- Top Courses

- Online Degrees

- Find your New Career

- Join for Free

What Are Critical Thinking Skills and Why Are They Important?

Learn what critical thinking skills are, why they’re important, and how to develop and apply them in your workplace and everyday life.

![briefly identify the importance of critical thinking in achieving your institutional [Featured Image]: Project Manager, approaching and analyzing the latest project with a team member,](https://d3njjcbhbojbot.cloudfront.net/api/utilities/v1/imageproxy/https://images.ctfassets.net/wp1lcwdav1p1/1SOj8kON2XLXVb6u3bmDwN/62a5b68b69ec07b192de34b7ce8fa28a/GettyImages-598260236.jpg?w=1500&h=680&q=60&fit=fill&f=faces&fm=jpg&fl=progressive&auto=format%2Ccompress&dpr=1&w=1000)

We often use critical thinking skills without even realizing it. When you make a decision, such as which cereal to eat for breakfast, you're using critical thinking to determine the best option for you that day.

Critical thinking is like a muscle that can be exercised and built over time. It is a skill that can help propel your career to new heights. You'll be able to solve workplace issues, use trial and error to troubleshoot ideas, and more.

We'll take you through what it is and some examples so you can begin your journey in mastering this skill.

What is critical thinking?

Critical thinking is the ability to interpret, evaluate, and analyze facts and information that are available, to form a judgment or decide if something is right or wrong.

More than just being curious about the world around you, critical thinkers make connections between logical ideas to see the bigger picture. Building your critical thinking skills means being able to advocate your ideas and opinions, present them in a logical fashion, and make decisions for improvement.

Build job-ready skills with a Coursera Plus subscription

- Get access to 7,000+ learning programs from world-class universities and companies, including Google, Yale, Salesforce, and more

- Try different courses and find your best fit at no additional cost

- Earn certificates for learning programs you complete

- A subscription price of $59/month, cancel anytime

Why is critical thinking important?

Critical thinking is useful in many areas of your life, including your career. It makes you a well-rounded individual, one who has looked at all of their options and possible solutions before making a choice.

According to the University of the People in California, having critical thinking skills is important because they are [ 1 ]:

Crucial for the economy

Essential for improving language and presentation skills

Very helpful in promoting creativity

Important for self-reflection

The basis of science and democracy

Critical thinking skills are used every day in a myriad of ways and can be applied to situations such as a CEO approaching a group project or a nurse deciding in which order to treat their patients.

Examples of common critical thinking skills

Critical thinking skills differ from individual to individual and are utilized in various ways. Examples of common critical thinking skills include:

Identification of biases: Identifying biases means knowing there are certain people or things that may have an unfair prejudice or influence on the situation at hand. Pointing out these biases helps to remove them from contention when it comes to solving the problem and allows you to see things from a different perspective.

Research: Researching details and facts allows you to be prepared when presenting your information to people. You’ll know exactly what you’re talking about due to the time you’ve spent with the subject material, and you’ll be well-spoken and know what questions to ask to gain more knowledge. When researching, always use credible sources and factual information.

Open-mindedness: Being open-minded when having a conversation or participating in a group activity is crucial to success. Dismissing someone else’s ideas before you’ve heard them will inhibit you from progressing to a solution, and will often create animosity. If you truly want to solve a problem, you need to be willing to hear everyone’s opinions and ideas if you want them to hear yours.

Analysis: Analyzing your research will lead to you having a better understanding of the things you’ve heard and read. As a true critical thinker, you’ll want to seek out the truth and get to the source of issues. It’s important to avoid taking things at face value and always dig deeper.

Problem-solving: Problem-solving is perhaps the most important skill that critical thinkers can possess. The ability to solve issues and bounce back from conflict is what helps you succeed, be a leader, and effect change. One way to properly solve problems is to first recognize there’s a problem that needs solving. By determining the issue at hand, you can then analyze it and come up with several potential solutions.

How to develop critical thinking skills

You can develop critical thinking skills every day if you approach problems in a logical manner. Here are a few ways you can start your path to improvement:

1. Ask questions.

Be inquisitive about everything. Maintain a neutral perspective and develop a natural curiosity, so you can ask questions that develop your understanding of the situation or task at hand. The more details, facts, and information you have, the better informed you are to make decisions.

2. Practice active listening.

Utilize active listening techniques, which are founded in empathy, to really listen to what the other person is saying. Critical thinking, in part, is the cognitive process of reading the situation: the words coming out of their mouth, their body language, their reactions to your own words. Then, you might paraphrase to clarify what they're saying, so both of you agree you're on the same page.

3. Develop your logic and reasoning.

This is perhaps a more abstract task that requires practice and long-term development. However, think of a schoolteacher assessing the classroom to determine how to energize the lesson. There's options such as playing a game, watching a video, or challenging the students with a reward system. Using logic, you might decide that the reward system will take up too much time and is not an immediate fix. A video is not exactly relevant at this time. So, the teacher decides to play a simple word association game.

Scenarios like this happen every day, so next time, you can be more aware of what will work and what won't. Over time, developing your logic and reasoning will strengthen your critical thinking skills.

Learn tips and tricks on how to become a better critical thinker and problem solver through online courses from notable educational institutions on Coursera. Start with Introduction to Logic and Critical Thinking from Duke University or Mindware: Critical Thinking for the Information Age from the University of Michigan.

Article sources

University of the People, “ Why is Critical Thinking Important?: A Survival Guide , https://www.uopeople.edu/blog/why-is-critical-thinking-important/.” Accessed May 18, 2023.

Keep reading

Coursera staff.

Editorial Team

Coursera’s editorial team is comprised of highly experienced professional editors, writers, and fact...

This content has been made available for informational purposes only. Learners are advised to conduct additional research to ensure that courses and other credentials pursued meet their personal, professional, and financial goals.

6 Benefits of Critical Thinking and Why They Matter

There is much that has been said in praise of critical thinking. We all seem to agree that critical thinking is a good thing, but why? What are the advantages of engaging in it at all?

That’s what we hope to address in this post, but first, let’s look at history. The methodology named after the Greek philosopher Socrates— the Socratic method —is one of the earliest critical thinking instruction tools known to man. Centuries later, Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius Antonius would warn in his meditations that, “Everything we hear is an opinion, not a fact; everything we see is a perspective, not the truth.”

Fast forward past Galileo, W. E. B. Du Bois, Albert Einstein, Bertrand Russell, Martin Luther King Jr., and countless others, and we discover the practice of critical thinking is likely thousands of years old.

So what is it that makes it such a time-tested skill set? In what ways does critical thinking truly benefit us? Though this list can be expanded considerably, we believe these six merits are among the most significant.

1. It encourages curiosity

Curiosity exists to help us gain a deeper understanding of not only the world surrounding us but the things that matter within our experience of that world. This extends to the topics we teach in school, and also the ones that we find relevant in our daily lives.

Effective critical thinkers remain curious about a wide range of topics and generally have broad interests. They retain inquisitiveness about the world and about people and have an understanding of and appreciation for the cultures, beliefs, and views that are a shared quality of our humanity. This is also part of what makes them lifelong learners.

They are always alert for chances to apply their best thinking habits to any situation. A desire to think critically about even the simplest of issues and tasks indicates a desire for constructive outcomes.

