The “no first-person” myth

- First-Person Pronouns

- Research and Publication

In this series, we look at common APA Style misconceptions and debunk these myths one by one.

Many writers believe the “no first-person” myth, which is that writers cannot use first-person pronouns such as “I” or “we” in an APA Style paper. This myth implies that writers must instead refer to themselves in the third person (e.g., as “the author” or “the authors”). However, APA Style has no such rule against using first-person pronouns and actually encourages their use to avoid ambiguity in attribution!

When expressing your own views or the views of yourself and fellow authors, use the pronouns “I” or “we” and the like . Similarly, when writing your paper, use first-person pronouns when describing work you did by yourself or work you and your fellow authors did together when conducting your research. For example, use “we interviewed participants” rather than “the authors interviewed participants.” When writing an APA Style paper by yourself, use the first-person pronoun “I” to refer to yourself. And use the pronoun “we” when writing an APA Style paper with others. Here are some phrases you might use in your paper:

“I think…” “I believe…” “I interviewed the participants…” “I analyzed the data…” “My analysis of the data revealed…” “We concluded…” “Our results showed…”

This guidance can be found in Section 4.16 of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, Seventh Edition and in Section 2.16 of the Concise Guide to APA Style, Seventh Edition . It represents a continuation of a long-standing APA Style guideline that began with the second edition of the manual, in 1974.

Keep in mind that you should avoid using the editorial “we” to refer to people in general so that it is clear to readers to whom you are referring. Instead, use more specific nouns such as “people” or “researchers.”

As always, defer to your instructors’ guidelines when writing student papers. For example, your instructor may ask students to avoid using first-person language. If so, follow that guideline for work in your class.

Now that we’ve debunked another myth, go forth APA Style writers, using the first-person when appropriate!

What myth should we debunk next? Leave a comment below.

Related and recent

Comments are disabled due to your privacy settings. To re-enable, please adjust your cookie preferences.

APA Style Monthly

Subscribe to the APA Style Monthly newsletter to get tips, updates, and resources delivered directly to your inbox.

Welcome! Thank you for subscribing.

APA Style Guidelines

Browse APA Style writing guidelines by category

- Abbreviations

- Bias-Free Language

- Capitalization

- In-Text Citations

- Italics and Quotation Marks

- Paper Format

- Punctuation

- Spelling and Hyphenation

- Tables and Figures

Full index of topics

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Science Writing

How to Write a Hypothesis

Last Updated: May 2, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Bess Ruff, MA . Bess Ruff is a Geography PhD student at Florida State University. She received her MA in Environmental Science and Management from the University of California, Santa Barbara in 2016. She has conducted survey work for marine spatial planning projects in the Caribbean and provided research support as a graduate fellow for the Sustainable Fisheries Group. There are 9 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 1,033,636 times.

A hypothesis is a description of a pattern in nature or an explanation about some real-world phenomenon that can be tested through observation and experimentation. The most common way a hypothesis is used in scientific research is as a tentative, testable, and falsifiable statement that explains some observed phenomenon in nature. [1] X Research source Many academic fields, from the physical sciences to the life sciences to the social sciences, use hypothesis testing as a means of testing ideas to learn about the world and advance scientific knowledge. Whether you are a beginning scholar or a beginning student taking a class in a science subject, understanding what hypotheses are and being able to generate hypotheses and predictions yourself is very important. These instructions will help get you started.

Preparing to Write a Hypothesis

- If you are writing a hypothesis for a school assignment, this step may be taken care of for you.

- Focus on academic and scholarly writing. You need to be certain that your information is unbiased, accurate, and comprehensive. Scholarly search databases such as Google Scholar and Web of Science can help you find relevant articles from reputable sources.

- You can find information in textbooks, at a library, and online. If you are in school, you can also ask for help from teachers, librarians, and your peers.

- For example, if you are interested in the effects of caffeine on the human body, but notice that nobody seems to have explored whether caffeine affects males differently than it does females, this could be something to formulate a hypothesis about. Or, if you are interested in organic farming, you might notice that no one has tested whether organic fertilizer results in different growth rates for plants than non-organic fertilizer.

- You can sometimes find holes in the existing literature by looking for statements like “it is unknown” in scientific papers or places where information is clearly missing. You might also find a claim in the literature that seems far-fetched, unlikely, or too good to be true, like that caffeine improves math skills. If the claim is testable, you could provide a great service to scientific knowledge by doing your own investigation. If you confirm the claim, the claim becomes even more credible. If you do not find support for the claim, you are helping with the necessary self-correcting aspect of science.

- Examining these types of questions provides an excellent way for you to set yourself apart by filling in important gaps in a field of study.

- Following the examples above, you might ask: "How does caffeine affect females as compared to males?" or "How does organic fertilizer affect plant growth compared to non-organic fertilizer?" The rest of your research will be aimed at answering these questions.

- Following the examples above, if you discover in the literature that there is a pattern that some other types of stimulants seem to affect females more than males, this could be a clue that the same pattern might be true for caffeine. Similarly, if you observe the pattern that organic fertilizer seems to be associated with smaller plants overall, you might explain this pattern with the hypothesis that plants exposed to organic fertilizer grow more slowly than plants exposed to non-organic fertilizer.

Formulating Your Hypothesis

- You can think of the independent variable as the one that is causing some kind of difference or effect to occur. In the examples, the independent variable would be biological sex, i.e. whether a person is male or female, and fertilizer type, i.e. whether the fertilizer is organic or non-organically-based.

- The dependent variable is what is affected by (i.e. "depends" on) the independent variable. In the examples above, the dependent variable would be the measured impact of caffeine or fertilizer.

- Your hypothesis should only suggest one relationship. Most importantly, it should only have one independent variable. If you have more than one, you won't be able to determine which one is actually the source of any effects you might observe.

- Don't worry too much at this point about being precise or detailed.

- In the examples above, one hypothesis would make a statement about whether a person's biological sex might impact the way the person is affected by caffeine; for example, at this point, your hypothesis might simply be: "a person's biological sex is related to how caffeine affects his or her heart rate." The other hypothesis would make a general statement about plant growth and fertilizer; for example your simple explanatory hypothesis might be "plants given different types of fertilizer are different sizes because they grow at different rates."

- Using our example, our non-directional hypotheses would be "there is a relationship between a person's biological sex and how much caffeine increases the person's heart rate," and "there is a relationship between fertilizer type and the speed at which plants grow."

- Directional predictions using the same example hypotheses above would be : "Females will experience a greater increase in heart rate after consuming caffeine than will males," and "plants fertilized with non-organic fertilizer will grow faster than those fertilized with organic fertilizer." Indeed, these predictions and the hypotheses that allow for them are very different kinds of statements. More on this distinction below.

- If the literature provides any basis for making a directional prediction, it is better to do so, because it provides more information. Especially in the physical sciences, non-directional predictions are often seen as inadequate.

