The COVID-19 pandemic has changed education forever. This is how

With schools shut across the world, millions of children have had to adapt to new types of learning. Image: REUTERS/Gonzalo Fuentes

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Cathy Li

Farah lalani.

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Education, Gender and Work is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, education, gender and work.

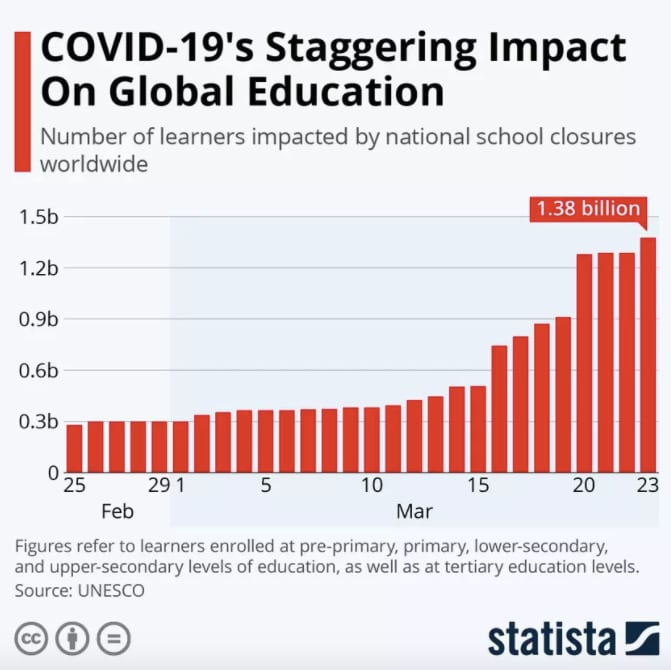

- The COVID-19 has resulted in schools shut all across the world. Globally, over 1.2 billion children are out of the classroom.

- As a result, education has changed dramatically, with the distinctive rise of e-learning, whereby teaching is undertaken remotely and on digital platforms.

- Research suggests that online learning has been shown to increase retention of information, and take less time, meaning the changes coronavirus have caused might be here to stay.

While countries are at different points in their COVID-19 infection rates, worldwide there are currently more than 1.2 billion children in 186 countries affected by school closures due to the pandemic. In Denmark, children up to the age of 11 are returning to nurseries and schools after initially closing on 12 March , but in South Korea students are responding to roll calls from their teachers online .

With this sudden shift away from the classroom in many parts of the globe, some are wondering whether the adoption of online learning will continue to persist post-pandemic, and how such a shift would impact the worldwide education market.

Even before COVID-19, there was already high growth and adoption in education technology, with global edtech investments reaching US$18.66 billion in 2019 and the overall market for online education projected to reach $350 Billion by 2025 . Whether it is language apps , virtual tutoring , video conferencing tools, or online learning software , there has been a significant surge in usage since COVID-19.

How is the education sector responding to COVID-19?

In response to significant demand, many online learning platforms are offering free access to their services, including platforms like BYJU’S , a Bangalore-based educational technology and online tutoring firm founded in 2011, which is now the world’s most highly valued edtech company . Since announcing free live classes on its Think and Learn app, BYJU’s has seen a 200% increase in the number of new students using its product, according to Mrinal Mohit, the company's Chief Operating Officer.

Tencent classroom, meanwhile, has been used extensively since mid-February after the Chinese government instructed a quarter of a billion full-time students to resume their studies through online platforms. This resulted in the largest “online movement” in the history of education with approximately 730,000 , or 81% of K-12 students, attending classes via the Tencent K-12 Online School in Wuhan.

Have you read?

The future of jobs report 2023, how to follow the growth summit 2023.

Other companies are bolstering capabilities to provide a one-stop shop for teachers and students. For example, Lark, a Singapore-based collaboration suite initially developed by ByteDance as an internal tool to meet its own exponential growth, began offering teachers and students unlimited video conferencing time, auto-translation capabilities, real-time co-editing of project work, and smart calendar scheduling, amongst other features. To do so quickly and in a time of crisis, Lark ramped up its global server infrastructure and engineering capabilities to ensure reliable connectivity.

Alibaba’s distance learning solution, DingTalk, had to prepare for a similar influx: “To support large-scale remote work, the platform tapped Alibaba Cloud to deploy more than 100,000 new cloud servers in just two hours last month – setting a new record for rapid capacity expansion,” according to DingTalk CEO, Chen Hang.

Some school districts are forming unique partnerships, like the one between The Los Angeles Unified School District and PBS SoCal/KCET to offer local educational broadcasts, with separate channels focused on different ages, and a range of digital options. Media organizations such as the BBC are also powering virtual learning; Bitesize Daily , launched on 20 April, is offering 14 weeks of curriculum-based learning for kids across the UK with celebrities like Manchester City footballer Sergio Aguero teaching some of the content.

What does this mean for the future of learning?

While some believe that the unplanned and rapid move to online learning – with no training, insufficient bandwidth, and little preparation – will result in a poor user experience that is unconducive to sustained growth, others believe that a new hybrid model of education will emerge, with significant benefits. “I believe that the integration of information technology in education will be further accelerated and that online education will eventually become an integral component of school education,“ says Wang Tao, Vice President of Tencent Cloud and Vice President of Tencent Education.

There have already been successful transitions amongst many universities. For example, Zhejiang University managed to get more than 5,000 courses online just two weeks into the transition using “DingTalk ZJU”. The Imperial College London started offering a course on the science of coronavirus, which is now the most enrolled class launched in 2020 on Coursera .

Many are already touting the benefits: Dr Amjad, a Professor at The University of Jordan who has been using Lark to teach his students says, “It has changed the way of teaching. It enables me to reach out to my students more efficiently and effectively through chat groups, video meetings, voting and also document sharing, especially during this pandemic. My students also find it is easier to communicate on Lark. I will stick to Lark even after coronavirus, I believe traditional offline learning and e-learning can go hand by hand."

These 3 charts show the global growth in online learning

The challenges of online learning.

There are, however, challenges to overcome. Some students without reliable internet access and/or technology struggle to participate in digital learning; this gap is seen across countries and between income brackets within countries. For example, whilst 95% of students in Switzerland, Norway, and Austria have a computer to use for their schoolwork, only 34% in Indonesia do, according to OECD data .

In the US, there is a significant gap between those from privileged and disadvantaged backgrounds: whilst virtually all 15-year-olds from a privileged background said they had a computer to work on, nearly 25% of those from disadvantaged backgrounds did not. While some schools and governments have been providing digital equipment to students in need, such as in New South Wales , Australia, many are still concerned that the pandemic will widenthe digital divide .

Is learning online as effective?

For those who do have access to the right technology, there is evidence that learning online can be more effective in a number of ways. Some research shows that on average, students retain 25-60% more material when learning online compared to only 8-10% in a classroom. This is mostly due to the students being able to learn faster online; e-learning requires 40-60% less time to learn than in a traditional classroom setting because students can learn at their own pace, going back and re-reading, skipping, or accelerating through concepts as they choose.

