An official website of the United States government, Department of Justice.

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

The Justice System

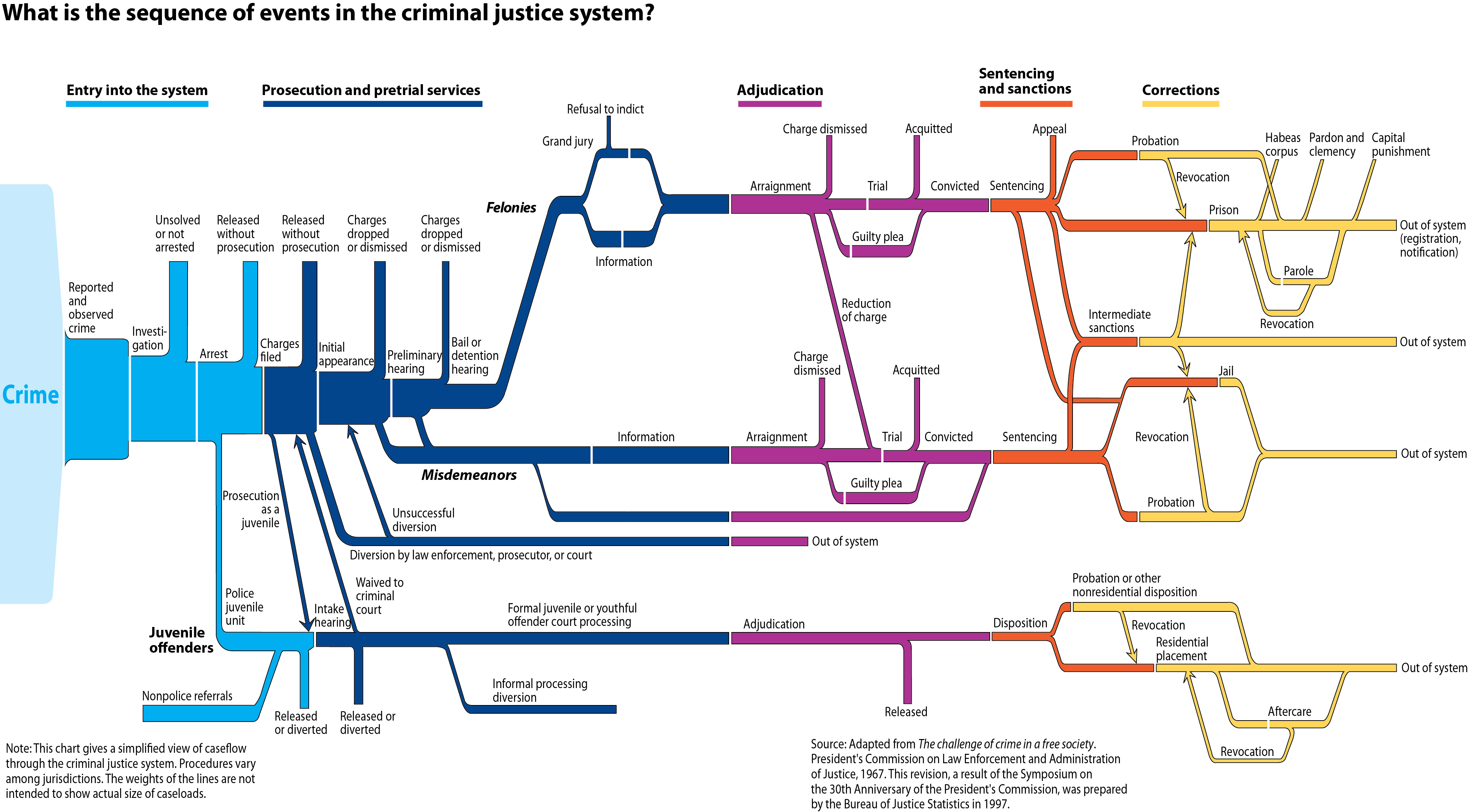

What is the sequence of events in the criminal justice system.

To text description | To a larger version of the chart | Download high resolution version (.zip)

The flowchart of the events in the criminal justice system (shown in the diagram) updates the original chart prepared by the President's Commission on Law Enforcement and the Administration of Justice in 1967. The chart summarizes the most common events in the criminal and juvenile justice systems including entry into the criminal justice system, prosecution and pretrial services, adjudication, sentencing and sanctions, and corrections. A discussion of the events in the criminal justice system follows.

|

| |

The response to crime

The private sector initiates the response to crime

This first response may come from individuals, families, neighborhood associations, business, industry, agriculture, educational institutions, the news media, or any other private service to the public.

It involves crime prevention as well as participation in the criminal justice process once a crime has been committed. Private crime prevention is more than providing private security or burglar alarms or participating in neighborhood watch. It also includes a commitment to stop criminal behavior by not engaging in it or condoning it when it is committed by others.

Citizens take part directly in the criminal justice process by reporting crime to the police, by being a reliable participant (for example, a witness or a juror) in a criminal proceeding and by accepting the disposition of the system as just or reasonable. As voters and taxpayers, citizens also participate in criminal justice through the policymaking process that affects how the criminal justice process operates, the resources available to it, and its goals and objectives. At every stage of the process from the original formulation of objectives to the decision about where to locate jails and prisons to the reintegration of inmates into society, the private sector has a role to play. Without such involvement, the criminal justice process cannot serve the citizens it is intended to protect.

The response to crime and public safety involves many agencies and services

Many of the services needed to prevent crime and make neighborhoods safe are supplied by noncriminal justice agencies, including agencies with primary concern for public health, education, welfare, public works, and housing. Individual citizens as well as public and private sector organizations have joined with criminal justice agencies to prevent crime and make neighborhoods safe.

Criminal cases are brought by the government through the criminal justice system

We apprehend, try, and punish offenders by means of a loose confederation of agencies at all levels of government. Our American system of justice has evolved from the English common law into a complex series of procedures and decisions. Founded on the concept that crimes against an individual are crimes against the State, our justice system prosecutes individuals as though they victimized all of society. However, crime victims are involved throughout the process and many justice agencies have programs which focus on helping victims.

There is no single criminal justice system in this country. We have many similar systems that are individually unique. Criminal cases may be handled differently in different jurisdictions, but court decisions based on the due process guarantees of the U.S. Constitution require that specific steps be taken in the administration of criminal justice so that the individual will be protected from undue intervention from the State.

The description of the criminal and juvenile justice systems that follows portrays the most common sequence of events in response to serious criminal behavior.

To contents

The justice system does not respond to most crime because so much crime is not discovered or reported to the police. Law enforcement agencies learn about crime from the reports of victims or other citizens, from discovery by a police officer in the field, from informants, or from investigative and intelligence work.

Once a law enforcement agency has established that a crime has been committed, a suspect must be identified and apprehended for the case to proceed through the system. Sometimes, a suspect is apprehended at the scene; however, identification of a suspect sometimes requires an extensive investigation. Often, no one is identified or apprehended. In some instances, a suspect is arrested and later the police determine that no crime was committed and the suspect is released.