- Where necessary, specify the population (i.e. the people or things) about which you hope to uncover new knowledge. For example, if you were only interested the effects of caffeine on elderly people, your prediction might read: "Females over the age of 65 will experience a greater increase in heart rate than will males of the same age." If you were interested only in how fertilizer affects tomato plants, your prediction might read: "Tomato plants treated with non-organic fertilizer will grow faster in the first three months than will tomato plants treated with organic fertilizer."

- For example, you would not want to make the hypothesis: "red is the prettiest color." This statement is an opinion and it cannot be tested with an experiment. However, proposing the generalizing hypothesis that red is the most popular color is testable with a simple random survey. If you do indeed confirm that red is the most popular color, your next step may be to ask: Why is red the most popular color? The answer you propose is your explanatory hypothesis .

- An easy way to get to the hypothesis for this method and prediction is to ask yourself why you think heart rates will increase if children are given caffeine. Your explanatory hypothesis in this case may be that caffeine is a stimulant. At this point, some scientists write a research hypothesis , a statement that includes the hypothesis, the experiment, and the prediction all in one statement.

- For example, If caffeine is a stimulant, and some children are given a drink with caffeine while others are given a drink without caffeine, then the heart rates of those children given a caffeinated drink will increase more than the heart rate of children given a non-caffeinated drink.

- Using the above example, if you were to test the effects of caffeine on the heart rates of children, evidence that your hypothesis is not true, sometimes called the null hypothesis , could occur if the heart rates of both the children given the caffeinated drink and the children given the non-caffeinated drink (called the placebo control) did not change, or lowered or raised with the same magnitude, if there was no difference between the two groups of children.

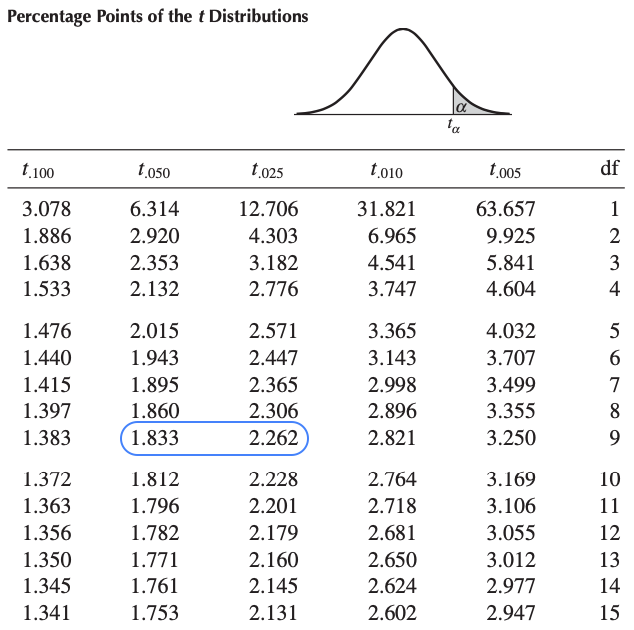

- It is important to note here that the null hypothesis actually becomes much more useful when researchers test the significance of their results with statistics. When statistics are used on the results of an experiment, a researcher is testing the idea of the null statistical hypothesis. For example, that there is no relationship between two variables or that there is no difference between two groups. [8] X Research source

Hypothesis Examples

Community Q&A

- Remember that science is not necessarily a linear process and can be approached in various ways. [10] X Research source Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- When examining the literature, look for research that is similar to what you want to do, and try to build on the findings of other researchers. But also look for claims that you think are suspicious, and test them yourself. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Be specific in your hypotheses, but not so specific that your hypothesis can't be applied to anything outside your specific experiment. You definitely want to be clear about the population about which you are interested in drawing conclusions, but nobody (except your roommates) will be interested in reading a paper with the prediction: "my three roommates will each be able to do a different amount of pushups." Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://undsci.berkeley.edu/for-educators/prepare-and-plan/correcting-misconceptions/#a4

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/common_writing_assignments/research_papers/choosing_a_topic.html

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/subject_specific_writing/writing_in_the_social_sciences/writing_in_psychology_experimental_report_writing/experimental_reports_1.html

- ↑ https://www.grammarly.com/blog/how-to-write-a-hypothesis/

- ↑ https://grammar.yourdictionary.com/for-students-and-parents/how-create-hypothesis.html

- ↑ https://flexbooks.ck12.org/cbook/ck-12-middle-school-physical-science-flexbook-2.0/section/1.19/primary/lesson/hypothesis-ms-ps/

- ↑ https://iastate.pressbooks.pub/preparingtopublish/chapter/goal-1-contextualize-the-studys-methods/

- ↑ http://mathworld.wolfram.com/NullHypothesis.html

- ↑ http://undsci.berkeley.edu/article/scienceflowchart

About This Article

Before writing a hypothesis, think of what questions are still unanswered about a specific subject and make an educated guess about what the answer could be. Then, determine the variables in your question and write a simple statement about how they might be related. Try to focus on specific predictions and variables, such as age or segment of the population, to make your hypothesis easier to test. For tips on how to test your hypothesis, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Onyia Maxwell

Sep 13, 2016

Did this article help you?

Nov 26, 2017

ABEL SHEWADEG

Jun 12, 2018

Connor Gilligan

Jan 2, 2017

Dec 30, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

Learn How To Write A Hypothesis For Your Next Research Project!

Undoubtedly, research plays a crucial role in substantiating or refuting our assumptions. These assumptions act as potential answers to our questions. Such assumptions, also known as hypotheses, are considered key aspects of research. In this blog, we delve into the significance of hypotheses. And provide insights on how to write them effectively. So, let’s dive in and explore the art of writing hypotheses together.

Table of Contents

What is a Hypothesis?

A hypothesis is a crucial starting point in scientific research. It is an educated guess about the relationship between two or more variables. In other words, a hypothesis acts as a foundation for a researcher to build their study.

Here are some examples of well-crafted hypotheses:

- Increased exposure to natural sunlight improves sleep quality in adults.

A positive relationship between natural sunlight exposure and sleep quality in adult individuals.

- Playing puzzle games on a regular basis enhances problem-solving abilities in children.

Engaging in frequent puzzle gameplay leads to improved problem-solving skills in children.

- Students and improved learning hecks.

S tudents using online paper writing service platforms (as a learning tool for receiving personalized feedback and guidance) will demonstrate improved writing skills. (compared to those who do not utilize such platforms).

- The use of APA format in research papers.

Using the APA format helps students stay organized when writing research papers. Organized students can focus better on their topics and, as a result, produce better quality work.

The Building Blocks of a Hypothesis

To better understand the concept of a hypothesis, let’s break it down into its basic components:

- Variables . A hypothesis involves at least two variables. An independent variable and a dependent variable. The independent variable is the one being changed or manipulated, while the dependent variable is the one being measured or observed.

- Relationship : A hypothesis proposes a relationship or connection between the variables. This could be a cause-and-effect relationship or a correlation between them.

- Testability : A hypothesis should be testable and falsifiable, meaning it can be proven right or wrong through experimentation or observation.

Types of Hypotheses

When learning how to write a hypothesis, it’s essential to understand its main types. These include; alternative hypotheses and null hypotheses. In the following section, we explore both types of hypotheses with examples.

