- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Table of Contents

Questionnaire

Definition:

A Questionnaire is a research tool or survey instrument that consists of a set of questions or prompts designed to gather information from individuals or groups of people.

It is a standardized way of collecting data from a large number of people by asking them a series of questions related to a specific topic or research objective. The questions may be open-ended or closed-ended, and the responses can be quantitative or qualitative. Questionnaires are widely used in research, marketing, social sciences, healthcare, and many other fields to collect data and insights from a target population.

History of Questionnaire

The history of questionnaires can be traced back to the ancient Greeks, who used questionnaires as a means of assessing public opinion. However, the modern history of questionnaires began in the late 19th century with the rise of social surveys.

The first social survey was conducted in the United States in 1874 by Francis A. Walker, who used a questionnaire to collect data on labor conditions. In the early 20th century, questionnaires became a popular tool for conducting social research, particularly in the fields of sociology and psychology.

One of the most influential figures in the development of the questionnaire was the psychologist Raymond Cattell, who in the 1940s and 1950s developed the personality questionnaire, a standardized instrument for measuring personality traits. Cattell’s work helped establish the questionnaire as a key tool in personality research.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the use of questionnaires expanded into other fields, including market research, public opinion polling, and health surveys. With the rise of computer technology, questionnaires became easier and more cost-effective to administer, leading to their widespread use in research and business settings.

Today, questionnaires are used in a wide range of settings, including academic research, business, healthcare, and government. They continue to evolve as a research tool, with advances in computer technology and data analysis techniques making it easier to collect and analyze data from large numbers of participants.

Types of Questionnaire

Types of Questionnaires are as follows:

Structured Questionnaire

This type of questionnaire has a fixed format with predetermined questions that the respondent must answer. The questions are usually closed-ended, which means that the respondent must select a response from a list of options.

Unstructured Questionnaire

An unstructured questionnaire does not have a fixed format or predetermined questions. Instead, the interviewer or researcher can ask open-ended questions to the respondent and let them provide their own answers.

Open-ended Questionnaire

An open-ended questionnaire allows the respondent to answer the question in their own words, without any pre-determined response options. The questions usually start with phrases like “how,” “why,” or “what,” and encourage the respondent to provide more detailed and personalized answers.

Close-ended Questionnaire

In a closed-ended questionnaire, the respondent is given a set of predetermined response options to choose from. This type of questionnaire is easier to analyze and summarize, but may not provide as much insight into the respondent’s opinions or attitudes.

Mixed Questionnaire

A mixed questionnaire is a combination of open-ended and closed-ended questions. This type of questionnaire allows for more flexibility in terms of the questions that can be asked, and can provide both quantitative and qualitative data.

Pictorial Questionnaire:

In a pictorial questionnaire, instead of using words to ask questions, the questions are presented in the form of pictures, diagrams or images. This can be particularly useful for respondents who have low literacy skills, or for situations where language barriers exist. Pictorial questionnaires can also be useful in cross-cultural research where respondents may come from different language backgrounds.

Types of Questions in Questionnaire

The types of Questions in Questionnaire are as follows:

Multiple Choice Questions

These questions have several options for participants to choose from. They are useful for getting quantitative data and can be used to collect demographic information.

- a. Red b . Blue c. Green d . Yellow

Rating Scale Questions

These questions ask participants to rate something on a scale (e.g. from 1 to 10). They are useful for measuring attitudes and opinions.

- On a scale of 1 to 10, how likely are you to recommend this product to a friend?

Open-Ended Questions

These questions allow participants to answer in their own words and provide more in-depth and detailed responses. They are useful for getting qualitative data.

- What do you think are the biggest challenges facing your community?

Likert Scale Questions

These questions ask participants to rate how much they agree or disagree with a statement. They are useful for measuring attitudes and opinions.

How strongly do you agree or disagree with the following statement:

“I enjoy exercising regularly.”

- a . Strongly Agree

- c . Neither Agree nor Disagree

- d . Disagree

- e . Strongly Disagree

Demographic Questions

These questions ask about the participant’s personal information such as age, gender, ethnicity, education level, etc. They are useful for segmenting the data and analyzing results by demographic groups.

- What is your age?

Yes/No Questions

These questions only have two options: Yes or No. They are useful for getting simple, straightforward answers to a specific question.

Have you ever traveled outside of your home country?

Ranking Questions

These questions ask participants to rank several items in order of preference or importance. They are useful for measuring priorities or preferences.

Please rank the following factors in order of importance when choosing a restaurant:

- a. Quality of Food

- c. Ambiance

- d. Location

Matrix Questions

These questions present a matrix or grid of options that participants can choose from. They are useful for getting data on multiple variables at once.

Dichotomous Questions

These questions present two options that are opposite or contradictory. They are useful for measuring binary or polarized attitudes.

Do you support the death penalty?

How to Make a Questionnaire

Step-by-Step Guide for Making a Questionnaire:

- Define your research objectives: Before you start creating questions, you need to define the purpose of your questionnaire and what you hope to achieve from the data you collect.

- Choose the appropriate question types: Based on your research objectives, choose the appropriate question types to collect the data you need. Refer to the types of questions mentioned earlier for guidance.

- Develop questions: Develop clear and concise questions that are easy for participants to understand. Avoid leading or biased questions that might influence the responses.

- Organize questions: Organize questions in a logical and coherent order, starting with demographic questions followed by general questions, and ending with specific or sensitive questions.

- Pilot the questionnaire : Test your questionnaire on a small group of participants to identify any flaws or issues with the questions or the format.

- Refine the questionnaire : Based on feedback from the pilot, refine and revise the questionnaire as necessary to ensure that it is valid and reliable.

- Distribute the questionnaire: Distribute the questionnaire to your target audience using a method that is appropriate for your research objectives, such as online surveys, email, or paper surveys.

- Collect and analyze data: Collect the completed questionnaires and analyze the data using appropriate statistical methods. Draw conclusions from the data and use them to inform decision-making or further research.

- Report findings: Present your findings in a clear and concise report, including a summary of the research objectives, methodology, key findings, and recommendations.

Questionnaire Administration Modes

There are several modes of questionnaire administration. The choice of mode depends on the research objectives, sample size, and available resources. Some common modes of administration include:

- Self-administered paper questionnaires: Participants complete the questionnaire on paper, either in person or by mail. This mode is relatively low cost and easy to administer, but it may result in lower response rates and greater potential for errors in data entry.

- Online questionnaires: Participants complete the questionnaire on a website or through email. This mode is convenient for both researchers and participants, as it allows for fast and easy data collection. However, it may be subject to issues such as low response rates, lack of internet access, and potential for fraudulent responses.

- Telephone surveys: Trained interviewers administer the questionnaire over the phone. This mode allows for a large sample size and can result in higher response rates, but it is also more expensive and time-consuming than other modes.

- Face-to-face interviews : Trained interviewers administer the questionnaire in person. This mode allows for a high degree of control over the survey environment and can result in higher response rates, but it is also more expensive and time-consuming than other modes.

- Mixed-mode surveys: Researchers use a combination of two or more modes to administer the questionnaire, such as using online questionnaires for initial screening and following up with telephone interviews for more detailed information. This mode can help overcome some of the limitations of individual modes, but it requires careful planning and coordination.

Example of Questionnaire

Title of the Survey: Customer Satisfaction Survey

Introduction:

We appreciate your business and would like to ensure that we are meeting your needs. Please take a few minutes to complete this survey so that we can better understand your experience with our products and services. Your feedback is important to us and will help us improve our offerings.

Instructions:

Please read each question carefully and select the response that best reflects your experience. If you have any additional comments or suggestions, please feel free to include them in the space provided at the end of the survey.

1. How satisfied are you with our product quality?

- Very satisfied

- Somewhat satisfied

- Somewhat dissatisfied

- Very dissatisfied

2. How satisfied are you with our customer service?

3. How satisfied are you with the price of our products?

4. How likely are you to recommend our products to others?

- Very likely

- Somewhat likely

- Somewhat unlikely

- Very unlikely

5. How easy was it to find the information you were looking for on our website?

- Somewhat easy

- Somewhat difficult

- Very difficult

6. How satisfied are you with the overall experience of using our products and services?

7. Is there anything that you would like to see us improve upon or change in the future?

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Conclusion:

Thank you for taking the time to complete this survey. Your feedback is valuable to us and will help us improve our products and services. If you have any further comments or concerns, please do not hesitate to contact us.

