An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

An Introduction to COVID-19

Simon james fong.

4 Department of Computer and Information Science, University of Macau, Taipa, Macau, China

Nilanjan Dey

5 Department of Information Technology, Techno International New Town, Kolkata, West Bengal India

Jyotismita Chaki

6 School of Information Technology and Engineering, Vellore Institute of Technology, Vellore, Tamil Nadu India

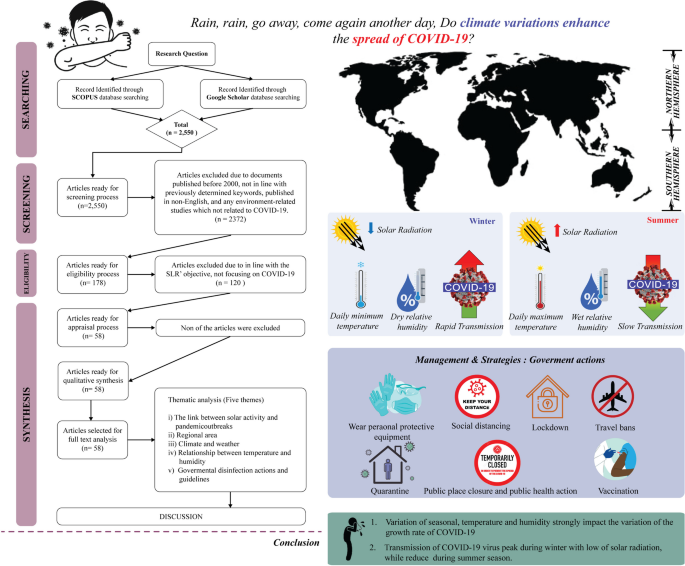

A novel coronavirus (CoV) named ‘2019-nCoV’ or ‘2019 novel coronavirus’ or ‘COVID-19’ by the World Health Organization (WHO) is in charge of the current outbreak of pneumonia that began at the beginning of December 2019 near in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, China [1–4]. COVID-19 is a pathogenic virus. From the phylogenetic analysis carried out with obtainable full genome sequences, bats occur to be the COVID-19 virus reservoir, but the intermediate host(s) has not been detected till now.

A Brief History of the Coronavirus Outbreak

A novel coronavirus (CoV) named ‘2019-nCoV’ or ‘2019 novel coronavirus’ or ‘COVID-19’ by the World Health Organization (WHO) is in charge of the current outbreak of pneumonia that began at the beginning of December 2019 near in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, China [ 1 – 4 ]. COVID-19 is a pathogenic virus. From the phylogenetic analysis carried out with obtainable full genome sequences, bats occur to be the COVID-19 virus reservoir, but the intermediate host(s) has not been detected till now. Though three major areas of work already are ongoing in China to advise our awareness of the pathogenic origin of the outbreak. These include early inquiries of cases with symptoms occurring near in Wuhan during December 2019, ecological sampling from the Huanan Wholesale Seafood Market as well as other area markets, and the collection of detailed reports of the point of origin and type of wildlife species marketed on the Huanan market and the destination of those animals after the market has been closed [ 5 – 8 ].

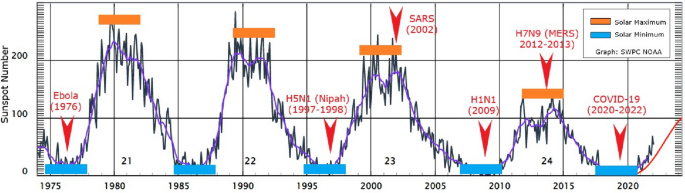

Coronaviruses mostly cause gastrointestinal and respiratory tract infections and are inherently categorized into four major types: Gammacoronavirus, Deltacoronavirus, Betacoronavirus and Alphacoronavirus [ 9 – 11 ]. The first two types mainly infect birds, while the last two mostly infect mammals. Six types of human CoVs have been formally recognized. These comprise HCoVHKU1, HCoV-OC43, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) which is the type of the Betacoronavirus, HCoV229E and HCoV-NL63, which are the member of the Alphacoronavirus. Coronaviruses did not draw global concern until the 2003 SARS pandemic [ 12 – 14 ], preceded by the 2012 MERS [ 15 – 17 ] and most recently by the COVID-19 outbreaks. SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV are known to be extremely pathogenic and spread from bats to palm civets or dromedary camels and eventually to humans.

COVID-19 is spread by dust particles and fomites while close unsafe touch between the infector and the infected individual. Airborne distribution has not been recorded for COVID-19 and is not known to be a significant transmission engine based on empirical evidence; although it can be imagined if such aerosol-generating practices are carried out in medical facilities. Faecal spreading has been seen in certain patients, and the active virus has been reported in a small number of clinical studies [ 18 – 20 ]. Furthermore, the faecal-oral route does not seem to be a COVID-19 transmission engine; its function and relevance for COVID-19 need to be identified.

For about 18,738,58 laboratory-confirmed cases recorded as of 2nd week of April 2020, the maximum number of cases (77.8%) was between 30 and 69 years of age. Among the recorded cases, 21.6% are farmers or employees by profession, 51.1% are male and 77.0% are Hubei.

However, there are already many concerns regarding the latest coronavirus. Although it seems to be transferred to humans by animals, it is important to recognize individual animals and other sources, the path of transmission, the incubation cycle, and the features of the susceptible community and the survival rate. Nonetheless, very little clinical knowledge on COVID-19 disease is currently accessible and details on age span, the animal origin of the virus, incubation time, outbreak curve, viral spectroscopy, dissemination pathogenesis, autopsy observations, and any clinical responses to antivirals are lacking among the serious cases.

How Different and Deadly COVID-19 is Compared to Plagues in History

COVID-19 has reached to more than 150 nations, including China, and has caused WHO to call the disease a worldwide pandemic. By the time of 2nd week of April 2020, this COVID-19 cases exceeded 18,738,58, although more than 1,160,45 deaths were recorded worldwide and United States of America became the global epicentre of coronavirus. More than one-third of the COVID-19 instances are outside of China. Past pandemics that have existed in the past decade or so, like bird flu, swine flu, and SARS, it is hard to find out the comparison between those pandemics and this coronavirus. Following is a guide to compare coronavirus with such diseases and recent pandemics that have reformed the world community.

Coronavirus Versus Seasonal Influenza

Influenza, or seasonal flu, occurs globally every year–usually between December and February. It is impossible to determine the number of reports per year because it is not a reportable infection (so no need to be recorded to municipality), so often patients with minor symptoms do not go to a physician. Recent figures placed the Rate of Case Fatality at 0.1% [ 21 – 23 ].

There are approximately 3–5 million reports of serious influenza a year, and about 250,000–500,000 deaths globally. In most developed nations, the majority of deaths arise in persons over 65 years of age. Moreover, it is unsafe for pregnant mothers, children under 59 months of age and individuals with serious illnesses.

The annual vaccination eliminates infection and severe risks in most developing countries but is nevertheless a recognized yet uncomfortable aspect of the season.

In contrast to the seasonal influenza, coronavirus is not so common, has led to fewer cases till now, has a higher rate of case fatality and has no antidote.

Coronavirus Versus Bird Flu (H5N1 and H7N9)

Several cases of bird flu have existed over the years, with the most severe in 2013 and 2016. This is usually from two separate strains—H5N1 and H7N9 [ 24 – 26 ].

The H7N9 outbreak in 2016 accounted for one-third of all confirmed human cases but remained confined relative to both coronavirus and other pandemics/outbreak cases. After the first outbreak, about 1,233 laboratory-confirmed reports of bird flu have occurred. The disease has a Rate of Case Fatality of 20–40%.

