- How Do I Become a Clinical Trials Research Nurse?

Steps to Becoming a Clinical Trials Research Nurse - Education & Experience

For the 2023-2024 academic year, we have 112 schools in our MHAOnline.com database and those that advertise with us are labeled “sponsor”. When you click on a sponsoring school or program, or fill out a form to request information from a sponsoring school, we may earn a commission. View our advertising disclosure for more details.

Clinical research is the process of using science to better determine powerful and inventive means of detecting, diagnosing, treating, and preventing diseases and conditions. Clinical trials research nurses help outline trial criteria, write SOPs, evaluate research methods for efficacy, assist MDs or nurse practitioners with live procedures related to their studies, and deepen our collective medical understanding.

The international research community thrives on clinical research nursing. Research nurses are typically responsible for obtaining participants’ consent and recruiting, educating, and monitoring them. Additionally, these professionals report to the lead physician or NP and often coordinate the direct administration and evaluation of those treatments.

Some organizations use the term “clinical trials research nurse,” and others use the abbreviation “CRN.” Due to confusion concerning acronyms, most professional organizations use the former. Regardless of how you identify the position, no one can deny that as the Baby Boomers age, greater resources will be required to study the wide variety of medical problems that this generation faces.

Clinical research nurses maintain the quality, integrity, and honesty of clinical trials in both the public and private sectors, ensuring they comply with local, state, federal, and international regulations. They are often responsible for monitoring and checking in with study participants, completing test procedure paperwork, and structuring follow-up practices. These professionals develop and implement innovative solutions with numerous applications for the betterment of humankind and tackle some of our longest-running questions about human health. As students, prospective clinical trials research nurses study the components of nursing research, nursing theory, and how to evaluate the validity of the research properly.

Keep reading to learn how to become a clinical trials research nurse. Concentrating one’s studies on research nursing means joining the ranks of a small but significant quadrant of the research community.

Step-by-Step Guide to Becoming a Clinical Trials Research Nurse

Step 1 – graduate from high school.

Before graduating from high school, there are many ways that students can prepare for a career as a research nurse in clinical trials. It is recommended that to help prepare for coursework in clinical nursing and research, one should take a wide variety of courses in anatomy, physiology, mathematics, geometry, algebra, chemistry, physics, speech, and psychology. As admission to nursing programs is highly competitive, students are advised to pursue advanced placement coursework and set a goal of maintaining as high a grade point average as possible.

Another way to gain insight into the medical field is to intern at an extended care facility, nursing home, clinic, or teaching hospital. Volunteering, too, can be an excellent way to gain new perspectives on health, care, and nursing theory.

Step 2a – Graduate From an Accredited Nursing Program with an ADN (Two Years, Optional)

An associate’s degree in nursing (ADN) lays a clinical research and theoretical foundation for the work that one will undertake. Introductory coursework in anatomy, physiology, biology, nursing theory, and many more establish a skillset that blends the technical, technological, and medical.

Upon completion of two-year coursework, students will have received one of the following degrees: associate of nursing (AN), an associate of science in nursing (ASN), an associate degree in nursing (ADN), or an associate of applied science in nursing (AASN). Any of these degrees can prepare you to qualify for the NCLEX-RN exam.

Herzing University

The ASN program at Herzing University offers an accelerated, fast-paced course of study for those students wishing to achieve brisk entry into the industry. Students can complete this program in 20 to 24 months, depending on whether they have any transfer credits. General education courses are offered online, while core classes require on-campus attendance.

Made up of 70 to 73 credits, the program includes courses such as fundamentals of nursing; adult nursing systems; therapeutic use of self; pharmacology; nursing process and documentation; nursing management; mental health nursing; family nursing; and medical-surgical nursing.

- Location: Akron, OH; Birmingham, AL; Nashville, TN; Orlando, FL; Tampa, FL

- Accreditation: Higher Learning Commission (HLC)

- Expected Time to Completion: 20 to 24 months

- Estimated Tuition: $695 per credit

Step 2b – Graduate from a Nursing Program With a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (Four Years)

A BSN might be the best path for those interested in diving deeper into clinical trials research nursing. These courses of study build on the basics learned in an associate’s program, focusing on upper-level classes on research theory, nursing practice, and human resource management. At this stage, some aspiring CRNs seek concentrations focusing on clinical trials or research.

Schools such as the University of Michigan and the University of Washington boast top-notch BSN programs.

University of Michigan

The University of Michigan’s bachelor of science program in nursing provides students with a rigorous yet rewarding education filled with unique opportunities that will prepare them to become nurses and thrive as leaders in the field.

Comprising 128 credits, the program includes courses such as the culture of health; pathophysiology; reproductive health; behavioral health; health assessment; human anatomy and physiology; applied statistics; care of the family: infants, children, and adolescents; role transition; and leadership for professional practice.

- Location: Ann Arbor, MI

- Expected Time to Completion: Four years

- Estimated Tuition: Michigan resident ($1,046 to $1,133 per credit); non-resident ($2,654 to $2,815 per credit)

University of Washington

The University of Washington offers a bachelor of science in nursing (BSN) program preparing students for careers as registered nurses. Students in this program will learn from nationally acclaimed faculty members using interactive scenarios. They will learn to practice nursing skills in safe environments before performing them in supervised clinical settings.

Under the guidance of licensed care providers, students in this program will gain more than 1,000 hours of hands-on patient care experience. Students start in this program as college-level juniors after having already completed 60 semester-credits or 90 quarter-credits at the college level or a previous bachelor’s degree in a non-nursing field.

The curriculum includes courses such as foundational skills for professional nurses; foundations of professional nursing practice; foundations in pharmacotherapeutics and pathophysiology; fundamentals of nursing practice for illness care; health equity; healthcare systems and policy; ambulatory care; psychosocial nursing in health and illness; child health; and care coordination and case management.

- Location: Seattle, WA

- Accreditation: Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education (CCNE); Higher Learning Commission (HLC)

- Expected Time to Completion: Two years

- Estimated Tuition: Resident ($4,081 quarterly); non-resident ($13,580 quarterly)

Step 3a – Become Licensed as a Registered Nurse (Timeline Varies)

Each state requires that that state’s respective licensing channels must license those intending to become nurses. This directory collates data on how and where to obtain nursing licensing in all 50 states. Some states require a notarized personal statement or letter of intent with application paperwork.

The NCLEX-RN exam is the American testing standard for all registered nurses. After applying for the exam and offering proof of educational credentials, and meeting all state-specific criteria, nascent nurses must schedule an appointment to take the exam.

Administered by nursing professionals in closed exam rooms on isolated terminals, the exam uses machine learning to adapt its questions to the subject, specialization, and skill set. In some states, all of this work (including the exam) can be completed before a student’s official graduation date. This helps to expedite a nurse’s transition from student to practicing professional. Check state, institution, and employer policies before deciding on this approach.

Additionally, many certificates in clinical research, nursing science, and nursing research can be obtained online and added to one’s credential portfolio. For example, the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Nursing offers a certificate in nursing informatics .

Step 4 – Gain One Year of Clinical Trials Research Experience (One to Two Years, Optional)

Work experience in clinical trials can be critical to obtaining a clinical trials research nurse job. Many employers expect applicants to have already worked in this field. There are numerous ways to gain the necessary work experience, including working in administrative roles in trials, completing an internship, or working as a nursing assistant.

