Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write a literary analysis essay | A step-by-step guide

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay | A Step-by-Step Guide

Published on January 30, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on August 14, 2023.

Literary analysis means closely studying a text, interpreting its meanings, and exploring why the author made certain choices. It can be applied to novels, short stories, plays, poems, or any other form of literary writing.

A literary analysis essay is not a rhetorical analysis , nor is it just a summary of the plot or a book review. Instead, it is a type of argumentative essay where you need to analyze elements such as the language, perspective, and structure of the text, and explain how the author uses literary devices to create effects and convey ideas.

Before beginning a literary analysis essay, it’s essential to carefully read the text and c ome up with a thesis statement to keep your essay focused. As you write, follow the standard structure of an academic essay :

- An introduction that tells the reader what your essay will focus on.

- A main body, divided into paragraphs , that builds an argument using evidence from the text.

- A conclusion that clearly states the main point that you have shown with your analysis.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: reading the text and identifying literary devices, step 2: coming up with a thesis, step 3: writing a title and introduction, step 4: writing the body of the essay, step 5: writing a conclusion, other interesting articles.

The first step is to carefully read the text(s) and take initial notes. As you read, pay attention to the things that are most intriguing, surprising, or even confusing in the writing—these are things you can dig into in your analysis.

Your goal in literary analysis is not simply to explain the events described in the text, but to analyze the writing itself and discuss how the text works on a deeper level. Primarily, you’re looking out for literary devices —textual elements that writers use to convey meaning and create effects. If you’re comparing and contrasting multiple texts, you can also look for connections between different texts.

To get started with your analysis, there are several key areas that you can focus on. As you analyze each aspect of the text, try to think about how they all relate to each other. You can use highlights or notes to keep track of important passages and quotes.

Language choices

Consider what style of language the author uses. Are the sentences short and simple or more complex and poetic?

What word choices stand out as interesting or unusual? Are words used figuratively to mean something other than their literal definition? Figurative language includes things like metaphor (e.g. “her eyes were oceans”) and simile (e.g. “her eyes were like oceans”).

Also keep an eye out for imagery in the text—recurring images that create a certain atmosphere or symbolize something important. Remember that language is used in literary texts to say more than it means on the surface.

Narrative voice

Ask yourself:

- Who is telling the story?

- How are they telling it?

Is it a first-person narrator (“I”) who is personally involved in the story, or a third-person narrator who tells us about the characters from a distance?

Consider the narrator’s perspective . Is the narrator omniscient (where they know everything about all the characters and events), or do they only have partial knowledge? Are they an unreliable narrator who we are not supposed to take at face value? Authors often hint that their narrator might be giving us a distorted or dishonest version of events.

The tone of the text is also worth considering. Is the story intended to be comic, tragic, or something else? Are usually serious topics treated as funny, or vice versa ? Is the story realistic or fantastical (or somewhere in between)?

Consider how the text is structured, and how the structure relates to the story being told.

- Novels are often divided into chapters and parts.

- Poems are divided into lines, stanzas, and sometime cantos.

- Plays are divided into scenes and acts.

Think about why the author chose to divide the different parts of the text in the way they did.

There are also less formal structural elements to take into account. Does the story unfold in chronological order, or does it jump back and forth in time? Does it begin in medias res —in the middle of the action? Does the plot advance towards a clearly defined climax?

With poetry, consider how the rhyme and meter shape your understanding of the text and your impression of the tone. Try reading the poem aloud to get a sense of this.

In a play, you might consider how relationships between characters are built up through different scenes, and how the setting relates to the action. Watch out for dramatic irony , where the audience knows some detail that the characters don’t, creating a double meaning in their words, thoughts, or actions.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Your thesis in a literary analysis essay is the point you want to make about the text. It’s the core argument that gives your essay direction and prevents it from just being a collection of random observations about a text.

If you’re given a prompt for your essay, your thesis must answer or relate to the prompt. For example:

Essay question example

Is Franz Kafka’s “Before the Law” a religious parable?

Your thesis statement should be an answer to this question—not a simple yes or no, but a statement of why this is or isn’t the case:

Thesis statement example

Franz Kafka’s “Before the Law” is not a religious parable, but a story about bureaucratic alienation.

Sometimes you’ll be given freedom to choose your own topic; in this case, you’ll have to come up with an original thesis. Consider what stood out to you in the text; ask yourself questions about the elements that interested you, and consider how you might answer them.

Your thesis should be something arguable—that is, something that you think is true about the text, but which is not a simple matter of fact. It must be complex enough to develop through evidence and arguments across the course of your essay.

Say you’re analyzing the novel Frankenstein . You could start by asking yourself:

Your initial answer might be a surface-level description:

The character Frankenstein is portrayed negatively in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein .

However, this statement is too simple to be an interesting thesis. After reading the text and analyzing its narrative voice and structure, you can develop the answer into a more nuanced and arguable thesis statement:

Mary Shelley uses shifting narrative perspectives to portray Frankenstein in an increasingly negative light as the novel goes on. While he initially appears to be a naive but sympathetic idealist, after the creature’s narrative Frankenstein begins to resemble—even in his own telling—the thoughtlessly cruel figure the creature represents him as.

Remember that you can revise your thesis statement throughout the writing process , so it doesn’t need to be perfectly formulated at this stage. The aim is to keep you focused as you analyze the text.

Finding textual evidence

To support your thesis statement, your essay will build an argument using textual evidence —specific parts of the text that demonstrate your point. This evidence is quoted and analyzed throughout your essay to explain your argument to the reader.

It can be useful to comb through the text in search of relevant quotations before you start writing. You might not end up using everything you find, and you may have to return to the text for more evidence as you write, but collecting textual evidence from the beginning will help you to structure your arguments and assess whether they’re convincing.

To start your literary analysis paper, you’ll need two things: a good title, and an introduction.

Your title should clearly indicate what your analysis will focus on. It usually contains the name of the author and text(s) you’re analyzing. Keep it as concise and engaging as possible.

A common approach to the title is to use a relevant quote from the text, followed by a colon and then the rest of your title.

If you struggle to come up with a good title at first, don’t worry—this will be easier once you’ve begun writing the essay and have a better sense of your arguments.

“Fearful symmetry” : The violence of creation in William Blake’s “The Tyger”

The introduction

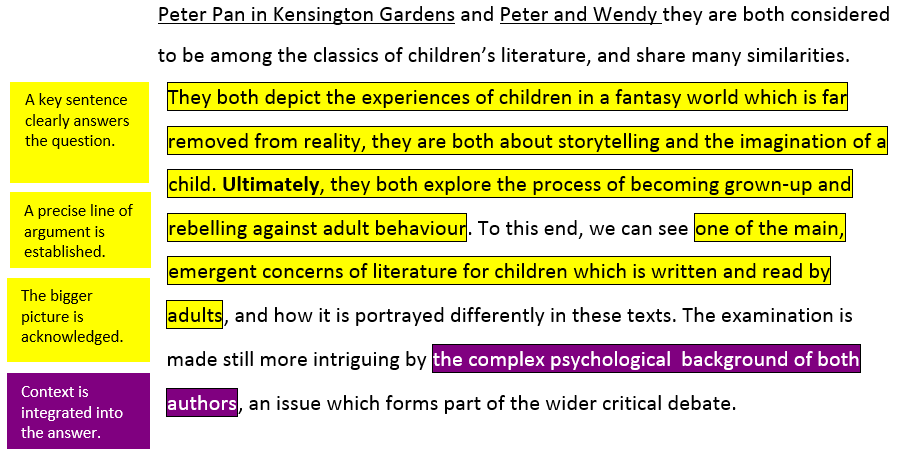

The essay introduction provides a quick overview of where your argument is going. It should include your thesis statement and a summary of the essay’s structure.

A typical structure for an introduction is to begin with a general statement about the text and author, using this to lead into your thesis statement. You might refer to a commonly held idea about the text and show how your thesis will contradict it, or zoom in on a particular device you intend to focus on.

