- Become Involved |

- Give to the Library |

- Staff Directory |

- UNF Library

- Thomas G. Carpenter Library

Conducting a Literature Review

Benefits of conducting a literature review.

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Summary of the Process

- Additional Resources

- Literature Review Tutorial by American University Library

- The Literature Review: A Few Tips On Conducting It by University of Toronto

- Write a Literature Review by UC Santa Cruz University Library

While there might be many reasons for conducting a literature review, following are four key outcomes of doing the review.

Assessment of the current state of research on a topic . This is probably the most obvious value of the literature review. Once a researcher has determined an area to work with for a research project, a search of relevant information sources will help determine what is already known about the topic and how extensively the topic has already been researched.

Identification of the experts on a particular topic . One of the additional benefits derived from doing the literature review is that it will quickly reveal which researchers have written the most on a particular topic and are, therefore, probably the experts on the topic. Someone who has written twenty articles on a topic or on related topics is more than likely more knowledgeable than someone who has written a single article. This same writer will likely turn up as a reference in most of the other articles written on the same topic. From the number of articles written by the author and the number of times the writer has been cited by other authors, a researcher will be able to assume that the particular author is an expert in the area and, thus, a key resource for consultation in the current research to be undertaken.

Identification of key questions about a topic that need further research . In many cases a researcher may discover new angles that need further exploration by reviewing what has already been written on a topic. For example, research may suggest that listening to music while studying might lead to better retention of ideas, but the research might not have assessed whether a particular style of music is more beneficial than another. A researcher who is interested in pursuing this topic would then do well to follow up existing studies with a new study, based on previous research, that tries to identify which styles of music are most beneficial to retention.

Determination of methodologies used in past studies of the same or similar topics. It is often useful to review the types of studies that previous researchers have launched as a means of determining what approaches might be of most benefit in further developing a topic. By the same token, a review of previously conducted studies might lend itself to researchers determining a new angle for approaching research.

Upon completion of the literature review, a researcher should have a solid foundation of knowledge in the area and a good feel for the direction any new research should take. Should any additional questions arise during the course of the research, the researcher will know which experts to consult in order to quickly clear up those questions.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Aug 29, 2022 8:54 AM

- URL: https://libguides.unf.edu/litreview

News alert: UC Berkeley has announced its next university librarian

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

Conducting a literature review: why do a literature review, why do a literature review.

- How To Find "The Literature"

- Found it -- Now What?

Besides the obvious reason for students -- because it is assigned! -- a literature review helps you explore the research that has come before you, to see how your research question has (or has not) already been addressed.

You identify:

- core research in the field

- experts in the subject area

- methodology you may want to use (or avoid)

- gaps in knowledge -- or where your research would fit in

It Also Helps You:

- Publish and share your findings

- Justify requests for grants and other funding

- Identify best practices to inform practice

- Set wider context for a program evaluation

- Compile information to support community organizing

Great brief overview, from NCSU

Want To Know More?

- Next: How To Find "The Literature" >>

- Last Updated: Apr 25, 2024 1:10 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/litreview

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Introduction

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Introduction

- Getting Started

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

What are Literature Reviews?

So, what is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries." Taylor, D. The literature review: A few tips on conducting it . University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre.

Goals of Literature Reviews

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review? A literature could be written to accomplish different aims:

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Review of General Psychology , 1 (3), 311-320.

What kinds of sources require a Literature Review?

- A research paper assigned in a course

- A thesis or dissertation

- A grant proposal

- An article intended for publication in a journal

All these instances require you to collect what has been written about your research topic so that you can demonstrate how your own research sheds new light on the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Narrative review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Example : Predictors and Outcomes of U.S. Quality Maternity Leave: A Review and Conceptual Framework: 10.1177/08948453211037398

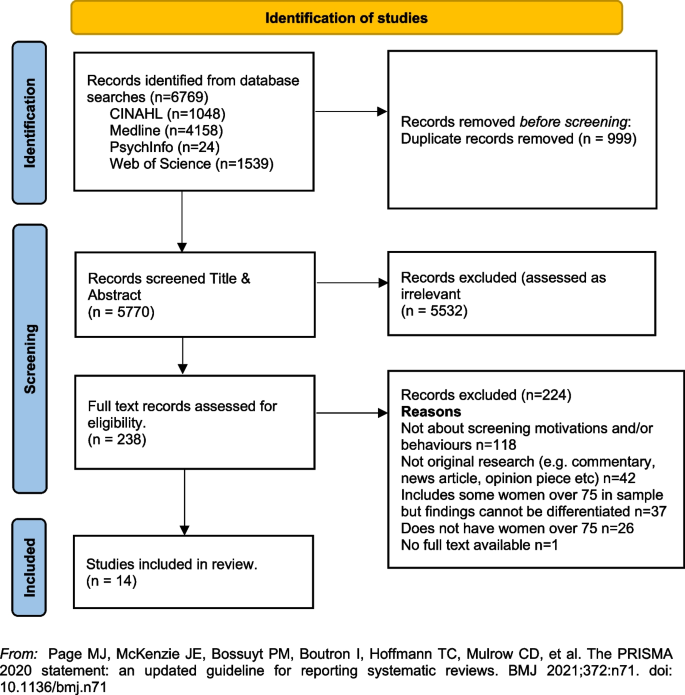

Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L. K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . Plural Publishing.

- Example : The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review: 10.1057/s41599-022-01270-w

Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M. C., & Ilardi, S. S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Blackwell Publishing.

- Example : Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A Meta-Analysis: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311-318.

- Example : Women’s perspectives on career successes and barriers: A qualitative meta-synthesis: 10.1177/05390184221113735

Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- UConn Health subject guide on systematic reviews Explanation of the different review types used in health sciences literature as well as tools to help you find the right review type

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: How to Pick a Topic >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

Libraries | Research Guides

Literature reviews, what is a literature review, learning more about how to do a literature review.

