152 Brilliant Divorce Essay Topics & Examples

For those who are studying law or social sciences, writing about divorce is a common task. Separation is a complicated issue that can arise from many different situations and lead to adverse outcomes. In this article we gathered an ultimate list of topics about divorce and gathered some tips to when working on the paper.

A BIBLICAL-THEOLOGICAL AND EXEGETICAL SURVEY OF DIVORCE AND REMARRIAGE

Related Papers

Perspective Digest

Richard M Davidson

Joe Sprinkle

René Gehring

Colin Hamer

The long-held understanding in the Old Testament was that the grounds for divorce were asymmetrical: the wife could divorce her husband if he failed to provide for her (Exodus 21:10–11), but the husband could only divorce his wife if she was sexually immoral, in which case he should give her a certificate of divorce which would enable her to remarry (Deuteronomy 24:1–4). But in New Testament times some were suggesting that the Deuteronomy 24 verses had been misunderstood and no such restriction applied. Thus, many had divorced their wives for a wide variety of reasons—it was called an ‘any cause’ divorce. Its legitimacy had become the ‘Brexit’ question of the day: Do you think that the new ‘any cause’ divorces for husbands are valid? Or do you think that the traditional understanding should remain—that is, the husband can only divorce his wife on the grounds of her sexual immorality?

This paper will use three hermeneutical keys to unlock some aspects of the disputed NT pericopae on divorce and remarriage to enable an exegesis that is sensitive to its first century context.

Todd Scacewater

Deuteronomy 24:1–4 records the only law in Deuteronomy on remarriage and has generated much discussion on the enigmatic phrase "nakedness of a thing" (24:1) as well as the purpose for the creation of the law. Yet, the long discussion on the purpose for the creation of the law seems to have been misguided. Scholars have confused the rationale behind the law with the purpose for the creation of the law. In seeking the purpose of the law, interpreters have sought the meaning of "nakedness of a thing" and the rationale behind labeling the woman's actions an " abomination " (24:4). They have ignored the explicitly stated purpose of the law in verse 4. The primary concern of this law on divorce and remarriage is to protect the covenant relationship between Israel and Yahweh, thereby protecting Israel's position in their inherited land of Canaan. While the rationale behind the law is important for biblical ethics, the purpose for the law contributes to the Deuteronomic theme of blessing and curse as it relates to Israel's covenantal obedience.

Donald Polaski

Genesis 2:23 speaks of a miraculous couple in a literal one-flesh union formed by God without a volitional or covenantal basis. Genesis 2:24 outlines a metaphoric restatement of that union whereby a naturally born couple, by means of a covenant, choose to become what they were not in a metaphoric one-flesh family union—such forms the aetiology of mundane marriage in both the Hebrew Bible and the NT. It is this Gen 2:24 marriage that is understood in the Hebrew Bible as the basis of the volitional, conditional, covenantal relationship of Yahweh and Israel, and in the NT of the volitional, conditional, covenantal relationship of Christ and the church—that is, Gen 2:24 is the source domain which is cross-mapped to the target domain (God ‘married’ to his people) in the marital imagery of both the Jewish and Christian Scriptures. It is an imagery that embraced the concept of divorce and remarriage. The NT affirms that the pattern for mundane marriage is to be found in Gen 2:24 (Matt 19:3-9; Mark 10:2-12). But NT scholars and the church have conflated the aetiology of the Gen 2:24 marriage with that of Adam and Eve’s marriage described in Gen 2:23, and thus see that the NT teaches that mundane marriage is to be modelled on the primal couple—a model that imposes restrictions on divorce and remarriage that are not found in the Hebrew Bible. In contrast, this study suggests that the NT writers would not employ an imagery they repudiated in their own mundane marriage teaching, and that an exegesis of that teaching can be found, focusing on divorce and remarriage, which is congruent with its own imagery.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Polonia Sacra 22 (2018) nr 4 (53) 169–186

Marcin Majewski

in: C. Frevel (ed.), Mixed Marriages. Intermarriage and Group Identity in the Second Temple Period (LHBOTS 547), New York 2011, 15-45.

Christian Frevel

Blessing Onoriodẹ Bọlọjẹ , Alphonso Groenewald

Philip D Hill

Commonwealth Theology Essentials

Douglas Hamp

Paul George

Devin Hudson

Africa Journal of Evangelical Theology

Joel Songela

Agana-Nsiire Agana

Franciscanum

Adriani Milli Rodrigues

scott Jarrett

Mark G Brett

Andy Warren-Rothlin

The Village A Preacher

Wally Morris

Michael P Barber

Pp. 21-29 in Marriage in the Catholic Tradition. Edited by Todd Salzman, Thomas Kelly, and John O’Keefe. New York: Crossroads, 2004

Ronald Simkins

UNDERSTANDING THE FOUNDATION AND PURPOSE OF MARRIAGE FROM A BIBLICAL PERSPECTIVE

Biblical Studies Journal

Michael Burgos

Bill T. Arnold

Dr. Samuel Said

Andrews Ohene Gyan Jnr

Journal of Moral Theology

David G . Hunter

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

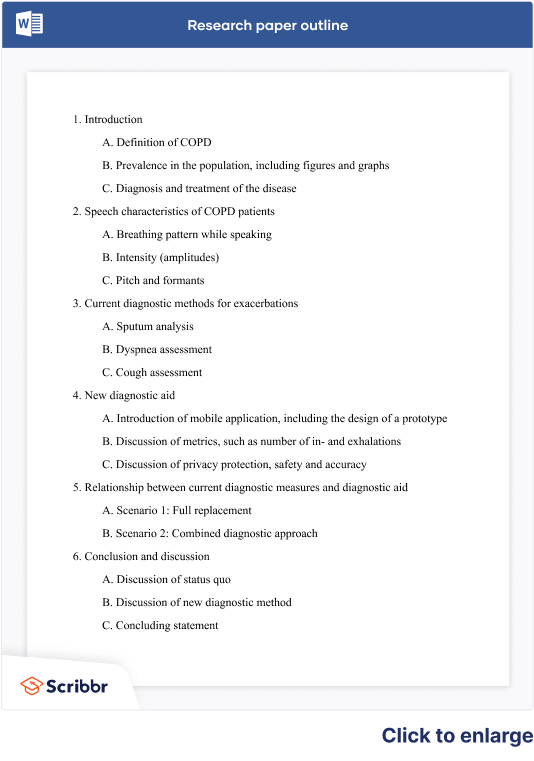

How to Create a Structured Research Paper Outline | Example

Published on August 7, 2022 by Courtney Gahan . Revised on August 15, 2023.

A research paper outline is a useful tool to aid in the writing process , providing a structure to follow with all information to be included in the paper clearly organized.

A quality outline can make writing your research paper more efficient by helping to:

- Organize your thoughts

- Understand the flow of information and how ideas are related

- Ensure nothing is forgotten

A research paper outline can also give your teacher an early idea of the final product.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Research paper outline example, how to write a research paper outline, formatting your research paper outline, language in research paper outlines.

- Definition of measles

- Rise in cases in recent years in places the disease was previously eliminated or had very low rates of infection

- Figures: Number of cases per year on average, number in recent years. Relate to immunization

- Symptoms and timeframes of disease

- Risk of fatality, including statistics

- How measles is spread

- Immunization procedures in different regions

- Different regions, focusing on the arguments from those against immunization

- Immunization figures in affected regions

- High number of cases in non-immunizing regions

- Illnesses that can result from measles virus

- Fatal cases of other illnesses after patient contracted measles

- Summary of arguments of different groups

- Summary of figures and relationship with recent immunization debate

- Which side of the argument appears to be correct?

