- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Introduction

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Introduction

- Getting Started

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

What are Literature Reviews?

So, what is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries." Taylor, D. The literature review: A few tips on conducting it . University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre.

Goals of Literature Reviews

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review? A literature could be written to accomplish different aims:

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Review of General Psychology , 1 (3), 311-320.

What kinds of sources require a Literature Review?

- A research paper assigned in a course

- A thesis or dissertation

- A grant proposal

- An article intended for publication in a journal

All these instances require you to collect what has been written about your research topic so that you can demonstrate how your own research sheds new light on the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Narrative review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Example : Predictors and Outcomes of U.S. Quality Maternity Leave: A Review and Conceptual Framework: 10.1177/08948453211037398

Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L. K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . Plural Publishing.

- Example : The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review: 10.1057/s41599-022-01270-w

Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M. C., & Ilardi, S. S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Blackwell Publishing.

- Example : Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A Meta-Analysis: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311-318.

- Example : Women’s perspectives on career successes and barriers: A qualitative meta-synthesis: 10.1177/05390184221113735

Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- UConn Health subject guide on systematic reviews Explanation of the different review types used in health sciences literature as well as tools to help you find the right review type

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: How to Pick a Topic >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

What is the Purpose of a Literature Review?

4-minute read

- 23rd October 2023

If you’re writing a research paper or dissertation , then you’ll most likely need to include a comprehensive literature review . In this post, we’ll review the purpose of literature reviews, why they are so significant, and the specific elements to include in one. Literature reviews can:

1. Provide a foundation for current research.

2. Define key concepts and theories.

3. Demonstrate critical evaluation.

4. Show how research and methodologies have evolved.

5. Identify gaps in existing research.

6. Support your argument.

Keep reading to enter the exciting world of literature reviews!

What is a Literature Review?

A literature review is a critical summary and evaluation of the existing research (e.g., academic journal articles and books) on a specific topic. It is typically included as a separate section or chapter of a research paper or dissertation, serving as a contextual framework for a study. Literature reviews can vary in length depending on the subject and nature of the study, with most being about equal length to other sections or chapters included in the paper. Essentially, the literature review highlights previous studies in the context of your research and summarizes your insights in a structured, organized format. Next, let’s look at the overall purpose of a literature review.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Literature reviews are considered an integral part of research across most academic subjects and fields. The primary purpose of a literature review in your study is to:

Provide a Foundation for Current Research

Since the literature review provides a comprehensive evaluation of the existing research, it serves as a solid foundation for your current study. It’s a way to contextualize your work and show how your research fits into the broader landscape of your specific area of study.

Define Key Concepts and Theories

The literature review highlights the central theories and concepts that have arisen from previous research on your chosen topic. It gives your readers a more thorough understanding of the background of your study and why your research is particularly significant .

Demonstrate Critical Evaluation

A comprehensive literature review shows your ability to critically analyze and evaluate a broad range of source material. And since you’re considering and acknowledging the contribution of key scholars alongside your own, it establishes your own credibility and knowledge.

Show How Research and Methodologies Have Evolved

Another purpose of literature reviews is to provide a historical perspective and demonstrate how research and methodologies have changed over time, especially as data collection methods and technology have advanced. And studying past methodologies allows you, as the researcher, to understand what did and did not work and apply that knowledge to your own research.

Identify Gaps in Existing Research

Besides discussing current research and methodologies, the literature review should also address areas that are lacking in the existing literature. This helps further demonstrate the relevance of your own research by explaining why your study is necessary to fill the gaps.

Support Your Argument

A good literature review should provide evidence that supports your research questions and hypothesis. For example, your study may show that your research supports existing theories or builds on them in some way. Referencing previous related studies shows your work is grounded in established research and will ultimately be a contribution to the field.

Literature Review Editing Services

Ensure your literature review is polished and ready for submission by having it professionally proofread and edited by our expert team. Our literature review editing services will help your research stand out and make an impact. Not convinced yet? Send in your free sample today and see for yourself!

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

How to Ace Slack Messaging for Contractors and Freelancers

Effective professional communication is an important skill for contractors and freelancers navigating remote work environments....

3-minute read

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

- Library Homepage

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide: Literature Reviews?

- Literature Reviews?

- Strategies to Finding Sources

- Keeping up with Research!

- Evaluating Sources & Literature Reviews

- Organizing for Writing

- Writing Literature Review

- Other Academic Writings

What is a Literature Review?

So, what is a literature review .

"A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available or a set of summaries." - Quote from Taylor, D. (n.d)."The Literature Review: A Few Tips on Conducting it".

- Citation: "The Literature Review: A Few Tips on Conducting it"

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Each field has a particular way to do reviews for academic research literature. In the social sciences and humanities the most common are:

- Narrative Reviews: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific research topic and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weaknesses, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section that summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Book review essays/ Historiographical review essays : A type of literature review typical in History and related fields, e.g., Latin American studies. For example, the Latin American Research Review explains that the purpose of this type of review is to “(1) to familiarize readers with the subject, approach, arguments, and conclusions found in a group of books whose common focus is a historical period; a country or region within Latin America; or a practice, development, or issue of interest to specialists and others; (2) to locate these books within current scholarship, critical methodologies, and approaches; and (3) to probe the relation of these new books to previous work on the subject, especially canonical texts. Unlike individual book reviews, the cluster reviews found in LARR seek to address the state of the field or discipline and not solely the works at issue.” - LARR

What are the Goals of Creating a Literature Review?

