Reference management. Clean and simple.

Getting started with your research paper outline

Levels of organization for a research paper outline

First level of organization, second level of organization, third level of organization, fourth level of organization, tips for writing a research paper outline, research paper outline template, my research paper outline is complete: what are the next steps, frequently asked questions about a research paper outline, related articles.

The outline is the skeleton of your research paper. Simply start by writing down your thesis and the main ideas you wish to present. This will likely change as your research progresses; therefore, do not worry about being too specific in the early stages of writing your outline.

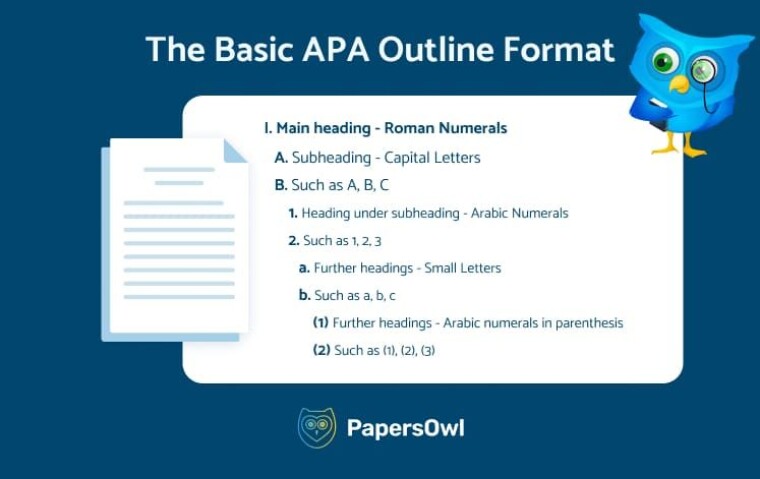

A research paper outline typically contains between two and four layers of organization. The first two layers are the most generalized. Each layer thereafter will contain the research you complete and presents more and more detailed information.

The levels are typically represented by a combination of Roman numerals, Arabic numerals, uppercase letters, lowercase letters but may include other symbols. Refer to the guidelines provided by your institution, as formatting is not universal and differs between universities, fields, and subjects. If you are writing the outline for yourself, you may choose any combination you prefer.

This is the most generalized level of information. Begin by numbering the introduction, each idea you will present, and the conclusion. The main ideas contain the bulk of your research paper 's information. Depending on your research, it may be chapters of a book for a literature review , a series of dates for a historical research paper, or the methods and results of a scientific paper.

I. Introduction

II. Main idea

III. Main idea

IV. Main idea

V. Conclusion

The second level consists of topics which support the introduction, main ideas, and the conclusion. Each main idea should have at least two supporting topics listed in the outline.

If your main idea does not have enough support, you should consider presenting another main idea in its place. This is where you should stop outlining if this is your first draft. Continue your research before adding to the next levels of organization.

- A. Background information

- B. Hypothesis or thesis

- A. Supporting topic

- B. Supporting topic

The third level of organization contains supporting information for the topics previously listed. By now, you should have completed enough research to add support for your ideas.

The Introduction and Main Ideas may contain information you discovered about the author, timeframe, or contents of a book for a literature review; the historical events leading up to the research topic for a historical research paper, or an explanation of the problem a scientific research paper intends to address.

- 1. Relevant history

- 2. Relevant history

- 1. The hypothesis or thesis clearly stated

- 1. A brief description of supporting information

- 2. A brief description of supporting information

The fourth level of organization contains the most detailed information such as quotes, references, observations, or specific data needed to support the main idea. It is not typical to have further levels of organization because the information contained here is the most specific.

- a) Quotes or references to another piece of literature

- b) Quotes or references to another piece of literature

Tip: The key to creating a useful outline is to be consistent in your headings, organization, and levels of specificity.

- Be Consistent : ensure every heading has a similar tone. State the topic or write short sentences for each heading but avoid doing both.

- Organize Information : Higher levels of organization are more generally stated and each supporting level becomes more specific. The introduction and conclusion will never be lower than the first level of organization.

- Build Support : Each main idea should have two or more supporting topics. If your research does not have enough information to support the main idea you are presenting, you should, in general, complete additional research or revise the outline.

By now, you should know the basic requirements to create an outline for your paper. With a content framework in place, you can now start writing your paper . To help you start right away, you can use one of our templates and adjust it to suit your needs.

After completing your outline, you should:

- Title your research paper . This is an iterative process and may change when you delve deeper into the topic.

- Begin writing your research paper draft . Continue researching to further build your outline and provide more information to support your hypothesis or thesis.

- Format your draft appropriately . MLA 8 and APA 7 formats have differences between their bibliography page, in-text citations, line spacing, and title.

- Finalize your citations and bibliography . Use a reference manager like Paperpile to organize and cite your research.

- Write the abstract, if required . An abstract will briefly state the information contained within the paper, results of the research, and the conclusion.

An outline is used to organize written ideas about a topic into a logical order. Outlines help us organize major topics, subtopics, and supporting details. Researchers benefit greatly from outlines while writing by addressing which topic to cover in what order.

The most basic outline format consists of: an introduction, a minimum of three topic paragraphs, and a conclusion.

You should make an outline before starting to write your research paper. This will help you organize the main ideas and arguments you want to present in your topic.

- Consistency: ensure every heading has a similar tone. State the topic or write short sentences for each heading but avoid doing both.

- Organization : Higher levels of organization are more generally stated and each supporting level becomes more specific. The introduction and conclusion will never be lower than the first level of organization.

- Support : Each main idea should have two or more supporting topics. If your research does not have enough information to support the main idea you are presenting, you should, in general, complete additional research or revise the outline.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Paper Outline – Types, Example, Template

Research Paper Outline – Types, Example, Template

Table of Contents

By creating a well-structured research paper outline, writers can easily organize their thoughts and ideas and ensure that their final paper is clear, concise, and effective. In this article, we will explore the essential components of a research paper outline and provide some tips and tricks for creating a successful one.

Research Paper Outline

Research paper outline is a plan or a structural framework that organizes the main ideas , arguments, and supporting evidence in a logical sequence. It serves as a blueprint or a roadmap for the writer to follow while drafting the actual research paper .

Typically, an outline consists of the following elements:

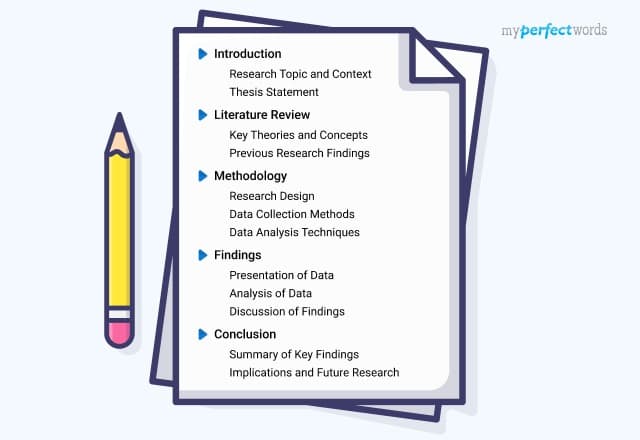

- Introduction : This section presents the topic, research question , and thesis statement of the paper. It also provides a brief overview of the literature review and the methodology used.

