Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 11: Presenting Your Research

Writing a Research Report in American Psychological Association (APA) Style

Learning Objectives

- Identify the major sections of an APA-style research report and the basic contents of each section.

- Plan and write an effective APA-style research report.

In this section, we look at how to write an APA-style empirical research report , an article that presents the results of one or more new studies. Recall that the standard sections of an empirical research report provide a kind of outline. Here we consider each of these sections in detail, including what information it contains, how that information is formatted and organized, and tips for writing each section. At the end of this section is a sample APA-style research report that illustrates many of these principles.

Sections of a Research Report

Title page and abstract.

An APA-style research report begins with a title page . The title is centred in the upper half of the page, with each important word capitalized. The title should clearly and concisely (in about 12 words or fewer) communicate the primary variables and research questions. This sometimes requires a main title followed by a subtitle that elaborates on the main title, in which case the main title and subtitle are separated by a colon. Here are some titles from recent issues of professional journals published by the American Psychological Association.

- Sex Differences in Coping Styles and Implications for Depressed Mood

- Effects of Aging and Divided Attention on Memory for Items and Their Contexts

- Computer-Assisted Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Child Anxiety: Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial

- Virtual Driving and Risk Taking: Do Racing Games Increase Risk-Taking Cognitions, Affect, and Behaviour?

Below the title are the authors’ names and, on the next line, their institutional affiliation—the university or other institution where the authors worked when they conducted the research. As we have already seen, the authors are listed in an order that reflects their contribution to the research. When multiple authors have made equal contributions to the research, they often list their names alphabetically or in a randomly determined order.

In some areas of psychology, the titles of many empirical research reports are informal in a way that is perhaps best described as “cute.” They usually take the form of a play on words or a well-known expression that relates to the topic under study. Here are some examples from recent issues of the Journal Psychological Science .

- “Smells Like Clean Spirit: Nonconscious Effects of Scent on Cognition and Behavior”

- “Time Crawls: The Temporal Resolution of Infants’ Visual Attention”

- “Scent of a Woman: Men’s Testosterone Responses to Olfactory Ovulation Cues”

- “Apocalypse Soon?: Dire Messages Reduce Belief in Global Warming by Contradicting Just-World Beliefs”

- “Serial vs. Parallel Processing: Sometimes They Look Like Tweedledum and Tweedledee but They Can (and Should) Be Distinguished”

- “How Do I Love Thee? Let Me Count the Words: The Social Effects of Expressive Writing”

Individual researchers differ quite a bit in their preference for such titles. Some use them regularly, while others never use them. What might be some of the pros and cons of using cute article titles?

For articles that are being submitted for publication, the title page also includes an author note that lists the authors’ full institutional affiliations, any acknowledgments the authors wish to make to agencies that funded the research or to colleagues who commented on it, and contact information for the authors. For student papers that are not being submitted for publication—including theses—author notes are generally not necessary.

The abstract is a summary of the study. It is the second page of the manuscript and is headed with the word Abstract . The first line is not indented. The abstract presents the research question, a summary of the method, the basic results, and the most important conclusions. Because the abstract is usually limited to about 200 words, it can be a challenge to write a good one.

Introduction

The introduction begins on the third page of the manuscript. The heading at the top of this page is the full title of the manuscript, with each important word capitalized as on the title page. The introduction includes three distinct subsections, although these are typically not identified by separate headings. The opening introduces the research question and explains why it is interesting, the literature review discusses relevant previous research, and the closing restates the research question and comments on the method used to answer it.

The Opening

The opening , which is usually a paragraph or two in length, introduces the research question and explains why it is interesting. To capture the reader’s attention, researcher Daryl Bem recommends starting with general observations about the topic under study, expressed in ordinary language (not technical jargon)—observations that are about people and their behaviour (not about researchers or their research; Bem, 2003 [1] ). Concrete examples are often very useful here. According to Bem, this would be a poor way to begin a research report:

Festinger’s theory of cognitive dissonance received a great deal of attention during the latter part of the 20th century (p. 191)

The following would be much better:

The individual who holds two beliefs that are inconsistent with one another may feel uncomfortable. For example, the person who knows that he or she enjoys smoking but believes it to be unhealthy may experience discomfort arising from the inconsistency or disharmony between these two thoughts or cognitions. This feeling of discomfort was called cognitive dissonance by social psychologist Leon Festinger (1957), who suggested that individuals will be motivated to remove this dissonance in whatever way they can (p. 191).

After capturing the reader’s attention, the opening should go on to introduce the research question and explain why it is interesting. Will the answer fill a gap in the literature? Will it provide a test of an important theory? Does it have practical implications? Giving readers a clear sense of what the research is about and why they should care about it will motivate them to continue reading the literature review—and will help them make sense of it.

Breaking the Rules

Researcher Larry Jacoby reported several studies showing that a word that people see or hear repeatedly can seem more familiar even when they do not recall the repetitions—and that this tendency is especially pronounced among older adults. He opened his article with the following humourous anecdote:

A friend whose mother is suffering symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) tells the story of taking her mother to visit a nursing home, preliminary to her mother’s moving there. During an orientation meeting at the nursing home, the rules and regulations were explained, one of which regarded the dining room. The dining room was described as similar to a fine restaurant except that tipping was not required. The absence of tipping was a central theme in the orientation lecture, mentioned frequently to emphasize the quality of care along with the advantages of having paid in advance. At the end of the meeting, the friend’s mother was asked whether she had any questions. She replied that she only had one question: “Should I tip?” (Jacoby, 1999, p. 3)

Although both humour and personal anecdotes are generally discouraged in APA-style writing, this example is a highly effective way to start because it both engages the reader and provides an excellent real-world example of the topic under study.

The Literature Review

Immediately after the opening comes the literature review , which describes relevant previous research on the topic and can be anywhere from several paragraphs to several pages in length. However, the literature review is not simply a list of past studies. Instead, it constitutes a kind of argument for why the research question is worth addressing. By the end of the literature review, readers should be convinced that the research question makes sense and that the present study is a logical next step in the ongoing research process.

Like any effective argument, the literature review must have some kind of structure. For example, it might begin by describing a phenomenon in a general way along with several studies that demonstrate it, then describing two or more competing theories of the phenomenon, and finally presenting a hypothesis to test one or more of the theories. Or it might describe one phenomenon, then describe another phenomenon that seems inconsistent with the first one, then propose a theory that resolves the inconsistency, and finally present a hypothesis to test that theory. In applied research, it might describe a phenomenon or theory, then describe how that phenomenon or theory applies to some important real-world situation, and finally suggest a way to test whether it does, in fact, apply to that situation.

Looking at the literature review in this way emphasizes a few things. First, it is extremely important to start with an outline of the main points that you want to make, organized in the order that you want to make them. The basic structure of your argument, then, should be apparent from the outline itself. Second, it is important to emphasize the structure of your argument in your writing. One way to do this is to begin the literature review by summarizing your argument even before you begin to make it. “In this article, I will describe two apparently contradictory phenomena, present a new theory that has the potential to resolve the apparent contradiction, and finally present a novel hypothesis to test the theory.” Another way is to open each paragraph with a sentence that summarizes the main point of the paragraph and links it to the preceding points. These opening sentences provide the “transitions” that many beginning researchers have difficulty with. Instead of beginning a paragraph by launching into a description of a previous study, such as “Williams (2004) found that…,” it is better to start by indicating something about why you are describing this particular study. Here are some simple examples:

Another example of this phenomenon comes from the work of Williams (2004).

Williams (2004) offers one explanation of this phenomenon.

An alternative perspective has been provided by Williams (2004).

We used a method based on the one used by Williams (2004).

Finally, remember that your goal is to construct an argument for why your research question is interesting and worth addressing—not necessarily why your favourite answer to it is correct. In other words, your literature review must be balanced. If you want to emphasize the generality of a phenomenon, then of course you should discuss various studies that have demonstrated it. However, if there are other studies that have failed to demonstrate it, you should discuss them too. Or if you are proposing a new theory, then of course you should discuss findings that are consistent with that theory. However, if there are other findings that are inconsistent with it, again, you should discuss them too. It is acceptable to argue that the balance of the research supports the existence of a phenomenon or is consistent with a theory (and that is usually the best that researchers in psychology can hope for), but it is not acceptable to ignore contradictory evidence. Besides, a large part of what makes a research question interesting is uncertainty about its answer.