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

Follow these steps to start your research paper outline:

- Decide on the subject of the paper

- Write down all the ideas you want to include or discuss

- Organize related ideas into sub-groups

- Arrange your ideas into a hierarchy: What should the reader learn first? What is most important? Which idea will help end your paper most effectively?

- Create headings and subheadings that are effective

- Format the outline in either alphanumeric, full-sentence or decimal format

There are three different kinds of research paper outline: alphanumeric, full-sentence and decimal outlines. The differences relate to formatting and style of writing.

- Alphanumeric

- Full-sentence

An alphanumeric outline is most commonly used. It uses Roman numerals, capitalized letters, arabic numerals, lowercase letters to organize the flow of information. Text is written with short notes rather than full sentences.

- Sub-point of sub-point 1

Essentially the same as the alphanumeric outline, but with the text written in full sentences rather than short points.

- Additional sub-point to conclude discussion of point of evidence introduced in point A

A decimal outline is similar in format to the alphanumeric outline, but with a different numbering system: 1, 1.1, 1.2, etc. Text is written as short notes rather than full sentences.

- 1.1.1 Sub-point of first point

- 1.1.2 Sub-point of first point

- 1.2 Second point

To write an effective research paper outline, it is important to pay attention to language. This is especially important if it is one you will show to your teacher or be assessed on.

There are four main considerations: parallelism, coordination, subordination and division.

Parallelism: Be consistent with grammatical form

Parallel structure or parallelism is the repetition of a particular grammatical form within a sentence, or in this case, between points and sub-points. This simply means that if the first point is a verb , the sub-point should also be a verb.

Example of parallelism:

- Include different regions, focusing on the different arguments from those against immunization

Coordination: Be aware of each point’s weight

Your chosen subheadings should hold the same significance as each other, as should all first sub-points, secondary sub-points, and so on.

Example of coordination:

- Include immunization figures in affected regions

- Illnesses that can result from the measles virus

Subordination: Work from general to specific

Subordination refers to the separation of general points from specific. Your main headings should be quite general, and each level of sub-point should become more specific.

Example of subordination:

Division: break information into sub-points.

Your headings should be divided into two or more subsections. There is no limit to how many subsections you can include under each heading, but keep in mind that the information will be structured into a paragraph during the writing stage, so you should not go overboard with the number of sub-points.

Ready to start writing or looking for guidance on a different step in the process? Read our step-by-step guide on how to write a research paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Gahan, C. (2023, August 15). How to Create a Structured Research Paper Outline | Example. Scribbr. Retrieved August 7, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-paper/outline/

Is this article helpful?

Courtney Gahan

Other students also liked, research paper format | apa, mla, & chicago templates, writing a research paper introduction | step-by-step guide, writing a research paper conclusion | step-by-step guide, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Adultery, Infidelity, and Divorce Research Paper

This sample divorce research paper on adultery, infidelity, and divorce features: 2400 words (approx. 8 pages) and a bibliography with 5 sources. Browse other research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Adultery and infidelity are major afflictions suffered in many long-term romantic relationships and are considered to be the most frequently cited reasons for divorce. Adultery can be defined as sexual intercourse between two people, one or both of whom are married but who are not married to each other. Infidelity is a term describing sexual relations between people outside the context of a marital relationship; it implies a romantic partner’s violation of relationship expectations or norms regarding emotional or physical intimacy. Infidelity is the most frequently cited cause of divorce, and it doubles the likelihood that a couple will end their marriage in divorce. Approximately 22 to 25 percent of married men and 11 to 15 percent of women engage in extramarital sexual relationships, although recent trends show that men’s and women’s rates of infidelity are becoming increasingly similar. Every year, it is estimated that between 1.5 percent and 4 percent of married individuals will engage in extramarital sex. In divorced couples, 40 percent of women and 44 percent of men reported more than one extramarital sexual contact during the course of their marriages.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code, risk factors for infidelity.

Risk factors for infidelity include gender, with men being more likely to have affairs; race, with African Americans being most at risk for infidelity; and age, with younger couples being more likely to commit adultery. Other risk factors are employment status, with those working outside the home more likely to cheat than those who do not; infrequency of church attendance; and low marital satisfaction. In young couples, factors like conscientiousness, religiosity, and marital satisfaction are related to a lower risk of potential infidelity in marriage, whereas openness to experiences of extramarital affairs, narcissism, impulsivity, social naïveté, alcohol use, discrepant levels of attraction between partners, and sexual dissatisfaction are all factors related to potential infidelity. Infidelity is more common among partners who regard their marriages in a negative light or who report sexual intercourse within their marriage to be low in frequency or quality. Furthermore, those who have more permissive attitudes toward sex outside a primary relationship and have a strong desire to engage in infidelity tend to do so.

While marriage generally serves as a deterrent and keeps many individuals from engaging in infidelity, a lack of marital happiness or satisfaction may contribute to an increase in infidelity in marriage relationships in some couples. At the very least, dissatisfaction in a marriage increases the desire for all types of involvement outside marriage: sexual, emotional, and combined sexual and emotional relationships. Most research suggests that sexual satisfaction in marriage also plays a part in an individual’s inclination toward infidelity. Both frequency and quality of sexual relationships in marriage have been negatively linked to the incidence of infidelity.

Length of relationship also contributes to infidelity. For married women, the likelihood of having an extramarital affair peaks during the seventh year of marriage and declines steadily after that; for married men, longer relationships are linked to a decreased likelihood of infidelity, until the 18th year of marriage, at which time the likelihood of infidelity increases.

Education also contributes to infidelity, with more highly educated people reporting higher rates of extramarital sexual activity, particularly when the spouses’ education levels differ. For instance, if a woman has more education than her partner, she is more likely to have an extramarital affair; if her partner has more education than she does, she is less likely to engage in infidelity. Education is also a predictor of marriage; those with more education are more likely to be married, thereby opening up the possibility that adultery (as opposed to extrarelational sexual activity between unmarried individuals) will occur.

Types of Infidelity

There may be emotional-only, sexual-only, or a combination of sexual and emotional types of infidelity; some scholars consider these categories on a spectrum of sexual and emotional involvement. Several typologies of affairs have been differentiated in research: (1) the affair that occurs within a conflict- avoidant marriage; (2) affairs that occur within the intimacy-avoidant marriage; (3) “out-the-door” affairs (having an affair with the purpose of leaving the relationship); (4) affairs related to sexual addiction; and (5) empty-nest affairs. Sexual infidelity may include one-night stands, same-sex encounters, emotional connections, long-term relationships, and philandering (multiple occurrences of infidelity) with another person outside the marital relationship, while emotional infidelity might consist of an Internet (chat room), work, or long-distance phone relationship. Some people who hold sexually conservative attitudes may consider engaging in masturbation or viewing pornography (or both together) an act of sexual infidelity.

Cyberinfidelity can result when one spouse becomes involved with a person over the Internet. Internet infidelities are based largely on emotional intimacy, as people engaging in these behaviors are gaining something from the online relationship that they have not received in their marriage relationship. Internet infidelity has been distinguished from traditional infidelity by three factors: accessibility, affordability, and anonymity. There is usually a great level of secrecy associated with Internet infidelity, as the involved partner can easily carry on the relationship without being discovered: rapidly closing chat windows, deleting conversations, and purging e-mail or message boxes. The level of secrecy combined with sexual excitement can lead to the buildup of a shared trust and a sense of solidarity between the individuals in the Internet relationship. Internet affairs are generally discovered by suspicious partners through e-mails and chat-room conversations found online or saved to a computer, rather than disclosure by the partner engaging in the extramarital relationship.

