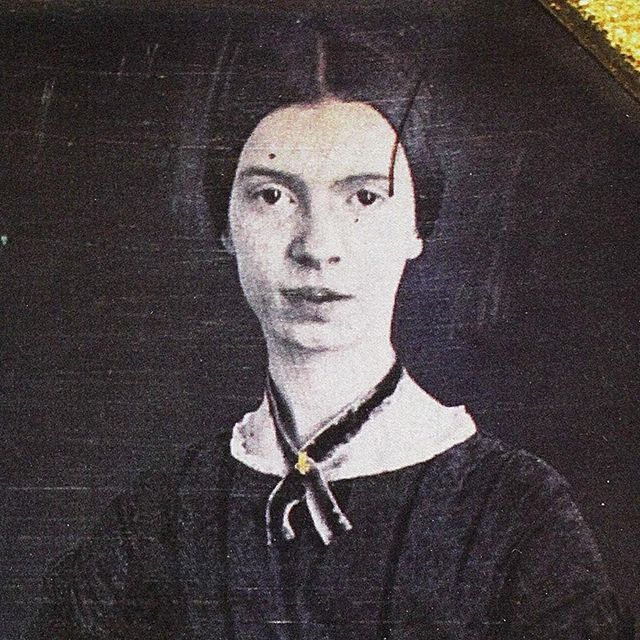

Emily Dickinson

(1830-1886)

Who Was Emily Dickinson?

Emily Dickinson left school as a teenager, eventually living a reclusive life on the family homestead. There, she secretly created bundles of poetry and wrote hundreds of letters. Due to a discovery by sister Lavinia, Dickinson's remarkable work was published after her death — on May 15, 1886, in Amherst — and she is now considered one of the towering figures of American literature.

Early Life and Education

Dickinson was born on December 10, 1830, in Amherst, Massachusetts. Her family had deep roots in New England. Her paternal grandfather, Samuel Dickinson, was well known as the founder of Amherst College. Her father worked at Amherst and served as a state legislator. He married Emily Norcross in 1828 and the couple had three children: William Austin, Emily and Lavinia Norcross.

An excellent student, Dickinson was educated at Amherst Academy (now Amherst College) for seven years and then attended Mount Holyoke Female Seminary for a year. Though the precise reasons for Dickinson's final departure from the academy in 1848 are unknown; theories offered say that her fragile emotional state may have played a role and/or that her father decided to pull her from the school. Dickinson ultimately never joined a particular church or denomination, steadfastly going against the religious norms of the time.

Family Dynamics and Writing

Among her peers, Dickinson's closest friend and adviser was a woman named Susan Gilbert, who may have been an amorous interest of Dickinson's as well. In 1856, Gilbert married Dickinson's brother, William. The Dickinson family lived on a large home known as the Homestead in Amherst. After their marriage, William and Susan settled in a property next to the Homestead known as the Evergreens. Emily and sister Lavinia served as chief caregivers for their ailing mother until she passed away in 1882. Neither Emily nor her sister ever married and lived together at the Homestead until their respective deaths.

Dickinson's seclusion during her later years has been the object of much speculation. Scholars have thought that she suffered from conditions such as agoraphobia, depression and/or anxiety, or may have been sequestered due to her responsibilities as guardian of her sick mother. Dickinson was also treated for a painful ailment of her eyes. After the mid-1860s, she rarely left the confines of the Homestead. It was also around this time, from the late 1850s to mid-'60s, that Dickinson was most productive as a poet, creating small bundles of verse known as fascicles without any awareness on the part of her family members.

In her spare time, Dickinson studied botany and produced a vast herbarium. She also maintained correspondence with a variety of contacts. One of her friendships, with Judge Otis Phillips Lord, seems to have developed into a romance before Lord's death in 1884.

Death and Discovery

Dickinson died of heart failure in Amherst, Massachusetts, on May 15, 1886, at the age of 55. She was laid to rest in her family plot at West Cemetery. The Homestead, where Dickinson was born, is now a museum .

Little of Dickinson's work was published at the time of her death, and the few works that were published were edited and altered to adhere to conventional standards of the time. Unfortunately, much of the power of Dickinson's unusual use of syntax and form was lost in the alteration. After her sister's death, Lavinia discovered hundreds of poems that Dickinson had crafted over the years. The first volume of these works was published in 1890. A full compilation, The Poems of Emily Dickinson , wasn't published until 1955, though previous iterations had been released.

Dickinson's stature as a writer soared from the first publication of her poems in their intended form. She is known for her poignant and compressed verse, which profoundly influenced the direction of 20th-century poetry. The strength of her literary voice, as well as her reclusive and eccentric life, contributes to the sense of Dickinson as an indelible American character who continues to be discussed today.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Emily Dickinson

- Birth Year: 1830

- Birth date: December 10, 1830

- Birth State: Massachusetts

- Birth City: Amherst

- Birth Country: United States

- Gender: Female

- Best Known For: Emily Dickinson was a reclusive American poet. Unrecognized in her own time, Dickinson is known posthumously for her innovative use of form and syntax.

- Fiction and Poetry

- Writing and Publishing

- Astrological Sign: Sagittarius

- Mount Holyoke Female Seminary

- Amherst Academy (now Amherst College)

- Interesting Facts

- In addition to writing poetry, Emily Dickinson studied botany. She compiled a vast herbarium that is now owned by Harvard University.

- Death Year: 1886

- Death date: May 15, 1886

- Death State: Massachusetts

- Death City: Amherst

- Death Country: United States

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Emily Dickinson Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/authors-writers/emily-dickinson

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: May 7, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

- 'Hope' is the thing with feathers - That perches in the soul - And sings the tunes without the words - And never stops - at all -

- Dwell in possibility.

- The Truth must dazzle gradually/Or every man be blind.

- Truth is so rare, it is delightful to tell it.

- If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can warm me I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only way I know it. Is there any other way?

- Success is counted sweetest/By those who ne'er succeed./To comprehend a nectar/Requires sorest need.

Watch Next .css-smpm16:after{background-color:#323232;color:#fff;margin-left:1.8rem;margin-top:1.25rem;width:1.5rem;height:0.063rem;content:'';display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;}

William Shakespeare

How Did Shakespeare Die?

Christine de Pisan

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

14 Hispanic Women Who Have Made History

10 Famous Langston Hughes Poems

5 Crowning Achievements of Maya Angelou

Amanda Gorman

Langston Hughes

7 Facts About Literary Icon Langston Hughes

Maya Angelou

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Early years

Development as a poet.