Applications of Questionnaire

Some common applications of questionnaires include:

- Research : Questionnaires are commonly used in research to gather information from participants about their attitudes, opinions, behaviors, and experiences. This information can then be analyzed and used to draw conclusions and make inferences.

- Healthcare : In healthcare, questionnaires can be used to gather information about patients’ medical history, symptoms, and lifestyle habits. This information can help healthcare professionals diagnose and treat medical conditions more effectively.

- Marketing : Questionnaires are commonly used in marketing to gather information about consumers’ preferences, buying habits, and opinions on products and services. This information can help businesses develop and market products more effectively.

- Human Resources: Questionnaires are used in human resources to gather information from job applicants, employees, and managers about job satisfaction, performance, and workplace culture. This information can help organizations improve their hiring practices, employee retention, and organizational culture.

- Education : Questionnaires are used in education to gather information from students, teachers, and parents about their perceptions of the educational experience. This information can help educators identify areas for improvement and develop more effective teaching strategies.

Purpose of Questionnaire

Some common purposes of questionnaires include:

- To collect information on attitudes, opinions, and beliefs: Questionnaires can be used to gather information on people’s attitudes, opinions, and beliefs on a particular topic. For example, a questionnaire can be used to gather information on people’s opinions about a particular political issue.

- To collect demographic information: Questionnaires can be used to collect demographic information such as age, gender, income, education level, and occupation. This information can be used to analyze trends and patterns in the data.

- To measure behaviors or experiences: Questionnaires can be used to gather information on behaviors or experiences such as health-related behaviors or experiences, job satisfaction, or customer satisfaction.

- To evaluate programs or interventions: Questionnaires can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of programs or interventions by gathering information on participants’ experiences, opinions, and behaviors.

- To gather information for research: Questionnaires can be used to gather data for research purposes on a variety of topics.

When to use Questionnaire

Here are some situations when questionnaires might be used:

- When you want to collect data from a large number of people: Questionnaires are useful when you want to collect data from a large number of people. They can be distributed to a wide audience and can be completed at the respondent’s convenience.

- When you want to collect data on specific topics: Questionnaires are useful when you want to collect data on specific topics or research questions. They can be designed to ask specific questions and can be used to gather quantitative data that can be analyzed statistically.

- When you want to compare responses across groups: Questionnaires are useful when you want to compare responses across different groups of people. For example, you might want to compare responses from men and women, or from people of different ages or educational backgrounds.

- When you want to collect data anonymously: Questionnaires can be useful when you want to collect data anonymously. Respondents can complete the questionnaire without fear of judgment or repercussions, which can lead to more honest and accurate responses.

- When you want to save time and resources: Questionnaires can be more efficient and cost-effective than other methods of data collection such as interviews or focus groups. They can be completed quickly and easily, and can be analyzed using software to save time and resources.

Characteristics of Questionnaire

Here are some of the characteristics of questionnaires:

- Standardization : Questionnaires are standardized tools that ask the same questions in the same order to all respondents. This ensures that all respondents are answering the same questions and that the responses can be compared and analyzed.

- Objectivity : Questionnaires are designed to be objective, meaning that they do not contain leading questions or bias that could influence the respondent’s answers.

- Predefined responses: Questionnaires typically provide predefined response options for the respondents to choose from, which helps to standardize the responses and make them easier to analyze.

- Quantitative data: Questionnaires are designed to collect quantitative data, meaning that they provide numerical or categorical data that can be analyzed using statistical methods.

- Convenience : Questionnaires are convenient for both the researcher and the respondents. They can be distributed and completed at the respondent’s convenience and can be easily administered to a large number of people.

- Anonymity : Questionnaires can be anonymous, which can encourage respondents to answer more honestly and provide more accurate data.

- Reliability : Questionnaires are designed to be reliable, meaning that they produce consistent results when administered multiple times to the same group of people.

- Validity : Questionnaires are designed to be valid, meaning that they measure what they are intended to measure and are not influenced by other factors.

Advantage of Questionnaire

Some Advantage of Questionnaire are as follows:

- Standardization: Questionnaires allow researchers to ask the same questions to all participants in a standardized manner. This helps ensure consistency in the data collected and eliminates potential bias that might arise if questions were asked differently to different participants.

- Efficiency: Questionnaires can be administered to a large number of people at once, making them an efficient way to collect data from a large sample.

- Anonymity: Participants can remain anonymous when completing a questionnaire, which may make them more likely to answer honestly and openly.

- Cost-effective: Questionnaires can be relatively inexpensive to administer compared to other research methods, such as interviews or focus groups.

- Objectivity: Because questionnaires are typically designed to collect quantitative data, they can be analyzed objectively without the influence of the researcher’s subjective interpretation.

- Flexibility: Questionnaires can be adapted to a wide range of research questions and can be used in various settings, including online surveys, mail surveys, or in-person interviews.

Limitations of Questionnaire

Limitations of Questionnaire are as follows:

- Limited depth: Questionnaires are typically designed to collect quantitative data, which may not provide a complete understanding of the topic being studied. Questionnaires may miss important details and nuances that could be captured through other research methods, such as interviews or observations.

- R esponse bias: Participants may not always answer questions truthfully or accurately, either because they do not remember or because they want to present themselves in a particular way. This can lead to response bias, which can affect the validity and reliability of the data collected.

- Limited flexibility: While questionnaires can be adapted to a wide range of research questions, they may not be suitable for all types of research. For example, they may not be appropriate for studying complex phenomena or for exploring participants’ experiences and perceptions in-depth.

- Limited context: Questionnaires typically do not provide a rich contextual understanding of the topic being studied. They may not capture the broader social, cultural, or historical factors that may influence participants’ responses.

- Limited control : Researchers may not have control over how participants complete the questionnaire, which can lead to variations in response quality or consistency.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Qualitative Research Methods

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

Survey Research – Types, Methods, Examples

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Writing Survey Questions

Perhaps the most important part of the survey process is the creation of questions that accurately measure the opinions, experiences and behaviors of the public. Accurate random sampling will be wasted if the information gathered is built on a shaky foundation of ambiguous or biased questions. Creating good measures involves both writing good questions and organizing them to form the questionnaire.

Questionnaire design is a multistage process that requires attention to many details at once. Designing the questionnaire is complicated because surveys can ask about topics in varying degrees of detail, questions can be asked in different ways, and questions asked earlier in a survey may influence how people respond to later questions. Researchers are also often interested in measuring change over time and therefore must be attentive to how opinions or behaviors have been measured in prior surveys.

Surveyors may conduct pilot tests or focus groups in the early stages of questionnaire development in order to better understand how people think about an issue or comprehend a question. Pretesting a survey is an essential step in the questionnaire design process to evaluate how people respond to the overall questionnaire and specific questions, especially when questions are being introduced for the first time.

For many years, surveyors approached questionnaire design as an art, but substantial research over the past forty years has demonstrated that there is a lot of science involved in crafting a good survey questionnaire. Here, we discuss the pitfalls and best practices of designing questionnaires.

Question development

There are several steps involved in developing a survey questionnaire. The first is identifying what topics will be covered in the survey. For Pew Research Center surveys, this involves thinking about what is happening in our nation and the world and what will be relevant to the public, policymakers and the media. We also track opinion on a variety of issues over time so we often ensure that we update these trends on a regular basis to better understand whether people’s opinions are changing.

At Pew Research Center, questionnaire development is a collaborative and iterative process where staff meet to discuss drafts of the questionnaire several times over the course of its development. We frequently test new survey questions ahead of time through qualitative research methods such as focus groups , cognitive interviews, pretesting (often using an online, opt-in sample ), or a combination of these approaches. Researchers use insights from this testing to refine questions before they are asked in a production survey, such as on the ATP.

Measuring change over time

Many surveyors want to track changes over time in people’s attitudes, opinions and behaviors. To measure change, questions are asked at two or more points in time. A cross-sectional design surveys different people in the same population at multiple points in time. A panel, such as the ATP, surveys the same people over time. However, it is common for the set of people in survey panels to change over time as new panelists are added and some prior panelists drop out. Many of the questions in Pew Research Center surveys have been asked in prior polls. Asking the same questions at different points in time allows us to report on changes in the overall views of the general public (or a subset of the public, such as registered voters, men or Black Americans), or what we call “trending the data”.

