Mass Media Roles in Climate Change Mitigation

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 13 October 2016

- Cite this reference work entry

- Kristen Alley Swain 4

6067 Accesses

2 Citations

News media portrayals of climate change have strongly influenced personal and global efforts to mitigate it through news production, individual media consumption, and personal engagement. This chapter explores the media framing of climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies, including the effects of media routines, factors that drive news coverage, the influences of claims-makers, scientists, and other information sources, the role of scientific literacy in interpreting climate change stories, and specific messages that mobilize action or paralysis. It also examines how journalists often explain complex climate science and legitimize sources, how audiences process competing messages about scientific uncertainty, how climate stories compete with other issues for public attention, how large-scale economic and political factors shape news production, and how the media can engage public audiences in climate change issues.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Media Framing of Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation

Bennett ( 2002 ), Kenix ( 2008 )

Shanahan ( 2007 ), Boykoff and Roberts ( 2007 ), Hulme ( 2006 ), Ungar ( 1992 )

Carpenter ( 2002 ), Uusi-Rauva ( 2010 )

Shanahan ( 2007 ), Stern ( 2006 )

Moser ( 2014 a)

Gushee ( 2004 ), Weart ( 2009 )

Boykoff and Roberts ( 2007 ), Weart ( 2009 )

Ungar ( 1992 ), Weisskopf ( 1988 ), Boykoff and Roberts ( 2007 )

Trumbo ( 1996 ), Boykoff and Boykoff ( 2004 ), Gelbspan ( 1998 ), Schneider ( 2001 )

Weart ( 2009 ), Boykoff and Roberts ( 2007 ), Luganda ( 2005 )

Thompson ( 2009 ), Brainard ( 2007a )

Brainard ( 2007b )

Brainard ( 2007c )

Russell ( 2008 )

Goidel et al. ( 2012 )

Moser ( 2014 )

Boykoff et al. ( 2013 )

Good ( 2008 ), Herman and Chomsky ( 1988 )

Gamson et al. ( 1992 ), Price et al. ( 2005 )

Entman ( 1993 ), Hart ( 2010 )

Listerman ( 2010 ), Gamson and Modigliani ( 1989 )

Takahashi ( 2010 ), Dirikx and Gelders ( 2010 )

Garcia ( 2010 )

Shove ( 2010 ), Weaver et al. ( 2009 ), Whitmarsh ( 2009 )

Lakoff ( 2004 )

Woods et al. ( 2010 ), Stewart et al. ( 2009 )

Lakoff ( 2004 ), Schottland ( 2010 )

Boykoff and Roberts ( 2007 ), Herrmann ( 2007 )

Carvalho and Burgess ( 2005 ), Weintraub ( 2007 ), Agarwal and Narain ( 1991 ), Boykoff and Roberts ( 2007 ), Antilla ( 2010 ), Koteyko ( 2010 )

Boykoff ( 2008 ), Nisbet ( 2011 ), Hilgartner and Bosk ( 1988 )

Shanahan ( 2007 ), Walton ( 2007 )

Manzo ( 2010 ), Soroka et al. ( 2009 ), Shanahan and Good ( 2000 )

Carvalho ( 2010 ), Nisbet ( 2008 ), Painter ( 2007 ), Futerra Sustainability Communications ( 2006 ), Institute for Public Policy Research ( 2006 )

Farbotko ( 2005 ), Jay and Marmot ( 2009 ), Leiserowitz ( 2005 ), Maibach et al. ( 2010 )

Shanahan ( 2007 ), Liu et al. ( 2009 ), Carvalho ( 2010 ), Moeller ( 2008 )

Kitzinger ( 2006 ), Nisbet et al. ( 2003 )

Nisbet and Huge ( 2006 )

McComas and Shanahan ( 1999 ), Downs ( 1972 )

Boykoff and Roberts ( 2007 ), Downs ( 1972 , pp. 39–41)

Dunlap ( 1992 ), Brossard et al. ( 2004 ), Jordan and O’Riordan ( 2000 ), Boykoff and Roberts ( 2007 )

Boykoff and Roberts ( 2007 )

Smith ( 2005 )

Takahashi and Meisner ( 2013 )

Asplund et al. ( 2013 )

Pike et al. ( 2012 )

Ruddell et al. ( 2012 )

Capstick et al. ( 2013 )

Reser et al. ( 2012 )

Funfgeld and McEvoy ( 2011 )

Tribbia and Moser ( 2008 )

Spence and Pidgeon ( 2010 )

Brown et al. ( 2011 )

Moser ( 2012 )

Mellman ( 2011 )

ecoAmerica ( 2012 )

Smith and Jenkins ( 2013 )

Resource Media ( 2009 )

Australian Department of Climate Change ( 2009 )

Shearer and Rood ( 2011 )

Gavin et al. ( 2010 ), Resource Media (2012)

Connor and Higginbotham ( 2013 )

Resource Media (2012)

Adger et al. ( 2007 )

Brooks et al. ( 2005 )

Doultona and Brown ( 2009 )

Farbotko ( 2005 )

Barnett et al. ( 2013 )

O’Brien et al. ( 2006 )

Maibach et al. ( 2011a , b )

Anderson et al. ( 2013 )

Corfee-Morlot et al. ( 2007 )

Gavin et al. ( 2010 )

Dow ( 2010 )

Fitzsimmons et al. ( 2012 ), Greenberg ( 2013 )

Fitzsimmons ( 2012 )

Major and Atwood ( 2004 ), Kitzinger ( 2006 ), Brainard ( 2006a )

Bickerstaff et al. ( 2008 ), Yearley ( 2009 ), Sonnett ( 2010 ), Durfee ( 2006 ), Kahlor and Rosenthal ( 2009 )

Lorenzoni and Hulme ( 2009 ), Brody et al. ( 2008 ), Zhao ( 2009 )

Herzog et al. ( 2005 ), Bell ( 1994a )

Lorenzoni and Pidgeon ( 2006 ), The Nielsen Company ( 2007 ), Leiserowitz ( 2005 ), National Science Board ( 2008 )

Boykoff and Roberts ( 2007 ), Will ( 2009 ), Leiserowitz ( 2005 )

Marlowe ( 2005 ), Kim ( 2010 )

Nisbet ( 2006 ), Slovic ( 1987 ), Weintraub ( 2007 ), Krosnick and Holbrook ( 2006 ), Antilla ( 2010 )

Jasanoff ( 1997 ), Leiserowitz ( 2006 ), Baron ( 2006 )

Soman et al. ( 2005 )

Smith and Leiserowitz ( 2012 )

Evans et al. ( 2014 )

Calkins and Zlatoper ( 2001 )

Carrico et al. ( 2014 )

Foust and O’Shannon ( 2009 )

Boykoff ( 2008 ), Hansen ( 1994 ), Anderson ( 2009 ), Boykoff and Roberts ( 2007 )

Einsiedel ( 1992 ), Pellechia ( 1997 )

Fedler and Bender ( 1997 ), Dunwoody and Griffin ( 1993 ), Boykoff and Roberts ( 2007 ), Harbinson et al. ( 2006 ), Hilgartner and Bosk ( 1988 , p. 62), Wilkins and Patterson ( 1987 ), Ereaut and Segnit ( 2006 ), Wilson ( 2000a )

Wilson ( 2002 ), Wilson ( 2000b ), Bell ( 1994b ), Sundblad et al. ( 2009 )

Kitzinger ( 2006 ), Yaros ( 2006 ), Plate ( 2009 )

Harbinson et al. ( 2006 )

Detjen et al. ( 2000 ), Ryan et al. ( 1998 ), Stempel and Culberston ( 1984 ), Roscho ( 1975 ), Meyer ( 1988 ), Mooney ( 2009 )

Nisbet ( 2015 )

Hansen ( 1994 ), Flynn ( 2002 )

Boykoff ( 2007 ), Plate ( 2009 ), Miller and Riechert ( 2000 ), McManus ( 2000 ), Pidgeon and Gregory ( 2004 ), Lorenzoni and Pidgeon ( 2006 ), Trumbo ( 1996 ), McCright and Dunlap ( 2003 ), Leiserowitz ( 2005 ), McCright and Dunlap ( 2000 ), Freudenburg ( 2000 )

McKnight ( 2010 ), Stocking and Holstein ( 2009 )

Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists ( 2010 ), McCright and Dunlap ( 2000 , 2003 ), Wilkins ( 1993 )

Newell ( 2000 ), Hulme ( 2006 ), Ereaut and Segnit ( 2006 ), Will ( 2009 )

Brittle and Muthuswamy ( 2009 ), Wilson (2000), Farnsworth and Lichter ( 2009 )

Yankelovich ( 2003 )

Grundmann ( 2006 ), Boykoff and Roberts ( 2007 ), Brittle ( 2005 ), Carvalho ( 2007 )

Will ( 2009 ), Mooney ( 2009 )

Brittle ( 2005 )

Hulme and Mahony ( 2010 ), Freudenburg and Musellia ( 2010 )

Harbinson et al. ( 2006 ), Weingart et al. ( 2000 ), Carvalho and Burgess ( 2005 ), Brainard ( 2006b )

Jennings and Hulme ( 2010 )

Pollack ( 2003 ), Demeritt ( 2001 ), Zehr ( 2000 ), Wilkins ( 1993 ), Zehr ( 1999 ), McCright ( 2007 ), Schneider ( 1993 ), Dunwoody ( 1999 ), Corbett and Durfee ( 2004 )

Gushee ( 2004 ), Brittle ( 2005 )

Entman ( 1989 ), Dunwoody and Peters ( 1992 ), Kitzinger ( 2006 ), Mooney ( 2009 )

Boykoff and Roberts ( 2007 ), Cunningham ( 2003 ), Augoustinos et al. ( 2010 )

Gordon et al. ( 2010 ), Kuban ( 2007 ), Boykoff and Boykoff ( 2004 )

Boykoff ( 2007 ), Shanahan ( 2007 ), Banning ( 2009 ), Anderson ( 2009 )

Revkin ( 2007 ), Boykoff and Rajan ( 2007 ), Lee and Yoo ( 2004 ), Andreadis and Smith ( 2007 )

Shanahan ( 2007 ), Columbia Journalism Review editors ( 2009 )

Shanahan ( 2007 ), Brainard ( 2007d )

Miller ( 2004 ), Gavin et al. ( 2010 )

Shanahan ( 2007 ), McComas and Shanahan ( 1999 ), Brainard ( 2007e ), Collins and Evans ( 2002 ), Beck ( 1992 )

HSBC ( 2007 ), Painter ( 2007 ), Shanahan ( 2007 ), Soroka ( 2002 ), Trumbo ( 1996 ), Plate ( 2009 ), Lowi ( 1972 )

Priest ( 2006 ), Beck ( 2010 )

Stamm et al. ( 2000 ), Bord et al. ( 2000 ), Ungar ( 2000 ), Nisbet and Goidel ( 2007 ), Zia and Todd ( 2010 ), Mooney ( 2009 )

Evans and Durant ( 1995 )

Miller ( 2004 )

Sturgis and Allum ( 2004 ), Eden ( 1996 ), Nisbet and Scheufele ( 2009 ), Rowe et al. ( 2005 ), Hall et al. ( 2010 )

Kerr et al. ( 1998 ), Olausson ( 2009 ), Irwin ( 2001 ), Nisbet and Kotcher ( 2009 )

Ockwell et al. ( 2009 )

Myers et al. ( 2012 )

Akerlof et al. ( 2010 ), Nisbet et al. ( 2010a )

Kreps and Maibach ( 2008 ), Maibach et al. ( 2008 ), Abroms and Maibach ( 2008 )

Nisbet ( 2009 ), Ho et al. ( 2008 )

O’Neill and Nicholson-Cole ( 2009 ), Lowe et al. ( 2006 ), Höijer ( 2010 )

Nisbet et al. ( 2010b )

Pielke et al. ( 2007 ), Ruhl ( 2010 )

Victor et al. ( 2012 )

Bratt ( 1999 ), Thøgersen ( 1999 ), Tiefenbeck et al. ( 2013 ), Truelove et al. ( 2015 )

Zhong et al. ( 2009 )

Weber ( 1997 )

Weber ( 1997 , 2006 )