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

- Baumeister, R.F. & Leary, M.R. (1997). "Writing narrative literature reviews," Review of General Psychology , 1(3), 311-320.

When do you need to write a Literature Review?

- When writing a prospectus or a thesis/dissertation

- When writing a research paper

- When writing a grant proposal

In all these cases you need to dedicate a chapter in these works to showcase what has been written about your research topic and to point out how your own research will shed new light into a body of scholarship.

Where I can find examples of Literature Reviews?

Note: In the humanities, even if they don't use the term "literature review", they may have a dedicated chapter that reviewed the "critical bibliography" or they incorporated that review in the introduction or first chapter of the dissertation, book, or article.

- UCSB electronic theses and dissertations In partnership with the Graduate Division, the UC Santa Barbara Library is making available theses and dissertations produced by UCSB students. Currently included in ADRL are theses and dissertations that were originally filed electronically, starting in 2011. In future phases of ADRL, all theses and dissertations created by UCSB students may be digitized and made available.

Where to Find Standalone Literature Reviews

Literature reviews are also written as standalone articles as a way to survey a particular research topic in-depth. This type of literature review looks at a topic from a historical perspective to see how the understanding of the topic has changed over time.

- Find e-Journals for Standalone Literature Reviews The best way to get familiar with and to learn how to write literature reviews is by reading them. You can use our Journal Search option to find journals that specialize in publishing literature reviews from major disciplines like anthropology, sociology, etc. Usually these titles are called, "Annual Review of [discipline name] OR [Discipline name] Review. This option works best if you know the title of the publication you are looking for. Below are some examples of these journals! more... less... Journal Search can be found by hovering over the link for Research on the library website.

Social Sciences

- Annual Review of Anthropology

- Annual Review of Political Science

- Annual Review of Sociology

- Ethnic Studies Review

Hard science and health sciences:

- Annual Review of Biomedical Data Science

- Annual Review of Materials Science

- Systematic Review From journal site: "The journal Systematic Reviews encompasses all aspects of the design, conduct, and reporting of systematic reviews" in the health sciences.

- << Previous: Overview

- Next: Strategies to Finding Sources >>

- Last Updated: Mar 5, 2024 11:44 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucsb.edu/litreview

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

Published on 22 February 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 7 June 2022.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research.

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarise sources – it analyses, synthesises, and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Why write a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1: search for relevant literature, step 2: evaluate and select sources, step 3: identify themes, debates and gaps, step 4: outline your literature review’s structure, step 5: write your literature review, frequently asked questions about literature reviews, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a dissertation or thesis, you will have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position yourself in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your dissertation addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

You might also have to write a literature review as a stand-alone assignment. In this case, the purpose is to evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of scholarly debates around a topic.

The content will look slightly different in each case, but the process of conducting a literature review follows the same steps. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research objectives and questions .

If you are writing a literature review as a stand-alone assignment, you will have to choose a focus and develop a central question to direct your search. Unlike a dissertation research question, this question has to be answerable without collecting original data. You should be able to answer it based only on a review of existing publications.

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research topic. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list if you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can use boolean operators to help narrow down your search:

Read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

To identify the most important publications on your topic, take note of recurring citations. If the same authors, books or articles keep appearing in your reading, make sure to seek them out.

You probably won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on the topic – you’ll have to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your questions.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models and methods? Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- How does the publication contribute to your understanding of the topic? What are its key insights and arguments?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible, and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can find out how many times an article has been cited on Google Scholar – a high citation count means the article has been influential in the field, and should certainly be included in your literature review.

The scope of your review will depend on your topic and discipline: in the sciences you usually only review recent literature, but in the humanities you might take a long historical perspective (for example, to trace how a concept has changed in meaning over time).

Remember that you can use our template to summarise and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using!

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It’s important to keep track of your sources with references to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography, where you compile full reference information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

You can use our free APA Reference Generator for quick, correct, consistent citations.

To begin organising your literature review’s argument and structure, you need to understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly-visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat – this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organising the body of a literature review. You should have a rough idea of your strategy before you start writing.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarising sources in order.

Try to analyse patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organise your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text, your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

If you are writing the literature review as part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate your central problem or research question and give a brief summary of the scholarly context. You can emphasise the timeliness of the topic (“many recent studies have focused on the problem of x”) or highlight a gap in the literature (“while there has been much research on x, few researchers have taken y into consideration”).

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, make sure to follow these tips:

- Summarise and synthesise: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole.

- Analyse and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole.

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources.

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transitions and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts.

In the conclusion, you should summarise the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasise their significance.

If the literature review is part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate how your research addresses gaps and contributes new knowledge, or discuss how you have drawn on existing theories and methods to build a framework for your research. This can lead directly into your methodology section.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a dissertation , thesis, research paper , or proposal .

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarise yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, June 07). What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 21 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a dissertation proposal | a step-by-step guide, what is a theoretical framework | a step-by-step guide, what is a research methodology | steps & tips.

- Become Involved |

- Give to the Library |

- Staff Directory |

- UNF Library

- Thomas G. Carpenter Library

Conducting a Literature Review

What is a literature review, original research vs. survey of the literature.

- Benefits of Conducting a Literature Review

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Summary of the Process

- Additional Resources

Chat With Us Text Us (904) 507-4122 Email Us Schedule a Research Consultation

Visit us on social media!

Student Engagement Librarian

The literature review is an integral part of any research project and is undertaken as a means of surveying what research has been conducted previously on a particular topic.