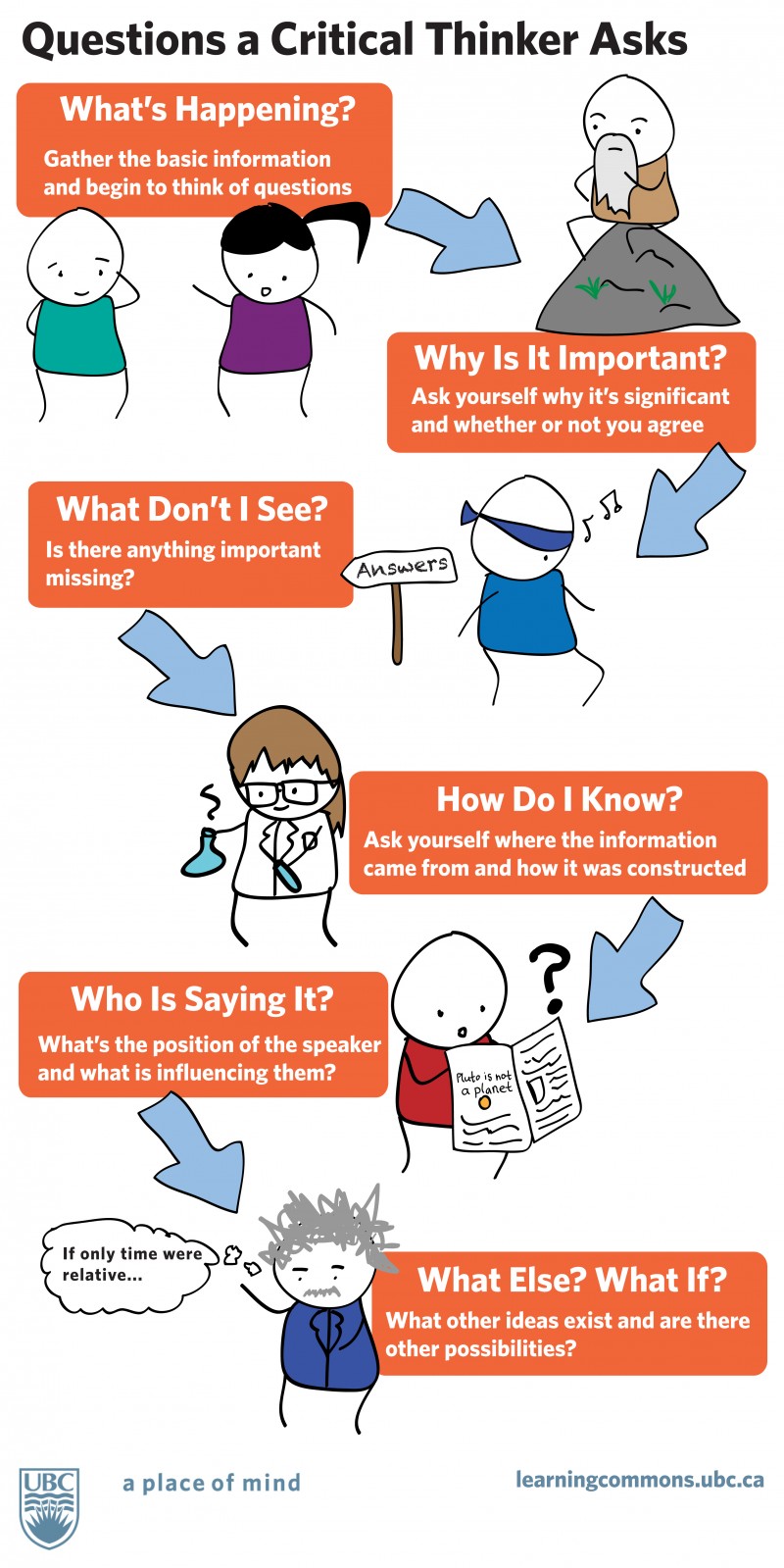

To this end, critical thinkers ask pertinent questions such as:

What’s happening? What am I seeing?

Why is it important? Who is affected by this?

What am I missing? What’s hidden and why is it important?

Where did this come from? How do I know for sure?

Who is saying this? Why should I listen to this person? What can they teach me?

What else should I consider?

Effective critical thinkers don't take anything at face value, either. They never stop asking questions and enjoy exploring all sides of an issue and the deeper facts hiding within all modes of data.

2. It enhances creativity

In our travels, we've asked educators all over the world about the most important skills kids need to thrive beyond school. It's pleasing to see that nurturing student creativity is very high on that list. In fact, it's number 2, directly below problem-solving.

There's no question that effective critical thinkers are also largely creative thinkers. Creativity has unquestionably defined itself as a requisite skill for having in the collaborative modern workforce.

Critical thinking in business, marketing, and professional alliances relies heavily on one's ability to be creative. When businesses get creative with products and how they are advertised, they thrive in the global marketplace. The shift in valuing creativity and its ability to increase revenue by enhancing product value echoes in every market segment. Here are just a few examples:

Paul Thompson, former director of New York's Cooper-Hewitt Museum:

“Manufacturers have begun to recognize that we can’t compete with the pricing structure and labor costs of the Far East. So how can we compete? It has to be with design.”

Roger Martin, Dean of the Rotman School of Management:

“Businesspeople don't need to understand designers better. They need to be designers."

Robert Lutz of the GM Corporation:

"I see us in the art business. Art entertainment and mobile sculpture, that coincidently happens to provide transportation.”

Norio Ohga, former Sony Chairman and inventor of the CD:

“At Sony, we assume that all products of our competitors have basically the same technology, price, performance, and features. Design is the only thing that differentiates one product from another in the marketplace.”

Creative people question assumptions about many things. Instead of arguing for limitations, creative minds ask "how" or"why not?" Creativity is eternal and it has limitless potential, which means we are unlimited as creative people.

In fact, if creativity is within all of us, then we are also limitless.

This applies to learners of all ages, and although the intellectual risks any critical thinker takes creatively are also sensible, such a person never fears stepping outside their creative comfort zone.

3. It reinforces problem-solving ability

Those who think critically tend to be instinctual problem-solvers. This ranks as probably the most important skill we can help our learners build upon. The children of today are the leaders of tomorrow and will face complex challenges using critical thinking capacity to engineer imaginative solutions.

One of history’s most prolific critical thinkers, Albert Einstein, once said, “It’s not that I’m so smart; it’s just that I stay with problems longer.”

“ A desire to think critically about even the simplest of issues and tasks indicates a desire for constructive outcomes. ”

It’s also worth noting this is the same guy who said that, when given an hour to solve a problem, he’d likely spend 5 minutes on the solution and the other 55 minutes defining and researching the problem. This kind of patience and commitment to truly understanding a problem is a mark of a true critical thinker. It’s the main reason why solid critical thinking ability is essential to being an effective problem-solver.

Developing solid critical thinking skills prepares our learners to face the complex problems that matter to the world head-on. After all, our students are inheriting such issues as:

global warming

overpopulation

the need for health care

water shortages

electronic waste management

energy crises

As these challenges continue to change and grow as the world changes around them, the best minds needed to solve them will be those prepared to think creatively and divergently to produce innovative and lasting solutions. Critical thinking capacity does all that and more.

4. It’s a multi-faceted practice

Critical thinking is known for encompassing a wide array of disciplines, and cultivating a broad range of cognitive talents. One could indeed say that it’s a cross-curricular activity for the mind, and the mind must be exercised just like a muscle to stay healthy.

Among many other things, critical thinking promotes the development of things like:

Reasoning skills

Analytical thinking

Evaluative skills

Logical thinking

Organizational and planning skills

Language skills

Self-reflective capacity

Observational skills

Open-mindedness

Creative visualization techniques

Questioning ability

Decision making

This list could easily be expanded to include other skills, but this gives one an idea of just what is being developed and enhanced when we choose to think critically in our daily lives.

5. It fosters independence

Getting our learners to begin thinking independently is one of the many goals of education. When students think for themselves, they learn to become independent of us as well.

Our job as educators, in this sense, is to empower our students to the point at which we essentially become obsolete. This process is repeated year after year, student after student, and moment after moment as we cultivate independent thinking and responsibility for learning in those we teach.