Then you can end with a brief indication of what’s coming up in the main body of the essay. This is called signposting. It will be more elaborate in longer essays, but in a short five-paragraph essay structure, it shouldn’t be more than one sentence.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is often read as a crude cautionary tale about the dangers of scientific advancement unrestrained by ethical considerations. In this reading, protagonist Victor Frankenstein is a stable representation of the callous ambition of modern science throughout the novel. This essay, however, argues that far from providing a stable image of the character, Shelley uses shifting narrative perspectives to portray Frankenstein in an increasingly negative light as the novel goes on. While he initially appears to be a naive but sympathetic idealist, after the creature’s narrative Frankenstein begins to resemble—even in his own telling—the thoughtlessly cruel figure the creature represents him as. This essay begins by exploring the positive portrayal of Frankenstein in the first volume, then moves on to the creature’s perception of him, and finally discusses the third volume’s narrative shift toward viewing Frankenstein as the creature views him.

Some students prefer to write the introduction later in the process, and it’s not a bad idea. After all, you’ll have a clearer idea of the overall shape of your arguments once you’ve begun writing them!

If you do write the introduction first, you should still return to it later to make sure it lines up with what you ended up writing, and edit as necessary.

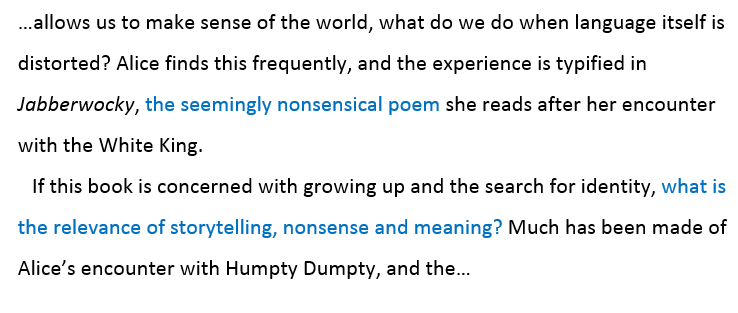

The body of your essay is everything between the introduction and conclusion. It contains your arguments and the textual evidence that supports them.

Paragraph structure

A typical structure for a high school literary analysis essay consists of five paragraphs : the three paragraphs of the body, plus the introduction and conclusion.

Each paragraph in the main body should focus on one topic. In the five-paragraph model, try to divide your argument into three main areas of analysis, all linked to your thesis. Don’t try to include everything you can think of to say about the text—only analysis that drives your argument.

In longer essays, the same principle applies on a broader scale. For example, you might have two or three sections in your main body, each with multiple paragraphs. Within these sections, you still want to begin new paragraphs at logical moments—a turn in the argument or the introduction of a new idea.

Robert’s first encounter with Gil-Martin suggests something of his sinister power. Robert feels “a sort of invisible power that drew me towards him.” He identifies the moment of their meeting as “the beginning of a series of adventures which has puzzled myself, and will puzzle the world when I am no more in it” (p. 89). Gil-Martin’s “invisible power” seems to be at work even at this distance from the moment described; before continuing the story, Robert feels compelled to anticipate at length what readers will make of his narrative after his approaching death. With this interjection, Hogg emphasizes the fatal influence Gil-Martin exercises from his first appearance.

Topic sentences

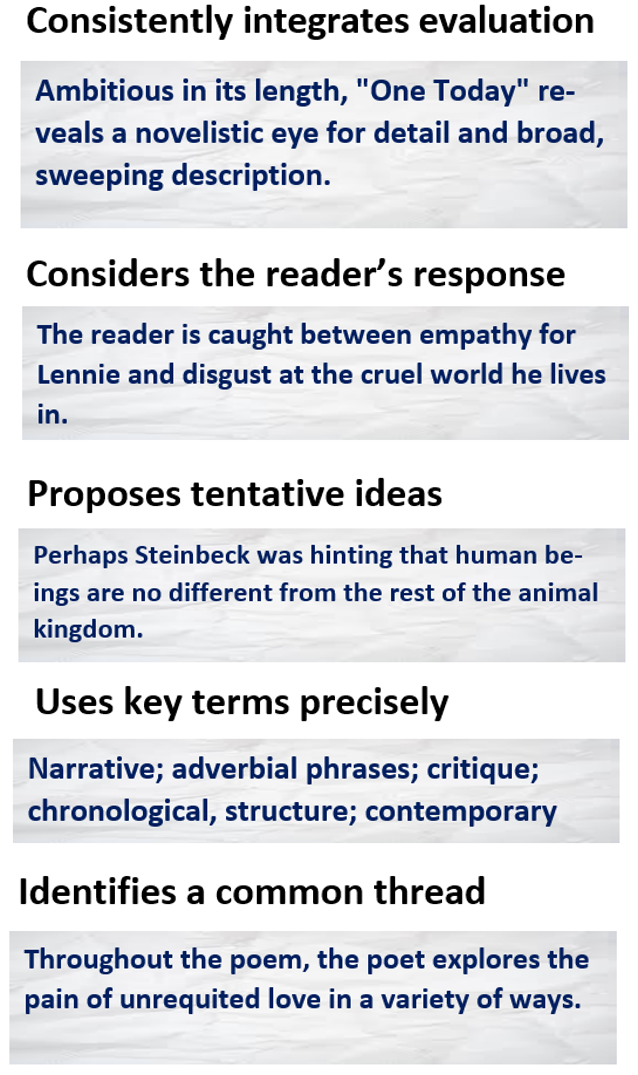

To keep your points focused, it’s important to use a topic sentence at the beginning of each paragraph.

A good topic sentence allows a reader to see at a glance what the paragraph is about. It can introduce a new line of argument and connect or contrast it with the previous paragraph. Transition words like “however” or “moreover” are useful for creating smooth transitions:

… The story’s focus, therefore, is not upon the divine revelation that may be waiting beyond the door, but upon the mundane process of aging undergone by the man as he waits.

Nevertheless, the “radiance” that appears to stream from the door is typically treated as religious symbolism.

This topic sentence signals that the paragraph will address the question of religious symbolism, while the linking word “nevertheless” points out a contrast with the previous paragraph’s conclusion.

Using textual evidence

A key part of literary analysis is backing up your arguments with relevant evidence from the text. This involves introducing quotes from the text and explaining their significance to your point.

It’s important to contextualize quotes and explain why you’re using them; they should be properly introduced and analyzed, not treated as self-explanatory:

It isn’t always necessary to use a quote. Quoting is useful when you’re discussing the author’s language, but sometimes you’ll have to refer to plot points or structural elements that can’t be captured in a short quote.

In these cases, it’s more appropriate to paraphrase or summarize parts of the text—that is, to describe the relevant part in your own words:

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

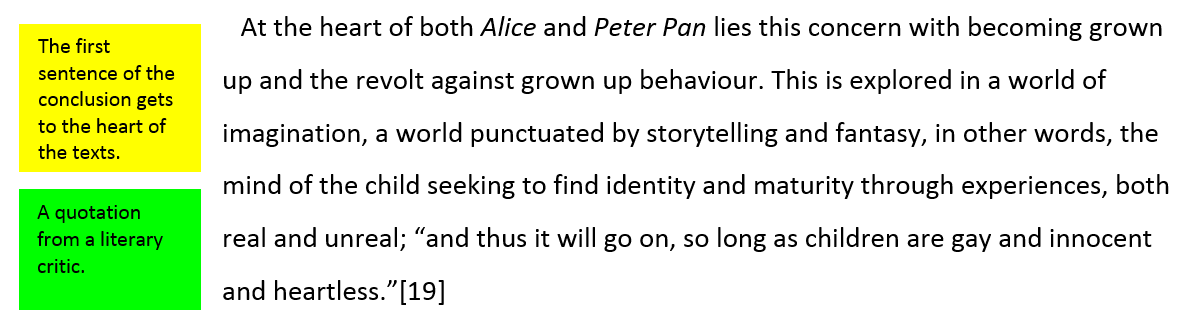

The conclusion of your analysis shouldn’t introduce any new quotations or arguments. Instead, it’s about wrapping up the essay. Here, you summarize your key points and try to emphasize their significance to the reader.

