- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 8. The Discussion

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The purpose of the discussion section is to interpret and describe the significance of your findings in relation to what was already known about the research problem being investigated and to explain any new understanding or insights that emerged as a result of your research. The discussion will always connect to the introduction by way of the research questions or hypotheses you posed and the literature you reviewed, but the discussion does not simply repeat or rearrange the first parts of your paper; the discussion clearly explains how your study advanced the reader's understanding of the research problem from where you left them at the end of your review of prior research.

Annesley, Thomas M. “The Discussion Section: Your Closing Argument.” Clinical Chemistry 56 (November 2010): 1671-1674; Peacock, Matthew. “Communicative Moves in the Discussion Section of Research Articles.” System 30 (December 2002): 479-497.

Importance of a Good Discussion

The discussion section is often considered the most important part of your research paper because it:

- Most effectively demonstrates your ability as a researcher to think critically about an issue, to develop creative solutions to problems based upon a logical synthesis of the findings, and to formulate a deeper, more profound understanding of the research problem under investigation;

- Presents the underlying meaning of your research, notes possible implications in other areas of study, and explores possible improvements that can be made in order to further develop the concerns of your research;

- Highlights the importance of your study and how it can contribute to understanding the research problem within the field of study;

- Presents how the findings from your study revealed and helped fill gaps in the literature that had not been previously exposed or adequately described; and,

- Engages the reader in thinking critically about issues based on an evidence-based interpretation of findings; it is not governed strictly by objective reporting of information.

Annesley Thomas M. “The Discussion Section: Your Closing Argument.” Clinical Chemistry 56 (November 2010): 1671-1674; Bitchener, John and Helen Basturkmen. “Perceptions of the Difficulties of Postgraduate L2 Thesis Students Writing the Discussion Section.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 5 (January 2006): 4-18; Kretchmer, Paul. Fourteen Steps to Writing an Effective Discussion Section. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008.

Structure and Writing Style

I. General Rules

These are the general rules you should adopt when composing your discussion of the results :

- Do not be verbose or repetitive; be concise and make your points clearly

- Avoid the use of jargon or undefined technical language

- Follow a logical stream of thought; in general, interpret and discuss the significance of your findings in the same sequence you described them in your results section [a notable exception is to begin by highlighting an unexpected result or a finding that can grab the reader's attention]

- Use the present verb tense, especially for established facts; however, refer to specific works or prior studies in the past tense

- If needed, use subheadings to help organize your discussion or to categorize your interpretations into themes

II. The Content

The content of the discussion section of your paper most often includes :

- Explanation of results : Comment on whether or not the results were expected for each set of findings; go into greater depth to explain findings that were unexpected or especially profound. If appropriate, note any unusual or unanticipated patterns or trends that emerged from your results and explain their meaning in relation to the research problem.

- References to previous research : Either compare your results with the findings from other studies or use the studies to support a claim. This can include re-visiting key sources already cited in your literature review section, or, save them to cite later in the discussion section if they are more important to compare with your results instead of being a part of the general literature review of prior research used to provide context and background information. Note that you can make this decision to highlight specific studies after you have begun writing the discussion section.

- Deduction : A claim for how the results can be applied more generally. For example, describing lessons learned, proposing recommendations that can help improve a situation, or highlighting best practices.

- Hypothesis : A more general claim or possible conclusion arising from the results [which may be proved or disproved in subsequent research]. This can be framed as new research questions that emerged as a consequence of your analysis.

III. Organization and Structure

Keep the following sequential points in mind as you organize and write the discussion section of your paper:

- Think of your discussion as an inverted pyramid. Organize the discussion from the general to the specific, linking your findings to the literature, then to theory, then to practice [if appropriate].

- Use the same key terms, narrative style, and verb tense [present] that you used when describing the research problem in your introduction.

- Begin by briefly re-stating the research problem you were investigating and answer all of the research questions underpinning the problem that you posed in the introduction.

- Describe the patterns, principles, and relationships shown by each major findings and place them in proper perspective. The sequence of this information is important; first state the answer, then the relevant results, then cite the work of others. If appropriate, refer the reader to a figure or table to help enhance the interpretation of the data [either within the text or as an appendix].

- Regardless of where it's mentioned, a good discussion section includes analysis of any unexpected findings. This part of the discussion should begin with a description of the unanticipated finding, followed by a brief interpretation as to why you believe it appeared and, if necessary, its possible significance in relation to the overall study. If more than one unexpected finding emerged during the study, describe each of them in the order they appeared as you gathered or analyzed the data. As noted, the exception to discussing findings in the same order you described them in the results section would be to begin by highlighting the implications of a particularly unexpected or significant finding that emerged from the study, followed by a discussion of the remaining findings.

- Before concluding the discussion, identify potential limitations and weaknesses if you do not plan to do so in the conclusion of the paper. Comment on their relative importance in relation to your overall interpretation of the results and, if necessary, note how they may affect the validity of your findings. Avoid using an apologetic tone; however, be honest and self-critical [e.g., in retrospect, had you included a particular question in a survey instrument, additional data could have been revealed].

- The discussion section should end with a concise summary of the principal implications of the findings regardless of their significance. Give a brief explanation about why you believe the findings and conclusions of your study are important and how they support broader knowledge or understanding of the research problem. This can be followed by any recommendations for further research. However, do not offer recommendations which could have been easily addressed within the study. This would demonstrate to the reader that you have inadequately examined and interpreted the data.

IV. Overall Objectives

The objectives of your discussion section should include the following: I. Reiterate the Research Problem/State the Major Findings

Briefly reiterate the research problem or problems you are investigating and the methods you used to investigate them, then move quickly to describe the major findings of the study. You should write a direct, declarative, and succinct proclamation of the study results, usually in one paragraph.

II. Explain the Meaning of the Findings and Why They are Important

No one has thought as long and hard about your study as you have. Systematically explain the underlying meaning of your findings and state why you believe they are significant. After reading the discussion section, you want the reader to think critically about the results and why they are important. You don’t want to force the reader to go through the paper multiple times to figure out what it all means. If applicable, begin this part of the section by repeating what you consider to be your most significant or unanticipated finding first, then systematically review each finding. Otherwise, follow the general order you reported the findings presented in the results section.

III. Relate the Findings to Similar Studies

No study in the social sciences is so novel or possesses such a restricted focus that it has absolutely no relation to previously published research. The discussion section should relate your results to those found in other studies, particularly if questions raised from prior studies served as the motivation for your research. This is important because comparing and contrasting the findings of other studies helps to support the overall importance of your results and it highlights how and in what ways your study differs from other research about the topic. Note that any significant or unanticipated finding is often because there was no prior research to indicate the finding could occur. If there is prior research to indicate this, you need to explain why it was significant or unanticipated. IV. Consider Alternative Explanations of the Findings

It is important to remember that the purpose of research in the social sciences is to discover and not to prove . When writing the discussion section, you should carefully consider all possible explanations for the study results, rather than just those that fit your hypothesis or prior assumptions and biases. This is especially important when describing the discovery of significant or unanticipated findings.

V. Acknowledge the Study’s Limitations

It is far better for you to identify and acknowledge your study’s limitations than to have them pointed out by your professor! Note any unanswered questions or issues your study could not address and describe the generalizability of your results to other situations. If a limitation is applicable to the method chosen to gather information, then describe in detail the problems you encountered and why. VI. Make Suggestions for Further Research

You may choose to conclude the discussion section by making suggestions for further research [as opposed to offering suggestions in the conclusion of your paper]. Although your study can offer important insights about the research problem, this is where you can address other questions related to the problem that remain unanswered or highlight hidden issues that were revealed as a result of conducting your research. You should frame your suggestions by linking the need for further research to the limitations of your study [e.g., in future studies, the survey instrument should include more questions that ask..."] or linking to critical issues revealed from the data that were not considered initially in your research.