Chilvers et al. ( 2014 )

Lawrence ( 2009 )

Fried ( 2000 )

Agyeman et al. ( 2009 )

van der Werff et al. ( 2013 )

Wolf et al. ( 2013 )

Burley et al. ( 2007 )

Whitmarsh ( 2008 )

Schweizer et al. ( 2013 )

Carbaugh and Cerulli ( 2013 )

Moser ( 2013 )

Ogalleh et al. ( 2012 )

Harvatt et al. ( 2011 )

Bray and Martinez ( 2011 )

DARA ( 2012 )

Wynne ( 1993 ), Yankelovich ( 2003 )

Nisbet ( 2011 )

Abroms L, Maibach E (2008) The effectiveness of mass communication to change public behavior. Annu Rev Public Health 29:1–16

Article Google Scholar

Adger WN et al (2007) Climate change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. In: Parry M, Canziani O, Palutikof J, van der Linden P, Hanson C (eds) Contribution of Working Group II to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 717–743

Google Scholar

Agarwal A, Narain S (1991) Global warming in an unequal world: a case of environmental colonialism. Center for Science and Environment, New Delhi

Agyeman J, Devine-Wright P, Prange J (2009) Close to the edge, down by the river? Joining up managed retreat and place attachment in a climate changed world. Environ Plan 41:509–513

Akerlof K, DeBono R, Berry P, Leiserowitz A, Roser-Renouf C, Clarke KL, Rogaeva A, Nisbet MC, Weathers MR, Miabach EW (2010) Public perceptions of climate change as a human health risk: surveys of the United States, Canada and Malta. Int J Environ Res Public Health 7(6):2559–2606

Anderson A (2009) Media, politics and climate change: towards a new research agenda. Sociol Compass 3(2):166–182

Anderson AA, Myers TA, Maiback E, Cullen H, Gandy J, Witte J, Stenhouse N, Leiserowitz A (2013) If they like you, they learn from you: how a brief weathercaster-delivered climate education segment is moderated by viewer evaluations of the weathercaster. Weather Clim Soc 5:367–377

Andreadis E, Smith J (2007) Beyond the ozone layer. Br Journal Rev 18(1):50–56

Antilla L (2010) Self-censorship and science: a geographical review of media coverage of climate tipping points. Public Underst Sci 19:240–256

Asplund T, Hjerpe M, Wibeck V (2013) Framings and coverage of climate change in Swedish specialized farming magazines. Clim Chang 117:197–209

Augoustinos M, Crabb S, Shepherd R (2010) Genetically modified food in the news: media representations of the GM debate in the UK. Public Underst Sci 19:98–114

Australian Department of Climate Change (2009) Climate change adaptation actions for local government. Department of Climate Change, Government of Australia, Canberra

Banning ME (2009) When poststructural theory and contemporary politics collide: the vexed case of global warming. Commun Crit/Cult Stud 6(3):285–304

Barnett J, O’Neill S, Waller S, Rogers S (2013) Reducing the risk of maladaptation in response to sea-level rise and urban water scarcity. In: Moser SC, Boykoff MT (eds) Successful adaptation to climate change: linking science and policy in a rapidly changing world. Routledge, London, pp 37–49

Baron J (2006) Thinking about global warming. Climatic Change 77(1):137–150

Beck U (1992) Risk society: towards a new modernity. Sage, London

Beck U (2010) Climate for change, or how to create a green modernity? Theory Cult Soc 27(2–3):254–266

Bell A (1994a) Climate of opinion: public and media discourse on the global environment. Discourse Soc 5(1):33–64

Bell A (1994b) Media (mis)communication on the science of climate change. Public Underst Sci 3(3):259–275

Bennett WL (2002) News: the politics of illusion. Longman, New York, p 10

Bickerstaff K, Lorenzoni I, Pidgeon NF, Poortinga W, Simmons P (2008) Reframing nuclear power in the UK energy debate: nuclear power, climate change mitigation and radioactive waste. Public Underst Sci 17(2):145–169

Bord RJ, O’Connor RE, Fisher A (2000) In what sense does the public need to understand global climate change? Public Underst Sci 9:205–218

Boykoff MT (2007) Flogging a dead norm? Newspaper coverage of anthropogenic climate change in the United States and United Kingdom from 2003–2006. Area 39(4):470–481

Boykoff MT (2008) Media and scientific communication: a case of climate change. Geol Soc Lond Spec Publ 305:11–18

Boykoff MT, Boykoff JM (2004) Bias as balance: global warming and the U.S. prestige press. Glob Environ Chang 14(2):125–136

Boykoff MT, Rajan SR (2007) Signals and noise: mass-media coverage of climate change in the USA and the UK. Eur Mol Biol Organ Rep 8(3):1–5

Boykoff MT, Roberts JT (2007) Media coverage of climate change: current trends, strengths, weaknesses. United Nations Development Programme. http://hdr.undp.org/fr/rapports/mondial/rmdh2007-2008/documents/Boykoff,%20Maxwell%20and%20Roberts,%20J.%20Timmons.pdf

Boykoff MT, Ghosh A, Venkateswaran K (2013) Media coverage on adaptation: competing visions of “success” in the Indian context. In: Moser SC, Boykoff MT (eds) Successful adaptation to climate change: linking science and practice in a rapidly changing world. Routledge, London, pp 237–252

Brainard C (2006a) Inhofe, climate change and those alarmist reporters. Columbia Journalism Review. www.cjr.org/behind_the_news/inhofe_climate_change_and_thos.php

Brainard C (2006b) A reporting error frozen in time? Columbia Journalism Review, Sept. www.cjr.org/behind_the_news/a_reporting_error_frozen_in_ti.php

Brainard C (2007a) Environmental journalism? Environmentalism? Columbia Journalism Review, Sept. www.cjr.org/behind_the_news/environmental_journalism_envir.php

Brainard C (2007b) Chinese pollution in words, pictures and more. Columbia Journalism Review. http://www.cjr.org/behind_the_news/chinese_pollution_in_words_pic.php

Brainard C (2007c) Climate goes prime-time with Couric. Columbia Journalism Review. www.cjr.org/campaign_desk/climate_goes_primetime_with_co.php

Brainard C (2007d) Rolling Stone breaks climate news! Well, sort of…. Columbia Journalism Review, July. www.cjr.org/behind_the_news/rolling_stone_breaks_climate_n.php

Brainard C (2007e) For ABC, weather equals climate change. Columbia Journalism Review, Feb. www.cjr.org/behind_the_news/for_abc_weather_equals_climate.php

Bratt C (1999) Consumers’ environmental behavior: generalized, sector-based, or compensatory? Environ Behav 31(1):28–44

Bray D, Martinez G (2011) A survey of the perceptions of regional political decision makers concerning climate change and adaptation in the German Baltic Sea region, vol 50. International BALTEX Secretariat, Helmholtz-Zentrum Geesthacht, Centre for Materials and Coastal Research, Geesthacht

Brittle C (2005) Global warnings! The impact of scientific elite disagreement on public opinion. Doctoral dissertation, University of Michigan

Brittle C, Muthuswamy N (2009) Scientific elites and concern for global warming: the impact of disagreement, evidence strength, partisan cues, and exposure to news content on concern for global warming. Int J Sustain Commun 4:23–44

Brody SD, Zahran S, Vedlitz A, Grover H (2008) Examining the relationship between physical vulnerability and public perceptions of global climate change in the United States. Environ Behav 40(1):72–95

Brooks N, Adger WN, Kelly PM (2005) The determinants of vulnerability and adaptive capacity at the national level and the implications for adaptation. Glob Environ Chang 15:151–163

Brossard D, Shanahan J, McComas K (2004) Are issue-cycles culturally constructed? A comparison of French and American coverage of global climate change. Mass Commun Soc 7(3):359–377

Brown T, Budd L, Bell M, Rendell H (2011) The local impact of global climate change: reporting on landscape transformation and threatened identity in the English regional newspaper press. Public Underst Sci 20:658–673

Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (2010) Michael E. Mann: a scientist in the crosshairs of climate-change denial. Bull At Sci 66(6):1–7

Burley D, Jenkins P, Laska S, Davis T (2007) Place attachment and environmental change in coastal Louisiana. Organ Environ 20:347–366

Calkins LN, Zlatoper TJ (2001) The effects of mandatory seat belt laws on motor vehicle fatalities in the United States. Soc Sci Q 82(4):716–732

Capstick S, Pidgeon N, Whitehead M (2013) Public perceptions of climate change in Wales: summary findings of a survey of the Welsh public conducted during November and December 2012. Climate Change Consortium of Wales, Cardiff

Carbaugh D, Cerulli T (2013) Cultural discourses of dwelling: investigating environmental communication as a place-based practice. Environ Commun 7:4–23

Carpenter C (2002) Businesses, green groups and the media: the role of non-governmental organizations in the climate change debate. Int Aff 77(2):313–328

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Carrico AR, Truelove HB, Vandenbergh MP, Dana D (2014) Does learning about climate change adaptation change support for mitigation? J Environ Psychol 41:19–29

Carvalho A (2007) Ideological cultures and media discourses on scientific knowledge: re-reading news on climate change. Public Underst Sci 16:223–243

Carvalho A (2010) Media(ted)discourses and climate change: a focus on political subjectivity and (dis)engagement. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Chang 1(2):172–179

Carvalho A, Burgess J (2005) Cultural circuits of climate change in UK broadsheet newspapers, 1985–2003. Risk Anal 25(6):1457–1469

Chilvers J, Lorenzoni I, Terry G, Buckley P, Pinnegar JK, Gelcich S (2014) Public engagement with marine climate change issues: (Re)framings, understandings and responses. Glob Environ Chang 29:165–179

Collins HM, Evans R (2002) The third wave of science studies: studies of expertise and experience. Soc Stud Sci 32(2):235–296

Columbia Journalism Review editors (2009) Newsweek, API, and ethics. Columbia Journalism Review, Nov. http://www.cjr.org/news_meeting/newsweek_api_and_ethics.php

Connor LH, Higginbotham N (2013) “Natural cycles” in lay understandings of climate change. Global Environ Change 23(6):1852

Corbett JB, Durfee JL (2004) Testing public (un)certainty of science: media coverage of new and controversial science. In: Friedman SM, Dunwoody S, Rogers CL (eds) Communicating uncertainty: media coverage of new and controversial science. Erlbaum, Mahwah, pp 3–22

Corfee-Morlot J, Maslin M, Burgess J (2007) Global warming in the public sphere. Philos Trans R Soc A Math Phys Eng Sci 365:2741–2776

Cunningham B (2003) Re-thinking objectivity. Columbia Journal Rev 42(2):24–32

DARA (2012) Climate vulnerability monitor: a guide to the cold calculus of a hot planet. DARA and the Climate Vulnerable Forum. http://daraint.org/climate-vulnerability-monitor/climate-vulnerability-monitor-2012/

Demeritt D (2001) The construction of global warming and the politics of science. Ann Assoc Am Geogr 91(2):307–337

Detjen J, Fico F, Li X, Kim Y (2000) Changing work environment of environmental reporters. Newsp Res J 21:2–25

Dirikx A, Gelders D (2010) To frame is to explain: a deductive frame-analysis of Dutch and French climate change coverage during the annual UN Conferences of the Parties. Public Underst Sci 19:732–742

Doultona H, Brown K (2009) Ten years to prevent catastrophe? Discourses of climate change and international development in the UK press. Glob Environ Chang 19:191–202

Dow K (2010) News coverage of drought impacts and vulnerability in the U.S. Carolinas, 1998–2007. Nat Hazards 54:497–518

Downs A (1972) Up and down with ecology: the issue-attention cycle. Public Interest 28:38–50

Dunlap RE (1992) Trends in public opinion toward environmental issues: 1965–1992. Soc Nat Resour 4(3):285–312

Dunwoody S (1999) Scientists, journalists, and the meaning of uncertainty. In: Friedman SM, Dunwoody S, Rogers CL (eds) Communicating uncertainty: Media coverage of new and controversial science. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Dunwoody S, Griffin RJ (1993) Journalistic strategies for reporting long-term environmental issues: a case study of three superfund sites. In: Hansen A (ed) The mass media and environmental issues. Leicester University Press, Leicester, pp 22–50