- Mature career

Why is Emily Dickinson important?

What was emily dickinson’s education, what did emily dickinson write.

- When did American literature begin?

- Who are some important authors of American literature?

Emily Dickinson

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Literary Devices - Emily Dickinson

- Emily Dickinson Museum - Biography of Emily Dickinson

- Humanities Texas - Emily Dickinson (1830–1886)

- All Poetry - Biography of Emily Dickinson

- Virginia Commonwealth University - Biography of Emily Dickinson (1830-1886)

- American National Biography - Biography of Emily Dickinson

- Brooklyn Museum - Emily Dickinson

- Poetry Foundation - Biography of Emily Dickinson

- The Academy of American Poets - Biography of Emily Dickinson

- Emily Dickinson - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Emily Dickinson - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

Emily Dickinson is considered one of the leading 19th-century American poets, known for her bold original verse, which stands out for its epigrammatic compression, haunting personal voice, and enigmatic brilliance. Yet it was only well into the 20th century that other leading writers—including Hart Crane, Allen Tate, and Elizabeth Bishop—registered her greatness.

Emily Dickinson attended Amherst Academy in her Massachusetts hometown. She showed prodigious talent in composition and excelled in Latin and the sciences. A botany class inspired her to assemble an herbarium containing many pressed plants identified in Latin. She went on to what is now Mount Holyoke College but, disliking it, left after a year.

Emily Dickinson wrote nearly 1,800 poems. Though few were published in her lifetime, she sent hundreds to friends, relatives, and others—often with, or as part of, letters. She also made clean copies of her poems on fine stationery and then sewed small bundles of these sheets together, creating 40 booklets, perhaps for posthumous publication.

Emily Dickinson (born December 10, 1830, Amherst , Massachusetts , U.S.—died May 15, 1886, Amherst) was an American lyric poet who lived in seclusion and commanded a singular brilliance of style and integrity of vision. With Walt Whitman , Dickinson is widely considered to be one of the two leading 19th-century American poets.

Only 10 of Emily Dickinson’s nearly 1,800 poems are known to have been published in her lifetime. Devoted to private pursuits, she sent hundreds of poems to friends and correspondents while apparently keeping the greater number to herself. She habitually worked in verse forms suggestive of hymns and ballads , with lines of three or four stresses. Her unusual off-rhymes have been seen as both experimental and influenced by the 18th-century hymnist Isaac Watts . She freely ignored the usual rules of versification and even of grammar, and in the intellectual content of her work she likewise proved exceptionally bold and original. Her verse is distinguished by its epigrammatic compression, haunting personal voice, enigmatic brilliance, and lack of high polish.

The second of three children, Dickinson grew up in moderate privilege and with strong local and religious attachments. For her first nine years she resided in a mansion built by her paternal grandfather, Samuel Fowler Dickinson, who had helped found Amherst College but then went bankrupt shortly before her birth. Her father, Edward Dickinson, was a forceful and prosperous Whig lawyer who served as treasurer of the college and was elected to one term in Congress. Her mother, Emily Norcross Dickinson, from the leading family in nearby Monson, was an introverted wife and hardworking housekeeper; her letters seem equally inexpressive and quirky. Both parents were loving but austere , and Emily became closely attached to her brother, Austin, and sister, Lavinia. Never marrying, the two sisters remained at home, and when their brother married, he and his wife established their own household next door. The highly distinct and even eccentric personalities developed by the three siblings seem to have mandated strict limits to their intimacy. “If we had come up for the first time from two wells,” Emily once said of Lavinia, “her astonishment would not be greater at some things I say.” Only after the poet’s death did Lavinia and Austin realize how dedicated she was to her art.

As a girl, Emily was seen as frail by her parents and others and was often kept home from school. She attended the coeducational Amherst Academy, where she was recognized by teachers and students alike for her prodigious abilities in composition . She also excelled in other subjects emphasized by the school, most notably Latin and the sciences. A class in botany inspired her to assemble an herbarium containing a large number of pressed plants identified by their Latin names. She was fond of her teachers, but when she left home to attend Mount Holyoke Female Seminary (now Mount Holyoke College ) in nearby South Hadley , she found the school’s institutional tone uncongenial. Mount Holyoke’s strict rules and invasive religious practices, along with her own homesickness and growing rebelliousness, help explain why she did not return for a second year.

At home as well as at school and church, the religious faith that ruled the poet’s early years was evangelical Calvinism , a faith centred on the belief that humans are born totally depraved and can be saved only if they undergo a life-altering conversion in which they accept the vicarious sacrifice of Jesus Christ . Questioning this tradition soon after leaving Mount Holyoke, Dickinson was to be the only member of her family who did not experience conversion or join Amherst’s First Congregational Church. Yet she seems to have retained a belief in the soul’s immortality or at least to have transmuted it into a Romantic quest for the transcendent and absolute. One reason her mature religious views elude specification is that she took no interest in creedal or doctrinal definition. In this she was influenced by both the Transcendentalism of Ralph Waldo Emerson and the mid-century tendencies of liberal Protestant orthodoxy. These influences pushed her toward a more symbolic understanding of religious truth and helped shape her vocation as poet.

Although Dickinson had begun composing verse by her late teens, few of her early poems are extant . Among them are two of the burlesque “Valentines”—the exuberantly inventive expressions of affection and esteem she sent to friends of her youth. Two other poems dating from the first half of the 1850s draw a contrast between the world as it is and a more peaceful alternative , variously eternity or a serene imaginative order. All her known juvenilia were sent to friends and engage in a striking play of visionary fancies, a direction in which she was encouraged by the popular, sentimental book of essays Reveries of a Bachelor: Or a Book of the Heart by Ik. Marvel (the pseudonym of Donald Grant Mitchell ). Dickinson’s acts of fancy and reverie, however, were more intricately social than those of Marvel’s bachelor, uniting the pleasures of solitary mental play, performance for an audience, and intimate communion with another. It may be because her writing began with a strong social impetus that her later solitude did not lead to a meaningless hermeticism.

Until Dickinson was in her mid-20s, her writing mostly took the form of letters, and a surprising number of those that she wrote from age 11 onward have been preserved. Sent to her brother, Austin, or to friends of her own sex, especially Abiah Root, Jane Humphrey, and Susan Gilbert (who would marry Austin), these generous communications overflow with humour, anecdote , invention, and sombre reflection. In general, Dickinson seems to have given and demanded more from her correspondents than she received. On occasion she interpreted her correspondents’ laxity in replying as evidence of neglect or even betrayal. Indeed, the loss of friends, whether through death or cooling interest, became a basic pattern for Dickinson. Much of her writing, both poetic and epistolary, seems premised on a feeling of abandonment and a matching effort to deny, overcome, or reflect on a sense of solitude.

