- Sign In to save searches and organize your favorite content.

- Not registered? Sign up

Recently viewed (0)

- Save Search

- Subscriptions

- Join E-mail List

Patient Case Studies and Panel Discussion: Lymphoma

- Get Citation Alerts

- Download PDF to Print

A heterogeneous group of diseases, lymphomas encompass a range of diagnoses that call for varied treatment approaches. Although some lymphomas require minimal intervention for cure or remission, others can be very difficult to treat and are associated with poor outcomes. At the NCCN 2019 Annual Congress: Hematologic Malignancies, a panel of experts used 3 case studies to develop an evidence-based approach for the treatment of patients with lymphomas. Moderated by Ranjana H. Advani, MD, the session focused on peripheral T-cell lymphoma, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Lymphomas are a heterogeneous group of diseases with a range of diagnoses that require varied treatment approaches. Although some lymphomas require minimal intervention for cure or remission, others can be difficult to treat and are associated with poor patient outcomes. At the NCCN 2019 Annual Congress: Hematologic Malignancies, a panel of experts identified clinical challenges in managing patients with lymphoma. Moderated by Ranjana H. Advani, MD, Saul A. Rosenberg Professor of Lymphoma, Stanford Cancer Institute, the session focused on 3 case studies, which were used to develop an evidence-based approach for treatment of these patients. Panelists included Jeremy S. Abramson, MD, MMSc, Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center; Mrinal Dutia, MD, The Permanente Medical Group; Richard I. Fisher, MD, Fox Chase Cancer Center; and Andrew D. Zelenetz, MD, PhD, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

- Patient Case Study 1: Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma

In the first case study, a 44-year-old woman presented with a dry, nonproductive cough that she had been experiencing for 2 to 3 months, intermittent bouts of severe shortness of breath, decreased appetite, and a 20-pound weight loss. Chest radiograph revealed mild bilateral pleural effusion and bilateral pulmonary nodules, with the largest nodule measuring 5 cm in the right upper lobe. The patient was admitted for further evaluation, and additional testing was performed (see Figure 1 for results). Bone marrow evaluation revealed no morphologic abnormalities, but complex cytogenetics and the same T-cell clone was found as in the lung biopsy. Therefore, a diagnosis was made of stage IVB peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) with T-follicular helper (TFH) phenotype most consistent with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL).

Patient case study 1: results of further testing.

Abbreviations: NGS, next-generation sequencing; RUL, right upper lobe; SUV, standard uptake value; VATS, video-assisted thoracic surgery.

Citation: Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network J Natl Compr Canc Netw 17, 11.5; 10.6004/jnccn.2019.5028

Dr. Advani explained that this “complicated terminology” comes from recent updates to the WHO classification for PTCL. 1 , 2 Furthermore, she explained that in recent years, advances in molecular biology have helped elucidate the underlying genetic complexity of PTCL and identify mutations and signaling pathways involved in lymphomagenesis. Importantly, many of the same genetic changes observed in AITL are also seen in PTCL not otherwise specified (NOS) that manifest a TFH phenotype. For this designation, the neoplastic cells should express at least 2 or 3 TFH-related antigens, including PD-1, CD10, BCL6, CXCL13, ICOS, SAP, and CCR5.

One potential treatment regimen to use in this patient population is CHOP (cyclophosphamide/doxorubicin/vincristine/prednisone), which is associated with complete response (CR) rates of 50% to 60% in non–anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) and a 5-year overall survival rate of 40% to 60%. According to Dr. Advani, patients with low International Prognostic Index (IPI) scores perform significantly better; however, relapse is associated with poor patient outcomes. “The ongoing challenge is to achieve higher CR rates and to translate those remissions into long-term survival,” said Dr. Advani.

Another treatment option is the CHOEP regimen, which adds etoposide to CHOP. Retrospective studies suggest that outcomes may be better than historical data with CHOP. 3 – 5 In a prospective trial, the Nordic group evaluated the role of autologous stem cell transplantation after patients achieved a CR/partial response with CHOEP. 6 At a median follow-up of 5 years, the 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) rates for AITL were 49% and 52%, respectively, and 38% and 47% for PTCL-NOS, respectively.

Finally, the phase III ECHELON-2 study was the first prospective trial in PTCL to show an OS benefit over CHOP. 7 Frontline therapy for CD30-positive PTCL comparing brentuximab vedotin + cyclophosphamide/doxorubicin/prednisone (BV-CHP) versus CHOP led to a significant improvement in PFS and OS for patients, with a comparable safety profile. The FDA subsequently approved brentuximab vedotin in combination with CHP for adults with previously untreated systematic ALCL or other CD30-expressing PTCL, including AITL and PTCL-NOS. “Based on these data, currently BV-CHP should be the standard regimen for untreated ALCL and other histologies that are CD30-postive,” said Dr. Advani.

In the current case study, the patient received treatment with CHOEP and growth factor support. However, after 2 cycles, PET/CT scan showed no change in lung lesions with a worsening of right-sided pleural effusion (Deauville score 5). Thoracentesis of the pleural effusion was negative for infection but positive for abnormal T-cell population, with morphologic and immunophenotypic findings consistent with the initial diagnosis of PTCL with TFH phenotype most consistent with AITL. The patient was then started on single-agent brentuximab vedotin every 3 weeks. After 4 cycles, PET/CT scan revealed marked improvement in all lesions (Deauville score 4) and was continued on brentuximab vedotin for an additional 4 doses. PET/CT after 8 cycles revealed the resolution of lung nodules and adenopathy in the right axilla with increased metabolic activity (Deauville score 4).

Currently, 4 agents are FDA-approved for use in relapsed/refractory PTCL: pralatrexate, romidepsin, belinostat, and brentuximab vedotin. Aside from brentuximab vedotin use in ALCL, however, overall response rates are low. Brentuximab vedotin has been evaluated in relapsed/refractory AITL, showing an ORR of 54%. 8 Responses did not correlate with level of CD30 expression.

Although no randomized studies have analyzed the role of consolidative hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, data from the prospective COMPLETE study suggested improved outcomes in patients with PTCL AITL and PTCL-NOS. 9 On the other hand, said Dr. Advani, data from the LYSA study do not support the use of autologous stem cell transplant for upfront consolidation in patients with PTCL-NOS, AITL, or ALK-ALCL who have achieved a complete or partial response after induction. 10

“If patients are young and have achieved remission or even a partial response, most of us tend to transplant because outcomes with relapsed disease are very poor,” Dr. Advani concluded. “None of the approved drugs are home runs. The best chance you get is your first chance.”

- Patient Case Study 2: Primary Mediastinal Large B-Cell Lymphoma

In the second case study, a 21-year-old woman presented with severe cough and weight loss. Physical examination showed dilated veins on the anterior chest wall and no palpable peripheral lymphadenopathy. Chest radiograph revealed right-sided pleural effusion and a large mediastinal mass measuring 10.8 cm. Additional testing was performed. PET/CT scan showed a bulky anterior mediastinal mass with SUV max of 24.1 and subcarinal and right hilar adenopathy. However, no evidence of disease was observed below the diaphragm. Bone marrow biopsy was negative. Mediastinoscopy with a biopsy of the mass showed diffuse lymphoid proliferation of intermediate-size atypical cells positive for CD20, CD79A, PAX5, CD30 (dim), MUM1, BCL2, and BCL6, and negative for CD10, BCL1, and EBER. Florescence in situ hybridization was negative for MYC , BCL2 , and BCL6 rearrangements. The final diagnosis of primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (PMBL) was made.

According to Dr. Advani, current treatment choices for PMBL are CHOP + rituximab (R-CHOP) with radiotherapy versus more intensive regimens, such as dose-adjusted etoposide/prednisone/vincristine/cyclophosphamide/doxorubicin + rituximab (DA-EPOCH-R), without radiotherapy. In one study of DA-EPOCH-R with median follow-up of 8.4 years, PFS and OS were both 90%. 11 Another retrospective multicenter analysis that stratified patients by frontline regimen of either DA-EPOCH-R or R-CHOP showed a higher complete response with DA-EPOCH-R (84% vs 70%; P =.046), but the patients in this arm were also more likely to experience treatment-related toxicities. 12 At 2 years, 89% of patients in the R-CHOP arm and 91% of those in DA-EPOCH-R arm were still alive. Despite these similar outcomes, the consensus among panelists was that DA-EPOCH-R was the preferred option.

The patient in the current case report was started on DA-EPOCH-R, with an initial favorable response: interim imaging showed a reduction in size of the anterior mediastinal mass (5 x 6.3 x 9.6 cm) and resolution of left upper pulmonary nodules. The patient continued on DA-EPOCH-R for 4 additional cycles. PET/CT scans 4 weeks posttreatment revealed a metabolically inactive, irregularly shaped anterior mediastinal mass (5.5 x 4 x 5.2 cm) and a focal area of low metabolic activity within the mass (SUV max 3.5; Deauville score 4). She was asymptomatic, and the decision was made to follow with observation. After 2 months, PET/CT scans showed a stable mediastinal mass with increased metabolic activity (SUV max 6). Biopsy of the mediastinal mass was performed and immunohistochemistry results were consistent with relapsed PMBL; immunohistochemistry showed 30% of large cells were CD20- and CD30-positive.

