What Is the SAT Essay?

College Board

- February 28, 2024

The SAT Essay section is a lot like a typical writing assignment in which you’re asked to read and analyze a passage and then produce an essay in response to a single prompt about that passage. It gives you the opportunity to demonstrate your reading, analysis, and writing skills—which are critical to readiness for success in college and career—and the scores you’ll get back will give you insight into your strengths in these areas as well as indications of any areas that you may still need to work on.

The Essay section is only available in certain states where it’s required as part of SAT School Day administrations. If you’re going to be taking the SAT during school , ask your counselor if it will include the Essay section. If it’s included, the Essay section will come after the Reading and Writing and Math sections and will add an additional 50 minutes .

What You’ll Do

- Read a passage between 650 and 750 words in length.

- Explain how the author builds an argument to persuade an audience.

- Support your explanation with evidence from the passage.

You won’t be asked to agree or disagree with a position on a topic or to write about your personal experience.

The Essay section shows how well you understand the passage and are able to use it as the basis for a well-written, thought-out discussion. Your score will be based on three categories.

Reading: A successful essay shows that you understood the passage, including the interplay of central ideas and important details. It also shows an effective use of textual evidence.

Analysis: A successful essay shows your understanding of how the author builds an argument by:

- Examining the author’s use of evidence, reasoning, and other stylistic and persuasive techniques

- Supporting and developing claims with well-chosen evidence from the passage

Writing: A successful essay is focused, organized, and precise, with an appropriate style and tone that varies sentence structure and follows the conventions of standard written English.

Learn more about how the SAT Essay is scored.

Want to practice? Log in to the Bluebook™ testing application , go to the Practice and Prepare section, and choose full-length practice test . There are 3 practice Essay tests. Once you submit your response, go to MyPractice.Collegeboard.org , where you’ll see your essay, a scoring guide and rubric so that you can score yourself, and student samples for various scores to compare your self-score with a student at the same level.

After the Test

You’ll get your Essay score the same way you’ll get your scores for the Reading and Writing and Math sections. If you choose to send your SAT scores to colleges, your Essay score will be reported along with your other section scores from that test day. Even though Score Choice™ allows you to choose which day’s scores you send to colleges, you can never send only some scores from a certain test day. For instance, you can’t choose to send Math scores but not SAT Essay scores.

Until 2021, the SAT Essay was also an optional section when taking the SAT on a weekend. That section was discontinued in 2021.

If you don’t have the opportunity to take the SAT Essay section as part of the SAT, don’t worry. There are other ways to show your writing skills as part of the work you’re already doing on your path to college. The SAT can help you stand out on college applications , as it continues to measure the writing and analytical skills that are essential to college and career readiness. And, if you want to demonstrate your writing skills even more, you can also consider taking an AP English course .

Related Posts

How to get ready for the digital sat on a school day.

Advanced Placement

What is AP English?

Taking the sat during school, how long does the sat take.

The SAT Essay

Written by tutor ellen s..

The SAT has undergone a significant number of changes over the years, generally involving adjustments in the scoring rubric, and often in response to steadily-declining or increasingly-perfect test scores. When the SAT was changed in 2005, however, they made some significant changes to the test that students see. One of these changes was the addition of the writing section, based on the original SAT II subject test, which includes a timed essay. In including a timed essay on an otherwise multiple-choice test, the SAT throws a problem at students that they are generally unprepared to solve.

Because high school classes usually don’t discuss timed essays, students can have difficulty when faced with the SAT essay. You’ll need a different set of skills to tackle the SAT essay, and ideally a completely separate amount of time to practice those skills. In this lesson I’ll give you an overview of the differences between timed essays and at-home essays, and share my tips for successfully completing a well-organized, well-thought-out SAT essay.

First, the differences. In a timed essay, you’re given the prompt on the spot rather than having an idea of what the topic will be beforehand, as you would if you were writing an essay for an English class. On the SAT, you get one prompt and one prompt only, so you don’t even have the benefit of choosing one that works for you – you have to write about whatever they give you. In addition you’re writing everything out longhand, which eats up more time than you might think and makes it harder to make edits and corrections – particularly if you have bad handwriting and you’re worried about staying legible. And just forget about rearranging paragraphs and reorganizing whole sentences – you’ll never have time for that!

The Difference Between the SAT Essay and At-Home Essays

All of this means that you have to be much more organized right from the get-go than you would be in a natural writing process. You’ll need to read the question, think for a few moments, and then immediately form an opinion so you can start the actual writing as soon as possible. So for all timed essays, and the SAT essay in particular, I strongly emphasize the importance of prewriting. Prewriting can take many forms, from word clouds to concept nets, but for the SAT, I recommend the basic straightforward outline – with a few tweaks. Here’s my formula for SAT essay outlines.

How to Outline Your Essay

First, read the prompt through a couple of times. SAT essay prompts usually follow a set format involving the statement of an opinion, and then asking whether you agree or disagree with that opinion. Let’s take an example from the January 2014 test date, courtesy of the College Board website:

Some see printed books as dusty remnants from the preelectronic age. They point out that electronic books, or e-books, cost less to produce than printed books and that producing them has a much smaller impact on natural resources such as trees. Yet why should printed books be considered obsolete or outdated just because there is something cheaper and more modern? With books, as with many other things, just because a new version has its merits doesn’t mean that the older version should be eliminated.

Assignment: Should we hold on to the old when innovations are available, or should we simply move forward? Plan and write an essay in which you develop your point of view on this issue. Support your position with reasoning and examples taken from your reading, studies, experience, or observations. ( Source. )

he first thing I recommend when confronted with an SAT essay prompt is to ask yourself the question “Do I agree or disagree with the premise of the prompt?” That’ll usually be the last sentence of the first paragraph in the prompt. In this case, do you agree that “just because a new version has its merits doesn’t mean that the older version should be eliminated”? Now write the phrase “I agree” or “I disagree” at the top of your scratch paper accordingly. Put some asterisks around it so you remember to keep checking back in with it during the writing. This opinion is the most important part of your essay, so you want it to be clear in your mind. Next, ask yourself “Why do I agree?” or “Why do I disagree?” The first sentence you say to yourself in response to that question is your rough thesis statement. Jot that down under the first phrase. So, my response to our example would look like this:

* I agree * While the new version might have its merits, the original often has merits of its own.

Again, this is very rough at this stage, but on the SAT you’re trying to prewrite fast, so don’t worry too much about that. On to the body paragraphs!

On a 25-minute essay, you probably won’t have enough time for a full five-paragraph structure with three sub-examples for each point. Two body paragraphs and two examples of each will suffice. You never want to rely on just a single example, though, or you’ll likely lose points for not supporting your statements enough. Write out a template for the body of your essay that looks like this:

I. Main point 1 A. Example 1 B. Example 2 II. Main point 2 A. Example 1 B. Exampple 2

Remember, it’s an outline, so no full sentences. Write only as much as you need to remind yourself of your points. So for our example, my outline would look like this:

I. The “Tangible” aspects A. A book never runs out of battery B. Can read it in the sun, by the pool or in the bathtub – places you wouldn’t want to take a piece of electronics II. The “non-tangible” aspects A. The smell of a new book, tactile sense of turning pages, experience of closing it when you finish B. Ability to get lost in a book, to lose sense of place and become the story

At this point I can see a slight revision I’d make to my original thesis statement, which is the idea that an e-book can never mimic the tactile experience of reading (smelling the book, turning pages, etc.) I’ll quickly adjust my thesis to say:

While the new version might have its merits, the original offers a tactile experience that the new can’t hope to achieve – an experience that can’t be mimicked by technology.

Perfect. All told, your prewriting should have taken you 3 to 5 minutes, most of which was thinking. Now, on to the paper itself!

Writing Your Essay

Okay, here’s my biggest timed-essay secret: don’t start with the introduction. Start by skipping five or six lines down the page, leaving space for an introduction that will be inserted later. Start with your first body paragraph. Work from your outline, converting your points into full sentences and connecting them with transitions, and you should be at a good start. Once both body paragraphs are written, continue on and write your conclusion. Then, go back and write your introduction in the space you left at the beginning. That way, you’ll know what you’re introducing since it’s already written.

I generally recommend about 15 minutes of writing time for the body paragraphs, followed by 5 minutes for the intro and conclusion. Depending on how quickly you got your prewriting done, that leaves you with one or two minutes to look it over, fixing any spelling mistakes or sloppy handwriting. Don’t try to change too much, though – when you’re writing everything out longhand, changes require erasing. We do so much writing on computers these days that sometimes we forget how long it takes to erase a whole sentence and rewrite it. A better tactic is to think through each sentence in your head before you write it down, making sure you have it phrased the way you want it before you put pencil to paper. But don’t spend too long – try it a few times and you’ll find that writing four full paragraphs longhand actually takes about 25 minutes to do – on a good day. You should expect to be writing pretty much continuously for the entire 25 minutes.

