- Liberty Fund

- Adam Smith Works

- Law & Liberty

- Browse by Author

- Browse by Topic

- Browse by Date

- Search EconLog

- Latest Episodes

- Browse by Guest

- Browse by Category

- Browse Extras

- Search EconTalk

- Latest Articles

- Liberty Classics

- Search Articles

- Books by Date

- Books by Author

- Search Books

- Browse by Title

- Biographies

- Search Encyclopedia

- #ECONLIBREADS

- College Topics

- High School Topics

- Subscribe to QuickPicks

- Search Guides

- Search Videos

- Library of Law & Liberty

- Home /

ECONLIB CEE

Creative Destruction

By richard alm and w. michael cox.

By Richard Alm and W. Michael Cox,

Joseph Schumpeter (1883–1950) coined the seemingly paradoxical term “creative destruction,” and generations of economists have adopted it as a shorthand description of the free market ’s messy way of delivering progress. In Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy (1942), the Austrian economist wrote:

The opening up of new markets, foreign or domestic, and the organizational development from the craft shop to such concerns as U.S. Steel illustrate the same process of industrial mutation—if I may use that biological term—that incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one. This process of Creative Destruction is the essential fact about capitalism. (p. 83)

Although Schumpeter devoted a mere six-page chapter to “The Process of Creative Destruction,” in which he described capitalism as “the perennial gale of creative destruction,” it has become the centerpiece for modern thinking on how economies evolve.

Schumpeter and the economists who adopt his succinct summary of the free market’s ceaseless churning echo capitalism’s critics in acknowledging that lost jobs, ruined companies, and vanishing industries are inherent parts of the growth system. The saving grace comes from recognizing the good that comes from the turmoil. Over time, societies that allow creative destruction to operate grow more productive and richer; their citizens see the benefits of new and better products, shorter work weeks, better jobs, and higher living standards.

Herein lies the paradox of progress. A society cannot reap the rewards of creative destruction without accepting that some individuals might be worse off, not just in the short term, but perhaps forever. At the same time, attempts to soften the harsher aspects of creative destruction by trying to preserve jobs or protect industries will lead to stagnation and decline, short-circuiting the march of progress. Schumpeter’s enduring term reminds us that capitalism’s pain and gain are inextricably linked. The process of creating new industries does not go forward without sweeping away the preexisting order.

Transportation provides a dramatic, ongoing example of creative destruction at work. With the arrival of steam power in the nineteenth century, railroads swept across the United States, enlarging markets, reducing shipping costs, building new industries, and providing millions of new productive jobs. The internal combustion engine paved the way for the automobile early in the next century. The rush to put America on wheels spawned new enterprises; at one point in the 1920s, the industry had swelled to more than 260 car makers. The automobile’s ripples spilled into oil, tourism, entertainment, retailing, and other industries. On the heels of the automobile, the airplane flew into our world, setting off its own burst of new businesses and jobs.

Americans benefited as horses and mules gave way to cars and airplanes, but all this creation did not come without destruction. Each new mode of transportation took a toll on existing jobs and industries. In 1900, the peak year for the occupation, the country employed 109,000 carriage and harness makers. In 1910, 238,000 Americans worked as blacksmiths. Today, those jobs are largely obsolete. After eclipsing canals and other forms of transport, railroads lost out in competition with cars, long-haul trucks, and airplanes. In 1920, 2.1 million Americans earned their paychecks working for railroads, compared with fewer than 200,000 today.

What occurred in the transportation sector has been repeated in one industry after another—in many cases, several times in the same industry. Creative destruction recognizes change as the one constant in capitalism. Sawyers, masons, and miners were among the top thirty American occupations in 1900. A century later, they no longer rank among the top thirty; they have been replaced by medical technicians, engineers, computer scientists, and others.

Technology roils job markets, as Schumpeter conveyed in coining the phrase “technological unemployment” ( Table 1 ). E-mail, word processors, answering machines, and other modern office technology have cut the number of secretaries but raised the ranks of programmers. The birth of the Internet spawned a need for hundreds of thousands of webmasters, an occupation that did not exist as recently as 1990. LASIK surgery often lets consumers throw away their glasses, reducing visits to optometrists and opticians but increasing the need for ophthalmologists. Digital cameras translate to fewer photo clerks.

Companies show the same pattern of destruction and rebirth. Only five of today’s hundred largest public companies were among the top hundred in 1917. Half of the top hundred of 1970 had been replaced in the rankings by 2000.

“The essential point to grasp is that in dealing with capitalism we are dealing with an evolutionary process,” Schumpeter wrote (p. 82).

The Power of Productivity

Entrepreneurship and competition fuel creative destruction. Schumpeter summed it up as follows:

The fundamental impulse that sets and keeps the capitalist engine in motion comes from the new consumers’ goods, the new methods of production or transportation, the new markets, the new forms of industrial organization that capitalist enterprise creates. (p. 83)

Entrepreneurs introduce new products and technologies with an eye toward making themselves better off—the profit motive. New goods and services, new firms, and new industries compete with existing ones in the marketplace, taking customers by offering lower prices, better performance, new features, catchier styling, faster service, more convenient locations, higher status, more aggressive marketing, or more attractive packaging. In another seemingly contradictory aspect of creative destruction, the pursuit of self-interest ignites the progress that makes others better off.