Nevertheless, the effectiveness of online learning varies amongst age groups. The general consensus on children, especially younger ones, is that a structured environment is required , because kids are more easily distracted. To get the full benefit of online learning, there needs to be a concerted effort to provide this structure and go beyond replicating a physical class/lecture through video capabilities, instead, using a range of collaboration tools and engagement methods that promote “inclusion, personalization and intelligence”, according to Dowson Tong, Senior Executive Vice President of Tencent and President of its Cloud and Smart Industries Group.

Since studies have shown that children extensively use their senses to learn, making learning fun and effective through use of technology is crucial, according to BYJU's Mrinal Mohit. “Over a period, we have observed that clever integration of games has demonstrated higher engagement and increased motivation towards learning especially among younger students, making them truly fall in love with learning”, he says.

A changing education imperative

It is clear that this pandemic has utterly disrupted an education system that many assert was already losing its relevance . In his book, 21 Lessons for the 21st Century , scholar Yuval Noah Harari outlines how schools continue to focus on traditional academic skills and rote learning , rather than on skills such as critical thinking and adaptability, which will be more important for success in the future. Could the move to online learning be the catalyst to create a new, more effective method of educating students? While some worry that the hasty nature of the transition online may have hindered this goal, others plan to make e-learning part of their ‘new normal’ after experiencing the benefits first-hand.

The importance of disseminating knowledge is highlighted through COVID-19

Major world events are often an inflection point for rapid innovation – a clear example is the rise of e-commerce post-SARS . While we have yet to see whether this will apply to e-learning post-COVID-19, it is one of the few sectors where investment has not dried up . What has been made clear through this pandemic is the importance of disseminating knowledge across borders, companies, and all parts of society. If online learning technology can play a role here, it is incumbent upon all of us to explore its full potential.

Our education system is losing relevance. Here's how to unleash its potential

3 ways the coronavirus pandemic could reshape education, celebrities are helping the uk's schoolchildren learn during lockdown, don't miss any update on this topic.

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Health and Healthcare Systems .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

This is how stress affects every organ in our bodies

Michelle Meineke

May 22, 2024

The care economy is one of humanity's most valuable assets. Here's how we secure its future

May 21, 2024

Antimicrobial resistance is a leading cause of global deaths. Now is the time to act

Dame Sally Davies, Hemant Ahlawat and Shyam Bishen

May 16, 2024

Inequality is driving antimicrobial resistance. Here's how to curb it

Michael Anderson, Gunnar Ljungqvist and Victoria Saint

May 15, 2024

From our brains to our bowels – 5 ways the climate crisis is affecting our health

Charlotte Edmond

May 14, 2024

Health funders unite to support climate and disease research, plus other top health stories

Shyam Bishen

May 13, 2024

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 25 January 2021

Online education in the post-COVID era

- Barbara B. Lockee 1

Nature Electronics volume 4 , pages 5–6 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

139k Accesses

211 Citations

337 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Science, technology and society

The coronavirus pandemic has forced students and educators across all levels of education to rapidly adapt to online learning. The impact of this — and the developments required to make it work — could permanently change how education is delivered.

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced the world to engage in the ubiquitous use of virtual learning. And while online and distance learning has been used before to maintain continuity in education, such as in the aftermath of earthquakes 1 , the scale of the current crisis is unprecedented. Speculation has now also begun about what the lasting effects of this will be and what education may look like in the post-COVID era. For some, an immediate retreat to the traditions of the physical classroom is required. But for others, the forced shift to online education is a moment of change and a time to reimagine how education could be delivered 2 .

Looking back

Online education has traditionally been viewed as an alternative pathway, one that is particularly well suited to adult learners seeking higher education opportunities. However, the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic has required educators and students across all levels of education to adapt quickly to virtual courses. (The term ‘emergency remote teaching’ was coined in the early stages of the pandemic to describe the temporary nature of this transition 3 .) In some cases, instruction shifted online, then returned to the physical classroom, and then shifted back online due to further surges in the rate of infection. In other cases, instruction was offered using a combination of remote delivery and face-to-face: that is, students can attend online or in person (referred to as the HyFlex model 4 ). In either case, instructors just had to figure out how to make it work, considering the affordances and constraints of the specific learning environment to create learning experiences that were feasible and effective.

The use of varied delivery modes does, in fact, have a long history in education. Mechanical (and then later electronic) teaching machines have provided individualized learning programmes since the 1950s and the work of B. F. Skinner 5 , who proposed using technology to walk individual learners through carefully designed sequences of instruction with immediate feedback indicating the accuracy of their response. Skinner’s notions formed the first formalized representations of programmed learning, or ‘designed’ learning experiences. Then, in the 1960s, Fred Keller developed a personalized system of instruction 6 , in which students first read assigned course materials on their own, followed by one-on-one assessment sessions with a tutor, gaining permission to move ahead only after demonstrating mastery of the instructional material. Occasional class meetings were held to discuss concepts, answer questions and provide opportunities for social interaction. A personalized system of instruction was designed on the premise that initial engagement with content could be done independently, then discussed and applied in the social context of a classroom.

These predecessors to contemporary online education leveraged key principles of instructional design — the systematic process of applying psychological principles of human learning to the creation of effective instructional solutions — to consider which methods (and their corresponding learning environments) would effectively engage students to attain the targeted learning outcomes. In other words, they considered what choices about the planning and implementation of the learning experience can lead to student success. Such early educational innovations laid the groundwork for contemporary virtual learning, which itself incorporates a variety of instructional approaches and combinations of delivery modes.

Online learning and the pandemic

Fast forward to 2020, and various further educational innovations have occurred to make the universal adoption of remote learning a possibility. One key challenge is access. Here, extensive problems remain, including the lack of Internet connectivity in some locations, especially rural ones, and the competing needs among family members for the use of home technology. However, creative solutions have emerged to provide students and families with the facilities and resources needed to engage in and successfully complete coursework 7 . For example, school buses have been used to provide mobile hotspots, and class packets have been sent by mail and instructional presentations aired on local public broadcasting stations. The year 2020 has also seen increased availability and adoption of electronic resources and activities that can now be integrated into online learning experiences. Synchronous online conferencing systems, such as Zoom and Google Meet, have allowed experts from anywhere in the world to join online classrooms 8 and have allowed presentations to be recorded for individual learners to watch at a time most convenient for them. Furthermore, the importance of hands-on, experiential learning has led to innovations such as virtual field trips and virtual labs 9 . A capacity to serve learners of all ages has thus now been effectively established, and the next generation of online education can move from an enterprise that largely serves adult learners and higher education to one that increasingly serves younger learners, in primary and secondary education and from ages 5 to 18.

The COVID-19 pandemic is also likely to have a lasting effect on lesson design. The constraints of the pandemic provided an opportunity for educators to consider new strategies to teach targeted concepts. Though rethinking of instructional approaches was forced and hurried, the experience has served as a rare chance to reconsider strategies that best facilitate learning within the affordances and constraints of the online context. In particular, greater variance in teaching and learning activities will continue to question the importance of ‘seat time’ as the standard on which educational credits are based 10 — lengthy Zoom sessions are seldom instructionally necessary and are not aligned with the psychological principles of how humans learn. Interaction is important for learning but forced interactions among students for the sake of interaction is neither motivating nor beneficial.

