Advertisement

Urban poverty: Measurement theory and evidence from American cities

- Open access

- Published: 03 August 2021

- Volume 19 , pages 599–642, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Francesco Andreoli ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0751-5520 1 , 2 ,

- Mauro Mussini ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0770-8450 3 ,

- Vincenzo Prete ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3990-0105 1 &

- Claudio Zoli ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3786-4198 1

1006 Accesses

6 Citations

Explore all metrics

We characterize axiomatically a new index of urban poverty that i) captures aspects of the incidence and distribution of poverty across neighborhoods of a city, ii) is related to the Gini index and iii) is consistent with empirical evidence that living in a high poverty neighborhood is detrimental for many dimensions of residents’ well-being. Widely adopted measures of urban poverty, such as the concentrated poverty index, may violate some of the desirable properties we outline. Furthermore, we show that changes of urban poverty within the same city are additively decomposable into the contribution of demographic, convergence, re-ranking and spatial effects. We collect new evidence of heterogeneous patterns and trends of urban poverty across American metro areas over the last 35 years.

Article PDF

Download to read the full article text

Similar content being viewed by others

Understanding trends and drivers of urban poverty in American cities

Population Distribution and Poverty

Across the Rural–Urban Universe: Two Continuous Indices of Urbanization for U.S. Census Microdata

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Let X and Y be k × k matrices. The Hadamard product X ⊙ Y is defined as the k × k matrix with the ( i , j )-th element equal to x i j y i j .

Andreoli, F.: Robust inference for inverse stochastic dominance. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 36 (1), 146–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/07350015.2015.1137758 (2018)

Andreoli, F., Peluso, E.: So close yet so unequal: Neighborhood inequality in American cities. ECINEQ Working paper 2018-477 (2018)

Andreoli, F., Zoli, C.: Measuring dissimilarity. Working Papers Series, Department of Economics, Univeristy of Verona, WP23 (2014)

Andreoli, F., Zoli, C.: From unidimensional to multidimensional inequality: a review. METRON 78 , 5–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40300-020-00168-4 (2020)

Atkinson, A.B.: On the measurement of inequality. J. Econ. Theory 2 , 244–263 (1970)

Baum-Snow, N., Pavan, R.: Inequality and city size. Rev. Econ. Stat. 95 (5), 1535–1548 (2013)

Bayer, P., Timmins, C.: On the equilibrium properties of locational sorting models. J. Urban Econ. 57 (3), 462 – 477. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0094119004001263 (2005)

Bosmans, K.: Distribution-sensitivity of rank-dependent poverty measures. J. Math. Econ. 51 (C), 69–76. https://ideas.repec.org/a/eee/mateco/v51y2014icp69-76.html (2014)

Chetty, R., Hendren, N., Katz, L.F.: The effects of exposure to better neighborhoods on children: New evidence from the moving to opportunity experiment. Amer. Econ. Rev. 106 (4), 855–902. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20150572 (2016)

Chetty, R., Hendren, N.: The impacts of neighborhoods on intergenerational mobility ii: County-level estimates*. Quart. J. Econ. 133 (3), 1163–1228. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjy006 (2018)

Conley, T.G., Topa, G.: Socio-economic distance and spatial patterns in unemployment. J. Appl. Econ. 17 (4), 303–327. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.670 (2002)

Cowell, F.: Measurement of inequality, Vol. 1 of Handbook of Income Distribution, Elsevier, chapter 2, pp. 87–166. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B7RKR-4FF32Y6-5/2/632f8adc6a468d3c17fb25f31b38c86d (2000)

Decancq, K., Fleurbaey, M., Maniquet, F.: Multidimensional poverty measurement with individual preferences. J. Econ. Inequal. 17 (1), 29–49 (2019)

Ebert, U.: The decomposition of inequality reconsidered: Weakly decomposable measures, Mathematical Social Sciences 60 , 94–103 (2010)

Espa, G., Filipponi, D., Giuliani, D., Piacentino, D.: Decomposing regional business change at plant level in italy: A novel spatial shift-share approach. Papers Region. Sci. 93 (S1), S113–S135. https://doi.org/10.1111/pirs.12044 (2014)

