Declaration of Independence

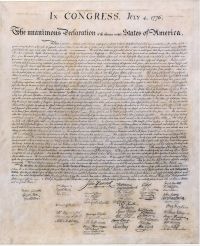

The Declaration of Independence is the foundational document of the United States of America. Written primarily by Thomas Jefferson, it explains why the Thirteen Colonies decided to separate from Great Britain during the American Revolution (1765-1789). It was adopted by the Second Continental Congress on 4 July 1776, the anniversary of which is celebrated in the US as Independence Day.

The Declaration was not considered a significant document until more than 50 years after its signing, as it was initially seen as a routine formality to accompany Congress' vote for independence. However, it has since become appreciated as one of the most important human rights documents in Western history. Largely influenced by Enlightenment ideals, particularly those of John Locke , the Declaration asserts that "all men are created equal" and are endowed with the "certain unalienable rights" to "Life, Liberty and the pursuit of happiness"; this has become one of the best-known statements in US history and has become a moral standard that the United States, and many other Western democracies, have since strived for. It has been cited in the push for the abolition of slavery and in many civil rights movements, and it continues to be a rallying cry for human rights to this day. Alongside the Articles of Confederation and the US Constitution, the Declaration of Independence was one of the most important documents to come out of the American Revolutionary era. This article includes a brief history of the factors that led the colonies to declare independence from Britain, as well as the complete text of the Declaration itself.

Road to Independence

For much of the early part of their struggle with Great Britain, most American colonists regarded independence as a final resort, if they even considered it at all. The argument between the colonists and the British Parliament, after all, largely boiled down to colonial identity within the British Empire ; the colonists believed that, as subjects of the British king and descendants of Englishmen, they were entitled to the same constitutional rights that governed the lives of those still in England . These rights, as expressed in the Magna Carta (1215), the Habeas Corpus Act of 1679, and the Bill of Rights of 1689, among other documents, were interpreted by the Americans to include self-taxation, representative government, and trial by jury. Englishmen exercised these rights through Parliament, which, at least theoretically, represented their interests; since the colonists were not represented in Parliament, they attempted to exercise their own 'rights of Englishmen' through colonial legislative assemblies such as Virginia's House of Burgesses .

Parliament, however, saw things differently. It agreed that the colonists were Britons and were subject to the same laws, but it viewed the colonists as no different than the 90% of Englishmen who owned no land and therefore could not vote, but who were nevertheless virtually represented in Parliament. Under this pretext, Parliament decided to directly tax the colonies and passed the Stamp Act in 1765. When the Americans protested that Parliament had no authority to tax them because they were not represented in Parliament, Parliament responded by passing the Declaratory Act (1766), wherein it proclaimed that it had the authority to pass binding legislation for all Britain's colonies "in all Cases whatsoever" (Middlekauff, 118). After doubling down, Parliament taxed the Americans once again with the Townshend Acts (1767-68). When these acts were met with riots in Boston, Parliament sent regiments of soldiers to restore the king's peace. This only led to acts of violence such as the Boston Massacre (5 March 1770) and acts of disobedience such as the Boston Tea Party (16 December 1773).

While the focal point of the argument regarded taxation, the Americans believed that their rights were being violated in other ways as well. As mandated in the so-called Intolerable Acts of 1774, Britain announced that American dissidents would now be tried by Vice-Admiralty courts or shipped to England for trial, thereby depriving them of a jury of peers; British soldiers could be quartered in American-owned buildings; and Massachusetts' representative government was to be suspended as punishment for the Boston Tea Party, with a military governor to be installed. Additionally, there was the question of land; both the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and the Quebec Act of 1774 restricted the westward expansion of Americans, who believed they were entitled to settle the West. While the colonies viewed themselves as separate polities within the British Empire and would not view themselves as a single entity for many years to come, they had nevertheless become bound together over the years due to their shared Anglo background and through their military cooperation during the last century of colonial wars with France. Their resistance to Parliament only tied them closer together and, after the passage of the Intolerable Acts, the colonies announced support for Massachusetts and began mobilizing their militias.

When the American Revolutionary War broke out in 1775, all thirteen colonies soon joined the rebellion and sent representatives to the Second Continental Congress, a provisional wartime government. Even at this late stage, independence was an idea espoused by only the most radical revolutionaries like Samuel Adams . Most colonists still believed that their quarrel was with Parliament alone, that King George III of Great Britain (r. 1760-1820) secretly supported them and would reconcile with them if given the opportunity; indeed, just before the Battle of Bunker Hill (17 June 1775), regiments of American rebels reported for duty by announcing that they were "in his Majesty's service" (Boatner, 539). In August 1775, King George III dispelled such notions when he issued his Proclamation of Rebellion, in which he announced that he considered the colonies to be in a state of rebellion and ordered British officials to endeavor to "withstand and suppress such rebellion". Indeed, George III would remain one of the biggest advocates of subduing the colonies with military force; it was after this moment that Americans began referring to him as a tyrant and hope of reconciliation with Britain diminished.

Writing the Declaration

By the spring of 1776, independence was no longer a radical idea; Thomas Paine 's widely circulated pamphlet Common Sense had made the prospect more appealing to the general public, while the Continental Congress realized that independence was necessary to procure military support from European nations. In March 1776, the revolutionary convention of North Carolina became the first to vote in favor of independence, followed by seven other colonies over the next two months. On 7 June, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia introduced a motion putting the idea of independence before Congress; the motion was so fiercely debated that Congress decided to postpone further discussion of Lee's motion for three weeks. In the meantime, a committee was appointed to draft a Declaration of Independence, in the event that Lee's motion passed. This five-man committee was comprised of Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Robert R. Livingston of New York, John Adams of Massachusetts, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, and Thomas Jefferson of Virginia.