Dickinson’s closest friendships usually had a literary flavour. She was introduced to the poetry of Ralph Waldo Emerson by one of her father’s law students, Benjamin F. Newton, and to that of Elizabeth Barrett Browning by Susan Gilbert and Henry Vaughan Emmons, a gifted college student. Two of Barrett Browning’s works, “ A Vision of Poets,” describing the pantheon of poets, and Aurora Leigh , on the development of a female poet, seem to have played a formative role for Dickinson, validating the idea of female greatness and stimulating her ambition. Though she also corresponded with Josiah G. Holland, a popular writer of the time, he counted for less with her than his appealing wife, Elizabeth, a lifelong friend and the recipient of many affectionate letters.

In 1855 Dickinson traveled to Washington, D.C. , with her sister and father, who was then ending his term as U.S. representative. On the return trip the sisters made an extended stay in Philadelphia , where it is thought the poet heard the preaching of Charles Wadsworth, a fascinating Presbyterian minister whose pulpit oratory suggested (as a colleague put it) “years of conflict and agony.” Seventy years later, Martha Dickinson Bianchi, the poet’s niece, claimed that Emily had fallen in love with Wadsworth, who was married, and then grandly renounced him. The story is too highly coloured for its details to be credited; certainly, there is no evidence the minister returned the poet’s love. Yet it is true that a correspondence arose between the two and that Wadsworth visited her in Amherst about 1860 and again in 1880. After his death in 1882, Dickinson remembered him as “my Philadelphia,” “my dearest earthly friend,” and “my Shepherd from ‘Little Girl’hood.”

Always fastidious , Dickinson began to restrict her social activity in her early 20s, staying home from communal functions and cultivating intense epistolary relationships with a reduced number of correspondents. In 1855, leaving the large and much-loved house (since razed) in which she had lived for 15 years, the 25-year-old woman and her family moved back to the dwelling associated with her first decade: the Dickinson mansion on Main Street in Amherst. Her home for the rest of her life, this large brick house, still standing, has become a favourite destination for her admirers. She found the return profoundly disturbing, and when her mother became incapacitated by a mysterious illness that lasted from 1855 to 1859, both daughters were compelled to give more of themselves to domestic pursuits. Various events outside the home—a bitter Norcross family lawsuit, the financial collapse of the local railroad that had been promoted by the poet’s father, and a powerful religious revival that renewed the pressure to “convert”—made the years 1857 and 1858 deeply troubling for Dickinson and promoted her further withdrawal.

Biography of Emily Dickinson, American Poet

Famously reclusive and experimental in poetic form

Culture Club / Getty Images

- Favorite Poems & Poets

- Poetic Forms

- Best Sellers

- Classic Literature

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/ThoughtCo_Amanda_Prahl_webOG-48e27b9254914b25a6c16c65da71a460.jpg)

- M.F.A, Dramatic Writing, Arizona State University

- B.A., English Literature, Arizona State University

- B.A., Political Science, Arizona State University

Emily Dickinson (December 10, 1830–May 15, 1886) was an American poet best known for her eccentric personality and her frequent themes of death and mortality. Although she was a prolific writer, only a few of her poems were published during her lifetime. Despite being mostly unknown while she was alive, her poetry—nearly 1,800 poems altogether—has become a staple of the American literary canon, and scholars and readers alike have long held a fascination with her unusual life.

Fast Facts: Emily Dickinson

- Full Name: Emily Elizabeth Dickinson

- Known For: American poet

- Born: December 10, 1830 in Amherst, Massachusetts

- Died: May 15, 1886 in Amherst, Massachusetts

- Parents: Edward Dickinson and Emily Norcross Dickinson

- Education: Amherst Academy, Mount Holyoke Female Seminary

- Published Works: Poems (1890), Poems: Second Series (1891), Poems: Third Series (1896)

- Notable Quote: "If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can ever warm me, I know that is poetry."

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson was born into a prominent family in Amherst, Massachusetts. Her father, Edward Dickinson, was a lawyer, a politician, and a trustee of Amherst College , of which his father, Samuel Dickinson, was a founder. He and his wife Emily (nee Norcross ) had three children; Emily Dickinson was the second child and eldest daughter, and she had an older brother, William Austin (who generally went by his middle name), and a younger sister, Lavinia. By all accounts, Dickinson was a pleasant, well-behaved child who particularly loved music.

Because Dickinson’s father was adamant that his children be well-educated, Dickinson received a more rigorous and more classical education than many other girls of her era. When she was ten, she and her sister began attending Amherst Academy, a former academy for boys that had just begun accepting female students two years earlier. Dickinson continued to excel at her studies, despite their rigorous and challenging nature, and studied literature, the sciences, history, philosophy, and Latin. Occasionally, she did have to take time off from school due to repeated illnesses.

Dickinson’s preoccupation with death began at this young age as well. At the age of fourteen, she suffered her first major loss when her friend and cousin Sophia Holland died of typhus . Holland’s death sent her into such a melancholy spiral that she was sent away to Boston to recover. Upon her recovery, she returned to Amherst, continuing her studies alongside some of the people who would be her lifelong friends, including her future sister-in-law Susan Huntington Gilbert.

After completing her education at Amherst Academy, Dickinson enrolled at Mount Holyoke Female Seminary. She spent less than a year there, but explanations for her early departure vary depending on the source: her family wanted her to return home, she disliked the intense, evangelical religious atmosphere, she was lonely, she didn’t like the teaching style. In any case, she returned home by the time she was 18 years old.

Reading, Loss, and Love

A family friend, a young attorney named Benjamin Franklin Newton, became a friend and mentor to Dickinson. It was most likely him who introduced her to the writings of William Wordsworth and Ralph Waldo Emerson , which later influenced and inspired her own poetry. Dickinson read extensively, helped by friends and family who brought her more books; among her most formative influences was the work of William Shakespeare , as well as Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre .

Dickinson was in good spirits in the early 1850s, but it did not last. Once again, people near to her died, and she was devastated. Her friend and mentor Newton died of tuberculosis, writing to Dickinson before he died to say he wished he could live to see her achieve greatness. Another friend, the Amherst Academy principal Leonard Humphrey, died suddenly at only 25 years old in 1850. Her letters and writings at the time are filled with the depth of her melancholy moods.

