124 Teenage Pregnancy Essay Topics + Examples

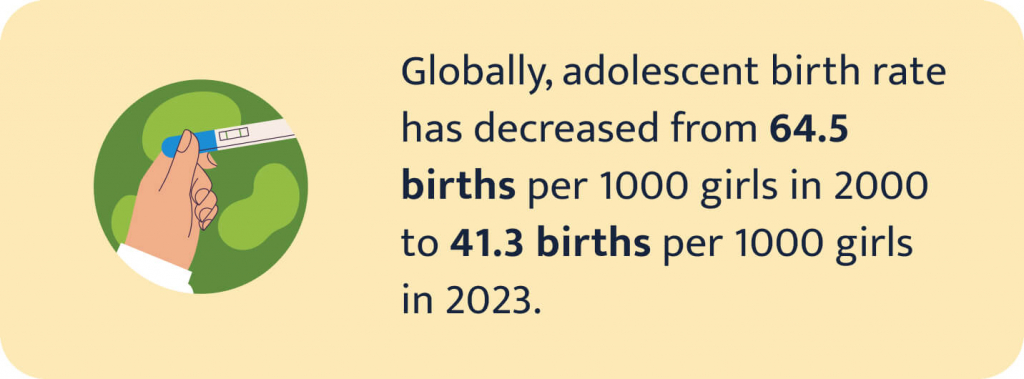

Early motherhood is a very complicated social problem. Even though the number of teenage mothers globally has decreased since 1991, about 12 million teen girls in developing countries give birth every year.

Our specialists will write a custom essay specially for you!

If you need to write a paper on the issue of adolescent pregnancy and can’t find a good topic, this article by our custom-writing experts will help you. Here, you will find:

- research topics about teenage pregnancy

- great essay prompts

- writing tips with examples.

- 🔝 Top-12 Teenage Pregnancy Topics

- 🚀 Research Topics about Teenage Pregnancy

- 🔮 Creative Essay Topics

- 💡 Essay Prompts

- 📑 Top 10 Examples

- 🤔 Writing Tips

🔗 References

🔝 top-12 teenage pregnancy essay topics.

- Effect of early childbearing on society.

- Risk factors for teenage fatherhood.

- Teenage pregnancy in developing countries.

- Risk of eclampsia in adolescent mothers.

- Early childbearing in industrialized countries.

- Low-income level and adolescent pregnancy.

- Preterm birth problems in adolescent mothers.

- Child neglect as a cause of teenage pregnancy.

- Socioeconomic factors of adolescent pregnancy.

- Psychological consequences of teenage pregnancy.

- Lack of education as the leading cause of early childbearing.

- Is lack of contraception the only cause of teenage pregnancy?

🚀 Research Topics about Teenage Pregnancy: Top Ideas for 2024

- Discuss the hidden factors behind alarming teen pregnancy statistics.

- Analyze the relationship between poverty and early pregnancy.

- What is the impact of teen pregnancy on maternal health ?

- Write about the impact of early pregnancy on a child’s development and well-being.

- Explore the psychological challenges faced by teenage mothers.

- The role of government policies in preventing teen pregnancy.

- Teenage mothers in foster care : risk factors and outcomes for teens and their children.

- The impact of early pregnancy on career opportunities for teenage mothers.

- Discuss the impact of media on attitudes toward teen pregnancy .

- Analyze the relationship between race and early pregnancy rates.

- Study the issue of teen pregnancy and the mental health needs of young mothers.

- What role can a healthcare provider play in preventing teenage pregnancy ?

- Analyze family relationships in a teenage couple post-pregnancy.

- Discuss the role of fathers in preventing teen pregnancy.

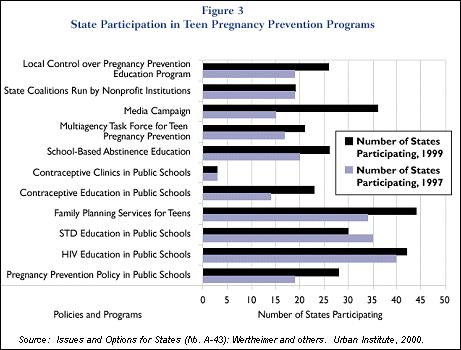

- Study a number of teen pregnancy prevention programs and evaluate their effectiveness.

- Young, pregnant, and incarcerated: the impact of teen pregnancy on the juvenile justice system .

- What is the relationship between teenage pregnancy and substance abuse?

- Write about the impact of abortion on teenage mothers as opposed to early motherhood.

- What is the role of schools in preventing teen pregnancy?

- Conduct a correlational analysis of teenage pregnancy and maternal mortality rates in the United States .

- How do teen pregnancy and domestic violence impact the unborn baby?

- Discuss the impact of teenage pregnancy on child abuse and neglect rates.

- Write about a possible solution to the problem of teen pregnancy and healthcare disparities in marginalized communities.

- What is the impact of teenage pregnancy on intergenerational poverty?

- Is there a correlation between socioeconomic status and teen pregnancy rates in developed countries?

- Analyze some of the factors that contribute to increased rates of teen pregnancy in Southern African countries.

- Explore the impact of teenage pregnancy on high school completion rates in Texas, US.

- What role do healthcare providers have in addressing the reproductive health needs of teenagers?

- Elaborate on why easy access to contraception is pivotal in reducing teen pregnancy rates.

- Discuss psychological and socioeconomic challenges faced by teenage fathers.

- What is the impact of teen pregnancy on rates of child poverty ?

- Explain the importance of family planning in preventing early pregnancy.

- Critically evaluate the influence of peer pressure on teenage sexual behavior.

- What is the psychological impact of the stigma associated with teenage pregnancy?

- Suggest ways to address the impact of teenage pregnancy on young mothers’ ability to attain financial independence.

- Discuss the importance of community support for teenage parents.

- What is the role of government policies in addressing the root causes of teen pregnancy ?

- Describe the impact of teenage pregnancy on young mothers’ self-esteem.

- A possible solution found: parental involvement in preventing teenage pregnancy.

- Speak about the impact of family, peer, and school context on teen pregnancy and childbearing.

- What is the role of technology in teen pregnancy prevention and intervention?

- Discuss the impact of parent-child communication on teen pregnancy prevention.

- A comparative study of teen pregnancy rates in urban and rural areas.

- Examine the relationship between teen pregnancy and risky sexual behavior .

- Write about the effectiveness of long-term contraceptive methods for teen pregnancy prevention.

- What impact do early childhood experiences have on teen pregnancy and childbearing?

- To what extent does teen pregnancy and intimate partner violence correlate?

- Explain the role of gender and sexuality in teen pregnancy rates and prevention.

- Elaborate on the relationship between teen pregnancy and poverty.

- What is the impact of early pregnancy on mental health outcomes for children?

- Speak about the effects of social media on teenage pregnancy and parenting behaviors.

- How does teenage pregnancy affect academic achievement and educational attainment?

- How school-based health clinics can assist in reducing teenage pregnancy rates.

- What is the relationship between teenage pregnancy and mental health outcomes for adolescent mothers ?

- How can media portrayals of pregnancy affect the behaviors of young mothers?

- Write about the effects of early childhood interventions on improving outcomes for children of teenage mothers.

- Speak about the role of healthcare providers in promoting family planning and reducing teen pregnancy rates.

- What effect can teenage pregnancy have on relationships between romantic partners?

- Explain the correlation between the COVID-19 lockdown and teenage pregnancy rates.

- Alarming statistics: sexual abuse as a contributing factor in teenage pregnancy.

- Discuss the complications after having an unwanted teenage pregnancy .

- What is the impact of gender roles and expectations on teenage pregnancy rates?

- Speak about the effects of pregnancy prevention programs on reducing repeat teen pregnancies.

- Analyze the relationship between early pregnancy and sexual and reproductive health outcomes.

- What are the major economic effects of increased contraceptive access among young women?

- Analyze the role of family dynamics and structure in teenage pregnancy prevention efforts.

- Write about the impact of legal and policy interventions on reducing teenage pregnancy rates in the United States.

- What are some cultural stereotypes regarding teen pregnancy?

- How does stigma affect attitudes toward teenage pregnancy and parenting?

- What are some of the determinant factors of the high adolescent pregnancy rate in Africa?

Teenage Pregnancy Topics for Quantitative Research

- Factors affecting teen pregnancy rate among African Americans.

- Teen birth rate disparity in underrepresented groups.