NOTE: Besides the literature review section, the preponderance of references to sources is usually found in the discussion section . A few historical references may be helpful for perspective, but most of the references should be relatively recent and included to aid in the interpretation of your results, to support the significance of a finding, and/or to place a finding within a particular context. If a study that you cited does not support your findings, don't ignore it--clearly explain why your research findings differ from theirs.

V. Problems to Avoid

- Do not waste time restating your results . Should you need to remind the reader of a finding to be discussed, use "bridge sentences" that relate the result to the interpretation. An example would be: “In the case of determining available housing to single women with children in rural areas of Texas, the findings suggest that access to good schools is important...," then move on to further explaining this finding and its implications.

- As noted, recommendations for further research can be included in either the discussion or conclusion of your paper, but do not repeat your recommendations in the both sections. Think about the overall narrative flow of your paper to determine where best to locate this information. However, if your findings raise a lot of new questions or issues, consider including suggestions for further research in the discussion section.

- Do not introduce new results in the discussion section. Be wary of mistaking the reiteration of a specific finding for an interpretation because it may confuse the reader. The description of findings [results section] and the interpretation of their significance [discussion section] should be distinct parts of your paper. If you choose to combine the results section and the discussion section into a single narrative, you must be clear in how you report the information discovered and your own interpretation of each finding. This approach is not recommended if you lack experience writing college-level research papers.

- Use of the first person pronoun is generally acceptable. Using first person singular pronouns can help emphasize a point or illustrate a contrasting finding. However, keep in mind that too much use of the first person can actually distract the reader from the main points [i.e., I know you're telling me this--just tell me!].

Analyzing vs. Summarizing. Department of English Writing Guide. George Mason University; Discussion. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Hess, Dean R. "How to Write an Effective Discussion." Respiratory Care 49 (October 2004); Kretchmer, Paul. Fourteen Steps to Writing to Writing an Effective Discussion Section. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008; The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Sauaia, A. et al. "The Anatomy of an Article: The Discussion Section: "How Does the Article I Read Today Change What I Will Recommend to my Patients Tomorrow?” The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 74 (June 2013): 1599-1602; Research Limitations & Future Research . Lund Research Ltd., 2012; Summary: Using it Wisely. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Schafer, Mickey S. Writing the Discussion. Writing in Psychology course syllabus. University of Florida; Yellin, Linda L. A Sociology Writer's Guide . Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 2009.

Writing Tip

Don’t Over-Interpret the Results!

Interpretation is a subjective exercise. As such, you should always approach the selection and interpretation of your findings introspectively and to think critically about the possibility of judgmental biases unintentionally entering into discussions about the significance of your work. With this in mind, be careful that you do not read more into the findings than can be supported by the evidence you have gathered. Remember that the data are the data: nothing more, nothing less.

MacCoun, Robert J. "Biases in the Interpretation and Use of Research Results." Annual Review of Psychology 49 (February 1998): 259-287; Ward, Paulet al, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Expertise . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Write Two Results Sections!

One of the most common mistakes that you can make when discussing the results of your study is to present a superficial interpretation of the findings that more or less re-states the results section of your paper. Obviously, you must refer to your results when discussing them, but focus on the interpretation of those results and their significance in relation to the research problem, not the data itself.

Azar, Beth. "Discussing Your Findings." American Psychological Association gradPSYCH Magazine (January 2006).

Yet Another Writing Tip

Avoid Unwarranted Speculation!

The discussion section should remain focused on the findings of your study. For example, if the purpose of your research was to measure the impact of foreign aid on increasing access to education among disadvantaged children in Bangladesh, it would not be appropriate to speculate about how your findings might apply to populations in other countries without drawing from existing studies to support your claim or if analysis of other countries was not a part of your original research design. If you feel compelled to speculate, do so in the form of describing possible implications or explaining possible impacts. Be certain that you clearly identify your comments as speculation or as a suggestion for where further research is needed. Sometimes your professor will encourage you to expand your discussion of the results in this way, while others don’t care what your opinion is beyond your effort to interpret the data in relation to the research problem.

- << Previous: Using Non-Textual Elements

- Next: Limitations of the Study >>

- Last Updated: May 22, 2024 12:03 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

The discussion section contains the results and outcomes of a study. An effective discussion informs readers what can be learned from your experiment and provides context for the results.

What makes an effective discussion?

When you’re ready to write your discussion, you’ve already introduced the purpose of your study and provided an in-depth description of the methodology. The discussion informs readers about the larger implications of your study based on the results. Highlighting these implications while not overstating the findings can be challenging, especially when you’re submitting to a journal that selects articles based on novelty or potential impact. Regardless of what journal you are submitting to, the discussion section always serves the same purpose: concluding what your study results actually mean.

A successful discussion section puts your findings in context. It should include:

- the results of your research,

- a discussion of related research, and

- a comparison between your results and initial hypothesis.

Tip: Not all journals share the same naming conventions.

You can apply the advice in this article to the conclusion, results or discussion sections of your manuscript.

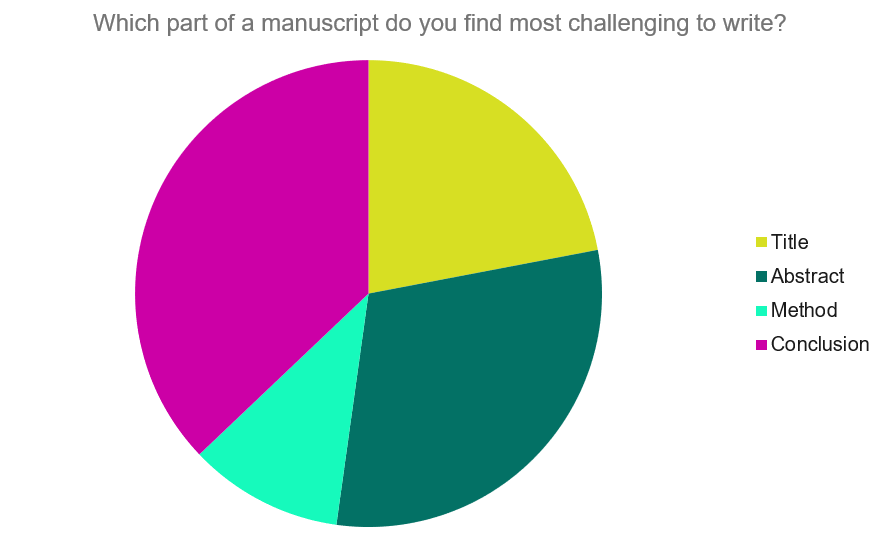

Our Early Career Researcher community tells us that the conclusion is often considered the most difficult aspect of a manuscript to write. To help, this guide provides questions to ask yourself, a basic structure to model your discussion off of and examples from published manuscripts.

Questions to ask yourself:

- Was my hypothesis correct?

- If my hypothesis is partially correct or entirely different, what can be learned from the results?

- How do the conclusions reshape or add onto the existing knowledge in the field? What does previous research say about the topic?

- Why are the results important or relevant to your audience? Do they add further evidence to a scientific consensus or disprove prior studies?

- How can future research build on these observations? What are the key experiments that must be done?

- What is the “take-home” message you want your reader to leave with?