Step 5– Graduate from a Nursing Program with a Master of Science in Nursing (Two to Three Years, Preferred/Optional)

While much less common in customer and public care, advanced degrees in nursing are critical for those who wish to find a place in the leadership of clinical trials and research nursing .

Expanding on the foundations laid in a nursing BS program, an MS with a concentration in clinical research sciences often takes two or three years. Coursework covers clinical research theory, nursing theory, practicums in various healthcare and research environments, research development and coordination, clinical trial management, experiment design, and evidence-based practice, among other subjects. An MS in clinical research nursing positions students to transition into careers as research leads and assistants in pharmaceuticals, consumer products, clinical pathology, virology, oncology, and the study of infectious diseases.

Aside from nursing programs, there are also excellent master’s in clinical research degrees that nurses can complete to gain the necessary education to enter this field.

George Washington University

For example, George Washington University’s online MSHS in clinical and translational research is an excellent option for those looking to continue their education online. For a more traditional pathway, GW also hosts an on-campus clinical and translational research program that has been widely lauded.

The online MSHS program explores clinical administration, biomedical science, health policy, and community health. Graduates learn to develop best practices for bringing the latest medical science findings to the patients. This online program has no residency requirement.

The program’s 36-credit curriculum includes courses such as critical analysis of clinical research; clinical investigation; foundations in clinical and translational research; grantsmanship in translational health science; bioinformatics for genomics; biostatistics for clinical and translational research; and epidemiology translational research, among others.

- Location: Washington, DC

- Accreditation: Middle States Commission on Higher Education (MSCHE)

- Estimated Tuition: $1,315 per credit

Step 6 – Graduate with a Doctoral Degree in Nursing or a Clinical Research Discipline (Four to Seven Years, Optional)

There are two doctoral nursing degrees available, both of which are terminal, meaning that no further paths of education are available to those who hold these degrees. While a doctor of nursing practice (DNP) is a clinical practice degree intended for advanced nurse practitioners, a PhD in clinical research and trials nursing requires pursuing and studying an area of expertise that results in a doctoral dissertation and its defense.

Some advanced nursing programs will accept a BSN as a satisfactory degree when students apply for graduate school. However, the industry standard is to obtain an MSN before entering advanced postgraduate nursing studies. Always remember to contact an institution’s admissions office and check in to their criteria for application.

William Carey University

William Carey University offers a cutting-edge PhD in nursing science. This doctor of philosophy program in nursing education is a terminal degree that prepares DNP graduates to serve as nurse educators and nurse scholars. Except for four weekend meetings per year, this program can be completed entirely online and is a convenient option for full-time working students.

The curriculum includes courses such as role development for the nurse educator; curriculum development and program planning; instructional strategies and evaluation of student learning; creating an online educational environment; advanced curriculum assessment and evaluation; research development; advanced research methodology; and program evaluation.

Applicants to the program must hold a DNP from an accredited school of nursing, a GPA of 3.0, a current unencumbered nursing license, and submit three reference forms, among other requirements.

- Location: Hattiesburg, MS

- Accreditation: Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC)

- Estimated Tuition: $610 per trimester hour

Texas Woman’s University

Texas Woman’s University boasts two doctoral nursing programs: one in nursing science and one allowing students who have already obtained a DNP to extend their education and gain a clinical PhD. These programs can be completed either online at the Denton campus or in a hybrid format at the Houston campus.

In the nursing science PhD program, students receive the investigative aptitude, management skills, and advanced nursing knowledge needed to earn a spot at the healthcare leadership table, whether at hospitals, classrooms, or clinical settings. Admission requirements to this program include a current unencumbered U.S. RN license, a bachelor’s or master’s degree in nursing from a nationally accredited program, and a minimum GPA of 3.0.

The PhD in nursing science program requires completion of 60 credits beyond the master’s and includes courses such as philosophy of nursing science; ethical dimensions of nursing; exploring scientific literature; measurement and instrumentation in nursing research; qualitative nursing research; theory for nursing research and practice; quantitative nursing research; and determinants of health.

The DNP-to-PhD bridge program requires the completion of 42 credits. Applicants to this program must have a current unencumbered U.S. RN license, show evidence of graduation from a DNP program offered by a regionally-accredited university with national certification in nursing preferred, and have a minimum GPA of 3.5.

- Location: Denton, TX

- Expected Time to Completion: Two to four years

- Estimated Tuition: $7,140 per semester

University of Central Florida

For those seeking an online degree, the University of Central Florida offers a nursing PhD that has built a web-based curriculum around two on-campus intensives each year. This online PhD prepares graduates for careers at the forefront of nursing science, where they will be contributing to the body of knowledge and leading research in the application of innovative strategies for nursing education and clinical care.

The program requires the completion of 63 credits beyond the master’s degree. Those without an MSN degree should pursue the BSN-to-PhD in nursing program. The BSN-to-PhD program requires the completion of 72 credits beyond a bachelor’s degree.

- Location: Orlando, FL

- Expected Time to Completion: 11 to 15 semesters

- Estimated Tuition: In-state ($288.16 per credit); out-of-state ($1,073.31 per credit)

Step 7 – Obtain Certification Through the Association of Clinical Research Professionals (Timelines Vary, Optional)

Certification through the Association of Clinical Research Professionals (ACRP) demonstrates to employers that the candidate has achieved a high level of competency in clinical research education and training. Clinical trials research nurses can earn two primary certifications: a Certified Clinical Research Associate (CCRA) or a Certified Clinical Research Coordinator (CCRC).

The eligibility requirements for either certificate are the same. Candidates must have 3,000 hours of work experience in the six content areas of clinical research trials. A formal education program may substitute for up to 1,500 hours of work experience.

The content of the exams is similar and includes scientific concepts and research design, ethical and participant safety considerations, product development and regulation, clinical trial operations (GCPSs), study and site management, and data management and informatics. While the exam topics are similar, the CCRC exam is more in-depth and covers more advanced material than the CCRA.

Helpful Resources for Clinical Trials Research Nurses

Many valuable resources are available for prospective research nurses, from non-profits to representative organizations to job boards. Below are some of the most useful resources for those wishing to pursue a career pathway as a clinical trials research nurse:

- Association of Clinical Research Professionals

- Center for Information & Study on Clinical Research Participation

- Clinical Trial Resources (ASCO)

- Council for the Advancement of Nursing Science

- Global Research Nurses

- National Institute of Nursing Research

- NCLEX Registered Nurse Practice Test Questions

- Oncology Nursing Society’s FAQs

- Society of Clinical Research Associates

- Eastern Nursing Research Society (ENRS)

- The Midwest Nursing Research Society (MNRS)

- Southern Nursing Research Society (SNRS)

- The International Association of Clinical Research Nurses (IACRN)

Kimmy Gustafson

With a unique knack for simplifying complex health concepts, Kimmy Gustafson has become a trusted voice in the healthcare realm, especially on MHAOnline.com, where she has contributed insightful and informative content for prospective and current MHA students since 2019. She frequently interviews experts to provide insights on topics such as collaborative skills for healthcare administrators and sexism and gender-related prejudice in healthcare.

Kimmy has been a freelance writer for more than a decade, writing hundreds of articles on a wide variety of topics such as startups, nonprofits, healthcare, kiteboarding, the outdoors, and higher education. She is passionate about seeing the world and has traveled to over 27 countries. She holds a bachelor’s degree in journalism from the University of Oregon. When not working, she can be found outdoors, parenting, kiteboarding, or cooking.

