How to Write a Great Plot

What Is a Plot?

When we talk of a story’s plot , we typically refer to the sequence of cause-and-effect events that make up the storyline , connecting the story elements to build meaning and engagement with an audience.

Think of a plot like a roadmap. navigating you through the highs and lows of the story revolving around characters and setting, which leads us to a conflict and eventual resolution.

A good plot should keep you engaged, surprising you with twists and turns and moving you towards a satisfying conclusion. It’s what makes a story more than just a collection of random events and gives it direction and purpose.

The plot is arguably the most critical element of a story and can be approached from two perspectives; a traditional approach which is the main focus of this guide, known as a Plot- Driven Narrative (or commonly just a plot) and another popular approach that tells a story through the lens of a stories protagonist known as a C haracter-Driven narrative.

Let’s take a moment to explore the similarities and differences to these storytelling methods.

Plot-Driven Narratives Vs. Character Driven Narratives

These two types of stories account for the narrative structures of most books, movies, plays, and TV dramas. They represent two distinct approaches to storytelling. For students to get good at writing great plots, they should first learn to distinguish between these two perspectives on storytelling.

Character-driven stories focus primarily on the who of the story. They predominantly concern themselves with the inner lives of their protagonists and how events in the outside world affect them psychologically.

In character-driven stories, we follow the struggles and experiences of the story’s characters which usually culminate in a climax that results in a profound change in the life or psychology of the main character.

The critical element of this type of story is character development, which is commonly found in literary fiction.

When exploring a traditional plot or Plot-Drive n Narrative, think of a story propelled forward by the events and actions within it. This is what we call a plot-driven narrative. It’s like a boat that’s pushed forward by the mighty waves of the story’s events, with the characters simply along for the ride.

Plot-driven narratives are focused on the “what” of a story rather than the “who.” They’re driven by twists, turns, and unexpected occurrences, with the goal of keeping the audience engaged and entertained. So, if you love a good mystery or action-packed adventure, a plot-driven narrative might be the path for you to pursue when writing a narrative.

Famous Character-Driven Stories

- The Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man by James Joyce

- The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger

- Steppenwolf by Herman Hesse

- Raging Bull

- The Godfather

Famous Plot-Driven Stories

- Lord of the Rings by JRR Tolkien

- Jurrasic Park by Michael Crichton

- Da Vinci Code by Dan Brown

Whether a story is primarily plot-driven or character-driven, it will require well-drawn characters and a solidly constructed plot to be a good story.

In the rest of this article, we’ll look at the plot’s main elements, some specific plots, and how students can create great plots for their own fantastic stories. We’ll also suggest activities to help students hone their skills in these areas.

THE STORY TELLERS BUNDLE OF TEACHING RESOURCES

A MASSIVE COLLECTION of resources for narratives and story writing in the classroom covering all elements of crafting amazing stories. MONTHS WORTH OF WRITING LESSONS AND RESOURCES, including:

What Are The key Parts of a Plot?

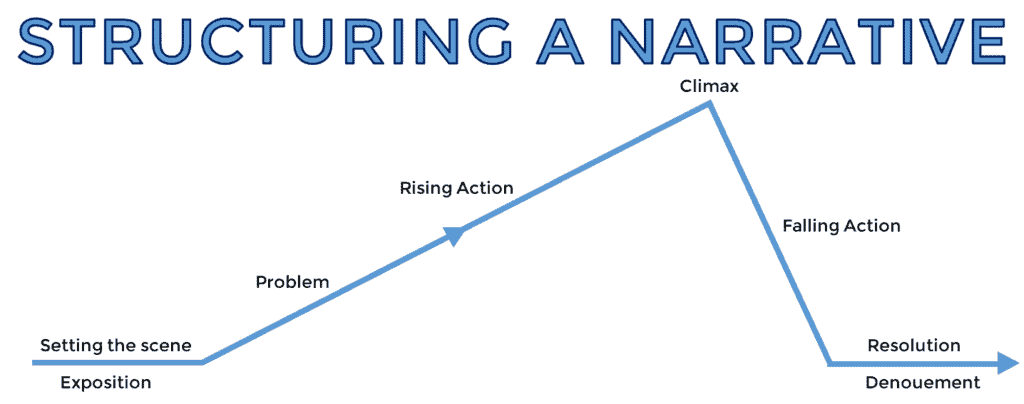

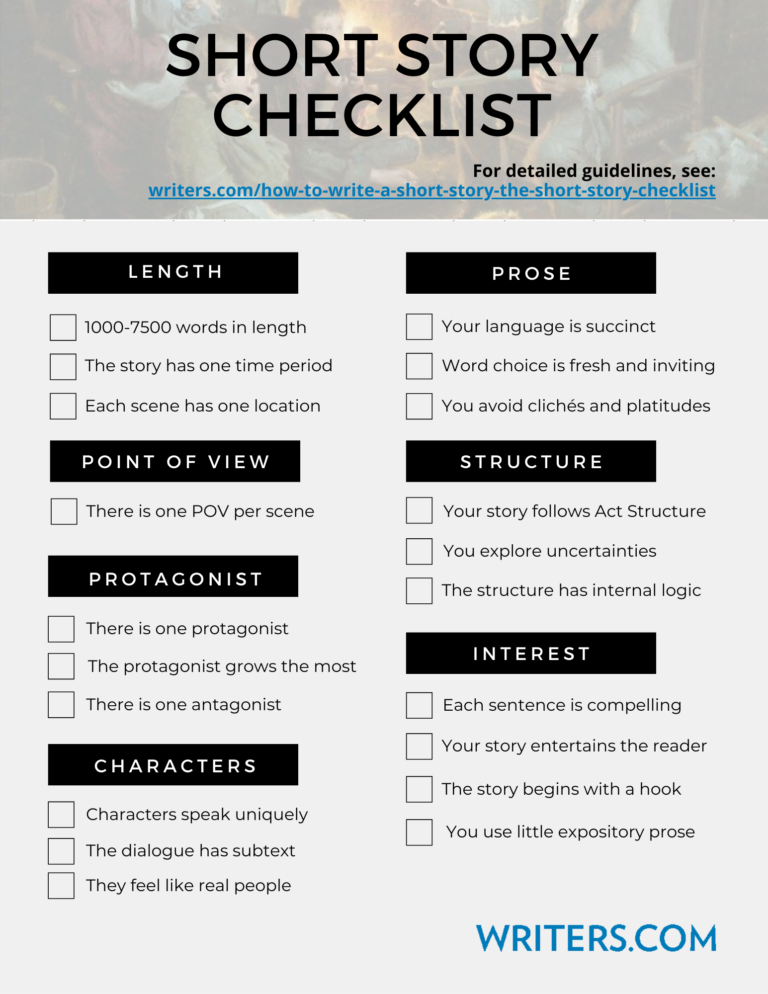

There are six main elements of plot for students to identify and master. These are:

- Conflict or Inciting Incident

- Rising Action

- Falling Action

Below, you’ll find an outline of each element in turn, but if you want to explore these elements in greater detail with your students, check out Our Complete Guide to Narrative Writing here .

1. Exposition

Exposition is all about laying the groundwork. The writer sets the scene in the first paragraphs and introduces the main characters. The exposition orients the reader to the fictional world they are entering.

2. Conflict/Inciting Incident

Every story needs a problem to drive the plot forward. We call this the ‘conflict’ or ‘inciting incident.’ At this stage of the narrative, an incident or a conflict occurs that sees the main character facing a challenge of some sort. This breaks the normality established in the exposition by setting a chain of events in motion that will form the story’s plot.

3. Rising Action

The conflict/inciting event sets off a sequence of causally linked episodes that gradually amp up the dramatic tension as the story builds towards the climax. This process of building tension through raising the stakes is called rising action.

The climax is the dramatic high point of the story, where everything comes to a head. This is where the story’s conflict will ultimately be resolved, usually in a moment of high excitement.

5. Falling Action

As the dramatic tension gets released in the excitement of the climax, the narrative begins to wind down. As the dust settles on the climactic scene, we begin to see the consequences on the characters and the world around them.