“With PMBL, most of the cures are from initial therapy,” said Dr. Advani. “Salvage rates in recurrent/refractory disease are quite poor.” Overall response rates in PMBL are 25% versus 48% for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), and 2-year overall survival is only 15% versus 24%, respectively. 13

Although CD19 CAR T-cell therapy has been approved, said Dr. Advani, there are very limited data on its use in relapsed/refractory PMBL. According to Jeremy S. Abramson, MD, MMSc, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, and Director of the Lymphoma Center, Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center, the limited available data are indeed encouraging in relapsed/refractory PMBL, and are “looking similar” to those for third-line treatment in DLBCL. Currently 3 randomized clinical trials are evaluating CAR T-cells versus autologous stem cell transplant (the current standard of care) as second-line therapy for relapsed/refractory DLBCL, PMBL, and high-grade B-cell lymphomas, and these trials may ultimately change the standard of care in these patients.

Another treatment option for use in patients with relapsed/refractory PMBL is immune checkpoint inhibitors. Pembrolizumab has shown response rates of 40% to 50% and is now approved by the FDA for use in the third-line and beyond. 14 Furthermore, combination brentuximab vedotin + nivolumab showed even more robust activity, with an overall response rate of 73%. 15

The patient in this case study received 5 cycles of pembrolizumab, and PET/CT scans showed a complete metabolic response.

- Patient Case Study 3: From Follicular Lymphoma to DLBCL

In the last case study, a 48-year-old man presented with enlarged lymph nodes in his left neck and right groin measuring up to 2 cm. He was asymptomatic and had no evidence of B symptoms. Laboratory test results were all normal. Excisional biopsy of the left cervical node showed follicular lymphoma (grade 1–2). PET/CT scan revealed left cervical, axillary, and right external iliac and inguinal adenopathy, with the largest node measuring 1.0 x 2.0 cm (SUV max 5.5). There was no splenomegaly or effusions. Bone marrow biopsy showed normal trilineage hematopoiesis. The diagnosis of stage IIIA follicular lymphoma (grade 1–2) was made, with a Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI) score of 1. Panelists agreed that the best approach for this patient was watchful waiting. Therapy was deferred, and the patient was followed with observation.

Two years later, the patient presented with enlarging lymph nodes in his left neck. He was anxious and had mild fatigue. Results of laboratory tests were normal. PET/CT scan showed increased adenopathy above and below the diaphragm, with the largest node (right external iliac node) measuring 3.4 x 2.8 cm (SUV max 8.4). A biopsy of the right external iliac node was performed, with results showing follicular lymphoma (grade 1–2).

Panelists agreed that observation was an acceptable approach for an asymptomatic patients diagnosed with follicular lymphoma with low-volume disease. However, the patient opted for 4 doses of weekly rituximab. Repeat PET/CT (3 months posttreatment with rituximab) showed that most lymph nodes had resolved. Three years later, the patients presented with a new severe pain in the low back radiating down his right leg. MRI of the L-spine showed a T1 hypointense infiltrative mass replacing the L3 vertebral body. A core biopsy of right psoas mass showed that his follicular lymphoma had transformed to DLBCL, germinal center B-cell–like subtype, with double expressors of MYC >40% and BCL2 >50% and MYC translocation–negative, and expression of Ki67 was 90%. IPI score was 4.

Andrew D. Zelenetz, MD, PhD, Professor of Medicine, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, explained the unique biology of the “double-expressor” phenotype in DLBCL. “This is the one circumstance where DA-EPOCH-R may have a distinct benefit,” he said. “However, in the absence of MYC translocation, it is not clear that overexpression of MYC, which is biologically driven without the translocation, shows a benefit from this intensive regimen.”

The patient received 6 cycles of DA-EPOCH-R with 4 doses of intrathecal methotrexate. Results of interim and end-of-therapy PET scans showed a metabolic complete response (Deauville score 2).

Double-hit and double-expressor lymphomas tend to have inferior outcomes with R-CHOP therapy, Dr. Advani stated. Several retrospective studies and one prospective trial suggest improved outcomes with intensive chemotherapy for double-hit lymphomas. 16 – 18 “Patients with a very high IPI, advanced-stage disease, or extranodal involvement are the ones that I consider good candidates for DA-EPOCH-R,” she said, and also noted that double-expressor DLBCLs have a higher risk of central nervous system (CNS) relapse independent of CNS-IPI.

The patient in the current case study had a CNS-IPI of 3 and an 11% cumulative incidence of CNS relapse at 2 years. Data support some form of CNS prophylaxis, 19 Dr. Advani concluded, but the jury is still out regarding optimal treatment for double-expressor non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Swerdlow SH , Campo E , Pileri SA , et al. . The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms . Blood 2016 ; 127 : 2375 – 2390 .

- Search Google Scholar

- Export Citation

Hildyard C , Shiekh S , Browning J , Collins GP . Toward a biology-driven treatment strategy for peripheral T-cell lymphoma . Clin Med Insights Blood Disord 2017 ; 10 :1179545X17705863.

Cederleuf H , Bjerregard Pedersen M , Jerkeman M . The addition of etoposide to CHOP is associated with improved outcome in ALK+ adult anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a Nordic Lymphoma Group study . Br J Haematol 2017 ; 178 : 739 – 746 .

Schmitz N , Trümper L , Ziepert M , et al. . Treatment and prognosis of mature T-cell and NK-cell lymphoma: an analysis of patients with T-cell lymphoma treated in studies of the German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group . Blood 2010 ; 116 : 3418 – 3425 .

Janikova A , Chloupkova R , Campr V , et al. . First-line therapy for T cell lymphomas: a retrospective population-based analysis of 906 T cell lymphoma patients . Ann Hematol 2019 ; 98 : 1961 – 1972 .

d’Amore F , Relander T , Lauritzsen GF , et al. . Up-front autologous stem-cell transplantation in peripheral T-cell lymphoma: NLG-T-01 . J Clin Oncol 2012 ; 30 : 3093 – 3099 .

Horwitz S , O’Connor OA , Pro B , et al. . Brentuximab vedotin with chemotherapy for CD30-positive peripheral T-cell lymphoma (ECHELON-2): a global, double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial . Lancet 2019 ; 393 : 229 – 240 .

Horwitz SM , Advani RH , Bartlett NL , et al. . Objective responses in relapsed T-cell lymphomas with single-agent brentuximab vedotin . Blood 2014 ; 123 : 3095 – 3100 .

Park SI , Horwitz SM , Foss FM , et al. . The role of autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with nodal peripheral T-cell lymphomas in first complete remission: Report from COMPLETE, a prospective, multicenter cohort study . Cancer 2019 ; 125 : 1507 – 1517 .

Fossard G , Broussais F , Coelho I , et al. . Role of up-front autologous stem-cell transplantation in peripheral T-cell lymphoma for patients in response after induction: an analysis of patients from LYSA centers . Ann Oncol 2018 ; 29 : 715 – 723 .

Melani C , Advani R , Roschewski M , et al. . End-of-treatment and serial PET imaging in primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma following dose-adjusted EPOCH-R: a paradigm shift in clinical decision making . Haematologica 2018 ; 103 : 1337 – 1344 .

Shah NN , Szabo , Huntington SF , et al. . R-CHOP versus dose-adjusted R-EPOCH in frontline management of primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma: a multi-centre analysis . Br J Haematol 2018 ; 180 : 534 – 544 .

Kuruvilla J , Pintilie M , Tsang R , et al. . Salvage chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation are inferior for relapsed or refractory primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma compared with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma . Leuk Lymphoma 2008 ; 49 : 1329 – 1336 .

Zinzani PL , Ribrag V , Moskowitz CH , et al. . Safety and tolerability of pembrolizumab in patients with relapsed/refractory primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma . Blood 2017 ; 130 : 267 – 270 .

Zinzani PL , Santoro A , Gritt G , et al. . Nivolumab combined with brentuximab vedotin for relapsed/refractory primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma: efficacy and safety from the phase II CheckMate 436 study [published online August 9, 2019] . J Clin Oncol . doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01492

Petrich AM , Gandhi M , Jovanovic B , et al. . Impact of induction regimen and stem cell transplantation on outcomes in double-hit lymphoma: a multicenter retrospective analysis . Blood 2014 ; 124 : 2354 – 2361 .

Oki Y , Noorani M , Lin P , et al. . Double hit lymphoma: the MD Anderson Cancer Center clinical experience . Br J Haematol 2014 ; 166 : 891 – 901 .

Dunleavy K , Fanale MA , Abramson JS , et al. . Dose-adjusted EPOCH-R (etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and rituximab) in untreated aggressive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with MYC rearrangement: a prospective, multicentre, single-arm phase 2 study . Lancet Haematol 2018 ; 5 : e609 – 617 .