Alternative Hypothesis (H1)

This kind of hypothesis suggests a relationship or effect between the variables. It is the main focus of the study. The researcher wants to either prove or disprove it. Many research divides this hypothesis into two subsections:

- Directional

This type of H1 predicts a specific outcome. Many researchers use this hypothesis to explore the relationship between variables rather than the groups.

- Non-directional

You can take a guess from the name. This type of H1 does not provide a specific prediction for the research outcome.

Here are some examples for your better understanding of how to write a hypothesis.

- Consuming caffeine improves cognitive performance. (This hypothesis predicts that there is a positive relationship between caffeine consumption and cognitive performance.)

- Aerobic exercise leads to reduced blood pressure. (This hypothesis suggests that engaging in aerobic exercise results in lower blood pressure readings.)

- Exposure to nature reduces stress levels among employees. (Here, the hypothesis proposes that employees exposed to natural environments will experience decreased stress levels.)

- Listening to classical music while studying increases memory retention. (This hypothesis speculates that studying with classical music playing in the background boosts students’ ability to retain information.)

- Early literacy intervention improves reading skills in children. (This hypothesis claims that providing early literacy assistance to children results in enhanced reading abilities.)

- Time management in nursing students. ( Students who use a nursing research paper writing service have more time to focus on their studies and can achieve better grades in other subjects. )

Null Hypothesis (H0)

A null hypothesis assumes no relationship or effect between the variables. If the alternative hypothesis is proven to be false, the null hypothesis is considered to be true. Usually a null hypothesis shows no direct correlation between the defined variables.

Here are some of the examples

- The consumption of herbal tea has no effect on sleep quality. (This hypothesis assumes that herbal tea consumption does not impact the quality of sleep.)

- The number of hours spent playing video games is unrelated to academic performance. (Here, the null hypothesis suggests that no relationship exists between video gameplay duration and academic achievement.)

- Implementing flexible work schedules has no influence on employee job satisfaction. (This hypothesis contends that providing flexible schedules does not affect how satisfied employees are with their jobs.)

- Writing ability of a 7th grader is not affected by reading editorial example. ( There is no relationship between reading an editorial example and improving a 7th grader’s writing abilities.)

- The type of lighting in a room does not affect people’s mood. (In this null hypothesis, there is no connection between the kind of lighting in a room and the mood of those present.)

- The use of social media during break time does not impact productivity at work. (This hypothesis proposes that social media usage during breaks has no effect on work productivity.)

As you learn how to write a hypothesis, remember that aiming for clarity, testability, and relevance to your research question is vital. By mastering this skill, you’re well on your way to conducting impactful scientific research. Good luck!

Importance of a Hypothesis in Research

A well-structured hypothesis is a vital part of any research project for several reasons:

- It provides clear direction for the study by setting its focus and purpose.

- It outlines expectations of the research, making it easier to measure results.

- It helps identify any potential limitations in the study, allowing researchers to refine their approach.

In conclusion, a hypothesis plays a fundamental role in the research process. By understanding its concept and constructing a well-thought-out hypothesis, researchers lay the groundwork for a successful, scientifically sound investigation.

How to Write a Hypothesis?

Here are five steps that you can follow to write an effective hypothesis.

Step 1: Identify Your Research Question

The first step in learning how to compose a hypothesis is to clearly define your research question. This question is the central focus of your study and will help you determine the direction of your hypothesis.

Step 2: Determine the Variables

When exploring how to write a hypothesis, it’s crucial to identify the variables involved in your study. You’ll need at least two variables:

- Independent variable : The factor you manipulate or change in your experiment.

- Dependent variable : The outcome or result you observe or measure, which is influenced by the independent variable.

Step 3: Build the Hypothetical Relationship

In understanding how to compose a hypothesis, constructing the relationship between the variables is key. Based on your research question and variables, predict the expected outcome or connection. This prediction should be specific, testable, and, if possible, expressed in the “If…then” format.

Step 4: Write the Null Hypothesis

When mastering how to write a hypothesis, it’s important to create a null hypothesis as well. The null hypothesis assumes no relationship or effect between the variables, acting as a counterpoint to your primary hypothesis.

Step 5: Review Your Hypothesis

Finally, when learning how to compose a hypothesis, it’s essential to review your hypothesis for clarity, testability, and relevance to your research question. Make any necessary adjustments to ensure it provides a solid basis for your study.

In conclusion, understanding how to write a hypothesis is crucial for conducting successful scientific research. By focusing on your research question and carefully building relationships between variables, you will lay a strong foundation for advancing research and knowledge in your field.

Hypothesis vs. Prediction: What’s the Difference?

Understanding the differences between a hypothesis and a prediction is crucial in scientific research. Often, these terms are used interchangeably, but they have distinct meanings and functions. This segment aims to clarify these differences and explain how to compose a hypothesis correctly, helping you improve the quality of your research projects.

Hypothesis: The Foundation of Your Research

A hypothesis is an educated guess about the relationship between two or more variables. It provides the basis for your research question and is a starting point for an experiment or observational study.

The critical elements for a hypothesis include:

- Specificity: A clear and concise statement that describes the relationship between variables.

- Testability: The ability to test the hypothesis through experimentation or observation.

To learn how to write a hypothesis, it’s essential to identify your research question first and then predict the relationship between the variables.

Prediction: The Expected Outcome

A prediction is a statement about a specific outcome you expect to see in your experiment or observational study. It’s derived from the hypothesis and provides a measurable way to test the relationship between variables.

Here’s an example of how to write a hypothesis and a related prediction:

- Hypothesis: Consuming a high-sugar diet leads to weight gain.

- Prediction: People who consume a high-sugar diet for six weeks will gain more weight than those who maintain a low-sugar diet during the same period.

Key Differences Between a Hypothesis and a Prediction

While a hypothesis and prediction are both essential components of scientific research, there are some key differences to keep in mind:

- A hypothesis is an educated guess that suggests a relationship between variables, while a prediction is a specific and measurable outcome based on that hypothesis.

- A hypothesis can give rise to multiple experiment or observational study predictions.

To conclude, understanding the differences between a hypothesis and a prediction, and learning how to write a hypothesis, are essential steps to form a robust foundation for your research. By creating clear, testable hypotheses along with specific, measurable predictions, you lay the groundwork for scientifically sound investigations.

Here’s a wrap-up for this guide on how to write a hypothesis. We’re confident this article was helpful for many of you. We understand that many students struggle with writing their school research . However, we hope to continue assisting you through our blog tutorial on writing different aspects of academic assignments.

For further information, you can check out our reverent blog or contact our professionals to avail amazing writing services. Paper perk experts tailor assignments to reflect your unique voice and perspectives. Our professionals make sure to stick around till your satisfaction. So what are you waiting for? Pick your required service and order away!

How to write a good hypothesis?

How to write a hypothesis in science, how to write a research hypothesis, how to write a null hypothesis, what is the format for a scientific hypothesis, how do you structure a proper hypothesis, can you provide an example of a hypothesis, what is the ideal hypothesis structure.