- Literature Review: This section provides a comprehensive review of the relevant literature, theories, and concepts related to the research topic. It analyzes the existing research and identifies the research gaps and research questions.

- Methodology: This section explains the research design, data collection methods, data analysis, and ethical considerations of the study.

- Results: This section presents the findings of the study, using tables, graphs, and statistics to illustrate the data.

- Discussion : This section interprets the results of the study, and discusses their implications, significance, and limitations. It also suggests future research directions.

- Conclusion : This section summarizes the main findings of the study and restates the thesis statement.

- References: This section lists all the sources cited in the paper using the appropriate citation style.

Research Paper Outline Types

There are several types of outlines that can be used for research papers, including:

Alphanumeric Outline

This is a traditional outline format that uses Roman numerals, capital letters, Arabic numerals, and lowercase letters to organize the main ideas and supporting details of a research paper. It is commonly used for longer, more complex research papers.

I. Introduction

- A. Background information

- B. Thesis statement

- 1 1. Supporting detail

- 1 2. Supporting detail 2

- 2 1. Supporting detail

III. Conclusion

- A. Restate thesis

- B. Summarize main points

Decimal Outline

This outline format uses numbers to organize the main ideas and supporting details of a research paper. It is similar to the alphanumeric outline, but it uses only numbers and decimals to indicate the hierarchy of the ideas.

- 1.1 Background information

- 1.2 Thesis statement

- 1 2.1.1 Supporting detail

- 1 2.1.2 Supporting detail

- 2 2.2.1 Supporting detail

- 1 2.2.2 Supporting detail

- 3.1 Restate thesis

- 3.2 Summarize main points

Full Sentence Outline

This type of outline uses complete sentences to describe the main ideas and supporting details of a research paper. It is useful for those who prefer to see the entire paper outlined in complete sentences.

- Provide background information on the topic

- State the thesis statement

- Explain main idea 1 and provide supporting details

- Discuss main idea 2 and provide supporting details

- Restate the thesis statement

- Summarize the main points of the paper

Topic Outline

This type of outline uses short phrases or words to describe the main ideas and supporting details of a research paper. It is useful for those who prefer to see a more concise overview of the paper.

- Background information

- Thesis statement

- Supporting detail 1

- Supporting detail 2

- Restate thesis

- Summarize main points

Reverse Outline

This is an outline that is created after the paper has been written. It involves going back through the paper and summarizing each paragraph or section in one sentence. This can be useful for identifying gaps in the paper or areas that need further development.

- Introduction : Provides background information and states the thesis statement.

- Paragraph 1: Discusses main idea 1 and provides supporting details.

- Paragraph 2: Discusses main idea 2 and provides supporting details.

- Paragraph 3: Addresses potential counterarguments.

- Conclusion : Restates thesis and summarizes main points.

Mind Map Outline

This type of outline involves creating a visual representation of the main ideas and supporting details of a research paper. It can be useful for those who prefer a more creative and visual approach to outlining.

- Supporting detail 1: Lack of funding for public schools.

- Supporting detail 2: Decrease in government support for education.

- Supporting detail 1: Increase in income inequality.

- Supporting detail 2: Decrease in social mobility.

Research Paper Outline Example

Research Paper Outline Example on Cyber Security:

A. Overview of Cybersecurity

- B. Importance of Cybersecurity

- C. Purpose of the paper

II. Cyber Threats

A. Definition of Cyber Threats

- B. Types of Cyber Threats

- C. Examples of Cyber Threats

III. Cybersecurity Measures

A. Prevention measures

- Anti-virus software

- Encryption B. Detection measures

- Intrusion Detection System (IDS)

- Security Information and Event Management (SIEM)

- Security Operations Center (SOC) C. Response measures

- Incident Response Plan

- Business Continuity Plan

- Disaster Recovery Plan

IV. Cybersecurity in the Business World

A. Overview of Cybersecurity in the Business World

B. Cybersecurity Risk Assessment

C. Best Practices for Cybersecurity in Business

V. Cybersecurity in Government Organizations

A. Overview of Cybersecurity in Government Organizations

C. Best Practices for Cybersecurity in Government Organizations

VI. Cybersecurity Ethics

A. Definition of Cybersecurity Ethics

B. Importance of Cybersecurity Ethics

C. Examples of Cybersecurity Ethics

VII. Future of Cybersecurity

A. Overview of the Future of Cybersecurity

B. Emerging Cybersecurity Threats

C. Advancements in Cybersecurity Technology

VIII. Conclusion

A. Summary of the paper

B. Recommendations for Cybersecurity

- C. Conclusion.

IX. References

A. List of sources cited in the paper

B. Bibliography of additional resources

Introduction

Cybersecurity refers to the protection of computer systems, networks, and sensitive data from unauthorized access, theft, damage, or any other form of cyber attack. B. Importance of Cybersecurity The increasing reliance on technology and the growing number of cyber threats make cybersecurity an essential aspect of modern society. Cybersecurity breaches can result in financial losses, reputational damage, and legal liabilities. C. Purpose of the paper This paper aims to provide an overview of cybersecurity, cyber threats, cybersecurity measures, cybersecurity in the business and government sectors, cybersecurity ethics, and the future of cybersecurity.

A cyber threat is any malicious act or event that attempts to compromise or disrupt computer systems, networks, or sensitive data. B. Types of Cyber Threats Common types of cyber threats include malware, phishing, social engineering, ransomware, DDoS attacks, and advanced persistent threats (APTs). C. Examples of Cyber Threats Recent cyber threats include the SolarWinds supply chain attack, the Colonial Pipeline ransomware attack, and the Microsoft Exchange Server hack.

Prevention measures aim to minimize the risk of cyber attacks by implementing security controls, such as firewalls, anti-virus software, and encryption.

- Firewalls Firewalls act as a barrier between a computer network and the internet, filtering incoming and outgoing traffic to prevent unauthorized access.

- Anti-virus software Anti-virus software detects, prevents, and removes malware from computer systems.

- Encryption Encryption involves the use of mathematical algorithms to transform sensitive data into a code that can only be accessed by authorized individuals. B. Detection measures Detection measures aim to identify and respond to cyber attacks as quickly as possible, such as intrusion detection systems (IDS), security information and event management (SIEM), and security operations centers (SOCs).

- Intrusion Detection System (IDS) IDS monitors network traffic for signs of unauthorized access, such as unusual patterns or anomalies.

- Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) SIEM combines security information management and security event management to provide real-time monitoring and analysis of security alerts.

- Security Operations Center (SOC) SOC is a dedicated team responsible for monitoring, analyzing, and responding to cyber threats. C. Response measures Response measures aim to mitigate the impact of a cyber attack and restore normal operations, such as incident response plans (IRPs), business continuity plans (BCPs), and disaster recovery plans (DRPs).