Glaeser, E., Resseger, M., Tobio, K.: Inequality in cities. J. Region. Sci. 49 (4), 617–646 (2009)

Iceland, J., Hernandez, E.: Understanding trends in concentrated poverty: 1980-2014. Soc. Sci. Res. 62 , 75–95. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0049089X1630059X (2017)

Jargowsky, P.A., Bane, M.J.: Ghetto Poverty in the United States, 1970-1980, Vol. The Urban Underclass. The Brookings Institution, Washington, pp. 235–273 (1991)

Jargowsky, P.A.: Take the money and run: Economic segregation in U.S. metropolitan areas. Amer. Sociol. Rev. 61 (6), 984–998. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2096304 (1996)

Jargowsky, P.A.: Poverty and Place: Ghettos, Barrios, and the American City. Russell Sage Foundation, New York (1997)

Jargowsky, P.A.: Architecture of segregation. Civil unrest, the concentration of poverty, and public policy, Technical report. The Century Foundation (2015)

Jenkins, S.P., Brandolini, A., Micklewright, J., Nolan, B.: The Great Recession and the distribution of household income. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2013)

Jenkins, S.P., Van Kerm, P.: Assessing individual income growth. Economica 83 (332): 679–703. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecca.12205 (2016)

Kneebone, E.: The changing geography of disadvantage, Shared Prosperity in America’s Communities. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, chapter 3, pp. 41–56 (2016)

Koshevoy, G.A., Mosler, K.: Multivariate Gini indices. J. Multiv. Anal. 60 (2), 252–276. http://ideas.repec.org/a/eee/jmvana/v60y1997i2p252-276.html (1997)

Logan, J.R., Xu, Z., Stults, B.J.: Interpolating U.S. decennial census tract data from as early as 1970 to 2010: A longitudinal tract database. Prof. Geogr. 66 (3), 412–420. PMID: 25140068. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2014.905156 (2014)

Ludwig, J., Duncan, G.J., Gennetian, L.A., Katz, L.F., Kessler, R.C., Kling, J.R., Sanbonmatsu, L.: Neighborhood effects on the long-term well-being of low-income adults. Science 337 (6101), 1505–1510. http://science.sciencemag.org/content/337/6101/1505 (2012)

Ludwig, J., Duncan, G.J., Gennetian, L.A., Katz, L.F., Kessler, R.C., Kling, J.R., Sanbonmatsu, L.: Long-term neighborhood effects on low-income families: Evidence from Moving to Opportunity. Amer. Econ. Rev. 103 (3), 226–31. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.3.226 (2013)

Ludwig, J., Sanbonmatsu, L., Gennetian, L., Adam, E., Duncan, G.J., Katz, L.F., Kessler, R.C., Kling, J.R., Lindau, S.T., Whitaker, R.C., McDade, T.W.: Neighborhoods, obesity, and diabetes - A randomized social experiment. England J. Med. 365 (16), 1509–1519. PMID: 22010917. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1103216 (2011)

Massey, D. S., Eggers, M. L.: The ecology of inequality: Minorities and the concentration of poverty, 1970-1980. Amer. J. Sociol. 95 (5), 1153–1188. https://doi.org/10.1086/229425 (1990)

Massey, D.S., Gross, A.B., Eggers, M.L.: Segregation, the concentration of poverty, and the life chances of individuals. Soc. Sci. Res. 20 (4), 397–420. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0049089X91900204 (1991)

Moretti, E.: Real wage inequality. Amer. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 5 (1), 65–103. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.5.1.65 (2013)

Mussini, M., Grossi, L.: Decomposing changes in CO 2 emission inequality over time: the roles of re-ranking and changes in per capita CO 2 emission disparities. Energy Econ. 49 , 274–281 (2015)

Mussini, M.: Decomposing Changes in Inequality and Welfare Between EU Regions: The Roles of Population Change, Re-Ranking and Income Growth. Soc. Indicat. Res. 130 , 455–478 (2017)

Mussini, M.: Inequality and convergence in energy intensity in the European Union. Appl. Energy 261 , 114371. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306261919320586 (2020)