Culture, Race, and Infidelity

Infidelity is a phenomenon that has existed in almost all cultures throughout the course of history. When considering infidelity in other cultures, it is important to remember that cultural norms and values may vary between groups; thus, infidelity may be defined differently in couples whose partners have different ethnic, racial, or even religious backgrounds. Culture has a large influence on level of tolerance to extramarital relationships. While countries like Russia, Bulgaria, and the Czech Republic appear somewhat tolerant of extramarital sexual relationships, most countries that have been surveyed find there to be a strong disapproval of these types of affairs. Cultures with more liberal values generally have more permissive attitudes toward infidelity or sexual expression outside marriage.

Ethnic background has also been found to play a part in marital infidelity, although the association is unclear. Some research has shown little difference between white, Hispanic, and African American involvement in infidelity, while other studies have shown that African Americans are more likely to engage in extramarital relationships. Furthermore, African American and Hispanic men are more likely to report a correlation between sexual problems within the marital relationship and sexual infidelity than are white men.

Attitudes Toward Infidelity

Most people view extramarital relationships not only as a betrayal of the marital promise but also as a form of immoral or deviant behavior. Many factors influence individuals’ attitudes toward extramarital affairs. People who are well educated, from large metropolitan areas, have permissive attitudes regarding premarital sex, and people who are single or dissatisfied with their marital relationships are more accepting of extramarital relationships. Those who frequently attend church are less accepting of them. The expectation of sexual exclusivity and fidelity within a marriage relationship is steeped in trust, intimacy, and respect, and an incident of infidelity can do significant emotional damage to the foundation of the marriage. A spouse who has remained faithful may feel betrayed, become less satisfied with the marriage, and begin thinking about divorce upon discovering the partner’s infidelity. Likewise, the spouse who was unfaithful may become emotionally attached to the new partner, thereby becoming less committed to the marriage.

Impact on Couple Relationship

Extramarital affairs have been found to be quite damaging to marital relationships but are not always fatal to the marriage. When individuals marry, they usually assume that their relationship includes mutual feelings of fidelity, integrity, and safety within the permanent and exclusive commitment to the marriage. Because of these deeply rooted assumptions, when infidelity occurs, these beliefs are challenged and the experience can be particularly wounding to the parties involved. Deep hurt, betrayal, and a compromise of existing trust are often the result. Disclosure of infidelity is an emotionally charged event for most couples. Many times, it precipitates a roller coaster of emotions that vacillate between rage and disgust toward the offending partner as well as internal feelings including shame, depression, powerlessness, victimization, and abandonment in the nonoffending partner. Some researchers are beginning to equate the negative effects of discovering that a marital partner has been unfaithful and its corresponding emotional, behavioral, and cognitive responses with the responses associated with post-traumatic stress disorder.

Emotional trauma is often experienced by the partner whose spouse has been unfaithful. People who suffer infidelity often experience severe psychological trauma from a shattering of their assumptions about the commitment level in their relationships. Research on traumatic responses suggests that people are most likely to experience emotional trauma when their experiences violate even the basic assumptions they have about how the world works and how people operate in it. This is also the case with infidelity. When basic relational beliefs are violated, the injured person can lose a sense that the future is predictable and experience a loss of control. The affair can be traumatizing in the sense that the experience can shatter the core beliefs essential to a person’s emotional security.

In contrast, some mental health professionals argue that infidelity may not necessarily be detrimental to marital quality or stability, contending that for those who are able to differentiate between sexual and emotional fidelity (that is, the difference between “it was only sex” and “I think I’ve found my soul mate”), extramarital relationships can in some instances be healthy for traditional marriages. Some unintended positive outcomes of infidelity on marriages include closer marital relationships, increased assertiveness, placing higher value on family, realizing the importance of positive communication within the marriage, and better self-care on the part of each partner. Couples who recover successfully from infidelity typically view the occurrence as an eyeopener in terms of helping them reflect on how they allowed their relationship to get to a point where something as extreme as an affair could develop. Furthermore, some couples use the experience as an opportunity to focus more attention on strengthening the marital relationship to guard against any future infidelity.

However, research shows that only a small percentage of couples who experience infidelity actually improve their relationship quality. Negative consequences of infidelity on a couple include the betrayed partner’s reactions, such as rage, loss of trust, decreased personal and sexual confidence, lowered self-esteem, fear of abandonment, and feelings of justification for wanting to leave the relationship. Other adverse consequences include damage to other relationships (for example, impact on other family members once information is public), legal and financial consequences (job loss or transition if the affair is with a coworker, financial costs related to pregnancy and paternity concerns), and the introduction of sexually transmitted infections to the participants as well as to nonparticipating and unsuspecting spouses.

Many times, the decision to forgive or break up following infidelity depends on the nature of the discretion and also the gender of the spouse of the unfaithful. In general, men, relative to women, find it more difficult to forgive a partner’s sexual infidelity than a partner’s emotional infidelity; they are also more likely to break up in response to a partner’s sexual infidelity than in response to a partner’s emotional infidelity. On the other hand, women, relative to men, struggle with forgiveness and are more likely to break up with a partner who has been emotionally unfaithful. Furthermore, the overall level of relationship satisfaction, the motives behind the infidelity, the resulting level of conflict, and the attitudes about long-term infidelities all play large roles in a couple’s decision to remain married or not following the discovery of an extramarital affair.

Clinical Treatment for Infidelity

Therapists rank extramarital affairs as the problem causing the second-most damage to couple relationships after physical abuse, and much has been written about clinical issues and suggested guidelines for treating relationships struggling with issues of infidelity. Despite the plethora of clinical literature to address the issue, there has been little empirical research validating the effectiveness of the treatments. Two therapeutic approaches applied to couples seeking assistance after an affair are cognitive behavioral couple therapy (CBCT) and insight-oriented couple therapy (IOCT). CBCT uses skills-based interventions that target couple communication and behavior exchange by directing each partner’s attention to the explanations that they construct for each other’s behaviors and to the expectations and standards that they hold for their own relationship, providing focus and direction for the couple. By helping the couple to contain the emotional turmoil and destructive communication between the partners, the approach leads couples to explore factors that placed their relationship at risk for an affair and work toward a better relationship in the future.

IOCT works to help partners understand their current relationship struggles from the perspective of their spouse’s developmental history. Each partner’s previous relationships, affective components, and strategies for relating with others are the focus of treatment. By gaining a deeper understanding of their own and their spouse’s histories, the partners may develop more empathy and compassion for each other. As this connection develops, it is placed within a CBCT framework, in which the couple creates a set of attributions and a more positive narrative for the event, along with a focus for future change.

Recently, more attention has been given to the success of emotionally focused therapy (EFT) with couples who have experienced the trauma of infidelity. EFT is based on attachment theory and suggests that our intimate relationships are places where we have our greatest potential for experiencing personal growth and love, two uniquely human characteristics. Couples who have survived an affair are thought to have experienced an “attachment wound” and are given the skills and understanding necessary to rebuild trust and develop a sense of stability and security in the relationship. In this way, the couple relationship becomes a healing agent for all parties involved.

