- Midlands State University

Essay writing is a recursive process. Discuss?

Top contributors to discussions in this field.

- The World Islamic Science and Education University (WISE)

- University of Saskatchewan

- Federal University of Technology, Akure

- Otto-von-Guericke-Universität Magdeburg

- Gumushane University

Get help with your research

Join ResearchGate to ask questions, get input, and advance your work.

All Answers (3)

- recursi ve.jpg 49.60 KB

Related Publications

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Guide to Writing at Stetson University

- You the Writer

Writing as a Process: Writing is Recursive

Know the right moves for college writing, build an argument, not an opinion, is every assignment an argument, know the two most important kinds of sentences: thesis and topic sentences, introduce your sources with purpose and show relationships between ideas.

Understand and Use Sophisticated Punctuation

- Speaking and Writing English (when it isn’t your first language)

- Writing in the Disciplines

- University Writing Rubric

- A Biology grade rubric

- The Four Point scale

- General Descriptive Rubric

- Information Literacy and Fluency (Research Fundamentals)

- General Citations

- Copyright Basics

- The Writing Reference

Writing is a process. Writers don’t just sit down and produce an essay, well-formed and ideal in every respect--we work at the stages and steps. But writing is not only a process: it’s also a measure of learning and your thinking, and so the process has to stop at various points so that your measure can be taken. Good academic writing is both a process and a product.

Writing is recursive. “Recursive” simply means that each step you take in your writing process will feed into other steps: after you’ve drafted an essay, for instance, you’ll go do a bit of verification of some of your facts—and if you discover that you’ve gotten something wrong, you’ll go back to the draft and fix it. But doing that may well require you to loop back to a different section of your essay to rewrite or to take it out altogether-and that revision, in turn, might mean that you need to rethink your organization. At some point, you know that the work is done.

To be successful at college-level writing, students need to be willing to learn the new moves. Writing for the demands of college is challenging, but it can be a little easier if students understand up front that readers at the college level expect to see certain skills be demonstrated.

- Know what a college-level essay looks like in the appropriate discipline (your professors should show you examples)

- Keep the focus of your work narrow (don't take on too much! Given the choice, go deep rather than broad)

- Compose and revise to create a thesis statement and topic sentences

- Introduce your sources with a purpose

- Show relationships between ideas

- Use sophisticated punctuation

Know What a College Level Essay Looks Like (generally)

While professors at Stetson have specific expectations for what their students turn in, students may not always understand the depth for the expectations. Some professors will show examples of what they want; some will not. In general, while each of your professors will provide a clear assignment, students may benefit from seeing an outline of what that assignment might entail.

The key differences are several:

- The need for a clear and directive thesis or purpose statement;

- The expectation of substantial consideration of other viewpoints and perspectives;

- The use of sources to develop and explore a point made by the writer (not just to support the point itself); and

- The need for the conclusion to do something other than summarize

Know What a College Level Essay Looks Like (in your discipline)

Not every assignment students get at Stetson will look like the above list. For example, writing assignments in Life Sciences prioritize a clear discussion of methods and results, often to test the work of others (in which case, using sources "to explore a point" may look very different. Ask your instructor to help you with these differences.

- Here is a link to a video that demonstrates how to write a college-level essay.

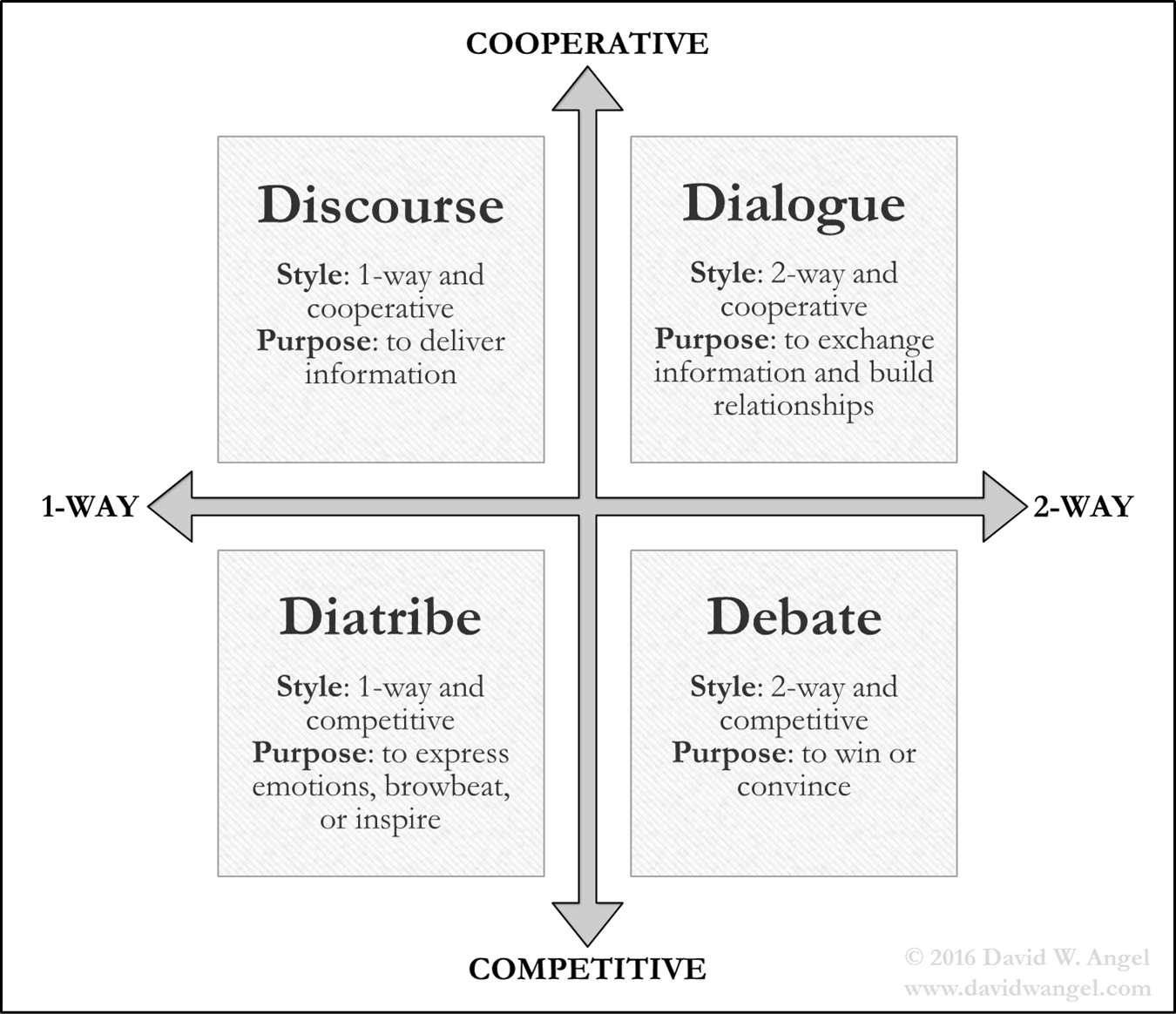

Many students come to college thinking that “arguing” in an essay means to present a well- supported position. The definition of “argue” thus becomes a defense rather than an inquiry. In the real world, we're accustomed to "arguing" as trying to win. In college, "arguing" means to present a line of thought that takes into account different perspectives, additional evidence, and new ideas as it comes to a conclusion. In other words, a strong argument is one that incorporates both sides effectively.

Sophisticated thinkers and writers seek to advance and deepen the understanding via discussion; thus, at college we seek to encourage deeper discussions with the goal to have a richer and fuller understanding. To do this well, it’s important to go deeply into a subject rather than stay on the surface. While the approach of defending a position rather than exploring its layers may feel somewhat easier, there are only so many ways to learn from general subjects; we learn more, and find opportunities for growth and development more easily, when we narrow down the field of interest. As we work with an idea and consider it carefully, we continue to narrow it down, zeroing in on a particular angle or position that interests us and meets the needs of the assignment.