After an arrest, law enforcement agencies present information about the case and about the accused to the prosecutor, who will decide if formal charges will be filed with the court. If no charges are filed, the accused must be released. The prosecutor can also drop charges after making efforts to prosecute (nolle prosequi).

A suspect charged with a crime must be taken before a judge or magistrate without unnecessary delay. At the initial appearance, the judge or magistrate informs the accused of the charges and decides whether there is probable cause to detain the accused person. If the offense is not very serious, the determination of guilt and assessment of a penalty may also occur at this stage.

Often, the defense counsel is also assigned at the initial appearance. All suspects prosecuted for serious crimes have a right to be represented by an attorney. If the court determines the suspect is indigent and cannot afford such representation, the court will assign counsel at the public's expense.

A pretrial-release decision may be made at the initial appearance, but may occur at other hearings or may be changed at another time during the process. Pretrial release and bail were traditionally intended to ensure appearance at trial. However, many jurisdictions permit pretrial detention of defendants accused of serious offenses and deemed to be dangerous to prevent them from committing crimes prior to trial.

The court often bases its pretrial decision on information about the defendant's drug use, as well as residence, employment, and family ties. The court may decide to release the accused on his/her own recognizance or into the custody of a third party after the posting of a financial bond or on the promise of satisfying certain conditions such as taking periodic drug tests to ensure drug abstinence.

In many jurisdictions, the initial appearance may be followed by a preliminary hearing. The main function of this hearing is to discover if there is probable cause to believe that the accused committed a known crime within the jurisdiction of the court. If the judge does not find probable cause, the case is dismissed; however, if the judge or magistrate finds probable cause for such a belief, or the accused waives his or her right to a preliminary hearing, the case may be bound over to a grand jury.

A grand jury hears evidence against the accused presented by the prosecutor and decides if there is sufficient evidence to cause the accused to be brought to trial. If the grand jury finds sufficient evidence, it submits to the court an indictment, a written statement of the essential facts of the offense charged against the accused.

Where the grand jury system is used, the grand jury may also investigate criminal activity generally and issue indictments called grand jury originals that initiate criminal cases. These investigations and indictments are often used in drug and conspiracy cases that involve complex organizations. After such an indictment, law enforcement tries to apprehend and arrest the suspects named in the indictment.

Misdemeanor cases and some felony cases proceed by the issuance of an information, a formal, written accusation submitted to the court by a prosecutor. In some jurisdictions, indictments may be required in felony cases. However, the accused may choose to waive a grand jury indictment and, instead, accept service of an information for the crime.

In some jurisdictions, defendants, often those without prior criminal records, may be eligible for diversion from prosecution subject to the completion of specific conditions such as drug treatment. Successful completion of the conditions may result in the dropping of charges or the expunging of the criminal record where the defendant is required to plead guilty prior to the diversion.

Once an indictment or information has been filed with the trial court, the accused is scheduled for arraignment. At the arraignment, the accused is informed of the charges, advised of the rights of criminal defendants, and asked to enter a plea to the charges. Sometimes, a plea of guilty is the result of negotiations between the prosecutor and the defendant.

If the accused pleads guilty or pleads nolo contendere (accepts penalty without admitting guilt), the judge may accept or reject the plea. If the plea is accepted, no trial is held and the offender is sentenced at this proceeding or at a later date. The plea may be rejected and proceed to trial if, for example, the judge believes that the accused may have been coerced.

If the accused pleads not guilty or not guilty by reason of insanity, a date is set for the trial. A person accused of a serious crime is guaranteed a trial by jury. However, the accused may ask for a bench trial where the judge, rather than a jury, serves as the finder of fact. In both instances the prosecution and defense present evidence by questioning witnesses while the judge decides on issues of law. The trial results in acquittal or conviction on the original charges or on lesser included offenses.

After the trial a defendant may request appellate review of the conviction or sentence. In some cases, appeals of convictions are a matter of right; all States with the death penalty provide for automatic appeal of cases involving a death sentence. Appeals may be subject to the discretion of the appellate court and may be granted only on acceptance of a defendant's petition for a writ of certiorari. Prisoners may also appeal their sentences through civil rights petitions and writs of habeas corpus where they claim unlawful detention.

After a conviction, sentence is imposed. In most cases the judge decides on the sentence, but in some jurisdictions the sentence is decided by the jury, particularly for capital offenses.

In arriving at an appropriate sentence, a sentencing hearing may be held at which evidence of aggravating or mitigating circumstances is considered. In assessing the circumstances surrounding a convicted person's criminal behavior, courts often rely on presentence investigations by probation agencies or other designated authorities. Courts may also consider victim impact statements.

The sentencing choices that may be available to judges and juries include one or more of the following:

- the death penalty

- incarceration in a prison, jail, or other confinement facility

- probation - allowing the convicted person to remain at liberty but subject to certain conditions and restrictions such as drug testing or drug treatment

- fines - primarily applied as penalties in minor offenses

- restitution - requiring the offender to pay compensation to the victim.

In some jurisdictions, offenders may be sentenced to alternatives to incarceration that are considered more severe than straight probation but less severe than a prison term. Examples of such sanctions include boot camps, intense supervision often with drug treatment and testing, house arrest and electronic monitoring, denial of Federal benefits, and community service.

In many jurisdictions, the law mandates that persons convicted of certain types of offenses serve a prison term. Most jurisdictions permit the judge to set the sentence length within certain limits, but some have determinate sentencing laws that stipulate a specific sentence length that must be served and cannot be altered by a parole board.

Offenders sentenced to incarceration usually serve time in a local jail or a State prison. Offenders sentenced to less than 1 year generally go to jail; those sentenced to more than 1 year go to prison. Persons admitted to the Federal system or a State prison system may be held in prisons with varying levels of custody or in a community correctional facility.

A prisoner may become eligible for parole after serving a specific part of his or her sentence. Parole is the conditional release of a prisoner before the prisoner's full sentence has been served. The decision to grant parole is made by an authority such as a parole board, which has power to grant or revoke parole or to discharge a parolee altogether. The way parole decisions are made varies widely among jurisdictions.

Offenders may also be required to serve out their full sentences prior to release (expiration of term). Those sentenced under determinate sentencing laws can be released only after they have served their full sentence (mandatory release) less any "goodtime" received while in prison. Inmates get goodtime credits against their sentences automatically or by earning them through participation in programs.

If released by a parole board decision or by mandatory release, the releasee will be under the supervision of a parole officer in the community for the balance of his or her unexpired sentence. This supervision is governed by specific conditions of release, and the releasee may be returned to prison for violations of such conditions.

Once the suspects, defendants, or offenders are released from the jurisdiction of a criminal justice agency, they may be processed through the criminal justice system again for a new crime. Long term studies show that many suspects who are arrested have prior criminal histories and those with a greater number of prior arrests were more likely to be arrested again. As the courts take prior criminal history into account at sentencing, most prison inmates have a prior criminal history and many have been incarcerated before. Nationally, about half the inmates released from State prison will return to prison.