Although the percentage is very high, the blowout from individual to individual is restricted, which, in effect, has minimized the number of related deaths. It is also impossible to monitor as birds do not necessarily expire from sickness.

In contrast to the bird flu, coronavirus becomes more common, travels more quickly through human to human interaction, has an inferior cardiothoracic ratio, resulting in further total fatalities and spread from the initial source.

Coronavirus Versus Ebola Epidemic

The Ebola epidemic of 2013 was primarily centred in 10 nations, including Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia have the greatest effects, but the extremely high Case Fatality Rate of 40% has created this as a significant problem for health professionals nationwide [ 27 – 29 ].

Around 2013 and 2016, there were about 28,646 suspicious incidents and about 11,323 fatalities, although these are expected to be overlooked. Those who survived from the original epidemic may still become sick months or even years later, because the infection may stay inactive for prolonged periods. Thankfully, a vaccination was launched in December 2016 and is perceived to be effective.

In contrast to the Ebola, coronavirus is more common globally, has caused in fewer fatalities, has a lesser case fatality rate, has no reported problems during treatment and after recovery, does not have an appropriate vaccination.

Coronavirus Versus Camel Flu (MERS)

Camel flu is a misnomer–though camels have MERS antibodies and may have been included in the transmission of the disease; it was originally transmitted to humans through bats [ 30 – 32 ]. Like Ebola, it infected only a limited number of nations, i.e. about 27, but about 858 fatalities from about 2,494 laboratory-confirmed reports suggested that it was a significant threat if no steps were taken in place to control it.

In contrast to the camel flu, coronavirus is more common globally, has occurred more fatalities, has a lesser case fatality rate, and spreads more easily among humans.

Coronavirus Versus Swine Flu (H1N1)

Swine flu is the same form of influenza that wiped 1.7% of the world population in 1918. This was deemed a pandemic again in June 2009 an approximately-21% of the global population infected by this [ 33 – 35 ].

Thankfully, the case fatality rate is substantially lower than in the last pandemic, with 0.1%–0.5% of events ending in death. About 18,500 of these fatalities have been laboratory-confirmed, but statistics range as high as 151,700–575,400 worldwide. 50–80% of severe occurrences have been reported in individuals with chronic illnesses like asthma, obesity, cardiovascular diseases and diabetes.

In contrast to the swine flu, coronavirus is not so common, has caused fewer fatalities, has more case fatality rate, has a longer growth time and less impact on young people.

Coronavirus Versus Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

SARS was discovered in 2003 as it spread from bats to humans resulted in about 774 fatalities. By May there were eventually about 8,100 reports across 17 countries, with a 15% case fatality rate. The number is estimated to be closer to 9.6% as confirmed cases are counted, with 0.9% cardiothoracic ratio for people aged 20–29, rising to 28% for people aged 70–79. Similar to coronavirus, SARS had bad results for males than females in all age categories [ 36 – 38 ].

Coronavirus is more common relative to SARS, which ended in more overall fatalities, lower case fatality rate, the even higher case fatality rate in older ages, and poorer results for males.

Coronavirus Versus Hong Kong Flu (H3N2)

The Hong Kong flu pandemic erupted on 13 July 1968, with 1–4 million deaths globally by 1969. It was one of the greatest flu pandemics of the twentieth century, but thankfully the case fatality rate was smaller than the epidemic of 1918, resulting in fewer fatalities overall. That may have been attributed to the fact that citizens had generated immunity owing to a previous epidemic in 1957 and to better medical treatment [ 39 ].

In contrast to the Hong Kong flu, coronavirus is not so common, has caused in fewer fatalities and has a higher case fatality rate.

Coronavirus Versus Spanish Flu (H1N1)

The 1918 Spanish flu pandemic was one of the greatest occurrences of recorded history. During the first year of the pandemic, lifespan in the US dropped by 12 years, with more civilians killed than HIV/AIDS in 24 h [ 40 – 42 ].

Regardless of the name, the epidemic did not necessarily arise in Spain; wartime censors in Germany, the United States, the United Kingdom and France blocked news of the disease, but Spain did not, creating the misleading perception that more cases and fatalities had occurred relative to its neighbours

This strain of H1N1 eventually affected more than 500 million men, or 27% of the world’s population at the moment, and had deaths of between 40 and 50 million. At the end of 1920, 1.7% of the world’s people had expired of this illness, including an exceptionally high death rate for young adults aged between 20 and 40 years.

In contrast to the Spanish flu, coronavirus is not so common, has caused in fewer fatalities, has a higher case fatality rate, is more harmful to older ages and is less risky for individuals aged 20–40 years.

Coronavirus Versus Common Cold (Typically Rhinovirus)

Common cold is the most common illness impacting people—Typically, a person suffers from 2–3 colds each year and the average kid will catch 6–8 during the similar time span. Although there are more than 200 cold-associated virus types, infections are uncommon and fatalities are very rare and typically arise mainly in extremely old, extremely young or immunosuppressed cases [ 43 , 44 ].

In contrast to the common cold, coronavirus is not so prevalent, causes more fatalities, has more case fatality rate, is less infectious and is less likely to impact small children.

Reviews of Online Portals and Social Media for Epidemic Information Dissemination

As COVID-19 started to propagate across the globe, the outbreak contributed to a significant change in the broad technology platforms. Where they once declined to engage in the affairs of their systems, except though the possible danger to public safety became obvious, the advent of a novel coronavirus placed them in a different interventionist way of thought. Big tech firms and social media are taking concrete steps to guide users to relevant, credible details on the virus [ 45 – 48 ]. And some of the measures they’re doing proactively. Below are a few of them.

Facebook started adding a box in the news feed that led users to the Centers for Disease Control website regarding COVID-19. It reflects a significant departure from the company’s normal strategy of placing items in the News Feed. The purpose of the update, after all, is personalization—Facebook tries to give the posts you’re going to care about, whether it is because you’re connected with a person or like a post. In the virus package, Facebook has placed a remarkable algorithmic thumb on the scale, potentially pushing millions of people to accurate, authenticated knowledge from a reputable source.

Similar initiatives have been adopted by Twitter. Searching for COVID-19 will carry you to a page highlighting the latest reports from public health groups and credible national news outlets. The search also allows for common misspellings. Twitter has stated that although Russian-style initiatives to cause discontent by large-scale intelligence operations have not yet been observed, a zero-tolerance approach to network exploitation and all other attempts to exploit their service at this crucial juncture will be expected. The problem has the attention of the organization. It also offers promotional support to public service agencies and other non-profit groups.

Google has made a step in making it better for those who choose to operate or research from home, offering specialized streaming services to all paying G Suite customers. Google also confirmed that free access to ‘advanced’ Hangouts Meet apps will be rolled out to both G Suite and G Suite for Education clients worldwide through 1st July. It ensures that companies can hold meetings of up to 250 people, broadcast live to up to about 100,000 users within a single network, and archive and export meetings to Google Drive. Usually, Google pays an additional $13 per person per month for these services in comparison to G Suite’s ‘enterprise’ membership, which adds up to a total of about $25 per client each month.

Microsoft took a similar move, introducing the software ‘Chat Device’ to help public health and protection in the coronavirus epidemic, which enables collaborative collaboration via video and text messaging. There’s an aspect of self-interest in this. Tech firms are offering out their goods free of charge during periods of emergency for the same purpose as newspapers are reducing their paywalls: it’s nice to draw more paying consumers.

Pinterest, which has introduced much of the anti-misinformation strategies that Facebook and Twitter are already embracing, is now restricting the search results for ‘coronavirus’, ‘COVID-19’ and similar words for ‘internationally recognized health organizations’.