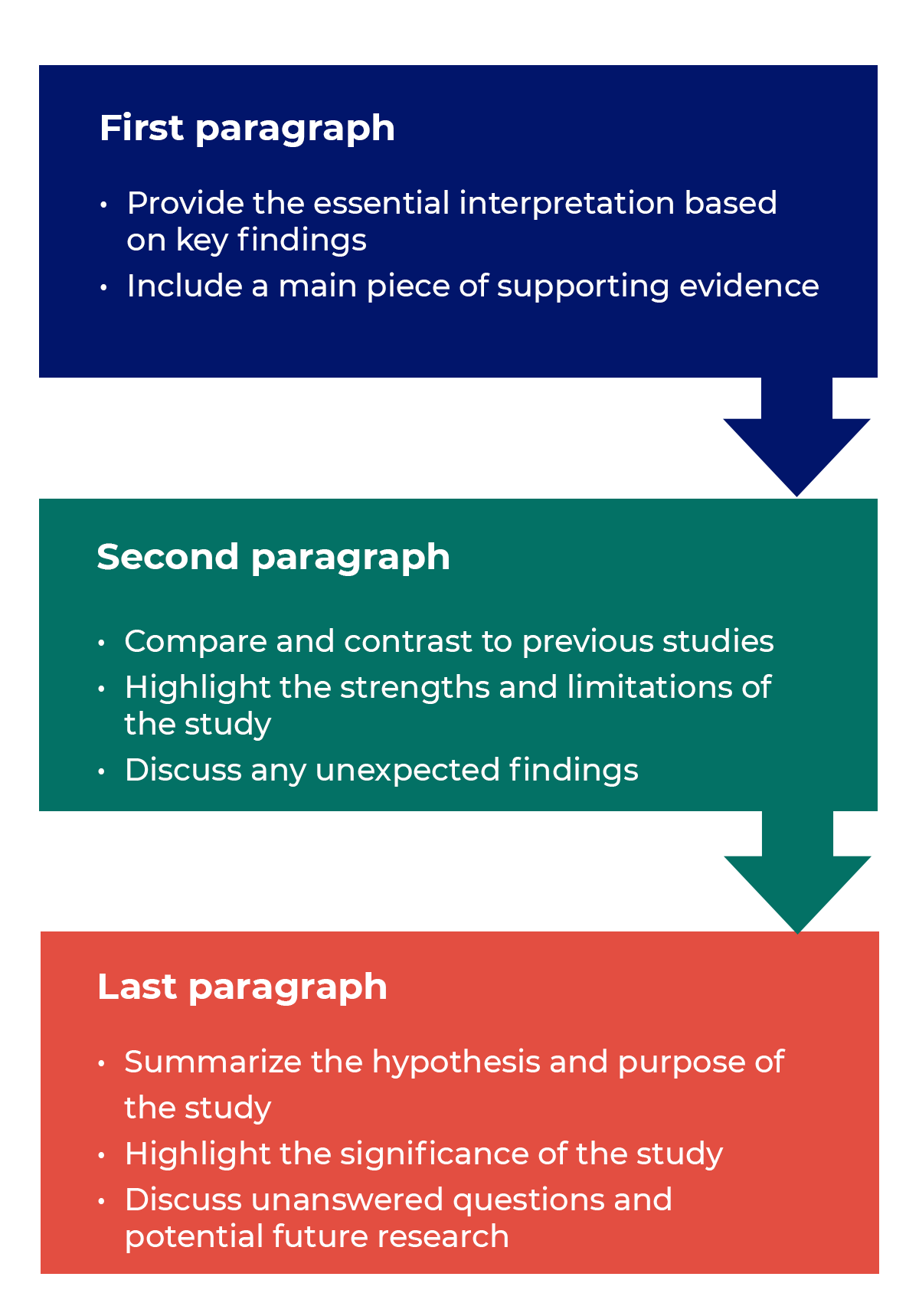

How to structure a discussion

Trying to fit a complete discussion into a single paragraph can add unnecessary stress to the writing process. If possible, you’ll want to give yourself two or three paragraphs to give the reader a comprehensive understanding of your study as a whole. Here’s one way to structure an effective discussion:

Writing Tips

While the above sections can help you brainstorm and structure your discussion, there are many common mistakes that writers revert to when having difficulties with their paper. Writing a discussion can be a delicate balance between summarizing your results, providing proper context for your research and avoiding introducing new information. Remember that your paper should be both confident and honest about the results!

- Read the journal’s guidelines on the discussion and conclusion sections. If possible, learn about the guidelines before writing the discussion to ensure you’re writing to meet their expectations.

- Begin with a clear statement of the principal findings. This will reinforce the main take-away for the reader and set up the rest of the discussion.

- Explain why the outcomes of your study are important to the reader. Discuss the implications of your findings realistically based on previous literature, highlighting both the strengths and limitations of the research.

- State whether the results prove or disprove your hypothesis. If your hypothesis was disproved, what might be the reasons?

- Introduce new or expanded ways to think about the research question. Indicate what next steps can be taken to further pursue any unresolved questions.

- If dealing with a contemporary or ongoing problem, such as climate change, discuss possible consequences if the problem is avoided.

- Be concise. Adding unnecessary detail can distract from the main findings.

Don’t

- Rewrite your abstract. Statements with “we investigated” or “we studied” generally do not belong in the discussion.

- Include new arguments or evidence not previously discussed. Necessary information and evidence should be introduced in the main body of the paper.

- Apologize. Even if your research contains significant limitations, don’t undermine your authority by including statements that doubt your methodology or execution.

- Shy away from speaking on limitations or negative results. Including limitations and negative results will give readers a complete understanding of the presented research. Potential limitations include sources of potential bias, threats to internal or external validity, barriers to implementing an intervention and other issues inherent to the study design.

- Overstate the importance of your findings. Making grand statements about how a study will fully resolve large questions can lead readers to doubt the success of the research.

Snippets of Effective Discussions:

Consumer-based actions to reduce plastic pollution in rivers: A multi-criteria decision analysis approach

Identifying reliable indicators of fitness in polar bears

- How to Write a Great Title

- How to Write an Abstract

- How to Write Your Methods

- How to Report Statistics

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write a Discussion Section for a Research Paper

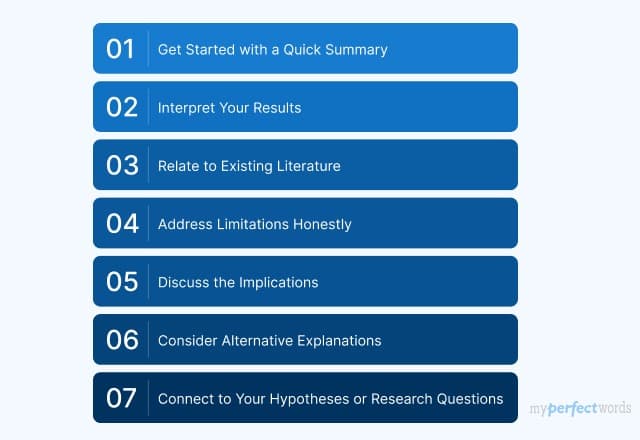

We’ve talked about several useful writing tips that authors should consider while drafting or editing their research papers. In particular, we’ve focused on figures and legends , as well as the Introduction , Methods , and Results . Now that we’ve addressed the more technical portions of your journal manuscript, let’s turn to the analytical segments of your research article. In this article, we’ll provide tips on how to write a strong Discussion section that best portrays the significance of your research contributions.

What is the Discussion section of a research paper?

In a nutshell, your Discussion fulfills the promise you made to readers in your Introduction . At the beginning of your paper, you tell us why we should care about your research. You then guide us through a series of intricate images and graphs that capture all the relevant data you collected during your research. We may be dazzled and impressed at first, but none of that matters if you deliver an anti-climactic conclusion in the Discussion section!