- Why has teen pregnancy been on the decline?

- An international perspective on the teen pregnancy rate in the US.

- Is sexual abstinence effective against early childbearing?

- The median age of sexual activity: teen pregnancy implications.

- How can we prevent adolescent pregnancies in catholic schools?

- How does sex education impact Hispanic teen pregnancy rates?

- The birth rate of American Indian and Alaska Native teens.

- How does teen pregnancy affect the rate of graduation from high school?

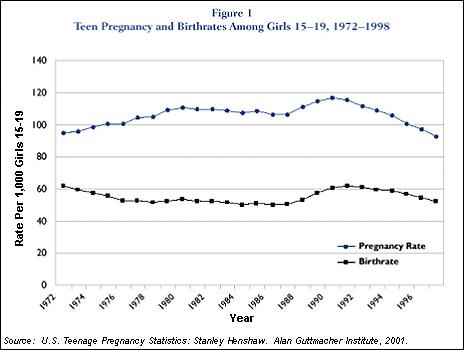

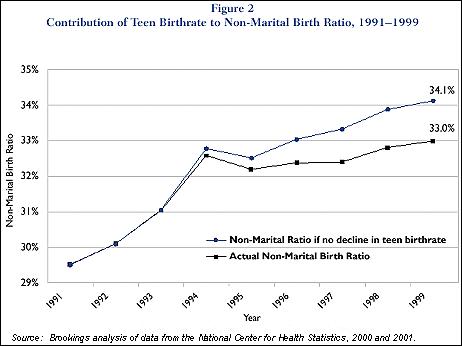

Recent quantitative research shows us that the teenage pregnancy rate decreases every year. This tendency started in 1991 and it still continues. Quantitative studies use numbers and statistics, and they help estimate the problem’s scope. You can write a survey of your own using the topics above.

Qualitative Research Topics about Teenage Pregnancy

- Educational factors affected by teen pregnancy.

- Teen pregnancy in Nebraska: qualitative analysis.

- Chicago African American teen pregnancies: insights from the community.

- Community leadership and teen pregnancy: core preventers.

- Teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases: an interview-based study.

- How to address the issue of access to sex education among Hispanic teen mothers.

- Teen pregnancy risk factors: things we still need to address.

- Sexual abuse and teen pregnancy: victim analysis.

- Determine essential areas of assistance for teen mothers.

Qualitative research deals with personal perspectives and often uses methods such as questionnaires. It helps determine the causes that lead to teenage pregnancy. Unhealthy childhood environments, domestic violence, and inaccessibility of education are the major factors influencing the chances of early pregnancy that you can research in your paper.

🔮 Creative Teenage Pregnancy Essay Topics

- Teen pregnancy among African Americans: a call for help.

- Adolescent pregnancy rates in Catholic schools.

- Sexual abstinence education and the Holy Bible.

- Explore the role of influencers, peer pressure, and online communities on teen pregnancies.

- Assistance for teen mothers: stopping the shaming.

- Spotting a sexual abuse victim: do not ignore teens.

- Compare different approaches to sex education and evaluate their effectiveness.

- The median age of sexual activity: what our leaders must do.

- God, adolescence, and motherhood: a catholic perspective.

- Explore the intersectional issues of sexism, racism , and classism in early parenthood.

In your essay on teenage pregnancy, you may look at the problem of early motherhood from a more unusual angle. For example, study the threats to young mothers, such as the absence of proper healthcare, illegal abortion, and family abuse. Make sure to read plenty of scientific literature while writing your paper on one of our creative topics.

Causes of Teenage Pregnancy Essay Topics

- Evaluate the role of proper sex education in reducing teenage pregnancies.

- How do parental relationships impact the likelihood of teen pregnancy?

- Assess the effect of substance abuse on adolescent pregnancy rates.

- Cultural and religious influences on teenage pregnancy rates in the US.

- Is academic pressure a contributing factor in teen pregnancy?

- Different family structures and teen pregnancy: a comparison.

- What mental disorders are likely to lead to an early pregnancy?

- Evaluate the effects of early sexual activity on the likelihood of teen pregnancy.

- Analyze various community programs and their impact on reducing teen pregnancy.

- How do various parenting styles influence early pregnancy rates?

- Psychological factors and emotional drivers of adolescent pregnancy.

- Does lack of communication contribute to teen pregnancy?

- How do disparities in education contribute to teenage pregnancy rates?

The causes of teenage pregnancy are numerous, and some are more studied than others. For example, the effect of social media on early motherhood is a relatively new phenomenon that you can research in your essay about teenage pregnancy.

Just in 1 hour! We will write you a plagiarism-free paper in hardly more than 1 hour

💡 Teenage Pregnancy Essay Prompts

Does access to condoms prevent teenage pregnancy: essay prompt.

- Access to condoms might result in an even higher rate of teenage pregnancies. In your essay, you can analyze previous research about the increase in adolescent pregnancies due to widespread condom distribution in schools.

- Access to condoms should come together with mandatory counseling. You might suggest this or other ways to make access to contraception methods more efficient in preventing teenage pregnancies.

- Sex education should be offered in all schools. Teenagers should have access to birth control and know how to use it to prevent unintended teenage pregnancy. Do you agree with this idea?

Teenage Pregnancy Solution Essay Prompt

- Ways in which parents and guardians can prevent early pregnancies. For example, parents can ask healthcare providers to educate their teenage children on the topic of contraception. Analyze these and other ways in which they may prevent adolescent pregnancies.

- The role of governments in teenage pregnancy prevention. Governments should raise awareness of the issue by developing programs and providing affordable family planning services. You might suggest other ways for the governments to contribute.

- What should teenagers do to avoid unwanted pregnancies? Some of the options are birth control methods and open conversations with their parents. What other options are there?

Teenage Pregnancy and Poverty Essay Prompt

- The correlation between poverty rate, education level, and teenage pregnancy. Many adolescent mothers live in poverty and lack education due to their social status. Your essay can analyze how these factors interact and result in early pregnancies.

- How does poverty lead to health issues in teenage mothers? Young mothers and children born in poverty have a high chance of developing health problems. Pregnancy is a vulnerable period in a woman’s life, and poverty only aggravates it. The risks include preterm birth and even infant death.

Causes and Effects of Teenage Pregnancy Essay Prompt

- The effect of alcohol and drugs on teenage pregnancy rates. Due to frequent social gatherings, alcohol, and drugs might become a part of a teenager’s life. Your cause-and-effect essay may analyze how substance use may lead to early unwanted pregnancy.

- How do TV shows influence teen pregnancy rates? The media often romanticizes this issue, which is why some teenagers may fail to understand the actual consequences of their decision to have children early. You may also analyze reality shows about teen pregnancy that take a more realistic approach, like 16 and Pregnant .

- The effect of early pregnancy on the future child’s parenting approach. Research shows that a teen mother’s child has a high chance of also becoming a teen parent . You might analyze this phenomenon in your paper.

📑 Teenage Pregnancy Essay Examples: Top 10

Want some more inspiration? Check out these outstanding examples:

- Teenage Pregnancy in Barking and Dagenham Borough

- School Sex Education and Teenage Pregnancy in the United States

- Teenage Pregnancy: Causes, Education, Prevention

- Teenage Pregnancy, Its Health and Social Outcomes

- Teenage Pregnancy and Its Negative Outcomes

- Teenage Pregnancy in the United Kingdom

🤔 Teenage Pregnancy Essay Writing Tips

Now that you’ve chosen a topic, it’s time to write an excellent teenage pregnancy essay. But how do you do it? Follow our helpful tips!

Teenage Pregnancy Essay Introduction

When writing an introduction , use a traditional structure:

- Present the problem you are addressing with some background info.

- State your position and the main points of your argumentation in a thesis statement .

Teenage pregnancy is among the leading causes of maternal mortality. Complicated pregnancy or traumatic childbirth causes the death of almost 30,000 adolescent girls every year. These alarming statistics prove that it is crucial to search for more efficient ways of reducing the teenage pregnancy rate.

Teenage Pregnancy Essay Body

The body paragraphs help you develop your argumentation. A standard 5-paragraph essay includes three body paragraphs. Each one conveys a key idea supported by evidence, such as interviews, statistics, and journal articles.

Here’s what one such paragraph may look like:

Receive a plagiarism-free paper tailored to your instructions. Cut 15% off your first order!