6. Resolution/Denouement

Sometimes known as a denouement, the resolution is the plot’s final section, where the conflict’s loose ends are tied up. This section has a finality as it establishes new normalcy in the wake of recent events.

The Classic Three Act Plot Structure Explained

If you are looking for the 5-minute explanation of how to write a strong plot without going into too many details and complexity, allow me to introduce you to the granddaddy of all story structures: the three-act plot. Think of it as a theatrical performance, with each act serving a specific purpose in the storytelling journey.

Act 1, is all about setup : It’s here where you introduce your characters, establish the setting, and create a sense of what’s at stake in the story.

Act 2 is where the drama takes center stage : At this point conflict arises, obstacles are placed in the characters’ way, and tensions rise and grow.

And finally, Act 3 is the grand finale : Where all the story threads come together in a resolution. Loose ends are tied up, conflicts are resolved, and your audience gets the payoff they’ve been waiting for.

So, there it is, next time you’re crafting a story, consider using this tried and true three-act structure to guide your plot and keep your audience engaged.

The & Basic Plot Types (With Prompts)

In the book world, we commonly find plot-driven genre fiction topping the paperback bestseller lists. In fact, most popular fiction known as ‘genre fiction’ is plot-driven.

Genre fiction comes in many forms, for example, science fiction, romance, fantasy, thrillers, and horror, to name but a few.

Whatever the genre, we find many of the same plot types recurring within the well-thumbed pages of these most popular of books. For students to write their own great plots, they’ll need to understand the time-tested seven basic patterns that plots follow.

Let’s take a look at the most common of these plot types along with a writing prompt to get your students to write an example of each.

A genre with ancient roots, tragedies focus on events of great sorrow, suffering, distress and/or destruction. With roots in ancient Greek drama, tragedy treats the plot and the themes it raises with a serious and sombre tone.

Examples: Oedipus Rex by Sophocles, The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood

Prompt: A story opens with the hero’s untimely death. Can the student go back and tell the story of how events led to such a tragedy?

For the ancient Greeks, comedy represented the dramatic opposite of tragedy. Where tragedy is serious and somber, comedy is light-hearted and humorous. Comedy has many subgenres, including sarcasm , parody, farce, satire, slapstick, romantic comedy, screwball, and even dark humor.

Examples: A Midsummer Night’s Dream by William Shakespeare, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams.

Prompt: There is a man who, due to a rare condition, cannot lie. No matter how desperately he wants to avoid telling the truth, he just cannot lie. What happens next?

iii. The Quest

As its name suggests, the quest plotline involves a journey of some sort to find a particular person, place, or item. Sometimes the quest is in pursuit of fame or fortune. Often, the thing being sought isn’t as important as the drama that happens along the way.

Examples: The Hobbit by JRR Tolkien, Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark

Prompt: A young girl escapes from her unhappy home and her mean stepmother in search of a better future. Write what happens to her.

iv. The Voyage and Return

In some ways similar to the quest, except there is the added element of the return home. Typically, the hero enters a new land (often magical) where things are very different. Eventually, the hero, changed by events, returns home. Having learned some important lessons, they bring that new knowledge or discovery back home with them.

Examples: Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L Frank Baum

Prompt: A prince is engaged to be married to a princess. She has been kidnapped by an evil rival. The prince must journey to find her with the hopes of bringing her home.

v. The Monster

In this type of plot, the hero must eliminate the threat posed by some sort of beast or evil entity such as a dragon, vampire, ghost, or demon. By destroying this monster, the hero will restore order and safety to the world.

Examples: Dracula by Bram Stoker, Jack and the Beanstalk (Traditional)

Prompt: The sea beast arises from the dark depths of the oceans and develops a taste for human flesh. The hero must find a way to stop this evil predator before his whole village is wiped out.

vi. Rebirth

Here, we witness the events leading to the redemption and rebirth of the main character who previously struggled with their place in the world. At the end of this type of story, there is a shift where the world is restored to a balance.

Examples: A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens, Lion King

Prompt: A cruel orphanage owner stumbles across a foundling in the forest. This event sets in action a chain of events that leads to the orphanage owner’s redemption. Write what happens.

vii. Rags to Riches

This plot type charts the hero’s rise from humble origins through adversity to the heights of fame and fortune.

Examples: Great Expectations by Charles Dickens, The Pursuit of Happyness

Prompt: A neglected child escapes from her unhappy home and struggles to provide for herself in the cold, uncaring city. One day, she meets an unlikely benefactor, beginning a sequence of events that will forever change her life. Write what happens.

How to Write a Great Plot: A Step-by-Step Process

Step 1: Generate Some Ideas

A story begins with the seed of an idea. Students can begin this process by deciding on one of the basic plot types above and then brainstorming a list of five events that might ignite a story.

Encourage the students to draw on their own life experiences, that of their friends and family members, and on things they’ve read about or seen on the news, for example.

Step 2: Create a Premise

Once they have the initial germ of an idea, it’s time to get the premise written down. The premise is a few sentences that express the proposed plot of the story in simple terms.

Step 3: Choose Characters and a Setting

Now it’s time to create the characters and choose the settings for the tale’s action to be played out. Writing brief character profiles, including some bullet points of their backstories, can be a great way to help the student build believable characters.

For settings, creating a collage from photos, pictures, and illustrations can be an effective way to inspire vivid descriptions in the student’s work.

With these elements in place, the students can begin writing the exposition part of their stories.

Step 4: Introduce the Central Conflict

No problem = no story!

Whether it’s called the central conflict, problem, or inciting incident, the student now needs to introduce it to anchor the plot and begin creating tension in the story.

At this point, examining this element in well-known stories in the same genre will be helpful for the student.

Ask the students to think about their favorite books and movies. Can they identify the central conflict in each?

Step 5: Map Out a Path to the Resolution

With the central conflict firmly in place, a set of logical cause-and-effect dominoes now needs to be set up to take the plotline up the ladder of rising action to the climax and subsequent resolution.

Storyboarding is a highly effective way of helping students visualize their plot arc before committing to writing. Remind students of the importance of ensuring each scene connects causally.

When the climax has been reached, the dust will settle in the falling action to reveal the consequences of the actions and see new normalcy established in the resolution.

Tips for Writing a Great Plot

- Start with a strong hook: Begin your story with an interesting and attention-grabbing scene to grab your reader’s attention .

- Know your genre: Study the conventions and expectations of the genre you write in, so you can effectively play within those boundaries.

- Create memorable characters: Develop dynamic and compelling characters that drive the story forward.

- Build conflict: Your story needs conflict, whether it’s internal or external, to keep the plot moving.

- Use the three-act structure: Follow the classic three-act structure of setup, confrontation, and resolution to keep your plot structured and focused.

- Introduce twists and turns: Add unexpected events and plot twists to keep your audience engaged and on their toes.

- Keep it simple: Avoid complicating your plot with too many subplots or unnecessary details.

- Use foreshadowing: Plant hints and clues throughout the story to create suspense and keep your audience guessing.

- Have a clear resolution: Make sure your story has a satisfying conclusion that wraps up loose ends and resolves conflicts.

- Write with passion: Write from the heart, imbuing your plot with your own experiences and emotions to create a story that resonates with your reader.

A COMPLETE UNIT ON TEACHING STORY ELEMENTS

☀️This HUGE resource provides you with all the TOOLS, RESOURCES , and CONTENT to teach students about characters and story elements.

⭐ 75+ PAGES of INTERACTIVE READING, WRITING and COMPREHENSION content and NO PREPARATION REQUIRED.

Plot Teaching Strategies and Activities

Following the structural elements laid out above, combined with the conventions of a basic plot type chosen from the seven types above, students should be well-placed to construct a well-ordered plotline.

If the above description of how to write a great plot seems too prescriptive initially, it’s worth noting that there is considerable creative freedom within the structures described in this article.

The plot types listed above have been identified from the shapes and patterns of thousands of our favorite tales told across the centuries rather than being templates that are laid out to be studiously followed. As humans, we are pattern-recognizing machines. It is in patterns that we find meaning.