- Incident Response Plan IRPs outline the procedures and protocols to follow in the event of a cyber attack, including communication protocols, roles and responsibilities, and recovery processes.

- Business Continuity Plan BCPs ensure that critical business functions can continue in the event of a cyber attack or other disruption.

- Disaster Recovery Plan DRPs outline the procedures to recover from a catastrophic event, such as a natural disaster or cyber attack.

Cybersecurity is crucial for businesses of all sizes and industries, as they handle sensitive data, financial transactions, and intellectual property that are attractive targets for cyber criminals.

Risk assessment is a critical step in developing a cybersecurity strategy, which involves identifying potential threats, vulnerabilities, and consequences to determine the level of risk and prioritize security measures.

Best practices for cybersecurity in business include implementing strong passwords and multi-factor authentication, regularly updating software and hardware, training employees on cybersecurity awareness, and regularly backing up data.

Government organizations face unique cybersecurity challenges, as they handle sensitive information related to national security, defense, and critical infrastructure.

Risk assessment in government organizations involves identifying and assessing potential threats and vulnerabilities, conducting regular audits, and complying with relevant regulations and standards.

Best practices for cybersecurity in government organizations include implementing secure communication protocols, regularly updating and patching software, and conducting regular cybersecurity training and awareness programs for employees.

Cybersecurity ethics refers to the ethical considerations involved in cybersecurity, such as privacy, data protection, and the responsible use of technology.

Cybersecurity ethics are crucial for maintaining trust in technology, protecting privacy and data, and promoting responsible behavior in the digital world.

Examples of cybersecurity ethics include protecting the privacy of user data, ensuring data accuracy and integrity, and implementing fair and unbiased algorithms.

The future of cybersecurity will involve a shift towards more advanced technologies, such as artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, and quantum computing.

Emerging cybersecurity threats include AI-powered cyber attacks, the use of deepfakes and synthetic media, and the potential for quantum computing to break current encryption methods.

Advancements in cybersecurity technology include the development of AI and machine learning-based security tools, the use of blockchain for secure data storage and sharing, and the development of post-quantum encryption methods.

This paper has provided an overview of cybersecurity, cyber threats, cybersecurity measures, cybersecurity in the business and government sectors, cybersecurity ethics, and the future of cybersecurity.

To enhance cybersecurity, organizations should prioritize risk assessment and implement a comprehensive cybersecurity strategy that includes prevention, detection, and response measures. Additionally, organizations should prioritize cybersecurity ethics to promote responsible behavior in the digital world.

C. Conclusion

Cybersecurity is an essential aspect of modern society, and organizations must prioritize cybersecurity to protect sensitive data and maintain trust in technology.

for further reading

X. Appendices

A. Glossary of key terms

B. Cybersecurity checklist for organizations

C. Sample cybersecurity policy for businesses

D. Sample cybersecurity incident response plan

E. Cybersecurity training and awareness resources

Note : The content and organization of the paper may vary depending on the specific requirements of the assignment or target audience. This outline serves as a general guide for writing a research paper on cybersecurity. Do not use this in your assingmets.

Research Paper Outline Template

- Background information and context of the research topic

- Research problem and questions

- Purpose and objectives of the research

- Scope and limitations

II. Literature Review

- Overview of existing research on the topic

- Key concepts and theories related to the research problem

- Identification of gaps in the literature

- Summary of relevant studies and their findings

III. Methodology

- Research design and approach

- Data collection methods and procedures

- Data analysis techniques

- Validity and reliability considerations

- Ethical considerations

IV. Results

- Presentation of research findings

- Analysis and interpretation of data

- Explanation of significant results

- Discussion of unexpected results

V. Discussion

- Comparison of research findings with existing literature

- Implications of results for theory and practice

- Limitations and future directions for research

- Conclusion and recommendations

VI. Conclusion

- Summary of research problem, purpose, and objectives

- Discussion of significant findings

- Contribution to the field of study

- Implications for practice

- Suggestions for future research

VII. References

- List of sources cited in the research paper using appropriate citation style.

Note : This is just an template, and depending on the requirements of your assignment or the specific research topic, you may need to modify or adjust the sections or headings accordingly.

Research Paper Outline Writing Guide

Here’s a guide to help you create an effective research paper outline:

- Choose a topic : Select a topic that is interesting, relevant, and meaningful to you.

- Conduct research: Gather information on the topic from a variety of sources, such as books, articles, journals, and websites.

- Organize your ideas: Organize your ideas and information into logical groups and subgroups. This will help you to create a clear and concise outline.

- Create an outline: Begin your outline with an introduction that includes your thesis statement. Then, organize your ideas into main points and subpoints. Each main point should be supported by evidence and examples.

- Introduction: The introduction of your research paper should include the thesis statement, background information, and the purpose of the research paper.

- Body : The body of your research paper should include the main points and subpoints. Each point should be supported by evidence and examples.

- Conclusion : The conclusion of your research paper should summarize the main points and restate the thesis statement.

- Reference List: Include a reference list at the end of your research paper. Make sure to properly cite all sources used in the paper.

- Proofreading : Proofread your research paper to ensure that it is free of errors and grammatical mistakes.

- Finalizing : Finalize your research paper by reviewing the outline and making any necessary changes.

When to Write Research Paper Outline

It’s a good idea to write a research paper outline before you begin drafting your paper. The outline will help you organize your thoughts and ideas, and it can serve as a roadmap for your writing process.

Here are a few situations when you might want to consider writing an outline:

- When you’re starting a new research project: If you’re beginning a new research project, an outline can help you get organized from the very beginning. You can use your outline to brainstorm ideas, map out your research goals, and identify potential sources of information.

- When you’re struggling to organize your thoughts: If you find yourself struggling to organize your thoughts or make sense of your research, an outline can be a helpful tool. It can help you see the big picture of your project and break it down into manageable parts.

- When you’re working with a tight deadline : If you have a deadline for your research paper, an outline can help you stay on track and ensure that you cover all the necessary points. By mapping out your paper in advance, you can work more efficiently and avoid getting stuck or overwhelmed.

Purpose of Research Paper Outline

The purpose of a research paper outline is to provide a structured and organized plan for the writer to follow while conducting research and writing the paper. An outline is essentially a roadmap that guides the writer through the entire research process, from the initial research and analysis of the topic to the final writing and editing of the paper.

A well-constructed outline can help the writer to:

- Organize their thoughts and ideas on the topic, and ensure that all relevant information is included.

- Identify any gaps in their research or argument, and address them before starting to write the paper.

- Ensure that the paper follows a logical and coherent structure, with clear transitions between different sections.

- Save time and effort by providing a clear plan for the writer to follow, rather than starting from scratch and having to revise the paper multiple times.

Advantages of Research Paper Outline

Some of the key advantages of a research paper outline include:

- Helps to organize thoughts and ideas : An outline helps to organize all the different ideas and information that you want to include in your paper. By creating an outline, you can ensure that all the points you want to make are covered and in a logical order.

