My Speech Class

Public Speaking Tips & Speech Topics

Problem-Solution Speech [Topics, Outline, Examples]

Jim Peterson has over 20 years experience on speech writing. He wrote over 300 free speech topic ideas and how-to guides for any kind of public speaking and speech writing assignments at My Speech Class.

In this article:

Problem-Solution Outline

Problem-solution examples, criminal justice, environment, relationships, teen issues.

What to include in your problem-solution speech or essay?

Problem-solution papers employ a nonfiction text structure, and typically contain the following elements:

Introduction: Introduce the problem and explain why the audience should be concerned about it.

Cause/Effect : Inform the audience on what causes the problem. In some cases, you may also need to take time to dispel common misconceptions people have about the real cause.

Can We Write Your Speech?

Get your audience blown away with help from a professional speechwriter. Free proofreading and copy-editing included.

Thesis Statement: The thesis typically lays out the problem and solution in the form of a question and answer. See examples below.

Solution : Explain the solution clearly and in detail, your problem-solving strategy, and reasons why your solution will work. In this section, be sure to answer common objections, such as “there is a better solution,” “your solution is too costly,” and “there are more important problems to solve.”

Call to Action: Summarize the problem and solution, and paint a picture of what will happen if your final solution is adopted. Also, let the reader know what steps they should take to help solve the problem.

These are the most used methods of developing and arranging:

Problem Solution Method Recommended if you have to argue that there is a social and current issue at stake and you have convince the listeners that you have the best solution. Introduce and provide background information to show what is wrong now.

List the best and ideal conditions and situations. Show the options. Analyze the proper criteria. And present your plan to solve the not wanted situation.

Problem Cause Solution Method Use this pattern for developing and identifying the source and its causes.

Analyze the causes and propose elucidations to the causes.

Problem Cause-Effect Method Use this method to outline the effects of the quandary and what causes it all. Prove the connection between financial, political, social causes and their effects.

Comparative Advantage Method Use this organizational public speaking pattern as recommendation in case everyone knows of the impasse and the different fixes and agrees that something has to be done.

Here are some examples of problems you could write about, with a couple of potential solutions for each one:

Marriage Problem: How do we reduce the divorce rate?

Solution 1: Change the laws to make it more difficult for couples to divorce.

Solution 2: Impose a mandatory waiting period on couples before they can get married.

Environmental Problem: What should we do to reduce the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere?

Solution 1: Use renewable energy to fuel your home and vehicles.

Solution 2: Make recycling within local communities mandatory.

Technical Problem: How do we reduce Windows error reporting issues on PCs?

Solution 1: Learn to use dialogue boxes and other command prompt functions to keep your computer system clean.

Solution 2: Disable error reporting by making changes to the registry.

Some of the best problems to write about are those you have personal experience with. Think about your own world; the town you live in, schools you’ve attended, sports you’ve played, places you’ve worked, etc. You may find that you love problem-solution papers if you write them on a topic you identify with. To get your creativity flowing, feel free to browse our comprehensive list of problem-solution essay and paper topics and see if you can find one that interests you.

Problem-Solution Topics for Essays and Papers

- How do we reduce murder rates in the inner cities?

- How do we stop police brutality?

- How do we prevent those who are innocent from receiving the death penalty?

- How do we deal with the problem of gun violence?

- How do we stop people from driving while intoxicated?

- How do we prevent people from texting while driving?

- How do we stop the growing child trafficking problem?

- What is the best way to deal with domestic violence?

- What is the best way to rehabilitate ex-cons?

- How do we deal with the problem of overcrowded prisons?

- How do we reduce binge drinking on college campuses?

- How do we prevent sexual assaults on college campuses?

- How do we make college tuition affordable?

- What can students do to get better grades in college?

- What is the best way for students to effectively balance their classes, studies, work, and social life?

- What is the best way for college students to deal with a problem roommate?

- How can college students overcome the problem of being homesick?

- How can college students manage their finances more effectively?

- What is the best way for college students to decide on a major?

- What should be done about the problem of massive student loan debts?

- How do we solve the global debt crisis?

- How do we keep countries from employing child labor?

- How do we reduce long-term unemployment?

- How do we stop businesses from exploiting consumers?

- How do we reduce inflation and bring down the cost of living?

- How do we reduce the home foreclosure rate?

- What should we do to discourage consumer debt?

- What is the best way to stimulate economic growth?

- How do we lower the prime cost of manufacturing raw materials?

- How can book retailers deal with rising bookseller inventory costs and stay competitive with online sellers?

- How do we prevent kids from cheating on exams?

- How do we reduce the illiteracy rate?

- How do we successfully integrate English as a Second Language (ESL) students into public schools?

- How do we put an end to the problem of bullying in schools?

- How do we effectively teach students life management skills?

- How do we give everyone access to a quality education?

- How do we develop a system to increase pay for good teachers and get rid of bad ones?

- How do we teach kids to problem solve?

- How should schools deal with the problem of disruptive students?

- What can schools do to improve reading comprehension on standardized test scores?

- What is the best way to teach sex education in public schools?

- How do we teach students to recognize a noun clause?

- How do we teach students the difference between average speed and average velocity?

- How do we teach math students to use sign charts?

- How can we make public education more like the Webspiration Classroom?

- How do we stop pollution in major population centers?

- How do we reduce the negative effects of climate change?

- How do we encourage homeowners to lower their room temperature in the winter to reduce energy consumption?

- What is the best way to preserve our precious natural resources?

- How do we reduce our dependence on fossil fuels?

- What is the best way to preserve the endangered wildlife?

- What is the best way to ensure environmental justice?

- How can we reduce the use of plastic?

- How do we make alternative energy affordable?

- How do we develop a sustainable transportation system?

- How can we provide quality health care to all our citizens?

- How do we incentivize people to stop smoking?

- How do we address the growing doctor shortage?

- How do we curb the growing obesity epidemic?

- How do we reduce dependence on prescription drugs?

- How do we reduce consumption of harmful substances like phosphoric acid and acetic acid?

- How can we reduce the number of fatal hospital errors?

- How do we handle the health costs of people living longer?

- How can we encourage people to live healthier lifestyles?

- How do we educate consumers on the risk of laxatives like magnesium hydroxide?

- How do we end political corruption?

- How do we address the problem of election fraud?

- What is the best way to deal with rogue nations that threaten our survival?

- What can our leaders do to bring about world peace?

- How do we encourage students to become more active in the political process?

- What can be done to encourage bipartisanship?

- How can we prevent terrorism?

- How do we protect individual privacy while keeping the country safe?

- How can we encourage better candidates to run for office?

- How do we force politicians to live by the rules they impose on everyone else?

- What is the best way to get out of a bad relationship?

- How do we prevent cyberbullying?

- What is the best solution for depression?

- How do you find out where you stand in a relationship?

- What is the best way to help people who make bad life choices?

- How can we learn to relate to people of different races and cultures?

- How do we discourage humans from using robots as a substitute for relationships?

- What is the best way to deal with a long-distance relationship?

- How do we eliminate stereotypical thinking in relationships?

- How do you successfully navigate the situation of dating a co-worker?

- How do we deal with America’s growing drug problem?

- How do we reduce food waste in restaurants?

- How do we stop race and gender discrimination?

- How do we stop animal cruelty?

- How do we ensure that all citizens earn a livable wage?

- How do we end sexual harassment in the workplace?

- How do we deal with the water scarcity problem?