While the blurring of the lines between traditional and distance education has been noted for several decades 11 , the pandemic has quickly advanced the erasure of these boundaries. Less single mode, more multi-mode (and thus more educator choices) is becoming the norm due to enhanced infrastructure and developed skill sets that allow people to move across different delivery systems 12 . The well-established best practices of hybrid or blended teaching and learning 13 have served as a guide for new combinations of instructional delivery that have developed in response to the shift to virtual learning. The use of multiple delivery modes is likely to remain, and will be a feature employed with learners of all ages 14 , 15 . Future iterations of online education will no longer be bound to the traditions of single teaching modes, as educators can support pedagogical approaches from a menu of instructional delivery options, a mix that has been supported by previous generations of online educators 16 .

Also significant are the changes to how learning outcomes are determined in online settings. Many educators have altered the ways in which student achievement is measured, eliminating assignments and changing assessment strategies altogether 17 . Such alterations include determining learning through strategies that leverage the online delivery mode, such as interactive discussions, student-led teaching and the use of games to increase motivation and attention. Specific changes that are likely to continue include flexible or extended deadlines for assignment completion 18 , more student choice regarding measures of learning, and more authentic experiences that involve the meaningful application of newly learned skills and knowledge 19 , for example, team-based projects that involve multiple creative and social media tools in support of collaborative problem solving.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, technological and administrative systems for implementing online learning, and the infrastructure that supports its access and delivery, had to adapt quickly. While access remains a significant issue for many, extensive resources have been allocated and processes developed to connect learners with course activities and materials, to facilitate communication between instructors and students, and to manage the administration of online learning. Paths for greater access and opportunities to online education have now been forged, and there is a clear route for the next generation of adopters of online education.

Before the pandemic, the primary purpose of distance and online education was providing access to instruction for those otherwise unable to participate in a traditional, place-based academic programme. As its purpose has shifted to supporting continuity of instruction, its audience, as well as the wider learning ecosystem, has changed. It will be interesting to see which aspects of emergency remote teaching remain in the next generation of education, when the threat of COVID-19 is no longer a factor. But online education will undoubtedly find new audiences. And the flexibility and learning possibilities that have emerged from necessity are likely to shift the expectations of students and educators, diminishing further the line between classroom-based instruction and virtual learning.

Mackey, J., Gilmore, F., Dabner, N., Breeze, D. & Buckley, P. J. Online Learn. Teach. 8 , 35–48 (2012).

Google Scholar

Sands, T. & Shushok, F. The COVID-19 higher education shove. Educause Review https://go.nature.com/3o2vHbX (16 October 2020).

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T. & Bond, M. A. The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. Educause Review https://go.nature.com/38084Lh (27 March 2020).

Beatty, B. J. (ed.) Hybrid-Flexible Course Design Ch. 1.4 https://go.nature.com/3o6Sjb2 (EdTech Books, 2019).

Skinner, B. F. Science 128 , 969–977 (1958).

Article Google Scholar

Keller, F. S. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1 , 79–89 (1968).

Darling-Hammond, L. et al. Restarting and Reinventing School: Learning in the Time of COVID and Beyond (Learning Policy Institute, 2020).

Fulton, C. Information Learn. Sci . 121 , 579–585 (2020).

Pennisi, E. Science 369 , 239–240 (2020).

Silva, E. & White, T. Change The Magazine Higher Learn. 47 , 68–72 (2015).

McIsaac, M. S. & Gunawardena, C. N. in Handbook of Research for Educational Communications and Technology (ed. Jonassen, D. H.) Ch. 13 (Simon & Schuster Macmillan, 1996).

Irvine, V. The landscape of merging modalities. Educause Review https://go.nature.com/2MjiBc9 (26 October 2020).

Stein, J. & Graham, C. Essentials for Blended Learning Ch. 1 (Routledge, 2020).

Maloy, R. W., Trust, T. & Edwards, S. A. Variety is the spice of remote learning. Medium https://go.nature.com/34Y1NxI (24 August 2020).

Lockee, B. J. Appl. Instructional Des . https://go.nature.com/3b0ddoC (2020).

Dunlap, J. & Lowenthal, P. Open Praxis 10 , 79–89 (2018).

Johnson, N., Veletsianos, G. & Seaman, J. Online Learn. 24 , 6–21 (2020).

Vaughan, N. D., Cleveland-Innes, M. & Garrison, D. R. Assessment in Teaching in Blended Learning Environments: Creating and Sustaining Communities of Inquiry (Athabasca Univ. Press, 2013).

Conrad, D. & Openo, J. Assessment Strategies for Online Learning: Engagement and Authenticity (Athabasca Univ. Press, 2018).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Education, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, USA

Barbara B. Lockee

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Barbara B. Lockee .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The author declares no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Lockee, B.B. Online education in the post-COVID era. Nat Electron 4 , 5–6 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41928-020-00534-0

Download citation

Published : 25 January 2021

Issue Date : January 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41928-020-00534-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

A comparative study on the effectiveness of online and in-class team-based learning on student performance and perceptions in virtual simulation experiments.

BMC Medical Education (2024)

Leveraging privacy profiles to empower users in the digital society

- Davide Di Ruscio

- Paola Inverardi

- Phuong T. Nguyen

Automated Software Engineering (2024)

Growth mindset and social comparison effects in a peer virtual learning environment

- Pamela Sheffler

- Cecilia S. Cheung

Social Psychology of Education (2024)

Nursing students’ learning flow, self-efficacy and satisfaction in virtual clinical simulation and clinical case seminar

- Sunghee H. Tak

BMC Nursing (2023)

Online learning for WHO priority diseases with pandemic potential: evidence from existing courses and preparing for Disease X

- Heini Utunen

- Corentin Piroux

Archives of Public Health (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Beyond disruption: digital learning during the COVID-19 pandemic

Set against the backdrop of the COVID-19 education disruption and response, UNESCO’s flagship digital technologies in education event (formerly named Mobile Learning Week, 12-14 October 2020) highlighted innovations for technology-enabled futures of learning. Held virtually for the first time, the three-day event, under this year’s theme of ‘Beyond Disruption: Technology Enabled Learning Futures’ started the first day with sharing distance learning policies and evaluating effectiveness, followed by showcasing innovative solutions throughout the second day, and concluded on the third day with setting out policy and research agendas to build back better.

Organized in partnership with the International Telecommunication Union and in collaboration with Ericsson, GIZ, Huawei, Microsoft, Norad, and ProFuturo amidst the largest education disruption in history due to the COVID-19 pandemic , this year’s conference focused on distance learning solutions to build back better. It examined the medium and long-term implications of the learning crisis that forced 1.6 billion learners worldwide out of the classroom, and the challenges that lie ahead. The event also shared best practices and explored innovative solutions to resolve this crisis.