Teaching Activities

- Story mapping: Have students create visual representations of the events and elements in a story to help them understand the structure of a plot.

- Analyzing plot in literature: Analyze and discuss the plot structure of well-known books and movies to see how different elements contribute to the overall story.

- Plot planning worksheet : Provide students with a worksheet or graphic organizer such as this to plan out their own story, including key events, characters, and conflicts.

- Writing workshops: Encourage students to workshop their own stories with peers, providing feedback on plot structure and pacing.

- Create story arcs: Teach students about the basic story arc and have them practice creating their own arcs for short stories or character arcs for longer works.

Once students get used to these underlying structures, they can begin to let their imaginations run away with them, safe in the knowledge that a coherent story will emerge from their bursts of creativity.

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Writing Techniques

- Planning Your Writing

What Makes a Good Plot? A Guide to Character, Conflict, & More

Last Updated: May 17, 2024 Fact Checked

Outlining, Structure, & Worldbuilding

Creating unique characters, adding conflict & style, expert q&a.

This article was written by Lydia Stevens and by wikiHow staff writer, Finn Kobler . Lydia Stevens is the author of the Hellfire Series and the Ginger Davenport Escapades. She is a Developmental Editor and Writing Coach through her company "Creative Content Critiquing and Consulting." She also co-hosts a writing podcast on the craft of writing called "The REDink Writers." With over ten years of experience, she specializes in writing fantasy fiction, paranormal fiction, memoirs, and inspirational novels. Lydia holds a BA and MA in Creative Writing and English from Southern New Hampshire University. There are 12 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 215,659 times.

Plotting a narrative can be one of the most rewarding tasks for writers…but where do you begin? A good plot is well-structured, and bursting with conflict and character. In this article, we’ll offer you an expert guide on how to craft all three to make your story engaging from beginning to end. Whether it’s a novel, a script, or a short story, by the time you’re done reading, you’ll have plenty of tools to make your tale pop. This article is based on an interview with our author and developmental editor, Lydia Stevens. Check out the full interview here.

Things You Should Know

- Begin plotting your story by writing down concepts you find interesting. These initial ideas can be detailed (two opposing samurai falling in love) or simple (a story about grief).

- A good plot requires a relatable protagonist that reacts to situations organically. The best way to create a dynamic character is to give them clear goals and flaws.

- Conflict adds tension to your plot. Place your characters in situations where they struggle and increase the difficulty as your story progresses.

- Consider getting a notepad. The act of writing by hand can get your ideas flowing more freely.

- Instead of saying a character is sad, show them holding back tears or maintaining a stoic expression while everyone around them is joyous.

- Comedy: These stories are usually shorter and meant to showcase the absurdity or silliness of human nature. Characters are often more broad, and the resolutions are usually happy. (Examples: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Much Ado About Nothing, Don Quixote )

- Tragedy: A character has a major flaw that ends up being their undoing. Endings are often sad, as a once happy protagonist falls from grace. (Examples: Macbeth, Oedipus Rex, Hamilton )

- Hero’s Journey: A protagonist goes on a quest to get somewhere or find a special object. They face obstacles and meet people that teach them along the way. (Examples: The Odyssey, The Lord of the Rings, Interstellar )

- Rags to Riches: A poor character acquires wealth, power, or status, loses it, then must fight to gain it back. These stories often explore the nature of power and responsibility. (Examples: Aladdin, Jane Eyre, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory )

- Rebirth: An event (either supernatural or realistic) forces a jaded or corrupt character to live a better, more generous life. These stories often have spiritual themes and draw from religious texts for inspiration. (Examples: Pride and Prejudice, Beauty and the Beast, Groundhog Day )

- Overcoming the monster: A battle of Good vs. Evil where a character must fight an opposing force that threatens the well-being of their family, home, or overall status quo. (Examples: Star Wars, Dracula, Perseus)

- Voyage and Return: A character visits a strange new world, adapts to it, and returns home with a new perspective on life. (Examples: The Wizard of Oz, Gulliver’s Travels, The Lion King )

- Dialogue: Have your characters talk about their lives in conversation.

- Narration: Let the audience hear what’s going on inside your character’s head and how they feel about the world around them. This usually works better in prose.

- Conflict: Have your character face an obstacle early on to show what they stand for.

- Objects and symbols: Focus on items (newspaper clippings, household furniture, clothes) that give a clear picture of the world your character lives in.

- Try to make your status quo contrast with the journey you plan on sending your character on. The further your characters venture out of their comfort zone, the more opportunity they have to grow.

- Character vs. self has a character working through their own inner demons and flaws. These stories are often dramas, tragedies, and tales of rebirth. (Examples: Good Will Hunting, Emma, Hamlet )

- Character vs. character is the most common conflict; a protagonist must fight an antagonist who challenges their core values. These stories can be any genre but usually fall into the “Overcoming the Monster” plot. (Examples: Star Wars, Othello, Crime and Punishment )

- Character vs. society explores your protagonist challenging the social norms and bigotry of the people around them. These stories are often farcical comedies or have strong undercurrents of social commentary. (Examples: To Kill a Mockingbird, The Color Purple, Blazing Saddles )

- Character vs. supernatural has the character fighting against a force with special powers. These stories are always fiction, usually sci-fi or fantasy. (Examples: Harry Potter, The Odyssey, Ghostbusters )

- Character vs. technology has a protagonist fighting against a machine or technological advancement (usually one similar to a device that’s taking off in the real world, like AI). These stories are usually a form of science fiction, but they can be any genre. (Examples: Blade Runner, 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Matrix )

- Character vs nature stories are often visual. The protagonist must fight against the natural world. These stories are very adventure-based. (Examples: Cast Away, Hatchet, The Martian )

- Pay attention to cause-and-effect in your rising action. Every action has a reaction, and no events are random. Each decision the character makes should affect future situations. [10] X Research source

- The best structure to create a meaningful rising action is “[Character] did _____. Because of that, _____ happened so they _____.”

- Utilize your world to impact your rising action, too. For example, if your character lives on Mars 3000 years in the future, your character should probably deal with struggles unique to that planet, rather than common Earth problems. [11] X Research source

- In Oedipus Rex , the climax occurs when Oedipus realizes his hubris has made him fulfill the prophecy so he blinds himself as punishment for his actions. Because this story is a tragedy, the climax is dark, sad, and violent.

- In Shrek , the climax comes from the reveal that Fiona is an ogre too. Because the film is a subversive comedy about beauty standards, the silly plot twist matches the movie’s tone.

- In Little Red Riding Hood , the falling action covers the part where the Woodsman finds Little Red and saves her from the Big Bad Wolf. Because Little Red learns her lesson on gullibility in the climax (when she discovers Granny’s been eaten), her resolution is happy and simple.

- To create a more effective conclusion, set up story beats early on that you can pay off later. For example, at the beginning of Game of Thrones , Theon Grey Joyce betrays the Stark family. However, he ends the series fighting (and dying) to protect their name.

Rain Kengly

"If you find yourself struggling to plot a story from beginning to end, start with the ending and work backward! Knowing how and where you want your story to end can help you understand what developments your characters must have to get there."

- Does your character like attention or avoid it?

- How big of a role does fear play in their day-to-day activities?

- Does your character think they’re intelligent or dumb? How would they define these words?

- Does your character prefer to leap into action or stay back and think?

- What are your characters’ regrets?

- If your plot is a fantasy epic, your characters may have lofty, larger-than-life ambitions like finding a magic amulet or gaining special powers. For a more subtle drama, their wishes may be smaller: love, getting into the right college, reuniting with family, etc.

- For example, if you have an uncle who’s a hypochondriac and a friend who wants to be a stuntman, you could combine these to create a character who loves stunts but is afraid of the toll it takes on their body.

- Keep a journal to write down what people in your life say. In art and life, people’s dialogue often reflects who they are.

Draw inspiration for a variety of sources. "Ideas seem to come from everywhere – my life, everything I see, hear, and read, and most of all, from my imagination. I have a lot of imagination."

- Set up a need, as well as a want. Ideally, your character will have a clear goal as well as a lesson they must learn to live a better life. It’s more realistic and satisfying if a character doesn’t necessarily get what they want, but, as the Rolling Stones sing, gets what they need.