- Saves time and effort : An outline saves time and effort because it helps you to focus on the key points of your paper. It also helps you to identify any gaps or areas where more research may be needed.

- Makes the writing process easier : With an outline, you have a clear roadmap of what you want to write, and this makes the writing process much easier. You can simply follow your outline and fill in the details as you go.

- Improves the quality of your paper : By having a clear outline, you can ensure that all the important points are covered and in a logical order. This makes your paper more coherent and easier to read, which ultimately improves its overall quality.

- Facilitates collaboration: If you are working on a research paper with others, an outline can help to facilitate collaboration. By sharing your outline, you can ensure that everyone is on the same page and working towards the same goals.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Research Paper Title – Writing Guide and Example

Research Paper Introduction – Writing Guide and...

How Can You Create a Well Planned Research Paper Outline

You are staring at the blank document, meaning to start writing your research paper . After months of experiments and procuring results, your PI asked you to write the paper to publish it in a reputed journal. You spoke to your peers and a few seniors and received a few tips on writing a research paper, but you still can’t plan on how to begin!

Writing a research paper is a very common issue among researchers and is often looked upon as a time consuming hurdle. Researchers usually look up to this task as an impending threat, avoiding and procrastinating until they cannot delay it anymore. Seeking advice from internet and seniors they manage to write a paper which goes in for quite a few revisions. Making researchers lose their sense of understanding with respect to their research work and findings. In this article, we would like to discuss how to create a structured research paper outline which will assist a researcher in writing their research paper effectively!

Publication is an important component of research studies in a university for academic promotion and in obtaining funding to support research. However, the primary reason is to provide the data and hypotheses to scientific community to advance the understanding in a specific domain. A scientific paper is a formal record of a research process. It documents research protocols, methods, results, conclusion, and discussion from a research hypothesis .

Table of Contents

What Is a Research Paper Outline?

A research paper outline is a basic format for writing an academic research paper. It follows the IMRAD format (Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion). However, this format varies depending on the type of research manuscript. A research paper outline consists of following sections to simplify the paper for readers. These sections help researchers build an effective paper outline.

1. Title Page

The title page provides important information which helps the editors, reviewers, and readers identify the manuscript and the authors at a glance. It also provides an overview of the field of research the research paper belongs to. The title should strike a balance between precise and detailed. Other generic details include author’s given name, affiliation, keywords that will provide indexing, details of the corresponding author etc. are added to the title page.

2. Abstract

Abstract is the most important section of the manuscript and will help the researcher create a detailed research paper outline . To be more precise, an abstract is like an advertisement to the researcher’s work and it influences the editor in deciding whether to submit the manuscript to reviewers or not. Writing an abstract is a challenging task. Researchers can write an exemplary abstract by selecting the content carefully and being concise.

3. Introduction

An introduction is a background statement that provides the context and approach of the research. It describes the problem statement with the assistance of the literature study and elaborates the requirement to update the knowledge gap. It sets the research hypothesis and informs the readers about the big research question.

This section is usually named as “Materials and Methods”, “Experiments” or “Patients and Methods” depending upon the type of journal. This purpose provides complete information on methods used for the research. Researchers should mention clear description of materials and their use in the research work. If the methods used in research are already published, give a brief account and refer to the original publication. However, if the method used is modified from the original method, then researcher should mention the modifications done to the original protocol and validate its accuracy, precision, and repeatability.

It is best to report results as tables and figures wherever possible. Also, avoid duplication of text and ensure that the text summarizes the findings. Report the results with appropriate descriptive statistics. Furthermore, report any unexpected events that could affect the research results, and mention complete account of observations and explanations for missing data (if any).

6. Discussion

The discussion should set the research in context, strengthen its importance and support the research hypothesis. Summarize the main results of the study in one or two paragraphs and show how they logically fit in an overall scheme of studies. Compare the results with other investigations in the field of research and explain the differences.

7. Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements identify and thank the contributors to the study, who are not under the criteria of co-authors. It also includes the recognition of funding agency and universities that award scholarships or fellowships to researchers.

8. Declaration of Competing Interests

Finally, declaring the competing interests is essential to abide by ethical norms of unique research publishing. Competing interests arise when the author has more than one role that may lead to a situation where there is a conflict of interest.

Steps to Write a Research Paper Outline

- Write down all important ideas that occur to you concerning the research paper .

- Answer questions such as – what is the topic of my paper? Why is the topic important? How to formulate the hypothesis? What are the major findings?

- Add context and structure. Group all your ideas into sections – Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion/Conclusion.

- Add relevant questions to each section. It is important to note down the questions. This will help you align your thoughts.

- Expand the ideas based on the questions created in the paper outline.

- After creating a detailed outline, discuss it with your mentors and peers.

- Get enough feedback and decide on the journal you will submit to.

- The process of real writing begins.

Benefits of Creating a Research Paper Outline

As discussed, the research paper subheadings create an outline of what different aspects of research needs elaboration. This provides subtopics on which the researchers brainstorm and reach a conclusion to write. A research paper outline organizes the researcher’s thoughts and gives a clear picture of how to formulate the research protocols and results. It not only helps the researcher to understand the flow of information but also provides relation between the ideas.

A research paper outline helps researcher achieve a smooth transition between topics and ensures that no research point is forgotten. Furthermore, it allows the reader to easily navigate through the research paper and provides a better understanding of the research. The paper outline allows the readers to find relevant information and quotes from different part of the paper.

Research Paper Outline Template

A research paper outline template can help you understand the concept of creating a well planned research paper before beginning to write and walk through your journey of research publishing.

1. Research Title

A. Background i. Support with evidence ii. Support with existing literature studies

B. Thesis Statement i. Link literature with hypothesis ii. Support with evidence iii. Explain the knowledge gap and how this research will help build the gap 4. Body

A. Methods i. Mention materials and protocols used in research ii. Support with evidence

B. Results i. Support with tables and figures ii. Mention appropriate descriptive statistics

C. Discussion i. Support the research with context ii. Support the research hypothesis iii. Compare the results with other investigations in field of research

D. Conclusion i. Support the discussion and research investigation ii. Support with literature studies

E. Acknowledgements i. Identify and thank the contributors ii. Include the funding agency, if any

F. Declaration of Competing Interests

5. References

Download the Research Paper Outline Template!

Have you tried writing a research paper outline ? How did it work for you? Did it help you achieve your research paper writing goal? Do let us know about your experience in the comments below.

Downloadable format shared which is great. 🙂

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Reporting Research

Academic Essay Writing Made Simple: 4 types and tips

The pen is mightier than the sword, they say, and nowhere is this more evident…

- AI in Academia

- Trending Now

Simplifying the Literature Review Journey — A comparative analysis of 6 AI summarization tools

Imagine having to skim through and read mountains of research papers and books, only to…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for data interpretation

In research, choosing the right approach to understand data is crucial for deriving meaningful insights.…

Comparing Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies: 5 steps for choosing the right approach

The process of choosing the right research design can put ourselves at the crossroads of…

- Career Corner

Unlocking the Power of Networking in Academic Conferences

Embarking on your first academic conference experience? Fear not, we got you covered! Academic conferences…

Setting Rationale in Research: Cracking the code for excelling at research

Mitigating Survivorship Bias in Scholarly Research: 10 tips to enhance data integrity

The Power of Proofreading: Taking your academic work to the next level

Facing Difficulty Writing an Academic Essay? — Here is your one-stop solution!