Related Programs

- 1 Online MSN/MBA Dual Degree Programs – Nursing & Business

- 2 Online Master’s Degrees in Food Safety – Regulatory Affairs & Quality Assurance

- 3 Online Master’s in Clinical Nurse Leadership (CNL)

- 4 Online Master’s in Nurse Education (MSN Degree)

- 5 Online Master’s in Nurse Informatics (MSN Degree)

- 6 Online Master’s in Nursing Administration (MSN)

- 7 Online Master’s in Clinical Research Administration Programs

Related FAQs

- 1 Are There Online Nursing Administration Programs That Do Not Require the GRE?

- 2 Clinical Significance vs. Statistical Significance

- 3 How Do I Become a Nurse Administrator?

- 4 How Do You Become a Clinical Research Coordinator (CRC)?

- 5 What Can I Do With a Master’s Degree (MSN) in Nurse Administration?

- 6 What Can You Do with a Degree in Biotechnology?

- 7 What Can You Do with a Degree in Clinical Research Administration?

- 8 What is Clinical Data Management (CDM)?

- 9 What is Nursing Administration?

- 10 What is a Clinical Application Analyst and What Do They Do?

Related Posts

A day in the life of a clinical research associate.

The clinical research associate acts as a liaison between the study's sponsor (e.g., pharmaceutical company) and the clinics where the study takes place. Because results of a clinical trial must be kept entirely transparent and not influenced by the interests of the sponsor, this is a critical role.

Nurse Educator – A Day in the Life

Nurse educators are responsible for helping to train the next generation of nurses. They work in all nursing programs, from associate degrees to doctorates. The two primary places nurse educators work are in educational programs providing instruction and in clinical settings supervising nursing student clinical internships.

How to Get Started with Billing RPM and CCM Codes in a Clinical Practice: Part 1

This article aims to help give practice managers a framework for how to wrap their heads around the RPM/CCM code workflow, so they may better decide if it makes sense to take the next step and run a pilot program of their own.

A Guide to Successful Cancer Registry Virtual Management

Cancer registries are central to a successful organization's cancer program. From quality metrics tracking to regulatory agencies at the highest level, cancer registries perform essential reporting functions and provide crucial data to drive program decisions. As working remotely becomes more of the norm, organizations must be flexible to the needs of cancer registry professionals to work in a virtual environment.

Online MSN in Nursing Administration Programs Ranked by Affordability

Student loan debt has reached epic proportions and the cost of higher education is steadily rising. To help students find affordable programs we’ve outlined the top most affordable online MSN in nursing administration programs in 2021-2022.

- Department of Health and Human Services

- National Institutes of Health

Nursing at the NIH Clinical Center

Clinical research nurse roles.

Health Care Technician The Health Care Technician is a certified nursing assistant in the state of Maryland or has completed the Fundamentals of Nursing course work in a current accredited nursing program. This role supports the activities of the professional nurse by providing patient care functions to assigned patients while maintaining a safe environment.

Patient Care Technician The Patient Care Technician is a certified nursing assistant in the state of Maryland who supports the activities of the professional nurse by independently providing patient care functions to assigned patients while maintaining a safe environment.

Clinical Research Nurse I The Clinical Research Nurse (CRN) I has a nursing degree or diploma from a professional nursing program approved by the legally designated state accrediting agency. The CRN I is a newly graduated registered nurse with 6 months or less of clinical nursing experience. The incumbent functions under the direction of an experienced nurse to provide patient care, while using professional judgment and sound decision making.

Clinical Research Nurse II The CRN II has a nursing degree or diploma from a professional nursing program approved by the legally designated state accrediting agency and has practiced nursing at the NIH Clinical Center for at least 6 months. This nurse independently provides nursing care; identifies and communicates the impact of the research process on patient care; adjusts interventions based on findings; and reports issues/variances promptly to the research team. The CRN II administers research interventions; collects patient data according to protocol specifications; evaluates the patient response to therapy; and integrates evidence-based practice into nursing practice. The CRN II contributes to teams, workgroups and the nursing shared governance process. New skills and knowledge are acquired that are based on self-assessment, feedback from peers and supervisors, and changing clinical practice requirements.

Clinical Research Nurse III The CRN III has a nursing degree or diploma from a professional nursing program approved by the legally designated state accrediting agency at the time the program was completed by the applicant.

The CRN III has practiced nursing at the NIH Clinical Center for at least 1 year. The role spans the professional nursing development from “fully competent” to “expert” nursing practice. The CRN III provides care to acute and complex patient populations, and utilizes appropriate professional judgment and critical decision making in planning and providing care. S/he masters all nursing skills and associated technology for a particular Program of Care and assists in assessing the competency of less experienced nurses. The CRN III participates in the planning of new protocol implementation on the patient care unit; administers research interventions; collects patient data according to protocol specifications; evaluates the patient’ response to therapy; responds to variances in protocol implementation; reports variances to the research team; integrates evidence-based practice into nursing practice; and evaluates patient outcomes. The CRN III assumes the charge nurse and preceptor roles as assigned. Formal and informal feedback is provided by the CRN III to peers and colleagues in support of individual growth and improvement of the work environment.

Senior Clinical Research Nurse The Senior CRN has a nursing degree or diploma from a professional nursing program approved by the legally designated state accrediting agency at the time the program was completed by the applicant.

The Senior CRN serves as a leader in all aspects of nursing practice. S/he demonstrates expertise in the nursing process; professional judgment and decision making; planning and providing nursing care; and knowledge of the biomedical research process. The Senior CRN utilizes basic leadership principles and has an ongoing process of questioning and evaluating nursing practice.

The Senior CRN may have one of three foci:

Specialty Practice- as a clinical expert for a designated patient population or program of care Management- Clinical Manager The Senior CRN-Clinical Manager (CM) is an experienced staff nurse who collaborates with the Nurse Manager and other departmental leadership to assist with operations and management of a patient care area. The CM supervises the delivery of high quality patient care and assures the appropriate use of resources (i.e. staffing, rooms, etc.). The CM interacts with the research teams and support services to promote positive patient care outcomes and maintain protocol integrity. The CM models effective leadership, outstanding communication skills, while promoting a safe, supportive and professional environment. Education- Clinical Educator The Senior CRN-Clinical Educator (CE) is an experienced staff nurse who collaborates with the Nurse Manager and other departmental leadership to oversee educational needs of unit staff. The CE develops/coordinates/evaluates orientation for new unit staff, trains/mentors unit preceptors, serves as a liaison/resource for departmental/Clinical Center/professional educational opportunities, identifies educational needs, coordinates unit in-services, and plans unit educational days. The CE designs, implements and evaluates learning experiences for all staff levels to acquire, maintain, or increase their knowledge and competence. The Clinical Educator teaches at the unit and departmental level.

Nurse Manager The Nurse Manager has 3 to 5 years of recent management experience; advanced preparation (Masters Degree) is preferred. The Nurse Manager has experience in change management, creative leadership and program development; an demonstrates strong communication and collaboration skills to foster an effective partnership with institute personnel.. The Nurse Manager demonstrates a high level of knowledge in a particular specialty practice area and utilizes advanced leadership skills to meet organization goals.