Are you feeling pressured? Don’t worry. To be honest, you will edit the Discussion section of your manuscript numerous times. After all, in as little as one to two paragraphs ( Nature ‘s suggestion based on their 3,000-word main body text limit), you have to explain how your research moves us from point A (issues you raise in the Introduction) to point B (our new understanding of these matters). You must also recommend how we might get to point C (i.e., identify what you think is the next direction for research in this field). That’s a lot to say in two paragraphs!

So, how do you do that? Let’s take a closer look.

What should I include in the Discussion section?

As we stated above, the goal of your Discussion section is to answer the questions you raise in your Introduction by using the results you collected during your research . The content you include in the Discussions segment should include the following information:

- Remind us why we should be interested in this research project.

- Describe the nature of the knowledge gap you were trying to fill using the results of your study.

- Don’t repeat your Introduction. Instead, focus on why this particular study was needed to fill the gap you noticed and why that gap needed filling in the first place.

- Mainly, you want to remind us of how your research will increase our knowledge base and inspire others to conduct further research.

- Clearly tell us what that piece of missing knowledge was.

- Answer each of the questions you asked in your Introduction and explain how your results support those conclusions.

- Make sure to factor in all results relevant to the questions (even if those results were not statistically significant).

- Focus on the significance of the most noteworthy results.

- If conflicting inferences can be drawn from your results, evaluate the merits of all of them.

- Don’t rehash what you said earlier in the Results section. Rather, discuss your findings in the context of answering your hypothesis. Instead of making statements like “[The first result] was this…,” say, “[The first result] suggests [conclusion].”

- Do your conclusions line up with existing literature?

- Discuss whether your findings agree with current knowledge and expectations.

- Keep in mind good persuasive argument skills, such as explaining the strengths of your arguments and highlighting the weaknesses of contrary opinions.

- If you discovered something unexpected, offer reasons. If your conclusions aren’t aligned with current literature, explain.

- Address any limitations of your study and how relevant they are to interpreting your results and validating your findings.

- Make sure to acknowledge any weaknesses in your conclusions and suggest room for further research concerning that aspect of your analysis.

- Make sure your suggestions aren’t ones that should have been conducted during your research! Doing so might raise questions about your initial research design and protocols.

- Similarly, maintain a critical but unapologetic tone. You want to instill confidence in your readers that you have thoroughly examined your results and have objectively assessed them in a way that would benefit the scientific community’s desire to expand our knowledge base.

- Recommend next steps.

- Your suggestions should inspire other researchers to conduct follow-up studies to build upon the knowledge you have shared with them.

- Keep the list short (no more than two).

How to Write the Discussion Section

The above list of what to include in the Discussion section gives an overall idea of what you need to focus on throughout the section. Below are some tips and general suggestions about the technical aspects of writing and organization that you might find useful as you draft or revise the contents we’ve outlined above.

Technical writing elements

- Embrace active voice because it eliminates the awkward phrasing and wordiness that accompanies passive voice.

- Use the present tense, which should also be employed in the Introduction.

- Sprinkle with first person pronouns if needed, but generally, avoid it. We want to focus on your findings.

- Maintain an objective and analytical tone.

Discussion section organization

- Keep the same flow across the Results, Methods, and Discussion sections.

- We develop a rhythm as we read and parallel structures facilitate our comprehension. When you organize information the same way in each of these related parts of your journal manuscript, we can quickly see how a certain result was interpreted and quickly verify the particular methods used to produce that result.

- Notice how using parallel structure will eliminate extra narration in the Discussion part since we can anticipate the flow of your ideas based on what we read in the Results segment. Reducing wordiness is important when you only have a few paragraphs to devote to the Discussion section!

- Within each subpart of a Discussion, the information should flow as follows: (A) conclusion first, (B) relevant results and how they relate to that conclusion and (C) relevant literature.

- End with a concise summary explaining the big-picture impact of your study on our understanding of the subject matter. At the beginning of your Discussion section, you stated why this particular study was needed to fill the gap you noticed and why that gap needed filling in the first place. Now, it is time to end with “how your research filled that gap.”

Discussion Part 1: Summarizing Key Findings

Begin the Discussion section by restating your statement of the problem and briefly summarizing the major results. Do not simply repeat your findings. Rather, try to create a concise statement of the main results that directly answer the central research question that you stated in the Introduction section . This content should not be longer than one paragraph in length.

Many researchers struggle with understanding the precise differences between a Discussion section and a Results section . The most important thing to remember here is that your Discussion section should subjectively evaluate the findings presented in the Results section, and in relatively the same order. Keep these sections distinct by making sure that you do not repeat the findings without providing an interpretation.

Phrase examples: Summarizing the results

- The findings indicate that …

- These results suggest a correlation between A and B …

- The data present here suggest that …

- An interpretation of the findings reveals a connection between…

Discussion Part 2: Interpreting the Findings

What do the results mean? It may seem obvious to you, but simply looking at the figures in the Results section will not necessarily convey to readers the importance of the findings in answering your research questions.

The exact structure of interpretations depends on the type of research being conducted. Here are some common approaches to interpreting data:

- Identifying correlations and relationships in the findings

- Explaining whether the results confirm or undermine your research hypothesis

- Giving the findings context within the history of similar research studies

- Discussing unexpected results and analyzing their significance to your study or general research

- Offering alternative explanations and arguing for your position

Organize the Discussion section around key arguments, themes, hypotheses, or research questions or problems. Again, make sure to follow the same order as you did in the Results section.

Discussion Part 3: Discussing the Implications

In addition to providing your own interpretations, show how your results fit into the wider scholarly literature you surveyed in the literature review section. This section is called the implications of the study . Show where and how these results fit into existing knowledge, what additional insights they contribute, and any possible consequences that might arise from this knowledge, both in the specific research topic and in the wider scientific domain.

Questions to ask yourself when dealing with potential implications:

- Do your findings fall in line with existing theories, or do they challenge these theories or findings? What new information do they contribute to the literature, if any? How exactly do these findings impact or conflict with existing theories or models?

- What are the practical implications on actual subjects or demographics?

- What are the methodological implications for similar studies conducted either in the past or future?

Your purpose in giving the implications is to spell out exactly what your study has contributed and why researchers and other readers should be interested.

Phrase examples: Discussing the implications of the research

- These results confirm the existing evidence in X studies…

- The results are not in line with the foregoing theory that…

- This experiment provides new insights into the connection between…

- These findings present a more nuanced understanding of…

- While previous studies have focused on X, these results demonstrate that Y.

Step 4: Acknowledging the limitations

All research has study limitations of one sort or another. Acknowledging limitations in methodology or approach helps strengthen your credibility as a researcher. Study limitations are not simply a list of mistakes made in the study. Rather, limitations help provide a more detailed picture of what can or cannot be concluded from your findings. In essence, they help temper and qualify the study implications you listed previously.

Study limitations can relate to research design, specific methodological or material choices, or unexpected issues that emerged while you conducted the research. Mention only those limitations directly relate to your research questions, and explain what impact these limitations had on how your study was conducted and the validity of any interpretations.

Possible types of study limitations:

- Insufficient sample size for statistical measurements

- Lack of previous research studies on the topic

- Methods/instruments/techniques used to collect the data

- Limited access to data

- Time constraints in properly preparing and executing the study

After discussing the study limitations, you can also stress that your results are still valid. Give some specific reasons why the limitations do not necessarily handicap your study or narrow its scope.

Phrase examples: Limitations sentence beginners

- “There may be some possible limitations in this study.”

- “The findings of this study have to be seen in light of some limitations.”

- “The first limitation is the…The second limitation concerns the…”

- “The empirical results reported herein should be considered in the light of some limitations.”