Google-owned YouTube, traditionally the most conspiratorial website, has recently introduced a connection to the World Health Organization virus epidemic page to the top of the search results. In the early days of the epidemic, BuzzFeed found famous coronavirus conspiratorial videos on YouTube—especially in India, where one ‘explain’ with a false interpretation of the sources of the disease racketeered 13 million views before YouTube deleted it. Yet in the United States, conspiratorial posts regarding the illness have failed to gain only 1 million views.

That’s not to suggest that misinformation doesn’t propagate on digital platforms—just as it travels through the broader Internet, even though interaction with friends and relatives. When there’s a site that appears to be under-performing in the global epidemic, it’s Facebook-owned WhatsApp, where the Washington Post reported ‘a torrent of disinformation’ in places like Nigeria, Indonesia, Peru, Pakistan and Ireland. Given the encrypted existence of the app, it is difficult to measure the severity of the problem. Misinformation is also spread in WhatsApp communities, where participation is restricted to about 250 individuals. Knowledge of one category may be readily exchanged with another; however, there is a considerable amount of complexity of rotating several groups to peddle affected healing remedies or propagate false rumours.

Preventative Measures and Policies Enforced by the World Health Organization (WHO) and Different Countries

Coronavirus is already an ongoing epidemic, so it is necessary to take precautions to minimize both the risk of being sick and the transmission of the disease.

WHO Advice [ 49 ]

- Wash hands regularly with alcohol-based hand wash or soap and water.

- Preserve contact space (at least 1 m/3 feet between you and someone who sneezes or coughs).

- Don’t touch your nose, head and ears.

- Cover your nose and mouth as you sneeze or cough, preferably with your bent elbow or tissue.

- Try to find early medical attention if you have fatigue, cough and trouble breathing.

- Take preventive precautions if you are in or have recently go to places where coronavirus spreads.

The first person believed to have become sick because of the latest virus was near in Wuhan on 1 December 2019. A formal warning of the epidemic was released on 31 December. The World Health Organization was informed of the epidemic on the same day. Through 7 January, the Chinese Government addressed the avoidance and regulation of COVID-19. A curfew was declared on 23 January to prohibit flying in and out of Wuhan. Private usage of cars has been banned in the region. Chinese New Year (25 January) festivities have been cancelled in many locations [ 50 ].

On 26 January, the Communist Party and the Government adopted more steps to contain the COVID-19 epidemic, including safety warnings for travellers and improvements to national holidays. The leading party has agreed to prolong the Spring Festival holiday to control the outbreak. Universities and schools across the world have already been locked down. Many steps have been taken by the Hong Kong and Macau governments, in particular concerning schools and colleges. Remote job initiatives have been placed in effect in many regions of China. Several immigration limits have been enforced.

Certain counties and cities outside Hubei also implemented travel limits. Public transit has been changed and museums in China have been partially removed. Some experts challenged the quality of the number of cases announced by the Chinese Government, which constantly modified the way coronavirus cases were recorded.

Italy, a member state of the European Union and a popular tourist attraction, entered the list of coronavirus-affected nations on 30 January, when two positive cases in COVID-19 were identified among Chinese tourists. Italy has the largest number of coronavirus infections both in Europe and outside of China [ 51 ].

Infections, originally limited to northern Italy, gradually spread to all other areas. Many other nations in Asia, Europe and the Americas have tracked their local cases to Italy. Several Italian travellers were even infected with coronavirus-positive in foreign nations.

Late in Italy, the most impacted coronavirus cities and counties are Lombardia, accompanied by Veneto, Emilia-Romagna, Marche and Piedmonte. Milan, the second most populated city in Italy, is situated in Lombardy. Other regions in Italy with coronavirus comprised Campania, Toscana, Liguria, Lazio, Sicilia, Friuli Venezia Giulia, Umbria, Puglia, Trento, Abruzzo, Calabria, Molise, Valle d’Aosta, Sardegna, Bolzano and Basilicata.

Italy ranks 19th of the top 30 nations getting high-risk coronavirus airline passengers in China, as per WorldPop’s provisional study of the spread of COVID-19.

The Italian State has taken steps like the inspection and termination of large cultural activities during the early days of the coronavirus epidemic and has gradually declared the closing of educational establishments and airport hygiene/disinfection initiatives.

The Italian National Institute of Health suggested social distancing and agreed that the broader community of the country’s elderly is a problem. In the meantime, several other nations, including the US, have recommended that travel to Italy should be avoided temporarily, unless necessary.

The Italian government has declared the closing (quarantine) of the impacted areas in the northern region of the nation so as not to spread to the rest of the world. Italy has declared the immediate suspension of all to-and-fro air travel with China following coronavirus discovery by a Chinese tourist to Italy. Italian airlines, like Ryan Air, have begun introducing protective steps and have begun calling for the declaration forms to be submitted by passengers flying to Poland, Slovakia and Lithuania.

The Italian government first declined to permit fans to compete in sporting activities until early April to prevent the potential transmission of coronavirus. The step ensured players of health and stopped event cancellations because of coronavirus fears. Two days of the declaration, the government cancelled all athletic activities owing to the emergence of the outbreak asking for an emergency. Sports activities in Veneto, Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna, which recorded coronavirus-positive infections, were confirmed to be temporarily suspended. Schools and colleges in Italy have also been forced to shut down.

Iran announced the first recorded cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection on 19 February when, as per the Medical Education and Ministry of Health, two persons died later that day. The Ministry of Islamic Culture and Guidance has declared the cancellation of all concerts and other cultural activities for one week. The Medical Education and Ministry of Health has also declared the closing of universities, higher education colleges and schools in many cities and regions. The Department of Sports and Culture has taken action to suspend athletic activities, including football matches [ 52 ].

On 2 March 2020, the government revealed plans to train about 300,000 troops and volunteers to fight the outbreak of the epidemic, and also send robots and water cannons to clean the cities. The State also developed an initiative and a webpage to counter the epidemic. On 9 March 2020, nearly 70,000 inmates were immediately released from jail owing to the epidemic, presumably to prevent the further dissemination of the disease inside jails. The Revolutionary Guards declared a campaign on 13 March 2020 to clear highways, stores and public areas in Iran. President Hassan Rouhani stated on 26 February 2020 that there were no arrangements to quarantine areas impacted by the epidemic and only persons should be quarantined. The temples of Shia in Qom stayed open to pilgrims.

South Korea

On 20 January, South Korea announced its first occurrence. There was a large rise in cases on 20 February, possibly due to the meeting in Daegu of a progressive faith community recognized as the Shincheonji Church of Christ. Any citizens believed that the hospital was propagating the disease. As of 22 February, 1,261 of the 9,336 members of the church registered symptoms. A petition was distributed calling for the abolition of the church. More than 2,000 verified cases were registered on 28 February, increasing to 3,150 on 29 February [ 53 ].

Several educational establishments have been partially closing down, including hundreds of kindergartens in Daegu and many primary schools in Seoul. As of 18 February, several South Korean colleges had confirmed intentions to delay the launch of the spring semester. That included 155 institutions deciding to postpone the start of the semester by two weeks until 16 March, and 22 institutions deciding to delay the start of the semester by one week until 9 March. Also, on 23 February 2020, all primary schools, kindergartens, middle schools and secondary schools were declared to postpone the start of the semester from 2 March to 9 March.

South Korea’s economy is expected to expand by 1.9%, down from 2.1%. The State has given 136.7 billion won funding to local councils. The State has also coordinated the purchase of masks and other sanitary supplies. Entertainment Company SM Entertainment is confirmed to have contributed five hundred million won in attempts to fight the disease.

In the kpop industry, the widespread dissemination of coronavirus within South Korea has contributed to the cancellation or postponement of concerts and other programmes for kpop activities inside and outside South Korea. For instance, circumstances such as the cancellation of the remaining Asian dates and the European leg for the Seventeen’s Ode To You Tour on 9 February 2020 and the cancellation of all Seoul dates for the BTS Soul Tour Map. As of 15 March, a maximum of 136 countries and regions provided entry restrictions and/or expired visas for passengers from South Korea.