“Technology and connectivity are integral to building more resilient, flexible, and open systems,” said Stefania Giannini during the Opening Ceremony. “Let us together define how to use technology to help meet the enormous challenge before us inclusively and fairly. What we do need now is another evaluation of what didn’t work”.

Effective policies – sharing policies and evaluating effectiveness

After months of large-scale experimentation with distance learning, panel discussions with high-level representatives of UN agencies, ministers, and experts attempted to draw specific forward-looking policy advice. The first day featured a ministerial level panel to present various country-level responses. Ministers of Education from Côte d'Ivoire, Egypt, Ethiopia, Finland, and South Sudan recounted their national efforts to provision distance learning at unprecedented speed and scale.

“Exceptional times require flexible measures and a lot of creativity by teachers,” said Li Andersson, Finland’s Minister of Education. “While the ability of teachers to transfer teaching online proved even better than had been expected, it is clear that distance learning can never fully replace the physical classrooms. Schools are much more than places for learning. They provide social networks, safety and well-being for children and youth.”

Gabriel Changson Chang, South Sudanese Minister of Higher Education, Science and Technology stated, “technology-enabled learning futures can help shape the future of South Sudan’s higher education opportunities. The Republic of South Sudan hopes to draw lessons from a range of education responses during COVID-19 to inform the planning of technology-enabled inclusive and resilient learning systems for the future.”

Innovative solutions – showcasing innovative distance learning solutions

The second day of the conference showcased solutions from sponsors and members of the Global Education Coalition , and featured exhibitions from technology providers. One highlight was the EduTech keynote session focusing on the Khan Academy, whose Founder, Salman Khan, shared his experience during the pandemic in creating online educational tools, “the digital divide is the number one headline of COVID-19. What we are trying to do is to build for the rebuilding phase.” Barbara Holzapfel, Vice President of Microsoft Education, contributed to the day’s discussion by stating, “COVID-19 has accelerated the transformation [in education] that was well underway and we’ve seen years’ worth of change in just a matter of weeks. On the other side, the acceleration of change also brings an opportunity to reimagine the future of education and chart a path that is inclusive for all students around the world. “

The future – setting out policy and research agendas to build back better

The conference concluded with the exploration of how education systems can emerge from the crisis stronger and more resilient to future disruptions. Sessions highlighted successful policy interventions in India and Finland, solutions to build back more gender-equal education systems, and innovations to digitize educational content and pedagogy. The event concluded on a positive note with a High-Level Panel outlining the way forward in the presence of the Minister of Education from Ecuador. She put forward the importance of the “flexibility of the education system” in addressing gaps and inequality in education, “in order to respond to the different situations”. She was joined by key representatives from UNESCO, Dubai Cares, ITU, the World Bank, UNICEF, ProFuturo Foundation, and the Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization (SEAMEO).

In her closing remarks, the Assistant Director General for Education Stefania Giannini underlined: “Change is possible. Education is a promise to provide an equal chance to students for education. However, the way to address inequalities is still a challenge.”

- Videos, presentations, agenda, speakers’ bio and more resources available at https://mlw2020.org/#/home

- Six months into a crisis: Reflections on international efforts to harness technology to maintain the continuity of learning

Related items

More on this subject.

Other recent articles

Remote Learning During COVID-19: Lessons from Today, Principles for Tomorrow

"Remote Learning During the Global School Lockdown: Multi-Country Lessons” and “Remote Learning During COVID-19: Lessons from Today, Principles for Tomorrow"

WHY A TWIN REPORT ON THE IMPACT OF COVID IN EDUCATION?

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted education in over 150 countries and affected 1.6 billion students. In response, many countries implemented some form of remote learning. The education response during the early phase of COVID-19 focused on implementing remote learning modalities as an emergency response. These were intended to reach all students but were not always successful. As the pandemic has evolved, so too have education responses. Schools are now partially or fully open in many jurisdictions.

A complete understanding of the short-, medium- and long-term implications of this crisis is still forming. The twin reports analyze how this crisis has amplified inequalities and also document a unique opportunity to reimagine the traditional model of school-based learning.

The reports were developed at different times during the pandemic and are complementary:

The first one follows a qualitative research approach to document the opinions of education experts regarding the effectiveness of remote and remedial learning programs implemented across 17 countries. DOWNLOAD THE FULL REPORT

WHAT ARE THE LESSONS LEARNED OF THE TWIN REPORTS?

- Availability of technology is a necessary but not sufficient condition for effective remote learning: EdTech has been key to keep learning despite the school lockdown, opening new opportunities for delivering education at a scale. However, the impact of technology on education remains a challenge.

- Teachers are more critical than ever: Regardless of the learning modality and available technology, teachers play a critical role. Regular and effective pre-service and on-going teacher professional development is key. Support to develop digital and pedagogical tools to teach effectively both in remote and in-person settings.

- Education is an intense human interaction endeavor: For remote learning to be successful it needs to allow for meaningful two-way interaction between students and their teachers; such interactions can be enabled by using the most appropriate technology for the local context.

- Parents as key partners of teachers: Parent’s involvement has played an equalizing role mitigating some of the limitations of remote learning. As countries transition to a more consistently blended learning model, it is necessary to prioritize strategies that provide guidance to parents and equip them with the tools required to help them support students.

- Leverage on a dynamic ecosystem of collaboration: Ministries of Education need to work in close coordination with other entities working in education (multi-lateral, public, private, academic) to effectively orchestrate different players and to secure the quality of the overall learning experience.

- FULL REPORT

- Interactive document

- Understanding the Effectiveness of Remote and Remedial Learning Programs: Two New Reports

- Understanding the Perceived Effectiveness of Remote Learning Solutions: Lessons from 18 Countries

- Five lessons from remote learning during COVID-19

- Launch of the Twin Reports on Remote Learning during COVID-19: Lessons for today, principles for tomorrow

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

SCIENCE & ENGINEERING INDICATORS

Elementary and secondary stem education.

- Report PDF (1.9 MB)

- Report - All Formats .ZIP (9.5 MB)

- Supplemental Materials - All Formats .ZIP (4.0 MB)

- MORE DOWNLOADS OPTIONS

- Share on X/Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

- Send as Email

Online Education in STEM and Impact of COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic led to school building closures in March 2020 and an unprecedented, near-total transition to online or alternative learning, affecting approximately 55 million students in 124,000 U.S. public and private schools (Education Week 2020a). In fall 2020, the majority of school districts continued to rely on a distance-learning model for instruction, including some of the nation’s largest school districts, such as Los Angeles Unified School District and Chicago Public Schools (Education Week 2020b). In response to these shifts in instruction, many researchers are endeavoring to understand the impact on students and are finding that there may be long-term effects on student learning (see sidebar Learning Losses and COVID-19).