Identifying a position requires several steps:

- First , understand the subject area from which the argument must come.

- Second , break that subject area down into topics

- Third , focus on developing a question whose answer can be identified and defended. As the subject undergoes continual narrowing and focusing, specific questions develop; the reasoned, detailed, careful answer to those questions becomes the argument.

- Fourth , read, research, and discuss the potential answers to the question you’re asking so that your writing is multidimensional and well supported. The Guide’s chapter on “Using Your Resources” deals with this element of the process.

Remember: A true argument requires that other perspectives be taken into account, because once you have found a focus and can easily develop an opinion or come to a position on the questions that have been created, this can provide an opportunity for a discussion, exploration of different perspectives, and dialogue about values.

- Opinion : statement of writer’s general attitude toward a specific subject, issue or event

- Position : announcement of writer’s general attitude toward a specific subject, issue, or event, with explanation of reasons

- Argument : statement that captures a spirit of debate and discussion about a specific topic, issue, or event

Not every writing assignment students get in their courses will be an argument essay. As mentioned earlier, students here write lab reports, correspondence, proposals, brochures, arguments, applications, evaluations, analyses, and host of others.

We also ask that students consider and evaluate questions and ideas, formulate their own responses to those ideas, and then do something with those responses: argue, defend, propose, compare, and analyze are some of the things we do with our responses to ideas. Each kind of assignment has a different purpose.

Generally speaking, arguments take two kinds of shapes: one is a shape that actively argues with its reader from the start, presenting its position and systematically defending against its opposition by marshalling evidence that will defeat an opposing viewpoint. This focuses on difference. One other popular shape starts from a position of unity and common ground, and then, as each element of common ground on a position is discussed, the writer’s position becomes clearer.

Not every writing assignment students get in their courses will be an argument essay. As mentioned earlier, students here write lab reports, correspondence, proposals, brochures, arguments, applications, reflections, evaluations, analyses, and many others.

A strong writer develops through practice in a variety of forms and audiences and purposes. That's why Stetson requires you to have four different writing-enhanced (WE) courses. The practice helps build "muscle" and a set of strategies to respond to new situations.

Students consider and evaluate questions and ideas, formulate their own responses to those ideas, and then do something with those responses. Argue, defend, propose, compare, and analyze are some of the things we do with our responses to ideas. Each kind of assignment has a different purpose.

Generally speaking, arguments take two kinds of shapes: one is a shape that actively argues with its reader from the start, presenting its position and systematically defending against its opposition by marshalling evidence that will defeat an opposing viewpoint. This focuses on difference. One other popular shape starts from position of unity and common ground, and then, as each element of common ground on a position is discussed, the writer’s position becomes clearer.

- Here is a link that shows brief examples and descriptions of what assignments students may encounter at Stetson.

Thesis statements and topic sentences perform nearly the same function in your writing: each one makes a claim, or states a main idea, and each one serves as a central focus connecting ideas presented earlier and leads to ideas about to come.

A classic thesis statement demonstrates three specific elements:

- It states a main idea, which the essay will go on to explain and develop

- It goes beyond statements of fact or announcement-type statements

- It offers the reader some idea of the direction of the essay

Whereas a thesis statement captures the main idea of an essay and provides structure and direction, a topic sentence introduces a paragraph’s main claim or idea. When we read a well put- together paragraph, we can identify the topic sentence relatively easily: it’s the one making a claim, and the other sentences are adding support and explanation. We typically find the topic sentence of a paragraph at the starting or ending position; at the start of a paragraph, the topic sentence makes a claim or point that will then be developed and supported. At the close of the paragraph, the topic sentence brings the reader to a conclusion that's just been made.

Introduce Your Sources With Purpose

Inexperienced writers often us this particular technique:

“Prostitution in Dubai is ruining the city’s reputation” (Alexis).

While functional, this approach to using a source is so minimal as to be almost ineffective. Note, for example, that the reader has not been told who "Alexis" is, what their credentials are, where this information has come from (and whether it is credible.)

However, look at the difference between that example and the next, paying close attention to the introduction of the source as well as the mention of the origin of the source material:

Shakar Alexis, a prominent sociologist, warns in Dubai News that “Prostitution in Dubai is ruining the city’s reputation” (Alexis).

In the second example, the student has introduced the speaker using their full name, has provided the reader with some idea of the speaker’s credentials, and has given the source of the speaker’s words. Finally, in the parentheses, the student has documented the source. Note also that the student has used an effective verb, "warn," to introduce and characterize the quotation.

Choosing your words and embedding useful information carefully provides readers with a richer, more complete experience.

Show Relationships between Ideas

Your writing should show your thinking forms a whole. That is, your thinking forms a coherent unified idea by using transitional words and phrases. These may be used between paragraphs, to show the big connections among the ideas in your writing, or between sentence, to show the train do thinking that leads you to connect one claim to the next.

This chart provides a useful reference for students looking for just the right word to show the relationship between two paragraphs’ or two sentences’ main ideas:

Sentence punctuation involves using commas, semicolons, colons, periods, parentheses, and dashes to coordinate sections of sentences (phrases and clauses) into coherent wholes.

An independent clause is one that can function on its own as a sentence: it has a subject and a verb. It looks like a complete sentence. When you put together independent clauses, you need to signal that coordination with some sort of punctuation.

Link independent clauses in four ways :

- Comma plus conjunction : I wasn’t ready for school to start, but it started anyway

- Semicolon : I wasn’t ready for school to start; it seemed like summer should have stretched on forever

- Semicolon and transitional word/phrase : I wasn’t ready for school to start; however, the first day turned out to be enjoyable.

- Colon : I wasn’t ready for school to start: time had sped past me all summer

Link items in a series with some sort of punctuation . You can use commas or semicolons depending on your intended effect:

- Commas : We can look at the increased coral deaths, melting polar ice caps, and the gradual decline of biodiversity as evidence of climate change.

- Semicolons : Resolving the climate problems will take increased attention from governments; stronger sanctions for violators; and a genuine realization that our species is in trouble.

Colons and dashes set off examples and explanations so that each one gets the proper attention from the reader:

- Colons : It doesn’t get any easier than this: I can pass some of my classes just by doing the work.

- Dashes : I can pass some of my classes just by doing the assignments—I guess that means I’d better schedule time for homework.

Use colons, dashes, and parentheses to set off the important information from the rest of the sentence:

- Commas : Before we can tackle our serious problems, most importantly humanitarian crises in Darfur and the African continent, we have to admit that they exist.

- Dashes : It doesn’t take much milk to make pancakes--just a cup or so will do it--but using skim milk instead of whole milk will reduce calories.

- Parentheses : I know a lot about being a student (but I don't know much about how to get a job after this).

- Punctuation Overview at Purdue

- The Punctuation Guide

- << Previous: You the Writer

- Next: Speaking and Writing English (when it isn’t your first language) >>

- Last Updated: Jun 20, 2024 6:06 PM

- URL: https://guides.stetson.edu/WritingGuideStetsonU

Have a question? Ask a librarian! Email [email protected]. Call or text 386-747-9028.

- Mailing List

- Search Search

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

Resources for Writers: The Writing Process

Writing is a process that involves at least four distinct steps: prewriting, drafting, revising, and editing. It is known as a recursive process. While you are revising, you might have to return to the prewriting step to develop and expand your ideas.

- Prewriting is anything you do before you write a draft of your document. It includes thinking, taking notes, talking to others, brainstorming, outlining, and gathering information (e.g., interviewing people, researching in the library, assessing data).

- Although prewriting is the first activity you engage in, generating ideas is an activity that occurs throughout the writing process.