A good way to approach this is to briefly summarize your key arguments, and then stress the conclusion they’ve led you to, highlighting the new perspective your thesis provides on the text as a whole:

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

By tracing the depiction of Frankenstein through the novel’s three volumes, I have demonstrated how the narrative structure shifts our perception of the character. While the Frankenstein of the first volume is depicted as having innocent intentions, the second and third volumes—first in the creature’s accusatory voice, and then in his own voice—increasingly undermine him, causing him to appear alternately ridiculous and vindictive. Far from the one-dimensional villain he is often taken to be, the character of Frankenstein is compelling because of the dynamic narrative frame in which he is placed. In this frame, Frankenstein’s narrative self-presentation responds to the images of him we see from others’ perspectives. This conclusion sheds new light on the novel, foregrounding Shelley’s unique layering of narrative perspectives and its importance for the depiction of character.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, August 14). How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay | A Step-by-Step Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved April 5, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/literary-analysis/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write a thesis statement | 4 steps & examples, academic paragraph structure | step-by-step guide & examples, how to write a narrative essay | example & tips, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

beginner's guide to literary analysis

Understanding literature & how to write literary analysis.

Literary analysis is the foundation of every college and high school English class. Once you can comprehend written work and respond to it, the next step is to learn how to think critically and complexly about a work of literature in order to analyze its elements and establish ideas about its meaning.

If that sounds daunting, it shouldn’t. Literary analysis is really just a way of thinking creatively about what you read. The practice takes you beyond the storyline and into the motives behind it.

While an author might have had a specific intention when they wrote their book, there’s still no right or wrong way to analyze a literary text—just your way. You can use literary theories, which act as “lenses” through which you can view a text. Or you can use your own creativity and critical thinking to identify a literary device or pattern in a text and weave that insight into your own argument about the text’s underlying meaning.

Now, if that sounds fun, it should , because it is. Here, we’ll lay the groundwork for performing literary analysis, including when writing analytical essays, to help you read books like a critic.

What Is Literary Analysis?

As the name suggests, literary analysis is an analysis of a work, whether that’s a novel, play, short story, or poem. Any analysis requires breaking the content into its component parts and then examining how those parts operate independently and as a whole. In literary analysis, those parts can be different devices and elements—such as plot, setting, themes, symbols, etcetera—as well as elements of style, like point of view or tone.

When performing analysis, you consider some of these different elements of the text and then form an argument for why the author chose to use them. You can do so while reading and during class discussion, but it’s particularly important when writing essays.

Literary analysis is notably distinct from summary. When you write a summary , you efficiently describe the work’s main ideas or plot points in order to establish an overview of the work. While you might use elements of summary when writing analysis, you should do so minimally. You can reference a plot line to make a point, but it should be done so quickly so you can focus on why that plot line matters . In summary (see what we did there?), a summary focuses on the “ what ” of a text, while analysis turns attention to the “ how ” and “ why .”

While literary analysis can be broad, covering themes across an entire work, it can also be very specific, and sometimes the best analysis is just that. Literary critics have written thousands of words about the meaning of an author’s single word choice; while you might not want to be quite that particular, there’s a lot to be said for digging deep in literary analysis, rather than wide.

Although you’re forming your own argument about the work, it’s not your opinion . You should avoid passing judgment on the piece and instead objectively consider what the author intended, how they went about executing it, and whether or not they were successful in doing so. Literary criticism is similar to literary analysis, but it is different in that it does pass judgement on the work. Criticism can also consider literature more broadly, without focusing on a singular work.

Once you understand what constitutes (and doesn’t constitute) literary analysis, it’s easy to identify it. Here are some examples of literary analysis and its oft-confused counterparts:

Summary: In “The Fall of the House of Usher,” the narrator visits his friend Roderick Usher and witnesses his sister escape a horrible fate.

Opinion: In “The Fall of the House of Usher,” Poe uses his great Gothic writing to establish a sense of spookiness that is enjoyable to read.

Literary Analysis: “Throughout ‘The Fall of the House of Usher,’ Poe foreshadows the fate of Madeline by creating a sense of claustrophobia for the reader through symbols, such as in the narrator’s inability to leave and the labyrinthine nature of the house.

In summary, literary analysis is:

- Breaking a work into its components

- Identifying what those components are and how they work in the text

- Developing an understanding of how they work together to achieve a goal

- Not an opinion, but subjective

- Not a summary, though summary can be used in passing

- Best when it deeply, rather than broadly, analyzes a literary element

Literary Analysis and Other Works

As discussed above, literary analysis is often performed upon a single work—but it doesn’t have to be. It can also be performed across works to consider the interplay of two or more texts. Regardless of whether or not the works were written about the same thing, or even within the same time period, they can have an influence on one another or a connection that’s worth exploring. And reading two or more texts side by side can help you to develop insights through comparison and contrast.

For example, Paradise Lost is an epic poem written in the 17th century, based largely on biblical narratives written some 700 years before and which later influenced 19th century poet John Keats. The interplay of works can be obvious, as here, or entirely the inspiration of the analyst. As an example of the latter, you could compare and contrast the writing styles of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Edgar Allan Poe who, while contemporaries in terms of time, were vastly different in their content.

Additionally, literary analysis can be performed between a work and its context. Authors are often speaking to the larger context of their times, be that social, political, religious, economic, or artistic. A valid and interesting form is to compare the author’s context to the work, which is done by identifying and analyzing elements that are used to make an argument about the writer’s time or experience.

For example, you could write an essay about how Hemingway’s struggles with mental health and paranoia influenced his later work, or how his involvement in the Spanish Civil War influenced his early work. One approach focuses more on his personal experience, while the other turns to the context of his times—both are valid.

Why Does Literary Analysis Matter?

Sometimes an author wrote a work of literature strictly for entertainment’s sake, but more often than not, they meant something more. Whether that was a missive on world peace, commentary about femininity, or an allusion to their experience as an only child, the author probably wrote their work for a reason, and understanding that reason—or the many reasons—can actually make reading a lot more meaningful.

Performing literary analysis as a form of study unquestionably makes you a better reader. It’s also likely that it will improve other skills, too, like critical thinking, creativity, debate, and reasoning.

At its grandest and most idealistic, literary analysis even has the ability to make the world a better place. By reading and analyzing works of literature, you are able to more fully comprehend the perspectives of others. Cumulatively, you’ll broaden your own perspectives and contribute more effectively to the things that matter to you.

Literary Terms to Know for Literary Analysis

There are hundreds of literary devices you could consider during your literary analysis, but there are some key tools most writers utilize to achieve their purpose—and therefore you need to know in order to understand that purpose. These common devices include:

- Characters: The people (or entities) who play roles in the work. The protagonist is the main character in the work.

- Conflict: The conflict is the driving force behind the plot, the event that causes action in the narrative, usually on the part of the protagonist

- Context : The broader circumstances surrounding the work political and social climate in which it was written or the experience of the author. It can also refer to internal context, and the details presented by the narrator

- Diction : The word choice used by the narrator or characters

- Genre: A category of literature characterized by agreed upon similarities in the works, such as subject matter and tone

- Imagery : The descriptive or figurative language used to paint a picture in the reader’s mind so they can picture the story’s plot, characters, and setting

- Metaphor: A figure of speech that uses comparison between two unlike objects for dramatic or poetic effect

- Narrator: The person who tells the story. Sometimes they are a character within the story, but sometimes they are omniscient and removed from the plot.

- Plot : The storyline of the work

- Point of view: The perspective taken by the narrator, which skews the perspective of the reader

- Setting : The time and place in which the story takes place. This can include elements like the time period, weather, time of year or day, and social or economic conditions

- Symbol : An object, person, or place that represents an abstract idea that is greater than its literal meaning

- Syntax : The structure of a sentence, either narration or dialogue, and the tone it implies

- Theme : A recurring subject or message within the work, often commentary on larger societal or cultural ideas

- Tone : The feeling, attitude, or mood the text presents

How to Perform Literary Analysis

Step 1: read the text thoroughly.

Literary analysis begins with the literature itself, which means performing a close reading of the text. As you read, you should focus on the work. That means putting away distractions (sorry, smartphone) and dedicating a period of time to the task at hand.

It’s also important that you don’t skim or speed read. While those are helpful skills, they don’t apply to literary analysis—or at least not this stage.

Step 2: Take Notes as You Read

As you read the work, take notes about different literary elements and devices that stand out to you. Whether you highlight or underline in text, use sticky note tabs to mark pages and passages, or handwrite your thoughts in a notebook, you should capture your thoughts and the parts of the text to which they correspond. This—the act of noticing things about a literary work—is literary analysis.

Step 3: Notice Patterns

As you read the work, you’ll begin to notice patterns in the way the author deploys language, themes, and symbols to build their plot and characters. As you read and these patterns take shape, begin to consider what they could mean and how they might fit together.