Nurse Educators Nurse Educators play a critical role in preparing staff for an ever-changing clinical research environment. The roles and responsibilities of Nurse Educators are based on the Association for Nursing Professional Development (ANPD) Scope and Standards, and includes: onboarding/orientation, competency management, education, collaborative practice, role development, and inquiry. Nurse Educators function as educators, facilitators, change agents, consultants, researchers, and leaders in the organization.

Clinical Nurse Specialist The Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS) has a Masters or Doctorate Degree in Nursing from a state-approved school of nursing accredited by either the National League for Nursing Accrediting Commission (NLNAC) or the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education (CCNE) with a major in the clinical nursing specialty to which the nurse is assigned. The CNS has a minimum of 5 years experience, is certified in a specialty area, and is accountable for a specific patient population within a specialized program of care.

Nurse Consultant The Nurse Consultant serves as an expert advisor and program manager for a specific area of clinical administration or clinical practice management. The incumbent serves as liaison to Clinical Center departments and the ICs for issues related area of expertise and assigned responsibility and to provide communication and consultative services to all credentialed nurses at the Clinical Center.

Nurse Scientist The Nurse Scientist is a nurse with advanced preparation (PhD in nursing or related field) in research principles and methodology, who also has expert content knowledge in a specific clinical area. The primary focus of the role is to (1) provide leadership in the development, coordination and management of clinical research studies; (2) provide mentorship for nurses in research; (3) lead evaluation activities that improve outcomes for patients participating in research studies at the Clinical Center; and (4) contribute to the overall health sciences literature. The incumbent is expected to develop a portfolio of independent research that provides the vehicle for achieving these primary objectives.

Program Director The Program Director serves as the supervisor of a group of expert advisors for a specific area of nursing expertise (education, recruitment and outreach, safety and quality, staffing and workforce planning). The incumbent coordinates, implements, and oversees all the operations of the program they oversee. They serve as the liaison to other Clinical Center departments and the ICs for issues related area of expertise and assigned responsibility and to provide communication and consultative services to all credentialed nurses at the Clinical Center.

NOTE: PDF documents require the free Adobe Reader .

This page last updated on 05/15/2024

You are now leaving the NIH Clinical Center website.

This external link is provided for your convenience to offer additional information. The NIH Clinical Center is not responsible for the availability, content or accuracy of this external site.

The NIH Clinical Center does not endorse, authorize or guarantee the sponsors, information, products or services described or offered at this external site. You will be subject to the destination site’s privacy policy if you follow this link.

More information about the NIH Clinical Center Privacy and Disclaimer policy is available at https://www.cc.nih.gov/disclaimers.html

Home / Nursing Careers & Specialties / Research Nurse

Research Nurse

What does a research nurse do, becoming a research nurse, where do research nurses work, research nurse salary & employment, helpful organizations, societies, and agencies.

What Is a Research Nurse?

Research nurses conduct scientific research into various aspects of health, including illnesses, treatment plans, pharmaceuticals and healthcare methods, with the ultimate goals of improving healthcare services and patient outcomes. Also known as nurse researchers, research nurses design and implement scientific studies, analyze data and report their findings to other nurses, doctors and medical researchers. A career path that requires an advanced degree and additional training in research methodology and tools, research nurses play a critical role in developing new, potentially life-saving medical treatments and practices.

A highly specialized career path, becoming a nurse researcher requires an advanced degree and training in informatics and research methodology and tools. Often, research nurses enter the field as research assistants or clinical research coordinators. The first step for these individuals, or for any aspiring advanced practice nurse, is to earn a Bachelor of Science in Nursing degree and pass the NCLEX-RN exam. Once a nurse has completed their degree and attained an RN license, the next step in becoming a research nurse is to complete a Master's of Science in Nursing program with a focus on research and writing. MSN-level courses best prepare nurses for a career in research, and usually include coursework in statistics, research for evidence-based practice, design and coordination of clinical trials, and advanced research methodology.

A typical job posting for a research nurse position would likely include the following qualifications, among others specific to the type of employer and location:

- MSN degree and valid RN license

- Experience conducting clinical research, including enrolling patients in research studies, implementing research protocol and presenting findings

- Excellent attention to detail required in collecting and analyzing data

- Strong written and verbal communication skills for interacting with patients and reporting research findings

- Experience in grant writing a plus

To search and apply for current nurse researcher positions, visit our job boards .

What Are the Education Requirements for Research Nurses?

The majority of nurse researchers have an advanced nursing degree, usually an MSN and occasionally a PhD in Nursing . In addition to earning an RN license, research nurses need to obtain specialized training in informatics, data collection, scientific research and research equipment as well as experience writing grant proposals, research reports and scholarly articles. Earning a PhD is optional for most positions as a research nurse, but might be required to conduct certain types of research.

Are Any Certifications or Credentials Needed?

Aside from a higher nursing degree, such as an MSN or PhD in Nursing, and an active RN license, additional certifications are often not required for work as a research nurse. However, some nurse researcher positions prefer candidates who have earned the Certified Clinical Research Professional (CCRP) certification offered by the Society for Clinical Research Associates . In order to be eligible for this certification, candidates must have a minimum of two years' experience working in clinical research. The Association of Clinical Research Professionals also offers several certifications in clinical research, including the Clinical Research Associate Certification, the Clinical Research Coordinator Certification and the Association of Clinical Research Professionals – Certified Professional Credential. These certifications have varying eligibility requirements but generally include a number of hours of professional experience in clinical research and an active RN license.

Nurse researchers work in a variety of settings, including:

- Medical research organizations

- Research laboratories

- Universities

- Pharmaceutical companies

A research nurse studies various aspects of the healthcare industry with the ultimate goal of improving patient outcomes. Nurse researchers have specialized knowledge of informatics, scientific research and data collection and analysis, in addition to their standard nursing training and RN license. Nurse researchers often design their own studies, secure funding, implement their research and collect and analyze their findings. They may also assist in the recruitment of study participants and provide direct patient care for participants while conducting their research. Once a research project has been completed, nurse researchers report their findings to other nurses, doctors and medical researchers through written articles, research reports and/or industry speaking opportunities.

What Are the Roles and Duties of a Research Nurse?

- Design and implement research studies

- Observe patient care of treatment or procedures, and collect and analyze data, including managing databases

- Report findings of research, which may include presenting findings at industry conferences, meetings and other speaking engagements

- Write grant applications to secure funding for studies

- Write articles and research reports in nursing or medical professional journals or other publications

- Assist in the recruitment of participants for studies and provide direct patient care for participants

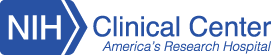

The Society of Clinical Research Associates reported a median salary for research nurses of $72,009 in their SoCRA 2015 Salary Survey , one of the highest-paying nursing specializations in the field. Salary levels for nurse researchers can vary based on the type of employer, geographic location and the nurse's education and experience level. Healthcare research is a growing field, so the career outlook is bright for RNs interested in pursuing an advanced degree and a career in research.

- National Institute of Nursing Research

- Council for the Advancement of Nursing Science

- International Association of Clinical Research Nurses

- Nurse Researcher Magazine

Related Articles

- 4 Short-Length Online and On-Campus BSN Programs to Enroll in for 2024-2025

- 10 Mistakes to Avoid When Selecting an MSN Program

- RN to BSN vs. Direct-Entry BSN: Which is Best For You?

- 10 Short-Length MSN Programs to Enroll in for 2024-2025

- Pros and Cons of the Direct-Entry MSN Program

- Do BSN-Educated Nurses Provide Better Patient Care?