Keeping Track of Time, Staying Comfortable, and More Advice

Speaking of which, when you practice your timed essays, pay attention to how your hand feels while you’re writing. The first few times you’ll likely be sore; your hand might even cramp up from writing so hard. It’s tiring to write for that long, so make sure you’re helping yourself. Write lightly on the paper – it’s easy to start pressing down super hard when you’re nervous and panicking. Writing lightly will not only help stave off the hand cramps, it’ll also make erasing much easier when you need to do it. Sit back in your chair while you write – you don’t need to be three inches from your paper to see the words you’re putting down, and hunching over will just make you press harder. Bring your attention to your breathing – are you holding your breath? Why? Try breathing deeply and slowly while you write – it’ll calm your brain and help you think.

Finally, a word about the writing itself – don’t forget you’re on a clock here. Often, you begin to notice as you write that your opinion about the topic is evolving, changing, developing nuances and side areas you want to explore. I know this sounds weird, but you’ve got to try to rein that in – those are all fine things to be thinking about ordinarily, and in an at-home essay I’d say go for it, but you don’t have time to change what you’re writing about in this situation. Sometimes, you’ll even get halfway through a timed essay and realize that you actually don’t agree like you thought you did. Save that thought for later. You’ve got the outline of an organized essay, and that’s what you should be writing. It doesn’t matter at this point if you actually still agree with what you’re saying, all that matters is that you state a clear opinion and communicate it well. After all, the test grader doesn’t even know you – how’s she to know that you don’t really think this anymore? Stay confident and get your original idea out on paper.

For example, the outline I gave above is a perfectly accurate depiction of my opinion on the topic – as it relates to books. However, if we were to start talking about, say, writing essays…I’d probably say that no, I don’t think we should hold on to writing essays out by hand when there are computers available. After all, I’m writing this article on a computer. I’ve copied and pasted multiple paragraphs of information back and forth around this lesson as I was looking for appropriate ways to introduce concepts, and that would have taken forever if I had been writing by hand. But if that thought had occurred to me midway through writing my timed essay about books, I would have acknowledged it for the briefest of moments and then disregarded it. My essay is about books. I’ll just stick to that so I can keep it clean and organized.

Don’t worry about the test graders thinking “But what about X?” – they know you only had 25 minutes and can’t possibly fit every aspect of the argument into that amount of time – or space, for that matter. The scoring rubric focuses on what is present, not what is omitted. As long as you have a clear point of view and are communicating it well, you’ll fulfill their criteria. Remember, this essay’s not in the critical reading section, it’s in the writing section. They’re not in the business of judging the merits of your opinion, just how clearly you’ve communicated it and how well you’ve supported it.

Your timed essays will probably turn out very different than the essays you write at home for class. They might seem stiff, straightforward or brusque; with a limited amount of time you can’t create the subtle, nuanced arguments that your English teachers are probably looking for. But what you can do is create a well-organized, concise presentation of a relatively straightforward point of view, supported by concrete examples that all point toward the same central concept. The SAT essay responds well to a formulaic approach, so while it may take some practice, you will eventually be able to handle a 25-minute essay prompt with confidence.

- How can we change the underlined section to best set up the information that follows?

- How can we best change the underlined section, or is it good as it is?

- The result was an explosion of mural painting that spread throughout California and the southwestern United States in the 1970s. It was the Chicano mural movement

- What are some strategies I can use to make my writing more persuasive?

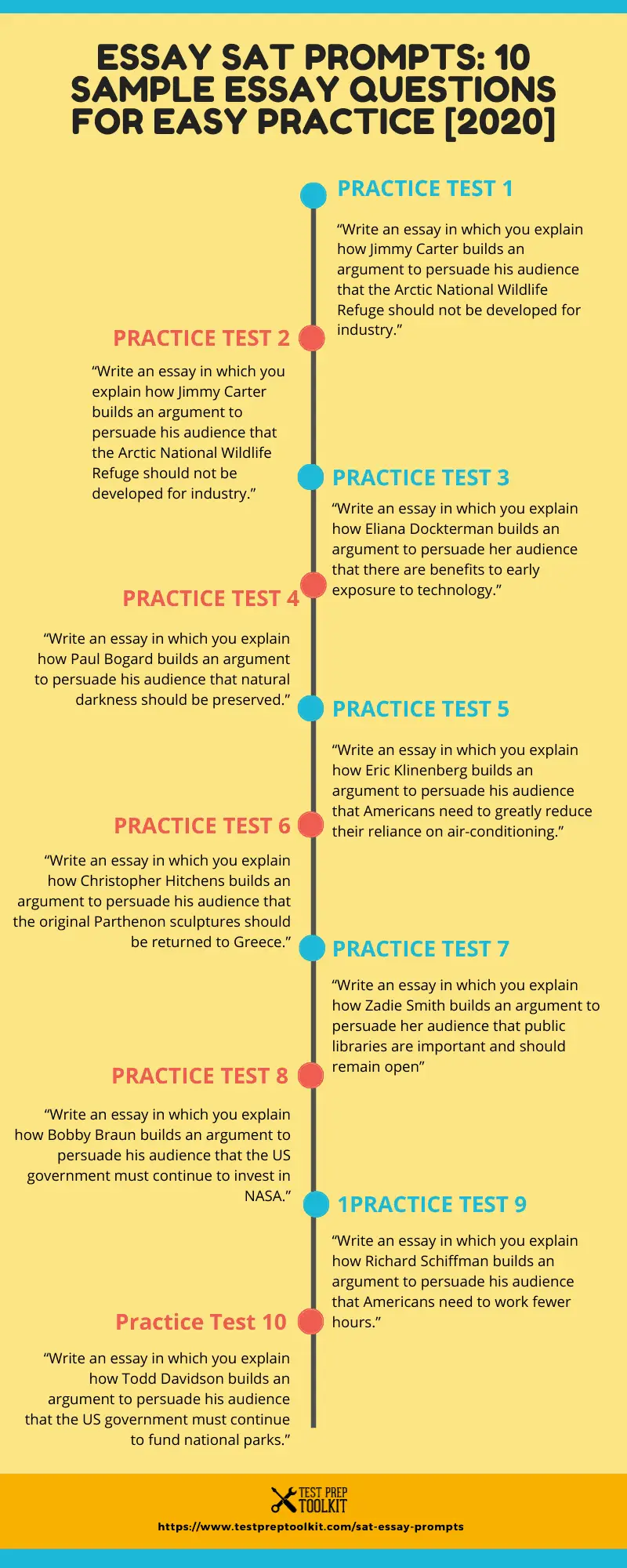

SAT Essay Prompts (10 Sample Questions)

What does it take to get a high SAT Essay score, if not perfect it? Practice, practice and more practice! Know the tricks and techniques of writing the perfect SAT Essay, so that you can score perfect as well. That’s not a far off idea, because there actually is a particular “formula” for perfecting the SAT Essay test. Consider that every prompt has a format, and what test-takers are required to do remain the same- even if the passage varies from test to test.

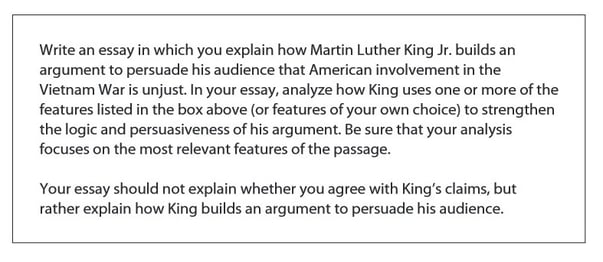

The SAT Essay test will ask you to read an argument that is intended to persuade a general audience. You’ll need to discuss how proficient the author is in arguing their point. Analyze the argument of the author and create an integrated and structured essay that explains your analysis.

On this page, we will feature 10 real SAT Essay prompts that have been recently released online by the College Board. You can utilize these Essay SAT prompts as 10 sample SAT Essay questions for easy practice. This set of SAT Essay prompts is the most comprehensive that you will find online today.

The predictability of the SAT Essay test necessitates students to perform an organized analytical method of writing instead of thinking up random ideas on their own. Consider that what you will see before and after the passage remains consistent. It is recommended that you initially read and apply the techniques suggested in writing the perfect SAT Essay (🡨link to SAT Essay —- SAT Essay Overview: How to Get a Perfect Score) before proceeding on using the following essay prompts for practice.

Check our SAT Reading Practice Tests

10 Official SAT Essay Prompts For Practice

Practice Test 1

“Write an essay in which you explain how Jimmy Carter builds an argument to persuade his audience that the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge should not be developed for industry.”

Practice Test 2

“Write an essay in which you explain how Martin Luther King Jr. builds an argument to persuade his audience that American involvement in the Vietnam War is unjust.”

Practice Test 3

“Write an essay in which you explain how Eliana Dockterman builds an argument to persuade her audience that there are benefits to early exposure to technology.”

Practice Test 4

“Write an essay in which you explain how Paul Bogard builds an argument to persuade his audience that natural darkness should be preserved.”

Practice Test 5

“Write an essay in which you explain how Eric Klinenberg builds an argument to persuade his audience that Americans need to greatly reduce their reliance on air-conditioning.”