During this time, Dickinson’s old friend Susan Gilbert was her closest confidante. Beginning in 1852, Gilbert was courted by Dickinson’s brother Austin, and they married in 1856, although it was a generally unhappy marriage. Gilbert was much closer to Dickinson, with whom she shared a passionate and intense correspondence and friendship. In the view of many contemporary scholars, the relationship between the two women was, very likely, a romantic one , and possibly the most important relationship of either of their lives. Aside from her personal role in Dickinson’s life, Gilbert also served as a quasi-editor and advisor to Dickinson during her writing career.

Dickinson did not travel much outside of Amherst, slowly developing the later reputation for being reclusive and eccentric. She cared for her mother, who was essentially homebound with chronic illnesses from the 1850s onward. As she became more and more cut off from the outside world, however, Dickinson leaned more into her inner world and thus into her creative output.

Conventional Poetry (1850s – 1861)

I'm nobody who are you (1891).

I'm Nobody! Who are you? Are you — Nobody — too? Then there's a pair of us! Don't tell! they'd advertise — you know. How dreary — to be — Somebody! How public — like a Frog — To tell one's name — the livelong June — To an admiring Bog!

It’s unclear when, exactly, Dickinson began writing her poems, though it can be assumed that she was writing for some time before any of them were ever revealed to the public or published. Thomas H. Johnson, who was behind the collection The Poems of Emily Dickinson , was able to definitely date only five of Dickinson's poems to the period before 1858. In that early period, her poetry was marked by an adherence to the conventions of the time.

Two of her five earliest poems are actually satirical, done in the style of witty, “mock” valentine poems with deliberately flowery and overwrought language. Two more of them reflect the more melancholy tone she would be better known for. One of those is about her brother Austin and how much she missed him, while the other, known by its first line “I have a Bird in spring,” was written for Gilbert and was a lament about the grief of fearing the loss of friendship.

A few of Dickinson’s poems were published in the Springfield Republican between 1858 and 1868; she was friends with its editor, journalist Samuel Bowles, and his wife Mary. All of those poems were published anonymously, and they were heavily edited, removing much of Dickinson’s signature stylization, syntax, and punctuation. The first poem published, "Nobody knows this little rose,” may have actually been published without Dickinson’s permission. Another poem, “Safe in their Alabaster Chambers,” was retitled and published as “The Sleeping.” By 1858, Dickinson had begun organizing her poems, even as she wrote more of them. She reviewed and made fresh copies of her poetry, putting together manuscript books. Between 1858 and 1865, she produced 40 manuscripts, comprising just under 800 poems.

During this time period, Dickinson also drafted a trio of letters which were later referred to as the “Master Letters.” They were never sent and were discovered as drafts among her papers. Addressed to an unknown man she only calls “Master,” they’re poetic in a strange way that has eluded understanding even by the most educated of scholars. They may not have even been intended for a real person at all; they remain one of the major mysteries of Dickinson’s life and writings.

Prolific Poet (1861 – 1865)

“hope” is the thing with feathers (1891).

"Hope" is the thing with feathers That perches in the soul And sings the tune without the words And never stops at all And sweetest in the Gale is heard And sore must be the storm — That could abash the little Bird That kept so many warm — I've heard it in the chillest land — And on the strangest Sea — Yet, never, in Extremity, It asked a crumb — of Me.

Dickinson’s early 30s were by far the most prolific writing period of her life. For the most part, she withdrew almost completely from society and from interactions with locals and neighbors (though she still wrote many letters), and at the same time, she began writing more and more.

Her poems from this period were, eventually, the gold standard for her creative work. She developed her unique style of writing, with unusual and specific syntax , line breaks, and punctuation. It was during this time that the themes of mortality that she was best known for began to appear in her poems more often. While her earlier works had occasionally touched on themes of grief, fear, or loss, it wasn’t until this most prolific era that she fully leaned into the themes that would define her work and her legacy.

It is estimated that Dickinson wrote more than 700 poems between 1861 and 1865. She also corresponded with literary critic Thomas Wentworth Higginson, who became one of her close friends and lifelong correspondents. Dickinson’s writing from the time seemed to embrace a little bit of melodrama, alongside deeply felt and genuine sentiments and observations.

Later work (1866 – 1870s)

Because i could not stop for death (1890).

Because I could not stop for Death— He kindly stopped for me— The Carriage held but just Ourselves— And Immortality. We slowly drove—He knew no haste, And I had put away My labor and my leisure too, For His Civility— We passed the School, where Children strove At recess—in the ring— We passed the Fields of Gazing Grain— We passed the Setting Sun— Or rather—He passed Us— The Dews drew quivering and chill— For only Gossamer, my Gown— My Tippet—only Tulle— We paused before a House that seemed A Swelling of the Ground— The Roof was scarcely visible— The Cornice—in the Ground— Since then—'tis centuries— and yet Feels shorter than the Day I first surmised the Horses' Heads Were toward Eternity—

By 1866, Dickinson’s productivity began tapering off. She had suffered personal losses, including that of her beloved dog Carlo, and her trusted household servant got married and left her household in 1866. Most estimates suggest that she wrote about one third of her body of work after 1866.

Around 1867, Dickinson’s reclusive tendencies became more and more extreme. She began refusing to see visitors, only speaking to them from the other side of a door, and rarely went out in public. On the rare occasions she did leave the house, she always wore white, gaining notoriety as “the woman in white.” Despite this avoidance of physical socialization, Dickinson was a lively correspondent; around two-thirds of her surviving correspondence was written between 1866 and her death, 20 years later.

Dickinson’s personal life during this time was complicated as well. She lost her father to a stroke in 1874, but she refused to come out of her self-imposed seclusion for his memorial or funeral services. She also may have briefly had a romantic correspondence with Otis Phillips Lord, a judge and a widower who was a longtime friend. Very little of their correspondence survives, but what does survive shows that they wrote to each other like clockwork, every Sunday, and their letters were full of literary references and quotations. Lord died in 1884, two years after Dickinson’s old mentor, Charles Wadsworth, had died after a long illness.

Literary Style and Themes

Even a cursory glance at Dickinson’s poetry reveals some of the hallmarks of her style. Dickinson embraced highly unconventional use of punctuation , capitalization, and line breaks, which she insisted were crucial to the meaning of the poems. When her early poems were edited for publication, she was seriously displeased, arguing the edits to the stylization had altered the whole meaning. Her use of meter is also somewhat unconventional, as she avoids the popular pentameter for tetrameter or trimeter, and even then is irregular in her use of meter within a poem. In other ways, however, her poems stuck to some conventions; she often used ballad stanza forms and ABCB rhyme schemes.

