An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

The Effect of COVID-19 on Education

Jacob hoofman.

a Wayne State University School of Medicine, 540 East Canfield, Detroit, MI 48201, USA

Elizabeth Secord

b Department of Pediatrics, Wayne Pediatrics, School of Medicine, Pediatrics Wayne State University, 400 Mack Avenue, Detroit, MI 48201, USA

COVID-19 has changed education for learners of all ages. Preliminary data project educational losses at many levels and verify the increased anxiety and depression associated with the changes, but there are not yet data on long-term outcomes. Guidance from oversight organizations regarding the safety and efficacy of new delivery modalities for education have been quickly forged. It is no surprise that the socioeconomic gaps and gaps for special learners have widened. The medical profession and other professions that teach by incrementally graduated internships are also severely affected and have had to make drastic changes.

- • Virtual learning has become a norm during COVID-19.

- • Children requiring special learning services, those living in poverty, and those speaking English as a second language have lost more from the pandemic educational changes.

- • For children with attention deficit disorder and no comorbidities, virtual learning has sometimes been advantageous.

- • Math learning scores are more likely to be affected than language arts scores by pandemic changes.

- • School meals, access to friends, and organized activities have also been lost with the closing of in-person school.

The transition to an online education during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic may bring about adverse educational changes and adverse health consequences for children and young adult learners in grade school, middle school, high school, college, and professional schools. The effects may differ by age, maturity, and socioeconomic class. At this time, we have few data on outcomes, but many oversight organizations have tried to establish guidelines, expressed concerns, and extrapolated from previous experiences.

General educational losses and disparities

Many researchers are examining how the new environment affects learners’ mental, physical, and social health to help compensate for any losses incurred by this pandemic and to better prepare for future pandemics. There is a paucity of data at this juncture, but some investigators have extrapolated from earlier school shutdowns owing to hurricanes and other natural disasters. 1

Inclement weather closures are estimated in some studies to lower middle school math grades by 0.013 to 0.039 standard deviations and natural disaster closures by up to 0.10 standard deviation decreases in overall achievement scores. 2 The data from inclement weather closures did show a more significant decrease for children dependent on school meals, but generally the data were not stratified by socioeconomic differences. 3 , 4 Math scores are impacted overall more negatively by school absences than English language scores for all school closures. 4 , 5

The Northwest Evaluation Association is a global nonprofit organization that provides research-based assessments and professional development for educators. A team of researchers at Stanford University evaluated Northwest Evaluation Association test scores for students in 17 states and the District of Columbia in the Fall of 2020 and estimated that the average student had lost one-third of a year to a full year's worth of learning in reading, and about three-quarters of a year to more than 1 year in math since schools closed in March 2020. 5

With school shifted from traditional attendance at a school building to attendance via the Internet, families have come under new stressors. It is increasingly clear that families depended on schools for much more than math and reading. Shelter, food, health care, and social well-being are all part of what children and adolescents, as well as their parents or guardians, depend on schools to provide. 5 , 6

Many families have been impacted negatively by the loss of wages, leading to food insecurity and housing insecurity; some of loss this is a consequence of the need for parents to be at home with young children who cannot attend in-person school. 6 There is evidence that this economic instability is leading to an increase in depression and anxiety. 7 In 1 survey, 34.71% of parents reported behavioral problems in their children that they attributed to the pandemic and virtual schooling. 8

Children have been infected with and affected by coronavirus. In the United States, 93,605 students tested positive for COVID-19, and it was reported that 42% were Hispanic/Latino, 32% were non-Hispanic White, and 17% were non-Hispanic Black, emphasizing a disproportionate effect for children of color. 9 COVID infection itself is not the only issue that affects children’s health during the pandemic. School-based health care and school-based meals are lost when school goes virtual and children of lower socioeconomic class are more severely affected by these losses. Although some districts were able to deliver school meals, school-based health care is a primary source of health care for many children and has left some chronic conditions unchecked during the pandemic. 10

Many families report that the stress of the pandemic has led to a poorer diet in children with an increase in the consumption of sweet and fried foods. 11 , 12 Shelter at home orders and online education have led to fewer exercise opportunities. Research carried out by Ammar and colleagues 12 found that daily sitting had increased from 5 to 8 hours a day and binge eating, snacking, and the number of meals were all significantly increased owing to lockdown conditions and stay-at-home initiatives. There is growing evidence in both animal and human models that diets high in sugar and fat can play a detrimental role in cognition and should be of increased concern in light of the pandemic. 13

The family stress elicited by the COVID-19 shutdown is a particular concern because of compiled evidence that adverse life experiences at an early age are associated with an increased likelihood of mental health issues as an adult. 14 There is early evidence that children ages 6 to 18 years of age experienced a significant increase in their expression of “clinginess, irritability, and fear” during the early pandemic school shutdowns. 15 These emotions associated with anxiety may have a negative impact on the family unit, which was already stressed owing to the pandemic.

Another major concern is the length of isolation many children have had to endure since the pandemic began and what effects it might have on their ability to socialize. The school, for many children, is the agent for forming their social connections as well as where early social development occurs. 16 Noting that academic performance is also declining the pandemic may be creating a snowball effect, setting back children without access to resources from which they may never recover, even into adulthood.

Predictions from data analysis of school absenteeism, summer breaks, and natural disaster occurrences are imperfect for the current situation, but all indications are that we should not expect all children and adolescents to be affected equally. 4 , 5 Although some children and adolescents will likely suffer no long-term consequences, COVID-19 is expected to widen the already existing educational gap from socioeconomic differences, and children with learning differences are expected to suffer more losses than neurotypical children. 4 , 5

Special education and the COVID-19 pandemic

Although COVID-19 has affected all levels of education reception and delivery, children with special needs have been more profoundly impacted. Children in the United States who have special needs have legal protection for appropriate education by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. 17 , 18 Collectively, this legislation is meant to allow for appropriate accommodations, services, modifications, and specialized academic instruction to ensure that “every child receives a free appropriate public education . . . in the least restrictive environment.” 17

Children with autism usually have applied behavioral analysis (ABA) as part of their individualized educational plan. ABA therapists for autism use a technique of discrete trial training that shapes and rewards incremental changes toward new behaviors. 19 Discrete trial training involves breaking behaviors into small steps and repetition of rewards for small advances in the steps toward those behaviors. It is an intensive one-on-one therapy that puts a child and therapist in close contact for many hours at a time, often 20 to 40 hours a week. This therapy works best when initiated at a young age in children with autism and is often initiated in the home. 19

Because ABA workers were considered essential workers from the early days of the pandemic, organizations providing this service had the responsibility and the freedom to develop safety protocols for delivery of this necessary service and did so in conjunction with certifying boards. 20

Early in the pandemic, there were interruptions in ABA followed by virtual visits, and finally by in-home therapy with COVID-19 isolation precautions. 21 Although the efficacy of virtual visits for ABA therapy would empirically seem to be inferior, there are few outcomes data available. The balance of safety versus efficacy quite early turned to in-home services with interruptions owing to illness and decreased therapist availability owing to the pandemic. 21 An overarching concern for children with autism is the possible loss of a window of opportunity to intervene early. Families of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder report increased stress compared with families of children with other disabilities before the pandemic, and during the pandemic this burden has increased with the added responsibility of monitoring in-home schooling. 20

Early data on virtual schooling children with attention deficit disorder (ADD) and attention deficit with hyperactivity (ADHD) shows that adolescents with ADD/ADHD found the switch to virtual learning more anxiety producing and more challenging than their peers. 22 However, according to a study in Ireland, younger children with ADD/ADHD and no other neurologic or psychiatric diagnoses who were stable on medication tended to report less anxiety with at-home schooling and their parents and caregivers reported improved behavior during the pandemic. 23 An unexpected benefit of shelter in home versus shelter in place may be to identify these stressors in face-to-face school for children with ADD/ADHD. If children with ADD/ADHD had an additional diagnosis of autism or depression, they reported increased anxiety with the school shutdown. 23 , 24

Much of the available literature is anticipatory guidance for in-home schooling of children with disabilities rather than data about schooling during the pandemic. The American Academy of Pediatrics published guidance advising that, because 70% of students with ADHD have other conditions, such as learning differences, oppositional defiant disorder, or depression, they may have very different responses to in home schooling which are a result of the non-ADHD diagnosis, for example, refusal to attempt work for children with oppositional defiant disorder, severe anxiety for those with depression and or anxiety disorders, and anxiety and perseveration for children with autism. 25 Children and families already stressed with learning differences have had substantial challenges during the COVID-19 school closures.