The overall reported cases of coronavirus rose significantly in France on 12 March. The areas with reported cases include Paris, Amiens, Bordeaux and Eastern Haute-Savoie. The first coronaviral death happened in France on 15 February, marking it the first death in Europe. The second death of a 60-year-old French national in Paris was announced on 26 February [ 54 ].

On February 28, fashion designer Agnès B. (not to be mistaken with Agnès Buzyn) cancelled fashion shows at the Paris Fashion Week, expected to continue until 3 March. On a subsequent day, the Paris half-marathon, planned for Sunday 1 March with 44,000 entrants, was postponed as one of a series of steps declared by Health Minister Olivier Véran.

On 13 March, the Ligue de Football Professional disbanded Ligue 1 and Ligue 2 (France’s tier two professional divisions) permanently due to safety threats.

Germany has a popular Regional Pandemic Strategy detailing the roles and activities of the health care system participants in the case of a significant outbreak. Epidemic surveillance is carried out by the federal government, like the Robert Koch Center, and by the German governments. The German States have their preparations for an outbreak. The regional strategy for the treatment of the current coronavirus epidemic was expanded by March 2020. Four primary goals are contained in this plan: (1) to minimize mortality and morbidity; (2) to guarantee the safety of sick persons; (3) to protect vital health services and (4) to offer concise and reliable reports to decision-makers, the media and the public [ 55 ].

The programme has three phases that may potentially overlap: (1) isolation (situation of individual cases and clusters), (2) safety (situation of further dissemination of pathogens and suspected causes of infection), (3) prevention (situation of widespread infection). So far, Germany has not set up border controls or common health condition tests at airports. Instead, while at the isolation stage-health officials are concentrating on recognizing contact individuals that are subject to specific quarantine and are tracked and checked. Specific quarantine is regulated by municipal health authorities. By doing so, the officials are seeking to hold the chains of infection small, contributing to decreased clusters. At the safety stage, the policy should shift to prevent susceptible individuals from being harmed by direct action. By the end of the day, the prevention process should aim to prevent cycles of acute treatment to retain emergency facilities.

United States

The very first case of coronavirus in the United States was identified in Washington on 21 January 2020 by an individual who flew to Wuhan and returned to the United States. The second case was recorded in Illinois by another individual who had travelled to Wuhan. Some of the regions with reported novel coronavirus infections in the US are California, Arizona, Connecticut, Illinois, Texas, Wisconsin and Washington [ 56 ].

As the epidemic increased, requests for domestic air travel decreased dramatically. By 4 March, U.S. carriers, like United Airlines and JetBlue Airways, started growing their domestic flight schedules, providing generous unpaid leave to workers and suspending recruits.

A significant number of universities and colleges cancelled classes and reopened dormitories in response to the epidemic, like Cornell University, Harvard University and the University of South Carolina.

On 3 March 2020, the Federal Reserve reduced its goal interest rate from 1.75% to 1.25%, the biggest emergency rate cut following the 2008 global financial crash, in combat the effect of the recession on the American economy. In February 2020, US businesses, including Apple Inc. and Microsoft, started to reduce sales projections due to supply chain delays in China caused by the COVID-19.

The pandemic, together with the subsequent financial market collapse, also contributed to greater criticism of the crisis in the United States. Researchers disagree about when a recession is likely to take effect, with others suggesting that it is not unavoidable, while some claim that the world might already be in recession. On 3 March, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell reported a 0.5% (50 basis point) interest rate cut from the coronavirus in the context of the evolving threats to economic growth.

When ‘social distance’ penetrated the national lexicon, disaster response officials promoted the cancellation of broad events to slow down the risk of infection. Technical conferences like E3 2020, Apple Inc.’s Worldwide Developers Conference (WWDC), Google I/O, Facebook F8, and Cloud Next and Microsoft’s MVP Conference have been either having replaced or cancelled in-person events with internet streaming events.

On February 29, the American Physical Society postponed its annual March gathering, planned for March 2–6 in Denver, Colorado, even though most of the more than 11,000 physicist attendees already had arrived and engaged in the pre-conference day activities. On March 6, the annual South to Southwest (SXSW) seminar and festival planned to take place from March 13–22 in Austin, Texas, was postponed after the city council announced a local disaster and forced conferences to be shut down for the first time in 34 years.

Four of North America’s major professional sports leagues—the National Hockey League (NHL), National Basketball Association (NBA), Major League Soccer (MLS) and Major League Baseball (MLB) —jointly declared on March 9 that they would all limit the media access to player accommodations (such as locker rooms) to control probable exposure.

Emergency Funding to Fight the COVID-19

COVID-19 pandemic has become a common international concern. Different countries are donating funds to fight against it [ 57 – 60 ]. Some of them are mentioned here.

China has allocated about 110.48 billion yuan ($15.93 billion) in coronavirus-related funding.

Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif said that Iran has requested the International Monetary Fund (IMF) of about $5 billion in emergency funding to help to tackle the coronavirus epidemic that has struck the Islamic Republic hard.

President Donald Trump approved the Emergency Supplementary Budget Bill to support the US response to a novel coronavirus epidemic. The budget plan would include about $8.3 billion in discretionary funding to local health authorities to promote vaccine research for production. Trump originally requested just about $2 billion to combat the epidemic, but Congress quadrupled the number in its version of the bill. Mr. Trump formally announced a national emergency that he claimed it will give states and territories access to up to about $50 billion in federal funding to tackle the spread of the coronavirus outbreak.

California politicians approved a plan to donate about $1 billion on the state’s emergency medical responses as it readies hospitals to fight an expected attack of patients because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The plans, drawn up rapidly in reaction to the dramatic rise in reported cases of the virus, would include the requisite funds to establish two new hospitals in California, with the assumption that the state may not have the resources to take care of the rise in patients. The bill calls for an immediate response of about $500 million from the State General Fund, with an additional about $500 million possible if requested.

India committed about $10 million to the COVID-19 Emergency Fund and said it was setting up a rapid response team of physicians for the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (Saarc) countries.

South Korea unveiled an economic stimulus package of about 11.7 trillion won ($9.8 billion) to soften the effects of the biggest coronavirus epidemic outside China as attempts to curb the disease exacerbate supply shortages and drain demand. Of the 11,7 trillion won expected, about 3.2 trillion won would cover up the budget shortfall, while an additional fiscal infusion of about 8.5 trillion won. An estimated 10.3 trillion won in government bonds will be sold this year to fund the extra expenditure. About 2.3 trillion won will be distributed to medical establishments and would support quarantine operations, with another 3.0 trillion won heading to small and medium-sized companies unable to pay salaries to their employees and child care supports.

The Swedish Parliament announced a set of initiatives costing more than 300 billion Swedish crowns ($30.94 billion) to help the economy in the view of the coronavirus pandemic. The plan contained steps like the central government paying the entire expense of the company’s sick leave during April and May, and also the high cost of compulsory redundancies owing to the crisis.

In consideration of the developing scenario, an updating of this strategy is planned to take place before the end of March and will recognize considerably greater funding demands for the country response, R&D and WHO itself.

Artificial Intelligence, Data Science and Technological Solutions Against COVID-19

These days, Artificial Intelligence (AI) takes a major role in health care. Throughout a worldwide pandemic such as the COVID-19, technology, artificial intelligence and data analytics have been crucial in helping communities cope successfully with the epidemic [ 61 – 65 ]. Through the aid of data mining and analytical modelling, medical practitioners are willing to learn more about several diseases.