The ideal hypothesis structure includes the following;

- A clear statement of the relationship between variables.

- testable prediction.

- falsifiability.

If your hypothesis has all of these, it is both scientifically sound and effective.

How to write a hypothesis for product management?

Writing a hypothesis for product management involves a simple process:

- First, identify the problem or question you want to address.

- State your assumption or belief about the solution to that problem. .

- Make a hypothesis by predicting a specific outcome based on your assumption.

- Make sure your hypothesis is specific, measurable, and testable.

- Use experiments, data analysis, or user feedback to validate your hypothesis.

- Make informed decisions for product improvement.

Following these steps will help you in effectively formulating hypotheses for product management.

Order Original Papers & Essays

Your First Custom Paper Sample is on Us!

Timely Deliveries

No Plagiarism & AI

100% Refund

Try Our Free Paper Writing Service

Related blogs.

Connections with Writers and support

Privacy and Confidentiality Guarantee

Average Quality Score

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Hypothesis Testing | A Step-by-Step Guide with Easy Examples

Published on November 8, 2019 by Rebecca Bevans . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics . It is most often used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses, that arise from theories.

There are 5 main steps in hypothesis testing:

- State your research hypothesis as a null hypothesis and alternate hypothesis (H o ) and (H a or H 1 ).

- Collect data in a way designed to test the hypothesis.

- Perform an appropriate statistical test .

- Decide whether to reject or fail to reject your null hypothesis.

- Present the findings in your results and discussion section.

Though the specific details might vary, the procedure you will use when testing a hypothesis will always follow some version of these steps.

Table of contents

Step 1: state your null and alternate hypothesis, step 2: collect data, step 3: perform a statistical test, step 4: decide whether to reject or fail to reject your null hypothesis, step 5: present your findings, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about hypothesis testing.

After developing your initial research hypothesis (the prediction that you want to investigate), it is important to restate it as a null (H o ) and alternate (H a ) hypothesis so that you can test it mathematically.

The alternate hypothesis is usually your initial hypothesis that predicts a relationship between variables. The null hypothesis is a prediction of no relationship between the variables you are interested in.

- H 0 : Men are, on average, not taller than women. H a : Men are, on average, taller than women.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

For a statistical test to be valid , it is important to perform sampling and collect data in a way that is designed to test your hypothesis. If your data are not representative, then you cannot make statistical inferences about the population you are interested in.

There are a variety of statistical tests available, but they are all based on the comparison of within-group variance (how spread out the data is within a category) versus between-group variance (how different the categories are from one another).

If the between-group variance is large enough that there is little or no overlap between groups, then your statistical test will reflect that by showing a low p -value . This means it is unlikely that the differences between these groups came about by chance.

Alternatively, if there is high within-group variance and low between-group variance, then your statistical test will reflect that with a high p -value. This means it is likely that any difference you measure between groups is due to chance.

Your choice of statistical test will be based on the type of variables and the level of measurement of your collected data .

- an estimate of the difference in average height between the two groups.

- a p -value showing how likely you are to see this difference if the null hypothesis of no difference is true.

Based on the outcome of your statistical test, you will have to decide whether to reject or fail to reject your null hypothesis.

In most cases you will use the p -value generated by your statistical test to guide your decision. And in most cases, your predetermined level of significance for rejecting the null hypothesis will be 0.05 – that is, when there is a less than 5% chance that you would see these results if the null hypothesis were true.

In some cases, researchers choose a more conservative level of significance, such as 0.01 (1%). This minimizes the risk of incorrectly rejecting the null hypothesis ( Type I error ).

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

The results of hypothesis testing will be presented in the results and discussion sections of your research paper , dissertation or thesis .

In the results section you should give a brief summary of the data and a summary of the results of your statistical test (for example, the estimated difference between group means and associated p -value). In the discussion , you can discuss whether your initial hypothesis was supported by your results or not.

In the formal language of hypothesis testing, we talk about rejecting or failing to reject the null hypothesis. You will probably be asked to do this in your statistics assignments.

However, when presenting research results in academic papers we rarely talk this way. Instead, we go back to our alternate hypothesis (in this case, the hypothesis that men are on average taller than women) and state whether the result of our test did or did not support the alternate hypothesis.

If your null hypothesis was rejected, this result is interpreted as “supported the alternate hypothesis.”

These are superficial differences; you can see that they mean the same thing.

You might notice that we don’t say that we reject or fail to reject the alternate hypothesis . This is because hypothesis testing is not designed to prove or disprove anything. It is only designed to test whether a pattern we measure could have arisen spuriously, or by chance.

If we reject the null hypothesis based on our research (i.e., we find that it is unlikely that the pattern arose by chance), then we can say our test lends support to our hypothesis . But if the pattern does not pass our decision rule, meaning that it could have arisen by chance, then we say the test is inconsistent with our hypothesis .

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Descriptive statistics

- Measures of central tendency

- Correlation coefficient

Methodology

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Types of interviews

- Cohort study

- Thematic analysis

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Survivorship bias

- Availability heuristic

- Nonresponse bias

- Regression to the mean

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

A hypothesis states your predictions about what your research will find. It is a tentative answer to your research question that has not yet been tested. For some research projects, you might have to write several hypotheses that address different aspects of your research question.

A hypothesis is not just a guess — it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations and statistical analysis of data).

Null and alternative hypotheses are used in statistical hypothesis testing . The null hypothesis of a test always predicts no effect or no relationship between variables, while the alternative hypothesis states your research prediction of an effect or relationship.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bevans, R. (2023, June 22). Hypothesis Testing | A Step-by-Step Guide with Easy Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved June 24, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/statistics/hypothesis-testing/

Is this article helpful?

Rebecca Bevans

Other students also liked, choosing the right statistical test | types & examples, understanding p values | definition and examples, what is your plagiarism score.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

Published on 6 May 2022 by Shona McCombes .

A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested by scientific research. If you want to test a relationship between two or more variables, you need to write hypotheses before you start your experiment or data collection.

Table of contents

What is a hypothesis, developing a hypothesis (with example), hypothesis examples, frequently asked questions about writing hypotheses.

A hypothesis states your predictions about what your research will find. It is a tentative answer to your research question that has not yet been tested. For some research projects, you might have to write several hypotheses that address different aspects of your research question.

A hypothesis is not just a guess – it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

Variables in hypotheses

Hypotheses propose a relationship between two or more variables . An independent variable is something the researcher changes or controls. A dependent variable is something the researcher observes and measures.

In this example, the independent variable is exposure to the sun – the assumed cause . The dependent variable is the level of happiness – the assumed effect .

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Step 1: ask a question.

Writing a hypothesis begins with a research question that you want to answer. The question should be focused, specific, and researchable within the constraints of your project.

Step 2: Do some preliminary research

Your initial answer to the question should be based on what is already known about the topic. Look for theories and previous studies to help you form educated assumptions about what your research will find.