Savage KJ , Slack GW , Mottok A , et al. . Impact of dual expression of MYC and BCL2 by immunohistochemistry on the risk of CNS relapse in DLBCL . Blood 2016 ; 127 : 2182 – 2188 .

Disclosures: Dr. Advani has disclosed that she has received grant/research support from Agensys, Inc., Celgene Corporation, Forty Seven, Inc., Janssen Pharmaceutica Products, LP, Kura Oncology, Inc., Merck & Co., Inc., Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Genentech, Inc./Roche Laboratories, Inc., Pharmacyclics, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Seattle Genetics, Inc.; received consulting fees from AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, Bayer HealthCare, Gilead Sciences, Inc., Kite Pharma, Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co., Ltd., Cell Medica, Genentech, Inc./Roche Laboratories, Inc., Seattle Genetics, Inc., and Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America, Inc.; and is a scientific advisor for AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, Bayer HealthCare, Gilead Sciences, Inc., Kite Pharma, Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co., Ltd., Cell Medica, Genentech, Inc./Roche Laboratories, Inc., Seattle Genetics, Inc., and Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America, Inc. Dr. Abramson has disclosed that he receives consulting fees from AbbVie, Inc., Bayer HealthCare, Celgene Corporation, EMD Serono, Genentech, Inc., Janssen Pharmaceutica Products, LP, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Kite Pharma, and Roche Laboratories, Inc. Dr. Dutia has disclosed that she has no interests, arrangements, affiliations, or commercial interests with the manufacturers of any products discussed in this article or their competitors. Dr. Fisher has disclosed that he receives consulting fees from Celgene Corporation and PRIME. Dr. Zelenetz has disclosed that he received consulting fees from AbbVie, Inc., Amgen Inc., AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, Celgene Corporation, Gilead Sciences, Inc., Janssen Pharmaceutica Products, LP, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, Adaptive Biotechnologies Corporation, Genentech, Inc./Roche Laboratories, Inc., and Pharmacyclics; is a scientific advisor for AbbVie, Inc., AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, and MorphoSys AG; and receives grant/research support from BeiGene, Gilead Sciences, Inc., MEI Pharma Inc., and Roche Laboratories, Inc.

Article Sections

- View raw image

- Download Powerpoint Slide

Article Information

- Get Permissions

- Similar articles in PubMed

Google Scholar

Related articles.

- Advertising

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Permissions

© 2019-2024 National Comprehensive Cancer Network

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.194.105.172]

- 185.194.105.172

Character limit 500 /500

- Case report

- Open access

- Published: 15 April 2017

Primary adrenal non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a case report and review of the literature

- Nanik Ram 1 ,

- Owais Rashid 1 ,

- Saad Farooq 2 ,

- Imran Ulhaq 1 &

- Najmul Islam 1

Journal of Medical Case Reports volume 11 , Article number: 108 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

4993 Accesses

16 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Lymphomas are cancers that arise from the white blood cells and have been traditionally divided into two large subtypes: Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. B-cell lymphoma is the most common subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma; almost 85% of patients with lymphoma have this variant. Lymphomas can potentially arise from any lymphoid tissue located in the body; however, primary adrenal non-Hodgkin lymphoma is extremely rare. We report the history, examination findings, and laboratory results of a 50-year-old man diagnosed with a primary left adrenal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Case presentation

A 50-year-old Pakistani man presented to our hospital with progressively increasing pain and fullness in the left upper quadrant of his abdomen, generalized weakness, easy fatigability, and decreased appetite of 1.5 months’ duration. On examination, he had a blood pressure of 140/80 mmHg with no postural drop, a pulse rate of 106 beats/minute, and no fever. His past medical history was significant for pulmonary tuberculosis 2 years earlier, for which he received antituberculous therapy. Computed tomography revealed a heterogeneous enhancing soft tissue density mass in the left adrenal gland. It measured 7.1 × 5.6 × 9.5 cm. Further laboratory workup revealed the following levels: sodium 135 mEq/L, potassium 4.5 mEq/L, lactate dehydrogenase 905 IU/L, renin 364 IU/ml, aldosterone 5.79 ng/dl, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate 79.20 μg/dl, urinary vanillylmandelic acid 6.4 mg/24 hours, and a low-dose overnight dexamethasone suppression test result of 3.20 μg/dl. The patient underwent left adrenalectomy. Histopathological test results showed a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Immunohistochemical stains were strongly positive for CD20 and negative for CD3, CD5, CD10, and cyclin D1. The patient’s Ki-67 (Mib-1) index was approximately 80%. He received a total of six cycles of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone chemotherapy (rituximab was not given, owing to financial constraints) and was routinely followed pre- and postchemotherapy at our hematology clinic with complete blood count and serum lactate dehydrogenase evaluations. The patient responded to chemotherapy and is currently doing well.

Conclusions

Primary adrenal lymphoma is an extremely rare but rapidly progressive disease. It generally carries a poor prognosis, partly because an optimal treatment protocol has not yet been established. Further studies with larger sample sizes are needed to establish the best treatment option and increase overall survival.

Peer Review reports

The American Cancer Society estimated that more than 70,000 new cases of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) would be diagnosed in 2016 [ 1 , 2 ]. Although lymphomas arise mainly from lymph nodes, primary extranodal NHL occurs in at least 25% of the cases [ 3 ]. The adrenal gland can be secondarily involved in around 4% of the patients; however, primary adrenal NHL is extremely rare and accounts for less than 1% of all NHL cases [ 4 ]. Primary adrenal lymphoma (PAL) is histologically proven lymphoma of one or both adrenal glands in patients with no prior history of lymphoma. If other organs or lymph nodes besides the adrenal glands are involved, the adrenal lesion must be unequivocally dominant [ 5 ].

PAL occurs predominantly in males in the sixth to seventh decades of life. Most commonly, this lymphoma is a nongerminal center-type diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), which is present in 70% to 80% of the patients [ 6 ]. Patients present with abdominal or lumbar pain; fever; weight loss; and signs of adrenal insufficiency such as hypotension, hyponatremia, fatigue, skin hyperpigmentation, and vomiting [ 7 ]. In occasional instances, it may also be an incidental finding on imaging studies obtained for other purposes, and it is frequently bilateral and bulky at the time of presentation. Several etiological factors, such as Epstein-Barr virus infection, genetic defects in p53 and c-kit, and immune dysregulation, have been implicated in the pathogenesis of this disease [ 5 , 7 ]. Laboratory investigations often show elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), β 2 -microglobulin, C-reactive protein, and ferritinemia, which signify high levels of inflammation associated with PAL [ 6 ].

The prognosis of this condition is generally considered to be poor because PAL is an aggressive disease and progresses rapidly. An average 1-year survival as low as 20% has been reported; however, owing to the rare nature of this disease, prognostic factors are difficult to elucidate [ 5 ].

A 50-year-old Pakistani man known to have had diabetes for 21 years presented to our hospital with progressively increasing pain and fullness in the left upper quadrant of his abdomen, generalized weakness, easy fatigability, and decreased appetite of 1.5 months’ duration. He also complained of nausea and early satiety and had a weight loss of 8 kg over this period. On examination, he was found to have a blood pressure of 140/80 mmHg with no postural drop, a pulse rate of 106 beats/minute, and no fever. His physical examination was otherwise unremarkable. His past medical history was significant for pulmonary tuberculosis 2 years earlier, for which he received antituberculous therapy.

The patient had initially presented at another university hospital 3 weeks earlier. At that time, a laboratory workup and computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen with contrast enhancement were done. Although the results of his complete blood count and renal function test were normal, CT of the abdomen showed a heterogeneous enhancing soft tissue density mass in the left adrenal gland. The mass measured 7.1 × 5.6 cm in transverse and anteroposterior diameter, and the craniocaudal extent of the mass was 9.5 cm. Medially, the mass was abutting the celiac and superior mesenteric arteries, and posteroinferiorly, it was bordering the renal vessels. Paraaortic lymphadenopathy was also present, with the largest one measuring 1.6 cm (Fig. 1 ).

Computed tomography of the patient showing a large left adrenal mass

Further laboratory workup revealed the following levels: sodium 135 mEq/L, potassium 4.5 mEq/L, LDH 905 IU/L, renin 364 IU/ml, aldosterone 5.79 ng/dl, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate 79.20 μg/dl, urinary vanillylmandelic acid 6.4 mg/24 hours, and a low-dose overnight dexamethasone suppression test result of 3.20 μg/dl. The patient was referred to our urology clinic for surgical removal of his mass. He underwent a left adrenalectomy at the urology clinic on 4 March 2016. Histopathological analysis revealed DLBCL (Figs. 2 and 3 ). The results of immunohistochemical stains were strongly positive for CD20 and negative for CD3, CD5, CD10, and cyclin D1. His Ki-67 (Mib-1) index was approximately 80% (Figs. 4 and 5 ).