For statistics on this subject, see -- Juvenile justice and facts and figures

The juvenile justice system

Juvenile courts usually have jurisdiction over matters concerning children, including delinquency, neglect, and adoption. They also handle "status offenses" such as truancy and running away, which are not applicable to adults. State statutes define which persons are under the original jurisdiction of the juvenile court. The upper age of juvenile court jurisdiction in delinquency matters is 17 in most States.

The processing of juvenile offenders is not entirely dissimilar to adult criminal processing, but there are crucial differences. Many juveniles are referred to juvenile courts by law enforcement officers, but many others are referred by school officials, social services agencies, neighbors, and even parents, for behavior or conditions that are determined to require intervention by the formal system for social control.

At arrest, a decision is made either to send the matter further into the justice system or to divert the case out of the system, often to alternative programs. Examples of alternative programs include drug treatment, individual or group counseling, or referral to educational and recreational programs.

When juveniles are referred to the juvenile courts, the court's intake department or the prosecuting attorney determines whether sufficient grounds exist to warrant filing a petition that requests an adjudicatory hearing or a request to transfer jurisdiction to criminal court. At this point, many juveniles are released or diverted to alternative programs.

All States allow juveniles to be tried as adults in criminal court under certain circumstances. In many States, the legislature statutorily excludes certain (usually serious) offenses from the jurisdiction of the juvenile court regardless of the age of the accused. In some States and at the Federal level under certain circumstances, prosecutors have the discretion to either file criminal charges against juveniles directly in criminal courts or proceed through the juvenile justice process. The juvenile court's intake department or the prosecutor may petition the juvenile court to waive jurisdiction to criminal court. The juvenile court also may order referral to criminal court for trial as adults. In some jurisdictions, juveniles processed as adults may upon conviction be sentenced to either an adult or a juvenile facility.

In those cases where the juvenile court retains jurisdiction, the case may be handled formally by filing a delinquency petition or informally by diverting the juvenile to other agencies or programs in lieu of further court processing.

If a petition for an adjudicatory hearing is accepted, the juvenile may be brought before a court quite unlike the court with jurisdiction over adult offenders. Despite the considerable discretion associated with juvenile court proceedings, juveniles are afforded many of the due-process safeguards associated with adult criminal trials. Several States permit the use of juries in juvenile courts; however, in light of the U.S. Supreme Court holding that juries are not essential to juvenile hearings, most States do not make provisions for juries in juvenile courts.

In disposing of cases, juvenile courts usually have far more discretion than adult courts. In addition to such options as probation, commitment to a residential facility, restitution, or fines, State laws grant juvenile courts the power to order removal of children from their homes to foster homes or treatment facilities. Juvenile courts also may order participation in special programs aimed at shoplifting prevention, drug counseling, or driver education.

Once a juvenile is under juvenile court disposition, the court may retain jurisdiction until the juvenile legally becomes an adult (at age 21in most States). In some jurisdictions, juvenile offenders may be classified as youthful offenders which can lead to extended sentences.

Following release from an institution, juveniles are often ordered to a period of aftercare which is similar to parole supervision for adult offenders. Juvenile offenders who violate the conditions of aftercare may have their aftercare revoked, resulting in being recommitted to a facility. Juveniles who are classified as youthful offenders and violate the conditions of aftercare may be subject to adult sanctions.

The structure of the justice system

The governmental response to crime is founded in the intergovernmental structure of the United States

Under our form of government, each State and the Federal Government has its own criminal justice system. All systems must respect the rights of individuals set forth in court interpretation of the U.S. Constitution and defined in case law.

State constitutions and laws define the criminal justice system within each State and delegate the authority and responsibility for criminal justice to various jurisdictions, officials, and institutions. State laws also define criminal behavior and groups of children or acts under jurisdiction of the juvenile courts.

Municipalities and counties further define their criminal justice systems through local ordinances that proscribe the local agencies responsible for criminal justice processing that were not established by the State.

Congress has also established a criminal justice system at the Federal level to respond to Federal crimes such a bank robbery, kidnaping, and transporting stolen goods across State lines.

The response to crime is mainly a State and local function

Very few crimes are under exclusive Federal jurisdiction. The responsibility to respond to most crime rests with State and local governments. Police protection is primarily a function of cities and towns. Corrections is primarily a function of State governments. Most justice personnel are employed at the local level.

Discretion is exercised throughout the criminal justice system

Discretion is "an authority conferred by law to act in certain conditions or situations in accordance with an official's or an official agency's own considered judgment and conscience." 1 Discretion is exercised throughout the government. It is a part of decision-making in all government systems from mental health to education, as well as criminal justice. The limits of discretion vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

Concerning crime and justice, legislative bodies have recognized that they cannot anticipate the range of circumstances surrounding each crime, anticipate local mores, and enact laws that clearly encompass all conduct that is criminal and all that is not. 2 Therefore, persons charged with the day-to-day response to crime are expected to exercise their own judgment within limits set by law. Basically, they must decide -

- whether to take action

- where the situation fits in the scheme of law, rules, and precedent

- which official response is appropriate. 3

To ensure that discretion is exercised responsibly, government authority is often delegated to professionals. Professionalism requires a minimum level of training and orientation, which guide officials in making decisions. The professionalism of policing is due largely to the desire to ensure the proper exercise of police discretion.

The limits of discretion vary from State to State and locality to locality. For example, some State judges have wide discretion in the type of sentence they may impose. In recent years other States have sought to limit the judges discretion in sentencing by passing mandatory sentencing laws that require prison sentences for certain offenses.

1 Roscoe Pound, "Discretion, dispensation and mitigation: The problem of the individual special case," New York University Law Review (1960) 35:925, 926.

2 Wayne R. LaFave, Arrest: The decision to take a suspect into custody (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1964), p. 63-184.

3 Memorandum of June 21, 1977, from Mark Moore to James Vorenberg, "Some abstract notes on the issue of discretion."

| These criminal justice officials... | must often decide whether or not or how to ... |

|---|---|

| -Enforce specific laws -Investigate specific crimes -Search people, vicinities, buildings -Arrest or detain people | |

| -File charges or petitions for adjudication -Seek indictments -Drop cases -Reduce charges | |

| -Set bail or conditions for release -Accept pleas -Determine delinquency -Dismiss charges -Impose sentence -Revoke probation | |

| -Assign to type of correctional facility -Award privileges -Punish for disciplinary infractions | |

| Determine date and conditions of parole Revoke parole | |

An official website of the United States government, Department of Justice.

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

How Research Is Translated to Policy and Practice in the Criminal Justice System

A recent NIJ-funded study of Florida’s correctional systems has shed new light on the question of how research is translated into policy and practice in the criminal justice system. Researchers found that the most common ways to effectively translate research to policy and practice included making the information easier to understand, more credible and more applicable to local circumstances; instead of presenting information in the academic research format that tends to be more complex and difficult to understand. The findings also indicated that the most successful way to translate research involved regular interactions between researchers and practitioners — specifically, that academics could do more to communicate and collaborate with policymakers and practitioners.

This study was carried out by scholars at Florida State University (FSU). The goal of the study was to describe the use of research and other factors in developing state-level juvenile and adult correctional policy and practice in the state of Florida and answer targeted questions, such as:

- What sources of information do Florida’s correctional policymakers use to make their decisions and how much influence do these factors have?