Independent thinking skills are at the forefront of learning how to be not only a great thinker, but a great leader. Such skills teach our learners how to make sense of the world based on personal experience and observation, and to make critical well-informed decisions in the same way. As such, they gain confidence and the ability to learn from mistakes as they build successful and productive lives.

“ Critical thinking is known for encompassing a wide array of disciplines and cultivating a broad range of cognitive talents—it’s a cross-curricular activity for the mind. ”

When we think critically, we think in a self-directed manner. Our thinking is disciplined and thus becomes a self-correcting mindset. It also means that such strong proactive thinking abilities become second nature as we continue to develop them through learning and experience.

As we stated earlier, independent critical thinking skills are among the top skills educators strive to give to their students. That's because when we succeed at getting learners to think independently, we've given them a gift for life.

Once school is over they can then go into future enterprises and pursuits with confidence and pride. That, of course, leads us to our final point.

6. It’s a skill for life, not just learning

As all teachers know, what they do with passion every day prepares our learners not just for the time in the classroom, but for success and well-being when the formative years are done.

When we here at Future Focused Learning introduced the Essential Fluencies and the 10 Shifts of Practice to educators all over the world, we too had these goals firmly in mind. That’s why we made sure these processes all involved actively building independent and critical thinking mindsets, and fostered lifelong learning skills for students.

Many great educators have said many great things about the importance of lifelong learning skills. John Dewey, however, probably said it best: "Education is not preparation for life; education is life itself."

Educators want their learners to succeed both in and out of the classroom. The idea is to make sure that once they leave school they no longer need us. In essence, our learners must become teachers and leaders.

The point is that they never stop being learners.

This is what it means to be a lifelong learner and a critical thinker.

Author and keynote speaker, Lee works with governments, education systems, international agencies and corporations to help people and organisations connect to their higher purpose. Lee lives in Japan where he studies Zen and the Shakuhachi.

How Learning a Growth Mindset Benefits Our Kids

The growth mindset choice: 10 fixed mindset examples we can change.

- How to apply critical thinking in learning

Sometimes your university classes might feel like a maze of information. Consider critical thinking skills like a map that can lead the way.

Why do we need critical thinking?

Critical thinking is a type of thinking that requires continuous questioning, exploring answers, and making judgments. Critical thinking can help you:

- analyze information to comprehend more thoroughly

- approach problems systematically, identify root causes, and explore potential solutions

- make informed decisions by weighing various perspectives

- promote intellectual curiosity and self-reflection, leading to continuous learning, innovation, and personal development

What is the process of critical thinking?

1. understand .

Critical thinking starts with understanding the content that you are learning.

This step involves clarifying the logic and interrelations of the content by actively engaging with the materials (e.g., text, articles, and research papers). You can take notes, highlight key points, and make connections with prior knowledge to help you engage.

Ask yourself these questions to help you build your understanding:

- What is the structure?

- What is the main idea of the content?

- What is the evidence that supports any arguments?

- What is the conclusion?

2. Analyze

You need to assess the credibility, validity, and relevance of the information presented in the content. Consider the authors’ biases and potential limitations in the evidence.

Ask yourself questions in terms of why and how:

- What is the supporting evidence?

- Why do they use it as evidence?

- How does the data present support the conclusions?

- What method was used? Was it appropriate?

3. Evaluate

After analyzing the data and evidence you collected, make your evaluation of the evidence, results, and conclusions made in the content.

Consider the weaknesses and strengths of the ideas presented in the content to make informed decisions or suggest alternative solutions:

- What is the gap between the evidence and the conclusion?

- What is my position on the subject?

- What other approaches can I use?

When do you apply critical thinking and how can you improve these skills?

1. reading academic texts, articles, and research papers.

- analyze arguments

- assess the credibility and validity of evidence

- consider potential biases presented

- question the assumptions, methodologies, and the way they generate conclusions

2. Writing essays and theses

- demonstrate your understanding of the information, logic of evidence, and position on the topic

- include evidence or examples to support your ideas

- make your standing points clear by presenting information and providing reasons to support your arguments

- address potential counterarguments or opposing viewpoints

- explain why your perspective is more compelling than the opposing viewpoints

3. Attending lectures

- understand the content by previewing, active listening , and taking notes

- analyze your lecturer’s viewpoints by seeking whether sufficient data and resources are provided

- think about whether the ideas presented by the lecturer align with your values and beliefs

- talk about other perspectives with peers in discussions

Related blog posts

- A beginner's guide to successful labs

- A beginner's guide to note-taking

- 5 steps to get the most out of your next reading

- How do you create effective study questions?

- An epic approach to problem-based test questions

Recent blog posts

Blog topics.

- assignments (1)

- Graduate (2)

- Learning support (25)

- note-taking and reading (6)

- tests and exams (8)

- time management (3)

- Tips from students (6)

- undergraduate (27)

- university learning (10)

Blog posts by audience

- Current undergraduate students (27)

- Current graduate students (3)

- Future undergraduate students (9)

- Future graduate students (1)

Blog posts archive

- December (1)

- November (6)

- October (8)

- August (10)

Contact the Student Success Office

South Campus Hall, second floor University of Waterloo 519-888-4567 ext. 84410

Immigration Consulting

Book a same-day appointment on Portal or submit an online inquiry to receive immigration support.

Request an authorized leave from studies for immigration purposes.

Quick links

Current student resources

SSO staff links

Employment and volunteer opportunities

- Contact Waterloo

- Maps & Directions

- Accessibility

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations .

Tips for Online Students , Tips for Students

Why Is Critical Thinking Important? A Survival Guide

Updated: December 7, 2023

Published: April 2, 2020

Why is critical thinking important? The decisions that you make affect your quality of life. And if you want to ensure that you live your best, most successful and happy life, you’re going to want to make conscious choices. That can be done with a simple thing known as critical thinking. Here’s how to improve your critical thinking skills and make decisions that you won’t regret.

What Is Critical Thinking?

You’ve surely heard of critical thinking, but you might not be entirely sure what it really means, and that’s because there are many definitions. For the most part, however, we think of critical thinking as the process of analyzing facts in order to form a judgment. Basically, it’s thinking about thinking.

How Has The Definition Evolved Over Time?

The first time critical thinking was documented is believed to be in the teachings of Socrates , recorded by Plato. But throughout history, the definition has changed.

Today it is best understood by philosophers and psychologists and it’s believed to be a highly complex concept. Some insightful modern-day critical thinking definitions include :

- “Reasonable, reflective thinking that is focused on deciding what to believe or do.”

- “Deciding what’s true and what you should do.”

The Importance Of Critical Thinking

Why is critical thinking important? Good question! Here are a few undeniable reasons why it’s crucial to have these skills.

1. Critical Thinking Is Universal

Critical thinking is a domain-general thinking skill. What does this mean? It means that no matter what path or profession you pursue, these skills will always be relevant and will always be beneficial to your success. They are not specific to any field.

2. Crucial For The Economy

Our future depends on technology, information, and innovation. Critical thinking is needed for our fast-growing economies, to solve problems as quickly and as effectively as possible.

3. Improves Language & Presentation Skills

In order to best express ourselves, we need to know how to think clearly and systematically — meaning practice critical thinking! Critical thinking also means knowing how to break down texts, and in turn, improve our ability to comprehend.

4. Promotes Creativity

By practicing critical thinking, we are allowing ourselves not only to solve problems but also to come up with new and creative ideas to do so. Critical thinking allows us to analyze these ideas and adjust them accordingly.

5. Important For Self-Reflection

Without critical thinking, how can we really live a meaningful life? We need this skill to self-reflect and justify our ways of life and opinions. Critical thinking provides us with the tools to evaluate ourselves in the way that we need to.

6. The Basis Of Science & Democracy

In order to have a democracy and to prove scientific facts, we need critical thinking in the world. Theories must be backed up with knowledge. In order for a society to effectively function, its citizens need to establish opinions about what’s right and wrong (by using critical thinking!).