Public Health Surveillance

The biggest risk of coronavirus is the level of spreading. That’s why policymakers are introducing steps like quarantines around the world because they can’t adequately monitor local outbreaks. One of the simplest measures to identify ill patients through the study of CCTV images that are still around us and to locate and separate individuals that have serious signs of the disease and who have touched and disinfected the related surfaces. Smartphone applications are often used to keep a watch on people’s activities and to assess whether or not they have come in touch with an infected human.

Remote Biosignal Measurement

Many of the signs such as temperature or heartbeat are very essential to overlook and rely entirely on the visual image that may be misleading. However, of course, we can’t prevent someone from checking their blood pressure, heart or temperature. Also, several advances in computer vision can predict pulse and blood pressure based on facial skin examination. Besides, there are several advances in computer vision that can predict pulse and blood pressure based on facial skin examination.

Access to public records has contributed to the development of dashboards that constantly track the virus. Several companies are designing large data dashboards. Face recognition and infrared temperature monitoring technologies have been mounted in all major cities. Chinese AI companies including Hanwang Technology and SenseTime have reported having established a special facial recognition system that can correctly identify people even though they are covered.

IoT and Wearables

Measurements like pulse are much more natural and easier to obtain from tracking gadgets like activity trackers and smartwatches that nearly everybody has already. Some work suggests that the study of cardiac activity and its variations from the standard will reveal early signs of influenza and, in this case, coronavirus.

Chatbots and Communication

Apart from public screening, people’s knowledge and self-assessment may also be used to track their health. If you can check your temperature and pulse every day and monitor your coughs time-to-time, you can even submit that to your record. If the symptoms are too serious, either an algorithm or a doctor remotely may prescribe a person to stay home, take several other preventive measures, or recommend a visit from the doctor.

Al Jazeera announced that China Mobile had sent text messages to state media departments, telling them about the citizens who had been affected. The communications contained all the specifics of the person’s travel history.

Tencent runs WeChat, and via it, citizens can use free online health consultation services. Chatbots have already become important connectivity platforms for transport and tourism service providers to keep passengers up-to-date with the current transport protocols and disturbances.

Social Media and Open Data

There are several people who post their health diary with total strangers via Facebook or Twitter. Such data becomes helpful for more general research about how far the epidemic has progressed. For consumer knowledge, we may even evaluate the social network group to attempt to predict what specific networks are at risk of being viral.

Canadian company BlueDot analyses far more than just social network data: for instance, global activities of more than four billion passengers on international flights per year; animal, human and insect population data; satellite environment data and relevant knowledge from health professionals and journalists, across 100,000 news posts per day covering 65 languages. This strategy was so successful that the corporation was able to alert clients about coronavirus until the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention notified the public.

Automated Diagnostics

COVID-19 has brought up another healthcare issue today: it will not scale when the number of patients increases exponentially (actually stressed doctors are always doing worse) and the rate of false-negative diagnosis remains very high. Machine learning therapies don’t get bored and scale simply by growing computing forces.

Baidu, the Chinese Internet company, has made the Lineatrfold algorithm accessible to the outbreak-fighting teams, according to the MIT Technology Review. Unlike HIV, Ebola and Influenza, COVID-19 has just one strand of RNA and it can mutate easily. The algorithm is also simpler than other algorithms that help to determine the nature of the virus. Baidu has also developed software to efficiently track large populations. It has also developed an Ai-powered infrared device that can detect a difference in the body temperature of a human. This is currently being used in Beijing’s Qinghe Railway Station to classify possibly contaminated travellers where up to 200 individuals may be checked in one minute without affecting traffic movement, reports the MIT Review.

Singapore-based Veredus Laboratories, a supplier of revolutionary molecular diagnostic tools, has currently announced the launch of the VereCoV detector package, a compact Lab-on-Chip device able to detect MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV and COVID-19, i.e. Wuhan Coronavirus, in a single study.

The VereCoV identification package is focused on VereChip technology, a Lab-on-Chip device that incorporates two important molecular biological systems, Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and a microarray, which will be able to classify and distinguish within 2 h MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV and COVID-19 with high precision and responsiveness.

This is not just the medical activities of healthcare facilities that are being charged, but also the corporate and financial departments when they cope with the increase in patients. Ant Financials’ blockchain technology helps speed-up the collection of reports and decreases the number of face-to-face encounters with patients and medical personnel.

Companies like the Israeli company Sonovia are aiming to provide healthcare systems and others with face masks manufactured from their anti-pathogenic, anti-bacterial cloth that depends on metal-oxide nanoparticles.

Drug Development Research

Aside from identifying and stopping the transmission of pathogens, the need to develop vaccinations on a scale is also needed. One of the crucial things to make that possible is to consider the origin and essence of the virus. Google’s DeepMind, with their expertise in protein folding research, has rendered a jump in identifying the protein structure of the virus and making it open-source.

BenevolentAI uses AI technologies to develop medicines that will combat the most dangerous diseases in the world and is also working to promote attempts to cure coronavirus, the first time the organization has based its product on infectious diseases. Within weeks of the epidemic, it used its analytical capability to recommend new medicines that might be beneficial.

Robots are not vulnerable to the infection, and they are used to conduct other activities, like cooking meals in hospitals, doubling up as waiters in hotels, spraying disinfectants and washing, selling rice and hand sanitizers, robots are on the front lines all over to deter coronavirus spread. Robots also conduct diagnostics and thermal imaging in several hospitals. Shenzhen-based firm Multicopter uses robotics to move surgical samples. UVD robots from Blue Ocean Robotics use ultraviolet light to destroy viruses and bacteria separately. In China, Pudu Technology has introduced its robots, which are usually used in the cooking industry, to more than 40 hospitals throughout the region. According to the Reuters article, a tiny robot named Little Peanut is distributing food to passengers who have been on a flight from Singapore to Hangzhou, China, and are presently being quarantined in a hotel.

Colour Coding

Using its advanced and vast public service monitoring network, the Chinese government has collaborated with software companies Alibaba and Tencent to establish a colour-coded health ranking scheme that monitors millions of citizens every day. The mobile device was first introduced in Hangzhou with the cooperation of Alibaba. This applies three colours to people—red, green or yellow—based on their transportation and medical records. Tencent also developed related applications in the manufacturing centre of Shenzhen.

The decision of whether an individual will be quarantined or permitted in public spaces is dependent on the colour code. Citizens will sign into the system using pay wallet systems such as Alibaba’s Alipay and Ant’s wallet. Just those citizens who have been issued a green colour code will be permitted to use the QR code in public spaces at metro stations, workplaces, and other public areas. Checkpoints are in most public areas where the body temperature and the code of individual are tested. This programme is being used by more than 200 Chinese communities and will eventually be expanded nationwide.

In some of the seriously infected regions where people remain at risk of contracting the infection, drones are used to rescue. One of the easiest and quickest ways to bring emergency supplies where they need to go while on an epidemic of disease is by drone transportation. Drones carry all surgical instruments and patient samples. This saves time, improves the pace of distribution and reduces the chance of contamination of medical samples. Drones often operate QR code placards that can be checked to record health records. There are also agricultural drones distributing disinfectants in the farmland. Drones, operated by facial recognition, are often used to warn people not to leave their homes and to chide them for not using face masks. Terra Drone uses its unmanned drones to move patient samples and vaccination content at reduced risk between the Xinchang County Disease Control Center and the People’s Hospital. Drones are often used to monitor public areas, document non-compliance with quarantine laws and thermal imaging.

Autonomous Vehicles

At a period of considerable uncertainty to medical professionals and the danger to people-to-people communication, automated vehicles are proving to be of tremendous benefit in the transport of vital products, such as medications and foodstuffs. Apollo, the Baidu Autonomous Vehicle Project, has joined hands with the Neolix self-driving company to distribute food and supplies to a big hospital in Beijing. Baidu Apollo has also provided its micro-car packages and automated cloud driving systems accessible free of charge to virus-fighting organizations.