Bibliography:

- Blow, Adrian J. and Kelley Hartnett. “Infidelity in Committed Relationships II: A Substantive Review.” Journal of Marital and Family Therapy , v.31/2 (2005).

- Carder, Dave. Close Calls: What Adulterers Want You to Know About Protecting Your Marriage . Chicago: Northfield, 2008.

- Lusterman, Don-David. Infidelity: A Survival Guide . Oakland, CA: New Barhingerm, 1998.

- Snyder, Douglas K., Donald H. Baucom, and Kristina K. Gordon. Getting Past the Affair: A Program to Help You Cope, Heal, and Move On—Together or Apart . New York: Guilford Press, 2007.

- Spring, Janis Abrahms. How Can I Forgive You? The Courage to Forgive, the Freedom Not To . New York: Perennial Currents, 2004.

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Wiley - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Language: English | Spanish | Chinese

The Challenges of COVID‐19 for Divorcing and Post‐divorce Families

Jay l. lebow.

1 Editor, Family Process , Family Institute at Northwestern, Evanston IL

COVID‐19 and the accompanying procedures of shelter‐in‐place have had a powerful effect on all families but have additional special meanings in the context of families contemplating divorce, divorcing, or carrying out postdivorce arrangements. This paper explores those special meanings for these families. It also offers suggestions for couple and family therapists involved in helping these families during the time of COVID‐19.

La COVID‐19 y las normas de confinamiento que conlleva han tenido un efecto profundo en todas las familias, pero adquieren otros significados especiales en el contexto de las familias que están contemplando el divorcio, que se están divorciando o que están haciendo acuerdos posteriores al divorcio. Este artículo analiza esos significados especiales para estas familias. También ofrece sugerencias para los terapeutas de pareja y de familia implicados en ayudar a estas familias durante los tiempos de la COVID‐19.

摘要

COVID‐19及其随之而来的就地庇护禁足措施对所有家庭都产生了极大的影响,但对于以下几类家庭而言则更具有额外的特殊意义。它们指正在考虑离婚、办理离婚中或正在执行实施离婚后安排的家庭。本文探讨了对如上提及的这些家庭的特殊意义。本文还为在COVID‐19期间参与帮助这些家庭的伴侣治疗师和家庭治疗师提供建议。

The world is experiencing enormous stress with COVID‐19, and the broad impact on individual and family life clearly is pervasive (Lebow, 2020 ). This paper explores the special meanings and challenges for one set of families already experiencing a second major family stress, the prospect of divorce. The addition of the COVID‐19 stress to these evolving families is particularly salient. Research about divorcing families shows that, although divorce itself is mostly experienced as a stressor which most can process without severe long‐term consequences for mental health and functioning, the addition of other stressors to divorce potentiates negative effects on individual and relational functioning, placing family members at risk for a range of difficulties (Greene, Anderson, Hetherington, Forgatch, & DeGarmo, 2003 ; Lebow, 2019b ). This paper also presents possible ways of mitigating specific problems that emerge for those dealing with divorce during the time of COVID‐19 through systemic therapy.

Divorce represents a major watershed for family life (Lebow, 2019b ). Most families remain resilient, though highly stressed, through this transition. However, a significant percentage, estimated at 10–20% of the population, fall into processes of conflict and/or cutoff that make individual and relational problems more likely (Drozd, Saini, & Olesen, 2016 ). Other families divorce well, only to have other significant problems arise from parents forming new relationships or related to other changing aspects of child and family development. I describe the challenges of divorcing/divorced families as well as how therapists might best respond to these families in a recent book (Lebow, 2019b ). Here, I highlight the specific challenges that COVID‐19, and with it the much‐needed public health policy of shelter‐in‐place, present for these families.

Launching and Proceeding with the Divorce Process

The first place COVID‐19 impacts separation and divorce is in the launching of separation and divorce. Here, COVID‐19 both potentiates and constrains separation and divorce. On the potentiating side, for most families moving toward divorce, COVID‐19 and sheltering‐in‐place raise stress and create more rigid boundaries between the nuclear family and those outside the family. The now frequently blurred boundary between work and homelife provides new opportunities for conflict, as do the intensification of parenting roles and prevalence of other stressors, such as unemployment and income reduction. Many schools are closed and school‐aged children need to be home‐schooled as parenting roles get extended to becoming teachers and coaches for their children’s schoolwork and extra‐curricular activities. These additional parental responsibilities also increase work stress (especially for women who become responsible for most of these tasks), which readily spills over in couple relationships as roles need to be redefined. Young adult children returning home unexpectedly for undefined periods of time further adds to these stressors.

This can make for a hothouse of interaction during a time in which there are limited possibilities for escape into the outside world. In this context, the sort of cascade moving toward negative sentiment override, and divorce, described by Gottman and Gottman ( 2015 ), is enabled in which problems are readily magnified, Couples fall into angry exchanges without resolution or into patterns of demand‐withdrawal, which may degenerate into protracted high conflict and sometimes domestic violence. In parallel, social interactions and social support that might mitigate tensions are decreased. The intense environment that has emerged the wake of COVID‐19 leads many to greater intimacy, egalitarianism, and connection (see Stanley & Markman, 2020 ), but for those close to the fault line, acrimony and distance readily increases. In this intense confined environment, thoughts about the advantages of separating and divorcing are for many are intensified.

This all suggests that many more couples may begin divorce in the time of COVID‐19, and there have been early data suggesting this may be the case (Prasso, 2020 ). However, there are forces that move to constrain divorce as well. Divorcing usually occurs in some sporadic stepwise process of physically and emotionally separating households and dealing with several related legal issues having to do with the division of money and time with children. In the wake of COVID‐19, all of the specific tasks involved (e.g., deciding on who will move out, that person finding a place to live; showing the children their new home) are rendered so much more difficult. Even the well‐travelled recourse of one adult spending a few days in a hotel or with a neighbor or family member as a temporary step in the process is now fully dependent on such a hotel being open or that support person being prepared to deal with the COVID‐19 risks involved, and even then raising issues about quarantine. Further, many adults take the lead up to separation as sequential long periods away from the shared home. This becomes far less possible when everyone is at home all the time. Families also must multi‐task dealing with the other stressful aspects of COVID‐19 while attempting to launch divorcing. In the good divorce, parents typically handle the business of divorce away from children, but now children may be present all the time.

Further, the legal system is either not open or proceeding with a major backlog of cases. For most divorcing couples, filing for divorce has great meaning. Some choose not to file until all the details of divorce are worked out; this works very well among what Connie Ahrons calls “prefect partners” (Ahrons, 1994 ), those who continue good feeling along with the bad. However, for most divorcing partners there is a reality brought to what may have been threats or the voice of exasperation over the years by filing. That process is now much harder to launch or carry out. For those in violent homes, there also is the prospect of initiating action without typical levels of support in other times from the Court for such special circumstances.

A result is that, while thoughts and wishes to divorce look to be increasing with COVID‐19, the paths to divorce are more constrained. For many, this changes the process. Divorce is rarely an impulsive act. For most, it represents the culmination of a process of disconnection that typically is years in the making with some specific precipitant sparking a decision on the part of one or both partners to divorce. 1 Although the process of divorce is almost always ripe with possibilities for difficulty and legal systems for divorcing at times heighten these possibilities (Lebow, 2019b ), most people bring into the process a fairly clear template of the steps involved in relationship dissolution. Additionally, there is a great deal of useful popular psychoeducation about how to divorce, and the strategies for more successful parting are widely disseminated (Ahrons, 1994 ; Emery, 2016 ; Emery & Dinescu, 2016 ). As in the well‐known lyric by Paul Simon, there are fifty ways to leave your lover (and a few of those much better than others).