The Declaration was primarily authored by the 33-year-old Jefferson, who wrote it between 11 June and 28 June 1776 on the second floor of the Philadelphia home he was renting, now known as the Declaration House. Drawing heavily on the Enlightenment ideas of John Locke, Jefferson places the blame for American independence largely at the feet of the king, whom he accuses of having repeatedly violated the social contract between America and Great Britain. The Americans were declaring their independence, Jefferson asserts, only as a last resort to preserve their rights, having been continually denied redress by both the king and Parliament. Jefferson's original draft was revised and edited by the other men on the committee, and the Declaration was finally put before Congress on 1 July. By then, every colony except New York had authorized its congressional delegates to vote for independence, and on 4 July 1776, the Congress adopted the Declaration. It was signed by all 56 members of Congress; those who were not present on the day itself affixed their signatures later.

The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America. When in the course of human events it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to separation. Remove Ads Advertisement We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness. – That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, – That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive toward these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such a form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and, accordingly, all experience hath shewn that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security. – Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world. He has refused to Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good. He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them. Remove Ads Advertisement He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only. He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their Public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures. He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people. He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the Legislative Powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within. Love History? Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter! He has endeavored to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws of Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands. He has obstructed the Administration of Justice by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary Powers. He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries. He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harass our people and eat out their substance. He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures. He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil Power. He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation: For quartering large bodies of armed troops among us: For protecting them, by a mock Trial from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States: For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world: For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent: For depriving us in many cases, of the benefit of Trial by Jury: For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences: For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rules into these Colonies For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments: For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever. He has abdicated Government here, be declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us. He has plundered our seas, ravaged our coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people. He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death , desolation, and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty and Perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation. He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands. He has excited domestic insurrections against us, and has endeavored to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages whose known rule of warfare , is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes, and conditions. In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince, whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people. Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our British brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the ties of our common kindred to disavow these usurpations, which would inevitably interrupt our connections and correspondence. They too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends. We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by the Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these united Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States, that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. – And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of Divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor.

The following is a list of the 56 men who signed the Declaration of Independence, many of whom are considered the Founding Fathers of the United States. John Hancock , as president of the Continental Congress, was the first to affix his signature. Robert R. Livingston was the only member of the original drafting committee to not also sign the Declaration, as he had been recalled to New York before the signing took place.

Massachusetts: John Hancock, Samuel Adams, John Adams, Robert Treat Paine, Elbridge Gerry.

New Hampshire: Josiah Bartlett, William Whipple, Matthew Thornton.

Rhode Island: Stephen Hopkins , William Ellery.

Connecticut: Roger Sherman, Samuel Huntington, William Williams, Oliver Wolcott.

New York: William Floyd, Philip Livingston, Francis Lewis, Lewis Morris.

New Jersey: Richard Stockton, John Witherspoon, Francis Hopkinson, John Hart, Abraham Clark.

Pennsylvania: Robert Morris, Benjamin Rush, Benjamin Franklin, John Morton, George Clymer, James Smith, George Taylor, James Wilson, George Ross.

Delaware: George Read, Caesar Rodney, Thomas McKean.

Maryland: Samuel Chase, William Paca, Thomas Stone, Charles Carroll of Carrollton.

Virginia: George Wythe, Richard Henry Lee, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Harrison, Thomas Nelson Jr., Francis Lightfoot Lee, Carter Braxton.

North Carolina: William Hooper, Joseph Hewes, John Penn.

South Carolina: Edward Rutledge, Thomas Heyward Jr., Thomas Lynch Jr., Arthur Middleton.

Georgia: Button Gwinnett, Lyman Hall, George Walton.

Subscribe to topic Bibliography Related Content Books Cite This Work License

Bibliography

- Boatner, Mark M. Cassell's Biographical Dictionary of the American War of Independence. London: Cassell, 1973., 1973.

- Britannica: Text of the Declaration of Independence Accessed 25 Mar 2024.

- Declaration of Independence - Signed, Writer, Date | HISTORY Accessed 25 Mar 2024.

- Declaration of Independence: A Transcription | National Archives Accessed 25 Mar 2024.

- Meacham, Jon. Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power. Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2013.

- Middlekauff, Robert. The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789. Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Wood, Gordon S. The Radicalism of the American Revolution. Vintage, 1993.

About the Author

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this article into another language!

Questions & Answers

What is the declaration of independence, who wrote the declaration of independence, who signed the declaration of independence, related content.

Second Continental Congress

First Continental Congress

Natural Rights & the Enlightenment

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

The Enlightenment

Free for the world, supported by you.

World History Encyclopedia is a non-profit organization. For only $5 per month you can become a member and support our mission to engage people with cultural heritage and to improve history education worldwide.

Recommended Books

| , published by Children's Press (2008) |

| , published by CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (2016) |

| , published by Heinemann-Raintree (2012) |

| , published by Penguin Workshop (2016) |

| , published by Puffin Books (2014) |

Cite This Work

Mark, H. W. (2024, April 03). Declaration of Independence . World History Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2411/declaration-of-independence/

Chicago Style

Mark, Harrison W.. " Declaration of Independence ." World History Encyclopedia . Last modified April 03, 2024. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2411/declaration-of-independence/.

Mark, Harrison W.. " Declaration of Independence ." World History Encyclopedia . World History Encyclopedia, 03 Apr 2024. Web. 30 Jun 2024.

License & Copyright

Submitted by Harrison W. Mark , published on 03 April 2024. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike . This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 11

The declaration of independence.

- The Articles of Confederation

- The Constitution of the United States

- Frederick Douglass, "What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?"

- Letter from a Birmingham Jail

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Declaration of Independence

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 25, 2024 | Original: October 27, 2009

The Declaration of Independence was the first formal statement by a nation’s people asserting their right to choose their own government.

When armed conflict between bands of American colonists and British soldiers began in April 1775, the Americans were ostensibly fighting only for their rights as subjects of the British crown. By the following summer, with the Revolutionary War in full swing, the movement for independence from Britain had grown, and delegates of the Continental Congress were faced with a vote on the issue. In mid-June 1776, a five-man committee including Thomas Jefferson , John Adams and Benjamin Franklin was tasked with drafting a formal statement of the colonies’ intentions. The Congress formally adopted the Declaration of Independence—written largely by Jefferson—in Philadelphia on July 4 , a date now celebrated as the birth of American independence.