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Making an Outline

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

An outline is a formal system used to develop a framework for thinking about what should be the organization and eventual contents of your paper. An outline helps you predict the overall structure and flow of a paper.

Why and How to Create a Useful Outline. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University.

Importance of...

Writing papers in college requires you to come up with sophisticated, complex, and sometimes very creative ways of structuring your ideas . Taking the time to draft an outline can help you determine if your ideas connect to each other, what order of ideas works best, where gaps in your thinking may exist, or whether you have sufficient evidence to support each of your points. It is also an effective way to think about the time you will need to complete each part of your paper before you begin writing.

A good outline is important because :

- You will be much less likely to get writer's block . An outline will show where you're going and how to get there. Use the outline to set goals for completing each section of your paper.

- It will help you stay organized and focused throughout the writing process and help ensure proper coherence [flow of ideas] in your final paper. However, the outline should be viewed as a guide, not a straitjacket. As you review the literature or gather data, the organization of your paper may change; adjust your outline accordingly.

- A clear, detailed outline ensures that you always have something to help re-calibrate your writing should you feel yourself drifting into subject areas unrelated to the research problem. Use your outline to set boundaries around what you will investigate.

- The outline can be key to staying motivated . You can put together an outline when you're excited about the project and everything is clicking; making an outline is never as overwhelming as sitting down and beginning to write a twenty page paper without any sense of where it is going.

- An outline helps you organize multiple ideas about a topic . Most research problems can be analyzed from a variety of perspectives; an outline can help you sort out which modes of analysis are most appropriate to ensure the most robust findings are discovered.

- An outline not only helps you organize your thoughts, but it can also serve as a schedule for when certain aspects of your writing should be accomplished . Review the assignment and highlight the due dates of specific tasks and integrate these into your outline. If your professor has not created specific deadlines, create your own deadlines by thinking about your own writing style and the need to manage your time around other course assignments.

How to Structure and Organize Your Paper. Odegaard Writing & Research Center. University of Washington; Why and How to Create a Useful Outline. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Lietzau, Kathleen. Creating Outlines. Writing Center, University of Richmond.

Structure and Writing Style

I. General Approaches

There are two general approaches you can take when writing an outline for your paper:

The topic outline consists of short phrases. This approach is useful when you are dealing with a number of different issues that could be arranged in a variety of different ways in your paper. Due to short phrases having more content than using simple sentences, they create better content from which to build your paper.

The sentence outline is done in full sentences. This approach is useful when your paper focuses on complex issues in detail. The sentence outline is also useful because sentences themselves have many of the details in them needed to build a paper and it allows you to include those details in the sentences instead of having to create an outline of short phrases that goes on page after page.

II. Steps to Making the Outline

A strong outline details each topic and subtopic in your paper, organizing these points so that they build your argument toward an evidence-based conclusion. Writing an outline will also help you focus on the task at hand and avoid unnecessary tangents, logical fallacies, and underdeveloped paragraphs.

- Identify the research problem . The research problem is the focal point from which the rest of the outline flows. Try to sum up the point of your paper in one sentence or phrase. It also can be key to deciding what the title of your paper should be.

- Identify the main categories . What main points will you analyze? The introduction describes all of your main points; the rest of your paper can be spent developing those points.

- Create the first category . What is the first point you want to cover? If the paper centers around a complicated term, a definition can be a good place to start. For a paper that concerns the application and testing of a particular theory, giving the general background on the theory can be a good place to begin.

- Create subcategories . After you have followed these steps, create points under it that provide support for the main point. The number of categories that you use depends on the amount of information that you are trying to cover. There is no right or wrong number to use.

Once you have developed the basic outline of the paper, organize the contents to match the standard format of a research paper as described in this guide.

III. Things to Consider When Writing an Outline

- There is no rule dictating which approach is best . Choose either a topic outline or a sentence outline based on which one you believe will work best for you. However, once you begin developing an outline, it's helpful to stick to only one approach.

- Both topic and sentence outlines use Roman and Arabic numerals along with capital and small letters of the alphabet arranged in a consistent and rigid sequence. A rigid format should be used especially if you are required to hand in your outline.

- Although the format of an outline is rigid, it shouldn't make you inflexible about how to write your paper. Often when you start investigating a research problem [i.e., reviewing the research literature], especially if you are unfamiliar with the topic, you should anticipate the likelihood your analysis could go in different directions. If your paper changes focus, or you need to add new sections, then feel free to reorganize the outline.

- If appropriate, organize the main points of your outline in chronological order . In papers where you need to trace the history or chronology of events or issues, it is important to arrange your outline in the same manner, knowing that it's easier to re-arrange things now than when you've almost finished your paper.

- For a standard research paper of 15-20 pages, your outline should be no more than few pages in length . It may be helpful as you are developing your outline to also write down a tentative list of references.

Muirhead, Brent. “Using Outlines to Improve Online Student Writing Skills.” Journal on School Educational Technology 1, (2005): 17-23; Four Main Components for Effective Outlines. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; How to Make an Outline. Psychology Writing Center. University of Washington; Kartawijaya, Sukarta. “Improving Students’ Writing Skill in Writing Paragraph through an Outline Technique.” Curricula: Journal of Teaching and Learning 3 (2018); Organization: Informal Outlines. The Reading/Writing Center. Hunter College; Organization: Standard Outline Form. The Reading/Writing Center. Hunter College; Outlining. Department of English Writing Guide. George Mason University; Plotnic, Jerry. Organizing an Essay. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Reverse Outline. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Reverse Outlines: A Writer's Technique for Examining Organization. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Using Outlines. Writing Tutorial Services, Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. Indiana University; Writing: Considering Structure and Organization. Institute for Writing Rhetoric. Dartmouth College.

Writing Tip

A Disorganized Outline Means a Disorganized Paper!

If, in writing your paper, it begins to diverge from your outline, this is very likely a sign that you've lost your focus. How do you know whether to change the paper to fit the outline, or, that you need to reconsider the outline so that it fits the paper? A good way to check your progress is to use what you have written to recreate the outline. This is an effective strategy for assessing the organization of your paper. If the resulting outline says what you want it to say and it is in an order that is easy to follow, then the organization of your paper has been successful. If you discover that it's difficult to create an outline from what you have written, then you likely need to revise your paper.

