

| November 2018 | 5,041 |

| December 2018 | 3,786 |

| January 2019 | 3,765 |

| February 2019 | 4,230 |

| March 2019 | 5,588 |

| April 2019 | 4,246 |

| May 2019 | 3,470 |

| June 2019 | 2,518 |

| July 2019 | 2,700 |

| August 2019 | 3,020 |

| September 2019 | 3,565 |

| October 2019 | 3,483 |

| November 2019 | 2,750 |

| December 2019 | 2,692 |

| January 2020 | 2,467 |

| February 2020 | 2,420 |

| March 2020 | 2,333 |

| April 2020 | 3,639 |

| May 2020 | 2,344 |

| June 2020 | 3,022 |

| July 2020 | 3,053 |

| August 2020 | 5,885 |

| September 2020 | 17,141 |

| October 2020 | 15,251 |

| November 2020 | 8,298 |

| December 2020 | 7,514 |

| January 2021 | 6,852 |

| February 2021 | 7,743 |

| March 2021 | 8,396 |

| April 2021 | 7,995 |

| May 2021 | 6,803 |

| June 2021 | 3,891 |

| July 2021 | 3,058 |

| August 2021 | 5,618 |

| September 2021 | 10,811 |

| October 2021 | 9,479 |

| November 2021 | 6,897 |

| December 2021 | 5,532 |

| January 2022 | 5,347 |

| February 2022 | 5,902 |

| March 2022 | 6,363 |

| April 2022 | 5,326 |

| May 2022 | 4,311 |

| June 2022 | 2,604 |

| July 2022 | 1,704 |

| August 2022 | 3,818 |

| September 2022 | 6,345 |

| October 2022 | 3,390 |

| November 2022 | 2,435 |

| December 2022 | 1,893 |

| January 2023 | 1,775 |

| February 2023 | 1,591 |

| March 2023 | 1,882 |

| April 2023 | 1,248 |

| May 2023 | 1,165 |

| June 2023 | 692 |

| July 2023 | 538 |

| August 2023 | 970 |

| September 2023 | 1,948 |

| October 2023 | 1,052 |

| November 2023 | 1,013 |

| December 2023 | 964 |

| January 2024 | 1,146 |

| February 2024 | 1,024 |

| March 2024 | 992 |

| April 2024 | 888 |

| May 2024 | 820 |

| June 2024 | 356 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1465-3648

- Print ISSN 0268-1153

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

New Research Examines Physical Education in America

By Morgan Clennin, PhD, MPH, Kaiser Permanente of Colorado, University of South Carolina, and National Physical Activity Plan

School-based physical education (PE) is recommended by the Community Guide as an effective strategy to promote physical activity among youth. Unfortunately, many have speculated that PE exposure has declined precipitously among U.S. students in the past decade. Limited resources and budgets, prioritization of core academic subjects, and several other barriers have been cited as potential drivers of these claims. However, few large-scale studies have explored the merit of these claims – leaving the answers following questions unknown:

Has PE attendance decreased among U.S. students in the past decades?

What policies and practices are in place to support quality PE?

To answer these questions, the President’s Council on Sports, Fitness & Nutrition tasked the National Physical Activity Plan Alliance (NPAPA) to review the available evidence and summarize their findings. The primary objective of this effort was to better understand PE exposure over time to inform national recommendations and strategies for PE.

The NPAPA began by establishing a collaborative partnership with experts in the federal government, industry, and academia. The group analyzed existing national data sources that could be used to examine changes in PE attendance and current implementation of PE policies and practices. These efforts culminated in a final report and two peer-reviewed manuscripts. A summary of the group’s findings are outlined below.

Key Findings:

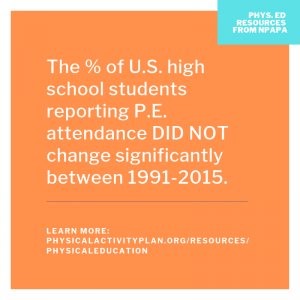

- 1/2 of U.S. high school students did not attend PE classes—which is consistent over the 24-year period studied (1991-2015).

- The percentage of U.S. high school students reporting PE attendance did not change significantly between 1991 and 2015 for the overall sample or across sex and race/ethnicity subgroup.

- Daily PE attendance did decrease 16% from 1991 to 1995 then attendance rates remained stable through 2015.

- > 65% of schools implemented 2-4 of the 7 essential PE policies

- Implementation of PE policies varied by region, metropolitan status, and school level.

- Data indicates minority students have been disproportionately affected by cuts to school PE programs during the past two decades.

Recommendations Based on Key Findings:

- Prioritize efforts to expand collection of surveillance data examining trends in PE attendance among elementary and middle school students.

- Develop policies to improve PE access for all students in order for PE to contribute to increased physical activity among youth.

- Adopt policies and programs that prioritize PE to maximize the benefits of PE.