As you identify these patterns, as well as other elements that catch your interest, be sure to record them in your notes or text. Some examples include:

- Circle or underline words or terms that you notice the author uses frequently, whether those are nouns (like “eyes” or “road”) or adjectives (like “yellow” or “lush”).

- Highlight phrases that give you the same kind of feeling. For example, if the narrator describes an “overcast sky,” a “dreary morning,” and a “dark, quiet room,” the words aren’t the same, but the feeling they impart and setting they develop are similar.

- Underline quotes or prose that define a character’s personality or their role in the text.

- Use sticky tabs to color code different elements of the text, such as specific settings or a shift in the point of view.

By noting these patterns, comprehensive symbols, metaphors, and ideas will begin to come into focus.

Step 4: Consider the Work as a Whole, and Ask Questions

This is a step that you can do either as you read, or after you finish the text. The point is to begin to identify the aspects of the work that most interest you, and you could therefore analyze in writing or discussion.

Questions you could ask yourself include:

- What aspects of the text do I not understand?

- What parts of the narrative or writing struck me most?

- What patterns did I notice?

- What did the author accomplish really well?

- What did I find lacking?

- Did I notice any contradictions or anything that felt out of place?

- What was the purpose of the minor characters?

- What tone did the author choose, and why?

The answers to these and more questions will lead you to your arguments about the text.

Step 5: Return to Your Notes and the Text for Evidence

As you identify the argument you want to make (especially if you’re preparing for an essay), return to your notes to see if you already have supporting evidence for your argument. That’s why it’s so important to take notes or mark passages as you read—you’ll thank yourself later!

If you’re preparing to write an essay, you’ll use these passages and ideas to bolster your argument—aka, your thesis. There will likely be multiple different passages you can use to strengthen multiple different aspects of your argument. Just be sure to cite the text correctly!

If you’re preparing for class, your notes will also be invaluable. When your teacher or professor leads the conversation in the direction of your ideas or arguments, you’ll be able to not only proffer that idea but back it up with textual evidence. That’s an A+ in class participation.

Step 6: Connect These Ideas Across the Narrative

Whether you’re in class or writing an essay, literary analysis isn’t complete until you’ve considered the way these ideas interact and contribute to the work as a whole. You can find and present evidence, but you still have to explain how those elements work together and make up your argument.

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay

When conducting literary analysis while reading a text or discussing it in class, you can pivot easily from one argument to another (or even switch sides if a classmate or teacher makes a compelling enough argument).

But when writing literary analysis, your objective is to propose a specific, arguable thesis and convincingly defend it. In order to do so, you need to fortify your argument with evidence from the text (and perhaps secondary sources) and an authoritative tone.

A successful literary analysis essay depends equally on a thoughtful thesis, supportive analysis, and presenting these elements masterfully. We’ll review how to accomplish these objectives below.

Step 1: Read the Text. Maybe Read It Again.

Constructing an astute analytical essay requires a thorough knowledge of the text. As you read, be sure to note any passages, quotes, or ideas that stand out. These could serve as the future foundation of your thesis statement. Noting these sections now will help you when you need to gather evidence.

The more familiar you become with the text, the better (and easier!) your essay will be. Familiarity with the text allows you to speak (or in this case, write) to it confidently. If you only skim the book, your lack of rich understanding will be evident in your essay. Alternatively, if you read the text closely—especially if you read it more than once, or at least carefully revisit important passages—your own writing will be filled with insight that goes beyond a basic understanding of the storyline.

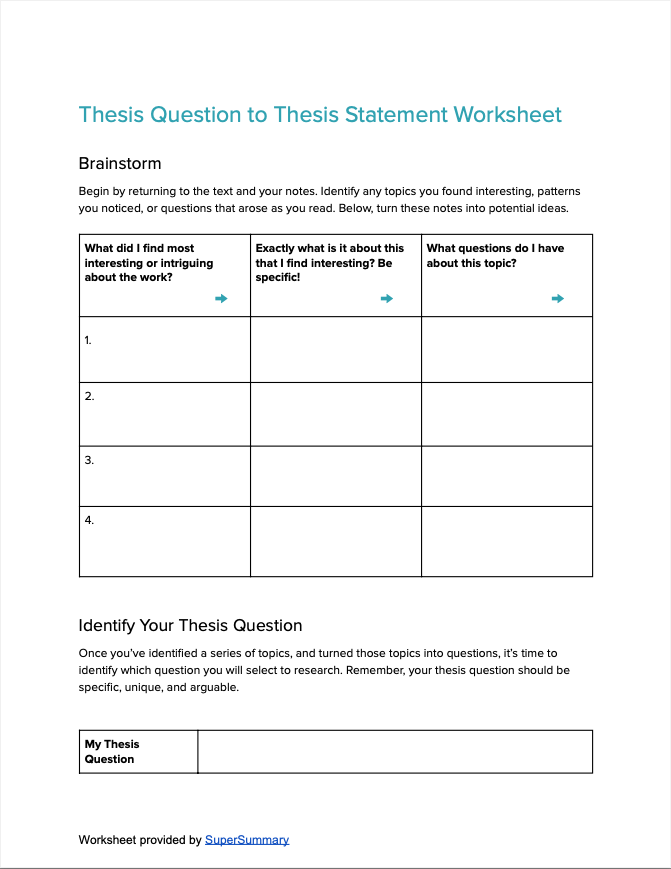

Step 2: Brainstorm Potential Topics

Because you took detailed notes while reading the text, you should have a list of potential topics at the ready. Take time to review your notes, highlighting any ideas or questions you had that feel interesting. You should also return to the text and look for any passages that stand out to you.

When considering potential topics, you should prioritize ideas that you find interesting. It won’t only make the whole process of writing an essay more fun, your enthusiasm for the topic will probably improve the quality of your argument, and maybe even your writing. Just like it’s obvious when a topic interests you in a conversation, it’s obvious when a topic interests the writer of an essay (and even more obvious when it doesn’t).

Your topic ideas should also be specific, unique, and arguable. A good way to think of topics is that they’re the answer to fairly specific questions. As you begin to brainstorm, first think of questions you have about the text. Questions might focus on the plot, such as: Why did the author choose to deviate from the projected storyline? Or why did a character’s role in the narrative shift? Questions might also consider the use of a literary device, such as: Why does the narrator frequently repeat a phrase or comment on a symbol? Or why did the author choose to switch points of view each chapter?

Once you have a thesis question , you can begin brainstorming answers—aka, potential thesis statements . At this point, your answers can be fairly broad. Once you land on a question-statement combination that feels right, you’ll then look for evidence in the text that supports your answer (and helps you define and narrow your thesis statement).

For example, after reading “ The Fall of the House of Usher ,” you might be wondering, Why are Roderick and Madeline twins?, Or even: Why does their relationship feel so creepy?” Maybe you noticed (and noted) that the narrator was surprised to find out they were twins, or perhaps you found that the narrator’s tone tended to shift and become more anxious when discussing the interactions of the twins.

Once you come up with your thesis question, you can identify a broad answer, which will become the basis for your thesis statement. In response to the questions above, your answer might be, “Poe emphasizes the close relationship of Roderick and Madeline to foreshadow that their deaths will be close, too.”

Step 3: Gather Evidence

Once you have your topic (or you’ve narrowed it down to two or three), return to the text (yes, again) to see what evidence you can find to support it. If you’re thinking of writing about the relationship between Roderick and Madeline in “The Fall of the House of Usher,” look for instances where they engaged in the text.

This is when your knowledge of literary devices comes in clutch. Carefully study the language around each event in the text that might be relevant to your topic. How does Poe’s diction or syntax change during the interactions of the siblings? How does the setting reflect or contribute to their relationship? What imagery or symbols appear when Roderick and Madeline are together?

By finding and studying evidence within the text, you’ll strengthen your topic argument—or, just as valuably, discount the topics that aren’t strong enough for analysis.

Step 4: Consider Secondary Sources

In addition to returning to the literary work you’re studying for evidence, you can also consider secondary sources that reference or speak to the work. These can be articles from journals you find on JSTOR, books that consider the work or its context, or articles your teacher shared in class.

While you can use these secondary sources to further support your idea, you should not overuse them. Make sure your topic remains entirely differentiated from that presented in the source.