Producers survive by streamlining production with newer and better tools that make workers more productive. Companies that no longer deliver what consumers want at competitive prices lose customers, and eventually wither and die. The market’s “invisible hand”—a phrase owing not to Schumpeter but to Adam Smith —shifts resources from declining sectors to more valuable uses as workers, inputs, and financial capital seek their highest returns.

Through this constant roiling of the status quo, creative destruction provides a powerful force for making societies wealthier. It does so by making scarce resources more productive. The telephone industry employed 421,000 switchboard operators in 1970, when Americans made 9.8 billion long-distance calls. With advances in switching technology over the next three decades, the telecommunications sector could reduce the number of operators to 156,000 but still ring up 106 billion calls. An average operator handled only 64 calls a day in 1970. By 2000, that figure had increased to 1,861, a staggering gain in productivity . If they had to handle today’s volume of calls with 1970s technology, the telephone companies would need more than 4.5 million operators, or 3 percent of the labor force. Without the productivity gains, a long-distance call would cost six times as much.

The telephone industry is not an isolated example of creative destruction at work. In 1900, nearly forty of every hundred Americans worked in farming to feed a country of ninety million people. A century later, it takes just two out of every hundred workers. Despite one of history’s most thorough downsizings, the country has not gone hungry. The United States enjoys agricultural plenty, producing more meat, grain, vegetables, and dairy products than ever, thanks largely to huge advances in agricultural productivity.

Resources no longer needed to feed the nation have been freed to meet other consumer demands. Over the decades, workers no longer required in agriculture moved to the cities, where they became available to produce other goods and services. They started out in foundries, meatpacking plants, and loading docks in the early days of the Industrial Age. Their grandsons and granddaughters, living in an economy refashioned by creative destruction into the Information Age, are less likely to work in those jobs. They are making computers, movies, and financial decisions and providing a modern economy’s myriad other goods and services ( Table 2 ).

Over the past two centuries, the Western nations that embraced capitalism have achieved tremendous economic progress as new industries supplanted old ones. Even with the higher living standards, however, the constant flux of free enterprise is not always welcome. The disruption of lost jobs and shuttered businesses is immediate, while the payoff from creative destruction comes mainly in the long term. As a result, societies will always be tempted to block the process of creative destruction, implementing policies to resist economic change.

Attempts to save jobs almost always backfire. Instead of going out of business, inefficient producers hang on, at a high cost to consumers or taxpayers. The tinkering shortcircuits market signals that shift resources to emerging industries. It saps the incentives to introduce new products and production methods, leading to stagnation, layoffs, and bankruptcies. The ironic point of Schumpeter’s iconic phrase is this: societies that try to reap the gain of creative destruction without the pain find themselves enduring the pain but not the gain.

About the Authors

W. Michael Cox is senior vice president and chief economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. Richard Alm is an economics writer at the Dallas Fed. They are coauthors of Myths of Rich and Poor (1999).

Further Reading

Related content, thomas mccraw on schumpeter, innovation, and creative destruction.

Anthropological Theory Commons

I consent to receiving email updates from at-commons.com blog when new posts are published. My info will not be used for any other purposes.

- Introduction: Creative Destruction, Destructive Creation

Ognjen Kojanic and Ana Flavia Badue

In Grundrisse , Karl Marx (1993: 750) conceptualizes violent destruction as a condition of capital’s self-preservation: as new organizational forms and technologies emerge, old ones need to be replaced. This process is an outcome of ‘bitter contradictions’, he writes. ‘These contradictions, of course, lead to explosions, crises, in which momentary suspension of all labour and annihilation of a great part of the capital violently lead it back to the point where it is enabled [to go on] fully employing its productive powers without committing suicide’. The contradictions Marx has discussed are inherent to capitalism. In his analysis, he identifies the tendency of the rate of profit to fall at the same time that productivity and wealth increases as one of the key laws that define the circulation and reproduction of capital. To counter that tendency, capitalists need to tinker with the ratio of capital to living labour. They can extend the time they employ the labour power they purchase in order to expand absolute surplus value. But since the expansion of absolute surplus value quickly reaches its limits, they have to expand relative surplus value by investing in machinery or revolutionizing the labour process. Taking this into account, destruction appears as a systemic element of capitalism, visible not only in large-scale crises, but also in the everyday functioning of capitalist enterprises.

Joseph Schumpeter carries this conception further by positing that the revolutionization of the economic structure requires capitalist firms to unleash the ruinous energies of capitalism in the process of ‘creative destruction’. Schumpeter (1994: 31-32) emphasizes that ‘capitalist economy is not and cannot be stationary…. It is incessantly being revolutionized from within by new enterprise, i.e., by the intrusion of new commodities or new methods of production or new commercial opportunities into the industrial structure as it exists at any moment. Any existing structure and all the conditions of doing business are always in a process of change. Every situation is being upset before it has had time to work itself out. Economic progress, in capitalist society, means turmoil’. Schumpeter took the destruction unleashed by capitalism as its productive and creative moments, while Marx understood the creation of new forms of accumulation as destructive.

