How to Write a Body of a Research Paper

The main part of your research paper is called “the body.” To write this important part of your paper, include only relevant information, or information that gets to the point. Organize your ideas in a logical order—one that makes sense—and provide enough details—facts and examples—to support the points you want to make.

Logical Order

Transition words and phrases, adding evidence, phrases for supporting topic sentences.

- Transition Phrases for Comparisons

- Transition Phrases for Contrast

- Transition Phrases to Show a Process

- Phrases to Introduce Examples

- Transition Phrases for Presenting Evidence

How to Make Effective Transitions

Examples of effective transitions, drafting your conclusion, writing the body paragraphs.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

- The third and fourth paragraphs follow the same format as the second:

- Transition or topic sentence.

- Topic sentence (if not included in the first sentence).

- Supporting sentences including a discussion, quotations, or examples that support the topic sentence.

- Concluding sentence that transitions to the next paragraph.

The topic of each paragraph will be supported by the evidence you itemized in your outline. However, just as smooth transitions are required to connect your paragraphs, the sentences you write to present your evidence should possess transition words that connect ideas, focus attention on relevant information, and continue your discussion in a smooth and fluid manner.

You presented the main idea of your paper in the thesis statement. In the body, every single paragraph must support that main idea. If any paragraph in your paper does not, in some way, back up the main idea expressed in your thesis statement, it is not relevant, which means it doesn’t have a purpose and shouldn’t be there.

Each paragraph also has a main idea of its own. That main idea is stated in a topic sentence, either at the beginning or somewhere else in the paragraph. Just as every paragraph in your paper supports your thesis statement, every sentence in each paragraph supports the main idea of that paragraph by providing facts or examples that back up that main idea. If a sentence does not support the main idea of the paragraph, it is not relevant and should be left out.

A paper that makes claims or states ideas without backing them up with facts or clarifying them with examples won’t mean much to readers. Make sure you provide enough supporting details for all your ideas. And remember that a paragraph can’t contain just one sentence. A paragraph needs at least two or more sentences to be complete. If a paragraph has only one or two sentences, you probably haven’t provided enough support for your main idea. Or, if you have trouble finding the main idea, maybe you don’t have one. In that case, you can make the sentences part of another paragraph or leave them out.

Arrange the paragraphs in the body of your paper in an order that makes sense, so that each main idea follows logically from the previous one. Likewise, arrange the sentences in each paragraph in a logical order.

If you carefully organized your notes and made your outline, your ideas will fall into place naturally as you write your draft. The main ideas, which are building blocks of each section or each paragraph in your paper, come from the Roman-numeral headings in your outline. The supporting details under each of those main ideas come from the capital-letter headings. In a shorter paper, the capital-letter headings may become sentences that include supporting details, which come from the Arabic numerals in your outline. In a longer paper, the capital letter headings may become paragraphs of their own, which contain sentences with the supporting details, which come from the Arabic numerals in your outline.

In addition to keeping your ideas in logical order, transitions are another way to guide readers from one idea to another. Transition words and phrases are important when you are suggesting or pointing out similarities between ideas, themes, opinions, or a set of facts. As with any perfect phrase, transition words within paragraphs should not be used gratuitously. Their meaning must conform to what you are trying to point out, as shown in the examples below:

- “Accordingly” or “in accordance with” indicates agreement. For example :Thomas Edison’s experiments with electricity accordingly followed the theories of Benjamin Franklin, J. B. Priestly, and other pioneers of the previous century.

- “Analogous” or “analogously” contrasts different things or ideas that perform similar functions or make similar expressions. For example: A computer hard drive is analogous to a filing cabinet. Each stores important documents and data.

- “By comparison” or “comparatively”points out differences between things that otherwise are similar. For example: Roses require an alkaline soil. Azaleas, by comparison, prefer an acidic soil.

- “Corresponds to” or “correspondingly” indicates agreement or conformity. For example: The U.S. Constitution corresponds to England’s Magna Carta in so far as both established a framework for a parliamentary system.

- “Equals,”“equal to,” or “equally” indicates the same degree or quality. For example:Vitamin C is equally as important as minerals in a well-balanced diet.

- “Equivalent” or “equivalently” indicates two ideas or things of approximately the same importance, size, or volume. For example:The notions of individual liberty and the right to a fair and speedy trial hold equivalent importance in the American legal system.

- “Common” or “in common with” indicates similar traits or qualities. For example: Darwin did not argue that humans were descended from the apes. Instead, he maintained that they shared a common ancestor.

- “In the same way,”“in the same manner,”“in the same vein,” or “likewise,” connects comparable traits, ideas, patterns, or activities. For example: John Roebling’s suspension bridges in Brooklyn and Cincinnati were built in the same manner, with strong cables to support a metallic roadway. Example 2: Despite its delicate appearance, John Roebling’s Brooklyn Bridge was built as a suspension bridge supported by strong cables. Example 3: Cincinnati’s Suspension Bridge, which Roebling also designed, was likewise supported by cables.

- “Kindred” indicates that two ideas or things are related by quality or character. For example: Artists Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gauguin are considered kindred spirits in the Impressionist Movement. “Like” or “as” are used to create a simile that builds reader understanding by comparing two dissimilar things. (Never use “like” as slang, as in: John Roebling was like a bridge designer.) For examples: Her eyes shone like the sun. Her eyes were as bright as the sun.

- “Parallel” describes events, things, or ideas that occurred at the same time or that follow similar logic or patterns of behavior. For example:The original Ocktoberfests were held to occur in parallel with the autumn harvest.

- “Obviously” emphasizes a point that should be clear from the discussion. For example: Obviously, raccoons and other wildlife will attempt to find food and shelter in suburban areas as their woodland habitats disappear.

- “Similar” and “similarly” are used to make like comparisons. For example: Horses and ponies have similar physical characteristics although, as working farm animals, each was bred to perform different functions.

- “There is little debate” or “there is consensus” can be used to point out agreement. For example:There is little debate that the polar ice caps are melting.The question is whether global warming results from natural or human-made causes.

Other phrases that can be used to make transitions or connect ideas within paragraphs include:

- Use “alternately” or “alternatively” to suggest a different option.

- Use “antithesis” to indicate a direct opposite.

- Use “contradict” to indicate disagreement.

- Use “on the contrary” or “conversely” to indicate that something is different from what it seems.

- Use “dissimilar” to point out differences between two things.

- Use “diverse” to discuss differences among many things or people.

- Use “distinct” or “distinctly” to point out unique qualities.

- Use “inversely” to indicate an opposite idea.

- Use “it is debatable,” “there is debate,” or “there is disagreement” to suggest that there is more than one opinion about a subject.

- Use “rather” or “rather than” to point out an exception.

- Use “unique” or “uniquely” to indicate qualities that can be found nowhere else.

- Use “unlike” to indicate dissimilarities.

- Use “various” to indicate more than one kind.

Writing Topic Sentences

Remember, a sentence should express a complete thought, one thought per sentence—no more, no less. The longer and more convoluted your sentences become, the more likely you are to muddle the meaning, become repetitive, and bog yourself down in issues of grammar and construction. In your first draft, it is generally a good idea to keep those sentences relatively short and to the point. That way your ideas will be clearly stated.You will be able to clearly see the content that you have put down—what is there and what is missing—and add or subtract material as it is needed. The sentences will probably seem choppy and even simplistic.The purpose of a first draft is to ensure that you have recorded all the content you will need to make a convincing argument. You will work on smoothing and perfecting the language in subsequent drafts.

Transitioning from your topic sentence to the evidence that supports it can be problematic. It requires a transition, much like the transitions needed to move from one paragraph to the next. Choose phrases that connect the evidence directly to your topic sentence.

- Consider this: (give an example or state evidence).

- If (identify one condition or event) then (identify the condition or event that will follow).

- It should go without saying that (point out an obvious condition).

- Note that (provide an example or observation).