- Drafting occurs when you put your ideas into sentences and paragraphs. Here you concentrate upon explaining and supporting your ideas fully. Here you also begin to connect your ideas. Regardless of how much thinking and planning you do, the process of putting your ideas in words changes them; often the very words you select evoke additional ideas or implications.

- Don’t pay attention to such things as spelling at this stage.

- This draft tends to be writer-centered: it is you telling yourself what you know and think about the topic.

- Revision is the key to effective documents. Here you think more deeply about your readers’ needs and expectations. The document becomes reader-centered. How much support will each idea need to convince your readers? Which terms should be defined for these particular readers? Is your organization effective? Do readers need to know X before they can understand Y?

- At this stage you also refine your prose, making each sentence as concise and accurate as possible. Make connections between ideas explicit and clear.

- Check for such things as grammar, mechanics, and spelling. The last thing you should do before printing your document is to spell check it.

- Don’t edit your writing until the other steps in the writing process are complete.

The Recursive Writing Process

Author Louis L’Amour said, “Start writing, no matter what. The water does not flow until the faucet is turned on.”

But how do you go about writing an essay, a story, or a novel? How do you even get started? One method of writing that can help is the recursive writing process .

The recursive writing process can be broken down into four simple steps:

Because this process is recursive, you can revisit old steps after you’ve moved on to the editing process.

Prewriting happens before a single word goes on the page. This includes things like choosing a topic. Are you going to write about something you know personally? Are you writing about a historical event? Maybe your topic is fictional!

Whatever you choose to write about, you will need to do some brainstorming . How long will it be? What format will it be in? Will you have dialogue, or will it be a research paper with citations ?

Every type of writing requires different preparation. For a research paper, you might need to find online sources, peer-reviewed journals, or even interviews of experts on the topic. A science-fiction story might need research into how things like lasers and spacecraft work. Historical fiction might have you looking into styles of dress and manners of that time period.

Using an outline will help you break down and organize the different parts of your paper. There may be changes as you go along, but an outline helps you visualize your writing as a whole so it doesn’t end up choppy and confusing for the reader to follow.

Once you finish your outline, it’s time to write your first draft. When you start writing, you do not have to start with the intro. Sometimes it is easier and better to start in the middle of your paper and add the intro in later.

You can break down your middle into different points or different sources. Having one paragraph per source is usually the way to go. This makes it easy for the reader to pay attention to each source individually while still being aware of how all the sources come together to make sense of the overall topic.

Once your first draft is complete, you’ll need to start revising . Revising is the point at which you start polishing up your work. You should start to cut things out of your work and add clarity to it. Sentences that go nowhere, unneeded descriptions, and repetitive words need to be removed. If ideas can be condensed from a paragraph to a sentence, do it! Unless you have a mandatory word count, less with clarity is much better than more with repetition.

It can be very helpful to have a friend read your paper during this stage. Does everything make sense to them? Can they give you a summary of what you wrote about easily, or is there too much going on for them to grasp it all? If your reader can’t summarize what you wrote, then they typically did not understand what you wrote.

Editing is making your writing polished and ready to be presented. Now is the time to use spell check, grammar check, and even search for improperly used words that often get overlooked.

Check over your citation use, and make sure each separate idea gets its own paragraph. Also, check your use of transition words!

Editing is the last step; you should not worry about editing your paper until everything else is ready to go.

This is when you correct any tiny mistakes you may have missed and add your title. Chapter headings, bibliographies, and all additional pages should be added in the editing process if they have not been created yet. If you have guidelines you need to follow, such as font size, margin width, and spacing this is also the time to give those a final look over.

Once your paper is edited, you’re done! These four steps of the recursive writing process seem easy once you get to the end, but they are a huge help when you are getting started. So whether you are writing an essay for school or working on the next bestselling novel, you can use the recursive writing process to make your writing flow.

Thanks so much for watching. See you next time and, as always, happy studying!

Return to Writing Videos

by Mometrix Test Preparation | Last Updated: July 27, 2023

Composition Resources

Writing Is Recursive

Christopher Blankenship

In a recent interview , Steven Pinker, Harvard professor and author of The Sense of Style: The Thinking Person’s Guide to Writing in the 21st Century , was asked how he approaches the revision of his own writing. His answer? “Recursively and frequently.”

What does Pinker mean when he says “recursively,” though?

U.S. Constitution

You’re probably familiar with the root of the word: “cursive.” It’s the style of writing that you may have been taught in elementary school or that you’ve seen in historical documents like the Declaration of Independence or Constitution.

“Cursive” comes from the Latin word currere , meaning “to run.” Combine this meaning with the English prefix “re-” (to do again), and you have some clues for the meaning of “recursive.”

In modern English, recursion is used to describe a process that loops or “runs again” until a task is complete. It’s a term often used in computer science to indicate a program or piece of code that continues to run until certain conditions are met, such as a variable determined by the user of the program. The program would continue counting upwards—running—until it came to that variable.

So, what does recursion have to do with writing?

You’ve probably heard writing teachers talk about the idea of the “ writing process” before. In a nutshell, although writing always ends with the creation of a “product,” the process that leads to that product determines how effective the writing will be. It’s why a carefully thought-out essay tends to be better than one that’s written the night before the due date. It’s also why college writing teachers often emphasize the idea of process in their classes in addition to evaluating final products.

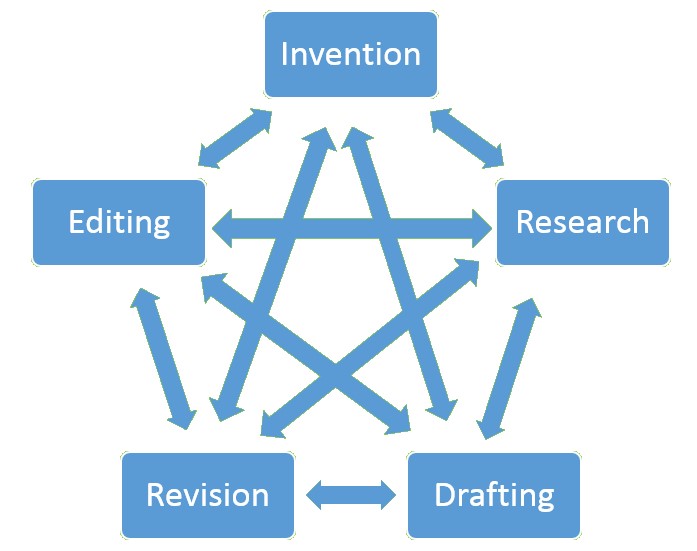

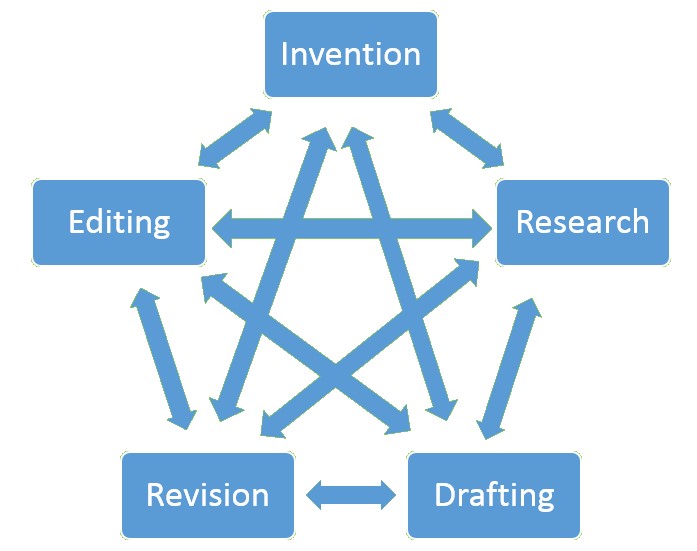

There are many ways to think about the writing process, but here’s one that my students have said makes sense to them. It involves five separate ways of thinking about a writing task:

Invention: Coming up with ideas.