Practice Test 6

“Write an essay in which you explain how Christopher Hitchens builds an argument to persuade his audience that the original Parthenon sculptures should be returned to Greece.”

Practice Test 7

“Write an essay in which you explain how Zadie Smith builds an argument to persuade her audience that public libraries are important and should remain open”

Practice Test 8

“Write an essay in which you explain how Bobby Braun builds an argument to persuade his audience that the US government must continue to invest in NASA.”

Practice Test 9

“Write an essay in which you explain how Richard Schiffman builds an argument to persuade his audience that Americans need to work fewer hours.”

Practice Test 10

“Write an essay in which you explain how Todd Davidson builds an argument to persuade his audience that the US government must continue to fund national parks.”

Visit our SAT Writing Practice Tests

What Is An Example Of A SAT Essay That Obtained A Perfect Score?

Here is an example of Practice Test 4 above and how a perfect SAT Essay in response to it looks like. This has been published in the College Board website.

Answer Essay with Perfect Score:

In response to our world’s growing reliance on artificial light, writer Paul Bogard argues that natural darkness should be preserved in his article “Let There be dark”. He effectively builds his argument by using a personal anecdote, allusions to art and history, and rhetorical questions.

Bogard starts his article off by recounting a personal story – a summer spent on a Minnesota lake where there was “woods so dark that [his] hands disappeared before [his] eyes.” In telling this brief anecdote, Bogard challenges the audience to remember a time where they could fully amass themselves in natural darkness void of artificial light. By drawing in his readers with a personal encounter about night darkness, the author means to establish the potential for beauty, glamour, and awe-inspiring mystery that genuine darkness can possess. He builds his argument for the preservation of natural darkness by reminiscing for his readers a first-hand encounter that proves the “irreplaceable value of darkness.” This anecdote provides a baseline of sorts for readers to find credence with the author’s claims.

Bogard’s argument is also furthered by his use of allusion to art – Van Gogh’s “Starry Night” – and modern history – Paris’ reputation as “The City of Light”. By first referencing “Starry Night”, a painting generally considered to be undoubtedly beautiful, Bogard establishes that the natural magnificence of stars in a dark sky is definite. A world absent of excess artificial light could potentially hold the key to a grand, glorious night sky like Van Gogh’s according to the writer. This urges the readers to weigh the disadvantages of our world consumed by unnatural, vapid lighting. Furthermore, Bogard’s alludes to Paris as “the famed ‘city of light’”. He then goes on to state how Paris has taken steps to exercise more sustainable lighting practices. By doing this, Bogard creates a dichotomy between Paris’ traditionally alluded-to name and the reality of what Paris is becoming – no longer “the city of light”, but moreso “the city of light…before 2 AM”. This furthers his line of argumentation because it shows how steps can be and are being taken to preserve natural darkness. It shows that even a city that is literally famous for being constantly lit can practically address light pollution in a manner that preserves the beauty of both the city itself and the universe as a whole

Finally, Bogard makes subtle yet efficient use of rhetorical questioning to persuade his audience that natural darkness preservation is essential. He asks the readers to consider “what the vision of the night sky might inspire in each of us, in our children or grandchildren?” in a way that brutally plays to each of our emotions. By asking this question, Bogard draws out heartfelt ponderance from his readers about the affecting power of an untainted night sky. This rhetorical question tugs at the readers’ heartstrings; while the reader may have seen an unobscured night skyline before, the possibility that their child or grandchild will never get the chance sways them to see as Bogard sees. This strategy is definitively an appeal to pathos, forcing the audience to directly face an emotionally-charged inquiry that will surely spur some kind of response. By doing this, Bogard develops his argument, adding gutthral power to the idea that the issue of maintaining natural darkness is relevant and multifaceted.

Writing as a reaction to his disappointment that artificial light has largely permeated the prescence of natural darkness, Paul Bogard argues that we must preserve true, unaffected darkness. He builds this claim by making use of a personal anecdote, allusions, and rhetorical questioning.

Related Topic: SAT Requirements

This response scored a 4/4/4.

Reading—4: This response demonstrates thorough comprehension of the source text through skillful use of paraphrases and direct quotations. The writer briefly summarizes the central idea of Bogard’s piece ( natural darkness should be preserved ; we must preserve true, unaffected darkness ), and presents many details from the text, such as referring to the personal anecdote that opens the passage and citing Bogard’s use of Paris’ reputation as “The City of Light.” There are few long direct quotations from the source text; instead, the response succinctly and accurately captures the entirety of Bogard’s argument in the writer’s own words, and the writer is able to articulate how details in the source text interrelate with Bogard’s central claim. The response is also free of errors of fact or interpretation. Overall, the response demonstrates advanced reading comprehension.

Analysis—4: This response offers an insightful analysis of the source text and demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of the analytical task. In analyzing Bogard’s use of personal anecdote, allusions to art and history, and rhetorical questions , the writer is able to explain carefully and thoroughly how Bogard builds his argument over the course of the passage. For example, the writer offers a possible reason for why Bogard chose to open his argument with a personal anecdote, and is also able to describe the overall effect of that choice on his audience ( In telling this brief anecdote, Bogard challenges the audience to remember a time where they could fully amass themselves in natural darkness void of artificial light. By drawing in his readers with a personal encounter…the author means to establish the potential for beauty, glamour, and awe-inspiring mystery that genuine darkness can possess…. This anecdote provides a baseline of sorts for readers to find credence with the author’s claims ). The cogent chain of reasoning indicates an understanding of the overall effect of Bogard’s personal narrative both in terms of its function in the passage and how it affects his audience. This type of insightful analysis is evident throughout the response and indicates advanced analytical skill.

Writing—4: The response is cohesive and demonstrates highly effective use and command of language. The response contains a precise central claim ( He effectively builds his argument by using personal anecdote, allusions to art and history, and rhetorical questions ), and the body paragraphs are tightly focused on those three elements of Bogard’s text. There is a clear, deliberate progression of ideas within paragraphs and throughout the response. The writer’s brief introduction and conclusion are skillfully written and encapsulate the main ideas of Bogard’s piece as well as the overall structure of the writer’s analysis. There is a consistent use of both precise word choice and well-chosen turns of phrase ( the natural magnificence of stars in a dark sky is definite , our world consumed by unnatural, vapid lighting , the affecting power of an untainted night sky ). Moreover, the response features a wide variety in sentence structure and many examples of sophisticated sentences ( By doing this, Bogard creates a dichotomy between Paris’ traditionally alluded-to name and the reality of what Paris is becoming – no longer “the city of light”, but moreso “the city of light…before 2AM” ). The response demonstrates a strong command of the conventions of written English. Overall, the response exemplifies advanced writing proficiency.

Related Topics:

- Practice Tests for SAT Reading

- SAT Writing And Language Practice Tests

- SAT Languages Test

- SAT Essay Test SAT Writing Practice Tests

- SAT Science Test, Topics & Subjects Content

- SAT Registration

- SAT Test Dates

- SAT vs ACT, Which One Should You Take?

- Why Take the SAT?

SAT® Writing Practice Tests and Questions

Our SAT® Writing Practice Tests and Questions are written by subject matter experts to meet or exceed exam-level difficulty, because we believe that if practice feels like the actual exam, the real thing will feel like practice. Not getting something? We’ve got you covered with in-depth answer explanations and vivid illustrations that make hard stuff easy to understand.

* Digital SAT Writing Practice Bank available July 2023!

*The Reading and Writing sections of the SAT will be combined in the US starting March 2024

Benefits of Practicing SAT Writing Exam-Like Questions

Unlimited exam-level practice, customized to your needs, understand the why, sat writing sample questions.

Select a Question sample.

A certain number of mandatory volunteer service hours are required for many high school students to graduate. Such service, be it serving meals at a soup kitchen, when they create crafts with kids at the library, or helping people at a senior citizens’ home, has received a lot of attention and backlash.

Given its definition, volunteer work should be something that people want to do. “To call mandatory community service ‘volunteering’ is a problem because then we begin to confuse the distinction between an activity that is freely chosen and something that is obligatory,” says Linda Graff, president of an international consulting firm. Ruth MacKenzie, former president and CEO of Volunteer Canada, voices similar thoughts: “The mandated nature means this is not really volunteering, and the fear…is that forcing kids to volunteer…might turn them off the concept for the rest of their lives.”

But what about the positives? Research reveals no negative impacts from education administrators’ removing a high schoolers option about whether to volunteer. Supporters of required volunteering who are in favor of it also point to significant research that proves the younger individuals become involved in volunteering, the more likely they are to be lifelong volunteers who care about others, make positive contributions to the community, and have less time for themselves.

Is forcing students to volunteer different from forcing them to learn proper language or science skills? All these skills help define students’ knowledge base and even effect the attitudes that students will carry with them throughout their lives. However, high school does more than prepare students for further education, it also helps with social interaction, equips them for problem-solving in all aspects of life, and often directs students down a lifelong path—career or otherwise.