- What are the primary strategies used to inform policy with research evidence and what methods would help policymakers use evidence-based information in their decision-making process?

- What is the underlying process for research translation in shaping how policymakers assess and respond to problems?

To achieve their goal, the researchers used data from several sources, including:

- Relevant literature on research and public policy in criminal justice.

- Relevant legislative and state agency documents.

- Interviews and web surveys with established academic researchers and key decision makers from state agencies and legislative practitioners and policymakers.

- Observations of archived, pre-recorded legislative public hearings and committee meetings.

Prior literature was examined to identify themes (e.g., barriers, facilitators) for developing the interview and survey instruments that were to be used. An advisory panel of criminology research experts at FSU was then consulted about the project’s research design and methods. A total of eight academic researchers, eight practitioners and four policymakers were interviewed in person to explore “why” and “how” themes (e.g., “why” barriers may get in the way of knowledge translation and “how” certain strategies may help to translate research to policy and practice). Upon completing the interviews, online follow-up surveys were sent to the participants to compare and validate findings from past research about processes underlying research translation. In order to investigate process models of translational criminology, participants were also asked about researcher/practitioner partnerships during the interviews and follow-up surveys. In addition to the data from interviews and surveys, this study also examined four policy cases to assess how research was used in resulting policy/legislation.

Barriers to research translation and other influential factors

During the interviews, participants consistently mentioned six types of barriers or challenges to the research, knowledge and translation process. These barriers/challenges were (in descending order from the most to least frequently mentioned):

- Difficulty in interpreting and using research.

- Lack of support from leadership in using research.

- Differences in training between policymakers/practitioners versus researchers.

- Relationship issues (i.e., distrust, lack of access or lack of engagement between or within agencies or between academics and policymakers/practitioners).

- Budget and fiscal restrictions (e.g., limited research funds).

- Tendency for criminal justice policymaking to be event driven, which may not be compatible with the generally longer research process.

In addition to these barriers in using research, four influential factors other than research that interviewees mentioned as having a significant impact on correctional policy and practice included (in descending order from the most to least frequently mentioned): political ideology, special interest groups (e.g., advocacy), public opinion and the media.

The surveys also highlighted how much influence certain factors have on correctional policy and practice, such as fiscal constraints of correctional organizations, ranked as having the strongest influence, followed by political ideology and growing cost of incarceration. Notably, academic research, public opinion and social media were the three factors identified as having the weakest influence on correctional policy and practice. Lastly, respondents reported that they believed research has more of an influence on juvenile policies (50 percent endorsed) compared to adult policies (28 percent endorsed).

Kinds of evidence and research used by practitioners

Review of the policy case summaries showed that there was little evidence on the use of academic research in official legislative documents and public testimony. However, the interviews with research use, suggesting that official public documents may not be the sole or best resource to turn to when exploring research translation for a given policy.

Interviewee responses identified six main ways that policymakers and practitioners acquired evidence to inform their decision making, which included (in descending order from the most to least frequently mentioned): (1) government-sponsored or conducted research, (2) peer networking (e.g., other state practitioners), (3) intermediary policy and research organizations, (4) policy taskforces and councils, (5) peer reviewed research and (6) expert testimony.

Survey results also showed that researcher/practitioner partnerships were the most effective mechanism of knowledge translation and academic journals and social media were the least effective.

The interaction model: Most successful for research translation

The study’s researchers found that the process model most often linked to successful research knowledge translation in corrections was the interaction model, which involves relationships, partnerships and bidirectional communication between researchers and practitioners. An example of this model is researcher/ practitioner partnerships (RPPs). Participants of the study stated that long-term relationships and RPPs were among the most effective ways to translate research knowledge into correctional policy and practice.

How researchers and practitioners can improve research translation

Six main effective facilitators.

Interview results pointed to six main facilitators that make it easier to increase and improve the use of research to inform policy/practice, which included (in descending order from the most to least frequently mentioned):

- Relationships (e.g., trust, reciprocity).

- Involvement in the evidence-based movement (e.g., focus on using data to figure out best practices).

- Leadership’s support of research use in decision making.

- Research that makes concrete recommendations or is easy to understand (e.g., randomized control trials).

- Scarcity of budget, which pushes policymakers/practitioners to focus on evidence-based methods.

- Cross-training (e.g., researchers, engaging in policy research).

Five effective strategies

The interviews also pointed out five strategies to help improve the use of research, including:

- Increased investment in research.

- Support for research/practitioner partnerships.

- Ongoing task forces comprised of a range of individuals (e.g., researchers, criminal justice agency members and community agency members).

- Academics reaching out to practitioners (e.g., via practitioner- focused conferences).

- Cross-training researchers and practitioners.

Concluding remarks

This study shed light on how research is translated to correctional policy and practice, as well as methods to improve this process, with three important take-away points. First, the study found that government research, peer networking and policy/research organizations were the most frequently used sources for the research translation process, rather than academic publications and expert testimony. This is most likely because the aforementioned types of evidence are easier to understand, seen as more credible and can more easily be applied to local settings. Second, the study found that successful research translation is most likely to occur when researchers and practitioners build meaningful relationships and regularly interact and communicate to establish trust, credibility and reciprocity. Lastly, the study had important policy implications, especially for academics, specifically that academic researchers should be proactive in reaching out and working with policymakers and practitioners, as well as becoming involved in correctional policy and practice (e.g., through graduate courses that train students in conducting policy research).

About this Article

This article is based on research funded under grant 2014-IJ-CX-0035 awarded to the Florida State University. This article is based on the final report, “Translational Criminology — Research and Public Policy: Final Summary Report” (pdf, 44 pages) by George B. Pesta, Javier Ramos, J.W. Andrew Ranson, Alexa Singer, and Thomas G. Blomberg.

About the author

Yunsoo Park is a former visiting fellow at the National Institute of Justice.

Cite this Article

Read more about:, related publications.

- Translational Criminology - Research and Public Policy: Final Summary Report

Related Awards

- Translational Criminology: Research and Public Policy

3.2 Research Methods

It is important to study research methods to determine which method would work best in a particular scenario. Below we will examine the top five research methods used by criminologists today: survey, longitudinal, meta analysis, quasi-experimental research, cross-sectional research methods, and the gold standard of research methods – randomized control trial (RCT) method. (trudi)

3.2.1 Survey Research Method

Survey research is a quantitative and qualitative method with two important characteristics. First, the variables of interest are measured using self-reports. In essence, survey researchers ask their participants (who are often called respondents ) to report directly on their own thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Second, considerable attention is paid to the issue of sampling. In particular, survey researchers have a strong preference for large random samples because they provide the most accurate estimates of what is true in the population. In fact, survey research may be the only approach in which random sampling is routinely used. Beyond these two characteristics, almost anything goes in survey research. Surveys can be long or short. They can be conducted in person, by telephone, through the mail, or over the Internet. They can be about voting intentions, consumer preferences, social attitudes, health, or anything else that it is possible to ask people about and receive meaningful answers. Although survey data are often analyzed using statistics, there are many questions that lend themselves to more qualitative analysis.

