Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9.3 Organizing Your Writing

Learning objectives.

- Understand how and why organizational techniques help writers and readers stay focused.

- Assess how and when to use chronological order to organize an essay.

- Recognize how and when to use order of importance to organize an essay.

- Determine how and when to use spatial order to organize an essay.

The method of organization you choose for your essay is just as important as its content. Without a clear organizational pattern, your reader could become confused and lose interest. The way you structure your essay helps your readers draw connections between the body and the thesis, and the structure also keeps you focused as you plan and write the essay. Choosing your organizational pattern before you outline ensures that each body paragraph works to support and develop your thesis.

This section covers three ways to organize body paragraphs:

- Chronological order

- Order of importance

- Spatial order

When you begin to draft your essay, your ideas may seem to flow from your mind in a seemingly random manner. Your readers, who bring to the table different backgrounds, viewpoints, and ideas, need you to clearly organize these ideas in order to help process and accept them.

A solid organizational pattern gives your ideas a path that you can follow as you develop your draft. Knowing how you will organize your paragraphs allows you to better express and analyze your thoughts. Planning the structure of your essay before you choose supporting evidence helps you conduct more effective and targeted research.

Chronological Order

In Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” , you learned that chronological arrangement has the following purposes:

- To explain the history of an event or a topic

- To tell a story or relate an experience

- To explain how to do or to make something

- To explain the steps in a process

Chronological order is mostly used in expository writing , which is a form of writing that narrates, describes, informs, or explains a process. When using chronological order, arrange the events in the order that they actually happened, or will happen if you are giving instructions. This method requires you to use words such as first , second , then , after that , later , and finally . These transition words guide you and your reader through the paper as you expand your thesis.

For example, if you are writing an essay about the history of the airline industry, you would begin with its conception and detail the essential timeline events up until present day. You would follow the chain of events using words such as first , then , next , and so on.

Writing at Work

At some point in your career you may have to file a complaint with your human resources department. Using chronological order is a useful tool in describing the events that led up to your filing the grievance. You would logically lay out the events in the order that they occurred using the key transition words. The more logical your complaint, the more likely you will be well received and helped.

Choose an accomplishment you have achieved in your life. The important moment could be in sports, schooling, or extracurricular activities. On your own sheet of paper, list the steps you took to reach your goal. Try to be as specific as possible with the steps you took. Pay attention to using transition words to focus your writing.

Keep in mind that chronological order is most appropriate for the following purposes:

- Writing essays containing heavy research

- Writing essays with the aim of listing, explaining, or narrating

- Writing essays that analyze literary works such as poems, plays, or books

When using chronological order, your introduction should indicate the information you will cover and in what order, and the introduction should also establish the relevance of the information. Your body paragraphs should then provide clear divisions or steps in chronology. You can divide your paragraphs by time (such as decades, wars, or other historical events) or by the same structure of the work you are examining (such as a line-by-line explication of a poem).

On a separate sheet of paper, write a paragraph that describes a process you are familiar with and can do well. Assume that your reader is unfamiliar with the procedure. Remember to use the chronological key words, such as first , second , then , and finally .

Order of Importance

Recall from Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” that order of importance is best used for the following purposes:

- Persuading and convincing

- Ranking items by their importance, benefit, or significance

- Illustrating a situation, problem, or solution

Most essays move from the least to the most important point, and the paragraphs are arranged in an effort to build the essay’s strength. Sometimes, however, it is necessary to begin with your most important supporting point, such as in an essay that contains a thesis that is highly debatable. When writing a persuasive essay, it is best to begin with the most important point because it immediately captivates your readers and compels them to continue reading.

For example, if you were supporting your thesis that homework is detrimental to the education of high school students, you would want to present your most convincing argument first, and then move on to the less important points for your case.

Some key transitional words you should use with this method of organization are most importantly , almost as importantly , just as importantly , and finally .

During your career, you may be required to work on a team that devises a strategy for a specific goal of your company, such as increasing profits. When planning your strategy you should organize your steps in order of importance. This demonstrates the ability to prioritize and plan. Using the order of importance technique also shows that you can create a resolution with logical steps for accomplishing a common goal.

On a separate sheet of paper, write a paragraph that discusses a passion of yours. Your passion could be music, a particular sport, filmmaking, and so on. Your paragraph should be built upon the reasons why you feel so strongly. Briefly discuss your reasons in the order of least to greatest importance.

Spatial Order

As stated in Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” , spatial order is best used for the following purposes:

- Helping readers visualize something as you want them to see it

- Evoking a scene using the senses (sight, touch, taste, smell, and sound)

- Writing a descriptive essay

Spatial order means that you explain or describe objects as they are arranged around you in your space, for example in a bedroom. As the writer, you create a picture for your reader, and their perspective is the viewpoint from which you describe what is around you.

The view must move in an orderly, logical progression, giving the reader clear directional signals to follow from place to place. The key to using this method is to choose a specific starting point and then guide the reader to follow your eye as it moves in an orderly trajectory from your starting point.

Pay attention to the following student’s description of her bedroom and how she guides the reader through the viewing process, foot by foot.

Attached to my bedroom wall is a small wooden rack dangling with red and turquoise necklaces that shimmer as you enter. Just to the right of the rack is my window, framed by billowy white curtains. The peace of such an image is a stark contrast to my desk, which sits to the right of the window, layered in textbooks, crumpled papers, coffee cups, and an overflowing ashtray. Turning my head to the right, I see a set of two bare windows that frame the trees outside the glass like a 3D painting. Below the windows is an oak chest from which blankets and scarves are protruding. Against the wall opposite the billowy curtains is an antique dresser, on top of which sits a jewelry box and a few picture frames. A tall mirror attached to the dresser takes up most of the wall, which is the color of lavender.

The paragraph incorporates two objectives you have learned in this chapter: using an implied topic sentence and applying spatial order. Often in a descriptive essay, the two work together.

The following are possible transition words to include when using spatial order:

- Just to the left or just to the right

- On the left or on the right

- Across from

- A little further down

- To the south, to the east, and so on

- A few yards away

- Turning left or turning right

On a separate sheet of paper, write a paragraph using spatial order that describes your commute to work, school, or another location you visit often.

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

Key Takeaways

- The way you organize your body paragraphs ensures you and your readers stay focused on and draw connections to, your thesis statement.

- A strong organizational pattern allows you to articulate, analyze, and clarify your thoughts.

- Planning the organizational structure for your essay before you begin to search for supporting evidence helps you conduct more effective and directed research.

- Chronological order is most commonly used in expository writing. It is useful for explaining the history of your subject, for telling a story, or for explaining a process.

- Order of importance is most appropriate in a persuasion paper as well as for essays in which you rank things, people, or events by their significance.

- Spatial order describes things as they are arranged in space and is best for helping readers visualize something as you want them to see it; it creates a dominant impression.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

How to Organize an Essay

Last Updated: March 27, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Jake Adams . Jake Adams is an academic tutor and the owner of Simplifi EDU, a Santa Monica, California based online tutoring business offering learning resources and online tutors for academic subjects K-College, SAT & ACT prep, and college admissions applications. With over 14 years of professional tutoring experience, Jake is dedicated to providing his clients the very best online tutoring experience and access to a network of excellent undergraduate and graduate-level tutors from top colleges all over the nation. Jake holds a BS in International Business and Marketing from Pepperdine University. There are 17 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 284,365 times.

Essay Template and Sample Essay

Laying the Groundwork

- For example, a high-school AP essay should have a very clear structure, with your introduction and thesis statement first, 3-4 body paragraphs that further your argument, and a conclusion that ties everything together.

- On the other hand, a creative nonfiction essay might wait to present the thesis till the very end of the essay and build up to it.