When measuring change over time, it is important to use the same question wording and to be sensitive to where the question is asked in the questionnaire to maintain a similar context as when the question was asked previously (see question wording and question order for further information). All of our survey reports include a topline questionnaire that provides the exact question wording and sequencing, along with results from the current survey and previous surveys in which we asked the question.

The Center’s transition from conducting U.S. surveys by live telephone interviewing to an online panel (around 2014 to 2020) complicated some opinion trends, but not others. Opinion trends that ask about sensitive topics (e.g., personal finances or attending religious services ) or that elicited volunteered answers (e.g., “neither” or “don’t know”) over the phone tended to show larger differences than other trends when shifting from phone polls to the online ATP. The Center adopted several strategies for coping with changes to data trends that may be related to this change in methodology. If there is evidence suggesting that a change in a trend stems from switching from phone to online measurement, Center reports flag that possibility for readers to try to head off confusion or erroneous conclusions.

Open- and closed-ended questions

One of the most significant decisions that can affect how people answer questions is whether the question is posed as an open-ended question, where respondents provide a response in their own words, or a closed-ended question, where they are asked to choose from a list of answer choices.

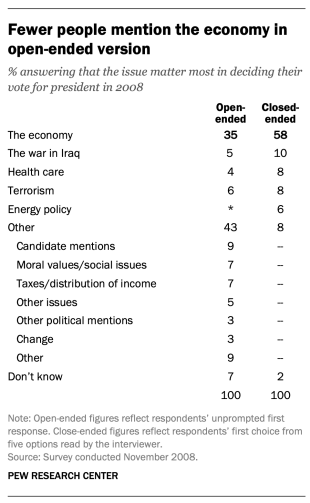

For example, in a poll conducted after the 2008 presidential election, people responded very differently to two versions of the question: “What one issue mattered most to you in deciding how you voted for president?” One was closed-ended and the other open-ended. In the closed-ended version, respondents were provided five options and could volunteer an option not on the list.

When explicitly offered the economy as a response, more than half of respondents (58%) chose this answer; only 35% of those who responded to the open-ended version volunteered the economy. Moreover, among those asked the closed-ended version, fewer than one-in-ten (8%) provided a response other than the five they were read. By contrast, fully 43% of those asked the open-ended version provided a response not listed in the closed-ended version of the question. All of the other issues were chosen at least slightly more often when explicitly offered in the closed-ended version than in the open-ended version. (Also see “High Marks for the Campaign, a High Bar for Obama” for more information.)

Researchers will sometimes conduct a pilot study using open-ended questions to discover which answers are most common. They will then develop closed-ended questions based off that pilot study that include the most common responses as answer choices. In this way, the questions may better reflect what the public is thinking, how they view a particular issue, or bring certain issues to light that the researchers may not have been aware of.

When asking closed-ended questions, the choice of options provided, how each option is described, the number of response options offered, and the order in which options are read can all influence how people respond. One example of the impact of how categories are defined can be found in a Pew Research Center poll conducted in January 2002. When half of the sample was asked whether it was “more important for President Bush to focus on domestic policy or foreign policy,” 52% chose domestic policy while only 34% said foreign policy. When the category “foreign policy” was narrowed to a specific aspect – “the war on terrorism” – far more people chose it; only 33% chose domestic policy while 52% chose the war on terrorism.

In most circumstances, the number of answer choices should be kept to a relatively small number – just four or perhaps five at most – especially in telephone surveys. Psychological research indicates that people have a hard time keeping more than this number of choices in mind at one time. When the question is asking about an objective fact and/or demographics, such as the religious affiliation of the respondent, more categories can be used. In fact, they are encouraged to ensure inclusivity. For example, Pew Research Center’s standard religion questions include more than 12 different categories, beginning with the most common affiliations (Protestant and Catholic). Most respondents have no trouble with this question because they can expect to see their religious group within that list in a self-administered survey.

In addition to the number and choice of response options offered, the order of answer categories can influence how people respond to closed-ended questions. Research suggests that in telephone surveys respondents more frequently choose items heard later in a list (a “recency effect”), and in self-administered surveys, they tend to choose items at the top of the list (a “primacy” effect).

Because of concerns about the effects of category order on responses to closed-ended questions, many sets of response options in Pew Research Center’s surveys are programmed to be randomized to ensure that the options are not asked in the same order for each respondent. Rotating or randomizing means that questions or items in a list are not asked in the same order to each respondent. Answers to questions are sometimes affected by questions that precede them. By presenting questions in a different order to each respondent, we ensure that each question gets asked in the same context as every other question the same number of times (e.g., first, last or any position in between). This does not eliminate the potential impact of previous questions on the current question, but it does ensure that this bias is spread randomly across all of the questions or items in the list. For instance, in the example discussed above about what issue mattered most in people’s vote, the order of the five issues in the closed-ended version of the question was randomized so that no one issue appeared early or late in the list for all respondents. Randomization of response items does not eliminate order effects, but it does ensure that this type of bias is spread randomly.

Questions with ordinal response categories – those with an underlying order (e.g., excellent, good, only fair, poor OR very favorable, mostly favorable, mostly unfavorable, very unfavorable) – are generally not randomized because the order of the categories conveys important information to help respondents answer the question. Generally, these types of scales should be presented in order so respondents can easily place their responses along the continuum, but the order can be reversed for some respondents. For example, in one of Pew Research Center’s questions about abortion, half of the sample is asked whether abortion should be “legal in all cases, legal in most cases, illegal in most cases, illegal in all cases,” while the other half of the sample is asked the same question with the response categories read in reverse order, starting with “illegal in all cases.” Again, reversing the order does not eliminate the recency effect but distributes it randomly across the population.

Question wording

The choice of words and phrases in a question is critical in expressing the meaning and intent of the question to the respondent and ensuring that all respondents interpret the question the same way. Even small wording differences can substantially affect the answers people provide.

[View more Methods 101 Videos ]

An example of a wording difference that had a significant impact on responses comes from a January 2003 Pew Research Center survey. When people were asked whether they would “favor or oppose taking military action in Iraq to end Saddam Hussein’s rule,” 68% said they favored military action while 25% said they opposed military action. However, when asked whether they would “favor or oppose taking military action in Iraq to end Saddam Hussein’s rule even if it meant that U.S. forces might suffer thousands of casualties, ” responses were dramatically different; only 43% said they favored military action, while 48% said they opposed it. The introduction of U.S. casualties altered the context of the question and influenced whether people favored or opposed military action in Iraq.

There has been a substantial amount of research to gauge the impact of different ways of asking questions and how to minimize differences in the way respondents interpret what is being asked. The issues related to question wording are more numerous than can be treated adequately in this short space, but below are a few of the important things to consider:

First, it is important to ask questions that are clear and specific and that each respondent will be able to answer. If a question is open-ended, it should be evident to respondents that they can answer in their own words and what type of response they should provide (an issue or problem, a month, number of days, etc.). Closed-ended questions should include all reasonable responses (i.e., the list of options is exhaustive) and the response categories should not overlap (i.e., response options should be mutually exclusive). Further, it is important to discern when it is best to use forced-choice close-ended questions (often denoted with a radio button in online surveys) versus “select-all-that-apply” lists (or check-all boxes). A 2019 Center study found that forced-choice questions tend to yield more accurate responses, especially for sensitive questions. Based on that research, the Center generally avoids using select-all-that-apply questions.

It is also important to ask only one question at a time. Questions that ask respondents to evaluate more than one concept (known as double-barreled questions) – such as “How much confidence do you have in President Obama to handle domestic and foreign policy?” – are difficult for respondents to answer and often lead to responses that are difficult to interpret. In this example, it would be more effective to ask two separate questions, one about domestic policy and another about foreign policy.

In general, questions that use simple and concrete language are more easily understood by respondents. It is especially important to consider the education level of the survey population when thinking about how easy it will be for respondents to interpret and answer a question. Double negatives (e.g., do you favor or oppose not allowing gays and lesbians to legally marry) or unfamiliar abbreviations or jargon (e.g., ANWR instead of Arctic National Wildlife Refuge) can result in respondent confusion and should be avoided.