This can include thinking about what you want to accomplish with your writing, who will be reading your writing and how to adapt to them, the genre you are writing in, your position on a topic, what you know about a topic already, etc. Invention can be as formal as brainstorm activities like mind mapping and as informal as thinking about your writing task over breakfast.

Research: Finding new information.

Even if you’re not writing a research paper, you still generally have to figure out new things to complete a writing task. This can include the traditional reading of books, articles, and websites to find information to cite in a paper, but it can also include just reading up on a topic to learn more about it, interviewing an expert, looking at examples of the genre that you’re using to figure out what its characteristics are, taking careful notes on a text that you’re analyzing, or anything else that helps you to learn something important for your writing.

Drafting: Creating the text.

This is the part that we’re all familiar with: putting words down on paper, writing introductions and conclusions, and creating cohesive paragraphs and clear sentences. But, beyond the words themselves, drafting can also include shaping the medium for your writing, such as creating an e-portfolio where your writing will be displayed. Writing includes making design choices, such as formatting, font and color use, including and positioning images, and citing sources appropriately.

Revision: Literally, seeing the text again.

I’m talking about the big ideas here: looking over what you’ve created to see if you’ve accomplished your purpose, that you’ve effectively considered your audience, that your text is cohesive and coherent, and that it does the things that other texts in that genre do.

Editing: Looking at the surface level of the text.

Editing sometimes gets lumped in with revision (or replaces it entirely). I think it’s helpful to consider them as two separate ways of thinking about a text. Editing involves thinking about the clarity of word choice and sentence structure, noticing spelling and grammatical errors, making sure that source citations meet the requirements of your citation style, and other such issues. Even if editing isn’t big-concept like revision is, it’s still a very important way of thinking about a writing task.

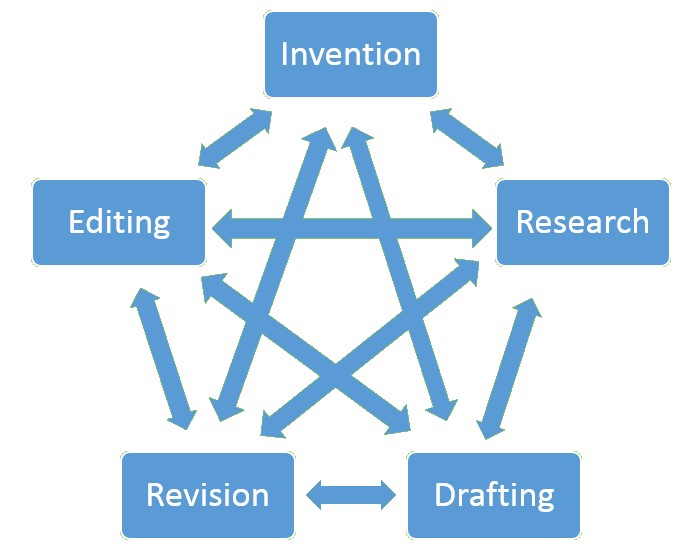

Now, you may be thinking, “Okay, that’s great and all, but it still doesn’t tell me what recursion has to do with writing.” Well, notice how I called these five ways of thinking rather than “steps” or “stages” of the writing process? That’s because of recursion.

In your previous writing experiences, you’ve probably thought about your writing in all of the ways listed above, even if you used different terms or organized the ideas differently. However, Nancy Sommers, a researcher in rhetoric and writing studies, has found [1] that student writers tend to think about the writing process in a simple, linear way that mimics speech:

This process starts with thinking about the writing task and then moves through each part in order until, after editing, you’re finished. Even if you don’t do this every time, I’m betting that this linear process is probably familiar to you, especially if you just graduated high school.

On the other hand, Sommers also researched how experienced writers approach a writing task. She found that their writing process is different from that of student writers:

Unlike student writers, professional writers, like Steven Pinker, don’t view each part of the writing process as a step to be visited just once in a particular order. Yes, they generally begin with invention and end with editing, but they view each part of the process as a valuable way of thinking that can be revisited again and again until they are confident that the product effectively meets their goals.

For example, a colleague and I wrote a chapter for a book on working conditions at colleges, a topic we’re interested in.

- When we started, we had to come up with an idea for the text by talking through our experiences and deciding on a purpose for the text. [Invention]

- Although we both knew something about the topic already, we read articles and talked to experts to learn more about it. [Research]

- From that research, we decided that our original idea didn’t quite fit with the research that was out there already, so we made some changes to the big idea. [Invention]

- After that, we sat down and, over several sessions on different days, created a draft of our text. [Drafting]

- When we read through the text, we discovered that the order of the information didn’t make as much sense as we had first thought, so we moved around some paragraphs, making changes to those paragraphs to help the flow of the new order. [Revision]

- After that, we sent the rough draft to the editors of the book for feedback. When we got the chapter back, the editors commented that our topic didn’t quite fit the theme of the book, so, using that feedback, we changed the focus of the ideas. [Invention]

- Then we changed the text to reflect those new ideas. [Revision]

- We also got feedback from peer reviewers who pointed out that one part of the text was a little confusing, so we had to learn more about the ideas in that section. [Research]

- We changed the text to reflect that new understanding. [Revision and Editing]

- After the editors were satisfied with those revisions, we proofread the article and sent it off for final approval. [Editing]

In this process, we produced three distinct drafts, but each of those drafts represents several different ways that we made changes, small and large, to the text to better craft it for our audience, purpose, and context.

One goal of required college writing courses is to help you move from the mindset of the student writer to that of the experienced writer. Revisiting the big ideas of a writing task can be tough. Cutting several paragraphs because you find that they don’t meet the purpose of the writing task, throwing out research sources and having to search for more, completely reorganizing a text, or even reconsidering the genre can be a lot of work. But if you’re willing to put aside the linear steps and view invention, research, drafting, revision, and editing as ways of thinking that can be revisited over and over again until you accomplish your goal, you will become a more successful writer.

Although your future professors, bosses, co-workers, clients, and patients may only see the final product, mastering a complex, recursive writing process will help you to create effective texts for any situation you encounter.

- “Revision Strategies of Student Writers and Experienced Adult Writers” in College Composition and Communication 31.4, 378-88. ↵

Writing Is Recursive Copyright © by Christopher Blankenship is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Writing Is Recursive

Chris Blankenship

In a recent interview , Steven Pinker, Harvard professor and author of The Sense of Style: The Thinking Person’s Guide to Writing in the 21st Century , was asked how he approaches the revision of his own writing. His answer? “Recursively and frequently.”

What does Pinker mean when he says “recursively,” though?

You’re probably familiar with the root of the word: “cursive.” It’s the style of writing that you may have been taught in elementary school or that you’ve seen in historical documents like the Declaration of Independence or Constitution.

“Cursive” comes from the Latin word currere , meaning “to run.” Combine this meaning with the English prefix “re-” (to do again), and you have some clues for the meaning of “recursive.”

In modern English, recursion is used to describe a process that loops or “runs again” until a task is complete. It’s a term often used in computer science to indicate a program or piece of code that continues to run until certain conditions are met, such as a variable determined by the user of the program. The program would continue counting upwards—running—until it came to that variable.

So, what does recursion have to do with writing?

You’ve probably heard writing teachers talk about the idea of the “ writing process” before. In a nutshell, although writing always ends with the creation of a “product,” the process that leads to that product determines how effective the writing will be. It’s why a carefully thought-out essay tends to be better than one that’s written the night before the due date. It’s also why college writing teachers often emphasize the idea of process in their classes in addition to evaluating final products.

There are many ways to think about the writing process, but here’s one that my students have said makes sense to them. It involves five separate ways of thinking about a writing task:

Invention: Coming up with ideas.