- How do we effectively control the world’s population?

- How can we put an end to homelessness?

- How do we solve the world hunger crisis?

- How do we address the shortage of parking spaces in downtown areas?

- How can our cities be made more bike- and pedestrian-friendly?

- How do we balance the right of free speech and the right not to be abused?

- How can we encourage people to use public transportation?

- How do we bring neighborhoods closer together?

- How can we eliminate steroid use in sports?

- How do we protect players from serious injuries?

- What is the best way to motivate young athletes?

- What can be done to drive interest in local sports?

- How do players successfully prepare for a big game or match?

- How should the revenue from professional sports be divided between owners and players?

- What can be done to improve local sports venues?

- What can be done to ensure parents and coaches are not pushing kids too hard in sports?

- How can student athletes maintain high academic standards while playing sports?

- What can athletes do to stay in shape during the off-season?

- How do we reduce teen pregnancy?

- How do we deal with the problem of teen suicide?

- How do we keep teens from dropping out of high school?

- How do we train teens to be safer drivers?

- How do we prevent teens from accessing pornography on the Internet?

- What is the best way to help teens with divorced parents?

- How do we discourage teens from playing violent video games?

- How should parents handle their teens’ cell phone and social media use?

- How do we prepare teens to be better workers?

- How do we provide a rational decision-making model for teens?

- How do we keep companies from mining our private data online and selling it for profit?

- How do we prevent artificial intelligence robots from taking over society?

- How do we make high-speed internet accessible in rural areas?

- How do we stop hackers from breaking into our systems and networks?

- How do we make digital payments more secure?

- How do we make self-driving vehicles safer?

- What is the best way to improve the battery life of mobile devices?

- How can we store energy gleaned from solar and wind power?

- What is the best way to deal with information overload?

- How do we stop computer makers from pre-installing Internet Explorer?

Compare and Contrast Speech [Topics and Examples]

Proposal Speech [Tips + 10 Examples]

1 thought on “Problem-Solution Speech [Topics, Outline, Examples]”

This is very greatfull Thank u I can start doing my essay

Leave a Comment

I accept the Privacy Policy

Reach out to us for sponsorship opportunities

Vivamus integer non suscipit taciti mus etiam at primis tempor sagittis euismod libero facilisi.

© 2024 My Speech Class

80+ Problem Solution Speech Topics

A problem/solution speech takes the approach of highlighting an issue with the intent to provide solutions. It is a two-phase approach where first the speaker lays out the problem and explains the importance. Secondly, a variety of solutions are provided to tackle the said issue. The best solutions are those that can be actively applied.

The first problem to tackle is picking a topic. It is a good idea to pick something topical but then again, the world just supplies so many options that it can be overwhelming.

When you are assigned to write a problem-solution essay or research paper, choosing a good topic is the first dilemma you need to work out.

The world is full of issues that need to be resolved. However, it is not sufficient to simply pick a subject because it is topical. Ideally, you should pick a subject that is important to you on some level as well. Speaking about an issue you care about brings out an irreplicable passion that people are sure to respond to. If you’re still confused, we have included a wide variety of topics so that you can pick one that calls out to you.

Let’s get started!

Table of Contents

- Introduction:

- Thesis Statement:

- Cause/Effect:

- Call to Action:

Problem Solution Method

Comparative advantage method, social issues, environment, relationships, wrapping up, problem/solution speech outline.

Before we jump into the topics, it can be handy to understand the speech structure of a problem-solution speech. Understanding how to approach a speech script can have an effect on the topic you pick. Oftentimes, we are confident we can speak about a subject but once we begin the draft, we realize we don’t actually have that much to say.

So take a good look at what elements you need to include in your problem/solution speech:

Introduction:

The introduction is a key part of any speech. This is where you will try to grab the audience’s attention, establish the problem statement, and highlight your key points. It is in your introduction that you will need to explain why the presented issue is an issue. The objective is to convince the audience that the problem at hand is one that requires attention.

If you need help with effective attention-grabbers, you can browse our article on 12 Effective Attention-Grabbers for your speech .

Thesis Statement:

The thesis statement is where you will present the problem you are about to tackle. Typically the problem is laid out in the form of a question. You will also be talking about your stance on the presented problem.

Cause/Effect:

Before you launch into giving solutions after highlighting the problem, you need to explain the gravity of the problem at hand. You can do so by explaining what negative consequences occur due to said problem. The more you personalize the effects, the more likely you are to capture their attention.

Solution:

Once you talk about all the negative impacts of the presented problem, it is time to give the audience the solutions. Explain all the solutions step-by-step and talk about the evidence why the said solution will work. Make sure not to give solutions that are too vague. If there are common misconceptions about the solutions, address them as well. Discuss both pros and cons of the proposed solutions and explain why the pros outweigh the cons.

Call to Action:

The most important part of a problem/solution type speech is the call to action. This is when you encourage the audience to take the necessary steps to solve the problem. You can do so by painting a picture of the expected results of your proposed solutions. Don’t end on a vague note that sounds like “Together, we can.” Instead, give actionable steps, such as “I encourage each and every one of you to go home and separate your recycling trash.”

Problem/Solution Presentation Techniques

There is more than one way to present a problem/solution model. You might want to look into these techniques to switch up your speaking style.

The classic take is best used for taking a stance against a social or current issue. In such a case, you will highlight a known issue and suggest probable solutions for it. You can approach this method by informing the audience about the issue, a brief history, all geared to explain why the topic is a problem in the first place.

Follow that up by describing an ideal condition without the said issue. Once you create a tempting picture, offer up more than one solution that is applicable to the situation. Explain the hurdles and how they can be overcome. Make sure it is clear that you’ve thought about the problem from both sides of the issue.

Comparative advantage models are useful when tackling a problem that seems to be at an impasse. It is when an issue is well known and has multiple fixes with their own group of supporters. Here, you can take a comparative approach to show the pros and cons of all the different solutions. The key difference is that the general consensus is already there about the importance of tackling the problem, but only the correct solution needs to be selected.

Problem-Solution Speech Topics

Here is our extensive list of problem/solution speech topics:

- Adopting dogs is more ethical than getting a new puppy.

- How education can solve generational poverty.

- Tackling anxiety by adopting a pet.

- Ebooks over books to save the environment.

- One-child policy: unethical but effective.

- Donating as a solution to fight global poverty.

- Do your part, go vegan to fight world hunger.

- Keep wikipedia alive for free information with donations.

- Kindness can begin with a compliment.

- What can we do to ensure government sanctions against companies using child labor?

- Sorting out your waste and what it can do for the environment.

- The necessary switch to bicycles to tackle pollution.

- Why encouraging volunteering at an early age can produce better citizens.

- High time to make the switch to solar and wind energy.

- Self-driving cars are the future of road safety.

- Bike lanes and bike laws enhance traffic safety.

- Effective gun sales management can help reduce reckless deaths.

- Normalize selling colored dolls in all shapes and sizes to promote confidence in children.

- How data became the new oil?

- How to stay private in an increasingly social world?

- Why is high-speed internet still not considered a basic need for rural areas?

- Ethical hacking and why is there a draw to it?

- Digital payments and how to guarantee security.

- Change your passwords. Why your data is in danger!

- Self-driving vehicles, should we handover 100% of the control?

- Have lithium batteries on mobile phones already reached their peak?

- How can technology promote the use of renewable energy?

- How to keep up with the overwhelming news cycle?

- How can we destigmatize video game addiction?