- << Previous: Choosing a Title

- Next: Paragraph Development >>

- Last Updated: May 30, 2024 9:38 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

How to Do Research: A Step-By-Step Guide: 4b. Outline the Paper

- Get Started

- 1a. Select a Topic

- 1b. Develop Research Questions

- 1c. Identify Keywords

- 1d. Find Background Information

- 1e. Refine a Topic

- 2a. Search Strategies

- 2d. Articles

- 2e. Videos & Images

- 2f. Databases

- 2g. Websites

- 2h. Grey Literature

- 2i. Open Access Materials

- 3a. Evaluate Sources

- 3b. Primary vs. Secondary

- 3c. Types of Periodicals

- 4a. Take Notes

- 4b. Outline the Paper

- 4c. Incorporate Source Material

- 5a. Avoid Plagiarism

- 5b. Zotero & MyBib

- 5c. MLA Formatting

- 5d. MLA Citation Examples

- 5e. APA Formatting

- 5f. APA Citation Examples

- 5g. Annotated Bibliographies

Why Outline?

For research papers, a formal outline can help you keep track of large amounts of information.

Sample Outline

Thesis: Federal regulations need to foster laws that will help protect wetlands, restore those that have been destroyed, and take measures to improve the damage from overdevelopment.

I. Nature's ecosystem

A. Loss of wetlands nationally

B. Loss of wetlands in Illinois

1. More flooding and poorer water quality

2. Lost ability to prevent floods, clean water and store water

II. Dramatic floods

A, Cost in dollars and lives

1. 13 deaths between 1988 and 1998

2. Cost of $39 million per year

B. Great Midwestern Flood of 1993

1. Lost wetlands in IL

2. Devastation in some states

C. Flood Prevention

1. Plants and Soils

2. Floodplain overflow

III. Wetland laws

A. Inadequately informed legislators

1. Watersheds

2. Interconnections in natural water systems

B. Water purification

IV. Need to save wetlands

A. New federal definition

B. Re-education about interconnectedness

1. Ecology at every grade level

2. Education for politicians and developers

3. Choices in schools and people's lives

Example taken from The Bedford Guide for College Writers (9th ed).

How to Create an Outline

To create an outline:

- Place your thesis statement at the beginning.

- List the major points that support your thesis. Label them in Roman numerals (I, II, III, etc.).

- List supporting ideas or arguments for each major point. Label them in capital letters (A, B, C, etc.).

- If applicable, continue to sub-divide each supporting idea until your outline is fully developed. Label them 1, 2, 3, etc., and then a, b, c, etc.

NOTE: EasyBib has a function that will help you create a clear and effective outline.

How to Structure an Outline

- << Previous: 4a. Take Notes

- Next: 4c. Incorporate Source Material >>

- Last Updated: May 29, 2024 1:53 PM

- URL: https://libguides.elmira.edu/research

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write a Research Paper Outline with Examples

You sometimes have to submit an essay outline or a research proposal checklist for a research project before you do most of the actual research to show that you have understood the assignment, defined a good research question or hypothesis, and contemplated the structure of your research paper. You can find various templates and examples for such outlines, which usually begin with “put your thesis statement/research question at the top” and then ask you to decide whether to add your supporting ideas/points in “alphanumeric,” “decimal,” or “full-sentence” style.

That is certainly one useful (if not overly formalized) way of using outlining to prepare to draft an academic text. But here we want to talk about how to make an outline after you have done a research project or thesis work and are not quite sure how to put everything together into a written thesis to hand in or a research paper manuscript to submit to a journal.

What is a research paper outline?

Creating a research project outline entails more than just listing bullet points (although you can use bullet points and lists in your outline). It includes how to organize everything you have done and thought about and want to say about your work into a clear structure you can use as the basis for your research paper.

There are two different methods of creating an outline: let’s call these “abstract style” and “paper style.” These names reflect how briefly you summarize your work at this initial point, or show how extensive and complicated the methods and designs you used and the data you collected are. The type of outline you use also depends on how clear the story you want to tell is and how much organizing and structuring of information you still need to do before you can draft your actual paper.

Table of Contents:

- Abstract-Style Outline Format

- Paper-Style Outline Format

Additional Tips for Outlining a Research Paper in English

Abstract-style research paper outline format.

A research paper outline in abstract style consists, like the abstract of a research paper , of short answers to the essential questions that anyone trying to understand your work would ask.

- Why did you decide to do what you did?

- What exactly did you do?

- How did you do it?

- What did you find?

- What does it mean?

- What should you/we/someone else do now?

These questions form the structure of not only a typical research paper abstract but also a typical article manuscript. They will eventually be omitted and replaced by the usual headers, such as Introduction/Background, Aim, Methods, Results, Discussion, Conclusions, etc. Answering these key questions for yourself first (with keywords or short sentences) and then sticking to the same structure and information when drafting your article will ensure that your story is consistent and that there are no logical gaps or contradictions between the different sections of a research paper .

If you draft this abstract outline carefully, you can use it as the basis for every other part of your paper. You reduce it even more, down to the absolute essential elements, to create your manuscript title ; you choose your keywords on the basis of the summary presented here; and you expand it into the introduction , methods , results , and discussion sections of your paper without contradicting yourself or losing the logical thread.

Research Paper Outline Example (Abstract style)

Let’s say you did a research project on the effect of university online classes on attendance rates and create a simple outline example using these six questions:

1. Why did you decide to do what you did?

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, many university courses around the world have been moved online, at least temporarily. Since students have been saving time on commuting, I wondered if attendance rates have increased overall.

2. What exactly did you do?

I compared attendance scores for courses that were taught both before (offline) and during (online) the COVID-19 pandemic at my university.

3. How did you do it?

I selected five popular subjects (business, law, medicine, psychology, art & design) and one general course per subject; then I contacted the professors in charge and asked them to provide me with anonymized attendance scores.

4. What did you find?

Attendance did not significantly change for medicine and law, but slightly dropped for the other three subjects. I found no difference between male and female students.

5. What does it mean?

Even though students saved time on traveling between their homes and the campus during the COVID-19 pandemic, they did not attend classes more consistently; in some subjects, they missed more classes than before.

6. What should you/we/someone else do now?

Since I do not have any other information about the students, I can only speculate on potential explanations. Next, I will put together a questionnaire to assess how students have been coping with online classes and how the experiences from this time can benefit university teaching and learning in general.

Note that you could have made the same outline using just keywords instead of full sentences. You could also have added more methodological details or the results of your statistical analysis. However, when you can break everything down to the absolute essentials like this, you will have a good foundation upon which to develop a full paper.

However, maybe your study just seems too complicated. So you look at these questions and then at your notes and data and have no idea how to come up with such simple answers. Or maybe things went in a completely different direction since you started writing your paper, so now you are no longer sure what the main point of your experiments was and what the main conclusion should be. If that is how you feel right now, then outlining your paper in “paper style” might be the right method for you.

Paper-Style Research Paper Outline Format

The purpose of a paper-style outline is the same as that of an abstract-style outline: You want to organize your initial thoughts and plans, the methods and tools you used, all the experiments you conducted, the data you collected and analyzed, as well as your results, into a clear structure so that you can identify the main storyline for your paper and the main conclusions that you want the reader to take from it.