Idriverplus, a Chinese self-driving organization that runs electrical street cleaning vehicles, is also part of the project. The company’s signature trucks are used to clean hospitals.

This chapter provides an introduction to the coronavirus outbreak (COVID-19). A brief history of this virus along with the symptoms are reported in this chapter. Then the comparison between COVID-19 and other plagues like seasonal influenza, bird flu (H5N1 and H7N9), Ebola epidemic, camel flu (MERS), swine flu (H1N1), severe acute respiratory syndrome, Hong Kong flu (H3N2), Spanish flu and the common cold are included in this chapter. Reviews of online portal and social media like Facebook, Twitter, Google, Microsoft, Pinterest, YouTube and WhatsApp concerning COVID-19 are reported in this chapter. Also, the preventive measures and policies enforced by WHO and different countries such as China, Italy, Iran, South Korea, France, Germany and the United States for COVID-19 are included in this chapter. Emergency funding provided by different countries to fight the COVID-19 is mentioned in this chapter. Lastly, artificial intelligence, data science and technological solutions like public health surveillance, remote biosignal measurement, IoT and wearables, chatbots and communication, social media and open data, automated diagnostics, drug development research, robotics, colour coding, drones and autonomous vehicles are included in this chapter.

How to Write About Coronavirus in a College Essay

Students can share how they navigated life during the coronavirus pandemic in a full-length essay or an optional supplement.

Writing About COVID-19 in College Essays

Getty Images

Experts say students should be honest and not limit themselves to merely their experiences with the pandemic.

The global impact of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, means colleges and prospective students alike are in for an admissions cycle like no other. Both face unprecedented challenges and questions as they grapple with their respective futures amid the ongoing fallout of the pandemic.

Colleges must examine applicants without the aid of standardized test scores for many – a factor that prompted many schools to go test-optional for now . Even grades, a significant component of a college application, may be hard to interpret with some high schools adopting pass-fail classes last spring due to the pandemic. Major college admissions factors are suddenly skewed.

"I can't help but think other (admissions) factors are going to matter more," says Ethan Sawyer, founder of the College Essay Guy, a website that offers free and paid essay-writing resources.

College essays and letters of recommendation , Sawyer says, are likely to carry more weight than ever in this admissions cycle. And many essays will likely focus on how the pandemic shaped students' lives throughout an often tumultuous 2020.

But before writing a college essay focused on the coronavirus, students should explore whether it's the best topic for them.

Writing About COVID-19 for a College Application

Much of daily life has been colored by the coronavirus. Virtual learning is the norm at many colleges and high schools, many extracurriculars have vanished and social lives have stalled for students complying with measures to stop the spread of COVID-19.

"For some young people, the pandemic took away what they envisioned as their senior year," says Robert Alexander, dean of admissions, financial aid and enrollment management at the University of Rochester in New York. "Maybe that's a spot on a varsity athletic team or the lead role in the fall play. And it's OK for them to mourn what should have been and what they feel like they lost, but more important is how are they making the most of the opportunities they do have?"

That question, Alexander says, is what colleges want answered if students choose to address COVID-19 in their college essay.

But the question of whether a student should write about the coronavirus is tricky. The answer depends largely on the student.

"In general, I don't think students should write about COVID-19 in their main personal statement for their application," Robin Miller, master college admissions counselor at IvyWise, a college counseling company, wrote in an email.

"Certainly, there may be exceptions to this based on a student's individual experience, but since the personal essay is the main place in the application where the student can really allow their voice to be heard and share insight into who they are as an individual, there are likely many other topics they can choose to write about that are more distinctive and unique than COVID-19," Miller says.

Opinions among admissions experts vary on whether to write about the likely popular topic of the pandemic.

"If your essay communicates something positive, unique, and compelling about you in an interesting and eloquent way, go for it," Carolyn Pippen, principal college admissions counselor at IvyWise, wrote in an email. She adds that students shouldn't be dissuaded from writing about a topic merely because it's common, noting that "topics are bound to repeat, no matter how hard we try to avoid it."

Above all, she urges honesty.

"If your experience within the context of the pandemic has been truly unique, then write about that experience, and the standing out will take care of itself," Pippen says. "If your experience has been generally the same as most other students in your context, then trying to find a unique angle can easily cross the line into exploiting a tragedy, or at least appearing as though you have."

But focusing entirely on the pandemic can limit a student to a single story and narrow who they are in an application, Sawyer says. "There are so many wonderful possibilities for what you can say about yourself outside of your experience within the pandemic."

He notes that passions, strengths, career interests and personal identity are among the multitude of essay topic options available to applicants and encourages them to probe their values to help determine the topic that matters most to them – and write about it.

That doesn't mean the pandemic experience has to be ignored if applicants feel the need to write about it.

Writing About Coronavirus in Main and Supplemental Essays

Students can choose to write a full-length college essay on the coronavirus or summarize their experience in a shorter form.

To help students explain how the pandemic affected them, The Common App has added an optional section to address this topic. Applicants have 250 words to describe their pandemic experience and the personal and academic impact of COVID-19.

"That's not a trick question, and there's no right or wrong answer," Alexander says. Colleges want to know, he adds, how students navigated the pandemic, how they prioritized their time, what responsibilities they took on and what they learned along the way.

If students can distill all of the above information into 250 words, there's likely no need to write about it in a full-length college essay, experts say. And applicants whose lives were not heavily altered by the pandemic may even choose to skip the optional COVID-19 question.

"This space is best used to discuss hardship and/or significant challenges that the student and/or the student's family experienced as a result of COVID-19 and how they have responded to those difficulties," Miller notes. Using the section to acknowledge a lack of impact, she adds, "could be perceived as trite and lacking insight, despite the good intentions of the applicant."

To guard against this lack of awareness, Sawyer encourages students to tap someone they trust to review their writing , whether it's the 250-word Common App response or the full-length essay.

Experts tend to agree that the short-form approach to this as an essay topic works better, but there are exceptions. And if a student does have a coronavirus story that he or she feels must be told, Alexander encourages the writer to be authentic in the essay.

"My advice for an essay about COVID-19 is the same as my advice about an essay for any topic – and that is, don't write what you think we want to read or hear," Alexander says. "Write what really changed you and that story that now is yours and yours alone to tell."

Sawyer urges students to ask themselves, "What's the sentence that only I can write?" He also encourages students to remember that the pandemic is only a chapter of their lives and not the whole book.

Miller, who cautions against writing a full-length essay on the coronavirus, says that if students choose to do so they should have a conversation with their high school counselor about whether that's the right move. And if students choose to proceed with COVID-19 as a topic, she says they need to be clear, detailed and insightful about what they learned and how they adapted along the way.

"Approaching the essay in this manner will provide important balance while demonstrating personal growth and vulnerability," Miller says.

Pippen encourages students to remember that they are in an unprecedented time for college admissions.

"It is important to keep in mind with all of these (admission) factors that no colleges have ever had to consider them this way in the selection process, if at all," Pippen says. "They have had very little time to calibrate their evaluations of different application components within their offices, let alone across institutions. This means that colleges will all be handling the admissions process a little bit differently, and their approaches may even evolve over the course of the admissions cycle."

Searching for a college? Get our complete rankings of Best Colleges.

10 Ways to Discover College Essay Ideas

Tags: students , colleges , college admissions , college applications , college search , Coronavirus

2024 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

College Admissions: Get a Step Ahead!

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S. News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

Ask an Alum: Making the Most Out of College

You May Also Like

10 destination west coast college towns.