- Create irreversible consequences. Every decision your character makes should set off a new chain of events. Results can be good or bad, but no choices happen in a vacuum; they should make an impact in some way.

- Let the character show their strengths and overcome weaknesses. Giving your characters skills that they can apply on their journey allows them to be more directly involved in the story.

- Create a dark night of the soul. At one point in the story, your character should feel like all is lost. This surrender offers them a new perspective that they can use to re-evaluate their goals.

- Mirror subplot: A smaller-scale conflict that mirrors the main conflict which helps teach the character how to resolve the core issue.

- Contrasting subplot: A secondary character facing similar circumstances and dilemmas as the main character, but making different decisions that have a polar opposite (and often less effective) outcome.

- Complicating subplot: A secondary character making things worse for the main character. These subplots often appear right around the middle of the story to raise the stakes once the character feels comfortable.

- Romantic subplot: A relationship that often complicates or adds risk to the main plot.

- For example, in Die Hard, John McClane must overcome his fear of heights and save his relationship, or else the terrorists will succeed and harm innocent people.

- Your “or else” doesn’t always have to be life or death. The stakes just have to feel heavy for your character. For example, in Up , if Carl doesn’t fly his house away, he’ll be fine physically (and go to a nice retirement home). However, he’ll feel like he disappointed Ellie, his late wife.

- Adding a ticking clock is a great way to make your “or else” more clear and specific. Give a set time frame that your character has to complete their goal, and clarify what will happen if they fail to meet this deadline.

- Chekov's Gun: An object appearing to be insignificant later resolves the conflict.

- Flashback: A recount of events that happened before the current story, which fills in crucial backstory.

- MacGuffin: An object or goal that the protagonist is motivated to pursue which makes their life more difficult.

- Deux Ex Machina: A resolution that appears to come out of the blue.

- Dramatic Irony: A situation where the audience knows something the character doesn’t (that often leads to the character’s downfall).

- In addition, pace your story so it gets more compelling as it goes along. Don’t overload your story’s beginning with tension; distribute action and conflict equally throughout the piece. The more your narrative builds, the more invested your audience will be!

- Remember: your plot is allowed to change. It’s not finalized until the very end. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Never, ever, ever, scrap an idea just because it looks silly. One person's goofy idea is the other one's brilliant masterpiece. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

- ↑ Lucy V. Hay. Professional Writer. Expert Interview. 16 July 2019.

- ↑ Lydia Stevens. Author & Developmental Editor. Expert Interview. 1 September 2021.

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/brainstorming/

- ↑ https://www.booksoarus.com/6-ways-write-effective-exposition-examples/

- ↑ https://lewisu.edu/writingcenter/pdf/narrative-elements-1.pdf

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/subject_specific_writing/creative_writing/creative_nonfiction/index.html

- ↑ https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/exploring-movie-construction-and-production/chapter/3-what-are-the-mechanics-of-story-and-plot/

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/subject_specific_writing/creative_writing/fiction_writing_basics/index.html

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/subject_specific_writing/creative_writing/characters_and_fiction_writing/writing_compelling_characters.html

- ↑ https://www.nownovel.com/blog/detailed-character-arc-template/

- ↑ https://storybilder.com/blog/types-subplots

- ↑ https://www.writersdigest.com/write-better-fiction/how-to-raise-the-stakes-in-your-first-50-pages-of-your-novel

About This Article

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Feb 12, 2020

Did this article help you?

Anastasia Parrish

Feb 11, 2017

Nov 25, 2017

Josh Appleby

Jul 13, 2020

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

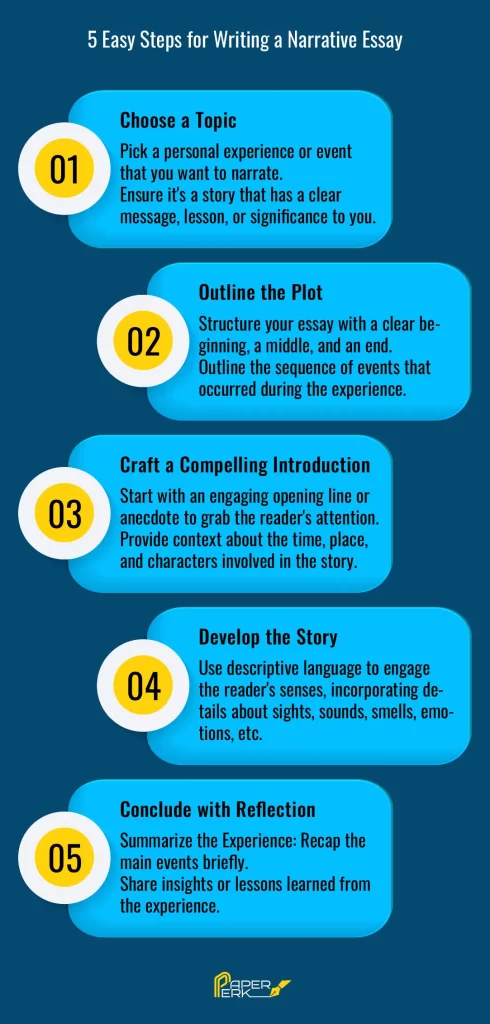

The Ultimate Narrative Essay Guide for Beginners

A narrative essay tells a story in chronological order, with an introduction that introduces the characters and sets the scene. Then a series of events leads to a climax or turning point, and finally a resolution or reflection on the experience.

Speaking of which, are you in sixes and sevens about narrative essays? Don’t worry this ultimate expert guide will wipe out all your doubts. So let’s get started.

Table of Contents

Everything You Need to Know About Narrative Essay

What is a narrative essay.

When you go through a narrative essay definition, you would know that a narrative essay purpose is to tell a story. It’s all about sharing an experience or event and is different from other types of essays because it’s more focused on how the event made you feel or what you learned from it, rather than just presenting facts or an argument. Let’s explore more details on this interesting write-up and get to know how to write a narrative essay.

Elements of a Narrative Essay

Here’s a breakdown of the key elements of a narrative essay:

A narrative essay has a beginning, middle, and end. It builds up tension and excitement and then wraps things up in a neat package.

Real people, including the writer, often feature in personal narratives. Details of the characters and their thoughts, feelings, and actions can help readers to relate to the tale.

It’s really important to know when and where something happened so we can get a good idea of the context. Going into detail about what it looks like helps the reader to really feel like they’re part of the story.

Conflict or Challenge

A story in a narrative essay usually involves some kind of conflict or challenge that moves the plot along. It could be something inside the character, like a personal battle, or something from outside, like an issue they have to face in the world.

Theme or Message

A narrative essay isn’t just about recounting an event – it’s about showing the impact it had on you and what you took away from it. It’s an opportunity to share your thoughts and feelings about the experience, and how it changed your outlook.

Emotional Impact

The author is trying to make the story they’re telling relatable, engaging, and memorable by using language and storytelling to evoke feelings in whoever’s reading it.

Narrative essays let writers have a blast telling stories about their own lives. It’s an opportunity to share insights and impart wisdom, or just have some fun with the reader. Descriptive language, sensory details, dialogue, and a great narrative voice are all essentials for making the story come alive.

The Purpose of a Narrative Essay

A narrative essay is more than just a story – it’s a way to share a meaningful, engaging, and relatable experience with the reader. Includes:

Sharing Personal Experience

Narrative essays are a great way for writers to share their personal experiences, feelings, thoughts, and reflections. It’s an opportunity to connect with readers and make them feel something.

Entertainment and Engagement

The essay attempts to keep the reader interested by using descriptive language, storytelling elements, and a powerful voice. It attempts to pull them in and make them feel involved by creating suspense, mystery, or an emotional connection.

Conveying a Message or Insight

Narrative essays are more than just a story – they aim to teach you something. They usually have a moral lesson, a new understanding, or a realization about life that the author gained from the experience.

Building Empathy and Understanding

By telling their stories, people can give others insight into different perspectives, feelings, and situations. Sharing these tales can create compassion in the reader and help broaden their knowledge of different life experiences.