- A compare-and-contrast essay can be organized so that you compare two things in a single paragraph and then have a contrasting paragraph, or you can organize it so that you compare and contrast a single thing in the same paragraph.

- You can also choose to organize your essay chronologically, starting at the beginning of the work or historical period you're discussing and going through to the end. This can be helpful for essays where chronology is important to your argument (like a history paper or lab report), or if you're telling a story in your essay.

- The “support” structure begins with your thesis laid out clearly in the beginning and supports it through the rest of the essay.

- The “discovery” structure builds to the thesis by moving through points of discussion until the thesis seems the inevitable, correct view.

- The “exploratory” structure looks at the pros and cons of your chosen topic. It presents the various sides and usually concludes with your thesis.

- If you haven't been given an assignment, you can always run ideas by your instructor or advisor to see if they're on track.

- Ask questions about anything you don't understand. It's much better to ask questions before you put hours of work into your essay than it is to have to start over because you didn't clarify something. As long as you're polite, almost all instructors will be happy to answer your questions.

- For example, are you writing an opinion essay for your school newspaper? Your fellow students are probably your audience in this case. However, if you're writing an opinion essay for the local newspaper, your audience could be people who live in your town, people who agree with you, people who don't agree with you, people who are affected by your topic, or any other group you want to focus on.

Getting the Basics Down

- A thesis statement acts as the “road map” for your paper. It tells your audience what to expect from the rest of your essay.

- Include the most salient points within your thesis statement. For example, your thesis may be about the similarity between two literary works. Describe the similarities in general terms within your thesis statement.

- Consider the “So what?” question. A good thesis will explain why your idea or argument is important. Ask yourself: if a friend asked you “So what?” about your thesis, would you have an answer?

- The “3-prong thesis” is common in high school essays, but is often frowned upon in college and advanced writing. Don't feel like you have to restrict yourself to this limited form.

- Revise your thesis statement. If in the course of writing your essay you discover important points that were not touched upon in your thesis, edit your thesis.

- If you have a librarian available, don't be afraid to consult with him or her! Librarians are trained in helping you identify credible sources for research and can get you started in the right direction.

- Try freewriting. With freewriting, you don't edit or stop yourself. You just write (say, for 15 minutes at a time) about anything that comes into your head about your topic.

- Try a mind map. Start by writing down your central topic or idea, and then draw a box around it. Write down other ideas and connect them to see how they relate. [14] X Research source

- Try cubing. With cubing, you consider your chosen topic from 6 different perspectives: 1) Describe it, 2) Compare it, 3) Associate it, 4) Analyze it, 5) Apply it, 6) Argue for and against it.

- If your original thesis was very broad, you can also use this chance to narrow it down. For example, a thesis about “slavery and the Civil War” is way too big to manage, even for a doctoral dissertation. Focus on more specific terms, which will help you when you start you organize your outline. [16] X Trustworthy Source University of North Carolina Writing Center UNC's on-campus and online instructional service that provides assistance to students, faculty, and others during the writing process Go to source

Organizing the Essay

- Determine the order in which you will discuss the points. If you're planning to discuss 3 challenges of a particular management strategy, you might capture your reader's attention by discussing them in the order of most problematic to least. Or you might choose to build the intensity of your essay by starting with the smallest problem first.

- For example, a solid paragraph about Hamlet's insanity could draw from several different scenes in which he appears to act insane. Even though these scenes don't all cluster together in the original play, discussing them together will make a lot more sense than trying to discuss the whole play from start to finish.

- Ensure that your topic sentence is directly related to your main argument. Avoid statements that may be on the general topic, but not directly relevant to your thesis.

- Make sure that your topic sentence offers a “preview” of your paragraph's argument or discussion. Many beginning writers forget to use the first sentence this way, and end up with sentences that don't give a clear direction for the paragraph.

- For example, compare these two first sentences: “Thomas Jefferson was born in 1743” and “Thomas Jefferson, who was born in 1743, became one of the most important people in America by the end of the 18th century.”

- The first sentence doesn't give a good direction for the paragraph. It states a fact but leaves the reader clueless about the fact's relevance. The second sentence contextualizes the fact and lets the reader know what the rest of the paragraph will discuss.

- Transitions help underline your essay's overall organizational logic. For example, beginning a paragraph with something like “Despite the many points in its favor, Mystic Pizza also has several elements that keep it from being the best pizza in town” allows your reader to understand how this paragraph connects to what has come before.

- Transitions can also be used inside paragraphs. They can help connect the ideas within a paragraph smoothly so your reader can follow them.

- If you're having a lot of trouble connecting your paragraphs, your organization may be off. Try the revision strategies elsewhere in this article to determine whether your paragraphs are in the best order.

- The Writing Center at the University of Wisconsin - Madison has a handy list of transitional words and phrases, along with the type of transition they indicate. [22] X Research source

- You can try returning to your original idea or theme and adding another layer of sophistication to it. Your conclusion can show how necessary your essay is to understanding something about the topic that readers would not have been prepared to understand before.

- For some types of essays, a call to action or appeal to emotions can be quite helpful in a conclusion. Persuasive essays often use this technique.

- Avoid hackneyed phrases like “In sum” or “In conclusion.” They come across as stiff and cliched on paper.

Revising the Plan

- You can reverse-outline on the computer or on a printed draft, whichever you find easier.

- As you read through your essay, summarize the main idea (or ideas) of each paragraph in a few key words. You can write these on a separate sheet, on your printed draft, or as a comment in a word processing document.

- Look at your key words. Do the ideas progress in a logical fashion? Or does your argument jump around?

- If you're having trouble summarizing the main idea of each paragraph, it's a good sign that your paragraphs have too much going on. Try splitting your paragraphs up.

- You may also find with this technique that your topic sentences and transitions aren't as strong as they could be. Ideally, your paragraphs should have only one way they could be organized for maximum effectiveness. If you can put your paragraphs in any order and the essay still kind of makes sense, you may not be building your argument effectively.

- For example, you might find that placing your least important argument at the beginning drains your essay of vitality. Experiment with the order of the sentences and paragraphs for heightened effect.

Expert Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ Jake Adams. Academic Tutor & Test Prep Specialist. Expert Interview. 20 May 2020.

- ↑ http://www.writing.utoronto.ca/advice/planning-and-organizing/organizing

- ↑ http://writingcenter.unc.edu/handouts/understanding-assignments/

- ↑ https://open.lib.umn.edu/writingforsuccess/chapter/6-1-purpose-audience-tone-and-content/

- ↑ https://www.student.unsw.edu.au/writing-your-essay

- ↑ https://www.hamilton.edu/writing/writing-resources/persuasive-essays

- ↑ http://writingcenter.unc.edu/handouts/thesis-statements/

- ↑ http://writingcenter.unc.edu/handouts/brainstorming/

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/engagement/2/2/53/

- ↑ https://pressbooks.library.torontomu.ca/scholarlywriting/chapter/revising-a-thesis-statement/

- ↑ http://writingcenter.unc.edu/handouts/reorganizing-drafts/

- ↑ https://www.grammarly.com/blog/essay-outline/

- ↑ https://wts.indiana.edu/writing-guides/paragraphs-and-topic-sentences.html

- ↑ http://writingcenter.unc.edu/handouts/transitions/

- ↑ https://writing.wisc.edu/Handbook/Transitions.html

- ↑ http://writingcenter.unc.edu/handouts/conclusions/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/reading-aloud/

About This Article

To organize an essay, start by writing a thesis statement that makes a unique observation about your topic. Then, write down each of the points you want to make that support your thesis statement. Once you have all of your main points, expand them into paragraphs using the information you found during your research. Finally, close your essay with a conclusion that reiterates your thesis statement and offers additional insight into why it’s important. For tips from our English reviewer on how to use transitional sentences to help your essay flow better, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Roxana Salgado

Dec 6, 2016

Did this article help you?