- How can we shift education to a virtual platform?

- How to smoothen the transition from home-schooling to college.

- What are some new methods to tackle the rampant cheating on exams?

- How can we reduce the illiteracy rate?

- It’s high time to end bullying in schools.

- How to normalize homesickness as a problem and tackle it?

- Education is not enough, students need life management skills.

- Is accessibility to quality education sufficient currently?

- How can we guarantee sufficient pay for quality teachers?

- How can problem-solving be taught in schools?

- Is detention an effective solution for disruptive students?

- How you can help your suicidal friend.

- Are we doing enough to improve standardized test score results?

- Effective ways to increase attention in class.

- How can we make sex education mandatory in public schools?

- Creative ways to get students to love maths.

- Does looking at the stars stimulate brain activity?

- How can we tackle the growing obesity epidemic?

- How spending time outdoors can boost your mood.

- The Pomodoro Technique and why it works for productivity.

- Can meditation be the answer to growing stress?

- Can we incentivize smokers to give up smoking?

- How to increase responsibility for fatal hospital errors?

- Fitness apps and how it can benefit health.

- How augmented reality glasses can be a gamechanger for people with disabilities.

- How does taking baths reduce stress and anxiety?

- Burnout: the need to go offline.

- Better posture to tackle back pain.

- Does reading out loud help improve critical thinking?

- Child obesity: a preventable evil.

- Encouraging more greens to help children improve their memory.

- How global pollution can be tackled locally.

- Climate change. Why it is too late and what can still be done.

- Does lower room temperature really help reduce energy consumption?

- How to do our part in preserving natural resources?

- Is it time to stop depending on fossil fuels?

- How to preserve wildlife from going extinct?

- Are current environmental laws sufficient to keep it protected?

- Improving public transport to reduce the number of private cars.

- How can we upgrade our transportation to be more sustainable?

- Why hunting should be illegal in any circumstances.

- It is high time to replace plastic. What are our options?

- Is it enough to make alternative energy affordable?

- Signs of a toxic relationship.

- How to pull yourself out of an emotionally abusive relationship.

- Should parents be allowed to control teens’ social media accounts?

- How to manage expectations in a relationship?

- Recognize negative people and take active steps to avoid them.

- How to help domestic violence victims?

- Why it is pointless to try changing someone.

- How to say “no” in a way that they listen?

- How to maintain a work-life balance in today’s world.

- Why couples counseling needs to stop being taboo.

- Is it possible to bridge the gap across different races and cultures?

- How technology is capitalizing on the growing need for human contact.

- Long-distance relationships. Can you make it work?

- Modern-day relationships and how expectations have changed.

A problem/solution speech is a great topic as it falls under the informational category. As such, it is much easier to capture the audience’s attention. In terms of delivery, make sure you sell the problem before handing out the solution. Following the above outline and tips paired with your amazing content, we are sure you will be able to win over any audience with ease. Make sure you do your research well and triple-check your sources. All that is left to do is practice. See you on the stage!

Problem Solution Speech Topics, Outline & Examples

The problem solution speech is a type of informative speech that enumerates various problems and provides possible solutions to those problems.

If you have been asked to give such a speech, your goal should be to explain the problem and provide realistic and achievable suggestions to address it. In most cases, problem solution speeches are given with the hope that the audience will be inspired to do something about the problems that they are facing.

There are many pressing issues in society today that could be considered ripe material for a problem solution speech. For example, racism, sexism, homophobia, ableism, and ageism are all major social problems that need to be addressed.

Of course, you can’t just pick any old problem and start talking about it – you need to make sure that your topic is something that your audience will actually care about and be interested in hearing.

Problem-Solution Speech Outline

The key to delivering an effective problem-solution speech is to develop an outline and a step-by-step plan that will help focus on different parts of your speech.

Here is a basic outline that you can use for your problem-solution speech:

Introduction

Introduce yourself and give a brief overview of the problem that you will be discussing. This is also where you will need to state your thesis – that is, what solution you think is best for the problem.

Make sure that you are concise and to the point – you don’t want to give your audience too much information, as they will likely tune out if you do.

Thesis/Statement of the problem

Explain what the problem is that you will be discussing. This is where you will need to do your research and really dig into the details of the issue so it is interesting and your speech has gravity.

Also, make sure that your problem is something that can actually be solved – there is no point in discussing a problem if there is no possible solution.

Cause/Effect

Discuss the causes of the problem and the effects that it has on different people or groups. This is where you will really start to get into the nitty-gritty of your topic and show your audience that you understand the issue at hand.

Make sure to back up any claims that you make with research or data so that your speech is credible. Use attention getters to hook your audience and keep them interested.

Potential solutions

This is the meat of your problem-solution speech. Discuss different potential solutions to the problem and explain why you think they would be effective.

Again, make sure to back up your claims with research or data so that your audience knows that you have thoughtfully considered the issue and possible solutions. Keep it realistic – don’t propose a solution that is impossible to achieve.

Call to action

You have now armed your audience with the knowledge of the problem and potential solutions – now what? You will need to challenge your audience to actually do something about the issue.

This could be something as simple as signing a petition or donating to a cause, or it could be something more ambitious like starting a new organization or campaign. Whatever you choose, make sure it is achievable and that your audience knows how they can take action.

Use the outline above to tailor the specifics of your speech to fit your particular audience and situation and deliver an effective problem-solution speech.

Problem-Solution Presentation Techniques

Once you have your outline ready, it’s time to start working on your delivery. Here are some tips to keep in mind as you prepare your problem-solution speech:

- Be passionate : This is not the time for a dry, academic approach. You need to be enthusiastic about the issue at hand and really sell your audience on why they should care.

- Be clear : Make sure that your audience understands the problem and potential solutions. Use straightforward language and avoid jargon.

- Be concise : Remember, you only have a limited amount of time to make your case. Get to the point and don’t ramble.

- Use stories : A personal story or anecdote can be a powerful way to connect with your audience and make your speech more relatable.

- Use visuals : Visual aids can be a great way to engage your audience and break up your speech. Just make sure that they are clear and easy to understand.

- Practice, practice, practice : The only way to get comfortable with delivering a problem-solution speech is to practice it as much as you can. So get in front of a mirror, or even better, ask a friend or family member to listen to you and give feedback. The more you practice, the more confident you will be and overcome your fear of public speaking .