- Take a look at (identify a condition; follow with an explanation of why you think it is important to the discussion).

- The authors had (identify their idea) in mind when they wrote “(use a quotation from their text that illustrates the idea).”

- The point is that (summarize the conclusion your reader should draw from your research).

- This becomes evident when (name the author) says that (paraphrase a quote from the author’s writing).

- We see this in the following example: (provide an example of your own).

- (The author’s name) offers the example of (summarize an example given by the author).

If an idea is controversial, you may need to add extra evidence to your paragraphs to persuade your reader. You may also find that a logical argument, one based solely on your evidence, is not persuasive enough and that you need to appeal to the reader’s emotions. Look for ways to incorporate your research without detracting from your argument.

Writing Transition Sentences

It is often difficult to write transitions that carry a reader clearly and logically on to the next paragraph (and the next topic) in an essay. Because you are moving from one topic to another, it is easy to simply stop one and start another. Great research papers, however, include good transitions that link the ideas in an interesting discussion so that readers can move smoothly and easily through your presentation. Close each of your paragraphs with an interesting transition sentence that introduces the topic coming up in the next paragraph.

Transition sentences should show a relationship between the two topics.Your transition will perform one of the following functions to introduce the new idea:

- Indicate that you will be expanding on information in a different way in the upcoming paragraph.

- Indicate that a comparison, contrast, or a cause-and-effect relationship between the topics will be discussed.

- Indicate that an example will be presented in the next paragraph.

- Indicate that a conclusion is coming up.

Transitions make a paper flow smoothly by showing readers how ideas and facts follow one another to point logically to a conclusion. They show relationships among the ideas, help the reader to understand, and, in a persuasive paper, lead the reader to the writer’s conclusion.

Each paragraph should end with a transition sentence to conclude the discussion of the topic in the paragraph and gently introduce the reader to the topic that will be raised in the next paragraph. However, transitions also occur within paragraphs—from sentence to sentence—to add evidence, provide examples, or introduce a quotation.

The type of paper you are writing and the kinds of topics you are introducing will determine what type of transitional phrase you should use. Some useful phrases for transitions appear below. They are grouped according to the function they normally play in a paper. Transitions, however, are not simply phrases that are dropped into sentences. They are constructed to highlight meaning. Choose transitions that are appropriate to your topic and what you want the reader to do. Edit them to be sure they fit properly within the sentence to enhance the reader’s understanding.

Transition Phrases for Comparisons:

- We also see

- In addition to

- Notice that

- Beside that,

- In comparison,

- Once again,

- Identically,

- For example,

- Comparatively, it can be seen that

- We see this when

- This corresponds to

- In other words,

- At the same time,

- By the same token,

Transition Phrases for Contrast:

- By contrast,

- On the contrary,

- Nevertheless,

- An exception to this would be …

- Alongside that,we find …

- On one hand … on the other hand …

- [New information] presents an opposite view …

- Conversely, it could be argued …

- Other than that,we find that …

- We get an entirely different impression from …

- One point of differentiation is …

- Further investigation shows …

- An exception can be found in the fact that …

Transition Phrases to Show a Process:

- At the top we have … Near the bottom we have …

- Here we have … There we have …

- Continuing on,

- We progress to …

- Close up … In the distance …

- With this in mind,

- Moving in sequence,

- Proceeding sequentially,

- Moving to the next step,

- First, Second,Third,…

- Examining the activities in sequence,

- Sequentially,

- As a result,

- The end result is …

- To illustrate …

- Subsequently,

- One consequence of …

- If … then …

- It follows that …

- This is chiefly due to …

- The next step …

- Later we find …

Phrases to Introduce Examples:

- For instance,

- Particularly,

- In particular,

- This includes,

- Specifically,

- To illustrate,

- One illustration is

- One example is

- This is illustrated by

- This can be seen when

- This is especially seen in

- This is chiefly seen when

Transition Phrases for Presenting Evidence:

- Another point worthy of consideration is

- At the center of the issue is the notion that

- Before moving on, it should be pointed out that

- Another important point is

- Another idea worth considering is

- Consequently,

- Especially,

- Even more important,

- Getting beyond the obvious,

- In spite of all this,

- It follows that

- It is clear that

- More importantly,

- Most importantly,

How to make effective transitions between sections of a research paper? There are two distinct issues in making strong transitions:

- Does the upcoming section actually belong where you have placed it?

- Have you adequately signaled the reader why you are taking this next step?

The first is the most important: Does the upcoming section actually belong in the next spot? The sections in your research paper need to add up to your big point (or thesis statement) in a sensible progression. One way of putting that is, “Does the architecture of your paper correspond to the argument you are making?” Getting this architecture right is the goal of “large-scale editing,” which focuses on the order of the sections, their relationship to each other, and ultimately their correspondence to your thesis argument.

It’s easy to craft graceful transitions when the sections are laid out in the right order. When they’re not, the transitions are bound to be rough. This difficulty, if you encounter it, is actually a valuable warning. It tells you that something is wrong and you need to change it. If the transitions are awkward and difficult to write, warning bells should ring. Something is wrong with the research paper’s overall structure.

After you’ve placed the sections in the right order, you still need to tell the reader when he is changing sections and briefly explain why. That’s an important part of line-by-line editing, which focuses on writing effective sentences and paragraphs.

Effective transition sentences and paragraphs often glance forward or backward, signaling that you are switching sections. Take this example from J. M. Roberts’s History of Europe . He is finishing a discussion of the Punic Wars between Rome and its great rival, Carthage. The last of these wars, he says, broke out in 149 B.C. and “ended with so complete a defeat for the Carthaginians that their city was destroyed . . . .” Now he turns to a new section on “Empire.” Here is the first sentence: “By then a Roman empire was in being in fact if not in name.”(J. M. Roberts, A History of Europe . London: Allen Lane, 1997, p. 48) Roberts signals the transition with just two words: “By then.” He is referring to the date (149 B.C.) given near the end of the previous section. Simple and smooth.

Michael Mandelbaum also accomplishes this transition between sections effortlessly, without bringing his narrative to a halt. In The Ideas That Conquered the World: Peace, Democracy, and Free Markets , one chapter shows how countries of the North Atlantic region invented the idea of peace and made it a reality among themselves. Here is his transition from one section of that chapter discussing “the idea of warlessness” to another section dealing with the history of that idea in Europe.

The widespread aversion to war within the countries of the Western core formed the foundation for common security, which in turn expressed the spirit of warlessness. To be sure, the rise of common security in Europe did not abolish war in other parts of the world and could not guarantee its permanent abolition even on the European continent. Neither, however, was it a flukish, transient product . . . . The European common security order did have historical precedents, and its principal features began to appear in other parts of the world. Precedents for Common Security The security arrangements in Europe at the dawn of the twenty-first century incorporated features of three different periods of the modern age: the nineteenth century, the interwar period, and the ColdWar. (Michael Mandelbaum, The Ideas That Conquered the World: Peace, Democracy, and Free Markets . New York: Public Affairs, 2002, p. 128)

It’s easier to make smooth transitions when neighboring sections deal with closely related subjects, as Mandelbaum’s do. Sometimes, however, you need to end one section with greater finality so you can switch to a different topic. The best way to do that is with a few summary comments at the end of the section. Your readers will understand you are drawing this topic to a close, and they won’t be blindsided by your shift to a new topic in the next section.

Here’s an example from economic historian Joel Mokyr’s book The Lever of Riches: Technological Creativity and Economic Progress . Mokyr is completing a section on social values in early industrial societies. The next section deals with a quite different aspect of technological progress: the role of property rights and institutions. So Mokyr needs to take the reader across a more abrupt change than Mandelbaum did. Mokyr does that in two ways. First, he summarizes his findings on social values, letting the reader know the section is ending. Then he says the impact of values is complicated, a point he illustrates in the final sentences, while the impact of property rights and institutions seems to be more straightforward. So he begins the new section with a nod to the old one, noting the contrast.