Learning Losses and COVID-19: The Pandemic’s Potential Long-Term Impact on Students

Studies from the Annenberg Institute at Brown University and the Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO) at Stanford University project that there may be substantial learning losses for students because of the COVID-19 pandemic. These studies estimate, for example, that some students may lose up to a full year of math learning. These studies find that learning losses are not distributed evenly among all students and that some groups of students may be more negatively affected than others, such as students from low-income households or those with disabilities. These researchers caution that the results of these projections are estimates and should be interpreted carefully. However, based on their research, they conclude that the educational disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic have the potential to negatively affect student learning and education. As a result, they suggest, schools should allocate additional resources to help students, especially the most vulnerable, accelerate their learning and regain these losses (CREDO 2020, Kuhfeld et al. 2020).

A report from the Annenberg Institute at Brown University estimates that students began the 2020–21 school year with a third to a half of the learning gains in math relative to a normal school year (Kuhfeld et al. 2020). The study used data from 5 million student test scores and utilized models based on student learning loss due to absenteeism, school closures, and summer break to project the effects of COVID-19 educational disruptions on student learning from spring 2020 (when most schools temporarily closed and then shifted to online instruction) through fall 2020 (the start of the 2020–21 school year). The authors note that their estimated reduction in the expected year-to-year math gains is not evenly distributed; some students may experience little loss, while others, particularly those from low-income households and students who were already low performing, may experience greater losses. The authors estimate that these more vulnerable students may have returned to school in fall 2020 already nearly a full year behind in math.

CREDO also estimates that some students may have lost up to a year of learning in math (CREDO 2020). The researchers used information based on prior years’ achievement scores, days of instruction lost due to the pandemic, and projected learning losses associated with out-of-school time to estimate the amount of learning students lost by the end of the 2019–20 school year. CREDO provided estimates for 19 states and suggested that these learning losses could result from students not learning new concepts and not experiencing reinforcement of concepts already learned.

In a paper from the World Bank, researchers used data from 157 countries to estimate global learning losses due to education disruptions caused by COVID-19 and determined that students on average could lose from a third of a year to almost a full year of schooling as a result of the pandemic (Azevedo et al. 2020). They also estimated larger losses for more vulnerable groups, including ethnic minorities and students with disabilities, who could be more adversely affected by school closures.

In addition to estimating learning losses, researchers have estimated the economic impact of education losses resulting from COVID-19. These projections reflect current thinking about the economic impact of these losses, but they are based on economic conditions that are subject to change over time. As with learning loss, however, most researchers do agree that there will likely be some economic impact due to education losses resulting from the pandemic. A report from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development estimates that the global closure of schools could lead to a 3% lower income for K–12 students over their lifetime and a corresponding average of 1.5% lower annual gross domestic product for countries for the remainder of the century (Hanushek and Woessmann 2020). A report from McKinsey Insights estimates that the average K–12 student in the United States could lose the equivalent of a year of full-time work income over the course of his or her lifetime, and these losses may be higher for Black and Hispanic students (Dorn et al. 2020).

This sections draws on education data from the Household Pulse Survey, a nationally representative survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau in collaboration with five federal agencies to gather data on the effects of COVID-19 on American households. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey/technical-documentation.html ." data-bs-content="The questionnaire is a result of collaboration between the U.S. Census Bureau and the U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the National Center for Health Statistics, NCES, and the Department of Housing and Urban Development. The Household Pulse Survey has been conducted in three phases. Data presented here are from Phase 1 and Phase 2. Each phase utilizes an overlapping weekly panel of respondents, each of whom are surveyed once per week for 3 consecutive weeks before being replaced by a new panel. Each phase is designed to be nationally representative of the U.S. population, though different panels responded in the Phase 1 and Phase 2 data collections. For more information, see https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey/technical-documentation.html ." data-endnote-uuid="59ecfbd8-3626-4789-a2de-3966661d1832"> The questionnaire is a result of collaboration between the U.S. Census Bureau and the U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the National Center for Health Statistics, NCES, and the Department of Housing and Urban Development. The Household Pulse Survey has been conducted in three phases. Data presented here are from Phase 1 and Phase 2. Each phase utilizes an overlapping weekly panel of respondents, each of whom are surveyed once per week for 3 consecutive weeks before being replaced by a new panel. Each phase is designed to be nationally representative of the U.S. population, though different panels responded in the Phase 1 and Phase 2 data collections. For more information, see https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey/technical-documentation.html . Although they are not specific to STEM classes, these data offer insight into student access to computers and the Internet as well as the amount of time families spent on education during the pandemic, both in spring 2020, immediately after the transition to distance learning for most students, and in fall 2020, when students returned to school either in person or virtually. To provide context for the pandemic-related shift to digital instruction, this section also presents data about teachers’ and students’ use of technology before the pandemic. These data show that the use of technology and online instruction were not widely prevalent before COVID-19 and underscore the challenges of a shift to fully remote and hybrid learning approaches during the pandemic.

Education during COVID-19

Household Pulse Survey data help illustrate how the COVID-19 pandemic affected schools, students, and families, including how schools and districts were able to make some adjustments by fall 2020 to improve access to teachers and digital devices needed for online learning. In the first week of May 2020, adults in households with children enrolled in K–12 schools reported an average of 13 hours per week spent on teaching activities with children , with Asian households reporting the lowest amount of time at about 10 hours per week. On average, students spent about 4 hours per week in live virtual contact with their teachers, but this fell to about 3 hours for households in which the respondent had less than a high school education ( Table K12-7 ).

Average number of hours in the past week spent on home-based education in households with children enrolled in K−12 school, by selected adult characteristics: 7−12 May 2020

a Hispanic may be any race; race categories exclude Hispanic origin.

The table includes adults 18 years and older in households with children enrolled in K−12 school.

National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, special tabulations (2020) of the 2020 U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey.

Science and Engineering Indicators

In September 2020, respondents reported how much time their child spent on learning activities in the last week compared with a regular school day prior to the pandemic ( Table K12-8 ). About half reported “as much,” “a little bit more,” or “much more” time spent, while one-fourth reported “a little bit less” time spent. More than one-fourth of respondents reported that their child spent “much less” time on learning activities compared with pre-COVID-19 instruction.

Adults who reported time that their children spent on all learning activities in the past week relative to a school day before the COVID-19 pandemic, by selected adult characteristics: 16−28 September 2020

The table includes adults 18 years and older in households with children enrolled in K−12 school. Adults in households with only homeschooled children are not included. Percentages may not add to 100% because of rounding.

A majority of respondents (85%) reported that their children had at least 2 days a week of live contact with their teachers, either in person or by phone or video ( Table K12-9 ). More than two-thirds of respondents reported that their children had 4 days or more of contact with their teacher in the last week. However, 11% of respondents reported that their child had no contact with their teacher in the last week. In addition, live contact with teachers varied by students’ household income and parental education. About 16% of households with the lowest income levels (below $25,000), as well as 20% of households in which the respondent had less than a high school education, reported no teacher contact. This compared with 6% of households at the highest income level ($200,000 and above) and 7% of households in which the respondent reported a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Adults who reported frequency of live contact of children with their teachers in person, by phone, or by video in the past week, by selected adult characteristics: 16−28 September 2020

Although the proportion of respondents indicating that their child’s classes were delivered fully online declined from 73% in May 2020 to 66% in September 2020 ( Table SK12-30 ), in the majority of households with K–12 students, the students continued to receive fully online instruction in fall 2020, which underscores the importance of understanding students’ access to computers and the Internet. The percentage of respondents reporting that a computer or other digital device and the Internet were always available for children to use at home for educational purposes increased from about 70% in May 2020 to about 77% in September 2020, although these proportions varied by household characteristics ( Table K12-10 ). For example, 44% of households at the lowest education level of less than high school reported in May 2020 that a computer was always available for educational purposes compared with 62% in September 2020. However, this was still lower than the 85% of households with a bachelor’s degree or higher who reported the same in September 2020.