Problem-Solution Speech Topics

1. How can we make sure that all animals are treated humanely?

2. What are the most important things to keep in mind when it comes to animal welfare?

3. How can we make sure that all animals have access to proper care and shelter?

4. Why should we care about animal rights?

5. Why is wildlife conservation important?

6. Why animal testing is cruel?

7. Why should the exotic pet trade be stopped?

9. What can we do about the food industry and mass animal killing?

1. How can we make sure that our technology is accessible to everyone?

2. What are the most important things to keep in mind when using social media?

3. How can we make sure that our online information is safe and secure?

4. What should we do about cyberbullying?

6. How can we make sure that our technology is sustainable?

7. What are the most important things to keep in mind when using new technology?

8. How can we make sure that our technology is user-friendly?

9. What should we do about outdated technology?

10. How can we make sure that our technology is accessible to people with disabilities?

11. What are the most important things to keep in mind when using technology in the classroom?

12. How can we make sure that our technology is used for good and not for evil?

13. What should we do about the digital divide?

14. How can we make sure that our technology is used responsibly?

15. What should we do about the growing problem of e-waste?

16. What are the most important things to keep in mind when using technology in the workplace?

17. What should we do about the increasing dependence on technology?

Relationships

1. How can we improve communication in relationships?

2. What are the biggest problems faced by long-distance relationships?

3. How can we make sure that our relationships are built on trust?

4. What causes jealousy in relationships and how can it be overcome?

5. When is it time to end a relationship?

6. How can we deal with infidelity in a relationship?

7. How can we make sure that our relationships are healthy and balanced?

8. What causes arguments in relationships and how can they be resolved?

9. What are the most important things to keep in mind when raising a family?

10. How can single parents make sure that their children are getting the attention they need?

11. What effect does social media have on relationships?

12. How can we make sure that our relationship with our parents is healthy and supportive?

13. What should we do when our friends or family get into a toxic relationship?

14. How can we deal with envy or jealousy within our friendships?

15. How can we deal with a friend or family member who is going through a tough break-up?

16. How can new relationships be started off on the right foot?

17. What are the most important things to keep in mind when moving in with a partner?

18. What should we do when our relationship starts to fizzle out?

19. How can we deal with the death of a loved one?

20. How can therapy help us improve our relationships?

Social Issues

1. How can we make sure that everyone has access to clean water?

2. What are the most important things to keep in mind when it comes to food security?

3. How can we make sure that all children have access to education?

4. What are the most effective ways of helping people who are homeless?

5. How can we make sure that everyone has access to healthcare?

6. What are the most effective ways of combating climate change?

7. How can we make sure that our cities are sustainable?

8. What are the most important things to keep in mind when it comes to transportation?

9. How can we make sure that our economy is fair and just?

10. What are the most important things to keep in mind when it comes to social inequality?

11. How can we make sure that our government is effective and efficient?

12. What are the most important things to keep in mind when it comes to voting?

13. How can we make sure that our media is responsible and ethical?

14. What are the most important things to keep in mind when it comes to privacy?

15. How can we make sure that our technology is used responsibly?

16. What are the most important things to keep in mind when it comes to security?

17. How can we make sure that our world is peaceful?

18. What are the most important things to keep in mind when it comes to human rights?

19. How can we make sure that our world is sustainable?

20. What are the most important things to keep in mind when it comes to the environment?

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

10.2 Using Common Organizing Patterns

Learning objectives.

- Differentiate among the common speech organizational patterns: categorical/topical, comparison/contrast, spatial, chronological, biographical, causal, problem-cause-solution, and psychological.

- Understand how to choose the best organizational pattern, or combination of patterns, for a specific speech.

Twentyfour Students – Organization makes you flow – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Previously in this chapter we discussed how to make your main points flow logically. This section is going to provide you with a number of organization patterns to help you create a logically organized speech. The first organization pattern we’ll discuss is categorical/topical.

Categorical/Topical

By far the most common pattern for organizing a speech is by categories or topics. The categories function as a way to help the speaker organize the message in a consistent fashion. The goal of a categorical/topical speech pattern is to create categories (or chunks) of information that go together to help support your original specific purpose. Let’s look at an example.

In this case, we have a speaker trying to persuade a group of high school juniors to apply to attend Generic University. To persuade this group, the speaker has divided the information into three basic categories: what it’s like to live in the dorms, what classes are like, and what life is like on campus. Almost anyone could take this basic speech and specifically tailor the speech to fit her or his own university or college. The main points in this example could be rearranged and the organizational pattern would still be effective because there is no inherent logic to the sequence of points. Let’s look at a second example.

In this speech, the speaker is talking about how to find others online and date them. Specifically, the speaker starts by explaining what Internet dating is; then the speaker talks about how to make Internet dating better for her or his audience members; and finally, the speaker ends by discussing some negative aspects of Internet dating. Again, notice that the information is chunked into three categories or topics and that the second and third could be reversed and still provide a logical structure for your speech

Comparison/Contrast

Another method for organizing main points is the comparison/contrast speech pattern . While this pattern clearly lends itself easily to two main points, you can also create a third point by giving basic information about what is being compared and what is being contrasted. Let’s look at two examples; the first one will be a two-point example and the second a three-point example.

If you were using the comparison/contrast pattern for persuasive purposes, in the preceding examples, you’d want to make sure that when you show how Drug X and Drug Y differ, you clearly state why Drug X is clearly the better choice for physicians to adopt. In essence, you’d want to make sure that when you compare the two drugs, you show that Drug X has all the benefits of Drug Y, but when you contrast the two drugs, you show how Drug X is superior to Drug Y in some way.

The spatial speech pattern organizes information according to how things fit together in physical space. This pattern is best used when your main points are oriented to different locations that can exist independently. The basic reason to choose this format is to show that the main points have clear locations. We’ll look at two examples here, one involving physical geography and one involving a different spatial order.

If you look at a basic map of the United States, you’ll notice that these groupings of states were created because of their geographic location to one another. In essence, the states create three spatial territories to explain.

Now let’s look at a spatial speech unrelated to geography.

In this example, we still have three basic spatial areas. If you look at a model of the urinary system, the first step is the kidney, which then takes waste through the ureters to the bladder, which then relies on the sphincter muscle to excrete waste through the urethra. All we’ve done in this example is create a spatial speech order for discussing how waste is removed from the human body through the urinary system. It is spatial because the organization pattern is determined by the physical location of each body part in relation to the others discussed.

Chronological

The chronological speech pattern places the main idea in the time order in which items appear—whether backward or forward. Here’s a simple example.

In this example, we’re looking at the writings of Winston Churchill in relation to World War II (before, during, and after). By placing his writings into these three categories, we develop a system for understanding this material based on Churchill’s own life. Note that you could also use reverse chronological order and start with Churchill’s writings after World War II, progressing backward to his earliest writings.

Biographical

As you might guess, the biographical speech pattern is generally used when a speaker wants to describe a person’s life—either a speaker’s own life, the life of someone they know personally, or the life of a famous person. By the nature of this speech organizational pattern, these speeches tend to be informative or entertaining; they are usually not persuasive. Let’s look at an example.

In this example, we see how Brian Warner, through three major periods of his life, ultimately became the musician known as Marilyn Manson.

In this example, these three stages are presented in chronological order, but the biographical pattern does not have to be chronological. For example, it could compare and contrast different periods of the subject’s life, or it could focus topically on the subject’s different accomplishments.

The causal speech pattern is used to explain cause-and-effect relationships. When you use a causal speech pattern, your speech will have two basic main points: cause and effect. In the first main point, typically you will talk about the causes of a phenomenon, and in the second main point you will then show how the causes lead to either a specific effect or a small set of effects. Let’s look at an example.

In this case, the first main point is about the history and prevalence of drinking alcohol among Native Americans (the cause). The second point then examines the effects of Native American alcohol consumption and how it differs from other population groups.

However, a causal organizational pattern can also begin with an effect and then explore one or more causes. In the following example, the effect is the number of arrests for domestic violence.

In this example, the possible causes for the difference might include stricter law enforcement, greater likelihood of neighbors reporting an incident, and police training that emphasizes arrests as opposed to other outcomes. Examining these possible causes may suggest that despite the arrest statistic, the actual number of domestic violence incidents in your city may not be greater than in other cities of similar size.

Problem-Cause-Solution

Another format for organizing distinct main points in a clear manner is the problem-cause-solution speech pattern . In this format you describe a problem, identify what you believe is causing the problem, and then recommend a solution to correct the problem.