The Closing

The closing of the introduction—typically the final paragraph or two—usually includes two important elements. The first is a clear statement of the main research question or hypothesis. This statement tends to be more formal and precise than in the opening and is often expressed in terms of operational definitions of the key variables. The second is a brief overview of the method and some comment on its appropriateness. Here, for example, is how Darley and Latané (1968) [2] concluded the introduction to their classic article on the bystander effect:

These considerations lead to the hypothesis that the more bystanders to an emergency, the less likely, or the more slowly, any one bystander will intervene to provide aid. To test this proposition it would be necessary to create a situation in which a realistic “emergency” could plausibly occur. Each subject should also be blocked from communicating with others to prevent his getting information about their behaviour during the emergency. Finally, the experimental situation should allow for the assessment of the speed and frequency of the subjects’ reaction to the emergency. The experiment reported below attempted to fulfill these conditions. (p. 378)

Thus the introduction leads smoothly into the next major section of the article—the method section.

The method section is where you describe how you conducted your study. An important principle for writing a method section is that it should be clear and detailed enough that other researchers could replicate the study by following your “recipe.” This means that it must describe all the important elements of the study—basic demographic characteristics of the participants, how they were recruited, whether they were randomly assigned, how the variables were manipulated or measured, how counterbalancing was accomplished, and so on. At the same time, it should avoid irrelevant details such as the fact that the study was conducted in Classroom 37B of the Industrial Technology Building or that the questionnaire was double-sided and completed using pencils.

The method section begins immediately after the introduction ends with the heading “Method” (not “Methods”) centred on the page. Immediately after this is the subheading “Participants,” left justified and in italics. The participants subsection indicates how many participants there were, the number of women and men, some indication of their age, other demographics that may be relevant to the study, and how they were recruited, including any incentives given for participation.

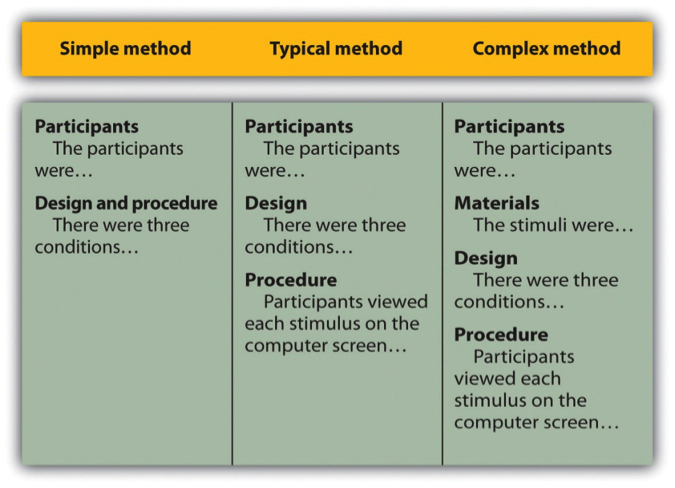

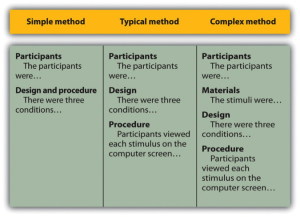

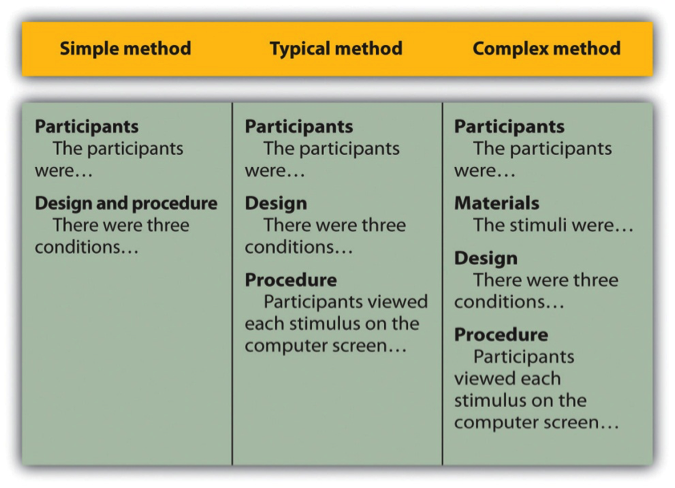

After the participants section, the structure can vary a bit. Figure 11.1 shows three common approaches. In the first, the participants section is followed by a design and procedure subsection, which describes the rest of the method. This works well for methods that are relatively simple and can be described adequately in a few paragraphs. In the second approach, the participants section is followed by separate design and procedure subsections. This works well when both the design and the procedure are relatively complicated and each requires multiple paragraphs.

What is the difference between design and procedure? The design of a study is its overall structure. What were the independent and dependent variables? Was the independent variable manipulated, and if so, was it manipulated between or within subjects? How were the variables operationally defined? The procedure is how the study was carried out. It often works well to describe the procedure in terms of what the participants did rather than what the researchers did. For example, the participants gave their informed consent, read a set of instructions, completed a block of four practice trials, completed a block of 20 test trials, completed two questionnaires, and were debriefed and excused.

In the third basic way to organize a method section, the participants subsection is followed by a materials subsection before the design and procedure subsections. This works well when there are complicated materials to describe. This might mean multiple questionnaires, written vignettes that participants read and respond to, perceptual stimuli, and so on. The heading of this subsection can be modified to reflect its content. Instead of “Materials,” it can be “Questionnaires,” “Stimuli,” and so on.

The results section is where you present the main results of the study, including the results of the statistical analyses. Although it does not include the raw data—individual participants’ responses or scores—researchers should save their raw data and make them available to other researchers who request them. Several journals now encourage the open sharing of raw data online.

Although there are no standard subsections, it is still important for the results section to be logically organized. Typically it begins with certain preliminary issues. One is whether any participants or responses were excluded from the analyses and why. The rationale for excluding data should be described clearly so that other researchers can decide whether it is appropriate. A second preliminary issue is how multiple responses were combined to produce the primary variables in the analyses. For example, if participants rated the attractiveness of 20 stimulus people, you might have to explain that you began by computing the mean attractiveness rating for each participant. Or if they recalled as many items as they could from study list of 20 words, did you count the number correctly recalled, compute the percentage correctly recalled, or perhaps compute the number correct minus the number incorrect? A third preliminary issue is the reliability of the measures. This is where you would present test-retest correlations, Cronbach’s α, or other statistics to show that the measures are consistent across time and across items. A final preliminary issue is whether the manipulation was successful. This is where you would report the results of any manipulation checks.

The results section should then tackle the primary research questions, one at a time. Again, there should be a clear organization. One approach would be to answer the most general questions and then proceed to answer more specific ones. Another would be to answer the main question first and then to answer secondary ones. Regardless, Bem (2003) [3] suggests the following basic structure for discussing each new result:

- Remind the reader of the research question.

- Give the answer to the research question in words.

- Present the relevant statistics.

- Qualify the answer if necessary.

- Summarize the result.

Notice that only Step 3 necessarily involves numbers. The rest of the steps involve presenting the research question and the answer to it in words. In fact, the basic results should be clear even to a reader who skips over the numbers.

The discussion is the last major section of the research report. Discussions usually consist of some combination of the following elements:

- Summary of the research

- Theoretical implications

- Practical implications

- Limitations

- Suggestions for future research

The discussion typically begins with a summary of the study that provides a clear answer to the research question. In a short report with a single study, this might require no more than a sentence. In a longer report with multiple studies, it might require a paragraph or even two. The summary is often followed by a discussion of the theoretical implications of the research. Do the results provide support for any existing theories? If not, how can they be explained? Although you do not have to provide a definitive explanation or detailed theory for your results, you at least need to outline one or more possible explanations. In applied research—and often in basic research—there is also some discussion of the practical implications of the research. How can the results be used, and by whom, to accomplish some real-world goal?

The theoretical and practical implications are often followed by a discussion of the study’s limitations. Perhaps there are problems with its internal or external validity. Perhaps the manipulation was not very effective or the measures not very reliable. Perhaps there is some evidence that participants did not fully understand their task or that they were suspicious of the intent of the researchers. Now is the time to discuss these issues and how they might have affected the results. But do not overdo it. All studies have limitations, and most readers will understand that a different sample or different measures might have produced different results. Unless there is good reason to think they would have, however, there is no reason to mention these routine issues. Instead, pick two or three limitations that seem like they could have influenced the results, explain how they could have influenced the results, and suggest ways to deal with them.