America Before the Declaration of Independence

Even after the initial battles in the Revolutionary War broke out, few colonists desired complete independence from Great Britain, and those who did–like John Adams– were considered radical. Things changed over the course of the next year, however, as Britain attempted to crush the rebels with all the force of its great army. In his message to Parliament in October 1775, King George III railed against the rebellious colonies and ordered the enlargement of the royal army and navy. News of his words reached America in January 1776, strengthening the radicals’ cause and leading many conservatives to abandon their hopes of reconciliation. That same month, the recent British immigrant Thomas Paine published “Common Sense,” in which he argued that independence was a “natural right” and the only possible course for the colonies; the pamphlet sold more than 150,000 copies in its first few weeks in publication.

Did you know? Most Americans did not know Thomas Jefferson was the principal author of the Declaration of Independence until the 1790s; before that, the document was seen as a collective effort by the entire Continental Congress.

In March 1776, North Carolina’s revolutionary convention became the first to vote in favor of independence; seven other colonies had followed suit by mid-May. On June 7, the Virginia delegate Richard Henry Lee introduced a motion calling for the colonies’ independence before the Continental Congress when it met at the Pennsylvania State House (later Independence Hall) in Philadelphia. Amid heated debate, Congress postponed the vote on Lee’s resolution and called a recess for several weeks. Before departing, however, the delegates also appointed a five-man committee–including Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, John Adams of Massachusetts, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania and Robert R. Livingston of New York–to draft a formal statement justifying the break with Great Britain. That document would become known as the Declaration of Independence.

Thomas Jefferson Writes the Declaration of Independence

Jefferson had earned a reputation as an eloquent voice for the patriotic cause after his 1774 publication of “A Summary View of the Rights of British America,” and he was given the task of producing a draft of what would become the Declaration of Independence. As he wrote in 1823, the other members of the committee “unanimously pressed on myself alone to undertake the draught [sic]. I consented; I drew it; but before I reported it to the committee I communicated it separately to Dr. Franklin and Mr. Adams requesting their corrections….I then wrote a fair copy, reported it to the committee, and from them, unaltered to the Congress.”

As Jefferson drafted it, the Declaration of Independence was divided into five sections, including an introduction, a preamble, a body (divided into two sections) and a conclusion. In general terms, the introduction effectively stated that seeking independence from Britain had become “necessary” for the colonies. While the body of the document outlined a list of grievances against the British crown, the preamble includes its most famous passage: “We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

The Continental Congress Votes for Independence

The Continental Congress reconvened on July 1, and the following day 12 of the 13 colonies adopted Lee’s resolution for independence. The process of consideration and revision of Jefferson’s declaration (including Adams’ and Franklin’s corrections) continued on July 3 and into the late morning of July 4, during which Congress deleted and revised some one-fifth of its text. The delegates made no changes to that key preamble, however, and the basic document remained Jefferson’s words. Congress officially adopted the Declaration of Independence later on the Fourth of July (though most historians now accept that the document was not signed until August 2).

The Declaration of Independence became a significant landmark in the history of democracy. In addition to its importance in the fate of the fledgling American nation, it also exerted a tremendous influence outside the United States, most memorably in France during the French Revolution . Together with the Constitution and the Bill of Rights , the Declaration of Independence can be counted as one of the three essential founding documents of the United States government.

HISTORY Vault

Stream thousands of hours of acclaimed series, probing documentaries and captivating specials commercial-free in HISTORY Vault

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

Declaration of Independence Causes and Effects

- Utility Menu

Text of the Declaration of Independence

Note: The source for this transcription is the first printing of the Declaration of Independence, the broadside produced by John Dunlap on the night of July 4, 1776. Nearly every printed or manuscript edition of the Declaration of Independence has slight differences in punctuation, capitalization, and even wording. To find out more about the diverse textual tradition of the Declaration, check out our Which Version is This, and Why Does it Matter? resource.

WHEN in the Course of human Events, it becomes necessary for one People to dissolve the Political Bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the Powers of the Earth, the separate and equal Station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent Respect to the Opinions of Mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the Separation. We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness—-That to secure these Rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just Powers from the Consent of the Governed, that whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these Ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its Foundation on such Principles, and organizing its Powers in such Form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient Causes; and accordingly all Experience hath shewn, that Mankind are more disposed to suffer, while Evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the Forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long Train of Abuses and Usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object, evinces a Design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their Right, it is their Duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future Security. Such has been the patient Sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the Necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The History of the present King of Great-Britain is a History of repeated Injuries and Usurpations, all having in direct Object the Establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid World. He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public Good. He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing Importance, unless suspended in their Operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them. He has refused to pass other Laws for the Accommodation of large Districts of People, unless those People would relinquish the Right of Representation in the Legislature, a Right inestimable to them, and formidable to Tyrants only. He has called together Legislative Bodies at Places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the Depository of their public Records, for the sole Purpose of fatiguing them into Compliance with his Measures. He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly Firmness his Invasions on the Rights of the People. He has refused for a long Time, after such Dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the Legislative Powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the Dangers of Invasion from without, and Convulsions within. He has endeavoured to prevent the Population of these States; for that Purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their Migrations hither, and raising the Conditions of new Appropriations of Lands. He has obstructed the Administration of Justice, by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary Powers. He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone, for the Tenure of their Offices, and the Amount and Payment of their Salaries. He has erected a Multitude of new Offices, and sent hither Swarms of Officers to harrass our People, and eat out their Substance. He has kept among us, in Times of Peace, Standing Armies, without the consent of our Legislatures. He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil Power. He has combined with others to subject us to a Jurisdiction foreign to our Constitution, and unacknowledged by our Laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation: For quartering large Bodies of Armed Troops among us: For protecting them, by a mock Trial, from Punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States: For cutting off our Trade with all Parts of the World: For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent: For depriving us, in many Cases, of the Benefits of Trial by Jury: For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended Offences: For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an arbitrary Government, and enlarging its Boundaries, so as to render it at once an Example and fit Instrument for introducing the same absolute Rule into these Colonies: For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws, and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments: For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with Power to legislate for us in all Cases whatsoever. He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us. He has plundered our Seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our Towns, and destroyed the Lives of our People. He is, at this Time, transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the Works of Death, Desolation, and Tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty and Perfidy, scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous Ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized Nation. He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the Executioners of their Friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands. He has excited domestic Insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the Inhabitants of our Frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known Rule of Warfare, is an undistinguished Destruction, of all Ages, Sexes and Conditions. In every stage of these Oppressions we have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble Terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated Injury. A Prince, whose Character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the Ruler of a free People. Nor have we been wanting in Attentions to our British Brethren. We have warned them from Time to Time of Attempts by their Legislature to extend an unwarrantable Jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the Circumstances of our Emigration and Settlement here. We have appealed to their native Justice and Magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the Ties of our common Kindred to disavow these Usurpations, which, would inevitably interrupt our Connections and Correspondence. They too have been deaf to the Voice of Justice and of Consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the Necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of Mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace, Friends. We, therefore, the Representatives of the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the World for the Rectitude of our Intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly Publish and Declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be, Free and Independent States; that they are absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political Connection between them and the State of Great-Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm Reliance on the Protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor.

