Advertisement

Cognitive Biases in Criminal Case Evaluation: A Review of the Research

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 23 June 2021

- Volume 37 , pages 101–122, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Vanessa Meterko ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1207-8812 1 &

- Glinda Cooper 1

20k Accesses

7 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Psychological heuristics are an adaptive part of human cognition, helping us operate efficiently in a world full of complex stimuli. However, these mental shortcuts also have the potential to undermine the search for truth in a criminal investigation. We reviewed 30 social science research papers on cognitive biases in criminal case evaluations (i.e., integrating and drawing conclusions based on the totality of the evidence in a criminal case), 18 of which were based on police participants or an examination of police documents. Only two of these police participant studies were done in the USA, with the remainder conducted in various European countries. The studies provide supporting evidence that lay people and law enforcement professionals alike are vulnerable to confirmation bias, and there are other environmental, individual, and case-specific factors that may exacerbate this risk. Six studies described or evaluated the efficacy of intervention strategies, with varying evidence of success. Further research, particularly in the USA, is needed to evaluate different approaches to protect criminal investigations from cognitive biases.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Cognitive and Social Psychological Bases of Bias in Forensic Mental Health Judgments

Decision-Making in the Courtroom: Jury

Is forensic evidence impartial cognitive biases in forensic analysis.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Decades of research in cognitive and social psychology have taught us that there are limitations to human attention and decision-making abilities (see, for example, Gilovich et al. 2002 ). We cannot process all the stimuli that surround us on a daily basis, so instead we have adapted for efficiency by attuning to patterns and developing mental shortcuts or rules of thumb to help us effectively navigate our complex world. While this tendency to rely on heuristics and biases can serve us well by allowing us to make quick decisions with little cognitive effort, it also has the potential to inadvertently undermine accuracy and thus the fair administration of justice.

Cognitive bias is an umbrella term that refers to a variety of inadvertent but predictable mental tendencies which can impact perception, memory, reasoning, and behavior. Cognitive biases include phenomena like confirmation bias (e.g., Nickerson 1998 ), anchoring (e.g., Tversky & Kahneman 1974 ), hindsight bias (e.g., Fischhoff 1975 ), the availability heuristic (e.g., Tversky & Kahneman 1973 ), unconscious or implicit racial (or other identifying characteristics) bias (e.g., Greenwald et al. 1998 ; Staats et al. 2017 ), and others. In this context, the word “bias” does not imply an ethical issue (e.g., Dror 2020 ) but simply suggests a probable response pattern. Indeed, social scientists have demonstrated and discussed how even those who actively endorse egalitarian values harbor unconscious biases (e.g., Pearson et al. 2009 ; Richardson 2017 ) and how expertise, rather than insulating us from biases, can actually create them through learned selective attention or reliance on expectations based on past experiences (e.g., Dror 2020 ). Consequently, we recognize the potential for these human factors to negatively influence our criminal justice process.

In an effort to explore the role of cognitive biases in criminal investigations and prosecutions, we conducted a literature review to determine the scope of available research and strength of the findings. The questions guiding this exercise were as follows: (1) what topics have been researched so far and where are the gaps?; (2) what are the methodological strengths and limitations of this research?; and (3) what are the results, what do we know so far, and where should we go from here?

We searched PsycINFO for scholarly writing focused on cognitive biases in criminal investigations and prosecutions in December 2016 and again in January 2020. Footnote 1 We reviewed all results by title and then reviewed the subset of possibly-relevant titles by abstract, erring on the side of over-inclusivity. We repeated this process using the Social Sciences Full Text, PubMed, and Criminal Justice Abstracts with Full Text databases to identify additional papers. Finally, we manually reviewed the reference lists in the identified papers for any unique sources we may have missed in prior searches.

We sorted the articles into categories by the actor or action in the criminal investigation and prosecution process that they addressed, including physical evidence collection, witness evaluation, suspect evaluation, forensic analysis and testimony, police case evaluation (i.e., integrating and drawing conclusions based on the totality of the evidence), prosecutors, defense attorneys, judges, juries, and sentencing. Within each of these categories, we further sorted the articles into one of three types of sources: “primary data studies” describing experimental or observational studies that involved data collection or analysis, “intervention studies” that were solution-oriented and involved implementing some type of intervention or training to prevent or mitigate a phenomenon, and “secondary sources” (e.g., commentaries, letters, reviews, theoretical pieces, general book chapters) that discussed cognitive biases but did not present primary data.

To narrow the scope of this review, we did not include articles that focus solely on implicit racial bias or structural racial bias in the criminal legal system. The foundational and persistent problem of racial (particularly anti-Black) bias throughout our legal system—from policing to sentencing (e.g., Voigt et al. 2017 ; NYCLU 2011 ; Blair et al. 2004 ; Eberhardt et al. 2006 )—has been clearly demonstrated in laboratory experiments and analyses of real-world data and is well-documented in an ever-growing body of academic publications and policy reports (e.g., Correll et al. 2002 ; Chanin et al. 2018 ; Owens et al. 2017 ; Staats et al. 2017 ).

Scope of Available Research and Methodology

Cognitive biases in forensic science have received the most attention from researchers to date (for a review of these forensic science studies, see Cooper & Meterko 2019 ). The second most substantial amount of scholarship focused on case evaluation (i.e., integrating and drawing conclusions based on the totality of the evidence in a case). Ultimately, we found 43 scholarly sources that addressed various issues related to the evaluation of the totality of evidence in criminal cases: 25 primary data (non-intervention) studies, five intervention studies, and one additional paper that presented both primary data and interventions, and 12 secondary sources. For the remainder of this article, we focus solely on the primary data and intervention studies. One of the primary data studies (Fahsing & Ask 2013 ) described the development of materials that were used in two subsequent studies included in this review (Fahsing & Ask 2016 ; 2017 ), and thus, this materials-development paper is not reviewed further here. Table 1 presents an overview of the research participants and focus of the other 30 primary data and intervention studies included in our review.

One challenge in synthesizing this collection of research is the fact that these studies address different but adjacent concepts using a variety of measures and—in some instances—report mixed results. The heterogeneity of this research reveals the complex nature of human factors in criminal case evaluations.

Eighteen of the 30 papers (13 primary data and three intervention) included participants who were criminal justice professionals (e.g., police, judges) or analyzed actual police documents. An appendix provides a detailed summary of the methods and results of the 18 criminal justice participant (or document) studies. Fifteen papers were based on or presented additional separate analyses with student or lay participants. Recruiting professionals to participate in research is commendable as it is notoriously challenging but allows us to identify any differences between those with training and experience versus the general public, and to be more confident that conclusions will generalize to real-world behavior. Of course, representativeness (or not) must still be considered when making generalizations about police investigations.

Reported sample sizes ranged from a dozen to several hundred participants and must be taken into account when interpreting individual study results. Comparison or control groups and manipulation checks are also essential to accurately interpreting results; some studies incorporated these components in their designs while others did not.

Most studies used vignettes or case materials—both real and fictionalized—as stimuli. Some studies did not include enough information about stimulus or intervention materials to allow readers to critically interpret the results or replicate an intervention test. Future researchers would benefit from publishers making more detailed information available. Further, while the use of case vignettes is a practical way to study these complex scenarios, this approach may not completely mimic the pressures of a real criminal case, fully appreciate how the probative value of evidence can depend on context, or accurately reflect naturalistic decision-making.

Notably, only two of the criminal case evaluation studies using professional participants were conducted in the USA; all others were based in Europe (Austria, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and the UK). The differences between police training, operations, and the criminal justice systems writ large should be considered when applying lessons from these studies to the USA or elsewhere.

Finally, all of these papers were published relatively recently, within the past 15 years. This emerging body of research is clearly current, relevant, and has room to grow.