The themes of Dickinson’s poetry vary widely. She’s perhaps most well known for her preoccupation with mortality and death, as exemplified in one of her most famous poems, “Because I did not stop for Death.” In some cases, this also stretched to her heavily Christian themes, with poems tied into the Christian Gospels and the life of Jesus Christ. Although her poems dealing with death are sometimes quite spiritual in nature, she also has a surprisingly colorful array of descriptions of death by various, sometimes violent means.

On the other hand, Dickinson’s poetry often embraces humor and even satire and irony to make her point; she’s not the dreary figure she is often portrayed as because of her more morbid themes. Many of her poems use garden and floral imagery, reflecting her lifelong passion for meticulous gardening and often using the “ language of flowers ” to symbolize themes such as youth, prudence, or even poetry itself. The images of nature also occasionally showed up as living creatures, as in her famous poem “ Hope is the thing with feathers .”

Dickinson reportedly kept writing until nearly the end of her life, but her lack of energy showed through when she no longer edited or organized her poems. Her family life became more complicated as her brother’s marriage to her beloved Susan fell apart and Austin instead turned to a mistress, Mabel Loomis Todd, who Dickinson never met. Her mother died in 1882, and her favorite nephew in 1883.

Through 1885, her health declined, and her family grew more concerned. Dickinson became extremely ill in May of 1886 and died on May 15, 1886. Her doctor declared the cause of death to be Bright’s disease, a disease of the kidneys . Susan Gilbert was asked to prepare her body for burial and to write her obituary, which she did with great care. Dickinson was buried in her family’s plot at West Cemetery in Amherst.

The great irony of Dickinson’s life is that she was largely unknown during her lifetime. In fact, she was probably better known as a talented gardener than as a poet. Fewer than a dozen of her poems were actually published for public consumption when she was alive. It wasn’t until after her death, when her sister Lavinia discovered her manuscripts of over 1,800 poems, that her work was published in bulk. Since that first publication, in 1890, Dickinson’s poetry has never been out of print.

At first, the non-traditional style of her poetry led to her posthumous publications getting somewhat mixed receptions. At the time, her experimentation with style and form led to criticism over her skill and education, but decades later, those same qualities were praised as signifying her creativity and daring. In the 20th century, there was a resurgence of interest and scholarship in Dickinson, particularly with regards to studying her as a female poet , not separating her gender from her work as earlier critics and scholars had.

While her eccentric nature and choice of a secluded life has occupied much of Dickinson’s image in popular culture, she is still regarded as a highly respected and highly influential American poet. Her work is consistently taught in high schools and colleges, is never out of print, and has served as the inspiration for countless artists, both in poetry and in other media. Feminist artists in particular have often found inspiration in Dickinson; both her life and her impressive body of work have provided inspiration to countless creative works.

- Habegger, Alfred. My Wars Are Laid Away in Books: The Life of Emily Dickinson . New York: Random House, 2001.

- Johnson, Thomas H. (ed.). The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson . Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1960.

- Sewall, Richard B. The Life of Emily Dickinson . New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1974.

- Wolff, Cynthia Griffin. Emily Dickinson . New York. Alfred A. Knopf, 1986.

- Dickinson's 'The Wind Tapped Like a Tired Man'

- Emily Dickinson's Mother, Emily Norcross

- Best-Loved American Women Poets

- Emily Dickinson's 'If I Can Stop One Heart From Breaking'

- Biography of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Poet and Activist

- Biography of Emily Brontë, English Novelist

- Emily Dickinson Quotes

- Biography of Sylvia Plath, American Poet and Writer

- Poems to Read on Thanksgiving Day

- 42 Must-Read Feminist Female Authors

- Phillis Wheatley

- Biography of Gabriela Mistral, Chilean Poet and Nobel Prize Winner

- Early Black American Poets

- Women Poets in History

- Biography of Hilda Doolittle, Poet, Translator, and Memoirist

- Poem Guides

- Poem of the Day

- Collections

- Harriet Books

- Featured Blogger

- Articles Home

- All Articles

- Podcasts Home

- All Podcasts

- Glossary of Poetic Terms

- Poetry Out Loud

- Upcoming Events

- All Past Events

- Exhibitions

- Poetry Magazine Home

- Current Issue

- Poetry Magazine Archive

- Subscriptions

- About the Magazine

- How to Submit

- Advertise with Us

- About Us Home

- Foundation News

- Awards & Grants

- Media Partnerships

- Press Releases

- Newsletters

Emily Dickinson 101

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Print this page

- Email this page

Emily Dickinson published very few poems in her lifetime, and nearly 1,800 of her poems were discovered after her death, many of them neatly organized into small, hand-sewn booklets called fascicles. The first published book of Dickinson’s poetry appeared in 1890, four years after her death; it was a small selection, heavily edited to remove Dickinson’s unique syntax, spelling, and punctuation. A family feud led to dueling and competing volumes in subsequent years, and a complete, restored edition of Dickinson’s poetry did not appear until 1998, more than 100 years after the original publication.

Despite their complicated history, Dickinson’s poems are among the most read and beloved in the English language. Although Dickinson is often said to have been introverted and reclusive, her poems show both her internal struggles and her strong engagement with the natural and social worlds in which she lived. School and Its Influence A daughter of a lawyer-politician father and a highly educated mother, Dickinson enjoyed a childhood of learning and socializing. Between making frequent visits and house calls, she attended Amherst Academy, a school affiliated with Amherst College that opened to female students only two years prior to her arrival. There she engaged in a science-heavy curriculum that included the study of botany, an interest that continued throughout her life. She began to collect flowers and keep them in a herbarium, which grew to 66 pages and 424 species.

This education would have a strong impact on her poetry. Planets and nature make frequent appearances in Dickinson’s poems, such as the night-blooming jessamines in “Come slowly – Eden! (205)” . In “‘Arcturus’ is his other name – (117)”, Dickinson, referring to the brightest star in the Northern Hemisphere, writes, “I’d rather call him “Star”! / It’s very mean of Science / to go and interfere!” Other often-visited topics include medicine— “Surgeons must be very careful (156)” —and science. In “’Faith’ is fine invention (202)” , she declares, “‘Faith’ is a fine invention / For Gentlemen who see! /But Microscopes are prudent / In an Emergency!”