This can include thinking about what you want to accomplish with your writing, who will be reading your writing and how to adapt to them, the genre you are writing in, your position on a topic, what you know about a topic already, etc. Invention can be as formal as brainstorm activities like mind mapping and as informal as thinking about your writing task over breakfast.

Research: Finding new information.

Even if you’re not writing a research paper, you still generally have to figure out new things to complete a writing task. This can include the traditional reading of books, articles, and websites to find information to cite in a paper, but it can also include just reading up on a topic to learn more about it, interviewing an expert, looking at examples of the genre that you’re using to figure out what its characteristics are, taking careful notes on a text that you’re analyzing, or anything else that helps you to learn something important for your writing.

Drafting: Creating the text.

This is the part that we’re all familiar with: putting words down on paper, writing introductions and conclusions, and creating cohesive paragraphs and clear sentences. But, beyond the words themselves, drafting can also include shaping the medium for your writing, such as creating an e-portfolio where your writing will be displayed. Writing includes making design choices, such as formatting, font and color use, including and positioning images, and citing sources appropriately.

Revision: Literally, seeing the text again.

I’m talking about the big ideas here: looking over what you’ve created to see if you’ve accomplished your purpose, that you’ve effectively considered your audience, that your text is cohesive and coherent, and that it does the things that other texts in that genre do.

Editing: Looking at the surface level of the text.

Editing sometimes gets lumped in with revision (or replaces it entirely). I think it’s helpful to consider them as two separate ways of thinking about a text. Editing involves thinking about the clarity of word choice and sentence structure, noticing spelling and grammatical errors, making sure that source citations meet the requirements of your citation style, and other such issues. Even if editing isn’t big-concept like revision is, it’s still a very important way of thinking about a writing task.

Now, you may be thinking, “Okay, that’s great and all, but it still doesn’t tell me what recursion has to do with writing.” Well, notice how I called these five ways of thinking rather than “steps” or “stages” of the writing process? That’s because of recursion.

In your previous writing experiences, you’ve probably thought about your writing in all of the ways listed above, even if you used different terms or organized the ideas differently. However, Nancy Sommers, a researcher in rhetoric and writing studies, has found [1] that student writers tend to think about the writing process in a simple, linear way that mimics speech:

This process starts with thinking about the writing task and then moves through each part in order until, after editing, you’re finished. Even if you don’t do this every time, I’m betting that this linear process is probably familiar to you, especially if you just graduated high school.

On the other hand, Sommers also researched how experienced writers approach a writing task. She found that their writing process is different from that of student writers:

Unlike student writers, professional writers, like Steven Pinker, don’t view each part of the writing process as a step to be visited just once in a particular order. Yes, they generally begin with invention and end with editing, but they view each part of the process as a valuable way of thinking that can be revisited again and again until they are confident that the product effectively meets their goals.

For example, a colleague and I wrote a chapter for a book on working conditions at colleges, a topic we’re interested in.

- When we started, we had to come up with an idea for the text by talking through our experiences and deciding on a purpose for the text. [Invention]

- Although we both knew something about the topic already, we read articles and talked to experts to learn more about it. [Research]

- From that research, we decided that our original idea didn’t quite fit with the research that was out there already, so we made some changes to the big idea. [Invention]

- After that, we sat down and, over several sessions on different days, created a draft of our text. [Drafting]

- When we read through the text, we discovered that the order of the information didn’t make as much sense as we had first thought, so we moved around some paragraphs, making changes to those paragraphs to help the flow of the new order. [Revision]

- After that, we sent the rough draft to the editors of the book for feedback. When we got the chapter back, the editors commented that our topic didn’t quite fit the theme of the book, so, using that feedback, we changed the focus of the ideas. [Invention]

- Then we changed the text to reflect those new ideas. [Revision]

- We also got feedback from peer reviewers who pointed out that one part of the text was a little confusing, so we had to learn more about the ideas in that section. [Research]

- We changed the text to reflect that new understanding. [Revision and Editing]

- After the editors were satisfied with those revisions, we proofread the article and sent it off for final approval. [Editing]

In this process, we produced three distinct drafts, but each of those drafts represents several different ways that we made changes, small and large, to the text to better craft it for our audience, purpose, and context.

One goal of required college writing courses is to help you move from the mindset of the student writer to that of the experienced writer. Revisiting the big ideas of a writing task can be tough. Cutting several paragraphs because you find that they don’t meet the purpose of the writing task, throwing out research sources and having to search for more, completely reorganizing a text, or even reconsidering the genre can be a lot of work. But if you’re willing to put aside the linear steps and view invention, research, drafting, revision, and editing as ways of thinking that can be revisited over and over again until you accomplish your goal, you will become a more successful writer.

Although your future professors, bosses, co-workers, clients, and patients may only see the final product, mastering a complex, recursive writing process will help you to create effective texts for any situation you encounter.

- “Revision Strategies of Student Writers and Experienced Adult Writers” in College Composition and Communication 31.4, 378–88 ↵

Open English @ SLCC Copyright © 2016 by Chris Blankenship is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

An Overview of the Writing Process

Defining the writing process.

People often think of writing in terms of its end product—the email, the report, the memo, essay, or research paper, all of which result from the time and effort spent in the act of writing. In this course, however, you will be introduced to writing as the recursive process of planning, drafting, and revising.

Writing is Recursive

You will focus as much on the process of writing as you will on its end product (the writing you normally submit for feedback or a grade). Recursive means circling back; and, more often than not, the writing process will have you running in circles. You might be in the middle of your draft when you realize you need to do more brainstorming, so you return to the planning stage. Even when you have finished a draft, you may find changes you want to make to an introduction. In truth, every writer must develop his or her own process for getting the writing done, but there are some basic strategies and techniques you can adapt to make your work a little easier, more fulfilling and effective.

Developing Your Writing Process

The final product of a piece of writing is undeniably important, but the emphasis of this course is on developing a writing process that works for you. Some of you may already know what strategies and techniques assist you in your writing. You may already be familiar with prewriting techniques, such as freewriting, clustering, and listing. You may already have a regular writing practice. But the rest of you may need to discover what works through trial and error. Developing individual strategies and techniques that promote painless and compelling writing can take some time. So, be patient.

A Writer’s Process: Ali Hale

Read and examine The Writing Process by Ali Hale. Think of this document as a framework for defining the process in distinct stages: Prewriting, Writing, Revising, Editing, and Publishing. You may already be familiar with these terms. You may recall from past experiences that some resources refer to prewriting as planning and some texts refer to writing as drafting.

What is important to grasp early on is that the act of writing is more than sitting down and writing something. Please avoid the “one and done” attitude, something instructors see all too often in undergraduate writing courses. Use Hale’s essay as your starting point for defining your own process.

A Writer’s Process: Anne Lamott

In the video below, Anne Lamott, a writer of both non-fiction and fiction works, as well as the instructional novel on writing Bird by Bird: Instructions on Writing , discusses her own journey as a writer, including the obstacles she has to overcome every time she sits down to begin her creative process. She will refer to terms such as “the down draft,” “the up draft,” and “the dental draft.”

As you watch, think about how her terms, “down draft,” “up draft,” “dental draft,” work with those presented by Hale’s The Writing Process . What does Lamott mean by these terms? Can you identify with her process or with the one Hale describes? How are they related?

Also, when viewing the interview, pay careful attention to the following timeframe: 11:23 to 27:27 minutes and make a list of tips and strategies you find particularly helpful. Think about how your own writing process fits with what Hale and Lamott have to say. Is yours similar? Different? Is there any new information you have learned that you did not know before exposure to these works?

- Provided by : Lumen Learning. Located at : http://lumenlearning.com/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Authored by : Daryl Smith O' Hare and Susan C. Hines. Provided by : Chadron State College. Project : Kaleidoscope Open Course Initiative. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image: Computer and notebook. Located at : https://unsplash.com/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- A Conversation with Anne Lamott 2007. Provided by : University of California Television (UCTV). Located at : http://youtu.be/PhP5GmybvPM . License : All Rights Reserved . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

The Writing Post

Writing craft: writing as a recursive process.