Similarly, it is important to consider whether certain words may be viewed as biased or potentially offensive to some respondents, as well as the emotional reaction that some words may provoke. For example, in a 2005 Pew Research Center survey, 51% of respondents said they favored “making it legal for doctors to give terminally ill patients the means to end their lives,” but only 44% said they favored “making it legal for doctors to assist terminally ill patients in committing suicide.” Although both versions of the question are asking about the same thing, the reaction of respondents was different. In another example, respondents have reacted differently to questions using the word “welfare” as opposed to the more generic “assistance to the poor.” Several experiments have shown that there is much greater public support for expanding “assistance to the poor” than for expanding “welfare.”

We often write two versions of a question and ask half of the survey sample one version of the question and the other half the second version. Thus, we say we have two forms of the questionnaire. Respondents are assigned randomly to receive either form, so we can assume that the two groups of respondents are essentially identical. On questions where two versions are used, significant differences in the answers between the two forms tell us that the difference is a result of the way we worded the two versions.

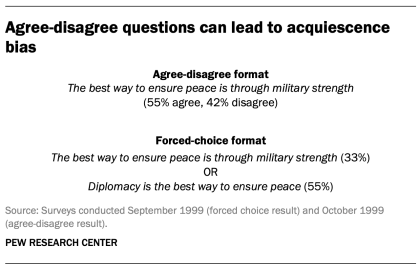

One of the most common formats used in survey questions is the “agree-disagree” format. In this type of question, respondents are asked whether they agree or disagree with a particular statement. Research has shown that, compared with the better educated and better informed, less educated and less informed respondents have a greater tendency to agree with such statements. This is sometimes called an “acquiescence bias” (since some kinds of respondents are more likely to acquiesce to the assertion than are others). This behavior is even more pronounced when there’s an interviewer present, rather than when the survey is self-administered. A better practice is to offer respondents a choice between alternative statements. A Pew Research Center experiment with one of its routinely asked values questions illustrates the difference that question format can make. Not only does the forced choice format yield a very different result overall from the agree-disagree format, but the pattern of answers between respondents with more or less formal education also tends to be very different.

One other challenge in developing questionnaires is what is called “social desirability bias.” People have a natural tendency to want to be accepted and liked, and this may lead people to provide inaccurate answers to questions that deal with sensitive subjects. Research has shown that respondents understate alcohol and drug use, tax evasion and racial bias. They also may overstate church attendance, charitable contributions and the likelihood that they will vote in an election. Researchers attempt to account for this potential bias in crafting questions about these topics. For instance, when Pew Research Center surveys ask about past voting behavior, it is important to note that circumstances may have prevented the respondent from voting: “In the 2012 presidential election between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney, did things come up that kept you from voting, or did you happen to vote?” The choice of response options can also make it easier for people to be honest. For example, a question about church attendance might include three of six response options that indicate infrequent attendance. Research has also shown that social desirability bias can be greater when an interviewer is present (e.g., telephone and face-to-face surveys) than when respondents complete the survey themselves (e.g., paper and web surveys).

Lastly, because slight modifications in question wording can affect responses, identical question wording should be used when the intention is to compare results to those from earlier surveys. Similarly, because question wording and responses can vary based on the mode used to survey respondents, researchers should carefully evaluate the likely effects on trend measurements if a different survey mode will be used to assess change in opinion over time.

Question order

Once the survey questions are developed, particular attention should be paid to how they are ordered in the questionnaire. Surveyors must be attentive to how questions early in a questionnaire may have unintended effects on how respondents answer subsequent questions. Researchers have demonstrated that the order in which questions are asked can influence how people respond; earlier questions can unintentionally provide context for the questions that follow (these effects are called “order effects”).

One kind of order effect can be seen in responses to open-ended questions. Pew Research Center surveys generally ask open-ended questions about national problems, opinions about leaders and similar topics near the beginning of the questionnaire. If closed-ended questions that relate to the topic are placed before the open-ended question, respondents are much more likely to mention concepts or considerations raised in those earlier questions when responding to the open-ended question.

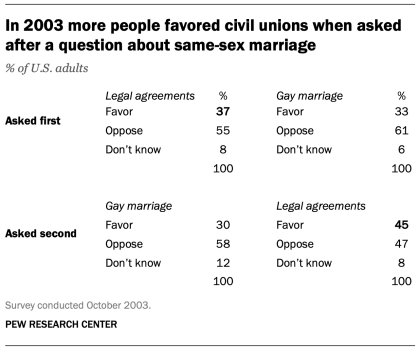

For closed-ended opinion questions, there are two main types of order effects: contrast effects ( where the order results in greater differences in responses), and assimilation effects (where responses are more similar as a result of their order).

An example of a contrast effect can be seen in a Pew Research Center poll conducted in October 2003, a dozen years before same-sex marriage was legalized in the U.S. That poll found that people were more likely to favor allowing gays and lesbians to enter into legal agreements that give them the same rights as married couples when this question was asked after one about whether they favored or opposed allowing gays and lesbians to marry (45% favored legal agreements when asked after the marriage question, but 37% favored legal agreements without the immediate preceding context of a question about same-sex marriage). Responses to the question about same-sex marriage, meanwhile, were not significantly affected by its placement before or after the legal agreements question.

Another experiment embedded in a December 2008 Pew Research Center poll also resulted in a contrast effect. When people were asked “All in all, are you satisfied or dissatisfied with the way things are going in this country today?” immediately after having been asked “Do you approve or disapprove of the way George W. Bush is handling his job as president?”; 88% said they were dissatisfied, compared with only 78% without the context of the prior question.

Responses to presidential approval remained relatively unchanged whether national satisfaction was asked before or after it. A similar finding occurred in December 2004 when both satisfaction and presidential approval were much higher (57% were dissatisfied when Bush approval was asked first vs. 51% when general satisfaction was asked first).

Several studies also have shown that asking a more specific question before a more general question (e.g., asking about happiness with one’s marriage before asking about one’s overall happiness) can result in a contrast effect. Although some exceptions have been found, people tend to avoid redundancy by excluding the more specific question from the general rating.

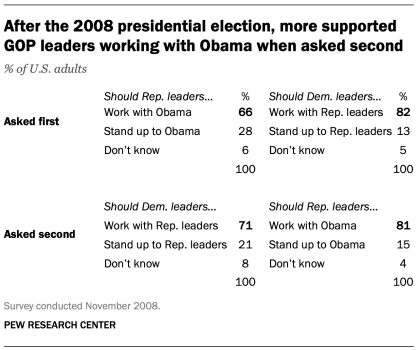

Assimilation effects occur when responses to two questions are more consistent or closer together because of their placement in the questionnaire. We found an example of an assimilation effect in a Pew Research Center poll conducted in November 2008 when we asked whether Republican leaders should work with Obama or stand up to him on important issues and whether Democratic leaders should work with Republican leaders or stand up to them on important issues. People were more likely to say that Republican leaders should work with Obama when the question was preceded by the one asking what Democratic leaders should do in working with Republican leaders (81% vs. 66%). However, when people were first asked about Republican leaders working with Obama, fewer said that Democratic leaders should work with Republican leaders (71% vs. 82%).

The order questions are asked is of particular importance when tracking trends over time. As a result, care should be taken to ensure that the context is similar each time a question is asked. Modifying the context of the question could call into question any observed changes over time (see measuring change over time for more information).

A questionnaire, like a conversation, should be grouped by topic and unfold in a logical order. It is often helpful to begin the survey with simple questions that respondents will find interesting and engaging. Throughout the survey, an effort should be made to keep the survey interesting and not overburden respondents with several difficult questions right after one another. Demographic questions such as income, education or age should not be asked near the beginning of a survey unless they are needed to determine eligibility for the survey or for routing respondents through particular sections of the questionnaire. Even then, it is best to precede such items with more interesting and engaging questions. One virtue of survey panels like the ATP is that demographic questions usually only need to be asked once a year, not in each survey.

U.S. Surveys

Other research methods, sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Fresh data delivered Saturday mornings

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

A strong analytical question

- speaks to a genuine dilemma presented by your sources . In other words, the question focuses on a real confusion, problem, ambiguity, or gray area, about which readers will conceivably have different reactions, opinions, or ideas.

- yields an answer that is not obvious . If you ask, "What did this author say about this topic?” there’s nothing to explore because any reader of that text would answer that question in the same way. But if you ask, “how can we reconcile point A and point B in this text,” readers will want to see how you solve that inconsistency in your essay.