There are many reasons for conducting a literature review, but one of the primary reasons is to establish a base line of what is already known on a topic before exploring the topic any further. The review typically involves a search of any previously published or presented materials that might have relevance to a prospective new study.

If the point of a research project is solely to review what has already been written on a topic, the resulting article is termed a "survey of the literature" or a "literature survey" or even a "literature review." In this case, the article is complete in itself and does not delve into anything new regarding the topic. A literature survey might end with a discussion of what work is still needed to further develop knowledge of a particular topic, but it does not, itself, flesh out any of those ideas. Articles of this type can be highly beneficial to someone seeking to launch an original study; literature surveys have already laid some of the groundwork for a prospective researcher's own literature review.

When the survey serves as the initial step that precedes a further investigation of an idea or ideas about a topic, then that review of the literature sets the stage for the presentation of original research. Original research usually involves the selection of a methodology for examining a topic and may include the gathering of data that can be further analyzed to arrive at assumptions about the topic. Data may be derived from the examination of human subjects, from conducting surveys or assessments, from the study of particular species of plants or animals, from the systematic scientific measurement of any physical phenomena, from nearly anything that can be documented and analyzed. Again, the whole point of launching an original study is to learn something new about a topic. Research typically begins with what is known (the literature review) and progresses into analyzing, through the observation and analysis of data, what is yet to be known through further study.

Both the literature survey and the original study are considered academic articles, as opposed to popular articles. Both involve research in order to come to a better understanding of a topic.

- Literature Review Tutorial by American University Library

- The Literature Review: A Few Tips On Conducting It by University of Toronto

- Write a Literature Review by UC Santa Cruz University Library

- Next: Benefits of Conducting a Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Aug 29, 2022 8:54 AM

- URL: https://libguides.unf.edu/litreview

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

- What is a literature review?

- Steps in the Literature Review Process

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

What is a Literature Review?

A literature or narrative review is a comprehensive review and analysis of the published literature on a specific topic or research question. The literature that is reviewed contains: books, articles, academic articles, conference proceedings, association papers, and dissertations. It contains the most pertinent studies and points to important past and current research and practices. It provides background and context, and shows how your research will contribute to the field.

A literature review should:

- Provide a comprehensive and updated review of the literature;

- Explain why this review has taken place;

- Articulate a position or hypothesis;

- Acknowledge and account for conflicting and corroborating points of view

From S age Research Methods

Purpose of a Literature Review

A literature review can be written as an introduction to a study to:

- Demonstrate how a study fills a gap in research

- Compare a study with other research that's been done

Or it can be a separate work (a research article on its own) which:

- Organizes or describes a topic

- Describes variables within a particular issue/problem

Limitations of a Literature Review

Some of the limitations of a literature review are:

- It's a snapshot in time. Unlike other reviews, this one has beginning, a middle and an end. There may be future developments that could make your work less relevant.

- It may be too focused. Some niche studies may miss the bigger picture.

- It can be difficult to be comprehensive. There is no way to make sure all the literature on a topic was considered.

- It is easy to be biased if you stick to top tier journals. There may be other places where people are publishing exemplary research. Look to open access publications and conferences to reflect a more inclusive collection. Also, make sure to include opposing views (and not just supporting evidence).

Source: Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information & Libraries Journal, vol. 26, no. 2, June 2009, pp. 91–108. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

Meryl Brodsky : Communication and Information Studies

Hannah Chapman Tripp : Biology, Neuroscience

Carolyn Cunningham : Human Development & Family Sciences, Psychology, Sociology

Larayne Dallas : Engineering

Janelle Hedstrom : Special Education, Curriculum & Instruction, Ed Leadership & Policy

Susan Macicak : Linguistics

Imelda Vetter : Dell Medical School

For help in other subject areas, please see the guide to library specialists by subject .

Periodically, UT Libraries runs a workshop covering the basics and library support for literature reviews. While we try to offer these once per academic year, we find providing the recording to be helpful to community members who have missed the session. Following is the most recent recording of the workshop, Conducting a Literature Review. To view the recording, a UT login is required.

- October 26, 2022 recording

- Last Updated: Oct 26, 2022 2:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

Get Started

Take the first step and invest in your future.

Online Programs

Offering flexibility & convenience in 51 online degrees & programs.

Prairie Stars

Featuring 15 intercollegiate NCAA Div II athletic teams.

Find your Fit

UIS has over 85 student and 10 greek life organizations, and many volunteer opportunities.

Arts & Culture

Celebrating the arts to create rich cultural experiences on campus.

Give Like a Star

Your generosity helps fuel fundraising for scholarships, programs and new initiatives.

Bragging Rights

UIS was listed No. 1 in Illinois and No. 3 in the Midwest in 2023 rankings.