Neither Schumpeter nor Marx expected capitalism to reproduce itself forever—the former ascribed capitalism’s upcoming undoing to its successes, the latter to its failures—but we have yet to see a broad-scale replacement of capitalism as the reigning economic system. We have, however, seen multiple crises since the time they wrote, which have brought about bouts of creative destruction that have spanned continents or even the whole planet. Crisis, instability, and destruction, therefore, are not unexpected outcomes of a capitalist system that is not working well, but conditions that enable capitalism’s continued survival. As David Harvey (2010: 71) put it, writing after the most recent crisis that had unfolded on a planetary scale, ‘crises are, in effect, not only inevitable but also necessary, since this is the only way in which balance can be restored and the internal contradictions of capital accumulation be at least temporarily resolved’. According to Harvey, large-scale crises of capitalism require abandoning some spaces of accumulation in favour of finding new outlets for capital to regain lost profit rates. The spatial mobility of capital depends on the solidification of credit systems that make it liquid and flexible to colonize new spaces and new enterprises. Consequently, new forms of colonization and imperialism emerge, reconfiguring political and economic geographies. Factories in Eastern Europe, infrastructural projects in the Middle East, and rural settings in Latin America are some of the spaces where the infusion of capital reshapes local social relations, at the same time that these local relations shape how capital can be deployed.

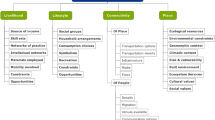

Like Harvey, various social scientists have taken up the notion of creative destruction to question the cycles of production and destruction under capitalist economies. Theorizing this process in the abstract requires one to focus on the way capital operates in society: the way political-economic incentives shape the behaviours of enterprises and individuals as the capitalist system as a whole continues on. Ethnographically, however, we can focus on smaller scales to trace the contradictions between creation and destruction that create disruptions in the lives of individuals and communities. Ethnographies of creative destruction reveal that contradictions appear in different moments, not only those of crisis. The underlying argument of the ethnographic pieces that compose this collection is that social phenomena are permeated by contradictory combinations of creative and destructive processes. Capitalism endures by absorbing mundane examples of creative and destructive processes into circuits of capital accumulation. These ethnographic cases show that such appropriation is silent, granular, as well as full of problems and obstacles.

Moreover, ethnographies enable us to describe and understand how the complex and variegated consequences of the destruction are, also, facilitators of capitalist circulation and accumulation. Ethnography offers us opportunities to theorize the lived experiences of the coexisting cycles of production and destruction by shedding light on everyday fluxes, flows, circuits, and micro-interactions that characterize capitalism and do not necessarily appear to conform to its logic at first glance. The ethnographic approach is also important for unravelling the lingering effects of destructive processes, as it enables us to conceptualize crisis and instability as ongoing, shapeshifting, and moving processes—not one-time-only events. In this sense, material and geographical ruins that are constantly produced constitute a major lens for conceptualizing the workings of capitalism and the creation of unevenness that it entails. As Dawdy (2010: 772) puts it, focusing on ruins and ruination reveals ‘the failures and impermanency of capitalism and the necessary poverty it engenders temporally or spatially, in contrast to its promises of ever-expanding flow and possibilities of social uplift’.

If the accelerated tempo of destruction under capitalism continuously alters the ways we interact with our lived environments, how can we theorize the instabilities and unevenness that permeate various objects and geographies? With this question in mind, the essays presented here focus on lifeworlds in a variety of ethnographic settings that stand at the intersections of decay and innovation, investment and deprivation, catching up and making do.

Ana Flavia Badue’s essay focuses on startups that aim to replicate Silicon Valley’s technologies business models in rural Brazil. By exploring how entrepreneurs develop digital and algorithmic devices with the expectation of provoking irreversible transformations in industrial farming, Badue argues that crises and destruction are converted by the Brazilian rural entrepreneurs into positive forms of accumulation and of modernization.

Ognjen Kojanic analyses the gradual replacement of machines in a worker-owned metalworking company in Croatia. Metalworking technologies of different generations coexist as necessary for production in this company. To understand why creative destruction operates in fits and starts, Kojanic argues that it is necessary both to situate the company within the workings of peripheral capitalism and to pay attention to ideas and practices of machine use in the company.

Turning to the coalfields of central Appalachia, Bradley Jones examines the economic and ecological forms that emerge from capitalism’s damaged landscapes. He treats creative destruction as a capacious analytic that can help us better understand ongoing processes of ruination and recovery, offering a window into worlds that capital has made, unmade, and which are being remade once more.

The commentary by Kedron Thomas parses out the term creative destruction. While attention to destruction is evident in many ethnographies, including the accounts in this collection, Thomas focuses on what creative means. How come creativity is discursively constructed as a capitalist trait and what are examples of creativity beyond it? If Schumpeterian discourse asks us to celebrate the creativity of entrepreneurs in capitalism, Thomas invites us to be mindful of alternative figurations of creativity, including in the examples analysed by Badue, Kojanic, and Jones.