I used to think that the writing process was as simple as sitting down, typing out a short story or essay on my laptop, giving it a quick review, and then sending it off to a magazine. In my imagination, I pictured editors responding with messages like, “You’re a genius! Here’s $3 billion dollars! You’ve revolutionized the world of writing!” In reality, all I managed to do was irritate a slew of editors at literary magazines (and algorithms that detected the flaws in my writing, which somehow felt even worse).

One of my early mistakes was failing to grasp the type of writing process that was truly needed or understanding that writing is a recursive endeavor. Yes, “recursive” might sound like a ten-dollar word, but it carries significant weight when you’re striving to establish an effective approach to writing. It’s about comprehending the steps a writer must take to be both productive and proficient.

The Process of Repetition

Writing as a recursive process encompasses the writing process itself (prewriting, drafting, revising, and editing). It allows you to revisit previous steps and jump around during a writing project because, as most approaches to academic writing will tell you, these processes flow into one another, creating fluidity between stages. For instance, you may need to return to your drafting stage to enhance your introduction with more refined language, even though you’re in the revising stage.

When we discuss writing as a recursive process, we’re talking about the repetition of the writing process, which can sometimes trap us in the space between the editing and revising stages, endlessly moving sentences around, correcting grammatical issues, and adding new ideas over and over. Yet, this is precisely what we do as writers to create polished, well-crafted work.

Why Is This Important?

It’s one thing to say, “Writing is recursive!” and another to fully understand its implications. Recursive writing means that each step you take in your writing process feeds into other steps. For example, after drafting an essay, you’ll verify facts, and if you find errors, you’ll return to the draft to correct them. In other words, we repeat processes to refine our message.

We must remember that we will always jump between stages. Completing the draft doesn’t mean you’re done drafting, and finishing revising doesn’t guarantee every paragraph is in its ideal place. In essence, writing is rewriting. It’s perfectly acceptable to revisit old steps in the process, from prewriting to drafting to revision, and even to begin again when you feel it’s necessary.

As Nancy Hutchison, associate professor of English at Howard Community College, wisely advises, “Good academic writing takes time. It’s a marathon, not a sprint, and there are many steps to writing well.” This advice holds true for various writing genres, whether it’s academic, fiction, content writing, or any other form. It reminds us that we’re not in a race to finish quickly. We’ve all submitted unfinished writing due to neglecting the revision process, and a key lesson is to remember your writing steps, take breaks, and know that it’s perfectly fine to revisit your writing process.

Works Cited

“Writing as a Process: Writing is Recursive.” Stetson University Writing Program. Web. URL: https://www.stetson.edu/other/writing-center/media/G_Part_3.pdf . Accessed: June 14, 2021.

Hutchison, Nancy. “Recursive Writing Process.” ENGLISH 087 Academic Advanced Writing, Howard Community College, 24 Jan. 2020, pressbooks.howardcc.edu/engl087/chapter/writing-process-recursion/.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Mastodon (Opens in new window)

[…] fledgling writers an opportunity to think about their own craft through reflection (and through the recursive process). Essentially, rethinking your writing (and genres) can help you write something more interesting […]

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Begin typing your search above and press return to search. Press Esc to cancel.

Discover more from The Writing Post

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

2.5: The Main Stages of the Writing Process

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 7363

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

The word “process” itself implies doing things in stages and over time. Applied to writing, this means that as you proceed from the beginning of a writing project through its middle and towards the end, you go through certain definable stages, each of which needs to be completed in order for the whole project to succeed.

Composing is very complex intellectual work consisting of many complex mental activities and processes. As we will see in the next section of this chapter, it is often difficult to say when and where one stage of the writing process ends and the next one begins. However, it is generally agreed that the writing process has at least three discreet stages: invention, revision, and editing. In addition to inventing, revising, and editing, writers who follow the process approach also seek and receive feedback to their drafts from others. It is also important to understand that the writing process is recursive and non-linear. What this means is that a writer may finish initial invention, produce a draft, and then go back to generating more ideas, before revising the text he or she created.

Figure 2.1 - The Writing Process. Source: www.mywritingportfolio.ne t

Invention is what writers do before they produce a first complete draft of their piece. As its name suggests, invention helps writers to come up with material for writing. The process theory states that no writer should be expected to simply sit down and write a complete piece without some kind of preparatory work. The purpose of invention is to explore various directions in which the piece may go and to try different ways to develop material for writing. Note the words “explore” and “try” in the previous sentence. They suggest that not all the material generated during invention final, or even the first draft. To a writer used to product-based composing, this may seem like a waste of time and energy. Why generate more ideas during invention than you can into the paper, they reason?

Remember that your goal during invention is to explore various possibilities for your project. At this point, just about the most dangerous and counter-productive thing you can do as a writer is to “lock in” on one idea, thesis, type of evidence, or detail, and ignore all other possibilities. Such a limited approach is particularly dangerous when applied to research writing. A discussion of that follows in the section of this chapter which is dedicated to the application the process model to research writing. Below, I offer several invention, revision, and editing strategies and activities.

Invention Techniques

These invention strategies invite spontaneity and creativity. Feel free to adjust and modify them as you see fit. They will probably work best for you if you apply them to a specific writing project rather than try them out “for practice’s sake.” As you try them, don’t worry about the shape or even content of your final draft. At this stage, you simply don’t know what that draft is going to look like. You are creating its content as you invent. This is not a complete list of all possible invention strategies. Your teacher and classmates may be able to share other invention ideas with you.

Free-writing

As its name suggests, free writing encourages the writer to write freely and without worrying about the content or shape of the writing. When you free-write, your goal is to generate as much material on the page as possible, no matter what you say or how you say it.

Try to write for five, ten, or even fifteen minutes without checking, censoring, or editing yourself in any way. You should not put your pen or pencil down, or stop typing on the computer, no matter what. If you run out of things to say, repeat “I have nothing to say” or something similar until the next idea pops into your head. Let your mind go, go with the flow, and don’t worry about the end product. Your objective is to create as much text as possible. Don’t even worry about finishing your sentences or separating your paragraphs. You are not writing a draft of your paper. Instead, you are producing raw material for that draft. Later on, you just might find a gem of an idea in that raw material which you can develop into a complete draft. Also don’t worry if anyone will be able to read what your have written—most likely you will be the only reader of your text. If your teacher asks you to share your free writing with other students, you can explain what you have written to your group mates as you go along.

Brainstorming

When brainstorming, you list as quickly as possible all thoughts and ideas which are connected, however loosely, to the topic of your writing. As with free writing, you should not worry about the shape or structure of your writing. Your only concern should be to write as long a list of possibilities as you can. As you brainstorm, try not to focus your writing radar too narrowly, on a single aspect of your topic or a single question. The broader you cast your brainstorming net, the better because a large list of possibilities will give you a wealth of choices when time comes to compose your first draft. Your teacher may suggest how many items to have on your brainstorming list. I usually ask my students to come up with at least ten to twelve items in a five to ten minute long brainstorming session, more if possible.

Mind-Mapping

Mind-mapping, which is also known as webbing or clustering, invites you to create a visual representation of your writing topic or of the problem you are trying to solve through your writing and research. The usefulness of mind-mapping as an invention techniques has been recognized by professionals in many disciplines, with at least one software company designing a special computer program exclusively for creating elaborate mind maps.

Here is how mind-mapping works. Write your topic or questions in the middle of a blank page, or type it in the middle of a computer screen, and think about any other topics or subtopics related to this main topic or question. Then branch out of the center connecting the central idea of your mind map to the other ones. The result should like a spider’s web. The figure is a mind-map I made for the first draft of the chapter of this book dedicated to rhetoric.