- “This research, however, is subject to several limitations.”

- “The primary limitation to the generalization of these results is…”

- “Nonetheless, these results must be interpreted with caution and a number of limitations should be borne in mind.”

Discussion Part 5: Giving Recommendations for Further Research

Based on your interpretation and discussion of the findings, your recommendations can include practical changes to the study or specific further research to be conducted to clarify the research questions. Recommendations are often listed in a separate Conclusion section , but often this is just the final paragraph of the Discussion section.

Suggestions for further research often stem directly from the limitations outlined. Rather than simply stating that “further research should be conducted,” provide concrete specifics for how future can help answer questions that your research could not.

Phrase examples: Recommendation sentence beginners

- Further research is needed to establish …

- There is abundant space for further progress in analyzing…

- A further study with more focus on X should be done to investigate…

- Further studies of X that account for these variables must be undertaken.

Consider Receiving Professional Language Editing

As you edit or draft your research manuscript, we hope that you implement these guidelines to produce a more effective Discussion section. And after completing your draft, don’t forget to submit your work to a professional proofreading and English editing service like Wordvice, including our manuscript editing service for paper editing , cover letter editing , SOP editing , and personal statement proofreading services. Language editors not only proofread and correct errors in grammar, punctuation, mechanics, and formatting but also improve terms and revise phrases so they read more naturally. Wordvice is an industry leader in providing high-quality revision for all types of academic documents.

For additional information about how to write a strong research paper, make sure to check out our full research writing series !

Wordvice Writing Resources

- How to Write a Research Paper Introduction

- Which Verb Tenses to Use in a Research Paper

- How to Write an Abstract for a Research Paper

- How to Write a Research Paper Title

- Useful Phrases for Academic Writing

- Common Transition Terms in Academic Papers

- Active and Passive Voice in Research Papers

- 100+ Verbs That Will Make Your Research Writing Amazing

- Tips for Paraphrasing in Research Papers

Additional Academic Resources

- Guide for Authors. (Elsevier)

- How to Write the Results Section of a Research Paper. (Bates College)

- Structure of a Research Paper. (University of Minnesota Biomedical Library)

- How to Choose a Target Journal (Springer)

- How to Write Figures and Tables (UNC Writing Center)

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Turk J Urol

- v.39(Suppl 1); 2013 Sep

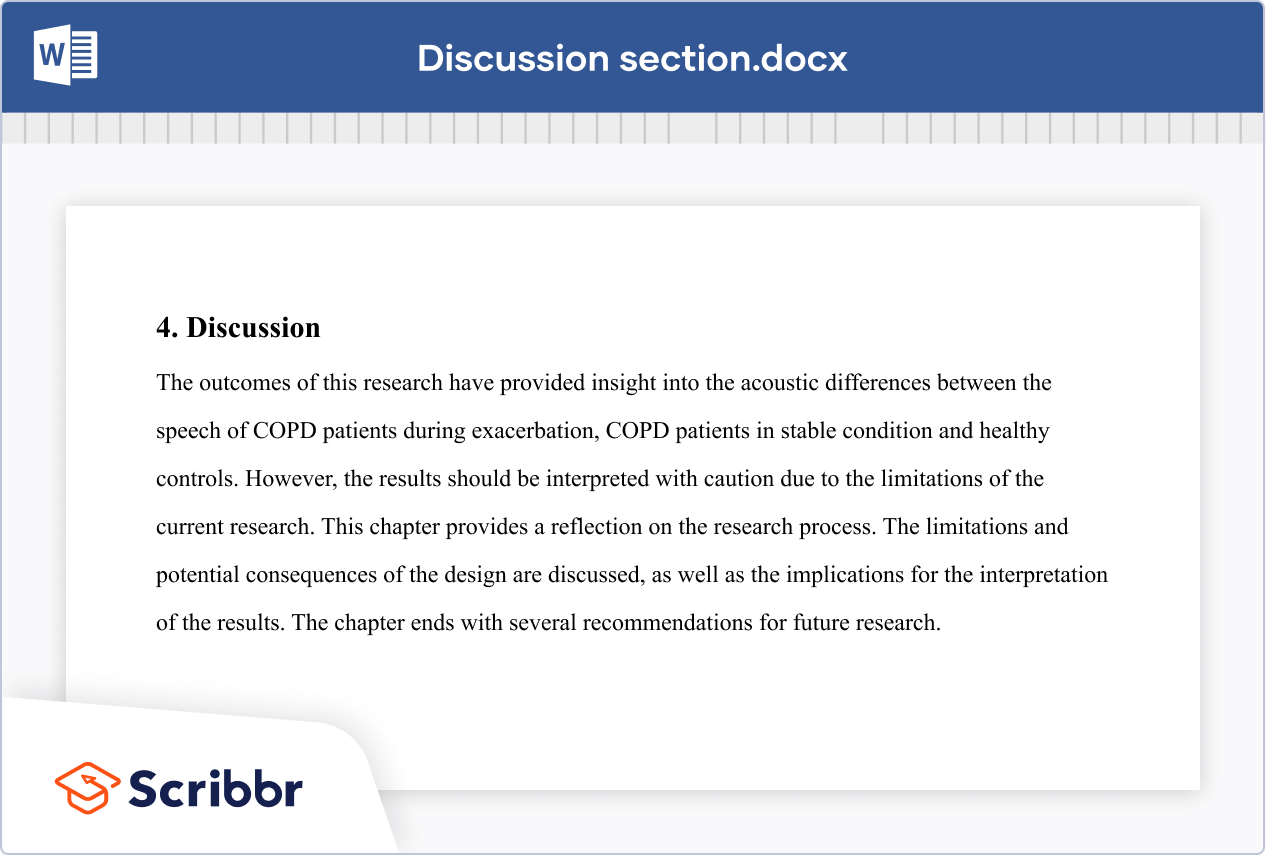

How to write a discussion section?

Writing manuscripts to describe study outcomes, although not easy, is the main task of an academician. The aim of the present review is to outline the main aspects of writing the discussion section of a manuscript. Additionally, we address various issues regarding manuscripts in general. It is advisable to work on a manuscript regularly to avoid losing familiarity with the article. On principle, simple, clear and effective language should be used throughout the text. In addition, a pre-peer review process is recommended to obtain feedback on the manuscript. The discussion section can be written in 3 parts: an introductory paragraph, intermediate paragraphs and a conclusion paragraph. For intermediate paragraphs, a “divide and conquer” approach, meaning a full paragraph describing each of the study endpoints, can be used. In conclusion, academic writing is similar to other skills, and practice makes perfect.

Introduction

Sharing knowledge produced during academic life is achieved through writing manuscripts. However writing manuscripts is a challenging endeavour in that we physicians have a heavy workload, and English which is common language used for the dissemination of scientific knowledge is not our mother tongue.

The objective of this review is to summarize the method of writing ‘Discussion’ section which is the most important, but probably at the same time the most unlikable part of a manuscript, and demonstrate the easy ways we applied in our practice, and finally share the frequently made relevant mistakes. During this procedure, inevitably some issues which concerns general concept of manuscript writing process are dealt with. Therefore in this review we will deal with topics related to the general aspects of manuscript writing process, and specifically issues concerning only the ‘Discussion’ section.

A) Approaches to general aspects of manuscript writing process:

1. what should be the strategy of sparing time for manuscript writing be.