Signed by Order and in Behalf of the Congress, JOHN HANCOCK, President.

Attest. CHARLES THOMSON, Secretary.

America's Founding Documents

The Declaration of Independence: What Does it Say?

Pulling down the Statue of King George III

After a public reading of the Declaration of Independence at Bowling Green, on July 9, 1776, New Yorkers pulled down the statue of King George III. Parts of the statue were reportedly melted down and used for bullets. Courtesy of Lafayette College Art Collection Easton, Pennsylvania

The Declaration of Independence was designed for multiple audiences: the King, the colonists, and the world. It was also designed to multitask. Its goals were to rally the troops, win foreign allies, and to announce the creation of a new country. The introductory sentence states the Declaration’s main purpose, to explain the colonists’ right to revolution. In other words, “to declare the causes which impel them to the separation.” Congress had to prove the legitimacy of its cause. It had just defied the most powerful nation on Earth. It needed to motivate foreign allies to join the fight.

These are the lines contemporary Americans know best: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of happiness.” These stirring words were designed to convince Americans to put their lives on the line for the cause. Separation from the mother country threatened their sense of security, economic stability, and identity. The preamble sought to inspire and unite them through the vision of a better life.

List of Grievances

The list of 27 complaints against King George III constitute the proof of the right to rebellion. Congress cast “the causes which impel them to separation” in universal terms for an international audience. Join our fight, reads the subtext, and you join humankind’s fight against tyranny.

Resolution of Independence

The most important and dramatic statement comes near the end: “That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States.” It declares a complete break with Britain and its King and claims the powers of an independent country.

Back to Main Page How did it happen?

Library of Congress

Exhibitions.

- Ask a Librarian

- Digital Collections

- Library Catalogs

- Exhibitions Home

- Current Exhibitions

- All Exhibitions

- Loan Procedures for Institutions

- Special Presentations

Declaring Independence: Drafting the Documents Essay

Drafting the Documents

Thomas Jefferson drafted the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia behind a veil of Congressionally imposed secrecy in June 1776 for a country wracked by military and political uncertainties. In anticipation of a vote for independence, the Continental Congress on June 11 appointed Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert R. Livingston as a committee to draft a declaration of independence. The committee then delegated Thomas Jefferson to undertake the task. Jefferson worked diligently in private for days to compose a document. Proof of the arduous nature of the work can be seen in the fragment of the first known composition draft of the declaration, which is on public display here for the first time.

Jefferson then made a clean or "fair" copy of the composition declaration, which became the foundation of the document, labeled by Jefferson as the "original Rough draught." Revised first by Adams, then by Franklin, and then by the full committee, a total of forty-seven alterations including the insertion of three complete paragraphs was made on the text before it was presented to Congress on June 28. After voting for independence on July 2, the Congress then continued to refine the document, making thirty-nine additional revisions to the committee draft before its final adoption on the morning of July 4. The "original Rough draught" embodies the multiplicity of corrections, additions and deletions that were made at each step. Although most of the alterations are in Jefferson's handwriting (Jefferson later indicated the changes he believed to have been made by Adams and Franklin), quite naturally he opposed many of the changes made to his document.

Congress then ordered the Declaration of Independence printed and late on July 4, John Dunlap, a Philadelphia printer, produced the first printed text of the Declaration of Independence, now known as the "Dunlap Broadside." The next day John Hancock, the president of the Continental Congress, began dispatching copies of the Declaration to America's political and military leaders. On July 9, George Washington ordered that his personal copy of the "Dunlap Broadside," sent to him by John Hancock on July 6, be read to the assembled American army at New York. In 1783 at the war's end, General Washington brought his copy of the broadside home to Mount Vernon. This remarkable document, which has come down to us only partially intact, is accompanied in this exhibit by a complete "Dunlap Broadside"—one of only twenty-four known to exist.

On July 19, Congress ordered the production of an engrossed (officially inscribed) copy of the Declaration of Independence, which attending members of the Continental Congress, including some who had not voted for its adoption, began to sign on August 2, 1776. This document is on permanent display at the National Archives.

On July 4, 1995, more than two centuries after its composition, the Declaration of Independence, just as Jefferson predicted on its fiftieth anniversary in his letter to Roger C. Weightman, towers aloft as "the signal of arousing men to burst the chains...to assume the blessings and security of self-government" and to restore "the free right to the unbounded exercise of reason and freedom of opinion."

Connect with the Library

All ways to connect

Subscribe & Comment

- RSS & E-Mail

Download & Play

- iTunesU (external link)

About | Press | Jobs | Donate Inspector General | Legal | Accessibility | External Link Disclaimer | USA.gov

In order to continue enjoying our site, we ask that you confirm your identity as a human. Thank you very much for your cooperation.