Jacky Tormo

Jul 22, 2016

Rosalba Ramirez

Feb 2, 2017

Gulshan Kumar Singh

Sep 4, 2016

Nov 30, 2016

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

4.3 Organizing Your Writing

Learning objectives.

- Understand how and why organizational techniques help writers and readers stay focused.

- Assess how and when to use chronological order to organize an essay.

- Recognize how and when to use order of importance to organize an essay.

- Determine how and when to use spatial order to organize an essay.

The method of organization you choose for your essay is just as important as its content. Without a clear organizational pattern, your reader could become confused and lose interest. The way you structure your essay helps your readers draw connections between the body and the thesis, and the structure also keeps you focused as you plan and write the essay. Choosing your organizational pattern before you outline ensures that each body paragraph works to support and develop your thesis.

This section covers three ways to organize body paragraphs:

- Chronological order

- Order of importance

- Spatial order

When you begin to draft your essay, your ideas may seem to flow from your mind in a seemingly random manner. Your readers, who bring to the table different backgrounds, viewpoints, and ideas, need you to clearly organize these ideas in order to help process and accept them.

A solid organizational pattern gives your ideas a path that you can follow as you develop your draft. Knowing how you will organize your paragraphs allows you to better express and analyze your thoughts. Planning the structure of your essay before you choose supporting evidence helps you conduct more effective and targeted research.

Chronological Order

In Chapter 3: The Writing Process: Where Do I Begin? Section Overview , you learned that chronological arrangement has the following purposes:

- To explain the history of an event or a topic

- To tell a story or relate an experience

- To explain how to do or to make something

- To explain the steps in a process

Chronological order is mostly used in expository writing , which is a form of writing that narrates, describes, informs, or explains a process. When using chronological order, arrange the events in the order that they actually happened, or will happen if you are giving instructions. This method requires you to use words such as first , second , then , after that , later , and finally . These transition words guide you and your reader through the paper as you expand your thesis.

For example, if you are writing an essay about the history of the airline industry, you would begin with its conception and detail the essential timeline events up until present day. You would follow the chain of events using words such as first , then , next , and so on.

Connecting the Pieces: Writing at Work

At some point in your career you may have to file a complaint with your human resources department. Using chronological order is a useful tool in describing the events that led up to your filing the grievance. You would logically lay out the events in the order that they occurred using the key transition words. The more logical your complaint, the more likely you will be well received and helped.

Choose an accomplishment you have achieved in your life. The important moment could be in sports, schooling, or extracurricular activities. On your own sheet of paper, list the steps you took to reach your goal. Try to be as specific as possible with the steps you took. Pay attention to using transition words to focus your writing.

Keep in mind that chronological order is most appropriate for the following purposes:

- Writing essays containing heavy research

- Writing essays with the aim of listing, explaining, or narrating

- Writing essays that analyze literary works such as poems, plays, or books

When using chronological order, your introduction should indicate the information you will cover and in what order, and the introduction should also establish the relevance of the information. Your body paragraphs should then provide clear divisions or steps in chronology. You can divide your paragraphs by time (such as decades, wars, or other historical events) or by the same structure of the work you are examining (such as a line-by-line explication of a poem).

On a separate sheet of paper, write a paragraph that describes a process you are familiar with and can do well. Assume that your reader is unfamiliar with the procedure. Remember to use the chronological key words, such as first , second , then , and finally .

Order of Importance

Recall from Chapter 3: The Writing Process: Where Do I Begin? that order of importance is best used for the following purposes:

- Persuading and convincing

- Ranking items by their importance, benefit, or significance

- Illustrating a situation, problem, or solution

Most essays move from the least to the most important point, and the paragraphs are arranged in an effort to build the essay’s strength. Sometimes, however, it is necessary to begin with your most important supporting point, such as in an essay that contains a thesis that is highly debatable. When writing a persuasive essay, it is best to begin with the most important point because it immediately captivates your readers and compels them to continue reading.

For example, if you were supporting your thesis that homework is detrimental to the education of high school students, you would want to present your most convincing argument first, and then move on to the less important points for your case.

Some key transitional words you should use with this method of organization are most importantly , almost as importantly , just as importantly , and finally .

During your career, you may be required to work on a team that devises a strategy for a specific goal of your company, such as increasing profits. When planning your strategy you should organize your steps in order of importance. This demonstrates the ability to prioritize and plan. Using the order of importance technique also shows that you can create a resolution with logical steps for accomplishing a common goal.

On a separate sheet of paper, write a paragraph that discusses a passion of yours. Your passion could be music, a particular sport, filmmaking, and so on. Your paragraph should be built upon the reasons why you feel so strongly. Briefly discuss your reasons in the order of least to greatest importance.

Spatial Order

As stated in Chapter 3: The Writing Process: Where Do I Begin? , spatial order is best used for the following purposes:

- Helping readers visualize something as you want them to see it

- Evoking a scene using the senses (sight, touch, taste, smell, and sound)

- Writing a descriptive essay

Spatial order means that you explain or describe objects as they are arranged around you in your space, for example in a bedroom. As the writer, you create a picture for your reader, and their perspective is the viewpoint from which you describe what is around you.

The view must move in an orderly, logical progression, giving the reader clear directional signals to follow from place to place. The key to using this method is to choose a specific starting point and then guide the reader to follow your eye as it moves in an orderly trajectory from your starting point.

Pay attention to the following student’s description of her bedroom and how she guides the reader through the viewing process, foot by foot.

Attached to my bedroom wall is a small wooden rack dangling with red and turquoise necklaces that shimmer as you enter. Just to the right of the rack is my window, framed by billowy white curtains. The peace of such an image is a stark contrast to my desk, which sits to the right of the window, layered in textbooks, crumpled papers, coffee cups, and an overflowing ashtray. Turning my head to the right, I see a set of two bare windows that frame the trees outside the glass like a 3D painting. Below the windows is an oak chest from which blankets and scarves are protruding. Against the wall opposite the billowy curtains is an antique dresser, on top of which sits a jewelry box and a few picture frames. A tall mirror attached to the dresser takes up most of the wall, which is the color of lavender.

The paragraph incorporates two objectives you have learned in this chapter: using an implied topic sentence and applying spatial order. Often in a descriptive essay, the two work together.

The following are possible transition words to include when using spatial order:

- Just to the left or just to the right

- On the left or on the right

- Across from

- A little further down

- To the south, to the east, and so on

- A few yards away

- Turning left or turning right

On a separate sheet of paper, write a paragraph using spatial order that describes your commute to work, school, or another location you visit often.

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

Key Takeaways

- The way you organize your body paragraphs ensures you and your readers stay focused on and draw connections to, your thesis statement.

- A strong organizational pattern allows you to articulate, analyze, and clarify your thoughts.

- Planning the organizational structure for your essay before you begin to search for supporting evidence helps you conduct more effective and directed research.

- Chronological order is most commonly used in expository writing. It is useful for explaining the history of your subject, for telling a story, or for explaining a process.

- Order of importance is most appropriate in a persuasion paper as well as for essays in which you rank things, people, or events by their significance.

- Spatial order describes things as they are arranged in space and is best for helping readers visualize something as you want them to see it; it creates a dominant impression.