In this speech, the speaker wants to persuade people to pass a new curfew for people under eighteen. To help persuade the civic group members, the speaker first shows that vandalism and violence are problems in the community. Once the speaker has shown the problem, the speaker then explains to the audience that the cause of this problem is youth outside after 10:00 p.m. Lastly, the speaker provides the mandatory 10:00 p.m. curfew as a solution to the vandalism and violence problem within the community. The problem-cause-solution format for speeches generally lends itself to persuasive topics because the speaker is asking an audience to believe in and adopt a specific solution.

Psychological

A further way to organize your main ideas within a speech is through a psychological speech pattern in which “a” leads to “b” and “b” leads to “c.” This speech format is designed to follow a logical argument, so this format lends itself to persuasive speeches very easily. Let’s look at an example.

In this speech, the speaker starts by discussing how humor affects the body. If a patient is exposed to humor (a), then the patient’s body actually physiologically responds in ways that help healing (b—e.g., reduces stress, decreases blood pressure, bolsters one’s immune system, etc.). Because of these benefits, nurses should engage in humor use that helps with healing (c).

Selecting an Organizational Pattern

Each of the preceding organizational patterns is potentially useful for organizing the main points of your speech. However, not all organizational patterns work for all speeches. For example, as we mentioned earlier, the biographical pattern is useful when you are telling the story of someone’s life. Some other patterns, particularly comparison/contrast, problem-cause-solution, and psychological, are well suited for persuasive speaking. Your challenge is to choose the best pattern for the particular speech you are giving.

You will want to be aware that it is also possible to combine two or more organizational patterns to meet the goals of a specific speech. For example, you might wish to discuss a problem and then compare/contrast several different possible solutions for the audience. Such a speech would thus be combining elements of the comparison/contrast and problem-cause-solution patterns. When considering which organizational pattern to use, you need to keep in mind your specific purpose as well as your audience and the actual speech material itself to decide which pattern you think will work best.

Key Takeaway

- Speakers can use a variety of different organizational patterns, including categorical/topical, comparison/contrast, spatial, chronological, biographical, causal, problem-cause-solution, and psychological. Ultimately, speakers must really think about which organizational pattern best suits a specific speech topic.

- Imagine that you are giving an informative speech about your favorite book. Which organizational pattern do you think would be most useful? Why? Would your answer be different if your speech goal were persuasive? Why or why not?

- Working on your own or with a partner, develop three main points for a speech designed to persuade college students to attend your university. Work through the preceding organizational patterns and see which ones would be possible choices for your speech. Which organizational pattern seems to be the best choice? Why?

- Use one of the common organizational patterns to create three main points for your next speech.

Stand up, Speak out Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

10 Chapter 10: Persuasive Speaking

Amy Fara Edwards and Marcia Fulkerson, Oxnard College

Victoria Leonard, Lauren Rome, and Tammera Stokes Rice, College of the Canyons

Adapted by Jamie C. Votraw, Professor of Communication Studies, Florida SouthWestern State College

Figure 10.1: Abubaccar Tambadou 1

Introduction

The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) was founded on April 10, 1866. You may be familiar with their television commercials. They start with images of neglected and lonely-looking cats and dogs while the screen text says: “Every hour… an animal is beaten or abused. They suffer… alone and terrified…” Cue the sad song and the request for donations on the screen. This commercial causes audiences to run for the television remote because they can’t bear to see those images! Yet it is a very persuasive commercial and has proven to be very successful for this organization. According to the ASPCA website, they have raised $30 million since 2006, and their membership has grown to over 1.2 million people. The audience’s reaction to this commercial showcases how persuasion works! In this chapter, we will define persuasive speaking and examine the strategies used to create powerful persuasive speeches.

Figure 10.2: Caged Dogs 2

Defining Persuasive Speaking

Persuasion is the process of creating, reinforcing, or changing people’s beliefs or actions. It is not manipulation, however! The speaker’s intention should be clear to the audience in an ethical way and accomplished through the ethical use of methods of persuasion. When speaking to persuade, the speaker works as an advocate. In contrast to informative speaking, persuasive speakers argue in support of a position and work to convince the audience to support or do something.

As you learned in chapter five on audience analysis, you must continue to consider the psychological characteristics of the audience. You will discover in this chapter the attitudes, beliefs, and values of the audience become particularly relevant in the persuasive speechmaking process. A key element of persuasion is the speaker’s intent. You must intend to create, reinforce, and/or change people’s beliefs or actions in an ethical way.

Types of Persuasive Speeches

There are three types of persuasive speech propositions. A proposition , or speech claim , is a statement you want your audience to support. To gain the support of our audience, we use evidence and reasoning to support our claims. Persuasive speech propositions fall into one of three categories, including questions of fact, questions of value, and questions of policy. Determining the type of persuasive propositions your speech deals with will help you determine what forms of argument and reasoning are necessary to effectively advocate for your position.

Questions of Fact

A question of fact determines whether something is true or untrue, does or does not exist, or did or did not happen. Questions of fact are based on research, and you may find research that supports competing sides of an argument! You may even find that you change your mind about a subject when researching. Ultimately, you will take a stance and rely on credible evidence to support your position, ethically.

Today there are many hotly contested propositions of fact: humans have walked on the moon, the Earth is flat, Earth’s climate is changing due to human action, we have encountered sentient alien life forms, life exists on Mars, and so on.

Here is an example of a question of fact:

Recreational marijuana does not lead to hard drug use.

Recreational marijuana does lead to hard drug use.

Questions of Value

A question of value determines whether something is good or bad, moral or immoral, just or unjust, fair or unfair. You will have to take a definitive stance on which side you’re arguing. For this proposition, your opinion alone is not enough; you must have evidence and reasoning. An ethical speaker will acknowledge all sides of the argument, and to better argue their point, the speaker will convince the audience why their position is the “best” position.

Here is an example of a question of value:

Recreational marijuana use is immoral .

Recreational marijuana use is moral .

Questions of Policy

A question of policy advances a specific course of action based on facts and values. You are telling the audience what you believe should be done and/or you are asking your audience to act in a particular way to make a change. Whether it is stated or implied, all policy speeches focus on values. To be the most persuasive and get your audience to act, you must determine their beliefs, which will help you organize and argue your proposition.

Persuasive speeches on questions of policy must address three elements: need, plan, and practicality . First, the speaker must demonstrate there is a need for change (i.e., there is a problem). Next, the speaker offers the audience a plan (i.e., the policy solution) to address the problem. Lastly, the speaker shows the audience that the solution is practical . This requires that the speaker demonstrate how their proposed plan will address the identified problem without creating new problems.

Consider the topic of car accidents. A persuasive speech on a question of policy might focus on reducing the number of car accidents on a Florida highway. First, the speaker could use evidence from their research to demonstrate there is a need for change (e.g., statistics showing a higher-than-average rate of accidents). Then, the speaker would offer their plan to address the problem. Imagine their proposed plan was to permanently shut down all Florida highways. Would this plan solve the problem and reduce the number of accidents on Florida highways? Well, yes. But is it practical? No. Will it create new problems? Yes – side roads will be congested, people will miss work, kids will miss school, emergency response teams will be slowed, and tourism will decrease. The speaker could not offer such a plan and demonstrate that it is practical. Alternatively, maybe the speaker advocates for a speed reduction in a particularly problematic stretch of highway or convinces the audience to support increasing the number of highway patrol cars.

Here is an example of a question of policy:

Recreational marijuana use should be legal in all 50 states.