High school, depression, and COVID-19

High schoolers have lost a great deal during this pandemic. What should have been a time of establishing more independence has been hampered by shelter-in-place recommendations. Graduations, proms, athletic events, college visits, and many other social and educational events have been altered or lost and cannot be recaptured.

Adolescents reported higher rates of depression and anxiety associated with the pandemic, and in 1 study 14.4% of teenagers report post-traumatic stress disorder, whereas 40.4% report having depression and anxiety. 26 In another survey adolescent boys reported a significant decrease in life satisfaction from 92% before COVID to 72% during lockdown conditions. For adolescent girls, the decrease in life satisfaction was from 81% before COVID to 62% during the pandemic, with the oldest teenage girls reporting the lowest life satisfaction values during COVID-19 restrictions. 27 During the school shutdown for COVID-19, 21% of boys and 27% of girls reported an increase in family arguments. 26 Combine all of these reports with decreasing access to mental health services owing to pandemic restrictions and it becomes a complicated matter for parents to address their children's mental health needs as well as their educational needs. 28

A study conducted in Norway measured aspects of socialization and mood changes in adolescents during the pandemic. The opportunity for prosocial action was rated on a scale of 1 (not at all) to 6 (very much) based on how well certain phrases applied to them, for example, “I comforted a friend yesterday,” “Yesterday I did my best to care for a friend,” and “Yesterday I sent a message to a friend.” They also ranked mood by rating items on a scale of 1 (not at all) to 5 (very well) as items reflected their mood. 29 They found that adolescents showed an overall decrease in empathic concern and opportunity for prosocial actions, as well as a decrease in mood ratings during the pandemic. 29

A survey of 24,155 residents of Michigan projected an escalation of suicide risk for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender youth as well as those youth questioning their sexual orientation (LGBTQ) associated with increased social isolation. There was also a 66% increase in domestic violence for LGBTQ youth during shelter in place. 30 LGBTQ youth are yet another example of those already at increased risk having disproportionate effects of the pandemic.

Increased social media use during COVID-19, along with traditional forms of education moving to digital platforms, has led to the majority of adolescents spending significantly more time in front of screens. Excessive screen time is well-known to be associated with poor sleep, sedentary habits, mental health problems, and physical health issues. 31 With decreased access to physical activity, especially in crowded inner-city areas, and increased dependence on screen time for schooling, it is more difficult to craft easy solutions to the screen time issue.

During these times, it is more important than ever for pediatricians to check in on the mental health of patients with queries about how school is going, how patients are keeping contact with peers, and how are they processing social issues related to violence. Queries to families about the need for assistance with food insecurity, housing insecurity, and access to mental health services are necessary during this time of public emergency.

Medical school and COVID-19

Although medical school is an adult schooling experience, it affects not only the medical profession and our junior colleagues, but, by extrapolation, all education that requires hands-on experience or interning, and has been included for those reasons.

In the new COVID-19 era, medical schools have been forced to make drastic and quick changes to multiple levels of their curriculum to ensure both student and patient safety during the pandemic. Students entering their clinical rotations have had the most drastic alteration to their experience.

COVID-19 has led to some of the same changes high schools and colleges have adopted, specifically, replacement of large in-person lectures with small group activities small group discussion and virtual lectures. 32 The transition to an online format for medical education has been rapid and impacted both students and faculty. 33 , 34 In a survey by Singh and colleagues, 33 of the 192 students reporting 43.9% found online lectures to be poorer than physical classrooms during the pandemic. In another report by Shahrvini and colleagues, 35 of 104 students surveyed, 74.5% students felt disconnected from their medical school and their peers and 43.3% felt that they were unprepared for their clerkships. Although there are no pre-COVID-19 data for comparison, it is expected that the COVID-19 changes will lead to increased insecurity and feelings of poor preparation for clinical work.

Gross anatomy is a well-established tradition within the medical school curriculum and one that is conducted almost entirely in person and in close quarters around a cadaver. Harmon and colleagues 36 surveyed 67 gross anatomy educators and found that 8% were still holding in-person sessions and 34 ± 43% transitioned to using cadaver images and dissecting videos that could be accessed through the Internet.

Many third- and fourth-year medical students have seen periods of cancellation for clinical rotations and supplementation with online learning, telemedicine, or virtual rounds owing to the COVID-19 pandemic. 37 A study from Shahrvini and colleagues 38 found that an unofficial document from Reddit (a widely used social network platform with a subgroup for medical students and residents) reported that 75% of medical schools had canceled clinical activities for third- and fourth-year students for some part of 2020. In another survey by Harries and colleagues, 39 of the 741 students who responded, 93.7% were not involved in clinical rotations with in-person patient contact. The reactions of students varied, with 75.8% admitting to agreeing with the decision, 34.7% feeling guilty, and 27.0% feeling relieved. 39 In the same survey, 74.7% of students felt that their medical education had been disrupted, 84.1% said they felt increased anxiety, and 83.4% would accept the risk of COVID-19 infection if they were able to return to the clinical setting. 39

Since the start of the pandemic, medical schools have had to find new and innovative ways to continue teaching and exposing students to clinical settings. The use of electronic conferencing services has been critical to continuing education. One approach has been to turn to online applications like Google Hangouts, which come at no cost and offer a wide variety of tools to form an integrative learning environment. 32 , 37 , 40 Schools have also adopted a hybrid model of teaching where lectures can be prerecorded then viewed by the student asynchronously on their own time followed by live virtual lectures where faculty can offer question-and-answer sessions related to the material. By offering this new format, students have been given more flexibility in terms of creating a schedule that suits their needs and may decrease stress. 37

Although these changes can be a hurdle to students and faculty, it might prove to be beneficial for the future of medical training in some ways. Telemedicine is a growing field, and the American Medical Association and other programs have endorsed its value. 41 Telemedicine visits can still be used to take a history, conduct a basic visual physical examination, and build rapport, as well as performing other aspects of the clinical examination during a pandemic, and will continue to be useful for patients unable to attend regular visits at remote locations. Learning effectively now how to communicate professionally and carry out telemedicine visits may better prepare students for a future where telemedicine is an expectation and allow students to learn the limitations as well as the advantages of this modality. 41

Pandemic changes have strongly impacted the process of college applications, medical school applications, and residency applications. 32 For US medical residencies, 72% of applicants will, if the pattern from 2016 to 2019 continues, move between states or countries. 42 This level of movement is increasingly dangerous given the spread of COVID-19 and the lack of currently accepted procedures to carry out such a mass migration safely. The same follows for medical schools and universities.

We need to accept and prepare for the fact that medial students as well as other learners who require in-person training may lack some skills when they enter their profession. These skills will have to be acquired during a later phase of training. We may have less skilled entry-level resident physicians and nurses in our hospitals and in other clinical professions as well.

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected and will continue to affect the delivery of knowledge and skills at all levels of education. Although many children and adult learners will likely compensate for this interruption of traditional educational services and adapt to new modalities, some will struggle. The widening of the gap for those whose families cannot absorb the teaching and supervision of education required for in-home education because they lack the time and skills necessary are not addressed currently. The gap for those already at a disadvantage because of socioeconomic class, language, and special needs are most severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic school closures and will have the hardest time compensating. As pediatricians, it is critical that we continue to check in with our young patients about how they are coping and what assistance we can guide them toward in our communities.

Clinics care points

- • Learners and educators at all levels of education have been affected by COVID-19 restrictions with rapid adaptations to virtual learning platforms.

- • The impact of COVID-19 on learners is not evenly distributed and children of racial minorities, those who live in poverty, those requiring special education, and children who speak English as a second language are more negatively affected by the need for remote learning.