Research shows that proper sex education helps reduce the number of teenage pregnancies. According to a recent study by the University of Washington based on a national survey of 1,719 teenagers, comprehensive sex education more effectively reduces the early birth rate than the traditional abstinence-only approach.

Conclusion for an Essay About Teenage Pregnancy

An effective conclusion should draw attention to the problem and key points of the essay. Rephrase your thesis and give a short summary of your arguments:

Education is the key factor that leads to a reduction in teenage pregnancy. Statistical analysis shows that girls who do not get the proper education more often get pregnant before reaching adulthood. Literature analysis proves that adding comprehensive sex education to the school curriculum effectively reduces the teenage pregnancy rate. Thus, providing girls with proper education is an effective way to reduce the number of adolescent mothers.

Share this article with your friends and leave your comments below if you liked it! We are always happy to receive your feedback. Can’t choose the topic for your essay? Feel free to use our topic generator .

Further reading:

- Teenage Smoking Essay: Writing about Smoking Students

- 290 Good Nursing Research Topics & Questions

- 380 Powerful Women’s Rights & Feminism Topics [2024]

- 590 Unique Controversial Topics & Tips for a Great Essay

- How to Write a 5-Paragraph Essay: Outline, Examples, & Writing Steps

- Adolescent Pregnancy: World Health Organization

- About Teen Pregnancy: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Teenage Pregnancy: WebMD

- Teenage Pregnancy: American Pregnancy Association

- Adolescent Pregnancy: UNFPA

- Teenage Pregnancy: Healthline

- Trends in Teen Pregnancy and Childbearing: US Department of Health & Human Services

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to LinkedIn

- Share to email

Human rights are moral norms and behavior standards towards all people that are protected by national and international law. They represent fundamental principles on which our society is founded. Human rights are a crucial safeguard for every person in the world. That’s why teachers often assign students to research and...

Global warming has been a major issue for almost half a century. Today, it remains a topical problem on which the future of humanity depends. Despite a halt between 1998 and 2013, world temperatures continue to rise, and the situation is expected to get worse in the future. When it...

Have you ever witnessed someone face unwanted aggressive behavior from classmates? According to the National Center for Educational Statistics, 1 in 5 students says they have experienced bullying at least once in their lifetime. These shocking statistics prove that bullying is a burning topic that deserves detailed research. In this...

Recycling involves collecting, processing, and reusing materials to manufacture new products. With its help, we can preserve natural resources, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and save energy. And did you know that recycling also creates jobs and supports the economy? If you want to delve into this exciting topic in your...

Expository writing, as the name suggests, involves presenting factual information. It aims to educate readers rather than entertain or persuade them. Examples of expository writing include scholarly articles, textbook pages, news reports, and instructional guides. Therefore, it may seem challenging to students who are used to writing persuasive and argumentative...

Expository or informative essays are academic papers presenting objective explanations of a specific subject with facts and evidence. These essays prioritize balanced views over personal opinions, aiming to inform readers without imposing the writer’s perspective. Informative essays are widely assigned to students across various academic levels and can cover various...

![young pregnancy essay A List of 181 Hot Cyber Security Topics for Research [2024]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/hacker-cracking-binary-code-data-security-284x153.jpg)

Your computer stores your memories, contacts, and study-related materials. It’s probably one of your most valuable items. But how often do you think about its safety? Cyber security is something that can help you with this. Simply put, it prevents digital attacks so that no one can access your data....

A problem solution essay is a type of persuasive essay. It’s a piece of writing that presents a particular problem and provides different options for solving it. It is commonly used for subject exams or IELTS writing tasks. In this article, we’ll take a look at how to write this...

Have you ever wondered why everyone has a unique set of character traits? What is the connection between brain function and people’s behavior? How do we memorize things or make decisions? These are quite intriguing and puzzling questions, right? A science that will answer them is psychology. It’s a multi-faceted...

![young pregnancy essay Student Exchange Program (Flex) Essay Topics [2024]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/student-exchange-program-284x153.jpg)

Participating in a student exchange program is a perfect opportunity to visit different countries during your college years. You can discover more about other cultures and learn a new language or two. If you have a chance to take part in such a foreign exchange, don’t miss it. Keep in...

How can you define America? If you’ve ever asked yourself this question, studying US history will help you find the answer. This article will help you dive deeper into this versatile subject. Here, you will find: Early and modern US history topics to write about. We’ve also got topics for...

If you have an assignment in politics, look no further—this article will help you ace your paper. Here, you will find a list of unique political topics to write about compiled by our custom writing team. But that’s not all of it! Keep reading if you want to: Now, without further ado, let’s get started! Below, you’ll find political topics and questions for your task. 🔝 Top 10 Political...

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

- How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Teenage Pregnancy

Introduction, general overviews, textbooks and chapters in textbooks, reference books, anthologies, philosophies, demographics and statistics, adolescent sexual and reproductive health, protective factors, risk factors, pregnancy prevention programs, the americas, asia and the pacific, related articles expand or collapse the "related articles" section about, about related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Adolescence and Youth

- Child Poverty, Rights, and Well-being

- Children's Social Movements

- Gender and Childhood

- Peer Culture

- Race and Ethnicity

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Agency and Childhood

- Childhood and the Colonial Countryside

- Indigenous Childhoods in India

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Teenage Pregnancy by Andrew L. Cherry , Mary E. Dillon LAST REVIEWED: 26 October 2015 LAST MODIFIED: 26 October 2015 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199791231-0111

Since the 1950s, teenage pregnancy has attracted a great deal of concern and attention from religious leaders, the general public, policymakers, and social scientists, particularly in the United States and other developed countries. The continuing apprehension about teenage pregnancy is based on the profound impact that teenage pregnancy can have on the lives of the girls and their children. Demographic studies continue to report that in developed countries such as the United States, teenage pregnancy results in lower educational attainment, increased rates of poverty, and worse “life outcomes” for children of teenage mothers compared to children of young adult women. Teenage pregnancy is defined as occurring between thirteen and nineteen years of age. There are, however, girls as young as ten who are sexually active and occasionally become pregnant and give birth. The vast majority of teenage births in the United States occurs among girls between fifteen and nineteen years of age. When being inclusive of all girls who can become pregnant and give birth, the term used is adolescent pregnancy , which describes the emotional and biological developmental stage called adolescence. The concern over the age at which a young woman should give birth has existed throughout human history. In general, however, there are two divergent views used to explain teenage pregnancy. Some authors and researchers argue that labeling teen pregnancy as a public health problem has little to do with public health and more to do with it being socially, culturally, and economically unacceptable. The bibliographic citations selected for this article will be extensive. The objective is to cover the major issues related to teenage pregnancy and childbearing, and adolescent pregnancy and childbearing. Childbirth to teenage mothers in the United States peaked in the mid-1950s at approximately 100 births per 1,000 teenage girls. In 2010, the rate of live births to teenage mothers in the United States dropped to a low of 34 births per 1,000. This was the lowest rate of teenage births in the United States since 1946. In 2012, the live births to teenage mothers continued to decline to 29.4 per 1,000. This was a drop of 13.5 percent from 2010. In 2012, some 305,388 babies were born to girls between fifteen and nineteen years of age. Among girls fourteen and younger the rate of pregnancy is about 7 per 1,000. About half of these pregnancies (3 per 1,000) resulted in live births. In spite of this decline in teenage pregnancy over the years, approximately 820,000 (34 percent) of teenage girls in the United States become pregnant each year. What’s more, some 85 percent of these pregnancies are unintended. These pregnancies and births suggest that the story of teenage pregnancy is not in the numbers of teen pregnancies and births but in the story of what causes the increase and decrease in the numbers. With the objective in mind to better understand teenage pregnancy, a general overview is provided as a broad background on teenage pregnancy. Citations are grouped under related topics that explicate the complexity of critical forces affecting teenage pregnancy. Topics that provide a global view of the variations in perception of and response to teenage pregnancy will also be covered in this article.