Low-power view of the lesion showing diffuse sheets of neoplastic cells (hematoxylin and eosin stain)

High-power view of the lesion showing large-sized neoplastic cells with pleomorphic nuclei, variably prominent nucleoli, and scant cytoplasm. Frequent mitotic figures are also noted (hematoxylin and eosin stain)

CD20 immunohistochemical stain (pan-B) is strongly positive for neoplastic cells

Ki-67 immunohistochemical stain highlights a markedly raised proliferative index in the neoplastic lymphoid population

For further management, the patient was referred to our hematology clinic and was planned for a rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) chemotherapy regimen starting on 18 March 2016. He received a total of six cycles of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP; rituximab was not given, owing to financial constraints) and was routinely followed pre- and postchemotherapy at the hematology clinic with complete blood count and serum LDH evaluations. Positron emission tomography (PET) performed on 24 March 2016 showed metabolically active residual disease over the left adrenal bed. Subcentimetric fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) deposits were seen in the patient’s L5, L2, and T12 vertebrae, suggestive of marrow infiltration. No evidence of hypermetabolic nodal, hepatic, or splenic involvement was appreciated. However, the patient responded to chemotherapy and is currently doing well. He gained around 8 kg of weight and is following his routine daily activities. A recent PET scan revealed that the previously seen hypermetabolic foci along the left crus, left proximal paraaortic region, and foci of FDG uptake in the lumbar and thoracic vertebrae were not appreciable. The patient’s Deauville 5-point scale score was 0 (complete metabolic response).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report describing a case of primary adrenal NHL in Pakistan. Our patient was a man in his fifth decade of life, which, on the basis of published literature, is a relatively young age to have this disease. We treated our patient with a regimen of CHOP; rituximab was not included, owing to financial constraints. Even without rituximab, our patient showed a complete response to therapy. Because primary adrenal NHL is a rare disease, optimal treatment has not yet been established. CHOP or CHOP-like regimens were traditionally used before the introduction of rituximab, with generally dismal results (overall survival between 20% and 50%) [ 7 ]. In the largest study to date on PAL, involving 31 patients given an R-CHOP chemotherapy regimen, complete remission and overall response rates were 54.8% and 87.0%, respectively. Surprisingly, no difference was found in overall survival between unilateral and bilateral NHL of the adrenal gland [ 8 ]. Our patient also underwent adrenalectomy; however, the two largest studies to date showed no survival benefit in patients who underwent adrenalectomy as compared with those who were treated with chemotherapy alone [ 6 , 8 ].

In another study involving 28 patients with PAL, 64% of the patients were treated with a CHOP regimen, 50% with an R-CHOP regimen, and 18% had chemotherapy with doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vindesine, bleomycin, and prednisone. The overall survival was 61.6%; however, it was 100% for those who received autologous stem cell transplants, which suggests that this may prolong survival [ 6 ]. The Ki-67 index was high in our patient (80%). Ichikawa et al . reported this index to be greater than 70% in seven patients with primary adrenal DLBCL. They treated all of these patients with rituximab-containing chemotherapy and reported a 2-year survival rate of 57%, although none of the patients died as a result of advancement of lymphoma [ 9 ]. These authors suggested that rituximab-containing chemotherapy with central nervous system (CNS) prophylaxis with methotrexate may be a good treatment option for primary adrenal NHL. Kim et al . reported CNS relapses or progression in four patients, none of whom had received intrathecal prophylaxis [ 8 ].

For our patient, we opted for CT as the initial imaging modality and then confirmed the diagnosis via histology of the resected adrenal gland. Grigg et al . suggested that though magnetic resonance imaging and CT findings can be highly suggestive of NHL, a biopsy should be done for diagnosis. Staging should involve a PET or gallium scan, and in patients with elevated LDH levels, a lumbar puncture should also be done [ 7 ].

According to the International Prognostic Index (IPI), our patient was in the low- to intermediate-risk category, which has an estimated 5-year survival of 51%. However, this scoring system is not specific to PAL; thus, it may be inaccurate in predicting overall survival. Kim et al . found that neither high-risk IPI score nor advanced-stage disease according to the Ann Arbor system had any impact on the overall survival; therefore, they suggested a modified IPI scoring system and a revised staging system, which resulted in significantly improved predictability of overall survival [ 9 ]. The modified scoring and staging criteria may prove beneficial in risk stratification of patients with primary adrenal NHL and also guide treatment.

No protocol for specific treatment in cases of a primary adrenal NHL has yet been established, and multiple authors have used a combination of modalities, including surgery and chemotherapy. Ichikawa et al . argued that perhaps one of the reasons for the poor prognosis is that many patients were previously treated with chemotherapy not containing rituximab and did not receive CNS prophylaxis, which may have decreased overall survival [ 9 ].

PAL is a rare but rapidly progressing disease that should be treated aggressively. Rituximab-containing chemotherapy such as R-CHOP has shown promise by increasing the overall survival of patients with this disease. R-CHOP combined with CNS prophylaxis and autologous stem cell transplant may further increase overall survival, but further studies with larger sample sizes are needed to establish the best treatment option and decide whether surgery and radiation have a role in the management of PAL.

Abbreviations

Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone

Central nervous system

Computed tomography

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

Fluorodeoxyglucose

International Prognostic Index

Lactate dehydrogenase

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- Primary adrenal lymphoma

Positron emission tomography

Rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone

Vinjamaram S, Estrada-Garcia DA, Hernandez-Ilizaliturri FJ. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma: practice essentials [updated 22 Sep 2016]. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/203399-overview . Accessed 30 Sep 2016.

American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2016. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2016. https://old.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@research/documents/document/acspc-047079.pdf . Accessed 6 Jul 2016.

Google Scholar

Kashyap R, Mittal B, Manohar K, Harisankar C, Bhattacharya A, Singh B, et al. Extranodal manifestations of lymphoma on [ 18 F]FDG-PET/CT: a pictorial essay. Cancer Imaging. 2011;11:166–74.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Metser U, Goor O, Lerman H, Naparstek E, Even-Sapir E. PET-CT of extranodal lymphoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:1579–86.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Rashidi A, Fisher SI. Primary adrenal lymphoma: a systematic review. Ann Hematol. 2013;92:1583–93.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Laurent C, Casasnovas O, Martin L, Chauchet A, Ghesquieres H, Aussedat G, et al. Adrenal lymphoma: presentation, management and prognosis. QJM. 2017;110:103–9.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Grigg AP, Connors JM. Primary adrenal lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma. 2003;4:154–60.

Kim YR, Kim JS, Min YH, Hyunyoon D, Shin HJ, Mun YC, et al. Prognostic factors in primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of adrenal gland treated with rituximab-CHOP chemotherapy from the Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma (CISL). J Hematol Oncol. 2012;5:49.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ichikawa S, Fukuhara N, Inoue A, Katsushima H, Ohba R, Katsuoka Y, et al. Clinicopathological analysis of primary adrenal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: effectiveness of rituximab-containing chemotherapy including central nervous system prophylaxis. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2013;2:19.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Sabeeh Siddique for providing the histological figures with explanations.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, because no datasets were generated or analyzed during the present study.

Authors’ contributions

NR conceived of the study and helped to draft the manuscript. OR and SF were involved in patient care and helped write the case presentation. IU and NI also helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Medicine, Section of Endocrinology, Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan

Nanik Ram, Owais Rashid, Imran Ulhaq & Najmul Islam

Aga Khan University, Stadium Road, Karachi, Pakistan

Saad Farooq

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Owais Rashid .

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Ram, N., Rashid, O., Farooq, S. et al. Primary adrenal non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Reports 11 , 108 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-017-1271-x

Download citation

Received : 10 November 2016

Accepted : 21 March 2017

Published : 15 April 2017

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-017-1271-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Adrenal mass

Journal of Medical Case Reports

ISSN: 1752-1947

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma

- • Broad term for cancers that develop in the lymphocytes, which are white blood cells of the lymphatic system

- • Symptoms include swollen lymph nodes, fever, night sweats, fatigue, unintentional weight loss

- • Treatment includes chemotherapy, radiation therapy, immunotherapy, targeted therapy, active surveillance, surgery, stem cell transplant

- • Involves medical oncology, pediatric hematology and oncology, hematology

- Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

- Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma

- Hodgkin Lymphoma

- Follicular Lymphoma

What is non-Hodgkin's lymphoma?

What are the types of non-hodgkin's lymphoma, what are the symptoms of non-hodgkin's lymphoma, what are the risk factors for non-hodgkin lymphoma, how is non-hodgkin's lymphoma diagnosed, how is non-hodgkin's lymphoma treated, what is the outlook for people with non-hodgkin's lymphoma, what makes yale medicine unique in its treatment of non-hodgkin's lymphoma.

When a person has painless, enlarged lymph nodes that don’t shrink after a short period of time, doctors may suspect lymphoma, especially if they have had unexplained weight loss or other concerning symptoms, like fever or night sweats.

Doctors classify lymphomas—cancers of the white blood cells known as lymphocytes—into two broad categories: Hodgkin's lymphoma and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. The conditions have some overlapping symptoms, but doctors (i.e. hematopathologists) tell the difference between the lymphomas by reviewing a biopsy of the affected cells.