Dunwoody S, Peters HP (1992) Mass media coverage of technological and environmental risks. Public Underst Sci 1(2):199–230

Durfee JL (2006) “Social change” and “status quo” framing effects on risk perception: an exploratory experiment. Sci Commun 27(4):459–495

ecoAmerica (2012) Changing season, changing lives: new realities, new opportunities. Leadership summit report. ecoAmerica, Washington, DC

Eden S (1996) Public participation in environmental policy: considering scientific, counter-scientific and non-scientific contributions. Public Underst Sci 5:183–204

Einsiedel EF (1992) Framing science and technology in the Canadian press. Public Underst Sci 1:89–101

Entman RM (1989) Democracy without citizens: media and the decay of American politics. Oxford University Press, New York

Entman RM (1993) Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J Commun 43:51–58

Ereaut G, Segnit N (2006) Warm words: how are we telling the climate story and can we tell it better. Institute for Public Policy Research. London, England

Evans G, Durant J (1995) The relationship between knowledge and attitudes in the public understanding of science in Britain. Public Underst Sci 4:57–74

Evans L, Milfont TL, Lawrence J (2014) Considering local adaptation increases willingness to mitigate. Glob Environ Chang 25:69–75

Farbotko C (2005) Tuvalu and climate change: constructions of environmental displacement in the Sydney Morning Herald. Geografiska Annaler Ser B Hum Geogr 87(4):279–293

Farnsworth SJ, Lichter SR (2009) The structure of evolving U.S. scientific opinion on climate change and its potential consequences. American Political Science Association, Toronto

Fedler F, Bender JR (1997) Reporting for the media. Harcourt Brace, Fort Worth

Fitzsimmons J (2012) Media begin to connect the dots between climate change and wildfires. Media Matters for America, Washington, DC

Fitzsimmons J, Fong J, Johnson M, Theel S (2012) Media avoid climate context in wildfire coverage. Media Matters for America, Washington, DC

Flynn T (2002) Source credibility and global warming: a content analysis of environmental groups. Paper presented to the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication convention. Miami Beach, FL

Foust CR, O’Shannon MW (2009) Revealing and reframing apocalyptic tragedy in global warming discourse. Environ Commun 3:151–167

Freudenburg WR (2000) Social construction and social constrictions: toward analyzing the social construction of ‘The Naturalized’ and well as ‘The Natural’. In: Spaargaren G, Mol APJ, Buttel FH (eds) Environment and global modernity. Sage, London, pp 103–119

Chapter Google Scholar

Freudenburg WR, Musellia V (2010) Global warming estimates, media expectations, and the asymmetry of scientific challenge. Glob Environ Chang 20(3):483–491

Fried M (2000) Continuities and discontinuities of place. J Environ Psychol 20:193–205

Funfgeld H, McEvoy D (2011) Framing climate change adaptation in policy and practice. Victorian Centre for Climate Change Adaptation Research, Victoria, Australia

Futerra Sustainability Communications (2006) Climate fear vs. climate hope: are the UK’s national newspapers helping tackle climate change? Futerra report. http://www.docstoc.com/docs/28404782/Fear-or-hope

Gamson WA, Modigliani A (1989) Media discourse and public opinion on nuclear power: a constructionist approach. Am J Sociol 95(1):1–37

Gamson WA, Croteau D, Hoynes W, Sasson T (1992) Media images and the social construction of reality. Annu Rev Sociol 18:373–393

Garcia D (2010) Warming to a redefinition of international security: the consolidation of a norm concerning climate change. Int Relat 24(3):271–292

Gavin NT, Leonard-Milsom L, Montgomery J (2010) Climate change, flooding and the media in Britain. Public Underst Sci 20:422–438

Gelbspan R (1998) The heat is on: the climate crisis, the cover-up, the prescription. New York, NY: Perseus Press

Goidel K, Kenny C, Climek M, Means M, Swann L, Sempier T, Schneider M (2012) 2012 Gulf coast climate change survey: Norman, OK: Southern Climate Impacts Planning Program

Good JE (2008) The framing of climate change in Canadian, American and international newspapers: a media propaganda model analysis. Can J Commun 33(2)

Gordon JC, Deines T, Havice J (2010) Global warming coverage in the media: trends in a Mexico City newspaper. Sci Commun 32:143–170

Greenberg M (2013) Media still largely fail to put wildfires in climate context. Media Matters for America, Washington, DC

Grundmann R (2006) Ozone and climate: scientific consensus and leadership. Sci Technol Human Values 31(1):73–101

Gushee DE (2004) CAIChE offers technological insights to the public policy debate on global climate change. Environ Prog 19(3):F2–F4

Hall NL, Taplin R, Goldstein W (2010) Empowerment of individuals and realization of community agency: applying action research to climate change responses in Australia. Action Res 8(1):71–91

Hansen A (1994) Journalistic practices and science reporting in the British press. Public Underst Sci 3:111–134

Harbinson R, Mugara R, Chawla A (2006) Whatever the weather: media attitudes to reporting on climate change. Panos Institute, London

Hart PS (2010) One or many? The influence of episodic and thematic climate change frames on policy preferences and individual behavior change. Sci Commun 33(1):28–51

Harvatt J, Petts J, Chilvers J (2011) Understanding householder responses to natural hazards: flooding and sea-level rise comparisons. J Risk Res 14:63–83

Herman ES, Chomsky N (1988) Manufacturing consent: the political economy of the mass media. Pantheon Books, New York

Herrmann S (2007) Climate sceptics. BBC News. www.tinyurl.com/2fd54u .

Herzog HJ, Curry TE et al (2005) Climate change survey. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Boston

Hilgartner S, Bosk CL (1988) The rise and fall of social problems: a public arenas model. Am J Sociol 94(1):53–78

Ho SS, Brossard D, Scheufele DA (2008) Effects of value predispositions, mass media use, and knowledge on public attitudes toward embryonic stem cell research. Int J Public Opin Res 20(2):171–192

Höijer B (2010) Emotional anchoring and objectification in the media reporting on climate change. Public Underst Sci 19(6):717–731

HSBC (2007) HSBC climate confidence index. HSBC Holdings, London, http://www.hsbc.com/1/PA_1_1_S5/content/assets/newsroom/hsbc_ccindex_p8.pdf

Hulme M (November 4, 2006) Chaotic world of climate truth. BBC News. Available at: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/6115644.stm

Hulme M, Mahony M (2010) Climate change: what do we know about the IPCC? Prog Phys Geogr 34(5):705–718

Institute for Public Policy Research (2006) Warm words: how are we telling the climate story and can we tell it better? IPPR, London, http://www.ippr.org.uk/ecomm/files/warm_words.pdf

Irwin A (2001) Constructing the scientific citizen: science and democracy in the biosciences. Public Underst Sci 10:1–18

Jasanoff S (1997) Civilization and madness: the great BSE scare of 1996. Public Underst Sci 6:221–232

Jay M, Marmot MG (2009) Health and climate change: will a global commitment be made at the UN climate change conference in December? Br Med J 339:645–646

Jennings N, Hulme M (2010) UK newspaper (mis)representations of the potential for a collapse of the Thermohaline Circulation. Area 42(4):444–456

Jordan A, O’Riordan T (2000) Environmental politics and policy processes. In: O’Riordan T (ed) Environmental science for environmental management. Prentice Hall. New York, NY: Routledge

Kahlor L, Rosenthal S (2009) If we seek, do we learn? Predicting knowledge of global warming. Sci Commun 30:380–414

Kenix LJ (2008) Framing science: climate change in the mainstream and alternative news of New Zealand. Polit Sci 60(1):117–132

Kerr A, Cunningham-Burley S, Amos A (1998) The new genetics and health: mobilizing lay expertise. Public Underst Sci 7:41–60

Kim KS (2010) Public understanding of the politics of global warming in the news media: the hostile media approach. Public Underst Sci 20(5):690–705

Kitzinger J (2006) The role of media in public engagement. In: Turney J (ed) Engaging science: thoughts, deeds, analysis and action. Wellcome Trust, London, pp 44–49, http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/seind08/pdf/c07.pdf

Koteyko N (2010) From carbon markets to carbon morality: creative compounds as framing devices in online discourses on climate change mitigation. Sci Commun 32(1):25–54

Kreps G, Maibach E (2008) Transdisciplinary science: the nexus between communication and public health. J Commun 58:732–748

Krosnick JA, Holbrook AL (2006) The origins and consequences of democratic citizens’ policy agendas: a study of popular concern about global warming. Clim Chang 77(1):7–43

Kuban A (2007) The U.S. broadcast news media as a social arena in the global climate change debate. Master’s thesis, Iowa State University

Lakoff G (2004) Don’t think of an elephant: know your values and frame the debate. Chelsea Green, White River Junction

Lawrence A (2009) The first cuckoo in winter: phenology, recording, credibility and meaning in Britain. Glob Environ Chang 19:173–179

Lee G, Yoo CY (2004) Attribute salience transfer of global warming issue from online papers to the public. Paper presented to the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication convention, Toronto

Leiserowitz A (2005) American risk perceptions: is climate change dangerous? Risk Anal 25(6):1433–1442

Leiserowitz A (2006) Climate change risk perception and policy preferences: the role of affect, imagery, and values. Clim Chang 77(1):45–72

Listerman T (2010) Framing of science issues in opinion-leading news: international comparison of biotechnology issue coverage. Public Underst Sci 19(1):5–15

Liu X, Lindquist E, Vedlitz A (2009) Explaining media and congressional attention to global climate change, 1969–2005: an empirical test of agenda-setting theory. Polit Res Q 64(2):405–419

Lorenzoni I, Hulme M (2009) Believing is seeing: laypeople’s views of future socio-economic and climate change in England and in Italy. Public Underst Sci 18:383–400

Lorenzoni I, Pidgeon NF (2006) Public views on climate change: European and USA perspectives. Clim Chang 77(1):73–95

Lowe T, Brown K, Dessai S, de França Doria M, Haynes K, Vincent K (2006) Does tomorrow ever come? Disaster narrative and public perceptions of climate change. Public Underst Sci 15(4):435–457

Lowi TJ (1972) Four systems of policy, politics, and choice. Public Adm Rev 32(4):298–310

Luganda P (2005) Communication critical in mitigating climate change in Africa. Open meeting of the International Human Dimensions Programme, Bonn

Maibach E, Roser-Renouf C, Leiserowitz A (2008) Communication and marketing as climate change intervention assets: a public health perspective. Am J Prev Med 35(5):488–500

Maibach EW, Nisbet M, Baldwin MP, Akerlof K, Diao G (2010) Reframing climate change as a public health issue: an exploratory study of public reactions. Biomed Central Public Health 10:299

Maibach E, Cobb S, Leiserowitz A, Peters E, Schweizer V, Mandryk C, Witte J, Bonney R, Cullen H, Straus D et al (2011a) A national survey of television meteorologists about climate change education. Center for Climate Change Communication, George Mason University, Fairfax

Maibach E, Witte J, Wilson K (2011b) “Climategate” undermined belief in global warming among many American TV meteorologists. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 92:31–37

Major AM, Atwood LE (2004) Environmental risks in the news: issues, sources, problems, and values. Public Underst Sci 13:295–308

Manzo K (2010) Beyond polar bears? Re-envisioning climate change. Meteorol Appl 17(2):196–208

Marlowe E (2005) Seeing red in green news: credibility and perceived bias in environmental news articles. Master’s thesis, University of Missouri

McComas K, Shanahan J (1999) Telling stories about global climate change: measuring the impact of narratives on issue cycles. Commun Res 26(1):30–57

McCright AM (2007) Dealing with climate contrarians. In: Moser SC, Dilling L (eds) Creating a climate for change: communicating climate change and facilitating social change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, MA

McCright AM, Dunlap RE (2000) Challenging global warming as a social problem: an analysis of the conservative movement’s counter-claims. Soc Probl 47(4):499–522

McCright AM, Dunlap RE (2003) Defeating Kyoto: the conservative movement’s impact on U.S. climate change policy. Soc Probl 50(3):348–373

McKnight D (2010) A change in the climate? The journalism of opinion at News Corporation. Journalism 11(6):693–706