At this stage, you might construct a conceptual framework to identify which variables you will study and what you think the relationships are between them. Sometimes, you’ll have to operationalise more complex constructs.

Step 3: Formulate your hypothesis

Now you should have some idea of what you expect to find. Write your initial answer to the question in a clear, concise sentence.

Step 4: Refine your hypothesis

You need to make sure your hypothesis is specific and testable. There are various ways of phrasing a hypothesis, but all the terms you use should have clear definitions, and the hypothesis should contain:

- The relevant variables

- The specific group being studied

- The predicted outcome of the experiment or analysis

Step 5: Phrase your hypothesis in three ways

To identify the variables, you can write a simple prediction in if … then form. The first part of the sentence states the independent variable and the second part states the dependent variable.

In academic research, hypotheses are more commonly phrased in terms of correlations or effects, where you directly state the predicted relationship between variables.

If you are comparing two groups, the hypothesis can state what difference you expect to find between them.

Step 6. Write a null hypothesis

If your research involves statistical hypothesis testing , you will also have to write a null hypothesis. The null hypothesis is the default position that there is no association between the variables. The null hypothesis is written as H 0 , while the alternative hypothesis is H 1 or H a .

| Research question | Hypothesis | Null hypothesis |

|---|---|---|

| What are the health benefits of eating an apple a day? | Increasing apple consumption in over-60s will result in decreasing frequency of doctor’s visits. | Increasing apple consumption in over-60s will have no effect on frequency of doctor’s visits. |

| Which airlines have the most delays? | Low-cost airlines are more likely to have delays than premium airlines. | Low-cost and premium airlines are equally likely to have delays. |

| Can flexible work arrangements improve job satisfaction? | Employees who have flexible working hours will report greater job satisfaction than employees who work fixed hours. | There is no relationship between working hour flexibility and job satisfaction. |

| How effective is secondary school sex education at reducing teen pregnancies? | Teenagers who received sex education lessons throughout secondary school will have lower rates of unplanned pregnancy than teenagers who did not receive any sex education. | Secondary school sex education has no effect on teen pregnancy rates. |

| What effect does daily use of social media have on the attention span of under-16s? | There is a negative correlation between time spent on social media and attention span in under-16s. | There is no relationship between social media use and attention span in under-16s. |

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

A hypothesis is not just a guess. It should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

A research hypothesis is your proposed answer to your research question. The research hypothesis usually includes an explanation (‘ x affects y because …’).

A statistical hypothesis, on the other hand, is a mathematical statement about a population parameter. Statistical hypotheses always come in pairs: the null and alternative hypotheses. In a well-designed study , the statistical hypotheses correspond logically to the research hypothesis.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, May 06). How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 24 June 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/hypothesis-writing/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, operationalisation | a guide with examples, pros & cons, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples.

How to Develop a Good Research Hypothesis

The story of a research study begins by asking a question. Researchers all around the globe are asking curious questions and formulating research hypothesis. However, whether the research study provides an effective conclusion depends on how well one develops a good research hypothesis. Research hypothesis examples could help researchers get an idea as to how to write a good research hypothesis.

This blog will help you understand what is a research hypothesis, its characteristics and, how to formulate a research hypothesis

Table of Contents

What is Hypothesis?

Hypothesis is an assumption or an idea proposed for the sake of argument so that it can be tested. It is a precise, testable statement of what the researchers predict will be outcome of the study. Hypothesis usually involves proposing a relationship between two variables: the independent variable (what the researchers change) and the dependent variable (what the research measures).

What is a Research Hypothesis?

Research hypothesis is a statement that introduces a research question and proposes an expected result. It is an integral part of the scientific method that forms the basis of scientific experiments. Therefore, you need to be careful and thorough when building your research hypothesis. A minor flaw in the construction of your hypothesis could have an adverse effect on your experiment. In research, there is a convention that the hypothesis is written in two forms, the null hypothesis, and the alternative hypothesis (called the experimental hypothesis when the method of investigation is an experiment).

Characteristics of a Good Research Hypothesis

As the hypothesis is specific, there is a testable prediction about what you expect to happen in a study. You may consider drawing hypothesis from previously published research based on the theory.

A good research hypothesis involves more effort than just a guess. In particular, your hypothesis may begin with a question that could be further explored through background research.

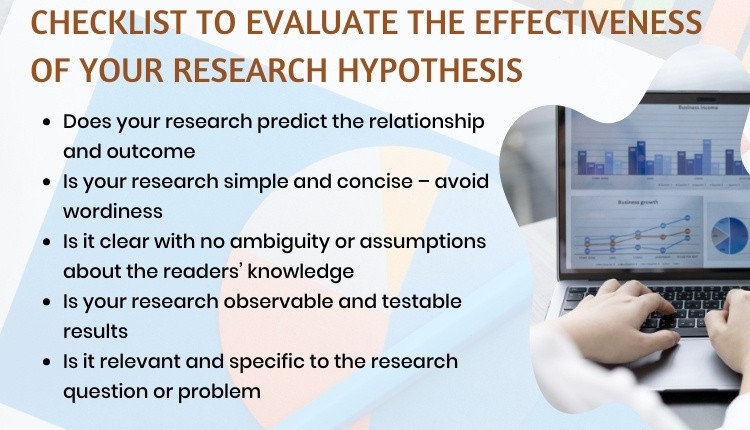

To help you formulate a promising research hypothesis, you should ask yourself the following questions:

- Is the language clear and focused?

- What is the relationship between your hypothesis and your research topic?

- Is your hypothesis testable? If yes, then how?

- What are the possible explanations that you might want to explore?

- Does your hypothesis include both an independent and dependent variable?

- Can you manipulate your variables without hampering the ethical standards?

- Does your research predict the relationship and outcome?

- Is your research simple and concise (avoids wordiness)?

- Is it clear with no ambiguity or assumptions about the readers’ knowledge

- Is your research observable and testable results?

- Is it relevant and specific to the research question or problem?

The questions listed above can be used as a checklist to make sure your hypothesis is based on a solid foundation. Furthermore, it can help you identify weaknesses in your hypothesis and revise it if necessary.

Source: Educational Hub

How to formulate a research hypothesis.

A testable hypothesis is not a simple statement. It is rather an intricate statement that needs to offer a clear introduction to a scientific experiment, its intentions, and the possible outcomes. However, there are some important things to consider when building a compelling hypothesis.

1. State the problem that you are trying to solve.

Make sure that the hypothesis clearly defines the topic and the focus of the experiment.

2. Try to write the hypothesis as an if-then statement.

Follow this template: If a specific action is taken, then a certain outcome is expected.

3. Define the variables

Independent variables are the ones that are manipulated, controlled, or changed. Independent variables are isolated from other factors of the study.

Dependent variables , as the name suggests are dependent on other factors of the study. They are influenced by the change in independent variable.

4. Scrutinize the hypothesis

Evaluate assumptions, predictions, and evidence rigorously to refine your understanding.

Types of Research Hypothesis

The types of research hypothesis are stated below:

1. Simple Hypothesis

It predicts the relationship between a single dependent variable and a single independent variable.