Most discussions end with some suggestions for future research. If the study did not satisfactorily answer the original research question, what will it take to do so? What new research questions has the study raised? This part of the discussion, however, is not just a list of new questions. It is a discussion of two or three of the most important unresolved issues. This means identifying and clarifying each question, suggesting some alternative answers, and even suggesting ways they could be studied.

Finally, some researchers are quite good at ending their articles with a sweeping or thought-provoking conclusion. Darley and Latané (1968) [4] , for example, ended their article on the bystander effect by discussing the idea that whether people help others may depend more on the situation than on their personalities. Their final sentence is, “If people understand the situational forces that can make them hesitate to intervene, they may better overcome them” (p. 383). However, this kind of ending can be difficult to pull off. It can sound overreaching or just banal and end up detracting from the overall impact of the article. It is often better simply to end when you have made your final point (although you should avoid ending on a limitation).

The references section begins on a new page with the heading “References” centred at the top of the page. All references cited in the text are then listed in the format presented earlier. They are listed alphabetically by the last name of the first author. If two sources have the same first author, they are listed alphabetically by the last name of the second author. If all the authors are the same, then they are listed chronologically by the year of publication. Everything in the reference list is double-spaced both within and between references.

Appendices, Tables, and Figures

Appendices, tables, and figures come after the references. An appendix is appropriate for supplemental material that would interrupt the flow of the research report if it were presented within any of the major sections. An appendix could be used to present lists of stimulus words, questionnaire items, detailed descriptions of special equipment or unusual statistical analyses, or references to the studies that are included in a meta-analysis. Each appendix begins on a new page. If there is only one, the heading is “Appendix,” centred at the top of the page. If there is more than one, the headings are “Appendix A,” “Appendix B,” and so on, and they appear in the order they were first mentioned in the text of the report.

After any appendices come tables and then figures. Tables and figures are both used to present results. Figures can also be used to illustrate theories (e.g., in the form of a flowchart), display stimuli, outline procedures, and present many other kinds of information. Each table and figure appears on its own page. Tables are numbered in the order that they are first mentioned in the text (“Table 1,” “Table 2,” and so on). Figures are numbered the same way (“Figure 1,” “Figure 2,” and so on). A brief explanatory title, with the important words capitalized, appears above each table. Each figure is given a brief explanatory caption, where (aside from proper nouns or names) only the first word of each sentence is capitalized. More details on preparing APA-style tables and figures are presented later in the book.

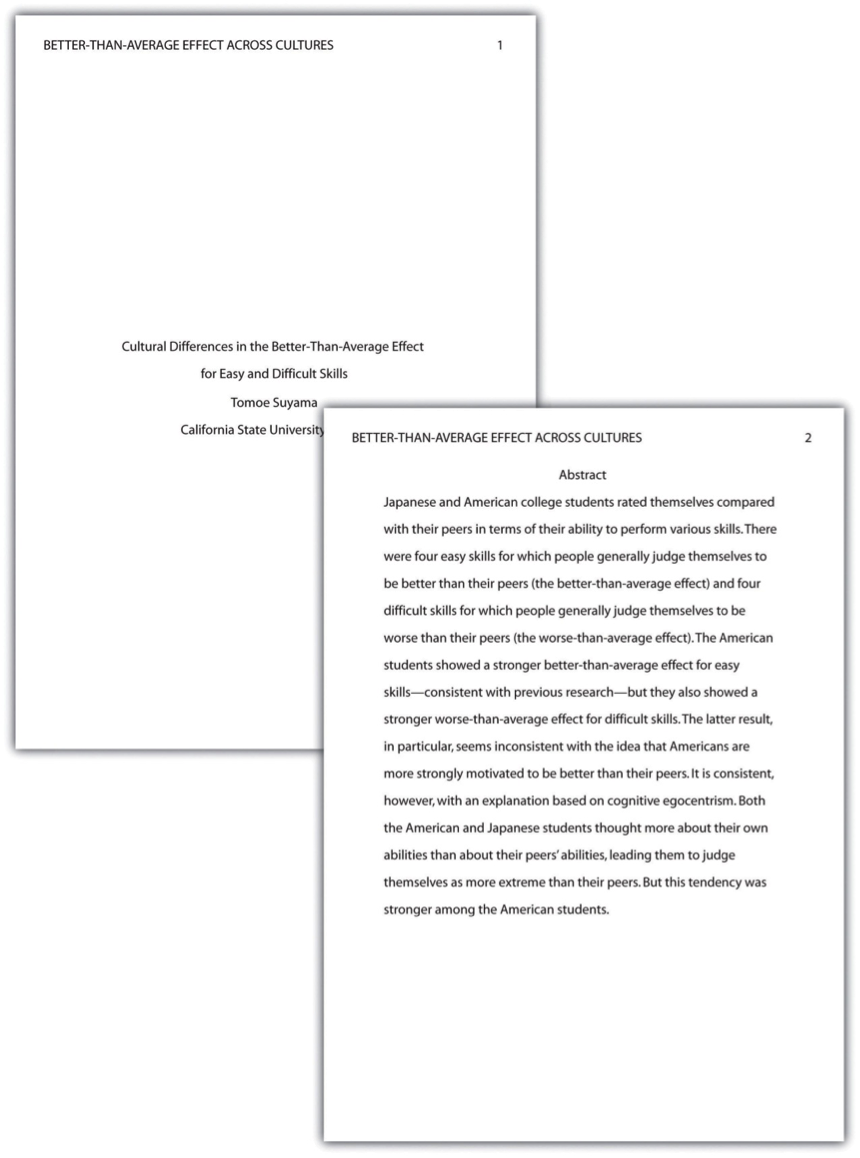

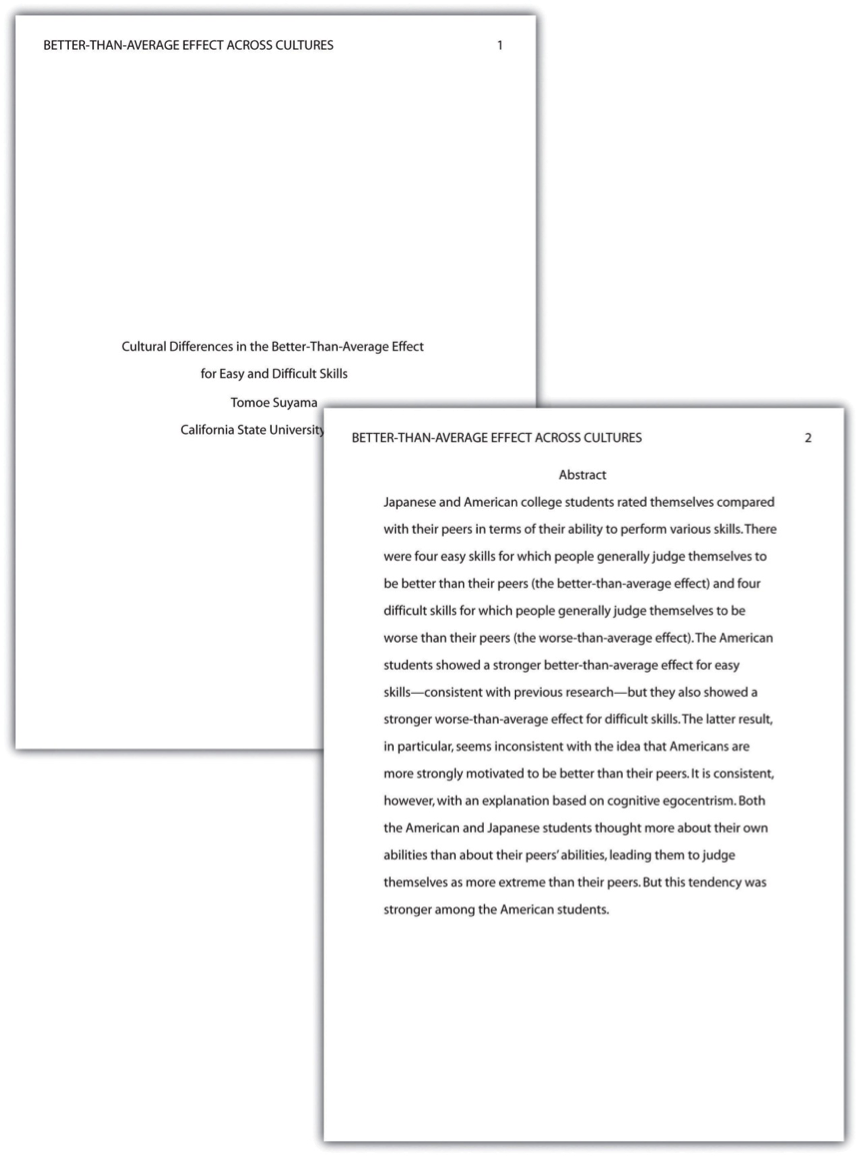

Sample APA-Style Research Report

Figures 11.2, 11.3, 11.4, and 11.5 show some sample pages from an APA-style empirical research report originally written by undergraduate student Tomoe Suyama at California State University, Fresno. The main purpose of these figures is to illustrate the basic organization and formatting of an APA-style empirical research report, although many high-level and low-level style conventions can be seen here too.