3.2.2 Meta Analysis Research Method

Meta-analysis is a research method that involves combining data from multiple studies to draw conclusions about a particular research question or topic. The goal of a meta-analysis is to identify consistent patterns or trends across studies, which can provide more reliable and precise estimates of the effects of an intervention or factor than any single study could provide on its own.

To conduct a meta-analysis, researchers typically begin by identifying a research question and a set of studies that have investigated that question. They then use statistical methods to combine the results of those studies, often weighting each study according to its sample size or other factors. By combining the results of multiple studies, meta-analysis can help to identify consistent findings across studies, as well as identify factors that may explain variability in results across studies.

One example of how a criminologist might employ meta-analysis is to examine the effectiveness of a particular intervention aimed at reducing crime, such as a community policing program. By conducting a meta-analysis of studies that have investigated the effectiveness of community policing, a criminologist could identify whether the intervention consistently leads to reductions in crime across different settings, populations, and study designs. They could also identify factors that may moderate the effectiveness of the intervention, such as the quality of implementation, the characteristics of the community, or the nature of the crime problem being addressed. Such findings could help policymakers and practitioners to make more informed decisions about how to allocate resources and implement crime reduction strategies. (chat gpt)

3.2.3 Quasi-Experimental Research Method

The prefix quasi means “resembling.” Thus quasi-experimental research is research that resembles experimental research but is not true experimental research. Although the independent variable is manipulated, participants are not randomly assigned to conditions or orders of conditions (Cook & Campbell, 1979). Because the independent variable is manipulated before the dependent variable is measured, quasi-experimental research eliminates the directionality problem. But because participants are not randomly assigned—making it likely that there are other differences between conditions—quasi-experimental research does not eliminate the problem of confounding variables. In terms of internal validity, therefore, quasi-experiments are generally somewhere between correlational studies and true experiments.

Quasi-experiments are most likely to be conducted in field settings in which random assignment is difficult or impossible. They are often conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of a treatment or program. A criminal justice example of a quasi-experimental research method is the evaluation of a new correctional program in a state prison system. Suppose that a new educational program is implemented in one prison, but not in another prison, due to resource constraints. The correctional system may want to evaluate the impact of the program on the outcomes of the participating prisoners, such as recidivism rates or successful reentry into society after release.

To evaluate the program’s impact, researchers could use a quasi-experimental design by comparing the outcomes of prisoners who participate in the program with those who do not. However, since participation in the program is not randomly assigned, the researchers must take steps to control for other factors that may influence the outcomes, such as prior criminal history or demographic characteristics.

One way to control for these factors is to use statistical techniques, such as regression analysis or propensity score matching, to create comparable groups of participants and non-participants. The researchers can then compare the outcomes of these two groups to evaluate the program’s impact, while accounting for potential confounding factors.

This type of quasi-experimental research design can help correctional systems and policymakers to make informed decisions about the effectiveness of new programs, without requiring the time and resources necessary for a randomized controlled trial. However, it is important to note that quasi-experimental designs may be more prone to bias than randomized controlled trials, and therefore, the findings should be interpreted with caution. (trudi / chat gpt)

3.2.4 Cross-Sectional Research Method

A cross-sectional research method is a research design that involves collecting data from a sample of individuals at a single point in time. A criminal justice example of a cross-sectional research method is a survey of public attitudes towards the police. In this study, a sample of individuals from a particular community or region would be selected and asked to complete a survey about their perceptions of the police, their confidence in the police, and their experiences with the police.

The survey would be administered at a single point in time, such as over the course of a week or a month. The data collected from the survey would provide a snapshot of public attitudes towards the police in the community during that period.

The findings from this cross-sectional research method could help law enforcement agencies to understand the perceptions of the public towards their work, identify areas of concern, and develop strategies to improve police-community relations. For example, if the survey reveals that a significant portion of the community does not trust the police, law enforcement agencies may consider implementing programs to improve transparency and accountability, or increase community engagement efforts.

However, it is important to note that cross-sectional research designs can only provide a snapshot of a particular point in time, and cannot provide information about how attitudes and perceptions may change over time. Longitudinal research designs that track changes in attitudes over time may be necessary to fully understand how attitudes towards the police may be influenced by events or interventions. (trudi / chat gpt)

3.2.5 Randomized Control Trial (RCT) Research Method

A Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) is a research method that involves randomly assigning participants to different groups, typically an intervention group and a control group, to test the effectiveness of an intervention or treatment. The goal of an RCT is to minimize bias and establish a causal relationship between the intervention and the outcome being studied.

- Good randomization will “wash out” any population bias

- Results can be analyzed with established statistical tools

- Populations of participating individuals are clearly identified

Disadvantages

- Expensive in terms of time and money

- Volunteer biases: the population that participates in the study may not be representative of the actual entire population

A criminal justice example of an RCT is the evaluation of a new education program for first-time offenders. In this study, a group of first-time offenders would be randomly assigned to either the intervention group or the control group. The intervention group would participate in free college courses and research opportunities for college credit as well as other types of support to address the underlying causes of their criminal behavior. The control group, on the other hand, would not receive the education program or support and would continue with the traditional criminal justice process.

After the intervention period, both groups would be assessed for outcomes such as recidivism rates or successful completion of probation. The researchers would then compare the outcomes of the two groups to evaluate the effectiveness of the diversion program.

A RCT in this criminal justice setting would provide strong evidence of the effectiveness of the diversion program, since the random assignment of participants to groups would help to control for other factors that may influence the outcomes. By establishing a causal relationship between the intervention and the outcomes, this RCT could help policymakers and practitioners to make informed decisions about the implementation and expansion of the diversion program to reduce recidivism and improve outcomes for first-time offenders. (trudi / chat gpt)

3.2.6 Impact on People’s Lives

Scientific research is a critical tool for successfully navigating our complex world. Without it, we would be forced to rely solely on intuition, other people’s authority, and blind luck. While many of us feel confident in our abilities to decipher and interact with the world around us, history is filled with examples of how very wrong we can be when we fail to recognize the need for evidence in supporting claims. At various times in history, we would have been certain that the sun revolved around a flat earth, that the earth’s continents did not move, and that mental illness was caused by possession. It is through systematic scientific research that we divest ourselves of our preconceived notions and superstitions and gain an objective understanding of ourselves and our world.

Specifically in the field of criminal justice, research is critical because it provides a scientific and evidence-based approach to understanding and addressing the complex problems and issues that arise in the justice system. Through research, criminal justice professionals can gain a better understanding of the root causes of crime, the effectiveness of different intervention programs, and the impact of various policies and practices on public safety and community well-being.

In addition, research helps to identify and address biases and disparities in the criminal justice system. Through rigorous and objective research, criminal justice professionals can gain a better understanding of the factors that contribute to disparities in policing, sentencing, and other aspects of the justice system, and develop evidence-based solutions to address these issues. The Crime Prevention Science sections of each chapter in this textbook provide examples of such research and these sections are included in every chapter to demonstrate how important research is to the improvement of our criminal justice system.

Overall, research is critical in the field of criminal justice because it helps to promote evidence-based practices, improve outcomes, and ensure that the justice system operates fairly and equitably for all.