Putting the Pieces Together Copyright © 2020 by Andrew Stracuzzi and André Cormier is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Organization and Structure

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

There is no single organizational pattern that works well for all writing across all disciplines; rather, organization depends on what you’re writing, who you’re writing it for, and where your writing will be read. In order to communicate your ideas, you’ll need to use a logical and consistent organizational structure in all of your writing. We can think about organization at the global level (your entire paper or project) as well as at the local level (a chapter, section, or paragraph). For an American academic situation, this means that at all times, the goal of revising for organization and structure is to consciously design your writing projects to make them easy for readers to understand. In this context, you as the writer are always responsible for the reader's ability to understand your work; in other words, American academic writing is writer-responsible. A good goal is to make your writing accessible and comprehensible to someone who just reads sections of your writing rather than the entire piece. This handout provides strategies for revising your writing to help meet this goal.

Note that this resource focuses on writing for an American academic setting, specifically for graduate students. American academic writing is of course not the only standard for academic writing, and researchers around the globe will have different expectations for organization and structure. The OWL has some more resources about writing for American and international audiences here .

Whole-Essay Structure

While organization varies across and within disciplines, usually based on the genre, publication venue, and other rhetorical considerations of the writing, a great deal of academic writing can be described by the acronym IMRAD (or IMRaD): Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion. This structure is common across most of the sciences and is often used in the humanities for empirical research. This structure doesn't serve every purpose (for instance, it may be difficult to follow IMRAD in a proposal for a future study or in more exploratory writing in the humanities), and it is often tweaked or changed to fit a particular situation. Still, its wide use as a base for a great deal of scholarly writing makes it worthwhile to break down here.

- Introduction : What is the purpose of the study? What were the research questions? What necessary background information should the reader understand to help contextualize the study? (Some disciplines include their literature review section as part of the introduction; some give the literature review its own heading on the same level as the other sections, i.e., ILMRAD.) Some writers use the CARS model to help craft their introductions more effectively.

- Methods: What methods did the researchers use? How was the study conducted? If the study included participants, who were they, and how were they selected?

- Results : This section lists the data. What did the researchers find as a result of their experiments (or, if the research is not experimental, what did the researchers learn from the study)? How were the research questions answered?

- Discussion : This section places the data within the larger conversation of the field. What might the results mean? Do these results agree or disagree with other literature cited? What should researchers do in the future?

Depending on your discipline, this may be exactly the structure you should use in your writing; or, it may be a base that you can see under the surface of published pieces in your field, which then diverge from the IMRAD structure to meet the expectations of other scholars in the field. However, you should always check to see what's expected of you in a given situation; this might mean talking to the professor for your class, looking at a journal's submission guidelines, reading your field's style manual, examining published examples, or asking a trusted mentor. Every field is a little different.

Outlining & Reverse Outlining

One of the most effective ways to get your ideas organized is to write an outline. A traditional outline comes as the pre-writing or drafting stage of the writing process. As you make your outline, think about all of the concepts, topics, and ideas you will need to include in order to accomplish your goal for the piece of writing. This may also include important citations and key terms. Write down each of these, and then consider what information readers will need to know in order for each point to make sense. Try to arrange your ideas in a way that logically progresses, building from one key idea or point to the next.

Questions for Writing Outlines

- What are the main points I am trying to make in this piece of writing?

- What background information will my readers need to understand each point? What will novice readers vs. experienced readers need to know?

- In what order do I want to present my ideas? Most important to least important, or least important to most important? Chronologically? Most complex to least complex? According to categories? Another order?

Reverse outlining comes at the drafting or revision stage of the writing process. After you have a complete draft of your project (or a section of your project), work alone or with a partner to read your project with the goal of understanding the main points you have made and the relationship of these points to one another. The OWL has another resource about reverse outlining here.

Questions for Writing Reverse Outlines

- What topics are covered in this piece of writing?

- In what order are the ideas presented? Is this order logical for both novice and experienced readers?

- Is adequate background information provided for each point, making it easy to understand how one idea leads to the next?

- What other points might the author include to further develop the writing project?

Organizing at the sentence and paragraph level

Signposting.

Signposting is the practice of using language specifically designed to help orient readers of your text. We call it signposting because this practice is like leaving road signs for a driver — it tells your reader where to go and what to expect up ahead. Signposting includes the use of transitional words and phrasing, and they may be explicit or more subtle. For example, an explicit signpost might say:

This section will cover Topic A and Topic B.

A more subtle signpost might look like this:

It's important to consider the impact of Topic A and Topic B.

The style of signpost you use will depend on the genre of your paper, the discipline in which you are writing, and your or your readers’ personal preferences. Regardless of the style of signpost you select, it’s important to include signposts regularly. They occur most frequently at the beginnings and endings of sections of your paper. It is often helpful to include signposts at mid-points in your project in order to remind readers of where you are in your argument.

Questions for Identifying and Evaluating Signposts

- How and where does the author include a phrase, sentence, or short group of sentences that explains the purpose and contents of the paper?

- How does each section of the paper provide a brief summary of what was covered earlier in the paper?

- How does each section of the paper explain what will be covered in that section?

- How does the author use transitional words and phrases to guide readers through ideas (e.g. however, in addition, similarly, nevertheless, another, while, because, first, second, next, then etc.)?

WORKS CONSULTED

Clark, I. (2006). Writing the successful thesis and dissertation: Entering the conversation . Prentice Hall Press.

Davis, M., Davis, K. J., & Dunagan, M. (2012). Scientific papers and presentations . Academic press.

Skip to content. | Skip to navigation

Masterlinks

- About Hunter

- One Stop for Students

- Make a Gift

- Access the Student Guide

- Apply to Become a Peer Tutor

- Access the Faculty Guide

- Request a Classroom Visit

- Refer a Student to the Center

- Request a Classroom Workshop

- The Writing Process

- The Documented Essay/Research Paper

- Writing for English Courses

- Writing Across the Curriculum

- Grammar and Mechanics

- Business and Professional Writing

- CUNY TESTING

- | Workshops

- Research Information and Resources

- Evaluating Information Sources

- Writing Tools and References

- Reading Room

- Literary Resources

- ESL Resources for Students

- ESL Resources for Faculty

- Teaching and Learning

- | Contact Us

Many types of writing follow some version of the basic shape described above. This shape is most obvious in the form of the traditional five-paragraph essay: a model for college writing in which the writer argues his or her viewpoint (thesis) on a topic and uses three reasons or subtopics to support that position. In the five-paragraph model, as illustrated below, the introductory paragraph mentions the three main points or subtopics, and each body paragraph begins with a topic sentence dealing with one of those main points.

SAMPLE ESSAY USING THE FIVE-PARAGRAPH MODEL

Remember, this is a very simplistic model. It presents a basic idea of essay organization and may certainly be helpful in learning to structure an argument, but it should not be followed religiously as an ideal form.

Document Actions

- Public Safety

- Website Feedback

- Privacy Policy

- CUNY Tobacco Policy

Organizing Your Writing

Writing for Success

Learning Objectives

- Understand how and why organizational techniques help writers and readers stay focused.

- Assess how and when to use chronological order to organize an essay.

- Recognize how and when to use order of importance to organize an essay.

- Determine how and when to use spatial order to organize an essay.

The method of organization you choose for your essay is just as important as its content. Without a clear organizational pattern, your reader could become confused and lose interest. The way you structure your essay helps your readers draw connections between the body and the thesis, and the structure also keeps you focused as you plan and write the essay. Choosing your organizational pattern before you outline ensures that each body paragraph works to support and develop your thesis.

This section covers three ways to organize body paragraphs:

- Chronological order

- Order of importance

- Spatial order

When you begin to draft your essay, your ideas may seem to flow from your mind in a seemingly random manner. Your readers, who bring to the table different backgrounds, viewpoints, and ideas, need you to clearly organize these ideas in order to help process and accept them.

A solid organizational pattern gives your ideas a path that you can follow as you develop your draft. Knowing how you will organize your paragraphs allows you to better express and analyze your thoughts. Planning the structure of your essay before you choose supporting evidence helps you conduct more effective and targeted research.

CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER

Chronological arrangement (also called “time order,”) has the following purposes:

- To explain the history of an event or a topic

- To tell a story or relate an experience

- To explain how to do or to make something

- To explain the steps in a process

Chronological order is mostly used in expository writing, which is a form of writing that narrates, describes, informs, or explains a process. When using chronological order, arrange the events in the order that they actually happened, or will happen if you are giving instructions. This method requires you to use words such as first, second, then, after that, later, and finally. These transition words guide you and your reader through the paper as you expand your thesis.

For example, if you are writing an essay about the history of the airline industry, you would begin with its conception and detail the essential timeline events up until present day. You would follow the chain of events using words such as first, then, next, and so on.

WRITING AT WORK

At some point in your career you may have to file a complaint with your human resources department. Using chronological order is a useful tool in describing the events that led up to your filing the grievance. You would logically lay out the events in the order that they occurred using the key transition words. The more logical your complaint, the more likely you will be well received and helped.

Choose an accomplishment you have achieved in your life. The important moment could be in sports, schooling, or extracurricular activities. On your own sheet of paper, list the steps you took to reach your goal. Try to be as specific as possible with the steps you took. Pay attention to using transition words to focus your writing.

Keep in mind that chronological order is most appropriate for the following purposes:

- Writing essays containing heavy research

- Writing essays with the aim of listing, explaining, or narrating

- Writing essays that analyze literary works such as poems, plays, or books

When using chronological order, your introduction should indicate the information you will cover and in what order, and the introduction should also establish the relevance of the information. Your body paragraphs should then provide clear divisions or steps in chronology. You can divide your paragraphs by time (such as decades, wars, or other historical events) or by the same structure of the work you are examining (such as a line-by-line explication of a poem).

On a separate sheet of paper, write a paragraph that describes a process you are familiar with and can do well. Assume that your reader is unfamiliar with the procedure. Remember to use the chronological key words, such as first, second, then, and finally.

ORDER OF IMPORTANCE

Order of importance is best used for the following purposes:

- Persuading and convincing

- Ranking items by their importance, benefit, or significance

- Illustrating a situation, problem, or solution

Most essays move from the least to the most important point, and the paragraphs are arranged in an effort to build the essay’s strength. Sometimes, however, it is necessary to begin with your most important supporting point, such as in an essay that contains a thesis that is highly debatable. When writing a persuasive essay, it is best to begin with the most important point because it immediately captivates your readers and compels them to continue reading.

For example, if you were supporting your thesis that homework is detrimental to the education of high school students, you would want to present your most convincing argument first, and then move on to the less important points for your case.

Some key transitional words you should use with this method of organization are most importantly, almost as importantly, just as importantly, and finally.

During your career, you may be required to work on a team that devises a strategy for a specific goal of your company, such as increasing profits. When planning your strategy you should organize your steps in order of importance. This demonstrates the ability to prioritize and plan. Using the order of importance technique also shows that you can create a resolution with logical steps for accomplishing a common goal.

On a separate sheet of paper, write a paragraph that discusses a passion of yours. Your passion could be music, a particular sport, filmmaking, and so on. Your paragraph should be built upon the reasons why you feel so strongly. Briefly discuss your reasons in the order of least to greatest importance.

SPATIAL ORDER

Spatial order is best used for the following purposes:

- Helping readers visualize something as you want them to see it

- Evoking a scene using the senses (sight, touch, taste, smell, and sound)

- Writing a descriptive essay

Spatial order means that you explain or describe objects as they are arranged around you in your space, for example in a bedroom. As the writer, you create a picture for your reader, and their perspective is the viewpoint from which you describe what is around you.

The view must move in an orderly, logical progression, giving the reader clear directional signals to follow from place to place. The key to using this method is to choose a specific starting point and then guide the reader to follow your eye as it moves in an orderly trajectory from your starting point.

Pay attention to the following student’s description of her bedroom and how she guides the reader through the viewing process, foot by foot.

The paragraph incorporates two objectives you have learned in this chapter: using an implied topic sentence and applying spatial order. Often in a descriptive essay, the two work together.

The following are possible transition words to include when using spatial order:

- Just to the left or just to the right

- On the left or on the right

- Across from

- A little further down

- To the south, to the east, and so on

- A few yards away

- Turning left or turning right

Key Takeaways

- The way you organize your body paragraphs ensures you and your readers stay focused on and draw connections to, your thesis statement.

- A strong organizational pattern allows you to articulate, analyze, and clarify your thoughts.

- Planning the organizational structure for your essay before you begin to search for supporting evidence helps you conduct more effective and directed research.

- Chronological order is most commonly used in expository writing. It is useful for explaining the history of your subject, for telling a story, or for explaining a process.

- Order of importance is most appropriate in a persuasion paper as well as for essays in which you rank things, people, or events by their significance.

- Spatial order describes things as they are arranged in space and is best for helping readers visualize something as you want them to see it; it creates a dominant impression.

Organizing Your Writing Copyright © 2016 by Writing for Success is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Feedback/errata.

Comments are closed.

- How it works

How to Organise an Essay – A Comprehensive Guide & Examples

Published by Grace Graffin at August 17th, 2021 , Revised On October 11, 2023

The quality of a well-written essay largely depends on the quality of the content and the author’s writing style. Students with little to no essay writing experience almost always struggle to figure out how to organise an essay.

Even if you have great essay writing skills but are unable to keep the sequence of information right in your essay, you may not impress the readers.

A narrator cannot craft an engaging story until he learns to organise his vivid thoughts. The best way to organise an essay is to create a map of the essay beforehand to ensure that your essay’s structure allows for a smooth flow of information.

Here is all you need to learn in order to organise an essay.

The Importance of Organisation of an Essay

Readers are always looking for an essay that is easy in its approach, i.e. an essay that is reader-friendly and follows an easy-to-understand structure, etc.

Your essay should be organised to convey a clear message to the reader without using any vague statements. As an essayist, it will be your responsibility to make sure that there are no spelling, grammar, capitalization, and punctuation errors in the essay paper.

You might wonder why you need to put increased effort into the organisation of an essay. If you had the opportunity to work with a professional essayist or any other individual working in English literature, you would get to know that each of these professionals pays a lot of attention to organising an essay because a poorly structured essay can really turn away your readers.

Basic Essay Organisation

The first things to organise are what you are going to say and in what order you are going to say those things. After this, it is a case of refining those things. You can start by separating all your text into three sections: introduction , main body , and conclusion . Can it really be so simple? Yes, and of course, no. There are several ways to organise an essay depending on different factors.

Different Patterns for the Organisation of an Essay

There is no specific way of organising an essay. Multiple styles and methods are utilised by writers based on the academic subject, academic level, and expectations of the audience. Below we have discussed some of the most common ways to organise an essay.

Chronological Organisation

Organising an essay chronologically – sometimes called the cause-and-effect approach – is one of the simpler ways to organise your essay. This way of organisation tends to discuss the events in the specific order they occurred. The chronological organisation method is especially important for narrative and reflective essays .

The writer will be expected to recognise the sequence of events and structure the essay accordingly, i.e. what happens in the beginning, middle, and at end. Use this approach if it allows for the clearest and most logical presentation of your information.

Where is Chronological Organisation Used?

- Scientific processes – Where a process has many steps, it is likely that the order of these steps is vital.

- Historical events – Things are clearer for the reader when events in the past are relayed in the order in which they happened. This can also apply to political progress.

- Biographies – Events that occurred in someone’s lifetime or examining events covering just a short time in one person’s life, such as a JFK’s final day.

Specific Language Needed

Essays that describe a succession of events following each other will require good use of prepositions of time. These are words, often pairs, such as next, after this/that, following on from that, later… Be careful not to overuse the same word, as this can become repetitive and tedious for the reader.