- • Math scores are more impacted than language arts scores by previous school closures and thus far by these shutdowns for COVID-19.

- • Anxiety and depression have increased in children and particularly in adolescents as a result of COVID-19 itself and as a consequence of school changes.

- • Pediatricians should regularly screen for unmet needs in their patients during the pandemic, such as food insecurity with the loss of school meals, an inability to adapt to remote learning and increased computer time, and heightened anxiety and depression as results of school changes.

The authors have nothing to disclose.

New Data Show How the Pandemic Affected Learning Across Whole Communities

- Posted May 11, 2023

- By News editor

- Disruption and Crises

- Education Policy

- Evidence-Based Intervention

Today, The Education Recovery Scorecard , a collaboration with researchers at the Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard University (CEPR) and Stanford University’s Educational Opportunity Project , released 12 new state reports and a research brief to provide the most comprehensive picture yet of how the pandemic affected student learning. Building on their previous work, their findings reveal how school closures and local conditions exacerbated inequality between communities — and the urgent need for school leaders to expand recovery efforts now.

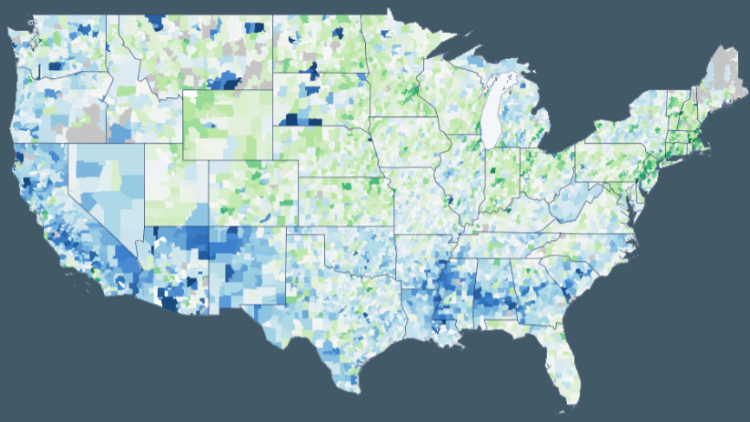

The research team reviewed data from 8,000 communities in 40 states and Washington, D.C., including 2022 NAEP scores and Spring 2022 assessments, COVID death rates, voting rates, and trust in government, patterns of social activity, and survey data from Facebook/Meta on family activities and mental health during the pandemic.

>> Read an op-ed by researchers Tom Kane and Sean Reardon in the New York Times .

They found that where children lived during the pandemic mattered more to their academic progress than their family background, income, or internet speed. Moreover, after studying instances where test scores rose or fell in the decade before the pandemic, the researchers found that the impacts lingered for years.

“Children have resumed learning, but largely at the same pace as before the pandemic. There’s no hurrying up teaching fractions or the Pythagorean theorem,” said CEPR faculty director Thomas Kane . “The hardest hit communities — like Richmond, Virginia, St. Louis, Missouri, and New Haven, Connecticut, where students fell behind by more than 1.5 years in math — have to teach 150 percent of a typical year’s worth of material for three years in a row — just to catch up. That is simply not going to happen without a major increase in instructional time. Any district that lost more than a year of learning should be required to revisit their recovery plans and add instructional time — summer school, extended school year, tutoring, etc. — so that students are made whole. ”

“It’s not readily visible to parents when their children have fallen behind earlier cohorts, but the data from 7,800 school districts show clearly that this is the case,” said Sean Reardon , professor of poverty and inequality, Stanford Graduate School of Education. “The educational impacts of the pandemic were not only historically large, but were disproportionately visited on communities with many low-income and minority students. Our research shows that schools were far from the only cause of decreased learning — the pandemic affected children through many ways — but they are the institution best suited to remedy the unequal impacts of the pandemic.”

The new research includes:

- A research brief that offers insights into why students in some communities fared worse than others.

- An update to the Education Recovery Scorecard, including data from 12 additional states whose 2022 scores were not available in October. The project now includes a district-level view of the pandemic’s effects in 40 states (plus D.C.).

- A new interactive map that highlights examples of inequity between neighboring school districts.

Among the key findings:

- Within the typical school district, the declines in test scores were similar for all groups of students, rich and poor, white, Black, Hispanic. And the extent to which schools were closed appears to have had the same effect on all students in a community, regardless of income or race.

- Test scores declined more in places where the COVID death rate was higher, in communities where adults reported feeling more depression and anxiety during the pandemic, and where daily routines of families were most significantly restricted. This is true even in places where schools closed only very briefly at the start of the pandemic.

- Test score declines were smaller in communities with high voting rates and high Census response rates — indicators of what sociologists call “institutional trust.” Moreover, remote learning was less harmful in such places. Living in a community where more people trusted the government appears to have been an asset to children during the pandemic.

- The average U.S. public school student in grades 3-8 lost the equivalent of a half year of learning in math and a quarter of a year in reading.

The researchers also looked at data from the decade prior to the pandemic to see how students bounced back after significant learning loss due to disruption in their schooling. The evidence shows that schools do not naturally bounce back: Affected students recovered 20–30% of the lost ground in the first year, but then made no further recovery in the subsequent three to four years.

“Schools were not the sole cause of achievement losses,” Kane said. “Nor will they be the sole solution. As enticing as it might be to get back to normal, doing so will just leave the devastating increase in inequality caused by the pandemic in place. We must create learning opportunities for students outside of the normal school calendar, by adding academic content to summer camps and after-school programs and adding an optional 13th year of schooling.”

The Education Recovery Scorecard is supported by funds from Citadel founder and CEO Kenneth C. Griffin, Carnegie Corporation of New York, and the Walton Family Foundation.

The latest research, perspectives, and highlights from the Harvard Graduate School of Education

Related Articles

Despite Progress, Achievement Gaps Persist During Recovery from Pandemic

New research finds achievement gaps in math and reading, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, remain and have grown in some states, calls for action before federal relief funds run out

New Research Provides the First Clear Picture of Learning Loss at Local Level

Road to COVID Recovery

The pandemic has had devastating impacts on learning. What will it take to help students catch up?

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, megan kuhfeld , megan kuhfeld senior research scientist - nwea @megankuhfeld jim soland , jim soland assistant professor, school of education and human development - university of virginia, affiliated research fellow - nwea @jsoland karyn lewis , and karyn lewis director, center for school and student progress - nwea @karynlew emily morton emily morton research scientist - nwea @emily_r_morton.

March 3, 2022

As we reach the two-year mark of the initial wave of pandemic-induced school shutdowns, academic normalcy remains out of reach for many students, educators, and parents. In addition to surging COVID-19 cases at the end of 2021, schools have faced severe staff shortages , high rates of absenteeism and quarantines , and rolling school closures . Furthermore, students and educators continue to struggle with mental health challenges , higher rates of violence and misbehavior , and concerns about lost instructional time .

As we outline in our new research study released in January, the cumulative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on students’ academic achievement has been large. We tracked changes in math and reading test scores across the first two years of the pandemic using data from 5.4 million U.S. students in grades 3-8. We focused on test scores from immediately before the pandemic (fall 2019), following the initial onset (fall 2020), and more than one year into pandemic disruptions (fall 2021).

Average fall 2021 math test scores in grades 3-8 were 0.20-0.27 standard deviations (SDs) lower relative to same-grade peers in fall 2019, while reading test scores were 0.09-0.18 SDs lower. This is a sizable drop. For context, the math drops are significantly larger than estimated impacts from other large-scale school disruptions, such as after Hurricane Katrina—math scores dropped 0.17 SDs in one year for New Orleans evacuees .

Even more concerning, test-score gaps between students in low-poverty and high-poverty elementary schools grew by approximately 20% in math (corresponding to 0.20 SDs) and 15% in reading (0.13 SDs), primarily during the 2020-21 school year. Further, achievement tended to drop more between fall 2020 and 2021 than between fall 2019 and 2020 (both overall and differentially by school poverty), indicating that disruptions to learning have continued to negatively impact students well past the initial hits following the spring 2020 school closures.