One theory suggests a correlation between service learning and higher academic achievement. Also, many believe that students who volunteer acquire more transferable skills in a practical setting, making them more employable than the skills of those who lack real-world experience. For example, volunteering allows students to interact with people from other walks of life and to try a variety of tasks to see what they most enjoy. Employers know that the more someone volunteers, the more likely it is that the individual will be a hard worker. Another benefit is that many scholarships have volunteer-hour requirements or, at the very least, are awarded to students who are active participants in their community. Therefore, students who volunteer are much more likely to meet both their educational and career goals.

1. This work, “Forcing Students to Volunteer,” is a derivative of “Is Forcing Students to Volunteer A Good Idea?” in the July 3, 2015, blog on the Charity Republic website. Published with permission. “Forcing Students to Volunteer” is licensed by UWorld.

Also, many believe that students who volunteer acquire more transferable skills in a practical setting, making them more employable than the skills of those who lack real-world experience.

- than students

- than the skills gained by students

- with volunteers

- Explanation

Also, many believe that students who volunteer acquire more transferable skills in a practical setting, making them more employable than students who lack real-world experience.

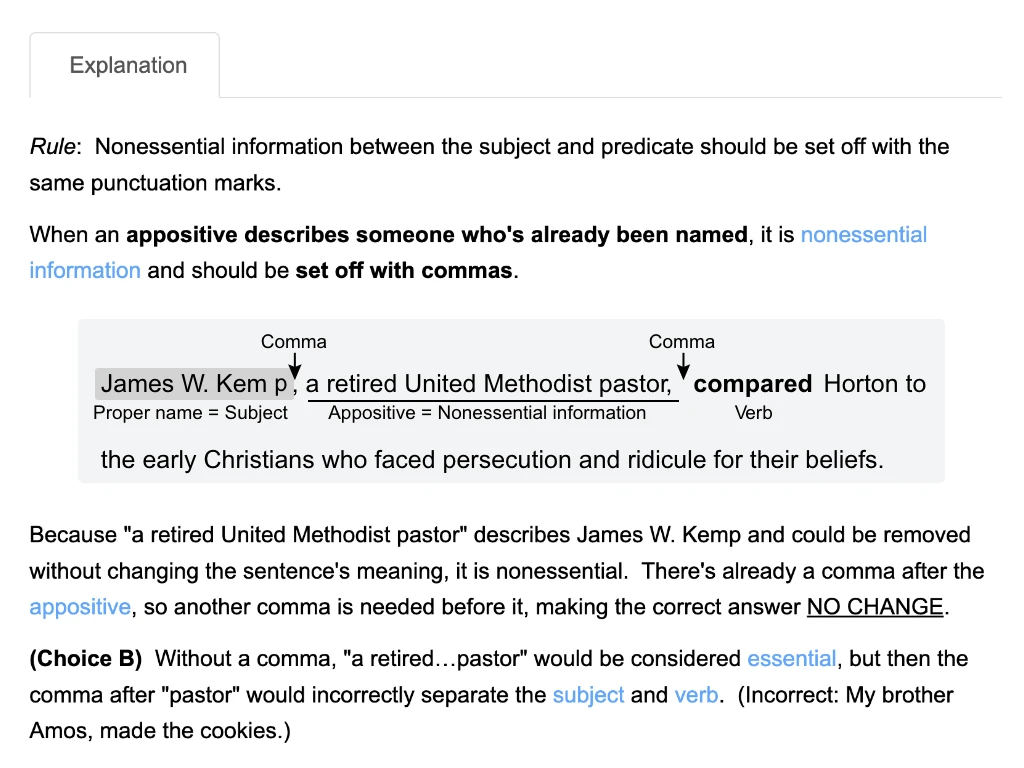

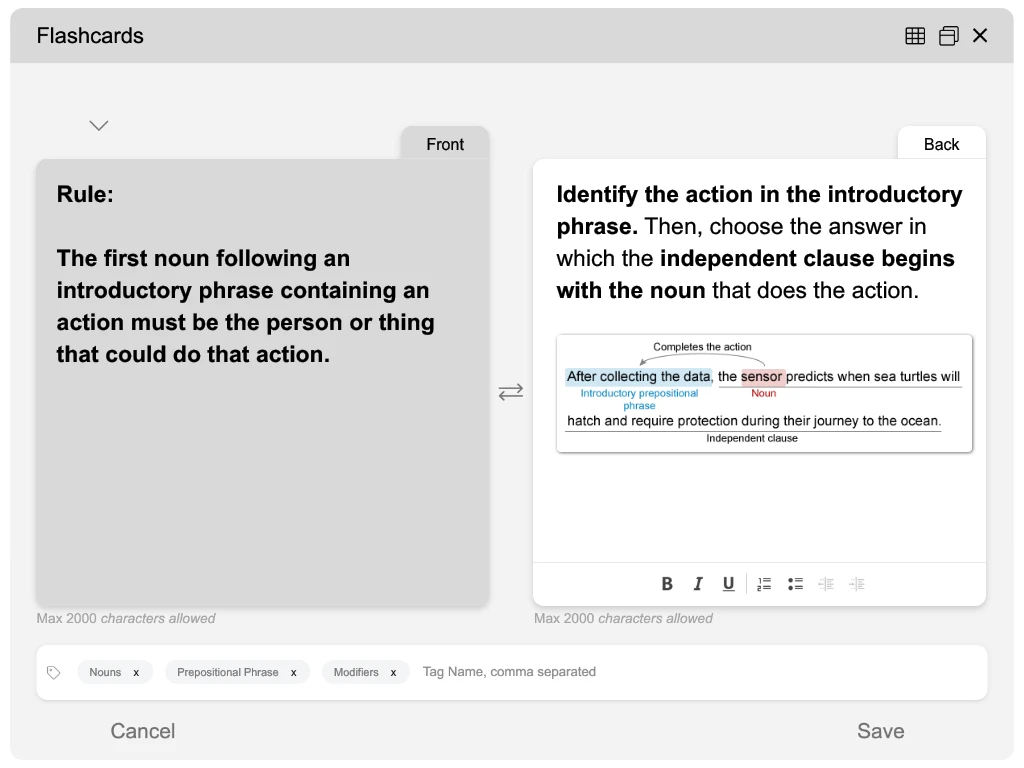

Rule : Comparisons should be made between similar things: objects with objects, people with people.

For a sentence to make sense, comparisons should be made between like things . For example: Mechanics who graduate from trade school typically make more money than mechanics who don’t. The parallel structure of the repeated phrase “mechanics who” indicates that similar people are being compared.

Here, “students” parallels a phrase from earlier in the sentence that indicates the students who volunteer are being compared to students “who lack real world experience.” Because “than” is a word that indicates a comparison, the correct answer is than students .

(Choices A and C) Both of these answers incorrectly compare “students” (people) with “skills” (things). (Incorrect: The students know more than their skills. Correct: Our students have more skills than your students.)

(Choice D) This answer doesn’t contain a word that indicates a comparison. Instead, “with” indicates that when students are accompanied by volunteers who don’t have work experience, they are more likely to get a job, which isn’t logical.

Things to remember: Compare people to other people and things to other things. Also, look for an answer choice that provides parallel structure to the other part of the comparison. (Incorrect: He is a bigger rap music fan than country music. Correct: He is a bigger rap music fan than I am.)

A vampire is a thirsty thing, spreading metaphors like antigens, through its victim’s blood. It is a rare situation that is not metaphorically defamiliarized by the introduction of a vampiric motif, whether it be migration and industrial change in Dracula ; adolescent coming-of-age in Twilight ; or racism in True Blood . Beyond undead life and the knack of becoming a bat, the vampire’s true power is its ability to induce intense paranoia about the nature of social relations to ask, “Who are the real bloodsuckers?”

This is certainly the case with the first fully realized vampire story in English, John Polidori’s 1819 tale, “The Vampyre.” It is Polidori’s text that establishes the vampire as we know it. He reimagined the feral, mud-caked creatures of southeastern European legend as the elegantly magnetic denizens swarming all around the cosmopolitan assemblies and polite drawing rooms.

“The Vampyre” is a product of 1816, when Lord Byron left England in the wake of a disintegrating marriage and rumors of madness, to travel to the banks of Lake Geneva and there loiter with Percy and Mary Shelley: then still Mary Godwin. Polidori served as Byron’s travelling physician. He also played an active role in the summer’s tensions and rivalries. He also participated in the famous night of ghost stories that produced Mary Shelley’s “hideous progeny,” Frankenstein .

Like Frankenstein , “The Vampyre” draws extensively on the mood at Byron’s Villa Diodati. But whereas Mary Shelley incorporated the orchestral thunderstorms that illuminated the lake and the sublime mountain scenery that served as a backdrop to Victor Frankenstein’s struggles, Polidori’s text is woven from the invisible dynamics of the Byron-Shelley circle, and especially the humiliations he suffered at Byron’s hand.

The most overt example of Byron as the devourer of souls was a novel Polidori read over the course of the summer— Glenarvon by Lady Caroline Lamb. Byron and Lamb had enjoyed a brief affair until he, somewhat rattled, had called it off. That Polidori took inspiration from Lamb is revealed in the name he gives his villain—Lord Ruthven, one of Glenarvon’s various ancestral titles. Polidori’s Ruthven also inhabits Glenarvon ‘s aristocratic milieu as a member of the bon ton .