Thomas Jefferson's Monticello

- Thomas Jefferson

- Jefferson's Three Greatest Achievements

- The Declaration of Independence

The Legacy of the Declaration

An American People

In its opening lines, the Declaration made a radical statement: America was “one People." On the eve of independence, however, the thirteen colonies had been separate provinces, and colonists' loyalties were to their individual colonies and the British Empire rather than to each other. In fact, only commercial and cultural ties with Britain served to unify the colonies. Yet the Declaration helped to transform South Carolinians, Virginians, New Yorkers and other colonists into Americans.

A New System of Governance

The Declaration announced America's separation from one of the world's most powerful empires: Britain. Parliament's taxes imposed without American representation, along with King George III's failure to address or ease his subjects' grievances, made dissolving the "bands which have connected them" not just a choice, but an urgent necessity. As the Declaration made clear, the "long train of abuses and usurpations" and the tyranny exhibited "over these States" forced the colonists to "alter their former system of Government." In such circumstances, Jefferson explained that it was the people’s “right, it was their duty,” to throw off the repressive government. Under the new "system," Americans would govern themselves.

Closer to Europe

America did not secede from the British Empire to be alone in the world. Instead, the Declaration proclaimed that an independent America had assumed a "separate and equal station" with the other "powers of the earth." With this statement, America sought to occupy an equal place with other modern European nations, including France, the Dutch Republic, Spain, and even Britain. America's independence signaled a fundamental change: once-dependent British colonies became independent states that could make war, create alliances with foreign nations, and engage freely in commerce.

Equal Rights

The Declaration proclaimed a landmark principle—that "all men are created equal." Colonists had always seen themselves as equal to their British cousins and entitled to the same liberties. But when Parliament passed laws that violated colonists' "inalienable rights" and ruled the American colonies without the "consent of the governed," colonists concluded that as a colonial master Britain was the land of tyranny, not freedom. The Declaration sought to restore equal rights by rejecting Britain's oppression.

The "Spirit of 76"

The principles outlined in the Declaration of Independence promised to lead America—and other nations on the globe—into a new era of freedom. The revolution begun by Americans on July 4, 1776 would never end. It would inspire all peoples living under the burden of oppression and ignorance to open their eyes to the rights of mankind, to overturn the power of tyrants, and to declare the triumph of equality over inequality. Thomas Jefferson recognized as much, preparing a letter for the fiftieth anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration less than two weeks before his death, he expressed his belief that the Declaration

be to the world what I believe it will be, (to some parts sooner, to others later, but finally to all.) the Signal of arousing men to burst the chains, under which Monkish ignorance and superstition had persuaded them to bind themselves, and to assume the blessings & security of self government. the form which we have substituted restores the free right to the unbounded exercise of reason and freedom of opinion. all eyes are opened, or opening to the rights of man. the general spread of the light of science has already laid open to every view the palpable truth that the mass of mankind has not been born, with saddles on their backs, nor a favored few booted and spurred, ready to ride them legitimately, by the grace of god. these are grounds of hope for others. for ourselves let the annual return of this day, for ever refresh our recollections of these rights and an undiminished devotion to them. --Thomas Jefferson to Roger Chew Weightman, June 24, 1826.

ADDRESS: 931 Thomas Jefferson Parkway Charlottesville, VA 22902 GENERAL INFORMATION: (434) 984-9800

Thomas Jefferson and the Declaration of Independence

Written by: bill of rights institute, by the end of this section, you will:.

- Explain how and why colonial attitudes about government and the individual changed in the years leading up to the American Revolution

Suggested Sequencing

Use this Narrative with the Signing the Declaration of Independence Decision Point to give students a full picture of the declaration.

In early 1776, war raged across the colonies. The siege of Boston had been lifted, but a larger British invasion force was preparing to attack New York. The colonies were drawing up their own constitutions and declaring their rights. It was time for the Continental Congress to confront the pressing question of independence.

In mid-January, pamphleteer Thomas Paine published Common Sense , which attacked King George III as a “royal brute” and undermined the idea of hereditary monarchy. Paine argued for independence and liberty. He proclaimed that “in free countries the law ought to be king.” The forty-six-page pamphlet is reputed to have sold an incredible 150,000 copies (to a population of not quite three million), giving it an even wider audience, because people passed it around or publicly read it aloud. Common Sense excited a colonial thirst for independence.

On May 15, Congress passed a resolution calling on assemblies and conventions to “adopt such government as shall, in the opinion of the representatives of the people, best conduce to the happiness and safety of their constituents in particular and America in general.” Massachusetts delegate John Adams thought drawing up republican-written constitutions was an act of “independence itself.” He added a preamble that forcefully asserted:

It is necessary that the exercise of every kind of authority under the said Crown should be totally suppressed, and all the powers of government exerted, under the authority of the people of the colonies, for the preservation of internal peace, virtue, and good order, as well as for the defense of their lives, liberties, and properties, against the hostile invasions and cruel depredations of their enemies.

The same day, the Virginia Convention directed its delegates in Philadelphia to “propose to that respectable body to declare the United Colonies free and independent states, absolved from all allegiance to, or dependence upon, the crown or parliament of Great Britain.” As fighting raged between colonists and redcoats, momentum for independence continued to build.

On June 7, Virginian Richard Henry Lee rose on the floor of Congress and proposed that “these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.” The controversial resolution sparked a contentious debate. Delegate John Dickinson, who in his essay Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania had protested British actions in the colonies, argued against the call for independence, believing the time was not yet right for separation and that violence should not be used to resolve the conflict. Other delegates, like Edward Rutledge from South Carolina and James Wilson of Pennsylvania, opposed Lee’s resolution on principle, because they had not been authorized to support it by their constituents.

Congress appointed a committee of five – John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Robert Livingston, Roger Sherman, and Thomas Jefferson – to draft a Declaration of Independence. The committee, in turn, assigned the task of writing the document to thirty-three-year-old Jefferson. The reason, John Adams later reflected, was “the elegance of his pen.” Jefferson was the author of several important works on natural rights and republican government, including the 1774 pamphlet, Summary View of the Rights of British North America , in which he wrote that the rights of the people were “derived from the laws of nature, and not as the gift of their chief magistrate.” In July 1775, Jefferson had also written the “Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms.”