2. Complex Hypothesis

It predicts the relationship between two or more independent and dependent variables.

3. Directional Hypothesis

It specifies the expected direction to be followed to determine the relationship between variables and is derived from theory. Furthermore, it implies the researcher’s intellectual commitment to a particular outcome.

4. Non-directional Hypothesis

It does not predict the exact direction or nature of the relationship between the two variables. The non-directional hypothesis is used when there is no theory involved or when findings contradict previous research.

5. Associative and Causal Hypothesis

The associative hypothesis defines interdependency between variables. A change in one variable results in the change of the other variable. On the other hand, the causal hypothesis proposes an effect on the dependent due to manipulation of the independent variable.

6. Null Hypothesis

Null hypothesis states a negative statement to support the researcher’s findings that there is no relationship between two variables. There will be no changes in the dependent variable due the manipulation of the independent variable. Furthermore, it states results are due to chance and are not significant in terms of supporting the idea being investigated.

7. Alternative Hypothesis

It states that there is a relationship between the two variables of the study and that the results are significant to the research topic. An experimental hypothesis predicts what changes will take place in the dependent variable when the independent variable is manipulated. Also, it states that the results are not due to chance and that they are significant in terms of supporting the theory being investigated.

Research Hypothesis Examples of Independent and Dependent Variables

Research Hypothesis Example 1 The greater number of coal plants in a region (independent variable) increases water pollution (dependent variable). If you change the independent variable (building more coal factories), it will change the dependent variable (amount of water pollution).

Research Hypothesis Example 2 What is the effect of diet or regular soda (independent variable) on blood sugar levels (dependent variable)? If you change the independent variable (the type of soda you consume), it will change the dependent variable (blood sugar levels)

You should not ignore the importance of the above steps. The validity of your experiment and its results rely on a robust testable hypothesis. Developing a strong testable hypothesis has few advantages, it compels us to think intensely and specifically about the outcomes of a study. Consequently, it enables us to understand the implication of the question and the different variables involved in the study. Furthermore, it helps us to make precise predictions based on prior research. Hence, forming a hypothesis would be of great value to the research. Here are some good examples of testable hypotheses.

More importantly, you need to build a robust testable research hypothesis for your scientific experiments. A testable hypothesis is a hypothesis that can be proved or disproved as a result of experimentation.

Importance of a Testable Hypothesis

To devise and perform an experiment using scientific method, you need to make sure that your hypothesis is testable. To be considered testable, some essential criteria must be met:

- There must be a possibility to prove that the hypothesis is true.

- There must be a possibility to prove that the hypothesis is false.

- The results of the hypothesis must be reproducible.

Without these criteria, the hypothesis and the results will be vague. As a result, the experiment will not prove or disprove anything significant.

What are your experiences with building hypotheses for scientific experiments? What challenges did you face? How did you overcome these challenges? Please share your thoughts with us in the comments section.

Frequently Asked Questions

The steps to write a research hypothesis are: 1. Stating the problem: Ensure that the hypothesis defines the research problem 2. Writing a hypothesis as an 'if-then' statement: Include the action and the expected outcome of your study by following a ‘if-then’ structure. 3. Defining the variables: Define the variables as Dependent or Independent based on their dependency to other factors. 4. Scrutinizing the hypothesis: Identify the type of your hypothesis

Hypothesis testing is a statistical tool which is used to make inferences about a population data to draw conclusions for a particular hypothesis.

Hypothesis in statistics is a formal statement about the nature of a population within a structured framework of a statistical model. It is used to test an existing hypothesis by studying a population.

Research hypothesis is a statement that introduces a research question and proposes an expected result. It forms the basis of scientific experiments.

The different types of hypothesis in research are: • Null hypothesis: Null hypothesis is a negative statement to support the researcher’s findings that there is no relationship between two variables. • Alternate hypothesis: Alternate hypothesis predicts the relationship between the two variables of the study. • Directional hypothesis: Directional hypothesis specifies the expected direction to be followed to determine the relationship between variables. • Non-directional hypothesis: Non-directional hypothesis does not predict the exact direction or nature of the relationship between the two variables. • Simple hypothesis: Simple hypothesis predicts the relationship between a single dependent variable and a single independent variable. • Complex hypothesis: Complex hypothesis predicts the relationship between two or more independent and dependent variables. • Associative and casual hypothesis: Associative and casual hypothesis predicts the relationship between two or more independent and dependent variables. • Empirical hypothesis: Empirical hypothesis can be tested via experiments and observation. • Statistical hypothesis: A statistical hypothesis utilizes statistical models to draw conclusions about broader populations.

Wow! You really simplified your explanation that even dummies would find it easy to comprehend. Thank you so much.

Thanks a lot for your valuable guidance.

I enjoy reading the post. Hypotheses are actually an intrinsic part in a study. It bridges the research question and the methodology of the study.

Useful piece!

This is awesome.Wow.

It very interesting to read the topic, can you guide me any specific example of hypothesis process establish throw the Demand and supply of the specific product in market

Nicely explained

It is really a useful for me Kindly give some examples of hypothesis

It was a well explained content ,can you please give me an example with the null and alternative hypothesis illustrated

clear and concise. thanks.

So Good so Amazing

Good to learn

Thanks a lot for explaining to my level of understanding

Explained well and in simple terms. Quick read! Thank you

It awesome. It has really positioned me in my research project

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Reporting Research

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for data interpretation

In research, choosing the right approach to understand data is crucial for deriving meaningful insights.…

Comparing Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies: 5 steps for choosing the right approach

The process of choosing the right research design can put ourselves at the crossroads of…

- Industry News

COPE Forum Discussion Highlights Challenges and Urges Clarity in Institutional Authorship Standards

The COPE forum discussion held in December 2023 initiated with a fundamental question — is…

- Career Corner

Unlocking the Power of Networking in Academic Conferences

Embarking on your first academic conference experience? Fear not, we got you covered! Academic conferences…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Research recommendations play a crucial role in guiding scholars and researchers toward fruitful avenues of…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for…

Comparing Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies: 5 steps for choosing the right…

How to Design Effective Research Questionnaires for Robust Findings

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What would be most effective in reducing research misconduct?

Monday, July 1, 2024

- Are first-person pronouns acceptable in scientific writing?

February 23, 2011 Filed under Blog , Featured , Popular , Writing

Interestingly, this rule seems to have originated with Francis Bacon to give scientific writing more objectivity.

In Eloquent Science (pp. 76-77), I advocate that first-person pronouns are acceptable in limited contexts. Avoid their use in rote descriptions of your methodology (“We performed the assay…”). Instead, use them to communicate that an action or a decision that you performed affects the outcome of the research.

NO FIRST-PERSON PRONOUN: Given option A and option B, the authors chose option B to more accurately depict the location of the front. FIRST-PERSON PRONOUN: Given option A and option B, we chose option B to more accurately depict the location of the front.

So, what do other authors think? I have over 30 books on scientific writing and have read numerous articles on this point. Here are some quotes from those who expressed their opinion on this matter and I was able to find from the index of the book or through a quick scan of the book.