Rather than providing validation for his creative outlet, Polidori’s humiliation was only compounded by the publication of “The Vampyre.” Although the text was similarly prompted by the ghost story competition that inspired Mary Shelley so ably, but Polidori only completed his story for the pleasure of a friend outside of the Byron-Shelley circle. The manuscript lay forgotten for three years until finally coming into the hands of the disreputable journalist Henry Colburn, who reported it in his New Monthly Magazine under the title “The Vampyre: A Tale by Lord Byron.”

1. This work, “The Vampyre,” is a derivative of “The Poet, the Physician, and the Birth of the Modern Vampire,” by Andrew McConnell Stott, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 by UWorld.

It is a rare situation that is not metaphorically defamiliarized by the introduction of a vampiric motif, whether it be migration and industrial change in Dracula ; adolescent coming-of-age in Twilight ; or racism in True Blood .

- Dracula , adolescent coming-of-age in Twilight ,

- Dracula ; adolescent coming-of-age in Twilight ,

- Dracula , adolescent coming-of-age in Twilight ;

Rule : Commas separate phrases within a list.

Look for the pattern of listed items to help you determine where one ends and the next begins.

This list contains a noun followed by a prepositional phrase . Because “adolescent” describes “ Twilight ” instead of “ Dracula, ” a comma is needed to show where the first listed item ends and the next begins. Likewise, the conjunction “or” indicates where the second listed item ends, so there needs to be a comma after Twilight . Therefore, Dracula , adolescent coming-of-age in Twilight , is the correct answer.

(Choices A, C, and D) Semicolons separate items in a list when the listed items already contain commas. (Ex. Ed bought apples, oranges, and grapes at Kroger; meat, dairy, and fish at Albertsons; and toothpaste, soap, and razors at Walgreens.) However, the items in this list (ex. “migration and industrial change”) don’t already contain commas. On the SAT, commas, not semicolons, are usually used to separate items in lists.

Things to remember: Use commas to separate items in a list when those items contain no other punctuation.

Two dancers in wheelchairs faced each other, raising their arms in intricate patterns. Others incorporated crutches or a chair into their actions. The dancers, bailing from around the world, came together for a week in June for UCLA’s Dancing Disability Lab, which was hosted by the world arts and cultures/dance group and lasted for seven days. This lab is a cross-disciplinary initiative designed to reframe again cultural understanding and practices around the concept of disability through classes and community engagement. Each lab builds and strengthens networks of university faculty, staff, and students so that community leaders can transform the discourse and awareness surrounding disability.

Mel Chua, a biomedical engineering student at Georgia Tech, said she was hesitant to apply for the program because she assumed that her previous dance training wasn’t advanced enough. But Chua came to realize that the reason she felt negligibly unqualified was that, as a deaf person, she had never had access to dance training like what she had experienced at the Disability Lab. A first for Chua and many other dancers was getting to dance with a group of exclusively disabled dance artists. Instead of being the only disabled person in the class, feeling graded by disability, or having to translate choreography designed for nondisabled dancers, the participants were united in how they each expanded dancing conventions. Being in a dance workshop where everyone has a disability was empowering and eye-opening for all the dancers.

That said, Chua emphasized that she is not looking to expose others or receive sympathy for the challenges she faces. Although the idea of inclusion often focuses on bringing disabled and nondisabled people together, Chua believes it’s important for disabled people to have spaces that are just their own. The lab gives disabled artists a chance to be heard and seen differently than some might be accustomed to—a necessary step in cinching that nondisabled persons will be allies and provide ongoing support for equal access and inclusion.

1. This work, “Program for Disabled Dancers,” is a derivative of “Disabled dancers learn to redefine the aesthetics of movement at UCLA” by Robin Migdol in UCLA’s Newsroom on September 5, 2019, and used with permission. “Program for Disabled Dancers” is licensed by UWorld.

Although the idea of inclusion often focuses on bringing disabled and nondisabled people together, Chua believes it’s important for disabled people to have spaces that are just their own.

Determine the right word or phrase by seeing which one makes sense in context .

In general, “that” introduces a clause that describes the noun immediately before it. (Ex. My parents have a lake house that we enjoy on the weekends.) Because “are just their own” describes “spaces,” the correct answer is “that” or NO CHANGE .

(Choice B) “And which” is used when one descriptive clause follows another one. (Ex. Tomorrow is the day of my test, which I’ve been dreading and which I must pass to graduate.) Without another descriptive clause, there’s nothing that the “and which” can follow.

(Choices C and D) Both “to which” and “of which” are prepositional phrases , which would make “which” the object of a preposition . Because prepositional objects can’t be the subject of a clause, the dependent clause would be left without a subject.

Things to remember: “That” introduces an essential clause describing the noun immediately before it.

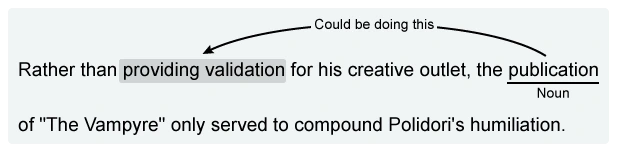

Rather than providing validation for his creative outlet, Polidori’s humiliation was only compounded by the publication of “The Vampyre.”

- the publication of “The Vampyre” only served to compound Polidori’s humiliation.

- the humiliation of Polidori was only compounded when “The Vampyre” was published.

- the compounding of Polidori’s humiliation happened with the publication of “The Vampyre.”

Rule : The first noun following an introductory phrase should be the person or thing that phrase describes.

Look at the first noun of each answer choice to see which one could be described by the introductory information .

Based on the introductory phrase , “Rather than providing a creative outlet,” ask yourself, which answer choice begins with a word that could provide a creative outlet for Polidori? The answer is the publication of his story. The correct answer, then is the choice in which “publication” is the first noun : the publication of “The Vampyre” only served to compound Polidori’s humiliation .

(Choices A, C, and D) None of these answers begin with a noun that could provide a creative outlet.

- Choices A and C: The first noun in both these answers is “humiliation” (extreme embarrassment), which wouldn’t provide a creative outlet. “Polidori” is mentioned in Choice A to describe whose humiliation is referenced.

- Choice D: “Compounding” (making something worse) functions as a gerund and the first noun after the introductory phrase. When something is made worse, it doesn’t make sense that it also provides a creative outlet, which is generally positive.

Things to remember: To communicate clearly, the first noun after an introductory phrase should be what is described by that phrase.

YouTube artist Jon Cozart asks, “Do you ever wonder why Disney tales all end in lies?” in his 2013 musical parody. Cozart responds to the question with a catchy and humorous, but slightly shocking, series of answers about what he thinks could have happened after Ariel, Jasmine, Belle, and Pocahontas experienced their “happily ever afters.” The medley was published on a musical video-sharing site, where it has been watched over 61 million times since its publication. The video— titled “After Ever After,” reimagines these four self-aware Disney princesses in our real world and speculates about how they would handle this harsh and difficult reality.

This formulaic ending for protagonists of the fairy tale has been persuasive to the genre. The development of postmodernism and feminism in recent decades has resulted in an audience that is less willing to accept that standard and unsatisfying conclusion. Due to this dissatisfaction, revisionist versions of classic stories have become popular. A combination of fairy tale scholarship, new media and amateur media studies, folklore, and cultural studies adds to the analysis of this form of fairy tale revision, which aligns to the more realistic world view reflected in Cozart’s video.

While there has recently been a surge in fairy tale retellings through television shows, movies, and books to meet this contemporary demand, the feminist views emerging on the videos of YouTube.com allow an individual to create and broadcast material to a worldwide audience from the comfort of his or her own home. Being comfortable is important to making popular movies.