- See all Nursing Articles

- Penn Medicine Biobank (PMBB)

- Center for Human Phenomic Science (CHPS)

- Investigational Drug Service (IDS)

- Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Research Design (BERD)

- Incentive Based Translational Science (IBTS)

- Program in Comparative Animal Biology (PICAB)

- Program in Research Ethics (PRE)

- Center for BioMedical Informatics Core (BMIC)

- Personalized Medicine In Translation (PERMIT)

- Translational Bio-Imaging Center (TBIC)

- Center for Targeted Therapeutics and Translational Nanomedicine (CT 3 N)

- Community Engagement and Research (CEAR)

- Engineered mRNA and Targeted Nanomedicine Core

- Neurobehavior Testing Core

- Study Design and Biostatistics

- Translational Core Laboratories (TCL)

- Research Facilitator

- Funding Opportunities

- Education & Training

- Internal Advisory Committee

- External Advisory Committee

- CTSA Leadership

- Citing the CTSA

- CTSA Oversight

- CTSA Partners

- Hub Response to COVID

- Clinical Research

- Education Overview

- Education & Training Programs

- Clinical Research Professionals

Clinical Research Nursing Certificate

Review the online info session here .

The Institute for Translational Medicine and Therapeutics (ITMAT) Education program offers an online Clinical Research Nursing Certificate. Through a combination of didactic content, highly interactive and engaging learning experiences, and collaboration with other CRNs, the certificate program will prepare nurses to navigate the growing complexities of the clinical research landscape as well as improve the safety, quality, and experience of research participants.

Bridging the gap between clinical care and research operations is an important and timely area of focus for both academic medical centers and study sponsors. The oversight of participants on high risk and early phase research protocols requires expert clinical oversight and coordination of care, and knowledge and experience in research execution. Graduates will have a foundational knowledge of the domains of clinical research nursing including human subjects protection, care coordination and continuity, contribution to science, and study management.

Graduates will:

- Understand care coordination and its application to the research process and the management of research participants

- Utilize quality improvement skills to support participants on clinical research studies

- Integrate new clinical research knowledge and clinical nursing skills

- Apply regulations, processes, and management of human subject research, focusing on the unique nursing contributions to clinical trials of drugs and devices

- Learn skills and tools required to effectively execute clinical research protocols in various patient populations and settings

Applications are currently being accepted to enroll in Fall 2024. The deadline to apply is June 30, 2024.

Contact Amanda Brock, Program Director, with any questions: [email protected]

Program Information

The certificate includes 4 courses and is designed to take 1.5 years.

Clinical Research Nursing Certificate Study Plan

4 Credit Units (CUs)

Please review the Regulatory Affairs Tuition webpage for details.

Applications are currently being accepted for Fall 2024. The deadline to apply is June 30, 2024.

Certificate Eligibility

- Applicants must be licensed nurses with at least 18 months of clinical experience

- An active RN license in any U.S. state

What We're Looking For

- BSN or a bachelor's in any related field preferred

- Existing experience in patient care and clinical expertise

- Strong critical thinking skills and clinical judgment

Application Process

Applicants must submit a full application via the online form in CollegeNET.

Please note, select "Regulatory Affairs Certificate" under Program Information as the program of study in CollegeNet. Based on your personal statement response, we will administratively shift your application to the Clinical Research Nursing Certificate.

Apply Online Now

The application form requires the following documents:

- Upload unofficial undergraduate and graduate, if applicable, transcripts into the application system

- Upon acceptance, candidates will need to provide official transcripts before beginning classes

- What are your short- and long-term professional goals, and how does the Certificate in Clinical Research Nursing help you meet your goals?

- Discuss a challenge, setback, or failure that you have faced in your nursing career. How did it affect you, and what did you learn from the experience?

- Recommender may be faculty or an employer

- The suitability of the Clinical Research Nursing Certificate for the student's stated career goals

- The student's academic ability

- English Language Proficiency (e.g. TOEFL score) for applicants whose bachelor's institution did not conduct courses in English.

The application does not require GRE score submission.

Application Fee: $25

After acceptance, applicants will need to provide proof of RN license and official transcripts.

Application Support

We encourage you to reach out to discuss your interests in the certificate program and answer any questions. Contact Program Director, Amanda Brock, [email protected].

Please review our Student Resources page .

Policies & Disclosures

The University of Pennsylvania values diversity and seeks talented students, faculty and staff from diverse backgrounds. The University of Pennsylvania does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, religion, creed, national or ethnic origin, citizenship status, age, disability, veteran status or any other legally protected class status in the administration of its admissions, financial aid, educational or athletic programs, or other University-administered programs or in its employment practices. Questions or complaints regarding this policy should be directed to the Executive Director of the Office of Affirmative Action and Equal Opportunity Programs, Sansom Place East, 3600 Chestnut Street, Suite 228, Philadelphia, PA 19104-6106; or 215-898-6993 (Voice) or 215-898-7803 (TDD). Specific questions concerning the accommodation of students with disabilities should be directed to the Office of Student Disabilities Services located at the Learning Resources Center, 3820 Locust Walk, Harnwell College House, Suite 110, 215-573-9235 (voice) or 215-746-6320 (TDD).

The federal Jeanne Clery Disclosure of Campus Security Policy and Campus Crime Statistics Act, as amended, requires colleges and universities to provide information related to security policies and procedures and specific statistics for criminal incidents, arrests, and disciplinary referrals to students and employees, and to make the information and statistics available to prospective students and employees upon request. The Campus SaVE Act of 2013 expanded these requirements to include information on and resources related to crimes of interpersonal violence, including dating violence, domestic violence, stalking and sexual assault. Federal law also requires institutions with on-campus housing to share an annual fire report with the campus community.

In addition, the Uniform Crime Reporting Act requires Pennsylvania colleges and universities to provide information related to security policies and procedures to students, employees and applicants; to provide certain crime statistics to students and employees; and to make those statistics available to applicants and prospective employees upon request.

To review the University’s most recent annual report containing this information, please visit the Annual Security and Fire Safety Report or the Penn Almanac Crime Reports .

You may request a paper copy of the report by calling the Office of the Vice President for Public Safety and Superintendent of Penn Police at 215-898-7515 or by emailing [email protected] .

Recognizing the challenges of teaching, learning, and assessing academic performance during the global COVID-19 pandemic, Penn’s admissions committees for graduate and professional programs will take the significant disruptions of the COVID-19 outbreak in 2020 into account when reviewing students’ transcripts and other admissions materials as part of their regular practice of performing individualized, holistic reviews of each applicant. In particular, as we review applications now and in the future, we will respect decisions regarding the adoption of Pass/Fail and other grading options during the period of COVID-19 disruptions. An applicant will not be adversely affected in the admissions process if their academic institution implemented a mandatory pass/fail (or similar) system for the term or if the applicant chose to participate in an optional pass/fail (or similar) system for the term. Penn’s longstanding commitment remains to admit graduate and professional student cohorts composed of outstanding individuals who demonstrate the resilience and aptitude to succeed in their academic pursuits.

Please review the University of Pennsylvania required disclosures .

The University of Pennsylvania is accredited, but there is no separate accreditation for clinical research nursing programs.

The Clinical Research Nursing Certificate program does not currently accept students based outside of the U.S.