Adolescent pregnancy is a complex issue with many reasons for concern. Teenage pregnancy is a natural human occurrence that is a poor fit with modern society. In many ways it has become a proxy in what could be called the cultural wars. On one philosophical side of the debate, political and religious leaders use cultural and moral norms to shape public opinion and promote public policy with the stated purpose of preventing teen pregnancy. To begin, Martin, et al. 2012 provides national vital statistics on teen pregnancy. Leishman and Moir 2007 provides a good overview of these broader issues. Demographic studies by organizations like the Alan Guttmacher Institute ( Alan Guttmacher Institute 2010 ) give a statistical description of teenage pregnancy in the United States. The number of teen pregnancies and the pregnancy outcomes are often used to support claims that teenage pregnancy is a serious social problem. The other side of this debate presented in publications by groups like the World Health Organization ( World Health Organization 2004 ) reflects the medical professionals, public health professionals, and academicians who make a case for viewing teenage sexuality and pregnancy in terms of human development, health, and psychological needs. These two divergent views of teen pregnancy are represented in the United States by groups such as Children’s Aid Society; Healthy Teen Network; Center for Population Options; Advocates for Youth; National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy; National Organization on Adolescent Pregnancy, Parenting, and Prevention; state-level adolescent pregnancy prevention organizations; and other organizations that include teen pregnancy within their scope of interest and services. Mollborn, et al. 2011 delineates other important aspects of teenage pregnancy (race, poverty, and religious influences) that help explain why teenage pregnancy is considered a problem in some circles. The association between teenage pregnancy and social disadvantage, however, is not just found in the United States. Harden, et al. 2009 reports on the impact of poverty on teenage pregnancy rates in the United Kingdom. This phenomenon is not isolated to the United States and Great Britain; it is global. Holgate, et al. 2006 and the authors of Cherry and Dillon 2014 provide a comprehensive overview of global teenage pregnancy. To round out this general overview, the article Jiang, et al. 2011 is a description of a pragmatic national effort to improve the sexual and reproductive health of all adolescents and young adults. The best sources for research are professional journals and monographs from national and international health and development organizations focused on specific countries, regions, and global teenage pregnancy variations and trends.

Alan Guttmacher Institute. U.S. Teenage Pregnancies, Births and Abortions: National and State Trends and Trends by Race and Ethnicity . New York: Alan Guttmacher Institute, 2010.

Save Citation » Export Citation » Share Citation »

This report describes trends in teenage pregnancy, childbearing, and abortion in the United States. The statistics reveal discernible variations in teen birth and abortions between states. There is also a wide variation in teen pregnancy between racial and ethnic groups. Since the slight increase in 2006 rates have continued to decline.

Find this resource:

- Google Preview»

Cherry, Andrew L. “Biological Determinants and Influences Affecting Adolescent Pregnancy.” In International Handbook of Adolescent Pregnancy: Medical, Psychosocial, and Public Health Responses . By Andrew Cherry and Mary Dillon, 39–53. New York: Springer Science & Business Media, 2014.

This chapter highlights the biological determinants that influence adolescent sexuality and pregnancy. While our genes influence individual sexual development and behavior, the question is how much. Integrated biopsychosocial models are more accurate and give a richer picture of the determinants of adolescent sexuality.

Cherry, Andrew, and Mary Dillon. International Handbook of Adolescent Pregnancy: Medical, Psychosocial, and Public Health Responses . New York: Springer Science & Business Media, 2014.

DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4899-8026-7 Save Citation » Export Citation » Share Citation »

In this edited volume, eight chapters deal with issues related to adolescent pregnancy, such as mental health; biological determinants; fatherhood; pregnancy among lesbian, gay, and bisexual teens; etc. Additionally, thirty-one chapters cover major variations in the way adolescent pregnancy is viewed from different countries around the world.

Harden, Angela, Ginny Brunton, Adam Fletcher, and Ann Oakley. “Teenage Pregnancy and Social Disadvantage: Systematic Review Integrating Controlled Trials and Qualitative Studies.” British Medical Journal 339 (2009): 1182–1185.

DOI: 10.1136/bmj.b4254 Save Citation » Export Citation » Share Citation »

This is a review of interventions addressing social disadvantages associated with adolescent pregnancy in the United Kingdom. Teenage pregnancy rates were 39 percent lower among teenagers receiving both early childhood intervention and youth development programs that address “dislike of school,” “poor material circumstances and unhappy childhood,” and “low expectations for the future.”

Holgate, Helen S., Roy Evans, and Francis K. O. Yuen. Teenage Pregnancy and Parenthood: Global Perspectives, Issues and Interventions . New York: Routledge, 2006.

Teenage pregnancy and parenting, especially at a young age, is typically viewed as personally and socially undesirable. Governments worldwide demonstrate concern about teenage pregnancy in their policies and programs. This book provides a broad range of international perspectives and cultural contexts, and looks at interventions and examples of best practices.

Jiang, Nan, Lloyd J. Kolbe, Dong-Chul Seo, Noy S. Kay, and Claire D. Brindis. “Health of Adolescents and Young Adults: Trends in Achieving the 21 Critical National Health Objectives by 2010.” Journal of Adolescent Health 49 (2011): 124–132.

DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.04.026 Save Citation » Export Citation » Share Citation »

This is a report on the 21 Critical National Health Objectives for Adolescents and Young Adults in the United States as described in Healthy People 2010 . Two of the twenty-one goals were reached, reduction in adolescents riding with a drunk driver, and reduced physical fighting. Progress varied by demographic variables.

Leishman, June, and James Moir. Pre-Teen and Teenage Pregnancy: A Twenty-First Century Reality . Keswick, UK: M&K Update, 2007.

This book is a good place to start. It provides a standard definition of adolescents. The premise is that the physical and emotional health of teenagers has always been a complex issue and continues to challenge modern societies. It offers insight into the social reality of sexually active adolescents.

Martin, J. A., B. E. Hamilton, S. J. Ventura, M. J. Osterman, E. C. Wilson, and T. J. Mathews. “National vital statistics reports.” National Vital Statistics Reports 61.1 (2012).

This brief report shows the latest available statistical on teenage pregnancy in the United States. The report shows that teenage pregnancy continued to fall for all groups. Nevertheless the disparity between the rate of live births is two times higher among non-Hispanic African American and Hispanic girls compared to non-Hispanic white girls.

Mollborn, Stefanie, Benjamin W. Domingue, and Jason D. Boardman. Racial, Socioeconomic, and Religious Influences on School-Level Teen Pregnancy Norms and Behaviors . Boulder: Institute of Behavioral Science, University of Colorado, 2011.

This report provides a broad overview of the influence and role of schools on teenage pregnancy. The impact of the school’s social, economic, and racial composition on teenage pregnancy rates among students is examined. Focusing on “age norms,” the authors answer the question, How do norms explain school pregnancy rates?

World Health Organization. Adolescent Pregnancy: Issues in Adolescent Health and Development . Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2004.

This overview of global adolescent health, development, and pregnancy covers both developed and developing countries. Social indicators and statistics show the increase in teen pregnancy after World War II and the surprising decline in the 1990s. This occurred as social control by parents and family declined.

As of mid-year 2012, there were few books designed as textbooks to be used in college classes on teenage pregnancy. This lack of textbooks and chapters, however, does not mean that this topic is not addressed in academia. Research related to teenage pregnancy (not including demographic studies and comparisons) has been mainly limited to the medical, behavioral, and social sciences. An exception is the textbook Farber 2009 . Written for social workers and students in the helping professions, it covers the risk factors and prevention. There are other books that might be used as supplemental reading material: Goldstein 2011 has a medical orientation but it was not written to be a textbook. There are several chapters on teenage pregnancy written in textbooks, for example, Armstrong 2001 . Other chapters are included in volumes related to adolescent health. Wells 2006 would be useful as a supplemental text. It presents opposing viewpoints. Other volumes such as Cater and Coleman 2006 explore why teenage girls in Great Britain plan their pregnancies. Another publication, Romer 2003 , could stimulate class discussions about the perception of what is an integrated approach to reducing the risk of adolescent pregnancy. Two other books that could be used in a college class are Maynard 1996 , a classic that makes the case that teenage pregnancy is a problem that needs to be addressed, and Cocca 2006 , which provides a historical background.

Armstrong, Bruce. “Adolescent Pregnancy.” In Handbook of Social Work Practice with Vulnerable and Resilient Populations . Edited by Alex Gitterman, 305–341. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001.

This chapter provides students in the helping professions with a more in-depth discussion of the experience of teenagers who become pregnant and parent their children. Examining vulnerability and resilience, the chapter makes the point that pregnancy and parenting during adolescence is a contentious public issue and has resulted in perplexing policy.

Cater, Suzanne, and Lester Coleman. “Planned” Teenage Pregnancy: Perspectives of Young Parents from Disadvantaged Backgrounds . Bristol, UK: Policy, 2006.