- Quick links Applicants & Students Important Apps & Links Alumni Faculty and Staff Community Admissions How to Apply Cost & Aid Tuition Calculator Registrar Orientation Visit Campus Academics Register for Class Programs of Study Online Degrees & Programs Graduate Education International Student Services Study Away Student Support Bookstore UIS Life Dining Diversity & Inclusion Get Involved Health & Wellness COVID-19 United in Safety Residence Life Student Life Programs UIS Connection Important Apps UIS Mobile App Advise U Canvas myUIS i-card Balance Pay My Bill - UIS Bursar Self-Service Email Resources Bookstore Box Information Technology Services Library Orbit Policies Webtools Get Connected Area Information Calendar Campus Recreation Departments & Programs (A-Z) Parking UIS Newsroom The Observer Connect & Get Involved Update your Info Alumni Events Alumni Networks & Groups Volunteer Opportunities Alumni Board News & Publications Featured Alumni Alumni News UIS Alumni Magazine Resources Order your Transcripts Give Back Alumni Programs Career Development Services & Support Accessibility Services Campus Services Campus Police Facilities & Services Registrar Faculty & Staff Resources Website Project Request Web Services Training & Tools Academic Impressions Career Connect CSA Reporting Cybersecurity Training Faculty Research FERPA Training Website Login Campus Resources Newsroom Campus Calendar Campus Maps i-Card Human Resources Public Relations Webtools Arts & Events UIS Performing Arts Center Visual Arts Gallery Event Calendar Sangamon Experience Center for Lincoln Studies ECCE Speaker Series Community Engagement Center for State Policy and Leadership Illinois Innocence Project Innovate Springfield Central IL Nonprofit Resource Center NPR Illinois Community Resources Child Protection Training Academy Office of Electronic Media University Archives/IRAD Institute for Illinois Public Finance

Request Info

Literature Review

- Request Info Request info for.... Undergraduate/Graduate Online Study Away Continuing & Professional Education International Student Services General Inquiries

The purpose of a literature review is to collect relevant, timely research on your chosen topic, and synthesize it into a cohesive summary of existing knowledge in the field. This then prepares you for making your own argument on that topic, or for conducting your own original research.

Depending on your field of study, literature reviews can take different forms. Some disciplines require that you synthesize your sources topically, organizing your paragraphs according to how your different sources discuss similar topics. Other disciplines require that you discuss each source in individual paragraphs, covering various aspects in that single article, chapter, or book.

Within your review of a given source, you can cover many different aspects, including (if a research study) the purpose, scope, methods, results, any discussion points, limitations, and implications for future research. Make sure you know which model your professor expects you to follow when writing your own literature reviews.

Tip : Literature reviews may or may not be a graded component of your class or major assignment, but even if it is not, it is a good idea to draft one so that you know the current conversations taking place on your chosen topic. It can better prepare you to write your own, unique argument.

Benefits of Literature Reviews

- Literature reviews allow you to gain familiarity with the current knowledge in your chosen field, as well as the boundaries and limitations of that field.

- Literature reviews also help you to gain an understanding of the theory(ies) driving the field, allowing you to place your research question into context.

- Literature reviews provide an opportunity for you to see and even evaluate successful and unsuccessful assessment and research methods in your field.

- Literature reviews prevent you from duplicating the same information as others writing in your field, allowing you to find your own, unique approach to your topic.

- Literature reviews give you familiarity with the knowledge in your field, giving you the chance to analyze the significance of your additional research.

Choosing Your Sources

When selecting your sources to compile your literature review, make sure you follow these guidelines to ensure you are working with the strongest, most appropriate sources possible.

Topically Relevant

Find sources within the scope of your topic

Appropriately Aged

Find sources that are not too old for your assignment

Find sources whose authors have authority on your topic

Appropriately “Published”

Find sources that meet your instructor’s guidelines (academic, professional, print, etc.)

Tip: Treat your professors and librarians as experts you can turn to for advice on how to locate sources. They are a valuable asset to you, so take advantage of them!

Organizing Your Literature Review

Synthesizing topically.

Some assignments require discussing your sources together, in paragraphs organized according to shared topics between them.

For example, in a literature review covering current conversations on Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home , authors may discuss various topics including:

- her graphic style

- her allusions to various literary texts

- her story’s implications regarding LGBT experiences in 20 th century America.

In this case, you would cluster your sources on these three topics. One paragraph would cover how the sources you collected dealt with Bechdel’s graphic style. Another, her allusions. A third, her implications.

Each of these paragraphs would discuss how the sources you found treated these topics in connection to one another. Basically, you compare and contrast how your sources discuss similar issues and points.

To determine these shared topics, examine aspects including:

- Definition of terms

- Common ground

- Issues that divide

- Rhetorical context

Summarizing Individually

Depending on the assignment, your professor may prefer that you discuss each source in your literature review individually (in their own, separate paragraphs or sections). Your professor may give you specific guidelines as far as what to cover in these paragraphs/sections.

If, for instance, your sources are all primary research studies, here are some aspects to consider covering:

- Participants

- Limitations

- Implications

- Significance

Each section of your literature review, in this case, will identify all of these elements for each individual article.

You may or may not need to separate your information into multiple paragraphs for each source. If you do, using proper headings in the appropriate citation style (APA, MLA, etc.) will help keep you organized.

If you are writing a literature review as part of a larger assignment, you generally do not need an introduction and/or conclusion, because it is embedded within the context of your larger paper.

If, however, your literature review is a standalone assignment, it is a good idea to include some sort of introduction and conclusion to provide your reader with context regarding your topic, purpose, and any relevant implications or further questions. Make sure you know what your professor is expecting for your literature review’s content.

Typically, a literature review concludes with a full bibliography of your included sources. Make sure you use the style guide required by your professor for this assignment.

Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

- Collections

- Research Help

YSN Doctoral Programs: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Biomedical Databases

- Global (Public Health) Databases

- Soc. Sci., History, and Law Databases

- Grey Literature

- Trials Registers

- Data and Statistics

- Public Policy

- Google Tips

- Recommended Books

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis -- not just a summary-- of scholarly writings and other relevant evidence related directly to your research question. That is, it represents a synthesis of the evidence that provides background information on your topic and shows a association between the evidence and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

Why is it important?