In commerce, war and politics, what was functional was often preferred [within Europe] to what was aesthetic or moral, and when it was not, natural selection saw to it that such pragmatism was never entirely absent in any society. . . . The contempt in which physical labor, commerce, and other economic activity were held did not disappear rapidly; much of European social history can be interpreted as a struggle between wealth and other values for a higher step in the hierarchy. The French concepts of bourgeois gentilhomme and nouveau riche still convey some contempt for people who joined the upper classes through economic success. Even in the nineteenth century, the accumulation of wealth was viewed as an admission ticket to social respectability to be abandoned as soon as a secure membership in the upper classes had been achieved. Institutions and Property Rights The institutional background of technological progress seems, on the surface, more straightforward. (Joel Mokyr, The Lever of Riches: Technological Creativity and Economic Progress . New York: Oxford University Press, 1990, p. 176)

Note the phrase, “on the surface.” Mokyr is hinting at his next point, that surface appearances are deceiving in this case. Good transitions between sections of your research paper depend on:

- Getting the sections in the right order

- Moving smoothly from one section to the next

- Signaling readers that they are taking the next step in your argument

- Explaining why this next step comes where it does

Every good paper ends with a strong concluding paragraph. To write a good conclusion, sum up the main points in your paper. To write an even better conclusion, include a sentence or two that helps the reader answer the question, “So what?” or “Why does all this matter?” If you choose to include one or more “So What?” sentences, remember that you still need to support any point you make with facts or examples. Remember, too, that this is not the place to introduce new ideas from “out of the blue.” Make sure that everything you write in your conclusion refers to what you’ve already written in the body of your paper.

Back to How To Write A Research Paper .

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9.2 Writing Body Paragraphs

Learning objectives.

- Select primary support related to your thesis.

- Support your topic sentences.

If your thesis gives the reader a roadmap to your essay, then body paragraphs should closely follow that map. The reader should be able to predict what follows your introductory paragraph by simply reading the thesis statement.

The body paragraphs present the evidence you have gathered to confirm your thesis. Before you begin to support your thesis in the body, you must find information from a variety of sources that support and give credit to what you are trying to prove.

Select Primary Support for Your Thesis

Without primary support, your argument is not likely to be convincing. Primary support can be described as the major points you choose to expand on your thesis. It is the most important information you select to argue for your point of view. Each point you choose will be incorporated into the topic sentence for each body paragraph you write. Your primary supporting points are further supported by supporting details within the paragraphs.

Remember that a worthy argument is backed by examples. In order to construct a valid argument, good writers conduct lots of background research and take careful notes. They also talk to people knowledgeable about a topic in order to understand its implications before writing about it.

Identify the Characteristics of Good Primary Support

In order to fulfill the requirements of good primary support, the information you choose must meet the following standards:

- Be specific. The main points you make about your thesis and the examples you use to expand on those points need to be specific. Use specific examples to provide the evidence and to build upon your general ideas. These types of examples give your reader something narrow to focus on, and if used properly, they leave little doubt about your claim. General examples, while they convey the necessary information, are not nearly as compelling or useful in writing because they are too obvious and typical.

- Be relevant to the thesis. Primary support is considered strong when it relates directly to the thesis. Primary support should show, explain, or prove your main argument without delving into irrelevant details. When faced with lots of information that could be used to prove your thesis, you may think you need to include it all in your body paragraphs. But effective writers resist the temptation to lose focus. Choose your examples wisely by making sure they directly connect to your thesis.

- Be detailed. Remember that your thesis, while specific, should not be very detailed. The body paragraphs are where you develop the discussion that a thorough essay requires. Using detailed support shows readers that you have considered all the facts and chosen only the most precise details to enhance your point of view.

Prewrite to Identify Primary Supporting Points for a Thesis Statement

Recall that when you prewrite you essentially make a list of examples or reasons why you support your stance. Stemming from each point, you further provide details to support those reasons. After prewriting, you are then able to look back at the information and choose the most compelling pieces you will use in your body paragraphs.

Choose one of the following working thesis statements. On a separate sheet of paper, write for at least five minutes using one of the prewriting techniques you learned in Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” .

- Unleashed dogs on city streets are a dangerous nuisance.

- Students cheat for many different reasons.

- Drug use among teens and young adults is a problem.

- The most important change that should occur at my college or university is ____________________________________________.

Select the Most Effective Primary Supporting Points for a Thesis Statement

After you have prewritten about your working thesis statement, you may have generated a lot of information, which may be edited out later. Remember that your primary support must be relevant to your thesis. Remind yourself of your main argument, and delete any ideas that do not directly relate to it. Omitting unrelated ideas ensures that you will use only the most convincing information in your body paragraphs. Choose at least three of only the most compelling points. These will serve as the topic sentences for your body paragraphs.

Refer to the previous exercise and select three of your most compelling reasons to support the thesis statement. Remember that the points you choose must be specific and relevant to the thesis. The statements you choose will be your primary support points, and you will later incorporate them into the topic sentences for the body paragraphs.

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

When you support your thesis, you are revealing evidence. Evidence includes anything that can help support your stance. The following are the kinds of evidence you will encounter as you conduct your research:

- Facts. Facts are the best kind of evidence to use because they often cannot be disputed. They can support your stance by providing background information on or a solid foundation for your point of view. However, some facts may still need explanation. For example, the sentence “The most populated state in the United States is California” is a pure fact, but it may require some explanation to make it relevant to your specific argument.

- Judgments. Judgments are conclusions drawn from the given facts. Judgments are more credible than opinions because they are founded upon careful reasoning and examination of a topic.

- Testimony. Testimony consists of direct quotations from either an eyewitness or an expert witness. An eyewitness is someone who has direct experience with a subject; he adds authenticity to an argument based on facts. An expert witness is a person who has extensive experience with a topic. This person studies the facts and provides commentary based on either facts or judgments, or both. An expert witness adds authority and credibility to an argument.

- Personal observation. Personal observation is similar to testimony, but personal observation consists of your testimony. It reflects what you know to be true because you have experiences and have formed either opinions or judgments about them. For instance, if you are one of five children and your thesis states that being part of a large family is beneficial to a child’s social development, you could use your own experience to support your thesis.

Writing at Work

In any job where you devise a plan, you will need to support the steps that you lay out. This is an area in which you would incorporate primary support into your writing. Choosing only the most specific and relevant information to expand upon the steps will ensure that your plan appears well-thought-out and precise.

You can consult a vast pool of resources to gather support for your stance. Citing relevant information from reliable sources ensures that your reader will take you seriously and consider your assertions. Use any of the following sources for your essay: newspapers or news organization websites, magazines, encyclopedias, and scholarly journals, which are periodicals that address topics in a specialized field.

Choose Supporting Topic Sentences

Each body paragraph contains a topic sentence that states one aspect of your thesis and then expands upon it. Like the thesis statement, each topic sentence should be specific and supported by concrete details, facts, or explanations.

Each body paragraph should comprise the following elements.

topic sentence + supporting details (examples, reasons, or arguments)

As you read in Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” , topic sentences indicate the location and main points of the basic arguments of your essay. These sentences are vital to writing your body paragraphs because they always refer back to and support your thesis statement. Topic sentences are linked to the ideas you have introduced in your thesis, thus reminding readers what your essay is about. A paragraph without a clearly identified topic sentence may be unclear and scattered, just like an essay without a thesis statement.

Unless your teacher instructs otherwise, you should include at least three body paragraphs in your essay. A five-paragraph essay, including the introduction and conclusion, is commonly the standard for exams and essay assignments.

Consider the following the thesis statement:

Author J.D. Salinger relied primarily on his personal life and belief system as the foundation for the themes in the majority of his works.

The following topic sentence is a primary support point for the thesis. The topic sentence states exactly what the controlling idea of the paragraph is. Later, you will see the writer immediately provide support for the sentence.