Research Findings

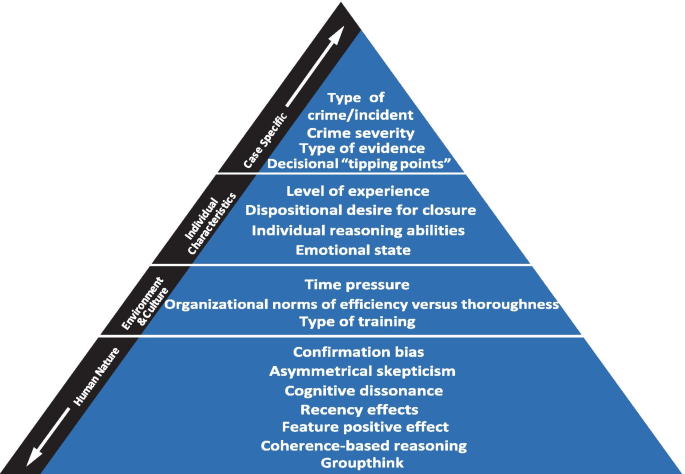

The primary data studies address a constellation of concepts that demonstrate how human factors can inadvertently undermine the seemingly objective and methodical process of a criminal investigation. To organize these concepts, we used a taxonomy originally developed to describe potential sources of bias in forensic science observations and conclusions as a guide (Dror 2017 ; Dror et al. 2017 ) and adapted it to this collection of case evaluation literature. Footnote 2 As in Dror’s taxonomy, the broad base of this organizing pyramid is “human nature,” and as the pyramid narrows to its peak, potential sources of bias become increasingly dependent on environmental, individual, and case-specific circumstances and characteristics (Fig. 1 ). Some authors in this collection address more than one of these research areas within the same paper through multiple manipulations or a series of studies (Table 1 ).

Organizational framework for case evaluation studies, adapted from Dror’s ( 2017 ) taxonomy of different sources of potential bias that may cognitively contaminate forensic observations and conclusions. The specific factors listed in this pyramid are those that were examined in the collection of studies in the present literature review

Human Nature

The “human nature” studies include those that demonstrate universal psychological phenomena and their underlying mechanisms in the context of a criminal case evaluation. Several studies focused on confirmation bias. Confirmation bias, sometimes colloquially referred to as “tunnel vision,” denotes selective seeking, recalling, weighting, and/or interpreting information in ways that support existing beliefs, expectations, or hypotheses, while simultaneously avoiding or minimizing inconsistent or contradictory information (Nickerson 1998 ; Findley 2012 ). Some authors in this collection of studies used other terms to describe this concept or elements of it, including “context effects,” the term used by Charman et al. ( 2015 ) to describe when “a preexisting belief affects the subsequent interpretation of evidence” (p. 214), and asymmetrical skepticism (Ask & Granhag 2007b ; Marksteiner et al. 2010 ).

Eight studies with law enforcement personnel (Ask & Granhag 2007b ; Ask et al. 2008 ; Charman et al. 2017 ; Ditrich 2015 ; Groenendaal & Helsloot 2015 ; Marksteiner et al. 2010 ; Rassin 2010 ; Wallace 2015 ) examined aspects of confirmation bias; one addressed the distinct but related phenomenon of groupthink (Kerstholt & Eikelboom 2007 ). The importance of this issue was demonstrated by a survey of an unspecified number of professional crime scene officers conducted by Ditrich ( 2015 ), asking for their opinions about the relative frequency and severity of various cognitive errors that could potentially negatively affect a criminal investigation; based on their experiences, respondents highlighted confirmation bias (as well as overestimating the validity of partial information and shifting the burden of proof to the suspect). The other studies within this group used experimental designs to assess police officers’ evaluation of evidence. Charman et al. ( 2017 ) reported that police officers’ initial beliefs about the innocence or guilt of a suspect in a fictional criminal case predicted their evaluation of subsequent ambiguous evidence, which in turn predicted their final beliefs about the suspect’s innocence or guilt. This is not the only study to demonstrate that, like the rest of us, police officers are susceptible to confirmation bias. Ask and colleagues ( 2008 ) found that police recruits discredited or supported the same exact evidence (“the viewing distance of 10 m makes the witness identification unreliable” versus “from 10 m one ought to see what a person looks like”) depending on whether it was consistent or inconsistent with their hypothesis of a suspect’s guilt. Ask and Granhag ( 2007b ) found that when experienced criminal investigators read a vignette that implied a suspect’s guilt (but left room for an alternative explanation), they rated subsequent guilt-consistent evidence as more credible and reliable than evidence that was inconsistent with their theory of guilt; similar results were seen in a study of police officers, district attorneys, and judges by Rassin ( 2010 ).

Marksteiner et al. ( 2010 ) investigated the motivational underpinnings of this type of asymmetrical skepticism among police trainees, asking whether it is driven by a desire to reconcile inconsistent information with prior beliefs or by the goal of case closure, and encountered mixed results. The group who initially hypothesized guilt reacted as expected, rating subsequent incriminating evidence as more reliable, but in the group whose initial hypothesis was innocence, there was no difference in the way that they rated additional consistent or inconsistent information. Wallace ( 2015 ) found that the order in which evidence was presented influenced guilt beliefs. When police officers encountered exculpatory evidence prior to inculpatory evidence, guilt belief scores decreased, suggesting their final decisions were influenced by their initial impressions. Kerstholt and Eikelboom ( 2007 ) describe how teams tend to converge on one interpretation, and once such an interpretation is adopted, individual members are less able to examine underlying assumptions critically. They asked independent crime analysts to evaluate a realistic criminal investigation with fresh eyes and found that they were demonstrably influenced when they were aware of the investigative team’s existing working hypothesis.

Studies in student and general populations examining confirmation bias and other aspects of human cognition (Ask et al. 2011b ; Charman et al. 2015 ; Eerland et al. 2012 ; Eerland & Rassin 2012 ; Greenspan & Surich 2016 ; O’Brien 2007 ; 2009 ; Price & Dahl 2014 ; Rassin et al. 2010 ; Simon et al. 2004 ; Wastell et al. 2012 ) reported similar patterns to those described above with police participants. O’Brien ( 2007 ; 2009 ) found that students who named a suspect early in a mock criminal investigation were biased towards confirming that person’s guilt as the investigation continued. O’Brien measured memory for hypothesis-consistent versus hypothesis-inconsistent information, interpretation of ambiguous evidence, participants’ decisions to select lines of inquiry into the suspect or an alternative, and ultimate opinions about guilt or innocence. In a novel virtual crime scene investigation, Wastell et al. ( 2012 ) found that all students (those who ultimately chose the predetermined “correct” suspect from the multiple available people of interest and those who chose incorrectly) sought more chosen-suspect-consistent information during the exercise. However, those who were ultimately unsuccessful (i.e., chose the wrong person) spent more time in a virtual workspace (a measure of the importance placed on potential evidence) after accessing confirmatory information. They also found that students who settled on a suspect early in the exercise—measured by prompts throughout the virtual investigation—were comparatively unsuccessful.