More than 81,000 Americans are diagnosed with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma each year, including around 800 children and teenagers. It’s more common among males, older adults, and people with European ancestry.

Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma may occur at any number of places within the body. Some types are slow-spreading—without many symptoms—while others are aggressive, spreading quickly with notable symptoms. Different types of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma respond to treatment differently, and some types have better prognoses than others.

“Since there are more than 60 different subtypes of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, adequate tissue biopsy and review by experienced pathologists is a key first step to managing a new diagnosis of lymphoma,” says Scott Huntington, MD , an Associate Professor of Internal Medicine (Hematology) at Yale Cancer Center.

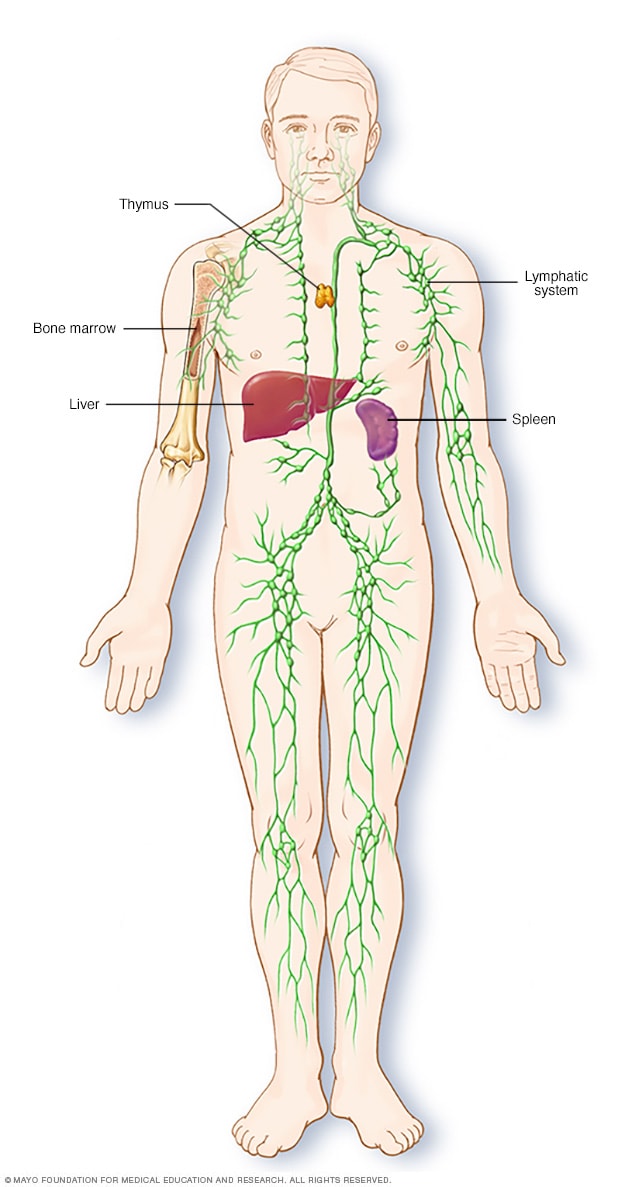

Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma is an umbrella term for several different types of cancer of the lymphocytes, which are white blood cells found within the lymphatic system, part of the immune system. These non-Hodgkin's cancers don’t contain Reed-Sternberg cells, which are the name for the abnormal cells present in people with Hodgkin's lymphoma.

Within the immune system, different lymphocytes help to keep people healthy in different ways:

- B cells produce antibodies that help people fight infections

- T cells assist B cells, allowing them to create antibodies, which fight infection

- Natural killer (NK) cells fight viruses and cancer cells

All of these specialized white blood cells exist within the lymphatic system, a series of vessels that connect the lymph nodes throughout the body. Within the lymph nodes, these lymphocytes help to filter harmful cells out of the fluid traveling through the lymphatic system.

Other elements of the lymphatic system include the bone marrow, spleen, tonsils, adenoids and thymus, as well as parts of the digestive system and central nervous system.

Someone develops non-Hodgkin's lymphoma when their B-cell, T-cell or NK-cell lymphocytes mutate and multiply uncontrollably. Most commonly, the B cells are affected. (The most common type of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma is diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.)

Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma may develop within the lymph nodes, bone marrow, or any other lymphatic tissue in the body. For example, primary central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma develops in lymph tissue within the brain or spinal cord.

Commonly diagnosed types of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma include:

- Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

- Follicular lymphoma

- Burkitt lymphoma

- Mantle cell lymphoma

- Anaplastic large cell lymphoma

- Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma

- Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma

- Peripheral T-cell lymphoma

- Small lymphocytic lymphoma or chronic lymphocytic leukemia

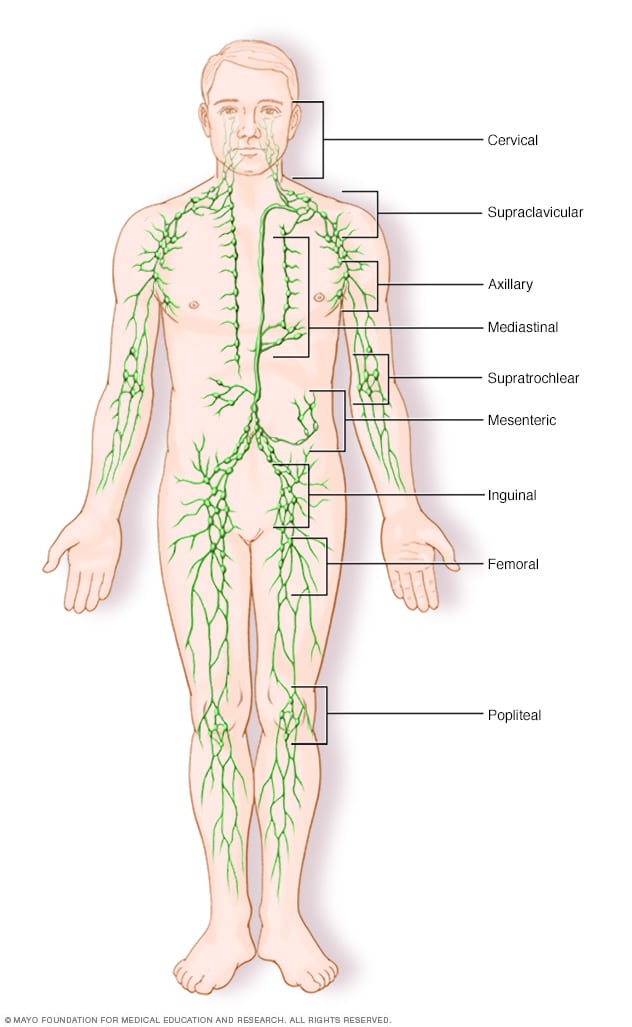

Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma may cause a number of symptoms, including:

- Painless, enlarged lymph nodes, often in the neck, armpits, or groin

- Night sweats

- Unintentional weight loss

- Pain in the chest or abdomen

Additionally, some types of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma affect organs outside of the lymphatic system, which may lead to symptoms specific to those organs. If the brain is affected (such as in Central Nervous System [CNS] lymphoma), people may experience neurological symptoms, or if the intestines are involved, people may have gastrointestinal problems.

Doctors don’t know why non-Hodgkin's lymphoma develops, but people who are at greater risk of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma include those who have, or have had:

- An inherited immune disorder

- Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), which may manifest as infectious mononucleosis (mono)

- Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

- Hepatitis B or C

- Organ transplants, because of the daily immunosuppressant medication

- Autoimmune diseases, such as Sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, Hashimoto’s disease or celiac disease

- History of prior Hodgkin's lymphoma

Additionally, people are at greater risk if they have been exposed to:

- Agricultural chemicals, such as herbicide or insecticide

- Organic solvents, which may be used in paints, glues, dyes and other products

- Radiation therapy

- A high-fat diet

- Ultraviolet radiation Smoking

Doctors confirm non-Hodgkin's lymphoma with a biopsy, but they may suspect the condition after learning about a person’s symptoms, including fever and unexplained weight loss.

During a physical exam, doctors look for enlarged lymph nodes in the neck, chest, and/or groin area. They also ask questions about a patient’s medical history, including HIV status, hepatitis status, whether someone has an autoimmune disease and if they’ve been exposed to certain chemicals at work. Additionally, doctors ask about a family history of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and other conditions.

When doctors suspect non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, they may ask for additional tests, including a CT scan, a PET scan, blood tests, and a biopsy.

To confirm a suspected diagnosis, doctors surgically remove a lymph node or a section of a lymph node, then biopsy the tissue. They may also biopsy someone’s bone marrow to check for the condition before making a diagnosis, since the bone marrow may be affected.

A variety of treatment approaches may be used for people with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Some are appropriate for people with low-grade or slow-spreading disease, while others are recommended for people with aggressive or advanced disease.