“Because of this [avoiding first-person pronouns], the scientist commonly uses verbose (and imprecise) statements such as “It was found that” in preference to the short, unambiguous “I found.” Young scientists should renounce the false modesty of their predecessors. Do not be afraid to name the agent of the action in a sentence, even when it is “I” or “we.”” — How to Write and Publish a Scientific Paper by Day and Gastel, pp. 193-194 “Who is the universal ‘it’, the one who hides so bashfully, but does much thinking and assuming? “ It is thought that … is a meaningless phrase and unnecessary exercise in modesty. The reader wants to know who did the thinking or assuming, the author, or some other expert.” — The Science Editor’s Soapbox by Lipton, p. 43 “I pulled 40 journals at random from one of my university’s technical library’s shelves…. To my surprise, in 32 out of the 40 journals, the authors indeed made liberal use of “I” and “we.” — Style for Students by Joe Schall, p. 63 “Einstein occasionally used the first person. He was not only a great scientist, but a great scientific writer. Feynman also used the first person on occasion, as did Curie, Darwin, Lyell, and Freud. As long as the emphasis remains on your work and not you, there is nothing wrong with judicious use of the first person.” — The Craft of Scientific Writing by Michael Alley, p. 107 “One of the most epochal papers in all of 20th-century science, Watson and Crick’s article defies nearly every major rule you are likely to find in manuals on scientific writing…. There is the frequent use of “we”…. This provides an immediate human presence, allowing for constant use of active voice. It also gives the impression that the authors are telling us their actual thought processes.” — The Chicago Guide to Communicating Science by Scott L. Montgomery, p. 18 “We believe in the value of a long tradition (which some deplore) arguing that it is inappropriate for the author of a scientific document to refer to himself or herself directly, in the first person…. There is no place for the subjectivity implicit in personal intrusion on the part of the one who conducted the research—especially since the section is explicitly labeled “Results”…. If first-person pronouns are appropriate anywhere in a dissertation, it would be in the Discussion section…because different people might indeed draw different inferences from a given set of facts.” — The Art of Scientific Writing by Ebel et al., p. 79. [After arguing for two pages on clearly explaining why the first person should not be used…] “The first person singular is appropriate when the personal element is strong, for example, when taking a position in a controversy. But this tends to weaken the writer’s credibility. The writer usually wants to make clear that anyone considering the same evidence would take the same position. Using the third person helps to express the logical impersonal character and generality of an author’s position, whereas the first person makes it seem more like personal opinion.” — The Scientist’s Handbook for Writing Papers and Dissertations by Antoinette Wilkinson, p. 76.

So, I can find only one source on my bookshelf advocating against use of the first-person pronouns in all situations (Wilkinson). Even the Ebel et al. quote I largely agree with.

Thus, first-person pronouns in scientific writing are acceptable if used in a limited fashion and to enhance clarity.

Isn’t it telling that Ebel et al begin their argument against usage of the first person with the phrase ““We believe …”?

That is a reall good point, Kirk. Thanks for pointing that out!

This argument is approximately correct, but in my opinion off point. The use of first person should always be minimized in scientific writing, but not because it is unacceptable or even uncommon. It should be minimized because it is ineffective, and it is usually badly so. Specifically, the purpose of scientific writing is to create a convincing argument based on data collected during the evaluation of a hypothesis. This is basic scientific method. The strength of this argument depends on the data, not on the person who collected it. Using first person deemphasises the data, which weakens the argument and opens the door for subjective criticism to be used to rebut what should be objective data. For example, suppose I hypothesized that the sun always rises in the east, and I make daily observations over the course of a year to support that hypothesis. I could say, “I have shown that the sun always rises in the east”. A critic might respond by simply saying that I am crazy, and that I got it wrong. In other words, it can easily become an argument about “me”. However, if I said “Daily observations over the course of a year showed that the sun always rises in the east”, then any subsequent argument must rebut the data and not rebut “me”. Actually, I would never say this using either of those formulations. I would say, “Daily observations over the course of a year were consistent with the hypothesis that the sun always rises in the east.” This is basic scientific expository writing.

Finally, if one of my students EVER wrote “it was found that …”, I would hit him or her over the head with a very large stick. That is just as bad as “I found that …”, and importantly, those are NOT the only two options. The correct way to say this in scientific writing is, “the data showed that …”.

In general, I agree with you. We should omit ourselves from our science to emphasize what the data demonstrate.

My only qualification is that, as scientists, the collection, observation, and interpretation of data is difficult to disconnect from its human aspects. Being a human endeavor, science is necessarily affected by the humans themselves who do the work.

Thanks for your comment!

i could not understand why 1st person I is used with plural verb

Not sure that I completely understand your question, but grammatically “I” should only be used with a singular verb. If you use “I” in scientific writing, only do so with single-authored papers.

Does that answer your question?

why do we use ‘have’ with ‘i’ pronoun?

I wouldn’t view it as “I” goes with the plural verb “have”, but that “have” can be used with a number of different persons, regardless of whether it is singular or plural.

First person singular: “I have” Second person singular: “You have” Third person singular: “He/She/It has”

First person plural: “We have” Second person plural: “All of you have” Third person plural: “They have”

I know it perhaps doesn’t make sense, but that is the way English works.

I hope that helps.

I think there are a few cases where personal pronouns would be acceptable. If you are introducing a new section in a thesis or even an article, you might want to say “we begin with a description of the data in section 2” etc, rather than the cumbersome “this paper will begin with …”. Also in discussions of future work, it would make sense to say “we intend to explore X, Y and Z”.

I loved reading this, my Prof. and I were debating about this. He wants me to say “I analyzed” and I want to say “problem notification database analysed revealed that…”

I’m writing a paper for a conference. I wonder if I can defy a Professor in Korea:)

I disagree that writing in the 3rd person makes writing more objective. I also disagree that it “opens the door for subjective criticism to be used to rebut what should be objective data”. In fact, using the 3rd person obstructs reality. There are people behind the research who both make mistakes and do great things. It is no less true for science than it is for other subjects that 3rd person obstructs the author of an action and makes the idea being conveyed less clear. I find it odd that scientific writing guides instruct authors to BOTH use active voice AND use only the 3rd person. It is impossible to do both. Active voice means that there is a subject, a strong verb (not a version of the verb “to be”) and an object. When I say “The solution was mixed”, it is BOTH 3rd person and passive voice. The only way to construct that sentence without passive voice is to say “We mixed the solution”. Honestly, after spending most of the first part of my life in English classes and then transitioning to science, I find most scientific writing an abomonination.

Hi Kathleen,

I think it is great that you have had your feet in both English and science. For many of us who have struggled as writers, those people are great role models to aspire to.

An anecdote: my wife’s research student turned in a brief report on his work to date. She was showing me how well written his work was, really pretty advanced for an undergrad physics student. Later, she found out that he was trying to decide between majoring in physics and majoring in English.