Salinger, a World War II veteran, suffered from posttraumatic stress disorder, a disorder that influenced themes in many of his works.

In Note 9.19 “Exercise 2” , you chose three of your most convincing points to support the thesis statement you selected from the list. Take each point and incorporate it into a topic sentence for each body paragraph.

Supporting point 1: ____________________________________________

Topic sentence: ____________________________________________

Supporting point 2: ____________________________________________

Supporting point 3: ____________________________________________

Draft Supporting Detail Sentences for Each Primary Support Sentence

After deciding which primary support points you will use as your topic sentences, you must add details to clarify and demonstrate each of those points. These supporting details provide examples, facts, or evidence that support the topic sentence.

The writer drafts possible supporting detail sentences for each primary support sentence based on the thesis statement:

Thesis statement: Unleashed dogs on city streets are a dangerous nuisance.

Supporting point 1: Dogs can scare cyclists and pedestrians.

Supporting details:

- Cyclists are forced to zigzag on the road.

- School children panic and turn wildly on their bikes.

- People who are walking at night freeze in fear.

Supporting point 2:

Loose dogs are traffic hazards.

- Dogs in the street make people swerve their cars.

- To avoid dogs, drivers run into other cars or pedestrians.

- Children coaxing dogs across busy streets create danger.

Supporting point 3: Unleashed dogs damage gardens.

- They step on flowers and vegetables.

- They destroy hedges by urinating on them.

- They mess up lawns by digging holes.

The following paragraph contains supporting detail sentences for the primary support sentence (the topic sentence), which is underlined.

Salinger, a World War II veteran, suffered from posttraumatic stress disorder, a disorder that influenced the themes in many of his works. He did not hide his mental anguish over the horrors of war and once told his daughter, “You never really get the smell of burning flesh out of your nose, no matter how long you live.” His short story “A Perfect Day for a Bananafish” details a day in the life of a WWII veteran who was recently released from an army hospital for psychiatric problems. The man acts questionably with a little girl he meets on the beach before he returns to his hotel room and commits suicide. Another short story, “For Esmé – with Love and Squalor,” is narrated by a traumatized soldier who sparks an unusual relationship with a young girl he meets before he departs to partake in D-Day. Finally, in Salinger’s only novel, The Catcher in the Rye , he continues with the theme of posttraumatic stress, though not directly related to war. From a rest home for the mentally ill, sixteen-year-old Holden Caulfield narrates the story of his nervous breakdown following the death of his younger brother.

Using the three topic sentences you composed for the thesis statement in Note 9.18 “Exercise 1” , draft at least three supporting details for each point.

Thesis statement: ____________________________________________

Primary supporting point 1: ____________________________________________

Supporting details: ____________________________________________

Primary supporting point 2: ____________________________________________

Primary supporting point 3: ____________________________________________

You have the option of writing your topic sentences in one of three ways. You can state it at the beginning of the body paragraph, or at the end of the paragraph, or you do not have to write it at all. This is called an implied topic sentence. An implied topic sentence lets readers form the main idea for themselves. For beginning writers, it is best to not use implied topic sentences because it makes it harder to focus your writing. Your instructor may also want to clearly identify the sentences that support your thesis. For more information on the placement of thesis statements and implied topic statements, see Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” .

Print out the first draft of your essay and use a highlighter to mark your topic sentences in the body paragraphs. Make sure they are clearly stated and accurately present your paragraphs, as well as accurately reflect your thesis. If your topic sentence contains information that does not exist in the rest of the paragraph, rewrite it to more accurately match the rest of the paragraph.

Key Takeaways

- Your body paragraphs should closely follow the path set forth by your thesis statement.

- Strong body paragraphs contain evidence that supports your thesis.

- Primary support comprises the most important points you use to support your thesis.

- Strong primary support is specific, detailed, and relevant to the thesis.

- Prewriting helps you determine your most compelling primary support.

- Evidence includes facts, judgments, testimony, and personal observation.

- Reliable sources may include newspapers, magazines, academic journals, books, encyclopedias, and firsthand testimony.

- A topic sentence presents one point of your thesis statement while the information in the rest of the paragraph supports that point.

- A body paragraph comprises a topic sentence plus supporting details.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Are you seeking one-on-one college counseling and/or essay support? Limited spots are now available. Click here to learn more.

How to Write a Body Paragraph for a College Essay

January 29, 2024

No matter the discipline, college success requires mastering several academic basics, including the body paragraph. This article will provide tips on drafting and editing a strong body paragraph before examining several body paragraph examples. Before we look at how to start a body paragraph and how to write a body paragraph for a college essay (or other writing assignment), let’s define what exactly a body paragraph is.

What is a Body Paragraph?

Simply put, a body paragraph consists of everything in an academic essay that does not constitute the introduction and conclusion. It makes up everything in between. In a five-paragraph, thesis-style essay (which most high schoolers encounter before heading off to college), there are three body paragraphs. Longer essays with more complex arguments will include many more body paragraphs.

We might correlate body paragraphs with bodily appendages—say, a leg. Both operate in a somewhat isolated way to perform specific operations, yet are integral to creating a cohesive, functioning whole. A leg helps the body sit, walk, and run. Like legs, body paragraphs work to move an essay along, by leading the reader through several convincing ideas. Together, these ideas, sometimes called topics, or points, work to prove an overall argument, called the essay’s thesis.

If you compared an essay on Kant’s theory of beauty to an essay on migratory birds, you’d notice that the body paragraphs differ drastically. However, on closer inspection, you’d probably find that they included many of the same key components. Most body paragraphs will include specific, detailed evidence, an analysis of the evidence, a conclusion drawn by the author, and several tie-ins to the larger ideas at play. They’ll also include transitions and citations leading the reader to source material. We’ll go into more detail on these components soon. First, let’s see if you’ve organized your essay so that you’ll know how to start a body paragraph.

How to Start a Body Paragraph

It can be tempting to start writing your college essay as soon as you sit down at your desk. The sooner begun, the sooner done, right? I’d recommend resisting that itch. Instead, pull up a blank document on your screen and make an outline. There are numerous reasons to make an outline, and most involve helping you stay on track. This is especially true of longer college papers, like the 60+ page dissertation some seniors are required to write. Even with regular writing assignments with a page count between 4-10, an outline will help you visualize your argumentation strategy. Moreover, it will help you order your key points and their relevant evidence from most to least convincing. This in turn will determine the order of your body paragraphs.

The most convincing sequence of body paragraphs will depend entirely on your paper’s subject. Let’s say you’re writing about Penelope’s success in outwitting male counterparts in The Odyssey . You may want to begin with Penelope’s weaving, the most obvious way in which Penelope dupes her suitors. You can end with Penelope’s ingenious way of outsmarting her own husband. Because this evidence is more ambiguous it will require a more nuanced analysis. Thus, it’ll work best as your final body paragraph, after readers have already been convinced of more digestible evidence. If in doubt, keep your body paragraph order chronological.

It can be worthwhile to consider your topic from multiple perspectives. You may decide to include a body paragraph that sets out to consider and refute an opposing point to your thesis. This type of body paragraph will often appear near the end of the essay. It works to erase any lingering doubts readers may have had, and requires strong rhetorical techniques.

How to Start a Body Paragraph, Continued

Once you’ve determined which key points will best support your argument and in what order, draft an introduction. This is a crucial step towards writing a body paragraph. First, it will set the tone for the rest of your paper. Second, it will require you to articulate your thesis statement in specific, concise wording. Highlight or bold your thesis statement, so you can refer back to it quickly. You should be looking at your thesis throughout the drafting of your body paragraphs.

Finally, make sure that your introduction indicates which key points you’ll be covering in your body paragraphs, and in what order. While this level of organization might seem like overkill, it will indicate to the reader that your entire paper is minutely thought-out. It will boost your reader’s confidence going in. They’ll feel reassured and open to your thought process if they can see that it follows a clear path.