Step 5: Write a Working Thesis Statement

Once you’ve gathered evidence and narrowed down your topic, you’re ready to refine that topic into a thesis statement. As you continue to outline and write your paper, this thesis statement will likely change slightly, but this initial draft will serve as the foundation of your essay. It’s like your north star: Everything you write in your essay is leading you back to your thesis.

Writing a great thesis statement requires some real finesse. A successful thesis statement is:

- Debatable : You shouldn’t simply summarize or make an obvious statement about the work. Instead, your thesis statement should take a stand on an issue or make a claim that is open to argument. You’ll spend your essay debating—and proving—your argument.

- Demonstrable : You need to be able to prove, through evidence, that your thesis statement is true. That means you have to have passages from the text and correlative analysis ready to convince the reader that you’re right.

- Specific : In most cases, successfully addressing a theme that encompasses a work in its entirety would require a book-length essay. Instead, identify a thesis statement that addresses specific elements of the work, such as a relationship between characters, a repeating symbol, a key setting, or even something really specific like the speaking style of a character.

Example: By depicting the relationship between Roderick and Madeline to be stifling and almost otherworldly in its closeness, Poe foreshadows both Madeline’s fate and Roderick’s inability to choose a different fate for himself.

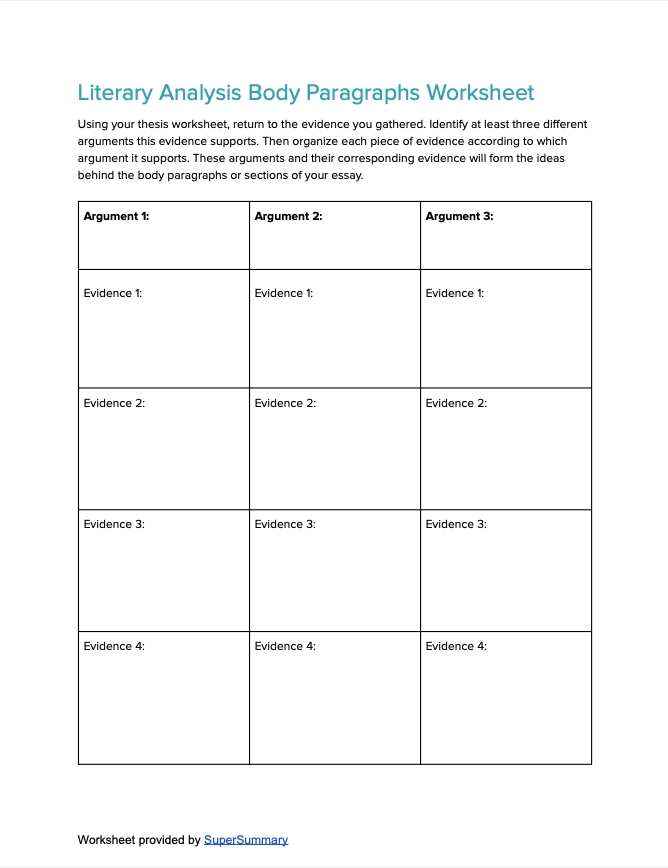

Step 6: Write an Outline

You have your thesis, you have your evidence—but how do you put them together? A great thesis statement (and therefore a great essay) will have multiple arguments supporting it, presenting different kinds of evidence that all contribute to the singular, main idea presented in your thesis.

Review your evidence and identify these different arguments, then organize the evidence into categories based on the argument they support. These ideas and evidence will become the body paragraphs of your essay.

For example, if you were writing about Roderick and Madeline as in the example above, you would pull evidence from the text, such as the narrator’s realization of their relationship as twins; examples where the narrator’s tone of voice shifts when discussing their relationship; imagery, like the sounds Roderick hears as Madeline tries to escape; and Poe’s tendency to use doubles and twins in his other writings to create the same spooky effect. All of these are separate strains of the same argument, and can be clearly organized into sections of an outline.

Step 7: Write Your Introduction

Your introduction serves a few very important purposes that essentially set the scene for the reader:

- Establish context. Sure, your reader has probably read the work. But you still want to remind them of the scene, characters, or elements you’ll be discussing.

- Present your thesis statement. Your thesis statement is the backbone of your analytical paper. You need to present it clearly at the outset so that the reader understands what every argument you make is aimed at.

- Offer a mini-outline. While you don’t want to show all your cards just yet, you do want to preview some of the evidence you’ll be using to support your thesis so that the reader has a roadmap of where they’re going.

Step 8: Write Your Body Paragraphs

Thanks to steps one through seven, you’ve already set yourself up for success. You have clearly outlined arguments and evidence to support them. Now it’s time to translate those into authoritative and confident prose.

When presenting each idea, begin with a topic sentence that encapsulates the argument you’re about to make (sort of like a mini-thesis statement). Then present your evidence and explanations of that evidence that contribute to that argument. Present enough material to prove your point, but don’t feel like you necessarily have to point out every single instance in the text where this element takes place. For example, if you’re highlighting a symbol that repeats throughout the narrative, choose two or three passages where it is used most effectively, rather than trying to squeeze in all ten times it appears.

While you should have clearly defined arguments, the essay should still move logically and fluidly from one argument to the next. Try to avoid choppy paragraphs that feel disjointed; every idea and argument should feel connected to the last, and, as a group, connected to your thesis. A great way to connect the ideas from one paragraph to the next is with transition words and phrases, such as:

- Furthermore

- In addition

- On the other hand

- Conversely

Step 9: Write Your Conclusion

Your conclusion is more than a summary of your essay's parts, but it’s also not a place to present brand new ideas not already discussed in your essay. Instead, your conclusion should return to your thesis (without repeating it verbatim) and point to why this all matters. If writing about the siblings in “The Fall of the House of Usher,” for example, you could point out that the utilization of twins and doubles is a common literary element of Poe’s work that contributes to the definitive eeriness of Gothic literature.

While you might speak to larger ideas in your conclusion, be wary of getting too macro. Your conclusion should still be supported by all of the ideas that preceded it.

Step 10: Revise, Revise, Revise

Of course you should proofread your literary analysis essay before you turn it in. But you should also edit the content to make sure every piece of evidence and every explanation directly supports your thesis as effectively and efficiently as possible.

Sometimes, this might mean actually adapting your thesis a bit to the rest of your essay. At other times, it means removing redundant examples or paraphrasing quotations. Make sure every sentence is valuable, and remove those that aren’t.

Other Resources for Literary Analysis

With these skills and suggestions, you’re well on your way to practicing and writing literary analysis. But if you don’t have a firm grasp on the concepts discussed above—such as literary devices or even the content of the text you’re analyzing—it will still feel difficult to produce insightful analysis.

If you’d like to sharpen the tools in your literature toolbox, there are plenty of other resources to help you do so:

- Check out our expansive library of Literary Devices . These could provide you with a deeper understanding of the basic devices discussed above or introduce you to new concepts sure to impress your professors ( anagnorisis , anyone?).

- This Academic Citation Resource Guide ensures you properly cite any work you reference in your analytical essay.

- Our English Homework Help Guide will point you to dozens of resources that can help you perform analysis, from critical reading strategies to poetry helpers.

- This Grammar Education Resource Guide will direct you to plenty of resources to refine your grammar and writing (definitely important for getting an A+ on that paper).

Of course, you should know the text inside and out before you begin writing your analysis. In order to develop a true understanding of the work, read through its corresponding SuperSummary study guide . Doing so will help you truly comprehend the plot, as well as provide some inspirational ideas for your analysis.

How to Write a Good English Literature Essay

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

How do you write a good English Literature essay? Although to an extent this depends on the particular subject you’re writing about, and on the nature of the question your essay is attempting to answer, there are a few general guidelines for how to write a convincing essay – just as there are a few guidelines for writing well in any field.

We at Interesting Literature call them ‘guidelines’ because we hesitate to use the word ‘rules’, which seems too programmatic. And as the writing habits of successful authors demonstrate, there is no one way to become a good writer – of essays, novels, poems, or whatever it is you’re setting out to write. The French writer Colette liked to begin her writing day by picking the fleas off her cat.

Edith Sitwell, by all accounts, liked to lie in an open coffin before she began her day’s writing. Friedrich von Schiller kept rotten apples in his desk, claiming he needed the scent of their decay to help him write. (For most student essay-writers, such an aroma is probably allowed to arise in the writing-room more organically, over time.)