Spatial Organisation

The spatial organisation refers to describing items based on their physical locations or relation to other items. It often involves describing things as and when they appear. It makes it easier for the writer to give a vivid picture through the essay. This method tends to discuss comparisons, narrations, and descriptions .

When using this technique, make sure to organise the information pertaining to comparisons, narrations, and descriptions from either top to bottom or left to right. Note that while location and position are very important with this method, time is largely ignored.

Where is Spatial Organisation Used?

- Descriptive essays – It is excellent for describing objects, people, and places. It is also useful for showing social or physical phenomena – the arrangement of a rainforest.

- Narrating events – You can take the reader through a visual processor to describe events that occurred, showing them everything on the way.

- Medical – Those who need to describe the workings of bodies, medicines, operations on bodies, and anatomy might choose this approach.

- Technical construction – You can describe how a physical mechanism or building works or is constructed.

If you do not have a picture to show, you need to describe it.

For instance, if you are writing an essay about a brand-new, impressively featured smartphone, you can begin to brief about the smartphone starting from the top camera down to the buttons located at the bottom .

From the example above, you can see that an essay using spatial organisation will require you to talk about where things are. This will mean quite extensive and careful use of a group of words called prepositions , such as next to, attached to, near, behind, under, alongside… If you are describing movement, then there are prepositions that indicate movement, such as through, into, out of, toward, away from, and past.

You need to be specific in your use of prepositions as the reader might be imagining events with no image to refer to other than what you have described.

Climactic Order

This method is also known as organising by importance or ascending order. Following this technique, the writer starts the essay with the least important information and gradually moves towards the most important – the climax. The idea is to save the best till the last.

The introduction and conclusion are unaffected by this organisational style. The main body of the essay is where the structure is used. This type of organisation is applicable where there is no need for logical ordering. For example, in a scientific process, each step logically follows the previous one. Steps will vary in how eventful they are; you cannot write about such a process by saving the most eventful for the end.

When to Use Climactic Order

This method is sometimes used as a way of keeping readers interested, even in suspense. If written in the opposite direction, anticlimactic, you might lose readers after they have learned about the most exciting part.

In narrating a story or sequence of events that culminate in something serious or important, this is a good style to use.

Interested in ordering an essay?

Topical Organisation

As the name itself suggests, this form of organisation explains different features and sides of the topic with no specific order. Unlike climactic order, this type of essay organisation treats different aspects of one topic with the same importance. The way to achieve this is to divide the whole topic up into its subtopics and then define each one.

Where is Topical Organisation Used?

- Scientific essays – This could be an exploratory essay, especially where an organism or something consisting of multiple parts has to be described.

- Compare-and-contrast essays – Where things have to be compared against each other for their similarities and differences. This could be when comparing two pieces of art or literature; the works’ various aspects could be examined separately.

- Descriptive essays – If, for example, you have to write an essay about yourself, you can describe the different aspects of your body and personality in their own sections.

- Expository essays – Where something is explained with facts, not opinions, the subject can be broken down and looked at piece by piece.

For example , describing how information technology has had serious consequences on mankind can start with how people overlooked technology in the beginning. It could then discuss the causes of social media addiction that have taken the world by storm in recent times.

Comparing and Contrasting: Alternating and Block Methods

It is worth noting that compare-and-contrast essays can be structured in two distinct ways. They are the alternating method, where each part is compared in turn, and the block method, where each thing is considered in its entirety.

Using the alternating method to compare two cars, you might compare the bodywork of both, then move on to their interiors, and then the engines. The other way is the block method; here, you would write a full block discussing all aspects of one car and then a block discussing the same aspects of the other car.

Also Read: How to Develop Essay Topic Ideas

Stuck on a difficult essay? We can help!

Our Essay Writing Service Features:

- Expert UK Writers

- Plagiarism-free

- Timely Delivery

- Thorough Research

- Rigorous Quality Control

Key Tips for Organising your Essay

Planning and organising your essay not only benefit the reader, but the writer also gets great help from the whole process. Following organisational patterns helps the writer by saving time without having to go through the same content repeatedly.

If you plan to develop a great essay , you must ensure good planning for your essay. Using the correct format to present your material will complement the material itself. Let’s discuss some key tips on how to organise an essay:

Also Read: Organisational Templates for Essays

Start your Essay with Simple Arguments

A good tactic in producing an organised essay is to start your essay by providing simple arguments. It does not mean that only simple arguments should be part of the essay. Relatively complex or difficult arguments should also be placed later in the main body of the essay .

If your readers can understand the most basic arguments, they will be more likely to grasp the message resulting from more complicated arguments and statements.

This further relates to the point that if you start your essay with simple information that your readers can agree to without much hesitation, you will be more likely to convince them to agree to more controversial arguments.

Get the Readers on your Side

As an example, by presenting a simple, well-understood scientific argument early on, you start to get your readers on board. You then present another argument that can be seen as a logical progression from the first. When you raise a more complex and possibly contentious argument, it helps if you can apply principles from your initial example. If the readers agreed with the basic argument, logically they would agree with the more complex version.

This early presentation of a simpler argument ties in with giving your audience background information early in the essay. While you might assume your readers understand the subject you are writing about, you should not skip background information by assuming they will know it.

Know your Audience

In this era of technological advancement, people tend to make quick decisions as they have to look at multiple platforms to find content. Understandably, the essay needs to be well structured and well formalised, yet it should be organised in a way that is user-friendly. If the audience you are going to target is not going to be enticed by it, you need to reconsider your approach and tactics.

Define Technical Terms

While providing information in the essay, make sure that you define all the technical terms that the readers may not be aware of. This needs to be done as the first step before you alienate and confuse your reader and he decides to avert.

It would be best if you drafted your essay in such a manner that a layperson can understand it without making any extra effort. Jargon or technical terms must be defined within the content.

If used excessively, you can describe these terms in a different paragraph, making it more convenient for the readers.

How can ResearchProspect Help?

Still unsure about how to organise an essay?

Have you put so much effort into your essay, but still, it doesn’t seem like what it should be? Well, you need not worry because our professional writers can design and structure an essay exactly the way it is supposed to be. If you are looking for an organised and presentable essay, please take advantage of our professional essay writing service .

Want to Know About Our Services? Place Your Order Now Essay Writing Samples

Frequently Asked Questions

What is an essay structure.

The structure of an essay is the way in which you present your material. This mostly applies to the main body of your essay. You can consider the introduction and conclusion parts as bookends that hold the main block of information in place. There are several ways to organise the main body, and they mostly depend on what kind of material you are presenting. Certain types of essays benefit from certain ways of delivering the information within.

An appropriately structured essay gives your arguments and ideas their best chance. When the correct structure is supported by well-written paragraphs and good use of transitions , it will be an impressive essay to read.

Is referencing affected by the essay style I choose?

No, the approach you take in organising your essay does not affect how you reference your sources. What affects your referencing is the formatting style you are instructed to use, such as Harvard , APA, MLA, or Chicago.

Are there fixed rules on which method of organising to use for certain subjects?

No, there is no rule that says you have to use a certain style. However, practice shows that the aims of certain types of essays are best achieved when presented in particular styles.

Do I have to provide a glossary of technical terms?

How you define technical terms to your readers is your choice. It can depend on the amount of them. If there are not many, they can be introduced within the text. If the essay topic is of a highly technical nature, then a separate sheet with definitions might be the best way to explain them without extending the length of your essay .

You May Also Like

A good essay introduction will set the tone for succeeding parts. Unsure about how to write an essay introduction? This guide will help you to get going.

This article aims to provide you to understand the concept of descriptive and narrative essay style along with the necessary tips required for these essays.