Key Takeaways

- An APA-style empirical research report consists of several standard sections. The main ones are the abstract, introduction, method, results, discussion, and references.

- The introduction consists of an opening that presents the research question, a literature review that describes previous research on the topic, and a closing that restates the research question and comments on the method. The literature review constitutes an argument for why the current study is worth doing.

- The method section describes the method in enough detail that another researcher could replicate the study. At a minimum, it consists of a participants subsection and a design and procedure subsection.

- The results section describes the results in an organized fashion. Each primary result is presented in terms of statistical results but also explained in words.

- The discussion typically summarizes the study, discusses theoretical and practical implications and limitations of the study, and offers suggestions for further research.

- Practice: Look through an issue of a general interest professional journal (e.g., Psychological Science ). Read the opening of the first five articles and rate the effectiveness of each one from 1 ( very ineffective ) to 5 ( very effective ). Write a sentence or two explaining each rating.

- Practice: Find a recent article in a professional journal and identify where the opening, literature review, and closing of the introduction begin and end.

- Practice: Find a recent article in a professional journal and highlight in a different colour each of the following elements in the discussion: summary, theoretical implications, practical implications, limitations, and suggestions for future research.

Long Descriptions

Figure 11.1 long description: Table showing three ways of organizing an APA-style method section.

In the simple method, there are two subheadings: “Participants” (which might begin “The participants were…”) and “Design and procedure” (which might begin “There were three conditions…”).

In the typical method, there are three subheadings: “Participants” (“The participants were…”), “Design” (“There were three conditions…”), and “Procedure” (“Participants viewed each stimulus on the computer screen…”).

In the complex method, there are four subheadings: “Participants” (“The participants were…”), “Materials” (“The stimuli were…”), “Design” (“There were three conditions…”), and “Procedure” (“Participants viewed each stimulus on the computer screen…”). [Return to Figure 11.1]

- Bem, D. J. (2003). Writing the empirical journal article. In J. M. Darley, M. P. Zanna, & H. R. Roediger III (Eds.), The compleat academic: A practical guide for the beginning social scientist (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. ↵

- Darley, J. M., & Latané, B. (1968). Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4 , 377–383. ↵

A type of research article which describes one or more new empirical studies conducted by the authors.

The page at the beginning of an APA-style research report containing the title of the article, the authors’ names, and their institutional affiliation.

A summary of a research study.

The third page of a manuscript containing the research question, the literature review, and comments about how to answer the research question.

An introduction to the research question and explanation for why this question is interesting.

A description of relevant previous research on the topic being discusses and an argument for why the research is worth addressing.

The end of the introduction, where the research question is reiterated and the method is commented upon.

The section of a research report where the method used to conduct the study is described.

The main results of the study, including the results from statistical analyses, are presented in a research article.

Section of a research report that summarizes the study's results and interprets them by referring back to the study's theoretical background.

Part of a research report which contains supplemental material.

Research Methods in Psychology - 2nd Canadian Edition Copyright © 2015 by Paul C. Price, Rajiv Jhangiani, & I-Chant A. Chiang is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Lab Report Format: Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

In psychology, a lab report outlines a study’s objectives, methods, results, discussion, and conclusions, ensuring clarity and adherence to APA (or relevant) formatting guidelines.

A typical lab report would include the following sections: title, abstract, introduction, method, results, and discussion.

The title page, abstract, references, and appendices are started on separate pages (subsections from the main body of the report are not). Use double-line spacing of text, font size 12, and include page numbers.

The report should have a thread of arguments linking the prediction in the introduction to the content of the discussion.

This must indicate what the study is about. It must include the variables under investigation. It should not be written as a question.

Title pages should be formatted in APA style .

The abstract provides a concise and comprehensive summary of a research report. Your style should be brief but not use note form. Look at examples in journal articles . It should aim to explain very briefly (about 150 words) the following:

- Start with a one/two sentence summary, providing the aim and rationale for the study.

- Describe participants and setting: who, when, where, how many, and what groups?

- Describe the method: what design, what experimental treatment, what questionnaires, surveys, or tests were used.

- Describe the major findings, including a mention of the statistics used and the significance levels, or simply one sentence summing up the outcome.

- The final sentence(s) outline the study’s “contribution to knowledge” within the literature. What does it all mean? Mention the implications of your findings if appropriate.

The abstract comes at the beginning of your report but is written at the end (as it summarises information from all the other sections of the report).

Introduction

The purpose of the introduction is to explain where your hypothesis comes from (i.e., it should provide a rationale for your research study).

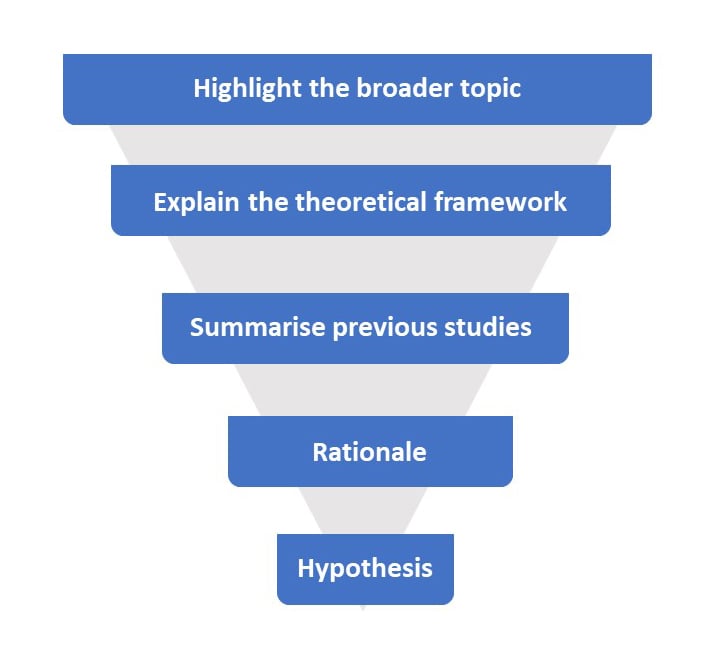

Ideally, the introduction should have a funnel structure: Start broad and then become more specific. The aims should not appear out of thin air; the preceding review of psychological literature should lead logically into the aims and hypotheses.

- Start with general theory, briefly introducing the topic. Define the important key terms.

- Explain the theoretical framework.

- Summarise and synthesize previous studies – What was the purpose? Who were the participants? What did they do? What did they find? What do these results mean? How do the results relate to the theoretical framework?

- Rationale: How does the current study address a gap in the literature? Perhaps it overcomes a limitation of previous research.

- Aims and hypothesis. Write a paragraph explaining what you plan to investigate and make a clear and concise prediction regarding the results you expect to find.

There should be a logical progression of ideas that aids the flow of the report. This means the studies outlined should lead logically to your aims and hypotheses.

Do be concise and selective, and avoid the temptation to include anything in case it is relevant (i.e., don’t write a shopping list of studies).

USE THE FOLLOWING SUBHEADINGS:

Participants

- How many participants were recruited?

- Say how you obtained your sample (e.g., opportunity sample).

- Give relevant demographic details (e.g., gender, ethnicity, age range, mean age, and standard deviation).

- State the experimental design .

- What were the independent and dependent variables ? Make sure the independent variable is labeled and name the different conditions/levels.

- For example, if gender is the independent variable label, then male and female are the levels/conditions/groups.

- How were the IV and DV operationalized?

- Identify any controls used, e.g., counterbalancing and control of extraneous variables.