This invention strategy also asks the writer to create a visual representation of his or topic and is particularly useful for personal writing projects and memoirs. In such projects, memories and recollections, however vague and uncertain, are often starting points for writing. Instead of writing about your memories, this invention strategy invites you to draw them. The advantage of this strategy is that it allows the writer not only to restore these memories in preparation for writing, but also to reflect upon them. As you know by now, one of the fundamental principles of the process approach to writing is that meaning is created as the writer develops the piece from draft to draft. Drawing elements of your future project may help you create such meaning. I am not particularly good at visual arts, so I will not subject you to looking at my drawings. Instead, I invite you to create your own.

Outlining can be a powerful invention tool because it allows writers to generate ideas and to organize them in a systematic manner. In a way, outlining is similar to mind mapping as it allows you to break down main ideas and points into smaller ones. The difference between mind maps and outlines is, of course, the fact that the former provides a visual representation of your topic while the latter gives you a more linear, textual one. If you like to organize your thoughts systematically as you compose, a good outline can be a useful resource when you begin drafting.

However, it is extremely important to observe two conditions when using outlining as your main invention strategy. The first is to treat your outline as a flexible plan for writing and nothing more. The key word is “flexible.” Your outline is not a rigid set of points which you absolutely must cover in your paper, and the structure of your outline, with all its points and sub-points, does not predetermine the structure of your paper. The second condition follows from the first. If, in the process of writing the paper, you realize that your current outline does not suit you anymore, change it or discard it. Do not follow it devotedly, trying to fit your writing into what your outline wants it to be.

So, again, the outline is you flexible plan for writing, not a canon that you have to follow at all cost. It is hard for writers to create a “perfect” or complete outline before writing because the meaning of a piece takes shape during composing, not before. It is difficult, if not impossible, to know what you are going to say in your writing unless and until you begin to say it. Outlining may help you in planning your first draft, but it should not determine it.

Keeping a journal or a writer’s notebook

Keeping a journal or a writer’s notebook is another powerful invention strategy. Keeping a writer’s journal can work regardless of the genre you are working in. Journals and writer’s notebooks are popular among writers of fiction and creative non-fiction. But they also have a huge potential for researching writers because keeping a journal allows you not only to record events and details, but also to reflect on them through writing. In the chapter of this book dedicated to researching in academic disciplines, I discuss one particular type of writing journal called the double-entry journal. If you decide to keep a journal or a writer’s notebook as an invention strategy, keep in mind the following principles:

- Write in your journal or notebook regularly.

- Keep everything you write—you never know when you may need or want to use it in your writing.

- Write about interesting events, observations, and thoughts.

- Reflect on what you have written. Reflection allows you to make that leap from simple observation to making sense of what you have observed.

- Frequently re-read your entries.

It is hard to overestimate the importance of reading as an invention strategy. As you can learn from the chapters on rhetoric and on reading, writing is a social process that never occurs in a vacuum. To get ideas for writing of your own, you need to be familiar with ideas of others. Reading is one of the best, if not the best way, to get such material. Reading is especially important for research writing. For a more in-depth discussion of the relationship between reading and writing and for specific activities designed to help you to use reading for writing, see Chapter 3 of this book dedicated to reading.

Examining your Current Knowledge

The best place to start looking for a research project topic is to examine your own interests, passions, and hobbies. What topics, events, people, or natural phenomena, or stories interest, concern you, or make you passionate? What have you always wanted to find out more about or explore in more depth?

Looking into the storehouse of your knowledge and life experiences will allow you to choose a topic for your research project in which you are genuinely interested and in which you will,therefore, be willing to invest plenty of time, effort, and enthusiasm. Simultaneously with being interesting and important to you, your research topic should, of course, interest your readers. As you have learned from the chapter on rhetoric, writers always write with a purpose and for a specific audience.

Therefore, whatever topic you choose and whatever argument you will build about it through research should provoke response in your readers. And while almost any topic can be treated in an original and interesting way, simply choosing the topic that interests you, the writer, is not, in itself, a guarantee of success of your research project.

Here is some advice on how to select a promising topic for your next research project. As you think about possible topics for your paper, remember that writing is a conversation between you and your readers. Whatever subject you choose to explore and write about has to be something that is interesting and important to them as well as to you. Remember kairos, or the ability to "be in the right place at the right time, which we discussed in Chapter 1.

When selecting topics for research, consider the following factors:

- Your existing knowledge about the topic

- What else you need or want to find out about the topic

- What questions about or aspects of the topic are important not only for you but for others around you.

- Resources (libraries, internet access, primary research sources, and so on) available to you in order to conduct a high quality investigation of your topic.

Read about and “around” various topics that interest you. As I argue later on in this chapter, reading is a powerful invention tool capable of teasing out subjects, questions, and ideas which would not have come to mind otherwise. Reading also allows you to find out what questions, problems, and ideas are circulating among your potential readers, thus enabling you to better and quicker enter the conversation with those readers through research and writing.

Explore " Writing Activity 2B: Generating Topics " in the "Writing Activities" section of this chapter.

If you have an idea of the topic or issue you want to study, try asking the following questions

- Why do I care about this topic?

- What do I already know or believe about this topic?

- How did I receive my knowledge or beliefs (personal experiences, stories of others, reading, and so on)?

- What do I want to find out about this topic?

- Who else cares about or is affected by this topic? In what ways and why?

- What do I know about the kinds of things that my potential readers might want to learn about it?

- Where do my interests about the topic intersect with my readers’ potential interests, and where they do not?

Which topic or topics has the most potential to interest not only you, the writer, but also your readers?

Designing Research Questions

Assuming that you were able to select the topic for your next research project, it is not time to design some research questions. Forming specific and relevant research questions will allow you to achieve three important goals:

- Direct your research from the very beginning of the project

- Keep your research focused and on track

- Help you find relevant and interesting sources

Writing Process: Writing

Getting to know your writing process.

Developing an effective writing process has a huge impact on the quality of your writing. Sometimes we think that improving writing means finding the perfect article or having some divine inspiration, but it’s amazing how much our writing improves simply by adjusting our writing process to work better for us.

Please scroll to continue reading in order, or click a heading below to jump straight to that section.

Process is individual and recursive

A good writing process will be tailored to one’s individual learning style. Do you work better in the morning or at night? Do you work better alone or with friends? Do you write some things on a computer and some on paper? Do you give yourself enough time for your ideas to properly develop?

If you approach your individual process with curiosity and flexibility, insights await. For example, maybe you enjoy lots of background noise when producing your first rough draft, but silence is better for editing. If you feel your usual process isn't working, try to experiment with changing variables: reflect on what works and what doesn't.

The writing process is also recursive. This means that the steps of the process don't unfold in a clean, precise order. Instead, writers move between steps, leaping forward, circling back and repeating them as needed. In fact, you might find it more helpful to think of the writing process as a buffet of writing activities rather than a rigid sequence.

When you chart in order the activities any given writer engages in to produce an essay, the resulting visual resembles more of a spiderweb than a tidy procedural diagram.

Understanding

A logical starting place for writing any assignment is understanding. Before you begin to do anything, after all, you need to know what it is you're being asked to do!

- First, mark the deadline in your calendar.

- Next, closely read the description of your assessment. Does it ask you to describe , discuss , explain , argue or some other verb?

- Look closely at the structure you are meant to model, and make note of any requirements related to evidence and content (i.e., authors you need to reference, theories you need to incorporate, and so on).

If you need more information to plan your work, ask your instructors or tutors early. As you begin to understand the task, think about adding your own deadlines for specific tasks in your calendar as well: maybe have a first draft ready one week early, or an outline ready by the end of the week.

Tip: Use the 'Verbs' tab of our Understanding the Assignment guide for help analysing assignment aims.