Other psychological phenomena such as recency effects (i.e., our ease of recalling information presented at the end of a list relative to information presented at the beginning or middle) and the feature positive effect (i.e., our tendency to generally attune to presence more than absence) were also examined in studies with student or general population participants. Price and Dahl ( 2014 ) explored evidence presentation order and found that under certain circumstances, evidence presented later in an investigation had a greater impact on student participant decision-making in a mock criminal investigation. Charman and colleagues also found order of evidence presentation influenced ratings of strength of evidence and likelihood of guilt in their 2015 study of evidence integration with student participants. These results appear to provide evidence against the presence of confirmation bias, but recency effects still demonstrate the influence of human factors as, arguably, the order in which one learns about various pieces of evidence -whether first or last- should not impact interpretation. Several research teams found that a positive eyewitness identification is seen as more credible than a failure to identify someone (Price & Dhal 2014 , p.147) and the presence of fingerprints—as opposed to a lack of fingerprints—is more readily remembered and used to make decisions about a criminal case (Eerland et al. 2012 ; Eerland & Rassin 2012 ), even though the absence of evidence can also be diagnostic. Other researchers highlighted our psychic discomfort with cognitive dissonance (Ask et al. 2011b ) and our tendency to reconcile ambiguity and artificially impose consistency in a criminal case by engaging in “ bidirectional coherence-based reasoning” (Simon et al. 2004 ; Greenspan & Surich 2016 ).

Environment and Culture

The three “environment and culture” studies with police personnel (Ask & Granhag 2007b ; Ask et al. 2011a ; Fahsing & Ask 2016 ) revealed the ways in which external factors can influence an investigation. For instance, type of training appears to impact the ability to generate a variety of relevant hypotheses and actions in an investigation. English and Norwegian investigators are trained and performed differently when faced with semi-fictitious crime vignettes (Fahsing & Ask 2016 ). Organizational culture can impact the integrity of an investigation as well. Ask and colleagues ( 2011a ) concluded that a focus on efficiency—as opposed to thoroughness—produces more cursory processing among police participants, which could be detrimental to the accurate assessment of evidence found later in an investigation. Ask and Granhag ( 2007b ) observed that induced time pressure influenced officers’ decision-making, creating a higher tendency to stick with initial beliefs and a lower tendency to be influenced by the evidence presented.

Individual Characteristics

Seven “individual characteristics” studies with police personnel (Ask & Granhag 2005 ; 2007a ; Dando & Ormerod 2017 ; Fahsing & Ask 2016 ; 2017 ; Kerstholt & Eikelboom 2007 ; Wallace 2015 ) plus two studies with student populations (Rassin 2010 , 2018a ) examined ways in which personal attributes can influence an investigation. Varying amounts of professional experience may matter when it comes to assessments of potential criminal cases and assumptions about guilt. For instance, police recruits appear to have a strong tendency toward criminal—as opposed to non-criminal—explanations for an ambiguous situation like a person’s disappearance (Fahsing & Ask 2017 ) and less experienced recruits show more suspicion than seasoned investigators (Wallace 2015 ). In a departure from the typical mock crime vignette method, Dando and Ormerod ( 2017 ) reviewed police decision logs (used for recording and justifying decisions made during serious crime investigations) and found that senior officers generated more hypotheses early in an investigation, and switched between considering different hypotheses both early and late in an investigation (suggesting a willingness to entertain alternative theories) compared with inexperienced investigators. An experimental study, however, found that professional crime analyst experience level (mean 7 months versus 7 years) was not related to case evaluation decisions and did not protect against knowledge of prior interpretations of the evidence influencing conclusions (Kerstholt & Eikelboom 2007 ).

Two studies examined differences in reasoning skills in relation to the evaluation of evidence. Fahsing and Ask ( 2017 ) found that police recruits’ deductive and inductive reasoning skills were not associated with performance on an investigative reasoning task. In contrast, in a study with undergraduate students, accuracy of decision-making regarding guilt or innocence in two case scenarios was associated with differences in logical reasoning abilities as measured by a test adapted from the Wason Card Selection Test (Rassin 2018a ).

Ask and Granhag ( 2005 ) found inconsistent results in a study of police officers’ dispositional need for cognitive closure and the effect on criminal investigations. Those with a high need for cognitive closure (measured with an established scale) were less likely to acknowledge inconsistencies in case materials when those materials contained a potential motive for the suspect, but were more likely to acknowledge inconsistencies when made aware of the possibility of an alternative perpetrator. In a replication study with undergraduate students, Ask & Granhag ( 2005 ) found that initial hypotheses significantly affected subsequent evidence interpretation, but found no interaction with individual need for cognitive closure. Students who were aware of an alternative suspect (compared with those aware of a potential motive for the prime suspect) were simply less likely to evaluate subsequent information as evidence supporting guilt.

In another study, when Ask and Granhag ( 2007a ) induced negative emotions in police officers and then asked them to make judgments about a criminal case, sad participants were better able to substantively process the consistency of evidence or lack thereof, whereas angry participants used heuristic processing.

Case-Specific

Four studies of police personnel (Ask et al. 2008 ; Fahsing & Ask 2016 ; 2017 ; Wallace 2015 ), one using police records (Dando & Omerod 2017 ), and three studies of student populations (Ask et al. 2011b ; O’Brien 2007 ; 2009 ; Rassin et al. 2010 ) examined “case-specific” and evidence-specific factors. In a study of police officers, Ask and colleagues ( 2008 ) showed that the perceived reliability of some types of evidence (DNA versus photographs versus witnesses) is more malleable than others; similar results pertaining to DNA versus witness evidence were found in a study of law students (Ask et al. 2011b ).

Fahsing and Ask ( 2016 ) found that police recruits who were presented with a scenario including a clear “tipping point” (an arrest) did not actually produce significantly fewer hypotheses than those who were not presented with a tipping point (though they acknowledge that the manipulation—one sentence embedded in a case file—may not have been an ecologically valid one). In a subsequent study with police recruits, the presence of a tipping point resulted in fewer generated hypotheses, but the difference was not statistically significant (Fahsing & Ask 2017 ).

Other studies using law students (Rassin et al. 2010 ) or undergraduate students (O’Brien 2007 ) examined the influence of crime severity on decision-making. Rassin et al. ( 2010 ) observed that the affinity for incriminating evidence increases with crime severity, but in one of O’Brien’s ( 2007 ) studies, crime severity did not have a demonstrable impact on confirmation bias.

Interventions

Taken together, this body of work demonstrates vulnerabilities in criminal investigations. Some researchers have suggested theoretically supported solutions to protect against these vulnerabilities, such as gathering facts rather than building a case (Wallace 2015 ) or institutionalizing the role of a “contrarian” in a criminal investigation (MacFarlane 2008 ). Few studies have tested and evaluated these potential remedies, however. Testing is an essential prerequisite to any advocacy for policy changes because theoretically sound interventions may not, in fact, have the intended effect when applied (e.g., see below for a description of O’Brien’s work testing multiple interventions with differing results).

Four studies have examined various intervention approaches with police departments or investigators (Groenendaal & Helsloot 2015 ; Jones et al. 2008 ; Rassin 2018b ; Salet & Terpstra 2014 ). Jones et al. ( 2008 ) created a tool that helped an experimental group of investigators produce higher quality reviews of a closed murder case than those working without the aid of the review tool. Their article provides an appendix with “categories used in the review tool” (e.g., crime scene management, house-to-house enquiries, community involvement) but lacks a detailed description of the tool itself and the outcome measures. Importantly, the authors raise the possibility that a review tool like this may improve how officers think through a case because of the structure or content of the tool or it may succeed by simply slowing them down so they can think more critically and thoroughly. Another approach that shows promise in reducing tunnel vision is using a pen and paper tool to prompt investigators to consider how well the same evidence supports different hypotheses (Rassin 2018b ). In a study of actual case files, supplemented with interviews, Salet and Terpstra ( 2014 ) explored “contrarians” and found that there are real-world challenges to the position’s efficacy (e.g., personal desire to be a criminal investigator, desire for solidarity with colleagues) and considerable variability in the way contrarians approach their work, with some opting for closeness to an investigation and others opting for distance; individuals also embraced different roles (e.g., supervisor, devil’s advocate, focus on procedure). The researchers concluded that, in practice, these contrarians appear to have exerted subtle influence on investigations but there is no evidence of a radical change in case trajectory. Similarly, members of criminal investigation teams in the Netherlands reported that, in practice, designated devil’s advocates tend to provide sound advice but do not fundamentally change the course of investigations (Groenendaal & Helsloot 2015 ). Groenendaal and Helsloot describe the development and implementation of the Criminal Investigation Reinforcement Programme in the Netherlands, which was prompted by a national reckoning stemming from a widely publicized wrongful conviction. The program included new policies aimed at, among other things, reducing tunnel vision (including the use of devil’s advocates, structured decision-making around “hypotheses and scenarios,” and professionalized, permanent “Command Core Teams” dedicated to major crimes). This deliberate intervention provided an opportunity for researchers to interview investigators who were directly impacted by the new policies. Groenendaal and Helsloot conclude that the main effect of this intervention was an increased awareness about the potential problem of tunnel vision, and they focus on an unresolved a tension between “efficacy” (more convictions) and “precaution” (minimizing wrongful convictions). Their work underscores the importance of collecting criminal legal system data, as interviewees reported their experiences and impressions but could not report whether more correct convictions had been obtained or more wrongful convictions avoided.