Many “divorcing” couples in the wake of COVID‐19 are not moving forward with divorcing; they are stuck in a developmental pause of undetermined time. Although this may have some positive ramifications (e.g., the possibility remains that this constraint might lead to a discernment decision to work further on the marriage before exiting; Doherty & Harris, 2017 ), more families than usual look likely to become caught up in a protracted hell. In these ways, a pattern typical of difficult divorce may come to be commonplace in more parting couples, in which both partners continue to live together without clarity about arrangements through this tumultuous time.

Here is a case example:

Cheryl and Max had been married for 20 years. Early in the relationship, they both enjoyed time with each other, but much of that time was centered on a contract out of awareness in which Cheryl soothed Max by deferring to him, especially in relation to his many anxieties and need for control. Over time, this core exchange no longer came to work for Cheryl, but Max’s anxiety was too great to allow him to move from this position of being needy and controlling. Max launched many stormy confrontations over a wide range of his complaints, and Cheryl withdrew. Just before COVID‐19 came to North America, Cheryl had told Max that she was planning to file for divorce. With the emergence of COVID‐19, there no longer was a mechanism to pursue living apart without the complete cooperation of the partners. Cheryl also feared that she would act in a way that might push Max to possibly harm her or himself. And in the one area they partnered well, the lives of their children, they were called upon to run a home school while doing their work at home. Thus, COVID‐19 both increased the levels of stress and problems, while also acting as a major block to parting.

Proceeding With Divorce

The problem is no less acute for those who are proceeding through divorce. Families involved in more typical divorce often perceive the process as excruciatingly slow. After COVID‐19, slowness can turn into a hard stop, particularly if there are difficult and contentious issues that need to be negotiated. Those who get into the legal system face closed or slowed courts. Although there may be processes for handling true emergencies and video versions of court, the system inevitably is less responsive.

Cooperative divorcing partners who enter the process may only be slightly affected given the availability of video mediation and related methods of alternative dispute resolution (Emery & Dinescu, 2016 ). However, for those with more complex issues and those who are at risk for difficult divorce, the divorce may stretch on, as a two‐year process moves to three years, three years to four years, etc. The online processes available in many jurisdictions are necessarily slower and a less than good fit with the sense of urgency of most at this stage of life and the need to establish some new working arrangement.

It is a bit of an anomaly in the world of couple and family therapy to speak of not being able to get divorced or having divorce decelerated as a problem. Yet, it is important to emphasize that divorce and the process of experiencing oneself as able to act on one’s wishes about who to spend one’s life with does act as a mechanism for mitigating anger, contempt, and other problematic feelings that Gottman and Gottman ( 2015 ), among others, describes as so pathogenic. The absence of there being a timely mechanism through which to disengage leaves many families in the most vulnerable position, and on some version of lockdown. This pressure cooker may only be in search of a spark to make for an explosion. Beyond the obvious risk to partners already in abusive relationships, there remain endless possibilities for painful, ongoing, destructive patterns of acrimonious conflict or contemptuous distance, which can lead to problematic impacts for all family members. And even if there are no spectacular events, an overly elongated period between marriage and life after is not helpful for anyone.

With such elongated periods, complexities grow. Many divorcing people may already be anchored in new relationships while they have yet to be divorced without anything that resembles infidelity. 2 Children grow older, and their needs change. Financial pictures also change. COVID‐19 itself has had an enormous impact on family finances. This, in turn, makes the resolution of conflicts over money more difficult. It also enables the fear that one or both parties will simply not have enough money once one household becomes two, which, in turn, becomes a constraint to resolution. Furthermore, in the overwhelming income inequality that has accompanied the pandemic, which includes a 20% unemployment rate in the United States, there may not be enough money to hire lawyers and separate households.

Processing One’s Experience

Divorce is a transition in which there are multiple tasks (Lebow, 2019b ). COVID‐19 creates a very special context for this experience, given that most people are home most of the time and multi‐tasking more than usual. Beyond its behavioral impact, there is the question of how adults and children can do the psychological work needed at this major life transition with less social support and while also dealing with anxieties about food, work, and health.

Postdivorce Conflicts

COVID‐19 is the enemy of planning. Thereby, more fragile postdivorce coparenting relationships and parent‐child relationships come to be at risk. One difficult topic is shelter‐in‐place and social distancing, which asks divorcing and divorced families to designate who is in and who is out of the family system. This is a challenge in nondivorced families, as parents often differ in their vantage points. For divorced parents, establishing a shared understanding about questions such as this one requires some degree of flexibility and the ability to collectively problem solve and compromise. For those who have difficult divorces, problems readily arise. These families typically benefit from clear articulation about the specifics of who is with whom when in their joint parenting agreement, but there are no instructions about what to do in a pandemic on which to fall back. For some, differences are monumental; for others, any difference becomes the fulcrum of a break down in cooperation.

Here is an example:

Lenny and Tom had considerable conflict over the four years since their splitting up but have maintained a steady schedule for when the children will be in which house. In the wake of COVID‐19, Tom moved to a rental home far away from the city in which both reside, taking the children with him. He argued that being away from the city, which was a COVID hotspot, was safer and that there was no way to share time there unless Lenny also rented a place nearby. That there was a lower prevalence of COVID‐19 away from the city was technically correct, but unilaterally changing the division of time was both illegal and a violation of the spirit of a coparenting agreement. This was followed by emergency motions through the court by Lenny and a series of cascading provocative actions between the parents that characterize difficult divorce.

Other postdivorce families who have established stable working relationships may be destabilized in other ways. Parents may live at a distance, but the distance may become far greater in a world in which there is a limited public transportation system. Schedules that center on school schedules must be worked with when there are no schools or camps. Standard agreements allocating time for vacations away take on new meanings in a time during which most people limit travel. Work schedules also have mightily changed. Routine is helpful to divorced families, and COVID‐19 disrupts such routines.

Couple and Family Therapy with Divorcing Couples in the Shadow of COVID‐19

COVID‐19 and public health procedures that accompany it have not changed the nature of divorce or the useful things that couple and family therapists do to help families who are dealing with divorce issues. Yet as already noted, this pandemic makes a difference in the context of divorce and calls for adaptations on the part of the therapist working with these families or their subsystems. In what follows, I speak to the adaptations to working with divorce in the time of COVID‐19. My comments are presented in the context of a view of working with divorce based in an integrative combination of generic therapy skill sets and special adaptations of those skill sets for working with divorcing families. The integrative model for engaging with divorcing families I suggest is described fully elsewhere (Lebow, 2019a , 2019b ), but the comments that follow are intended to apply to all therapists working with divorcing families whether or not they draw on that model.

As in all work with these families, safety concerns are the first consideration (Lebow, 2019b ). When there is a strong possibility of either physical or emotional danger for family members, the therapist needs to recognize this special circumstance. In the slowed and frequently stuck environment of COVID‐19, standard helpful ideas, such as the value of honesty and self‐disclosure, may need to take a backseat to promoting a holding action until separation and the assurance of safety is more feasible. The assessment of physical and emotional safety in an ongoing way is essential. When conflicts degenerate, initiating and maintaining an effective time‐out strategy is needed (Greenberg & Lebow, 2016 ) as is having a contingency plan for what to do if time‐out strategies fail.