McManus PA (2000) Beyond Kyoto? Media representation of an environmental issue. Aust Geogr Stud 38(3):306–319

Mellman M (2011) Preparing for a changing climate: observations from focus groups and interviews. The Mellman Group, Washington, DC

Meyer P (1988) Defining and measuring credibility of newspapers: developing an index. Journal Q 65(567–574):588

Miller JD (2004) Public understanding of, and attitudes toward, scientific research: what we know and what we need to know. Public Underst Sci 13:273–294

Miller MM, Riechert BP (2000) Interest group strategies and journalistic norms: news media framing of environmental issues. In: Allan S, Adam B, Carter C (eds) Environmental risks and the media. Routledge, London, pp 45–54

Moeller SD (2008) Considering the media’s framing and agenda-setting roles in states’ responsiveness to natural crises and disasters. Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy, Cambridge, MA, http://www.hks.harvard.edu/fs/pnorris/Conference/Conference%20papers/Moeller.pdf

Mooney C (2009) Climate change myths and facts. Washington Post, 21 Mar

Moser SC (2012) Adaptation, mitigation, and their disharmonious discontents. Clim Chang 111:165–175

Moser SC (2013) Navigating the political and emotional terrain of adaptation: community engagement when climate change comes home. In: Moser SC, Boykoff MT (eds) Successful adaptation to climate change: linking science and policy in a rapidly changing world. Routledge, London, pp 289–305

Moser SC (2014) Communicating adaptation to climate change: the art and science of public engagement when climate change comes home. WIREs Clim Change 5(3):337–358

Myers TA, Nisbet MC, Maibach EW, Anthony A, Leiserowitz AA (2012) A public health frame arouses hopeful emotions about climate change. Clim Chang 113(3–4):1105

National Science Board (2008) Science and technology: public attitudes and understanding. In: Science and Engineering Indicators 2008. National Science Board, Arlington, http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/seind08/pdf/c07.pdf

Newell P (2000) Climate for change: non-state actors and the global politics of the greenhouse. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, MA, p 152

Book Google Scholar

Nielsen Company (2007) Global Omnibus Survey. New York: AC Nielsen

Nisbet MC (2006) Does the public believe Inhofe’s hype? Framing Science blog, Sept. http://scienceblogs.com/framing-science/2006/09/does_the_public_believe_inhofe.php

Nisbet MC (2008) Time magazine’s “reported analysis” of global warming. Framing Science. http://scienceblogs.com/framing-science/2008/04/time_magazines_reported_analys.php

Nisbet MC (2009) Communicating climate change: why frames matter for public engagement. Environment. http://www.environmentmagazine.org/Archives/Back%20Issues/March-April%202009/Nisbet-full.html

Nisbet MC (2011) Climate change enters downward cycle in news attention as dramatic storytelling potential wanes. Big Think. http://bigthink.com/ideas/26410

Nisbet MC (2015) Disruptive ideas: public intellectuals and their arguments for action on climate change. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Chang 5(6):809–823

Nisbet MC, Goidel RK (2007) Understanding citizen perceptions of science controversy: bridging the ethnographic-survey research divide. Public Underst Sci 16(4):421–440

Nisbet MC, Huge M (2006) Attention cycles and frames in the plant biotechnology debate: managing power and participation through the press/policy connection. Int J Press/Polit 11(2):3–40

Nisbet MC, Kotcher JE (2009) A two-step flow of influence? Opinion-leader campaigns on climate change. Sci Commun 30(3):328–354

Nisbet MC, Scheufele DA (2009) What’s next for science communication? Promising directions and lingering distractions. Am J Bot 96:1767–1778

Nisbet MC, Brossard D, Kroepsch A (2003) Framing science: the stem cell controversy in an age of press/politics. Int J Press/Polit 8(2):36–70

Nisbet MC, Price S, Pascual-Ferra P, Maibach E (2010a) Communicating the public health relevance of climate change: a news agenda building analysis. Working paper. American University, Washington, DC. http://scienceblogs.com/framing-science/Nisbet_etal_(2010)_NewsCoverageClimateChangePublicHealth_WorkingPaper.pdf

Nisbet MC, Hixon M, Moore KD, Nelson M (2010b) The four cultures: new synergies for engaging society on climate change. Front Ecol Environ 8:329–331

O’Brien K, Eriksen S, Sygna L, Naess LO (2006) Questioning complacency: climate change impacts, vulnerability, and adaptation in Norway. Ambio 35:50–56

O’Neill S, Nicholson-Cole S (2009) “Fear won’t do it”: promoting positive engagement with climate change through visual and iconic representations. Sci Commun 30(3):355–379

Ockwell D, Whitmarsh L, O’Neill S (2009) Reorienting climate change communication for effective mitigation: forcing people to be green or fostering grass-roots engagement? Sci Commun 30(3):305–327

Ogalleh S, Vogl C, Eitzinger J, Hauser M (2012) Local perceptions and responses to climate change and variability: the case of Laikipia District, Kenya. Sustainability 4:3302–3325

Olausson U (2009) Global warming: global responsibility? Media frames of collective action and scientific certainty. Public Underst Sci 18:421–436

Painter J (2007) All doom and gloom? International TV coverage of the April and May 2007 IPCC reports. http://www.tinyurl.com/2qd7ky

Pellechia MG (1997) Trends in science coverage: a content analysis of three U.S. newspapers. Public Underst Sci 6:49–68

Pidgeon N, Gregory R (2004) Judgment, decision-making and public policy. In: Handbook of judgment and decision making. Blackwell, Oxford, UK, pp 604–623

Pielke R, Prins G, Rayner S, Sarewitz D (2007) Climate change 2007: lifting the taboo on adaptation. Nature 445:597–598

Pike C, Hyde K, Herr M, Minkow D, Doppelt B (2012) Climate communication and engagement efforts: the landscape of approaches and strategies. A Report to the Skoll Global Threats Fund. The Resource Innovation Group’s Social Capital Project, Eugene

Plate T (2009) An (oil) peak too high. Columbia Journalism Review, Oct. www.cjr.org/the_kicker/when_newsweek_met_oil_lobby.php

Pollack H (2003) Can the media help science? Skeptic 10(2):73–80

Price V, Nir L, Capella JN (2005) Framing public discussion of gay civil unions. Public Opin Q 69(2):179–212

Priest SH (2006) Public discourse and scientific controversy: a spiral-of-silence analysis of biotechnology opinion in the United States. Sci Commun 28(2):195–215

Reser JP, Bradley GL, Glendon AI, Ellul MC, Callaghan R (2012) Public risk perceptions, understandings and responses to climate change and natural disasters in Australia and Great Britain: final report. Griffith University, Australia: National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility

Resource Media (2009). Communicating Climate Change and Water Linkages in the West — Guidelines and Toolkit. Available at: http://www.carpediemwest.org/wp-content/uploads/Western_Water_and_Climate_Change_Communications_Guidelines-WEB.pdf

Revkin A (2007) Climate change as news: challenges in communicating environmental science. In: DiMento JC, Doughman PM (eds) Climate change: what it means for us, our children, and our grandchildren. MIT Press, Boston, pp 139–160

Roscho B (1975) Newsmaking. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Rowe G, Horlick-Jones T, Walls J, Pidgeon N (2005) Difficulties in evaluating public engagement initiatives: reflections on an evaluation of the UK GM Nation? Public debate about transgenic crops. Public Underst Sci 14:331–352

Ruddell D, Harlan S, Grossman-Clarke S, Chowell G (2012) Scales of perception: public awareness of regional and neighborhood climates. Clim Chang 111:581–607

Ruhl J (2010) Climate change adaptation and the structural transformation of environmental law. Environ Law 363:365–375

Russell C (2008) Climate change: now what? Columbia Journalism Review. www.cjr.org/feature/climate_change_now_what.php

Ryan C, Carrage KM, Schwerner C (1998) Media movements and the quest for social justice. J Appl Commun Res 26:165–181

Schneider SH (1993) Degrees of certainty. Res Explor 9(2):173–181

Schneider SS (2001) A constructive deconstruction of deconstructionists: a response to Demeritt. Ann Assoc Am Geogr 91(2):338–344

Schottland T (2010) Climate security: how to frame a winning argument. It’s Getting Hot in Here (blog). http://itsgettinghotinhere.org/2010/02/20/climate-security-how-to-frame-a-winning-argument/

Schweizer S, Davis S, Thompson JL (2013) Changing the conversation about climate change: a theoretical framework for place-based climate change engagement. Environ Commun 7:42–62

Shanahan M (2007) Talking about a revolution: climate change and the media. International Institute for Environment and Development. http://www.iied.org/pubs/pdfs/17029IIED.pdf

Shanahan J, Good J (2000) Heat and hot air: influence of local temperature on journalists’ coverage of global warming. Public Underst Sci 9:285–295

Shearer C, Rood RB (2011) Changing the media discussion on climate and extreme. Weather. earthzine (blog). http://www.earthzine.org/2011/04/17/changing-the-media-discussion-on-climate-and-extreme-weather/

Shove E (2010) Social theory and climate change: questions often, sometimes and not yet asked. Theory Cult Soc 27(2–3):277–288

Slovic P (1987) Perceptions of risk. Science 236:280–285

Smith J (2005) Dangerous news: media decision making about climate change risk. Risk Anal 25(6):1471–1482

Smith A, Jenkins K (2013) Climate change and extreme weather in the USA: discourse analysis and strategies for an emerging “public”. J Environ Stud Sci 3:259–268

Smith N, Leiserowitz A (2012) The rise of global warming skepticism: exploring affective image associations in the United States over time. Risk Anal 32(6):1021–1032

Soman D, Ainslie G, Frederick S, Li X, Lynch J, Moreau P et al (2005) The psychology of intertemporal discounting: why are distant events valued differently from proximal ones? Mark Lett 16(3–4):347–360

Sonnett J (2010) Climates of risk: a field analysis of global climate change in U.S. media discourse, 1997–2004. Public Underst Sci 19(6):698–716

Soroka SN (2002) Agenda-setting dynamics in Canada. UBC Press, Vancouver

Soroka S, Farnsworth SJ, Young L, Lawlor A (2009) Environment and energy policy: comparing reports from U.S. and Canadian network news. American Political Science Association, Toronto

Spence A, Pidgeon N (2010) Framing and communicating climate change: the effects of distance and outcome frame manipulations. Glob Environ Chang 20:656–667

Stamm KR, Clark F, Eblacas PR (2000) Mass communication and public understanding of environmental problems: the case of global warming. Public Understanding of Science 9:219–237

Stempel G, Culberston H (1984) The prominence and dominance of news sources in newspaper medical coverage. Journal Q 61:671–676

Stern N (2006) Stern review on the economics of climate change. HM Treasury, London, http://www.webcitation.org/5nCeyEYJr

Stewart CO, Dickerson DL, Hotchkiss R (2009) Beliefs about science and news frames in audience evaluations of embryonic and adult stem cell research. Sci Commun 30:427–452

Stocking SH, Holstein LW (2009) Manufacturing doubt: journalists’ roles and the construction of ignorance in a scientific controversy. Public Underst Sci 18:23–42

Sturgis P, Allum N (2004) Science in society: re-evaluating the deficit model of public attitudes. Public Underst Sci 13:55–74

Sundblad E, Biel A, Garling T (2009) Knowledge and confidence in knowledge about climate change among experts, journalists, politicians, and laypersons. Environ Behav 41:281–302

Takahashi B (2010) Framing and sources: a study of mass media coverage of climate change in Peru during the V ALCUE. Public Underst Sci 20(4):543–557

Takahashi B, Meisner M (2013) Climate change in Peruvian newspapers: the role of foreign voices in a context of vulnerability. Public Underst Sci 22:427–442

Thøgersen J (1999) Spillover processes in the development of a sustainable consumption pattern. J Econ Psychol 20(1):53–81

Thompson M (2009) Do it for the polar bears: an examination of global warming discussion after Hurricane Katrina. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, Boston. http://www.allacademic.com/meta/p375724_index.html

Tiefenbeck V, Staake T, Roth S (2013) For better or for worse? Empirical evidence of moral licensing in a behavioral energy conservation campaign. Energy Policy 57:160–171