Other studies have examined various intervention ideas with student populations (Haas et al. 2015 ; O’Brien 2007 ; 2009 ). Haas et al. ( 2015 ) found that using a checklist tool to evaluate evidence appears to improve students’ abductive reasoning and reduce confirmation bias. O’Brien ( 2007 ; 2009 ) found that orienting participants to being accountable for good process versus outcome had no impact, and that when participants expected to have to persuade someone of their hypothesis, this anticipation actually worsened bias. More promisingly, she discovered that participants who were asked to name a suspect early in an investigation, but were then told to consider how their selected suspect could be innocent and then generate counter-arguments, displayed less confirmation bias across a variety of measures (they looked the same as those who did not name a suspect early). But another approach—asking participants to generate two additional alternative suspects—was not effective (these participants showed the same amount of bias as those who identified just one suspect).

Zalman and Larson ( 2016 ) have observed “the failure of innocence movement advocates, activists, and scholars to view the entirety of police investigation as a potential source of wrongful convictions, as opposed to exploring arguably more discrete police processes (e.g., eyewitness identification, interrogation, handling informants)” (p.3). While the thorough examination of these discrete processes has led to a better understanding of risk factors and, ultimately, reforms in police practices (e.g., see the Department of Justice 2017 guidelines for best practices with eyewitnesses), a recent shift towards viewing wrongful convictions from a “sentinel events” Footnote 3 perspective advances the conversation around these criminal justice system failures (Doyle 2012 ; 2014 ; Rossmo & Pollock 2019 ).

This literature review has identified a body of research that lends support to this holistic perspective. The studies reviewed here address a constellation of concepts that demonstrate how the human element—including universal psychological tendencies, predictable responses to situational and organizational factors, personal factors, and characteristics of the crime itself—can unintentionally undermine truth-seeking in the complex evidence integration process. Some concepts are addressed by one study, some are addressed by several, and some studies explored multiple variables (e.g., demonstrating the existence of confirmation bias and measuring how level of professional experience plays a role).

Several contemporary studies have demonstrated the existence of confirmation bias in police officers within the context of criminal investigations. Other psychological phenomena have not been examined in police populations but have been examined in student or general populations using study materials designed to assess the interpretation of criminal case evidence and decision-making. This collection of studies also investigates the role of environmental factors that may be specific to a department or organization, characteristics of individual investigators, or of the specific case under review. At the environmental level, type of training and organizational customs were influential and are promising areas for further research as these factors are within the control of police departments and can be modified. With respect to individual characteristics, a better understanding of advantageous dispositional tendencies and what is gained by professional experience, as well as the unique risks of expertise, could lead to better recruitment and training methods. Case-specific factors are outside the control of investigators, but awareness of factors that pose a greater risk for bias could serve as an alert and future research could identify ways to use this information in practice (see also Rossmo & Pollock 2019 for an in-depth discussion of “risk recipes”).

Charman and colleagues ( 2017 ) present a particularly interesting illustration of the way in which a criminal case is not merely the sum of its parts. In this study, the researchers presented law enforcement officers with exonerating, incriminating, or neutral DNA or eyewitness evidence, collected initial beliefs about guilt, asked participants to evaluate a variety of other ambiguous evidence (alibi, composite sketch, handwriting comparison, and informant information that could be reasonably interpreted in different ways), and then provide a final rating of guilt. As hypothesized, the researchers found those who were primed with incriminating evidence at the beginning were more likely to believe the suspect guilty at the end. However, even those who initially received exonerating information and initially rated the likelihood of suspect guilt as relatively low ended up increasing their guilt rating after reviewing the other ambiguous evidence. It appears that the cumulative effect of ambiguous evidence tilted the scales towards guilt. This unexpected outcome underscores the value of understanding how the totality of evidence in a criminal case is evaluated, and has implications for the legal doctrine of “harmless error” rooted in assumptions of evidentiary independence (e.g., Hasel & Kassin 2009 ).

Consistently incorporating control groups into future study designs and including complete stimulus materials in future publications could build on this foundation. This would help future researchers fully interpret and replicate study results and would assist in determining what elements of intervention strategies work. Since the majority of these studies were conducted in Europe, it would be worthwhile to explore whether or not these results can be replicated in the USA, given the similarities and differences in our criminal justice systems and the variety of approaches used to select and train detectives across police departments. Finally, valuable future research will move beyond the demonstration of these human vulnerabilities and will design and test strategies to mitigate them in the complex real world. Footnote 4 Vignettes and mock-investigations are clever ways of studying criminal investigations, but it is worth remembering that these approaches cannot fully capture the dynamics of a real criminal investigation. Collaboration between academic researchers and criminal investigators could generate robust expansions of this work.

Evidence evaluation and synthesis in criminal investigations is, of course, just one part of a larger legal process. In addition to police, defense attorneys, prosecutors, and judges have powerful roles in determining case outcomes, especially in a system that is heavily reliant on plea bargaining. Critically addressing the potential influence of cognitive biases throughout this system, and promoting and implementing proven, practical protections against these tendencies will advance accuracy and justice.

We used the following search terms and Boolean Operators: (criminal OR justice OR police OR investigat* OR forensic* OR jury OR juries OR judge* OR conviction* OR prosecut* OR defense OR defender* OR attorn*) in any field (e.g., text, title) AND (“cognitive bias” OR “cognitive dissonance” OR “tunnel vision” OR “confirmation bias” OR “interpretive bias” OR “belief perseverance” OR “asymmetrical skepticism”) in any field (e.g., text, title).

As Dror ( 2017 ) notes, the development of this taxonomy began in a paper in 2009 (Dror 2009 ) and was further developed in a 2014 paper (Stoel et al. 2014 ), with additional sources of bias added subsequently (in Dror 2015 , and Zapf & Dror 2017 ).

According to the National Institute of Justice ( 2017 ), a sentinel event is a significant negative outcome that (1) signals underlying weaknesses in the system or process, (2) is likely the result of compound errors, and (3) may provide, if properly analyzed and addressed, important keys to strengthen the system and prevent future adverse outcomes.

As Snook and Cullen ( 2008 ) assert, “it is unrealistic to expect police officers to investigate all possible suspects, collect evidence on all of those suspects, explore all possible avenues concerning the circumstances surrounding a crime, search for disconfirming and confirming evidence of guilt for every suspect, and integrate all of this information” (p. 72). Dando and Ormerod ( 2017 ) illustrate this real-world complexity when they describe an investigation that was delayed because a call for tips led to a flood of false leads, suggesting that more information is not always better. Further, though it addresses procedural justice in street policing rather than evidence integration in a criminal investigation (and thus was not included in this review), Owens et al. ( 2018 ) provide an example of a field study, complete with published scripts. Recognizing the automated thinking and behavior that comes with job experience, these researchers tested an intervention to reduce the number of incidents resolved with arrests and use of force by implementing a training program aimed at encouraging beat officers to think more slowly and deliberately during routine encounters; they also assessed the cost of this intervention in the police department.