Careful monitoring is also needed of how much the parental problem enters their interactions with children as well as the level of child exposure to interparental conflict, and most especially, intimate partner violence. Given the greater intensity and frequency of contacts in the typical home between parents and children in this time, therapists also need to assertively intervene to help families recognize such problematic patterns and move from them as much as possible. Psychoeducation, mindful practice, and cognitive restructuring that brings into focus the actual needs of the children can be very helpful in this regard (Lebow, 2019a ).

Similarly, the couple should be helped to monitor the frequency and value of the endless conversations that can be arise about divorce, especially the circle of blame for the demise of the marriage. Some such processing can be enormously helpful for many, both in terms of learning from this experience and processing emotion, but in a COVID‐19 environment with nowhere to go, such conversations can readily slide toward disaster.

Helping family members create individual space should also be in focus more broadly. Given that parting may be slower than normal and other outlets limited, creating some sense of boundaries for who is part of what space and when has considerable value (though many families don’t have the space for a comfortable version of that arrangement). This typically is a work in progress that requires attention over time. Closely related is the specific task of helping the family work together toward safe mutually agreed upon expectations for the various special decisions imposed by COVID‐19; for example, when to be in contact with whom?; when to wear masks?; etc.

It is also a time during which extra attention should be focused on the needs of the leaning in partner who questions getting divorced (Doherty & Harris, 2017 ). With the background stress from COVID‐19 so high and with social support significantly reduced, leaning in partners have a very special task. How to deal with that deep, once in a lifetime hurt without pulling one’s partner into what will be a destructive conversation? Some form of individual therapy with the leaning in partner, always a helpful option, now seems more needed than ever.

As to the steps in divorce, as in pre‐COVID times, helping clients to engage in a structured process is beneficial. Cooperation works much better than conflict. Mediation is vastly superior to conflict‐laden strategies in almost all families (Emery & Dinescu, 2016 ). Attorneys can more readily move on with the legal process to the extent there is cooperation. Helping parents collaborate and plan together about how to bring the children into the conversation about divorce also helps as does assisting them in identifying and planning for the needs of children through this time. So does helping the family find a structured arrangement mid‐way between marriage and divorce for this time that includes clear achievable expectations and can be a stepping‐stone to a more successful divorce. Assist the family (most especially, the divorcing couple) in seeing the value of a creating an overarching cooperative mindset aimed toward achieving shared goals for this time in the context of the realities of a slowed judicial system. The therapist’s role includes both helping the family move toward identifying and achieving the behavioral steps involved in divorce and enabling work on the psychological tasks underlying dealing with the dual stresses of divorce and the pandemic crisis. Therapy may involve one therapist working with the whole family or, when possible, multiple therapists working with different family subsystems; having multiple therapists is generally preferable but only is so when there is good coordination between the therapists.

There also are developments that increase risk that therapists can help families avoid. New partners in the time of COVID‐19 present additional foci for negative attention and present yet another stressful change at a time where too many changes often are too difficult to process. Clients (and their attorneys) should also be encouraged that this is not a good time for blaming petitions. If there are major conflicts over matters such as money, that might be dealt with later, postponing discussion of these issues may be advisable.

Research will uncover whether the impact of moving to teletherapy is more or less impactful than in‐person therapy with these families and their subsystems. My sense is that the ledger seems mixed. Divorce is a time where the calming presence of the therapist itself has great value, and that presence has to be diminished without physical presence. Similarly, attending to emotion is vitally important during this time but more difficult to engage at a distance, and thus the processing of emotion suffers. However, I also experience video conferencing as helpful in cooling conflict and providing distance that enables greater cooperation among family members. It also is far easier to move various family members in and out of zoom rooms to enable the most useful format for the work needed in a specific meeting than to do this in an in‐person meeting (Russell & Breunlin, 2019 ). And family members at home may be much more easily added to whatever unit began the therapy as is helpful. Additionally, parting partners and former partners are often relieved that there is no need to sit in the same room with their former partner during sessions, rendering conjoint treatment more acceptable (Lebow, 1982 ).

Finally, in the wake of COVID‐19, there is helping the family deal with the uncertainty of COVID‐19 itself. Will it be gone by the Fall (as one United States president has said) or will we be hunkered down for a decade? COVID‐19 and divorce share in being lessons in the value of radical acceptance. Here the acceptance the therapist must inevitably try to help clients to work through in one way also has a meaning in relation to this silent terrorist floating in the air.

1 Problems such as Infidelity, couple violence, and child abuse sometimes do make for more urgent and unexpected dissolution.

2 In this situation I am frequently amazed by how often this is referred to as infidelity.

- Ahrons, C. R. (1994). The good divorce: Keeping your family together when your marriage comes apart . New York: HarperCollins. [ Google Scholar ]

- Doherty, W. J. , & Harris, S. M. (2017). Helping couples on the brink of divorce: Discernment counseling for troubled relationships . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [ Google Scholar ]

- Drozd, L. , Saini, M. , & Olesen, N. (2016). Parenting plan evaluations: Applied research for the family court (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Emery, R. E. (2016). Two homes, one childhood: A parenting plan to last a lifetime . New York: Avery, an imprint of Penguin Random House. [ Google Scholar ]

- Emery, R. E. , & Dinescu, D. (2016). Separating, divorced, and remarried families. In Sexton T. L. & Lebow J. (Eds.), Handbook of family therapy (pp. 484–499). New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gottman, J. M. , & Gottman, J. S. (2015). Gottman couple therapy. In Gurman A. S., Lebow J. L. & Snyder D. K. (Eds.), Clinical handbook of couple therapy (5th ed.). New York: Guilford Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Greenberg, L. R. , & Lebow, J. L. (2016). Putting it all together: Effective intervention planning for children and families. In Drozd L., Saini M. & Olesen N. (Eds.), Parenting plan evaluations: Applied research for the family court . New York: Oxford University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Greene, S. M. , Anderson, E. R. , Hetherington, E. , Forgatch, M. S. , & DeGarmo, D. S. (2003). Risk and resilience after divorce. In Walsh F. (Ed.), Normal family processes: Growing diversity and complexity (3rd ed., pp. 96–120). New York: Guilford Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lebow, J. (1982). Consumer satisfaction with mental health treatment . Psychological Bulletin , 91 ( 2 ), 244–259. 10.1037/0033-2909.91.2.244 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lebow, J. L. (2019a). Current issues in the practice of integrative couple and family therapy . Family Process , 58 ( 3 ), 610–628. 10.1111/famp.12473 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lebow, J. L. (2019b). Treating the difficult divorce: A practical guide for psychotherapists . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lebow, J. L. (2020). Family in the Age of COVID‐19 . Family Process , 59 ( 2 ), 309–312. 10.1111/famp.12543 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Prasso, S. (2020). China’s divorce spike is a warning to the rest of locked‐down world . Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020‐03‐31/divorces‐spike‐in‐china‐after‐coronavirus‐quarantines

- Russell, W. P. , & Breunlin, D. C. (2019). Transcending therapy models and managing complexity: Suggestions from integrative systemic therapy . Family Process , 58 ( 3 ), 641–655. 10.1111/famp.12482 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stanley, S. M. , & Markman, H. J. (2020). Helping couples in the shadow of COVID‐19 . Family Process , 59 . 10.1111/famp.12575 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dissertation

- PowerPoint Presentation

- Book Report/Review

- Research Proposal

- Math Problems

- Proofreading

- Movie Review

- Cover Letter Writing

- Personal Statement

- Nursing Paper

- Argumentative Essay

- Research Paper

- Discussion Board Post

Tips On Writing Your Divorce Research Paper

Table of Contents

Although divorce law varies extremely from country to country and may be easier or more difficult, a huge amount of couples still make the decision to divorce.