Clinical Research Nursing

This Clinical Research Nurse (CRN) program will prepare graduate-level nurses as Clinical Research Nurses, who will improve the conduct of clinical research and ultimately the quality of life for individuals, families, and communities. Research participants’ care and the research process are closely related and balancing these two goals is imperative for high-quality research and nursing care. As the number of clinical trials in the U.S. has increased, the demand for CRNs has also increased.

- Consistent with the American Nurses Association and the International Association of Clinical Research Nurses the scope and standards of practice for clinical research nursing.

- Meets the graduate level scope and standards of Clinical Research Nursing of the ANA and IACRN

- CRNs care for a wide range of participants (healthy to acutely ill) and across settings and specialties.

- Nurses can complete the program in one year full-time or two years part-time

- To provide transdisciplinary education by educating students with other health professionals

- To provide CRNs with high-level clinical skills, critical thinking skills, and, at the same time cognizance of the regulatory, ethical, and scientific issues of the clinical research environment.

- To educate nurses to meet the dual accountabilities of nursing practice and research nursing.

Practicum opportunities

Practicum opportunities are available at major medical centers in the New York City area, such as NYU Langone Health, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, and Rockefeller University.

Program outcomes

- Graduates are prepared to work in teams as research nurses in organizations that conduct clinical research such as universities, academic medical centers, and the pharmaceutical industry.

- Graduates are prepared to administer research interventions, collect patient data according to protocol, evaluate patients’ responses to therapy and integrate evidence-based practice into nursing practice, and evaluate patient outcomes.

- With the increase in clinical research around the world and as the number of clinical trials in the U.S. has increased, there is a strong demand for nurses with these skills.

This program is not a replacement for PhD programs that prepare nurse scientists but provides the foundation for future enrollment in a PhD program.

Clinical Research Training For Nurses: A Guide to Becoming a Clinical Research Nurse

Clinical research training for nurses, guide to becoming a clinical research nurse, what is clinical nursing research.

Nurses are known for providing direct care for patients. However, nurses may take up roles that are completely new to them within the world of clinical research. These roles include clinical research coordinator , educator and manager. They can also take up less traditional role like regulatory specialist, study monitor and IRB (institutional board review) admin.

Regulatory specialist: their activities relate mainly with preparing regulatory documents and communicating with regulatory bodies. Nurses can work as a regulatory affairs specialist, a regulatory operation coordinator, or a regulatory coordinator . They can work within government agencies, pharmaceutical companies, academic medical centers.

Study monitor: they monitor clinical research practices and make sure that it complies with necessary research protocols and regulations. They tend work at government agencies, biotechnology companies, pharmaceutical companies, contract research organizations, device manufacturers etc. Aspiring study monitors can enhance their qualifications with a Pharmacovigilance Certification .

Institutional Review Board (IRB) administrator: they are the professionals in charge of overseeing, administrating, implementing and managing IRB activities, like policies and procedures that relates to protecting human welfare. They can work at all IRBs: local, commercial or central IRB.

Nurses that have developed interest in the field of clinical research can join professional organizations. This provides them with the opportunity to network and continue their education through mediums like conferences, webinars, discussion groups, publications and online resources. These avenues serve as part of their clinical research training .

Certification is often a parameter used to measure professional expertise. This is based on criterion that reflects skill, knowledge, educational preparation, ability, and competence that are developed from experience in that area of specialization. Nurses that developed an interest in clinical research and have taken a clinical research training program have an opportunity to be certified through the:

Society for Clinical Research Professionals, Inc. (Certified Clinical Research Professionals)

Association for Clinical Research Professionals (Certified Clinical Research Associate or Certified Clinical Research Coordinator)

This field of clinical research gives nurses a chance, an opportunity to advance themselves professionally in a field that might not have been explored by them before. The benefits of having a registered nurse cover letter are insurmountable. This also provides a career path that can show family members the benefits of working in the medical field.

Nurses that have gone through the clinical research for nurses , otherwise called research nurse can carry out research on the various aspects of the human health, such as illness, pharmaceutical and health care methods and treatment plans. The main aim of this research is to improve the quality of health care service delivery. Helping patients and their family in a healthcare facility also brings a level of joy that is hard to find in many other career paths.

Roles of Research Nurses

They are responsible for designing and implementing research studies.

They observe procedures for treatment, collect and analyze data.

They report their research results to appropriate quarters.

They write articles and report their research findings in nursing or medical professional publications and journals.

They help in recruiting participants for studies and are involved in providing direct care for the participants.

Clinical research nurse salary can make use of their communication skills as well as their critical thinking skills gotten from their knowledge and experience in healthcare to further their career in this exciting way.

Know that future CRNs can speak to our 24/7 chat and phone advisors to request information on partial scholarships and payment plans for nurses.

2. Clinical Research Nurse Salary

The average pay for a Clinical Research Nurse is $31.28 per hour.

MD Anderson Cancer Center Clinical Research Nurse salaries - $71,503/yr

Northwestern University Clinical Research Nurse salaries - $75,005/yr

NIH Clinical Research Nurse salaries - $77,331/yr

CLINICAL RESEARCH NURSE JOB Description

A clinical research nurse conducts scientific research on different aspects of human health like illnesses, pharmaceuticals, treatment plans and healthcare methods. Their major goal is to improve the quality of healthcare services that are administered to the patients.

Source: Payscale

3. How do I get Clinical Research Nurse Experience?

Experience don’t just jump on you, you have to get it by practice. CCRPS affords you an opportunity to acquire knowledge in clinical research , and not just knowledge but experience as well. Registering for the appropriate course will boost your knowledge base and as well you get experience of clinical research first hand.

As a clinical research nurse, you will be at the forefront of new medical discoveries, and help develop breakthrough cures and medical treatments. The work that you do during your career can help some patients live longer or better quality of life. You may be responsible for studying diseases and disorders, as well as developing new treatment plans. You will also help test new treatments and medications that could possibly change the way a disease or disorder is perceived.

The field of clinical research can be very rewarding and fulfilling. A good research nurse is dedicated to their work and ready to take on everything that the profession throws their way. If you’re looking to pursue a research nursing career, you should have an excellent understanding of the research process as well as the specialty area that you’re studying.

Excellent communication skills are also a must. You must be able to effectively communicate with scientists, physicians, researchers, patients, and corporate executives.

4. What Does a Clinical Research Nurse Do?

The duties of a research nurse will typically depend on their employer and role. Some research nurses may be responsible for studying diseases, while others may help create and improve new medications and other treatments.

clinical research nursing scope and Standards of Practice

Clinical research nurses can take up clinical research jobs in institutions like research organizations, pharmaceutical companies, universities, research laboratories, government agencies and teaching hospitals.

The work that a research nurse does is quite exhaustive and it includes;

They use their knowledge of the basics of clinical research in designing and implementation of research studies.

Observation of the procedures for patient treatment, collection and analyzing of data.

They report their research findings to the relevant authorities. They may also have to present their results at health conferences and publish them in journals.

They write grant applications in order to secure funds to carry out the research.

They render assistance in the process of recruiting study subjects.

They provide direct treatment for research participants.

Research nurses that study diseases and illnesses will often perform a great deal of research, both by studying previous findings and observing patients. They may be required to examine medical journals, for instance, as well as observe, study, and care for patients suffering from a particular disease.

They make decisions based on the observations made as to which patients are the best candidates for certain clinical trials. During clinical trials , the research nurse will administer medications or perform other treatment procedures, During this process, research nurses must closely monitor each patient’s progress. This includes documenting side effects, drug interactions, and the overall efficiency of the medication.