Ask K, Granhag PA (2005) Motivational sources of confirmation bias in criminal investigations: the need for cognitive closure. J Investig Psychol Offender Profiling 2(1):43–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/jip.19

Article Google Scholar

Ask K, Granhag PA (2007a) Hot cognition in investigative judgments: the differential influence of anger and sadness. Law Hum Behav 31(6):537–551. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-006-9075-3

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Ask K, Granhag PA (2007b) Motivational bias in criminal investigators’ judgments of witness reliability. J Appl Soc Psychol 37(3):561–591. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2007.00175.x

Ask K, Granhag PA, Rebelius A (2011a) Investigators under influence: how social norms activate goal-directed processing of criminal evidence. Appl Cogn Psychol 25(4):548–553. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1724

Ask K, Rebelius A, Granhag PA (2008) The ‘elasticity’ of criminal evidence: a moderator of investigator bias. Appl Cogn Psychol 22(9):1245–1259. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1432

Ask K, Reinhard M-A, Marksteiner T, Granhag PA (2011b) Elasticity in evaluations of criminal evidence: exploring the role of cognitive dissonance. Leg Criminol Psychol 16:289–306

Blair IV, Judd CM, Chapleau KM (2004) The influence of Afrocentric facial features in criminal sentencing. Psychol Sci 15(10):674–679. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00739.x

Chanin J, Welsh M, Nurge D (2018) Traffic enforcement through the lens of race: a sequential analysis of post-stop outcomes in San Diego. California Criminal Justice Policy Review 29(6–7):561–583. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403417740188

Charman SD, Carbone J, Kekessie S, Villalba DK (2015) Evidence evaluation and evidence integration in legal decision-making: order of evidence presentation as a moderator of context effects. Appl Cogn Psychol 30(2):214–225. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3181

Charman SD, Kavetski M, Mueller DH (2017) Cognitive bias in the legal system: police officers evaluate ambiguous evidence in a belief-consistent manner. J Appl Res Mem Cogn 6(2):193–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2017.02.001

Cooper GS, Meterko V (2019) Cognitive bias research in forensic science: a systematic review. Forensic Sci Int 297:35–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2019.01.016

Correll J, Park B, Judd CM, Wittenbrink B (2002) The police officer’s dilemma: using ethnicity to disambiguate potentially threatening individuals. J Pers Soc Psychol 83(6):1314–1329. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.6.1314

Dando CJ, Ormerod TC (2017) Analyzing decision logs to understand decision making in serious crime investigations. Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 59(8):1188–1203. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018720817727899

Department of Justice (2017) Retrieved from: https://www.justice.gov/file/923201/download

Ditrich H (2015) Cognitive fallacies and criminal investigations. Sci Justice 55:155–159

Dror IE (2009) How can Francis Bacon help forensic science? The four idols of human biases. Jurimetrics: The Journal of Law, Science, and Technology 50(1):93–110

Dror IE (2015) Cognitive neuroscience in forensic science: understanding and utilizing the human element. Philos Trans R Soc B 370(1674). https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2014.0255

Dror IE (2017) Human expert performance in forensic decision making: seven different sources of bias. Aust J Forensic Sci 49(5):541–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/00450618.2017.1281348

Dror IE (2020) Cognitive and human factors in expert decision making: six fallacies and the eight sources of bias. Anal Chem 92(12):7998–8004. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.analchem.0c00704

Dror IE, Morgan RM, Rando C, Nakhaeizadeh S (2017) Letter to the Editor: The bias snowball and the bias cascade effects: two distinct biases that may impact forensic decision making. J Forensic Sci 62(3):832–833. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.13496

Doyle JM (2012) Learning about learning from error. Police Foundation 14:1–16

Google Scholar

Doyle JM (2014) NIJ’s sentinel events initiative: looking back to look forward. National Institute of Justice Journal 273:10–14. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/244144.pdf

Eberhardt JL, Davies PG, Purdie-Vaughns VJ, Johnson SL (2006) Looking deathworthy: perceived stereotypicality of Black defendants predicts capital-sentencing outcomes. Psychol Sci 17(5):383–386. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01716.x

Eerland A, Post LS, Rassin E, Bouwmeester S, Zwaan RA (2012) Out of sight, out of mind: the presence of forensic evidence counts more than its absence. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 140(1):96–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2012.02.006

Eerland A, Rassin E (2012) Biased evaluation of incriminating and exonerating (non)evidence. Psychol Crime Law 18(4):351–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2010.493889

Fahsing I, Ask K (2013) Decision making and decisional tipping points in homicide investigations: an interview study of British and Norwegian detectives. J Investig Psychol Offender Profiling 10(2):155–165. https://doi.org/10.1002/jip.1384

Fahsing I, Ask K (2016) The making of an expert detective: the role of experience in English and Norwegian police officers’ investigative decision-making. Psychol Crime Law 22(3):203–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2015.1077249

Fahsing IA, Ask K (2017) In search of indicators of detective aptitude: police recruits’ logical reasoning and ability to generate investigative hypotheses. J Police Crim Psychol 33(1):21–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-017-9231-3

Findley KA (2012) Tunnel vision. In B. L. Cutler (Ed.), Conviction of the innocent: Lessons from psychological research (pp. 303–323). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13085-014

Fischhoff B (1975) Hindsight does not equal foresight: the effect of outcome knowledge on judgment under uncertainty. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform 1(3):288–299

Gilovich T, Griffin DW, Kahneman D (Eds.) (2002) Heuristics and biases: The psychology of intuitive judgment. Cambridge, U.K.; New York: Cambridge University Press

Greenspan R, Scurich N (2016) The interdependence of perceived confession voluntariness and case evidence. Law Hum Behav 40(6):650–659. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000200

Greenwald AG, McGhee DE, Schwartz JLK (1998) Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: the implicit association test. J Pers Soc Psychol 74(6):1464–1480

Groenendaal J, Helsloot I (2015) Tunnel vision on tunnel vision? A preliminary examination of the tension between precaution and efficacy in major criminal investigations in the Netherlands. Police Pract Res 16(3):224–238

Haas HS, Pisarzewska Fuerst M, Tönz P, Gubser-Ernst J (2015) Analyzing the psychological and social contents of evidence-experimental comparison between guessing, naturalistic observation, and systematic analysis. J Forensic Sci 60(3):659–668. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.12703

Hasel LE, Kassin SM (2009) On the presumption of evidentiary independence. Psychol Sci 20(1):122–126

Jones D, Grieve J, Milne B (2008) Reviewing the reviewers: a tool to aid homicide reviews. The Journal of Homicide and Major Incident Investigation 4(2):59–70

Kerstholt JH, Eikelboom AR (2007) Effects of prior interpretation on situation assessment in crime analysis. J Behav Decis Mak 20(5):455–465. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.570

MacFarlane BA (2008) Wrongful convictions: the effect of tunnel vision and predisposing circumstances in the criminal justice system. Goudge Inquiry Research Paper. https://www.attorneygeneral.jus.gov.on.ca/inquiries/goudge/policy_research/pdf/Macfarlane_Wrongful-Convictions.pdf

Marksteiner T, Ask K, Reinhard M-A, Granhag PA (2010) Asymmetrical scepticism towards criminal evidence: the role of goal- and belief-consistency. Appl Cogn Psychol 25(4):541–547. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1719