These numbers are alarming and potentially demoralizing, especially given the heroic efforts of students to learn and educators to teach in incredibly trying times. From our perspective, these test-score drops in no way indicate that these students represent a “ lost generation ” or that we should give up hope. Most of us have never lived through a pandemic, and there is so much we don’t know about students’ capacity for resiliency in these circumstances and what a timeline for recovery will look like. Nor are we suggesting that teachers are somehow at fault given the achievement drops that occurred between 2020 and 2021; rather, educators had difficult jobs before the pandemic, and now are contending with huge new challenges, many outside their control.

Clearly, however, there’s work to do. School districts and states are currently making important decisions about which interventions and strategies to implement to mitigate the learning declines during the last two years. Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) investments from the American Rescue Plan provided nearly $200 billion to public schools to spend on COVID-19-related needs. Of that sum, $22 billion is dedicated specifically to addressing learning loss using “evidence-based interventions” focused on the “ disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on underrepresented student subgroups. ” Reviews of district and state spending plans (see Future Ed , EduRecoveryHub , and RAND’s American School District Panel for more details) indicate that districts are spending their ESSER dollars designated for academic recovery on a wide variety of strategies, with summer learning, tutoring, after-school programs, and extended school-day and school-year initiatives rising to the top.

Comparing the negative impacts from learning disruptions to the positive impacts from interventions

To help contextualize the magnitude of the impacts of COVID-19, we situate test-score drops during the pandemic relative to the test-score gains associated with common interventions being employed by districts as part of pandemic recovery efforts. If we assume that such interventions will continue to be as successful in a COVID-19 school environment, can we expect that these strategies will be effective enough to help students catch up? To answer this question, we draw from recent reviews of research on high-dosage tutoring , summer learning programs , reductions in class size , and extending the school day (specifically for literacy instruction) . We report effect sizes for each intervention specific to a grade span and subject wherever possible (e.g., tutoring has been found to have larger effects in elementary math than in reading).

Figure 1 shows the standardized drops in math test scores between students testing in fall 2019 and fall 2021 (separately by elementary and middle school grades) relative to the average effect size of various educational interventions. The average effect size for math tutoring matches or exceeds the average COVID-19 score drop in math. Research on tutoring indicates that it often works best in younger grades, and when provided by a teacher rather than, say, a parent. Further, some of the tutoring programs that produce the biggest effects can be quite intensive (and likely expensive), including having full-time tutors supporting all students (not just those needing remediation) in one-on-one settings during the school day. Meanwhile, the average effect of reducing class size is negative but not significant, with high variability in the impact across different studies. Summer programs in math have been found to be effective (average effect size of .10 SDs), though these programs in isolation likely would not eliminate the COVID-19 test-score drops.

Figure 1: Math COVID-19 test-score drops compared to the effect sizes of various educational interventions

Source: COVID-19 score drops are pulled from Kuhfeld et al. (2022) Table 5; reduction-in-class-size results are from pg. 10 of Figles et al. (2018) Table 2; summer program results are pulled from Lynch et al (2021) Table 2; and tutoring estimates are pulled from Nictow et al (2020) Table 3B. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals are shown with vertical lines on each bar.

Notes: Kuhfeld et al. and Nictow et al. reported effect sizes separately by grade span; Figles et al. and Lynch et al. report an overall effect size across elementary and middle grades. We were unable to find a rigorous study that reported effect sizes for extending the school day/year on math performance. Nictow et al. and Kraft & Falken (2021) also note large variations in tutoring effects depending on the type of tutor, with larger effects for teacher and paraprofessional tutoring programs than for nonprofessional and parent tutoring. Class-size reductions included in the Figles meta-analysis ranged from a minimum of one to minimum of eight students per class.

Figure 2 displays a similar comparison using effect sizes from reading interventions. The average effect of tutoring programs on reading achievement is larger than the effects found for the other interventions, though summer reading programs and class size reduction both produced average effect sizes in the ballpark of the COVID-19 reading score drops.

Figure 2: Reading COVID-19 test-score drops compared to the effect sizes of various educational interventions

Source: COVID-19 score drops are pulled from Kuhfeld et al. (2022) Table 5; extended-school-day results are from Figlio et al. (2018) Table 2; reduction-in-class-size results are from pg. 10 of Figles et al. (2018) ; summer program results are pulled from Kim & Quinn (2013) Table 3; and tutoring estimates are pulled from Nictow et al (2020) Table 3B. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals are shown with vertical lines on each bar.

Notes: While Kuhfeld et al. and Nictow et al. reported effect sizes separately by grade span, Figlio et al. and Kim & Quinn report an overall effect size across elementary and middle grades. Class-size reductions included in the Figles meta-analysis ranged from a minimum of one to minimum of eight students per class.

There are some limitations of drawing on research conducted prior to the pandemic to understand our ability to address the COVID-19 test-score drops. First, these studies were conducted under conditions that are very different from what schools currently face, and it is an open question whether the effectiveness of these interventions during the pandemic will be as consistent as they were before the pandemic. Second, we have little evidence and guidance about the efficacy of these interventions at the unprecedented scale that they are now being considered. For example, many school districts are expanding summer learning programs, but school districts have struggled to find staff interested in teaching summer school to meet the increased demand. Finally, given the widening test-score gaps between low- and high-poverty schools, it’s uncertain whether these interventions can actually combat the range of new challenges educators are facing in order to narrow these gaps. That is, students could catch up overall, yet the pandemic might still have lasting, negative effects on educational equality in this country.

Given that the current initiatives are unlikely to be implemented consistently across (and sometimes within) districts, timely feedback on the effects of initiatives and any needed adjustments will be crucial to districts’ success. The Road to COVID Recovery project and the National Student Support Accelerator are two such large-scale evaluation studies that aim to produce this type of evidence while providing resources for districts to track and evaluate their own programming. Additionally, a growing number of resources have been produced with recommendations on how to best implement recovery programs, including scaling up tutoring , summer learning programs , and expanded learning time .

Ultimately, there is much work to be done, and the challenges for students, educators, and parents are considerable. But this may be a moment when decades of educational reform, intervention, and research pay off. Relying on what we have learned could show the way forward.

Related Content

Megan Kuhfeld, Jim Soland, Beth Tarasawa, Angela Johnson, Erik Ruzek, Karyn Lewis

December 3, 2020

Lindsay Dworkin, Karyn Lewis

October 13, 2021

Education Policy K-12 Education

Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy

Emily Markovich Morris, Laura Nóra, Richaa Hoysala, Max Lieblich, Sophie Partington, Rebecca Winthrop

May 31, 2024

Online only

9:30 am - 11:00 am EDT

Annelies Goger, Katherine Caves, Hollis Salway

May 16, 2024

How COVID-19 caused a global learning crisis

Executive summary.