Dickinson was also a passionate reader of contemporary poetry and prose from both the United States and England. Her library included books by Longfellow, Thoreau, Hawthorne, and Emerson as well as the Romantic poets, George Eliot, the Brontë sisters, and the Brownings. The Brontës in particular had a profound effect. “All overgrown by cunning moss, (146)” was written to commemorate the death of Charlotte Brontë, and Dickinson requested that a poem by Emily Brontë be read at her own funeral. Resisting Religious Fervor Dickinson’s feelings about religion increasingly stood out. Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, which she attended after Amherst Academy, organized students into three categories: those who were “established Christians,” those who “expressed hope,” and those who were “without hope.” Dickinson was among the latter. As a religious fervor swept Amherst in the years that followed, Dickinson was the only member of her family who did not become a member of the new church.

Despite her skepticism about traditional religious activities, Dickinson’s poems reveal her as a deeply spiritual person. In “ Some keep the Sabbath going to Church – (236)” , she talks of spending Sundays at home in her garden rather than at church, listening to the religious beauty of nature: “God preaches, a noted Clergyman – / And the sermon is never long”. The poem “I dwell in Possibility – (466)” is rich with religious language and imagery, as Dickinson writes of having “… for an everlasting Roof / The Gambrels of the Sky –” and “The spreading wide my narrow Hands / To gather Paradise –”. Many of her poems borrow the same syllabic form of Christian church hymns, creating a kind of alternative (and sometimes satirical) take on traditions and offering ways to worship not necessarily the divine but the world around us.

Poetry, Fame, and Publication Though it’s true that Dickinson was almost completely unknown as a poet during her life, the popular notion of Emily Dickinson as an extremely solitary writer is not necessarily correct. Only a few of her poems were published during her lifetime—although anonymously, heavily edited, and often without her knowledge. But Dickinson had a social life and shared her work in letters with many friends, editors, and mentors.

In response to “Letter to a Young Contributor,” an article that appeared in the Atlantic Monthly in 1862, Dickinson sent a selection of poems to its author, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, along with a letter asking, “Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?” The two went on to have a long friendship via correspondence, but his initial response was not positive. There is debate about Dickinson’s intentions toward publishing, and some see this rejection as a major disappointment that led to a more hostile viewpoint. Indeed, the poem “Publication – is the Auction (788)” is highly critical of the industry and calls to “… reduce no Human Spirit / To Disgrace of Price –”.

Fame, which comes only through publication, was frequently on her mind. There are several poems on the topic, including “Fame is the one that does not stay — (1507)” , “Fame is a fickle food (1702)” , and the succinct “ Fame is a bee. (1788)” : “Fame is a bee. / It has a song— / It has a sting— / Ah, too, it has a wing.”

Of the virtue of poetry, however, there was no doubt. In “There is no Frigate like a Book (1286)” , poetry is a means of escape and a vessel “That bears the Human Soul –”. Poets might die like anyone else, but as Dickinson explains in “The Poets light but Lamps — (930)” , their poetry, “If vital Light // Inhere as do the Suns —”. Inescapable Death From an early age, Dickinson encountered the death of friends, mentors, and family members with staggering regularity. It’s not surprising, then, that many of her most well-known poems dwell on mortality. From perhaps her most famous poem, “Because I could not stop for Death – (479)” , to a later, lesser-known poem such as “A not admitting of the wound (1188)” , Dickinson’s artistic approach ranged from the philosophical to the deeply personal. These poems also illustrate her evolving style, from the more ornate, lyrical language of the former to the more direct, personal language of the latter. A Lasting Presence Dickinson’s work continues to inspire new generations of poets and artists. Though it would be odd to mimic Dickinson’s unique language and punctuation, many poets have been deeply influenced by certain aspects of Dickinson’s style, such as her precise perception and attention to emotional details. Some notable names include Elizabeth Bishop , Sylvia Plath , Gwendolyn Brooks , Pam Rehm , Richard Brautigan , Jorie Graham , and bell hooks . Among the books inspired by Dickinson’s life and work, Susan Howe’s My Emily Dickinson stands out as a defining hybrid of poetry and criticism. More recently, Rebecca Hazelton took first lines from Dickinson poems and used them as acrostics in her book Fair Copy . Artists such as Jen Bervin have translated the unusual composition methods evident in Dickinson’s poems and letters into stunning visual works—in Bervin’s case, embroidery based on the punctuation and variant markings.

A Note about Poetry Foundation Dickinson Texts We are often asked about Dickinson’s style. Did she really spell upon as opon and use its where correct grammar calls for it’s and vice versa? The answer is yes. There are also many competing versions of Dickinson poems, either products of multiple drafts or from the odd and differing practices in which the poems have been edited over the past 110 years. Early publishers of Dickinson radically altered her words and punctuation, often added titles, and even “improved” rhymes where half rhymes were intentional, in an attempt to bring “clarity” to her poetry. It’s unfortunate that one of our most important and unconventional poets was rendered more “proper” than she ever wanted to be.

We have decided to use the versions of Dickinson’s poems that were included in R.W. Franklin’s critical edition The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Reading Edition (published by Harvard University Press). Franklin’s edition provides the best restoration of Dickinson’s poems as she originally wrote them in manuscript and letter form. That partly explains our approach to titling the poems by including the first line and its corresponding number (or order) in Franklin’s edition.

The editorial staff of the Poetry Foundation. See the Poetry Foundation staff list and editorial team masthead.

Emily Dickinson

Eternity only will answer.

- See All Related Content

Emily Dickinson is one of America’s greatest and most original poets of all time. She took definition as her province and challenged the existing definitions of poetry and the poet’s work....

Funny, convivial, chatty—a new edition of Emily Dickinson's letters upends the myth of her reclusive genius.

i think that Emily Dickinson was an amazing poet and that it is a shame that she din't live to see her works be shown to the world.

- Audio Poems

- Audio Poem of the Day

- Twitter Find us on Twitter

- Facebook Find us on Facebook

- Instagram Find us on Instagram

- Facebook Find us on Facebook Poetry Foundation Children

- Twitter Find us on Twitter Poetry Magazine

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Poetry Mobile App

- 61 West Superior Street, Chicago, IL 60654

- © 2024 Poetry Foundation

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Reading Emily Dickinson's letters : critical essays

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

Download options.

No suitable files to display here.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station34.cebu on July 1, 2023

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Emily Dickinson’s Love Life

“wild nights – wild nights were i with thee wild nights should be our luxury” – from fr269.