- Planning the Review

- The Research Question

- Choosing Where to Search

- Organizing the Review

- Writing the Review

A literature review is a review and synthesis of existing research on a topic or research question. A literature review is meant to analyze the scholarly literature, make connections across writings and identify strengths, weaknesses, trends, and missing conversations. A literature review should address different aspects of a topic as it relates to your research question. A literature review goes beyond a description or summary of the literature you have read.

- Sage Research Methods Core Collection This link opens in a new window SAGE Research Methods supports research at all levels by providing material to guide users through every step of the research process. SAGE Research Methods is the ultimate methods library with more than 1000 books, reference works, journal articles, and instructional videos by world-leading academics from across the social sciences, including the largest collection of qualitative methods books available online from any scholarly publisher. – Publisher

- Next: Planning the Review >>

- Last Updated: Jan 17, 2024 10:05 AM

- URL: https://libguides.northwestern.edu/literaturereviews

Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

- Collections

- Research Help

YSN Doctoral Programs: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Biomedical Databases

- Global (Public Health) Databases

- Soc. Sci., History, and Law Databases

- Grey Literature

- Trials Registers

- Data and Statistics

- Public Policy

- Google Tips

- Recommended Books

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis -- not just a summary-- of scholarly writings and other relevant evidence related directly to your research question. That is, it represents a synthesis of the evidence that provides background information on your topic and shows a association between the evidence and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

Why is it important?

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Identifies critical gaps and points of disagreement.

- Discusses further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies.

APA7 Style resources

APA Style Blog - for those harder to find answers

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by your central research question. The literature represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow. Is it manageable?

- Begin writing down terms that are related to your question. These will be useful for searches later.

- If you have the opportunity, discuss your topic with your professor and your class mates.

2. Decide on the scope of your review

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment. How many sources does the assignment require?

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

Make a list of the databases you will search.

Where to find databases:

- use the tabs on this guide

- Find other databases in the Nursing Information Resources web page

- More on the Medical Library web page

- ... and more on the Yale University Library web page

4. Conduct your searches to find the evidence. Keep track of your searches.

- Use the key words in your question, as well as synonyms for those words, as terms in your search. Use the database tutorials for help.

- Save the searches in the databases. This saves time when you want to redo, or modify, the searches. It is also helpful to use as a guide is the searches are not finding any useful results.

- Review the abstracts of research studies carefully. This will save you time.

- Use the bibliographies and references of research studies you find to locate others.

- Check with your professor, or a subject expert in the field, if you are missing any key works in the field.

- Ask your librarian for help at any time.

- Use a citation manager, such as EndNote as the repository for your citations. See the EndNote tutorials for help.

Review the literature

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question of the study you are reviewing? What were the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze its literature review, the samples and variables used, the results, and the conclusions.

- Does the research seem to be complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicting studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Has this study been cited? If so, how has it been analyzed?

Tips:

- Review the abstracts carefully.

- Keep careful notes so that you may track your thought processes during the research process.

- Create a matrix of the studies for easy analysis, and synthesis, across all of the studies.

- << Previous: Recommended Books

- Last Updated: Jan 4, 2024 10:52 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/YSNDoctoral

- Library Homepage

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide: Literature Reviews?

- Literature Reviews?

- Strategies to Finding Sources

- Keeping up with Research!

- Evaluating Sources & Literature Reviews

- Organizing for Writing

- Writing Literature Review

- Other Academic Writings

What is a Literature Review?

So, what is a literature review .

"A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available or a set of summaries." - Quote from Taylor, D. (n.d)."The Literature Review: A Few Tips on Conducting it".

- Citation: "The Literature Review: A Few Tips on Conducting it"

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Each field has a particular way to do reviews for academic research literature. In the social sciences and humanities the most common are:

- Narrative Reviews: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific research topic and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weaknesses, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section that summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Book review essays/ Historiographical review essays : A type of literature review typical in History and related fields, e.g., Latin American studies. For example, the Latin American Research Review explains that the purpose of this type of review is to “(1) to familiarize readers with the subject, approach, arguments, and conclusions found in a group of books whose common focus is a historical period; a country or region within Latin America; or a practice, development, or issue of interest to specialists and others; (2) to locate these books within current scholarship, critical methodologies, and approaches; and (3) to probe the relation of these new books to previous work on the subject, especially canonical texts. Unlike individual book reviews, the cluster reviews found in LARR seek to address the state of the field or discipline and not solely the works at issue.” - LARR

What are the Goals of Creating a Literature Review?

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

- Baumeister, R.F. & Leary, M.R. (1997). "Writing narrative literature reviews," Review of General Psychology , 1(3), 311-320.

When do you need to write a Literature Review?

- When writing a prospectus or a thesis/dissertation

- When writing a research paper

- When writing a grant proposal

In all these cases you need to dedicate a chapter in these works to showcase what has been written about your research topic and to point out how your own research will shed new light into a body of scholarship.

Where I can find examples of Literature Reviews?

Note: In the humanities, even if they don't use the term "literature review", they may have a dedicated chapter that reviewed the "critical bibliography" or they incorporated that review in the introduction or first chapter of the dissertation, book, or article.

- UCSB electronic theses and dissertations In partnership with the Graduate Division, the UC Santa Barbara Library is making available theses and dissertations produced by UCSB students. Currently included in ADRL are theses and dissertations that were originally filed electronically, starting in 2011. In future phases of ADRL, all theses and dissertations created by UCSB students may be digitized and made available.

Where to Find Standalone Literature Reviews

Literature reviews are also written as standalone articles as a way to survey a particular research topic in-depth. This type of literature review looks at a topic from a historical perspective to see how the understanding of the topic has changed over time.

- Find e-Journals for Standalone Literature Reviews The best way to get familiar with and to learn how to write literature reviews is by reading them. You can use our Journal Search option to find journals that specialize in publishing literature reviews from major disciplines like anthropology, sociology, etc. Usually these titles are called, "Annual Review of [discipline name] OR [Discipline name] Review. This option works best if you know the title of the publication you are looking for. Below are some examples of these journals! more... less... Journal Search can be found by hovering over the link for Research on the library website.