Once you’ve got a good understanding of the task, it is time for ideas. The invention stage is not the time to say no. It is the time to generate ideas without judgment. The benefit of getting a bunch of ideas on the page is that you can avoid pursuing the first idea that comes to your head. Often, the better ideas are waiting behind our first thoughts.

Some people prefer to make lists. Some prefer to structure lists into outlines . Others like to map out connections between ideas visually with colourful mind maps, which can be drawn longhand or built in a mind mapping app or website. Find a way that works for you.

Research question(s)

Whether or not we write it in our essays, each piece of academic writing is answering a question. If we can tailor that question to our specific task, it helps us maintain our focus as we research and write. Before beginning the research portion, turn your ideas into questions. That way, you can seek specific answers.

A good research question won’t have a simple, single answer. A good research question will offer many opportunities to discuss different perspectives, but still stay focused on a specific purpose for the text.

Researching

- Good research is focused . Finding good resources demands a knowledge of online databases and library materials. Develop your research skills , and don't hesitate to seek out a librarian to help navigate the wealth of resources the library provides.

- Good research is organised . Don’t just amass a pile of .pdfs. As you assess their quality for your purposes, make notes, name the files, and keep track of them in subfolders. As you read through them, keep notes in a searchable format, perhaps via thematic notetaking or the annotated bibliography method. Save your future self from wasted time and frustration by focusing your research and keeping track of your thoughts on what you find.

Planning, Refining, Reflecting

This is where things are about to get more complicated. Take a step back and think about where you are headed with your research and if it really fits the task. Are you still on topic? Have you found new, exciting material that raises better research questions? Pause to plan and revisit your ideas. Transfer your research into an outline or some other sort of plan. This is why it helps to give yourself time.

The rough draft can be a mess: explore our guide on rough drafting to learn more. This is the first translation of planning into prose, so don’t feel any pressure to get it perfect on the first try. Don’t overthink. It's called a rough draft for a reason!

If writing anxiety and/or perfectionism make it difficult for you to get words down without picking over and rethinking them, consider trying a website that prevents you from deleting your text. These sites allow you to type as much as you want, but you can't erase any of the words you have written: a very helpful tool to quiet your inner critic, and get on with it!

You can also try a technique called freewriting . The simplest version is to set a timer for five or ten minutes, and then write nonstop until the timer dings. No pausing, no stopping to ponder your next point: your pen on the paper (or your fingers on the keyboard) should be moving nonstop. You can stumble into some great ideas this way! The key is to reflect on and sort through your freewriting after the timer dings, identifying promising ideas or phrases (and ignoring the rest).

Editing or revising

The editing or revision process is when all the elements start working together as you write and refine, then re-write and re-refine. You should ultimately be clarifying and supporting your main points in a recursive process. Go back to the writing prompt, revisit your notes, share your draft with someone to read, ask friends about your argument, go for a walk, build a reverse outline , question the validity of your claims, re-organise your points, do another search for articles. Do whatever it takes to turn the cloud of thoughts and ideas into a coherent piece of work.

Proofreading

Whereas the editing or revision stage is concerned with the 'big picture', such as how evidence is used to support your thesis statement, proofreading is the time to polish the fine details of your work. Ensure the 'small picture' concerns are addressed before you submit. Our 'Refine Your Writing: Better Proofreading' learning sequence will equip you with a range of strategies to improve your skills; here are some highlights:

- Give yourself the time and space you need in order to read your finished paper with fresh eyes .

- Try reading your work aloud or having a friend read it to you. The 'read aloud' option in your word processor also works. This technique helps you catch unneeded repetition, awkward phrasing and punctuation issues.

- Be sure your points are clearly stated and not hiding behind overly academic style.

- Use your subject area's style guide and online tools like Cite Them Right to check your reference formatting and consistency.

Only you will know when your paper is completed and ready for submission. Be sure to do the following:

- Meet your deadline.

- Name and format the file according to submission guidelines.

- After uploading, be sure the appropriate confirmation screen is shown.

- Save a copy of your final essay for future reference (your university OneDrive account is a good storage option).

This is only one version of a writing process. Each writer should work towards a healthy, effective way to use each of these steps or activities to accomplish a successful piece of writing. Once you have this knowledge, the larger question becomes one of planning, continuing curiosity and reflection. Embrace opportunities to expand or redefine your process as you encounter new academic challenges.

- Last Updated: Apr 30, 2024 2:09 PM

- URL: https://library.soton.ac.uk/writing_process

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

41 Writing Is Recursive

Chris Blankenship

In a recent interview , Steven Pinker, Harvard professor and author of The Sense of Style: The Thinking Person’s Guide to Writing in the 21st Century , was asked how he approaches the revision of his own writing. His answer? “Recursively and frequently.”

What does Pinker mean when he says “recursively,” though?

You’re probably familiar with the root of the word: “cursive.” It’s the style of writing that you may have been taught in elementary school or that you’ve seen in historical documents like the Declaration of Independence or Constitution.

“Cursive” comes from the Latin word currere , meaning “to run.” Combine this meaning with the English prefix “re-” (to do again), and you have some clues for the meaning of “recursive.”

In modern English, recursion is used to describe a process that loops or “runs again” until a task is complete. It’s a term often used in computer science to indicate a program or piece of code that continues to run until certain conditions are met, such as a variable determined by the user of the program. The program would continue counting upwards—running—until it came to that variable.

So, what does recursion have to do with writing?

You’ve probably heard writing teachers talk about the idea of the “ writing process” before. In a nutshell, although writing always ends with the creation of a “product,” the process that leads to that product determines how effective the writing will be. It’s why a carefully thought-out essay tends to be better than one that’s written the night before the due date. It’s also why college writing teachers often emphasize the idea of process in their classes in addition to evaluating final products.

There are many ways to think about the writing process, but here’s one that my students have said makes sense to them. It involves five separate ways of thinking about a writing task:

Invention: Coming up with ideas.

This can include thinking about what you want to accomplish with your writing, who will be reading your writing and how to adapt to them, the genre you are writing in, your position on a topic, what you know about a topic already, etc. Invention can be as formal as brainstorm activities like mind mapping and as informal as thinking about your writing task over breakfast.

Research: Finding new information.

Even if you’re not writing a research paper, you still generally have to figure out new things to complete a writing task. This can include the traditional reading of books, articles, and websites to find information to cite in a paper, but it can also include just reading up on a topic to learn more about it, interviewing an expert, looking at examples of the genre that you’re using to figure out what its characteristics are, taking careful notes on a text that you’re analyzing, or anything else that helps you to learn something important for your writing.

Drafting: Creating the text.

This is the part that we’re all familiar with: putting words down on paper, writing introductions and conclusions, and creating cohesive paragraphs and clear sentences. But, beyond the words themselves, drafting can also include shaping the medium for your writing, such as creating an e-portfolio where your writing will be displayed. Writing includes making design choices, such as formatting, font and color use, including and positioning images, and citing sources appropriately.

Revision: Literally, seeing the text again.

I’m talking about the big ideas here: looking over what you’ve created to see if you’ve accomplished your purpose, that you’ve effectively considered your audience, that your text is cohesive and coherent, and that it does the things that other texts in that genre do.

Editing: Looking at the surface level of the text.

Editing sometimes gets lumped in with revision (or replaces it entirely). I think it’s helpful to consider them as two separate ways of thinking about a text. Editing involves thinking about the clarity of word choice and sentence structure, noticing spelling and grammatical errors, making sure that source citations meet the requirements of your citation style, and other such issues. Even if editing isn’t big-concept like revision is, it’s still a very important way of thinking about a writing task.

Now, you may be thinking, “Okay, that’s great and all, but it still doesn’t tell me what recursion has to do with writing.” Well, notice how I called these five ways of thinking rather than “steps” or “stages” of the writing process? That’s because of recursion.