E mily Dickinson never married, but because her canon includes magnificent love poems, questions concerning her love life have intrigued readers since her first publication in the 1890s. Speculation about whom she may have loved has filled and continues to fill volumes. Her girlhood relationships, her “Master Letters,” and her correspondence with Judge Otis Lord form the backbone of these discussions.

A draft of a letter from Emily to the mysterious “Master”

Dickinson’s school days and young adulthood included several significant male friends, among them Benjamin Newton, a law student in her father’s office; Henry Vaughn Emmons, an Amherst College student; and George Gould, an Amherst College classmate of the poet’s brother Austin. Early Dickinson biographers identified Gould as a suitor who may have been briefly engaged to the poet in the 1850s, and recent scholarship has shed new light on the theory (Andrews, pp. 334-335). Her female friendships, notably with schoolmate and later sister-in-law Susan Huntington Gilbert and with mutual friend Catherine Scott Turner Anthon, have also interested Dickinson biographers, who argue whether these friendships represent typical nineteenth-century girlhood friendships or more intensely sexual and romantic relationships.

Found among Emily Dickinson’s papers shortly after her death, drafts of three letters to an unidentified “Master” provide a source of intrigue, although there is no evidence to confirm that finished versions of the letters were ever sent. Written during the poet’s most productive period, the letters reveal passionate yet changing feelings toward the recipient. The first, dated to spring 1858, begins “Dear Master / I am ill”; the second, dated to early 1861, starts with “Oh, did I offend it”; and the third, dated to summer 1861, opens with “Master / If you saw a bullet hit a bird” (date attributions made by R.W. Franklin).

While the letters are remarkable examples of Dickinson’s exceptional power with words, they are studied as much to attempt identification of the intended recipient as for their literary mastery. The lengthy list of proposed candidates includes Samuel Bowles, family friend, newspaper editor and publisher; William Smith Clark, a scientist and educator based in Amherst; Charles Wadsworth, a minister whom Dickinson heard preach in Philadelphia; as well as George Gould and Susan Dickinson. Others have posited that the letters are simply literary exercises or that the author is attempting to resolve an internal crisis. So much about Dickinson’s life remains unknown that an entirely different or as-yet unknown candidate may yet be revealed. Unless a contemporary account is discovered that clearly identifies the “Master,” the poet’s public will remain in suspense.

Judge Otis Phillips Lord, a Dickinson love interest

A romantic relationship late in the poet’s life with Judge Otis Phillips Lord is supported in Dickinson’s correspondence with him as well as in family references. Lord (1812-1884) was a close friend of Edward Dickinson , the poet’s father, with whom he shared conservative political views. Lord and his wife Elizabeth were familiar guests in the Dickinson household. In 1859 Lord was appointed to the Massachusetts Superior Court and later served on the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts (1875-1882). His relationship with the poet developed after the death of Elizabeth Lord in 1877. Only fifteen manuscripts in Dickinson’s hand survive from their correspondence, most in draft or fragmentary form. Some passages seem to suggest that Dickinson and Lord contemplated marrying. The question of whether the reclusive poet would have consented to move to Lord’s home in Salem, Massachusetts, was mooted by Lord’s decline in health. He died in 1884, two years before Emily Dickinson.

Whatever the reality of Dickinson’s personal experiences, her poetry explores the complexities and passions of human relationships with language that is as evocative and compelling as her writings on spirituality, death, and nature.

Further Reading:

For a complete text of the Master letters, see The Master Letters of Emily Dickinson , ed.R.W. Franklin (Amherst, Mass.: Amherst College Press, 1986).

For an account of the discovery of Dickinson’s letters to Judge Lord, see Millicent Todd Bingham’s Emily Dickinson: A Revelation ( New York: Harper and Bros, 1954)

Most biographies discuss the “Master” letters and Lord relationship in some detail. Significant discussions of the Master letters include those in Richard B. Sewall’s The Life of Emily Dickinson ( New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1974); Cynthia G. Wolff’s Emily Dickinson ( New York: Knopf, 1986); and Alfred Habegger’s My Wars Are Laid Away in Books: The Life of Emily Dickinson ( New York: Random House, 2001).

In addition, several works address more directly specific individuals and their qualifications for “Master.” Among them are

- Andrews, Carol Damon. “Thinking Musically, Writing Expectantly: New Biographical Information about Emily Dickinson.” The New England Quarterly , Vol. LXXXI, no. 2 (June 2008) 330-340. Reintroduces the possibility of George Gould as the “Master” candidate.

- Jones, Ruth Owen. “’Neighbor – and friend – and Bridegroom –‘” William Smith Clark as Emily Dickinson’s Master Figure.” The Emily Dickinson Journal 11.2 (2002) 48-85.

- Mamunes, George. “So has a Daisy vanished”: Emily Dickinson and Tuberculosis. McFarland, 2007. Proposes Benjamin Franklin Newton as Master.

- Open Me Carefully: Emily Dickinson’s Intimate Letters to Susan Huntington Dickinson . Ed. Ellen Louise Hart and Martha Nell Smith. Paris Press, 1998. Addresses the poet’s relationship with Susan Dickinson.

- Patterson, Rebecca. The Riddle of Emily Dickinson . Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1951. Posits Kate Anthon as a love interest.

For Dickinson’s thoughts on marriage, Judith Farr’s “Emily Dickinson and Marriage: ‘the Etruscan Experiment'” in Reading Emily Dickinson’s Letters: Critical Essays (Amherst: U of Massachusetts P, 2009).

Loading content

Home — Essay Samples — Literature — Poetry — Emily Dickinson’s Views on Personal Identity in Her Poens

Emily Dickinson's Views on Personal Identity in Her Poens

- Categories: Emily Dickinson Poetry

About this sample

Words: 1030 |

Published: Jul 2, 2018

Words: 1030 | Pages: 2 | 6 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Literature

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

5 pages / 2134 words

1 pages / 976 words

5 pages / 2402 words

10.5 pages / 4681 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Poetry

Robert Frost's poem "Nothing Gold Can Stay" explores the themes of acceptance and the transient nature of beauty. Through the use of symbolism, Frost conveys the idea that all things must eventually come to an end, and that [...]

Carl Sandburg, a renowned American poet, wrote the powerful poem 'Grass' that explores the profound impact of war on both nature and humanity. In this essay, we will analyze the ways in which war devastates the natural [...]

Dorothy Parker's "A Certain Lady" is a poignant reflection on love, desire, and the self. Through the perspectives of the speaker and their relationship with the certain lady, Parker delves into the complexities and nuances of [...]