Social Sciences

- Annual Review of Anthropology

- Annual Review of Political Science

- Annual Review of Sociology

- Ethnic Studies Review

Hard science and health sciences:

- Annual Review of Biomedical Data Science

- Annual Review of Materials Science

- Systematic Review From journal site: "The journal Systematic Reviews encompasses all aspects of the design, conduct, and reporting of systematic reviews" in the health sciences.

- << Previous: Overview

- Next: Strategies to Finding Sources >>

- Last Updated: Mar 5, 2024 11:44 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucsb.edu/litreview

Get Started

Take the first step and invest in your future.

Online Programs

Offering flexibility & convenience in 51 online degrees & programs.

Prairie Stars

Featuring 15 intercollegiate NCAA Div II athletic teams.

Find your Fit

UIS has over 85 student and 10 greek life organizations, and many volunteer opportunities.

Arts & Culture

Celebrating the arts to create rich cultural experiences on campus.

Give Like a Star

Your generosity helps fuel fundraising for scholarships, programs and new initiatives.

Bragging Rights

UIS was listed No. 1 in Illinois and No. 3 in the Midwest in 2023 rankings.

- Quick links Applicants & Students Important Apps & Links Alumni Faculty and Staff Community Admissions How to Apply Cost & Aid Tuition Calculator Registrar Orientation Visit Campus Academics Register for Class Programs of Study Online Degrees & Programs Graduate Education International Student Services Study Away Student Support Bookstore UIS Life Dining Diversity & Inclusion Get Involved Health & Wellness COVID-19 United in Safety Residence Life Student Life Programs UIS Connection Important Apps UIS Mobile App Advise U Canvas myUIS i-card Balance Pay My Bill - UIS Bursar Self-Service Email Resources Bookstore Box Information Technology Services Library Orbit Policies Webtools Get Connected Area Information Calendar Campus Recreation Departments & Programs (A-Z) Parking UIS Newsroom Connect & Get Involved Update your Info Alumni Events Alumni Networks & Groups Volunteer Opportunities Alumni Board News & Publications Featured Alumni Alumni News UIS Alumni Magazine Resources Order your Transcripts Give Back Alumni Programs Career Development Services & Support Accessibility Services Campus Services Campus Police Facilities & Services Registrar Faculty & Staff Resources Website Project Request Web Services Training & Tools Academic Impressions Career Connect CSA Reporting Cybersecurity Training Faculty Research FERPA Training Website Login Campus Resources Newsroom Campus Calendar Campus Maps i-Card Human Resources Public Relations Webtools Arts & Events UIS Performing Arts Center Visual Arts Gallery Event Calendar Sangamon Experience Center for Lincoln Studies ECCE Speaker Series Community Engagement Center for State Policy and Leadership Illinois Innocence Project Innovate Springfield Central IL Nonprofit Resource Center NPR Illinois Community Resources Child Protection Training Academy Office of Electronic Media University Archives/IRAD Institute for Illinois Public Finance

Request Info

Literature Review

- Request Info Request info for.... Undergraduate/Graduate Online Study Away Continuing & Professional Education International Student Services General Inquiries

The purpose of a literature review is to collect relevant, timely research on your chosen topic, and synthesize it into a cohesive summary of existing knowledge in the field. This then prepares you for making your own argument on that topic, or for conducting your own original research.

Depending on your field of study, literature reviews can take different forms. Some disciplines require that you synthesize your sources topically, organizing your paragraphs according to how your different sources discuss similar topics. Other disciplines require that you discuss each source in individual paragraphs, covering various aspects in that single article, chapter, or book.

Within your review of a given source, you can cover many different aspects, including (if a research study) the purpose, scope, methods, results, any discussion points, limitations, and implications for future research. Make sure you know which model your professor expects you to follow when writing your own literature reviews.

Tip : Literature reviews may or may not be a graded component of your class or major assignment, but even if it is not, it is a good idea to draft one so that you know the current conversations taking place on your chosen topic. It can better prepare you to write your own, unique argument.

Benefits of Literature Reviews

- Literature reviews allow you to gain familiarity with the current knowledge in your chosen field, as well as the boundaries and limitations of that field.

- Literature reviews also help you to gain an understanding of the theory(ies) driving the field, allowing you to place your research question into context.

- Literature reviews provide an opportunity for you to see and even evaluate successful and unsuccessful assessment and research methods in your field.

- Literature reviews prevent you from duplicating the same information as others writing in your field, allowing you to find your own, unique approach to your topic.

- Literature reviews give you familiarity with the knowledge in your field, giving you the chance to analyze the significance of your additional research.

Choosing Your Sources

When selecting your sources to compile your literature review, make sure you follow these guidelines to ensure you are working with the strongest, most appropriate sources possible.

Topically Relevant

Find sources within the scope of your topic

Appropriately Aged

Find sources that are not too old for your assignment

Find sources whose authors have authority on your topic

Appropriately “Published”

Find sources that meet your instructor’s guidelines (academic, professional, print, etc.)

Tip: Treat your professors and librarians as experts you can turn to for advice on how to locate sources. They are a valuable asset to you, so take advantage of them!

Organizing Your Literature Review

Synthesizing topically.

Some assignments require discussing your sources together, in paragraphs organized according to shared topics between them.

For example, in a literature review covering current conversations on Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home , authors may discuss various topics including:

- her graphic style

- her allusions to various literary texts

- her story’s implications regarding LGBT experiences in 20 th century America.

In this case, you would cluster your sources on these three topics. One paragraph would cover how the sources you collected dealt with Bechdel’s graphic style. Another, her allusions. A third, her implications.

Each of these paragraphs would discuss how the sources you found treated these topics in connection to one another. Basically, you compare and contrast how your sources discuss similar issues and points.

To determine these shared topics, examine aspects including:

- Definition of terms

- Common ground

- Issues that divide

- Rhetorical context

Summarizing Individually

Depending on the assignment, your professor may prefer that you discuss each source in your literature review individually (in their own, separate paragraphs or sections). Your professor may give you specific guidelines as far as what to cover in these paragraphs/sections.