- suggests an answer complex enough to require a whole essay's worth of discussion. If the question is too vague, it won't suggest a line of argument. The question should elicit reflection and argument rather than summary or description.

- can be explored using the sources you have available for the assignment , rather than by generalizations or by research beyond the scope of your assignment.

How to come up with an analytical question

One useful starting point when you’re trying to identify an analytical question is to look for points of tension in your sources, either within one source or among sources. It can be helpful to think of those points of tension as the moments where you need to stop and think before you can move forward. Here are some examples of where you may find points of tension:

- You may read a published view that doesn’t seem convincing to you, and you may want to ask a question about what’s missing or about how the evidence might be reconsidered.

- You may notice an inconsistency, gap, or ambiguity in the evidence, and you may want to explore how that changes your understanding of something.

- You may identify an unexpected wrinkle that you think deserves more attention, and you may want to ask a question about it.

- You may notice an unexpected conclusion that you think doesn’t quite add up, and you may want to ask how the authors of a source reached that conclusion.

- You may identify a controversy that you think needs to be addressed, and you may want to ask a question about how it might be resolved.

- You may notice a problem that you think has been ignored, and you may want to try to solve it or consider why it has been ignored.

- You may encounter a piece of evidence that you think warrants a closer look, and you may raise questions about it.

Once you’ve identified a point of tension and raised a question about it, you will try to answer that question in your essay. Your main idea or claim in answer to that question will be your thesis.

- "How" and "why" questions generally require more analysis than "who/ what/when/where” questions.

- Good analytical questions can highlight patterns/connections, or contradictions/dilemmas/problems.

- Good analytical questions establish the scope of an argument, allowing you to focus on a manageable part of a broad topic or a collection of sources.

- Good analytical questions can also address implications or consequences of your analysis.

- picture_as_pdf Asking Analytical Questions

Essay writing: Analysing questions

- Introductions

- Conclusions

- Analysing questions

- Planning & drafting

- Revising & editing

- Proofreading

- Essay writing videos

Jump to content on this page:

“It is well worth the time to break down the question into its different elements.” Kathleen McMillan & Jonathan Weyers, How to Write Essays & Assignments

When you get an essay question, how do you make sure you are answering it how your tutor wants? There is a hidden code in most questions that gives you a clue about the approach you should be taking...

Decoding the question

Here is a typical essay question:

Analyse the impact of the employability agenda on the undergraduate student experience.

Let's decode it...

Understanding the instruction words

Did you know that analyse means something different to discuss or evaluate ? In academic writing these have very specific and unique meanings - which you need to make sure you are aware of before you start your essay planning. For example:

Examine critically so as to bring out the essential elements; describe in detail; describe the various parts of something and explain how they work together, or whether they work together.

It is almost impossible to remember the different meanings, so download our Glossary of Instruction Words for Essay Questions to keep your own reminder of the most common ones.

Redundant phrases

Don't get thrown by other regularly used phrases such as "with reference to relevant literature" or "critically evaluate" and "critically analyse" (rather than simply "evaluate" or "analyse"). All your writing should refer to relevant literature and all writing should have an element of criticality at university level. These are just redundant phrases/words and only there as a gentle reminder.

Recognise the subject of the question

Many students think this is the easy bit - but you can easily mistake the focus for the subject and vice versa. The subject is the general topic of the essay and the instruction word is usually referring to something you must do to that topic .

Usually, the subject is something you have had a lecture about or there are chapters about in your key texts.

There will be many aspects of the subject/topic that you will not need to include in your essay, which is why it is important to recognise and stick to the focus as shown in the next box.

Identify the focus/constraint

Every essay has and needs a focus . If you were to write everything about a topic, even about a particular aspect of a topic, you could write a book and not an essay! The focus gives you direction about the scope of the essay. It usually does one of two things:

- Gives context (focus on the topic within a particular situation, time frame etc).

This could be something there were a few slides about in your lecture or a subheading in your key text.

I don't have an essay question - what do I do?

I have to make up my own title.

If you have been asked to come up with your own title, write one like the ones described here. Include at least an instruction, a subject and a focus and it will make planning and writing the essay so much easier. The main difference would be that you write it as a description rather than a question i.e.:

An analysis of the impact of the employability agenda on the undergraduate student experience.

I have only been given assignment criteria

If you have been given assignment criteria, the question often still contains the information you need to break it down into the components on this page. For example, look at the criteria below. There are still instruction words, subjects and focus/constraints.

Aims of the assignment (3000 words):

An understanding of learning theories is important to being an effective teacher. In this assignment you will select two learning theories and explain why they would help you in your own teaching context. You will then reflect on an experience from your teaching practice when this was, or could have been, put into practice.

Assignment criteria

Select two learning theories , referring to published literature, explain why they are relevant to your own teaching context.

Reflect on an experience from your teaching practice .

Explain why a knowledge of a learning theory was or would have been useful in the circumstances .

- Instructions words = explain (twice); reflect on.

- Subjects = two learning theories; an experience from your teaching practice; knowledge of a learning theory.

- Focus/constraints = your own teaching context; in the circumstances

Think of each criterion therefore as a mini essay.

- << Previous: Formatting

- Next: Planning & drafting >>

- Last Updated: Nov 3, 2023 3:17 PM

- URL: https://libguides.hull.ac.uk/essays

- Login to LibApps

- Library websites Privacy Policy

- University of Hull privacy policy & cookies

- Website terms and conditions

- Accessibility

- Report a problem

Root out friction in every digital experience, super-charge conversion rates, and optimize digital self-service

Uncover insights from any interaction, deliver AI-powered agent coaching, and reduce cost to serve

Increase revenue and loyalty with real-time insights and recommendations delivered to teams on the ground

Know how your people feel and empower managers to improve employee engagement, productivity, and retention

Take action in the moments that matter most along the employee journey and drive bottom line growth

Whatever they’re are saying, wherever they’re saying it, know exactly what’s going on with your people

Get faster, richer insights with qual and quant tools that make powerful market research available to everyone

Run concept tests, pricing studies, prototyping + more with fast, powerful studies designed by UX research experts

Track your brand performance 24/7 and act quickly to respond to opportunities and challenges in your market

Explore the platform powering Experience Management

- Free Account

- For Digital

- For Customer Care

- For Human Resources

- For Researchers

- Financial Services

- All Industries

Popular Use Cases

- Customer Experience

- Employee Experience

- Employee Exit Interviews

- Net Promoter Score

- Voice of Customer

- Customer Success Hub

- Product Documentation

- Training & Certification

- XM Institute

- Popular Resources

- Customer Stories

Market Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Partnerships

- Marketplace

The annual gathering of the experience leaders at the world’s iconic brands building breakthrough business results, live in Salt Lake City.

- English/AU & NZ

- Español/Europa

- Español/América Latina

- Português Brasileiro

- REQUEST DEMO

Your ultimate guide to questionnaires and how to design a good one

The written questionnaire is the heart and soul of any survey research project. Whether you conduct your survey using an online questionnaire, in person, by email or over the phone, the way you design your questionnaire plays a critical role in shaping the quality of the data and insights that you’ll get from your target audience. Keep reading to get actionable tips.

What is a questionnaire?

A questionnaire is a research tool consisting of a set of questions or other ‘prompts’ to collect data from a set of respondents.

When used in most research, a questionnaire will consist of a number of types of questions (primarily open-ended and closed) in order to gain both quantitative data that can be analyzed to draw conclusions, and qualitative data to provide longer, more specific explanations.

A research questionnaire is often mistaken for a survey - and many people use the term questionnaire and survey, interchangeably.

But that’s incorrect.

Which is what we talk about next.

Get started with our free survey maker with 50+ templates

Survey vs. questionnaire – what’s the difference?

Before we go too much further, let’s consider the differences between surveys and questionnaires.

These two terms are often used interchangeably, but there is an important difference between them.

Survey definition

A survey is the process of collecting data from a set of respondents and using it to gather insights.

Survey research can be conducted using a questionnaire, but won’t always involve one.

Questionnaire definition

A questionnaire is the list of questions you circulate to your target audience.

In other words, the survey is the task you’re carrying out, and the questionnaire is the instrument you’re using to do it.

By itself, a questionnaire doesn’t achieve much.

It’s when you put it into action as part of a survey that you start to get results.