Adults who reported that a computer or other digital device and the Internet were always available for children to use at home for educational purposes, by selected adult characteristics: 7−12 May 2020 and 16−28 September 2020

Adults in households with only homeschooled children are not included. Percentages may not add to 100% because of rounding.

Schools and districts made progress in providing computers to students to use for educational purposes between May 2020 and the beginning of the new school year in fall 2020. About 40% of respondents reported that the child’s school or district provided a computer for educational use in May 2020. That figure rose to 61% in September 2020 ( Table SK12-32 ). The percentage of respondents reporting that the school or school district paid for Internet services changed slightly from 2% to 4% between May 2020 and September 2020, and nearly all respondents (97%) reported paying for these services themselves in both months.

Student and Teacher Use of Technology Prior to COVID-19

Pre-COVID-19 data on eighth-grade students’ use of the Internet and computers to complete various learning activities indicate that there may have been a significant learning curve involved in the shift to remote instruction, when most schoolwork needed to be completed online. The 2018 ICILS offers insight into how students used information and computer technology for a variety of learning activities before COVID-19 ( Figure K12-28 ). Almost three-fourths of students reported using the Internet to do research at least once a week. It was less common for students to use computers for other activities, such as completing worksheets or exercises (56%), taking tests (43%), using software to learn skills or subjects (33%), and working online with other students (30%).

- For grouped bar charts, Tab to the first data element (bar/line data point) which will bring up a pop-up with the data details

- To read the data in all groups Arrow-Down will go back and forth

- For bar/line chart data points are linear and not grouped, Arrow-Down will read each bar/line data points in order

- For line charts, Arrow-Left and Arrow-Right will move to the next set of data points after Tabbing to the first data point

- For stacked bars use the Arrow-Down key again after Tabbing to the first data bar

- Then use Arrow-Right and Arrow-Left to navigate the stacked bars within that stack

- Arrow-Down to advance to the next stack. Arrow-Up reverses

U.S. students in grade 8 who reported using information and communications technologies for learning activities every school day or at least once a week, by activity: 2018

International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA), International Computer and Information Literacy Study (ICILS), 2018. https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/icils/icils2018/theme1.asp?tabontop .

ICILS also offers insight into the extent to which U.S. eighth-grade teachers participated in professional development in using information and communications technologies (ICT) for various teaching tasks before the pandemic ( Figure K12-29 ). These numbers suggest that eighth-grade teachers had some familiarity with using technology for instruction before the pandemic, although likely not at the levels needed to be fully online or responsive to the individual needs of students. About two-thirds of teachers reported participating in training on subject-specific digital resources or taking a course on integrating ICT into teaching and learning between 2016 and 2018. Less than half of teachers reported taking a course on how to use ICT to support personalized learning by students, and only a third reported taking a course on using ICT for students with special needs. About 60% of teachers reported that they had sufficient time to develop lessons incorporating technology and to develop expertise in the use of technology for teaching during the 2017–18 school year ( Table SK12-35 ).

U.S. eighth-grade teachers who reported participating in technology-related professional learning activities at least once in the past 2 years, by type of activity: 2018

Related content.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

The COVID-19 pandemic and E-learning: challenges and opportunities from the perspective of students and instructors

Abdelsalam m. maatuk.

1 Faculty of Information Technology, Benghazi University, Benghazi, Libya

Ebitisam K. Elberkawi

Shadi aljawarneh.

2 Faculty of Computer and Information Technology, Irbid, Jordan

Hasan Rashaideh

3 Department of Computer Science, Prince Abdullah Ben Ghazi Faculty of Information Technology and Communication Technology, Al-Balqa Applied University, Salt, 19117 Jordan

Hadeel Alharbi

4 Computer Science, Ha’il University, Ha’il, Saudi Arabia

The spread of COVID-19 poses a threat to humanity, as this pandemic has forced many global activities to close, including educational activities. To reduce the spread of the virus, education institutions have been forced to switch to e-learning using available educational platforms, despite the challenges facing this sudden transformation. In order to further explore the potentials challenges facing learning activities, the focus of this study is on e-learning from students’ and instructor’s perspectives on using and implementing e-learning systems in a public university during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study targets the society that includes students and teaching staff in the Information Technology (IT) faculty at the University of Benghazi. The descriptive-analytical approach was applied and the results were analyzed by statistical methods. Two types of questionnaires were designed and distributed, i.e., the student questionnaire and the instructor questionnaire. Four dimensions have been highlighted to reach the expected results, i.e., the extent of using e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, advantages, disadvantages and obstacles of implementing E-learning in the IT faculty. By analyzing the results, we achieved encouraging results that throw light on some of the issues, challenges and advantages of using e-learning systems instead of traditional education in higher education in general and during emergency periods.

Introduction

The unexpected closure of educational institutions as a result of the emergence of COVID-19 prompted the authorities to suggest adopting alternatives to traditional learning methods in emergencies to ensure that students are not left without studying and to prevent the epidemic from spreading.

The formal learning system with the help of electronic resources is known as e-learning. Whereas teaching can be inside (or outside) the classrooms, the use of computer technology and the Internet is the main component of e-learning (Aboagye et al. ( 2020 ). The traditional educational methods were replaced by e-learning when the COVID-19 virus appeared because social gatherings in educational institutions are considered an opportunity for the virus to spread. E-learning is the best option available to ensure that epidemics do not spread, as it guarantees spatial distancing despite the challenges and studied figures, which indicate that students are less likely to benefit from this type of education (Lizcano et al. ( 2020 ).

Information and communication technologies (ICTs) offer unique educational and training opportunities as they improve teaching and learning, and innovation and creativity for people and organizations. Furthermore, the use of ICT can promote the development of an educational policy that encourages creative and innovative educational institution environments (Abdullah et al. 2019 ; Altawaty et al. 2020 ; Selim, 2007 ). Therefore, attention is given widely to efforts and experiences related to this type of education. This technology is commonly used by most universities in several developing countries. In an educational environment, there are lots of learning-related processes involved, and great amounts of potential rich data are generated in educational institutions continuously in order to extract knowledge from those data for a better understanding of learning-related processes (Aljawarneh, 2020 ; Lara et al. 2020 ; Lizcano et al. 2020 ).

E-learning is playing a vital role in the existing educational setting, as it changes the entire education system and becomes one of the greatest preferred topics for academics (Samir et al. 2014 ). It is defined as the use of diverse kinds of ICT and electronic devices in teaching (Gaebel et al. ( 2014 ). Most students today want to study online and graduate from universities and colleges around the world, but they cannot go anywhere because they reside in isolated places without good communication services.