If, for instance, your sources are all primary research studies, here are some aspects to consider covering:

- Participants

- Limitations

- Implications

- Significance

Each section of your literature review, in this case, will identify all of these elements for each individual article.

You may or may not need to separate your information into multiple paragraphs for each source. If you do, using proper headings in the appropriate citation style (APA, MLA, etc.) will help keep you organized.

If you are writing a literature review as part of a larger assignment, you generally do not need an introduction and/or conclusion, because it is embedded within the context of your larger paper.

If, however, your literature review is a standalone assignment, it is a good idea to include some sort of introduction and conclusion to provide your reader with context regarding your topic, purpose, and any relevant implications or further questions. Make sure you know what your professor is expecting for your literature review’s content.

Typically, a literature review concludes with a full bibliography of your included sources. Make sure you use the style guide required by your professor for this assignment.

Research Methods

- Getting Started

- Literature Review Research

- Research Design

- Research Design By Discipline

- SAGE Research Methods

- Teaching with SAGE Research Methods

Literature Review

- What is a Literature Review?

- What is NOT a Literature Review?

- Purposes of a Literature Review

- Types of Literature Reviews

- Literature Reviews vs. Systematic Reviews

- Systematic vs. Meta-Analysis

Literature Review is a comprehensive survey of the works published in a particular field of study or line of research, usually over a specific period of time, in the form of an in-depth, critical bibliographic essay or annotated list in which attention is drawn to the most significant works.

Also, we can define a literature review as the collected body of scholarly works related to a topic:

- Summarizes and analyzes previous research relevant to a topic

- Includes scholarly books and articles published in academic journals

- Can be an specific scholarly paper or a section in a research paper

The objective of a Literature Review is to find previous published scholarly works relevant to an specific topic

- Help gather ideas or information

- Keep up to date in current trends and findings

- Help develop new questions

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Helps focus your own research questions or problems

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Suggests unexplored ideas or populations

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias.

- Identifies critical gaps, points of disagreement, or potentially flawed methodology or theoretical approaches.

- Indicates potential directions for future research.

All content in this section is from Literature Review Research from Old Dominion University

Keep in mind the following, a literature review is NOT:

Not an essay

Not an annotated bibliography in which you summarize each article that you have reviewed. A literature review goes beyond basic summarizing to focus on the critical analysis of the reviewed works and their relationship to your research question.

Not a research paper where you select resources to support one side of an issue versus another. A lit review should explain and consider all sides of an argument in order to avoid bias, and areas of agreement and disagreement should be highlighted.

A literature review serves several purposes. For example, it

- provides thorough knowledge of previous studies; introduces seminal works.

- helps focus one’s own research topic.

- identifies a conceptual framework for one’s own research questions or problems; indicates potential directions for future research.

- suggests previously unused or underused methodologies, designs, quantitative and qualitative strategies.

- identifies gaps in previous studies; identifies flawed methodologies and/or theoretical approaches; avoids replication of mistakes.

- helps the researcher avoid repetition of earlier research.

- suggests unexplored populations.

- determines whether past studies agree or disagree; identifies controversy in the literature.

- tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias.

As Kennedy (2007) notes*, it is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the original studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally that become part of the lore of field. In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews.

Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are several approaches to how they can be done, depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study. Listed below are definitions of types of literature reviews:

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply imbedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews.

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical reviews are focused on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [content], but how they said it [method of analysis]. This approach provides a framework of understanding at different levels (i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches and data collection and analysis techniques), enables researchers to draw on a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection and data analysis, and helps highlight many ethical issues which we should be aware of and consider as we go through our study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyse data from the studies that are included in the review. Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?"

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to concretely examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review help establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

* Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147.

All content in this section is from The Literature Review created by Dr. Robert Larabee USC

Robinson, P. and Lowe, J. (2015), Literature reviews vs systematic reviews. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 39: 103-103. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12393

What's in the name? The difference between a Systematic Review and a Literature Review, and why it matters . By Lynn Kysh from University of Southern California

Systematic review or meta-analysis?

A systematic review answers a defined research question by collecting and summarizing all empirical evidence that fits pre-specified eligibility criteria.

A meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of these studies.

Systematic reviews, just like other research articles, can be of varying quality. They are a significant piece of work (the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination at York estimates that a team will take 9-24 months), and to be useful to other researchers and practitioners they should have:

- clearly stated objectives with pre-defined eligibility criteria for studies

- explicit, reproducible methodology

- a systematic search that attempts to identify all studies

- assessment of the validity of the findings of the included studies (e.g. risk of bias)

- systematic presentation, and synthesis, of the characteristics and findings of the included studies

Not all systematic reviews contain meta-analysis.

Meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of independent studies. By combining information from all relevant studies, meta-analysis can provide more precise estimates of the effects of health care than those derived from the individual studies included within a review. More information on meta-analyses can be found in Cochrane Handbook, Chapter 9 .

A meta-analysis goes beyond critique and integration and conducts secondary statistical analysis on the outcomes of similar studies. It is a systematic review that uses quantitative methods to synthesize and summarize the results.

An advantage of a meta-analysis is the ability to be completely objective in evaluating research findings. Not all topics, however, have sufficient research evidence to allow a meta-analysis to be conducted. In that case, an integrative review is an appropriate strategy.

Some of the content in this section is from Systematic reviews and meta-analyses: step by step guide created by Kate McAllister.

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: Research Design >>

- Last Updated: Aug 21, 2023 4:07 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.udel.edu/researchmethods

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

- What is a literature review?

- Steps in the Literature Review Process

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

What is a Literature Review?

A literature or narrative review is a comprehensive review and analysis of the published literature on a specific topic or research question. The literature that is reviewed contains: books, articles, academic articles, conference proceedings, association papers, and dissertations. It contains the most pertinent studies and points to important past and current research and practices. It provides background and context, and shows how your research will contribute to the field.