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Identifies critical gaps and points of disagreement.

- Discusses further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies.

APA7 Style resources

APA Style Blog - for those harder to find answers

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by your central research question. The literature represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow. Is it manageable?

- Begin writing down terms that are related to your question. These will be useful for searches later.

- If you have the opportunity, discuss your topic with your professor and your class mates.

2. Decide on the scope of your review

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment. How many sources does the assignment require?

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

Make a list of the databases you will search.

Where to find databases:

- use the tabs on this guide

- Find other databases in the Nursing Information Resources web page

- More on the Medical Library web page

- ... and more on the Yale University Library web page

4. Conduct your searches to find the evidence. Keep track of your searches.

- Use the key words in your question, as well as synonyms for those words, as terms in your search. Use the database tutorials for help.

- Save the searches in the databases. This saves time when you want to redo, or modify, the searches. It is also helpful to use as a guide is the searches are not finding any useful results.

- Review the abstracts of research studies carefully. This will save you time.

- Use the bibliographies and references of research studies you find to locate others.

- Check with your professor, or a subject expert in the field, if you are missing any key works in the field.

- Ask your librarian for help at any time.

- Use a citation manager, such as EndNote as the repository for your citations. See the EndNote tutorials for help.

Review the literature

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question of the study you are reviewing? What were the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze its literature review, the samples and variables used, the results, and the conclusions.

- Does the research seem to be complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicting studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Has this study been cited? If so, how has it been analyzed?

Tips:

- Review the abstracts carefully.

- Keep careful notes so that you may track your thought processes during the research process.

- Create a matrix of the studies for easy analysis, and synthesis, across all of the studies.

- << Previous: Recommended Books

- Last Updated: Jan 4, 2024 10:52 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/YSNDoctoral

A Guide to Literature Reviews

Importance of a good literature review.

- Conducting the Literature Review

- Structure and Writing Style

- Types of Literature Reviews

- Citation Management Software This link opens in a new window

- Acknowledgements

A literature review is not only a summary of key sources, but has an organizational pattern which combines both summary and synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

The purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important].

- << Previous: Definition

- Next: Conducting the Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: May 10, 2024 11:34 AM

- URL: https://libguides.mcmaster.ca/litreview

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Lau F, Kuziemsky C, editors. Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-based Approach [Internet]. Victoria (BC): University of Victoria; 2017 Feb 27.

Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-based Approach [Internet].

Chapter 9 methods for literature reviews.

Guy Paré and Spyros Kitsiou .

9.1. Introduction

Literature reviews play a critical role in scholarship because science remains, first and foremost, a cumulative endeavour ( vom Brocke et al., 2009 ). As in any academic discipline, rigorous knowledge syntheses are becoming indispensable in keeping up with an exponentially growing eHealth literature, assisting practitioners, academics, and graduate students in finding, evaluating, and synthesizing the contents of many empirical and conceptual papers. Among other methods, literature reviews are essential for: (a) identifying what has been written on a subject or topic; (b) determining the extent to which a specific research area reveals any interpretable trends or patterns; (c) aggregating empirical findings related to a narrow research question to support evidence-based practice; (d) generating new frameworks and theories; and (e) identifying topics or questions requiring more investigation ( Paré, Trudel, Jaana, & Kitsiou, 2015 ).

Literature reviews can take two major forms. The most prevalent one is the “literature review” or “background” section within a journal paper or a chapter in a graduate thesis. This section synthesizes the extant literature and usually identifies the gaps in knowledge that the empirical study addresses ( Sylvester, Tate, & Johnstone, 2013 ). It may also provide a theoretical foundation for the proposed study, substantiate the presence of the research problem, justify the research as one that contributes something new to the cumulated knowledge, or validate the methods and approaches for the proposed study ( Hart, 1998 ; Levy & Ellis, 2006 ).

The second form of literature review, which is the focus of this chapter, constitutes an original and valuable work of research in and of itself ( Paré et al., 2015 ). Rather than providing a base for a researcher’s own work, it creates a solid starting point for all members of the community interested in a particular area or topic ( Mulrow, 1987 ). The so-called “review article” is a journal-length paper which has an overarching purpose to synthesize the literature in a field, without collecting or analyzing any primary data ( Green, Johnson, & Adams, 2006 ).

When appropriately conducted, review articles represent powerful information sources for practitioners looking for state-of-the art evidence to guide their decision-making and work practices ( Paré et al., 2015 ). Further, high-quality reviews become frequently cited pieces of work which researchers seek out as a first clear outline of the literature when undertaking empirical studies ( Cooper, 1988 ; Rowe, 2014 ). Scholars who track and gauge the impact of articles have found that review papers are cited and downloaded more often than any other type of published article ( Cronin, Ryan, & Coughlan, 2008 ; Montori, Wilczynski, Morgan, Haynes, & Hedges, 2003 ; Patsopoulos, Analatos, & Ioannidis, 2005 ). The reason for their popularity may be the fact that reading the review enables one to have an overview, if not a detailed knowledge of the area in question, as well as references to the most useful primary sources ( Cronin et al., 2008 ). Although they are not easy to conduct, the commitment to complete a review article provides a tremendous service to one’s academic community ( Paré et al., 2015 ; Petticrew & Roberts, 2006 ). Most, if not all, peer-reviewed journals in the fields of medical informatics publish review articles of some type.