Inspiration and Motivation

Stories about personal struggles, successes, and transformations can be really encouraging to people who are going through similar situations. It can provide them with hope and guidance, and let them know that they’re not alone.

Reflecting on Life’s Significance

These essays usually make you think about the importance of certain moments in life or the impact of certain experiences. They make you look deep within yourself and ponder on the things you learned or how you changed because of those events.

Demonstrating Writing Skills

Coming up with a gripping narrative essay takes serious writing chops, like vivid descriptions, powerful language, timing, and organization. It’s an opportunity for writers to show off their story-telling abilities.

Preserving Personal History

Sometimes narrative essays are used to record experiences and special moments that have an emotional resonance. They can be used to preserve individual memories or for future generations to look back on.

Cultural and Societal Exploration

Personal stories can look at cultural or social aspects, giving us an insight into customs, opinions, or social interactions seen through someone’s own experience.

Format of a Narrative Essay

Narrative essays are quite flexible in terms of format, which allows the writer to tell a story in a creative and compelling way. Here’s a quick breakdown of the narrative essay format, along with some examples:

Introduction

Set the scene and introduce the story.

Engage the reader and establish the tone of the narrative.

Hook: Start with a captivating opening line to grab the reader’s attention. For instance:

Example: “The scorching sun beat down on us as we trekked through the desert, our water supply dwindling.”

Background Information: Provide necessary context or background without giving away the entire story.

Example: “It was the summer of 2015 when I embarked on a life-changing journey to…”

Thesis Statement or Narrative Purpose

Present the main idea or the central message of the essay.

Offer a glimpse of what the reader can expect from the narrative.

Thesis Statement: This isn’t as rigid as in other essays but can be a sentence summarizing the essence of the story.

Example: “Little did I know, that seemingly ordinary hike would teach me invaluable lessons about resilience and friendship.”

Body Paragraphs

Present the sequence of events in chronological order.

Develop characters, setting, conflict, and resolution.

Story Progression : Describe events in the order they occurred, focusing on details that evoke emotions and create vivid imagery.

Example : Detail the trek through the desert, the challenges faced, interactions with fellow hikers, and the pivotal moments.

Character Development : Introduce characters and their roles in the story. Show their emotions, thoughts, and actions.

Example : Describe how each character reacted to the dwindling water supply and supported each other through adversity.

Dialogue and Interactions : Use dialogue to bring the story to life and reveal character personalities.

Example : “Sarah handed me her last bottle of water, saying, ‘We’re in this together.'”

Reach the peak of the story, the moment of highest tension or significance.

Turning Point: Highlight the most crucial moment or realization in the narrative.

Example: “As the sun dipped below the horizon and hope seemed lost, a distant sound caught our attention—the rescue team’s helicopters.”

Provide closure to the story.

Reflect on the significance of the experience and its impact.

Reflection : Summarize the key lessons learned or insights gained from the experience.

Example : “That hike taught me the true meaning of resilience and the invaluable support of friendship in challenging times.”

Closing Thought : End with a memorable line that reinforces the narrative’s message or leaves a lasting impression.

Example : “As we boarded the helicopters, I knew this adventure would forever be etched in my heart.”

Example Summary:

Imagine a narrative about surviving a challenging hike through the desert, emphasizing the bonds formed and lessons learned. The narrative essay structure might look like starting with an engaging scene, narrating the hardships faced, showcasing the characters’ resilience, and culminating in a powerful realization about friendship and endurance.

Different Types of Narrative Essays

There are a bunch of different types of narrative essays – each one focuses on different elements of storytelling and has its own purpose. Here’s a breakdown of the narrative essay types and what they mean.

Personal Narrative

Description : Tells a personal story or experience from the writer’s life.

Purpose: Reflects on personal growth, lessons learned, or significant moments.

Example of Narrative Essay Types:

Topic : “The Day I Conquered My Fear of Public Speaking”

Focus: Details the experience, emotions, and eventual triumph over a fear of public speaking during a pivotal event.

Descriptive Narrative

Description : Emphasizes vivid details and sensory imagery.

Purpose : Creates a sensory experience, painting a vivid picture for the reader.

Topic : “A Walk Through the Enchanted Forest”

Focus : Paints a detailed picture of the sights, sounds, smells, and feelings experienced during a walk through a mystical forest.

Autobiographical Narrative

Description: Chronicles significant events or moments from the writer’s life.

Purpose: Provides insights into the writer’s life, experiences, and growth.

Topic: “Lessons from My Childhood: How My Grandmother Shaped Who I Am”

Focus: Explores pivotal moments and lessons learned from interactions with a significant family member.

Experiential Narrative

Description: Relays experiences beyond the writer’s personal life.

Purpose: Shares experiences, travels, or events from a broader perspective.

Topic: “Volunteering in a Remote Village: A Journey of Empathy”

Focus: Chronicles the writer’s volunteering experience, highlighting interactions with a community and personal growth.

Literary Narrative

Description: Incorporates literary elements like symbolism, allegory, or thematic explorations.

Purpose: Uses storytelling for deeper explorations of themes or concepts.

Topic: “The Symbolism of the Red Door: A Journey Through Change”

Focus: Uses a red door as a symbol, exploring its significance in the narrator’s life and the theme of transition.

Historical Narrative

Description: Recounts historical events or periods through a personal lens.

Purpose: Presents history through personal experiences or perspectives.

Topic: “A Grandfather’s Tales: Living Through the Great Depression”

Focus: Shares personal stories from a family member who lived through a historical era, offering insights into that period.

Digital or Multimedia Narrative

Description: Incorporates multimedia elements like images, videos, or audio to tell a story.

Purpose: Explores storytelling through various digital platforms or formats.

Topic: “A Travel Diary: Exploring Europe Through Vlogs”

Focus: Combines video clips, photos, and personal narration to document a travel experience.

How to Choose a Topic for Your Narrative Essay?

Selecting a compelling topic for your narrative essay is crucial as it sets the stage for your storytelling. Choosing a boring topic is one of the narrative essay mistakes to avoid . Here’s a detailed guide on how to choose the right topic:

Reflect on Personal Experiences

- Significant Moments:

Moments that had a profound impact on your life or shaped your perspective.

Example: A moment of triumph, overcoming a fear, a life-changing decision, or an unforgettable experience.

- Emotional Resonance:

Events that evoke strong emotions or feelings.

Example: Joy, fear, sadness, excitement, or moments of realization.

- Lessons Learned:

Experiences that taught you valuable lessons or brought about personal growth.

Example: Challenges that led to personal development, shifts in mindset, or newfound insights.

Explore Unique Perspectives

- Uncommon Experiences:

Unique or unconventional experiences that might captivate the reader’s interest.

Example: Unusual travels, interactions with different cultures, or uncommon hobbies.

- Different Points of View:

Stories from others’ perspectives that impacted you deeply.

Example: A family member’s story, a friend’s experience, or a historical event from a personal lens.

Focus on Specific Themes or Concepts

- Themes or Concepts of Interest:

Themes or ideas you want to explore through storytelling.

Example: Friendship, resilience, identity, cultural diversity, or personal transformation.

- Symbolism or Metaphor:

Using symbols or metaphors as the core of your narrative.

Example: Exploring the symbolism of an object or a place in relation to a broader theme.

Consider Your Audience and Purpose

- Relevance to Your Audience:

Topics that resonate with your audience’s interests or experiences.

Example: Choose a relatable theme or experience that your readers might connect with emotionally.

- Impact or Message:

What message or insight do you want to convey through your story?

Example: Choose a topic that aligns with the message or lesson you aim to impart to your readers.

Brainstorm and Evaluate Ideas

- Free Writing or Mind Mapping:

Process: Write down all potential ideas without filtering. Mind maps or free-writing exercises can help generate diverse ideas.

- Evaluate Feasibility:

The depth of the story, the availability of vivid details, and your personal connection to the topic.

Imagine you’re considering topics for a narrative essay. You reflect on your experiences and decide to explore the topic of “Overcoming Stage Fright: How a School Play Changed My Perspective.” This topic resonates because it involves a significant challenge you faced and the personal growth it brought about.