A literature review should:

- Provide a comprehensive and updated review of the literature;

- Explain why this review has taken place;

- Articulate a position or hypothesis;

- Acknowledge and account for conflicting and corroborating points of view

From S age Research Methods

Purpose of a Literature Review

A literature review can be written as an introduction to a study to:

- Demonstrate how a study fills a gap in research

- Compare a study with other research that's been done

Or it can be a separate work (a research article on its own) which:

- Organizes or describes a topic

- Describes variables within a particular issue/problem

Limitations of a Literature Review

Some of the limitations of a literature review are:

- It's a snapshot in time. Unlike other reviews, this one has beginning, a middle and an end. There may be future developments that could make your work less relevant.

- It may be too focused. Some niche studies may miss the bigger picture.

- It can be difficult to be comprehensive. There is no way to make sure all the literature on a topic was considered.

- It is easy to be biased if you stick to top tier journals. There may be other places where people are publishing exemplary research. Look to open access publications and conferences to reflect a more inclusive collection. Also, make sure to include opposing views (and not just supporting evidence).

Source: Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information & Libraries Journal, vol. 26, no. 2, June 2009, pp. 91–108. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

Meryl Brodsky : Communication and Information Studies

Hannah Chapman Tripp : Biology, Neuroscience

Carolyn Cunningham : Human Development & Family Sciences, Psychology, Sociology

Larayne Dallas : Engineering

Janelle Hedstrom : Special Education, Curriculum & Instruction, Ed Leadership & Policy

Susan Macicak : Linguistics

Imelda Vetter : Dell Medical School

For help in other subject areas, please see the guide to library specialists by subject .

Periodically, UT Libraries runs a workshop covering the basics and library support for literature reviews. While we try to offer these once per academic year, we find providing the recording to be helpful to community members who have missed the session. Following is the most recent recording of the workshop, Conducting a Literature Review. To view the recording, a UT login is required.

- October 26, 2022 recording

- Last Updated: Oct 26, 2022 2:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

The objective of a literature review

Questions to Consider

B. In some fields or contexts, a literature review is referred to as the introduction or the background; why is this true, and does it matter?

The elements of a literature review • The first step in scholarly research is determining the “state of the art” on a topic. This is accomplished by gathering academic research and making sense of it. • The academic literature can be found in scholarly books and journals; the goal is to discover recurring themes, find the latest data, and identify any missing pieces. • The resulting literature review organizes the research in such a way that tells a story about the topic or issue.

The literature review tells a story in which one well-paraphrased summary from a relevant source contributes to and connects with the next in a logical manner, developing and fulfilling the message of the author. It includes analysis of the arguments from the literature, as well as revealing consistent and inconsistent findings. How do varying author insights differ from or conform to previous arguments?

Language in Action

A. How are the terms “critique” and “review” used in everyday life? How are they used in an academic context?

In terms of content, a literature review is intended to:

• Set up a theoretical framework for further research • Show a clear understanding of the key concepts/studies/models related to the topic • Demonstrate knowledge about the history of the research area and any related controversies • Clarify significant definitions and terminology • Develop a space in the existing work for new research

The literature consists of the published works that document a scholarly conversation or progression on a problem or topic in a field of study. Among these are documents that explain the background and show the loose ends in the established research on which a proposed project is based. Although a literature review focuses on primary, peer -reviewed resources, it may begin with background subject information generally found in secondary and tertiary sources such as books and encyclopedias. Following that essential overview, the seminal literature of the field is explored. As a result, while a literature review may consist of research articles tightly focused on a topic with secondary and tertiary sources used more sparingly, all three types of information (primary, secondary, tertiary) are critical.

The literature review, often referred to as the Background or Introduction to a research paper that presents methods, materials, results and discussion, exists in every field and serves many functions in research writing.

Adapted from Frederiksen, L., & Phelps, S. F. (2017). Literature Reviews for Education and Nursing Graduate Students. Open Textbook Library

Review and Reinforce

Two common approaches are simply outlined here. Which seems more common? Which more productive? Why? A. Forward exploration 1. Sources on a topic or problem are gathered. 2. Salient themes are discovered. 3. Research gaps are considered for future research. B. Backward exploration 1. Sources pertaining to an existing research project are gathered. 2. The justification of the research project’s methods or materials are explained and supported based on previously documented research.

Media Attributions

- 2589960988_3eeca91ba4_o © Untitled blue is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

Sourcing, summarizing, and synthesizing: Skills for effective research writing Copyright © 2023 by Wendy L. McBride is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

A literature review is a critical analysis and synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. It provides an overview of the current state of knowledge, identifies gaps, and highlights key findings in the literature. 1 The purpose of a literature review is to situate your own research within the context of existing scholarship, demonstrating your understanding of the topic and showing how your work contributes to the ongoing conversation in the field. Learning how to write a literature review is a critical tool for successful research. Your ability to summarize and synthesize prior research pertaining to a certain topic demonstrates your grasp on the topic of study, and assists in the learning process.

Table of Contents

- What is the purpose of literature review?

- a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

- b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

- c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

- d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

- How to write a good literature review

- Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Select Databases for Searches:

- Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Review the Literature:

- Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Frequently asked questions

What is a literature review?

A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the existing literature, establishes the context for their own research, and contributes to scholarly conversations on the topic. One of the purposes of a literature review is also to help researchers avoid duplicating previous work and ensure that their research is informed by and builds upon the existing body of knowledge.

What is the purpose of literature review?

A literature review serves several important purposes within academic and research contexts. Here are some key objectives and functions of a literature review: 2

- Contextualizing the Research Problem: The literature review provides a background and context for the research problem under investigation. It helps to situate the study within the existing body of knowledge.

- Identifying Gaps in Knowledge: By identifying gaps, contradictions, or areas requiring further research, the researcher can shape the research question and justify the significance of the study. This is crucial for ensuring that the new research contributes something novel to the field.

- Understanding Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks: Literature reviews help researchers gain an understanding of the theoretical and conceptual frameworks used in previous studies. This aids in the development of a theoretical framework for the current research.

- Providing Methodological Insights: Another purpose of literature reviews is that it allows researchers to learn about the methodologies employed in previous studies. This can help in choosing appropriate research methods for the current study and avoiding pitfalls that others may have encountered.