Aside from caring for patients, documenting and recording information during clinical trials are the most important responsibility that a research nurse has. The information and data gathered during the research must be compiled into reports and handed over to senior clinical researchers or specialists.

5. How Do I Become a Research Nurse?

Don’t expect to become a research nurse overnight. It's a lot of work and you are expected to undergo years of training and experience.

The clinical research nurse job is a competitive one and certificates are not just handed out to anybody. The conditions to be eligible to take the certificate exam is that you must be an experienced registered nurse and your experience must include having thousands of hours of experience in the area of clinical research.

How to Become a Registered Nurse (RN) in 2020 that contains everything a person pursuing a nursing job should know - responsibilities, education, salaries and more.

The first step toward becoming a research nurse is to obtain a proper education. You can start with a bachelor’s degree in nursing, although many employers prefer that their research nurses have master’s degrees or even doctoral degrees in their chosen specialty. During your schooling, classes in research and statistics are a must and are courses in your chosen area of expertise.

According to clinical research job websites , many research nurses have a MSN degree and some have a PhD in nursing. Many of them attain these degrees of education in order to give them an edge on getting clinical research positions . While studying, courses in statistics and research are mandatory.

There are two main certifications that clinical research nurses can get from the Association of Clinical Research Professionals (ACRP). You can get certification to become a certified clinical research associate or you can choose to become a certified clinical research coordinator.

Take courses from CCRPS and learn more on how to become a clinical research nurse.

Discover more from Clinical Research Training | Certified Clinical Research Professionals Course

6. Clinical Research Nurse Requirements and Certifications & Nursing Cover Letter

A bachelor's degree in nursing does meet licensure requirements for graduates to become registered nurses (RNs), which qualifies individuals for the specialized certification. Bridge programs, such as an RN-to-Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN), require previous nursing education for admission. Nursing students complete traditional classroom courses, laboratory experiences, and a clinical practicum in a medical setting, which includes a hospital, assisted living facility, and long term care center.

For specific education in clinical research , trained RNs enroll in graduate certificate and degree programs. There students are introduced to case studies, ethical research practices, and financial matters affecting the design, implementation, and funding of clinical research trials. In a master's program, studies in research ethics point students towards ethical research practices, including a discussion on human rights, misconduct, and conflicts of interest. Graduate programs will also include quantitative research and a capstone project.

All RN-to-BSN programs will require an RN license to enroll. Master's and graduate certificates will need a bachelor's degree with sufficient prerequisite coursework in the field. In addition, they will need letters of recommendation or reference, a personal statement, and GRE scores.

Becoming a nurse researcher which is a highly specialized career requires an advanced degree and training in informatics and research methodology and tools. The initial step for these individuals, or for any aspiring advanced practice nurse, is to earn a Bachelor of Science in Nursing degree and pass the NCLEX-RN exam. Once a nurse has completed their degree and attained an RN license, the next step is to complete a Master's of Science (MSN) in Nursing program with a focus on research and writing. MSN courses prepare nurses for a career in research and usually include coursework in statistics, research for evidence-based practice, design and coordination of clinical trials , and advanced research methodology.

A TYPICAL JOB POSTING FOR A RESEARCH NURSE POSITION WOULD LIKELY INCLUDE THE FOLLOWING QUALIFICATIONS, AMONG OTHERS SPECIFIC TO THE TYPE OF EMPLOYER AND LOCATION:

MSN degree and valid RN license.

Experience conducting clinical research, including enrolling patients in research studies, Implementing research protocol and presenting findings.

Excellent attention to detail required in collecting and analyzing data.

Strong written and verbal communication skills for interacting with patients and reporting research findings.

For a person to practice nursing legally, acquiring of nursing credentials and certifications is very important. For instance, some nurses who achieve a master's degree (MSN) leave the patient care aspect of nursing, and practice in a more managerial role.

CRA JOB OPPORTUNITIES

If you choose to become a Clinical Research Associate (CRA), you will have a key role in the success of clinical trials. Most CRAs have a nursing background, like yours. You will be the primary contact and support for trial sites, ensuring that the study is conducted according to the protocol, ICH-GCP, regulatory requirements and standard operating procedures (SOPs).

The Clinical Research Associates also offers you the unique opportunity to have an exciting career in the research of drug and medical device development while making a difference in the lives of those around them.

Take courses from CCRPS and learn more on how to become a clinical research professional.

Speak to our 24/7 chat and phone advisors to request information on partial scholarships and payment plans for nurses.

About CCRPS

How much is a clinical research coordinator’s salary.

- About IACRN

- IACRN Board of Directors

- Distinguished CRN Award

- Chapter Governance Committee

- Conference Planning Committee

- Education Committee

- Membership, Marketing & Communications Committee

- IACRN Recommendations on DCT Guidance

- Join a Committee

- IACRN Leadership Program

- Research Projects

- Institutional Membership

- Membership Campaign

- Member Publications

- Publications

- CRN Certification by Portfolio

- 2024 Conference

- Calendar of Events

- 2023 Conference

- 2022 Conference

- Past Events

- Clinical Trials Day

- Post a Position

- Available Positions

Clinical Research Nursing

The specialized practice of professional nursing focused on maintaining equilibrium between care of the research participant and fidelity to the research protocol. This specialty practice incorporates human subject protection; care coordination and continuity; contribution to clinical science; clinical practice; and study management throughout a variety of professional roles, practice settings, and clinical specialties.

Please cite International Association of Clinical Research Nurses. (2012) "Enhancing Clinical Research Quality and Safety Through Specialized Nursing Practice". Scope and Standards of Practice Committee Report.

Clinical Research Nurse

- Madison, Wisconsin

- SCHOOL OF MEDICINE AND PUBLIC HEALTH/CARBONE COMP CANCER CENTER

- Health and Wellness Services

- Partially Remote

- Staff-Full Time

- Staff-Part Time

- Opening at: Apr 26 2024 at 14:25 CDT

- Closing at: May 30 2024 at 23:55 CDT

Job Summary:

The Clinical Research Nurse will join the Clinical Research Central Office (CRCO) at the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center (UWCCC) to coordinate cancer clinical research within one or more Disease-Oriented Teams. The primary duties of this job involve the management of subjects enrolled in clinical research studies at the UW Carbone Cancer Center. This position will report to the Clinical Team Manager and work under the general direction of the Principal Investigator of each research study. This position has the ability to work remotely 1 day/week and does not include any nights or weekends. Prefer full time FTE, but will consider down to 0.8 FTE for the right candidate. The Clinical Research Nurse must have a high degree of clinical expertise with a specific focus on the treatment of patients with anticancer agents and a specialized nursing competence in the field of Oncology Research.