3.2.7 Statistics on “Other Groups”

Conducting research relies on gathering accurate and reliable data. When analyzing inequities within the Criminal Justice System, race and ethnicity are two of the variables gathered and considered in the research. However, how race and ethnicity are represented in the research can skew the data and cause challenges. For example, the U.S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB) disaggregates race into the following categories:

- American Indian or Alaska Native

- Black or African American

- Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander

And ethnicity into the following categories:

- Hispanic or Latino

- Not Hispanic or Latino

Simply using these categories can, in and of itself, cause distention and misinformation in how one self-identifies, in that not everyone feels they fit into these groupings. Over the years, the OMB has conducted reviews of race and ethnicity categories and have made some changes, and yet many still do not feel they fit within these prescribed groups. For example, someone may identify with the ethnicity of Hispanic or Latino but may not identify with any of the prescribed race categories. Thus if they chose to leave the race category blank the data would be incomplete or if the race category was a required field, the person may feel compelled to just choose one of the options, even if they didn’t identify as it, thus providing inaccurate information.

Although researchers have the ability to expand these categories, if they so choose, this too can cause misinformation as some research may have more disaggregated data than others. Researchers are also not required to expand these categories, except in a few specific situations, like those in the state of New York in which in December 2021, Governor Kathy Hochul signed New York State Law S.6639-A/A.6896-A. The law requires state agencies, boards, departments, and commissions to include more disaggregated options for Asian races to include: Korean, Tibetan, and Pakistani as well as more disaggregated options for Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander races to include: Samoan and Marshallese (Governor Hochul Signs Package of Legislation to Address Discrimination and Racial Injustice, 2021).

This has led to a number of researchers including “other” categories, allowing individuals to thus choose if they don’t feel they identify with one of the specific categories. Some researchers have also included the fill-in-the blank model in which respondents then check the “other” box and specify their self-identified race. These two options, although more inclusive to self-identification, can lead to additional data reporting issues, in which researchers are not able to aggregate the data due to too many variations in responses. This same concern can be applied in additional data collection categories as well, when the category options are limited and thus have the potential to exclude certain individuals.

3.2.8 Statistics on Native American and Latinx

According to a Bureau of Justice Statistics report in 1999, Native Americans were incarcerated at a rate that was 38% higher than the national average (Greenfield, 1999). More recent data suggest that in jails 9,700 American Indian/Alaskan Native people – or 401 per 100,000 population – were held in local jails across the country as of late June, 2018. That’s almost twice the jail incarceration rates of both white and Hispanic people (187 and 185 per 100,000, respectively) (Zen, 2018). In 19 states, they are more overrepresented in the prison population compared to any other race and ethnicity (Sakala, L., 2010). Between 2010 and 2015, the number of Native Americans incarcerated in federal prisons increased by 27% (Flanigan, 2015). In Alaska, data published by the 2010 US Census revealed that 38% of incarcerated people are American Indian or Alaskan Native despite the fact that they make up only 15% of the total population (Sakala, 2010). Native youth are highly impacted by the US prison system, despite accounting for 1% of the national youth population, 70% of youth taken into federal prison are Native American (Lakota People’s Law Project, 2015). Native American men are admitted to prison at four times the rate of white men, and Native American women are admitted at 6 times the rate of white women(Lakota People’s Law Project, 2015).

Latinos are incarcerated at a rate about 2 times higher than non-Latino whites and are considered one of the fastest-growing minority groups incarcerated (Kopf, Wagner, 2015).

3.2.9 Licenses and Attributions for Research Methods

“3.2 Research Methods” by Trudi Radtke and Megan Gonzalez is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 , except where otherwise noted.

“3.2.1. Survey Research Method” by Trudi Radtke and Megan Gonzalez is partially adapted from “ Overview of Survey Research ” by Paul C. Price, Rajiv Jhangiani, & I-Chant A. Chiang in Research Methods in Psychology – 2nd Canadian Edition , licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 .

“3.2.6. Impact on People’s Lives” by Trudi Radtke and Megan Gonzalez is partially adapted from “ 2.1 Why is Research Important – Introductory Psychology ” by Kathryn Dumper, William Jenkins, Arlene Lacombe, Marilyn Lovett, and Marion Perimutter in Introductory Psychology , licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 .

Introduction to the American Criminal Justice System Copyright © by Sam Arungwa. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

Criminal Justice

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 16 December 2023

- Cite this reference work entry

- Kelly Welch 3

42 Accesses

Introduction

Criminal justice can be conceptualized as an ideology, a system, and a process that aims to reduce crime by achieving certain objectives, such as deterrence, incapacitation, rehabilitation, restitution, and retribution. Criminal justice can have different meanings to different people, under different circumstances, within different cultures and societies globally. Generally speaking, criminal justice refers to the broad range of theories, laws, practices, and institutions that together seek to address the problem of crime in society. It is the delivery of an outcome, most frequently in the form of punishment, for those who have violated the law. But what exactly one believes that outcome should entail is entirely dependent on individual perspective and ideology, both of which are conditioned by historical, geographical, and experiential context as well as the circumstances of any given crime. Crime can be generally defined as an act that violates an established law. And...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Beccaria C (1764/1963) On crimes and punishments. Bobbs-Merrill, Indianapolis

Google Scholar

Bentham J (1823) An introduction to the principles of morals and legislation. Oxford University Press, New York

Death Penalty Information Center (n.d.) Costs: studies consistently find that the death penalty is more expensive than alternative punishments. Retrieved at https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/policy-issues/costs

Ellsworth PC, Ross L (1983) Public opinion and capital punishment: a close examination of the views of abolitionists and retentionists. Crime Delinq 29(1):116–169

Article Google Scholar

Foucault M (1977) Discipline and punish: the birth of the prison. Random House, New York

Latessa EJ, Johnson SL, Koetzle D (2020) What works (and doesn’t) in reducing recidivism. Routledge, Oxfordshire

Book Google Scholar

National Institute of Justice (2016) Five things about deterrence. Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice, Washington, DC

Oliver WM (2017) August Vollmer: the father of American policing. Carolina Academic Press, Durham

United States. President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice (1967) The challenge of crime in a free society: a report. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Sociology and Criminology, Villanova University, Villanova, PA, USA

Kelly Welch

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kelly Welch .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Regents Professor of the University, System of Maryland and Director of the University of Baltimore Center for International and Comparative Law, University of Baltimore School of Law, Baltimore, USA

Mortimer Sellers

Professor for Legal and Social Philosophy, Department of Legal Theory International and European Law, University of Salzburg, Salzburg, Austria

Stephan Kirste

Section Editor information

Philosophy Department, Villanova University, Villanova, PA, USA

Sally Scholz

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 Springer Science + Business Media B.V., Dordrecht.