Now that you have an essay outline and introduction, you’re ready to draft your body paragraphs.

How to Draft a Body Paragraph

At this point, you know your body paragraph topic, the key point you’re trying to make, and you’ve gathered your evidence. The next thing to do is write! The words highlighted in bold below comprise the main components that will make up your body paragraph. (You’ll notice in the body paragraph examples below that the order of these components is flexible.)

Start with a topic sentence . This will indicate the main point you plan to make that will work to support your overall thesis. Your topic sentence also alerts the reader to the change in topic from the last paragraph to the current one. In making this new topic known, you’ll want to create a transition from the last topic to this one.

Transitions appear in nearly every paragraph of a college essay, apart from the introduction. They create a link between disparate ideas. (For example, if your transition comes at the end of paragraph 4, you won’t need a second transition at the beginning of paragraph 5.) The University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Writing Center has a page devoted to Developing Strategic Transitions . Likewise, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Writing Center offers help on paragraph transitions .

How to Draft a Body Paragraph for a College Essay ( Continued)

With the topic sentence written, you’ll need to prove your point through tangible evidence. This requires several sentences with various components. You’ll want to provide more context , going into greater detail to situate the reader within the topic. Next, you’ll provide evidence , often in the form of a quote, facts, or data, and supply a source citation . Citing your source is paramount. Sources indicate that your evidence is empirical and objective. It implies that your evidence is knowledge shared by others in the academic community. Sometimes you’ll want to provide multiple pieces of evidence, if the evidence is similar and can be grouped together.

After providing evidence, you must provide an interpretation and analysis of this evidence. In other words, use rhetorical techniques to paraphrase what your evidence seems to suggest. Break down the evidence further and explain and summarize it in new words. Don’t simply skip to your conclusion. Your evidence should never stand for itself. Why? Because your interpretation and analysis allow you to exhibit original, analytical, and critical thinking skills.

Depending on what evidence you’re using, you may repeat some of these components in the same body paragraph. This might look like: more context + further evidence + increased interpretation and analysis . All this will add up to proving and reaffirming your body paragraph’s main point . To do so, conclude your body paragraph by reformulating your thesis statement in light of the information you’ve given. I recommend comparing your original thesis statement to your paragraph’s concluding statement. Do they align? Does your body paragraph create a sound connection to the overall academic argument? If not, you’ll need to fix this issue when you edit your body paragraph.

How to Edit a Body Paragraph

As you go over each body paragraph of your college essay, keep this short checklist in mind.

- Consistency in your argument: If your key points don’t add up to a cogent argument, you’ll need to identify where the inconsistency lies. Often it lies in interpretation and analysis. You may need to improve the way you articulate this component. Try to think like a lawyer: how can you use this evidence to your advantage? If that doesn’t work, you may need to find new evidence. As a last resort, amend your thesis statement.

- Language-level persuasion. Use a broad vocabulary. Vary your sentence structure. Don’t repeat the same words too often, which can induce mental fatigue in the reader. I suggest keeping an online dictionary open on your browser. I find Merriam-Webster user-friendly, since it allows you to toggle between definitions and synonyms. It also includes up-to-date example sentences. Also, don’t forget the power of rhetorical devices .

- Does your writing flow naturally from one idea to the next, or are there jarring breaks? The editing stage is a great place to polish transitions and reinforce the structure as a whole.

Our first body paragraph example comes from the College Transitions article “ How to Write the AP Lang Argument Essay .” Here’s the prompt: Write an essay that argues your position on the value of striving for perfection.

Here’s the example thesis statement, taken from the introduction paragraph: “Striving for perfection can only lead us to shortchange ourselves. Instead, we should value learning, growth, and creativity and not worry whether we are first or fifth best.” Now let’s see how this writer builds an argument against perfection through one main point across two body paragraphs. (While this writer has split this idea into two paragraphs, one to address a problem and one to provide an alternative resolution, it could easily be combined into one paragraph.)

“Students often feel the need to be perfect in their classes, and this can cause students to struggle or stop making an effort in class. In elementary and middle school, for example, I was very nervous about public speaking. When I had to give a speech, my voice would shake, and I would turn very red. My teachers always told me “relax!” and I got Bs on Cs on my speeches. As a result, I put more pressure on myself to do well, spending extra time making my speeches perfect and rehearsing late at night at home. But this pressure only made me more nervous, and I started getting stomach aches before speaking in public.

“Once I got to high school, however, I started doing YouTube make-up tutorials with a friend. We made videos just for fun, and laughed when we made mistakes or said something silly. Only then, when I wasn’t striving to be perfect, did I get more comfortable with public speaking.”

Body Paragraph Example 1 Dissected

In this body paragraph example, the writer uses their personal experience as evidence against the value of striving for perfection. The writer sets up this example with a topic sentence that acts as a transition from the introduction. They also situate the reader in the classroom. The evidence takes the form of emotion and physical reactions to the pressure of public speaking (nervousness, shaking voice, blushing). Evidence also takes the form of poor results (mediocre grades). Rather than interpret the evidence from an analytical perspective, the writer produces more evidence to underline their point. (This method works fine for a narrative-style essay.) It’s clear that working harder to be perfect further increased the student’s nausea.

The writer proves their point in the second paragraph, through a counter-example. The main point is that improvement comes more naturally when the pressure is lifted; when amusement is possible and mistakes aren’t something to fear. This point ties back in with the thesis, that “we should value learning, growth, and creativity” over perfection.

This second body paragraph example comes from the College Transitions article “ How to Write the AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay .” Here’s an abridged version of the prompt: Rosa Parks was an African American civil rights activist who was arrested in 1955 for refusing to give up her seat on a segregated bus in Montgomery, Alabama. Read the passage carefully. Write an essay that analyzes the rhetorical choices Obama makes to convey his message.

Here’s the example thesis statement, taken from the introduction paragraph: “Through the use of diction that portrays Parks as quiet and demure, long lists that emphasize the extent of her impacts, and Biblical references, Obama suggests that all of us are capable of achieving greater good, just as Parks did.” Now read the body paragraph example, below.

“To further illustrate Parks’ impact, Obama incorporates Biblical references that emphasize the importance of “that single moment on the bus” (lines 57-58). In lines 33-35, Obama explains that Parks and the other protestors are “driven by a solemn determination to affirm their God-given dignity” and he also compares their victory to the fall the “ancient walls of Jericho” (line 43). By including these Biblical references, Obama suggests that Parks’ action on the bus did more than correct personal or political wrongs; it also corrected moral and spiritual wrongs. Although Parks had no political power or fortune, she was able to restore a moral balance in our world.”

Body Paragraph Example 2 Dissected

The first sentence in this body paragraph example indicates that the topic is transitioning into biblical references as a means of motivating ordinary citizens. The evidence comes as quotes taken from Obama’s speech. One is a reference to God, and the other an allusion to a story from the bible. The subsequent interpretation and analysis demonstrate that Obama’s biblical references imply a deeper, moral and spiritual significance. The concluding sentence draws together the morality inherent in equal rights with Rosa Parks’ power to spark change. Through the words “no political power or fortune,” and “moral balance,” the writer ties the point proven in this body paragraph back to the thesis statement. Obama promises that “All of us” (no matter how small our influence) “are capable of achieving greater good”—a greater moral good.

What’s Next?

Before you body paragraphs come the start and, after your body paragraphs, the conclusion, of course! If you’ve found this article helpful, be sure to read up on how to start a college essay and how to end a college essay .