National Institute of Justice (2017) Retrieved from: https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/articles/sentinel-events-initiative

Nickerson RS (1998) Confirmation bias: a ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Rev Gen Psychol 2(2):175–220

NYCLU (2011) NYCLU Stop-And-Frisk Report 2011. New York Civil Liberties Union

O’Brien BM (2007) Confirmation bias in criminal investigations: an examination of the factors that aggravate and counteract bias. ProQuest Information & Learning, US. (2007–99016–280)

O’Brien B (2009) Prime suspect: an examination of factors that aggravate and counteract confirmation bias in criminal investigations. Psychol Public Policy Law 15(4):315–334. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017881

Owens E, Kerrison EM, Da Silveira BS (2017) Examining racial disparities in criminal case outcomes among indigent defendants in San Francisco. Quattrone Center for the Fair Administration of Justice

Owens E, Weisburd D, Amendola KL, Alpert GP (2018) Can you build a better cop?: Experimental evidence on supervision, training, and policing in the community. Criminol Public Policy 17(1):41–87. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/1745-9133.12337

Pearson AR, Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL (2009) The nature of contemporary prejudice: insights from aversive racism. Soc Pers Psychol Compass 3(3):314–338. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00183.x

Price HL, Dahl LC (2014) Order and strength matter for evaluation of alibi and eyewitness evidence: Recency effects. Appl Cogn Psychol 28(2):143–150. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.2983

Rassin E (2010) Blindness to alternative scenarios in evidence evaluation. J Investig Psychol Offender Profiling 7:153–163. https://doi.org/10.1002/jip.116

Rassin E (2018a) Fundamental failure to think logically about scientific questions: an illustration of tunnel vision with the application of Wason’s Card Selection Test to criminal evidence. Appl Cogn Psychol 32(4):506–511. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3417

Rassin E (2018b) Reducing tunnel vision with a pen-and-paper tool for the weighting of criminal evidence. J Investig Psychol Offender Profiling 15(2):227–233. https://doi.org/10.1002/jip.1504

Rassin E, Eerland A, Kuijpers I (2010) Let’s find the evidence: an analogue study of confirmation bias in criminal investigations. J Investig Psychol Offender Profiling 7:231–246

Richardson LS (2017) Systemic triage: Implicit racial bias in the criminal courtroom. Yale Law J 126(3):862–893

Rossmo DK, Pollock JM (2019) Confirmation bias and other systemic causes of wrongful convictions: a sentinel events perspective. Northeastern University Law Review 11(2):790–835

Salet R, Terpstra J (2014) Critical review in criminal investigation: evaluation of a measure to prevent tunnel vision. Policing 8(1):43–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/pat039

Simon D, Snow CJ, Read SJ (2004) The redux of cognitive consistency theories: evidence judgments by constraint satisfaction. J Pers Soc Psychol 86(6):814–837. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.86.6.814

Snook B, Cullen RM (2008) Bounded rationality and criminal investigations: has tunnel vision been wrongfully convicted? In D. K. Rossmo (Ed.), Criminal Investigative Failures (pp. 71–98). Taylor & Francis

Staats C, Capatosto K, Tenney L, Mamo S (2017) State of the science: implicit bias review. The Kirwan Institute

Stoel R, Berger C, Kerkhoff W, Mattijssen E, Dror I (2014) Minimizing contextual bias in forensic casework. In M. Hickman & K. Strom (Eds.), Forensic science and the administration of justice: Critical issues and directions (pp. 67–86). SAGE

Tversky A, Kahneman D (1973) Availability: a heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cogn Psychol 5:207–232

Tversky A, Kahneman D (1974) Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases. Science 185(4157):1124–1131

Voigt R, Camp NP, Prabhakaran V, Hamilton WL, Hetey RC, Griffiths CM, Eberhardt JL (2017) Language from police body camera footage shows racial disparities in officer respect. Proc Natl Acad Sci 114(25):6521–6526. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1702413114

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Wallace WA (2015) The effect of confirmation bias in criminal investigative decision making. ProQuest Information & Learning, US. (2016–17339–014)

Wastell C, Weeks N, Wearing A, Duncan P (2012) Identifying hypothesis confirmation behaviors in a simulated murder investigation: implications for practice. J Investig Psychol Offender Profiling 9:184–198

Zalman M, Larson M (2016) Elephants in the station house: Serial crimes, wrongful convictions, and expanding wrongful conviction analysis to include police investigation. Retrieved from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2716155

Zapf PA, Dror IE (2017) Understanding and mitigating bias in forensic evaluation: lessons from forensic science. Int J Forensic Ment Health 16(3):227–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/14999013.2017.1317302

Download references

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Dr. Karen Amendola (Police Foundation), Ms. Prahelika Gadtaula (Innocence Project), and Dr. Kim Rossmo (Texas State University) for their thoughtful reviews of earlier drafts.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Science & Research Department, Innocence Project, New York, NY, USA

Vanessa Meterko & Glinda Cooper

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Vanessa Meterko .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Statement

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by either of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix. Detailed Summary of 18 Studies with Police Participants or Source Materials

- a Homicide case vignette was the same as the others with this designation

- b Assault case vignette was the same as the others with this designation

- c Homicide case vignette was the same as the others with this designation

- d Missing person case vignettes were the same as others with this designation

- e The second study reported in this article used undergraduate student participants

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Meterko, V., Cooper, G. Cognitive Biases in Criminal Case Evaluation: A Review of the Research. J Police Crim Psych 37 , 101–122 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-020-09425-8

Download citation

Accepted : 08 December 2020

Published : 23 June 2021

Issue Date : March 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-020-09425-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Cognitive bias

- Confirmation bias

- Investigation

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Criminal Justice

- Most Cited Papers

- Most Downloaded Papers

- Newest Papers

- Save to Library

- Last »

- Criminal Law Follow Following

- Criminology Follow Following

- Law Follow Following

- Criminal Procedure Follow Following

- Crime Follow Following

- International Criminal Law Follow Following

- Critical Criminology Follow Following

- Philosophy of Criminal Law Follow Following

- Philosophy Of Law Follow Following

- Human Rights Follow Following

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- Academia.edu Publishing

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Criminal Justice Resources

Articles and papers/reports, selected books and law-related material, statistics/data, organizations, other sources, 50-state surveys, historical archives/research, what is happening in criminal justice, getting help, introduction.

This guide is meant to serve as a starting place for people researching criminal justice and related criminal law issues. It focuses primarly on issues related to the United States. For more criminal law sources (particularly for 1L's), be sure to check out our guides for Criminal Law and Law and Public Policy and the Kennedy School Library's Criminal Justice guide.

Subject Guide

Indexing/abstracting resources focused on criminal justice

- Crime and Delinquency Abstracts Covers 1963-1972. National Council on Crime and Delinquency and National Clearinghouse for Mental Health Information. Previously,

- Criminal Justice Abstracts (Harvard Key Login) Criminal Justice Abstracts provides comprehensive coverage of U.S. and international criminal justice literature including scholarly journals, books, dissertations, governmental and non-governmental studies and reports, unpublished papers, magazines, newsletters and other materials. In addition to criminal justice and criminology, topics covered include criminal law and procedure, corrections and prisons, police and policing, criminal investigation, forensic sciences and investigation, history of crime, substance abuse and addiction, and probation and parole. 1968-current. more... less... Criminal Justice Abstracts provides comprehensive coverage of U.S. and international criminal justice literature including scholarly journals, books, dissertations, governmental and non-governmental studies and reports, unpublished papers, magazines, newsletters and other materials. In addition to criminal justice and criminology, topics covered include criminal law and procedure, corrections and prisons, police and policing, criminal investigation, forensic sciences and investigation, history of crime, substance abuse and addiction, and probation and parole.