Tribbia J, Moser SC (2008) More than information: what coastal managers need to plan for climate change. Environ Sci Pol 11:315–328

Truelove H, Carrico A, Weber E, Raimi K, Vandenbergh M (2015) Positive and negative spillover of pro-environmental behavior: an integrative review and theoretical framework. Global Environ Change 29:127–138

Trumbo C (1996) Constructing climate change: claims and frames in U.S. news coverage of an environmental issue. Public Underst Sci 5:269–283

Ungar S (1992) The rise and (relative) decline of global warming as a social problem. Sociol Q 33(4):483–501

Ungar S (2000) Knowledge, ignorance and the popular culture: Climate change versus the ozone hole. Public Understanding of Science 9:297–312

Uusi-Rauva C (2010) The EU energy and climate package: a showcase for European environmental leadership? Environ Policy Gov 20(2):73–88

van der Werff E, Steg L, Keizer K (2013) The value of environmental self-identity: the relationship between biospheric values, environmental self-identity and environmental preferences, intentions and behavior. J Environ Psychol 34:55–63

Victor D, Kennell CF, Ramanathan V (2012) The climate threat we can beat. Foreign Aff 119:112–121

Walton J (2007) Making sustainability matter: the effect of message framing on inclination to act. Master’s thesis, Colorado State University

Weart SR (2009) The idea of anthropogenic global climate change in the 20th century. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Chang 1(1):67–81

Weaver DA, Lively E, Bimber B (2009) Searching for a frame: news media tell the story of technological progress, risk, and regulation. Sci Commun 31(2):139–166

Weber E (1997) Perception and expectation of climate change: precondition for economic and technological adaptation. In: Bazerman MH, Messick DM, Tensbrunsel A, Wade-Benzoni K (eds) Psychological perspectives to environmental and ethical issues in management. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, pp 314–341

Weber E (2006) Experience-based and description-based perceptions of long-term risk: why global warming does not scare us (yet). Clim Chang 77(1–2):103–120

Weingart P, Engels A et al (2000) Risks of communication: discourses on climate change in science, politics, and the mass media. Public Underst Sci 9:261–283

Weintraub D (2007) Newspaper coverage of global climate change: risk, frames and sources. Master’s thesis, University of South Carolina

Weisskopf M (1988) Two senate bills take aim at ‘greenhouse effect’. Washington Post, p A17

Whitmarsh L (2008) Are flood victims more concerned about climate change than other people? The role of direct experience in risk perception and behavioural response. J Risk Res 11:351–374

Whitmarsh L (2009) What’s in a name? Commonalities and differences in public understanding of “climate change” and “global warming”. Public Underst Sci 18(4):401–420

Wilkins L (1993) Between facts and values: print media coverage of the greenhouse effect, 1987–1990. Public Underst Sci 2:71–84

Wilkins L, Patterson P (1987) Risk analysis and the construction of news. J Commun 37(3):80–92

Will GF (2009) Climate science in a tornado. Washington Post, 27 Feb

Wilson KM (2000a) Communicating climate change through the media: predictions, politics, and perceptions of risk. In: Allan S, Adam B, Carter C (eds) Environmental risks and the media. Taylor and Francis, London, pp 201–217

Wilson KM (2000b) Drought, debate, and uncertainty: measuring reporters’ knowledge and ignorance about climate change. Public Underst Sci 9:1–13

Wilson KM (2002) Forecasting the future: how television weathercasters–attitudes and beliefs about climate change affect their cognitive knowledge on the science. Sci Commun 24:246–268

Wolf J, Allice I, Bell T (2013) Values, climate change, and implications for adaptation: evidence from two communities in Labrador, Canada. Glob Environ Chang 23:548–562

Woods R, Fernandez A, Coen S (2010) The use of religious metaphors by UK newspapers to describe and denigrate climate change. Public Underst Sci 21:323–339

Wynne B (1993) Public uptake of science: a case for institutional reflexivity. Public Underst Sci 2:321–337

Yankelovich D (2003) Winning greater influence for science. Issues Sci Technol 19(4). http://www.issues.org/19.4/yankelovich.html

Yaros RA (2006) Is it the medium or the message? Structuring complex news to enhance engagement and situational understanding by non-experts. Commun Res 33(4):285–309

Yearley S (2009) Sociology and climate change after Kyoto: what roles for social science in understanding climate change? Curr Sociol 57(3):389–405

Zehr S (1999) Scientists’ representations of uncertainty. Communicating uncertainty: media representations of global warming. Sci Commun 26(2):129

Zehr SC (2000) Public representations of scientific uncertainty about global climate change. Public Underst Sci 9:85–103

Zhao X (2009) Media use and global warming perceptions: a snapshot of the reinforcing spirals. Commun Res 36(5):698–723

Zhong CB, Liljenquist K, Cain D (2009) Moral self-regulation: licensing and compensation. In: de Cremer D (ed) Psychological perspectives on ethical behavior and decision making. Information Age, Charlotte, pp 75–89

Zia A, Todd AM (2010) Evaluating the effects of ideology on public understanding of climate change science: how to improve communication across ideological divides? Public Underst Sci 19(6):743–761

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Meek School of Journalism and New Media, The University of Mississippi, 135 Farley Hall, 38677, Oxford, MS, USA

Kristen Alley Swain

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kristen Alley Swain .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Departmemt of Chemical Engineering, University of Mississippi, Oxford, Mississippi, USA

Wei-Yin Chen

National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science & Technology (AIST), Nagoya, Japan

Toshio Suzuki

Institute of Advanced Engineering Technologies, University of Applied Sciences FH Technikum Wien, Vienna, Austria

Maximilian Lackner

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Swain, K.A. (2017). Mass Media Roles in Climate Change Mitigation. In: Chen, WY., Suzuki, T., Lackner, M. (eds) Handbook of Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-14409-2_6

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-14409-2_6

Published : 13 October 2016

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-14408-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-14409-2

eBook Packages : Energy Reference Module Computer Science and Engineering

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Open supplemental data

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, how academic research and news media cover climate change: a case study from chile.

- 1 Education, Research, and Innovation (ERI) Sector, NEOM, Tabuk, Saudi Arabia

- 2 Departamento de Ciencias del Lenguaje, Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Santiago, Chile

Introduction: Climate change has significant impacts on society, including the environment, economy, and human health. To effectively address this issue, it is crucial for both research and news media coverage to align their efforts and present accurate and comprehensive information to the public. In this study, we use a combination of text-mining and web-scrapping methods, as well as topic-modeling techniques, to examine the similarities, discrepancies, and gaps in the coverage of climate change in academic and general-interest publications in Chile.

Methods: We analyzed 1,261 academic articles published in the Web of Science and Scopus databases and 5,024 news articles from eight Chilean electronic platforms, spanning the period from 2012 to 2022.

Results: The findings of our investigation highlight three key outcomes. Firstly, the number of articles on climate change has increased substantially over the past decade, reflecting a growing interest and urgency surrounding the issue. Secondly, while both news media and academic research cover similar themes, such as climate change indicators, climate change impacts, and mitigation and adaptation strategies, the news media provides a wider variety of themes, including climate change and society and climate politics, which are not as commonly explored in academic research. Thirdly, academic research offers in-depth insights into the ecological consequences of global warming on coastal ecosystems and their inhabitants. In contrast, the news media tends to prioritize the tangible and direct impacts, particularly on agriculture and urban health.

Discussion: By integrating academic and media sources into our study, we shed light on their complementary nature, facilitating a more comprehensive communication and understanding of climate change. This analysis serves to bridge the communication gap that commonly, exists between scientific research and news media coverage. By incorporating rigorous analysis of scientific research with the wider reach of the news media, we enable a more informed and engaged public conversation on climate change.

1. Introduction

Climate change is the most pervasive threat to the world's natural, social, political, and economic systems. Human activities have caused a rise in greenhouse gas (GHG) concentrations in the atmosphere and caused the earth's surface temperature to rise, leading to many other changes around the world—in the atmosphere, on land, and in the oceans ( Wyser et al., 2020 ; Masson-Delmotte et al., 2021 ). Indicators of these changes include increases in global average air and ocean temperature, rising global sea levels ( Zemp et al., 2019 ; Garcia-Soto et al., 2021 ; Oliver et al., 2021 ), amplification of permafrost thawing and glacier retreat ( Sommer et al., 2020 ; Wilkenskjeld et al., 2022 ), reduction of snow and ice cover ( Shepherd et al., 2018 ), ocean acidification ( Doney et al., 2020 ) and stronger and more frequent extreme events such as heatwaves, storms, droughts, wildfires, and flooding ( Abram et al., 2021 ; van der Wiel and Bintanja, 2021 ). These changes are projected to continue throughout at least the rest of this century ( Smale et al., 2019 ; Cook et al., 2020 ; Kwiatkowski et al., 2020 ; Ortega et al., 2021 ). Mitigation and adaptation are two complementary strategies for addressing climate change ( Abubakar and Dano, 2020 ; Diamond et al., 2020 ; Tosun, 2022 ). Mitigation focuses on reducing emissions or enhancing GHG sinks, while adaptation involves building resilience to the unavoidable impacts on people and ecosystems. To be successful, these efforts require a deep scientific understanding, as well as the active engagement of the scientific community, civil society, and other stakeholders ( Wamsler, 2017 ; Tai and Robinson, 2018 ; Gonçalves et al., 2022 ).

News media and academic research have distinct roles in communicating scientific findings on climate change ( Corbett, 2015 ). News media rapidly disseminate scientific findings to a broader audience, shaping public understanding and influencing science-policy translation, practices, politics, public opinion, and understanding of climate change. They select and frame information to shape public awareness and perception, often influenced by various factors such as political, economic, scientific, ecological, or social events. Academic research provides a scientific foundation, evidence-based insights, and focuses on rigorous methodologies, data analysis, and the generation of scientific knowledge related to climate change. Aligning news media and academic research in their coverage is essential for effectively addressing climate change. Consistent messaging and shared thematic structures between media and academia build public trust and understanding, enabling informed decision-making and collective action. However, it's important to acknowledge that variations may exist between news media and academic research coverage due to factors like economic development, political influences, and differing focuses on the societal dimension of climate change ( Hase et al., 2021 ).

Over the past decade, media coverage of climate science has grown in accuracy, though the extent and type of coverage varies between countries and is often connected to political, scientific, ecological, or social events ( Shehata and Hopmann, 2012 ; Schmidt et al., 2013 ; Lopera and Moreno, 2014 ; Schäfer and Schlichting, 2014 ; Stecula and Merkley, 2019 ; Hase et al., 2021 ; Dubash et al., 2022 ). A growing body of experimental research has explored how climate change has been represented in news media ( Dotson et al., 2012 ; Wozniak et al., 2015 ; Barkemeyer et al., 2017 ; Bohr, 2020 ; Keller et al., 2020 ) as well as providing an overview of the state of knowledge on the science of climate change ( Berrang-Ford et al., 2015 ; Pacifici et al., 2015 ; Rojas-Downing et al., 2017 ; Cianconi et al., 2020 ; Fawzy et al., 2020 ; Olabi and Abdelkareem, 2022 ; Talukder et al., 2022 ). As far as we know, however, no previous research has investigated simultaneously news media coverage and academia's research agenda on climate change globally or locally. Therefore, the primary goal of our study is to evaluate, by means of text-mining, web-scraping methods, and topic-modeling techniques, the extent of alignment between news media and academic research in their coverage of climate change topics in the context of Chile. By examining the content and comparing the thematic focus of climate change discourse in both sources, this study will contribute to understanding the similarities, discrepancies, and gaps in the coverage of climate change in Chile. Furthermore, the findings can inform future efforts to improve the alignment and comprehensiveness of climate change communication between news media and academia, ultimately promoting public awareness and understanding of this critical global issue ( Leuzinger et al., 2019 ; Albagli and Iwama, 2022 ).

Chile is particularly interesting as study model due to a variety of political, geographic, ecological, political, and social factors. Despite contributing only 0.23% to global GHG emissions ( Labarca et al., 2023 ), Chile is highly vulnerable to climate change impacts. Evidence of current and future effects of climate change on Chilean territory has been mounting ( Bozkurt et al., 2017 ; Araya-Osses et al., 2020 ; Martínez-Retureta et al., 2021 ), which could have detrimental consequences for citizens' health and wellbeing by impacting key sectors such as fisheries and aquaculture, forestry, agriculture and livestock, mining, energy, and water resources. Additionally, the Government of Chile chaired the 2019 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP25) in Spain ( Navia, 2019 ) and has committed to reducing its GHG emissions by 30% compared to 2007 levels as part of its nationally determined contributions. Previous studies have explored ideological bias in media coverage of climate change in Chile ( Dotson et al., 2012 ), however there is a lack of research comparing academic research with news media. Although this study focuses on climate change in Chile, its results more broadly inform gaps in the coverage of climate change between academic and media discourse and emphasizes the importance of analyzing both sources to improve public understanding of climate change issues.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. academic articles.

The ISI Web of Science WOS Core Collection ( https://apps.webofknowledge.com/ ) and Scopus ( https://www.scopus.com/home.uri ) database were chosen for the collection of academic articles. On January 18, 2023, we retrieved all publications related to climate change in Chile using the following Boolean search strategy: [(climat * chang * OR global chang * OR “climat * emergenc * OR “climat * crisis OR “global warming) AND Chile * ]. A comprehensive search strategy was employed to identify relevant publications from 2012 to 2022, without any language restrictions Following the search based on these criteria, a total of 1,758 articles from Web of Science (WOS) and 1,730 articles from Scopus were retrieved. The search results were downloaded in.xlsx format for further analysis. To ensure data accuracy, a manual comparison was conducted between the SCOPUS and WOS records, which involved examining the title, primary author, source title, and year of publication. All the articles obtained, including their titles and abstracts, were exclusively in English. Duplicate articles were discarded. We next used the title and abstract- when available- of each article to ensure we only included studies aimed at understanding climate change in Chile either by Chilean or international scientists. We include original articles and reviews, but not conference proceedings or books/book chapters, in our analysis. Articles without an abstract were also excluded. This resulted in 1,261 articles used to build the academic corpus, which comprises the following metadata for each document: database, title, abstract, and publication year.

2.2. News media articles

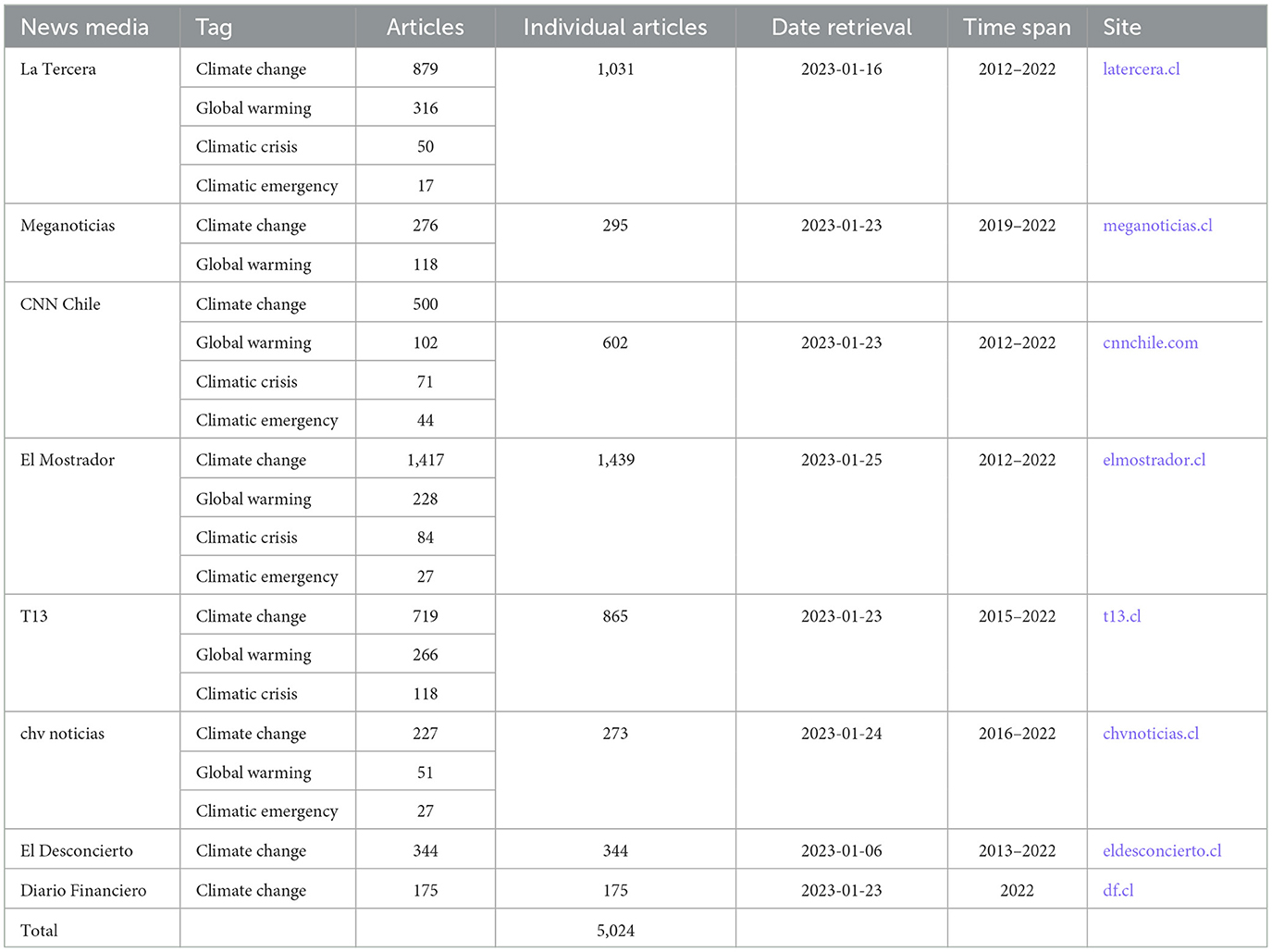

Climate Change coverage from Chilean electronic news platforms was also studied over the 10-year period from 2012 to 2022. This time period was determined by the availability of items on the selected platforms. The sample included eight electronic platforms: La Tercera, Meganoticias, CNN Chile, El Mostrador, T13, CHV Noticias, El Desconcierto and Diario Financiero. The platforms were chosen based on their national coverage, their high circulation and accessibility without a subscription fee. The approach to retrieve the articles was as follows. First, tags directly related to climate change were identified: “climate change,” “global warming,” “climatic crisis,” and “climatic emergency.” This strategy allows for a systematization of sampling. For each article, the name of the media, tag, headline, date, and URL of the source page were retrieved using the Rvest ( Wickham, 2016 ) and RSelenium ( Harrison and Harrison, 2022 ) R-packages. The URLs were then used to extract the articles' full text (body). Those articles that were not retrievable using this method due to forbidden access or any other restrictions in the source page were discarded from the collection. A total of 6,056 news articles were retrieved between January 06 and 15, 2023. Because a news item may include different tags, we removed duplicate articles for each of the platforms. Articles in which the date could not be retrieved were also discarded. After this filtering process, we obtained 5024 articles, which were used to build the news media corpus ( Table 1 ).

Table 1 . Information of electronic platform and news media articles retrieved.

2.3. Preprocessing

The corpora were preprocessed as follows: performing tokenization into unigrams (one word) using the “tidytext” R-package ( Silge and Robinson, 2016 ), normalizing text into lowercase and removing punctuation, symbols, numbers, and HTML tags. English and Spanish lists of stop words were applied to the academic ( Puurula, 2013 ) and news media (a proposed list of Spanish stop-words was used; Díaz, 2016 ) corpus, respectively. Additional terms (e.g., academic corpus: “mission”, “b.v”, “rights”, “reserved”; news media corpus: “tags”, “u-uppercase”, “video”, “cnn”, “iphone”) were added to the list of stop words as frequent words present across many documents that are expected not to be related to any topic and whose presence might hinder the interpretation of the results. Also, plural words were converted to singular (e.g., academic corpus: “glaciers” to “glacier”, “southern” to “south”; news media corpus: “gases” to “gas”, “emissions” to “emission”). To preprocess the corpora, we used the “quanteda” R-package ( Benoit et al., 2018 ).

2.4. Publication trends

The Mann-Kendall trend test was used to detect an increase, decrease or no difference in the number of articles published for both academic and news media corpora. Mann-Kendall test is a distribution-free test that can be used to identify monotonic trends for as few as four samples ( Mann, 1945 ; Kendall, 1975 ). This is relevant for our purposes, given the results of our study were limited by a small sample size ( n = 10). In brief, we tested the null hypothesis if the data are identically distributed (i.e., non-trend). The alternative hypothesis was that the data follow a monotonic trend. This monotonic trend could be positive or negative. We fitted the Mann-Kendall model using the “Kendall” R-package ( McLeod and McLeod, 2015 ).

2.5. LDA topic modeling

Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA), a probabilistic topic-modeling technique, was used to identify the most common topics and themes in both corpora. Briefly, topic modeling is an unsupervised machine learning technique which can identify co-occurring terms and patterns from collections of text documents ( Kherwa and Bansal, 2019 ). Latent LDA is a well-suited unsupervised algorithm for general topic modeling tasks, particularly when dealing with long documents, which is the case with analyzing academic or news media articles ( Anupriya and Karpagavalli, 2015 ; Goyal and Kashyap, 2022 ). LDA is a three-level hierarchical Bayesian model that employs three basic elements, namely the corpus which is constituted from a set of documents that is composed from a group of words ( Blei et al., 2003 ; Blei, 2012 ). LDA can infer probabilistic word clusters, called topics, based on patterns of (co) occurrence of words in the documents that are analyzed. LDA models each document as a mixture of topics and the model generates automatic summaries of topics in terms of a discrete probability distribution over words for each topic, and further infers per-document discrete distributions over topic. LDA output can be used logically to classify the documents according to the topic it belongs to.

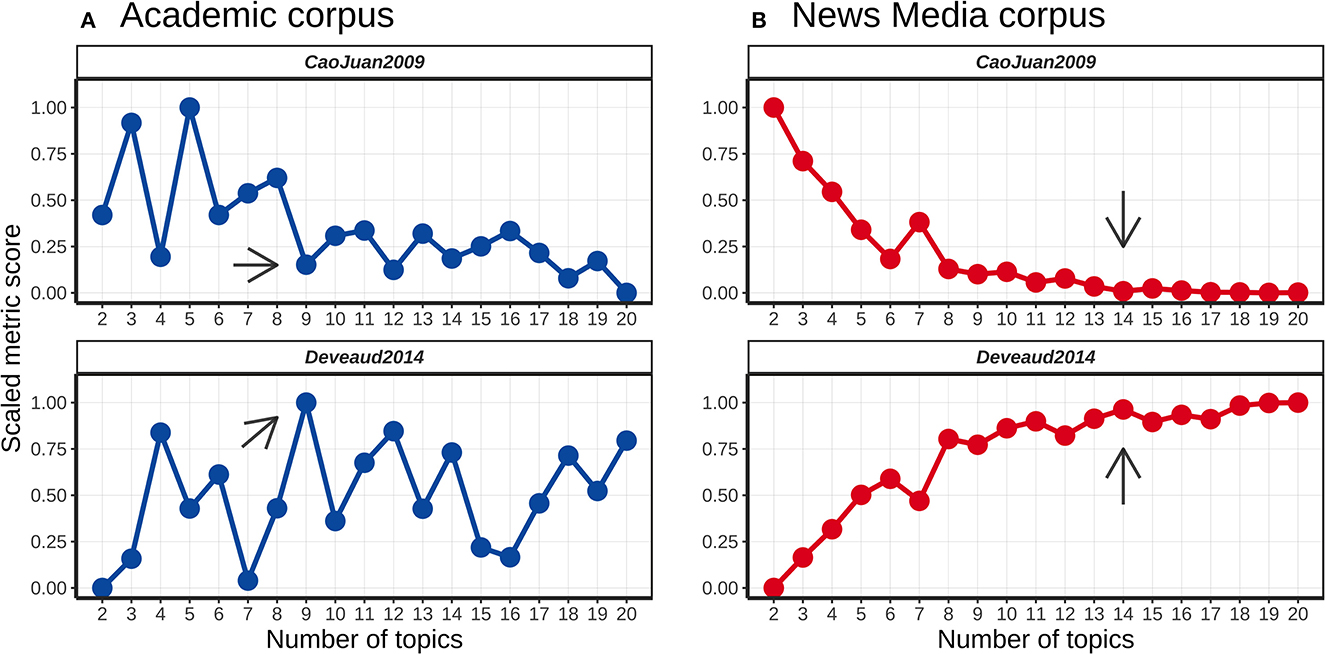

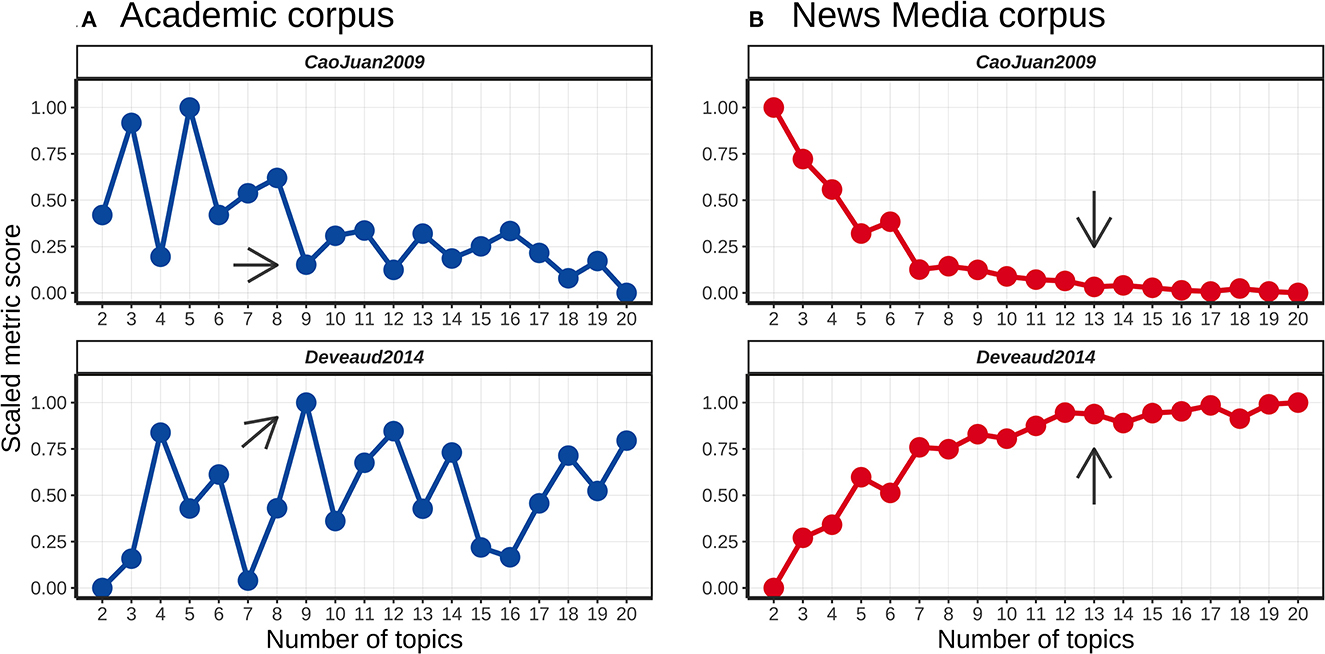

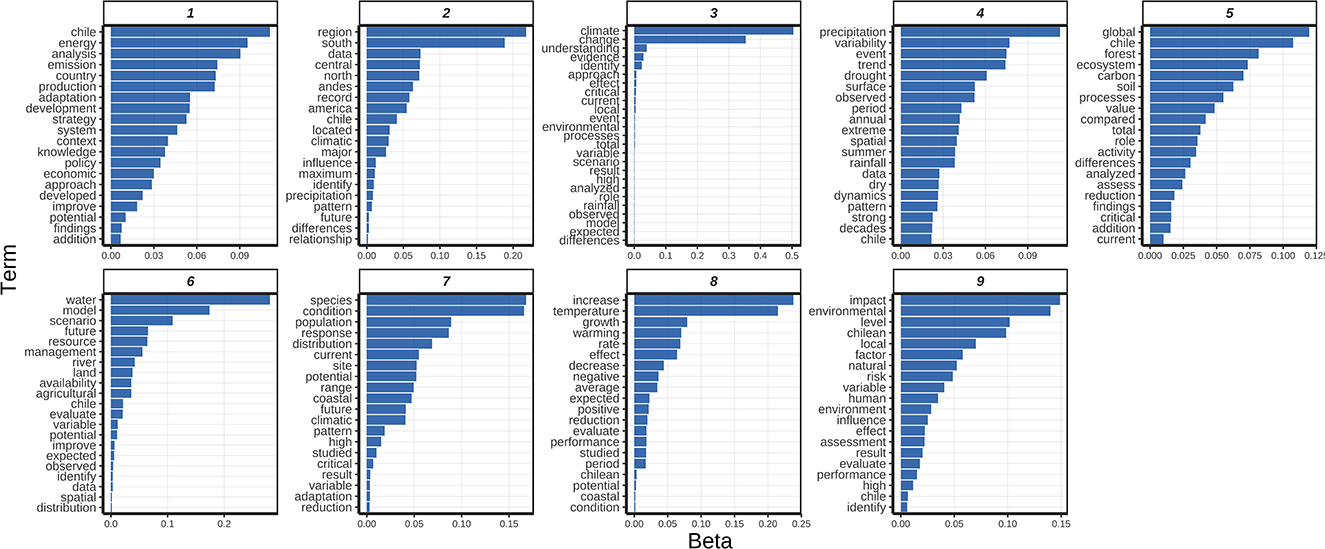

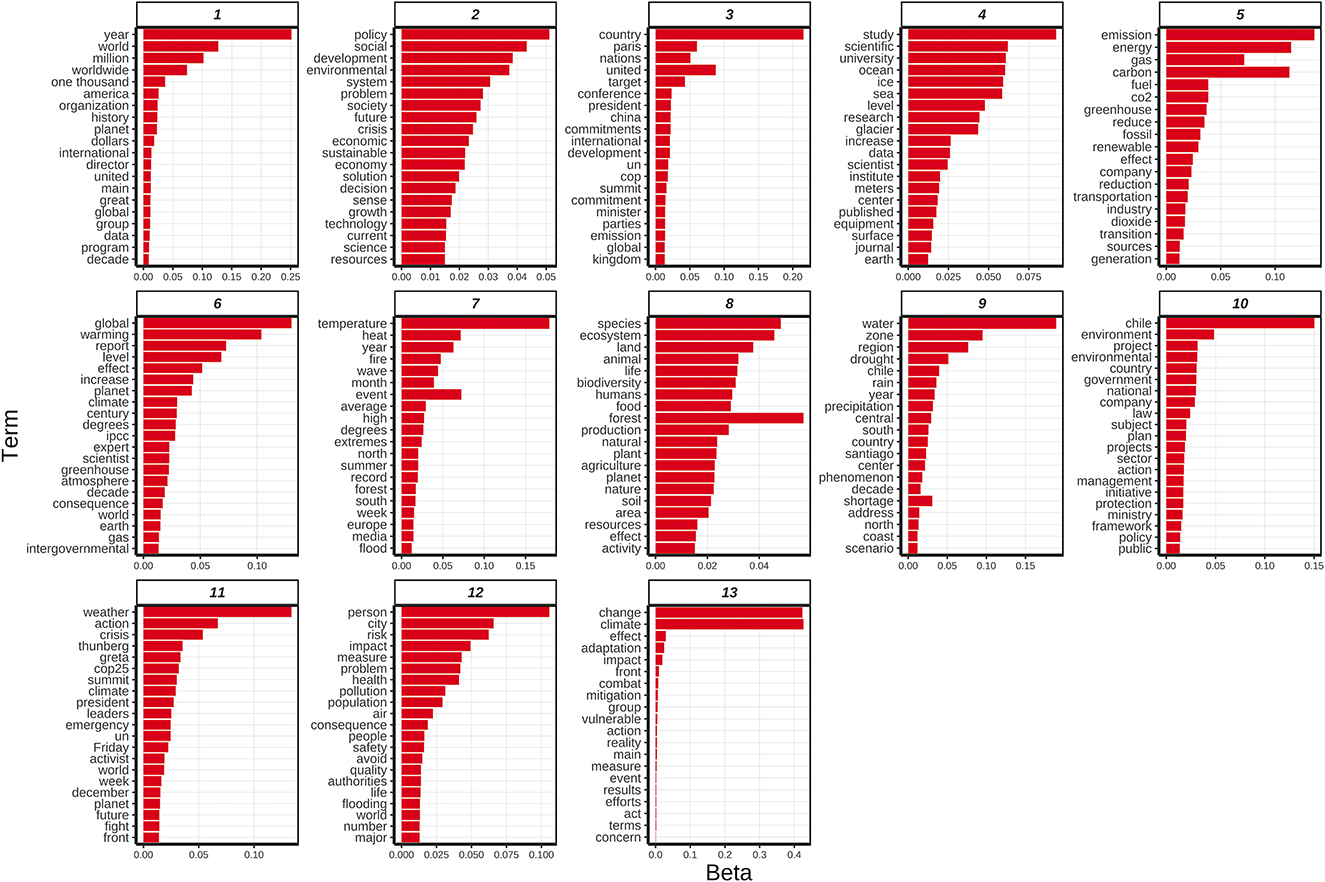

Before performing the LDA, the number of topics needs to be estimated. In this study, we used two metrics from the R-package “ldatuning” ( Nikita, 2016 ): CaoJuan2009 and Deveaud2014. Whereas measure CaoJuan2009 has to be minimized ( Cao et al., 2009 ), Deveaud2014 has to be maximized ( Deveaud et al., 2014 ). Both metrics showed a plateau in the curves at 9 and 13 topics (k) for both academic and news media corpora, respectively ( Figure 1 ). For each corpus, we fitted the LDA model using the “topicmodels” R-package ( Grün and Hornik, 2011 ). The collapsed Gibbs sampling method was used to estimate the LDA parameters with 1,000 iterations for k = 13 and k = 9 topics for academic and news media corpora, respectively). Once generated, we assigned a label that adds an interpretable meaning to each of the inferred topics. It is important to note that the news media corpus was analyzed in its original language (i.e., Spanish), but the results (i.e., topics and themes) are presented in English.

Figure 1 . Suggested number of topics in the (A) academic and (B) news media corpora using the CaoJuan2009 and Deveaud2014 metrics.

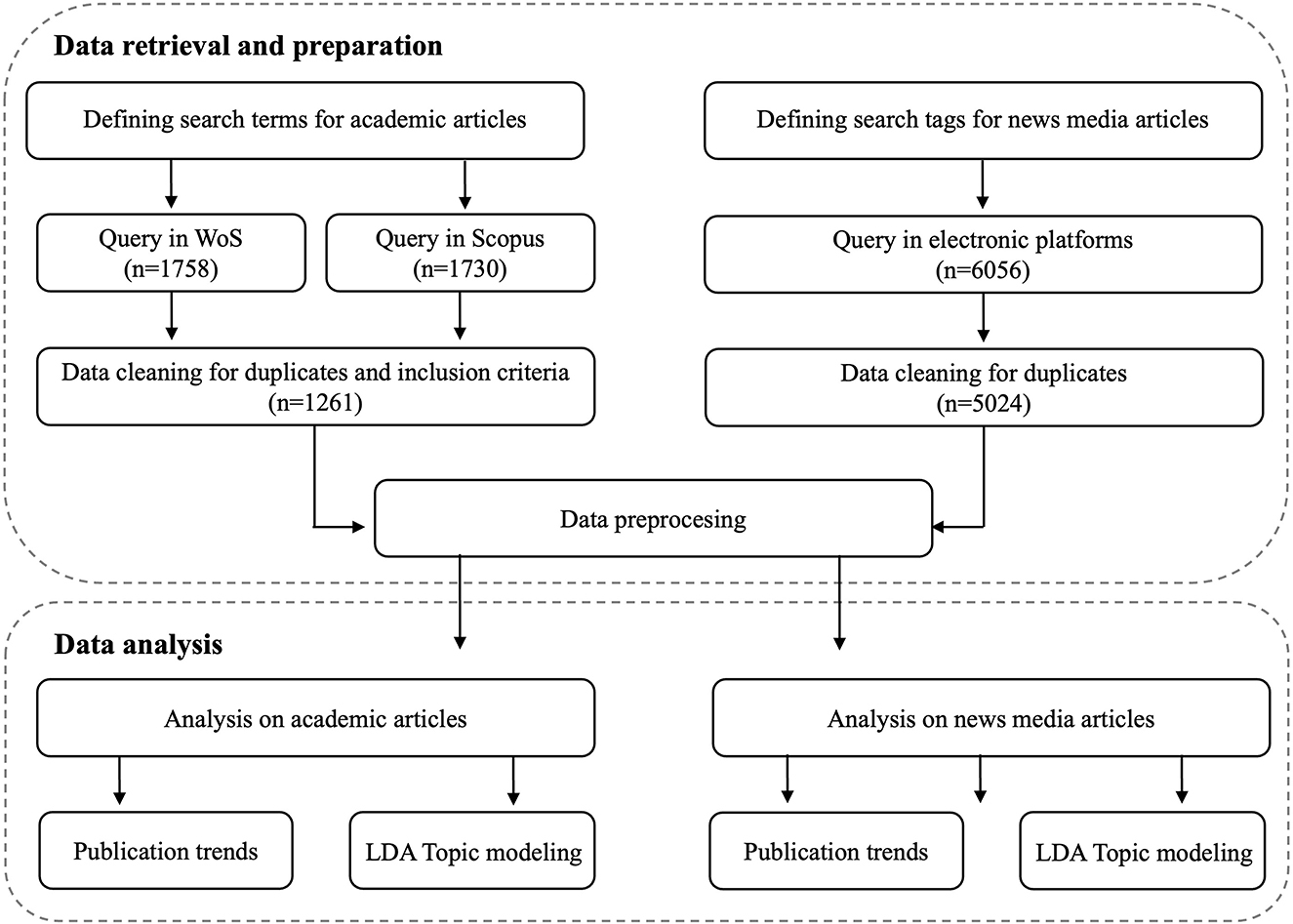

Lastly, we used a variation of Vu et al. (2019) and Keller et al. (2020) procedures to sort the topics into five overarching themes: climate change indicators (e.g., warming, temperature, glaciers, sea-level, oceans, coastal, weather, wildfires, drought, etc.); climate change impacts (e.g., water, food, agriculture, livestock, biodiversity, ecosystems, financial etc.); climate change and society (e.g., health, wellbeing, pollution, education, humanity, population, etc.); climate politics (e.g., government, law, policy, regulation, U.N., COP, agreement, etc.); and addressing climate change (e.g., adaptation, mitigation, action, renewable, GHG, emissions, fuel, management, etc.). Figure 2 summarizes the steps of data retrieval, corpus creation and content analysis.

Figure 2 . Data collection and analysis framework.

2.6. Visualizations

Data visualizations were performed using R ( R Core Team, 2022 ) in conjunction with the software package ggplot2 ( Wickham et al., 2016 ) and dplyr ( Wickham et al., 2022 ).

3.1. Publications trends over 2012–2022 period

National and international authors published 1,261 research academic articles related to climate change in Chile during the 2012–2022 period. More than half of these articles, approximately 66.0%, were published from 2019 onwards. In terms of news media, we retrieved 5,024 articles over the period 2012–2022. Of these articles, 76.6% were published in the past 4 years. Figure 3 shows trends in the number of articles for both the academic and news media corpus. Note that the scales of the y-axis are different between corpora. Mann-Kendall trend analysis showed a significant and upward trend for the number of academic articles (τ = 1, p < 0.01, Figure 3A ) and news media articles (τ = 0.85, p = < 0.05, Figure 3B ) articles. The number of articles published per year follows a similar trend in both corpora, however, news media articles showed a sharp increase in 2019. After these peaks, the number of published media articles decreased before an additional increase was observed.

Figure 3 . Annual trend of (A) academic and (B) news media articles published from 2012 to 2022.

3.2. LDA topic modeling

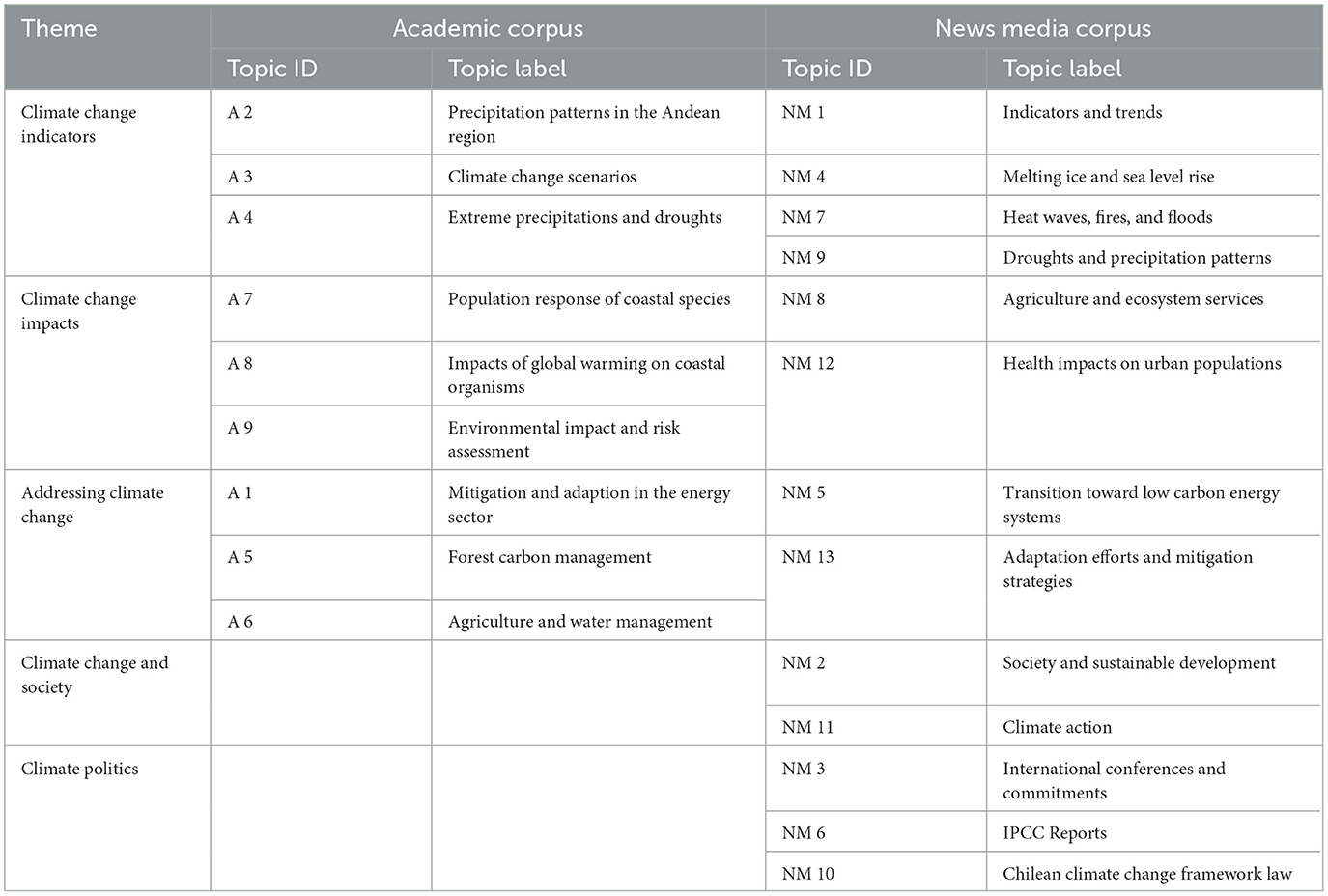

The output of the LDA for the academic and news media corpora are displayed in Table 2 . Topics were labeled based on the top 15 keywords with the largest probabilities in topics vectors ( Figures 4 , 5 ) and content in most relevant articles. In the academic corpus, the nine topics extracted were categorized into three overarching themes: “climate change indicators” (Topic A 2, A3 and A 4), “climate change impacts” (Topics A 7, A 8, and A 9), and “addressing climate change” (Topics A 1, A 5, and A 6). No topics in the academic corpus were classified as “climate change and society” or “climate politics”. The 13 topics extracted from news media corpus were classified in five themes: “climate change indicators” (Topic NM 1, NM 4, NM 7, and NM 9), “climate change impacts” (Topic NM 8 and NM 12), “addressing climate change” (Topics NM 5 and NM 13), “climate change and society” (Topics NM 2 and NM 11), and “climate politics” (Topics NM 6 and NM 10).

Table 2 . Themes, labels, and topics identified by LDA for academic ( n = 9) and news media ( n = 13) corpora.

Figure 4 . Word-topic probability from LDA model in the academic corpus.

Figure 5 . Word-topic probability from LDA model in the news media corpus.

4. Discussion

This study evaluates the extent of alignment between news media and academic research in their coverage of climate change topics in Chile between 2012 and 2022. By comparing two corpora consisting of 1,261 news articles and 5,024 academic articles, this research sheds light on the similarities, discrepancies, and gaps in the coverage of climate change in Chilean academic and general-interest publications. Our analysis revealed three key findings. Firstly, the number of articles on climate change has increased substantially over the past decade, reflecting a growing interest and urgency surrounding the issue. Secondly, while both news media and academic research cover similar themes, such as climate change indicators, climate change impacts and mitigation and adaptation strategies, the news media provides a wider variety of themes, including climate change and society and climate politics, which are not as commonly explored in academic research. Thirdly, academic literature offers in-depth insights into the ecological consequences of global warming on coastal ecosystems and their inhabitants. In contrast, press media tends to prioritize the tangible and direct impacts, particularly on agriculture and urban health. These disparities not only underscore the differing emphases between news media and academic coverage but also illustrate how news media predominantly focuses on the immediate and visible impacts of climate change events.

4.1. Publications trends over 2012–2022 period

Our study explores the coverage of climate change in Chile by news media and research academia during the 2012–2022 period. We found a significant increase in the number of academic and news media articles published on climate change in Chile over the past decade, indicating growing interest and urgency surrounding the issue ( Figure 3 ). The rise in Chilean literature suggests an increased interest by the scientific community in understanding climate change in Chile, which is crucial for understanding global environmental changes and their impacts on natural, social, political, and economic systems. Our findings are consistent with previous studies that have mapped the evolution of climate change science worldwide ( Klingelhöfer et al., 2020 ; Nalau and Verrall, 2021 ; Reisch et al., 2021 ; Rocque et al., 2021 ). The media coverage of climate change in Chile also increased significantly since 2012, reaching a peak during 2019 before decreasing sharply in 2020 and increasing again thereafter. In 2019, the peak coincided with the climate summit (COP 25) held by Chile, generating great interest among civil society, scientists, and the private sector to share their plans for mitigating and adapting to climate change ( Hjerpe and Linnér, 2010 ). This event occurred at the same time as the #FridaysForFuture campaign, which mobilized an unprecedented number of youths worldwide to join the climate movement, including Chile ( Fisher, 2019 ). The campaign was instrumental not only for its potential impact on policy but also for raising public awareness about climate change and promoting action to address it. However, the media landscape experienced a notable shift in priorities due to the global COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic brought about unprecedented challenges and uncertainties, leading to changes in media coverage patterns and public attention. News media had to allocate significant resources to reporting on the pandemic, including public health information, policy responses, and updates on the spread of the virus ( Krawczyk et al., 2021 ; Mach et al., 2021 ). This shift in media priorities affected the extent and prominence of climate change coverage. Consequently, the media coverage of climate change in Chile experienced a temporary decline in 2020. However, as the world gradually adapted to the ongoing pandemic, news media resumed their coverage of climate change, and the topic regained attention. Additionally, the upcoming international conferences, such as COP 26 in England (2021) and COP 27 in Egypt (2022), may have contributed to the increased media coverage observed since 2021, as these events serve as key moments to discuss global climate action.

4.2. LDA topic modeling