Jefferson had with him a copy of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, which had been printed in the Pennsylvania Gazette on June 12. That influential document asserted the rights of nature and maintained that the purpose of government was to ensure:

That all men are by nature equally free and independent and have certain inherent rights, of which, when they enter into a state of society, they cannot by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity; namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.

On the evenings of June 12 and 13, Jefferson sat in his boardinghouse and composed a draft of the Declaration of Independence. He submitted it to Adams and the committee, which made several edits, and the document was sent to Congress.

This famous 1819 painting by John Trumbull shows members of the committee entrusted with drafting the Declaration of Independence presenting their work to the Continental Congress in 1776. Note the British flags on the wall. From the British perspective, each man who signed this document was committing treason.

On July 1, while a thunderstorm raged outside, Congress held an epic debate between John Dickinson and John Adams. Dickinson opposed a hasty separation with Britain and argued for reconciliation. He warned his fellow delegates that they were about to “brave the storm in a skiff made of paper.” Adams passionately advocated for declaring independence. After nine hours of speeches that ran into the evening, four colonies still voted against Richard Henry Lee’s resolution for independence.

With the other two members of Delaware’s delegation in disagreement, Caesar Rodney mounted a horse and rode seventy miles through the rain to break the tie, arriving the next morning to ensure the colony’s vote in favor of independence. Dickinson and Robert Morris abstained and allowed the Pennsylvania delegation’s vote for independence, despite their personal opposition. South Carolina held out until Rutledge, recognizing the importance of a unanimous declaration by the entire Congress, decided to change his vote in favor of the resolution. New York’s delegates, awaiting instructions from their legislature, abstained for several days. Nonetheless, on July 2, Congress voted to approve Lee’s resolution. John Adams exulted to his wife Abigail that Americans would celebrate the day forever as their day of independence.

Congress revised the Declaration of Independence the following day and altered approximately a quarter of the text, making the final product an expression of the entire Congress. Heavily influenced by John Locke’s social contract idea in his Second Treatise of Government , the document called for a government created by the consent of the people, recognizing that rights came not from government but from “nature and nature’s God.” It proclaimed that “we hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” The Declaration argued that republican government was based on a social compact in which the sovereign people voluntarily consented to govern themselves through representatives entrusted with protecting their inalienable rights. The people had the right to overthrow a government that violated their natural rights:

That to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, that whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness.

A list of grievances indicted the king for “repeated injuries and usurpations” of the colonists’ rights. Taken together, these offenses proved a “design to reduce them under absolute despotism.” This attempt to impose “an absolute tyranny” justified severing their connection with the British Crown and declaring independence. With a “firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence,” the delegates pledged to each other “our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor.”

Adopted on July 4, 1776, the Declaration of Independence was read to enthusiastic crowds and members of the army. No longer colonists, Americans had laid the foundation for their republic in the universal principles of natural rights and consensual self-government.

Review Questions

1. Which of the following documents did the most to shift public opinion toward independence in early 1776?

- The Declaration of Independence

- Common Sense

- The May 15 Resolution

- John Locke’s Second Treatise of Government

2. Which of the following is the most accurate description of the process of declaring independence?

- The notion of natural rights of life, liberty, and property was a radical, and uniquely American, ideal.

- The Declaration of Independence was written solely by Thomas Jefferson and passed without revision by Congress.

- The Declaration of Independence was unanimously supported by the Continental Congress, which reflected the unanimity of popular opinion on the issue.

- The writing of an official declaration was precipitated by increased British aggression, and full-scale war was imminent, which was a tipping point for Congress.

3. Which document was a national bestseller that argued for American independence and convinced many colonists to become Patriots?

- Declaration of Independence

- Virginia Statute of Religious Freedom

- Olive Branch Petition

4. Which of the following best explains the process of writing the Declaration of Independence?

- Thomas Jefferson took it upon himself to write the document without guidance from the Continental Congress.

- After multiple calls for independence, a committee was created to collaborate on a document that would go through revisions and debate.

- A small radical faction within the Continental Congress met without permission to write a document that would galvanize the independence movement.

- By May 1776, each colony was convinced of the need for independence, and all worked together to create a document that represented their views.

5. Which colony was the first to call for “free and independent states?”

- Massachusetts

- South Carolina

6. Which of the following documents did not influence Thomas Jefferson as he wrote the Declaration?

- John Locke’s Treatise on Government

- Thomas Paine’s Common Sense

- George Mason’s Virginia Declaration of Rights

- Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan

7. When the Continental Congress approved the Declaration of Independence, it

- was the culmination of thorough debate and extensive negotiation necessary to achieve a unanimous decision

- was then published for colonists who were to vote on whether they supported it

- was positively received by the Loyalists who wanted colonists to form their own country and leave Great Britain

- immediately created a new country that was recognized by other powers like France

8. The Declaration of Independence did not include

- a list of grievances against the king

- a statement of political theory articulating that the government was responsible to the people

- a list of signatures that made the signers vulnerable to prosecution for treason if they lost the war or were captured

- an Olive Branch Petition listing conditions that, if met by the British, would result in the colonists’ withdrawing the Declaration

Free Response Questions

- Identify and explain two different ideological origins that shaped colonial thinking about independence and republican self-government.

- How was the adoption of independence part of a moment of great deliberation and compromise for the colonies?

AP Practice Questions

“Whereas his Britannic Majesty, in conjunction with the lords and commons of Great Britain, has, by a late act of Parliament, excluded the inhabitants of these United Colonies from the protection of his crown; And whereas, no answer, whatever, to the humble petitions of the colonies for redress of grievances and reconciliation with Great Britain, has been or is likely to be given; but, the whole force of that kingdom, aided by foreign mercenaries, is to be exerted for the destruction of the good people of these colonies; And whereas, it appears absolutely irreconcileable to reason and good Conscience, for the people of these colonies now to take the oaths and affirmations necessary for the support of any government under the crown of Great Britain, and it is necessary that the exercise of every kind of authority under the said crown should be totally suppressed, and all the powers of government exerted, under the authority of the people of the colonies, for the preservation of internal peace, virtue, and good order, as well as for the defence of their lives, liberties, and properties, against the hostile invasions and cruel depredations of their enemies; therefore, resolved, &c.”