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Welch, K. (2023). Criminal Justice. In: Sellers, M., Kirste, S. (eds) Encyclopedia of the Philosophy of Law and Social Philosophy. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6519-1_1038

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6519-1_1038

Published : 16 December 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN : 978-94-007-6518-4

Online ISBN : 978-94-007-6519-1

eBook Packages : Law and Criminology Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Last updated 27/06/24: Online ordering is currently unavailable due to technical issues. We apologise for any delays responding to customers while we resolve this. For further updates please visit our website: https://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/technical-incident

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > Law & Society Review

- > Volume 6 Issue 2: Special Issue on the Police

- > Research Models in Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice

Article contents

Research models in law enforcement and criminal justice.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 July 2024

A generation ago, one professor at Harvard Law School used to greet his students at the beginning of the semester with an offer to debate them on any subject so long as he was allowed to “state the question.” Any review of the crime, law enforcement, and criminal justice literature produced during the last ten years indicates that there is still as much disagreement over how the “relevant” questions should be stated as there is over the answers to these questions. Despite a strong public demand to “stop crime,” there is little consensus within the research community as to the questions (if any) which, if answered, would assist in the prevention of crime or the improvement of police, court, and correctional processes. Much of the literature “states the question” in terms of the narrowly defined “efficiency” of law enforcement and criminal justice agencies; a second group asks questions concerning the functions assigned to the criminal justice system; and a third set of critics are concerned with the implications of decisions made by the police, judges, and correctional officials for a democratic system of government. While I cannot attempt to review the literature which has been generated under these three models, I will describe each briefly and suggest some of the problems that have risen in research on law enforcement and criminal justice.

Access options

AUTHOR'S NOTE: The opinions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the position of the National Institute of Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice, the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration, or the United States Department of Justice.

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by Crossref .

- Google Scholar

View all Google Scholar citations for this article.

Save article to Kindle

To save this article to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

- Volume 6, Issue 2

- John A. Gardiner (a1)

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/3052853

Save article to Dropbox

To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save article to Google Drive

To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Reply to: Submit a response

- No HTML tags allowed - Web page URLs will display as text only - Lines and paragraphs break automatically - Attachments, images or tables are not permitted

Your details

Your email address will be used in order to notify you when your comment has been reviewed by the moderator and in case the author(s) of the article or the moderator need to contact you directly.

You have entered the maximum number of contributors

Conflicting interests.

Please list any fees and grants from, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in or any close relationship with, at any time over the preceding 36 months, any organisation whose interests may be affected by the publication of the response. Please also list any non-financial associations or interests (personal, professional, political, institutional, religious or other) that a reasonable reader would want to know about in relation to the submitted work. This pertains to all the authors of the piece, their spouses or partners.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Criminal Justice

IResearchNet

Academic Writing Services

Criminology research methods.

This section provides an overview of various research methods used in criminology and criminal justice. It covers a range of approaches from quantitative research methods such as crime classification systems, crime reports and statistics, citation and content analysis, crime mapping, and experimental criminology, to qualitative methods such as edge ethnography and fieldwork in criminology. Additionally, we explore two particular programs for monitoring drug abuse among arrestees, namely, the Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) and Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring (ADAM). Finally, the article highlights the importance of criminal justice program evaluation in shaping policy decisions. Overall, this overview demonstrates the significance of a multidisciplinary approach to criminology research, and the need to combine both qualitative and quantitative research methods to gain a comprehensive understanding of crime and its causes.

I. Introduction

• Brief overview of criminology research methods • Importance of understanding different research methods in criminology

II. Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) and Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring (ADAM)

• Definition and purpose of DAWN and ADAM • Methodology and data collection process • Significance of DAWN and ADAM data in criminology research

III. Crime Classification Systems: NCVS, NIBRS, and UCR

• Overview and purpose of each system • Differences between the systems • Advantages and limitations of each system

IV. Crime Reports and Statistics

• Sources of crime data and statistics • Limitations of crime data and statistics • Use of crime data and statistics in criminology research

V. Citation and Content Analysis

• Definition and purpose of citation and content analysis • Methodology and data collection process • Applications of citation and content analysis in criminology research

VI. Crime Mapping

• Definition and purpose of crime mapping • Methodology and data collection process • Applications of crime mapping in criminology research

VII. Edge Ethnography

• Definition and purpose of edge ethnography • Methodology and data collection process • Applications of edge ethnography in criminology research

VIII. Experimental Criminology

• Definition and purpose of experimental criminology • Methodology and data collection process • Applications of experimental criminology in criminology research

IX. Fieldwork in Criminology

• Definition and purpose of fieldwork in criminology • Methodology and data collection process • Applications of fieldwork in criminology research

X. Criminal Justice Program Evaluation

• Definition and purpose of criminal justice program evaluation • Methodology and data collection process • Applications of criminal justice program evaluation in criminology research

XI. Quantitative Criminology

• Definition and purpose of quantitative criminology • Methodology and data collection process • Applications of quantitative criminology in criminology research

XII. Conclusion

• Importance of understanding different research methods in criminology • Future directions for criminology research methods

Criminology research methods are crucial for understanding the causes and patterns of crime, as well as developing effective strategies for prevention and intervention. There are various methods used in criminological research, each with its own strengths and limitations. Understanding the different research methods is essential for conducting high-quality research that can inform policies and practices aimed at reducing crime and promoting public safety. This overview provides an overview of some of the most commonly used criminology research methods, including the Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) and Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring (ADAM), crime classification systems such as the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS), and Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR), crime reports and statistics, citation and content analysis, crime mapping, edge ethnography, experimental criminology, fieldwork in criminology, and quantitative criminology. The survey highlights the importance of understanding these methods and their applications in criminology research.

The Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) and Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring (ADAM) are two important research methods used in criminology to collect data on drug use and abuse among the population.

DAWN is a national public health surveillance system that tracks drug-related emergency department visits and deaths in the United States. The system collects data on drug-related medical emergencies and deaths from a variety of sources, including hospitals, medical examiners, and coroners. The purpose of DAWN is to provide information on drug use trends and the impact of drug use on public health and safety.

ADAM, on the other hand, is a research program that collects data on drug use and drug-related criminal activity among individuals who have been arrested and booked into jail. The program is designed to provide information on the prevalence of drug use and abuse among individuals involved in the criminal justice system.

Both DAWN and ADAM use similar methodology and data collection processes. Data is collected through interviews with individuals who have been involved in drug-related incidents, and through the analysis of drug-related data collected from medical and criminal justice records.

The significance of DAWN and ADAM data in criminology research is twofold. First, the data provides valuable information on drug use trends and patterns, which can inform the development of drug prevention and treatment programs. Second, the data can be used to understand the relationship between drug use and criminal behavior, and to inform criminal justice policies related to drug offenses.

Overall, the use of DAWN and ADAM in criminology research has contributed significantly to our understanding of drug use and abuse among the population, and has helped inform public health and criminal justice policies related to drug offenses.

The classification of crimes is an essential component of criminology research. The three main crime classification systems used in the United States are the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS), and the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program.

The NCVS is a victimization survey that collects data on the frequency and nature of crimes that are not reported to law enforcement. The survey is conducted by the Bureau of Justice Statistics and includes a sample of households and individuals. The NCVS provides valuable insights into crime victimization patterns and trends.