The problem of the process of divorce is that it strikes every side of it, no matter how someone may look for it. It is also tough not only for husband and wife but also for children if there are any. The decay of a family is, for sure, a sorrowful action that may have not quite obvious negative effects.

This is exactly why the problem is newsworthy, just imagine that your research may save someone’s family one day!

What is divorce research paper all about?

If your assignment is to write a research paper on divorce, this means that you may choose any aspect of the problem and examine it. As the topic is an emotional one, I believe it won’t be difficult to decide what exactly you want to work on. Nevertheless, here are some useful hints for you:

- Think carefully what interests you most within the framework of divorce – that’s how you’ll approximately compose your topic.

- Make sure you are going to write about something not too broad or philosophical – research paper involves not only your own point of view but first of all, it is research.

- Be cautious with your tone – while writing about such problematic things, you may insult somebody’s feelings by accident.

- Follow the planned structure . You may find the guidelines below.

- Follow your teacher’s instructions . Here we are talking about the universal basis. Your teacher may have some specific requirements except for these.

How to write a research paper on divorce?

All research papers have some similar requirements. They are not difficult to follow and sometimes may even make your research better! So here is a little instruction for you on how to write a research paper on divorcement:

- Compose a well-targeted topic. That is important as this problem is too wide to discover it on the whole.

- Read a lot. Firstly, find some general information about divorce to understand the very basics. Then consult as many sources as needed on your specific topic. Remember that you should be aware of all the questions you’re going to write about.

- Make an outline. This will help you to structure your research and be logical in your presentation. Look through it and think whether your ideas are placed in a consequent way. The outline example you may find below.

- Structure. You should have three parts of your research – introduction, main body, and conclusion. They also need to be divided into paragraphs. A good idea is to write a separate paragraph for every new idea.

- References. Don’t close all your browser tabs at once after finishing writing! As a rule, you are to add a roster of the sources you’ve used for your research.

- Reread. If you haven’t written your research paper at the last hours before the deadline, it may be useful to leave it for a day or a couple and then reread it. You’ll be amazed at how you’ll see it with a clear mind! You may want to add or remove something.

- Check. Before handing your work over to a teacher, you should check it for possible lexical or grammar mistakes. Fortunately, there are lots of websites that can do that quickly and free.

Research paper on divorce outline

As you’ve already noticed, much attention is paid to the structure of the research paper. So below, you may find a two-in-one hint – an outline example for “Reasons for divorce” research paper and explanation of the structure.

Introduction . Here you are to give some background information, explain the problem, and introduce the reader to it.

The main reasons why couples divorce. It is the main body . Here you present all your statements. For this reason, it should be divided into subparagraphs.

- Infidelity.

- Money and financial well-being.

- Lack of support and communication.

- Misunderstanding and arguing.

- Issues with intimacy.

- Unrealistic expectations.

- Unreadiness for marriage.

Conclusion . The final of your work where you make an inference to what you’ve stated before. No new ideas or statements are needed here!

References . List of all your browser tabs and literature you’ve used for writing.

Divorce topics for research paper

If you still don’t know what you’d like to write your research work about or have difficulties composing a topic, here is a list of topics on various scopes of divorce. Don’t hesitate to pick up one or push out some ideas!

- The process of making a decision to divorce: reverse or irreversible moment?

- How can a couple predict and prevent a divorcement?

- What can the government do to prevent divorcements?

- Is there any divorce preventing measures done in your country? Do you think they are effective? Why?

- Describe and evaluate the divorcement procedure in your country. What are the pros and cons of it? What would be a perfect procedure, in your opinion?

- Positive and negative results of divorcement for a couple.

- Do you think there are more good or bad in divorcement? Why?

- Main reasons for divorcement.

- How should the property be divided when a couple divorces? Why?

- Which criteria should be prominent when deciding with whom a child will live?

- Research paper on divorce and children.

- Effect of divorce on society.

- How may a family psychologist help save a couple?

- What are groups of couples most likely to divorce? Why?

- What is the divorce tendency in your country? And in the world? What can it mean?

- Short- and long-term effects of divorcement.

- Differences in the culture of divorcement.

- Is there any real alternative to divorcement?

- Divorce as a social problem.

- Development of the divorce procedure in your country.

- Research paper on divorce and its effect on children.

Don’t be nervous if writing a research paper on divorce is still a challenge for you! Read this free sample and derive some ideas and inspiration.

To sum up, the problem of divorce is very up-to-date. It hurts thousands of people all around the world, and thus it’s worth highlighting.

Keep in mind that every research matters, so follow your heart, and it will be a success! Good luck!

Can’t wait to get your perfect on divorce? We can’t wait to deliver it to you! Click the button to order it in several clicks.

Tips on Writing a Persuasive Internet Censorship Essay

How to Begin Writing Essays about Mothers

Get your top-class fast essays on time

paperbag kits

- Custom term paper

- Writing on advanced materials

- Cover page formatting in Chicago

- Term paper proposal formatting

- APA research paper citations

- How to cite the Constitution?

- Turabian format

- Writing a proposal in MLA

- Getting literature review samples

- Creating an introduction

- Writing a college term paper

- History paper thesis statement

- Crafting a project in economics

- Finding a research paper service

- Project without a hypothesis

- Getting paper samples in business

- Discussion section samples

- Catchy 9th grade project titles

- Titles for an 8th grade paper

- Getting topics in physics

- Topics for middle school

- Ideas on human body

- Ideas in finance

- Criminal justice system

- Research paper title makers

- Buying term papers

- Creating an outline on divorce

- Writing a paper on racism in the US

- Getting 7th grade project examples

- Creating a paper on college majors

- Finding custom paper writers

- Writing a paper outline in anatomy

- Hiring a writing help service

- Writing help

- Buy a paper

5 Points To Include In Your Research Paper Outline On Divorce

Divorce is a very common research topic in both schools and colleges. And within divorce itself, the most common sub-topic is: The effects of divorce on children. Don’t be surprised if your teacher asks you to write an essay or a research paper on the topic this term/semester.

So, assuming that you have been asked to write a research paper on the: The effects of divorce on children, what exactly do you need to cover? We discuss five possible points below:

- Children will go through emotional an emotional distress

This is always a certainty. Whenever there is a divorce, the children who are left behind will be left to comprehend why their mum and dad had to go separate ways. It has also been shown that such children go through emotional distress as they confront anger, fear, and the feeling of abandonment. Sometimes, this can be reflected in their declining academic performance.

- Feeling of guilt

When a preschooler has to deal with the fact that they may never see mum and dad together again, they sometimes also start to feel a bit guilty. Did I cause the divorce? Did they go separate ways because of me? Is it because dad doesn’t want me around? All these questions might start running through the kid’s mind.

- Kids miss the parental care they need so much

A divorce also means that the kid has to live with just one parent. If this is the case, then they will dearly miss the parental care that would have been offered by the other parent. Whether that is their mum or dad, children need both parents when growing up. There are some things they can only learn so well from their mum and another set of things they can only learn so well from their father.

- Standard of living of the kid may be affected

If mum and dad were to go separate ways, and the kid left to stay with his or her mum, then assuming that the dad was the sole bread winner before the divorce, the child may suffer due to the lost financial support. They will now have to survive on a smaller budget.