Benefits Of Critical Thinking

We know that critical thinking is good for society as a whole, but what are some benefits of critical thinking on an individual level? Why is critical thinking important for us?

1. Key For Career Success

Critical thinking is crucial for many career paths. Not just for scientists, but lawyers , doctors, reporters, engineers , accountants, and analysts (among many others) all have to use critical thinking in their positions. In fact, according to the World Economic Forum, critical thinking is one of the most desirable skills to have in the workforce, as it helps analyze information, think outside the box, solve problems with innovative solutions, and plan systematically.

2. Better Decision Making

There’s no doubt about it — critical thinkers make the best choices. Critical thinking helps us deal with everyday problems as they come our way, and very often this thought process is even done subconsciously. It helps us think independently and trust our gut feeling.

3. Can Make You Happier!

While this often goes unnoticed, being in touch with yourself and having a deep understanding of why you think the way you think can really make you happier. Critical thinking can help you better understand yourself, and in turn, help you avoid any kind of negative or limiting beliefs, and focus more on your strengths. Being able to share your thoughts can increase your quality of life.

4. Form Well-Informed Opinions

There is no shortage of information coming at us from all angles. And that’s exactly why we need to use our critical thinking skills and decide for ourselves what to believe. Critical thinking allows us to ensure that our opinions are based on the facts, and help us sort through all that extra noise.

5. Better Citizens

One of the most inspiring critical thinking quotes is by former US president Thomas Jefferson: “An educated citizenry is a vital requisite for our survival as a free people.” What Jefferson is stressing to us here is that critical thinkers make better citizens, as they are able to see the entire picture without getting sucked into biases and propaganda.

6. Improves Relationships

While you may be convinced that being a critical thinker is bound to cause you problems in relationships, this really couldn’t be less true! Being a critical thinker can allow you to better understand the perspective of others, and can help you become more open-minded towards different views.

7. Promotes Curiosity

Critical thinkers are constantly curious about all kinds of things in life, and tend to have a wide range of interests. Critical thinking means constantly asking questions and wanting to know more, about why, what, who, where, when, and everything else that can help them make sense of a situation or concept, never taking anything at face value.

8. Allows For Creativity

Critical thinkers are also highly creative thinkers, and see themselves as limitless when it comes to possibilities. They are constantly looking to take things further, which is crucial in the workforce.

9. Enhances Problem Solving Skills

Those with critical thinking skills tend to solve problems as part of their natural instinct. Critical thinkers are patient and committed to solving the problem, similar to Albert Einstein, one of the best critical thinking examples, who said “It’s not that I’m so smart; it’s just that I stay with problems longer.” Critical thinkers’ enhanced problem-solving skills makes them better at their jobs and better at solving the world’s biggest problems. Like Einstein, they have the potential to literally change the world.

10. An Activity For The Mind

Just like our muscles, in order for them to be strong, our mind also needs to be exercised and challenged. It’s safe to say that critical thinking is almost like an activity for the mind — and it needs to be practiced. Critical thinking encourages the development of many crucial skills such as logical thinking, decision making, and open-mindness.

11. Creates Independence

When we think critically, we think on our own as we trust ourselves more. Critical thinking is key to creating independence, and encouraging students to make their own decisions and form their own opinions.

12. Crucial Life Skill

Critical thinking is crucial not just for learning, but for life overall! Education isn’t just a way to prepare ourselves for life, but it’s pretty much life itself. Learning is a lifelong process that we go through each and every day.

How to Think Critically

Now that you know the benefits of thinking critically, how do you actually do it?

How To Improve Your Critical Thinking

- Define Your Question: When it comes to critical thinking, it’s important to always keep your goal in mind. Know what you’re trying to achieve, and then figure out how to best get there.

- Gather Reliable Information: Make sure that you’re using sources you can trust — biases aside. That’s how a real critical thinker operates!

- Ask The Right Questions: We all know the importance of questions, but be sure that you’re asking the right questions that are going to get you to your answer.

- Look Short & Long Term: When coming up with solutions, think about both the short- and long-term consequences. Both of them are significant in the equation.

- Explore All Sides: There is never just one simple answer, and nothing is black or white. Explore all options and think outside of the box before you come to any conclusions.

How Is Critical Thinking Developed At School?

Critical thinking is developed in nearly everything we do. However, much of this important skill is encouraged to be practiced at school, and rightfully so! Critical thinking goes beyond just thinking clearly — it’s also about thinking for yourself.

When a teacher asks a question in class, students are given the chance to answer for themselves and think critically about what they learned and what they believe to be accurate. When students work in groups and are forced to engage in discussion, this is also a great chance to expand their thinking and use their critical thinking skills.

How Does Critical Thinking Apply To Your Career?

Once you’ve finished school and entered the workforce, your critical thinking journey only expands and grows from here!

Impress Your Employer

Employers value employees who are critical thinkers, ask questions, offer creative ideas, and are always ready to offer innovation against the competition. No matter what your position or role in a company may be, critical thinking will always give you the power to stand out and make a difference.

Careers That Require Critical Thinking

Some of many examples of careers that require critical thinking include:

- Human resources specialist

- Marketing associate

- Business analyst

Truth be told however, it’s probably harder to come up with a professional field that doesn’t require any critical thinking!

Photo by Oladimeji Ajegbile from Pexels

What is someone with critical thinking skills capable of doing.

Someone with critical thinking skills is able to think rationally and clearly about what they should or not believe. They are capable of engaging in their own thoughts, and doing some reflection in order to come to a well-informed conclusion.

A critical thinker understands the connections between ideas, and is able to construct arguments based on facts, as well as find mistakes in reasoning.

The Process Of Critical Thinking

The process of critical thinking is highly systematic.

What Are Your Goals?

Critical thinking starts by defining your goals, and knowing what you are ultimately trying to achieve.

Once you know what you are trying to conclude, you can foresee your solution to the problem and play it out in your head from all perspectives.

What Does The Future Of Critical Thinking Hold?

The future of critical thinking is the equivalent of the future of jobs. In 2020, critical thinking was ranked as the 2nd top skill (following complex problem solving) by the World Economic Forum .

We are dealing with constant unprecedented changes, and what success is today, might not be considered success tomorrow — making critical thinking a key skill for the future workforce.

Why Is Critical Thinking So Important?

Why is critical thinking important? Critical thinking is more than just important! It’s one of the most crucial cognitive skills one can develop.

By practicing well-thought-out thinking, both your thoughts and decisions can make a positive change in your life, on both a professional and personal level. You can hugely improve your life by working on your critical thinking skills as often as you can.

Related Articles

Developing Critical Thinking

- Posted January 10, 2018

- By Iman Rastegari

In a time where deliberately false information is continually introduced into public discourse, and quickly spread through social media shares and likes, it is more important than ever for young people to develop their critical thinking. That skill, says Georgetown professor William T. Gormley, consists of three elements: a capacity to spot weakness in other arguments, a passion for good evidence, and a capacity to reflect on your own views and values with an eye to possibly change them. But are educators making the development of these skills a priority?

"Some teachers embrace critical thinking pedagogy with enthusiasm and they make it a high priority in their classrooms; other teachers do not," says Gormley, author of the recent Harvard Education Press release The Critical Advantage: Developing Critical Thinking Skills in School . "So if you are to assess the extent of critical-thinking instruction in U.S. classrooms, you’d find some very wide variations." Which is unfortunate, he says, since developing critical-thinking skills is vital not only to students' readiness for college and career, but to their civic readiness, as well.

"It's important to recognize that critical thinking is not just something that takes place in the classroom or in the workplace, it's something that takes place — and should take place — in our daily lives," says Gormley.

In this edition of the Harvard EdCast, Gormley looks at the value of teaching critical thinking, and explores how it can be an important solution to some of the problems that we face, including "fake news."