Advantages vs disadvantages of using a questionnaire

While a questionnaire is a popular method to gather data for market research or other studies, there are a few disadvantages to using this method (although there are plenty of advantages to using a questionnaire too).

Let’s have a look at some of the advantages and disadvantages of using a questionnaire for collecting data.

Advantages of using a questionnaire

1. questionnaires are relatively cheap.

Depending on the complexity of your study, using a questionnaire can be cost effective compared to other methods.

You simply need to write your survey questionnaire, and send it out and then process the responses.

You can set up an online questionnaire relatively easily, or simply carry out market research on the street if that’s the best method.

2. You can get and analyze results quickly

Again depending on the size of your survey you can get results back from a questionnaire quickly, often within 24 hours of putting the questionnaire live.

It also means you can start to analyze responses quickly too.

3. They’re easily scalable

You can easily send an online questionnaire to anyone in the world and with the right software you can quickly identify your target audience and your questionnaire to them.

4. Questionnaires are easy to analyze

If your questionnaire design has been done properly, it’s quick and easy to analyze results from questionnaires once responses start to come back.

This is particularly useful with large scale market research projects.

Because all respondents are answering the same questions, it’s simple to identify trends.

5. You can use the results to make accurate decisions

As a research instrument, a questionnaire is ideal for commercial research because the data you get back is from your target audience (or ideal customers) and the information you get back on their thoughts, preferences or behaviors allows you to make business decisions.

6. A questionnaire can cover any topic

One of the biggest advantages of using questionnaires when conducting research is (because you can adapt them using different types and styles of open ended questions and closed ended questions) they can be used to gather data on almost any topic.

There are many types of questionnaires you can design to gather both quantitative data and qualitative data - so they’re a useful tool for all kinds of data analysis.

Disadvantages of using a questionnaire

1. respondents could lie.

This is by far the biggest risk with a questionnaire, especially when dealing with sensitive topics.

Rather than give their actual opinion, a respondent might feel pressured to give the answer they deem more socially acceptable, which doesn’t give you accurate results.

2. Respondents might not answer every question

There are all kinds of reasons respondents might not answer every question, from questionnaire length, they might not understand what’s being asked, or they simply might not want to answer it.

If you get questionnaires back without complete responses it could negatively affect your research data and provide an inaccurate picture.

3. They might interpret what’s being asked incorrectly

This is a particular problem when running a survey across geographical boundaries and often comes down to the design of the survey questionnaire.

If your questions aren’t written in a very clear way, the respondent might misunderstand what’s being asked and provide an answer that doesn’t reflect what they actually think.

Again this can negatively affect your research data.

4. You could introduce bias

The whole point of producing a questionnaire is to gather accurate data from which decisions can be made or conclusions drawn.

But the data collected can be heavily impacted if the researchers accidentally introduce bias into the questions.

This can be easily done if the researcher is trying to prove a certain hypothesis with their questionnaire, and unwittingly write questions that push people towards giving a certain answer.

In these cases respondents’ answers won’t accurately reflect what is really happening and stop you gathering more accurate data.

5. Respondents could get survey fatigue

One issue you can run into when sending out a questionnaire, particularly if you send them out regularly to the same survey sample, is that your respondents could start to suffer from survey fatigue.

In these circumstances, rather than thinking about the response options in the questionnaire and providing accurate answers, respondents could start to just tick boxes to get through the questionnaire quickly.

Again, this won’t give you an accurate data set.

Questionnaire design: How to do it

It’s essential to carefully craft a questionnaire to reduce survey error and optimize your data . The best way to think about the questionnaire is with the end result in mind.

How do you do that?

Start with questions, like:

- What is my research purpose ?

- What data do I need?

- How am I going to analyze that data?

- What questions are needed to best suit these variables?

Once you have a clear idea of the purpose of your survey, you’ll be in a better position to create an effective questionnaire.

Here are a few steps to help you get into the right mindset.

1. Keep the respondent front and center

A survey is the process of collecting information from people, so it needs to be designed around human beings first and foremost.

In his post about survey design theory, David Vannette, PhD, from the Qualtrics Methodology Lab explains the correlation between the way a survey is designed and the quality of data that is extracted.

“To begin designing an effective survey, take a step back and try to understand what goes on in your respondents’ heads when they are taking your survey.

This step is critical to making sure that your questionnaire makes it as likely as possible that the response process follows that expected path.”

From writing the questions to designing the survey flow, the respondent’s point of view should always be front and center in your mind during a questionnaire design.

2. How to write survey questions

Your questionnaire should only be as long as it needs to be, and every question needs to deliver value.

That means your questions must each have an individual purpose and produce the best possible data for that purpose, all while supporting the overall goal of the survey.

A question must also must be phrased in a way that is easy for all your respondents to understand, and does not produce false results.

To do this, remember the following principles:

Get into the respondent's head

The process for a respondent answering a survey question looks like this:

- The respondent reads the question and determines what information they need to answer it.

- They search their memory for that information.

- They make judgments about that information.

- They translate that judgment into one of the answer options you’ve provided. This is the process of taking the data they have and matching that information with the question that’s asked.

When wording questions, make sure the question means the same thing to all respondents. Words should have one meaning, few syllables, and the sentences should have few words.

Only use the words needed to ask your question and not a word more .

Note that it’s important that the respondent understands the intent behind your question.

If they don’t, they may answer a different question and the data can be skewed.

Some contextual help text, either in the introduction to the questionnaire or before the question itself, can help make sure the respondent understands your goals and the scope of your research.

Use mutually exclusive responses

Be sure to make your response categories mutually exclusive.

Consider the question:

What is your age?

Respondents that are 31 years old have two options, as do respondents that are 40 and 55. As a result, it is impossible to predict which category they will choose.

This can distort results and frustrate respondents. It can be easily avoided by making responses mutually exclusive.

The following question is much better:

This question is clear and will give us better results.

Ask specific questions

Nonspecific questions can confuse respondents and influence results.

Do you like orange juice?

- Like very much

- Neither like nor dislike

- Dislike very much

This question is very unclear. Is it asking about taste, texture, price, or the nutritional content? Different respondents will read this question differently.

A specific question will get more specific answers that are actionable.

How much do you like the current price of orange juice?

This question is more specific and will get better results.

If you need to collect responses about more than one aspect of a subject, you can include multiple questions on it. (Do you like the taste of orange juice? Do you like the nutritional content of orange juice? etc.)

Use a variety of question types

If all of your questionnaire, survey or poll questions are structured the same way (e.g. yes/no or multiple choice) the respondents are likely to become bored and tune out. That could mean they pay less attention to how they’re answering or even give up altogether.

Instead, mix up the question types to keep the experience interesting and varied. It’s a good idea to include questions that yield both qualitative and quantitative data.

For example, an open-ended questionnaire item such as “describe your attitude to life” will provide qualitative data – a form of information that’s rich, unstructured and unpredictable. The respondent will tell you in their own words what they think and feel.

A quantitative / close-ended questionnaire item, such as “Which word describes your attitude to life? a) practical b) philosophical” gives you a much more structured answer, but the answers will be less rich and detailed.

Open-ended questions take more thought and effort to answer, so use them sparingly. They also require a different kind of treatment once your survey is in the analysis stage.

3. Pre-test your questionnaire

Always pre-test a questionnaire before sending it out to respondents. This will help catch any errors you might have missed. You could ask a colleague, friend, or an expert to take the survey and give feedback. If possible, ask a few cognitive questions like, “how did you get to that response?” and “what were you thinking about when you answered that question?” Figure out what was easy for the responder and where there is potential for confusion. You can then re-word where necessary to make the experience as frictionless as possible.

If your resources allow, you could also consider using a focus group to test out your survey. Having multiple respondents road-test the questionnaire will give you a better understanding of its strengths and weaknesses. Match the focus group to your target respondents as closely as possible, for example in terms of age, background, gender, and level of education.

Note: Don't forget to make your survey as accessible as possible for increased response rates.

Questionnaire examples and templates

There are free questionnaire templates and example questions available for all kinds of surveys and market research, many of them online. But they’re not all created equal and you should use critical judgement when selecting one. After all, the questionnaire examples may be free but the time and energy you’ll spend carrying out a survey are not.

If you’re using online questionnaire templates as the basis for your own, make sure it has been developed by professionals and is specific to the type of research you’re doing to ensure higher completion rates. As we’ve explored here, using the wrong kinds of questions can result in skewed or messy data, and could even prompt respondents to abandon the questionnaire without finishing or give thoughtless answers.