The main objectives of this chapter are fourfold: (a) to provide an overview of the major steps and activities involved in conducting a stand-alone literature review; (b) to describe and contrast the different types of review articles that can contribute to the eHealth knowledge base; (c) to illustrate each review type with one or two examples from the eHealth literature; and (d) to provide a series of recommendations for prospective authors of review articles in this domain.

9.2. Overview of the Literature Review Process and Steps

As explained in Templier and Paré (2015) , there are six generic steps involved in conducting a review article:

- formulating the research question(s) and objective(s),

- searching the extant literature,

- screening for inclusion,

- assessing the quality of primary studies,

- extracting data, and

- analyzing data.

Although these steps are presented here in sequential order, one must keep in mind that the review process can be iterative and that many activities can be initiated during the planning stage and later refined during subsequent phases ( Finfgeld-Connett & Johnson, 2013 ; Kitchenham & Charters, 2007 ).

Formulating the research question(s) and objective(s): As a first step, members of the review team must appropriately justify the need for the review itself ( Petticrew & Roberts, 2006 ), identify the review’s main objective(s) ( Okoli & Schabram, 2010 ), and define the concepts or variables at the heart of their synthesis ( Cooper & Hedges, 2009 ; Webster & Watson, 2002 ). Importantly, they also need to articulate the research question(s) they propose to investigate ( Kitchenham & Charters, 2007 ). In this regard, we concur with Jesson, Matheson, and Lacey (2011) that clearly articulated research questions are key ingredients that guide the entire review methodology; they underscore the type of information that is needed, inform the search for and selection of relevant literature, and guide or orient the subsequent analysis. Searching the extant literature: The next step consists of searching the literature and making decisions about the suitability of material to be considered in the review ( Cooper, 1988 ). There exist three main coverage strategies. First, exhaustive coverage means an effort is made to be as comprehensive as possible in order to ensure that all relevant studies, published and unpublished, are included in the review and, thus, conclusions are based on this all-inclusive knowledge base. The second type of coverage consists of presenting materials that are representative of most other works in a given field or area. Often authors who adopt this strategy will search for relevant articles in a small number of top-tier journals in a field ( Paré et al., 2015 ). In the third strategy, the review team concentrates on prior works that have been central or pivotal to a particular topic. This may include empirical studies or conceptual papers that initiated a line of investigation, changed how problems or questions were framed, introduced new methods or concepts, or engendered important debate ( Cooper, 1988 ). Screening for inclusion: The following step consists of evaluating the applicability of the material identified in the preceding step ( Levy & Ellis, 2006 ; vom Brocke et al., 2009 ). Once a group of potential studies has been identified, members of the review team must screen them to determine their relevance ( Petticrew & Roberts, 2006 ). A set of predetermined rules provides a basis for including or excluding certain studies. This exercise requires a significant investment on the part of researchers, who must ensure enhanced objectivity and avoid biases or mistakes. As discussed later in this chapter, for certain types of reviews there must be at least two independent reviewers involved in the screening process and a procedure to resolve disagreements must also be in place ( Liberati et al., 2009 ; Shea et al., 2009 ). Assessing the quality of primary studies: In addition to screening material for inclusion, members of the review team may need to assess the scientific quality of the selected studies, that is, appraise the rigour of the research design and methods. Such formal assessment, which is usually conducted independently by at least two coders, helps members of the review team refine which studies to include in the final sample, determine whether or not the differences in quality may affect their conclusions, or guide how they analyze the data and interpret the findings ( Petticrew & Roberts, 2006 ). Ascribing quality scores to each primary study or considering through domain-based evaluations which study components have or have not been designed and executed appropriately makes it possible to reflect on the extent to which the selected study addresses possible biases and maximizes validity ( Shea et al., 2009 ). Extracting data: The following step involves gathering or extracting applicable information from each primary study included in the sample and deciding what is relevant to the problem of interest ( Cooper & Hedges, 2009 ). Indeed, the type of data that should be recorded mainly depends on the initial research questions ( Okoli & Schabram, 2010 ). However, important information may also be gathered about how, when, where and by whom the primary study was conducted, the research design and methods, or qualitative/quantitative results ( Cooper & Hedges, 2009 ). Analyzing and synthesizing data : As a final step, members of the review team must collate, summarize, aggregate, organize, and compare the evidence extracted from the included studies. The extracted data must be presented in a meaningful way that suggests a new contribution to the extant literature ( Jesson et al., 2011 ). Webster and Watson (2002) warn researchers that literature reviews should be much more than lists of papers and should provide a coherent lens to make sense of extant knowledge on a given topic. There exist several methods and techniques for synthesizing quantitative (e.g., frequency analysis, meta-analysis) and qualitative (e.g., grounded theory, narrative analysis, meta-ethnography) evidence ( Dixon-Woods, Agarwal, Jones, Young, & Sutton, 2005 ; Thomas & Harden, 2008 ).

9.3. Types of Review Articles and Brief Illustrations

EHealth researchers have at their disposal a number of approaches and methods for making sense out of existing literature, all with the purpose of casting current research findings into historical contexts or explaining contradictions that might exist among a set of primary research studies conducted on a particular topic. Our classification scheme is largely inspired from Paré and colleagues’ (2015) typology. Below we present and illustrate those review types that we feel are central to the growth and development of the eHealth domain.