John Adams, Preamble, May 15, 1776

1. Why did John Adams tell Abigail Adams that the preamble to the May 15 Resolution was “a compleat Seperation” and “a total absolute Independence, not only of her Parliament but of her Crown”?

- The preamble sought to reconcile with Great Britain through additional petitions.

- Reason and conscience dictated that colonists could no longer proclaim allegiance to Britain.

- Regardless of the powers exerted, it was not possible for the colonies to preserve internal peace, virtue, and good order on their own.

- The colonies were still loyal to the king even if Parliament passed repressive measures.

“A DECLARATION OF RIGHTS made by the representatives of the good people of Virginia, assembled in full and free Convention, which rights do pertain to them and their posterity, as the basis and foundation of government. 1. THAT all men are by nature equally free and independent, and have certain inherent rights, of which, when they enter into a state of society, they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity; namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety. 2. That all power is vested in, and consequently derived from, the people; that magistrates are their trustees and servants, and at all times amenable to them.”

2. Why did John Adams tell Abigail Adams that the preamble to the May 15 Resolution was “a compleat Seperation” and “a total absolute Independence, not only of her Parliament but of her Crown”?

- The Declaration of Independence partially echoed the Virginia Declaration of Rights, featuring similar language and ideals.

- The Declaration of Independence built on the assertions of the Virginia Declaration of Rights and officially created a national government.

- The Declaration of Independence responded to the Virginia Declaration of Rights by offering an opposing view on natural rights and independence.

- The Declaration of Independence led to the creation of Virginia Declaration of Rights and other state declarations that were aligned with its vision.

“With respect to our rights, and the acts of the British government contravening those rights, there was but one opinion on this side of the water. All American whigs thought alike on these subjects. When forced therefore to resort to arms for redress, an appeal to the tribunal of the world was deemed proper for our justification. This was the object of the Declaration of Independence. Not to find out new principles, or new arguments, never before thought of, not merely to say things which had never been said before; but to place before mankind the common sense of the subject; [. . .] terms so plain and firm, as to command their assent, and to justify ourselves in the independent stand we [. . .] compelled to take. Neither aiming at originality of principle or sentiment, nor yet copied from any particular and previous writing, it was intended to be an expression of the american mind, and to give to that expression the proper tone and spirit called for by the occasion. All it’s authority rests then on the harmonising sentiments of the day, whether expressed, in conversns in letters, printed essays or in the elementary books of public right, as Aristotle, Cicero, Locke, Sidney Etc.”

Thomas Jefferson, Letter to Henry Lee, May 8, 1825

3. According to Thomas Jefferson, what was the purpose of the Declaration of Independence at the moment of its drafting?

- To counter the arguments of the Tories against independence

- To express common political principles and their basis in natural rights

- To set a plan for a new system and organization of government, namely one that was based in republican ideals

- To compromise between two factions of Congress and lay out their common agreements about the present state of the colonies

“They begin, my Lord, with a false hypothesis, That the Colonies are one distinct people and the kingdom another, connected by political bands. The Colonies, politically considered, never were a distinct people from the kingdom. There never has been but one political band, and that was just the same before the first Colonists emigrated as it has been ever since. . . . I should therefore be impertinent if I attempted to show in what case a whole people may be justified in rising up in oppugnation [opposition] to the powers of government, altering or abolishing them and substituting, in whole or in part, new powers in their stead; or in what sense all men are created equal, or how far life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness may be said to be unalienable. Only I could wish to ask the Delegates of Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas how their Constituents justify the depriving more than an hundred thousand Africans of their rights to liberty and the pursuit of happiness, and in some degree to their lives, if these rights are so absolutely unalienable; nor shall I attempt to confute the absurd notions of government or to expose the equivocal or inconclusive expressions contained in this Declaration; but rather to show the false representation made of the facts which are alleged to be the evidence of injuries and usurpations, and the special motives to Rebellion. There are many of them, with designs, left obscure; for as soon as they are developed, instead of justifying, they rather aggravate the criminality of this Revolt.”

Governor Thomas Hutchinson, Strictures Upon the Declaration of the Congress at Philadelphia , London, 1776

4. Which of the following is not a main assertion of Governor Hutchinson when discussing the Declaration of Independence?

- He refutes the idea that the colonists are a distinct body separate from England.

- He argues that colonists don’t treat all men equally, specifically citing slaves in the south.

- He feels the information has been manipulated and is not an accurate representation of the situation in the colonies.

- He understands the complaints of the colonists and empathizes with them but argues that with some concessions, they can be folded back into the Empire.

5. The excerpt provided could be used by historians to support which of the following arguments?

- Support for the revolution against Great Britain was unanimous in the colonies.

- Delegates from southern colonies would find it difficult to explain how rights of enslaved people are unalienable.

- Patriots ridiculed the principle that political bands ever connected them with Britain.

- The Declaration of Independence included diverse opinions.

Primary Sources

Adams, John. V. Preamble to Resolution on Independent Governments , 15 May 1776. Founders Online , National Archives. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-04-02-0001-0006

Declaration of Independence. July 4, 1776. Independence Hall Association. http://www.ushistory.org/DECLARATION/document/

Jefferson, Thomas. “Document: Letter to Henry Lee. May 8, 1825.” TeachingAmericanHistory.org. http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/letter-to-henry-lee/

Virginia Declaration of Rights. June 12, 1776. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. https://www.history.org/Almanack/life/politics/varights.cfm

Suggested Resources

Allen, Danielle. Our Declaration: A Reading of the Declaration of Independence in Favor of Equality . New York: Liveright, 2014.

Arnn, Larry P. The Founders’ Key: The Divine and Natural Connection Between the Declaration and the Constitution and What We Risk by Losing It. Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2012.

Becker, Carl. The Declaration of Independence: A Study in the History of Political Ideas . New York: Vintage, 1922.

Beeman, Richard. Our Lives, Our Fortunes, and Our Sacred Honor: The Forging of American Independence, 1774-1776 . New York: Basic, 2013.