You’ll find a full library of downloadable survey templates in the Qualtrics Marketplace , covering many different types of research from employee engagement to post-event feedback . All are fully customizable and have been developed by Qualtrics experts.

Qualtrics // Experience Management

Qualtrics, the leader and creator of the experience management category, is a cloud-native software platform that empowers organizations to deliver exceptional experiences and build deep relationships with their customers and employees.

With insights from Qualtrics, organizations can identify and resolve the greatest friction points in their business, retain and engage top talent, and bring the right products and services to market. Nearly 20,000 organizations around the world use Qualtrics’ advanced AI to listen, understand, and take action. Qualtrics uses its vast universe of experience data to form the largest database of human sentiment in the world. Qualtrics is co-headquartered in Provo, Utah and Seattle.

Related Articles

December 20, 2023

Top market research analyst skills for 2024

November 7, 2023

Brand Experience

The 4 market research trends redefining insights in 2024

September 14, 2023

How BMG and Loop use data to make critical decisions

August 21, 2023

Designing for safety: Making user consent and trust an organizational asset

June 27, 2023

The fresh insights people: Scaling research at Woolworths Group

June 20, 2023

Bank less, delight more: How Bankwest built an engine room for customer obsession

June 16, 2023

How Qualtrics Helps Three Local Governments Drive Better Outcomes Through Data Insights

April 1, 2023

Academic Experience

How to write great survey questions (with examples)

Stay up to date with the latest xm thought leadership, tips and news., request demo.

Ready to learn more about Qualtrics?

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

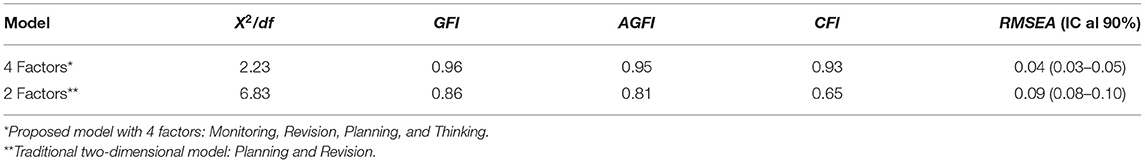

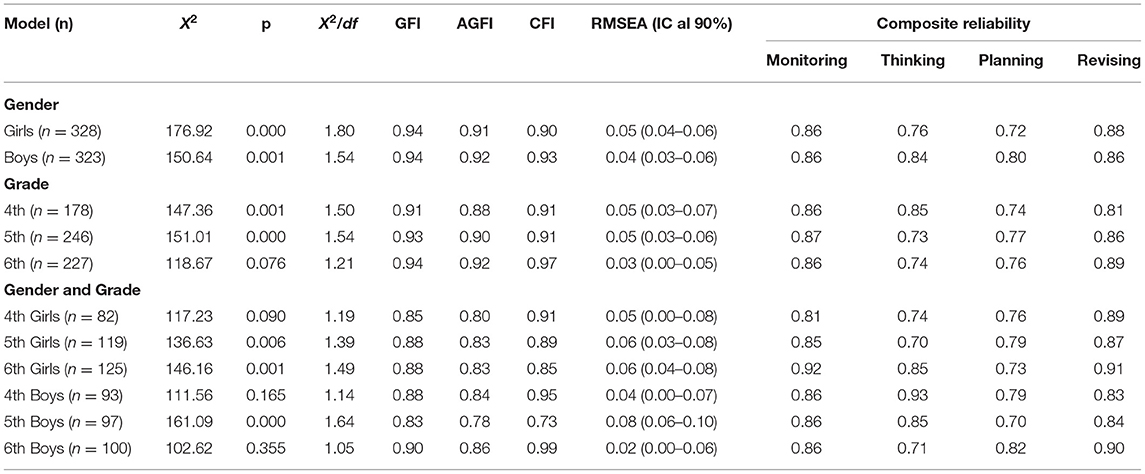

Validation of the writing strategies questionnaire in the context of primary education: a multidimensional measurement model.

- 1 Department of Psychology, Sociology and Philosophy, University of Leon, Leon, Spain

- 2 Ponferrada Associated Centre, National University of Distance Education (UNED), Leon, Spain

- 3 Research Institute for Child Development and Education, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Research has shown that writers seem to follow different writing strategies to juggle the high cognitive demands of writing. The use of writing strategies seems to be an important cognitive writing-related variable which has an influence on students' writing behavior during writing and, therefore, on the quality of their compositions. Several studies have tried to assess students' writing preferences toward the use of different writing strategies in University or high-school students, while research in primary education is practically non-existent. The present study, therefore, focused on the validation of the Spanish Writing Strategies Questionnaire (WSQ-SP), aimed to measure upper-primary students' preference for the use of different writing strategies, through a multidimensional model. The sample comprised 651 Spanish upper-primary students. Questionnaire data was explored by means of exploratory (EFA) and confirmatory (CFA) factor analysis. Through exploratory factor analysis four factors were identified, labeled thinking, planning, revising, and monitoring, which represent different writing strategies. The confirmatory factor analysis confirmed the adequacy of the four-factor model, with a sustainable model composed of the four factors originally identified. Based on the analysis, the final questionnaire was composed of 16 items. According to the results, the Spanish version of the Writing Strategies Questionnaire (WSQ-SP) for upper-primary students has been shown to be a valid and reliable instrument, which can be easily applied in the educational context to explore upper-primary students' writing strategies.

Introduction

Writing has been defined as a problem-solving task that places multiple cognitive demands on the writer ( Hayes, 1996 ). As Flower and Hayes indicated in the first cognitive model of writing ( Flower and Hayes, 1980 ), writers have to manage several cognitively costly processes such as planning what to say, translating and transcribing those plans into written text, and revising either the plans or the written text ( Alamargot and Chanquoy, 2001 ; Hayes, 2012 ). The use of these processes, especially in young writers, in whom basic transcription skills are not yet automated ( Pontart et al., 2013 ; Alves et al., 2016 ; Limpo et al., 2017 ; Llaurado and Dockrell, 2020 ), consumes much of the capacity of their working memory as these processes recursively interact during composition ( McCutchen, 2011 ).

Following a comprehensive literature review, Graham and Harris (2000) concluded that writing development seems to depend on the automation of transcription skills and the acquisition of high-levels of self-regulation in order to handle high-level processes such as planning and revision. Self-regulation, represented by the use of writing strategies, is a critical aspect of writing as it enables writers to achieve their writing goals ( Zeidner et al., 2000 ; Santangelo et al., 2016 ; Puranik et al., 2019 ). These strategies may reduce cognitive overload as they allow writers to divide, sequence, and regulate the attention paid to the different writing processes ( Kieft et al., 2006 ; Beauvais et al., 2011 ). Empirical research has shown that writers' strategic behavior during composition strongly predicts the quality of “novices” and “experts” texts ( Beauvais et al., 2011 ; Graham et al., 2017a , 2019 ; Wijekumar et al., 2019 ). Accordingly, the use of writing strategies has been generally considered to be a critical individual writing-related variable ( Kieft et al., 2008 ), and is a major focus of research in writing instruction ( Harris et al., 2010 ; Graham and Harris, 2018 ) from the earliest stages of education ( Arrimada et al., 2019 ). Exploring students' use of different writing strategies during composition seems to be a critical aspect and should be considered in the fields of writing and writing instructional research.