Cole Claybourn May 16, 2024

Scholarships for Lesser-Known Sports

Sarah Wood May 15, 2024

Should Students Submit Test Scores?

Sarah Wood May 13, 2024

Poll: Antisemitism a Problem on Campus

Lauren Camera May 13, 2024

Federal vs. Private Parent Student Loans

Erika Giovanetti May 9, 2024

14 Colleges With Great Food Options

Sarah Wood May 8, 2024

Colleges With Religious Affiliations

Anayat Durrani May 8, 2024

Protests Threaten Campus Graduations

Aneeta Mathur-Ashton May 6, 2024

Protesting on Campus: What to Know

Sarah Wood May 6, 2024

Lawmakers Ramp Up Response to Unrest

Aneeta Mathur-Ashton May 3, 2024

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

COVID-19 Pandemic

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 11, 2024 | Original: April 25, 2023

The outbreak of the infectious respiratory disease known as COVID-19 triggered one of the deadliest pandemics in modern history. COVID-19 claimed nearly 7 million lives worldwide. In the United States, deaths from COVID-19 exceeded 1.1 million, nearly twice the American death toll from the 1918 flu pandemic . The COVID-19 pandemic also took a heavy toll economically, politically and psychologically, revealing deep divisions in the way that Americans viewed the role of government in a public health crisis, particularly vaccine mandates. While the United States downgraded its “national emergency” status over the pandemic on May 11, 2023, the full effects of the COVID-19 pandemic will reverberate for decades.

A New Virus Breaks Out in Wuhan, China

In December 2019, the China office of the World Health Organization (WHO) received news of an isolated outbreak of a pneumonia-like virus in the city of Wuhan. The virus caused high fevers and shortness of breath, and the cases seemed connected to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan, which was closed by an emergency order on January 1, 2020.

After testing samples of the unknown virus, the WHO identified it as a novel type of coronavirus similar to the deadly SARS virus that swept through Asia from 2002-2004. The WHO named this new strain SARS-CoV-2 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2). The first Chinese victim of SARS-CoV-2 died on January 11, 2020.

Where, exactly, the novel virus originated has been hotly debated. There are two leading theories. One is that the virus jumped from animals to humans, possibly carried by infected animals sold at the Wuhan market in late 2019. A second theory claims the virus escaped from the Wuhan Institute of Virology, a research lab that was studying coronaviruses. U.S. intelligence agencies maintain that both origin stories are “plausible.”

The First COVID-19 Cases in America

The WHO hoped that the virus outbreak would be contained to Wuhan, but by mid-January 2020, infections were reported in Thailand, Japan and Korea, all from people who had traveled to China.

On January 18, 2020, a 35-year-old man checked into an urgent care center near Seattle, Washington. He had just returned from Wuhan and was experiencing a fever, nausea and vomiting. On January 21, he was identified as the first American infected with SARS-CoV-2.

In reality, dozens of Americans had contracted SARS-CoV-2 weeks earlier, but doctors didn’t think to test for a new type of virus. One of those unknowingly infected patients died on February 6, 2020, but her death wasn’t confirmed as the first American casualty until April 21.

On February 11, 2020, the WHO released a new name for the disease causing the deadly outbreak: Coronavirus Disease 2019 or COVID-19. By mid-March 2020, all 50 U.S. states had reported at least one positive case of COVID-19, and nearly all of the new infections were caused by “community spread,” not by people who contracted the disease while traveling abroad.

At the same time, COVID-19 had spread to 114 countries worldwide, killing more than 4,000 people and infecting hundreds of thousands more. On March 11, the WHO made it official and declared COVID-19 a pandemic.

The World Shuts Down

Pandemics are expected in a globally interconnected world, so emergency plans were in place. In the United States, health officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) set in motion a national response plan developed for flu pandemics.

State by state and city by city, government officials took emergency measures to encourage “ social distancing ,” one of the many new terms that became part of the COVID-19 vocabulary. Travel was restricted. Schools and churches were closed. With the exception of “essential workers,” all offices and businesses were shuttered. By early April 2020, more than 316 million Americans were under a shelter-in-place or stay-at-home order.

With more than 1,000 deaths and nearly 100,000 cases, it was clear by April 2020 that COVID-19 was highly contagious and virulent. What wasn’t clear, even to public health officials, was how individuals could best protect themselves from COVID-19. In the early weeks of the outbreak, the CDC discouraged people from buying face masks, because officials feared a shortage of masks for doctors and hospital workers.

By April 2020, the CDC revised its recommendations, encouraging people to wear masks in public, to socially distance and to wash hands frequently. President Donald Trump undercut the CDC recommendations by emphasizing that masking was voluntary and vowing not to wear a mask himself. This was just the beginning of the political divisions that hobbled the COVID-19 response in America.

Global Financial Markets Collapse

In the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, with billions of people worldwide out of work, stuck at home, and fretting over shortages of essential items like toilet paper , global financial markets went into a tailspin.

In the United States, share prices on the New York Stock Exchange plummeted so quickly that the exchange had to shut down trading three separate times. The Dow Jones Industrial Average eventually lost 37 percent of its value, and the S&P 500 was down 34 percent.

Business closures and stay-at-home orders gutted the U.S. economy. The unemployment rate skyrocketed, particularly in the service sector (restaurant and other retail workers). By May 2020, the U.S. unemployment rate reached 14.7 percent, the highest jobless rate since the Great Depression .

All across America, households felt the pinch of lost jobs and lower wages. Food insecurity reached a peak by December 2020 with 30 million American adults—a full 14 percent—reporting that their families didn’t get enough to eat in the past week.

The economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, like its health effects, weren’t experienced equally. Black, Hispanic and Native Americans suffered from unemployment and food insecurity at significantly higher rates than white Americans.

Congress tried to avoid a complete economic collapse by authorizing a series of COVID-19 relief packages in 2020 and 2021, which included direct stimulus checks for all American families.

The Race for a Vaccine

A new vaccine typically takes 10 to 15 years to develop and test, but the world couldn’t wait that long for a COVID-19 vaccine. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under the Trump administration launched “ Operation Warp Speed ,” a public-private partnership which provided billions of dollars in upfront funding to pharmaceutical companies to rapidly develop vaccines and conduct clinical trials.

The first clinical trial for a COVID-19 vaccine was announced on March 16, 2020, only days after the WHO officially classified COVID-19 as a pandemic. The vaccines developed by Moderna and Pfizer were the first ever to employ messenger RNA, a breakthrough technology. After large-scale clinical trials, both vaccines were found to be greater than 95 percent effective against infection with COVID-19.

A nurse from New York officially became the first American to receive a COVID-19 vaccine on December 14, 2020. Ten days later, more than 1 million vaccines had been administered, starting with healthcare workers and elderly residents of nursing homes. As the months rolled on, vaccine availability was expanded to all American adults, and then to teenagers and all school-age children.

By the end of the pandemic in early 2023, more than 670 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines had been administered in the United States at a rate of 203 doses per 100 people. Approximately 80 percent of the U.S. population received at least one COVID-19 shot, but vaccination rates were markedly lower among Black, Hispanic and Native Americans.

COVID-19 Deaths Heaviest Among Elderly and People of Color

In America, the COVID-19 pandemic impacted everyone’s lives, but those who died from the disease were far more likely to be older and people of color.

Of the more than 1.1 million COVID deaths in the United States, 75 percent were individuals who were 65 or older. A full 93 percent of American COVID-19 victims were 50 or older. Throughout the emergence of COVID-19 variants and the vaccine rollouts, older Americans remained the most at-risk for being hospitalized and ultimately dying from the disease.