- NCJRS The National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS) is a federally funded resource offering justice and substance abuse information to support research, policy, and program development worldwide. The NCJRS Abstracts Database contains summaries of the more than 185,000 criminal justice publications housed in the NCJRS Library collection. Most documents published by NCJRS sponsoring agencies since 1995 are available in full-text online. A link is included with the abstract when the full-text is available. Use the Thesaurus Term Search to search for materials in the NCJRS Abstracts Database using an NCJRS controlled vocabulary. This controlled vocabulary is used to assign relevant indexing terms to the documents in the NCJRS collection.

Finding legal articles and papers

- Index to Legal Periodicals and Books

- Index to Legal Periodicals Retrospective: 1908-1981 (Law Login Required) covers back to 1908 more... less... This retrospective database indexes over 750 legal periodicals published in the United States, Canada, Great Britain, Ireland, Australia and New Zealand. Annual surveys of the laws of a jurisdiction, annual surveys of the federal courts, yearbooks, annual institutes, and annual reviews of the work in a given field or on a given topic will also be covered.

- More resources for finding legal articles

Multidisciplinary databases

- Academic Search Premier (Harvard Login) more... less... Academic Search Premier (ASP) is a multi-disciplinary database that includes citations and abstracts from over 4,700 scholarly publications (journals, magazines and newspapers). Full text is available for more than 3,600 of the publications and is searchable.

- JSTOR more... less... Includes all titles in the JSTOR collection, excluding recent issues. JSTOR (www.jstor.org) is a not-for-profit organization with a dual mission to create and maintain a trusted archive of important scholarly journals, and to provide access to these journals as widely as possible. Content in JSTOR spans many disciplines, primarily in the humanities and social sciences. For complete lists of titles and collections, please refer to http://www.jstor.org/about/collection.list.html.

Other social science databases related to criminal justice

- PAIS International (Harvard Login) provides access to materials about public policy, including academic journal articles, yearbooks, books, reports and pamphlets. Items indexed include works by academics, agencies, international organizations and federal, state and local governments from 1972 to the present. PAIS covers over 1,600 journals and roughly 8,000 books each year. PAIS is international in scope and contains items in many romance languages. more... less... PAIS International indexes the public and social policy literature of public administration, political science, economics, finance, international relations, law, and health care, International in scope, PAIS indexes publications in English, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish. The database is comprised of abstracts of thousands of journal articles, books, directories, conference proceedings, government documents and statistical yearbooks.

- More academic resources by field

- Law and Public Policy Guide

- Urban Studies Abstracts (Harvard Login) more... less... Electronic index and abstracts to the literature in the area of urban studies, including urban affairs, community development, and urban history. The backfile of this index has been digitized, providing coverage back to 1973.

Selected Journals and newsletters

- Annual Review of Criminal Procedure (Georgetown) Latest issue available in print at Law School KF9619 .G46

- Federal Sentencing Reporter also on Lexis

Congressional publications/government reports

- CRS reports

- House and Senate Hearings, Congressional Record Permanent Digital Collection, and Digital US Bills and Resolutions

- Federal Legislative History

- US Department of Justice

- PolicyFile (Harvard Login) Abstracts of and links to domestic and international public policy issue published by think tanks, university research programs, & research organizations. more... less... PolicyFile provides abstracts (more than half of the abstracts link to the full text documents) of domestic and international public policy issues. The public policy reports and studies are published by think tanks, university research programs, research organizations which include the OECD, IMF, World Bank, the Rand Corporation, and a number of federal agencies. The database search engine allows users to search by title, author, subject, organization and keyword.

- Rutgers University Don M. Gottsfredson School of Criminal Justice Gray Literature Database

Rules of Criminal Procedure

- Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure (Federal Rules of Practice & Procedure) Includes postings of proposed rule changes. From the uscourts.gov website.

- Rulemaking (Pending Rules)(US Courts)

Model Penal Code

- Criminal Law: Model Penal Code

- Model Penal Code and Commentaries (official draft and revised comments) : with text of Model penal code as adopted at the 1962 Annual Meeting of the American Law Institute at Washington, D.C., May 24, 1962.

- Model penal code : official draft and explanatory notes : complete text of Model penal code as adopted at the 1962 Annual Meeting of the American Law Institute at Washington, D.C., May 24, 1962.

- Model Penal Code (ALI Library) Includes drafts

Selected Criminal Law Treatises, Basic Texts and Practice Manuals

Below are sources related to criminal law generally or focused on federal criminal law. For a particular jurisdiction, look for secondary sources related to that particular state. For constitutional issues, see also secondary sources related to constitutional law more generally.

- United States Attorneys Manual

- Legal Division Reference Book

- United States Sentencing Commission, Guidelines Manual

Search and Seizure

- Search and Seizure also on Lexis

Sources for criminal justice statistics generally

- Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics Currently in transition (no longer funded by the Bureau of Justice Statistics), but still a good starting place. Data included as of 2013.

- Bureau of Justice Statistics

- FBI Uniform Crime Reports Annual report is Crime in the United States .

- National Crime Victimization Survey See also NCVS Victimization Analysis Tool and National Crime Victimization Survey Resource Guide .

- Justice Research and Statistics Association

- National Archive of Criminal Justice Data

- United States Sentencing Commission (USSC) Interactive Sourcebook

- Sunlight Criminal Justice Project Its Hall of Justice provides a searchable inventory of publically available criminal justice data sets and research.

- Arrest Data Analysis Tool underlying data from FBI's UCR (Uniform Crime Reports)

- Measures for Justice

- State Criminal Caseloads

- United States Historical Corrections Statistics - 1850-1984 from BJS abstract: "The introductory chapter contains a brief history of Federal corrections data collection efforts. Summary information on capital punishment includes data on illegal lynchings by race and offense, regional comparisons of the number of persons executed, the number under the death sentence, the number of women executed, and the number of persons removed from the death sentence other than by execution. Prison statistics cover the number in Federal, State, and juvenile facilities; the average sentence by sex, region, race, and offense; length of sentence; and type of release. Statistics also cover facility staff, inmate-staff ratio, and jail inmates. Probation and parole statistics address the numbers under supervision (both adults and juveniles), average caseload, terminations by method of termination, the average length of parole and percent with favorable outcome, and probationer and parolee profiles. Implications are drawn for current data collection efforts, and the appendix contains limited information on military prisons."

- Crime Solutions.gov

Crime Mapping

- NIJ Mapping and Analysis for Public Safety

Specialized sources of statistics/data

- Death Penalty Information Center

- Federal Sentencing Statistics

- The Counted: People Killed by Police in the US (The Guardian)

- Washington Post (People Shot Dead by Police)

- Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Protection's (OJJDP's) Statistical Briefing Book

- Stanford Open Policing Project Data on vehicle and pedestrian stops from law enforcement departments across the country.

- Corporate Prosecution Registry

- Police Crime Data

- Monitoring of Federal Criminal Sentences Series

- Citizen Police Data Project focused on Chicago

- Chicago Data Collaborative "Collaborative members collect data from institutions at all points of contact in the Cook County criminal justice system, including the Chicago Police Department, the Illinois State Police, the Office of the State's Attorney, and the Cook County Jail."

- Washington Post (Unsolved Homicide Database)

- American Violence Run by the NYU Marron Institute of Urban Management, the initial iteration of this databases includes city-level figures on murder rates in more than 80 of the largest 100 U.S. cities. According to the website, the second iteration will feature neighborhood-level figures on violent crime in 30-50 cities with available data.

- Police Data Initiative "This site provides a consolidated and interactive listing of open and soon-to-be-opened data sets that more than 130 local law enforcement agencies have identified as important to their communities, and provides critical and timely resources, including technical guidance and best practices, success stories, how-to articles and links to related efforts." See map of participating agencies" .