- Children may lose confidence in marriage

Even though still young, children learn at every opportunity. When they see their parents drifting apart and eventually divorcing, they may start to look at marriages in a different way – most likely as something bad. I’ve found this site useful when looking for more points on divorce essays.

Professional Essay writing service - get your essays written by expert essay writer.

Expert essay writing services - they are writing essays since 2004.

For Writing

- Help with biology homework

- Writing on negotiation strategies

- Hiring good term paper writers

- Buy dissertations safety

- 8 tips on how to order term papers

- Composing a title page

- When hiring a writing service

- A thesis statement on gun control

- Getting a proposal in MLA

- Find a reliable writing help

- In quest of editing agencies

- Trustful writing agencies

- Hire a top notch writer

Popular Links

Good paper writing service - visit this site - 24/7 online. Writing my essay - easy guide. Get your paper done - expert paper writers. Dissertationexpert.org - best PhD thesis writing company.

Latest Post

- Components of a research project

- Writing a project on pricing strategy

2024 © PaperBagkits.com. All rights reserved.

Cookies on GOV.UK

We use some essential cookies to make this website work.

We’d like to set additional cookies to understand how you use GOV.UK, remember your settings and improve government services.

We also use cookies set by other sites to help us deliver content from their services.

You have accepted additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

You have rejected additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

- Crime, justice and law

- Courts, sentencing and tribunals

- HMCTS Vulnerability Action Plan

- HM Courts & Tribunals Service

HMCTS Vulnerability Action Plan April 2024 update

Updated 8 August 2024

© Crown copyright 2024

This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] .

Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned.

This publication is available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/hmcts-vulnerability-action-plan/hmcts-vulnerability-action-plan-april-2024-update

1. Introduction

Needing to use one of our services can be a daunting experience for anyone. It can be an even bigger challenge for the most vulnerable in our society.

We say that people are vulnerable when they have a difficulty and need extra support. This could be a disability, mental health condition or an experience which has made someone feel unsafe.

Our Vulnerability Action Plan shows how we aim to make our courts and tribunals accessible for everyone. It sets out what we’re doing to make sure our vulnerable users are not disadvantaged or discriminated against, as we deliver services now and in the future.

We’re committed to making sure we’re listening to people using our services who are more vulnerable, and our partners who support vulnerable groups. We’re working to adapt and improve our services to meet their needs. We’re working with our Ministry of Justice (MoJ) colleagues and other government departments to make sure we provide the right level of support. It’s important to us our vulnerable users can always access the justice system safely and with confidence.

2. Background

We’re committed to keeping our Vulnerability Action Plan up to date, we last published in October 2023 .

As before, this plan includes our work to design future accessible services.

We continue to focus on three priority areas. These are:

- providing our vulnerable users with support to access and participate in court and tribunal services and signposting to other sources of information and support when needed

- gathering and collating evidence and using it to identify impacts of changes on vulnerable users

- making our services accessible for vulnerable users.

We’ll continue to make sure our vulnerable users can access our services and will do this through:

- ongoing engagement with vulnerable users and our partners who support the needs of vulnerable groups

- implementing cross government strategies such as the National Disability Strategy , the National strategy for autistic children, young people, and adults , and the MoJ Neurodiversity action plan

We continue to support vulnerable people to access and participate in court and tribunal services by:

- ensuring special measures continue to be in place.

Special measures are provisions which can be put in place to support vulnerable users, the type of support will depend on the case or hearing as special measures are not the same in all jurisdictions. Examples of special measures include providing a remote link to give evidence and the use of screens in court.

providing reasonable adjustments for users with disabilities . Reasonable adjustment is the name used in the Equality Act 2010 for something we can put in place to help users with disabilities. Examples of reasonable adjustments include providing our information in an alternative format e.g. in audio or easy read, helping someone complete a form or providing a chair to meet a user’s specific need

providing intermediary services if users need communication support at a court or tribunal hearing. Intermediaries are communication specialists who work on behalf of HMCTS to support people participating in a court or tribunal hearing. They provide impartial recommendations to HMCTS about a person’s specific communication needs and outline the steps needed to achieve them

using remote hearing links and providing users with information about video hearings . This includes a website link, details of how to join the hearing and what to do if they need support

completing equality impact assessments to understand the potential impacts of change on users with protected characteristics. It is against the law to discriminate against anyone because of age, gender, marital status, being pregnant, disability, race, religion or belief, sex, sexual orientation. These are called protected characteristics

publishing a range of information and guidance on GOV.UK to prepare users and reassure them about coming to a court or tribunal

signposting people to additional support that will help them. With the right information, we can identify the user’s needs and connect them to external support services

providing Hidden Disabilities Sunflower lanyards. People who choose to wear the Hidden Disabilities Sunflower are discreetly indicating they need additional support, help or a little more time.

3. What we’ve done since our last update

3.1 providing our vulnerable users with support to access and participate in court and tribunal services and signposting to other sources of information and support when needed.

Cross Jurisdictional

- Single Justice Service (SJS)

- Online Civil Money Claims (OCMC)

- launched a cross-jurisdictional Help with Fees scheme targeted at the financially most vulnerable in November 2023. New digital and paper applications can be submitted by the applicant who needs to pay the fee, their Legal Representative or Litigation Friend. The service has support from the ‘We Are Group’ contract

- extended the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) funded Witness Service contract with Citizens Advice.

Civil, Family and Tribunals

introduced a webchat option for Employment Tribunal users in Scotland and are monitoring how it is being used. Help to use the system is available via the Employment Tribunal service centres

agreed each region will have a designated domestic abuse champion

- completed domestic abuse training with operational staff in the Family jurisdiction

- continued testing Family Private Law applications for litigants in person to see how we can improve the system for applicants. Private Law cases are between family members, such as parents or other relatives and do not involve Local Authority.

- continued to support the introduction of Community Sentence Treatment Requirements (CSTR’s) and Mental Health Treatment Requirements (MHTR’s) in all courts in England and Wales. This means judiciary can consider Drug Rehabilitation Requirement (DRR), Alcohol Treatment Requirement (ATR) and secondary care MHTR’s when sentencing

held a number of pre-recorded cross examinations in care homes or private residences for individuals who are unable to attend court or travel. Normally these witnesses will be receiving end of life care or have a debilitating illness which would result in their evidence being compromised if they need to wait for the trial

- made improvements to the three Specialist Sexual Violence Support (SSVS) courts, including facilities and technology upgrades, to make sure special measures can be better accommodated, and victims feel more comfortable.

3.2 Gathering and collating evidence and using it to identify impacts of changes on vulnerable users

- Social Security and Child Support (SSCS)

- Divorce and

These assessments help identify common barriers to accessing justice, what causes these barriers and what might help remove them

- continued to collect protected characteristics data, which will help us gain a fuller understanding of people who use our services.

- worked with HM Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS) to make sure they are notified of non-molestation orders. Non molestation orders protect people from abuse or harassment. This will help HMPPS manage offender behaviour to prevent protected parties from receiving unwanted contact.

3.3 Making our services accessible for vulnerable users

tested the Video Hearing Service in the crime jurisdictions, which is now live in 16 sites across civil, family and tribunals. With the permission of the judge, video hearings allow participants to attend a hearing remotely

announced that we will spend £220 million to maintain, improve and modernise our buildings to increase the accessibility of our estate.

- made it possible for parties to apply digitally for a final divorce order when over 12 months old.

4. Our plan

4.1 providing our vulnerable users with support to access and participate in court and tribunal services and signposting to other sources of information and support when needed.