- Utilize the findings of these efforts to target professional development and technical assistance for PE practitioners.

The Education sector of the NPAP provides evidence-based strategies and tactics that can guide efforts to support the provision of quality PE to all students. More information, and links to the respective manuscripts, can be found on the NPAPA website: http://physicalactivityplan.org/projects/physicaleducation.html

The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by ODPHP or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

Popular Searches

- Financial Aid

- Tuition and Fees

- Academic Calendar

- Campus Tours

- News Article

The Benefits of Physical Education: How Innovative Teachers Help Students Thrive

January 16, 2020 | Written By Heather Nelson

For students in elementary, middle, or high school, the long-term benefits of physical education classes are not always evident—but strong teachers with innovative ideas are changing that. These educators find creative and evidence-based ways to help students tune into their bodies, minds, and attitudes.

Here’s a look at the benefits of physical education programs, how educators design their lessons to bring out the best in their students, and what the future may bring to this space.

Advantages of Physical Education

The benefits associated with physical education programming go far beyond accomplishments made in the gym. When students have the opportunity to step away from their desks and move their bodies in a physical education class, they gain the benefits of mental health support, stress relief, heart health, and more.

The Institute of Medicine reported that physically active students are more focused, better retain information, and problem-solve more successfully than their less active peers. While the benefits of physical education are clear, ensuring students get the most from P.E. comes down to innovative and well-trained educators.

Innovation in Physical Education for Today’s Classroom

When most people think of physical education, they think of running laps and climbing a rope in the middle of the school gym. However, the most effective physical education teachers know there’s much more to P.E. than jogging and climbing.

Andrew Alstot, PhD, associate professor in the Department of Kinesiology at Azusa Pacific University, explained that “good physical educators create comprehensive educational programs that go beyond simply getting kids physically active.” He said he encourages teachers to expose students to various physical activities, which helps them find activities they love.

The goal is to help students grow and to provide positive feedback and guidance so that they become comfortable participating in physical activity outside of school. One way teachers do this is through tailored lessons, ensuring activities are accessible yet challenging for each student.

Greg Bellinder, MS, assistant professor at APU, teaches future physical educators to differentiate their instruction to meet the individual needs of all students— a method called Universal Design for Learning (UDL). He explained what this might look like in the classroom:

“Consider a warm-up jog at the beginning of a lesson. The classic approach required all students to jog a lap around the track. Depending on ability level, some students finished in about two minutes and waited much longer than that until the very last students finished. During this downtime, slower students were embarrassed, knowing the rest of the class was waiting for them. Taking a UDL approach, a physical educator would create a warm-up circle with a much smaller radius. Instead of requiring students to run the same distance, she or he would have them jog as many laps around the smaller circle in a set time, challenging each student to complete a number of laps that are personally challenging. At the end of four minutes, for instance, everyone stops jogging. The faster students have been challenged at their level while the slower students have been challenged at their level. No student has been stigmatized. The teacher now has additional instructional minutes for skill-based instruction.”

Innovative physical education means meeting students at their level, providing guidance to strengthen skills, and instilling a lifetime love of movement . As instructors look to the future, including these innovative lessons in their curriculum can pave the way for students to embrace physical education.

The Future of Physical Education

The future of physical education is not only physical! APU’s Janna Sanchez, MS, said educators have the unique responsibility to shift the focus from physical competition and winning to the discoveries that can be made through activity and play. By tapping into students’ capabilities and strengths, physical educators can do more than simply teach a sport, she said.

“Physical education programs should not be based on sports alone, but on positive movement opportunities that enhance self-esteem, worth, dignity, and self-discipline,” said Sanchez. “A child is able to capitalize on their own personal strengths and learn from their weaknesses when they comprehend how to work with others in a variety of settings. That is what physical education and play are all about.”

The best physical education programs provide space for students to develop their bodies and minds—and the future of P.E. is continuing further in that direction. With teachers committed to creating lesson plans that strengthen students from the inside out, the days of dreading gym class may be coming to an end.

Physical Education Schools

What is the impact of physical education on students’ well-being and academic success?

Decreasing time for quality phys-ed to allow more instructional time for core curricular subjects – including math, science, social studies and English – is counterproductive, given its positive benefits on health outcomes and school achievement.

by: Lee Schaefer , Derek Wasyliw

date: June 25, 2018

Download and print the Fact Sheet (232.30 kB / pdf)

Research confirms that healthier students make better learners. The term quality physical education is used to describe programs that are catered to a student’s age, skill level, culture and unique needs. They include 90 minutes of physical activity per week, fostering students’ well-being and improving their academic success. However, instructional time for quality phys-ed programs around the world are being decreased to prioritize other subject areas (especially math, science, social studies and English) in hopes to achieve higher academic achievement. However, several studies have identified a significant relationship between physical activity and academic achievement. Research also demonstrates that phys-ed does not have negative impacts on student success and that it offers the following physical, social, emotional and cognitive benefits:

Quality phys-ed helps students understand how exercise helps them to develop a healthy lifestyle, gain a variety of skills that help them to participate in a variety of physical activities and enjoy an active lifestyle.