Options include:

- An active surveillance approach, which may be right for people with low-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma that doesn’t need treatment upon diagnosis

- Chemotherapy, which combines a number of chemotherapy drugs that are designed to target different types of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma

- Targeted therapy, which attacks cancer cells in different ways than chemotherapy drugs

- Immunotherapy, such as monoclonal antibodies or chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, which may help the person’s immune system fight the cancer more aggressively

- Radiation therapy, which may be effective when non-Hodgkin's lymphoma is localized and hasn’t moved beyond the lymph nodes; or it may be given to someone after chemotherapy or another treatment regimen. Because possible long-term side effects from radiation therapy can be serious, doctors may avoid using it—or use only low-dose radiation—to treat children.

- Stem cell transplantation with high-dose chemotherapy, which may be given to people who don’t respond well to other treatments or those who relapse

The long-term prognosis for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma varies, depending on the type of disease and whether it’s slow-spreading or aggressive, in addition to other factors, such as a person’s age and overall health. The outlook for most kids and adolescents with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma is good, with survival rates over 90% for those with early-stage disease and between 80% and 90% for more advanced non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

“Diagnostic evaluation and treatments available for non-Hodgkin lymphoma have changed dramatically over the last decade,” says Dr. Huntington. “Yale has expertise across the non-Hodgkin lymphoma care continuum, including pathologists reviewing biopsy specimens, radiologists helping with lymphoma staging, expert clinicians in hematology/oncology, and therapeutic radiation to help optimize treatment outcomes. The multidisciplinary group of physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, and support staff provide the highest level of care and help facilitate the delivery of several innovative treatment modalities (including stem cell transplantation, and chimeric antigen receptor T cell treatment), which are not available at other Connecticut centers.”

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma

Parts of the immune system

The lymphatic system is part of the body's immune system, which protects against infection and disease. The lymphatic system includes the spleen, thymus, lymph nodes and lymph channels, as well as the tonsils and adenoids.

Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma is a type of cancer that begins in your lymphatic system, which is part of the body's germ-fighting immune system. In non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, white blood cells called lymphocytes grow abnormally and can form growths (tumors) throughout the body.

Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma is a general category of lymphoma. There are many subtypes that fall in this category. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma are among the most common subtypes. The other general category of lymphoma is Hodgkin's lymphoma.

Advances in diagnosis and treatment of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma have helped improve the prognosis for people with this disease.

Products & Services

- A Book: Living Medicine

- Mayo Clinic Comprehensive Cancer Center

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma

- Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma

- Follicular lymphoma

- Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia

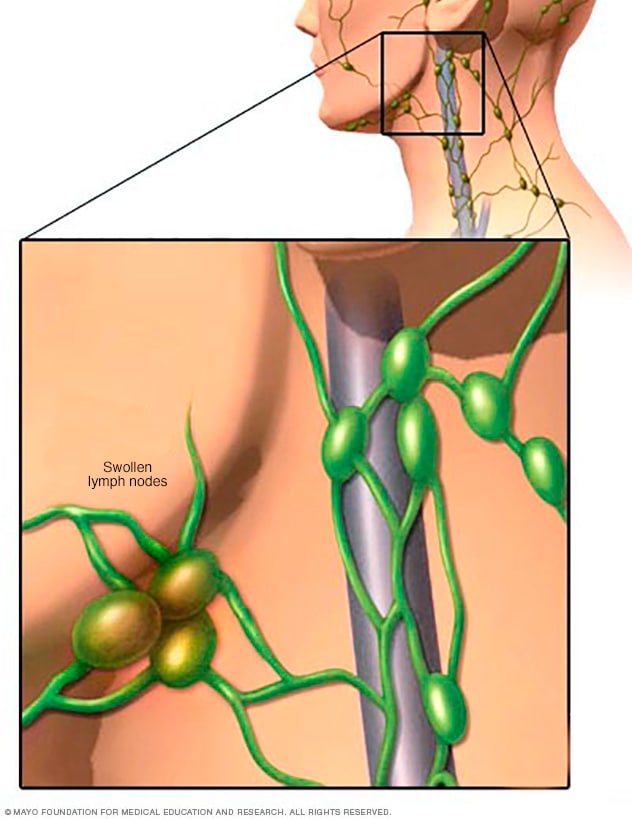

Swollen lymph nodes

One of the most common places to find swollen lymph nodes is in the neck. The inset shows three swollen lymph nodes below the lower jaw.

Signs and symptoms of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma may include:

- Swollen lymph nodes in your neck, armpits or groin

- Abdominal pain or swelling

- Chest pain, coughing or trouble breathing

- Persistent fatigue

- Night sweats

- Unexplained weight loss

When to see a doctor

Make an appointment with your doctor if you have any persistent signs and symptoms that worry you.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

Get Mayo Clinic cancer expertise delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe for free and receive an in-depth guide to coping with cancer, plus helpful information on how to get a second opinion. You can unsubscribe at any time. Click here for an email preview.

Error Select a topic

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing

Your in-depth coping with cancer guide will be in your inbox shortly. You will also receive emails from Mayo Clinic on the latest about cancer news, research, and care.

If you don’t receive our email within 5 minutes, check your SPAM folder, then contact us at [email protected] .

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

Lymph node clusters

Lymph nodes are bean-sized collections of cells called lymphocytes. Hundreds of these nodes cluster throughout the lymphatic system, for example, near the knee, groin, neck and armpits. The nodes are connected by a network of lymphatic vessels.

In most instances, doctors don't know what causes non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. It begins when your body produces too many abnormal lymphocytes, which are a type of white blood cell.

Normally, lymphocytes go through a predictable life cycle. Old lymphocytes die, and your body creates new ones to replace them. In non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, your lymphocytes don't die, and your body keeps creating new ones. This oversupply of lymphocytes crowds into your lymph nodes, causing them to swell.

B cells and T cells

Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma most often begins in the:

- B cells. B cells are a type of lymphocyte that fights infection by producing antibodies to neutralize foreign invaders. Most non-Hodgkin's lymphoma arises from B cells. Subtypes of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma that involve B cells include diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma and Burkitt lymphoma.

- T cells. T cells are a type of lymphocyte that's involved in killing foreign invaders directly. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma occurs much less often in T cells. Subtypes of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma that involve T cells include peripheral T-cell lymphoma and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

Whether your non-Hodgkin's lymphoma arises from your B cells or T cells helps to determine your treatment options.

Where non-Hodgkin's lymphoma occurs

Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma generally involves the presence of cancerous lymphocytes in your lymph nodes. But the disease can also spread to other parts of your lymphatic system. These include the lymphatic vessels, tonsils, adenoids, spleen, thymus and bone marrow. Occasionally, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma involves organs outside of your lymphatic system.

Risk factors

Most people diagnosed with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma don't have any obvious risk factors. And many people who have risk factors for the disease never develop it.

Some factors that may increase the risk of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma include:

- Medications that suppress your immune system. If you've had an organ transplant and take medicines that control your immune system, you might have an increased risk of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.

- Infection with certain viruses and bacteria. Certain viral and bacterial infections appear to increase the risk of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Viruses linked to this type of cancer include HIV and Epstein-Barr infection. Bacteria linked to non-Hodgkin's lymphoma include the ulcer-causing Helicobacter pylori.

- Chemicals. Certain chemicals, such as those used to kill insects and weeds, may increase your risk of developing non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. More research is needed to understand the possible link between pesticides and the development of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.

- Older age. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma can occur at any age, but the risk increases with age. It's most common in people 60 or over.

Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma care at Mayo Clinic

Living with non-hodgkin's lymphoma?

Connect with others like you for support and answers to your questions in the Blood Cancers & Disorders support group on Mayo Clinic Connect, a patient community.

Blood Cancers & Disorders Discussions

374 Replies Sat, May 11, 2024

4 Replies Thu, May 09, 2024

58 Replies Thu, May 09, 2024

- AskMayoExpert. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (adult). Mayo Clinic; 2018.

- B-cell lymphomas. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx. Accessed Feb. 5, 2021.

- T-cell lymphomas. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx. Accessed Feb. 5, 2021.

- Hoffman R, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and Burkitt lymphoma. In: Hematology: Basic Principles and Practice. 7th ed. Elsevier; 2018. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed Feb. 5, 2021.

- Lymphoma — Non-Hodgkin. Cancer.Net. https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/41246/view-all. Accessed Feb. 11, 2021.

- Laurent C, et al. Impact of expert pathologic review of lymphoma diagnosis: Study of patients from the French Lymphopath Network. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017; doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.71.2083.

- Distress management. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx. Accessed Feb. 11, 2021.

- Nowakowski GS, et al. Integrating precision medicine through evaluation of cell of origin treatment planning for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Cancer Journal. 2019; doi:10.1038/s41408-019-0208-6.

- Lymphoma SPOREs. National Cancer Institute. https://trp.cancer.gov/spores/lymphoma.htm. Accessed Feb. 11, 2021.