- Establishing Credibility: A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with existing scholarship, establishing their credibility and expertise in the field. It also helps in building a solid foundation for the new research.

- Informing Hypotheses or Research Questions: The literature review guides the formulation of hypotheses or research questions by highlighting relevant findings and areas of uncertainty in existing literature.

Literature review example

Let’s delve deeper with a literature review example: Let’s say your literature review is about the impact of climate change on biodiversity. You might format your literature review into sections such as the effects of climate change on habitat loss and species extinction, phenological changes, and marine biodiversity. Each section would then summarize and analyze relevant studies in those areas, highlighting key findings and identifying gaps in the research. The review would conclude by emphasizing the need for further research on specific aspects of the relationship between climate change and biodiversity. The following literature review template provides a glimpse into the recommended literature review structure and content, demonstrating how research findings are organized around specific themes within a broader topic.

Literature Review on Climate Change Impacts on Biodiversity:

Climate change is a global phenomenon with far-reaching consequences, including significant impacts on biodiversity. This literature review synthesizes key findings from various studies:

a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

Climate change-induced alterations in temperature and precipitation patterns contribute to habitat loss, affecting numerous species (Thomas et al., 2004). The review discusses how these changes increase the risk of extinction, particularly for species with specific habitat requirements.

b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

Observations of range shifts and changes in the timing of biological events (phenology) are documented in response to changing climatic conditions (Parmesan & Yohe, 2003). These shifts affect ecosystems and may lead to mismatches between species and their resources.

c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

The review explores the impact of climate change on marine biodiversity, emphasizing ocean acidification’s threat to coral reefs (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007). Changes in pH levels negatively affect coral calcification, disrupting the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

Recognizing the urgency of the situation, the literature review discusses various adaptive strategies adopted by species and conservation efforts aimed at mitigating the impacts of climate change on biodiversity (Hannah et al., 2007). It emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary approaches for effective conservation planning.

How to write a good literature review

Writing a literature review involves summarizing and synthesizing existing research on a particular topic. A good literature review format should include the following elements.

Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for your literature review, providing context and introducing the main focus of your review.

- Opening Statement: Begin with a general statement about the broader topic and its significance in the field.

- Scope and Purpose: Clearly define the scope of your literature review. Explain the specific research question or objective you aim to address.

- Organizational Framework: Briefly outline the structure of your literature review, indicating how you will categorize and discuss the existing research.

- Significance of the Study: Highlight why your literature review is important and how it contributes to the understanding of the chosen topic.

- Thesis Statement: Conclude the introduction with a concise thesis statement that outlines the main argument or perspective you will develop in the body of the literature review.

Body: The body of the literature review is where you provide a comprehensive analysis of existing literature, grouping studies based on themes, methodologies, or other relevant criteria.

- Organize by Theme or Concept: Group studies that share common themes, concepts, or methodologies. Discuss each theme or concept in detail, summarizing key findings and identifying gaps or areas of disagreement.

- Critical Analysis: Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each study. Discuss the methodologies used, the quality of evidence, and the overall contribution of each work to the understanding of the topic.

- Synthesis of Findings: Synthesize the information from different studies to highlight trends, patterns, or areas of consensus in the literature.

- Identification of Gaps: Discuss any gaps or limitations in the existing research and explain how your review contributes to filling these gaps.

- Transition between Sections: Provide smooth transitions between different themes or concepts to maintain the flow of your literature review.

Conclusion: The conclusion of your literature review should summarize the main findings, highlight the contributions of the review, and suggest avenues for future research.

- Summary of Key Findings: Recap the main findings from the literature and restate how they contribute to your research question or objective.

- Contributions to the Field: Discuss the overall contribution of your literature review to the existing knowledge in the field.

- Implications and Applications: Explore the practical implications of the findings and suggest how they might impact future research or practice.

- Recommendations for Future Research: Identify areas that require further investigation and propose potential directions for future research in the field.

- Final Thoughts: Conclude with a final reflection on the importance of your literature review and its relevance to the broader academic community.

Conducting a literature review

Conducting a literature review is an essential step in research that involves reviewing and analyzing existing literature on a specific topic. It’s important to know how to do a literature review effectively, so here are the steps to follow: 1

Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Select a topic that is relevant to your field of study.

- Clearly define your research question or objective. Determine what specific aspect of the topic do you want to explore?

Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Determine the timeframe for your literature review. Are you focusing on recent developments, or do you want a historical overview?

- Consider the geographical scope. Is your review global, or are you focusing on a specific region?

- Define the inclusion and exclusion criteria. What types of sources will you include? Are there specific types of studies or publications you will exclude?

Select Databases for Searches:

- Identify relevant databases for your field. Examples include PubMed, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

- Consider searching in library catalogs, institutional repositories, and specialized databases related to your topic.

Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Develop a systematic search strategy using keywords, Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT), and other search techniques.

- Record and document your search strategy for transparency and replicability.

- Keep track of the articles, including publication details, abstracts, and links. Use citation management tools like EndNote, Zotero, or Mendeley to organize your references.

Review the Literature:

- Evaluate the relevance and quality of each source. Consider the methodology, sample size, and results of studies.

- Organize the literature by themes or key concepts. Identify patterns, trends, and gaps in the existing research.

- Summarize key findings and arguments from each source. Compare and contrast different perspectives.

- Identify areas where there is a consensus in the literature and where there are conflicting opinions.

- Provide critical analysis and synthesis of the literature. What are the strengths and weaknesses of existing research?

Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Literature review outline should be based on themes, chronological order, or methodological approaches.

- Write a clear and coherent narrative that synthesizes the information gathered.

- Use proper citations for each source and ensure consistency in your citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.).

- Conclude your literature review by summarizing key findings, identifying gaps, and suggesting areas for future research.

The literature review sample and detailed advice on writing and conducting a review will help you produce a well-structured report. But remember that a literature review is an ongoing process, and it may be necessary to revisit and update it as your research progresses.