About the Harvard EdCast

The Harvard EdCast is a weekly series of podcasts, available on the Harvard University iT unes U page, that features a 15-20 minute conversation with thought leaders in the field of education from across the country and around the world. Hosted by Matt Weber and co-produced by Jill Anderson, the Harvard EdCast is a space for educational discourse and openness, focusing on the myriad issues and current events related to the field.

An education podcast that keeps the focus simple: what makes a difference for learners, educators, parents, and communities

Related Articles

Roots of the School Gardening Movement

Student-centered learning, reading and the common core.

- Get started with computers

- Learn Microsoft Office

- Apply for a job

- Improve my work skills

- Design nice-looking docs

- Getting Started

- Smartphones & Tablets

- Typing Tutorial

- Online Learning

- Basic Internet Skills

- Online Safety

- Social Media

- Zoom Basics

- Google Docs

- Google Sheets

- Career Planning

- Resume Writing

- Cover Letters

- Job Search and Networking

- Business Communication

- Entrepreneurship 101

- Careers without College

- Job Hunt for Today

- 3D Printing

- Freelancing 101

- Personal Finance

- Sharing Economy

- Decision-Making

- Graphic Design

- Photography

- Image Editing

- Learning WordPress

- Language Learning

- Critical Thinking

- For Educators

- Translations

- Staff Picks

- English expand_more expand_less

Critical Thinking and Decision-Making - What is Critical Thinking?

Critical thinking and decision-making -, what is critical thinking, critical thinking and decision-making what is critical thinking.

Critical Thinking and Decision-Making: What is Critical Thinking?

Lesson 1: what is critical thinking, what is critical thinking.

Critical thinking is a term that gets thrown around a lot. You've probably heard it used often throughout the years whether it was in school, at work, or in everyday conversation. But when you stop to think about it, what exactly is critical thinking and how do you do it ?

Watch the video below to learn more about critical thinking.

Simply put, critical thinking is the act of deliberately analyzing information so that you can make better judgements and decisions . It involves using things like logic, reasoning, and creativity, to draw conclusions and generally understand things better.

This may sound like a pretty broad definition, and that's because critical thinking is a broad skill that can be applied to so many different situations. You can use it to prepare for a job interview, manage your time better, make decisions about purchasing things, and so much more.

The process

As humans, we are constantly thinking . It's something we can't turn off. But not all of it is critical thinking. No one thinks critically 100% of the time... that would be pretty exhausting! Instead, it's an intentional process , something that we consciously use when we're presented with difficult problems or important decisions.

Improving your critical thinking

In order to become a better critical thinker, it's important to ask questions when you're presented with a problem or decision, before jumping to any conclusions. You can start with simple ones like What do I currently know? and How do I know this? These can help to give you a better idea of what you're working with and, in some cases, simplify more complex issues.

Real-world applications

Let's take a look at how we can use critical thinking to evaluate online information . Say a friend of yours posts a news article on social media and you're drawn to its headline. If you were to use your everyday automatic thinking, you might accept it as fact and move on. But if you were thinking critically, you would first analyze the available information and ask some questions :

- What's the source of this article?

- Is the headline potentially misleading?

- What are my friend's general beliefs?

- Do their beliefs inform why they might have shared this?

After analyzing all of this information, you can draw a conclusion about whether or not you think the article is trustworthy.

Critical thinking has a wide range of real-world applications . It can help you to make better decisions, become more hireable, and generally better understand the world around you.

/en/problem-solving-and-decision-making/why-is-it-so-hard-to-make-decisions/content/

- Appointments

- Resume Reviews

- Undergraduates

- PhDs & Postdocs

- Faculty & Staff

- Prospective Students

- Online Students

- Career Champions

- I’m Exploring

- Architecture & Design

- Education & Academia

- Engineering

- Fashion, Retail & Consumer Products

- Fellowships & Gap Year

- Fine Arts, Performing Arts, & Music

- Government, Law & Public Policy

- Healthcare & Public Health

- International Relations & NGOs

- Life & Physical Sciences

- Marketing, Advertising & Public Relations

- Media, Journalism & Entertainment

- Non-Profits

- Pre-Health, Pre-Law and Pre-Grad

- Real Estate, Accounting, & Insurance

- Social Work & Human Services

- Sports & Hospitality

- Startups, Entrepreneurship & Freelancing

- Sustainability, Energy & Conservation

- Technology, Data & Analytics

- DACA and Undocumented Students

- First Generation and Low Income Students

- International Students

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Transfer Students

- Students of Color

- Students with Disabilities

- Explore Careers & Industries

- Make Connections & Network

- Search for a Job or Internship

- Write a Resume/CV

- Write a Cover Letter

- Engage with Employers

- Research Salaries & Negotiate Offers

- Find Funding

- Develop Professional and Leadership Skills

- Apply to Graduate School

- Apply to Health Professions School

- Apply to Law School

- Self-Assessment

- Experiences

- Post-Graduate

- Jobs & Internships

- Career Fairs

- For Employers

- Meet the Team

- Peer Career Advisors

- Social Media

- Career Services Policies

- Walk-Ins & Pop-Ins

- Strategic Plan 2022-2025

Critical Thinking: A Simple Guide and Why It’s Important

- Share This: Share Critical Thinking: A Simple Guide and Why It’s Important on Facebook Share Critical Thinking: A Simple Guide and Why It’s Important on LinkedIn Share Critical Thinking: A Simple Guide and Why It’s Important on X

Critical Thinking: A Simple Guide and Why It’s Important was originally published on Ivy Exec .

Strong critical thinking skills are crucial for career success, regardless of educational background. It embodies the ability to engage in astute and effective decision-making, lending invaluable dimensions to professional growth.

At its essence, critical thinking is the ability to analyze, evaluate, and synthesize information in a logical and reasoned manner. It’s not merely about accumulating knowledge but harnessing it effectively to make informed decisions and solve complex problems. In the dynamic landscape of modern careers, honing this skill is paramount.

The Impact of Critical Thinking on Your Career

☑ problem-solving mastery.

Visualize critical thinking as the Sherlock Holmes of your career journey. It facilitates swift problem resolution akin to a detective unraveling a mystery. By methodically analyzing situations and deconstructing complexities, critical thinkers emerge as adept problem solvers, rendering them invaluable assets in the workplace.

☑ Refined Decision-Making

Navigating dilemmas in your career path resembles traversing uncertain terrain. Critical thinking acts as a dependable GPS, steering you toward informed decisions. It involves weighing options, evaluating potential outcomes, and confidently choosing the most favorable path forward.

☑ Enhanced Teamwork Dynamics

Within collaborative settings, critical thinkers stand out as proactive contributors. They engage in scrutinizing ideas, proposing enhancements, and fostering meaningful contributions. Consequently, the team evolves into a dynamic hub of ideas, with the critical thinker recognized as the architect behind its success.

☑ Communication Prowess

Effective communication is the cornerstone of professional interactions. Critical thinking enriches communication skills, enabling the clear and logical articulation of ideas. Whether in emails, presentations, or casual conversations, individuals adept in critical thinking exude clarity, earning appreciation for their ability to convey thoughts seamlessly.

☑ Adaptability and Resilience

Perceptive individuals adept in critical thinking display resilience in the face of unforeseen challenges. Instead of succumbing to panic, they assess situations, recalibrate their approaches, and persist in moving forward despite adversity.

☑ Fostering Innovation

Innovation is the lifeblood of progressive organizations, and critical thinking serves as its catalyst. Proficient critical thinkers possess the ability to identify overlooked opportunities, propose inventive solutions, and streamline processes, thereby positioning their organizations at the forefront of innovation.

☑ Confidence Amplification

Critical thinkers exude confidence derived from honing their analytical skills. This self-assurance radiates during job interviews, presentations, and daily interactions, catching the attention of superiors and propelling career advancement.