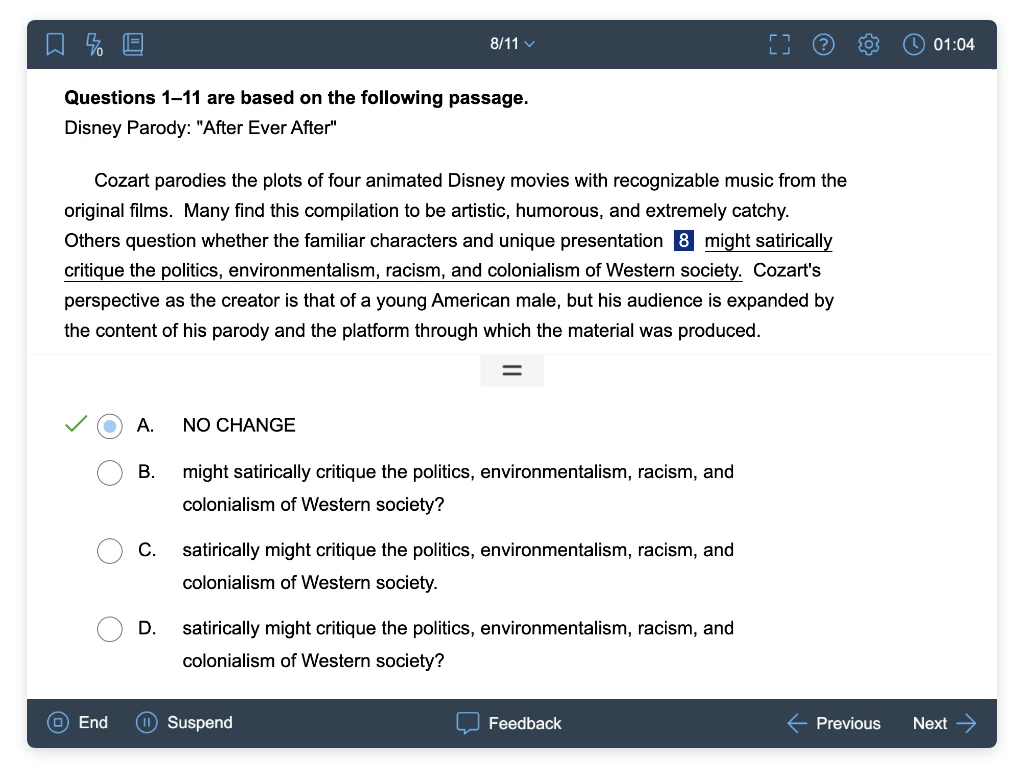

Cozart parodies the plots of four animated Disney movies with recognizable music from the original films. Many find this compilation to be artistic, humorous, and extremely catchy. Others question whether the familiar characters and unique presentation might satirically critique the politics, environmentalism, racism, and colonialism of Western society. Cozart’s perspective as the creator is that of a young American male, but his audience is expanded by the content of his parody and the platform through which the material was produced.

This case study, of Cozart’s first “After Ever After” video examines the use of Disney heroines as spokespersons of Cozart’s digital parody, which can be considered quite funny to some people but very offensive to others. Cozart is one of many who comment on society by making use of “the end” as a new beginning. In doing so, he retains some aspects of “classic Disney” while subverting much of the sense of wonder that gives the original genre its name.

1. This work is a derivative of "’After Ever After’: Social Commentary through a Satiric Disney Parody for the Digital Age" by Kylie Schroeder published in Humanities 2016, 5(3), 63; doi:10.3390/h5030063, an Open Access document. Licensed under CC BY 4.0 by UWorld.

This case study, of Cozart’s first “After Ever After” video examines the use of Disney heroines as spokespersons of Cozart’s digital parody, which can be considered quite funny to some people but very offensive to others. Cozart is one of many who comment on society by making use of “the end” as a new beginning. In doing so, he retains some aspects of “classic Disney” while subverting much of the sense of wonder that gives the original genre its name.

- which question how these four young girls contributed to the lies.

- which functions as social, historical, political, and environmental commentary.

- although his motivations for changing these stories is not really clear.

P6: This case study, of Cozart’s first “After Ever After” video examines the use of Disney heroines as spokespersons of Cozart’s digital parody, which functions as social, historical, political, and environmental commentary. Cozart is one of many who comment on society by making use of “the end” as a new beginning. In doing so, he retains some aspects of “classic Disney” while subverting much of the sense of wonder that gives the original genre its name.

Reread the paragraph and summarize what is being discussed: this will be the main point of the paragraph. Select the answer choice that has a similar idea .

This paragraph discusses how Cozart’s Disney heroines are used as spokespersons to comment on society and to subvert (ruin) the sense of wonder that Disney movies often portray. The main point of the paragraph, then, is that Cozart’s video is commenting on various aspects of society’s culture. Therefore, the correct answer is the one that says that Cozart’s digital parody functions as social, historical, political, and environmental commentary .

(Choice A) Although people’s reactions to parodies do vary, that difference doesn’t reflect the main point of the rest of the paragraph.

(Choice B) P1, not P6, focuses on how fairy tales end in lies, but it does not discuss how these four young women might have “contributed to the lies.”

(Choice D) The paragraph doesn’t reflect on Cozart’s reasons for making the videos, so anything about his motivation for making them not being clear isn’t relevant to what’s being discussed.

Things to remember: Determine the main point of the paragraph you’re trying to support and choose the answer with related information.

Enjoying our questions? Receive them every week, absolutely free!

Signup to receive free UWorld questions every week

Get 400 on the SAT Writing Section with UWorld

Study content crafted by subject matter experts, assess yourself with exam-level practice, measure your performance, target your weaknesses with focused study, and repeat.

“I increased my SAT score in three weeks from 1000 to 1320.”

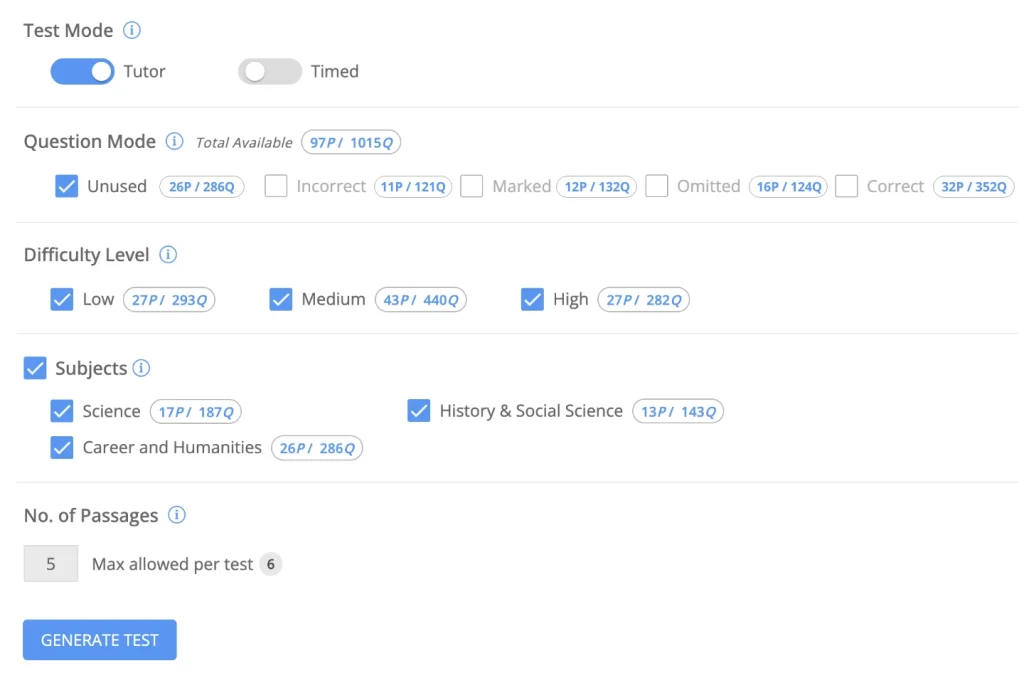

Create Unlimited Practice Tests with Exam-Level Questions

- Generate unlimited practice tests from hundreds of exam-level questions.

- Target your weaknesses by customizing a test based on topic, custom tag, or even just questions you’ve previously gotten wrong.

Understand Why an Answer is Right or Wrong

- It's not enough to know the right answer. You must understand why it's right or wrong.

- That's why we provide in-depth answer explanations complemented by professionally produced images for every answer choice.

Track Your Progress With Advanced Analytics

- Instead of reviewing what you already know, channel your study sessions towards personal growth and progress.

- Measure your progress with score predictors, identify your weaknesses in real time, compare your results to your peers, and receive feedback summaries for each test.

Features: My Notebook & Flashcards

- Click, highlight, and select to create notes or flashcards. It’s that easy to transfer QBank visual and written content to your digital My Notebook and Flashcards.

- Tailor study aids to your learning style and keep them all organized by topic or custom tag.

- The best part? These learning aids are always in arms reach with our mobile app.

We make the real thing feel like practice

We believe that if practice feels like the actual exam, then the actual exam will feel like practice. UWorld simulates the actual SAT, so you’ll have all the confidence you need come exam day.

Practice SAT Writing Sample Questions Anywhere at Any Time

Great SAT Writing Scores make Students Happy

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

We use cookies to learn how you use our website and to ensure that you have the best possible experience. By continuing to use our website, you are accepting the use of cookies. Learn More

SAT Writing and Language: Practice tests and explanations

The SAT writing and language test consists of 44 multiple-choice questions that you'll have 35 minutes to complete. The questions are designed to test your knowledge of grammatical and stylistic topics.

The SAT Writing and Language questions ask about a variety of grammatical and stylistic topics. If you like to read and/or write, the SAT may frustrate you a bit because it may seem to boil writing down to a couple of dull rules.

- 30 SAT Grammar Practice Tests

SAT Writing and Language Practice Tests

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 1

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 2

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 3

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 4

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 5

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 6

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 7

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 8

- New SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 9

- New SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 10

- New SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 11

- New SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 12

- New SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 13

- New SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 14

- New SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 15

- New SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 16

- New SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 17

- New SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 18

- New SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 19

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: A Sweet Discovery

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: René Descartes: The Father of Modern Philosophy

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: The Novel: Introspection to Escapism

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: Interning: A Bridge Between Classes and Careers

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: In Defense of Don Quixote

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: Women's Ingenuity

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: Working from Home: Too Good to Be True?