Narrative Essay Topics

50 easy narrative essay topics.

- Learning to Ride a Bike

- My First Day of School

- A Surprise Birthday Party

- The Day I Got Lost

- Visiting a Haunted House

- An Encounter with a Wild Animal

- My Favorite Childhood Toy

- The Best Vacation I Ever Had

- An Unforgettable Family Gathering

- Conquering a Fear of Heights

- A Special Gift I Received

- Moving to a New City

- The Most Memorable Meal

- Getting Caught in a Rainstorm

- An Act of Kindness I Witnessed

- The First Time I Cooked a Meal

- My Experience with a New Hobby

- The Day I Met My Best Friend

- A Hike in the Mountains

- Learning a New Language

- An Embarrassing Moment

- Dealing with a Bully

- My First Job Interview

- A Sporting Event I Attended

- The Scariest Dream I Had

- Helping a Stranger

- The Joy of Achieving a Goal

- A Road Trip Adventure

- Overcoming a Personal Challenge

- The Significance of a Family Tradition

- An Unusual Pet I Owned

- A Misunderstanding with a Friend

- Exploring an Abandoned Building

- My Favorite Book and Why

- The Impact of a Role Model

- A Cultural Celebration I Participated In

- A Valuable Lesson from a Teacher

- A Trip to the Zoo

- An Unplanned Adventure

- Volunteering Experience

- A Moment of Forgiveness

- A Decision I Regretted

- A Special Talent I Have

- The Importance of Family Traditions

- The Thrill of Performing on Stage

- A Moment of Sudden Inspiration

- The Meaning of Home

- Learning to Play a Musical Instrument

- A Childhood Memory at the Park

- Witnessing a Beautiful Sunset

Narrative Essay Topics for College Students

- Discovering a New Passion

- Overcoming Academic Challenges

- Navigating Cultural Differences

- Embracing Independence: Moving Away from Home

- Exploring Career Aspirations

- Coping with Stress in College

- The Impact of a Mentor in My Life

- Balancing Work and Studies

- Facing a Fear of Public Speaking

- Exploring a Semester Abroad

- The Evolution of My Study Habits

- Volunteering Experience That Changed My Perspective

- The Role of Technology in Education

- Finding Balance: Social Life vs. Academics

- Learning a New Skill Outside the Classroom

- Reflecting on Freshman Year Challenges

- The Joys and Struggles of Group Projects

- My Experience with Internship or Work Placement

- Challenges of Time Management in College

- Redefining Success Beyond Grades

- The Influence of Literature on My Thinking

- The Impact of Social Media on College Life

- Overcoming Procrastination

- Lessons from a Leadership Role

- Exploring Diversity on Campus

- Exploring Passion for Environmental Conservation

- An Eye-Opening Course That Changed My Perspective

- Living with Roommates: Challenges and Lessons

- The Significance of Extracurricular Activities

- The Influence of a Professor on My Academic Journey

- Discussing Mental Health in College

- The Evolution of My Career Goals

- Confronting Personal Biases Through Education

- The Experience of Attending a Conference or Symposium

- Challenges Faced by Non-Native English Speakers in College

- The Impact of Traveling During Breaks

- Exploring Identity: Cultural or Personal

- The Impact of Music or Art on My Life

- Addressing Diversity in the Classroom

- Exploring Entrepreneurial Ambitions

- My Experience with Research Projects

- Overcoming Impostor Syndrome in College

- The Importance of Networking in College

- Finding Resilience During Tough Times

- The Impact of Global Issues on Local Perspectives

- The Influence of Family Expectations on Education

- Lessons from a Part-Time Job

- Exploring the College Sports Culture

- The Role of Technology in Modern Education

- The Journey of Self-Discovery Through Education

Narrative Essay Comparison

Narrative essay vs. descriptive essay.

Here’s our first narrative essay comparison! While both narrative and descriptive essays focus on vividly portraying a subject or an event, they differ in their primary objectives and approaches. Now, let’s delve into the nuances of comparison on narrative essays.

Narrative Essay:

Storytelling: Focuses on narrating a personal experience or event.

Chronological Order: Follows a structured timeline of events to tell a story.

Message or Lesson: Often includes a central message, moral, or lesson learned from the experience.

Engagement: Aims to captivate the reader through a compelling storyline and character development.

First-Person Perspective: Typically narrated from the writer’s point of view, using “I” and expressing personal emotions and thoughts.

Plot Development: Emphasizes a plot with a beginning, middle, climax, and resolution.

Character Development: Focuses on describing characters, their interactions, emotions, and growth.

Conflict or Challenge: Usually involves a central conflict or challenge that drives the narrative forward.

Dialogue: Incorporates conversations to bring characters and their interactions to life.

Reflection: Concludes with reflection or insight gained from the experience.

Descriptive Essay:

Vivid Description: Aims to vividly depict a person, place, object, or event.

Imagery and Details: Focuses on sensory details to create a vivid image in the reader’s mind.

Emotion through Description: Uses descriptive language to evoke emotions and engage the reader’s senses.

Painting a Picture: Creates a sensory-rich description allowing the reader to visualize the subject.

Imagery and Sensory Details: Focuses on providing rich sensory descriptions, using vivid language and adjectives.

Point of Focus: Concentrates on describing a specific subject or scene in detail.

Spatial Organization: Often employs spatial organization to describe from one area or aspect to another.

Objective Observations: Typically avoids the use of personal opinions or emotions; instead, the focus remains on providing a detailed and objective description.

Comparison:

Focus: Narrative essays emphasize storytelling, while descriptive essays focus on vividly describing a subject or scene.

Perspective: Narrative essays are often written from a first-person perspective, while descriptive essays may use a more objective viewpoint.

Purpose: Narrative essays aim to convey a message or lesson through a story, while descriptive essays aim to paint a detailed picture for the reader without necessarily conveying a specific message.

Narrative Essay vs. Argumentative Essay

The narrative essay and the argumentative essay serve distinct purposes and employ different approaches:

Engagement and Emotion: Aims to captivate the reader through a compelling story.

Reflective: Often includes reflection on the significance of the experience or lessons learned.

First-Person Perspective: Typically narrated from the writer’s point of view, sharing personal emotions and thoughts.

Plot Development: Emphasizes a storyline with a beginning, middle, climax, and resolution.

Message or Lesson: Conveys a central message, moral, or insight derived from the experience.

Argumentative Essay:

Persuasion and Argumentation: Aims to persuade the reader to adopt the writer’s viewpoint on a specific topic.

Logical Reasoning: Presents evidence, facts, and reasoning to support a particular argument or stance.

Debate and Counterarguments: Acknowledge opposing views and counter them with evidence and reasoning.

Thesis Statement: Includes a clear thesis statement that outlines the writer’s position on the topic.

Thesis and Evidence: Starts with a strong thesis statement and supports it with factual evidence, statistics, expert opinions, or logical reasoning.

Counterarguments: Addresses opposing viewpoints and provides rebuttals with evidence.

Logical Structure: Follows a logical structure with an introduction, body paragraphs presenting arguments and evidence, and a conclusion reaffirming the thesis.

Formal Language: Uses formal language and avoids personal anecdotes or emotional appeals.

Objective: Argumentative essays focus on presenting a logical argument supported by evidence, while narrative essays prioritize storytelling and personal reflection.

Purpose: Argumentative essays aim to persuade and convince the reader of a particular viewpoint, while narrative essays aim to engage, entertain, and share personal experiences.

Structure: Narrative essays follow a storytelling structure with character development and plot, while argumentative essays follow a more formal, structured approach with logical arguments and evidence.

In essence, while both essays involve writing and presenting information, the narrative essay focuses on sharing a personal experience, whereas the argumentative essay aims to persuade the audience by presenting a well-supported argument.

Narrative Essay vs. Personal Essay

While there can be an overlap between narrative and personal essays, they have distinctive characteristics:

Storytelling: Emphasizes recounting a specific experience or event in a structured narrative form.

Engagement through Story: Aims to engage the reader through a compelling story with characters, plot, and a central theme or message.