Because of e-learning, participants can save time and effort for living in distant places from universities where they are registered, so, many scholars support online courses (Ms & Toro, 2013 ).

Many users of e-learning platforms see that online learning helps ensure that e-learning can be easily managed, and the learner can easily access the teachers and teaching materials (Gautam, 2020 ; Mukhtar et al. 2020). It also helped reduce the effort and travel expenses and other expenses that accompany traditional learning. E-learning reduced significantly the administrative effort, preparation and lectures recording, attendance, and leaving classes. Teachers, as well as students, see that online learning methods encouraged pursuing lessons from anywhere and in difficult circumstances that prevent them from reaching universities and schools. The student becomes a self-directed learner and learns simultaneously and asynchronously at any time. However, there are many drawbacks of e-learning, the most important of which is getting knowledge only on a theoretical basis and when it comes to using everything that learners have learned without applied practical skills. The face-to-face learning experience is missing, which may interest many learners and educators. Other problems are related to the online assessments, which may be limited to objective questions. Issues related to the security of online learning programs and user reliability are among the challenges of e-learning in addition to other difficulties that are always related to the misuse of technology (Gautam, 2020 ; Mukhtar et al. 2020).

Web-based education, digital learning, interactive learning, computer-assisted teaching and internet-based learning are known as E-learning (Aljawarneh, 2020 ; Lara et al. 2020 ; Yengin et al. 2011 ). It is mainly a web-based education system that provides learners with information or expertise utilizing technology. The use of web-based technology for educational purposes has increased rapidly due to a drastic reduction in the cost of implementing these technologies. Nowadays, many universities have recognized the importance of E-learning as a core element of their learning system. Therefore, further research has been conducted to understand the difficulties, advantages, and challenges of e-learning in higher education. These issues have the potential to adversely affect instructors' quality in the delivery of educational material (Yengin et al. 2011 ).

Technology-based E-learning requires the use of the internet and other essential tools to generate educational materials, educate learners, and administer courses in an organization. E-learning is flexible when considering time, location, and health issues. It increases the effectiveness of knowledge and skills by enabling access to a massive amount of data, and enhances collaboration, and also strengthens learning-sustaining relationships. Although e-learning can enhance the quality of education, there is an argument about making E-learning materials available, which leads to improving learning outcomes only for specific types of collective evaluation. However, e-learning may result in the heavy use of certain websites. Moreover, it cannot support domains that require practical studies. The main drawback of using e-learning is the absence of crucial personal interactions, not only between students and teachers but also among fellow students (Somayeh et al. 2016 ). Compared to developed countries, it was found that developing countries face many challenges in applying e-learning, including poor internet connection, insufficient knowledge about the use of information and communication technology, and weak content development (Aung & Khaing, 2015 ). The provision of content such as video and advanced applications is still a new thing for many educators, even at the higher education level in developing countries (Aljawarneh, 2020 ; Lara et al. 2020 ; Lizcano et al. 2020 ).

This study aims to identify issues related to the use, advantages, disadvantages, and obstacles of e-learning programs in a public university by extrapolating the perspectives of students and educators who use this mode of learning in long-lasting unusual circumstances. The research population consisted of students and faculty members at the Faculty of IT at the University of Benghazi. Two types of questionnaires have been distributed to students and instructors. To achieve the expected results, four dimensions are defined, i.e., the extent to which E-learning is used and the benefits, drawbacks, and obstacles to the implementation of E-learning by the Faculty of IT. The descriptive-analytical method is used in the statistical analysis of the results. By evaluating the results, we have obtained promising findings that demonstrate some of the higher education sector's problems, obstacles, and advantages of using the E-learning method. Students believe that based on the study’s results, E-learning contributes to their learning. This reduces the instructor workload, however, and raises it for students. The teaching staff agrees that E-learning is beneficial in enhancing the skills of students, although it needs financial resources and the cost of implementing them is high. Despite the advantages of using E-learning, some of the obstacles to its implementation in Libya include the degradation of the Internet infrastructure that supports these education systems in Libya in general. The high cost of buying the electronic equipment needed and maintaining the equipment, which is unemployed.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 gives some background and related work about E-learning. Section 3 describes the methodology. Statistical analysis is presented in Sect. 4. Section 5 explains the study outcomes. Finally, Sect. 6 discusses the conclusion of this work and provides some recommendations.

Related work

Several studies have addressed the opportunities and challenges associated with the transition to traditional learning instead of e-learning. One of the main reasons for faltering e-learning initiatives is the lack of well-preparedness for this experience.

A study that aims to examine student challenges about how to deal with e-learning in the outbreak of COVID-19 and to examine whether students are prepared to study online or not is presented in (Aboagye et al. 2020 ). The study concluded that a blended approach that combines traditional and e-teaching must be available for learners. Another study that aims to explore the e-learning process among students who are familiar with web-based technology to advance their self-study skills is described in (Radha et al. 2020 ). The study results show that e-learning has become popular among students in all educational institutions in the period of lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

A study that aims to investigate the characteristics, benefits, drawbacks and features that impact E-learning has been presented in (Ms & Toro, 2013 ). Some of the demographic features such as behaviors and cultural background impact student education in the E-learning domain. Therefore, for lecturers to design educational activities to make learning more effective, they should understand these features. The study is applied to students in Lebanon and England to assist instructors to understand what scholars expect from the learning management systems.

Analyzing the effectiveness of E-learning for students at the university level has been introduced in (Ali et al. 2018 ). A questionnaire was applied to a sample of 700 students, 94.9% of them are utilizing different e-learning techniques and tools. To measure the reliability and internal consistency of the factors, Cronbach’s alpha test is applied. To take out the variables and to calculate the factors loading in the study, the exploratory feature analysis is applied. The results demonstrate that students support that E-learning is easy to use, saves time, and affordable.

Various predictions of e-learning for educational purposes have been illustrated in (Samir et al. 2014 ). The study aims to show how to keep students motivated in e-learning. The evaluation of student motivations for online learning can be challenging because of the lack of face-to-face contact between learners and teachers. The study shows that one way to increase student’s motivation is by allowing them to complete an online assessment form on motivation. The study suggests five research hypotheses to be inspected to identify which hypothesis should be accepted and which should not.

The strength of the relationship between students’ motivation and e-learning is illustrated in (Harandi, 2015 ). Data was gathered from students at Tehran Alzahra University, and Pearson's correlation coefficient was utilized for data analysis. The outcomes of this study revealed that some points should be considered before using E-learning. However, this study was restricted to one culture, which can limit the generalization of its results.

The study described in (Oludare Jethro et al. 2012 ) showed that e-learning is a new atmosphere for scholars, as it illustrates how to make e-learning more effective in the educational field and the advantages of using e-learning. The outcome of the study showed that the students were willing to learn more with less social communication with other students or lecturers.