Two different approaches can be formulated on this issue? One of them is to allocate at least 30 minutes a day for writing a manuscript which amounts to 3.5 hours a week. This period of time is adequate for completion of a manuscript within a few weeks which can be generally considered as a long time interval. Fundamental advantage of this approach is to gain a habit of making academic researches if one complies with the designated time schedule, and to keep the manuscript writing motivation at persistently high levels. Another approach concerning this issue is to accomplish manuscript writing process within a week. With the latter approach, the target is rapidly attained. However longer time periods spent in order to concentrate on the subject matter can be boring, and lead to loss of motivation. Daily working requirements unrelated to the manuscript writing might intervene, and prolong manuscript writing process. Alienation periods can cause loss of time because of need for recurrent literature reviews. The most optimal approach to manuscript writing process is daily writing strategy where higher levels of motivation are persistently maintained.

Especially before writing the manuscript, the most important step at the start is to construct a draft, and completion of the manuscript on a theoretical basis. Therefore, during construction of a draft, attention distracting environment should be avoided, and this step should be completed within 1–2 hours. On the other hand, manuscript writing process should begin before the completion of the study (even the during project stage). The justification of this approach is to see the missing aspects of the study and the manuscript writing methodology, and try to solve the relevant problems before completion of the study. Generally, after completion of the study, it is very difficult to solve the problems which might be discerned during the writing process. Herein, at least drafts of the ‘Introduction’, and ‘Material and Methods’ can be written, and even tables containing numerical data can be constructed. These tables can be written down in the ‘Results’ section. [ 1 ]

2. How should the manuscript be written?

The most important principle to be remembered on this issue is to obey the criteria of simplicity, clarity, and effectiveness. [ 2 ] Herein, do not forget that, the objective should be to share our findings with the readers in an easily comprehensible format. Our approach on this subject is to write all structured parts of the manuscript at the same time, and start writing the manuscript while reading the first literature. Thus newly arisen connotations, and self-brain gyms will be promptly written down. However during this process your outcomes should be revealed fully, and roughly the message of the manuscript which be delivered. Thus with this so-called ‘hunter’s approach’ the target can be achieved directly, and rapidly. Another approach is ‘collectioner’s approach. [ 3 ] In this approach, firstly, potential data, and literature studies are gathered, read, and then selected ones are used. Since this approach suits with surgical point of view, probably ‘hunter’s approach’ serves our purposes more appropriately. However, in parallel with academic development, our novice colleague ‘manuscripters’ can prefer ‘collectioner’s approach.’

On the other hand, we think that research team consisting of different age groups has some advantages. Indeed young colleagues have the enthusiasm, and energy required for the conduction of the study, while middle-aged researchers have the knowledge to manage the research, and manuscript writing. Experienced researchers make guiding contributions to the manuscript. However working together in harmony requires assignment of a chief researcher, and periodically organizing advancement meetings. Besides, talents, skills, and experiences of the researchers in different fields (ie. research methods, contact with patients, preparation of a project, fund-raising, statistical analysis etc.) will determine task sharing, and make a favourable contribution to the perfection of the manuscript. Achievement of the shared duties within a predetermined time frame will sustain the motivation of the researchers, and prevent wearing out of updated data.

According to our point of view, ‘Abstract’ section of the manuscript should be written after completion of the manuscript. The reason for this is that during writing process of the main text, the significant study outcomes might become insignificant or vice versa. However, generally, before onset of the writing process of the manuscript, its abstract might be already presented in various congresses. During writing process, this abstract might be a useful guide which prevents deviation from the main objective of the manuscript.

On the other hand references should be promptly put in place while writing the manuscript, Sorting, and placement of the references should not be left to the last moment. Indeed, it might be very difficult to remember relevant references to be placed in the ‘Discussion’ section. For the placement of references use of software programs detailed in other sections is a rational approach.

3. Which target journal should be selected?

In essence, the methodology to be followed in writing the ‘Discussion’ section is directly related to the selection of the target journal. Indeed, in compliance with the writing rules of the target journal, limitations made on the number of words after onset of the writing process, effects mostly the ‘Discussion’ section. Proper matching of the manuscript with the appropriate journal requires clear, and complete comprehension of the available data from scientific point of view. Previously, similar articles might have been published, however innovative messages, and new perspectives on the relevant subject will facilitate acceptance of the article for publication. Nowadays, articles questioning available information, rather than confirmatory ones attract attention. However during this process, classical information should not be questioned except for special circumstances. For example manuscripts which lead to the conclusions as “laparoscopic surgery is more painful than open surgery” or “laparoscopic surgery can be performed without prior training” will not be accepted or they will be returned by the editor of the target journal to the authors with the request of critical review. Besides the target journal to be selected should be ready to accept articles with similar concept. In fact editors of the journal will not reserve the limited space in their journal for articles yielding similar conclusions.

The title of the manuscript is as important as the structured sections * of the manuscript. The title can be the most striking or the newest outcome among results obtained.

Before writing down the manuscript, determination of 2–3 titles increases the motivation of the authors towards the manuscript. During writing process of the manuscript one of these can be selected based on the intensity of the discussion. However the suitability of the title to the agenda of the target journal should be investigated beforehand. For example an article bearing the title “Use of barbed sutures in laparoscopic partial nephrectomy shortens warm ischemia time” should not be sent to “Original Investigations and Seminars in Urologic Oncology” Indeed the topic of the manuscript is out of the agenda of this journal.

4. Do we have to get a pre-peer review about the written manuscript?

Before submission of the manuscript to the target journal the opinions of internal, and external referees should be taken. [ 1 ] Internal referees can be considered in 2 categories as “General internal referees” and “expert internal referees” General internal referees (ie. our colleagues from other medical disciplines) are not directly concerned with your subject matter but as mentioned above they critically review the manuscript as for simplicity, clarity, and effectiveness of its writing style. Expert internal reviewers have a profound knowledge about the subject, and they can provide guidance about the writing process of the manuscript (ie. our senior colleagues more experienced than us). External referees are our colleagues who did not contribute to data collection of our study in any way, but we can request their opinions about the subject matter of the manuscript. Since they are unrelated both to the author(s), and subject matter of the manuscript, these referees can review our manuscript more objectively. Before sending the manuscript to internal, and external referees, we should contact with them, and ask them if they have time to review our manuscript. We should also give information about our subject matter. Otherwise pre-peer review process can delay publication of the manuscript, and decrease motivation of the authors. In conclusion, whoever the preferred referee will be, these internal, and external referees should respond the following questions objectively. 1) Does the manuscript contribute to the literature?; 2) Does it persuasive? 3) Is it suitable for the publication in the selected journal? 4) Has a simple, clear, and effective language been used throughout the manuscript? In line with the opinions of the referees, the manuscript can be critically reviewed, and perfected. [ 1 ]**

Following receival of the opinions of internal, and external referees, one should concentrate priorly on indicated problems, and their solutions. Comments coming from the reviewers should be criticized, but a defensive attitude should not be assumed during this evaluation process. During this “incubation” period where the comments of the internal, and external referees are awaited, literature should be reviewed once more. Indeed during this time interval a new article which you should consider in the ‘Discussion’ section can be cited in the literature.

5. What are the common mistakes made related to the writing process of a manuscript?

Probably the most important mistakes made related to the writing process of a manuscript include lack of a clear message of the manuscript , inclusion of more than one main idea in the same text or provision of numerous unrelated results at the same time so as to reinforce the assertions of the manuscript. This approach can be termed roughly as “loss of the focus of the study” In conclusion, the author(s) should ask themselves the following question at every stage of the writing process:. “What is the objective of the study? If you always get clear-cut answers whenever you ask this question, then the study is proceeding towards the right direction. Besides application of a template which contains the intended clear-cut messages to be followed will contribute to the communication of net messages.