- Warner KJ. Allscripts EPSi. Mayo Clinic. Jan. 7, 2021.

- Member institutions. Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology. https://www.allianceforclinicaltrialsinoncology.org/main/public/standard.xhtml?path=%2FPublic%2FInstitutions. Accessed Feb. 11, 2021.

- Member institution lists. NRG Oncology. https://www.nrgoncology.org/About-Us/Membership/Member-Institution-Lists. Accessed Feb. 11, 2021.

- Pruthi RK (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. Feb. 22, 2021.

Associated Procedures

- Bone marrow biopsy

- Bone marrow transplant

- Chemotherapy

- Positron emission tomography scan

- Radiation therapy

News from Mayo Clinic

- All-Star pitcher Liam Hendriks shares how he closed out cancer at Mayo Clinic in Arizona July 21, 2023, 10:08 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Q and A: What is lymphoma? Nov. 03, 2022, 01:04 p.m. CDT

- Researchers seek to improve success of chimeric antigen receptor-T cell therapy in non-Hodgkin lymphoma May 12, 2022, 07:04 p.m. CDT

Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida, and Mayo Clinic in Phoenix/Scottsdale, Arizona, have been recognized among the top Cancer hospitals in the nation for 2023-2024 by U.S. News & World Report.

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

- Doctors & departments

- Care at Mayo Clinic

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

You are using an outdated browser. Upgrade your browser today or install Google Chrome Frame to better experience this site.

- Submit Manuscript

Oncology Letters

- International Journal of Oncology

- Molecular and Clinical Oncology

- Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine

- International Journal of Molecular Medicine

- Biomedical Reports

- Oncology Reports

- Molecular Medicine Reports

- World Academy of Sciences Journal

- International Journal of Functional Nutrition

- International Journal of Epigenetics

- Medicine International

- Journal Home

- Current Issue

- Forthcoming Issue

- Open Special Issues

- About Special Issues

- Submit Paper

- Past Two Years

- Past Year 0

- Information

- Online Submission

- Information for Authors

- Language Editing

- Information for Reviewers

- Editorial Policies

- Editorial Board

- Join Editorial Board

- Aims and Scope

- Abstracting and Indexing

- Bibliographic Information

- Information for Librarians

- Information for Advertisers

- Reprints and permissions

- Contact the Editor

- General Information

- About Spandidos

- Conferences

- Job Opportunities

- Terms and Conditions

Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma with uncommon clinical manifestations: A case report

- Yu‑Long Cai

- Xian‑Ze Xiong

- Nan‑Sheng Cheng

View Affiliations

- Corresponding author: Author name

- Published online on: July 15, 2015 https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2015.3493

- Pages: 1686-1688

This article is mentioned in:

Introduction.

Extranodal lymphoma occurs in ~40% of all patients with lymphoma and has been described in virtually all organs and tissue ( 1 ). Extranodal disease is more common with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) ( 2 ), and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common histological NHL subtype in adults, accounting for ~25% of all NHL cases ( 3 ). Thus, it is known that gastrointestinal DLBCL is the most frequent form of extranodal lymphoma ( 4 ). However, DLBCL primarily arising in the retroperitoneal region has been rarely reported. The largest series on retroperitoneal DLBCL was published by Pileri et al in 2001 ( 5 ). Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, primary retroperitoneal lymphoma without renal and ureteral involvement affecting the genitourinary system has not been reported until now.

Here, we report the extremely rare case of a young female suffering with primary DLBCL located in the retroperitoneal and gastrointestinal region simultaneously. Unusually, the first symptom of this disease was renal colic. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for inclusion in the present study.

Case report

Case presentation.

A 33-year-old female presented with a 2-month history of renal colic and abdominal pain, which became aggravated at night. No fever was noted, but there was hematuria when the pain occurred. The patient's weight remained unchanged. Her family history was not contributory. Surgical history included two Caesarean sections 13 and 9 years prior.

Physical examination revealed an ill-defined mass in the right lower hypogastrium and tenderness in the abdomen, but without abdominal distention. There were no enlarged or palpable lymph nodes. The remaining systemic examination was not significant. The peripheral blood count was unremarkable (hemoglobin 109 g/l, red blood cell count 3.81×10 12 /l, white blood cell count 3.05×10 9 /l, and platelet count 230×10 9 /l). The peripheral blood smear revealed no immature cells (66.2% neutrophils, 25.6% lymphocytes, 7.2% monocytes, 1.0% eosinophils and 0.0% basophils). Liver and renal functional tests, bilirubin and electrolytes were normal. Serum tumor markers were negative with the exception of CA-125 values of 63.88 U/ml (normal value, <35 U/ml). The remaining laboratory tests were all within the normal limits.

A normal chest X-ray was obtained. An abdominopelvic contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan ( Fig. 1 ) revealed: i) A bulky soft-tissue dense mass in the middle of the ascending colon and superior to the ileocecum; heterogeneous enhancement following enhanced scan; thickened anterior of the renal fascia of the right kidney and local parietal peritoneum. ii) Multiple renal cysts in both kidneys. The CT scan did not indicate any bowel involvement, distant metastasis or abdominal lymph node enlargement. The abdominal ultrasound did not reveal any coexisting lesion in the hepato-pancreato-biliary system. Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) renal imaging (99mTc-DTPA) revealed that the glomerular filtration rate was slightly decreased and the upper urinary tract had unobstructed drainage in the two kidneys.

Surgical treatment

Since the tumor had no distant involvement and there was no evidence of worsening symptoms (renal colic and abdominal pain), the patient underwent surgical resection. Intra-operative findings were as follows: no ascites were in the abdominal cavity; no dilation of the small and large bowel; the mass was predominantly located in the right mesocolon and retroperitoneal region, and extended to the distal ileum, ascending colon and the beginning of the transverse colon. Intra-operative biopsy and frozen section study indicated malignancy but did not confirm the tumor type. Complete excision was performed, retaining the right kidney and right ureter due to their lack of involvement. Side-to-side anastomosis of the transverse colon and ileum was used. The patient had an uneventful postoperative recovery. She was discharged from the surgical ward and referred to the hematology clinic for additional evaluation and adjuvant chemotherapy.

Pathological evaluation

The tumor consisted of two masses. The first mass (measuring 9×8×7 cm) was located in the retroperitoneal region, and the second (measuring 2.5×2×2 cm) was located in the mucosa of the ileum, involving the submucosa and muscularis layers as well as the serosa. There was no association between the two masses.

Pathological assessment was performed using immunohistochemistry staining, which revealed positivity for CD20 and Ki67) ( Fig. 2 ). DLBCL was the final confirmed diagnosis.

The patient's general condition remained good and she went on to receive CHOP chemotherapy. After 3 months of follow-up, no postoperative complications were identified.

DLBCL is the most common type of lymphoma worldwide ( 6 ). However, NHL rarely presents with a retroperitoneal or pelvic mass; during post-mortem studies of NHL patients an incident of less than 1% incidence was noted ( 7 ). Due to the uncommon anatomical location, the diagnosis and subsequent management of these patients tend to be difficult. The initial presentation of NHL varies depending on the subtype and involved area, with symptoms including enlarged palpable lymphadenopathy, B-symptoms (fever, weight loss, night sweats), and symptoms secondary to compression of adjacent structures. This is a unique case of retroperitoneal DLBLC, in which the first manifestation was renal colic.

Renal colic mainly occurs in patients with renal or ureteral calculus. Based on the findings of the abdominal CT, abdominal X-ray and SPECT renal imaging, our patient did not suffer with renal or ureteral calculus. Certain studies have reported that the genitourinary system may be affected by retroperitoneal NHL. Domazetovski et al ( 8 ) presented a case of acute renal failure in a patient with DLBLC, and Jaeger et al ( 9 ) reported DLBLC in a male presenting with ureteral stricture. However, the majority of cases have primary renal lymphoma or renal involvement. Renal colic alone without genitourinary involvement, as observed in our patient, is extremely rare, and could only be confirmed by surgery in our case. When the patient initially presented at our hospital, we considered that malignant retroperitoneal tumors account for ~0.1% of all malignancies ( 10 ) and are more common than benign tumors in the retroperitoneal space ( 11 ). As the symptom of renal colic was increasing, it was speculated that there was a high possibility of renal involvement. It is known that the most effective treatment is surgical removal of the tumors, with the exception of chemosensitive tumors, and that a definitive diagnosis can usually be made from the surgical specimens ( 12 ). Thus, considering the patient's wishes, surgery was performed.

Unexpectedly, the tumors were located not only in the retroperitoneal region, but also in the ileum. The latter was relatively small, therefore no signs or symptoms had been noted. According to our pathological evaluation, there was no association between the two masses. Literature regarding this condition is lacking, thus a reasonable explanation may be the variety of extranodal lymphoma. Moreover, surgery indicated that the tumor did not infiltrate the renal or ureteral areas. Thus, renal colic was determined to have been the result of compression.