Other sources for statistics

- American Fact Finder

- See Judicial Workload, Jury Verdicts and Crime Statistics generally

- Harvard Dataverse more... less... The Harvard-MIT Data Center is the principal repository of quantitative social science data at Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The majority of its holdings are available to Harvard and MIT affiliates directly via its web site through its search engine. Graduate students and faculty with a Harvard or MIT Library card can check out paper code books from libraries at either institution, under Harvard's and MIT's reciprocal borrowing agreement. In addition, the Data Center has negotiated a special agreement for undergraduates and summer graduate students, who are not covered by the standard agreement.

- Proquest Statistical Insight (Harvard Login) more... less... Proquest Statistical Insight is a bibliographic database that indexes and abstracts the statistical content of selected United States government publications, state government publications, business and association publications, and intergovernmental publications. The abstracts may also contain a link to the full text of the table and/or a link to the agency's web site where the full text of the publication may be viewed and downloaded.

- Data.gov Includes data from the Department of Justice and other agencies.

- Data Citation Index (Web of Science)

- Historical Statistics of the United States (Harvard Login) more... less... Presents the U.S. in statistics from Colonial times to the present. Included are statistics on U.S. population, including characteristics, vital statistics, internal and international migration. Statistics on work and welfare, economic structure and performance, economic sectors, and governance and international relations. Tables may be downloaded for use in spreadsheets and other applications. This electronic database is also in a five volume hard copy set.

Books, reports and articles about criminal justice statistics and records

- Data and Civil Rights: Criminal Justice Primer Part of larger conference on Data and Civil Rights http://www.datacivilrights.org/ ; includes write-up from conference http://www.datacivilrights.org/pubs/2014-1030/CriminalJustice-Writeup.pdf

- Ensuring the Quality, Credibility, and Relevance of U.S. Justice Statistics (2009)

- Estimating the Incidence of Rape and Sexual Assault

- Modernizing Crime Statistics: Report 1: Defining and Classifying Crime

Case Processing and Court Statistics

- Federal Criminal Case Processing Statistics

- State Court Caseload Statistics See also Data Collection: Court Statistics Project and CSP Data Viewer .

- Statistics and Reports (Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts)

Criminal Records

- Search Systems A mega search site with links to public records by state, county, city and also by record type. A great place to start your research. more... less... From the website: We've located, analyzed, described, and organized links to over 55,000 databases by type and location to help you find property, criminal, court, birth, death, marriage, divorce records, licenses, deeds, mortgages, corporate records, business registration, and many other public record resources quickly, easily, and for free.

- BRB Publications BRB Publications maintains a page with links to more than 300 local, state and federal websites offering free access to public records.

- National Sex Offender Public Registry From the US Department of Justice. This site also has links to all 50 states, District of Columbia, US territories, and tribal registry websites.

- FBI's Sex Offender Database websites An alternate source for state level sex offender databases.

- FBI's Bureau of Prisons Inmate Finder

- VINELink VINELink is the online version of VINE (Victim Information and Notification Everyday), the National Victim Notification Network. This service allows crime victims to obtain timely and reliable information about criminal cases and the custody status of offenders 24 hours a day.

Research Organizations and Advocacy Groups

- Vera Institute of Justice

- Agencies, Think Tanks and Advocacy Groups

- Urban Institute-Crime and Justice

- National Center for State Courts

- National Conference of State Legislatures

- Innocence Project

- Quattrone Center for the Fair Administration of Justice (UPenn Law)

- Capital Jury Project

Professional Organizations

- American Bar Association (Criminal Justice section)

- National District Attorneys Association

- American Correctional Association

- National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers

Research guides from other libraries

- MSU Libraries, Criminal Justice Resources

- Georgetown Law Criminal Law and Justice Guide

- Harvard Kennedy School Library, Criminal Justice

- Criminal Law Prof Blog

- White Collar Crime Prof Blog

50-State-Surveys

- ABA Collateral Consequences Database

- National Conference of State Legislatures-Civil and Criminal Justice

HIstorical Archives/Projects

- National Death Penalty Archives

- ProQuest History Vault (Harvard Login)

Updates from popular criminal justice resources

New books in the library, new books in general.

- New Books Received at Rutgers

Ask Us! Submit a question or search the knowledge base.

Call Reference Desk, 617-495-4516

Text Ask a Librarian, 617-702-2728

Email research @law.harvard.edu

Meet Consult a Librarian

Classes View Training Calendar or Request an Insta-Class

Visit Us Library and Reference Hours

- Last Updated: Apr 12, 2024 4:50 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/criminaljustice

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Reflections on Criminal Justice Reform: Challenges and Opportunities

Pamela k. lattimore.

RTI International, 3040 East Cornwallis Road, Research Triangle Park, NC 27703 USA

Associated Data

Data are cited from a variety of sources. Much of the BJS data cited are available from the National Archive of Criminal Justice Data, Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research. The SVORI data and the Second Chance Act AORDP data are also available from NACJD.

Considerable efforts and resources have been expended to enact reforms to the criminal justice system over the last five decades. Concerns about dramatic increases in violent crime beginning in the late Sixties and accelerating into the 1980s led to the “War on Drugs” and the “War on Crime” that included implementation of more punitive policies and dramatic increases in incarceration and community supervision. More recent reform efforts have focused on strategies to reduce the negative impacts of policing, the disparate impacts of pretrial practices, and better strategies for reducing criminal behavior. Renewed interest in strategies and interventions to reduce criminal behavior has coincided with a focus on identifying “what works.” Recent increases in violence have shifted the national dialog from a focus on progressive reforms to reduce reliance on punitive measures and the disparate impact of the legal system on some groups to a focus on increased investment in “tough on crime” criminal justice approaches. This essay offers some reflections on the “Waged Wars” and the efforts to identify “What Works” based on nearly 40 years of work evaluating criminal justice reform efforts.

The last fifty-plus years have seen considerable efforts and resources expended to enact reforms to the criminal justice system. Some of the earliest reforms of this era were driven by dramatic increases in violence leading to more punitive policies. More recently, reform efforts have focused on strategies to reduce the negative impacts of policing, the disparate impacts of pretrial practices, and better strategies for reducing criminal behavior. Renewed interest in strategies and interventions to reduce criminal behavior has coincided with a focus on identifying “what works.” Recent increases in violence have shifted the national dialog about reform. The shift may be due to the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 epidemic or concerns about the United States returning to the escalating rise in violence and homicide in the 1980s and 1990s. Whichever proves true, the current rise of violence, at a minimum, has changed the tenor of policymaker discussions, from a focus on progressive reforms to reduce reliance on punitive measures and the disparate impact of the legal system on some groups to a focus on increased investment in “tough on crime” criminal justice approaches.

It is, then, an interesting time for those concerned about justice in America. Countervailing forces are at play that have generated a consistent call for reform, but with profound differences in views about what reform should entail. The impetus for reform is myriad: Concerns about the deaths of Black Americans by law enforcement agencies and officers who may employ excessive use of force with minorities; pressures to reduce pretrial incarceration that results in crowded jails and detention of those who have not been found guilty; prison incarcerations rates that remain the highest in the Western world; millions of individuals who live under community supervision and the burden of fees and fines that they will never be able to pay; and, in the aftermath of the worst pandemic in more than a century, increasing violence, particularly homicides and gun violence. This last change has led to fear and demands for action from communities under threat, but it exists alongside of other changes that point to the need for progressive changes rather than reversion to, or greater investment in, get-tough policies.

How did we get here? What have we learned from more than 50 years of efforts at reform? How can we do better? In this essay, I offer some reflections based on my nearly 40 years of evaluating criminal justice reform efforts. 1

Part I: Waging “War”