So, how can one cultivate and harness this invaluable skill?

✅ developing curiosity and inquisitiveness:.

Embrace a curious mindset by questioning the status quo and exploring topics beyond your immediate scope. Cultivate an inquisitive approach to everyday situations. Encourage a habit of asking “why” and “how” to deepen understanding. Curiosity fuels the desire to seek information and alternative perspectives.

✅ Practice Reflection and Self-Awareness:

Engage in reflective thinking by assessing your thoughts, actions, and decisions. Regularly introspect to understand your biases, assumptions, and cognitive processes. Cultivate self-awareness to recognize personal prejudices or cognitive biases that might influence your thinking. This allows for a more objective analysis of situations.

✅ Strengthening Analytical Skills:

Practice breaking down complex problems into manageable components. Analyze each part systematically to understand the whole picture. Develop skills in data analysis, statistics, and logical reasoning. This includes understanding correlation versus causation, interpreting graphs, and evaluating statistical significance.

✅ Engaging in Active Listening and Observation:

Actively listen to diverse viewpoints without immediately forming judgments. Allow others to express their ideas fully before responding. Observe situations attentively, noticing details that others might overlook. This habit enhances your ability to analyze problems more comprehensively.

✅ Encouraging Intellectual Humility and Open-Mindedness:

Foster intellectual humility by acknowledging that you don’t know everything. Be open to learning from others, regardless of their position or expertise. Cultivate open-mindedness by actively seeking out perspectives different from your own. Engage in discussions with people holding diverse opinions to broaden your understanding.

✅ Practicing Problem-Solving and Decision-Making:

Engage in regular problem-solving exercises that challenge you to think creatively and analytically. This can include puzzles, riddles, or real-world scenarios. When making decisions, consciously evaluate available information, consider various alternatives, and anticipate potential outcomes before reaching a conclusion.

✅ Continuous Learning and Exposure to Varied Content:

Read extensively across diverse subjects and formats, exposing yourself to different viewpoints, cultures, and ways of thinking. Engage in courses, workshops, or seminars that stimulate critical thinking skills. Seek out opportunities for learning that challenge your existing beliefs.

✅ Engage in Constructive Disagreement and Debate:

Encourage healthy debates and discussions where differing opinions are respectfully debated.

This practice fosters the ability to defend your viewpoints logically while also being open to changing your perspective based on valid arguments. Embrace disagreement as an opportunity to learn rather than a conflict to win. Engaging in constructive debate sharpens your ability to evaluate and counter-arguments effectively.

✅ Utilize Problem-Based Learning and Real-World Applications:

Engage in problem-based learning activities that simulate real-world challenges. Work on projects or scenarios that require critical thinking skills to develop practical problem-solving approaches. Apply critical thinking in real-life situations whenever possible.

This could involve analyzing news articles, evaluating product reviews, or dissecting marketing strategies to understand their underlying rationale.

In conclusion, critical thinking is the linchpin of a successful career journey. It empowers individuals to navigate complexities, make informed decisions, and innovate in their respective domains. Embracing and honing this skill isn’t just an advantage; it’s a necessity in a world where adaptability and sound judgment reign supreme.

So, as you traverse your career path, remember that the ability to think critically is not just an asset but the differentiator that propels you toward excellence.

Why is Critical Thinking Important in Decision Making?

Annie Walls

Critical thinking is a crucial skill that plays a significant role in decision making. It involves analyzing information, evaluating different perspectives, and identifying biases and assumptions. By applying critical thinking, individuals can make informed and rational decisions, minimize errors and mistakes, and enhance their problem-solving skills. However, developing critical thinking skills comes with challenges such as overcoming cognitive biases, dealing with emotional influences, and developing open-mindedness. In this article, we will explore the definition of critical thinking, the role it plays in decision making, the benefits of applying critical thinking, and the challenges in developing critical thinking skills.

Key Takeaways

- Critical thinking is essential for making informed and rational decisions.

- It helps in analyzing information and data effectively.

- By evaluating different perspectives, critical thinking enables individuals to make well-rounded decisions.

- Identifying biases and assumptions is crucial for minimizing errors and mistakes in decision making.

- Developing critical thinking skills requires overcoming cognitive biases and emotional influences, and developing open-mindedness.

The Definition of Critical Thinking

Understanding the Concept of Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is a crucial cognitive skill that involves analyzing and evaluating information in a logical and systematic manner. It goes beyond simply accepting information at face value and instead encourages individuals to question, analyze, and interpret information to form well-reasoned judgments and make informed decisions.

To develop critical thinking skills, it is important to cultivate certain habits of mind, such as being open-minded, curious, and reflective. These habits enable individuals to approach problems and situations with a willingness to consider different perspectives, challenge assumptions, and seek out evidence to support their conclusions.

In addition, critical thinking involves the ability to recognize and avoid common cognitive biases that can cloud judgment and lead to flawed decision-making. By being aware of these biases, individuals can make more objective and rational decisions.

To further illustrate the importance of critical thinking, let's consider a table that presents some statistics on the impact of critical thinking in decision-making:

As we can see from the table, applying critical thinking in decision-making can lead to significant benefits, including making more accurate decisions, minimizing errors, and enhancing problem-solving skills.

In summary, understanding the concept of critical thinking is essential for effective decision-making. It involves analyzing information, evaluating different perspectives, and identifying biases and assumptions. By applying critical thinking, individuals can make informed and rational decisions, minimize errors, and enhance problem-solving skills.

Key Elements of Critical Thinking

Critical thinking involves several key elements that are essential for effective decision making. These elements include logic , reasoning , evidence , and analysis . Logic refers to the ability to think in a rational and systematic manner, making connections between ideas and drawing valid conclusions. Reasoning involves the ability to evaluate arguments and evidence, identifying strengths and weaknesses and making informed judgments. Evidence refers to the information and data that supports or contradicts a particular claim or argument. Analysis involves breaking down complex problems or situations into smaller parts, examining each part individually and then synthesizing the information to form a comprehensive understanding.

The Role of Critical Thinking in Decision Making

Analyzing Information and Data

Analyzing information and data is a crucial step in the decision-making process. It involves examining and interpreting relevant data to gain insights and make informed choices. By analyzing data, decision-makers can identify patterns, trends, and correlations that can guide their decisions. Data analysis allows for a systematic and objective evaluation of information, enabling decision-makers to assess the reliability and validity of the data. Additionally, it helps in identifying any gaps or inconsistencies in the data that may impact the decision-making process.

One effective way to present structured, quantitative data is through a Markdown table. A table provides a clear and organized format for presenting data, making it easier to compare and analyze different variables. When creating a table, it is important to ensure that it is succinct and properly formatted in Markdown.

Alternatively, a bulleted or numbered list can be used to present less structured content. Lists are useful for presenting qualitative points, steps, or a series of related items. They provide a concise and easy-to-read format for conveying information.

Remember to critically evaluate the data and information you analyze. Look for any biases or assumptions that may influence the interpretation of the data. Being aware of these biases and assumptions can help in making more objective and rational decisions.

Evaluating Different Perspectives

When making decisions, it is crucial to consider multiple perspectives to ensure a well-rounded evaluation. Evaluating different perspectives allows for a comprehensive analysis of the situation, taking into account various viewpoints and insights. This helps to minimize biases and assumptions that may hinder the decision-making process.

To effectively evaluate different perspectives, it can be helpful to use a bulleted list to outline the key points. This allows for a clear and concise presentation of the different viewpoints. Here are some important considerations:

- Expert opinions : Seek input from subject matter experts who can provide valuable insights based on their knowledge and experience.

- Stakeholder perspectives : Consider the viewpoints of all stakeholders involved, including customers, employees, and partners.