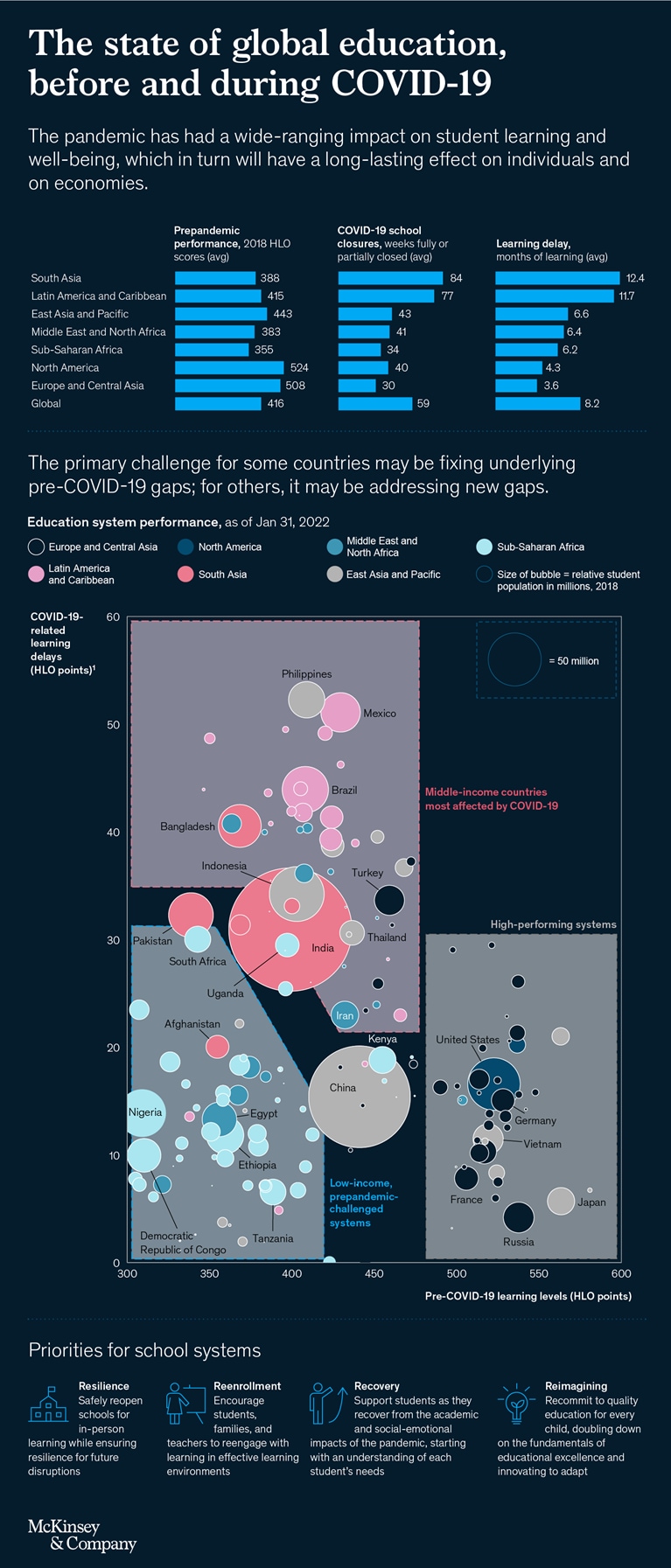

In our latest report on unfinished learning, we examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on student learning and well-being, and identify potential considerations for school systems as they support students in recovery and beyond. Our key findings include the following:

- The length of school closures varied widely across the world. School buildings in middle-income Latin America and South Asia were fully or partially closed the longest—for 75 weeks or more. Those in high-income Europe and Central Asia were fully or partially closed for less time (30 weeks on average), as were those in low-income sub-Saharan Africa (34 weeks on average).

About the authors

This article is a collaborative effort by Jake Bryant , Felipe Child , Emma Dorn , Jose Espinosa, Stephen Hall , Topsy Kola-Oyeneyin , Cheryl Lim, Frédéric Panier, Jimmy Sarakatsannis , Dirk Schmautzer , Seckin Ungur , and Bart Woord, representing views from McKinsey’s Education Practice.

- Access to quality remote and hybrid learning also varied both across and within countries. In Tanzania, while school buildings were closed, children in just 6 percent of households listened to radio lessons, 5 percent accessed TV lessons, and fewer than 1 percent participated in online learning. 1 Jacobus Cilliers and Shardul Oza, “What did children do during school closures? Insights from a parent survey in Tanzania,” Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE), May 19, 2021.

- Furthermore, pandemic-related learning delays stack up on top of historical learning inequities. The World Bank estimates that while students in high-income countries gained an average of 50 harmonized learning outcomes (HLO) points a year prepandemic, students in low-income countries were gaining just 20, leaving those students several years behind. 2 Noam Angrist et al., “Measuring human capital using global learning data,” Nature , March 2021, Volume 592.

- High-performing systems, with relatively high levels of pre-COVID-19 performance, where students may be about one to five months behind due to the pandemic (for example, North America and Europe, where students are, on average, four months behind).

- Low-income prepandemic-challenged systems, with very low levels of pre-COVID-19 learning, where students may be about three to eight months behind due to the pandemic (for example, sub-Saharan Africa, where students are on average six months behind).

- Pandemic-affected middle-income systems, with moderate levels of pre-COVID-19 learning, where students may be nine to 15 months behind (for example, Latin America and South Asia, where students are, on average, 12 months behind).

- The pandemic also increased inequalities within systems. For example, it widened gaps between majority Black and majority White schools in the United States and increased preexisting urban-rural divides in Ethiopia.

- Beyond learning, the pandemic has had broader social and emotional impacts on students globally—with rising mental-health concerns, reports of violence against children, rising obesity, increases in teenage pregnancy, and rising levels of chronic absenteeism and dropouts.

- Lower levels of learning translate into lower future earnings potential for students and lower economic productivity for nations. By 2040, the economic impact of pandemic-related learning delays could lead to annual losses of $1.6 trillion worldwide, or 0.9 percent of total global GDP.

- Resilience: Safely reopen schools for in-person learning while ensuring resilience for future disruptions.

- Reenrollment: Encourage students, families, and teachers to reengage with learning in effective learning environments.

- Recovery: Support students as they recover from the academic and social-emotional impacts of the pandemic, starting with an understanding of each student’s needs.

- Reimagining: Recommit to quality education for every child, doubling down on the fundamentals of educational excellence and innovating to adapt.

In some parts of the world, students, parents, and teachers may be experiencing a novel feeling: cautious optimism. After two years of disruptions from COVID-19, the overnight shift to online and hybrid learning, and efforts to safeguard teachers, administrators, and students, cities and countries are seeing the first signs of the next normal. Masks are coming off. Events are being held in person. Extracurricular activities are back in full swing.

These signs of hope are counterbalanced by the lingering, widespread impact of the pandemic. While it’s too early to catalog all of the ways students have been affected, we are starting to see initial indications of the toll COVID-19 has taken on learning around the world. Our analysis of available data found no country was untouched, but the impact varied across regions and within countries. Even in places with effective school systems and near-universal connectivity and device access, learning delays were significant, especially for historically vulnerable populations. 3 Emma Dorn, Bryan Hancock, Jimmy Sarakatsannis, and Ellen Viruleg, “ COVID-19 and education: An emerging K-shaped recovery ,” McKinsey, December 14, 2021. In many countries that had poor education outcomes before the pandemic, the setbacks were even greater. In those countries, an even more ambitious, coordinated effort will likely be required to address the disruption students have experienced.

Our analysis highlights the extent of the challenge and demonstrates how the impact of the pandemic on learning extends across students, families, and entire communities. Beyond the direct effect on students, learning delays have the potential to affect economic growth: by 2040, according to McKinsey analysis, COVID-19-related unfinished learning could translate into $1.6 trillion in annual losses to the global economy.

Acting decisively in the near term could help to address learning delays as well as the broader social, emotional, and mental-health impact on students. In mobilizing to respond to the pandemic’s effect on student learning and thriving, countries also may need to reassess their education systems—what has been working well and what may need to be reimagined in light of the past two years. Our hope is that this article’s analysis provides a potential starting point for dialogue as nations seek to reinvigorate their education systems.

Gauging the pandemic’s widespread impact on education

One of the challenges in assessing the global effect of the pandemic on learning is the lack of data. Comparative international assessments mostly cover middle- to high-income countries and have not been carried out since the beginning of the pandemic. The next Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), for example, was delayed until 2022. 4 “PISA,” OECD, accessed March 30, 2022. Similarly, many countries had to cancel or defer national assessments. As a result, few nations have a complete data set, and many have no assessment data to indicate relative learning before and since school closures. Accordingly, our methodology used available data augmented by informed assumptions to get a directional picture of the pandemic’s effects on the scholastic achievement and well-being of students.

The pandemic’s impact on student learning

We evaluated the potential effect of the pandemic on student learning by multiplying the amount of time school was disrupted in each country by the estimated effectiveness of the schooling students received during disruptions.

The duration of school closures ran the gamut. During the 102-week period we studied (from the onset of COVID-19 to January 2022), school buildings in Latin America, including the Caribbean, and South Asia were fully or partially closed for 75 weeks or more, while those in Europe and Central Asia were fully or partially closed for an average of 30 weeks (Exhibit 1). Schools in some regions began reopening a few months into the pandemic, but as of January 2022, more than a quarter of the world’s student population resided in school systems where schools were not yet fully open.