- List all the materials and measures (e.g., what was the title of the questionnaire? Was it adapted from a study?).

- You do not need to include wholesale replication of materials – instead, include a ‘sensible’ (illustrate) level of detail. For example, give examples of questionnaire items.

- Include the reliability (e.g., alpha values) for the measure(s).

- Describe the precise procedure you followed when conducting your research, i.e., exactly what you did.

- Describe in sufficient detail to allow for replication of findings.

- Be concise in your description and omit extraneous/trivial details, e.g., you don’t need to include details regarding instructions, debrief, record sheets, etc.

- Assume the reader has no knowledge of what you did and ensure that he/she can replicate (i.e., copy) your study exactly by what you write in this section.

- Write in the past tense.

- Don’t justify or explain in the Method (e.g., why you chose a particular sampling method); just report what you did.

- Only give enough detail for someone to replicate the experiment – be concise in your writing.

- The results section of a paper usually presents descriptive statistics followed by inferential statistics.

- Report the means, standard deviations, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each IV level. If you have four to 20 numbers to present, a well-presented table is best, APA style.

- Name the statistical test being used.

- Report appropriate statistics (e.g., t-scores, p values ).

- Report the magnitude (e.g., are the results significant or not?) as well as the direction of the results (e.g., which group performed better?).

- It is optional to report the effect size (this does not appear on the SPSS output).

- Avoid interpreting the results (save this for the discussion).

- Make sure the results are presented clearly and concisely. A table can be used to display descriptive statistics if this makes the data easier to understand.

- DO NOT include any raw data.

- Follow APA style.

Use APA Style

- Numbers reported to 2 d.p. (incl. 0 before the decimal if 1.00, e.g., “0.51”). The exceptions to this rule: Numbers which can never exceed 1.0 (e.g., p -values, r-values): report to 3 d.p. and do not include 0 before the decimal place, e.g., “.001”.

- Percentages and degrees of freedom: report as whole numbers.

- Statistical symbols that are not Greek letters should be italicized (e.g., M , SD , t , X 2 , F , p , d ).

- Include spaces on either side of the equals sign.

- When reporting 95%, CIs (confidence intervals), upper and lower limits are given inside square brackets, e.g., “95% CI [73.37, 102.23]”

- Outline your findings in plain English (avoid statistical jargon) and relate your results to your hypothesis, e.g., is it supported or rejected?

- Compare your results to background materials from the introduction section. Are your results similar or different? Discuss why/why not.

- How confident can we be in the results? Acknowledge limitations, but only if they can explain the result obtained. If the study has found a reliable effect, be very careful suggesting limitations as you are doubting your results. Unless you can think of any c onfounding variable that can explain the results instead of the IV, it would be advisable to leave the section out.

- Suggest constructive ways to improve your study if appropriate.

- What are the implications of your findings? Say what your findings mean for how people behave in the real world.

- Suggest an idea for further research triggered by your study, something in the same area but not simply an improved version of yours. Perhaps you could base this on a limitation of your study.

- Concluding paragraph – Finish with a statement of your findings and the key points of the discussion (e.g., interpretation and implications) in no more than 3 or 4 sentences.

Reference Page

The reference section lists all the sources cited in the essay (alphabetically). It is not a bibliography (a list of the books you used).

In simple terms, every time you refer to a psychologist’s name (and date), you need to reference the original source of information.

If you have been using textbooks this is easy as the references are usually at the back of the book and you can just copy them down. If you have been using websites then you may have a problem as they might not provide a reference section for you to copy.

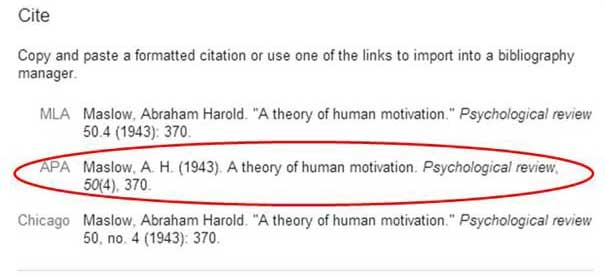

References need to be set out APA style :

Author, A. A. (year). Title of work . Location: Publisher.

Journal Articles

Author, A. A., Author, B. B., & Author, C. C. (year). Article title. Journal Title, volume number (issue number), page numbers

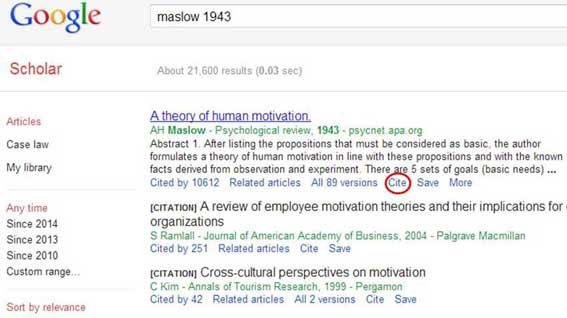

A simple way to write your reference section is to use Google scholar . Just type the name and date of the psychologist in the search box and click on the “cite” link.

Next, copy and paste the APA reference into the reference section of your essay.

Once again, remember that references need to be in alphabetical order according to surname.

Psychology Lab Report Example

Quantitative paper template.

Quantitative professional paper template: Adapted from “Fake News, Fast and Slow: Deliberation Reduces Belief in False (but Not True) News Headlines,” by B. Bago, D. G. Rand, and G. Pennycook, 2020, Journal of Experimental Psychology: General , 149 (8), pp. 1608–1613 ( https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000729 ). Copyright 2020 by the American Psychological Association.

Qualitative paper template

Qualitative professional paper template: Adapted from “‘My Smartphone Is an Extension of Myself’: A Holistic Qualitative Exploration of the Impact of Using a Smartphone,” by L. J. Harkin and D. Kuss, 2020, Psychology of Popular Media , 10 (1), pp. 28–38 ( https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000278 ). Copyright 2020 by the American Psychological Association.

Psychological Report Writing

March 8, 2021 - paper 2 psychology in context | research methods.

- Back to Paper 2 - Research Methods

Writing up Psychological Investigations

Through using this website, you have learned about, referred to, and evaluated research studies. These research studies are generally presented to the scientific community as a journal article. Most journal articles follow a standard format. This is similar to the way you may have written up experiments in other sciences.

In research report there are usually six sub-sections:

(1) Abstract: This is always written last because it is a very brief summary:

- Include a one sentence summary, giving the topic to be studied. This may include the hypothesis and some brief theoretical background research, for example the name of the researchers whose work you have replicated.

- Describe the participants, number used and how they were selected.

- Describe the method and design used and any questionnaires etc. you employed.

- State your major findings, which should include a mention of the statistics used the observed and critical values and whether or not your results were found to be significant, including the level of significance

- Briefly summarise what your study shows, the conclusion of your findings and any implications it may have. State whether the experimental or null hypothesis has been accepted/rejected.

- This should be around 150 words.

(2) Introduction:

This tells everyone why the study is being carried out and the commentary should form a ‘funnel’ of information. First, there is broad coverage of all the background research with appropriate evaluative comments: “Asch (1951) found…but Crutchfield (1955) showed…” Once the general research has been covered, the focus becomes much narrower finishing with the main researcher/research area you are hoping to support/refute. This then leads to the aims and hypothesis/hypotheses (i.e. experimental and null hypotheses) being stated.

(3) Method:

Method – this section is split into sub-sections:

(1) Design:

- What is the experimental method that has been used?

- Experimental Design type independent groups, repeated measures, matched pairs? Justify?

- What is the IV, DV? These should be operationalised.

- Any potential EVs?

- How will these EVs be overcome?

- Ethical issues? Strategies to overcome these ethical issues

(2) Participants:

- Who is the target population? Age/socio-economic status, gender, etc.

- What sampling technique has been used? Why?

- Details of participants that have been used? Do they have certain characteristics

- How have participants been allocated to conditions

(3) Materials:

- Description of all equipment used and how to use it (essential for replication)

- Stimulus materials for participants should be in the appendix

(4) Procedure:

- This is a step-by-step guide of how the study was carried out when, where, how

- Instructions to participants must be standardised to allow replication

- Lengthy sets of instructions and instructions to participants should be in the appendix

(4) Results:

This section contains:

- A summary of the data. All raw data and calculations are put in the appendix.

- This generally starts with a section of descriptive statistics measures of central tendency and dispersion.