Responsibilities:

- 10% Secures and schedules logistics for clinical research projects according to the research plan

- 10% Assists in the recruitment and screening of subjects for clinical studies by conducting physical health assessments

- 10% Provides professional nursing care to patients according to established protocols

- 15% Provides appropriate treatment plan direction and information to study participants

- 20% Serves as main point of contact and liaison to project participants, investigators, research sponsors, and the research team delivering study information in accordance with established research project standards and protocols

- 10% Collects, verifies, and enters data into database and analyzes clinical information data

- 15% Serves a primary point of contact for emergent study participant situations related to adverse effects or complications of the study

- 10% May provide expertise, training, and guidance to the community, peers, and/or students

Institutional Statement on Diversity:

Diversity is a source of strength, creativity, and innovation for UW-Madison. We value the contributions of each person and respect the profound ways their identity, culture, background, experience, status, abilities, and opinion enrich the university community. We commit ourselves to the pursuit of excellence in teaching, research, outreach, and diversity as inextricably linked goals. The University of Wisconsin-Madison fulfills its public mission by creating a welcoming and inclusive community for people from every background - people who as students, faculty, and staff serve Wisconsin and the world. For more information on diversity and inclusion on campus, please visit: Diversity and Inclusion

Preferred Bachelor's Degree Nursing

Qualifications:

Minimum one year nursing experience required. Candidates should have exceptional clinical nursing skills and expertise coupled with a strong interest in clinical research. Prior experience working with Oncology patients is preferred. Prior clinical research experience preferred. License/Certification should also include BLS certification required

License/Certification:

Required RN - Registered Nurse - State Licensure And/Or Compact State Licensure Required BCLS - Basic Life Support

Full or Part Time: 80% - 100% This position may require some work to be performed in-person, onsite, at a designated campus work location. Some work may be performed remotely, at an offsite, non-campus work location.

Appointment Type, Duration:

Ongoing/Renewable

Minimum $68,000 ANNUAL (12 months) Depending on Qualifications

Additional Information:

- Work experience should demonstrate dependability, flexibility, and maturity. Candidates must be effective at building interpersonal relationships with constructive interactions, be clear and effective communicators, promote and create collegial environments that value accountability. Employees will also be expected to uphold UWCCC core values as defined below: - Respect: Demonstrate respect for self and others -- behave professionally. - Integrity: Act with integrity and honesty. - Teamwork: Commit to and demonstrate teamwork. - Excellence: Ensure excellence, quality, and high ethical standards in conduct and performance. -TB testing and a Caregiver Background Check will be required at the time of employment. This position has been identified as a position of trust with access to vulnerable populations. The selected candidate will be required to pass an initial Caregiver Check to be eligible for employment under the Wisconsin Caregiver Law and then every four years. - The successful applicant will be responsible for ensuring eligibility for employment in the United States on or before the effective date of the appointment.

How to Apply:

To apply for this position, please click on the "Apply Now" button. You will be asked to upload a resume and cover letter, and provide three professional/supervisor references as a part of the application process. Please ensure that the resume and cover letter address how you meet the minimum/preferred qualifications for the position.

Jennifer Wilkie [email protected] 608-262-8025 Relay Access (WTRS): 7-1-1. See RELAY_SERVICE for further information.

Official Title:

Research Nurse(HS042)

Department(s):

A53-MEDICAL SCHOOL/CARBONE CANC CTR/CANC CTR

Employment Class:

Academic Staff-Renewable

Job Number:

The university of wisconsin-madison is an equal opportunity and affirmative action employer..

You will be redirected to the application to launch your career momentarily. Thank you!

Frequently Asked Questions

Applicant Tutorial

Disability Accommodations

Pay Transparency Policy Statement

Refer a Friend

You've sent this job to a friend!

Website feedback, questions or accessibility issues: [email protected] .

Learn more about accessibility at UW–Madison .

© 2016–2024 Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System • Privacy Statement

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Clinical Trials & the Role of the Oncology Clinical Trials Nurse

Elizabeth a. ness.

a Nurse Consultant for Education, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute

Cheryl Royce

b Chief, Office of Research Nursing, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute

Clinical trials will continue to be paramount to improving human health. New trial designs and informed consent issues are emerging as a result of genomic profiling and the development of molecularly targeted agents. Many groups and individuals are responsible for ensuring the protection of research participants and the quality of the data produced. The specialty role of the Clinical Trials Nurse (CTN) is critical to the implementation of clinical trials. Oncology CTNs have established competencies that can help guide their practice; yet, not all oncology CTNs are supervised by a nurse. Using the process of engagement, one organization has successfully restructured the oncology CTNs under a nurse-supervised model.

INTRODUCTION

Today’s standard of care was yesterday’s clinical trial. Oncology clinical trials have been and will continue to be the cornerstone for improving outcomes for individuals at risk for and living with cancer. A clinical trial is a type of patient-oriented clinical research study which prospectively assigns a participant, also known as a human subject, to one or more biomedical or behavioral interventions to evaluate health-related outcomes. 1 Discovering these new interventions and developing, implementing, and monitoring a clinical trial involves many groups and individuals ( Box 1 ). Collectively their responsibility is to ensure that the rights and well-being of the research participants are protected and to advance scientific knowledge by ensuring that data generated by the trial is accurate, verifiable, and reproducible. 2 , 3 A key role in successful implementation of a clinical trial is the study coordinator. 4

Key Groups and Individuals Responsible for Ensuring Good Clinical Practice (GCP)

Clinical trials nursing is a specialty practice that includes a variety of roles (e.g., study coordinator, direct care nurse, nurse manager, nurse educator), settings (e.g., academic medical center, private practice, research unit), and clinical specialties (e.g., oncology, cardiology, infectious disease). The clinical trials nurse (CTN) serves as a study coordinator but may have different job titles (e.g., Research Nurse Coordinator, Clinical Research Nurse, Clinical Research Coordinator) and may be supervised by a physician, investigator, or a non-nurse research manager. 5 – 9 The purpose of this article is to provide an overview of clinical trials, highlight the role of the oncology CTN (i.e., the nurse in the role of study coordinator), and share one organization’s process to unite all CTNs under one nursing office.

OVERVIEW OF CLINICAL TRIALS

Good Clinical Practice (GCP) is an international ethical and scientific set of standards for the design and conduct of research involving humans including: protocol design, conduct, performance, monitoring, auditing, recording, analyses, and reporting. It includes both regulations, which are binding, and guidelines or guidances, which are not binding, though recommended to be followed. In response to historical events of the past, regulations and guidelines have been developed ( Box 2 ). 2 – 3

U.S. Regulations Related to Clinical Trials

Several groups with regulatory authority are involved in the conduct of clinical trials in the United States (U.S.). In the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), the two main titles related to clinical trials are Title 45 (Public Welfare) and Title 21 (Food and Drugs). Guidance documents describe an agency’s interpretation of or policy on a regulatory issue. Title 45 Part 46 is interpreted by the Office for Human Research Protections. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) interprets Title 21 and its subparts. 11 – 12

There are five types of clinical trials ( Table 1 ). 13 , 14 Treatment clinical trials can further be characterized by phases ( Table 2 ). 14 – 16 Advancements in cancer biology, genomic profiling and the development of molecularly targeted agents (MTAs) have led trialists to re-think traditional trial designs. The emergence of basket, umbrella, and adaptive trials are examples of novel designs now being used in oncology clinical trials ( Table 3 ). 17 – 18

Types of Clinical Trials

Abbreviations: HPV, human papillomavirus; VHL, Von Hippel Lindau (VHL), BRCA1, BReast CAncer genes 1; PET, Positron emission tomography

Phases of Clinical Trials

Trials Designs for Targeted Therapies

MTA, Molecular Target Agent; NCI, National Cancer Institute; MATCH, Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice; Lung-Map, Lung Cancer Master Protocol; I-SPY 2 Trial, Investigation of Serial Studies to Predict Your Therapeutic Response With Imaging And moLecular Analysis 2

PROTOCOL DEVELOPMENT AND REVIEW PROCESS