Ellis, Joseph J. Revolutionary Summer: The Birth of American Independence . New York: Knopf, 2013.

Hogeland, William. Declaration: The Nine Tumultuous Weeks When America Became Independent, May 1-July 4, 1776 . New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010.

Maier, Pauline. American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence . New York: Vintage, 1997.

Wills, Garry. Inventing America: Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence . Garden City: Doubleday, 1978.

Related Content

Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness

In our resource history is presented through a series of narratives, primary sources, and point-counterpoint debates that invites students to participate in the ongoing conversation about the American experiment.

Rhetoric of The Declaration of Independence Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

The ancient Greek philosopher, Aristotle, prescribed three modes of rhetorical persuasion – ethos, pathos, and logos. An outstanding rhetoric persuasion should have an ethical appeal, an emotional appeal, as well as a logical appeal. In the Declaration of Independence document, and Thomas Jefferson’s account, the founding fathers not only aired grievances, truths, and the denial of liberty, but they also artistically embroidered all the elements of rhetoric persuasion in their assertions. The Declaration of Independence appeals to ethics, emotions, and logic – the three fundamental elements of rhetoric.

The Declaration of Independence’s appeal to ethics is undisputable. In the opening paragraphs of the declaration, there is an ethical appeal for why the colonists needed separation from the colonizer. The first paragraph of the declaration read,

When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another and to assume among the powers of the earth […] decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation (“The Declaration of Independence”).

In the statement above, Jefferson and the founding fathers were appealing to ethics. It was necessary and essential to have an ethical explanation for that desire to gain support for their need to be independent. The founding fathers needed to explain why they needed to separate as decent respect to the opinions of humankind. In the second paragraph, the declaration continued on the ethical appeal stating that humans bore equal and unalienable rights – “to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” (“The Declaration of Independence”).

These statements are moral, ethical, and legal overtones that the audience can associate themselves with. If someone were to ask, “Why is this separation necessary?” The answer would come right from the second paragraph. Jefferson and the founding fathers were more than aware that such a move as declaring independence required an ethical appeal with salient and concrete causes in place of light and transient causes, and they appealed to ethics right at the beginning of the declaration.

Other than appealing to ethics, Jefferson and the founding fathers required the audience to have an emotional attachment to the Declaration of Independence. The audience had to feel the same way as the founding fathers did. In the second paragraph of the declaration document, the drafters appealed that the people had a right to change and abolish a government that had become destructive of the equal and inalienable rights of all humankind. “Humankind is more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable than to the right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed” (“The Declaration of Independence”).

However, if there is “a long train of abuses and usurpations” (“The Declaration of Independence”), there was a need to reduce the adversities under absolute Despotism, as the people’s right and duty. At the beginning of paragraph 30, the drafters of the declaration called their preceding assertions oppressions. An oppressed person is not a happy person. By making the audience – the colonists – remember their suffering and how patient they had been with the colonizers, Jefferson and the drafters appealed to the audience’s emotions.

The other rhetorical appeal in the Declaration of Independence is that of logic – logos. Other than bearing ethical and emotional overtones, the declaration equally bore logical sentiments. At the end of paragraph two, The Declaration of Independence reads, “To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world” (“The Declaration of Independence”), after which follows a string of grievances against the King of England and the colonizers. The entire draft bears logical appeal and the rationale behind the call for independence. How the founding fathers interwove the causes for independence in the declaration is a representation of logic.

There is evidence of inductive reasoning showing what the colonists required – independence from England – and why that was the only resort. The declaration is also logically appealing because it is not that the colonists have not sought the colonizer’s ear for the grievances they had; they had “In every stage of these Oppressions Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms, but their repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury” (“The Declaration of Independence”). Reason would only dictate that the colonists resort to other measures such as declaring themselves independent from a tyrannical system.

A rhetorical analysis of the Declaration for Independence shows the employment of ethical (ethos), emotional (pathos), and logical (logos) appeals by the drafters. In the statement of their reasons for calling to be independent of the crown, the founding fathers elucidated an ethical appeal. In the statement of their grievances against the King of England, the drafters appealed emotionally to their audience. Lastly, the drafters of the declaration interwove logic into every argument they presented by employing inductive reasoning in the description of the relationship between the colonies and the colonizer and why they formerly needed emancipation from the latter.

“ The Declaration of Independence: The Want, Will, and Hopes of the People . “ Ushistory.org , 2018. Web.

- European Security and Defense Policy

- Dr.Knightly’s Problems in Academic Freedom

- Use of Details to Fuel Mission

- The Technique of a Great Speech

- Carmine Gallo's "Talk Like TED": Concepts and Ideas

- "Confessions of a Public Speaker" by Scott Berkun

- Smoking Bans: Protecting the Public and the Children of Smokers

- Cherie Blair Speech Analysis

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, July 3). Rhetoric of The Declaration of Independence. https://ivypanda.com/essays/rhetoric-of-the-declaration-of-independence/

"Rhetoric of The Declaration of Independence." IvyPanda , 3 July 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/rhetoric-of-the-declaration-of-independence/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Rhetoric of The Declaration of Independence'. 3 July.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Rhetoric of The Declaration of Independence." July 3, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/rhetoric-of-the-declaration-of-independence/.

1. IvyPanda . "Rhetoric of The Declaration of Independence." July 3, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/rhetoric-of-the-declaration-of-independence/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Rhetoric of The Declaration of Independence." July 3, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/rhetoric-of-the-declaration-of-independence/.

The Intolerable Acts: Catalysts of Revolutionary Change

This essay about the Intolerable Acts discusses the series of punitive measures passed by the British Parliament in 1774 that aimed to reassert control over the American colonies following the Boston Tea Party. The essay explains how the Boston Port Act, Massachusetts Government Act, Administration of Justice Act, and Quartering Act were intended to discipline the colonies but instead fueled widespread resentment and resistance. These acts, perceived as severe injustices, united the colonies and contributed to the convening of the First Continental Congress. The essay emphasizes how the Intolerable Acts played a crucial role in galvanizing the colonies towards the pursuit of independence, highlighting their significance as catalysts for the Revolutionary War.

How it works