9.3.1. Narrative Reviews

The narrative review is the “traditional” way of reviewing the extant literature and is skewed towards a qualitative interpretation of prior knowledge ( Sylvester et al., 2013 ). Put simply, a narrative review attempts to summarize or synthesize what has been written on a particular topic but does not seek generalization or cumulative knowledge from what is reviewed ( Davies, 2000 ; Green et al., 2006 ). Instead, the review team often undertakes the task of accumulating and synthesizing the literature to demonstrate the value of a particular point of view ( Baumeister & Leary, 1997 ). As such, reviewers may selectively ignore or limit the attention paid to certain studies in order to make a point. In this rather unsystematic approach, the selection of information from primary articles is subjective, lacks explicit criteria for inclusion and can lead to biased interpretations or inferences ( Green et al., 2006 ). There are several narrative reviews in the particular eHealth domain, as in all fields, which follow such an unstructured approach ( Silva et al., 2015 ; Paul et al., 2015 ).

Despite these criticisms, this type of review can be very useful in gathering together a volume of literature in a specific subject area and synthesizing it. As mentioned above, its primary purpose is to provide the reader with a comprehensive background for understanding current knowledge and highlighting the significance of new research ( Cronin et al., 2008 ). Faculty like to use narrative reviews in the classroom because they are often more up to date than textbooks, provide a single source for students to reference, and expose students to peer-reviewed literature ( Green et al., 2006 ). For researchers, narrative reviews can inspire research ideas by identifying gaps or inconsistencies in a body of knowledge, thus helping researchers to determine research questions or formulate hypotheses. Importantly, narrative reviews can also be used as educational articles to bring practitioners up to date with certain topics of issues ( Green et al., 2006 ).

Recently, there have been several efforts to introduce more rigour in narrative reviews that will elucidate common pitfalls and bring changes into their publication standards. Information systems researchers, among others, have contributed to advancing knowledge on how to structure a “traditional” review. For instance, Levy and Ellis (2006) proposed a generic framework for conducting such reviews. Their model follows the systematic data processing approach comprised of three steps, namely: (a) literature search and screening; (b) data extraction and analysis; and (c) writing the literature review. They provide detailed and very helpful instructions on how to conduct each step of the review process. As another methodological contribution, vom Brocke et al. (2009) offered a series of guidelines for conducting literature reviews, with a particular focus on how to search and extract the relevant body of knowledge. Last, Bandara, Miskon, and Fielt (2011) proposed a structured, predefined and tool-supported method to identify primary studies within a feasible scope, extract relevant content from identified articles, synthesize and analyze the findings, and effectively write and present the results of the literature review. We highly recommend that prospective authors of narrative reviews consult these useful sources before embarking on their work.

Darlow and Wen (2015) provide a good example of a highly structured narrative review in the eHealth field. These authors synthesized published articles that describe the development process of mobile health ( m-health ) interventions for patients’ cancer care self-management. As in most narrative reviews, the scope of the research questions being investigated is broad: (a) how development of these systems are carried out; (b) which methods are used to investigate these systems; and (c) what conclusions can be drawn as a result of the development of these systems. To provide clear answers to these questions, a literature search was conducted on six electronic databases and Google Scholar . The search was performed using several terms and free text words, combining them in an appropriate manner. Four inclusion and three exclusion criteria were utilized during the screening process. Both authors independently reviewed each of the identified articles to determine eligibility and extract study information. A flow diagram shows the number of studies identified, screened, and included or excluded at each stage of study selection. In terms of contributions, this review provides a series of practical recommendations for m-health intervention development.

9.3.2. Descriptive or Mapping Reviews

The primary goal of a descriptive review is to determine the extent to which a body of knowledge in a particular research topic reveals any interpretable pattern or trend with respect to pre-existing propositions, theories, methodologies or findings ( King & He, 2005 ; Paré et al., 2015 ). In contrast with narrative reviews, descriptive reviews follow a systematic and transparent procedure, including searching, screening and classifying studies ( Petersen, Vakkalanka, & Kuzniarz, 2015 ). Indeed, structured search methods are used to form a representative sample of a larger group of published works ( Paré et al., 2015 ). Further, authors of descriptive reviews extract from each study certain characteristics of interest, such as publication year, research methods, data collection techniques, and direction or strength of research outcomes (e.g., positive, negative, or non-significant) in the form of frequency analysis to produce quantitative results ( Sylvester et al., 2013 ). In essence, each study included in a descriptive review is treated as the unit of analysis and the published literature as a whole provides a database from which the authors attempt to identify any interpretable trends or draw overall conclusions about the merits of existing conceptualizations, propositions, methods or findings ( Paré et al., 2015 ). In doing so, a descriptive review may claim that its findings represent the state of the art in a particular domain ( King & He, 2005 ).

In the fields of health sciences and medical informatics, reviews that focus on examining the range, nature and evolution of a topic area are described by Anderson, Allen, Peckham, and Goodwin (2008) as mapping reviews . Like descriptive reviews, the research questions are generic and usually relate to publication patterns and trends. There is no preconceived plan to systematically review all of the literature although this can be done. Instead, researchers often present studies that are representative of most works published in a particular area and they consider a specific time frame to be mapped.

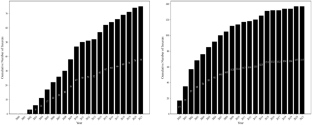

An example of this approach in the eHealth domain is offered by DeShazo, Lavallie, and Wolf (2009). The purpose of this descriptive or mapping review was to characterize publication trends in the medical informatics literature over a 20-year period (1987 to 2006). To achieve this ambitious objective, the authors performed a bibliometric analysis of medical informatics citations indexed in medline using publication trends, journal frequencies, impact factors, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) term frequencies, and characteristics of citations. Findings revealed that there were over 77,000 medical informatics articles published during the covered period in numerous journals and that the average annual growth rate was 12%. The MeSH term analysis also suggested a strong interdisciplinary trend. Finally, average impact scores increased over time with two notable growth periods. Overall, patterns in research outputs that seem to characterize the historic trends and current components of the field of medical informatics suggest it may be a maturing discipline (DeShazo et al., 2009).