Frequently asked questions

A literature review is a critical and comprehensive analysis of existing literature (published and unpublished works) on a specific topic or research question and provides a synthesis of the current state of knowledge in a particular field. A well-conducted literature review is crucial for researchers to build upon existing knowledge, avoid duplication of efforts, and contribute to the advancement of their field. It also helps researchers situate their work within a broader context and facilitates the development of a sound theoretical and conceptual framework for their studies.

Literature review is a crucial component of research writing, providing a solid background for a research paper’s investigation. The aim is to keep professionals up to date by providing an understanding of ongoing developments within a specific field, including research methods, and experimental techniques used in that field, and present that knowledge in the form of a written report. Also, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the scholar in his or her field.

Before writing a literature review, it’s essential to undertake several preparatory steps to ensure that your review is well-researched, organized, and focused. This includes choosing a topic of general interest to you and doing exploratory research on that topic, writing an annotated bibliography, and noting major points, especially those that relate to the position you have taken on the topic.

Literature reviews and academic research papers are essential components of scholarly work but serve different purposes within the academic realm. 3 A literature review aims to provide a foundation for understanding the current state of research on a particular topic, identify gaps or controversies, and lay the groundwork for future research. Therefore, it draws heavily from existing academic sources, including books, journal articles, and other scholarly publications. In contrast, an academic research paper aims to present new knowledge, contribute to the academic discourse, and advance the understanding of a specific research question. Therefore, it involves a mix of existing literature (in the introduction and literature review sections) and original data or findings obtained through research methods.

Literature reviews are essential components of academic and research papers, and various strategies can be employed to conduct them effectively. If you want to know how to write a literature review for a research paper, here are four common approaches that are often used by researchers. Chronological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the chronological order of publication. It helps to trace the development of a topic over time, showing how ideas, theories, and research have evolved. Thematic Review: Thematic reviews focus on identifying and analyzing themes or topics that cut across different studies. Instead of organizing the literature chronologically, it is grouped by key themes or concepts, allowing for a comprehensive exploration of various aspects of the topic. Methodological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the research methods employed in different studies. It helps to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of various methodologies and allows the reader to evaluate the reliability and validity of the research findings. Theoretical Review: A theoretical review examines the literature based on the theoretical frameworks used in different studies. This approach helps to identify the key theories that have been applied to the topic and assess their contributions to the understanding of the subject. It’s important to note that these strategies are not mutually exclusive, and a literature review may combine elements of more than one approach. The choice of strategy depends on the research question, the nature of the literature available, and the goals of the review. Additionally, other strategies, such as integrative reviews or systematic reviews, may be employed depending on the specific requirements of the research.

The literature review format can vary depending on the specific publication guidelines. However, there are some common elements and structures that are often followed. Here is a general guideline for the format of a literature review: Introduction: Provide an overview of the topic. Define the scope and purpose of the literature review. State the research question or objective. Body: Organize the literature by themes, concepts, or chronology. Critically analyze and evaluate each source. Discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the studies. Highlight any methodological limitations or biases. Identify patterns, connections, or contradictions in the existing research. Conclusion: Summarize the key points discussed in the literature review. Highlight the research gap. Address the research question or objective stated in the introduction. Highlight the contributions of the review and suggest directions for future research.

Both annotated bibliographies and literature reviews involve the examination of scholarly sources. While annotated bibliographies focus on individual sources with brief annotations, literature reviews provide a more in-depth, integrated, and comprehensive analysis of existing literature on a specific topic. The key differences are as follows:

References

- Denney, A. S., & Tewksbury, R. (2013). How to write a literature review. Journal of criminal justice education , 24 (2), 218-234.

- Pan, M. L. (2016). Preparing literature reviews: Qualitative and quantitative approaches . Taylor & Francis.

- Cantero, C. (2019). How to write a literature review. San José State University Writing Center .

Paperpal is an AI writing assistant that help academics write better, faster with real-time suggestions for in-depth language and grammar correction. Trained on millions of research manuscripts enhanced by professional academic editors, Paperpal delivers human precision at machine speed.

Try it for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime , which unlocks unlimited access to premium features like academic translation, paraphrasing, contextual synonyms, consistency checks and more. It’s like always having a professional academic editor by your side! Go beyond limitations and experience the future of academic writing. Get Paperpal Prime now at just US$19 a month!

Related Reads:

- Empirical Research: A Comprehensive Guide for Academics

- How to Write a Scientific Paper in 10 Steps

- Life Sciences Papers: 9 Tips for Authors Writing in Biological Sciences

- What is an Argumentative Essay? How to Write It (With Examples)

6 Tips for Post-Doc Researchers to Take Their Career to the Next Level

Self-plagiarism in research: what it is and how to avoid it, you may also like, measuring academic success: definition & strategies for excellence, what is academic writing: tips for students, why traditional editorial process needs an upgrade, paperpal’s new ai research finder empowers authors to..., what is hedging in academic writing , how to use ai to enhance your college..., ai + human expertise – a paradigm shift..., how to use paperpal to generate emails &..., ai in education: it’s time to change the..., is it ethical to use ai-generated abstracts without....

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

The Research Proposal

83 Components of the Literature Review

Krathwohl (2005) suggests and describes a variety of components to include in a research proposal. The following sections present these components in a suggested template for you to follow in the preparation of your research proposal.

Introduction

The introduction sets the tone for what follows in your research proposal – treat it as the initial pitch of your idea. After reading the introduction your reader should:

- Understand what it is you want to do;

- Have a sense of your passion for the topic;

- Be excited about the study´s possible outcomes.

As you begin writing your research proposal it is helpful to think of the introduction as a narrative of what it is you want to do, written in one to three paragraphs. Within those one to three paragraphs, it is important to briefly answer the following questions:

- What is the central research problem?

- How is the topic of your research proposal related to the problem?

- What methods will you utilize to analyze the research problem?

- Why is it important to undertake this research? What is the significance of your proposed research? Why are the outcomes of your proposed research important, and to whom or to what are they important?

Note : You may be asked by your instructor to include an abstract with your research proposal. In such cases, an abstract should provide an overview of what it is you plan to study, your main research question, a brief explanation of your methods to answer the research question, and your expected findings. All of this information must be carefully crafted in 150 to 250 words. A word of advice is to save the writing of your abstract until the very end of your research proposal preparation. If you are asked to provide an abstract, you should include 5-7 key words that are of most relevance to your study. List these in order of relevance.