One of the important mistakes is refraining from critical review of the manuscript as a whole after completion of the writing process. Therefore, the authors should go over the manuscript for at least three times after finalization of the manuscript based on joint decision. The first control should concentrate on the evaluation of the appropriateness of the logic of the manuscript, and its organization, and whether desired messages have been delivered or not. Secondly, syutax, and grammar of the manuscript should be controlled. It is appropriate to review the manuscript for the third time 1 or 2 weeks after completion of its writing process. Thus, evaluation of the “cooled” manuscript will be made from a more objective perspective, and assessment process of its integrity will be facilitated.

Other erroneous issues consist of superfluousness of the manuscript with unnecessary repetitions, undue, and recurrent references to the problems adressed in the manuscript or their solution methods, overcriticizing or overpraising other studies, and use of a pompous literary language overlooking the main objective of sharing information. [ 4 ]

B) Approaches to the writing process of the ‘Discussion’ section:

1. how should the main points of ‘discussion’ section be constructed.

Generally the length of the ‘Discussion ‘ section should not exceed the sum of other sections (ıntroduction, material and methods, and results), and it should be completed within 6–7 paragraphs.. Each paragraph should not contain more than 200 words, and hence words should be counted repeteadly. The ‘Discussion’ section can be generally divided into 3 separate paragraphs as. 1) Introductory paragraph, 2) Intermediate paragraphs, 3) Concluding paragraph.

The introductory paragraph contains the main idea of performing the study in question. Without repeating ‘Introduction’ section of the manuscript, the problem to be addressed, and its updateness are analysed. The introductory paragraph starts with an undebatable sentence, and proceeds with a part addressing the following questions as 1) On what issue we have to concentrate, discuss or elaborate? 2) What solutions can be recommended to solve this problem? 3) What will be the new, different, and innovative issue? 4) How will our study contribute to the solution of this problem An introductory paragraph in this format is helpful to accomodate reader to the rest of the Discussion section. However summarizing the basic findings of the experimental studies in the first paragraph is generally recommended by the editors of the journal. [ 5 ]

In the last paragraph of the Discussion section “strong points” of the study should be mentioned using “constrained”, and “not too strongly assertive” statements. Indicating limitations of the study will reflect objectivity of the authors, and provide answers to the questions which will be directed by the reviewers of the journal. On the other hand in the last paragraph, future directions or potential clinical applications may be emphasized.

2. How should the intermediate paragraphs of the Discussion section be formulated?

The reader passes through a test of boredom while reading paragraphs of the Discussion section apart from the introductory, and the last paragraphs. Herein your findings rather than those of the other researchers are discussed. The previous studies can be an explanation or reinforcement of your findings. Each paragraph should contain opinions in favour or against the topic discussed, critical evaluations, and learning points.

Our management approach for intermediate paragraphs is “divide and conquer” tactics. Accordingly, the findings of the study are determined in order of their importance, and a paragraph is constructed for each finding ( Figure 1 ). Each paragraph begins with an “indisputable” introductory sentence about the topic to be discussed. This sentence basically can be the answer to the question “What have we found?” Then a sentence associated with the subject matter to be discussed is written. Subsequently, in the light of the current literature this finding is discussed, new ideas on this subject are revealed, and the paragraph ends with a concluding remark.

Divide and Conquer tactics

In this paragraph, main topic should be emphasized without going into much detail. Its place, and importance among other studies should be indicated. However during this procedure studies should be presented in a logical sequence (ie. from past to present, from a few to many cases), and aspects of the study contradictory to other studies should be underlined. Results without any supportive evidence or equivocal results should not be written. Besides numerical values presented in the Results section should not be repeated unless required.

Besides, asking the following questions, and searching their answers in the same paragraph will facilitate writing process of the paragraph. [ 1 ] 1) Can the discussed result be false or inadequate? 2) Why is it false? (inadequate blinding, protocol contamination, lost to follow-up, lower statistical power of the study etc.), 3) What meaning does this outcome convey?

3. What are the common mistakes made in writing the Discussion section?:

Probably the most important mistake made while writing the Discussion section is the need for mentioning all literature references. One point to remember is that we are not writing a review article, and only the results related to this paragraph should be discussed. Meanwhile, each word of the paragraphs should be counted, and placed carefully. Each word whose removal will not change the meaning should be taken out from the text.” Writing a saga with “word salads” *** is one of the reasons for prompt rejection. Indeed, if the reviewer thinks that it is difficult to correct the Discussion section, he/she use her/ his vote in the direction of rejection to save time (Uniform requirements for manuscripts: International Comittee of Medical Journal Editors [ http://www.icmje.org/urm_full.pdf ])

The other important mistake is to give too much references, and irrelevancy between the references, and the section with these cited references. [ 3 ] While referring these studies, (excl. introductory sentences linking indisputable sentences or paragraphs) original articles should be cited. Abstracts should not be referred, and review articles should not be cited unless required very much.

4. What points should be paid attention about writing rules, and grammar?

As is the case with the whole article, text of the Discussion section should be written with a simple language, as if we are talking with our colleague. [ 2 ] Each sentence should indicate a single point, and it should not exceed 25–30 words. The priorly mentioned information which linked the previous sentence should be placed at the beginning of the sentence, while the new information should be located at the end of the sentence. During construction of the sentences, avoid unnecessary words, and active voice rather than passive voice should be used.**** Since conventionally passive voice is used in the scientific manuscripts written in the Turkish language, the above statement contradicts our writing habits. However, one should not refrain from beginning the sentences with the word “we”. Indeed, editors of the journal recommend use of active voice so as to increase the intelligibility of the manuscript.

In conclusion, the major point to remember is that the manuscript should be written complying with principles of simplicity, clarity, and effectiveness. In the light of these principles, as is the case in our daily practice, all components of the manuscript (IMRAD) can be written concurrently. In the ‘Discussion’ section ‘divide and conquer’ tactics remarkably facilitates writing process of the discussion. On the other hand, relevant or irrelevant feedbacks received from our colleagues can contribute to the perfection of the manuscript. Do not forget that none of the manuscripts is perfect, and one should not refrain from writing because of language problems, and related lack of experience.

Instead of structured sections of a manuscript (IMRAD): Introduction, Material and Methods, Results, and Discussion

Instead of in the Istanbul University Faculty of Medicine posters to be submitted in congresses are time to time discussed in Wednesday meetings, and opinions of the internal referees are obtained about the weak, and strong points of the study

Instead of a writing style which uses words or sentences with a weak logical meaning that do not lead the reader to any conclusion

Instead of “white color”; “proven”; nstead of “history”; “to”. should be used instead of “white in color”, “definitely proven”, “past history”, and “in order to”, respectively ( ref. 2 )

Instead of “No instances of either postoperative death or major complications occurred during the early post-operative period” use “There were no deaths or major complications occurred during the early post-operative period.

Instead of “Measurements were performed to evaluate the levels of CEA in the serum” use “We measured serum CEA levels”

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

General Research Paper Guidelines: Discussion

Discussion section.

The overall purpose of a research paper’s discussion section is to evaluate and interpret results, while explaining both the implications and limitations of your findings. Per APA (2020) guidelines, this section requires you to “examine, interpret, and qualify the results and draw inferences and conclusions from them” (p. 89). Discussion sections also require you to detail any new insights, think through areas for future research, highlight the work that still needs to be done to further your topic, and provide a clear conclusion to your research paper. In a good discussion section, you should do the following:

- Clearly connect the discussion of your results to your introduction, including your central argument, thesis, or problem statement.

- Provide readers with a critical thinking through of your results, answering the “so what?” question about each of your findings. In other words, why is this finding important?