- Summary tables, which should be clearly labelled and referred to in the text, e.g., “Table One shows that…” Graphical representations of the data must also be clear and properly labelled and referred to in the text, e.g., “It can be seen from Figure 1 that…”

- Once the summary statistics have been explained, there should be an analysis of the results of any inferential tests, including observed values, how these relate to the critical table value, significance level and whether the test was one- or two-tailed.

- This section finishes with the rejection or acceptance of the null hypothesis.

(5) Discussion:

This sounds like a repeat of the results section, but here you need to state what you’ve found in terms of psychology rather than in statistical terms, in particular relate your findings to your hypotheses. Mention the strength of your findings, for example were they significant and at what level. If your hypothesis was one tailed and your results have gone in the opposite direction this needs to be indicated. If you have any additional findings to report, other than those relating to the hypotheses then they too can be included.

All studies have flaws, so anything that went wrong or the limitations of the study are discussed together with suggestions for how it could be improved if it were to be repeated. Suggestions for alternative studies and future research are also explored. The discussion ends with a paragraph summing up what was found and assessing the implications of the study and any conclusions that can be drawn from it.

(6) Referencing (Harvard Referencing):

References should contain details of all the research covered in a psychological report. It is not sufficient to simply list the books used.

What you should do:

Look through your report and include a reference every researcher mentioned. A reference should include; the name of the researcher, the date the research was published, the title of the book/journal, where the book was published (or what journal the article was published in), the edition number of the book/volume of the journal article, the page numbers used.

Example: Paivio, A., Madigan, S.A. (1970). Noun imagery and frequency in paired-associate and free learning recall. Canadian Journal of Psychology. 24, pp353-361.

Other Rules Make sure that the references are placed in alphabetical order.

Exam Tip: In the exam, the types of questions you could expect relating to report writing include; defining what information you would find in each section of the report, in addition, on the old specification, questions linked to report writing have included; writing up a method section, results section and designing a piece of research.

In addition, in the exam, you may get asked to write; a consent form , debriefing sheet or a set of standardised instructions.

Writing a Consent Form for a Psychological Report Remember the mnemonic TAPCHIPS

Your consent form should include the following;

(1) T itle of the Project:

(2) A im of the study?

(3) P rocedure – What will I be asked to do if I take part?

You should give a brief description of what the participants will have to do if they decide to consent to take part in the study (i.e. complete a 15-minute memory test etc )

(4) Will your data be kept C onfidential?

Explain how you will make sure that all personal details will be kept confidential.

(5) Do I H ave to take part?

Explain to the participant that they don’t have to take part in the study, explain about their right to withdraw.

(6) I nformation? Where can I obtained further information if I need it?

Provide the participant with the contact details of the key researchers carrying out the study.

(7) P articipant responses to the following questions:

Have you received enough information about the study? YES/NO

Do you consent for your data to be used in this study and retained for use in other studies? YES/NO

Do you understand that you do not need to take part in the study and that you can; withdraw your participation at any time without reason or detriment? YES/NO

(8) S ignature from the participant and the researcher: will need to be acquired at the bottom of the consent form.

Writing a set of Standardised Instructions for a Psychological Investigation

When writing a set of standardised instructions, it is essential that you include:

1. Enough information to allow for replication of the study

2. You must write the instructions so that they can simply be read out by the researcher to the participants.

3. You should welcome the participants to the study.

4. Thank the participants for giving their consent to take part.

5. Explain to the participants what will happen in the study, what they will be expected to do (step by step), how long the task/specific parts of the task will take to complete.

6. Remind participants that they have the right to withdraw throughout the study.

7. Ask that participants at the end if they have any questions

8. Check that the participants are still happy to proceed with the study.

Writing a Debriefing Form for a Psychological Report

This is the form that you should complete with your participants at the end of the study to ensure that they are happy with the way the study has been conducted, to explain to them the true nature of the study, to confirm consent and to give them the researcher’s contact details in case they want to ask any further questions.

- Thank the participants for taking part in the study.

- Outline the true aims of the research (what were the participants expected to do? What happened in each of the different conditions?)

- Explain what you were looking to find.

- Explain how the data will be used now and in the future.

- Remind the participants that they have the right to withdraw now and after the study.

- Thank participants once again for taking part.

- Remind the participant of the researcher(s) contact details.

Designing Research

One of the questions that you may get asked in the exam is to design a piece of research. The best way to go about this is to include similar information to what you would when writing up the method section of a psychological report.

Things to Consider…

- What is the experimental method/non-experimental method will you use? ( Lab, field, natural experiment? Questionnaire (open/closed questions?), Interviews (structured, unstructured, semi-structured?), Observation).

- Why? ( does this method allow a great deal of control? Is it in a natural setting and would show behaviour reflective of real life? Would it allow participants to remain anonymous and therefore, they are more likely to tell the truth/act in a realistic way? Does the method avoid demand characteristics?)

- Experimental Design type ( independent groups, repeated measures, matched pairs? Justify you choice?)

- What is the IV, DV? These should be operationalised ( how are you going to measure these variables?)

- Any potential EVs? ( Participant variables, experimenter effects, demand characteristics, situational variables?)

- How will these EVs be overcome? ( Are you going to out some control mechanisms in place? Are you going to use standardised instructions? Double or single blind? Will the experimental design that you are using help to overcome EVs?)

- Ethical issues? ( What are the potential ethical issues and what strategies are you going to use to overcome these ethical issues?)

- Who is the target population? Age/socio-economic status, gender, etc.

- How have participants been allocated to conditions ( have you used random allocation? Why have you adopted this technique?

- This is a step-by-step guide of how the study was carried out – from beginning to end, how are you going to carry out the study.

- Psychopathology

- Social Psychology

- Approaches To Human Behaviour

- Biopsychology

- Research Methods

- Issues & Debates

- Teacher Hub

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- [email protected]

- www.psychologyhub.co.uk

We're not around right now. But you can send us an email and we'll get back to you, asap.

Start typing and press Enter to search

Cookie Policy - Terms and Conditions - Privacy Policy

- Search This Site All UCSD Sites Faculty/Staff Search Term

- Contact & Directions

- Climate Statement

- Cognitive Behavioral Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Adjunct Faculty

- Non-Senate Instructors

- Researchers

- Psychology Grads

- Affiliated Grads

- New and Prospective Students

- Honors Program

- Experiential Learning

- Programs & Events

- Psi Chi / Psychology Club

- Prospective PhD Students

- Current PhD Students

- Area Brown Bags

- Colloquium Series

- Anderson Distinguished Lecture Series

- Speaker Videos

- Undergraduate Program

Academic and Writing Resources

- Writing Research Papers

Writing Research Papers

Information and resources.

One of the most important skills that you can learn in this department is how to write a research paper. For many of you, this will be in fulfillment of the Psychology B.S. Degree Research Paper requirement and/or the Psychology Honors Program Thesis requirement. You may also be writing an American Psychological Association (APA) formatted research paper for a Psychology course (such as a term paper or a summary of an empirical research paper). In some cases, such as for certain job, graduate school, and fellowship applications, you may be asked to provide a writing sample; a well-written research paper can be ideal for that purpose. The ability to write research papers is crucial for those who wish to pursue graduate school and research careers. To assist with these potential goals, we’ve gathered important information and helpful tips for you.

Should I Use a Specific Format and Style?

In the psychological sciences, it is common for research papers to adhere to the guidelines of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (papers in other fields often use APA format as well). APA guidelines not only specify the types of sections that a research paper should have, but also the order of those sections, the manner in which scholarly sources should be cited in the text and in a separate references section, appropriate methods of reporting experimental and statistical results, the proper use of language, and other details. A well-written psychology research paper typically follows those guidelines .

How to Write a Successful Research Paper in APA Style

For more information on writing research papers in APA style, please checking out the following pages. Here you’ll find details on multiple aspects of the research paper writing process, ranging from how the paper should be structured to how to write more effectively.

- Structure and Format – the critical components of each section of an APA-formatted research paper (Introduction, Methods, and on), as well as how those sections should be formatted according to APA guidelines.

► Structure of Research Papers in APA Style

► Formatting Research Papers in APA Style

- Finding, Evaluating, and Citing References – how to search databases, how to obtain references, how to take notes when reading references, what types of references to use, how to include in-text citations, and how to create an APA-formatted reference list.

► Using Databases and Finding References

► What Types of References Are Appropriate for Research Papers?