You may also find the following blogs to be of interest:

- 6 Best Common App Essay Examples

- How to Write the Overcoming Challenges Essay

- UC Essay Examples

- How to Write the Community Essay

- How to Write the Why this Major? Essay

- College Essay

Kaylen Baker

With a BA in Literary Studies from Middlebury College, an MFA in Fiction from Columbia University, and a Master’s in Translation from Université Paris 8 Vincennes-Saint-Denis, Kaylen has been working with students on their writing for over five years. Previously, Kaylen taught a fiction course for high school students as part of Columbia Artists/Teachers, and served as an English Language Assistant for the French National Department of Education. Kaylen is an experienced writer/translator whose work has been featured in Los Angeles Review, Hybrid, San Francisco Bay Guardian, France Today, and Honolulu Weekly, among others.

- 2-Year Colleges

- Application Strategies

- Best Colleges by Major

- Best Colleges by State

- Big Picture

- Career & Personality Assessment

- College Search/Knowledge

- College Success

- Costs & Financial Aid

- Data Visualizations

- Dental School Admissions

- Extracurricular Activities

- Graduate School Admissions

- High School Success

- High Schools

- Homeschool Resources

- Law School Admissions

- Medical School Admissions

- Navigating the Admissions Process

- Online Learning

- Outdoor Adventure

- Private High School Spotlight

- Research Programs

- Summer Program Spotlight

- Summer Programs

- Teacher Tools

- Test Prep Provider Spotlight

“Innovative and invaluable…use this book as your college lifeline.”

— Lynn O'Shaughnessy

Nationally Recognized College Expert

College Planning in Your Inbox

Join our information-packed monthly newsletter.

10 min read

How to write strong essay body paragraphs (with examples)

In this blog post, we'll discuss how to write clear, convincing essay body paragraphs using many examples. We'll also be writing paragraphs together. By the end, you'll have a good understanding of how to write a strong essay body for any topic.

Table of Contents

Introduction, how to structure a body paragraph, creating an outline for our essay body, 1. a strong thesis statment takes a stand, 2. a strong thesis statement allows for debate, 3. a strong thesis statement is specific, writing the first essay body paragraph, how not to write a body paragraph, writing the second essay body paragraph.

After writing a great introduction to our essay, let's make our case in the body paragraphs. These are where we will present our arguments, back them up with evidence, and, in most cases, refute counterarguments. Introductions are very similar across the various types of essays. For example, an argumentative essay's introduction will be near identical to an introduction written for an expository essay. In contrast, the body paragraphs are structured differently depending on the type of essay.

In an expository essay, we are investigating an idea or analyzing the circumstances of a case. In contrast, we want to make compelling points with an argumentative essay to convince readers to agree with us.

The most straightforward technique to make an argument is to provide context first, then make a general point, and lastly back that point up in the following sentences. Not starting with your idea directly but giving context first is crucial in constructing a clear and easy-to-follow paragraph.

How to ideally structure a body paragraph:

- Provide context

- Make your thesis statement

- Support that argument

Now that we have the ideal structure for an argumentative essay, the best step to proceed is to outline the subsequent paragraphs. For the outline, we'll be writing one sentence that is simple in wording and describes the argument that we'll make in that paragraph concisely. Why are we doing that? An outline does more than give you a structure to work off of in the following essay body, thereby saving you time. It also helps you not to repeat yourself or, even worse, to accidentally contradict yourself later on.

While working on the outline, remember that revising your initial topic sentences is completely normal. They do not need to be flawless. Starting the outline with those thoughts can help accelerate writing the entire essay and can be very beneficial in avoiding writer's block.

For the essay body, we'll be proceeding with the topic we've written an introduction for in the previous article - the dangers of social media on society.

These are the main points I would like to make in the essay body regarding the dangers of social media:

Amplification of one's existing beliefs

Skewed comparisons

What makes a polished thesis statement?

Now that we've got our main points, let's create our outline for the body by writing one clear and straightforward topic sentence (which is the same as a thesis statement) for each idea. How do we write a great topic sentence? First, take a look at the three characteristics of a strong thesis statement.

Consider this thesis statement:

'While social media can have some negative effects, it can also be used positively.'

What stand does it take? Which negative and positive aspects does the author mean? While this one:

'Because social media is linked to a rise in mental health problems, it poses a danger to users.'

takes a clear stand and is very precise about the object of discussion.

If your thesis statement is not arguable, then your paper will not likely be enjoyable to read. Consider this thesis statement:

'Lots of people around the globe use social media.'

It does not allow for much discussion at all. Even if you were to argue that more or fewer people are using it on this planet, that wouldn't make for a very compelling argument.

'Although social media has numerous benefits, its various risks, including cyberbullying and possible addiction, mostly outweigh its benefits.'

Whether or not you consider this statement true, it allows for much more discussion than the previous one. It provides a basis for an engaging, thought-provoking paper by taking a position that you can discuss.

A thesis statement is one sentence that clearly states what you will discuss in that paragraph. It should give an overview of the main points you will discuss and show how these relate to your topic. For example, if you were to examine the rapid growth of social media, consider this thesis statement:

'There are many reasons for the rise in social media usage.'

That thesis statement is weak for two reasons. First, depending on the length of your essay, you might need to narrow your focus because the "rise in social media usage" can be a large and broad topic you cannot address adequately in a few pages. Secondly, the term "many reasons" is vague and does not give the reader an idea of what you will discuss in your paper.

In contrast, consider this thesis statement:

'The rise in social media usage is due to the increasing popularity of platforms like Facebook and Twitter, allowing users to connect with friends and share information effortlessly.'

Why is this better? Not only does it abide by the first two rules by allowing for debate and taking a stand, but this statement also narrows the subject down and identifies significant reasons for the increasing popularity of social media.

In conclusion : A strong thesis statement takes a clear stand, allows for discussion, and is specific.

Let's make use of how to write a good thopic sentence and put it into practise for our two main points from before. This is what good topic sentences could look like:

Echo chambers facilitated by social media promote political segregation in society.

Applied to the second argument:

Viewing other people's lives online through a distorted lens can lead to feelings of envy and inadequacy, as well as unrealistic expectations about one's life.

These topic sentences will be a very convenient structure for the whole body of our essay. Let's build out the first body paragraph, then closely examine how we did it so you can apply it to your essay.

Example: First body paragraph

If social media users mostly see content that reaffirms their existing beliefs, it can create an "echo chamber" effect. The echo chamber effect describes the user's limited exposure to diverse perspectives, making it challenging to examine those beliefs critically, thereby contributing to society's political polarization. This polarization emerges from social media becoming increasingly based on algorithms, which cater content to users based on their past interactions on the site. Further contributing to this shared narrative is the very nature of social media, allowing politically like-minded individuals to connect (Sunstein, 2018). Consequently, exposure to only one side of the argument can make it very difficult to see the other side's perspective, marginalizing opposing viewpoints. The entrenchment of one's beliefs by constant reaffirmation and amplification of political ideas results in segregation along partisan lines.

Sunstein, C. R (2018). #Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

In the first sentence, we provide context for the argument that we are about to make. Then, in the second sentence, we clearly state the topic we are addressing (social media contributing to political polarization).

Our topic sentence tells readers that a detailed discussion of the echo chamber effect and its consequences is coming next. All the following sentences, which make up most of the paragraph, either a) explain or b) support this point.

Finally, we answer the questions about how social media facilitates the echo chamber effect and the consequences. Try implementing the same structure in your essay body paragraph to allow for a logical and cohesive argument.

These paragraphs should be focused, so don't incorporate multiple arguments into one. Squeezing ideas into a single paragraph makes it challenging for readers to follow your reasoning. Instead, reserve each body paragraph for a single statement to be discussed and only switch to the next section once you feel that you thoroughly explained and supported your topic sentence.

Let's look at an example that might seem appropriate initially but should be modified.