First, take as much space as you need and simply jot down everything in your study you planned to do, everything you did, and everything you thought about based on your notes, lab book, and earlier literature you read or used. Such an outline can contain all your initial ideas, the timeline of all your pilots and all your experiments, the reasons why you changed direction or designed new experiments halfway through your study, all the analyses you ever did, all the feedback and criticism you already got from supervisors and seniors or during conference presentations, and all the ideas you have for future work. If this is your thesis or your first publication, then your first outline might look quite messy – and that is exactly why you need to structure your paper before trying to write everything up.

So you have finally remembered all you have done in your study and have written everything down. The next step is to realize that you cannot throw all of this at the reader and expect them to put it together. You will have to create a story that is clear and consistent, contains all the essential information (and leaves out any that is not), and leads the reader the same way the abstract outline does, from why over what and how to what you found and what it all means .

This does not mean you should suppress results that did not come out as intended or try to make your study look smoother. But the reader does not really need to know all the details about why you changed your research question after your initial literature search or some failed pilots. Instead of writing down the simple questions we used for the abstract outline, to organize your still messy notes, write down the main sections of the manuscript you are trying to put together. Additionally, include what kinds of information needs to go where in your paper’s structure.

1. Introduction Section:

What field is your research part of?

What other papers did you read before deciding on your topic?

Who is your target audience and how much information do your readers need to understand where you are coming from?

Can you summarize what you did in two sentences?

Did you have a clear hypothesis? If not, what were the potential outcomes of your work?

2. Methods Section:

List all the methods, questionnaires, and tests you used.

Are your methods all standard in the field or do you need to explain them?

List everything chronologically or according to topics, whatever makes more sense. Read more about writing the Methods section if you need help with this important decision.

3. Results Section:

Use the same timeline or topics you introduced in the method section.

Make sure you answer all the questions you raised in the introduction.

Use tables, graphs, and other visualizations to guide the reader.

Don’t present results of tests/analyses that you did not mention in the methods.

4. Discussion/Conclusion Section:

Summarize quickly what you did and found but don’t repeat your results.

Explain whether your findings were to be expected, are new and surprising, are in line with the existing literature, or are contradicting some earlier work.

Do you think your findings can be generalized? Can they be useful for people in certain professions or other fields?

Does your study have limitations? What would you do differently next time?

What future research do you think should be done based on your findings?

5. Conclusion Statement/Paragraph:

This is your take-home message for the reader. Make sure that your conclusion is directly related to your initial research question.

Now you can simply reorganize your notes (if you use computer software) or fill in the different sections and cross out information on your original list. When you have used all your jotted notes, go through your new outline and check what is still missing. Now check once more that your conclusion is related to your initial research question. If that is the case, you are good to go. You can now either break your outline down further and shorten it into an abstract, or you can expand the different outline sections into a full article.

If you are a non-native speaker of English, then you might take notes in your mother language or maybe in different languages, read literature in your mother language, and generally not think in English while doing your research. If your goal is to write your thesis or paper in English, however, then our advice is to only use your mother language when listing keywords at the very beginning of the outlining process (if at all). As soon as you write down full sentences that you want to go into your paper eventually, you can save yourself a lot of work, avoid mistakes later in the process, and train your brain (which will help you immensely the next time you write an academic text), if you stick to English.

Another thing to keep in mind is that starting to write in full sentences too early in the process means that you might need to omit some passages (maybe even entire paragraphs) when you later decide to change the structure or storyline of your paper. Depending on how much you enjoy (or hate) writing in English and how much effort it costs you, having to throw away a perfectly fine paragraph that you invested a lot of time in can be incredibly frustrating. Our advice is therefore to not spend too much time on writing and to not get too attached to exact wording before you have a solid outline that you then only need to fill in and expand into a full paper.

Once you have finished drafting your paper, consider using professional proofreading and English editing service to revise your paper and prepare it for submission to journals. Wordvice offers a paper editing service , manuscript editing service , dissertation editing service , and thesis editing service to polish and edit your research work and correct any errors in style or formatting.

And while you draft your article, make use of Wordvice AI, a free AI Proofreader that identifies and fixes errors in punctuation, spelling, and grammar in any academic document.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write an Outline in APA Format

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amanda Tust is a fact-checker, researcher, and writer with a Master of Science in Journalism from Northwestern University's Medill School of Journalism.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Amanda-Tust-1000-ffe096be0137462fbfba1f0759e07eb9.jpg)

- Before Starting Your Outline

- How to Create an Outline

Writing a psychology paper can feel like an overwhelming task. From picking a topic to finding sources to cite, each step in the process comes with its own challenges. Luckily, there are strategies to make writing your paper easier—one of which is creating an outline using APA format .

Here we share what APA format entails and the basics of this writing style. Then we get into how to create a research paper outline using APA guidelines, giving you a strong foundation to start crafting your content.

At a Glance

APA format is the standard writing style used for psychology research papers. Creating an outline using APA format can help you develop and organize your paper's structure, also keeping you on task as you sit down to write the content.

APA Format Basics

Formatting dictates how papers are styled, which includes their organizational structure, page layout, and how information is presented. APA format is the official style of the American Psychological Association (APA).

Learning the basics of APA format is necessary for writing effective psychology papers, whether for your school courses or if you're working in the field and want your research published in a professional journal. Here are some general APA rules to keep in mind when creating both your outline and the paper itself.

Font and Spacing

According to APA style, research papers are to be written in a legible and widely available font. Traditionally, Times New Roman is used with a 12-point font size. However, other serif and sans serif fonts like Arial or Georgia in 11-point font sizes are also acceptable.

APA format also dictates that the research paper be double-spaced. Each page has 1-inch margins on all sides (top, bottom, left, and right), and the page number is to be placed in the upper right corner of each page.

Both your psychology research paper and outline should include three key sections:

- Introduction : Highlights the main points and presents your hypothesis

- Body : Details the ideas and research that support your hypothesis

- Conclusion : Briefly reiterates your main points and clarifies support for your position

Headings and Subheadings

APA format provides specific guidelines for using headings and subheadings. They are:

- Main headings : Use Roman numerals (I, II, III, IV)

- Subheadings: Use capital letters (A, B, C, D)

If you need further subheadings within the initial subheadings, start with Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3), then lowercase letters (a, b, c), then Arabic numerals inside parentheses [(1), (2), (3)]

Before Starting Your APA Format Outline

While APA format does not provide specific rules for creating an outline, you can still develop a strong roadmap for your paper using general APA style guidance. Prior to drafting your psychology research paper outline using APA writing style, taking a few important steps can help set you up for greater success.

Review Your Instructor's Requirements

Look over the instructions for your research paper. Your instructor may have provided some type of guidance or stated what they want. They may have even provided specific requirements for what to include in your outline or how it needs to be structured and formatted.

Some instructors require research paper outlines to use decimal format. This structure uses Arabic decimals instead of Roman numerals or letters. In this case, the main headings in an outline would be 1.0, 1.2, and 1.3, while the subheadings would be 1.2.1, 1.2.2, 1.2.3, and so on.