This is a study of the reasons teenage girls facing poverty and disadvantage in the United Kingdom plan their pregnancies. Interviews with the teens are used to suggest policy implications for reducing teen pregnancy and how “planning” is viewed by policymakers.

Cocca, Carolyn. Adolescent Sexuality: A Historical Handbook and Guide . Westport, CT: Praeger, 2006.

This is a set of five essays dealing with adolescent sexuality, which includes adolescent pregnancy. It also includes a broad survey of the history of perceptions of adolescent sexuality and chapters on rape, pregnancy, sex education, and pop culture.

Farber, Naomi. Adolescent Pregnancy: Policy and Prevention Services . 2d ed. New York: Springer, 2009.

This textbook is primarily written for social workers and others in the helping professions who provide services to adolescents and teenagers. It covers the risk factors, child-family outcomes, and prevention. It addresses public policy and practice issues related to adolescent sexual health risks and the variation in teen pregnancy rates. Originally published in 2003.

Goldstein, Mark A. “Adolescent Pregnancy.” In The MassGeneral Hospital for Children: Adolescent Medicine Handbook . Edited by Mark A. Goldstein, 111–113. New York: Springer, 2011.

DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6845-6_15 Save Citation » Export Citation » Share Citation »

This is a medical-oriented description of teenage pregnancy focusing on predictors. Listed causes are: early pubertal development, sexual abuse, poverty, lack of a nurturing family, substance abuse, low expectations or career goals, and poor school performance. “Just say no” and “virginity pledges” may decrease the likelihood of using contraception.

Maynard, Rebecca A., ed. Kids Having Kids: Economic Costs and Social Consequences of Teen Pregnancy . Washington, DC: Urban Institute, 1996.

During the early 1990s, four hundred thousand US girls under the age of eighteen gave birth. This was twice the rate of other developed countries. Estimated economic and social costs of teenage childbearing are presented and contrasted with the strengths and weaknesses of specific policies and programs to prevent teen pregnancy and childbirth.

Romer, Daniel. Reducing Adolescent Risk: Toward an Integrated Approach . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2003.

This is a good source on the topic of adolescent risk-taking behaviors (such as unprotected sex resulting in teen pregnancy). Understanding the role that adolescent risk taking often plays in sexual behavior is important for understanding unplanned teen pregnancy. This volume provides prevention and programming resources.

Wells, Ken R., ed. Teenage Sexuality: Opposing Viewpoints . Farmington Hills, MI: Greenhaven, 2006.

This is the latest in an opposing viewpoint series that can be useful supplemental material in some educational settings. It approaches teenage pregnancy by providing expert opinions in a pro versus con format.

The following reference material covers many issues that mark teenage pregnancy as an important issue in modern society. The debate is over whether teenage pregnancy is a serious health problem that requires intervention and prevention programming or whether it is a constructed crisis perpetuated by a conservative segment of society trying to enforce moral standards in an effort to save the greater society. The more pragmatic, less moralistic assessments tend to equate teenage pregnancy with adolescent sexual and reproductive health. What is evident from the literature is that on an individual level, adolescent pregnancy can and does change the trajectory of the teen mother and her child’s future. Rayes 2010 does a good job showing how trends influence public policy that results from concern over teenage pregnancy. The edited book by Card and Benner 2008 is a good source of descriptions of model programs to improve adolescent sexual health. Vinovskis’s work ( Vinovskis 1988 ) began early to make the case that teenage pregnancy was inappropriately being characterized as a problem. It helps put the policy issue in perspective. Fraser 2004 portrays teen pregnancy in an ecological context. This is a view that does not blame the teenager for her pregnancy. Arai 2009 takes a similar position in explaining teenage pregnancy in Great Britain. Early negative life events have been studied by Felitti and Anda ( Felitti and Anda 2010 ); they discuss these effects on adolescent pregnancy and the on long-term psychosocial outcomes and fetal death. Lancaster and Hamburg 2008 is similar with a biosocial emphasis. Finally, Laser and Nicotera 2010 employs these ideas for practitioners who work with adolescents. Cherry, et al. 2009 shows that although the physical risk associated with biological immaturity is ever present when young girls become pregnant, this risk (supported by research worldwide) for the most part has been shown to be caused by the social context in which the girls live. What is clear in the literature is that assumptions and perspectives can either increase risk or modulate the risk associated with an adolescent pregnancy.

Arai, Lisa. Teenage Pregnancy: The Making and Unmaking of a Problem . Bristol, UK: Policy, 2009.

This book presents the findings of a longitudinal study of adolescent health that focuses on teenage pregnancy. The author identifies strategies to reduce teenage pregnancy, reframes teen pregnancy as a social exclusion issue rather than a moral issue, and promotes increasing the participation of teen mothers in education and employment.

Card, Josefina J., and Tabitha A. Benner, eds. Model Programs for Adolescent Sexual Health: Evidence-Based HIV, STI, and Pregnancy Prevention Interventions . New York: Springer, 2008.

This volume provides a directory of model programs for adolescent sexual health. Programs described are among the most promising and empirically tested sexual education and prevention programs in the United States. Programs included were selected for their demonstrated positive impact.

Cherry, Andrew L., Lisa Byers, and Mary E. Dillon. “A Global Perspective on Teen Pregnancy.” In Maternal and Child Health: Global Challenges, Programs, and Policies . Edited by John Ehiri, 375–397. New York: Springer, 2009.

DOI: 10.1007/b106524 Save Citation » Export Citation » Share Citation »

This chapter presents a global view of teenage pregnancy comparing developed and developing counties in terms of attitudes, perspectives, and approaches employed to deal with teen pregnancy. The primary conclusions: the more educational, occupational, and economic opportunity available to teenage girls, the more likely they are to postpone pregnancy and childbirth.

Felitti, Vincent J., and Robert F. Anda. “The Relationship of Adverse Childhood Experiences to Adult Medical Disease, Psychiatric Disorders and Sexual Behavior: Implications for Healthcare.” In The Impact of Early Life Trauma on Health and Disease: The Hidden Epidemic . Edited by Ruth A. Lanius, Eric Vermetten, and Clare Pain, 77–87. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

DOI: 10.1017/CBO9780511777042 Save Citation » Export Citation » Share Citation »

Early negative life events are increasingly recognized as having serious and long-lasting effects. Emotional traumas during childhood impact neural and biological systems required for labile stability, general well-being, biomedical disorders, social function, and psychopathology. The effects of adolescent pregnancy on long-term psychosocial outcomes and fetal death are discussed.

Fraser, Mark W., ed. Risk and Resilience in Childhood: An Ecological Perspective . 2d ed. Washington, DC: NASW, 2004.

Each chapter deals with a different issue. Based on the ecological and multisystemic perspective, protective factors and risk factors for teenage pregnancy, school failure, and other childhood behaviors (i.e., disorders in childhood, drug use, and delinquency) are examined using an ethnocultural perspective.

Lancaster, Jane B., and Beatrix A. Hamburg. School-Age Pregnancy & Parenthood: Biosocial Dimensions . New Brunswick, NJ: Aldine Transaction, 2008.

In this biosocial perspective of teenage pregnancy both the biological substratum and the social environment are proposed as essential codeterminants of behavior. Culturally defined responses to the basic needs of pregnant and parenting girls is presented to explain the medical and social response and the challenge of teen pregnancy and childbearing.

Laser, Julie Anne, and Nicole Nicotera. Working with Adolescents: A Guide for Practitioners . Social Work Practice with Children and Families Series. New York: Guilford, 2010.

The authors take the position that teenage pregnancy is one of several adolescent problem behaviors. An ecological perspective is used to explain and address specific challenges faced by adolescents. The theoretical framework is followed by a section on the adolescent in context. It concludes with clinical interventions for problematic adolescent behaviors.

Rayes, Gilberto de la. Nonmarital Childbearing: Trends, Reasons and Policy . New York: Nova Science, 2010.

In 2006, 38.5 percent of all US births were among single mothers (single teenage girls and young women). Birth without marriage is viewed as a serious problem among social conservatives. Research cited suggests that children who grow up with only one biological parent often experience worse lifetime outcomes than peers.

Vinovskis, Maris A. An “Epidemic” of Adolescent Pregnancy? Some Historical and Policy Considerations . New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

This book is a historical review of adolescent sexuality and pregnancy starting in colonial times. It includes background on the origins of federal programs and policies that produced unexpected outcomes that were frequently not in line with expectations. This book also includes perspectives on the role of the adolescent father.