Quality phys-ed provides students with the opportunity to socialize with others and learn different skills such as communication, tolerance, trust, empathy and respect for others. They also learn positive team skills including cooperation, leadership, cohesion and responsibility. Students who play sports or participate in other physical activities experience a variety of emotions and learn how to better cope in stressful, challenging or painful situations.

Quality phys-ed can be associated with improved mental health, since increased activity provides psychological benefits including reduced stress, anxiety and depression. It also helps students develop strategies to manage their emotions and increases their self-esteem.

Research tends to show that increased blood flow produced by physical activity may stimulate the brain and boost mental performance. Avoiding inactivity may also increase energy and concentration in the classroom.

Therefore, decreasing time for quality phys-ed to allow more instructional time for core curricular subjects – including math, science, social studies and English – is counterproductive, given its positive benefits on health outcomes and school achievement.

Additional Information Resources

PHE Canada (2018). Quality daily physical education . Retrieved from https://phecanada.ca/activate/qdpe

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2005). Healthy schools daily physical activity in schools grades 1 ‐ 3. Retrieved from http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/teachers/dpa1-3.pdf

Ardoy, D. N., Fernández‐Rodríguez, J. M., Jiménez‐Pavón, D., Castillo, R., Ruiz, J. R., & Ortega, F. B. (2014). A Physical Education trial improves adolescents’ cognitive performance and academic achievement: The EDUFIT study. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports , 24 (1).

Bailey, R., Armour, K., Kirk, D., Jess, M., Pickup, I., Sandford, R., & Education, B. P. (2009). The educational benefits claimed for physical education and school sport: An academic review. Research papers in education , 24 (1), 1-27.

Beane, J.A. (1990). Affect in the curriculum: Toward democracy, dignity, and diversity . Columbia: Teachers College Press.

Bedard, C., Bremer, E., Campbell, W., & Cairney, J. (2017). Evaluation of a direct-instruction intervention to improve movement and pre-literacy skills among young children: A within-subject repeated measures design. Frontiers in pediatrics , 5 , 298.

Hellison, D.R., N. Cutforth, J. Kallusky, T. Martinek, M. Parker, and J. Stiel. (2000). Youth development and physical activity: Linking universities and communities. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Ho, F. K. W., Louie, L. H. T., Wong, W. H. S., Chan, K. L., Tiwari, A., Chow, C. B., & Cheung, Y. F. (2017). A sports-based youth development program, teen mental health, and physical fitness: An RCT. Pediatrics , e20171543.

Keeley, T. J., & Fox, K. R. (2009). The impact of physical activity and fitness on academic achievement and cognitive performance in children. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology , 2 (2), 198-214.

Kohl III, H. W., & Cook, H. D. (Eds.). (2013). Educating the student body: Taking physical activity and physical education to school . National Academies Press.

Rasberry, C. N., Lee, S. M., Robin, L., Laris, B. A., Russell, L. A., Coyle, K. K., & Nihiser, A. J. (2011). The association between school-based physical activity, including physical education, and academic performance: a systematic review of the literature. Preventive medicine , 52 , S10-S20.

Sallis, J. F., McKenzie, T. L., Kolody, B., Lewis, M., Marshall, S., & Rosengard, P. (1999). Effects of health-related physical education on academic achievement: Project SPARK. Research quarterly for exercise and sport , 70 (2), 127-134.

Strong WB, Malina RM, Blimkie CJ, Daniels SR, Dishman RK, Gutin B, Hergenroeder AC, Must A, Nixon PA, Pivarnik JM, Rowland T, Trost S, & Trudeau F (2005). Evidence based physical activity for school-age youth. Journal of Pediatrics . 146(6):732–737.

Trudeau, F., & Shephard, R. J. (2008). Physical education, school physical activity, school sports and academic performance. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity , 5 (1), 10.

Beane, J. A. (1990). Affect in the curriculum: Toward democracy, dignity, and diversity . Columbia University, New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Meet the Expert(s)

Lee schaefer.

Assistant Professor in the Kinesiology and Physical Education Department at McGill University

Lee Schaefer is an Assistant Professor in the Kinesiology and Physical Education Department at McGill University. His work is generally focused on teacher education and teacher knowle...

Derek Wasyliw

Master’s student in the Kinesiology and Physical Education Graduate Program at McGill University

Derek Wasyliw is a second-year Master’s student in the Kinesiology and Physical Education Graduate Program at McGill University. He is the proud recipient of the 2017-2018 SSHRC Jo...

IDEAS TO SUPPORT EDUCATORS : Subscribe to the EdCan e-Newsletter

Quality research, reports, and professional learning opportunities.

Language Preference Langue de correspondance English Français English Français

An official website of the United States government