The NIBRS, on the other hand, is a more detailed crime reporting system that provides a comprehensive view of crime incidents. It captures more data than the UCR, including information on the victim, offender, and the circumstances surrounding the crime. The NIBRS is being adopted by law enforcement agencies across the country and is expected to replace the UCR as the primary crime reporting system.

The UCR is the longest-running and most widely used crime reporting system in the United States. It collects data on seven index crimes, including murder, rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, larceny-theft, and motor vehicle theft. The UCR provides an overview of crime trends and patterns at the national, state, and local levels.

Each system has its advantages and limitations. For example, the NCVS provides valuable information on crime victimization that is not captured by the UCR or NIBRS. The NIBRS provides more detailed information on crimes than the UCR but requires more resources to implement. The UCR is widely used and provides long-term trends but does not capture detailed information on each crime incident.

Understanding the differences and similarities between these classification systems is important for criminology research and policy development.

Crime reports and statistics are essential sources of data for criminology research. Law enforcement agencies, criminal justice systems, and government agencies collect and analyze crime data to develop policies and strategies to reduce crime rates. However, crime data and statistics have several limitations that researchers should consider when interpreting and using them in research.

One limitation of crime data and statistics is that they rely on the accuracy and completeness of reported crimes. Not all crimes are reported to law enforcement, and those that are reported may not be accurately recorded. Additionally, the police may have biases in their reporting practices, which can affect the accuracy of the data.

Another limitation of crime data and statistics is that they do not always provide a complete picture of crime. For example, crime data may not capture crimes that occur in private places or are committed by people who are not typically considered criminals, such as white-collar criminals.

Despite these limitations, crime data and statistics are still valuable sources of information for criminology research. They can help researchers identify patterns and trends in crime rates and understand the factors that contribute to criminal behavior. Crime data can also be used to evaluate the effectiveness of criminal justice policies and programs.

Researchers should be cautious when using crime data and statistics in their research and acknowledge the limitations of these sources. They should also consider using multiple sources of data to triangulate their findings and develop a more comprehensive understanding of crime trends and patterns.

Citation and content analysis are research methods that are increasingly used in criminology. Citation analysis involves the systematic examination of citations in published works to determine patterns of authorship, influence, and intellectual relationships within a given field. Content analysis, on the other hand, involves the systematic examination of written or visual material to identify patterns or themes in the content.

In criminology research, citation and content analysis can be used to study a wide range of topics, including the evolution of criminological theories, the impact of specific research studies, and the representation of crime and justice issues in the media. These methods can also be used to identify gaps in the literature and to develop new research questions.

The methodology for citation analysis involves gathering data on citations from published works, including books, articles, and other sources. This data is then analyzed to determine patterns in the citations, such as which works are cited most frequently and by whom. Content analysis involves the systematic examination of written or visual material, such as news articles or social media posts, to identify patterns or themes in the content. This process may involve coding the content based on specific categories or themes, or using machine learning algorithms to identify patterns in the data.

Citation and content analysis are important tools in criminology research because they provide a way to examine the influence of research and ideas over time, as well as the representation of crime and justice issues in the media. However, these methods also have limitations, such as the potential for bias in the selection of sources or the coding of content.

Overall, citation and content analysis are valuable research methods in criminology that can provide insights into the evolution of criminological theories, the impact of specific research studies, and the representation of crime and justice issues in the media.

Crime mapping is a criminology research method that visualizes the spatial distribution of crime incidents. Crime mapping involves the use of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and other digital mapping tools to display crime data. The purpose of crime mapping is to provide researchers and law enforcement agencies with a better understanding of the spatial patterns of criminal activity in a given area.

Methodology and data collection process for crime mapping involve the collection of crime data and the use of GIS software to display the data in a visual format. Crime data can be collected from a variety of sources, such as police reports, victim surveys, and self-report surveys. Once the data is collected, it is geocoded, or assigned a geographic location, using a global positioning system (GPS) or address information.

The applications of crime mapping in criminology research are numerous. Crime mapping can be used to identify crime hotspots, or areas with a high concentration of criminal activity, which can help law enforcement agencies allocate resources more effectively. Crime mapping can also be used to identify crime patterns and trends over time, which can help researchers and law enforcement agencies develop strategies to prevent crime. Additionally, crime mapping can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of crime prevention and intervention strategies.

In conclusion, crime mapping is a valuable criminology research method that can provide researchers and law enforcement agencies with important insights into the spatial patterns of criminal activity. By using GIS and other digital mapping tools, crime mapping can help researchers and law enforcement agencies develop effective crime prevention and intervention strategies.

Edge ethnography is a criminology research method that focuses on studying the behaviors and social interactions of people on the fringes of society. It is often used to explore deviant or criminal behaviors in subcultures and marginalized groups. Edge ethnography involves immersive fieldwork, where the researcher actively participates in the activities of the group being studied to gain a deeper understanding of their values, beliefs, and practices.

The data collection process in edge ethnography involves participant observation, in-depth interviews, and document analysis. The researcher spends a considerable amount of time in the field to gain the trust and respect of the group members and to observe their behaviors and social interactions in a naturalistic setting. The researcher may also collect artifacts, such as photos and videos, to provide additional insights into the group’s activities.

Edge ethnography has many applications in criminology research. It can be used to explore the social and cultural contexts of criminal behaviors, as well as the experiences of marginalized groups in the criminal justice system. It can also be used to identify emerging trends and subcultures that may be associated with criminal activities.

However, edge ethnography also has limitations. It can be time-consuming and resource-intensive, requiring the researcher to spend a considerable amount of time in the field. It may also raise ethical concerns, particularly if the researcher is studying criminal activities or subcultures that engage in illegal behaviors. Therefore, it is important for researchers to carefully consider the ethical implications of their research and to take steps to protect the privacy and safety of their subjects.

Experimental criminology refers to the use of scientific experimentation to test theories related to crime and deviance. The goal is to isolate the effects of specific factors on criminal behavior by manipulating one variable while holding others constant. Experimental criminology can involve lab experiments, field experiments, and quasi-experiments.

The methodology involves randomly assigning participants to different groups, manipulating the independent variable, and measuring the dependent variable. The data collected can be both quantitative and qualitative.

Experimental criminology has been used to test a variety of theories related to crime, including deterrence theory, social learning theory, and strain theory. It has also been used to evaluate the effectiveness of criminal justice interventions, such as drug treatment programs and community policing initiatives.

Despite the potential benefits of experimental criminology, there are limitations to its use. For example, it can be difficult to generalize the findings of a lab experiment to real-world situations, and ethical concerns may arise when manipulating variables related to criminal behavior. However, experimental criminology remains a valuable tool in the criminology research arsenal.

Fieldwork is an integral part of criminology research that involves researchers immersing themselves in the settings they are studying to gather firsthand information about the social and cultural dynamics of the phenomenon being studied. Fieldwork in criminology can be conducted through various methods such as participant observation, ethnography, case studies, and interviews.

The purpose of fieldwork in criminology is to gain a deeper understanding of the social and cultural factors that contribute to criminal behavior, victimization, and the criminal justice system. Fieldwork also provides insights into the lived experiences of those involved in the criminal justice system and how they perceive and experience law enforcement, punishment, and rehabilitation.