Recreational marijuana use should not be legal in all 50 states.

Persuasive Speech Organizational Patterns

There are several methods of organizing persuasive speeches. Remember, you must use an organizational pattern to outline your speech (think back to chapter eight). Some professors will specify a specific pattern to use for your assignment. Otherwise, the organizational pattern you select should be based on your speech content. What pattern is most logical based on your main points and the goal of your speech? This section will explain five common formats of persuasive outlines: Problem-Solution, Problem-Cause-Solution, Comparative Advantages, Monroe’s Motivated Sequence, and Claim to Proof.

Problem-Solution Pattern

Sometimes it is necessary to share a problem and a solution with an audience. In cases like these, the problem-solution organizational pattern is an appropriate way to arrange the main points of a speech. It’s important to reflect on what is of interest to you, but also what is critical to engage your audience. This pattern is used intentionally because, for most problems in society, the audience is unaware of their severity. Problems can exist at a local, state, national, or global level.

For example, the nation has recently become much more aware of the problem of human sex trafficking. Although the US has been aware of this global issue for some time, many communities are finally learning this problem is occurring in their own backyards. Colleges and universities have become engaged in the fight. Student clubs and organizations are getting involved and bringing awareness to this problem. Everyday citizens are using social media to warn friends and followers of sex-trafficking tricks to look out for.

Let’s look at how you might organize a problem-solution speech centered on this topic. In the body of this speech, there would be two main points; a problem and a solution. This pattern is used for speeches on questions of policy.

Topic: Human Sex Trafficking

General Purpose: To persuade

Specific Purpose: To persuade the audience to support increased legal penalties for sex traffickers.

Thesis (Central Idea): Human sex trafficking is a global challenge with local implications, but it can be addressed through multi-pronged efforts from governments and non-profits.

Preview of Main Points: First, I will define and explain the extent of the problem of sex trafficking within our community while examining the effects this has on the victims. Then, I will offer possible solutions to take the predators off the streets and allow the victims to reclaim their lives and autonomy.

- The problem of human sex trafficking is best understood by looking at the severity of the problem, the methods by which traffickers kidnap or lure their victims, and its impact on the victim.

- The problem of human sex trafficking can be solved by working with local law enforcement, changing the laws currently in place for prosecuting the traffickers and pimps, and raising funds to help agencies rescue and restore victims.

Problem-Cause-Solution Pattern

To review the problem-solution pattern, recall that the main points do not explain the cause of the problem, and in some cases, the cause is not necessary to explain. For example, in discussing the problem of teenage pregnancy, most audiences will not need to be informed about what causes someone to get pregnant. However, there are topics where discussing the cause is imperative to understanding the solution. The Problem-Cause-Solution organizational pattern adds a main point between the problem and solution by discussing the cause of the problem. In the body of the speech, there will be three main points: the problem, the cause, and finally, the solution. This pattern is also used for speeches dealing with questions of policy. One of the reasons you might consider this pattern is when an audience is not familiar with the cause. For example, if gang activity is on the rise in the community you live in, you might need to explain what causes an individual to join a gang in the first place. By explaining the causes of a problem, an audience might be more likely to accept the solution(s) you’ve proposed. Let’s look at an example of a speech on gangs.

Topic: The Rise of Gangs in Miami-Dade County

Specific Purpose: To persuade the audience to urge their school boards to include gang education in the curriculum.

Thesis (Central Idea): The uptick in gang affiliation and gang violence in Miami-Dade County is problematic, but if we explore the causes of the problem, we can make headway toward solutions.

Preview of Main Points: First, I will explain the growing problem of gang affiliation and violence in Miami-Dade County. Then, I will discuss what causes an individual to join a gang. Finally, I will offer possible solutions to curtail this problem and get gangs off the streets of our community.

- The problem of gang affiliation and violence is growing rapidly, leading to tragic consequences for both gang members and their families.

- The causes of the proliferation of gangs can be best explained by feeling disconnected from others, a need to fit in, and a lack of supervision after school hours.

- The problem of the rise in gangs can be solved, or minimized, by offering after-school programs for youth, education about the consequences of joining a gang, and parent education programs offered at all secondary education levels.

Let’s revisit the human sex trafficking topic from above. Instead of using only a problem-solution pattern, the example that follows adds “cause” to their main points.

Preview of Main Points: First, I will define and explain the extent of the problem of sex trafficking within our community while examining the effects this has on the victims. Second, I will discuss the main causes of the problem. Finally, I will offer possible solutions to take the predators off the streets and allow the victims to reclaim their lives.

- The cause of the problem can be recognized by the monetary value of sex slavery.

- The problem of human sex trafficking can be solved by working with local law enforcement, changing the current laws for prosecuting traffickers, and raising funds to help agencies rescue and restore victims.

Comparative Advantages

Sometimes your speech will showcase a problem, but there are multiple potential solutions for the audience to consider. In cases like these, the comparative advantages organizational pattern is an appropriate way to structure the speech. This pattern is commonly used when there is a problem, but the audience (or the public) cannot agree on the best solution. When your goal is to convince the audience that your solution is the best among the options, this organizational pattern should be used.

Consider the hot topic of student loan debt cancellation. There is a rather large divide among the public about whether or not student loans should be canceled or forgiven by the federal government. Once again, audience factors come into play as attitudes and values on the topic vary greatly across various political ideologies, age demographics, socioeconomic statuses, educational levels, and more.

Let’s look at how you might organize a speech on this topic. In the body of this speech, one main point is the problem, and the other main points will depend on the number of possible solutions.

Topic: Federal Student Loan Debt Cancellation

Specific Purpose: To persuade the audience to support the government cancellation of $10,000 in federal student loan debt.

Thesis (Central Idea): Student loans are the largest financial hurdle faced by multiple generations, and debt cancellation could provide needed relief to struggling individuals and families.

Preview of Main Points: First, I will define and explain the extent of the student loan debt problem in the United States. Then, I will offer possible solutions and convince you that the best solution is a debt cancellation of $10,000.

- Student loan debt is the second greatest source of financial debt in the United States and several solutions have been proposed to address the problem created by unusually high levels of educational debt.

- The first proposed solution is no debt cancellation. This policy solution would not address the problem.

- The second proposed solution is $10,000 of debt cancellation. This is a moderate cancellation that would alleviate some of the financial burden faced by low-income and middle-class citizens without creating vast government setbacks.

- The third proposed solution is full debt cancellation. While this would help many individuals, the financial setback for the nation would be too grave.

- As you can see, there are many options for addressing the student loan debt problem. However, the best solution is the cancellation of $10,000.

Monroe’s Motivated Sequence Format

Alan H. Monroe, a Purdue University professor, used the psychology of persuasion to develop an outline for making speeches that will deliver results and wrote about it in his book Monroe’s Principles of Speech (1951). It is now known as Monroe’s Motivated Sequence . This is a well-used and time-proven method to organize persuasive speeches for maximum impact. It is most often used for speeches dealing with questions of policy. You can use it for various situations to create and arrange the components of any persuasive message. The five steps are explained below and should be followed explicitly and in order to have the greatest impact on the audience.

Step One: Attention

In this step, you must get the attention of the audience. The speaker brings attention to the importance of the topic as well as their own credibility and connection to the topic. This step of the sequence should be completed in your introduction like in other speeches you have delivered in class. Review chapter 9 for some commonly used attention-grabber strategies.