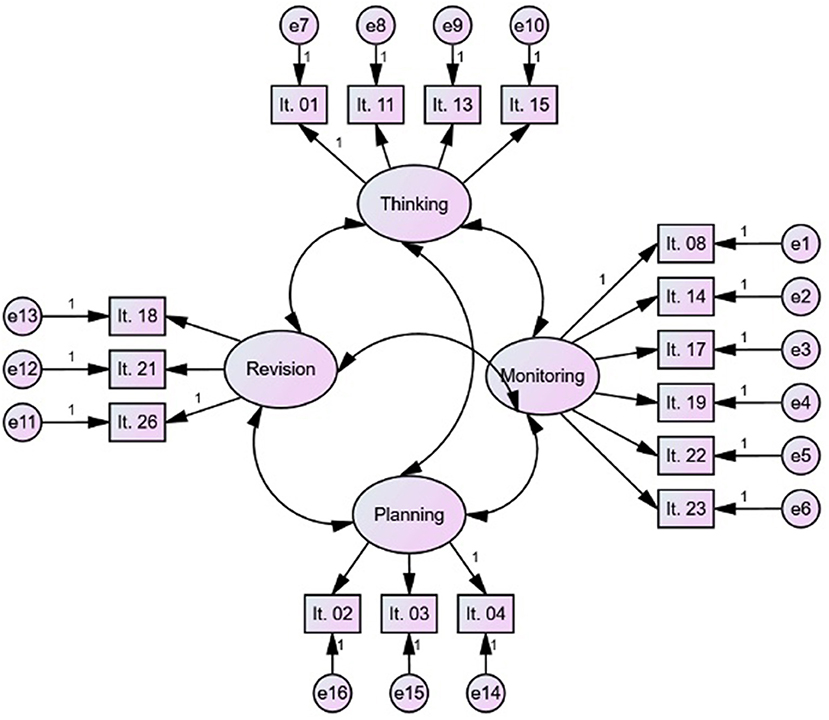

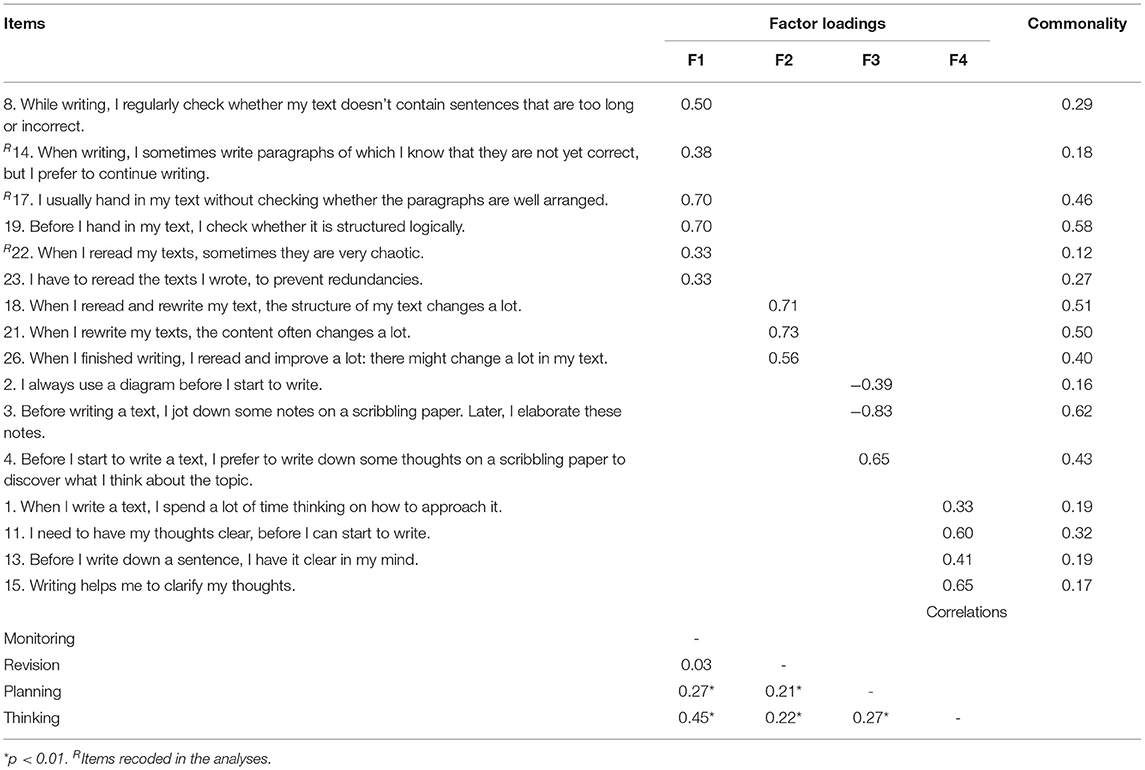

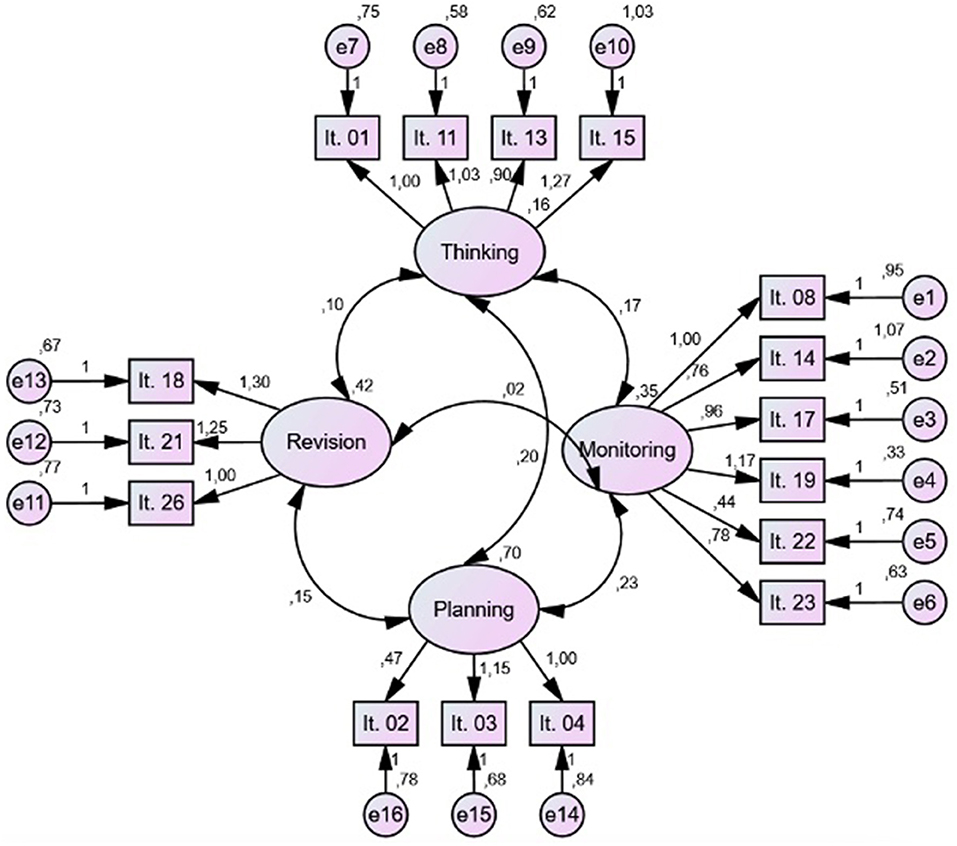

Several studies have attempted to explore how writers differ in the use of different writing strategies ( Torrance et al., 1994 , 1999 , 2000 ; Biggs et al., 1999 ; Lavelle et al., 2002 ; Kieft et al., 2006 , 2007 , 2008 ). These studies identified two main writing strategies, related with the processes identified in the first seminal cognitive model of writing ( Flower and Hayes, 1980 ), such as planning and revising. According to these studies, writers who follow a planning strategy tend to plan before beginning to write, whereas writers who prefer the revising strategy tend to plan by writing a rough draft first and then revising it. Despite the high-value of these studies, it is important to note that they only focused on analyzing the writing strategies in undergraduate ( Torrance et al., 1994 , 1999 , 2000 ; Biggs et al., 1999 ; Lavelle et al., 2002 ; Arias-Gundín and Fidalgo, 2017 ; Robledo Ramón et al., 2018 ) and secondary-school students ( Kieft et al., 2006 , 2008 ). To our knowledge, just one study has explored the use of different writing strategies with upper-primary Flemish students ( De Smedt et al., 2018 ). In this study, the authors implemented the Writing Strategies Questionnaire initially developed by Kieft et al. (2006 , 2008) and identified four factors by means of exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis which were labeled thinking, planning, revising and controlling. The planning and revising strategies were consistent with those identified in previous studies with secondary school students ( Kieft et al., 2006 , 2008 ). However, in that study the authors found two additional factors. The controlling factor was defined as students' tendency to check the content or structure of their text, whereas the thinking factor make reference to the extent to which students first think about the content of their text and about their writing approach before they start writing. Thus, according to this study, it seems to be that the questionnaire assesses writing strategies in a more comprehensive way than initially intended by Kieft et al. (2006 , 2008) .