We will address our suggestions for successful essay-writing to the average student of English Literature, whether at university or school level. There are many ways to approach the task of essay-writing, and these are just a few pointers for how to write a better English essay – and some of these pointers may also work for other disciplines and subjects, too.

Of course, these guidelines are designed to be of interest to the non-essay-writer too – people who have an interest in the craft of writing in general. If this describes you, we hope you enjoy the list as well. Remember, though, everyone can find writing difficult: as Thomas Mann memorably put it, ‘A writer is someone for whom writing is more difficult than it is for other people.’ Nora Ephron was briefer: ‘I think the hardest thing about writing is writing.’ So, the guidelines for successful essay-writing:

1. Planning is important, but don’t spend too long perfecting a structure that might end up changing.

This may seem like odd advice to kick off with, but the truth is that different approaches work for different students and essayists. You need to find out which method works best for you.

It’s not a bad idea, regardless of whether you’re a big planner or not, to sketch out perhaps a few points on a sheet of paper before you start, but don’t be surprised if you end up moving away from it slightly – or considerably – when you start to write.

Often the most extensively planned essays are the most mechanistic and dull in execution, precisely because the writer has drawn up a plan and refused to deviate from it. What is a more valuable skill is to be able to sense when your argument may be starting to go off-topic, or your point is getting out of hand, as you write . (For help on this, see point 5 below.)

We might even say that when it comes to knowing how to write a good English Literature essay, practising is more important than planning.

2. Make room for close analysis of the text, or texts.

Whilst it’s true that some first-class or A-grade essays will be impressive without containing any close reading as such, most of the highest-scoring and most sophisticated essays tend to zoom in on the text and examine its language and imagery closely in the course of the argument. (Close reading of literary texts arises from theology and the analysis of holy scripture, but really became a ‘thing’ in literary criticism in the early twentieth century, when T. S. Eliot, F. R. Leavis, William Empson, and other influential essayists started to subject the poem or novel to close scrutiny.)

Close reading has two distinct advantages: it increases the specificity of your argument (so you can’t be so easily accused of generalising a point), and it improves your chances of pointing up something about the text which none of the other essays your marker is reading will have said. For instance, take In Memoriam (1850), which is a long Victorian poem by the poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson about his grief following the death of his close friend, Arthur Hallam, in the early 1830s.

When answering a question about the representation of religious faith in Tennyson’s poem In Memoriam (1850), how might you write a particularly brilliant essay about this theme? Anyone can make a general point about the poet’s crisis of faith; but to look closely at the language used gives you the chance to show how the poet portrays this.

For instance, consider this stanza, which conveys the poet’s doubt:

A solid and perfectly competent essay might cite this stanza in support of the claim that Tennyson is finding it increasingly difficult to have faith in God (following the untimely and senseless death of his friend, Arthur Hallam). But there are several ways of then doing something more with it. For instance, you might get close to the poem’s imagery, and show how Tennyson conveys this idea, through the image of the ‘altar-stairs’ associated with religious worship and the idea of the stairs leading ‘thro’ darkness’ towards God.

In other words, Tennyson sees faith as a matter of groping through the darkness, trusting in God without having evidence that he is there. If you like, it’s a matter of ‘blind faith’. That would be a good reading. Now, here’s how to make a good English essay on this subject even better: one might look at how the word ‘falter’ – which encapsulates Tennyson’s stumbling faith – disperses into ‘falling’ and ‘altar’ in the succeeding lines. The word ‘falter’, we might say, itself falters or falls apart.

That is doing more than just interpreting the words: it’s being a highly careful reader of the poetry and showing how attentive to the language of the poetry you can be – all the while answering the question, about how the poem portrays the idea of faith. So, read and then reread the text you’re writing about – and be sensitive to such nuances of language and style.

The best way to become attuned to such nuances is revealed in point 5. We might summarise this point as follows: when it comes to knowing how to write a persuasive English Literature essay, it’s one thing to have a broad and overarching argument, but don’t be afraid to use the microscope as well as the telescope.

3. Provide several pieces of evidence where possible.

Many essays have a point to make and make it, tacking on a single piece of evidence from the text (or from beyond the text, e.g. a critical, historical, or biographical source) in the hope that this will be enough to make the point convincing.

‘State, quote, explain’ is the Holy Trinity of the Paragraph for many. What’s wrong with it? For one thing, this approach is too formulaic and basic for many arguments. Is one quotation enough to support a point? It’s often a matter of degree, and although one piece of evidence is better than none, two or three pieces will be even more persuasive.

After all, in a court of law a single eyewitness account won’t be enough to convict the accused of the crime, and even a confession from the accused would carry more weight if it comes supported by other, objective evidence (e.g. DNA, fingerprints, and so on).

Let’s go back to the example about Tennyson’s faith in his poem In Memoriam mentioned above. Perhaps you don’t find the end of the poem convincing – when the poet claims to have rediscovered his Christian faith and to have overcome his grief at the loss of his friend.

You can find examples from the end of the poem to suggest your reading of the poet’s insincerity may have validity, but looking at sources beyond the poem – e.g. a good edition of the text, which will contain biographical and critical information – may help you to find a clinching piece of evidence to support your reading.

And, sure enough, Tennyson is reported to have said of In Memoriam : ‘It’s too hopeful, this poem, more than I am myself.’ And there we have it: much more convincing than simply positing your reading of the poem with a few ambiguous quotations from the poem itself.

Of course, this rule also works in reverse: if you want to argue, for instance, that T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land is overwhelmingly inspired by the poet’s unhappy marriage to his first wife, then using a decent biographical source makes sense – but if you didn’t show evidence for this idea from the poem itself (see point 2), all you’ve got is a vague, general link between the poet’s life and his work.

Show how the poet’s marriage is reflected in the work, e.g. through men and women’s relationships throughout the poem being shown as empty, soulless, and unhappy. In other words, when setting out to write a good English essay about any text, don’t be afraid to pile on the evidence – though be sensible, a handful of quotations or examples should be more than enough to make your point convincing.

4. Avoid tentative or speculative phrasing.

Many essays tend to suffer from the above problem of a lack of evidence, so the point fails to convince. This has a knock-on effect: often the student making the point doesn’t sound especially convinced by it either. This leaks out in the telling use of, and reliance on, certain uncertain phrases: ‘Tennyson might have’ or ‘perhaps Harper Lee wrote this to portray’ or ‘it can be argued that’.

An English university professor used to write in the margins of an essay which used this last phrase, ‘What can’t be argued?’

This is a fair criticism: anything can be argued (badly), but it depends on what evidence you can bring to bear on it (point 3) as to whether it will be a persuasive argument. (Arguing that the plays of Shakespeare were written by a Martian who came down to Earth and ingratiated himself with the world of Elizabethan theatre is a theory that can be argued, though few would take it seriously. We wish we could say ‘none’, but that’s a story for another day.)

Many essay-writers, because they’re aware that texts are often open-ended and invite multiple interpretations (as almost all great works of literature invariably do), think that writing ‘it can be argued’ acknowledges the text’s rich layering of meaning and is therefore valid.

Whilst this is certainly a fact – texts are open-ended and can be read in wildly different ways – the phrase ‘it can be argued’ is best used sparingly if at all. It should be taken as true that your interpretation is, at bottom, probably unprovable. What would it mean to ‘prove’ a reading as correct, anyway? Because you found evidence that the author intended the same thing as you’ve argued of their text? Tennyson wrote in a letter, ‘I wrote In Memoriam because…’?

But the author might have lied about it (e.g. in an attempt to dissuade people from looking too much into their private life), or they might have changed their mind (to go back to the example of The Waste Land : T. S. Eliot championed the idea of poetic impersonality in an essay of 1919, but years later he described The Waste Land as ‘only the relief of a personal and wholly insignificant grouse against life’ – hardly impersonal, then).

Texts – and their writers – can often be contradictory, or cagey about their meaning. But we as critics have to act responsibly when writing about literary texts in any good English essay or exam answer. We need to argue honestly, and sincerely – and not use what Wikipedia calls ‘weasel words’ or hedging expressions.

So, if nothing is utterly provable, all that remains is to make the strongest possible case you can with the evidence available. You do this, not only through marshalling the evidence in an effective way, but by writing in a confident voice when making your case. Fundamentally, ‘There is evidence to suggest that’ says more or less the same thing as ‘It can be argued’, but it foregrounds the evidence rather than the argument, so is preferable as a phrase.