Remote and hybrid learning similarly varied widely across and within countries. Some students were supported by internet access, devices, learning management systems, adaptive learning software, live videoconferencing with teachers and peers, and home environments with parents or hired professionals to support remote learning. Others had access to radio or television programs, paper packages, and text messaging. Some students may not have had access to any learning options. 5 What’s next? Lessons on education recovery: Findings from a survey of ministries of education amid the COVID-19 pandemic , UNESCO, UNICEF, the World Bank, and OECD, June 2021. We used the World Bank’s estimates on “mitigation effectiveness” by country income level to account for different levels of access to learning tools and quality through the pandemic (see the forthcoming methodological appendix for more details).

Our model suggests that in the first 23 months since the start of the pandemic, students around the world may have lost about eight months of learning, on average, with meaningful disparities across and within regions and countries. For example, students in South Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean may be more than a year behind where they would have been absent the pandemic. In North America and Europe, students might be an average of four months behind (Exhibit 2).

The regional numbers only begin to tell the full story. The greater the range of school system performance and resources across regions, the greater the variation in student experiences. Students in Japan and Australia may be less than two months behind, while students in the Philippines and Indonesia may be more than a year behind where they would have been (Exhibit 3).

Within countries, the impact of COVID-19 has also affected individual students differently. Wherever assessments have taken place since the onset of the pandemic, they suggest widening gaps in both opportunity and achievement. Historically vulnerable and marginalized students are at an increased risk of falling further behind.

In the United States, students in majority Black schools were half a year behind in mathematics and reading by fall 2021, while students in majority White schools were just two months behind. 6 “ COVID-19 and education: An emerging K-shaped recovery ,” December 14, 2021. In Ethiopia, students in rural areas achieved under one-third of the expected learning from March to October 2020, while those in urban areas learned less than half of the expected amount. 7 Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE) , “Learning inequalities widen following COVID-19 school closures in Ethiopia,” blog entry by Janice Kim, Pauline Rose, Ricardo Sabates, Dawit Tibebu Tiruneh, and Tassew Woldehanna, May 4, 2021. Assessments in New South Wales, Australia, detected minimal impact on learning overall, but third-grade students in the most disadvantaged schools experienced two months less growth in mathematics. 8 Leanne Fray et al., “The impact of COVID-19 on student learning in New South Wales primary schools: An empirical study,” The Australian Educational Researcher , 2021, Volume 48.

Would you like to learn more about our Education Practice ?

Covid-19-related losses on top of historical inequalities.

The learning crisis is not new. In the years before COVID-19, many school systems faced challenges in providing learning opportunities for many of their students. The World Bank estimates that before the pandemic, more than half of students in low- and middle-income countries were living in “learning poverty”—unable to read and understand a simple text by age ten. That number may rise as high as 70 percent due to pandemic-related school disruptions. 9 Joao Azevedo et al., “The state of the global education crisis: A path to recovery,” World Bank Group, December 3, 2021.

The World Bank’s harmonized learning outcomes (HLOs) compare learning achievement and growth across countries. This measure combines multiple global student assessments into one metric, with a range of 625 for advanced attainment and 300 for minimum attainment. According to the World Bank’s 2018 HLO database, students from some countries in the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia were several years behind their counterparts in North America and Europe before the pandemic (Exhibit 4). 10 Data Blog , “Harmonized learning outcomes: transforming learning assessment data into national education policy reforms,” blog entry by Harry A. Patrinos and Noam Angrist, August 12, 2019.

Students in these countries were also progressing more slowly each year in school. While students in high-income countries may have been gaining 50 HLO points in a year, students in low-income countries were gaining just 20. In other words, not much learning was happening in some countries even before the pandemic.

Prepandemic learning levels and pandemic-related learning delays interacted in different ways in different countries and regions. Although each country is unique, three archetypes emerge based on the performance of education systems (Exhibit 5).

High-performing systems. Countries in this archetype generally had higher pre-COVID-19 learning levels. Systems had more capacity for remote learning, and school buildings remained closed for shorter time periods. 11 “Education: From disruption to recovery,” UNESCO, accessed March 11, 2022. Data suggest that after the initial shock of the pandemic in 2020, learning delays increased only moderately with subsequent school closures in the 2021–22 school year. Some high-income countries seem to show little evidence of decreased learning overall. According to the Australian National Assessment Program–Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN), the COVID-19 pandemic did not have a statistically significant impact on average student literacy and numeracy levels, even in Victoria, where learning was remote for more than 120 days. 12 “Highlights from Victorian preliminary results in NAPLAN 2021,” Victoria state government, August 26, 2021; Adam Carey, Melissa Cunningham, and Anna Prytz, “‘Children have suffered enormously’: School closures leave experts divided,” The Age , Melbourne, July 25, 2021. However, in many high-income countries, the impact of the pandemic on learning remained significant. Assessments of student learning in the United States in fall 2021 suggested students had fallen four months behind in mathematics and three months behind in reading. 13 “ COVID-19 and education: An emerging K-shaped recovery ,” December 14, 2021. Inequalities in learning also increased within many of these countries, with historically marginalized students most affected.

Lower-income, prepandemic-challenged systems. This archetype consists of mostly low-income and lower-middle-income countries with very low levels of pre-COVID-19 learning. When the pandemic struck, school buildings closed for varying periods of time, 14 “Education: From disruption to recovery,” UNESCO, accessed March 11, 2022. with limited options for remote learning. In Tanzania, for example, schools were closed for 15 weeks, and during this period, just 6 percent of households reported that their children listened to radio lessons, 5 percent watched TV lessons, and fewer than 1 percent accessed educational programs on the internet. 15 Jacobus Cilliers and Shardul Oza, “What did children do during school closures? Insights from a parent survey in Tanzania,” Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE), May 19, 2021. Across the analyzed time period, schools in sub-Saharan Africa were fully open for more weeks, on average, than schools in any other region. As a result, the pandemic’s impact on learning was relatively muted, even though many of these systems faced challenges with effective remote learning. 16 A report of six countries in Africa, for example, found limited impact of the pandemic on already-low student outcomes. For more information, see “MILO: Monitoring impacts on learning outcomes,” UNESCO, accessed March 11, 2022.

These relatively smaller pandemic learning delays are likely due in part to the limited progress students were making in schools before COVID-19. 17 World Bank blogs , “Harmonized learning outcomes: Transforming learning assessment data into national education policy reforms,” blog entry by Harry A. Patrinos and Noam Angrist, August 12, 2019. If students weren’t progressing scholastically when schools were open, closures were likely to have less impact. In Tanzania before the pandemic, three-quarters of students in grade three could not read a basic sentence. 18 “What did children do during school closures?,” May 19, 2021.

Pandemic-affected middle-income systems. School systems in Latin American and South Asian countries had low to moderate performance before COVID-19. Many middle-income countries in this group did have some capacity to plan and roll out remote-learning options, especially in urban areas. 19 “Responses to Educational Disruption Survey (REDS),” UNESCO, accessed March 11, 2022. However, pandemic-related disruptions caused widespread school closures for extended periods of time—more than 50 weeks in some countries. 20 “Education: From disruption to recovery,” UNESCO, accessed March 11, 2022. The resulting learning delays may represent a true crisis for major economies such as India, Indonesia, and Mexico, where students are more than a year behind, on average.

While some students may have just learned more slowly than they would have absent the pandemic, others in this archetype may have actually slipped backward. A study by the Azim Premji Foundation suggests that as early as January 2021, more than 90 percent of students assessed in India have lost at least one language ability (such as reading words or writing simple sentences), while more than 80 percent lost a math ability (for example, identifying single- and double-digit numbers or naming shapes). 21 Loss of learning during the pandemic , Azim Premji Foundation, February 2021. This pattern could be particularly challenging, since higher-order skills are increasingly important in middle-income countries with rising levels of workplace automation. McKinsey’s “ Jobs lost, jobs gained ” report 22 For more information, see “ Jobs lost, jobs gained: What the future of work will mean for jobs, skills, and wages ,” McKinsey Global Institute, November 28, 2017. suggests India may need 34 million to 100 million more high school graduates by 2030 to fill workplace demands. The pandemic has put existing high school graduation rates at risk, let alone the vast expansion required to meet future demand for workers.