Step Two: Need

In this step, you will establish the need; you must define the problem and build a case for its importance. Later in this chapter, you will find that audiences seek logic in their arguments, so the speaker should address the underlying causes and the external effects of a problem. It is important to make the audience see the severity of the problem, and how it affects them, their families, and/or their community. The harm , or problem that needs changing, can be physical, financial, psychological, legal, emotional, educational, social, or a combination thereof. It must be supported by evidence. Ultimately, in this step, you outline and showcase that there is a true problem that needs the audience’s immediate attention. For example, it is not enough to say “pollution is a problem in Florida,” you must demonstrate it with evidence that showcases that pollution is a problem. For example, agricultural runoff is said to cause dangerous algal blooms on Florida’s beaches. You could show this to your audience with research reports, pictures, expert testimony, etc.

Step Three: Satisfaction

In this step, the need must be “satisfied” with a solution. As the speaker, this is when you present the solution and describe it, but you must also defend that it works and will address the causes and symptoms of the problem. Do you recall “need, plan, and practicality”? This step involves the plan and practicality elements. This is not the section where you provide specific steps for the audience to follow. Rather, this is the section where you describe “the business” of the solution. For example, you might want to change the voting age in the United States. You would not explain how to do it here; you would explain the plan – what the new law would be – and its practicality – how that new law satisfies the problem of people not voting. Satisfy the need!

Step Four: Visualization

In this step, your arguments must look to the future either positively or negatively, or both. If positive, the benefits of enacting or choosing your proposed solution are explained. If negative, the disadvantages of not doing anything to solve the problem are explained. The purpose of visualization is to motivate the audience by revealing future benefits or using possible fear appeals by showing future harms if no changes are enacted. Ultimately, the audience must visualize a world where your solution solves the problem. What does this new world look like? If you can help the audience picture their role in this new world, you should be able to get them to act. Describe a future where they fail to act, and the problem persists or is exacerbated. Or, help them visualize a world where their adherence to the steps you outlined in your speech remediates the problem.

Step Five: Action

In the final step of Monroe’s Motivated Sequence, we tell the audience exactly what needs to be done by them . Not a general “we should lower the voting age” statement, but rather, the exact steps for the people sitting in front of you to take. If you really want to move the audience to action, this step should be a full main point within the body of the speech and should outline exactly what you need them to do. It isn’t enough to say “now, go vote!” You need to tell them where to click, who to write, how much to donate, and how to share the information with others in their orbit. In the action step, the goal is to give specific steps for the audience to take, as soon as possible, to move toward solving the problem. So, while the satisfaction step explains the solution overall, the action section gives concrete ways to begin making the solution happen. The more straightforward and concrete you can make the action step, the better. People are more likely to act if they know how accessible the action can be. For example, if you want your audience to be vaccinated against the hepatitis B virus (HBV), you can give them directions to a clinic where vaccinations are offered and the hours of that location. Do not leave anything to chance. Tell them what to do. If you have effectively convinced them of the need/problem, you will get them to act, which is your overall goal.

Claim-to-Proof Pattern

A claim-to-proof pattern provides the audience with reasons to accept your speech proposition (Mudd & Sillars, 1962). State your claim (your thesis) and then prove your point with reasons (main points). The proposition is presented at the beginning of the speech, and in the preview, tells the audience how many reasons will be provided for the claim. Do not reveal too much information until you get to that point in your speech. We all hear stories on the news about someone killed by a handgun, but it is not every day that it affects us directly, or that we know someone who is affected by it. One student told a story of a cousin who was killed in a drive-by shooting, and he was not even a member of a gang.

Here is how the setup for this speech would look:

Thesis and Policy Claim: Handgun ownership in America continues to be a controversial subject, and I believe that private ownership of handguns should have limitations.

Preview: I will provide three reasons why handgun ownership should be limited.

When presenting the reasons for accepting the claim, it is important to consider the use of primacy-recency . If the audience is against your claim, put your most important argument first. For this example, the audience believes in no background checks for gun ownership. As a result, this is how the main points may be written to try and capture the audience who disagrees with your position. We want to get their attention quickly and hold it throughout the speech. You will also need to support these main points. Here is an example:

- The first reason background checks should be mandatory is that when firearms are too easily accessed by criminals, more gun violence occurs.

- A second reason why background checks should be mandatory is that they would lower firearm trafficking.

Moving forward, the speaker would select one or two other reasons to bring into the speech and support them with evidence. The decision on how many main points to have will depend on how much time you have for this speech, and how much research you can find on the topic. If this is a pattern your instructor allows, speak with them about sample outlines. This pattern can be used for fact, value, or policy speeches.

Methods of Persuasion

The three methods of persuasion were first identified by Aristotle, a Greek philosopher in the time of Ancient Greece. In his teachings and book, Rhetoric, he advised that a speaker could persuade their audience using three different methods: Ethos (persuasion through credibility), Pathos (persuasion through emotion), and Logos (persuasion through logic). In fact, he said these are the three methods of persuasion a speaker must rely on.

Figure 10.3: Aristotle 3

By definition, ethos is the influence of a speaker’s credibility, which includes character, competence, and charisma. Remember in earlier chapters when we learned about credibility? Well, it plays a role here, too. The more credible or believable you are, the stronger your ethos. If you can make an audience see you believe in what you say and have knowledge about what you say, they are more likely to believe you and, therefore, be more persuaded by you. If your arguments are made based on credibility and expertise, then you may be able to change someone’s mind or move them to action. Let’s look at some examples.

If you are considering joining the U.S. Air Force, do you think someone in a military uniform would be more persuasive than someone who was not in uniform? Do you think a firefighter in uniform could get you to make your house more fire-safe than someone who was not in uniform? Their uniform contributes to their ethos. Remember, credibility comes from audience perceptions – how they perceive you as the speaker. You may automatically know they understand fire safety without even opening their mouths to speak. If their arguments are as strong as the uniform, you may have already started putting your fire emergency kit together! Ultimately, we tend to believe in people in powerful positions. We often obey authority figures because that’s what we have been taught to do. In this case, it works to help us persuade an audience.

Advertising campaigns also use ethos well. Think about how many celebrities sell you products. Whose faces do you regularly see? Taylor Swift, Kerry Washington, Kylie Jenner, Jennifer Aniston? Do they pick better cosmetics than the average woman, or are they using their celebrity influence to persuade you to buy? If you walk into a store to purchase makeup and remember which ones are Kylie Jenner’s favorite makeup, are you more likely to purchase it? Pop culture has power, which is why you see so many celebrities selling products on social media. Now, Kylie may not want to join you in class for your speech (sorry!), so you will have to be creative with ethos and incorporate experts through your research and evidence. For example, you need to cite sources if you want people to get a flu shot, using a doctor’s opinion or a nurse’s opinion is critical to get people to make an appointment to get the shot. You might notice that even your doctor shares data from research when discussing your healthcare. Similarly, y ou have to be credible. You need to become an authority on your topic, show them the evidence, and persuade them using your character and charisma.

Finally, ethos also relates to ethics. The audience needs to trust you and your speech needs to be truthful. Most importantly, this means ethical persuasion occurs through ethical methods – you should not trick your audience into agreeing with you. It also means your own personal involvement is important and the topic should be something you are either personally connected to or passionate about. For example, if you ask the audience to adopt a puppy from a rescue, will your ethos be strong if you bought your puppy from a pet store or breeder? How about asking your audience to donate to a charity; have you supported them yourself? Will the audience want to donate if you haven’t ever donated? How will you prove your support? Think about your own role in the speech while you are also thinking about the evidence you provide.