Poetry has a universal appeal that transcends time and space, evoking emotions and inspiring reflection. Robert Frost's "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening" is a prime example of the power of poetry to captivate and provoke [...]

In Literary Theory: The Basics, H. Bertens asserts that even in the works of culturally and sexually liberal male writers such as D.H Lawrence and Henry Miller, male characters are “denigrating, exploitative, and repressive in [...]

Anna Barbauld’s Eighteen Hundred and Eleven demonstrates Romantic-era Cosmopolitanism’s promotion of a global consciousness and transnational empathy. Cosmopolitan theory emerged as a result of Napoleon’s growing power, English [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Leaving Cert English Emily Dickinson Sample Answer: Enduring Appeal and Universal Relevance

Far from being old fashioned and irrelevant emily dickinson’s unique poetic language continues to have both an enduring appeal and universal relevance. discuss..

The poetry of Emily Dickinson is nigh irresistible. She revels in the presentation of the unusual and unexpected. It is indeed her innovative poetic language that propels her poetry form the past and into today. Dickinson’s unconventional work has an eternal appeal. Dickinson casts off the restrictions of traditional punctuation. She makes use of concrete imagery and language to convey abstract ideas, ranging from joyous hope to devastating despair. There is no doubt that Dickinson is a poet of extremes. The Belle Of Amherst has an undeniable transcendental power.

- Post author: Martina

- Post published: October 23, 2016

- Post category: Emily Dickinson / English / Poetry

You Might Also Like

Macbeth sample essay: appearance versus reality, article about myths, fairytales and legends for leaving cert english #625lab, short story in which mistaken identity is central to the plot for leaving cert english #625lab.

COMMENTS

Dickinson is now known as one of the most important American poets, and her poetry is widely read among people of all ages and interests. Emily Elizabeth Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massachusetts, on December 10, 1830 to Edward and Emily (Norcross) Dickinson. At the time of her birth, Emily's father was an ambitious young lawyer.

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson (December 10, 1830 - May 15, 1886) was an American poet. ... Her first published collection of poetry was made in 1890 by her personal acquaintances Thomas Wentworth Higginson and Mabel Loomis Todd, ... In the first collection of critical essays on Dickinson from a feminist perspective, ...

Emily Dickinson left school as a teenager, eventually living a reclusive life on the family homestead. There, she secretly created bundles of poetry and wrote hundreds of letters. Due to a ...

Emily Dickinson (born December 10, 1830, Amherst, Massachusetts, U.S.—died May 15, 1886, Amherst) was an American lyric poet who lived in seclusion and commanded a singular brilliance of style and integrity of vision. With Walt Whitman, Dickinson is widely considered to be one of the two leading 19th-century American poets.. Only 10 of Emily Dickinson's nearly 1,800 poems are known to have ...

Emily Dickinson - Emily Dickinson was born on December 10, 1830, in Amherst, Massachusetts. While she was extremely prolific as a poet and regularly enclosed poems in letters to friends, she was not publicly recognized during her lifetime. She died in Amherst in 1886, and the first volume of her work was published posthumously in 1890.

Emily Dickinson (December 10, 1830-May 15, 1886) was an American poet best known for her eccentric personality and her frequent themes of death and mortality. Although she was a prolific writer, only a few of her poems were published during her lifetime. Despite being mostly unknown while she was alive, her poetry—nearly 1,800 poems ...

Essays and criticism on Emily Dickinson, including the works Themes and form, "I like to see it lap the Miles", "It sifts from Leaden Sieves", "It was not Death, for I stood up", "I ...

Emily Dickinson, known as "The Belle of Amherst," is widely considered one of the most original American poets of the nineteenth century. She wrote hundreds of poems—most of which were not ...

Emily Dickinson 101. Demystifying one of our greatest poets. Emily Dickinson published very few poems in her lifetime, and nearly 1,800 of her poems were discovered after her death, many of them neatly organized into small, hand-sewn booklets called fascicles. The first published book of Dickinson's poetry appeared in 1890, four years after ...

In this volume, distinguished literary scholars focus intensively on Dickinson's letter-writing and what her letters reveal about her poetics, her personal associations, and her self-awareness as a writer Includes bibliographical references (p. 257-270) and indexes

Emily Dickinson's personality is a complex tapestry of introspection, independence, and nonconformity. Through her poetry, Dickinson delved deep into the recesses of her own psyche, exploring themes of faith, doubt, and the human condition. Her fierce independence and nonconformity set her apart from her contemporaries, as she forged her own ...

In the following essay, Falk interprets poem "271" as a chronicle of self-discovery in which the narrator rejects the role of bride or nun. In the first publication of Emily Dickinson's poem ...

Emily Dickinson's Love Life. "Wild nights - Wild nights! Our luxury!". E mily Dickinson never married, but because her canon includes magnificent love poems, questions concerning her love life have intrigued readers since her first publication in the 1890s. Speculation about whom she may have loved has filled and continues to fill volumes.

Student answer. Dickinson is perhaps the most unique and talented poet of nineteenth-century America. Although she is well-known for the darker aspects of her poetry, what makes Dickinson's work so memorable is her ability to strike a delicate balance between the dark and light, the tragic and the optimistic. While she diminishes neither ...

SOURCE: "Emily Dickinson's Prose," in Emily Dickinson: A Collection of Critical Essays, edited by Richard B. Sewell, Prentice Hall, 1963, pp. 162-77. [In the following essay, originally part of a ...

"The Wife" offers a strong critique of the lack of identity many women suffered during the Romantic Era. The lines "[s]he rose to his requirement, dropped / [t]he playthings of her life" is the harsh reality of what happened when women were married (Emily Dickinson, The Wife, verse 1, lines 1-2).The term "playthings" implies that anything a woman was involved in was not to be taken ...

Developing Your Personal Response: Emily Dickinson Improving Your Grade When studying Emily Dickinson's work, the student must consider the poet's themes and ... addressed in the developed essay is impressive. Dickinson's demanding style is also acknowledged as 'subtle', 'surprising' and 'intriguing'. Apt quotes and

Emily Dickinson's personal life comes through in the themes of her poetry as well as in its style. Common themes of her work include death, grief, nature, love, and introspection.

The poetry of Emily Dickinson is nigh irresistible. She revels in the presentation of the unusual and unexpected. ... Write a personal essay about one or more moments of uncertainty you have experienced #625Lab February 15, 2018 Personal essay: moments of insight and revelation for Leaving Cert English #625Lab (Divorce) September 23, 2018