- Detail how your research findings might address critical gaps or problems in your field

- Compare your results to similar studies’ findings

- Provide the possibility of alternative interpretations, as your goal as a researcher is to “discover” and “examine” and not to “prove” or “disprove.” Instead of trying to fit your results into your hypothesis, critically engage with alternative interpretations to your results.

For more specific details on your Discussion section, be sure to review Sections 3.8 (pp. 89-90) and 3.16 (pp. 103-104) of your 7 th edition APA manual

*Box content adapted from:

University of Southern California (n.d.). Organizing your social sciences research paper: 8 the discussion . https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/discussion

Limitations

Limitations of generalizability or utility of findings, often over which the researcher has no control, should be detailed in your Discussion section. Including limitations for your reader allows you to demonstrate you have thought critically about your given topic, understood relevant literature addressing your topic, and chosen the methodology most appropriate for your research. It also allows you an opportunity to suggest avenues for future research on your topic. An effective limitations section will include the following:

- Detail (a) sources of potential bias, (b) possible imprecision of measures, (c) other limitations or weaknesses of the study, including any methodological or researcher limitations.

- Sample size: In quantitative research, if a sample size is too small, it is more difficult to generalize results.

- Lack of available/reliable data : In some cases, data might not be available or reliable, which will ultimately affect the overall scope of your research. Use this as an opportunity to explain areas for future study.

- Lack of prior research on your study topic: In some cases, you might find that there is very little or no similar research on your study topic, which hinders the credibility and scope of your own research. If this is the case, use this limitation as an opportunity to call for future research. However, make sure you have done a thorough search of the available literature before making this claim.

- Flaws in measurement of data: Hindsight is 20/20, and you might realize after you have completed your research that the data tool you used actually limited the scope or results of your study in some way. Again, acknowledge the weakness and use it as an opportunity to highlight areas for future study.

- Limits of self-reported data: In your research, you are assuming that any participants will be honest and forthcoming with responses or information they provide to you. Simply acknowledging this assumption as a possible limitation is important in your research.

- Access: Most research requires that you have access to people, documents, organizations, etc.. However, for various reasons, access is sometimes limited or denied altogether. If this is the case, you will want to acknowledge access as a limitation to your research.

- Time: Choosing a research focus that is narrow enough in scope to finish in a given time period is important. If such limitations of time prevent you from certain forms of research, access, or study designs, acknowledging this time restraint is important. Acknowledging such limitations is important, as they can point other researchers to areas that require future study.

- Potential Bias: All researchers have some biases, so when reading and revising your draft, pay special attention to the possibilities for bias in your own work. Such bias could be in the form you organized people, places, participants, or events. They might also exist in the method you selected or the interpretation of your results. Acknowledging such bias is an important part of the research process.

- Language Fluency: On occasion, researchers or research participants might have language fluency issues, which could potentially hinder results or how effectively you interpret results. If this is an issue in your research, make sure to acknowledge it in your limitations section.

University of Southern California (n.d.). Organizing your social sciences research paper: Limitations of the study . https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/limitations

In many research papers, the conclusion, like the limitations section, is folded into the larger discussion section. If you are unsure whether to include the conclusion as part of your discussion or as a separate section, be sure to defer to the assignment instructions or ask your instructor.

The conclusion is important, as it is specifically designed to highlight your research’s larger importance outside of the specific results of your study. Your conclusion section allows you to reiterate the main findings of your study, highlight their importance, and point out areas for future research. Based on the scope of your paper, your conclusion could be anywhere from one to three paragraphs long. An effective conclusion section should include the following:

- Describe the possibilities for continued research on your topic, including what might be improved, adapted, or added to ensure useful and informed future research.

- Provide a detailed account of the importance of your findings

- Reiterate why your problem is important, detail how your interpretation of results impacts the subfield of study, and what larger issues both within and outside of your field might be affected from such results

University of Southern California (n.d.). Organizing your social sciences research paper: 9. the conclusion . https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/conclusion

- Previous Page: Results

- Next Page: References

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Organizing Academic Research Papers: 8. The Discussion

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Executive Summary

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tertiary Sources

- What Is Scholarly vs. Popular?

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Annotated Bibliography

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- How to Manage Group Projects

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Essays

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Acknowledgements

The purpose of the discussion is to interpret and describe the significance of your findings in light of what was already known about the research problem being investigated, and to explain any new understanding or fresh insights about the problem after you've taken the findings into consideration. The discussion will always connect to the introduction by way of the research questions or hypotheses you posed and the literature you reviewed, but it does not simply repeat or rearrange the introduction; the discussion should always explain how your study has moved the reader's understanding of the research problem forward from where you left them at the end of the introduction.

Importance of a Good Discussion

This section is often considered the most important part of a research paper because it most effectively demonstrates your ability as a researcher to think critically about an issue, to develop creative solutions to problems based on the findings, and to formulate a deeper, more profound understanding of the research problem you are studying.

The discussion section is where you explore the underlying meaning of your research , its possible implications in other areas of study, and the possible improvements that can be made in order to further develop the concerns of your research.

This is the section where you need to present the importance of your study and how it may be able to contribute to and/or fill existing gaps in the field. If appropriate, the discussion section is also where you state how the findings from your study revealed new gaps in the literature that had not been previously exposed or adequately described.

This part of the paper is not strictly governed by objective reporting of information but, rather, it is where you can engage in creative thinking about issues through evidence-based interpretation of findings. This is where you infuse your results with meaning.

Kretchmer, Paul. Fourteen Steps to Writing to Writing an Effective Discussion Section . San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008.

Structure and Writing Style

I. General Rules

These are the general rules you should adopt when composing your discussion of the results :

- Do not be verbose or repetitive.

- Be concise and make your points clearly.

- Avoid using jargon.

- Follow a logical stream of thought.

- Use the present verb tense, especially for established facts; however, refer to specific works and references in the past tense.

- If needed, use subheadings to help organize your presentation or to group your interpretations into themes.

II. The Content

The content of the discussion section of your paper most often includes :

- Explanation of results : comment on whether or not the results were expected and present explanations for the results; go into greater depth when explaining findings that were unexpected or especially profound. If appropriate, note any unusual or unanticipated patterns or trends that emerged from your results and explain their meaning.

- References to previous research : compare your results with the findings from other studies, or use the studies to support a claim. This can include re-visiting key sources already cited in your literature review section, or, save them to cite later in the discussion section if they are more important to compare with your results than being part of the general research you cited to provide context and background information.

- Deduction : a claim for how the results can be applied more generally. For example, describing lessons learned, proposing recommendations that can help improve a situation, or recommending best practices.

- Hypothesis : a more general claim or possible conclusion arising from the results [which may be proved or disproved in subsequent research].

III. Organization and Structure

Keep the following sequential points in mind as you organize and write the discussion section of your paper:

- Think of your discussion as an inverted pyramid. Organize the discussion from the general to the specific, linking your findings to the literature, then to theory, then to practice [if appropriate].

- Use the same key terms, mode of narration, and verb tense [present] that you used when when describing the research problem in the introduction.

- Begin by briefly re-stating the research problem you were investigating and answer all of the research questions underpinning the problem that you posed in the introduction.

- Describe the patterns, principles, and relationships shown by each major findings and place them in proper perspective. The sequencing of providing this information is important; first state the answer, then the relevant results, then cite the work of others. If appropriate, refer the reader to a figure or table to help enhance the interpretation of the data. The order of interpreting each major finding should be in the same order as they were described in your results section.

- A good discussion section includes analysis of any unexpected findings. This paragraph should begin with a description of the unexpected finding, followed by a brief interpretation as to why you believe it appeared and, if necessary, its possible significance in relation to the overall study. If more than one unexpected finding emerged during the study, describe each them in the order they appeared as you gathered the data.