The length of an academic essay depends on your level and the nature of subject. If you are unsure how long is an essay then this article will guide you.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

- Writing Home

- Writing Advice Home

Organizing an Essay

- Printable PDF Version

- Fair-Use Policy

Some basic guidelines

The best time to think about how to organize your paper is during the pre-writing stage, not the writing or revising stage. A well-thought-out plan can save you from having to do a lot of reorganizing when the first draft is completed. Moreover, it allows you to pay more attention to sentence-level issues when you sit down to write your paper.

When you begin planning, ask the following questions: What type of essay am I going to be writing? Does it belong to a specific genre? In university, you may be asked to write, say, a book review, a lab report, a document study, or a compare-and-contrast essay. Knowing the patterns of reasoning associated with a genre can help you to structure your essay.

For example, book reviews typically begin with a summary of the book you’re reviewing. They then often move on to a critical discussion of the book’s strengths and weaknesses. They may conclude with an overall assessment of the value of the book. These typical features of a book review lead you to consider dividing your outline into three parts: (1) summary; (2) discussion of strengths and weaknesses; (3) overall evaluation. The second and most substantial part will likely break down into two sub-parts. It is up to you to decide the order of the two subparts—whether to analyze strengths or weaknesses first. And of course it will be up to you to come up with actual strengths and weaknesses.

Be aware that genres are not fixed. Different professors will define the features of a genre differently. Read the assignment question carefully for guidance.

Understanding genre can take you only so far. Most university essays are argumentative, and there is no set pattern for the shape of an argumentative essay. The simple three-point essay taught in high school is far too restrictive for the complexities of most university assignments. You must be ready to come up with whatever essay structure helps you to convince your reader of the validity of your position. In other words, you must be flexible, and you must rely on your wits. Each essay presents a fresh problem.

Avoiding a common pitfall

Though there are no easy formulas for generating an outline, you can avoid one of the most common pitfalls in student papers by remembering this simple principle: the structure of an essay should not be determined by the structure of its source material. For example, an essay on an historical period should not necessarily follow the chronology of events from that period. Similarly, a well-constructed essay about a literary work does not usually progress in parallel with the plot. Your obligation is to advance your argument, not to reproduce the plot.

If your essay is not well structured, then its overall weaknesses will show through in the individual paragraphs. Consider the following two paragraphs from two different English essays, both arguing that despite Hamlet’s highly developed moral nature he becomes morally compromised in the course of the play:

(a) In Act 3, Scene 4, Polonius hides behind an arras in Gertrude’s chamber in order to spy on Hamlet at the bidding of the king. Detecting something stirring, Hamlet draws his sword and kills Polonius, thinking he has killed Claudius. Gertrude exclaims, “O, what a rash and bloody deed is this!” (28), and her words mark the turning point in Hamlet’s moral decline. Now Hamlet has blood on his hands, and the blood of the wrong person. But rather than engage in self-criticism, Hamlet immediately turns his mother’s words against her: “A bloody deed — almost as bad, good Mother, as kill a king, and marry with his brother” (29-30). One of Hamlet’s most serious shortcomings is his unfair treatment of women. He often accuses them of sins they could not have committed. It is doubtful that Gertrude even knows Claudius killed her previous husband. Hamlet goes on to ask Gertrude to compare the image of the two kings, old Hamlet and Claudius. In Hamlet’s words, old Hamlet has “Hyperion’s curls,” the front of Jove,” and “an eye like Mars” (57-58). Despite Hamlet’s unfair treatment of women, he is motivated by one of his better qualities: his idealism. (b) One of Hamlet’s most serious moral shortcomings is his unfair treatment of women. In Act 3, Scene 1, he denies to Ophelia ever having expressed his love for her, using his feigned madness as cover for his cruelty. Though his rantings may be an act, they cannot hide his obsessive anger at one particular woman: his mother. He counsels Ophelia to “marry a fool, for wise men know well enough what monsters you make of them” (139-41), thus blaming her in advance for the sin of adultery. The logic is plain: if Hamlet’s mother made a cuckold out of Hamlet’s father, then all women are capable of doing the same and therefore share the blame. The fact that Gertrude’s hasty remarriage does not actually constitute adultery only underscores Hamlet’s tendency to find in women faults that do not exist. In Act 3, Scene 4, he goes as far as to suggest that Gertrude shared responsibility in the murder of Hamlet’s father (29-30). By condemning women for actions they did not commit, Hamlet is doing just what he accuses Guildenstern of doing to him: he is plucking out the “heart” of their “mystery” (3.2.372-74).

The second of these two paragraphs is much stronger, largely because it is not plot-driven. It makes a well-defined point about Hamlet’s moral nature and sticks to that point throughout the paragraph. Notice that the paragraph jumps from one scene to another as is necessary, but the logic of the argument moves along a steady path. At any given point in your essays, you will want to leave yourself free to go wherever you need to in your source material. Your only obligation is to further your argument. Paragraph (a) sticks closely to the narrative thread of Act 3, Scene 4, and as a result the paragraph makes several different points with no clear focus.

What does an essay outline look like?