Consider Your Preferences

After reviewing your instructor's requirements, consider your own preferences for organizing your outline. Think about what makes the most sense for you, as well as what type of outline would be most helpful when you begin writing your research paper.

For example, you could choose to format your headings and subheadings as full sentences, or you might decide that you prefer shorter headings that summarize the content. You can also use different approaches to organizing the lettering and numbering in your outline's subheadings.

Whether you are creating your outline according to your instructor's guidelines or following your own organizational preferences, the most important thing is that you are consistent.

Formatting Tips

When getting ready to start your research paper outline using APA format, it's also helpful to consider how you will format it. Here are a few tips to help:

- Your outline should begin on a new page.

- Before you start writing the outline, check that your word processor does not automatically insert unwanted text or notations (such as letters, numbers, or bullet points) as you type. If it does, turn off auto-formatting.

- If your instructor requires you to specify your hypothesis in your outline, review your assignment instructions to find out where this should be placed. They may want it presented at the top of your outline, for example, or included as a subheading.

How to Create a Research Paper Outline Using APA

Understanding APA format basics can make writing psychology research papers much easier. While APA format does not provide specific rules for creating an outline, you can still develop a strong roadmap for your paper using general APA style guidance, your instructor's requirements, and your own personal organizational preferences.

Typically you won't need to turn your outline in with your final paper. But that doesn't mean you should skip creating one. A strong paper starts with a solid outline. Developing this outline can help you organize your writing and ensure that you effectively communicate your paper's main points and arguments. Here's how to create a research outline using APA format.

Start Your Research

While it may seem like you should create an outline before starting your research, the opposite is actually true. The information you find when researching your psychology research topic will start to reveal the information you'll want to include in your paper—and in your outline.

As you research, consider the main arguments you intend to make in your paper. Look for facts that support your hypothesis, keeping track of where you find these facts so you can cite them when writing your paper. The more organized you are when creating your outline, the easier it becomes to draft the paper itself.

If you are required to turn in your outline before you begin working on your paper, keep in mind that you may need to include a list of references that you plan to use.

Draft Your Outline Using APA Format

Once you have your initial research complete, you have enough information to create an outline. Start with the main headings (which are noted using Roman numerals I, II, III, etc.). Here's an example of the main headings you may use if you were writing an APA format outline for a research paper in support of using cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for anxiety :

- Introduction

- What CBT Is

- How CBT Helps Ease Anxiety

- Research Supporting CBT for Anxiety

- Potential Drawbacks of CBT for Anxiety and How to Overcome Them

Under each main heading, list your main points or key ideas using subheadings (as noted with A, B, C, etc.). Sticking with the same example, subheadings under "What CBT Is" may include:

- Basic CBT Principles

- How CBT Works

- Conditions CBT Has Been Found to Help Treat

You may also decide to include additional subheadings under your initial subheadings to add more information or clarify important points relevant to your hypothesis. Examples of additional subheadings (which are noted with 1, 2, 3, etc.) that could be included under "Basic CBT Principles" include:

- Is Goal-Oriented

- Focuses on Problem-Solving

- Includes Self-Monitoring

Begin Writing Your Research Paper

The reason this step is included when drafting your research paper outline using APA format is that you'll often find that your outline changes as you begin to dive deeper into your proposed topic. New ideas may emerge or you may decide to narrow your topic further, even sometimes changing your hypothesis altogether.

All of these factors can impact what you write about, ultimately changing your outline. When writing your paper, there are a few important points to keep in mind:

- Follow the structure that your instructor specifies.

- Present your strongest points first.

- Support your arguments with research and examples.

- Organize your ideas logically and in order of strength.

- Keep track of your sources.

- Present and debate possible counterarguments, and provide evidence that counters opposing arguments.

Update Your Final Outline

The final version of your outline should reflect your completed draft. Not only does updating your outline at this point help ensure that you've covered the topics you want in your paper, but it also gives you another opportunity to verify that your paper follows a logical sequence.

When reading through your APA-formatted outline, consider whether it flows naturally from one topic to the next. You wouldn't talk about how CBT works before discussing what CBT is, for example. Taking this final step can give you a more solid outline, and a more solid research paper.

American Psychological Association. About APA Style .

Purdue University Online Writing Lab. Types of outlines and samples .

Mississippi College. Writing Center: Outlines .

American Psychological Association. APA style: Style and Grammar Guidelines .

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

APA Research Paper Outline: Examples and Template

Table of contents

- 1 Why Is Research Paper Format Necessary?

- 2.1 Purpose of research paper outline

- 2.2 APA outline example

- 3.1 APA paper outline example

- 3.2 Introduction:

- 3.4 Conclusion:

- 4 The Basic APA Outline Format

- 5 APA Style Outline Template Breakdown

- 6.1 APA Research Paper Outline Example

- 6.2 APA Paper Outline Format Example

- 7.1 First Paragraph: Hook and Thesis

- 7.2 Main Body

- 7.3 Conclusion

- 7.4 Decimal APA outline format example

- 7.5 Decimal APA outline format layout

- 8.1 A definite goal

- 8.2 Division

- 8.3 Parallelism

- 8.4 Coordination

- 8.5 Subordination

- 8.6 Avoid Redundancy

- 8.7 Wrap it up in a good way

- 8.8 Conclusion

Formatting your paper in APA can be daunting if this is your first time. The American Psychological Association (APA) offers a guide or rules to follow when conducting projects in the social sciences or writing papers. The standard APA fromat a research paper outline includes a proper layout from the title page to the final reference pages. There are formatting samples to create outlines before writing a paper. Amongst other strategies, creating an outline is the easiest way to APA format outline template.

Why Is Research Paper Format Necessary?

Consistency in the sequence, structure, and format when writing a research paper encourages readers to concentrate on the substance of a paper rather than how it is presented. The requirements for paper format apply to student assignments and papers submitted for publication in a peer-reviewed publication. APA paper outline template style may be used to create a website, conference poster, or PowerPoint presentation . If you plan to use the style for other types of work like a website, conference poster, or even PowerPoint presentation, you must format your work accordingly to adjust to requirements. For example, you may need different line spacing and font sizes. Follow the formatting rules provided by your institution or publication to ensure its formatting standards are followed as closely as possible. However, to logically structure your document, you need a research paper outline in APA format. You may ask: why is it necessary to create an outline for an APA research paper?

Concept & Purposes of Research Paper Outline

A path, direction, or action plan! Writing short essays without a layout may seem easy, but not for 10,000 or more words. Yet, confusing a table of contents with an outline is a major issue. The table of contents is an orderly list of all the chapters’ front matter, primary, and back matter. It includes sections and, often, figures in your work, labeled by page number. On the other hand, a research APA-style paper outline is a proper structure to follow.

Purpose of research paper outline

An outline is a formalized essay in which you give your own argument to support your point of view. And when you write your apa outline template, you expand on what you already know about the topic. Academic writing papers examine an area of expertise to get the latest and most accurate information to work on that topic. It serves various purposes, including:

- APA paper outline discusses the study’s core concepts.

- The research paper outlines to define the link between your ideas and the thesis.