The pandemic’s effects beyond learning

Much of the dialogue around school systems focuses on educational achievement, but schools offer more than academic instruction. A school system’s contributions may include social interaction; an opportunity for students to build relationships with caring adults; a base for extracurricular activities, from the arts to athletics; an access point for physical- and mental-health services; and a guarantee of balanced meals on a regular basis. The school year may also enable students to track their progress and celebrate milestones. When schools had to close for extended periods of time or move to hybrid learning, students were deprived of many of these benefits.

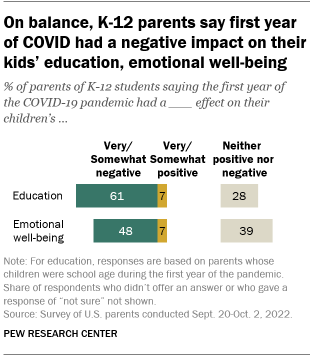

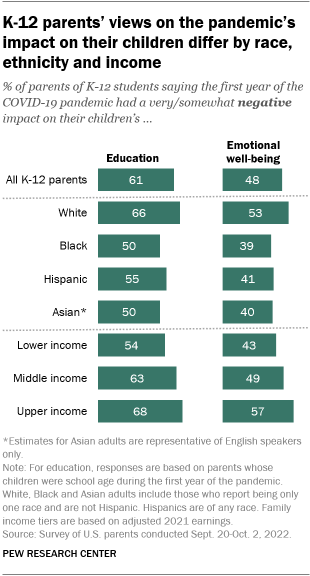

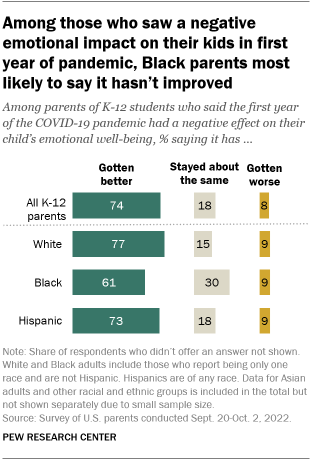

The pandemic’s impact on the social-emotional and mental and physical health of students has been measured even less than its impact on academic achievement, but early indications are concerning. Save the Children reports that 83 percent of children and 89 percent of parents globally have reported an increase in negative feelings since the pandemic began. 23 The hidden impact of COVID-19 on child protection and wellbeing , Save the Children International, September 2020. In the United States, one in three parents said they were very or extremely worried about their child’s mental health in spring 2021, with rising reported levels of student anxiety, depression, social withdrawal, and lethargy. 24 Emma Dorn, Bryan Hancock, Jimmy Sarakatsannis, and Ellen Viruleg, “ COVID-19 and education: The lingering effects of unfinished learning ,” McKinsey, July 27, 2021. Parents of Black and Hispanic students, the segments most affected by academic unfinished learning, also reported higher rates of concern about their student’s mental health and engagement with school. A UK survey found 53 percent of girls and 44 percent of boys aged 13 to 18 had experienced symptoms or trauma related to COVID-19. 25 Report1: Impact of COVID-19 on young people aged 13-24 in the UK- preliminary findings , PsyArXiv, January 20, 2021. In Bangladesh, a cross-sectional study revealed that 19.3 percent of children suffered moderate mental-health impacts, while 7.2 percent suffered from extreme mental-health effects. 26 Rajon Banik et al., “Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of children in Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study,” Children and Youth Services Review , October 2020, Volume 117. Reports of violence against children rose in many countries. 27 “Publications,” Young Lives, accessed March 22, 2022. The pandemic affected physical health as well. Studies from the United States 28 Roger Riddell, “CDC: Child obesity jumped during COVID-19 pandemic,” K-12 Dive , September 24, 2021. and the United Kingdom 29 The annual report of Her Majesty’s chief inspector of education, children’s services and skills 2020/21 , Ofsted, December 7, 2021. show rising rates of childhood obesity. In Latin America and the Caribbean, more than 80 million children stopped receiving hot meals. 30 “We can move to online learning, but not online eating,” United Nations World Food Program, March 26, 2020. In Uganda, a record number of monthly teenage pregnancies—more than 32,000—were recorded from March 2020 to September 2021. 31 “Uganda overwhelmed by 32,000 monthly teen pregnancies,” Yeni Şafak , December 12, 2021.

Some students may never return to formal schooling at all. Even in high-income systems, levels of chronic absenteeism are rising, and some students have not reengaged in school. In the United States, 1.7 million to 3.3 million eighth to 12th graders may drop out of school because of the pandemic. In low- and middle-income countries, the situation could be far worse. Up to one-third of Ugandan students may not return to the classroom. This pattern is in line with past historical crises involving school closures. After the Ebola pandemic, 13 percent of students in Sierra Leone and 25 percent of students in Liberia dropped out of school, with girls and low-income students most affected. 32 The socio-economic impacts of Ebola in Liberia , World Bank, April 15, 2015; The socio-economic impacts of Ebola in Sierra Leone , World Bank, June 15, 2015. Among the poorest primary-school students in Sierra Leone, dropout rates increased by more than 60 percent. 33 William C. Smith, “Consequences of school closure on access to education: Lessons from the 2013-2016 Ebola pandemic,” International Review of Education , April 2021, Volume 67. This may result in reduced employment opportunities and lifelong earnings potential for many of these students.

The potential of long-term economic damage

Education can affect not just an individual’s future earnings and well-being but also a country’s economic growth and vitality. Research suggests higher levels of education lead to increased labor productivity and enhance an economy’s capacity for innovation. Unless the pandemic’s impact on student learning can be mitigated and students can be supported to catch up on missed learning, the global economy could experience lower GDP growth over the lifetime of this generation.

We estimate by 2040, unfinished learning related to COVID-19 could translate to annual losses of $1.6 trillion to the global economy, or 0.9 percent of predicted total GDP (Exhibit 6).

Although the total dollar amount of forgone GDP is highest in the largest economies of the world (encompassing East Asia, Europe, and North America), the relative impact is highest in regions with the greatest learning delays. In Latin America and the Caribbean, pandemic-related school closures could result in losses of more than 2 percent of GDP annually by 2040 and in subsequent years.

Economic impact could be affected further if students don’t return to school and cease learning altogether.

Identifying potential solutions

The response to the learning crisis will likely vary from country to country, based upon preexisting educational performance, the depth and breadth of learning delays, and system resources and capacity to respond. That said, all school systems will likely need to plan across multiple horizons:

As 2022 began, more than 95 percent of school systems around the world were at least partially open for traditional in-person learning. 34 “Responses to Educational Disruption Survey (REDS),” UNESCO, 2022, accessed March 11, 2022. That progress is encouraging but tenuous. Many systems reopened only to close down again when another wave of COVID-19 caused additional disruptions. Even within partially open systems, not all students have access to in-person learning, and many are still attending partial days or weeks. Building resilience could mean ensuring protocols are in place for safe and supportive in-person learning, and ensuring plans are in place to provide remote options that support the whole child at the system, school, and student levels in response to future crises. School systems can also benefit by creating the flexibility to change policies and procedures as new data and circumstances arise.

COVID-19 and education: The lingering effects of unfinished learning

Reenrollment.

Opening buildings and embedding effective safety precautions have been challenging for many systems, but ensuring students and teachers actually turn up and reengage with learning is perhaps even more difficult. Even where in-person learning has resumed, many students have not returned or remain chronically absent. 35 Indira Dammu, Hailly T.N. Korman, and Bonnie O’Keefe, Missing in the margins 2021: Revisiting the COVID-19 attendance crisis , Bellwether Education Partners, October 21, 2021. Families may still have safety worries about in-person learning. Some students may have found jobs and now rely on that income. 36 Elias Biryabarema, “Student joy, dropout heartache as Uganda reopens schools after long COVID-19 shutdown,” Reuters, January 10, 2022. Others may have become pregnant or now act as caregivers at home. 37 Brookings Education Plus Development , “What do we know about the effects of COVID-19 on girls’ return to school?,” blog entry by Erin Ganju, Christina Kwauk, and Dana Schmidt, September 22, 2021. Still others may feel so far behind academically or so disconnected from the school environment at a social level that a return feels impossible. A multipronged approach could be helpful to understand the barriers students may face, how those could differ across student segments, and ways to support all students in continuing their educational journeys.