Negative example: Try identifying the main argument

Over the past decade, social media platforms have become increasingly popular methods of communication and networking. However, these platforms' algorithmic nature fosters echo chambers or online spaces where users only encounter information that reinforces their existing beliefs. This echo chamber effect can lead to a lack of understanding or empathy for those with different perspectives and can even amplify the effects of confirmation bias. The same principle of one-sided exposure to opinions can be abstracted and applied to the biased subjection to lifestyles we see on social media. The constant exposure to these highly-curated and often unrealistic portrayals of other people's lives can lead us to believe that our own lives are inadequate in comparison. These feelings of inadequacy can be especially harmful to young people, who are still developing their sense of self.

Let's analyze this essay paragraph. Introducing the topic sentence by stating the social functions of social media is very useful because it provides context for the following argument. Naming those functions in the first sentence also allows for a smooth transition by contrasting the initial sentence ("However, ...") with the topic sentence. Also, the topic sentence abides by our three rules for creating a strong thesis statement:

- Taking a clear stand: algorithms are substantial contributors to the echo chamber effect

- Allowing for debate: there is literature rejecting this claim

- Being specific: analyzing a specific cause of the effect (algorithms).

So, where's the problem with this body paragraph?

It begins with what seems like a single argument (social media algorithms contributing to the echo chamber effect). Yet after addressing the consequences of the echo-chamber effect right after the thesis sentence, the author applies the same principle to a whole different topic. At the end of the paragraph, the reader is probably feeling confused. What was the paragraph trying to achieve in the first place?

We should place the second idea of being exposed to curated lifestyles in a separate section instead of shoehorning it into the end of the first one. All sentences following the thesis statement should either explain it or provide evidence (refuting counterarguments falls into this category, too).

With our first body paragraph done and having seen an example of what to avoid, let's take the topic of being exposed to curated lifestyles through social media and construct a separate body paragraph for it. We have already provided sufficient context for the reader to follow our argument, so it is unnecessary for this particular paragraph.

Body paragraph 2

Another cause for social media's destructiveness is the users' inclination to only share the highlights of their lives on social media, consequently distorting our perceptions of reality. A highly filtered view of their life leads to feelings of envy and inadequacy, as well as a distorted understanding of what is considered ordinary (Liu et al., 2018). In addition, frequent social media use is linked to decreased self-esteem and body satisfaction (Perloff, 2014). One way social media can provide a curated view of people's lives is through filters, making photos look more radiant, shadier, more or less saturated, and similar. Further, editing tools allow people to fundamentally change how their photos and videos look before sharing them, allowing for inserting or removing certain parts of the image. Editing tools give people considerable control over how their photos and videos look before sharing them, thereby facilitating the curation of one's online persona.

Perloff, R.M. Social Media Effects on Young Women's Body Image Concerns: Theoretical Perspectives and an Agenda for Research. Sex Roles 71, 363–377 (2014).

Liu, Hongbo & Wu, Laurie & Li, Xiang. (2018). Social Media Envy: How Experience Sharing on Social Networking Sites Drives Millennials' Aspirational Tourism Consumption. Journal of Travel Research. 58. 10.1177/0047287518761615.

Dr. Jacob Neumann put it this way in his book A professors guide to writing essays: 'If you've written strong and clear topic sentences, you're well on your way to creating focused paragraphs.'

They provide the basis for each paragraph's development and content, allowing you not to get caught up in the details and lose sight of the overall objective. It's crucial not to neglect that step. Apply these principles to your essay body, whatever the topic, and you'll set yourself up for the best possible results.

Sources used for creating this article

- Writing a solid thesis statement : https://www.vwu.edu/academics/academic-support/learning-center/pdfs/Thesis-Statement.pdf

- Neumann, Jacob. A professor's guide to writing essays. 2016.

Follow the Journey

Hello! I'm Josh, the founder of Wordful. We aim to make a product that makes writing amazing content easy and fun. Sign up to gain access first when Wordful goes public!

How to write an essay: Body

- What's in this guide

- Introduction

- Essay structure

- Additional resources

Body paragraphs

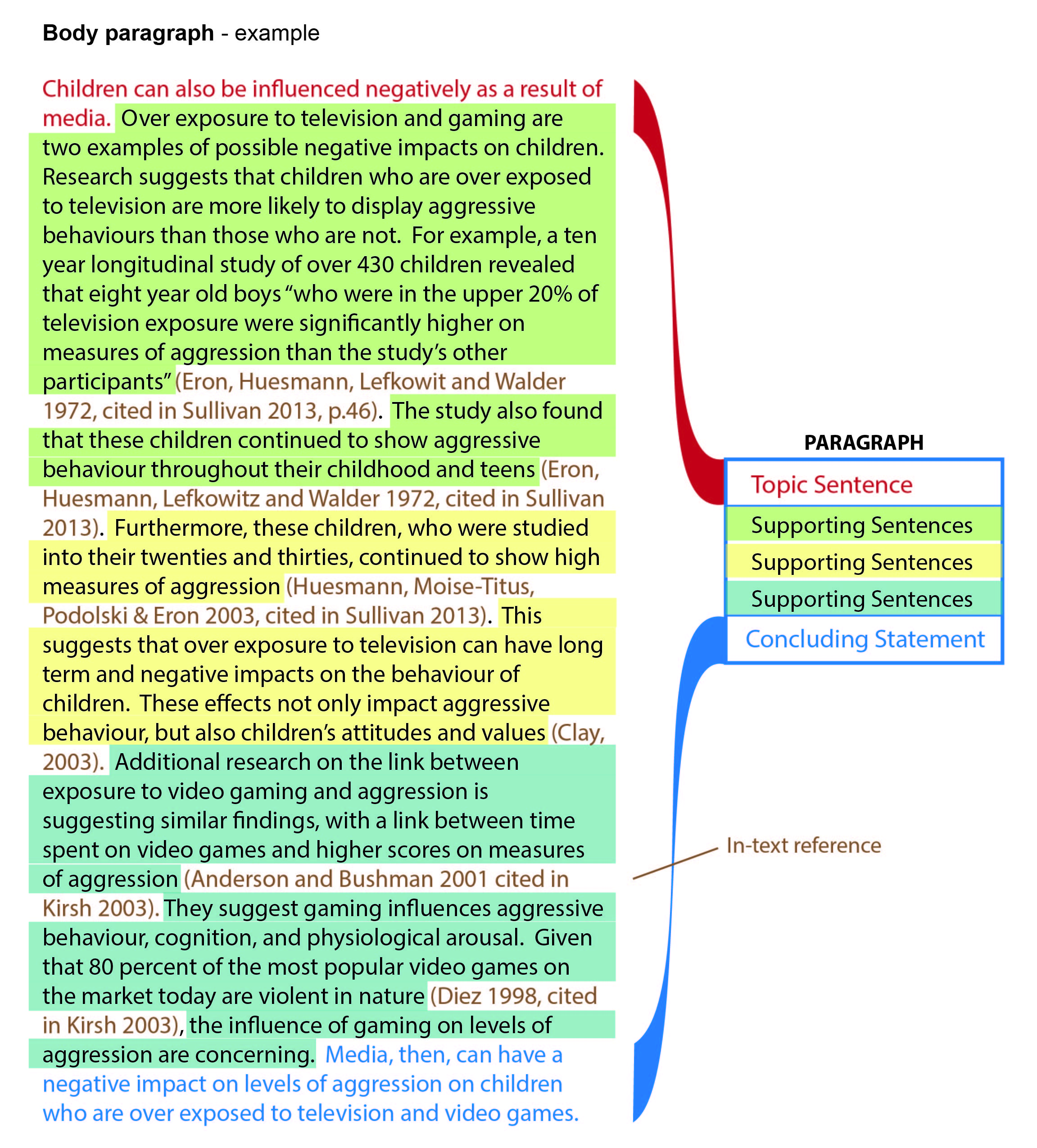

The essay body itself is organised into paragraphs, according to your plan. Remember that each paragraph focuses on one idea, or aspect of your topic, and should contain at least 4-5 sentences so you can deal with that idea properly.