- Contrasting viewpoints : Explore opposing arguments and perspectives to gain a deeper understanding of the issue.

Remember, evaluating different perspectives is essential for making informed and rational decisions. It helps to broaden your understanding and consider various angles before reaching a conclusion.

Identifying Biases and Assumptions

Identifying biases and assumptions is a crucial aspect of critical thinking in decision making. Biases are inherent preferences or prejudices that can influence our judgment and decision-making process. They can be based on personal experiences, cultural influences, or societal norms. Assumptions , on the other hand, are beliefs or ideas that we take for granted without questioning their validity. They can be conscious or unconscious and can significantly impact the way we perceive information and make decisions.

To effectively identify biases and assumptions, it is important to approach decision-making with a critical mindset . This involves questioning our own beliefs and biases, as well as being open to different perspectives and viewpoints. By recognizing and challenging biases and assumptions, we can gain a more objective understanding of the situation and make more informed decisions.

In order to identify biases and assumptions, it can be helpful to use a combination of quantitative data and qualitative analysis . Quantitative data provides structured information that can help identify patterns and trends, while qualitative analysis allows for a deeper understanding of the underlying factors and influences. By utilizing both approaches, we can uncover hidden biases and assumptions that may be affecting our decision-making process.

Additionally, it is important to be aware of common biases and assumptions that can occur in decision making. Some examples include confirmation bias, where we seek out information that confirms our existing beliefs, and availability bias, where we rely on readily available information rather than considering all relevant data. By being mindful of these biases and assumptions, we can actively work towards minimizing their impact on our decision-making process.

Benefits of Applying Critical Thinking in Decision Making

Making Informed and Rational Decisions

Making informed and rational decisions is crucial in any decision-making process. It involves gathering and analyzing relevant information, considering different perspectives, and evaluating the potential outcomes. By making informed decisions, individuals can minimize the risks and uncertainties associated with their choices. It allows them to weigh the pros and cons, identify potential biases and assumptions, and make choices that align with their goals and values. Additionally, informed decision-making promotes accountability and responsibility, as individuals are aware of the reasons behind their decisions and can justify them if necessary.

Minimizing Errors and Mistakes

When it comes to decision making, minimizing errors and mistakes is crucial. Making informed and rational decisions can significantly reduce the chances of errors and ensure better outcomes. One effective way to achieve this is by analyzing and evaluating quantitative data . By implementing a structured and succinct Markdown table, decision makers can easily comprehend and compare the data, leading to more accurate judgments.

Additionally, using a numbered list can help in outlining the steps or factors that need to be considered in the decision-making process. This provides a clear and organized approach, minimizing the possibility of overlooking important aspects.

Tip: Always double-check the data and information used in the decision-making process to avoid errors and ensure reliable results.

By applying critical thinking skills and utilizing appropriate tools, decision makers can effectively minimize errors and mistakes, leading to more successful outcomes.

Enhancing Problem-Solving Skills

Enhancing problem-solving skills is a crucial aspect of applying critical thinking in decision making. By developing strong problem-solving skills, individuals are better equipped to analyze complex situations, identify potential solutions, and make informed decisions. Problem-solving skills involve the ability to break down problems into smaller, manageable parts, gather relevant information, evaluate different options, and select the most effective solution. It also requires creativity and the ability to think outside the box to come up with innovative solutions. By continuously honing problem-solving skills, individuals can become more efficient and effective decision-makers.

Challenges in Developing Critical Thinking Skills

Overcoming Cognitive Biases

Overcoming cognitive biases is crucial in decision making. Cognitive biases are inherent tendencies to think and make judgments in certain ways that can lead to errors and distortions. By recognizing and addressing these biases, individuals can improve the quality of their decision-making process. One effective way to overcome cognitive biases is to gather and analyze data objectively. This helps to minimize the influence of personal biases and allows for a more rational evaluation of information. Additionally, seeking diverse perspectives and opinions can help to challenge and counteract biases, as different viewpoints can provide alternative insights and considerations.

Dealing with Emotional Influences

When making decisions, it is important to be aware of the impact of emotions. Emotions can cloud judgment and lead to biased decision-making. Managing emotions effectively is crucial in critical thinking and decision-making processes.

One way to deal with emotional influences is to recognize and acknowledge emotions without letting them dictate the decision. By taking a step back and analyzing the situation objectively, individuals can make more rational and informed choices.

Another strategy is to seek input from others. By discussing the decision with trusted colleagues or mentors, individuals can gain different perspectives and insights that can help counteract emotional biases.

It is also important to consider the long-term consequences of decisions. Emotions often focus on short-term gratification, but critical thinking involves evaluating the potential outcomes and impacts in the future.

Remember, emotions are a natural part of the decision-making process, but being aware of their influence and actively managing them can lead to more effective and rational decisions.

Developing Open-Mindedness

Open-mindedness is a crucial aspect of critical thinking. It involves being receptive to new ideas, perspectives, and information, even if they challenge our existing beliefs or assumptions. Being open-minded allows us to consider alternative viewpoints and evaluate them objectively. By embracing open-mindedness, we can expand our understanding and make more informed decisions.

To develop open-mindedness, it can be helpful to engage in activities that expose us to diverse perspectives. This could include reading books or articles from different authors, attending seminars or workshops on various topics, or engaging in discussions with people who have different backgrounds or opinions.

Additionally, practicing active listening is essential in developing open-mindedness. By genuinely listening to others without judgment or interruption, we can better understand their viewpoints and broaden our own perspectives.

In summary, developing open-mindedness is a key component of critical thinking. It allows us to consider different perspectives, challenge our own biases, and make more informed decisions.

Developing critical thinking skills is essential in today's fast-paced and complex world. It allows individuals to analyze information, solve problems, and make informed decisions. However, there are several challenges that one may face in the process. One of the main challenges is the overwhelming amount of information available, making it difficult to distinguish between reliable sources and misinformation. Another challenge is the lack of time and opportunity to practice critical thinking skills in everyday life. Additionally, societal pressures and biases can hinder the development of independent and objective thinking. To overcome these challenges, it is important to engage in activities that promote critical thinking, such as reading diverse perspectives, engaging in thoughtful discussions, and seeking out new experiences. By developing strong critical thinking skills, individuals can navigate through the complexities of life with confidence and make well-informed decisions. Visit our website, Keynote Speaker James Taylor - Inspiring Creative Minds, to learn more about how to enhance your critical thinking skills and unlock your full potential.

In conclusion, critical thinking plays a crucial role in decision making. It enables individuals to analyze information, evaluate different perspectives, and make informed choices. By applying critical thinking skills, individuals can identify biases, recognize logical fallacies, and consider the potential consequences of their decisions. Critical thinking empowers individuals to make sound judgments and navigate complex situations effectively. Therefore, it is essential for individuals in various domains, including business, education, and everyday life, to cultivate and enhance their critical thinking abilities.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is critical thinking.

Critical thinking is the ability to analyze and evaluate information and arguments in a logical and systematic way to make informed decisions.

Why is critical thinking important in decision making?

Critical thinking helps individuals make rational and well-informed decisions by analyzing information, evaluating different perspectives, and identifying biases and assumptions.

How does critical thinking enhance problem-solving skills?

Critical thinking improves problem-solving skills by enabling individuals to identify and evaluate different solutions, anticipate potential obstacles, and make logical and effective decisions.

What are some common cognitive biases to overcome in critical thinking?

Some common cognitive biases include confirmation bias, availability bias, and anchoring bias. Overcoming these biases is important in developing objective and rational thinking.

How can emotional influences impact critical thinking?

Emotional influences can cloud judgment and lead to biased decision making. Developing self-awareness and emotional intelligence can help mitigate the impact of emotions on critical thinking.

How can open-mindedness be developed in critical thinking?

Open-mindedness can be developed by actively seeking out diverse perspectives, challenging one's own beliefs and assumptions, and being receptive to new ideas and evidence.