9.3.3. Scoping Reviews

Scoping reviews attempt to provide an initial indication of the potential size and nature of the extant literature on an emergent topic (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Daudt, van Mossel, & Scott, 2013 ; Levac, Colquhoun, & O’Brien, 2010). A scoping review may be conducted to examine the extent, range and nature of research activities in a particular area, determine the value of undertaking a full systematic review (discussed next), or identify research gaps in the extant literature ( Paré et al., 2015 ). In line with their main objective, scoping reviews usually conclude with the presentation of a detailed research agenda for future works along with potential implications for both practice and research.

Unlike narrative and descriptive reviews, the whole point of scoping the field is to be as comprehensive as possible, including grey literature (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). Inclusion and exclusion criteria must be established to help researchers eliminate studies that are not aligned with the research questions. It is also recommended that at least two independent coders review abstracts yielded from the search strategy and then the full articles for study selection ( Daudt et al., 2013 ). The synthesized evidence from content or thematic analysis is relatively easy to present in tabular form (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Thomas & Harden, 2008 ).

One of the most highly cited scoping reviews in the eHealth domain was published by Archer, Fevrier-Thomas, Lokker, McKibbon, and Straus (2011) . These authors reviewed the existing literature on personal health record ( phr ) systems including design, functionality, implementation, applications, outcomes, and benefits. Seven databases were searched from 1985 to March 2010. Several search terms relating to phr s were used during this process. Two authors independently screened titles and abstracts to determine inclusion status. A second screen of full-text articles, again by two independent members of the research team, ensured that the studies described phr s. All in all, 130 articles met the criteria and their data were extracted manually into a database. The authors concluded that although there is a large amount of survey, observational, cohort/panel, and anecdotal evidence of phr benefits and satisfaction for patients, more research is needed to evaluate the results of phr implementations. Their in-depth analysis of the literature signalled that there is little solid evidence from randomized controlled trials or other studies through the use of phr s. Hence, they suggested that more research is needed that addresses the current lack of understanding of optimal functionality and usability of these systems, and how they can play a beneficial role in supporting patient self-management ( Archer et al., 2011 ).

9.3.4. Forms of Aggregative Reviews

Healthcare providers, practitioners, and policy-makers are nowadays overwhelmed with large volumes of information, including research-based evidence from numerous clinical trials and evaluation studies, assessing the effectiveness of health information technologies and interventions ( Ammenwerth & de Keizer, 2004 ; Deshazo et al., 2009 ). It is unrealistic to expect that all these disparate actors will have the time, skills, and necessary resources to identify the available evidence in the area of their expertise and consider it when making decisions. Systematic reviews that involve the rigorous application of scientific strategies aimed at limiting subjectivity and bias (i.e., systematic and random errors) can respond to this challenge.

Systematic reviews attempt to aggregate, appraise, and synthesize in a single source all empirical evidence that meet a set of previously specified eligibility criteria in order to answer a clearly formulated and often narrow research question on a particular topic of interest to support evidence-based practice ( Liberati et al., 2009 ). They adhere closely to explicit scientific principles ( Liberati et al., 2009 ) and rigorous methodological guidelines (Higgins & Green, 2008) aimed at reducing random and systematic errors that can lead to deviations from the truth in results or inferences. The use of explicit methods allows systematic reviews to aggregate a large body of research evidence, assess whether effects or relationships are in the same direction and of the same general magnitude, explain possible inconsistencies between study results, and determine the strength of the overall evidence for every outcome of interest based on the quality of included studies and the general consistency among them ( Cook, Mulrow, & Haynes, 1997 ). The main procedures of a systematic review involve:

- Formulating a review question and developing a search strategy based on explicit inclusion criteria for the identification of eligible studies (usually described in the context of a detailed review protocol).

- Searching for eligible studies using multiple databases and information sources, including grey literature sources, without any language restrictions.

- Selecting studies, extracting data, and assessing risk of bias in a duplicate manner using two independent reviewers to avoid random or systematic errors in the process.

- Analyzing data using quantitative or qualitative methods.

- Presenting results in summary of findings tables.

- Interpreting results and drawing conclusions.

Many systematic reviews, but not all, use statistical methods to combine the results of independent studies into a single quantitative estimate or summary effect size. Known as meta-analyses , these reviews use specific data extraction and statistical techniques (e.g., network, frequentist, or Bayesian meta-analyses) to calculate from each study by outcome of interest an effect size along with a confidence interval that reflects the degree of uncertainty behind the point estimate of effect ( Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein, 2009 ; Deeks, Higgins, & Altman, 2008 ). Subsequently, they use fixed or random-effects analysis models to combine the results of the included studies, assess statistical heterogeneity, and calculate a weighted average of the effect estimates from the different studies, taking into account their sample sizes. The summary effect size is a value that reflects the average magnitude of the intervention effect for a particular outcome of interest or, more generally, the strength of a relationship between two variables across all studies included in the systematic review. By statistically combining data from multiple studies, meta-analyses can create more precise and reliable estimates of intervention effects than those derived from individual studies alone, when these are examined independently as discrete sources of information.