Black, Hispanic and Native Americans were also at a statistically higher risk of developing life-threatening COVID-19 systems and succumbing to the disease. For example, Black and Hispanic Americans were twice as likely to be hospitalized from COVID-19 than white Americans. The COVID-19 pandemic shined light on the health disparities between racial and ethnic groups driven by systemic racism and lower access to healthcare.

Mental health also worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic. The anxiety of contracting the disease, and the stresses of being unemployed or confined at home, led to unprecedented numbers of Americans reporting feelings of depression and suicidal ideation.

A Time of Social & Political Upheaval

In the United States, the three long years of the COVID-19 pandemic paralleled a time of heightened political contention and social upheaval.

When George Floyd was killed by Minneapolis police on May 25, 2020, it sparked nationwide protests against police brutality and energized the Black Lives Matter movement. Because so many Americans were out of work or home from school due to COVID-19 shutdowns, unprecedented numbers of people from all walks of life took to the streets to demand reforms.

Instead of banding together to slow the spread of the disease, Americans became sharply divided along political lines in their opinions of masking requirements, vaccines and social distancing.

By March 2024, in signs that the pandemic was waning, the CDC issued new guidelines for people who were recovering from COVID-19. The agency said those infected with the virus no longer needed to remain isolated for five days after symptoms. And on March 10, 2024, the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center stopped collecting data for its highly referenced COVID-19 dashboard.

Still, an estimated 17 percent of U.S. adults reported having experienced symptoms of long COVID, according to the Household Pulse Survey. The medical community is still working to understand the causes behind long COVID, which can afflict a patient for weeks, months or even years.

HISTORY Vault

Stream thousands of hours of acclaimed series, probing documentaries and captivating specials commercial-free in HISTORY Vault

“CDC Museum COVID Timeline.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . “Coronavirus: Timeline.” U.S. Department of Defense . “COVID-19 and Related Vaccine Development and Research.” Mayo Clinic . “COVID-19 Cases and Deaths by Race/Ethnicity: Current Data and Changes Over Time.” Kaiser Family Foundation . “Number of COVID-19 Deaths in the U.S. by Age.” Statista . “The Pandemic Deepened Fault Lines in American Society.” Scientific American . “Tracking the COVID-19 Economy’s Effects on Food, Housing, and Employment Hardships.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities . “U.S. Confirmed Country’s First Case of COVID-19 3 Years Ago.” CNN .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 76, Issue 2

- COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on social relationships and health

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1512-4471 Emily Long 1 ,

- Susan Patterson 1 ,

- Karen Maxwell 1 ,

- Carolyn Blake 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7342-4566 Raquel Bosó Pérez 1 ,

- Ruth Lewis 1 ,

- Mark McCann 1 ,

- Julie Riddell 1 ,

- Kathryn Skivington 1 ,

- Rachel Wilson-Lowe 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4409-6601 Kirstin R Mitchell 2

- 1 MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit , University of Glasgow , Glasgow , UK

- 2 MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, Institute of Health & Wellbeing , University of Glasgow , Glasgow , UK

- Correspondence to Dr Emily Long, MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G3 7HR, UK; emily.long{at}glasgow.ac.uk

This essay examines key aspects of social relationships that were disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. It focuses explicitly on relational mechanisms of health and brings together theory and emerging evidence on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic to make recommendations for future public health policy and recovery. We first provide an overview of the pandemic in the UK context, outlining the nature of the public health response. We then introduce four distinct domains of social relationships: social networks, social support, social interaction and intimacy, highlighting the mechanisms through which the pandemic and associated public health response drastically altered social interactions in each domain. Throughout the essay, the lens of health inequalities, and perspective of relationships as interconnecting elements in a broader system, is used to explore the varying impact of these disruptions. The essay concludes by providing recommendations for longer term recovery ensuring that the social relational cost of COVID-19 is adequately considered in efforts to rebuild.

- inequalities

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable as no data sets generated and/or analysed for this study. Data sharing not applicable as no data sets generated or analysed for this essay.

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2021-216690

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Introduction

Infectious disease pandemics, including SARS and COVID-19, demand intrapersonal behaviour change and present highly complex challenges for public health. 1 A pandemic of an airborne infection, spread easily through social contact, assails human relationships by drastically altering the ways through which humans interact. In this essay, we draw on theories of social relationships to examine specific ways in which relational mechanisms key to health and well-being were disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Relational mechanisms refer to the processes between people that lead to change in health outcomes.

At the time of writing, the future surrounding COVID-19 was uncertain. Vaccine programmes were being rolled out in countries that could afford them, but new and more contagious variants of the virus were also being discovered. The recovery journey looked long, with continued disruption to social relationships. The social cost of COVID-19 was only just beginning to emerge, but the mental health impact was already considerable, 2 3 and the inequality of the health burden stark. 4 Knowledge of the epidemiology of COVID-19 accrued rapidly, but evidence of the most effective policy responses remained uncertain.

The initial response to COVID-19 in the UK was reactive and aimed at reducing mortality, with little time to consider the social implications, including for interpersonal and community relationships. The terminology of ‘social distancing’ quickly became entrenched both in public and policy discourse. This equation of physical distance with social distance was regrettable, since only physical proximity causes viral transmission, whereas many forms of social proximity (eg, conversations while walking outdoors) are minimal risk, and are crucial to maintaining relationships supportive of health and well-being.

The aim of this essay is to explore four key relational mechanisms that were impacted by the pandemic and associated restrictions: social networks, social support, social interaction and intimacy. We use relational theories and emerging research on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic response to make three key recommendations: one regarding public health responses; and two regarding social recovery. Our understanding of these mechanisms stems from a ‘systems’ perspective which casts social relationships as interdependent elements within a connected whole. 5

Social networks

Social networks characterise the individuals and social connections that compose a system (such as a workplace, community or society). Social relationships range from spouses and partners, to coworkers, friends and acquaintances. They vary across many dimensions, including, for example, frequency of contact and emotional closeness. Social networks can be understood both in terms of the individuals and relationships that compose the network, as well as the overall network structure (eg, how many of your friends know each other).

Social networks show a tendency towards homophily, or a phenomenon of associating with individuals who are similar to self. 6 This is particularly true for ‘core’ network ties (eg, close friends), while more distant, sometimes called ‘weak’ ties tend to show more diversity. During the height of COVID-19 restrictions, face-to-face interactions were often reduced to core network members, such as partners, family members or, potentially, live-in roommates; some ‘weak’ ties were lost, and interactions became more limited to those closest. Given that peripheral, weaker social ties provide a diversity of resources, opinions and support, 7 COVID-19 likely resulted in networks that were smaller and more homogenous.

Such changes were not inevitable nor necessarily enduring, since social networks are also adaptive and responsive to change, in that a disruption to usual ways of interacting can be replaced by new ways of engaging (eg, Zoom). Yet, important inequalities exist, wherein networks and individual relationships within networks are not equally able to adapt to such changes. For example, individuals with a large number of newly established relationships (eg, university students) may have struggled to transfer these relationships online, resulting in lost contacts and a heightened risk of social isolation. This is consistent with research suggesting that young adults were the most likely to report a worsening of relationships during COVID-19, whereas older adults were the least likely to report a change. 8

Lastly, social connections give rise to emergent properties of social systems, 9 where a community-level phenomenon develops that cannot be attributed to any one member or portion of the network. For example, local area-based networks emerged due to geographic restrictions (eg, stay-at-home orders), resulting in increases in neighbourly support and local volunteering. 10 In fact, research suggests that relationships with neighbours displayed the largest net gain in ratings of relationship quality compared with a range of relationship types (eg, partner, colleague, friend). 8 Much of this was built from spontaneous individual interactions within local communities, which together contributed to the ‘community spirit’ that many experienced. 11 COVID-19 restrictions thus impacted the personal social networks and the structure of the larger networks within the society.

Social support