This point might be summarised by saying: the best way to write a good English Literature essay is to be honest about the reading you’re putting forward, so you can be confident in your interpretation and use clear, bold language. (‘Bold’ is good, but don’t get too cocky, of course…)

5. Read the work of other critics.

This might be viewed as the Holy Grail of good essay-writing tips, since it is perhaps the single most effective way to improve your own writing. Even if you’re writing an essay as part of school coursework rather than a university degree, and don’t need to research other critics for your essay, it’s worth finding a good writer of literary criticism and reading their work. Why is this worth doing?

Published criticism has at least one thing in its favour, at least if it’s published by an academic press or has appeared in an academic journal, and that is that it’s most probably been peer-reviewed, meaning that other academics have read it, closely studied its argument, checked it for errors or inaccuracies, and helped to ensure that it is expressed in a fluent, clear, and effective way.

If you’re serious about finding out how to write a better English essay, then you need to study how successful writers in the genre do it. And essay-writing is a genre, the same as novel-writing or poetry. But why will reading criticism help you? Because the critics you read can show you how to do all of the above: how to present a close reading of a poem, how to advance an argument that is not speculative or tentative yet not over-confident, how to use evidence from the text to make your argument more persuasive.

And, the more you read of other critics – a page a night, say, over a few months – the better you’ll get. It’s like textual osmosis: a little bit of their style will rub off on you, and every writer learns by the examples of other writers.

As T. S. Eliot himself said, ‘The poem which is absolutely original is absolutely bad.’ Don’t get precious about your own distinctive writing style and become afraid you’ll lose it. You can’t gain a truly original style before you’ve looked at other people’s and worked out what you like and what you can ‘steal’ for your own ends.

We say ‘steal’, but this is not the same as saying that plagiarism is okay, of course. But consider this example. You read an accessible book on Shakespeare’s language and the author makes a point about rhymes in Shakespeare. When you’re working on your essay on the poetry of Christina Rossetti, you notice a similar use of rhyme, and remember the point made by the Shakespeare critic.

This is not plagiarising a point but applying it independently to another writer. It shows independent interpretive skills and an ability to understand and apply what you have read. This is another of the advantages of reading critics, so this would be our final piece of advice for learning how to write a good English essay: find a critic whose style you like, and study their craft.

If you’re looking for suggestions, we can recommend a few favourites: Christopher Ricks, whose The Force of Poetry is a tour de force; Jonathan Bate, whose The Genius of Shakespeare , although written for a general rather than academic audience, is written by a leading Shakespeare scholar and academic; and Helen Gardner, whose The Art of T. S. Eliot , whilst dated (it came out in 1949), is a wonderfully lucid and articulate analysis of Eliot’s poetry.

James Wood’s How Fiction Works is also a fine example of lucid prose and how to close-read literary texts. Doubtless readers of Interesting Literature will have their own favourites to suggest in the comments, so do check those out, as these are just three personal favourites. What’s your favourite work of literary scholarship/criticism? Suggestions please.

Much of all this may strike you as common sense, but even the most commonsensical advice can go out of your mind when you have a piece of coursework to write, or an exam to revise for. We hope these suggestions help to remind you of some of the key tenets of good essay-writing practice – though remember, these aren’t so much commandments as recommendations. No one can ‘tell’ you how to write a good English Literature essay as such.

But it can be learned. And remember, be interesting – find the things in the poems or plays or novels which really ignite your enthusiasm. As John Mortimer said, ‘The only rule I have found to have any validity in writing is not to bore yourself.’

Finally, good luck – and happy writing!

And if you enjoyed these tips for how to write a persuasive English essay, check out our advice for how to remember things for exams and our tips for becoming a better close reader of poetry .

30 thoughts on “How to Write a Good English Literature Essay”

You must have taken AP Literature. I’m always saying these same points to my students.

I also think a crucial part of excellent essay writing that too many students do not realize is that not every point or interpretation needs to be addressed. When offered the chance to write your interpretation of a work of literature, it is important to note that there of course are many but your essay should choose one and focus evidence on this one view rather than attempting to include all views and evidence to back up each view.

Reblogged this on SocioTech'nowledge .

Not a bad effort…not at all! (Did you intend “subject” instead of “object” in numbered paragraph two, line seven?”

Oops! I did indeed – many thanks for spotting. Duly corrected ;)

That’s what comes of writing about philosophy and the subject/object for another post at the same time!

Reblogged this on Scribing English .

- Pingback: Recommended Resource: Interesting Literature.com & how to write an essay | Write Out Loud

Great post on essay writing! I’ve shared a post about this and about the blog site in general which you can look at here: http://writeoutloudblog.com/2015/01/13/recommended-resource-interesting-literature-com-how-to-write-an-essay/

All of these are very good points – especially I like 2 and 5. I’d like to read the essay on the Martian who wrote Shakespeare’s plays).

Reblogged this on Uniqely Mustered and commented: Dedicate this to all upcoming writers and lovers of Writing!

I shall take this as my New Year boost in Writing Essays. Please try to visit often for corrections,advise and criticisms.

Reblogged this on Blue Banana Bread .

Reblogged this on worldsinthenet .

All very good points, but numbers 2 and 4 are especially interesting.

- Pingback: Weekly Digest | Alpha Female, Mainstream Cat

Reblogged this on rainniewu .

Reblogged this on pixcdrinks .

- Pingback: How to Write a Good English Essay? Interesting Literature | EngLL.Com

Great post. Interesting infographic how to write an argumentative essay http://www.essay-profy.com/blog/how-to-write-an-essay-writing-an-argumentative-essay/

Reblogged this on DISTINCT CHARACTER and commented: Good Tips

Reblogged this on quirkywritingcorner and commented: This could be applied to novel or short story writing as well.

Reblogged this on rosetech67 and commented: Useful, albeit maybe a bit late for me :-)

- Pingback: How to Write a Good English Essay | georg28ang

such a nice pieace of content you shared in this write up about “How to Write a Good English Essay” going to share on another useful resource that is

- Pingback: Mark Twain’s Rules for Good Writing | Interesting Literature

- Pingback: How to Remember Things for Exams | Interesting Literature

- Pingback: Michael Moorcock: How to Write a Novel in 3 Days | Interesting Literature

- Pingback: Shakespeare and the Essay | Interesting Literature

A well rounded summary on all steps to keep in mind while starting on writing. There are many new avenues available though. Benefit from the writing options of the 21st century from here, i loved it! http://authenticwritingservices.com

- Pingback: Mark Twain’s Rules for Good Writing | Peacejusticelove's Blog

Comments are closed.

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Introduction

You’ve been assigned a literary analysis paper—what does that even mean? Is it like a book report that you used to write in high school? Well, not really.

A literary analysis essay asks you to make an original argument about a poem, play, or work of fiction and support that argument with research and evidence from your careful reading of the text.

It can take many forms, such as a close reading of a text, critiquing the text through a particular literary theory, comparing one text to another, or criticizing another critic’s interpretation of the text. While there are many ways to structure a literary essay, writing this kind of essay follows generally follows a similar process for everyone

Crafting a good literary analysis essay begins with good close reading of the text, in which you have kept notes and observations as you read. This will help you with the first step, which is selecting a topic to write about—what jumped out as you read, what are you genuinely interested in? The next step is to focus your topic, developing it into an argument—why is this subject or observation important? Why should your reader care about it as much as you do? The third step is to gather evidence to support your argument, for literary analysis, support comes in the form of evidence from the text and from your research on what other literary critics have said about your topic. Only after you have performed these steps, are you ready to begin actually writing your essay.

Writing a Literary Analysis Essay

How to create a topic and conduct research:.

Writing an Analysis of a Poem, Story, or Play

If you are taking a literature course, it is important that you know how to write an analysis—sometimes called an interpretation or a literary analysis or a critical reading or a critical analysis—of a story, a poem, and a play. Your instructor will probably assign such an analysis as part of the course assessment. On your mid-term or final exam, you might have to write an analysis of one or more of the poems and/or stories on your reading list. Or the dreaded “sight poem or story” might appear on an exam, a work that is not on the reading list, that you have not read before, but one your instructor includes on the exam to examine your ability to apply the active reading skills you have learned in class to produce, independently, an effective literary analysis.You might be asked to write instead or, or in addition to an analysis of a literary work, a more sophisticated essay in which you compare and contrast the protagonists of two stories, or the use of form and metaphor in two poems, or the tragic heroes in two plays.