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: Is Gluten-Free the Way to Be?

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: Antarctic Treaty System in Need of Reform

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: Finding Pluto

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: Public Relations: Build Your Brand While Building for Others

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: Film, Culture, and Globalization

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: Vitamin C—Essential Nutrient or Wonder Drug?

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: The Familiar Myth

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: America's Love for Streetcars

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: Educating Early

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: The Age of the Librarian

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: Unforeseen Consequences: The Dark Side of the Industrial Revolution

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: Remembering Freud

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: Success in Montreal

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: Sorting Recyclables for Best Re-Use

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: Interpreter at America's Immigrant Gateway

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: Software Sales: A Gratifying Career

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: The Art of Collecting

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: The UN: Promoting World Peace

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: DNA Analysis in a Day

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: Will You Succeed with Your Start-Up?

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: Edgard Varèse's Influence

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: From Here to the Stars

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: The UK and the Euro

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: Coffee: The Buzz on Beans

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: Predicting Nature's Light Show

- New SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 20

- New SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 21

- New SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 22

- New SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 23

- New SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 24

- New SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 25

- New SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 26

- New SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 27

- New SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 28

- New SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 29

- New SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 30

- New SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 31

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: Physician Assistants

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: Maria Montessori

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: Platonic Forms

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: The Eureka Effect

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: The Carrot or the Stick?

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: The Promise of Bio-Informatics

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: What is Art?

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: The Little Tramp

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: Who Really Owns American Media?

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: The Dangers of Superstition

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: Skepticism and the Scientific Method

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: The Magic of Bohemia

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: Careers in Engineeringd

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: An American Duty

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: Idol Worship in Sports

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test: The Secret Life of Photons

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 32: The Romani People

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 33: Into the Abyss

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 34: The Doctor Is In

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 35: Maslow's Hierarchy and Violence

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 36: Folklore

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 37: Age of the Drone

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 38: Policing Our Planet

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 39: The Bullroarer

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 40: Astrochemistry

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 41: Blood Ties

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 42: Out with the Old and the New

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 43: Extra, Extra

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 44: Parthenon

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 45: Where Have all the Cavemen Gone?

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 46: Chiroptera

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 47: The Tyrannical and the Taciturn

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 48

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 49

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 50: The Giants of Theater

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 51: Gravity, It's Everywhere

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 52: Do the Numbers Lie?

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 53: Draw Your Home

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 54: The Online Job Hunt

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 55: The Glass Menagerie

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 56: For Richer or For Poorer

- SAT Writing and Language Practice Test 57: Hypocrisy of Hippocratic Humorism

New SAT SAT Writing & Language Practice Tests Pdf Download

- New SAT Writing & Language Practice Test 1

- New SAT Writing & Language Practice Test 2

- New SAT Writing & Language Practice Test 3

- New SAT Writing & Language Practice Test 1 Answer Explanations

- New SAT Writing & Language Practice Test 2 Answer Explanations

- New SAT Writing & Language Practice Test 3 Answer Explanations

- New SAT Writing & Language Practice Test 4 pdf download

- New SAT Writing & Language Practice Test 5 pdf download

- New SAT Writing & Language Practice Test 6 pdf download

- New SAT Writing & Language Practice Test 7 pdf download

- New SAT Writing & Language Practice Test 8 pdf download

- New SAT Writing & Language Practice Test 9 pdf download

More Information

- HOW TO ACE THE SAT WRITING AND LANGUAGE TEST: A STRATEGY

- Introduction to SAT Writing and Language Strategy

- The SAT Writing and Language Test-Words

- The SAT Writing and Language Test-Words and Punctuation in Reverse

- The SAT Writing and Language Test-Punctuation

- The SAT Writing and Language Test-Precision Questions

- The SAT Writing and Language Test-Consistency Questions

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

- SAT Exam Info

- About the Digital SAT

- What's a Good SAT Score?

- What's Tested: SAT Math

- What's Tested: SAT Vocab

- What's Tested: SAT Reading & Writing

- What's Tested: SAT Essay

- SAT Test Dates

- SAT Study Plans

- Downloadable Study Guide

- SAT Math Tips and Tricks

- SAT Writing Tips and Tricks

- SAT Reading Tips and Tricks

- SAT Question of the Day

- SAT Pop Quiz

- SAT 20-Minute Workout

- Free SAT Practice Test

- SAT Prep Courses

SAT Essay Scoring Rubric

Sat essay scoring criteria.

- Demonstrates little or no comprehension of the source text

- Fails to show an understanding of the text’s central idea(s), and may include only details without reference to central idea(s)

- May contain numerous errors of fact and/or interpretation with regard to the text

- Makes little or no use of textual evidence

- Demonstrates some comprehension of the source text

- Shows an understanding of the text’s central idea(s) but not of important details

- May contain errors of fact and/or interpretation with regard to the text

- Makes limited and/or haphazard use of textual evidence

Three Points

- Demonstrates effective comprehension of the source text

- Shows an understanding of the text’s central idea(s) and important details

- Is free of substantive errors of fact and interpretation with regard to the text

- Makes appropriate use of textual evidence

Four Points

- Demonstrates thorough comprehension of the source text

- Shows an understanding of the text’s central idea(s) and most important details and how they interrelate

- Is free of errors of fact or interpretation with regard to the text

- Makes skillful use of textual evidence

- Demonstrates little or no cohesion and inadequate skill in the use and control of language

- May lack a clear central claim or controlling idea

- Lacks a recognizable introduction and conclusion; does not have a discernible progression of ideas

- Lacks variety in sentence structures; sentence structures may be repetitive; demonstrates general and vague word choice; word choice may be poor or inaccurate; may lack a formal style and objective tone

- Shows a weak control of the conventions of standard written English and may contain numerous errors that undermine the quality of writing

- Demonstrates little or no cohesion and limited skill in the use and control of language

- May lack a clear central claim or controlling idea or may deviate from the claim or idea

- May include an ineffective introduction and/or conclusion; may demonstrate some progression of ideas within paragraphs but not throughout

- Has limited variety in sentence structures; sentence structures may be repetitive; demonstrates general and vague word choice; word choice may be repetitive; may deviate noticeably from a formal style and objective tone

- Shows a limited control of the conventions of standard written English and contains errors that detract from the quality of writing and may impede understanding

- Is mostly cohesive and demonstrates effective use and control of language

- Includes a central claim or implicit controlling idea

- Includes an effective introduction and conclusion; demonstrates a clear progression of ideas both within paragraphs and throughout the essay

- Has variety in sentence structures; demonstrates some precise word choice; maintains a formal style and objective tone

- Shows a good control of the conventions of standards written English and is free of significant errors that detract from the quality of writing

- Is cohesive and demonstrates highly effective use and command of language

- Includes a precise central claim

- Includes a skillful introduction and conclusion; demonstrates a deliberate and highly effective progression of ideas both within paragraphs and throughout the essay

- Has a wide variety in sentence structures; demonstrates consistent use of precise word choice; maintains a formal style and objective tone

- Shows a strong command of the conventions of standards written English and is free or virtually free of errors

- Offers little or no analysis or ineffective analysis of the source text and demonstrates little to no understanding of the analytical task

- Identifies without explanation some aspects of the author’s use of evidence, reasoning, and/or stylistic and persuasive elements, and/or feature(s) of the student’s own choosing

- Numerous aspects of analysis are unwarranted based on the text

- Contains little or no support for claim(s) or point(s) made, or support is largely irrelevant

- May not focus on features of the text that are relevant to addressing the task

- Offers no discernible analysis (e.g., is largely or exclusively summary)

- Offers limited analysis of the source text and demonstrates only partial understanding of the analytical task

- Identifies and attempts to describe the author’s use of evidence, reasoning, and/or stylistic and persuasive elements, and/or feature(s) of the student’s own choosing, but merely asserts rather than explains their importance

- One or more aspects of analysis are unwarranted based on the text

- Contains little or no support for claim(s) or point(s) made

- May lack a clear focus on those features of the text that are most relevant to addressing the task

- Offers an effective analysis of the source text and demonstrates an understanding of the analytical task

- Competently evaluates the author’s use of evidence, reasoning, and/or stylistic and persuasive elements, and/or features of the student’s own choosing

- Contains relevant and sufficient support for claim(s) or point(s) made

- Focuses primarily on those features of the text that are most relevant to addressing the task

- Offers an insightful analysis of the source text and demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of the analytical task

- Offers a thorough, well-considered evaluation of the author’s use of evidence, reasoning, and/or stylistic and persuasive elements, and/or features of the student’s own choosing

- Contains relevant, sufficient, and strategically chosen support for claim(s) or point(s) made

- Focuses consistently on those features of the text that are most relevant to addressing the task

The Scoring Process

You might also like.

Call 1-800-KAP-TEST or email [email protected]

Prep for an Exam

MCAT Test Prep

LSAT Test Prep

GRE Test Prep

GMAT Test Prep

SAT Test Prep

ACT Test Prep

DAT Test Prep

NCLEX Test Prep

USMLE Test Prep

Courses by Location

NCLEX Locations

GRE Locations

SAT Locations

LSAT Locations

MCAT Locations

GMAT Locations

Useful Links

Kaplan Test Prep Contact Us Partner Solutions Work for Kaplan Terms and Conditions Privacy Policy CA Privacy Policy Trademark Directory

2024 SAT Changes: What You Need To Know

The SAT has long been synonymous with Scantron bubble sheets and #2 pencils. But on December 2, 2023, the paper-and-pencil SAT will see its final administration, and starting in March, 2024, the SAT is going completely digital. One thing not changing is the impact that a strong SAT performance can have on students’ college (and scholarship) applications, so as the test moves into its new era, let’s take a close look at the changes and, most importantly, what it means for test-takers in 2024 and beyond.

What Is Changing

The Digital SAT marks the biggest change to the SAT in a generation, if not many generations. The digital nature is one big change, but it’s far from the only change and it won’t likely be the one that impacts your score–or your SAT vs. ACT decision–the most. Here’s a summary of the major changes you should know about:

- Digital Format. This is the change that’s getting all the headlines. Like so many things in the old analog world, the paper-and-pencil test booklets, Scantron bubble sheets, and #2 pencils are giving way to laptops, tablets, and point-and-click tools. (Not to worry: you can still use your lucky #2 pencil for your scratchwork if you’d like!)

- New-Look Reading & Writing Section. This is the update that seems most likely to change how students study. Once separate sections, Reading & Writing will now appear together in the same section, and they’ll do so without their trademark long (up to 750-word) passage format. On the new test, each question will have its own short (150 words maximum) prompt.

- Reading Question Types. Along with the shortened Reading prompts comes a significantly different set of questions. Gone are the evidence-based pair questions and the paper-and-pencil “vocabulary in context” type (though some vocabulary/diction questions will still appear in a different form). The test will feature a new emphasis on supporting (and sometimes weakening) claims and hypotheses, and feature an all-new question type that asks examinees to synthesize a student’s notes.

- Shorter “Everything. ” Reading and writing prompts will be dramatically shorter, and the duration of the test will be significantly shorter, too. The test is shrinking from 3 hours long to a total testing time of 2 hours, 14 minutes, and from 154 total questions down to 98.

- Well, Almost Everything. While both the duration of the test and the number of questions will be reduced, the time allotted per question will actually increase a bit.

- Expanded Calculator Use. The SAT is also doing away with the “no calculator” math section, and in the digital format even providing an on-screen graphing calculator for students to use (though students can still use their own calculator if they’d prefer, provided it meets the test’s rules ).

- Adaptive Sections. You might ask how the SAT can ask over 35% fewer questions and still provide accurate scores. The primary factor is that the questions won’t be the same for everyone. Each student will see two Math sections and two Reading & Writing sections, and the difficulty of the second section in each discipline will vary based on the student’s performance on the first. Higher performers will see more difficult second sections with a higher maximum point value available, and those who didn’t perform as well will see more moderately-difficult second sections without as high a potential score available.

What Is Not Changing

Of course, not everything is changing. The College Board is quite confident that the scoring scale will remain the same–e.g. a 1400 next year will represent the same ability level as a 1400 did last year–and that schools will view performance the same way. And that’s because much of the test content and philosophy remains the same. Let’s break down what’s staying the same.

- Math Content Coverage. The math sections will change in number of questions and pace-per-question, and students will have access to a calculator throughout, but the same topics and question types (including numeric entry) will still apply.

- (Most) Writing Content Coverage. Generally speaking, the same grammar rules and principles of rhetoric will be tested on the new Reading & Writing section, just with a new look and feel (single questions vs. longer passages, and no “NO CHANGE” incumbent option). A few hallmarks of the old, longer Writing section–most notably questions that ask how an author should order sentences and/or whether the author should add or delete a sentence–seem to be going away.

- Scoring Scale. The adaptive nature of test sections slightly changes the way that scores are calculated, given that the difficulty of questions now factors in compared to a simple number correct/incorrect, but the scores will still be on a 400-1600 scale and, generally speaking, the criteria for “what’s a good score” at your target schools will remain constant, too.

What That Means For You

Practicing with the Digital SAT tools is important. By 2024, most students should be more than comfortable with the concept of doing academic work on a computer or tablet. So it’s not the mere fact that the SAT is digital that’s important–it’s how aware and comfortable a student is with the specific tools themselves. Notably, these tools include:

- An optional on-screen graphing calculator. Powered by Desmos, this calculator is a great option for many students–but will work a bit differently from your handheld graphing calculator. To decide which you prefer, you’ll want to practice with both options. And if you plan to use the on-screen calculator, you’ll want the quick muscle memory to graph, calculate, backspace, and clear without having to think about the functions.

- An annotation tool to add notes to text. Since you can’t circle words or jot notes like you might on the paper test, this tool exists to let you add notes on the screen. But it’s only available for the Reading & Writing section and you’ll want to test it out to see how well it works for you and ensure that you’re able to use it quickly.

- A flagging tool to highlight questions to return to. Along with the menu to see all questions, this enables you to hop between questions to manage your time, but again you’ll want to build speed with it so that it works, as intended, as a time-saver and not a time-waster.

- A countdown clock. You can toggle between “hide” and “show” the allotted time remaining. The clock can be distracting to some students if it’s constantly ticking in front of you; others like having it persistently there. To know what works for you–and to have a plan for when you’ll toggle it on vs. off to check your pace–again you’ll want to practice.

- A formula reference sheet for math. Make sure you know which formulas are available and which are not.

- Keyboard shortcuts. If you plan to use these shortcuts, as with these other tools make sure you spend the time beforehand to get them to the point where they really do save you time on test day.

Reading questions require specific preparation. For 11th graders who took a fall, paper SAT, or anyone who’s borrowed test prep materials from the earlier version, the Reading questions in particular will look a lot different and require a significantly different skill set. Most notably:

- With 54 total verbal questions, you’ll face an incredible variety of topics and have to context-switch often. Pro tip: read the question stems first so that you know your “job” prior to reading each new topic.

- The question type that asks you to synthesize notes is all-new and unique to the SAT. Pro tip: the purpose outlined in the question stem is the most important phrase of all.

- Short-form passages require a more narrow type of reading comprehension. Many questions will come down to one or two key words in a high-leverage part of the question so you’ll want to train yourself to focus on that precision in language and to know where on each type of question to most direct your focus. Pro tip: when you’re asked to support a theory or claim, the specific adjectives and modifiers in that theory/claim really matter.

- Vocabulary/diction questions no longer ask you for the meaning of a word, but instead to fit the proper word into a blank. Pro tip: the whole prompt matters, so make sure you understand the context from the sentences that don’t have the blank, too.

Minimize mistakes and pacing issues. The shortened, adaptive SAT test format puts a bit of extra emphasis on making every question count. Fewer questions means that a silly or careless mistake makes up a higher percentage of your score than before, and the adaptive nature of the test means that a mistake like that could have even outsized importance. Here’s why:

- A shorter test magnifies mistakes. On a longer test, one careless mistake gets diluted by your performance on so many more questions. And the same is true of timing: over the course of a longer test, you have more time to make up for a wasted minute. The shorter the test, the more a single mistake drags you back from your true ability.

- Section adaptivity can, in some cases, really magnify a mistake. By and large you shouldn’t worry about the adaptivity of the SAT at all (more on that later). But one thing you should know is that there is a dividing line on your first section of each discipline that determines whether you get the advanced second section and its higher potential point value. And if one or two silly mistakes drag you behind that line, that could artificially cap your score by not giving you a chance at that advanced second section.

Importantly, this doesn’t mean that you should be intimidated or paranoid throughout each section! But what it does mean is that 1) you should use practice tests to identify the types of mistakes you make under pressure so that you’re aware of them on the exam, 2) you should practice pacing so that you have a plan to not run short on time and miss questions you should get right, and 3) you should use any extra time you have double-checking for common mistakes so that you don’t “give back” any points that should be yours.

What that doesn’t mean for you

Don’t try to game the adaptive algorithm. With any adaptive test, there’s always a temptation to spend more time trying to hack the algorithm than studying to just rack up correct answers. And do you know what the algorithm favors most? Correct answers–they’re the best way to “hack” your way to a high score.

Adaptive testing is new to the SAT but has been used for a great many tests over decades, and the story is always the same: the time and focus you spend trying to gain an edge doesn’t gain you any points, whereas that same time and energy spent on shoring up shaky skills can really improve your score. Trust the psychometricians (standardized test data scientists) and work to build your skills and familiarity with the questions.

Don’t (completely) throw out old test prep materials. If your sister or friend swears by her flashcards or test-taking strategies, you can still largely put them to good use! Anything related to math, grammar, testing strategy (e.g. using answer choices as assets or plugging in numbers for certain algebra problems) can still very much help you. Just know that Reading is dramatically different, Writing questions look a lot different, and you’ll want to make sure you do a lot of practice with Digital SAT specific problems…the other tools can serve as a good supplement.