Background and significance

The purpose of this section is to explain the context of your proposal and to describe, in detail, why it is important to undertake this research. Assume that the person or people who will read your research proposal know nothing or very little about the research problem. While you do not need to include all knowledge you have learned about your topic in this section, it is important to ensure that you include the most relevant material that will help to explain the goals of your research.

While there are no hard and fast rules, you should attempt to address some or all of the following key points:

- State the research problem and provide a more thorough explanation about the purpose of the study than what you stated in the introduction.

- Present the rationale for the proposed research study. Clearly indicate why this research is worth doing. Answer the “so what?” question.

- Describe the major issues or problems to be addressed by your research. Do not forget to explain how and in what ways your proposed research builds upon previous related research.

- Explain how you plan to go about conducting your research.

- Clearly identify the key or most relevant sources of research you intend to use and explain how they will contribute to your analysis of the topic.

- Set the boundaries of your proposed research, in order to provide a clear focus. Where appropriate, state not only what you will study, but what will be excluded from your study.

- Provide clear definitions of key concepts and terms. As key concepts and terms often have numerous definitions, make sure you state which definition you will be utilizing in your research.

Literature Review

This is the most time-consuming aspect in the preparation of your research proposal and it is a key component of the research proposal. As described in Chapter 5 , the literature review provides the background to your study and demonstrates the significance of the proposed research. Specifically, it is a review and synthesis of prior research that is related to the problem you are setting forth to investigate. Essentially, your goal in the literature review is to place your research study within the larger whole of what has been studied in the past, while demonstrating to your reader that your work is original, innovative, and adds to the larger whole.

As the literature review is information dense, it is essential that this section be intelligently structured to enable your reader to grasp the key arguments underpinning your study. However, this can be easier to state and harder to do, simply due to the fact there is usually a plethora of related research to sift through. Consequently, a good strategy for writing the literature review is to break the literature into conceptual categories or themes, rather than attempting to describe various groups of literature you reviewed. Chapter V, “ The Literature Review ,” describes a variety of methods to help you organize the themes.

Here are some suggestions on how to approach the writing of your literature review:

- Think about what questions other researchers have asked, what methods they used, what they found, and what they recommended based upon their findings.

- Do not be afraid to challenge previous related research findings and/or conclusions.

- Assess what you believe to be missing from previous research and explain how your research fills in this gap and/or extends previous research

It is important to note that a significant challenge related to undertaking a literature review is knowing when to stop. As such, it is important to know how to know when you have uncovered the key conceptual categories underlying your research topic. Generally, when you start to see repetition in the conclusions or recommendations, you can have confidence that you have covered all of the significant conceptual categories in your literature review. However, it is also important to acknowledge that researchers often find themselves returning to the literature as they collect and analyze their data. For example, an unexpected finding may develop as one collects and/or analyzes the data and it is important to take the time to step back and review the literature again, to ensure that no other researchers have found a similar finding. This may include looking to research outside your field.

This situation occurred with one of the authors of this textbook´s research related to community resilience. During the interviews, the researchers heard many participants discuss individual resilience factors and how they believed these individual factors helped make the community more resilient, overall. Sheppard and Williams (2016) had not discovered these individual factors in their original literature review on community and environmental resilience. However, when they returned to the literature to search for individual resilience factors, they discovered a small body of literature in the child and youth psychology field. Consequently, Sheppard and Williams had to go back and add a new section to their literature review on individual resilience factors. Interestingly, their research appeared to be the first research to link individual resilience factors with community resilience factors.

Research design and methods

The objective of this section of the research proposal is to convince the reader that your overall research design and methods of analysis will enable you to solve the research problem you have identified and also enable you to accurately and effectively interpret the results of your research. Consequently, it is critical that the research design and methods section is well-written, clear, and logically organized. This demonstrates to your reader that you know what you are going to do and how you are going to do it. Overall, you want to leave your reader feeling confident that you have what it takes to get this research study completed in a timely fashion.

Essentially, this section of the research proposal should be clearly tied to the specific objectives of your study; however, it is also important to draw upon and include examples from the literature review that relate to your design and intended methods. In other words, you must clearly demonstrate how your study utilizes and builds upon past studies, as it relates to the research design and intended methods. For example, what methods have been used by other researchers in similar studies?

While it is important to consider the methods that other researchers have employed, it is equally important, if not more so, to consider what methods have not been employed but could be. Remember, the methods section is not simply a list of tasks to be undertaken. It is also an argument as to why and how the tasks you have outlined will help you investigate the research problem and answer your research question(s).

Tips for writing the research design and methods section:

- Specify the methodological approaches you intend to employ to obtain information and the techniques you will use to analyze the data.

- Specify the research operations you will undertake and he way you will interpret the results of those operations in relation to the research problem.

- Go beyond stating what you hope to achieve through the methods you have chosen. State how you will actually do the methods (i.e. coding interview text, running regression analysis, etc.).

- Anticipate and acknowledge any potential barriers you may encounter when undertaking your research and describe how you will address these barriers.

- Explain where you believe you will find challenges related to data collection, including access to participants and information.

Preliminary suppositions and implications

The purpose of this section is to argue how and in what ways you anticipate that your research will refine, revise, or extend existing knowledge in the area of your study. Depending upon the aims and objectives of your study, you should also discuss how your anticipated findings may impact future research. For example, is it possible that your research may lead to a new policy, new theoretical understanding, or a new method for analyzing data? How might your study influence future studies? What might your study mean for future practitioners working in the field? Who or what may benefit from your study? How might your study contribute to social, economic, environmental issues? While it is important to think about and discuss possibilities such as these, it is equally important to be realistic in stating your anticipated findings. In other words, you do not want to delve into idle speculation. Rather, the purpose here is to reflect upon gaps in the current body of literature and to describe how and in what ways you anticipate your research will begin to fill in some or all of those gaps.