Popular Posts

Meilleur conférencier principal en teambuilding.

Les conférences virtuelles et les sommets peuvent être des moyens très efficaces pour inspirer, informer

Meilleur conférencier principal sur le bien-être

Les conférences sur le bien-être et la santé mentale sont essentielles pour promouvoir un environnement

Meilleur conférencier principal en communication

Les conférences virtuelles, les réunions et les sommets peuvent être un moyen très efficace d’inspirer,

Meilleur Conférencier en Stratégie

Les conférenciers en stratégie jouent un rôle crucial dans l’inspiration et la motivation des entreprises

Meilleur Conférencier Culturel

En tant que conférencier de keynote sur la culture, il est essentiel d’avoir un partenaire

Meilleur conférencier principal dans le domaine des soins de santé

Les conférenciers principaux en santé et bien-être jouent un rôle crucial dans l’industrie de la

James is a top motivational keynote speaker who is booked as a creativity and innovation keynote speaker, AI speaker , sustainability speaker and leadership speaker . Recent destinations include: Dubai , Abu Dhabi , Orlando , Las Vegas , keynote speaker London , Barcelona , Bangkok , Miami , Berlin , Riyadh , New York , Zurich , motivational speaker Paris , Singapore and San Francisco

Latest News

- 415.800.3059

- [email protected]

- Media Interviews

- Meeting Planners

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

FIND ME ON SOCIAL

© 2024 James Taylor DBA P3 Music Ltd.

- Departments, units, and programs

- College leadership

- Faculty and staff resources

- Inclusive Excellence

- LAS Strategic Plan

- Apply to LAS

- Liberal arts & sciences majors

- LAS Insider blog

- Admissions FAQs

- Parent resources

- Pre-college summer programs

Quick Links

Request info

- Academic policies and standing

- Advising and support

- College distinctions

- Dates and deadlines

- Intercollegiate transfers

- LAS Lineup student newsletter

- Programs of study

- Scholarships

- Certificates

- Student emergencies

Student resources

- Access and Achievement Program

- Career services

- First-Year Experience

- Honors program

- International programs

- Internship opportunities

- Paul M. Lisnek LAS Hub

- Student research opportunities

- Expertise in LAS

- Research facilities and centers

- Dean's Distinguished Lecture series

- Alumni advice

- Alumni award programs

- Get involved

- LAS Alumni Council

- LAS@Work: Alumni careers

- Study Abroad Alumni Networks

- Update your information

- Nominate an alumnus for an LAS award

- Faculty honors

- The Quadrangle Online

- LAS News email newsletter archive

- LAS social media

- Media contact in the College of LAS

- LAS Landmark Day of Giving

- About giving to LAS

- Building projects

- Corporate engagement

- Faculty support

- Lincoln Scholars Initiative

- Impact of giving

- Diversity, equity, and inclusion

Why is critical thinking important?

What do lawyers, accountants, teachers, and doctors all have in common?

What is critical thinking?

The Oxford English Dictionary defines critical thinking as “The objective, systematic, and rational analysis and evaluation of factual evidence in order to form a judgment on a subject, issue, etc.” Critical thinking involves the use of logic and reasoning to evaluate available facts and/or evidence to come to a conclusion about a certain subject or topic. We use critical thinking every day, from decision-making to problem-solving, in addition to thinking critically in an academic context!

Why is critical thinking important for academic success?

You may be asking “why is critical thinking important for students?” Critical thinking appears in a diverse set of disciplines and impacts students’ learning every day, regardless of major.

Critical thinking skills are often associated with the value of studying the humanities. In majors such as English, students will be presented with a certain text—whether it’s a novel, short story, essay, or even film—and will have to use textual evidence to make an argument and then defend their argument about what they’ve read. However, the importance of critical thinking does not only apply to the humanities. In the social sciences, an economics major , for example, will use what they’ve learned to figure out solutions to issues as varied as land and other natural resource use, to how much people should work, to how to develop human capital through education. Problem-solving and critical thinking go hand in hand. Biology is a popular major within LAS, and graduates of the biology program often pursue careers in the medical sciences. Doctors use critical thinking every day, tapping into the knowledge they acquired from studying the biological sciences to diagnose and treat different diseases and ailments.

Students in the College of LAS take many courses that require critical thinking before they graduate. You may be asked in an Economics class to use statistical data analysis to evaluate the impact on home improvement spending when the Fed increases interest rates (read more about real-world experience with Datathon ). If you’ve ever been asked “How often do you think about the Roman Empire?”, you may find yourself thinking about the Roman Empire more than you thought—maybe in an English course, where you’ll use text from Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra to make an argument about Roman imperial desire. No matter what the context is, critical thinking will be involved in your academic life and can take form in many different ways.

The benefits of critical thinking in everyday life

Building better communication.

One of the most important life skills that students learn as early as elementary school is how to give a presentation. Many classes require students to give presentations, because being well-spoken is a key skill in effective communication. This is where critical thinking benefits come into play: using the skills you’ve learned, you’ll be able to gather the information needed for your presentation, narrow down what information is most relevant, and communicate it in an engaging way.

Typically, the first step in creating a presentation is choosing a topic. For example, your professor might assign a presentation on the Gilded Age and provide a list of figures from the 1870s—1890s to choose from. You’ll use your critical thinking skills to narrow down your choices. You may ask yourself:

- What figure am I most familiar with?

- Who am I most interested in?

- Will I have to do additional research?

After choosing your topic, your professor will usually ask a guiding question to help you form a thesis: an argument that is backed up with evidence. Critical thinking benefits this process by allowing you to focus on the information that is most relevant in support of your argument. By focusing on the strongest evidence, you will communicate your thesis clearly.

Finally, once you’ve finished gathering information, you will begin putting your presentation together. Creating a presentation requires a balance of text and visuals. Graphs and tables are popular visuals in STEM-based projects, but digital images and graphics are effective as well. Critical thinking benefits this process because the right images and visuals create a more dynamic experience for the audience, giving them the opportunity to engage with the material.

Presentation skills go beyond the classroom. Students at the University of Illinois will often participate in summer internships to get professional experience before graduation. Many summer interns are required to present about their experience and what they learned at the end of the internship. Jobs frequently also require employees to create presentations of some kind—whether it’s an advertising pitch to win an account from a potential client, or quarterly reporting, giving a presentation is a life skill that directly relates to critical thinking.

Fostering independence and confidence

An important life skill many people start learning as college students and then finessing once they enter the “adult world” is how to budget. There will be many different expenses to keep track of, including rent, bills, car payments, and groceries, just to name a few! After developing your critical thinking skills, you’ll put them to use to consider your salary and budget your expenses accordingly. Here’s an example:

- You earn a salary of $75,000 a year. Assume all amounts are before taxes.

- 1,800 x 12 = 21,600

- 75,000 – 21,600 = 53,400

- This leaves you with $53,400

- 320 x 12 = 3,840 a year

- 53,400-3,840= 49,560

- 726 x 12 = 8,712

- 49,560 – 8,712= 40,848

- You’re left with $40,848 for miscellaneous expenses. You use your critical thinking skills to decide what to do with your $40,848. You think ahead towards your retirement and decide to put $500 a month into a Roth IRA, leaving $34,848. Since you love coffee, you try to figure out if you can afford a daily coffee run. On average, a cup of coffee will cost you $7. 7 x 365 = $2,555 a year for coffee. 34,848 – 2,555 = 32,293

- You have $32,293 left. You will use your critical thinking skills to figure out how much you would want to put into savings, how much you want to save to treat yourself from time to time, and how much you want to put aside for emergency funds. With the benefits of critical thinking, you will be well-equipped to budget your lifestyle once you enter the working world.

Enhancing decision-making skills

Choosing the right university for you.