Although CT is the diagnostic modality of choice ( 13 ), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) offers superior soft-tissue contrast in comparison with CT. Indeed, a variety of contrast mechanisms have previously been explored for the characterization of lymphoma in the retroperitoneum, including T2-weighted imaging, diffusion-weighted imaging and dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging ( 14 ). The absence of MRI is a limitation in our diagnostic process. In the study of Tambo et al ( 12 ), a clinicopathological review of 46 primary retroperitoneal tumors identified that MRI imaging diagnosis prior to surgery was compatible with the histological diagnosis in only 26 patients (57%), and all six malignant lymphoma patients underwent biopsy or surgical resection. Therefore, if clinical diagnosis cannot be determined by MRI, definitive histological diagnosis by biopsy or tumor resection is required in order to determine the appropriate treatment.

Currently, CHOP therapy is the treatment of choice for DLBLC patients. Since rituximab is a chimeric anti-CD20 IgG1 monoclonal antibody which is a cell surface protein that occurs almost exclusively in mature B-cells, the combination of rituximab and CHOP is likely become the standard for treating patients with DLBLC ( 15 ). The prognosis has improved in recent years owing to the development of various aggressive chemotherapeutic regimens depending on the histological type, stage and age of each patient. Therefore, a definitive histological diagnosis is essential for patients with DLBLC. Our patient did not present with any specific indications for the diagnosis of this rare tumor as the initial manifestation was renal colic. Surgery has a key role in establishing a definitive diagnosis.

Primary retroperitoneal DLBLC has a variable and non-specific presentation and may resemble other neoplastic or inflammatory conditions. Manifestations, laboratory data and imaging alone may initially lead to an incorrect diagnosis. Obtaining a definitive histological diagnosis by surgery and using appropriate chemotherapy played an essential role in the recovery of our patient. This case study indicates the significance of including a differential diagnosis of primary retroperitoneal NHL in patients presenting with a retroperitoneal mass where the first sign of this disease is renal colic.

- Related Articles

September-2015 Volume 10 Issue 3

Print ISSN: 1792-1074 Online ISSN: 1792-1082

Sign up for eToc alerts

Recommend to Library

- Article Options

- Download article ▽ Download PDF Download XML View XML

- View Abstract

- Cite This Article

- Download Citation

- Create Citation Alert

- Remove Citation Alert

- on Spandidos Publications

- Similar Articles

- on Google Scholar

- © Get Permissions

- Journal Metrics

- Impact Factor: 2.9

- Ranked Oncology (total number of cites)

- CiteScore: 6.3

- CiteScore Rank: Q2: #119/366 Oncology

- Source Normalized Impact per Paper (SNIP): 0.725

- SCImago Journal Rank (SJR): 0.639

This site uses cookies

You can change your cookie settings at any time by following the instructions in our Cookie Policy . To find out more, you may read our Privacy Policy . I agree

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

Advances in Lymphoma Research

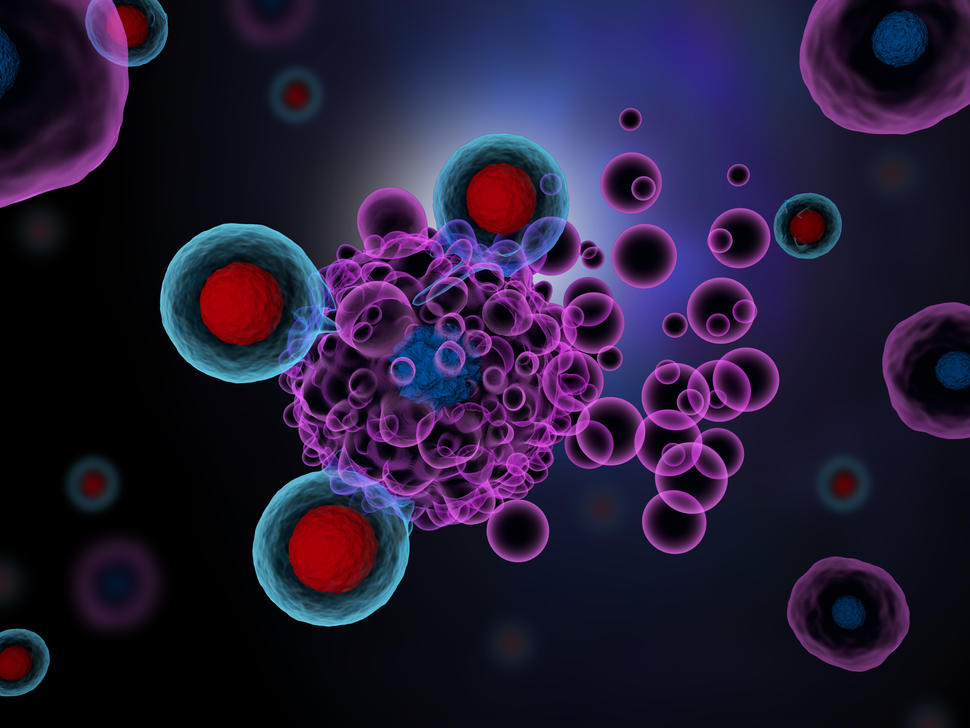

Artist’s rendering of T cells (red and blue spheres) attacking cancer cells. T-cell therapy has been effective in treating certain lymphoma patients.

NCI-funded researchers are working to advance our understanding of how to treat lymphoma . All lymphomas start in the cells of the lymph system , which is part of the body’s immune system. Lymphomas are grouped into two main types: Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (sometimes called NHL). But more than 70 different subtypes of the disease exist. Advances in understanding the gene changes that can lead to lymphoma are now helping scientists design more personalized treatments for these subtypes.

This page highlights some of the latest lymphoma research, including clinical advances that may soon translate into improved care and research findings from recent studies.

Treatment of Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL)

Most people diagnosed with lymphoma have a subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma can either be aggressive or indolent .

Aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma grows and spreads quickly and usually requires immediate treatment. With modern treatment regimens, almost 70% of people with aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma will be considered cured. Research is now largely focused on finding better treatments for the minority of people with aggressive lymphoma who are not cured with initial therapy.

Indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma grows slowly, and in some cases may not cause symptoms for years. People with indolent disease can often postpone treatment until their symptoms worsen, with no negative effects on survival. But sometimes an indolent lymphoma can turn into aggressive lymphoma, which requires immediate treatment.

Indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma largely cannot be cured. The past two decades have seen improvements in extending the survival of people who are treated for this type of lymphoma. However, researchers are studying how to improve long-term survival further and working toward potentially curative treatments.

Chemotherapy , radiation therapy , targeted therapy , and immunotherapy are all used in the treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. A stem cell transplant is sometimes used for lymphoma that has recurred, but this procedure has serious side effects. Four CAR T-cell therapies have been approved to treat some types of recurrent lymphoma. However, these newer therapies still can't cure many people with recurrent lymphoma.

Most research on treatment for non-Hodgkin lymphoma is now focused on targeted therapy and immunotherapy. Researchers are also trying to identify gene changes in different types of lymphoma that might be targets for new drug development.

For example, in 2018, a study led by NCI researchers identified genetic subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (the most common type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma) that could help explain why some patients with the disease respond to treatment and others don’t. Further studies may lead to more tailored treatments for patients with this type of lymphoma.

New targeted therapies

A signaling pathway is a series of chemical reactions that control one or more cell functions. Many types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma are driven by a signaling pathway called the B-cell receptor signaling pathway. A drug called ibrutinib (Imbruvica) has been developed to shut down that pathway. It is being used and tested in a number of ways:

- In the last several years, the drug has been approved for the treatment of small lymphocytic lymphoma and Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia , both indolent non-Hodgkin lymphomas.

- NCI took part in a randomized clinical trial that tested the addition of ibrutinib to chemotherapy and rituximab (Rituxan) in people newly diagnosed with a certain type of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma . People over the age of 60 had worse outcomes with the addition of ibrutinib. However, patients under the age of 60 who were given ibrutinib had substantially improved survival .

- Other studies have suggested that people whose diffuse large B-cell lymphoma has specific genetic characteristics may especially benefit from treatment with ibrutinib .

- An early-phase NCI-sponsored study tested ibrutinib plus chemotherapy in people with primary central nervous system lymphoma , a very aggressive subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. More than half of the patients in this small study went into complete, long-term remission. A larger study is now underway at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center . That study is also testing this combination in people with lymphoma that began elsewhere in the body but has spread to the central nervous system.

The FDA has approved two other drugs that target the B-cell receptor signaling pathway. Acalabrutinib (Calquence) is approved for relapsed mantle cell lymphoma and small lymphocytic lymphoma . An ongoing study at NCI is testing acalabrutinib, in combination with chemotherapy and rituximab , in people with previously untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

In 2019, zanubrutinib (Brukinsa) was approved for relapsed mantle cell lymphoma. A fourth drug targeting the B-cell receptor signaling pathway, called pirtobrutinib (Jaypirca) , is now being tested in clinical trials for several different types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. In 2023, it was approved for the treatment of mantle cell lymphoma that has gotten worse after two or more previous treatments.