Systems could consider a tiered approach to support reengagement. Tier-one interventions could be rolled out for all students and include both improving school offerings for families and students and communicating about enhanced services. This might involve back-to-school awareness campaigns at the national and community levels featuring respected community members, clear communication of safety protocols, access to free food and other basic needs on campuses, and the promotion of a positive school climate with deep family engagement.

Tier-two interventions, which could be directed at students who are at heightened risk of not returning to school, may involve more targeted support. These efforts might include community events and canvassing to bring school buses or mobile libraries to historically marginalized neighborhoods, phone- or text-banking aimed at students who have not returned to school, or summer opportunities (including fun reorientation activities) to convince students to return to the school campus. At the student level, it could include providing some groups of students with deeper learning or social-emotional recovery services to help them reintegrate into school.

Tier-three interventions encompass more intensive and specialized support. These efforts may include visits to the homes of individual students or new educational environments tailored to student needs—for example, night schools for students who need to complete high school while working.

Once students are back in school, many may need support to recover from the academic and social-emotional effects of the pandemic. Indeed, while academic recovery seems daunting, supporting the mental-health and social-emotional needs of students may end up being the bigger challenge. 38 Protecting youth mental health: The U.S. surgeon general’s advisory , U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2021. This process starts with a recognition that each child is unique and that the pandemic has affected different students in different ways. Understanding each student’s situation, in terms of both learning and well-being, is important at the classroom level, with teachers and administrators trained to interpret cues from students and refer them to more intensive support when necessary. Assessments will likely also be needed at the school and system levels to plan the response.

With an understanding of both the depth and breadth of student needs, systems and schools could consider three levers of academic acceleration: more time, more dedicated attention, and more focused content. Implementation of these levers will likely vary by context, but the overall goals are the same: to overcome both historical gaps and new COVID-19-related losses, and to do so across academic and whole-child indicators.

In high-income countries, digital formative assessments could help determine in real time what students know, where they may have gaps, and what the next step could be for each child. More relational tactics can be incorporated alongside digital assessments, such as teachers taking the time to connect with each child around a simple reading assessment, which may rebuild relationships and connectivity while assessing student capabilities. Schools could also consider universal mental-health diagnostics and screeners, and train teachers and staff to recognize the signs of trauma in students.

Once schools have identified students who need academic support, proven, evidence-based solutions could support acceleration in high-income school systems. High-dosage tutoring, for example, could enable students to learn one to two additional years of mathematics in a single year. Delivered three to five times a week by trained college graduates during the school day on top of regular math instruction, this type of tutoring is labor and capital intensive but has a high return on investment. Acceleration academies, which provide 25 hours of targeted instruction in reading to small groups of eight to 12 students during vacations, have helped students gain three months of reading in just one week. Exposing students to grade-level content and providing them with targeted supports and scaffolds to access this content has improved course completion rates by two to four times over traditional “re-teaching” remediation approaches.

With an understanding of both the depth and breadth of student needs, systems and schools could consider three levers of academic acceleration: more time, more dedicated attention, and more focused content.

In low- and middle-income countries, where learning delays may have been much greater and where the financial and human-capital resources for education can be more limited, different implementation approaches may be required. Simple, fast, inexpensive, and low-stakes evaluations of student learning could be carried out at the classroom level using pen and paper, oral assessments, and mobile data collection, for example.

Solutions for supporting the acceleration of student learning in these contexts could start with ensuring foundational literacy and numeracy (FLN), prioritizing essential standards and content. Evidence-based teaching methods could speed up learning; for example, Pratham’s Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL) approach—which groups children by learning needs, rather than by age or grade, and dedicates time to basic skills with continual reassessment—has led to improvements of more than a year of learning in classrooms and summer camps. 39 Improvements of 0.2 to 0.7 standard deviations; assuming that one year of learning ranges from 0.2 of a standard deviation in low income countries and 0.5 of a standard deviation in high income countries, in accordance with World Bank assumptions:; João Pedro Azevedo et al., Simulating the potential impacts of COVID-19 school closures on schooling and learning outcomes , World Bank working paper 9284, June 2020; David K. Evans and Fei Yuan, Equivalent years of schooling , World Bank working paper 8752, February 2019. Even with the application of existing approaches, more time in class may be required—with options to extend the school year or school day to support students. Widespread tutoring may not be realistic in some countries, but peer-to-peer tutoring and cross-grade mentoring and coaching could supplement in-class efforts. 40 COVID-19 response–remediation: Helping students catch up on lost learning, with a focus on closing equity gaps , UNESCO, July 2020.

Reimagining

In addition to accelerating learning in the short term, systems can also use this moment to consider how to build better systems for the future. This may involve both recommitting to the core fundamentals of educational excellence and reimagining elements of instruction, teaching, and leadership for a post-COVID-19 world. 41 Jake Bryant, Emma Dorn, Stephen Hall, and Frédéric Panier, “ Reimagining a more equitable and resilient K-12 education system ,” McKinsey, September 8, 2020. A lot of ground could be covered by rolling out existing evidence-based interventions at scale—recommitting to core literacy and numeracy skills, high-quality instructional materials, job-embedded teacher coaching, and effective performance management. Recommitting to these basics, however, may not be enough. Systems can also innovate across multiple dimensions: providing whole-child supports, using technology to improve access and quality, moving toward competency-based learning, and rethinking teacher preparation and roles, school structures, and resource allocation.

For example, many systems are reemphasizing the importance of caring for the whole child. Integrating social-emotional learning for all students, providing trauma-informed training for teachers and staff, 42 “Welcome to the trauma-informed educator training series,” Mayerson Center for Safe and Healthy Children, accessed March 22, 2022. and providing counseling and more intensive support on and off campus for some students could provide supportive schooling environments beyond immediate crisis support. 43 “District student wellbeing services reflection tool,” Chiefs for Change, January 2022. A UNESCO survey suggests that 78 percent of countries offered psychosocial and emotional support to teachers as a response to the pandemic. 44 What’s next? Lessons on education recovery , June 2021. Looking forward, the State of California is launching a $3 billion multiyear transition to community schools, taking an integrated approach to students’ academic, health, and social-emotional needs in the context of the broader community in which those students live. 45 John Fensterwald, “California ready to launch $3 billion, multiyear transition to community schools,” EdSource, January 31, 2022.

The role of education technology in instruction is another much-debated element of reimagining. Proponents believe education technology holds promise to overcome human-capital challenges to improved access and quality, especially given the acceleration of digital adoption during the pandemic. Others point out that historical efforts to harness technology in education have not yielded results at scale. 46 Jake Bryant, Felipe Child, Emma Dorn, and Stephen Hall, “ New global data reveal education technology’s impact on learning ,” McKinsey, June 12, 2020.

Numerous experiments are under way in low- and middle-income countries where human capital challenges are the greatest. Robust solar-powered tablets loaded with the evidence-based literacy and numeracy app one billion led to learning gains of more than four months 47 “Helping children achieve their full potential,” Imagine Worldwide, accessed March 22, 2022. in Malawi, with plans to roll out the program across the country’s 5,300 primary schools. 48 “Partners and projects,” onebillion.org, accessed March 22, 2022. NewGlobe’s digital teacher guides provide scripted lesson plans on devices designed for low-infrastructure environments. In Nigeria, students using these tools progressed twice as fast in numeracy and three times as fast in literacy as their peers. 49 “The EKOEXCEL effect,” NewGlobe Schools, accessed March 22, 2022. As new solutions are rolled out, it will likely be important to continually evaluate their impact compared with existing evidence-based approaches to retain what is working and discard that which is not.

Charting a potential path forward

There is no precedent for global learning delays at this scale, and the increasing automation of the workforce advances the urgency of supporting students to catch up to—and possibly exceed—prepandemic education levels to thrive in the global economy. Systems will likely need resources, knowledge, and organizational capacity to make progress across these priorities.