► Evaluating References and Taking Notes

► Citing References in APA Style

- Writing a Literature Review, the Writing Process, and Improving Writing – how to write a literature review (an overview or summary of prior research, which is a common technique of introducing a research topic in the early sections of a paper), as well as recommendations for the writing process, improving clarity and conciseness, examples of adequate and better paragraphs, and links to resources on improving writing.

► Writing Literature Reviews

► Writing Process and Revising

► Improving Scientific Writing

- Avoiding Plagiarism – how to make sure that your research paper represents your writing and ideas and does not erroneously or unethically appropriate the works of others.

► Academic Integrity and Avoiding Plagiarism

- How-To Videos – for video guides to the different major sections of research papers, plus literature reviews and references, please see the following:

► Writing Research Papers Videos

In addition, you may be interested in downloading “ How to Write a Research Paper in APA Style ”, a comprehensive guide developed by Prof. Emma Geller, “ Tips for Writing APA Style Research Papers ” (a short summary of multiple aspects of the paper-writing process), and an Example B.S. Degree Research Paper written in APA Style .

Workshops and Downloadable Resources

- For in-person discussion of the process of writing research papers, please consider attending this department’s “Writing Research Papers” workshop (for dates and times, please check the undergraduate workshops calendar).

- How to Write APA Style Research Papers (a comprehensive guide) [ PDF ]

- Tips for Writing APA Style Research Papers (a brief summary) [ PDF ]

- Example APA Style Research Paper (for B.S. Degree – empirical research) [ PDF ]

- Example APA Style Research Paper (for B.S. Degree – literature review) [ PDF ]

Further Resources

- OASIS Language and Writing Program

- UCSD Writing Programs and Resources

- UCSD Muir College Writing Hub

- UCSD Writing Hub

External Resources

- APA Style Guide from the Purdue University Online Writing Lab (OWL)

- APA Tutorial on the Basics of APA Style

- EasyBib Guide to Writing and Citing in APA Format

- Formatting APA Style Papers in Microsoft Word

- How to Write an APA Style Research Paper from Hamilton University

- Online Learning: Plagiarism and Paraphrasing

- Sample APA Formatted Paper with Comments

- Sample APA Formatted Paper

- Tips for Writing a Paper in APA Style

- WikiHow Guide to Writing APA Research Papers

Back to top

- Research Paper Structure

- Formatting Research Papers

- Using Databases and Finding References

- What Types of References Are Appropriate?

- Evaluating References and Taking Notes

- Citing References

- Writing a Literature Review

- Writing Process and Revising

- Improving Scientific Writing

- Academic Integrity and Avoiding Plagiarism

- Writing Research Papers Videos

- Effective Studying

11.2 Writing a Research Report in American Psychological Association (APA) Style

Learning objectives.

- Identify the major sections of an APA-style research report and the basic contents of each section.

- Plan and write an effective APA-style research report.

In this section, we look at how to write an APA-style empirical research report A type of journal article in which the author reports on a new empirical research study. , an article that presents the results of one or more new studies. Recall that the standard sections of an empirical research report provide a kind of outline. Here we consider each of these sections in detail, including what information it contains, how that information is formatted and organized, and tips for writing each section. At the end of this section is a sample APA-style research report that illustrates many of these principles.

Sections of a Research Report

Title page and abstract.

An APA-style research report begins with a title page The first page of an APA-style manuscript, containing the title, author names and affiliations, and author note. . The title is centered in the upper half of the page, with each important word capitalized. The title should clearly and concisely (in about 12 words or fewer) communicate the primary variables and research questions. This sometimes requires a main title followed by a subtitle that elaborates on the main title, in which case the main title and subtitle are separated by a colon. Here are some titles from recent issues of professional journals published by the American Psychological Association.

- Sex Differences in Coping Styles and Implications for Depressed Mood

- Effects of Aging and Divided Attention on Memory for Items and Their Contexts

- Computer-Assisted Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Child Anxiety: Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial

- Virtual Driving and Risk Taking: Do Racing Games Increase Risk-Taking Cognitions, Affect, and Behavior?

Below the title are the authors’ names and, on the next line, their institutional affiliation—the university or other institution where the authors worked when they conducted the research. As we have already seen, the authors are listed in an order that reflects their contribution to the research. When multiple authors have made equal contributions to the research, they often list their names alphabetically or in a randomly determined order.

It’s Soooo Cute!

How Informal Should an Article Title Be?

In some areas of psychology, the titles of many empirical research reports are informal in a way that is perhaps best described as “cute.” They usually take the form of a play on words or a well-known expression that relates to the topic under study. Here are some examples from recent issues of the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology .

- “Let’s Get Serious: Communicating Commitment in Romantic Relationships”

- “Through the Looking Glass Clearly: Accuracy and Assumed Similarity in Well-Adjusted Individuals’ First Impressions”

- “Don’t Hide Your Happiness! Positive Emotion Dissociation, Social Connectedness, and Psychological Functioning”

- “Forbidden Fruit: Inattention to Attractive Alternatives Provokes Implicit Relationship Reactance”

Individual researchers differ quite a bit in their preference for such titles. Some use them regularly, while others never use them. What might be some of the pros and cons of using cute article titles?

For articles that are being submitted for publication, the title page also includes an author note that lists the authors’ full institutional affiliations, any acknowledgments the authors wish to make to agencies that funded the research or to colleagues who commented on it, and contact information for the authors. For student papers that are not being submitted for publication—including theses—author notes are generally not necessary.

The abstract A short summary (approximately 200 words) of a research article. In an APA-style manuscript, the abstract appears on the second page. is a summary of the study. It is the second page of the manuscript and is headed with the word Abstract . The first line is not indented. The abstract presents the research question, a summary of the method, the basic results, and the most important conclusions. Because the abstract is usually limited to about 200 words, it can be a challenge to write a good one.

Introduction

The introduction The first major section of an APA-style empirical research report. It typically includes an opening, a literature review, and a closing. begins on the third page of the manuscript. The heading at the top of this page is the full title of the manuscript, with each important word capitalized as on the title page. The introduction includes three distinct subsections, although these are typically not identified by separate headings. The opening introduces the research question and explains why it is interesting, the literature review discusses relevant previous research, and the closing restates the research question and comments on the method used to answer it.

The Opening

The opening The first paragraph or two of the introduction of an APA-style empirical report. It introduces the research question and explains why it is interesting. , which is usually a paragraph or two in length, introduces the research question and explains why it is interesting. To capture the reader’s attention, researcher Daryl Bem recommends starting with general observations about the topic under study, expressed in ordinary language (not technical jargon)—observations that are about people and their behavior (not about researchers or their research; Bem, 2003). Bem, D. J. (2003). Writing the empirical journal article. In J. M. Darley, M. P. Zanna, & H. R. Roediger III (Eds.), The compleat academic: A practical guide for the beginning social scientist (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Concrete examples are often very useful here. According to Bem, this would be a poor way to begin a research report:

Festinger’s theory of cognitive dissonance received a great deal of attention during the latter part of the 20th century (p. 191)

The following would be much better:

The individual who holds two beliefs that are inconsistent with one another may feel uncomfortable. For example, the person who knows that he or she enjoys smoking but believes it to be unhealthy may experience discomfort arising from the inconsistency or disharmony between these two thoughts or cognitions. This feeling of discomfort was called cognitive dissonance by social psychologist Leon Festinger (1957), who suggested that individuals will be motivated to remove this dissonance in whatever way they can (p. 191).

After capturing the reader’s attention, the opening should go on to introduce the research question and explain why it is interesting. Will the answer fill a gap in the literature? Will it provide a test of an important theory? Does it have practical implications? Giving readers a clear sense of what the research is about and why they should care about it will motivate them to continue reading the literature review—and will help them make sense of it.

Breaking the Rules

Researcher Larry Jacoby reported several studies showing that a word that people see or hear repeatedly can seem more familiar even when they do not recall the repetitions—and that this tendency is especially pronounced among older adults. He opened his article with the following humorous anecdote (Jacoby, 1999).

A friend whose mother is suffering symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) tells the story of taking her mother to visit a nursing home, preliminary to her mother’s moving there. During an orientation meeting at the nursing home, the rules and regulations were explained, one of which regarded the dining room. The dining room was described as similar to a fine restaurant except that tipping was not required. The absence of tipping was a central theme in the orientation lecture, mentioned frequently to emphasize the quality of care along with the advantages of having paid in advance. At the end of the meeting, the friend’s mother was asked whether she had any questions. She replied that she only had one question: “Should I tip?” (p. 3).