Taken together, these essays reveal how capitalism is constantly re-crafted through the continuous production of scraps, disruptions, machinery replacement, and factory expansions. They show how anthropologists can contribute to the study of creative destruction by paying attention to uneven geographies, variegated outcomes for laborers, and the multi-scalar political-economic responses it engenders.

Acknowledgments

The idea for a collection of essays about creative destruction grew out of a panel at the Spring meeting of AES, ALLA, and ABA under the title ‘Ethnographic Futures’, held at Washington University in St. Louis, March 14-16, 2019. The panel, entitled ‘Crumbling Materials, Uneven Geographies: Destruction of Capitalism’, was organized by Hazal Corak. Earlier versions of the contributions by Ognjen Kojanic and Ana Badue were presented there.

Dawdy SL (2010) Clockpunk Anthropology and the Ruins of Modernity. Current Anthropology 51(6): 761–793.

Harvey D (2010) The Enigma of Capital: And the Crises of Capitalism . New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Marx K (1993) Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy . Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Schumpeter JA (1994) Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy . London: Routledge.

Ognjen Kojanic and Ana Flavia Badue (2020) 'Introduction: Creative Destruction, Destructive Creation', Anthropological Theory Commons. url:

We use cookies to enhance our website for you. Proceed if you agree to this policy or learn more about it.

- Essay Database >

- Essay Examples >

- Essays Topics >

- Essay on Money

Free Creative Destruction Essay Example

Type of paper: Essay

Topic: Money , Washing , Payment , Transaction , Internet , Development , Vehicles , Workplace

Published: 12/16/2020

ORDER PAPER LIKE THIS

Negative impact

The development of washing machines had a negative impact on my job as a house help. My duties as a house help included washing my employers’ clothes and utensils. As a house help, I used to ensure the house of my employer was clean and wash their clothes since they were busy. Washing my employer’s clothes formed one of my main duties, and as such with the development of the washing machine, I lost my job. My services such as washing clothes were replaced with the development of the washing machines that could easily wash many clothes at a time. The neighbors could also use the washing machine brought by my employer and as such, I had nowhere to search for a job. Creative destruction, in this case, had a negative impact on me as I lost my source of income that paid my bills. Because I had no other job, I had a difficult time trying to pay my bills. My employer, on the other hand, benefitted from the development of the washing machines as they could use the machine at their disposal. The washing machine they bought could wash their clothes at any time of the day and what they needed was simply to operate it. Operating a washing machine is easier than giving instructions to the man who can easily forget and as such, they were saved much by the washing machine that they could just operate. The development of the washing machine was unfair to me but fair to my employees who never wasted money on paying a house help.

Positive impact

Online payment systems are replacing the traditional payment systems or transaction processes that need an institution or individual to authorize the transaction. The traditional payment systems required an individual to go to the financial institutions or banks for the transaction to occur. Some of the activities that made one go to the bank or the bank outlets included sending individual cash, depositing cash and paying bills. The development of online payment systems has helped me as a businessperson who does many kinds of transactions. The traditional transaction systems are soon being phased out of the market and with time, online payment or transaction systems will form one of the main mechanisms of the transaction. Online payment systems are replacing traditional payment systems and as such, businesspersons are greatly benefitting. As a businessman, I benefitted since online transaction systems are convenient, mobile and upholds privacy. Online payment systems also help in saving time as I do not need to go to the banks to send money to an individual or pay my bills. The online payment systems also operate at reduced costs compared to going to the banks or any financial institutions. The development of the online payment systems that is slowly replacing the traditional payment or transaction system has a negative impact on the cashiers as it has rendered most of the cashiers jobless. The development of the online transaction system is fair to the people as it is the best for the society. However, it should be regulated so that it does not render many people jobless. The development of online transaction system has improved efficiency in the financial sector and led to the development of the economy since work is made easier.

Cite this page

Share with friends using:

Removal Request

Finished papers: 692

This paper is created by writer with

If you want your paper to be:

Well-researched, fact-checked, and accurate

Original, fresh, based on current data

Eloquently written and immaculately formatted

275 words = 1 page double-spaced

Get your papers done by pros!

Other Pages

Dubai essays, caseload essays, lapper essays, mesophyll essays, hierarchism essays, fogram essays, inexistence essays, geste essays, covin essays, experiencer essays, jiva essays, pocketing essays, loudness essays, new experience essays, cardinal virtues essays, feist essays, parenting challenges after a divorce essay examples, the industrial system and union essay examples, sexuality in the media essay example, merry homes inc v chi hung luu essay, social responsibility essay examples, is your chocolate the result of unfair exploitation of child labor case study examples, course work on community health nursing, ethics essay 4, report on stakeholder or agency theory, racism sexism and media article review example, course work on serious computer crimes, example of essay on money and banking assignment, research paper on reconstruction of the amendments, creative writing on yemen, example of running my own company personal statement, quantitative easing essay example, example of growing up in concentration camps essay, sample essay on organizations and behavior, how to be a ceo essay sample, the faces of the modern sport tourism literature review, free critical thinking on the role of nutrition in pregnancy with sickle cell disease, good example of movie review on movie critique, the rights of woman analysis essay, amenhotep research papers, spirit of god research papers, teen pregnancy rate research papers.

Password recovery email has been sent to [email protected]

Use your new password to log in

You are not register!

By clicking Register, you agree to our Terms of Service and that you have read our Privacy Policy .

Now you can download documents directly to your device!

Check your email! An email with your password has already been sent to you! Now you can download documents directly to your device.

or Use the QR code to Save this Paper to Your Phone

The sample is NOT original!

Short on a deadline?

Don't waste time. Get help with 11% off using code - GETWOWED

No, thanks! I'm fine with missing my deadline

Three Essays on Creative Destruction

- Igami, Mitsuru

- Advisor(s): Leamer, Edward

This dissertation aims to advance our knowledge of long-run economic changes. It consists of three essays on strategic industry dynamics in retail services, agricultural commodities, and high-tech manufacturing, respectively. Although creative destruction is commonly understood as the replacement of old technologies by new ones, its true significance lies not in the transition of technologies per se but in either the reluctance or inability of old winners to innovate when faced with new challengers. Hence I emphasize the incumbent-entrant rivalry as the common theme across these essays.

Essay 1 assesses the impact of the entry of large supermarkets on incumbents of various sizes. Contrary to the conventional notion that big stores drive small rivals out of the market, data from Tokyo in the 1990s show that large supermarkets' entry induces the exit of existing large and medium-size competitors, but improves the survival rate of small supermarkets. These findings highlight the role of store size as an important dimension of product differentiation and caution against size-based entry regulations.

Essay 2 studies the impact of international market structure on commodity prices, using a standard oligopoly model and exploiting historical variations in the structure of the international coffee bean market. The results suggest that, of the 75% drop in the real coffee price between 1988 and 2001, the end of a cartel treaty explains 49 points and the emergence of Vietnam as a major exporter explains another 9 points. I then discuss policy implications for competition, trade, and aid.

Essay 3 investigates why incumbent firms innovate more slowly than entrants. Theories predict cannibalization between existing and new products delays incumbents' innovation, whereas preemptive motives accelerate it, and incumbents' cost (dis)advantage would further reinforce these tendencies. To empirically quantify these three forces, I develop and estimate a dynamic oligopoly model using a unique panel dataset of hard disk drive (HDD) manufacturers (1981&ndash98). The results suggest that despite strong preemptive motives and a substantial cost advantage over entrants, incumbents are reluctant to innovate because of cannibalization, which can explain at least 51% of the incumbent-entrant timing gap. I then discuss managerial and public-policy implications.

Enter the password to open this PDF file:

- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

Become an FT subscriber

Try unlimited access Only $1 for 4 weeks

Then $75 per month. Complete digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Cancel anytime during your trial.

- Global news & analysis

- Expert opinion

- Special features

- FirstFT newsletter

- Videos & Podcasts

- Android & iOS app

- FT Edit app

- 10 gift articles per month

Explore more offers.

Standard digital.

- FT Digital Edition

Premium Digital

Print + premium digital, weekend print + standard digital, weekend print + premium digital.

Today's FT newspaper for easy reading on any device. This does not include ft.com or FT App access.

- Global news & analysis

- Exclusive FT analysis

- FT App on Android & iOS

- FirstFT: the day's biggest stories

- 20+ curated newsletters

- Follow topics & set alerts with myFT

- FT Videos & Podcasts

- 20 monthly gift articles to share

- Lex: FT's flagship investment column

- 15+ Premium newsletters by leading experts

- FT Digital Edition: our digitised print edition

- Weekday Print Edition

- Videos & Podcasts

- Premium newsletters

- 10 additional gift articles per month

- FT Weekend Print delivery

- Everything in Standard Digital

- Everything in Premium Digital

Essential digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

- 10 monthly gift articles to share

- Everything in Print

Complete digital access to quality FT journalism with expert analysis from industry leaders. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

Terms & Conditions apply

Explore our full range of subscriptions.

Why the ft.

See why over a million readers pay to read the Financial Times.

International Edition

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Slovenščina

- Science & Tech

- Russian Kitchen

Le Corbusier’s triumphant return to Moscow

The exhibition of French prominent architect Le Corbusier, held in The Pushkin Museum, brings together the different facets of his talent. Source: ITAR-TASS / Stanislav Krasilnikov

The largest Le Corbusier exhibition in a quarter of a century celebrates the modernist architect’s life and his connection with the city.

Given his affinity with Moscow, it is perhaps surprising that the city had never hosted a major examination of Le Corbusier’s work until now. However, the Pushkin Museum and the Le Corbusier Fund have redressed that discrepancy with the comprehensive exhibition “Secrets of Creation: Between Art and Architecture,” which runs until November 18.

Presenting over 400 exhibits, the exhibition charts Le Corbusier’s development from the young man eagerly sketching buildings on a trip around Europe, to his later years as a prolific and influential architect.

The exhibition brings together the different facets of his talent, showing his publications, artwork and furniture design alongside photographs, models and blueprints of his buildings.

Russian art reveals a new brave world beyond the Black Square

Art-Moscow fair targets younger art collectors

In pictures: 20th century in photographs: 1918-1940

Irina Antonova, director of the Pushkin Museum, said, “It was important for us to also exhibit his art. People know Le Corbusier the architect, but what is less well know is that he was also an artist. Seeing his art and architecture together gives us an insight into his mind and his thought-processes.”

What becomes obvious to visitors of the exhibition is that Le Corbusier was a man driven by a single-minded vision of how form and lines should interact, a vision he was able to express across multiple genres.

The upper wings of the Pushkin Museum are separated by the central stairs and two long balconies. The organizers have exploited this space, allowing comparison of Le Corbusier’s different art forms. On one side there are large paintings in the Purist style he adapted from Cubism, while on the other wall there are panoramic photographs of his famous buildings.

Le Corbusier was a theorist, producing many pamphlets and manifestos which outlined his view that rigorous urban planning could make society more productive and raise the average standard of living.

It was his affinity with constructivism, and its accompanying vision of the way architecture could shape society, which drew him to visit the Soviet Union, where, as he saw it, there existed a “nation that is being organized in accordance with its new spirit.”

The exhibition’s curator Jean-Louis Cohen explains that Le Corbusier saw Moscow as “somewhere he could experiment.” Indeed, when the architect was commissioned to construct the famous Tsentrosoyuz Building, he responded by producing a plan for the entire city, based on his concept of geometric symmetry.

Falling foul of the political climate

He had misread the Soviet appetite for experimentation, and as Cohen relates in his book Le Corbusier, 1887-1965, drew stinging attacks from the likes of El Lissitsky, who called his design “a city on paper, extraneous to living nature, located in a desert through which not even a river must be allowed to pass (since a curve would contradict the style).”

Not to be deterred, Le Corbusier returned to Moscow in 1932 and entered the famous Palace of the Soviets competition, a skyscraper that was planned to be the tallest building in the world.

This time he fell foul of the changing political climate, as Stalin’s growing suspicion of the avant-garde led to the endorsement of neo-classical designs for the construction, which was ultimately never built due to the Second World War.

Situated opposite the proposed site for the Palace of the Soviets, the exhibition offers a tantalizing vision of what might have been, presenting scale models alongside Le Corbusier’s plans, and generating the feeling of an un-built masterpiece.

Despite Le Corbusier’s fluctuating fortunes in Soviet society, there was one architect who never wavered in his support . Constructivist luminary Alexander Vesnin declared that the Tsentrosoyuz building was the "the best building to arise in Moscow for over a century.”

The exhibition sheds light on their professional and personal relationship, showing sketches and letters they exchanged. In a radical break from the abstract nature of most of Le Corbusier’s art, this corner of the exhibition highlights the sometimes volatile architect’s softer side, as shown through nude sketches and classical still-life paintings he sent to Vesnin.

“He was a complex person” says Cohen. “It’s important to show his difficult elements; his connections with the USSR, with Mussolini. Now that relations between Russia and the West have improved, we can examine this. At the moment there is a new season in Le Corbusier interpretation.” To this end, the exhibition includes articles that have never previously been published in Russia, as well as Le Corbusier’s own literature.

Completing Le Corbusier’s triumphant return to Russia is a preview of a forthcoming statue, to be erected outside the Tsentrosoyuz building. Even if she couldn’t quite accept his vision of a planned city, Moscow is certainly welcoming him back.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox

This website uses cookies. Click here to find out more.

- Rebuilding of Moscow

Texts Images Visual Essays Video Music Other Resources

Subject essay: Lewis Siegelbaum

The capital city of both the RSFSR and the USSR, Moscow also served under Stalin as a beacon for world socialism. But Moscow was a nearly 800-year old city, with dozens of churches and residential structures dating from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, many narrow twisting lanes, and in a preponderance of wooden, brick, and stone buildings from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The “Master Plan for the Reconstruction of the City of Moscow,” devised by a commission under Lazar Kaganovich and co-signed by Stalin and Viacheslav Molotov on July 10, 1935, was intended as an “offensive against the old Moscow” that would utterly transform the city. Four years in the making, the plan called for the expansion of the city’s area from 285 to 600 square kilometers that would take in mostly farmland to the south and west beyond the Lenin (a.k.a. Sparrow) Hills. It involved sixteen major highway projects, the construction of “several monumental buildings of state-wide significance,” and fifteen million square meters of new housing to accommodate a total population of approximately five million. Surrounding the city would be a green belt up to a width of ten kilometers.

Even while the master plan was being drawn up, old Moscow was giving way to the new. One of the showpieces of the new Moscow was to be the Moscow Metro[politen] which broke ground in March 1932 and went into service on May 14, 1935. A second project begun in the early 1930s was the Moscow-Volga Canal, built by an army of prison laborers numbering 200,000 and opened in July 1937. Yet another project, for a monumental Palace of Soviets capable of hosting meetings of up to 15,000 people, was the subject of an architectural competition held in 1931. Entries were received from 160 Soviet and foreign architects including Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier. In June 1933, the jury headed by Molotov awarded the project to the Soviet architect, Boris Iofan. His terraced, colonnaded palace was to be the tallest building in the world, soaring eight meters above the recently completed Empire State Building. It was to be crowned with a massive, 90-meter-tall statue of Lenin.

The site selected for the colossus was, symbolically enough, the ground on which the Cathedral of Christ the Redeemer had stood before its demolition in 1931. This was one of many churches and religious abbeys destroyed in the frenzy to make over the capital. Work on the Palace of Soviets commenced in 1935 and continued until the Nazi invasion. In 1960 a giant outdoor heated swimming pool, the biggest in the Soviet Union (and reputedly, the world), opened on the site. It, in turn, gave way in the 1990s to a replica of the cathedral which was constructed under the auspices of Moscow’s flamboyant mayor, Iurii Luzhkov.

Comments are closed.

- Abolition of Legal Abortion

- Childhood under Stalin

- Creation of the Ethnic Republics

- The Great Terror

- Pilots and Explorers

- Popular Front

- Rehabilitation of Cossack Divisions

- Second Kolkhoz Charter

- Stalin Constitution

- Upheaval in the Opera

- Year of the Stakhanovite

Reimagining Design with Nature: ecological urbanism in Moscow

- Reflective Essay

- Published: 10 September 2019

- Volume 1 , pages 233–247, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

- Brian Mark Evans ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1420-1682 1

978 Accesses

2 Citations

Explore all metrics

The twenty-first century is the era when populations of cities will exceed rural communities for the first time in human history. The population growth of cities in many countries, including those in transition from planned to market economies, is putting considerable strain on ecological and natural resources. This paper examines four central issues: (a) the challenges and opportunities presented through working in jurisdictions where there are no official or established methods in place to guide regional, ecological and landscape planning and design; (b) the experience of the author’s practice—Gillespies LLP—in addressing these challenges using techniques and methods inspired by McHarg in Design with Nature in the Russian Federation in the first decade of the twenty-first century; (c) the augmentation of methods derived from Design with Nature in reference to innovations in technology since its publication and the contribution that the art of landscape painters can make to landscape analysis and interpretation; and (d) the application of this experience to the international competition and colloquium for the expansion of Moscow. The text concludes with a comment on how the application of this learning and methodological development to landscape and ecological planning and design was judged to be a central tenant of the winning design. Finally, a concluding section reflects on lessons learned and conclusions drawn.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Principles for public space design, planning to do better

A transformative shift in urban ecology toward a more active and relevant future for the field and for cities

Acknowledgements

The landscape team from Gillespies Glasgow Studio (Steve Nelson, Graeme Pert, Joanne Walker, Rory Wilson and Chris Swan) led by the author and all our collaborators in the Capital Cities Planning Group.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Mackintosh School of Architecture, The Glasgow School of Art, 167 Renfrew Street, Glasgow, G3 6BY, UK

Brian Mark Evans

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Brian Mark Evans .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Evans, B.M. Reimagining Design with Nature: ecological urbanism in Moscow. Socio Ecol Pract Res 1 , 233–247 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42532-019-00031-5

Download citation

Received : 17 March 2019

Accepted : 13 August 2019

Published : 10 September 2019

Issue Date : October 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s42532-019-00031-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Design With Nature

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Home — Essay Samples — Geography & Travel — Travel and Tourism Industry — The History of Moscow City

The History of Moscow City

- Categories: Russia Travel and Tourism Industry

About this sample

Words: 614 |

Published: Feb 12, 2019

Words: 614 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Geography & Travel

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

13 pages / 6011 words

1 pages / 657 words

3 pages / 1208 words

6 pages / 3010 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Travel and Tourism Industry

Traveling is one of the most enriching experiences one can have. It exposes you to new cultures, customs, and ways of thinking. However, it can also be challenging and unpredictable, making it a true adventure. As a college [...]

Exploring foreign lands has always been a fascinating aspect of human curiosity. It is a desire to discover new cultures, traditions, and landscapes that are different from one's own. The experience of traveling to foreign lands [...]

Travelling is a topic that has been debated for centuries, with some arguing that it is a waste of time and money, while others believe that it is an essential part of life. In this essay, I will argue that travelling is not [...]

Traveling is an enriching experience that allows individuals to explore new cultures, meet people from different backgrounds, and broaden their perspectives. In the summer of 2019, I had the opportunity to embark on an amazing [...]

When planning a business trip all aspects and decisions rely heavily on the budget set by the company for the trip. Once Sandfords have confirmed the location careful consideration should be used to choose the travel method and [...]

4Sex Tourism in ThailandAs we enter a new millenium the post-colonial nations in the world are still searching for ways to compete in an increasingly globalized, consumption driven economic environment. Many developing countries [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Creative destruction (German: schöpferische Zerstörung) is a concept in economics that describes a process in which new innovations replace and make obsolete older innovations. ... (2006) edited a collection of essays under the title Against Theater: Creative destruction on the modernist stage.

This is a simple example of creative destruction theory which, as defined in the book The Power of Creative Destruction (Aghion, Antonin and Bunel, 2021), " is the process by which new innovations continually emerge and render existing technologies obsolete ". Individuals' changing needs and wants are what drive creative destruction.

The Power of Creative Destruction: Economic Upheaval and the Wealth of Nations, by Philippe Aghion, Céline Antonin and Simon Bunel, translated by Jodie Cohen-Tanugi, Belknap Press, RRP$35/ £28. ...

Joseph Schumpeter (1883-1950) coined the seemingly paradoxical term "creative destruction," and generations of economists have adopted it as a shorthand description of the free market's messy way of delivering progress. In Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy (1942), the Austrian economist wrote: The opening up of new markets, foreign or domestic, and the organizational development ...

The Economics of Creative Destruction. paid, and "bad" firms, where all workers are poorly paid (the so-called Mc" yeKns i -McDd l noa s nomyoce ) " . Growth Measurement and Growth Decline. One of the most worrying trends in recent years has been the decline in pro.

Creative destruction is a term coined by Joseph Shumpeter to describe the growth in a capitalist economy that comes from disruptive innovation. A defining characteristic of this idea is that a loss of jobs due innovation will be made up by a net gain of new jobs created by that innovation. A reasonable argument could be made that the nature ...

6 The Economics of Creative Destruction 259. 421,000 telephone switchboard operators, which enabled Americans to make 9.8 billion long-distance calls. By 2008, technology advances allowed to prune the employees to 156,000 and still ring up 106 billion calls. The per-capita output of the operator had improved from 64 calls a day to 1861.

Book Details. 784 pages. 2-1/8 x 6-1/8 x 9-1/4 inches. Harvard University Press. Foreword by Emmanuel Macron. Economics & Business. A stellar cast of economists examines the roles of creative destruction in addressing today's most important political and social questions.Inequality is rising, growth is stagnant while rents accumulate, the ...

The idea for a collection of essays about creative destruction grew out of a panel at the Spring meeting of AES, ALLA, and ABA under the title 'Ethnographic Futures', held at Washington University in St. Louis, March 14-16, 2019. The panel, entitled 'Crumbling Materials, Uneven Geographies: Destruction of Capitalism', was organized by ...

Komlos John, 2016. "Has Creative Destruction become more Destructive?," The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, De Gruyter, vol. 16 (4), pages 1-12, October. citation courtesy of. Founded in 1920, the NBER is a private, non-profit, non-partisan organization dedicated to conducting economic research and to disseminating research findings ...

Cite this chapter. Levine, D. (2013). Creative Destruction. In: Pathology of the Capitalist Spirit: An Essay on Greed, Hope, and Loss.

In 2007-09, VC funding in America fell by almost 30%. Yet this column would not be named after Joseph Schumpeter, the father of creative destruction, if it did not believe that following a slump ...

As with all economic concepts, creative destruction presents both positive and negative consequences into society. The benefits far outweigh the costs, and the process ultimately creates wealth and better standards of living. People fear change and uncertainty, both of which creative destruction can introduce into the market.

Abstract of the Dissertation. Three Essays on Creative Destruction. by. Mitsuru Igami. Doctor of Philosophy in Management University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Edward Leamer, Chair This dissertation aims to advance our knowledge of long-run economic changes. It consists of three essays on strategic industry dynamics in retail ...

This often leads to a complementary process of creative destruction whereby local structures protect and channel the diffusion of successful innovations, rendering alternatives obsolete. We find that social scientists naturally focus far more on how social and cultural contexts influence material innovations than the converse. We highlight ...

Creative destruction, in this case, had a negative impact on me as I lost my source of income that paid my bills. Because I had no other job, I had a difficult time trying to pay my bills. My employer, on the other hand, benefitted from the development of the washing machines as they could use the machine at their disposal.

The Pros And Cons Of Creative Destruction. Joseph Schumpeter was one of the most famous author and economist in the 20th century. Among his numerous findings, one stands out; creative destruction. Creation refers to - disruptive - innovation on one side, while destruction alludes to the disappearance of some jobs, industries or even sectors on ...

Three Essays on Creative Destruction. This dissertation aims to advance our knowledge of long-run economic changes. It consists of three essays on strategic industry dynamics in retail services, agricultural commodities, and high-tech manufacturing, respectively. Although creative destruction is commonly understood as the replacement of old ...

The vandalism of works of art is of course nothing new. Hitler himself was a fan of destroying art he considered "unGerman" or "degenerate". But whether you love or loathe the phrase ...

The exhibition's curator Jean-Louis Cohen explains that Le Corbusier saw Moscow as "somewhere he could experiment.". Indeed, when the architect was commissioned to construct the famous ...

One of the showpieces of the new Moscow was to be the Moscow Metro [politen] which broke ground in March 1932 and went into service on May 14, 1935. A second project begun in the early 1930s was the Moscow-Volga Canal, built by an army of prison laborers numbering 200,000 and opened in July 1937. Yet another project, for a monumental Palace of ...

This essay has sought to describe the review, development and refinement process the author followed in reprising the landscape and ecological planning called for in Design with Nature augmented by the investigation and development of techniques to retain and update the essential attributes of McHarg's methods with the efficiencies of design ...

The History of Moscow City. Moscow is the capital and largest city of Russia as well as the. It is also the 4th largest city in the world, and is the first in size among all European cities. Moscow was founded in 1147 by Yuri Dolgoruki, a prince of the region. The town lay on important land and water trade routes, and it grew and prospered.