Reflective: Often includes reflection on the significance of the experience and the lessons learned.

First-Person Perspective: Typically narrated from the writer’s viewpoint, expressing personal emotions and thoughts.

Plot Development: Focuses on developing a storyline with a clear beginning, middle, climax, and resolution.

Character Development: Includes descriptions of characters, their interactions, emotions, and growth.

Central Message: Conveys a central message, moral, or insight derived from the experience.

Personal Essay:

Exploration of Ideas or Themes: Explores personal ideas, opinions, or reflections on a particular topic or subject.

Expression of Thoughts and Opinions: Expresses the writer’s thoughts, feelings, and perspectives on a specific subject matter.

Reflection and Introspection: Often involves self-reflection and introspection on personal experiences, beliefs, or values.

Varied Structure and Content: Can encompass various forms, including memoirs, personal anecdotes, or reflections on life experiences.

Flexibility in Structure: Allows for diverse structures and forms based on the writer’s intent, which could be narrative-like or more reflective.

Theme-Centric Writing: Focuses on exploring a central theme or idea, with personal anecdotes or experiences supporting and illustrating the theme.

Expressive Language: Utilizes descriptive and expressive language to convey personal perspectives, emotions, and opinions.

Focus: Narrative essays primarily focus on storytelling through a structured narrative, while personal essays encompass a broader range of personal expression, which can include storytelling but isn’t limited to it.

Structure: Narrative essays have a more structured plot development with characters and a clear sequence of events, while personal essays might adopt various structures, focusing more on personal reflection, ideas, or themes.

Intent: While both involve personal experiences, narrative essays emphasize telling a story with a message or lesson learned, while personal essays aim to explore personal thoughts, feelings, or opinions on a broader range of topics or themes.

A narrative essay is more than just telling a story. It’s also meant to engage the reader, get them thinking, and leave a lasting impact. Whether it’s to amuse, motivate, teach, or reflect, these essays are a great way to communicate with your audience. This interesting narrative essay guide was all about letting you understand the narrative essay, its importance, and how can you write one.

Order Original Papers & Essays

Your First Custom Paper Sample is on Us!

Timely Deliveries

No Plagiarism & AI

100% Refund

Try Our Free Paper Writing Service

Related blogs.

Connections with Writers and support

Privacy and Confidentiality Guarantee

Average Quality Score

- Literary Terms

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Write a Plot

I. What is Plot?

In a narrative or creative writing, a plot is the sequence of events that make up a story, whether it’s told, written, filmed, or sung. The plot is the story, and more specifically, how the story develops, unfolds, and moves in time. Plots are typically made up of five main elements:

1. Exposition: At the beginning of the story, characters , setting, and the main conflict are typically introduced.

2. Rising Action: The main character is in crisis and events leading up to facing the conflict begin to unfold. The story becomes complicated.

3. Climax: At the peak of the story, a major event occurs in which the main character faces a major enemy, fear, challenge, or other source of conflict. The most action, drama, change, and excitement occurs here.

4. Falling Action: The story begins to slow down and work towards its end, tying up loose ends.

5. Resolution/ Denoument: Also known as the denouement, the resolution is like a concluding paragraph that resolves any remaining issues and ends the story.

Plots, also known as storylines, include the most significant events of the story and how the characters and their problems change over time.

II. Examples of Plot

Here are a few very short stories with sample plots:

Kaitlin wants to buy a puppy. She goes to the pound and begins looking through the cages for her future pet. At the end of the hallway, she sees a small, sweet brown dog with a white spot on its nose. At that instant, she knows she wants to adopt him. After he receives shots and a medical check, she and the dog, Berkley, go home together.

In this example, the exposition introduces us to Kaitlin and her conflict. She wants a puppy but does not have one. The rising action occurs as she enters the pound and begins looking. The climax is when she sees the dog of her dreams and decides to adopt him. The falling action consists of a quick medical check before the resolution, or ending, when Kaitlin and Berkley happily head home.

Scott wants to be on the football team, but he’s worried he won’t make the team. He spends weeks working out as hard as possible, preparing for try outs. At try outs, he amazes coaches with his skill as a quarterback. They ask him to be their starting quarterback that year and give him a jersey. Scott leaves the field, ecstatic!

The exposition introduces Scott and his conflict: he wants to be on the team but he doubts his ability to make it. The rising action consists of his training and tryout; the climax occurs when the coaches tell him he’s been chosen to be quarterback. The falling action is when Scott takes a jersey and the resolution is him leaving the try-outs as a new, happy quarterback.

Each of these stories has

- an exposition as characters and conflicts are introduced

- a rising action which brings the character to the climax as conflicts are developed and faced, and

- a falling action and resolution as the story concludes.

III. Types of Plot

There are many types of plots in the world! But, realistically, most of them fit some pattern that we can see in more than one story. Here are some classic plots that can be seen in numerous stories all over the world and throughout history.

a. Overcoming the Monster

The protagonist must defeat a monster or force in order to save some people—usually everybody! Most often, the protagonist is forced into this conflict, and comes out of it as a hero, or even a king. This is one version of the world’s most universal and compelling plot—the ‘monomyth’ described by the great thinker Joseph Campbell.

Examples:

Beowulf, Harry Potter, and Star Wars.

b. Rags to Riches:

This story can begin with the protagonist being poor or rich, but at some point, the protagonist will have everything, lose everything, and then gain it all back by the end of the story, after experiencing great personal growth.

The Count of Monte Cristo, Cinderella, and Jane Eyre.

c. The Quest:

The protagonist embarks on a quest involving travel and dangerous adventures in order to find treasure or solve a huge problem. Usually, the protagonist is forced to begin the quest but makes friends that help face the many tests and obstacles along the way. This is also a version of Campbell’s monomyth.

The Iliad, The Lord of the Rings, and Eragon

d. Voyage and Return:

The protagonist goes on a journey to a strange or unknown place, facing danger and adventures along the way, returning home with experience and understanding. This is also a version of the monomyth.

Alice in Wonderland, The Chronicles of Narnia, and The Wizard of Oz

A happy and fun character finds a happy ending after triumphing over difficulties and adversities.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Fantastic Mr. Fox, Home Alone

f. Tragedy:

The protagonist experiences a conflict which leads to very bad ending, typically death.

Romeo and Juliet, The Picture of Dorian Gray, and Macbeth

g. Rebirth:

The protagonist is a villain who becomes a good person through the experience of the story’s conflict.

The Secret Garden, A Christmas Carol, The Grinch

As these seven examples show, many stories follow a common pattern. In fact, according to many thinkers, such as the great novelist Kurt Vonnegut, and Joseph Campbell, there are only a few basic patterns, which are mixed and combined to form all stories.

IV. The Importance of Using Plot

The plot is what makes a story a story. It gives the story character development, suspense, energy, and emotional release (also known as ‘catharsis’). It allows an author to develop themes and most importantly, conflict that makes a story emotionally engaging; everybody knows how hard it is to stop watching a movie before the conflict is resolved.

V. Examples of Plot in Literature

Plots can be found in all kinds of fiction. Here are a few examples.

The Razor’s Edge by Somerset Maugham

In The Razor’s Edge, Larry Darrell returns from World War I disillusioned. His fiancée, friends, and family urge him to find work, but he does not want to. He embarks on a voyage through Europe and Asia seeking higher truth. Finally, in Asia, he finds a more meaningful way of life.

In this novel, the plot follows the protagonist Larry as he seeks meaningful experiences. The story begins with the exposition of a disillusioned young man who does not want to work. The rising action occurs as he travels seeking an education. The story climaxes when he becomes a man perfectly at peace in meditation.

The Road not Taken’ by Robert Frost

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood, And sorry I could not travel both And be one traveler, long I stood And looked down one as far as I could … Then took the other, as just as fair, And having perhaps the better claim … And both that morning equally lay In leaves no step had trodden black. … I shall be telling this with a sigh Somewhere ages and ages hence: Two roads diverged in a wood, and I, I took the one less traveled by, And that has made all the difference.