Hi David. Thanks very much for your tips. Very interesting article. Did you just tweet that you should keep “I” and “We” out of the abstract? I am translating a psychology article from Spanish into English, and I’ve come up against an unwieldly sentence (the very last one in the abstract) that basically wants to say “We propose a number of strategies for improving the impact of the psychological treatments[…]” Would you say it’s a no-no? I tend to avoid personal pronouns in academic articles as much as poss, but it just sounds like the most natural option in this case. Perhaps I could put, “This article proposes a number of treatments…”? Strictly speaking it’s not the article that’s doing the proposing, obviously. I’d be very grateful to have your opinion. Thanks a lot. Best regards. Louisa

Yes, it’s difficult. How about going passive? “A number of treatments are proposed….”?

The comments against using first person, which are rampant in science education, are silly. Go read Nature or Science. I believe Kathleen makes a fantastic point.

Just happened across this blog while searching for something else, and procrastination rules, ok?

My pet hate is lecturers who uncritically criticise students for using the third person. Close behind is institutional guidance/insistence on third person ‘scientific writing’. Both are hugely ironic, the first because it is typically uncritical and purely traditional (we are employed to teach others to be critical and challenge tradition), the second because there is so little empirical evidence to suggest that the scientific method is third person.

I very much appreciated Bill Lott’s response because a) it was critical and b) it discussed the issue of good and bad writing as opposed to first and third person. However I would still suggest that the way he would report his exemplar data is all but first person:

“Daily observations over the course of a year were consistent with the hypothesis that the sun always rises in the east.”

Who did the observations if not the first person? All that is missing is My or Our at the beginning of the sentence and hey presto

Another facet of writing is that it disappears if not frequently watered and tended to.

Even though this is an old article, I’d like to add my 2c to the thread.

I think the use of the 3rd person is pompous, verbose and obtuse – it uses many words to say the same thing in a flowery way.

“It is the opinion of the author that” as opposed to “I think that”

Anybody reading the article knows that it’s written by a person / persons who did the research on the topic, who are either presenting their findings or opinion. The whole 3rd person thing seems to be a game, and I for one, HATE writing about myself in the 3rd person.

That being said, it seems to be the convention that the 3rd person is used, and I probably will write my paper in the 3rd person anyway, just to not rock the boat.

But I wish that the pomposity would stop and we would get more advocates for writing in plain English.

Hi, i was wondering… can “We” be said in a scientific school report?

Depends on the context, I guess. I would follow the same advice as above.

Thanks for all the tips. Don’t forget that in the future historians are going to want to know who did what and when. Scientists may not think it important, but historians will (especially if it is a significant contribution). Furthermore, by not revealing particulars regarding individual contributions opens the door for many scientists to falsify the historical record in their favor (I have experienced this first hand in a recent publication).

i think it is soo weird to use first person in reports…….third persons will be more effective when used and that will give a clear explanations to the audience

Even Nature journals are encouraging “we” in the manuscript.

“Nature journals prefer authors to write in the active voice (“we performed the experiment…”) as experience has shown that readers find concepts and results to be conveyed more clearly if written directly.”

https://www.nature.com/authors/author_resources/how_write.html

[…] Is trouwens iets dat blijkbaar al lang voor discussies zorgt, als je deze links bekijkt: Are first-person pronouns acceptable in scientific writing? : eloquentscience.com Use of the word "I" in scientific papers Zelfs wikipedia heeft er een artikel over: […]

[…] There was some discussion on Twitter about whether or not to write in the 1st person. The Lab & Field pointed out that Francis Bacon may have been responsible for the movement to avoid it in scientific writing… […]

[…] ¿Son aceptables los pronombres en primera persona en publicaciones científicas? [ENG] […]

[…] do discuss this among themselves. For example, see Yateendra Joshi and Professor David M. Schultz. Professor Schultz notes that the use of the first person in science appears to be as common among […]

[…] http://eloquentscience.com/2011/02/are-first-person-pronouns-acceptable-in-scientific-writing/ […]

[…] There’s no rule about the passive voice in science. People seem to think that it’s “scientific” writing, but it isn’t. It’s just bad writing. There’s actually no rule against first person pronouns either! Read this for more on the use of the first-person in scientific writing. […]

To order, visit:

The American Meteorological Society (preferred)

The University of Chicago Press

eNews & Updates

Sign up to receive breaking news as well as receive other site updates!

David M. Schultz is a Professor of Synoptic Meteorology at the Centre for Atmospheric Science, Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, and the Centre for Crisis Studies and Mitigation, The University of Manchester. He served as Chief Editor for Monthly Weather Review from 2008 to 2022. In 2014 and 2017, he received the University of Manchester Teaching Excellence Award, the only academic to have twice done so. He has published over 190 peer-reviewed journal articles. [Read more]

- Search for:

Latest Tweets

currently unavailable

Recent Posts

- Top 40 potential questions to be asked in a PhD viva or defense

- Free Writing and Publishing Online Workshop: 19–20 June 2024

- Editorial: How to Be a More Effective Author

- How to be a more effective reviewer

- The Five Most Common Problems with Introductions

- Eliminate excessive and unnecessary acronyms from your scientific writing

- Chinese translation of Eloquent Science now available

- How Bill Paxton Helped Us Understand Tornadoes in Europe

- Publishing Academic Papers Workshop

- Past or Present Tense?

- Rejected for publication: What now?

- Thermodynamic diagrams for free

- Do you end with a ‘thank you’ or ‘questions?’ slide?

- Presentations

Copyright © 2024 EloquentScience.com · All Rights Reserved · StudioPress theme customized by Insojourn Design · Log in

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write a Great Hypothesis

Hypothesis Definition, Format, Examples, and Tips

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Verywell / Alex Dos Diaz

- The Scientific Method

Hypothesis Format

Falsifiability of a hypothesis.

- Operationalization

Hypothesis Types

Hypotheses examples.

- Collecting Data

A hypothesis is a tentative statement about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in a study. It is a preliminary answer to your question that helps guide the research process.

Consider a study designed to examine the relationship between sleep deprivation and test performance. The hypothesis might be: "This study is designed to assess the hypothesis that sleep-deprived people will perform worse on a test than individuals who are not sleep-deprived."

At a Glance

A hypothesis is crucial to scientific research because it offers a clear direction for what the researchers are looking to find. This allows them to design experiments to test their predictions and add to our scientific knowledge about the world. This article explores how a hypothesis is used in psychology research, how to write a good hypothesis, and the different types of hypotheses you might use.

The Hypothesis in the Scientific Method

In the scientific method , whether it involves research in psychology, biology, or some other area, a hypothesis represents what the researchers think will happen in an experiment. The scientific method involves the following steps:

- Forming a question

- Performing background research

- Creating a hypothesis

- Designing an experiment

- Collecting data

- Analyzing the results

- Drawing conclusions

- Communicating the results

The hypothesis is a prediction, but it involves more than a guess. Most of the time, the hypothesis begins with a question which is then explored through background research. At this point, researchers then begin to develop a testable hypothesis.

Unless you are creating an exploratory study, your hypothesis should always explain what you expect to happen.