Although both humor and personal anecdotes are generally discouraged in APA-style writing, this example is a highly effective way to start because it both engages the reader and provides an excellent real-world example of the topic under study.

The Literature Review

Immediately after the opening comes the literature review A written summary of previous research on a topic. It constitutes the bulk of the introduction of an APA-style empirical research report. , which describes relevant previous research on the topic and can be anywhere from several paragraphs to several pages in length. However, the literature review is not simply a list of past studies. Instead, it constitutes a kind of argument for why the research question is worth addressing. By the end of the literature review, readers should be convinced that the research question makes sense and that the present study is a logical next step in the ongoing research process.

Like any effective argument, the literature review must have some kind of structure. For example, it might begin by describing a phenomenon in a general way along with several studies that demonstrate it, then describing two or more competing theories of the phenomenon, and finally presenting a hypothesis to test one or more of the theories. Or it might describe one phenomenon, then describe another phenomenon that seems inconsistent with the first one, then propose a theory that resolves the inconsistency, and finally present a hypothesis to test that theory. In applied research, it might describe a phenomenon or theory, then describe how that phenomenon or theory applies to some important real-world situation, and finally suggest a way to test whether it does, in fact, apply to that situation.

Looking at the literature review in this way emphasizes a few things. First, it is extremely important to start with an outline of the main points that you want to make, organized in the order that you want to make them. The basic structure of your argument, then, should be apparent from the outline itself. Second, it is important to emphasize the structure of your argument in your writing. One way to do this is to begin the literature review by summarizing your argument even before you begin to make it. “In this article, I will describe two apparently contradictory phenomena, present a new theory that has the potential to resolve the apparent contradiction, and finally present a novel hypothesis to test the theory.” Another way is to open each paragraph with a sentence that summarizes the main point of the paragraph and links it to the preceding points. These opening sentences provide the “transitions” that many beginning researchers have difficulty with. Instead of beginning a paragraph by launching into a description of a previous study, such as “Williams (2004) found that…,” it is better to start by indicating something about why you are describing this particular study. Here are some simple examples:

Another example of this phenomenon comes from the work of Williams (2004).

Williams (2004) offers one explanation of this phenomenon.

An alternative perspective has been provided by Williams (2004).

We used a method based on the one used by Williams (2004).

Finally, remember that your goal is to construct an argument for why your research question is interesting and worth addressing—not necessarily why your favorite answer to it is correct. In other words, your literature review must be balanced. If you want to emphasize the generality of a phenomenon, then of course you should discuss various studies that have demonstrated it. However, if there are other studies that have failed to demonstrate it, you should discuss them too. Or if you are proposing a new theory, then of course you should discuss findings that are consistent with that theory. However, if there are other findings that are inconsistent with it, again, you should discuss them too. It is acceptable to argue that the balance of the research supports the existence of a phenomenon or is consistent with a theory (and that is usually the best that researchers in psychology can hope for), but it is not acceptable to ignore contradictory evidence. Besides, a large part of what makes a research question interesting is uncertainty about its answer.

The Closing

The closing The last paragraph or two of the introduction of an APA-style empirical research report. It restates the research question and comments on the method. of the introduction—typically the final paragraph or two—usually includes two important elements. The first is a clear statement of the main research question or hypothesis. This statement tends to be more formal and precise than in the opening and is often expressed in terms of operational definitions of the key variables. The second is a brief overview of the method and some comment on its appropriateness. Here, for example, is how Darley and Latané (1968) Darley, J. M., & Latané, B. (1968). Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4 , 377–383. concluded the introduction to their classic article on the bystander effect:

These considerations lead to the hypothesis that the more bystanders to an emergency, the less likely, or the more slowly, any one bystander will intervene to provide aid. To test this proposition it would be necessary to create a situation in which a realistic “emergency” could plausibly occur. Each subject should also be blocked from communicating with others to prevent his getting information about their behavior during the emergency. Finally, the experimental situation should allow for the assessment of the speed and frequency of the subjects’ reaction to the emergency. The experiment reported below attempted to fulfill these conditions (p. 378).

Thus the introduction leads smoothly into the next major section of the article—the method section.

The method section The section of an APA-style empirical research report in which the method is described in detail. At minimum, it includes a participants subsection and a design and procedure subsections. is where you describe how you conducted your study. An important principle for writing a method section is that it should be clear and detailed enough that other researchers could replicate the study by following your “recipe.” This means that it must describe all the important elements of the study—basic demographic characteristics of the participants, how they were recruited, whether they were randomly assigned, how the variables were manipulated or measured, how counterbalancing was accomplished, and so on. At the same time, it should avoid irrelevant details such as the fact that the study was conducted in Classroom 37B of the Industrial Technology Building or that the questionnaire was double-sided and completed using pencils.

The method section begins immediately after the introduction ends with the heading “Method” (not “Methods”) centered on the page. Immediately after this is the subheading “Participants,” left justified and in italics. The participants subsection indicates how many participants there were, the number of women and men, some indication of their age, other demographics that may be relevant to the study, and how they were recruited, including any incentives given for participation.

Figure 11.1 Three Ways of Organizing an APA-Style Method

After the participants section, the structure can vary a bit. Figure 11.1 "Three Ways of Organizing an APA-Style Method" shows three common approaches. In the first, the participants section is followed by a design and procedure subsection, which describes the rest of the method. This works well for methods that are relatively simple and can be described adequately in a few paragraphs. In the second approach, the participants section is followed by separate design and procedure subsections. This works well when both the design and the procedure are relatively complicated and each requires multiple paragraphs.

What is the difference between design and procedure? The design of a study is its overall structure. What were the independent and dependent variables? Was the independent variable manipulated, and if so, was it manipulated between or within subjects? How were the variables operationally defined? The procedure is how the study was carried out. It often works well to describe the procedure in terms of what the participants did rather than what the researchers did. For example, the participants gave their informed consent, read a set of instructions, completed a block of four practice trials, completed a block of 20 test trials, completed two questionnaires, and were debriefed and excused.

In the third basic way to organize a method section, the participants subsection is followed by a materials subsection before the design and procedure subsections. This works well when there are complicated materials to describe. This might mean multiple questionnaires, written vignettes that participants read and respond to, perceptual stimuli, and so on. The heading of this subsection can be modified to reflect its content. Instead of “Materials,” it can be “Questionnaires,” “Stimuli,” and so on.

The results section The section of an APA-style empirical research report in which the results are described in detail. is where you present the main results of the study, including the results of the statistical analyses. Although it does not include the raw data—individual participants’ responses or scores—researchers should save their raw data and make them available to other researchers who request them. Some journals now make the raw data available online.

Although there are no standard subsections, it is still important for the results section to be logically organized. Typically it begins with certain preliminary issues. One is whether any participants or responses were excluded from the analyses and why. The rationale for excluding data should be described clearly so that other researchers can decide whether it is appropriate. A second preliminary issue is how multiple responses were combined to produce the primary variables in the analyses. For example, if participants rated the attractiveness of 20 stimulus people, you might have to explain that you began by computing the mean attractiveness rating for each participant. Or if they recalled as many items as they could from study list of 20 words, did you count the number correctly recalled, compute the percentage correctly recalled, or perhaps compute the number correct minus the number incorrect? A third preliminary issue is the reliability of the measures. This is where you would present test-retest correlations, Cronbach’s α, or other statistics to show that the measures are consistent across time and across items. A final preliminary issue is whether the manipulation was successful. This is where you would report the results of any manipulation checks.

The results section should then tackle the primary research questions, one at a time. Again, there should be a clear organization. One approach would be to answer the most general questions and then proceed to answer more specific ones. Another would be to answer the main question first and then to answer secondary ones. Regardless, Bem (2003) Bem, D. J. (2003). Writing the empirical journal article. In J. M. Darley, M. P. Zanna, & H. R. Roediger III (Eds.), The compleat academic: A practical guide for the beginning social scientist (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. suggests the following basic structure for discussing each new result:

- Remind the reader of the research question.

- Give the answer to the research question in words.

- Present the relevant statistics.

- Qualify the answer if necessary.

- Summarize the result.

Notice that only Step 3 necessarily involves numbers. The rest of the steps involve presenting the research question and the answer to it in words. In fact, the basic results should be clear even to a reader who skips over the numbers.