A study that aims to highlight and measure the four Critical Success Factors from student insights is described in (Selim, 2007 ). These factors are instructor and student characteristics, technology structure, and university support. The outcomes of the study showed that the instructor characteristics factor is the most critical one followed by IT infrastructure and university support in e-learning success. The least critical factor to the success of e-learning was student characteristics.

The work described in (GOYAL & S., 2012 ) has tried to emphasize the importance of e-learning in modern teaching and illustrates its advantages and disadvantages. Also, the comparison with Instructor Led Training (ILT) and the probability of applying E-learning instead of old classroom teaching was discussed. In addition, the study showed the major drawbacks of ILT in institutions and how using E-learning can assist in overcoming these problems.

The purpose of the study in (Gaebel et al. 2014 ) is to conduct a survey on the varieties of E-learning organizations, skills, and their anticipations for the forthcoming. Blended and online learning are taken into account. Some of the questions related to intra-institutional management, arrangements and services, and quality assurance. The outcomes of the survey showed that from 38 diverse countries and systems, there are 249 organizations broadly conceived the same causes for the increasing use of e-learning.

The study in (Yengin et al. 2011 ) illustrated that the most vital role in the e-learning design outlook is online lecturers. As a result, considering the issues impacting lecturers’ performance should be taken into the account. One of the features that impact the usability of the system and lecturers’ presentation is satisfaction. The results showed, to produce a simple model called the “E-learning Success Model for Instructors’ Satisfactions” that is related to public, logical and technical communications of instructors in the entire e-learning system, the features associated with teachers’ satisfaction in e-learning systems have been examined.

The comparison between different E-learning tools in terms of their goals, benefits and drawbacks are presented in (Aljawarneh et al. 2010 ). The comparison assists in providing when to use each tool. The outcomes show that instructors and students prefer to use MOODLE over Blackboard in the e-learning environment. One of the major challenges that face the E-learning environment is security issues since security is not combined into the active learning development process.

The effect of e-learning at the Payame Noor University of Hamedan, Iran on the innovation and material awareness of chemistry students was examined in (Zare et al. 2016 ). The research used a control group's pre-test/post-test experimental design. Data analysis findings using the independent t-test showed significantly better scores on calculated variables, information and innovation for the experimental group. Consequently, E-learning is beneficial for the acquisition of knowledge and innovation among chemistry students, and that a larger chance for E-learning should be given for broader audiences.

A study in (Arkorful & Abaidoo, 2015 ) aimed to explore the literature and provide the study with a theoretical context by reviewing some publications made by different academics and universities on the definition of E-learning, its use in education and learning in institutions of higher education. The general literature described the pros and cons of E-learning, which showed that it needs to be enforced in higher education for teachers, supervisors and students to experience the full advantages of acceptance and implementation.

Assessing the learning effectiveness of e-learning was studied in (Somayeh et al. 2016 ). This analysis study was conducted using the databases of Medline and CINAHL and the search engine of Google. The research used covered review articles and English language meta-analysis. 38 papers including journals, books, and websites are investigated and categorized from the results obtained. The general advantages of E-learning such as the promotion of learning and speed and process of learning due to individual needs were discussed. The study results indicated positive effects of E-learning on learning, so it is proposed that more use should be made of this education method, which needs the requisite grounds to be established.

It is important to focus on analyzing the learner and student characteristics and motivating students to ensure their involvement in e-learning. Also, it is necessary to focus on the impact and extent of teacher acceptance of e-learning. The age difference between the teachers and the students indicates that the teachers received most of their studies and teaching skills through traditional teaching and learning methods, which may make their acceptance of e-learning different from the student’s acceptance of modern methods of e-learning and education in general.

The methodology

The descriptive-analytical method was used for this study and the five-point Likert-scale range was calculated based on (1) Strongly disagreed, (2) Disagree, (3) Neutral, (4) Agree, and (5) Strongly agree, with the analysis of results using a statistical application called the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS).

Study population

The study targets the sample society that includes teaching staff and undergraduate students of all departments in the IT Faculty at the University of Benghazi.

Study boundaries

- Scientific restrictions: Assessment of the extent of application of E-learning in higher education.

- Administrative Field: Faculty of IT, University of Benghazi, Libya.

- Period: The Year of 2020.

- Human Resources: Teaching staff and students in the faculty.

Study sample

The study involves two types of questionnaires to be prepared and developed: one questionnaire for students and another for instructors. The following details were obtained after the questionnaires were randomly distributed and collected individually. The study sample was selected based on the awareness of the size of the population:

- Student Questionnaire: The total number of distributed questionnaires was 140 copies, without invalid copies, and 5 copies were missing. Therefore, the copies being analyzed are 135.

- Teaching Staff Questionnaire: The total number of distributed questionnaires was 20 copies, while 20 legitimate copies were returned without invalid or missing copies.

Some of the demographic characteristics are shown in Table Table1 1 .

Distribution of student study sample

Study dimensions

The study has emphasized four dimensions to achieve the expected results as follows:

- The extent of using E-learning in the Faculty of IT.

- Advantages of E-learning.

- Disadvantages of E-learning.

- Obstacles to implementing E-learning.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis.

The Means and Materiality statistical relations are used to analyze the results. By evaluating the findings, we gain crucial information based on these statistical relations according to the rank of inquiries as shown in Tables Tables2 2 – 3 .

Descriptive statistics of students' perspective

Descriptive statistics of teaching staff perspective

The students' perspective

The analysis of data as a statistical relationship regarding the perspective of the students is shown in Table Table2 2 .

Dimension 1: the extent of using E-learning in IT faculty.

Inquiries (6), (7) and (10) are of similar materiality and inquiry (6) is chosen because it has the lower standard deviation, which states that "E-learning technologies are used for scientific research purposes" with the materiality of 82.6% and a mean 4.13, while inquiry number (7), which states "Search engines are used to obtain curriculum needs". However, inquiry (2), which states that "the Internet is available to students at the faculty” has the lowest materiality of 40% and a mean 2.

Dimension 2: advantages of E-learning

Inquiry number (1) states that "E-learning contributes to raising your educational level" has the highest materiality of 88.2% and a mean of 4.41. However, inquiry number (7), which states that "E-learning reduces the burden because learning becomes a conversation between teaching staff and students instead of traditional learning", has the lowest materiality of 75.8% and a mean of 3.79.

Dimension 3: disadvantages of E-learning

Inquiries (5) and (6) are of similar materiality and inquiry number (5) is chosen because it has the lower standard deviation, which states that "E-learning reduces the burden of teaching staff and increases the burden of students” with the materiality of 75.4% and a mean of 3.77. Nevertheless, inquiry number (1), which states that "E-learning isolates you from the community by connecting you to your computer for long periods ", was the lowest materiality of 72.6% and a mean of 3.63.

Dimension 4: obstacles to E-learning

Inquiry number (3) states that "the lack of the Internet in the faculty to apply E-learning" has the highest materiality of 79% and a mean of 3.95. Yet, inquiries (4) and (5) are of similar materiality and inquiry number (5) has been chosen as it has the lower standard deviation, which notes that "Lack of experience of students with E-learning techniques” with the materiality of 71.8% and a mean of 3.59.

Teaching staff perspective