Each body paragraph has three sections. First is the topic sentence . This lets the reader know what the paragraph is going to be about and the main point it will make. It gives the paragraph’s point straight away. Next – and largest – is the supporting sentences . These expand on the central idea, explaining it in more detail, exploring what it means, and of course giving the evidence and argument that back it up. This is where you use your research to support your argument. Then there is a concluding sentence . This restates the idea in the topic sentence, to remind the reader of your main point. It also shows how that point helps answer the question.

Pathways and Academic Learning Support

- << Previous: Introduction

- Next: Conclusion >>

- Last Updated: Nov 29, 2023 1:55 PM

- URL: https://libguides.newcastle.edu.au/how-to-write-an-essay

- The Writing Process

- Addressing the Prompt

- Writing Skill: Development

- Originality

- Timed Writing (Expectations)

- Integrated Writing (Writing Process)

- Introduction to Academic Essays

- Organization

- Introduction Paragraphs

Body Paragraphs

- Conclusion Paragraphs

- Example Essay 1

- Example Essay 2

- Timed Writing (The Prompt)

- Integrated Writing (TOEFL Task 1)

- Process Essays

- Process Essay Example 1

- Process Essay Example 2

- Writing Skill: Unity

- Revise A Process Essay

- Timed Writing (Choose a Position)

- Integrated Writing (TOEFL Task 2)

- Comparison Essays

- Comparison Essay Example 1

- Comparison Essay Example 2

- Writing Skill: Cohesion

- Revise A Comparison Essay

- Timed Writing (Plans & Problems)

- Integrated Writing (Word Choice)

- Problem/Solution Essays

- Problem/Solution Essay Example 1

- Problem/Solution Example Essay 2

- Writing Skill: Summary

- Revise A Problem/Solution Essay

- Timed Writing (Revising)

- Integrated Writing (Summary)

- More Writing Skills

- Punctuation

- Simple Sentences

- Compound Sentences

- Complex Sentences Part 1

- Complex Sentences Part 2

- Using Academic Vocabulary

- Translations

Choose a Sign-in Option

Tools and Settings

Questions and Tasks

Citation and Embed Code

Body paragraphs should all work to support your thesis by explaining why or how your thesis is true. There are three types of sentences in each body paragraph: topic sentences, supporting sentences, and concluding sentences.

Topic sentences

A topic sentence states the focus of the paragraph. The rest of the body paragraph will give evidence and explanations that show why or how your topic sentence is true. A topic sentence is very similar to a thesis. The thesis is the main idea of the essay; a topic sentence is the main idea of a body paragraph. Many of the same characteristics apply to topic sentences that apply to theses. The biggest differences will be the location of the sentence and the scope of the ideas.

An effective topic sentence—

- clearly supports the thesis statement.

- is usually at the beginning of a body paragraph.

- controls the content of all of the supporting sentences in its paragraph.

- is a complete sentence.

- does not announce the topic (e.g., “I’m going to talk about exercise.”).

- should not be t oo general (e.g., “Exercise is good.”).

- should not be too specific (e.g., “Exercise decreases the chance of developing diabetes, heart disease, asthma, osteoporosis, depression, and anxiety.”).

Supporting sentences

Your body paragraph needs to explain why or how your topic sentence is true. The sentences that support your topic sentence are called supporting sentences. You can have many types of supporting sentences. Supporting sentences can give examples, explanations, details, descriptions, facts, reasons, etc.

Concluding sentences

Your final statement should conclude your paragraph logically. Concluding sentences can restate the main idea of your paragraph, state an opinion, make a prediction, give advice, etc. New ideas should not be presented in your concluding sentence.

Exercise 1: Analyze a topic sentence.

Read the example body paragraph below to complete this exercise on a piece of paper.

Prompt: Why is exercise important?

Thesis: Exercise is essential because it improves overall physical and mental health.

Because it makes your body healthier, exercise is extremely important. One of the physical benefits of exercise is having stronger muscles. The only way to make your muscles stronger is to use them, and exercises like crunches, squats, lunges, push-ups, and weight-lifting are good examples of exercises that strengthen your muscles. Another benefit of exercise is that it lowers your heart rate. A slow heart rate can show that our hearts are working more efficiently and they don’t have to pump as many times in a minute to get blood to our organs. Related to our heart beating more efficiently, our blood pressure decreases. These are just some of the incredible health benefits of exercise.

Find the topic sentence. Use the following criteria to evaluate the topic sentence.

- Does the topic sentence clearly support the thesis statement?

- Is the topic sentence at the beginning of the body paragraph?

- Does the topic sentence control the content of all the supporting sentences?

- Is the topic sentence a complete sentence?

- Does the topic sentence announce the topic?

- Is the topic sentence too general? Is it too specific?

Exercise 2: Identify topic sentences.

Each group of sentences has three supporting sentences and one topic sentence. The topic sentence must be broad enough to include all of the supporting sentences. In each group of sentences, choose which sentence is the topic sentence. Write the letter of the topic sentence on the line given.

Group 1: Topic sentence: _________

- In southern Utah, hikers enjoy the scenic trails in Zion National Park.

- Many cities in Utah have created hiking trails in city parks for people to use.

- There are hiking paths in Utah’s Rocky Mountains that provide beautiful views.

- Hikers all over Utah can access hiking trails and enjoy nature.

Group 2: Topic sentence: _________

- People in New York speak many different languages.

- New York is a culturally diverse city.

- People in New York belong to many different religions.

- Restaurants in New York have food from all over the world.

Group 3: Topic sentence: _________

- Websites like YouTube have video tutorials that teach many different skills.

- Computer programs like PowerPoint are used in classrooms to teach new concepts.

- Technology helps people learn things in today’s world.

- Many educational apps have been created to help children in school.

Group 4: Topic sentence: _________

- Museums at BYU host events on the weekends for students.

- There are many fun activities for students at BYU on the weekends.

- There are incredible student concerts at BYU on Friday and Saturday nights.

- BYU clubs plan exciting activities for students to do on the weekends.

Group 5: Topic sentence: _________

- Some places have a scent that people remember when they think of that place.

- The smell of someone’s cologne can trigger a memory of that person.

- Smelling certain foods can bring back memories of eating that food.

- Many different memories can be connected to specific smells.

Exercise 3: Write topic sentences

Read each paragraph. On a piece of paper, write a topic sentence on the line at the beginning of the paragraph.

1._______ The first difference is that you have more privacy in a private room than in a shared room. You can go to your room to have a private phone call or Skype with your family and you are not bothered by other people. When you share your room, it can be hard to find private time when you can do things alone. Another difference is that it is lonelier in a private room than in a shared room. When you share your room with a roommate, you have someone that you can talk to. Frequently when you have a private room, you are alone more often. These two housing options are very different.

2. _______ People like to eat chocolate because it has many delicious flavors. For example, there are mint chocolates, milk chocolates, dark chocolates, white chocolates, chocolates with honey, and chocolates with nuts. Another reason people like to eat chocolate is because it reduces stress, which can help people to relax and feel better. The last reason people like to eat chocolate is because it can be cooked in many different ways. You can eat chocolate candies, mix chocolate with warm milk to drink, or prepare a chocolate dessert. These reasons are some of the reasons that people like to eat chocolate.

3. _______ A respectful roommate does not leave the main areas of the apartment messy after they use them. For example, they wash their dishes instead of leaving dirty pots and pans on the stove. They also don’t borrow things from other roommates without asking to use them first. In addition to respecting everyone’s need for space and their possessions, the ideal roommate is respectful of his or her roommate’s schedule. For example, if one roommate is asleep and the other roommates needs to study, the ideal roommate goes to the kitchen or living room instead of waking up the sleeping roommate. These simple gestures of respect make a roommate an excellent person to share an apartment with.

Exercise 4: Identify good supporting sentences.

Read the topic sentence. Then circle which sentences would be good supporting sentences.

Topic Sentence: Eating pancakes for breakfast saves time and money.