The following reference matter covers some of the most important issues related to teenage pregnancy. Foremost, as Patton, et al. 2010 and Hagen, et al. 2012 , make the point; teenage pregnancy is a health issue that fundamentally affects the sexual and reproductive health of the girl who is pregnant. Yet, Jewell 2000 and others believe that teenage pregnancy is a social problem. It is also a public health concern and a concern for those specializing in family planning. Prevention is another area that is supported by both professionals and the public. The definition of prevention, however, may be very different. As such, sexual education, the centerpiece of any prevention program, is hotly debated in many countries, particularly in the United States. In part, it is because the question is framed as an effort to prevent teen pregnancy. This is unfortunate. In many cases, the consequences of the prevention efforts often result in increases in sexually transmitted disease, pregnancy, and abortions. Approaching the task of providing sexual education from a justice perspective is different. The reason for providing accurate age-graded sexual information from a justice perspective, as Catania and Dolcini 2012 and Secor-Turnera, et al. 2011 suggest, is that it is an inalienable right of all people, especially adolescents and in particular teenagers, to have accurate information about their sexual and reproductive health. Even so, as Kaye, et al. 2009 and Collins, et al. 2011 explain, this does not exclude the influence of family, parents, or the religious community. Parents and peers are very influential on adolescent sexual behavior. Religion can be significant in delaying sexual initiation but is also associated with a failure to use a condom at first sexual intercourse.

Catania, Joseph A., and M. Margaret Dolcini. “A Social-Ecological Perspective on Vulnerable Youth: Toward an Understanding of Sexual Development among Urban African American Adolescents.” Research in Human Development 9 (2012): 1–8.

DOI: 10.1080/15427609.2012.654428 Save Citation » Export Citation » Share Citation »

A social-ecological framework is used to explore the complex factors influencing adolescent sexual development among urban African American youth living in low-income neighborhoods. Using a multistage qualitative investigation, the researchers offer new data on the sexual development of urban African American adolescents.

Collins, Rebecca L., Steven C. Martino, Marc N. Elliott, and Angela Miu. “Relationships between Adolescent Sexual Outcomes and Exposure to Sex in Media: Robustness to Propensity-Based Analysis.” Developmental Psychology 47 (2011): 585–591.

DOI: 10.1037/a0022563 Save Citation » Export Citation » Share Citation »

The effect of exposure to sex in the media on adolescent initiation of sexual intercourse is still an open question. This article reviews research that has been conducted and finds a weak association between media exposure and sexual initiation. The authors suggest that youth exposure to sexual content be reduced.

Hagen, Janet W., Alice H. Skenandore, Beverly M. Scow, Jennifer G. Schanen, and Frieda Hugo Clary. “Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention in a Rural Native American Community.” Journal of Family Social Work 15 (2012): 19–33.

DOI: 10.1080/10522158.2012.640926 Save Citation » Export Citation » Share Citation »

Native American girls have a higher rate of teen pregnancy than the US national average. A five-year study of eighth graders who were taught the Discovery Dating curriculum resulted in fewer pregnancies and higher use of condoms than eighth graders in the control group.

Jewell, David. “Teenage Pregnancy: Whose Problem Is It?” Family Practice 17 (2000): 522–528.

DOI: 10.1093/fampra/17.6.522 Save Citation » Export Citation » Share Citation »

This qualitative study of thirty-four teenage mothers from the United Kingdom examines teenage mothers’ attitudes about sexual health, contraception, and pregnancy. Teens from less affluent families reported more problems accessing contraceptive services and dissatisfaction with sexual education in schools. Abortion was also less acceptable to the socially disadvantaged girls.

Kaye, Kelleen, Kristin Anderson Moore, Elizabeth C. Hair, Alena M. Hadley, Randal D. Day, and Dennis K. Orthner. “Parent Marital Quality and the Parent–Adolescent Relationship: Effects on Sexual Activity among Adolescents and Youth.” Marriage and Family Review 45 (2009): 270–288.

DOI: 10.1080/01494920902733641 Save Citation » Export Citation » Share Citation »

Teenagers growing up outside of an intact family are likely to engage in risky sexual behaviors. This study looks at characteristics within married-parent families to identify sources that influence adolescent sexual activity. Marital relationship, the youth–parent relationship, and the interaction of the two are identified and discussed.

Patton, George C., Russell M. Viner, Le Cu Linh, et al. “Mapping a Global Agenda for Adolescent Health.” Journal of Adolescent Health 47 (2010): 427–432.

DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.08.019 Save Citation » Export Citation » Share Citation »

Positive changes are taking place in health care in many developing countries that will benefit adolescents. This paper reports on a 2009 London meeting related to strategic data needed to monitor future global initiatives in adolescent health. Developing a core set of global adolescent health indicators would facilitate this process.

Secor-Turnera, Molly, Renee E. Sieving, Marla E. Eisenberg, and Carol Skay. “Associations between Sexually Experienced Adolescents’ Sources of Information about Sex and Sexual Risk Outcomes.” Sex Education: Sexuality, Society and Learning 11 (2011): 489–500.

DOI: 10.1080/14681811.2011.601137 Save Citation » Export Citation » Share Citation »

This secondary analysis reports on informal sources about sexual risk among a group ( N = 22,828) of sexually experienced teenagers aged thirteen to twenty. Friends and siblings were most often the source of information about sex. When accurate sexual information comes from friends and siblings, it reduces teenage sexual risk.

The citations presented in this section are for the most part literature reviews. Nevertheless, in several of these articles ( Coles, et al. 1997 and Jolly, et al. 2007 ), the authors and researchers provide information from the teenagers themselves that informs and provides insight into the reasons and circumstances associated with teenage sexual behavior. Teenage fathers are also introduced under this topic with the literature review Lohan, et al. 2010 . Although little attention has been paid to teenage fathers, they play a major role, whether involved with the mother and child or absent from that relationship. More research is needed to increase our understanding of how professionals and society can support the teenage father’s effort to become a responsible father, husband, and adult. School-based health clinics are another important program type. Strunk 2008 is a good source of descriptions of these model programs. Putting in perspective the need for adolescent pregnancy health services Sells and Blum 1996 shows that adolescent morbidity and mortality has declined since 1979 by 13 percent. Other conditions that are often overlooked are the effect of child abuse and child sexual abuse on the life trajectory of adolescent girls, delineated by Francisco, et al. 2008 , and the influence of the neighborhood context, explored by Lupton and Kneale 2010 , particularly, as Buhi and Goodson 2007 points out, in relationship to early pregnancy.

Buhi, Eric R., and Patricia Goodson. “Predictors of Adolescent Sexual Behavior and Intention: A Theory-Guided Systematic Review.” Journal of Adolescent Health 40 (2007): 4–21.

DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.09.027 Save Citation » Export Citation » Share Citation »

This systematic literature review was conducted to answer the question, “Why do adolescents initiate sexual activity at early ages?” Three conditions were identified that help explain the behavior: intention, perceived norms , and time home alone . Based on the literature, these variables were good predictors of adolescent initiation of sexual behavior.

Coles, Robert, Robert E Coles, Daniel A Coles, and Michael H. Coles. The Youngest Parents: Teenage Pregnancy as It Shapes Lives . New York: W. W. Norton, 1997.

The voices of teenage girls and boys who were soon to be parents are presented in an effort to challenge preconceived ideas about teenagers who become pregnant and parents. Their stories are unique and reveal much to respect.

Francisco, Melissa A., Kasey Hicks, Julianne Powell, Kristin Styles, Jessica L. Tabor, and Linda J. Hulton. “The Effect of Childhood Sexual Abuse on Adolescent Pregnancy: An Integrative Research Review.” Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing 13 (2008): 237–248.

DOI: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2008.00160.x Save Citation » Export Citation » Share Citation »

In 2008, during a brief period of time when adolescent pregnancies in the United States increased, there were renewed calls for research related to identifying risk factors involved in adolescent pregnancy. Based on a meta-analysis, the authors determined the existence and strength of the relationship between child sexual abuse and adolescent pregnancy.

Jolly, Kim, Josie A. Weiss, and Patricia Liehr. “Understanding Adolescent Voice as a Guide for Nursing Practice and Research.” Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing 30.1–2 (2007): 3–13.

DOI: 10.1080/01460860701366518 Save Citation » Export Citation » Share Citation »

This article focuses on adolescent attitudes about contraception and adolescent depression, taking into consideration the ethnocultural context. Giving voice to adolescents by listening to their stories is proposed as a way of improving health care provided to teenagers and as a basis for further research.

Lohan, Maria, Sharon Cruise, Peter O’Halloran, Fiona Alderdice, and Abbey Hyde. “Adolescent Men’s Attitudes in Relation to Pregnancy and Pregnancy Outcomes: A Systematic Review of the Literature from 1980–2009.” Journal of Adolescent Health 47 (2010): 327–345.

DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.05.005 Save Citation » Export Citation » Share Citation »

A review of the professional literature exposed a long-standing gender bias in academic and policy research on adolescent pregnancy, which has resulted in the lack of research on the perspectives of the adolescent male. This article sums up the literature related to adolescent boys and their attitude toward pregnancy and parenting.

Lupton, Ruth, and Dylan Kneale. Are There Neighbourhood Effects on Teenage Parenthood in the UK, and Does It Matter for Policy? A Review of Theory and Evidence . London School of Economics and Political Science CASE 141. London: Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion, 2010.

This paper is a review of the evidence for considering “neighborhood effects” in relationship to teenage pregnancy. This review identifies three explanations for teen pregnancy (opportunity costs, differential values, and social networks). Although neighborhoods may influence the rate of teen pregnancy, the authors conclude that statistical evidence is mixed.

Sells, C. Wayne, and Robert W. Blum. “Morbidity and Mortality among US Adolescents: An Overview of Data and Trends.” American Journal of Public Health 86 (1996): 513–519.

DOI: 10.2105/AJPH.86.4.513 Save Citation » Export Citation » Share Citation »

This is an analysis of data about adolescent morbidity and mortality in the United States (1979–1994). Since the 1980s mortality declined 13 percent among fifteen- to twenty-four-year-olds. Messages related to the benefits of contraceptives and the prevention of sexually transmitted disease have had a positive impact on the rate of unwanted teen pregnancies and childbearing.

Strunk, Julie A. “The Effect of School-Based Health Clinics on Teenage Pregnancy and Parenting Outcomes: An Integrated Literature Review.” The Journal of School Nursing 24 (2008): 13–20.

DOI: 10.1177/10598405080240010301 Save Citation » Export Citation » Share Citation »

This review of the literature offers substantial research findings that suggest many of the problems associated with teenage pregnancy and parenting could be lessened if school-based programs offer counseling, health care, health education, and classes on childhood development.

There are no journals that are exclusively dedicated to teenage pregnancy issues; however, there are a number of journals focused on adolescent issues, such as the Journal of Adolescence , Journal of Adolescent Health , Journal of Research on Adolescence , and International Family Planning Perspectives , which tend to publish articles on teenage and adolescent pregnancy and childbirth. Pediatrics and the American Journal of Public Health have a propensity to cover many of the issues related to teenage pregnancy. The journals listed here such as the Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry and the International Journal of Epidemiology are examples of professional publications that emphasize medical, psychological, or sociological perspectives. Of course, other journals similar to Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care will publish articles related to teen pregnancy depending on their area of clinical, medical, or social service interest.

American Journal of Public Health .

This journal focuses on research methods and program evaluation related to public health. In an effort to improve public health research, the journal publishes articles related to public health policy, best practices, and education. Epidemiologists, a broad range of social scientists, and medical and helping professionals access this journal.

International Family Planning Perspectives . 1995–2008.

This journal published studies conducted in the United States and other developed countries in the world. Articles published cover contraceptive practice; fertility levels, trends, and determinants; adolescent pregnancy; abortion; public policies and legal issues affecting childbearing; and other critical issues related broadly to family planning practice.

International Journal of Epidemiology .

This international journal publishes studies about epidemiological advances and new developments and changes in the global population. Articles and studies related to teenage pregnancy typically focus on effects of prevention programming, health services, and medical care.

Journal of Adolescence .

This is an international, multidisciplinary, broad-based journal that is concerned with the nature of adolescent development (i.e., emphasis is on personality, social, and emotional functioning). It publishes empirical studies, clinical studies, and literature reviews. A broad field of professionals specializing in services to adolescents read and publish in this journal.

Journal of Adolescent Health .

This is a multidisciplinary scientific journal. It publishes research in the field of adolescent medicine and health. Articles typically cover biological, behavioral, public health, and policy issues. Professionals involved in adolescent health access this journal. This is the official publication of the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine.

Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care .

The journal emphasis reproductive and sexual health nationally and internationally. The articles are related to clinical care, service delivery, training, and education in the field of contraception and reproductive/sexual health.

Journal of Research on Adolescence .

This journal is research oriented. It presents methodological and theoretical articles using methods that include multivariate, longitudinal, etc. Studies include ethnographic, experimental, cross-national, and studies of gender, ethnic, and racial diversity.

Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry .

The Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry is the leading journal that focuses exclusively on the psychiatric research and treatment of the child and adolescent. The journal is committed to the advancement of research on pediatric mental health and promoting the mental health of adolescents and their families.

Pediatrics .

This journal addresses the broad needs of the whole child: that is, physiologic, mental, emotional, and social structures. It provides a platform for articles of interest to pediatricians, general medical professionals, and helping professionals.

There are basically two major views and explanations for teenage pregnancy and these views are at odds. One is that teenage pregnancy is a serious problem that requires prevention and intervention. The other is the view articulated by Upadhya and Ellen 2011 that teen pregnancy is an issue of social disparities. Johnson 2014 discusses the association between adolescent pregnancy and poverty. Banerjee, et al. 2009 argues that it is a socially inflicted health hazard. Rich-Edwards 2002 and Lawlor and Shaw 2002 made a similar point that teen pregnancy is not a public health crisis in the United States. Nonetheless, Chambers, et al. 2001 identifies sex, culture, and service needs to reduce the socially inflicted harm. A good example of the problems perspective is explained by Holgate 2012 . As a problem, teenage pregnancy is viewed as something to control and manage. As a health issue, safety is paramount, closely followed by adolescent developmental issues. Regardless of one’s explanation, Calvin, et al. 2009 discusses the rights of teen parents to be involved in decision-making that impacts their family and child or children. Of course, in Linders and Bogard 2014 and Duncan, et al. 2010 there is a real conflict over teenage parenthood. Even so, the reality is that teenage girls, especially young girls who become pregnant, are at risk of physical complications due to the immaturity of their bodies. This is especially problematic among child brides. Becoming pregnant at too young an age comes with many physical risks and problems. Given the social context, even older teens can face daunting-odds when attempting to parent their child or children. The challenge for professionals is to respect the human rights of the adolescent and support her or his physical and emotional needs as a teenager lunging toward adulthood. To improve the outcomes of adolescent pregnancy Montgomery, et al. 2014 addresses the issue through legislation. Macleod 2014 suggests the issues can be better understood and addressed as a feminist issue.

Banerjee, Bratati, G. K. Pandey, Debashis Dutt, Bhaswati Sengupta, Maitrayei Mondal, and Sila Deb. “Teenage Pregnancy: A Socially Inflicted Health Hazard.” Indian Journal of Community Medicine 34 (2009): 227–231.

DOI: 10.4103/0970-0218.55289 Save Citation » Export Citation » Share Citation »

Early marriages are considered a threat to the physical and emotional health of young girls. It is a major concern in rural India. Three steps instituted to enhance family welfare programs improved efforts to prevent pregnancy complications and perinatal outcomes.

Calvin, John, Manouchka Colon, and Kacey Houston. “Decision-Making Rights of Teen Parents.” Michigan Child Welfare Law Journal 12 (2009): 29–42.

The legal right of teenage parents to make autonomous decisions about their children’s care continues to be a concern. The debate over parental rights of minors is in sharp contrast to the limited rights of minors in other areas of the law.

Chambers, Ruth, Gill Wakely, and Steph Chambers. Tackling Teenage Pregnancy: Sex, Culture and Needs . Abingdon, UK: Radcliffe Medical, 2001.

This is an account of Britain dealing with the highest rate of teen pregnancy in Europe. The debate over how to respond to the high rates of teen pregnancy and minimize the risk of social exclusion is delineated. It outlines basic principles that improve services and reduce pregnancy and childbearing.

Duncan, Simon, Rosalind Edwards, and Claire Alexandrer, eds. Teenage Parenthood: What’s the Problem? London: Tufnell, 2010.

This is an examination of why policymakers and the media claim that teenage parenthood ruins a girl’s life and that of her children. It also addresses assertions that teenage pregnancy threatens the wider social and moral fabric of society. Research increasingly shows teenage parenthood does not have to be harmful.

Holgate, Helen. “Young Mothers Speak.” International Journal of Adolescence and Youth 17 (2012): 1–10.

DOI: 10.1080/02673843.2011.649400 Save Citation » Export Citation » Share Citation »

This overview is written from a problems perspective . The author compares problems associated with teen pregnancy from different countries worldwide to illustrate broad variation in causes and problems. The author concludes that many factors are involved in teen pregnancy and many strategies are needed to reduce teen pregnancy rates.

Johnson, Clara L. “ Adolescent Pregnancy and Poverty: Implications for Social Policy .” The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare 1.1 (2014): 17.

This open access article presents research comparing wed and unwed teenage girls. The author concludes that the rate of poverty is the about the same. Both groups were very similar in terms of birth at a young age, incomplete education, low income level, psychological and developmental issues, and social dependency.

Lawlor, Debbie A., and Mary Shaw. “Too Much Too Young? Teenage Pregnancy Is Not a Public Health Problem.” International Journal of Epidemiology 31 (2002): 552–553.

DOI: 10.1093/ije/31.3.552 Save Citation » Export Citation » Share Citation »

The concern over the age at which a young woman should give birth has existed throughout human history. The authors argue that labeling teen pregnancy as a public health problem has little to do with public health and more to do with it being socially, culturally, and economically unacceptable.

Linders, Annulla, and Cynthia Bogard. “Teenage Pregnancy as a Social Problem: A Comparison of Sweden and the United States.” In International Handbook of Adolescent Pregnancy: Medical, Psychosocial, and Public Health Responses . By Andrew Cherry and Mary Dillon, 147–157. New York: Springer Science & Business Media, 2014.

Adolescent pregnancy in the United States is treated as an urgent social problem. Scholars, politicians, interest groups, and media have contributed to this view. In sharp contrast, teenage pregnancy in Sweden is not considered a problem in its own right. The differences are explained and discussed.

Macleod, Catriona. “Adolescent Pregnancy: A Feminist Issue.” In International Handbook of Adolescent Pregnancy: Medical, Psychosocial, and Public Health Responses . By Andrew Cherry and Mary Dillon, 129–145. New York: Springer Science & Business Media, 2014.

This chapter critically examines teen pregnancy from a feminist perspective. The author examines the power relations implicit in the technologies of representation and the technologies of intervention that cohere around the pregnant and parenting teenager.

Montgomery, Tiffany M., Lori Folken, and Melody A. Seitz. “Addressing Adolescent Pregnancy with Legislation.” Nursing for Women’s Health 18.4 (2014): 277–283.

DOI: 10.1111/1751-486X.12133 Save Citation » Export Citation » Share Citation »

This article is helpful in better understanding legislation that addresses adolescent pregnancy. The focus is on legislation related to prevention and education about adolescent pregnancy. Prevention legislation that affects health care clinics, schools, and adolescent-friendly community-based organizations is highlighted. Legislative efforts are viewed as helping address the issue on a macro level.

Rich-Edwards, Janet. “Teen Pregnancy Is Not a Public Health Crisis in the United States: It Is Time We Made It One.” International Journal of Epidemiology 31 (2002): 555–556.

DOI: 10.1093/ije/31.3.555 Save Citation » Export Citation » Share Citation »

The perception of opportunity is postulated as a major factor involved in adolescent pregnancy. The author submits that it is not simply poverty that increases teenage pregnancy it is low levels of optimism about their future among impoverished girls. Adolescent girls with expectations and perceived opportunity do not give birth.

Upadhya, Krishna K., and Jonathan M. Ellen. “Social Disadvantage as a Risk for First Pregnancy among Adolescent Females in the United States.” Journal of Adolescent Health 49 (2011): 538–541.

DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.04.011 Save Citation » Export Citation » Share Citation »

This study examines the underlying determinants of teenage pregnancy that are associated with social disparities that are different for older teens than younger teens. Authors make the case that prevention programs targeting social risk could be improved by addressing developmental stages related to sexuality.

To understand the extent of sexuality among teenagers is to begin to understand teenage pregnancy. Adding ethnic, economic, and global demographics into the calculus helps explain the complexity of what is referred to as teen pregnancy. As well, when teenage fertility is examined over time, in the United States and among the rest of the developed nations, it is clear that teenage pregnancy has been on the decline since the mid-1990s. A good example of the history of the numbers is Smith, et al. 1996 , which looks at trends in the United States from 1960 to 1992, and Abma, et al. 2010 and Ventura, et al. 2011 , which compile data from the National Survey of Family Growth (1991–2008). Dallas 2011 focuses on an area where little research has been conducted, the response by families to the pregnancy of an adolescent. Then again, as Kaufmann, et al. 1998 shows, the decline in teen pregnancy rates is the real story. The conditions that tend to increase and reduce teen pregnancy are more understandable when cross-national social differences are studied. This type of investigation can also benefit from comparing ethnic and racial groups within countries. It is also evident that many of the educational and economic problems identified and faced by pregnant and parenting teens have little or nothing to do with the pregnancy and everything to do with social sanctions and disapproval.

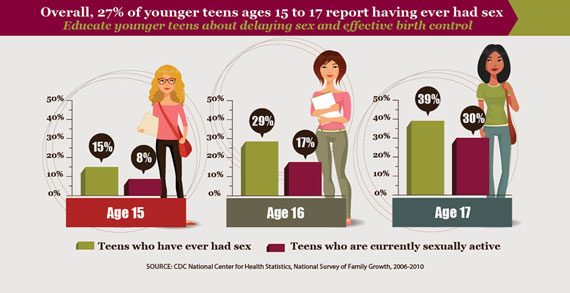

Abma, J. C., G. M. Martinez, and C. E. Copen. “Teenagers in the United States: Sexual Activity, Contraceptive Use, and Childbearing, National Survey of Family Growth 2006–2008.” Vital and Health Statistics 23 (2010): 1–47.

Estimates on the sexual behavior of boys and girls fifteen to nineteen years old regarding sexual activity, contraceptive use, and births are presented from the 1988, 1995, and 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Additional data are reported from two National Survey of Adolescent Males (1988 and 1995).

Dallas, Constance M. Redefining Family for Low-Income, Unmarried African American Adolescent Parents . In Virginia Henderson International Nursing Library’s Online Repository , 2011.

The response by families to the pregnancy of an adolescent is an area where little research has been conducted. In this study the challenges faced by families of unmarried pregnant and parenting girls are studied in light of culture influences and family systems.

Kaufmann, Rachel B., Alison M. Spitz, Lilo T. Strauss, et al. “The Decline in US Teen Pregnancy Rates, 1990–1995.” Pediatrics 102 (1998): 1141–1147.

DOI: 10.1542/peds.102.5.1141 Save Citation » Export Citation » Share Citation »

While teen pregnancies between 1985 and 1990 increased approximately 9 percent, starting in 1991 the rate began to decline. Between 1991 and 1995 teen pregnancies fell about 13 percent to 83.6 per 1,000 births. The conditions and statistics of a decline in pregnancies and abortions are also presented.

Smith, Herbert L., S. Philip Morgan, and Tanya Koropeckyj-Cox. “A Decomposition of Trends in the Nonmarital Fertility Ratios of Blacks and Whites in the United States, 1960–1992.” Demography 33 (1996): 141–151.

DOI: 10.2307/2061868 Save Citation » Export Citation » Share Citation »

Demographic factors believed to increase childbirth among non-married African American and white females in the United States is the subject of this monograph. The rate of the increase in childbearing for all women and teenagers over thirty years (1960–1992) is examined.

Ventura, Stephanie J., Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, T. J. Mathews, Brady E. Hamilton, Paul D. Sutton, and Joyce C. Abma. “Adolescent Pregnancy and Childbirth: United States, 1991–2008.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Surveillance Summaries 60 (2011): 105–108.

Long-term adverse consequences for adolescent mothers and their children are often associated with poorer outcomes than for children of mothers in their early twenties. Fragile family structure, limited long-term resources, and poor social supports rather than age are contributors to poor outcomes. An estimated 82 percent of pregnancies in 2001 among adolescents were unintended.