The second appeal you should include in your speech is pathos , an emotional appeal . By definition, pathos appeals evoke strong feelings or emotions like anger, joy, desire, and love. The goal of pathos is to get people to feel something and, therefore, be moved to change their minds or to act. You want your arguments to arouse empathy, sympathy, and/or compassion. So, for persuasive speeches, you can use emotional visual aids or thoughtful stories to get the audience’s attention and hook them in. If you want someone to donate to a local women’s shelter organization to help the women further their education at the local community college, you might share a real story of a woman you met who stayed at the local shelter before earning her degree with the help of the organization. We see a lot of advertisement campaigns rely on this. They show injured military veterans to get you to donate to the Wounded Warriors Project , or they show you injured animals to get you to donate to animal shelters. Are you thinking about how your own topic is emotional yet? We hope so!

In addition, we all know that emotions are complex. So, you can’t just tell a sad story or yell out a bad word to shock them and think they will be persuaded. You must ensure the emotions you engage relate directly to the speech and the audience. Be aware that negative emotions can backfire, so make sure you understand the audience, so you will know what will work best. Don’t just yell at people that they need to brush their teeth for two minutes or show a picture of gross teeth; make them see the benefits of brushing for two minutes by showing beautiful teeth too.

Emotional appeals also need to be ethical and incorporated responsibly. Consider a persuasive speech on distracted driving. If your audience is high school or college students, they may be mature enough to see an emotional video or photo depicting the devastating consequences of distracted driving. If you’re teaching an elementary school class about car safety (e.g., keeping your seatbelt on, not throwing toys, etc.), it would be highly inappropriate to scare them into compliance by showing a devastating video of a car accident. As an ethical public speaker, it is your job to use emotional appeals responsibly.

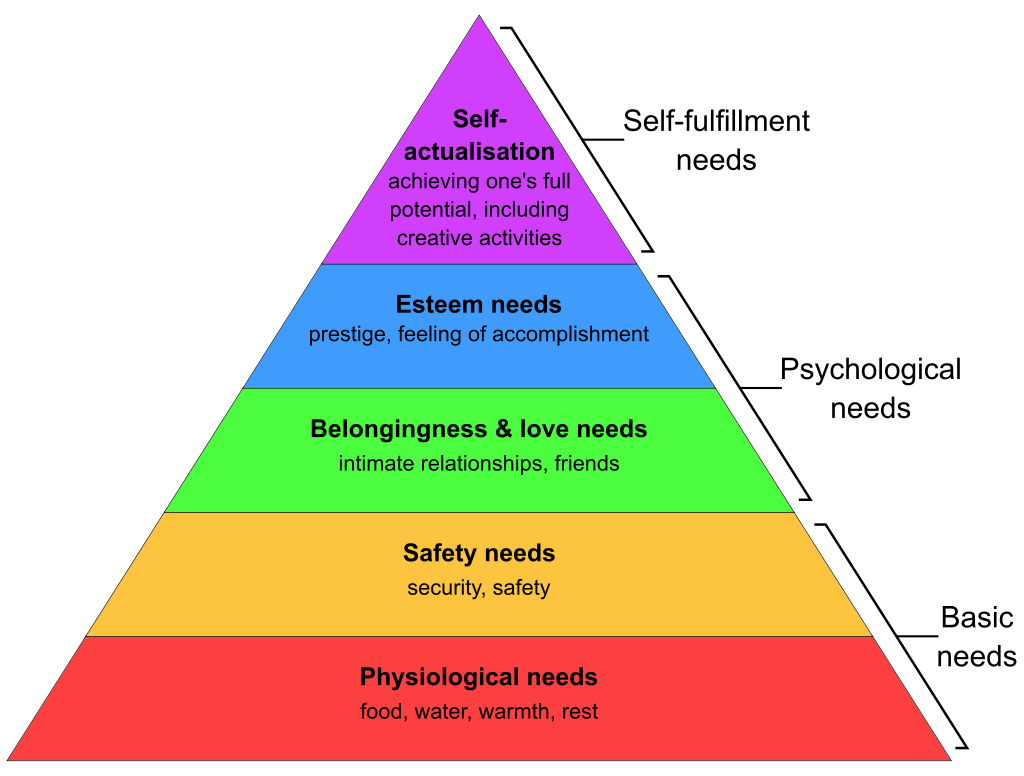

One way to do this is to connect to the theory by Abraham Maslow, Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, which states that our actions are motivated by basic (physiological and safety), psychological (belongingness, love, and esteem), and self-fulfillment needs (self-actualization). To persuade, we have to connect what we say to the audience’s real lives. Here is a visual of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Pyramid:

Figure 10.4: Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs 4

Notice the pyramid is largest at the base because our basic needs are the first that must be met. Ever been so hungry you can’t think of anything except when and what you will eat? (Hangry anyone?) Well, you can’t easily persuade people if they are only thinking about food. It doesn’t mean you need to bring snacks to your speech class on the day of your speech (albeit, this might be relevant to a food demonstration speech). Can you think about other ways pathos connects to this pyramid? How about safety and security needs, the second level on the hierarchy? Maybe your speech is about persuading people to purchase more car insurance. You might argue they need more insurance so they can feel safer on the road. Or maybe your family should put in a camera doorbell to make sure the home is safe. Are you seeing how we can use arguments that connect to emotions and needs simultaneously?

The third level in Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, love and belongingness, is about the need to feel connected to others. This need level is related to the groups of people we spend time with like friends and family. This also relates to the feeling of being “left out” or isolated from others. If we can use arguments that connect us to other humans, emotionally or physically, we will appeal to more of the audience. If your topic is about becoming more involved in the church or temple, you might highlight the social groups one may join if they connect to the church or temple. If your topic is on trying to persuade people to do a walk for charity, you might showcase how doing the event with your friends and family becomes a way of raising money for the charity and carving out time with, or supporting, the people you love. For this need, your pathos will be focused on connection. You want your audience to feel like they belong in order for them to be persuaded. People are more likely to follow through on their commitments if their friends and family do it. We know that if our friends go to the party, we are more likely to go, so we don’t have FOMO (fear of missing out). The same is true for donating money; if your friends have donated to a charity, you might want to be “in” the group, so you would donate also.

Finally, we will end this pathos section with an example that connects Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs to pathos. Maybe your speech is to convince people to remove the Instagram app from their phones, so they are less distracted from their life. You could argue staying away from social media means you won’t be threatened online (safety), you will spend more real-time with your friends (belongingness), and you will devote more time to writing your speech outlines (esteem and achievement). Therefore, you can use Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs as a roadmap for finding key needs that relate to your proposition which helps you incorporate emotional appeals.

The third and final appeal Aristotle described is logos , which, by definition, is the use of logical and organized arguments that stem from credible evidence supporting your proposition. When the arguments in your speech are based on logic, you are utilizing logos. You need experts in your corner to persuade; you need to provide true, raw evidence for someone to be convinced. You can’t just tell them something is good or bad for them, you have to show it through logic. You might like to buy that product, but how much does it cost? When you provide the dollar amount, you provide some logos for someone to decide if they can and want to purchase that product. How much should I donate to that charity? Provide a dollar amount reasonable for the given audience, and you will more likely persuade them. If you asked a room full of students to donate $500.00 to a charity, it isn’t logical. If you asked them to donate $10.00 instead of buying lattes for two days, you might actually persuade them.