You might learn some literary theory in your course and be asked to apply theory—feminist, Marxist, reader-response, psychoanalytic, new historicist, for example—to one or more of the works on your reading list. But the seminal assignment in a literature course is the analysis of the single poem, story, novel, or play, and, even if you do not have to complete this assignment specifically, it will form the basis of most of the other writing assignments you will be required to undertake in your literature class. There are several ways of structuring a literary analysis, and your instructor might issue specific instructions on how he or she wants this assignment done. The method presented here might not be identical to the one your instructor wants you to follow, but it will be easy enough to modify, if your instructor expects something a bit different, and it is a good default method, if your instructor does not issue more specific guidelines.You want to begin your analysis with a paragraph that provides the context of the work you are analyzing and a brief account of what you believe to be the poem or story or play’s main theme. At a minimum, your account of the work’s context will include the name of the author, the title of the work, its genre, and the date and place of publication. If there is an important biographical or historical context to the work, you should include that, as well.Try to express the work’s theme in one or two sentences. Theme, you will recall, is that insight into human experience the author offers to readers, usually revealed as the content, the drama, the plot of the poem, story, or play unfolds and the characters interact. Assessing theme can be a complex task. Authors usually show the theme; they don’t tell it. They rarely say, at the end of the story, words to this effect: “and the moral of my story is…” They tell their story, develop their characters, provide some kind of conflict—and from all of this theme emerges. Because identifying theme can be challenging and subjective, it is often a good idea to work through the rest of the analysis, then return to the beginning and assess theme in light of your analysis of the work’s other literary elements.Here is a good example of an introductory paragraph from Ben’s analysis of William Butler Yeats’ poem, “Among School Children.”

“Among School Children” was published in Yeats’ 1928 collection of poems The Tower. It was inspired by a visit Yeats made in 1926 to school in Waterford, an official visit in his capacity as a senator of the Irish Free State. In the course of the tour, Yeats reflects upon his own youth and the experiences that shaped the “sixty-year old, smiling public man” (line 8) he has become. Through his reflection, the theme of the poem emerges: a life has meaning when connections among apparently disparate experiences are forged into a unified whole.

In the body of your literature analysis, you want to guide your readers through a tour of the poem, story, or play, pausing along the way to comment on, analyze, interpret, and explain key incidents, descriptions, dialogue, symbols, the writer’s use of figurative language—any of the elements of literature that are relevant to a sound analysis of this particular work. Your main goal is to explain how the elements of literature work to elucidate, augment, and develop the theme. The elements of literature are common across genres: a story, a narrative poem, and a play all have a plot and characters. But certain genres privilege certain literary elements. In a poem, for example, form, imagery and metaphor might be especially important; in a story, setting and point-of-view might be more important than they are in a poem; in a play, dialogue, stage directions, lighting serve functions rarely relevant in the analysis of a story or poem.

The length of the body of an analysis of a literary work will usually depend upon the length of work being analyzed—the longer the work, the longer the analysis—though your instructor will likely establish a word limit for this assignment. Make certain that you do not simply paraphrase the plot of the story or play or the content of the poem. This is a common weakness in student literary analyses, especially when the analysis is of a poem or a play.

Here is a good example of two body paragraphs from Amelia’s analysis of “Araby” by James Joyce.

Within the story’s first few paragraphs occur several religious references which will accumulate as the story progresses. The narrator is a student at the Christian Brothers’ School; the former tenant of his house was a priest; he left behind books called The Abbot and The Devout Communicant. Near the end of the story’s second paragraph the narrator describes a “central apple tree” in the garden, under which is “the late tenant’s rusty bicycle pump.” We may begin to suspect the tree symbolizes the apple tree in the Garden of Eden and the bicycle pump, the snake which corrupted Eve, a stretch, perhaps, until Joyce’s fall-of-innocence theme becomes more apparent.

The narrator must continue to help his aunt with her errands, but, even when he is so occupied, his mind is on Mangan’s sister, as he tries to sort out his feelings for her. Here Joyce provides vivid insight into the mind of an adolescent boy at once elated and bewildered by his first crush. He wants to tell her of his “confused adoration,” but he does not know if he will ever have the chance. Joyce’s description of the pleasant tension consuming the narrator is conveyed in a striking simile, which continues to develop the narrator’s character, while echoing the religious imagery, so important to the story’s theme: “But my body was like a harp, and her words and gestures were like fingers, running along the wires.”

The concluding paragraph of your analysis should realize two goals. First, it should present your own opinion on the quality of the poem or story or play about which you have been writing. And, second, it should comment on the current relevance of the work. You should certainly comment on the enduring social relevance of the work you are explicating. You may comment, though you should never be obliged to do so, on the personal relevance of the work. Here is the concluding paragraph from Dao-Ming’s analysis of Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest.

First performed in 1895, The Importance of Being Earnest has been made into a film, as recently as 2002 and is regularly revived by professional and amateur theatre companies. It endures not only because of the comic brilliance of its characters and their dialogue, but also because its satire still resonates with contemporary audiences. I am still amazed that I see in my own Asian mother a shadow of Lady Bracknell, with her obsession with finding for her daughter a husband who will maintain, if not, ideally, increase the family’s social status. We might like to think we are more liberated and socially sophisticated than our Victorian ancestors, but the starlets and eligible bachelors who star in current reality television programs illustrate the extent to which superficial concerns still influence decisions about love and even marriage. Even now, we can turn to Oscar Wilde to help us understand and laugh at those who are earnest in name only.

Dao-Ming’s conclusion is brief, but she does manage to praise the play, reaffirm its main theme, and explain its enduring appeal. And note how her last sentence cleverly establishes that sense of closure that is also a feature of an effective analysis.

You may, of course, modify the template that is presented here. Your instructor might favour a somewhat different approach to literary analysis. Its essence, though, will be your understanding and interpretation of the theme of the poem, story, or play and the skill with which the author shapes the elements of literature—plot, character, form, diction, setting, point of view—to support the theme.

Academic Writing Tips : How to Write a Literary Analysis Paper. Authored by: eHow. Located at: https://youtu.be/8adKfLwIrVk. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

BC Open Textbooks: English Literature Victorians and Moderns: https://opentextbc.ca/englishliterature/back-matter/appendix-5-writing-an-analysis-of-a-poem-story-and-play/

Literary Analysis

The challenges of writing about english literature.

Writing begins with the act of reading . While this statement is true for most college papers, strong English papers tend to be the product of highly attentive reading (and rereading). When your instructors ask you to do a “close reading,” they are asking you to read not only for content, but also for structures and patterns. When you perform a close reading, then, you observe how form and content interact. In some cases, form reinforces content: for example, in John Donne’s Holy Sonnet 14, where the speaker invites God’s “force” “to break, blow, burn and make [him] new.” Here, the stressed monosyllables of the verbs “break,” “blow” and “burn” evoke aurally the force that the speaker invites from God. In other cases, form raises questions about content: for example, a repeated denial of guilt will likely raise questions about the speaker’s professed innocence. When you close read, take an inductive approach. Start by observing particular details in the text, such as a repeated image or word, an unexpected development, or even a contradiction. Often, a detail–such as a repeated image–can help you to identify a question about the text that warrants further examination. So annotate details that strike you as you read. Some of those details will eventually help you to work towards a thesis. And don’t worry if a detail seems trivial. If you can make a case about how an apparently trivial detail reveals something significant about the text, then your paper will have a thought-provoking thesis to argue.

Common Types of English Papers Many assignments will ask you to analyze a single text. Others, however, will ask you to read two or more texts in relation to each other, or to consider a text in light of claims made by other scholars and critics. For most assignments, close reading will be central to your paper. While some assignment guidelines will suggest topics and spell out expectations in detail, others will offer little more than a page limit. Approaching the writing process in the absence of assigned topics can be daunting, but remember that you have resources: in section, you will probably have encountered some examples of close reading; in lecture, you will have encountered some of the course’s central questions and claims. The paper is a chance for you to extend a claim offered in lecture, or to analyze a passage neglected in lecture. In either case, your analysis should do more than recapitulate claims aired in lecture and section. Because different instructors have different goals for an assignment, you should always ask your professor or TF if you have questions. These general guidelines should apply in most cases: