Law Explorer

Fastest law search engine.

If you have any question you can ask below or enter what you are looking for!

- Law Explorer /

- CONSTITUTIONAL LAW /

Resulting Trusts

7 Resulting trusts

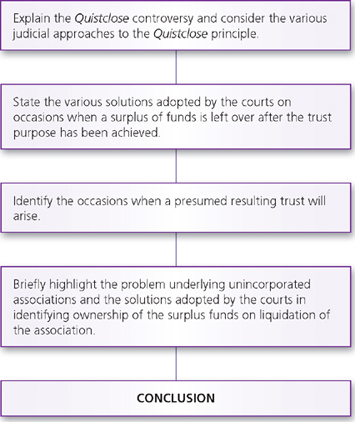

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES By the end of this chapter you should be able to: ■ classify resulting trusts ■ understand the Quistclose controversy ■ recognise an unincorporated association ■ comprehend the basis of distributing funds on the liquidation of unincorporated associations ■ understand the rationale behind presumed resulting trusts 7.1 Introduction So far, we have been considering various aspects of express trusts. These trusts, it may be recalled, are created in accordance with the express intention of the settlor. This intention is required to be clearly expressed to the satisfaction of the court. All the circumstances are considered by the courts including verbal and written statements as well as the conduct of the settlor. The effect is that the material terms of an express trust are complete. There are no shortcomings by the draftsperson. A resulting trust, on the other hand, is implied by the court in favour of the settlor/transferor or his estate, if he is dead. Such trusts arise by virtue of the unexpressed or implied intention of the settlor or testator. The settlor or his estate becomes the beneficial owner under the resulting trust when no other suitable claimants can be found. It is as though the settlor has retained a residual interest in the property, albeit one that is implied or created by the courts. The trust is created as a result of defective drafting. The draftsperson omitted to deal with an event that has taken place, and the court is asked to deal with the beneficial ownership of the property. The expression ‘resulting trust’ derives from the Latin verb resultare , meaning to spring back (in effect, to the original owner). Examples are the transfer of property subject to a condition precedent which cannot be achieved, the intended creation of an express trust which becomes void, or the incomplete disposal of the equitable interest in property. In Vandervell v IRC [1967] 2 AC 291 (see Chapter 5 ) the House of Lords decided that the equitable interest in the option to purchase shares was vested in Mr Vandervell by way of a resulting trust. JUDGMENT ‘If A intends to give away all his beneficial interest in a piece of property and thinks he has done so but, by some mistake or accident or failure to comply with the requirements of the law, he has failed to do so, either wholly or partially, there will, by operation of law, be a resulting trust for him of the beneficial interest of which he had failed effectually to dispose. If the beneficial interest was in A and he fails to give it away effectively to another or others or on charitable trusts it must remain in him. Early references to equity, like nature, abhorring a vacuum, are delightful but unnecessary.’ Lord Upjohn 7.2 Automatic and presumed resulting trusts In Re Vandervell’s Trusts (No 2) [1974] 1 All ER 47, Megarry J classified resulting trusts into two categories, namely ‘automatic’ and ‘presumed’ (see below). ‘Automatic’ resulting trusts arise where the beneficial interest in respect of the transfer of property remains undisposed of. Such trusts are created in order to fill a gap in ownership. The equitable maxim that is applicable here is ‘equity abhors a beneficial vacuum’. The equitable or beneficial interest cannot exist in the air and ought to remain with the settlor/transferor. The resulting trust here does not depend on any intentions or presumptions, but is the automatic consequence of the transferor’s failure to dispose of property that was vested in him. In other words, if the transfer is made subject to an intended express trust that fails, the resulting trust that arises does not establish the trust but merely carries back the beneficial interest to the transferor. In Vandervell v Inland Revenue Commissioners (1967) (see Chapter 5 ), a settlor transferred the legal title to property (an option to purchase shares in a company) to Vandervell Trustees Ltd, but failed to identify the beneficial owner. The House of Lords decided that the beneficial interest resulted back to the settlor by way of an automatic resulting trust. JUDGMENT The beneficial interest must belong to or be held for somebody; so if it was not to belong to the donee or be held in trust by him for somebody, it must remain with the donor.’ Lord Reid in Vandervell v Inland Revenue Commissioners The conclusion, on the facts found, is simply that the option was vested in the trustee company as a trustee on trusts, not defined at the time, possibly to be defined later. But the equitable, or beneficial interest, cannot remain in the air: the consequence in law must be that it remains in the settlor … he (Mr Vandervell) had, as a direct result of the option and of the failure to place the beneficial interest in it securely away from him, not divested himself absolutely of the shares which it controlled.’ Lord Wilberforce in Vandervell v Inland Revenue Commissioners The ‘presumed’ resulting trust arises, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, when property is purchased in the name of another, or property is voluntarily transferred to another. For instance, A purchases property and the legal title is conveyed in the name of B, or A transfers the legal title to property in the name of B. In these circumstances B prima facie holds the property on resulting trust for A. This is a rebuttable presumption of law that arises in favour of A. The question is not one of the automatic consequences of a dispositive failure by A in respect of the equitable interest, but one of presumption: the legal title to the property has been transferred to B, and because of the absence of consideration and any presumption of advancement, B is presumed not only to hold the entire interest on trust, but also to hold the beneficial interest for A absolutely. The presumption thus establishes both that B is to take on trust and also the nature of that trust. Megarry J in Re Vandervell Trusts (No 2) (1974) classified resulting trusts in the following manner: JUDGMENT ‘Where A effectually transfers to B (or creates in his favour) any interest in any property, whether legal or equitable, a resulting trust for A may arise in two distinct classes of case For simplicity, I shall confine my statement to cases in which the transfer or creation is made without B providing any valuable consideration, and where no presumption of advancement can arise; and I shall state the position for transfers without specific mention of new interests: (a) the first class of case is where the transfer to B is not made on any trust. If, of course, it appears from the transfer that B is intended to hold on certain trusts, that will be decisive, and the case is not within this category; and similarly if it appears that B is intended to take beneficially. But in other cases there is a rebuttable presumption that B holds on resulting trust for A. The question is not one of the automatic consequences of a dispositive failure by A, but one of presumption: the property has been carried to B, and from the absence of consideration and any presumption of advancement, B is presumed not only to hold the entire interest on trust, but also to hold the beneficial interest for A absolutely. The presumption thus establishes both that B is to take on trust and also what that trust is. Such resulting trusts may be called presumed resulting trusts; (b) the second class of case is where the transfer to B is made on trusts which leave some or all of the beneficial interest undisposed of. Here B automatically holds on resulting trust for A to the extent that the beneficial interest has not been carried to him or others. The resulting trust here does not depend on any intentions or presumptions, but is the automatic consequence of A’s failure to dispose of what is vested in him. Since ex hypothesi the transfer is on trust, the resulting trust does not establish the trust but merely carries back to A the beneficial interest that has not been disposed of. Such resulting trusts may be called “automatic resulting trusts”.’ Professor Birks advocated a theory that the resulting trust (automatic or presumed) is triggered in order to reverse unjust enrichment. His view is that where the defendant has innocently received property as a result of a mistake, or on a failure of consideration or under a void contract, a resulting trust will arise to prevent the unjust enrichment of the transferee. This view was extended by Professor Chambers who argued that in cases of mistake or failure of consideration, the resulting trust was created in accordance with the intention of the transferor not to pass the beneficial interest to the transferee. In short, the transfer of property to a transferee, subject to a mistake or failure of consideration, will effectively only dispose of the legal title to the transferee. These theories map out a major role for the resulting trust. Sir Peter Millett, writing extra-judicially (‘Restitution and constructive trusts’ (1998) LQR 399), argued that a transfer of property based on a mistake or failure of consideration does not give rise to an immediate resulting trust. The initial transfer of property disposes of both legal and beneficial interests to the transferee in accordance with the intention of the transferor. There is no room for a resulting trust at this stage. Once the mistake or failure of the consideration has been revealed to the transferor, he obtains a ‘mere equity’ to rescind the contract and pursue restitutionary remedies, including a reconveyance of the property. In other words, the transferee obtains a defeasible equitable interest which will be defeated if the contract is rescinded. William Swadling (‘A new role for resulting trusts’ (1996) 16 LS 110) argues that the resulting trust is displaced by evidence of intention which is contrary to the intention to create a trust. If the transferor intended the transferee to have the equitable interest, the existence of a mistake on the part of the transferor does not change things and does not give rise to a resulting trust. The transferor will be able to recover the mistaken payment at common law on a total failure of consideration. In Westdeutsche Landesbank Girozentrale v Islington BC [1996] AC 669, Lord Browne-Wilkinson rejected the notion that the resulting trust is designed to reverse unjust enrichment, and declared that this type of trust gives effect to the common intention of the parties. The trust is imposed on the basis of the conscience of the recipient of the property. In his Lordship’s opinion this trust arises in two sets of circumstances, namely the purchase of property in the name of another and the existence of surplus trust funds after the trust purpose has been fulfilled. His Lordship disagreed with Megarry J’s underlying rationale for the automatic resulting trust laid down in Re Vandervell Trusts (No 2) because of his lack of emphasis on implied intention: JUDGMENT ‘A resulting trust arises in two sets of circumstances: (A) where A makes a voluntary payment to B or pays (wholly or in part) for the purchase of property which is vested either in B alone or in the joint names of A and B, there is a presumption that A did not intend to make a gift to B: the money or property is held on trust for A (if he is the sole provider of the money) or in the case of a joint purchase by A and B in shares proportionate to their contributions. It is important to stress that this is only a presumption, which presumption is easily rebutted either by the counter-presumption of advancement or by direct evidence of A’s intention to make an outright transfer: (B) Where A transfers property to B on express trusts, but the trusts declared do not exhaust the whole beneficial interest: ibid . and Quistclose Investmerits Ltd v Rolls Razor Ltd (In Liquidation) [1970] AC 567. Both types of resulting trust are traditionally regarded as examples of trusts giving effect to the common intention of the parties. A resulting trust is not imposed by law against the intentions of the trustee (as is a constructive trust), but gives effect to his presumed intention. Megarry J in In Re Vanderveil’s Trusts (No 2) [1974] Ch 269 suggests that a resulting trust of type (B) does not depend on intention but operates automatically. I am not convinced that this is right. If the settlor has expressly, or by necessary implication, abandoned any beneficial interest in the trust property, there is in my view no resulting trust: the undisposed-of equitable interest vests in the Crown as bona vacantia: see In Re West Sussex Constabulary’s Widows, Children and Benevolent (1930) Fund Trusts [1971] Ch 1.’ The principle laid down in Carreras Rothmans Ltd v Freeman Matthews Ltd [1984] 3 WLR 1016 is to the effect that where property is transferred to the trustee for a specific purpose, to the extent that the equitable interest in the property remains with the transferor until the specified purpose is carried out, it would be unconscionable for the trustee to deny the existence of a resulting trust. This resulting trust will arise in accordance with the intention of the settlor and the knowledge of the trustee. JUDGMENT ‘Equity fastens on the conscience of the person who receives from another property transferred for a specific purpose only and not therefore for the recipient’s own purposes, so that such person will not be permitted to treat the property as his own or to use it for other than the stated purpose. If the common intention is that property is transferred for a specific purpose and not so as to become the property of the transferee, the transferee cannot keep the property if for any reason that purpose cannot be fulfilled.’ Peter Gibson J The difficulty with this rationale for the creation of a resulting trust is that the boundaries between resulting and constructive trusts become blurred. In Air Jamaica v Charlton [1999] 1 WLR 1399, Lord Millett emphasised the relevance of intention in the context of a resulting trust. But he also added that the resulting trust will arise whether or not the settlor/transferor intended to retain a beneficial interest, as in Vandervell v IRC: JUDGMENT ‘Like a constructive trust, a resulting trust arises by operation of law, though unlike a constructive trust it gives effect to intention. But it arises whether or not the transferor intended to retain a beneficial interest – he almost always does not – since it responds to the absence of any intention on his part to pass a beneficial interest to the recipient. It may arise even where the transferor positively wished to part with the beneficial interest, as in Vandervell v Inland Revenue Commissioners [1967] 2 AC 291. In that case the retention of a beneficial interest by the transferor destroyed the effectiveness of a tax avoidance scheme which the transferor was seeking to implement. The House of Lords affirmed the principle that a resulting trust is not defeated by evidence that the transferor intended to part with the beneficial interest if he has not in fact succeeded in doing so. As Plowman J had said in the same case at first instance [1966] Ch 261, 275: As I see it, a man does not cease to own property simply by saying “I don’t want it.” If he tries to give it away the question must always be, has he succeeded in doing so or not? Lord Upjohn [in the same case] expressly approved this.’ Essentially, a resulting trust arises as a default mechanism that returns the property to the transferor, in accordance with his presumed (or implied) intention, as determined by the courts. Very often the transferor may not have contemplated the possibility of a return of the property, but this may be regarded as immaterial if, in the discretion of the court, the circumstances trigger a return of the property to the transferor. The classification by Megarry J in Re Vandervell Trusts (No 2) (1974) into automatic and presumed resulting trusts, despite criticism, serves the useful purpose of simplifying the categories of resulting trusts and for the purpose of exposition we will rely on it. 7.3 Automatic resulting trusts The rationale behind this type of resulting trust, as indicated above, is that the transfer of property was subject to a condition precedent that has not been achieved or that the destination of the beneficial interest has not been dealt with. This type of resulting trust arises in a variety of situations. CASE EXAMPLE Re Ames [1946] Ch 217 A transfer to trustees was made subject to a marriage settlement that turned out to be void. The court decided that the fund was held on resulting trust for the settlor’s estate on the ground that the money was paid on a consideration that had failed. A similar result was reached in Essery v Cowlard (1884) 26 Ch D 191, where the court decided that the contract to marry had definitely and absolutely been put to an end. In Vandervell v IRC [1967] 2 AC 291, the transfer of the legal title to property was made but the transferor omitted to deal with the destination of the equitable interest in a share option scheme. In Barclays Bank v Quistclose [1970] AC 567, a resulting trust was created with regard to a loan made for a specific purpose which was not carried out. It must be emphasised that in order to implement the law of trust the specific loan to the borrower must be such that the sum does not become the general property of the borrower. The specific purpose of the loan identified by the lender must be sufficient to impress an obligation on the borrower to use the amount solely for the purposes as stated by the lender. CASE EXAMPLE Barclays Bank v Quistclose [1970] AC 567 Quistclose Ltd loaned £209,719 to Rolls Razor Ltd, subject to an express condition that the latter would use the money to pay a dividend to its shareholders. Q Ltd’s cheque for the relevant sum was paid into a separate account opened specifically for this purpose with Barclays Bank Ltd, which knew of the purpose of the loan. Before the dividend was paid, Rolls Ltd went into voluntary liquidation and Barclays Ltd claimed to use the amount to set off against the overdrafts of Rolls Ltd’s other account at the bank. The House of Lords held that the terms of the loan were such as to impress on the money a trust in favour of Quistclose Ltd in the event of the dividend not being paid, and since Barclays had notice of the nature of the loan, it was not entitled to set off the amount against Rolls Ltd’s overdraft. Lord Wilberforce broadened the basis on which the resulting trust arose by deciding that there were two trusts posed by these facts – a primary trust to pay a dividend and a secondary trust that arises if the purpose of the primary trust has not been carried out. JUDGMENT ‘[W]hen the money is advanced, the lender acquires an equitable right to see that it is applied for the primary designated purpose … when the purpose has been carried out (i.e. the debt paid) the lender has his remedy against the borrower in debt: if the primary purpose cannot be carried out, the question arises if a secondary purpose (i.e. repayment to the lender) has been agreed, expressly or by implication: if it has, the remedies of equity may be invoked to give effect to it, if it has not (and the money is intended to fall within the general fund of the debtor’s assets) then there is the appropriate remedy for recovery of the loan. I can appreciate no reason why the flexible interplay of law and equity cannot let these practical arrangements, and other variations if desired: it would be to the discredit of both systems if they could not. In the present case the intention to create a secondary trust for the benefit of the lender, to arise if the primary trust, to pay the dividend, could not be carried out, is clear and I can find no reason why the law should not give effect to it.’ Lord Wilberforce In Twinsectra v Yardley [2002] 2 AC 164, Lord Millett in an obiter pronouncement reiterated that the duty imposed on the borrower or recipient of the funds to use the funds for the stipulated purpose was not merely contractual, but equitable, and therefore affected the interests of third parties: JUDGMENT The duty is not contractual but fiduciary. It may exist despite the absence of any contract at all between the parties… and it binds third parties as in the Quistclose case itself. The duty is fiduciary in character because a person who makes money available on terms that it is to be used for a particular purpose only and not for any other purpose thereby places his trust and confidence in the recipient to ensure that it is properly applied. This is a classic situation in which a fiduciary relationship arises, and since it arises in respect of a specific fund it gives rise to a trust.’ In R v Common Professional Examination Board ex p Mealing-McCleod , the Court of Appeal decided that a Quistclose trust was created where a specific loan from Lloyds Bank was made to the borrower for the purpose of security for costs in respect of litigation and subject thereto, to be held on trust for the lender. The court followed the reasoning of Lord Wilberforce in Quistclose . CASE EXAMPLE R v Common Professional Examination Board ex p Mealing-McCleod, The Times , 2 May 2000 The career of Sally Mealing-McCleod (the applicant), as a student at the Bar, had been dogged by disputes and litigation involving educational institutions and the Common Professional Board (the Board). The first proceedings were against Wolseley Hall and Oxford and Middlesex Universities, in which the Board was joined as a third party. The cause of action was breach of contract. In those proceedings, a number of orders for costs were made against her. The applicant sought judicial review of two decisions of the Board made between 8 April 1997 and 15 July 1997. The effect of these decisions was that the applicant had not qualified for, or was not eligible for, the Bar Vocational Course. The Board declared that it would decline to give the applicant a certificate if she obtained the diploma for which she was studying. Sedley J refused the application. The Court of Appeal granted leave to appeal provided that the applicant gave security for costs in the sum of £6,000. The applicant complied with the order by borrowing £6,000 from Lloyds Bank. The loan agreement with the bank provided in clause 2(c) that: ‘You must use the cash loan for the purpose specified … You will hold that loan, or any part of it, on trust for us until you have used it for this purpose.’ The money was paid into court on 21 December 1998. On 18 February 1999, the appeal was withdrawn because the Board conceded that the applicant was entitled to apply for a place on the Bar Vocational Course. The applicant sought to recover the sum paid into court, on the ground that the money was subject to a trust in favour of the bank. Hidden J refused the application and ordered that the £6,000 and interest should be paid to the Board. The applicant appealed. The court allowed the appeal and ordered that the relevant sum be paid to the bank. The nature of the loan and the surrounding circumstances created a Quistclose trust in respect of the purpose of the loan. The effect was that since the primary purpose of the loan was not carried out, a resulting trust for the lender was created. In the recent case, Wise v Jimenez (2013) the High Court endorsed the Quistclose principle and created a resulting trust for a disappointed investor who transferred funds to the defendant. The court regarded the principle of law as well established but the main issue in this case was one of fact namely, deciding which party’s version of events was to be believed. CASE EXAMPLE Wise v Jimenez and another [2013] Lexis Citation 84 The claimant, Dennis Wise (W), an ex-professional footballer, made a payment of 500,000 to the first defendant, Tony Jimenez (J), a close friend and co-owner of Charlton Football Club. The payment was made in December 2007 through the second defendant, CD Investments Ltd (CDI), a company set up for such a purpose and owned by W and his wife. Following the payment the company was put into liquidation. The payment was made to J as an investment for the purpose of developing a golf course in France, a project which failed to materialise. It was agreed between the parties that W paid the relevant sum to J but it was disputed whether the sum was invested for the stated purpose. J contended that the sum had been invested in the project and consequently he had a complete defence. He argued that land in France was procured for development as a golf course by a company known as Les Bordes Golf International SAS (SAS). J was a director of SAS which owned over 51 per cent of the shares in the company. J claimed that W’s money had been invested in SAS which issued 26 shares in his favour representing his investment. The court preferred W’s explanation of events and held in his favour. In the circumstances the recipient of the sum of money was subject to fiduciary obligations to apply the fund for the stated purpose only. Since the golf course failed to materialise the moneys were held on resulting trust for the claimant. 7.3.1 Quistclose analysis Lord Wilberforce’s reasoning in Quistclose (1970) has attracted a great deal of judicial and academic comment. Millett P, writing extra-judicially (‘The Quistclose trust: who can enforce it?’ (1985) 101 LQR 269), questioned whether a valid ‘primary trust’ had existed in Quistclose (1970). An express trust, subject to limited exceptions, assumes the existence of a person with a locus standi to enforce the trust. Without such a person the intended express trust is void (see later). The intended ‘primary trust’ was to pay a dividend. This lacks a beneficiary to enforce the trust. Thus, it is doubtful whether there could be a valid express trust in order to pay a dividend as Lord Wilberforce decided. In addition such a primary trust may lack precision or certainty which the law requires. In Twinsectra v Yardley [2002] All ER 377 Lord Millett restated his views: JUDGMENT ‘In several of the cases the primary trust was for an abstract purpose with no one but the lender to enforce performance or restrain misapplication of the money … It is simply not possible to hold money on trust to acquire unspecified property from an unspecified vendor at an unspecified time.’ In addition there have been a variety of approaches to the ‘secondary trust’ in favour of the lender, as laid down by Lord Wilberforce in Quistclose (1970). In Carreras Rothmans Ltd v Freeman Matthews Treasure Ltd [1984] 3 WLR 1016, Peter Gibson J decided that this trust will affect the conscience of the borrower where the terms of the agreement had not been carried out. This is consistent with a constructive trust as distinct from a resulting trust. CASE EXAMPLE Carreras Rothmans Ltd v Freeman Matthews Treasure Ltd [1984] 3 WLR 1016 The claimant company (a cigarette manufacturer) engaged the services of the defendant, an advertising agency. The defendant fell into financial difficulty and needed funds to pay its production agencies and advertising media. The claimant made a special agreement with the defendant to pay such of its debts which were directly attributable to the claimant’s involvement with the defendant. A large fund was paid into a special bank account established in the name of the defendant. A few months later the defendant went into liquidation. The creditors called on the claimant to meet the defendant’s debts. The claimant complied with their demands and took assignments from the creditors of their rights against the defendant. The liquidator of the defendant company refused to pay the claimant any sums from the special account. The claimant sought a declaration that the moneys in the special account ought to be repaid to the claimant. The court held that the funds in the account were held on resulting trust for the claimant because the sum had been paid for a specific purpose that had not been achieved. Accordingly, the sum was not part of the defendant’s assets to be distributed among its creditors. The court applied the Quistclose principle, despite differences in the facts of this case and Quistclose . The differences were that in Quistclose the transaction was one of loan with no contractual obligation on the part of the lender to make payment prior to the agreement for the loan. In the present case there was no loan but there was an antecedent debt owed by the claimant. These were considered insignificant. JUDGMENT ‘In my judgment the principle … is that equity fastens on the conscience of the person who receives from another property transferred for a specific purpose only and not therefore for the recipient’s own purposes, so that such person will not be permitted to treat the property as his own or to use it for other than the stated purpose. If the common intention is that property is transferred for a specific purpose and not so as to become the property of the transferee, the transferee cannot keep the property if for any reason that purpose cannot be fulfilled. In my judgment therefore the [claimant] can be equated with the lender in Quistclose as having an enforceable right to compel the carrying out of the primary trust.’ Peter Gibson J A similar conclusion was reached by the Court of Appeal in Re EVTR [1987] BCLC 646. CASE EXAMPLE Re EVTR [1987] BCLC 646 The claimant acquired a windfall sum of money and decided to assist the company that employed him by purchasing new equipment. He paid a sum of money to the company’s solicitors to be released to the company ‘for the sole purpose of buying new equipment’. The new equipment was ordered, but before it was delivered the company went into receivership. The claimant alleged that the sum of money was repayable to him in accordance with trusts law. The court held in the claimant’s favour. The court applied the Quistclose principle and decided the sum was held on resulting trust for the claimant. However, in confusing the terminology as to the type of trust involved, the court also reasoned that a constructive trust was created when the sum was originally received by the defendant. JUDGMENT ‘On Quistclose principles, a resulting trust in favour of the provider of the money arises when money is provided for a particular purpose only, and that purpose fails… It is a long-established principle of equity that, if a person who is a trustee receives money or property because of, or in respect of, trust property, he will hold what he receives as a constructive trustee on the trusts of the original trust property. It follows, in my judgment, that the repayments made to the receivers are subject to the same trusts as the original [sum] in the hands of the company. There is now, of course, no question of the [amount] being applied in the purchase of new equipment for the company, and accordingly, in my judgment, it is now held on a resulting trust for the [claimant].’ Dillon LJ Similarly in Cooper v PRG Powerhouse Ltd [2008] EWHC 498 (Ch), the High Court decided that a payment that is subject to a Quistclose trust makes the payee a fiduciary for the benefit of the payer. The effect is that if the payee becomes bankrupt, the payer is entitled to trace his funds in the hands of the payee and may recover his funds in priority over the creditors of the payee. CASE EXAMPLE Cooper v PRG Powerhouse Ltd [2008] EWHC 498 (Ch) The claimant had been the managing director of the defendant company. He purchased a Mercedes motor car from Godfrey Davis Ltd for £37,239 pursuant to a credit agreement and the defendant company agreed to discharge the instalment payments on his (the claimant’s) behalf as part of the salary which he received. Later the claimant resigned and it was agreed that the claimant might keep the car in return for a lump sum payment of £34,329 to the defendant company. It was expected that the defendant company would pay this amount to Godfrey Davis Ltd in discharge of the credit agreement. The claimant made the payment to the defendant, but before the latter could pay Godfrey Davis Ltd, the defendant company went into administration and the payment failed. The claimant brought proceedings for a declaration that the sums paid were held on trust for him and that he was entitled to a repayment of the funds. The principal issues in the proceedings were: (i) whether a purpose trust had been created in favour of the claimant; and (ii) if so, whether the claimant was entitled to trace his funds in the hands of the defendant company. The court held in favour of the claimant and decided that on the evidence it was clear that the payment by the claimant was impressed with a purpose trust to pay that sum to Godfrey Davis Ltd in reduction of his loan. The effect was that the defendant company became a fiduciary in respect of the sum received. The failure to carry out the purpose meant that the claimant was entitled, in equity, to trace his funds in the hands of the defendant company. The objection to the imposition of a constructive trust in the context of a Quistclose trust is that such a trust is not dependent on the intention of the lender or transferor. The trust is created by the courts in order to promote good conscience or to prevent unjust enrichment. The date on which the trust is created is also significant, for if the constructive trust is imposed at the time when the defendant receives the funds, then the equitable interest of the lender would appear to be created before the defendant performs an unconscionable act. The same argument may be raised with regard to the resulting trust. The point here is that the claimant’s (lender’s) equitable interest does not leave him until the sum is applied for the purpose stipulated by the lender. Accordingly, on receipt of the relevant amount the borrower merely acquires the legal title to the funds to be used for the stipulated purpose. If the sum is not used for such purpose the proprietary interest of the claimant may be asserted by him. In Twinsectra v Yardley [2002] 2 All ER 377, Lord Millett expressed his opinion that a Quistclose trust is a resulting trust for the lender and the underlying basis of the trust is the fiduciary relationship that is created between the lender and borrower: JUDGMENT ‘[T]he Quistclose trust is a simple commercial arrangement akin (as Professor Bridge observes) to a retention of title clause (though with a different object) which enables the borrower to have recourse to the lender’s money for a particular purpose without entrenching on the lender’s property rights more than necessary to enable the purpose to be achieved. The money remains the property of the lender unless and until it is applied in accordance with his directions, and insofar as it is not so applied it must be returned to him. I am disposed, perhaps pre-disposed, to think that this is the only analysis which is consistent both with orthodox trust law and with commercial reality. It is unconscionable for a man to obtain money on terms as to its application and then disregard the terms on which he received it. Such conduct goes beyond a mere breach of contract. The duty is not contractual but fiduciary. It may exist despite the absence of any contract at all between the parties… and it binds third parties as in the Quistclose case itself. The duty is fiduciary in character because a person who makes money available on terms that it is to be used for a particular purpose only and not for any other purpose thereby places his trust and confidence in the recipient to ensure that it is properly applied. This is a classic situation in which a fiduciary relationship arises, and since it arises in respect of a specific fund it gives rise to a trust.’ An alternative analysis is to consider that the resulting trust is created only when the fund is not used for the stipulated purpose. Here it could be argued that the defendant receives both the legal and equitable interests in the fund subject to perhaps a contractual obligation to use the fund for the stipulated purpose. If the fund is used in accordance with the common intention of the parties the defendant acquires both the legal and equitable interests. But if the defendant fails to carry out the stipulated purpose a resulting trust automatically springs up in favour of the claimant. In Templeton Insurance Ltd v Penningtons Solicitors LLP [2006] EWHC 685 (Ch), the High Court endorsed the resulting trust analysis to the effect that a payment subject to a Quistclose trust creates a resulting trust in favour of the payer, but subject to a power vested in the recipient of the fund to use it for the stated purpose. CASE EXAMPLE Templeton Insurance Ltd v Penningtons Solicitors LLP [2006] EWHC 685 The claimant, an insurance company, intended to invest in properties by purchasing and reselling the same at a profit over a short period of time. The intention was that the claimant would lend Mr Johnston the fund to purchase the property. The moneys were paid to Johnston’s solicitors, the defendants, subject to an express solicitor’s undertaking that the defendant would keep the moneys in its client’s account only to be used to acquire the identified property. The claimant was led to believe that the property price was £500,000 whereas in reality the purchase price was £236,000. The greater part of the balance of the fund was paid on disbursements and for other purposes unconnected to the purchase of the property. The claimant brought an action seeking compensation and a proprietary interest in the balance of the funds. The court held that the money was subject to a Quistclose trust and the claimant was entitled to its return. JUDGMENT ‘It is now conceded (which it was not, I believe, last November) that when Templeton paid the money to Penningtons, it was held by Penningtons on trust for Templeton and that the money was beneficially owned by Templeton. That, as it seems to me, is plain from the terms of the undertaking … which expressly says that if completion is delayed, then the money will be placed in a designated client deposit account to earn interest for you, that is to say, for Templeton. Plainly, therefore, at any rate, until completion took place, the money was Templeton’s money beneficially. The debate therefore turns on whether there was power under the terms of the undertaking read as a whole to apply the money deposited in Penningtons’ client account for a purpose other than the purchase of the property referred to in the letter. The terms of the trust were the classic Quistclose type of trust, namely, a resulting trust in favour of Templeton subject to a power on the part of Penningtons to apply the money deposited for the purpose of completing the purchase of 4 Aymer Close, Thorpe. It seems to me to follow that monies which were not paid out of the client account for that purpose were monies paid in breach of trust.’ Lewison J KEY FACTS The Quistclose principle Quistclose trust Lord Wilberforce Primary express trust to pay a dividend and secondary resulting trust if primary trust fails Exp Mealing-McCleod Applying Quistclose Carreras Rothmans Gibson J Common intention – trust imposed on conscience of the recipient of funds (constructive trust?) Re EVTR Dillon LJ Constructive trust for the purpose of the loan and on failure a resulting trust for the lender arises Twinsectra Lord Millett Debtor has fiduciary duties regarding the purpose of the loan and on failure a resulting trust arises Templeton Ins v Penningtons Lewison J Resulting trust for the payer but with a power vested in the payee to use the fund for the stated purpose ACTIVITY Self-test questions To what extent is it possible to formulate a comprehensive theory regarding resulting trusts? Discuss. 7.3.2 Surplus of trust funds Where the trust exhausts only some of the trust property, leaving a surplus of funds after the trust purpose has been satisfied, a resulting trust for the transferor or settlor may arise in respect of the surplus. This principle is based on two assumptions: (a) the trust purpose has been satisfied; and (b) a surplus of funds has been left over. CASE EXAMPLE Re Abbott [1900] 2 Ch 326 An appeal was launched to raise funds for two sisters who were destitute. The purpose of the appeal was to enable the beneficiaries to live in lodgings in Cambridge and to provide for their ‘very moderate wants’. Considerable sums were raised and a surplus was left over after the ladies died. The question in issue involved the destination of this surplus. The court decided that the surplus was held on resulting trust for the subscribers. The court dismissed the assertion that the fund was intended to become the absolute property of the ladies entitling them to demand a transfer to themselves, or if they became bankrupt transferring the funds to their trustee in bankruptcy. On construction of the terms of the appeal and the surrounding circumstances, the intention of the subscribers was to give a wide discretion to the trustees as to whether any, and if so what, part of the fund ought to be applied for the benefit of the ladies. This approach was only consistent with a resulting trust. It is to be noted that a material factor in these types of cases is the intention of the transferor. If the intention is expressed an express trust will be created for the transferor. In the absence of an express intention the court is required to consider whether there is any evidence of an implied intention that the transferor retained an interest in the property. Such evidence will vary with the facts of each case. In Re Abbott (1900) some of the factors that appealed to the court were that virtually all the contributors were identifiable and acquainted with the ladies, the terms of the appeal indicated that the basic needs of the ladies were to be taken care of and the trustees were given a wide discretion as to the means of caring for the ladies. These factors were sufficient to impress on the court that an implied resulting trust ought to be created in favour of the contributors. In Re Gillingham Bus Disaster Fund [1958] Ch 300, the court concluded that a resulting trust is created even though the contributors were anonymous. CASE EXAMPLE Re Gillingham Bus Disaster Fund [1958] Ch 300 A disaster took place on the streets of Gillingham. A bus had careered into a group of marching cadets, killing several persons and maiming several more. An appeal was launched to raise funds by means of collecting boxes to be used for funeral expenses, caring for the disabled and ‘for worthy causes’ in memory of the dead boys (non-charitable purposes). A surplus of funds remained after the bus company admitted liability and paid substantial sums for similar purposes. The court was asked to determine the destination of the surplus. Harman J decided, on construction of the circumstances, that a resulting trust for contributors was created. The donors did not part ‘out and out’ with their contributions, but only for the specific purposes as stated in the appeal. In this respect, it was immaterial that the donors contributed anonymously. Accordingly, the surplus amount was held on resulting trust for the donors. The sum was paid into court to await claimants. Failing claimants, the fund was taken by the Crown on the basis of bona vacantia. The court took the view that the ordinary resulting trust rule ought to be followed despite the fact that the vast majority of the contributors were anonymous. The ruling of the court was to the effect that all the contributors (small and large, anonymous and identifiable) were to be treated as having the same intention. The position was analogous to trustees who could not find their beneficiaries. But the court could easily have come to the opposite conclusion, namely the donors being anonymous, manifested an intention not to have the property returned to them. They would then have parted with their funds ‘out and out’, leaving no room for a resulting trust. The Crown would then have been entitled to the property on the basis of bona vacantia. This case was heavily criticised in Re West Sussex Constabulary Trusts [1971] Ch 1 (see later). No resulting trust – beneficial interest taken by the transferee An alternative construction that may be adopted by the court is to the effect that the transferee may take the property beneficially in accordance with the implied intention of the transferor/settlor. In this event there is no room for a resulting trust. This approach may be adopted where the beneficiary is still capable of enjoying the benefit from the settlement. The issues concerning the implied intention of the transferor and whether the purpose of the transfer is still capable of being achieved remain questions of construction of the circumstances of each case. CASE EXAMPLE Re Andrew’s Trust [1905] 2 Ch 48 The first Bishop of Jerusalem died, leaving several infant children. An appeal was launched to raise funds ‘for or towards’ their education. The children had subsequently completed their formal education with use of some of the funds. The question in issue concerned the destination of the remainder of the funds. The court held that the surplus was taken by the children in equal shares, in accordance with the implied intention of the contributors. There was no resulting trust for the contributors. The court was influenced by the fact that the children were still capable of deriving benefits from the fund, unlike Re Abbott (1900) (where the ladies had died: see above). In addition, the court was willing to construe ‘education’ in a broad sense and did not restrict it to formal education. In any event, the court decided that education in the narrow sense as referring to formal education was merely the motive for the gift, as distinct from the intention underlying the gift. A similar result was reached in Re Osoba [1979] 1 WLR 24. CASE EXAMPLE Re Osoba [1979] 1 WLR 24 A testator bequeathed the residue of his estate, which comprised rents from certain leasehold properties, to his widow ‘for her maintenance and for the training of my daughter up to University grade’. The widow died and the daughter completed her formal education. The testator’s son claimed the remainder of the residue which had not been used for the daughter’s education. The court held that the widow and daughter took as joint tenants. This joint tenancy was not severed. Thus, on the death of the widow the daughter succeeded to the entire fund. The references to maintenance and education in the will were merely declarations of the testator’s motive for the gift. JUDGMENT ‘[T]he testator has given the whole fund; he has not given so much of the fund as the trustee or anyone else should determine, but the whole fund. This must be reconciled with the testator having specified the purpose for which the gift is made. This reconciliation is achieved by treating the reference to the purpose as merely a statement of the testator’s motive in making the gift. Any other interpretation of the gift would frustrate the testator’s expressed intention that the whole subject matter should be applied for the benefit of the beneficiary.’ Buckley LJ An additional factor that had influenced the court was that the transfer was made in a residuary clause in the testator’s will. The significance of this was the fact that any failure of the gift would have resulted in an intestacy which would have frustrated the testator’s intention. KEY FACTS Automatic resulting trusts Transfer of the legal title to trustees subject to an intended trust which is void Re Ames (1946) Transfer of the bare legal title to trustees without disposing of the equitable interest Vandervell v IRC (1967); Hodgson v Marks (1971) Disposal of property to another subject to a specific limitation which has not been achieved Barclays Bank v Quistclose (1971); Carreras Rothmans v Freeman Matthews (1984); Re EVTR (1987) Surplus of trust funds left over after the trust purpose had been achieved Re Abbott (1900); Re Gillingham Bus Disaster Fund (1958); contrast Re Andrew’s Trust (1905); Re Osoba (1979) ACTIVITY Self-test questions Consider the ownership of the equitable interests in the relevant properties, in respect of each of the dispositions made by Alfred of properties which he originally owned absolutely: (a) A transfer of 10,000 shares in British Telecom plc to his wife, Beryl, subject to an option, exercisable by their son, Charles, at any time within the next five years, to repurchase 5,000 of the shares. The shares have been duly registered in Beryl’s name and she pays 50 per cent of the dividends received to Alfred. (b) A transfer of £50,000 to trustees ‘upon trust to distribute all or such part of the income (as they in their absolute discretion shall think fit) for the maintenance and training of my housekeeper’s daughter, Mary, until she graduates from university or reaches the age of 25, whichever happens earlier’, subject to gifts over. Mary, aged 24, has recently graduated from the Utopia University. 7.3.3 Dissolution of unincorporated associations An unincorporated association comprises a group of individuals joined together to promote a common purpose or purposes, not being commercial activities and creating mutual rights and duties among its members. Many sports clubs are run as unincorporated associations. Such associations vary in size and objectives; some may be long standing or exist with a view to making profits and have open or restricted membership. They differ from incorporated associations in that they lack a legal personality – separate and distinct from those of its members. The title of the association is treated as a label to identify its members. The association may sue or be sued through its officers who act on behalf of the members collectively. The association is regulated by its rules, which have the effect of imposing an implied contract between all the members inter se . Thus, all the members are collectively joined together by the rules of the association. Its affairs are normally handled by a committee and its assets may be held on trust for the members of the association in order to ensure that the association’s property is kept separate from that of its members. In the leading case of Conservative and Unionist Central Office v Burrell [1982] 1 WLR 522, Lawton LJ defined an ‘unincorporated association’: JUDGMENT ‘[T]wo or more persons bound together for one or more common purposes, not being business purposes, by mutual undertakings, each having mutual duties and obligations, in an organisation which has rules which identify in whom control of it and its funds rests and upon what terms and which can be joined or left at will. The bond of union between the members of an unincorporated association has to be contractual.’ The issue in this case involved the legal status of the Conservative Party and whether it was liable to corporation tax on its profits. The court decided that the party was not an unincorporated association but an amorphous combination of various elements. The party lacked a central organisation which controlled local organisations. In Re Bucks Constabulary Fund (No 2) [1979] 1 WLR 936, Walton J graphically described the structure of an unincorporated association: JUDGMENT ‘If a number of persons associate together, for whatever purpose, if that purpose is one which involves the acquisition of cash or property of any magnitude, then, for practical purposes, some one or more persons have to act in the capacity of treasurers or holders of the property. In any sophisticated association there will accordingly be one or more trustees in whom the property which is acquired by the association will be vested. These trustees will of course not hold such property on their own behalf. Usually there will be a committee of some description which will run the affairs of the association; though, of course, in a small association the committee may well comprise all the members; and the normal course of events will be that the trustee, if there is a formal trustee, will declare that he holds the property of the association in his hands on trust to deal with it as directed by the committee. If the trust deed is a shade more sophisticated it may add that the trustee holds the assets on trust for the members in accordance with the rules of the association. Now in all such cases it appears to me quite clear that, unless under the rules governing the association the property thereof has been wholly devoted to charity, or unless and to the extent to which the other trusts have validly been declared of such property, the persons, and the only persons, interested therein are the members. Save by way of a valid declaration of trust in their favour, there is no scope for any other person acquiring any rights in the property of the association, although of course it may well be that third parties may obtain contractual or proprietary rights, such as a mortgage, over those assets as the result of a valid contract with the trustees or members of the committee as representing the association.’ In Hanchett-Stamford v Attorney General [2008] All ER (D) 391 (Feb), the High Court decided the novel principle of ownership of surplus funds of a non-charitable unincorporated association, subject to only one surviving member. The court decided that the sole surviving member of the association was entitled to the assets absolutely and without restriction. CASE EXAMPLE Hanchett-Stamford v Attorney General [2008] All ER (D) 391 The claimant and her husband hadjoined the Performing and Captive Animals Defence League (the League) in the mid-1960s as life members. The League was a non-charitable, unincorporated association whose object was to introduce legislation outlawing circus tricks and animal films depicting cruelty. The claimant’s husband exercised effective control of the assets which continued to accumulate. In the early 1990s a property was purchased and title was registered in the names of the claimant’s husband and Mr Hervey (a member of the League) as trustees for the League. This property was valued at £675,000. The League also owned a portfolio of shares valued at £1.77 million. Both of the registered proprietors have since died. The claimant, who was the sole surviving member of the League, lived in the premises until she moved into a nursing home. The claimant wished to transfer the assets of the League to an active charity supporting animal welfare and identified the Born Free Foundation as an appropriate charity to receive the assets. The Attorney General was named as the defendant. The issues that required consideration by the court were: (a) whether the objects of the League satisfied the tests for charitable status; and (b) if not, to whom did the assets belong? The court (Lewison J) decided that the objects of the League were inconsistent with charitable status because one of its main objects was to change the law. The League was a private unincorporated association and its assets were owned by the members of the association. Subject to any agreements between members of the League to the contrary, deceased members were deprived of all interests in the assets of such associations. The claimant, as sole surviving member of the association, was entitled to its assets without restriction. The court distinguished an obiter pronouncement by Walton J in Re Bucks Constabulary Fund (No 2) [1979] 1 WLR 936, to the effect that the sole surviving member of an unincorporated association cannot say that he is or was the association, and therefore is not entitled solely to its funds. In Walton J’s view the surplus assets of the association, being ownerless, are taken by the Crown on a bona vacantia . In the present case, Lewison J took issue with Walton J’s analysis and questioned whether the Crown ought to be entitled to the assets of a defunct society, as opposed to the last surviving member. The learned judge considered the potential contradiction in Walton J’s reasoning to the effect that ownership of the society’s assets will be vested in its subsisting members, provided that there is a minimum of two members. But if there is one surviving member that member loses all interest in the assets. Lewison J decided that was equivalent to suggesting that the death of the last but one member deprives the last member of his interest: JUDGMENT ‘[W]hat I find difficult to accept is that a member who has a beneficial interest in an asset, albeit subject to contractual restrictions, can have that beneficial interest divested from him on the death of another member. It leads to the conclusion that if there are two members of an association which has assets of, say, 2 million, they can by agreement divide those assets between them and pocket 1 million each, but if one of them dies before they have divided the assets, the whole pot goes to the Crown as bona vacantia.’ Likewise, the principle in Cunnack v Edwards [1896] 2 Ch 679 was distinguished on the ground that, in that case, there were no surviving members of the society, and on the death of the last surviving third party annuitant beneficiary, the surplus assets of the organisation were ownerless and thus taken by the Crown on a bona vacantia . In that case the society was established to raise funds through subscriptions etc. from its members to provide annuities for the widows of its deceased members. There were no surviving members of the association and on the death of the last widow (beneficiary) an unsuccessful claim to the surplus assets of the society was made by her personal representatives. bona vacantia Property without an apparent owner but which is acquired by the Crown.

Is it true to say that resulting trusts have nothing whatsoever to do with intention?

- by Lawprof Team

Learn better and faster with our premium Oxford trust law notes and model answers

Introduction

The orthodoxy, propounded by Megarry J in Re Vandervell (No.2) is that the institution of resulting trust can be understood through a dichotomy of the “presumed” and the “automatic” resulting trust. Notwithstanding controversy then, this essay will untangle the relationship between resulting trusts and intention through this dichotomy.

Moving from method to substance, this essay suggests that where the presumed resulting trust is concerned, resulting trusts have everything to do with the settlor’s intention (or lack thereof). More specifically however, the Cook v Fountain conception of presumed resulting trust is preferred on grounds of authority and argument.

Presumed Resulting Trusts

As Swadling correctly observes, an understanding of the theoretical foundations of presumed resulting trusts must be grounded in an accurate understanding of a presumption. Properly understood, presumptions are part of the law of proof. As Lord Diplock described them in Pettitt v Pettitt , they disclose the “consensus of judicial opinion” as to the most likely inference of fact to be drawn in the absence of evidence to the contrary. The role of presumptions is thus to bridge proof by evidence of a “primary” fact, to proof of a “secondary” fact, without the need to adduce a separate piece of evidence. Herein lies the presumed resulting trust’s relationship with intention – on the various theoretical accounts of resulting trusts that are described shortly, what is being presumed is the intention of the transferor.

Different Species of Intention

Crucially however, this presumed intention must be distinguished from two other species of intention. The first is an inferred intention, which Lord Neuberger has explained in Stack v Dowden as an intention that is objectively deduced to be the subjective actual intention of the parties, in light of their actions and statements – this conclusion of what a party has intended gives rise to an express trust.

Secondly, we must distinguish presumed intention from imputed intention – a device countenanced by Lady Hale and Lord Walker in Jones v Kernott , in situations where a court is unable to deduce what shares were intended, as a last resort, and representing what the intentions of “reasonable and just people” would have been. The distinction here is crucial, as an imputed intention arises by operation of law and cannot be rebutted.

Content of Presumptions

Having accepted that the link between presumed resulting trust and intention lies in the idea that a the former is grounded in a true (evidential) presumption of the transferors intention, the next question is the precise content of this presumption – in other words, what is the precise intention that is presumed? On this issue, there are two principal approaches, supplemented by a third auxiliary suggestion.

(1) The settlor has positively intended to create a trust in their favour – Swadling’s view

(2) The settlor has no intention to benefit anyone else – the Birksian/Chambers view

(3) The settlor had an unexpressed intention for B to hold on trust for A.

The Cook v Fountain View

Stone points out that the resulting trust was historically an express trust, which differed only in that it was proved by presumption. This is most clearly seen in Lord Nottingham’s judgement in Cook v Fountain , where he considered that a presumptive trust was where the court “presumes there was a declaration”, though the plain and direct proof thereof is not extant. Moreover, this view is supplemented by rebuttal cases such as Fowkes v Pascoe – where the judgement of the court speaks of there being no transfer on trust.

Mee however, criticises this view by reference to Re Vandervell (No.2) – as he considers that Megarry J’s reference to a presumption of a resulting trust applying if the intention is not made manifest to mean that the presumption of resulting trust refers to an unexpressed intent. This however, ignores Megarry J’s conclusion later in the judgement, which considers that an unexpressed intention “does nothing” to effect a result. Secondly, Mee further argues that in a purchase money resulting trust, where A provides money to B to transfer property to C, A’s lack of legal ownership precludes the declaration of an express trust. Nevertheless, Wilde has pointed out by reference to secret trusts and covenants to settle that it is indeed possible to validly declare a trust over property not owned by the settlor at the time of declaration.

Alternatively, Chambers argues that the Cook v Fountain view is inconsistent with s.53(1)(b) LPA 1925 (and its s.7 progenitor) as it put an end to the possibility of presuming a declaration of trust in the absence of writing. Two responses are possible. The first is that, by reference to the words “manifested and proved”, s.53(1)(b) is a procedural rather than a substantive rule, which does not speak to the question of substance – that is, what form a declaration of trust must take to be valid. Furthermore, there is no reason why the presumption could not be that a written declaration in conformity with the evidence admissible to discharge that burden, was in fact made.

The Unexpressed Intention View

Reflected in Mee’s thesis, this is the view that the presumption of resulting trust is that the presumption is a “tool for proving the existence of (naked) intention”, as opposed to expressed intention to create a trust. The quotation points out that Mee’s concept of a presumption is confused, as a presumption is itself a form of proof. More importantly, the established case law on certainty of intention (ie Milroy v Lord ) indicates that we are not concerned with unexpressed intention. To accept his thesis, as Swadling points out, would be to fundamentally reshape the established rules, and create an anomaly whereby the application of a rule of procedure (the presumption) would override the substantive law.

The Birksian/Chambers View

The first approach has been alluded to earlier, and are in fact supported by more traditional cases. Motivating the second Birksian approach however, has been the growth of the law of unjust enrichment, and its influence in the evolution of the view that what was being presumed was an absence of an intention to benefit the transferee. As Birks argued, this employment of negative intention could accommodate the integration of “unjust” factors upon which restitutionary plaintiffs habitually relied on – such as mistake, compulsion and inequality.

To support the Birksian view, commentators such as Chambers rely on Chase Manhattan , where the claimant bank mistakenly made the same payment twice to the defendant. Goulding J held that the payment of money under a factual mistake would lead to the transfer retaining an equitable proprietary interest in the property. While the specific trust was unidentified in that case, Chambers has taken Goulding J’s reliance on Viscount Haldane LC’s speech in Sinclair v Brougham to argue that this was in fact a resulting trust, which arose as the claimant was to be presumed not to intend the recipient to hold the property beneficially.

Returning however, to the concept of “presumption” illuminated by Swadling above, it is submitted, in line with Graham and Virgo that this argument is unconvincing – this is because, as was stated by Deane J in Muschinski v Dodds – the use of presumption (in the device of the resulting trust) could not apply where there was an actual intention that was established by the overall evidence. Thus in Chase Manhattan , the fact that the gift was given under a misapprehension must contradict the idea that the transferee was intended to hold on trust for the transferor. There is thus no space for the presumption to operate – were it to operate, any presumption would be rebutted by the fact.

As a matter of authority, Lord Browne-Wilkinson in Westdeutsche clearly favoured the positive intent analysis of the presumed resulting trust, in contradistinction to the Birksian negative intention approach.

Automatic Resulting Trusts

the positive intention view.

In Westdeutsche , Lord Browne-Wilkinson considered that an “automatic” resulting trust was explicable on the same basis as that of the presumed resulting trust – where there is a presumption that the transferor has intended to declare a trust in their own favour. One construction of his Lordships’ suggestion is that this follows the Cook v Fountain view. Similarly, Rickett and Grantham have argued that where there is a necessity for the law to fill the evidential gap by pointing out that the transferor would have intended to retain the beneficial interest – particularly when one considers the modern political economy, where the alternative presumption that the property is to pass to the Crown would be untenable.

Swadling argues that the problem with this understanding is that fundamentally, the incidence of an automatic resulting trust is in circumstances where there is a transfer on trust which fails – the corollary of which means that the court in such a case has accepted, as an evidential matter, that the transferor has not in fact declared a trust in his own favour. This is illustrated by Vandervell v IRC , where the courts insisted on the automatic application of a resulting trust, despite Mr Vandervell explicitly disavowing any beneficial interest, with Lord Wilberforce pointing out that there was no room to invoke a presumption. We will return to his argument shortly in closing, but for now its validity is entertained.

The Unexpressed Intention Approach

An alternative construction of Lord Browne-Wilkinson’s statement is that his reference to “presumed intention” considers that a proof by presumption of unexpressed intention of the transferor to create a trust for himself is constitutive of the automatic resulting trust. This however, is susceptible to the same criticisms outlined in the case of presumed resulting trusts, and the same point above that it appears inconsistent with the facts and indeed the ratio of Vandervell .

The Negative Intention Approach

In the Air Jamaica case, Lord Millett, giving the speech of the Privy Council pointed out that a resulting trust responds to the absence of intention on the part of the transferor to pass a beneficial interest to the recipient. While this “negative intention” analysis may potentially explain the automatic resulting trust, it is susceptible to a normative critique. Specifically, as Swadling argues, if the only desire is to strip out the the transferee’s enrichment, a response by way of personal claim for the value received may be a better solution, given that it does not prioritise the transferor over the creditors of the transferee, in the event of an insolvency.

Retention Theory

In Vandervell , the judgements of Lord Upjohn and Lord Wilberforce suggest a theory of automatic resulting trust unrelated to that of intention – where a failure to effectually dispose of the beneficial interest, even in circumstances where the transferor has intended to give it away will create a resulting trust by operation of law. Nevertheless, Westdeutsche has pointed out that “retention” is a myth, given that the equitable title of the beneficiary is “engrafted onto” the rights held by the trustees, rather than carved out of the settlor’s rights – thus there is nothing to retain at the time of transfer, a proposition confirmed by Lord Mance in Akers v Samba .

Rebutting Swadling’s Conclusion

Following the rejection of all four ways to explain the automatic resulting trust above, Swadling reaches the unpalatable conclusion that “the automatic resulting trust still defies legal analysis” – and insofar is it cannot be understood, it has nothing to do whatsoever with intention. With respect however, it is submitted that Swadling’s conclusion is flawed. There is in fact a way to explain the automatic resulting trust in terms of positive intention, aligning it conceptually with the presumed resulting trust. This derives from Graham and Virgo’s insight that one way to reconcile this analysis with the case is to consider that the presumed positive intention to create a resulting trust was not rebutted on the facts by Mr Vandervell’s desire to set up a tax-efficient structure. Lending strength to this analysis is the idea that it was unlikely that Mr Vandervell envisaged the failure of the trust, and hence little could be said about who should take the property in that eventuality.

On this view, we might distinguish this presumption of “positive intention” in the case of an automatic resulting trust as conditional on the failure of the original trust that sought to be declared, which is once removed from the unconditional positive intention in the case of a presumed resulting trust.

Now out: model 1st class 🏆 examination answers from Oxford

IPSA LOQUITUR

Land Law: Resulting Trusts

Resulting trusts, what are resulting trusts.

A resulting trust is a type of implied trust . It arises in the absence of a valid express trust. When property is held on resulting trust, it is held by the trustee on trust for the person who transferred title to them in the first place.

Types of Resulting Trust

Resulting trusts arise in a variety of situations. These are the most common:

- Automatic Resulting Trusts : these arise where the settlor voluntarily transfers property to another attempting to make an express trust, but the trust failed – Westdeutsche Landesbank Girozentrale v Islington LBC [1996] AC 669.

- Presumed Resulting Trusts : these arise when a person contributes to the purchase price of property – Westdeutsche Landesbank Girozentrale v Islington LBC [1996] AC 669.

- Trusts of Surplus Benefits : these arise where property is transferred on trust but proves excessive to settle the beneficiary’s claims – Re Guinness’s Settlement [1966] 1 WLR 1355.

- ‘Quistclose’ Trusts : these arise in some circumstances when money is transferred for a specific and exclusive purpose, often as a loan – Barclays Bank Ltd v Quistclose Investments Ltd [1970] AC 567.

Automatic Resulting Trusts

Establishing the trust.

An automatic resulting trust happens whenever a person transfers property on trust, but the trust fails: Westdeutsche Landesbank Girozentrale v Islington LBC [1996] AC 669.

Exception: The Doctrine of Acceleration

Some express trusts set up successive interests. For example, a trust might give assets ‘on trust for X during his life time, and Y in remainder’. Y’s interest is essentially postponed by X’s interest. The intention is that X gets the benefit of the property in their lifetime, and once they die it will be held on trust for Y.

These trusts can be vulnerable to failure by offending the certainty or perpetuity rules . If they do fail for this reason, the assets will not necessarily be held on resulting trust for the original settlor. The doctrine of acceleration usually means that the benefit of the property passes to Y instead. However, the doctrine will not apply if:

- Y’s interest is contingent (e.g., ‘on trust for X during his lifetime, remainder to Y provided Y is married);

- There is any reason not to presume that the settlor intended the benefit of the property to be accelerated to Y: Re Flower’s Settlement Trusts [1957] 1 All ER 462.

Presumed Resulting Trusts

Establishing the presumption.

Where a person makes a contribution to the purchase price of property, there is a presumption that the transferee then holds that property on resulting trust for the contributor: Westdeutsche Landesbank Girozentrale v Islington LBC [1996] AC 669. The equitable title is held in proportion to each beneficiary’s contribution.

For example, T buys a house, and the legal title is transferred solely into T’s name. S1 contributed 40% of the purchase price, while S2 contributed 60%. T contributed nothing. There is a presumption that T holds the legal title on resulting trust for S1 (who owns 40% of the equitable title) and S2 (who owns 60% of the equitable title).

Contributions other than to the purchase price will not raise the presumption:

- Indirect contributions, such as to household expenses, will not count: Burns v Burns [1984] Ch 317

- Applying a discount to the purchase price will count: Springette v Defoe [1992] 2 FLR 388; Laskar v Laskar [2008] EWCA Civ 347.

- Contributing a gift given to the contributor by a third party will count: Midland Bank v Cooke [1995] 4 All ER 562.

- There is no consensus on whether contributing to the mortgage after purchase will count – contrast Cowcher v Cowcher [1972] WLR 425, Curley v Parkes [2004] EWCA Civ 1515 and Stack v Dowden [2007] 2 AC 432.

For family homes, the courts prefer to apply constructive trusts . The presumption of resulting trust is unlikely to arise in this context. Where legal title of a family home is transferred into joint names, the presumption of resulting trust does not apply: Stack v Dowden [2007] 2 AC 432.

Rebutting the Presumption

The presumption of resulting trust is rebutted by showing that the contribution was intended as a gift or a loan : Fowkes v Pascoe (1875) LR 10 Ch App 343.

Where the ‘counter-presumption of advancement’ applies, the courts assume that the contribution was intended as a gift unless proven otherwise. The counter-presumption of advancement tends to involve contributions by male family members. It applies to gifts from:

Fathers to children: Re Roberts [1946] Ch 1.

Husbands to wives: Gascoigne v Gascoign e [1918] 1 KB 223. Also, male fiancés to female fiancés: Moate v Moate [1948] 2 All ER 486. But not wives to husbands: Heseltine v Heseltine [1971] 1 WLR 342.

Historical cases declined to apply it between mothers and dependent children: Bennet v Bennet (1879) 10 Ch D 474. However, see now Musson v Bonner [2010] WTLR 1369.

The presumption does not appear to apply between siblings: Noack v Noack [1959] VR 137.

s.199 of the Equality Act 2010 would abolish the counter-presumption of advancement. However, it has yet to be brought into force. The counter-presumption has received considerable criticism in the courts: see Pettit v Pettitt [1970] AC 777.

S.60 of the Law of Property Act 1925

s.60 of the Law of Property Act 1925 states that:

(1) A conveyance of freehold land to any person without words of limitation, or any equivalent expression, shall pass to the grantee the fee simple or other the whole interest which the grantor had power to convey in such land, unless a contrary intention appears in the conveyance.

A literal interpretation of this provision seems to abolish the presumption of resulting trust for land transfers. This has never been settled by the courts, though there is some dicta stating that this is not the provision’s effect: e.g. National Crime Agency v Dong [2017] EWHC 3116; Ali v Dinc [2020] EWHC 3055. There have been some cases involving presumed resulting trusts of land which do not even mention it, such as Prest v Petrodel Resources Ltd [2013] 2 AC 415.

Trusts of Surplus Benefits

Where a person transfers property to satisfy a claim, but the property proves greater than necessary, a resulting trust will arise. The resulting trust attaches to the ‘surplus’ aspect of what was transferred: Re Guinness’s Settlement [1966] 1 WLR 1355.

A common example is where S transfers assets to T on trust for B’s use as long as B lives. If there is still property left when B dies, the remainder of the property will be held by T on a resulting trust for S.

This does not apply to absolute gifts, since there will be no surplus. For example, take a trust ‘for the benefit of T’s children in their university education’: Re Andrew’s Trust [1905] 2 Ch 48.

- If the courts construe this as a gift solely for use in educating the children, anything left once the children have been educated will be held on resulting trust for the original settlor.

- If, by contrast, the courts construe this as an absolute gift for the children which was merely motivated by the desire to educate them, the children are entitled to the full fund. No resulting trust arises.

If there is no one who can be the beneficiary of the resulting trust, absent contrary intention, the assets will be bona vacantia : Re West Sussex Constabulary’s Widows, Children and Benevolent (1930) Fund Trusts [1971] Ch 1. This means they pass to the Crown.

Quistclose Trusts

A Quistclose trust can arise where money is transferred and segregated for a specific, exclusive purpose which subsequently fails. The name arises from Barclays Bank Ltd v Quistclose Investments Ltd [1970] AC 567.

Quistclose Investments made a loan to Rolls Razor. Quistclose knew the company was doing poorly financially, so it specified that the money could only be used to pay a dividend which had been declared in Rolls’ shareholders’ favour. The money was ringfenced in its own account.

Rolls’ became insolvent before the money was used. The courts were asked who was entitled to the money: Rolls’ secured creditors or Quistclose (an unsecured creditor). Normally, secured creditors have priority over unsecured creditors.