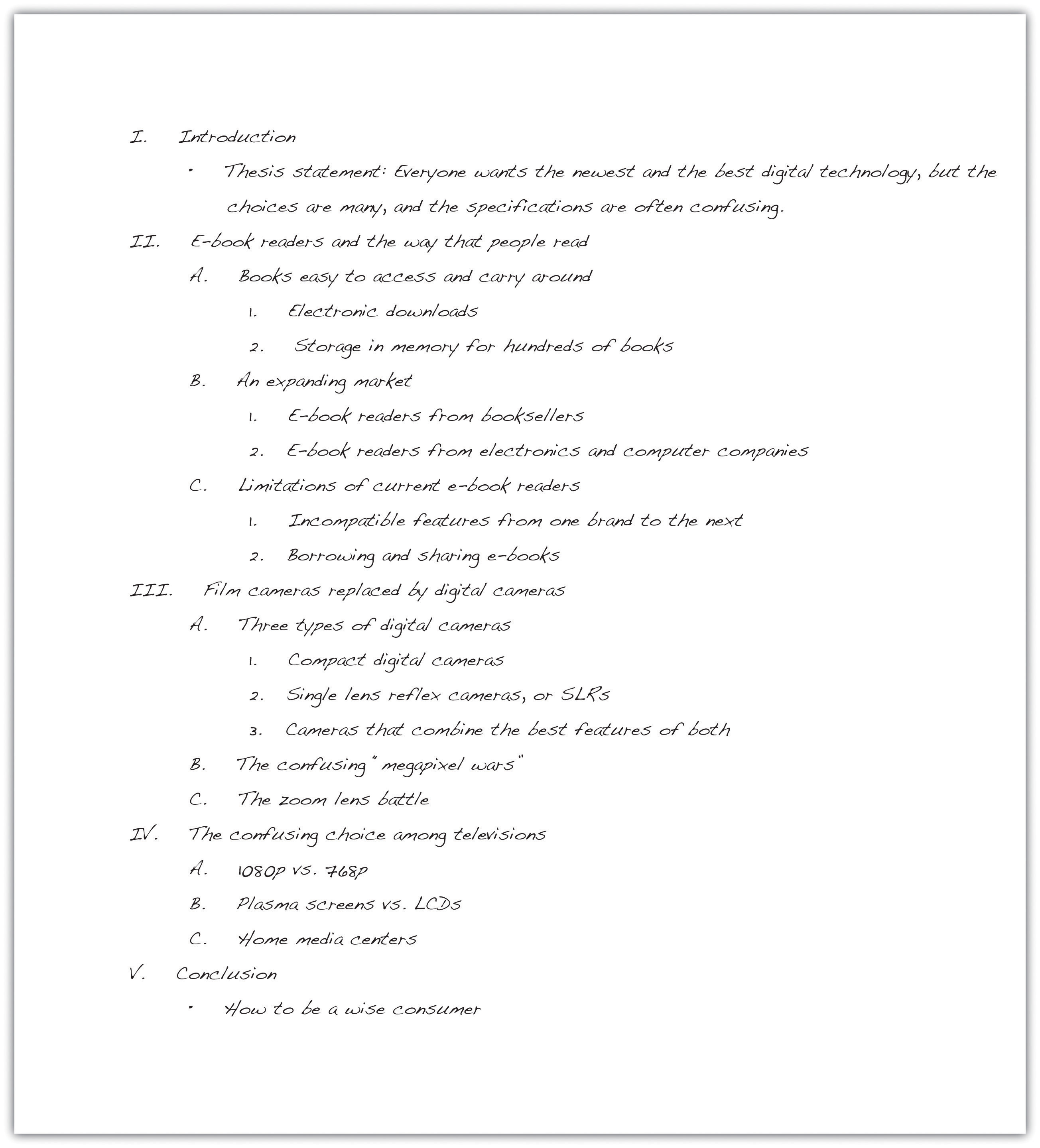

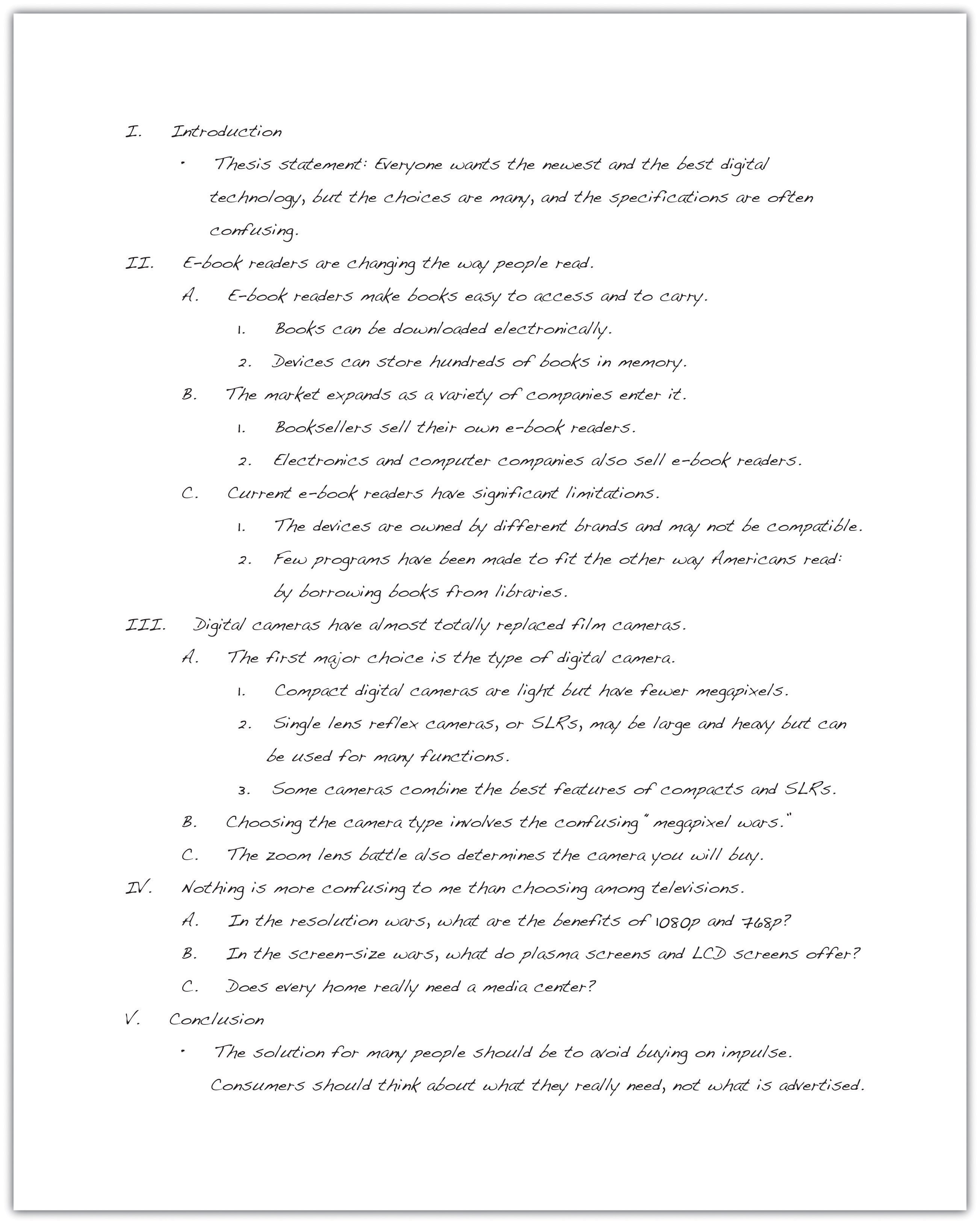

Most essay outlines will never be handed in. They are meant to serve you and no one else. Occasionally, your professor will ask you to hand in an outline weeks prior to handing in your paper. Usually, the point is to ensure that you are on the right track. Nevertheless, when you produce your outline, you should follow certain basic principles. Here is an example of an outline for an essay on Hamlet :

This is an example of a sentence outline. Another kind of outline is the topic outline. It consists of fragments rather than full sentences. Topic outlines are more open-ended than sentence outlines: they leave much of the working out of the argument for the writing stage.

When should I begin putting together a plan?

The earlier you begin planning, the better. It is usually a mistake to do all of your research and note-taking before beginning to draw up an outline. Of course, you will have to do some reading and weighing of evidence before you start to plan. But as a potential argument begins to take shape in your mind, you may start to formalize your thoughts in the form of a tentative plan. You will be much more efficient in your reading and your research if you have some idea of where your argument is headed. You can then search for evidence for the points in your tentative plan while you are reading and researching. As you gather evidence, those points that still lack evidence should guide you in your research. Remember, though, that your plan may need to be modified as you critically evaluate your evidence.

How can I construct a usable plan?

Here are two methods for constructing a plan. The first works best on the computer. The second method works well for those who think visually. It is often the method of choice for those who prefer to do some of their thinking with pen and paper, though it can easily be transposed to a word processor or your graphic software of choice.

method 1: hierarchical outline

This method usually begins by taking notes. Start by collecting potential points, as well as useful quotations and paraphrases of quotations, consecutively. As you accumulate notes, identify key points and start to arrange those key points into an outline. To build your outline, take advantage of outline view in Word or numbered lists in Google Docs. Or consider one of the specialized apps designed to help organize ideas: Scrivener, Microsoft OneNote, Workflowy, among others. All these tools make it easy for you to arrange your points hierarchically and to move those points around as you refine your plan.You may, at least initially, keep your notes and your outline separate. But there is no reason for you not to integrate your notes into the plan. Your notes—minor points, quotations, and paraphrases—can all be interwoven into the plan, just below the main points they support. Some of your notes may not find a place in your outline. If so, either modify the plan or leave those points out.

method 2: the circle method

This method is designed to get your key ideas onto a single page, where you can see them all at once. When you have an idea, write it down, and draw a circle around it. When you have an idea that supports another idea, do the same, but connect the two circles with a line. Supporting source material can be represented concisely by a page reference inside a circle. The advantage of the circle method is that you can see at a glance how things tie together; the disadvantage is that there is a limit to how much material you can cram onto a page.

Here is part of a circle diagram

Once you are content with your diagram, you have the option of turning it into an essay outline.

What is a reverse outline?