Robert Frost’s famous poem “The Road Not Taken,” has a very clear plot: The exposition occurs when a man stands at the fork of two roads, his conflict being which road to take. The climax occurs when he chooses the unique path. The resolution announces that “that has made all the difference,” meaning the man has made a significant and meaningful decision.

VI. Examples of Plot in Pop Culture

Plots can also be found in television shows, movies, thoughtful storytelling advertisements, and song lyrics. Below are a few examples of plot in pop culture.

“Love Story” (excerpts) by Taylor Swift:

I’m standing there on a balcony in summer air. See the lights, see the party, the ball gowns. See you make your way through the crowd And say, “Hello, ” Little did I know… That you were Romeo, you were throwing pebbles, And my daddy said, “Stay away from Juliet” And I was crying on the staircase Begging you, “Please don’t go” So I sneak out to the garden to see you. We keep quiet ’cause we’re dead if they knew So close your eyes… escape this town for a little while. . . . He knelts to the ground and pulled out a ring and said… “Marry me, Juliet, you’ll never have to be alone. I love you, and that’s all I really know. I talked to your dad – go pick out a white dress It’s a love story, baby, just say, ‘Yes.'”

These excerpts reveal the plot of this song: the exposition occurs when we see two characters: a young woman and young man falling in love. The rising action occurs as the father forbids her from seeing the man and they continue see one another in secret. Finally, the climax occurs when the young man asks her to marry him and the two agree to make their love story come true.

Minions have a goal to serve the most despicable master. Their rising action is their search for the best leader, the conflict being that they cannot keep one. Movie trailers encourage viewers to see the movie by showing the conflict but not the climax or resolution.

VII. Related Terms

Many people use outlines which to create complex plots, or arguments in formal essays . In a story, an outline is a list of the scenes in the plot with brief descriptions. Like the skeleton is to the body, an outline is the framework upon which the rest of the story is built when it is written. In essays, outlines are used to help organize ideas into strong arguments and paragraphs that connect to each other in sensible ways.

The climax is considered the most important element of the plot. It contains the highest point of tension, drama, and change. The climax is when the conflict is finally faced and overcome. Without a climax, a plot does not exist.

For example, consider this simple plot:

The good army is about to face the evil army in a terrible battle. During this battle, the good army prevails and wins the war at last. After the war has ended, the two sides make piece and begin rebuilding the countryside which was ruined by the years-long war.

The climax occurred when the good army defeated the bad army. Without this climax, the story would simply be a never-ending war between a good army and bad army, with no happy or sad ending in sight. Here, the climax is absolutely necessary for a meaningful story with a clear ending.

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Autobiography

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Point of View

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Device

- Rhetorical Question

- Science Fiction

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

Essay Papers Writing Online

A complete guide to writing captivating and engaging narrative essays that will leave your readers hooked.

When it comes to storytelling, the ability to captivate your audience is paramount. Creating a narrative essay that holds the reader’s attention requires finesse and creativity. A well-crafted story is not merely a sequence of events; it should transport the reader to another time and place, evoking emotions and leaving a lasting impression. Crafting a compelling narrative essay requires careful consideration of the elements that make a story interesting and engaging.

Dive into the depths of your imagination and unleash your creativity to give life to your narrative. The key to an engaging story lies in your ability to paint vivid images with your words. Strong sensory details and descriptive language allow readers to visualize the scenes and connect with the story on a deeper level. Engage the senses of sight, sound, taste, touch, and smell to take your readers on a sensory journey through your narrative.

In addition to capturing the reader’s imagination, establish a relatable protagonist to anchor your story. Your main character should be someone your readers can empathize with, someone they can root for. By creating a three-dimensional character with relatable qualities, you invite the reader to become emotionally invested in the narrative. Develop a character with flaws, desires, and a clear motivation for their actions. This will add depth and complexity to your story as your protagonist navigates through challenges and evolves.

Choose a captivating topic that resonates with your audience

When it comes to writing a narrative essay, one of the most important factors in capturing your audience’s attention is selecting a captivating topic. A captivating topic will resonate with your readers and draw them into your story, making them eager to read on and discover more.

Choosing a topic that resonates with your audience means selecting a subject that they can relate to or find interesting. It’s essential to consider the interests, experiences, and emotions of your target audience when deciding on a topic. Think about what will grab their attention and keep them engaged throughout your essay.

One way to choose a captivating topic is by drawing from personal experiences. Reflect on significant events or moments in your life that have had a lasting impact on you. These experiences can provide the basis for a compelling narrative, as they often resonate with others who have gone through similar situations.

Another approach is to explore topics that are relevant or timely. Think about current events or social issues that are capturing public attention. By addressing these topics in your narrative essay, you can tap into the existing interest and engage readers who are already invested in the subject matter.

Additionally, consider incorporating elements of surprise or intrigue into your chosen topic. This could involve telling a story with an unexpected twist or focusing on an unusual or lesser-known aspect of a familiar subject. By presenting something unexpected or unique, you can pique your audience’s curiosity and make them eager to discover what happens next.

In summary, selecting a captivating topic is crucial for creating a compelling narrative essay. By choosing a subject that resonates with your audience, drawing from personal experiences, addressing relevant topics, and incorporating elements of surprise, you can capture and hold your readers’ attention, ensuring that they stay engaged throughout your story.

Develop well-rounded characters to drive your narrative

In order to create a captivating story, it is essential to develop well-rounded characters that will drive your narrative forward. These characters should be multi-dimensional and relatable, with their own unique personalities, motivations, and struggles. By doing so, you will not only make your readers more invested in your story, but also add depth and complexity to your narrative.

When developing your characters, it is important to consider their backgrounds, experiences, and beliefs. A character’s past experiences can shape their actions and decision-making throughout the story, while their beliefs can provide insight into their values and worldview. By delving into these aspects, you can create characters that feel authentic and true to life.

Furthermore, it is crucial to give your characters goals and motivations that propel them forward in the narrative. These goals can be internal or external, and can range from a desire for love and acceptance to a quest for power or revenge. By giving your characters something to strive for, you create tension and conflict that drives the plot.

In addition to goals and motivations, it is important to give your characters flaws and weaknesses. No one is perfect, and by acknowledging this, you create characters that are more relatable and human. Flaws can also create obstacles and challenges for your characters to overcome, adding depth and complexity to your story.

Lastly, remember to show, rather than tell, your readers about your characters. Instead of explicitly stating their traits and qualities, let their actions, dialogue, and interactions with other characters reveal who they are. This will allow your readers to form their own connections with the characters and become more engaged with your narrative.

By taking the time to develop well-rounded characters with unique personalities, motivations, and flaws, you will create a narrative that is not only compelling, but also resonates with your readers on a deeper level. So, dive into the minds and hearts of your characters, and let them drive your story to new heights.

Create a clear and engaging plot with a strong conflict

In order to craft a captivating narrative essay, it is essential to develop a plot that is both coherent and captivating. The plot serves as the foundation of your story, providing the framework that will guide your readers through a series of events and actions. To create an engaging plot, it is crucial to introduce a strong conflict that will propel the story forward and keep your readers hooked from start to finish.

The conflict is the driving force that creates tension and suspense in your narrative. It presents the main obstacle or challenge that your protagonist must overcome, creating a sense of urgency and keeping your readers invested in the outcome. Without a strong conflict, your story may lack direction and fail to hold your readers’ interest.

When developing your plot, consider the various elements that can contribute to a compelling conflict. This could be a clash between characters, a struggle against nature or society, or a battle within oneself. The conflict should be meaningful and have significant stakes for your protagonist, pushing them to make difficult choices and undergo personal growth.

To ensure that your plot remains clear and engaging, it is important to establish a logical progression of events. Each scene and action should contribute to the overall development of the conflict and the resolution of the story. Avoid unnecessary detours or subplots that do not advance the main conflict, as they can distract from the core narrative and confuse your readers.

In addition to a strong conflict, a clear and engaging plot also requires well-developed characters that your readers can root for and relate to. The actions and decisions of your characters should be motivated by their personalities, desires, and beliefs, adding depth and complexity to the narrative. By creating multidimensional characters, you can further enhance the conflict and make it more compelling.