Oreopoulos, P.: The long-run consequences of living in a poor neighborhood. Quart. J. Econ. 118 (4), 1533–1575. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355303322552865 (2003)

Ravallion, M., Chen, S.: Weakly relative poverty. Rev. Econ. Stat. 93 (4), 1251–1261. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00127 (2011)

Rey, S.J., Smith, R.J.: A spatial decomposition of the Gini coefficient. Lett. Spatial Resour. Sci. 6 , 55–70 (2013)

Sen, A.: Poverty: An ordinal approach to measurement. Econometrica 44 (2), 219–231. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1912718 (1976)

Shorrocks, A.F.: Inequality decomposition by factor components. Econometrica 50 (1), 193–211. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1912537 (1982)

Shorrocks, A. F.: Revisiting the Sen poverty index, Econometrica 63 (5), 1225–1230. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2171728 (1995)

Silber, J.: Factor components, population subgroups and the computation of the Gini index of inequality. Rev. Econ. Stat. 71 , 107–115 (1989)

Thompson, J. P., Smeeding, T. M.: Inequality and poverty in the United States: The aftermath of the Great Recession, FEDS Working Paper No. 2013-51 (2013)

Thon, D.: On measuring poverty. Rev. Income Wealth 25 (4), 429–439. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4991.1979.tb00117.x (1979)

Watson, T.: Inequality and the measurement of residential segregation by income in American neighborhoods. Rev. Income Wealth 55 (3): 820–844. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4991.2009.00346.x (2009)

Wheeler, C.H., La Jeunesse, E.A.: Trends in neighborhood income inequality in the U.S.: 1980–2000. J. Region. Sci. 48 (5), 879–891. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9787.2008.00590.x x (2008)

Wilson, W.: The truly disadvantaged: The inner city, the underclasses and public policy. University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1987)

Zoli, C.: Intersecting generalized Lorenz curves and the Gini index. Soc. Choice Welfare 16 : 183–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s003550050139 (1999)

Download references

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to conference participants at RES 2018 meeting (Sussex), LAGV 2018 (Aix en Provence) and ECINEQ 2019 (Paris) and to two anonymous reviewers for valuable comments. The usual disclaimer applies. Replication code for this article is accessible from the authors’ web-pages. This article forms part of the research project The Measurement of Ordinal and Multidimensional Inequalities (grant ANR-16-CE41-0005-01) of the French National Agency for Research and the NORFACE project IMCHILD: The impact of childhood circumstances on individual outcomes over the life-course (grant INTER/NORFACE/16/11333934/IMCHILD) of the Luxembourg National Research Fund (FNR), whose financial support is gratefully acknowledged.

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Verona within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Economics, University of Verona, Via Cantarane 24, 37129, Verona, Italy

Francesco Andreoli, Vincenzo Prete & Claudio Zoli

Luxembourg Institute of Socio-Economic Research (LISER), MSH, 11 Porte des Sciences, L-4366, Esch-sur-Alzette/Belval Campus, Luxembourg

Francesco Andreoli

Department of Economics, Management and Statistics, University of Milano-Bicocca, Piazza dell’Ateneo Nuovo 1, 20126, Milan, Italy

Mauro Mussini

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Francesco Andreoli .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix A: Proofs

1.1 a.1 proof of theorem 1.

We will prove the theorem making use of a sequence of lemmas that will highlight the role of the different axioms in the derivation of the final result.

Let \(\mathcal {A} \in {\Omega }\) , ζ ∈ [0, 1), and z ≥ 1, U P (.; ζ ) satisfies AGG and INV-S if and only if there exist a continuous function \(A:[0,1]^{2}\rightarrow \mathbb {R}_{+}\) and a function \(h:[0,1]\rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) continuous in (0,1) with h (0) = 0 such that:

with \(\bar {N}_{0}:=0\) .

The proof combines the effect of AGG with INV-S by deriving a functional restriction on the class of weighting functions \(w_{i} \left (\frac {N_{1}}{N},\ldots ,\frac {N_{i}}{N},\ldots ,\frac {N_{n}}{N}\right )\) that appear in the definition of AGG. We leave to the reader to verify that the index in Eq. 4 satisfies AGG and INV-S, here we focus on the proof of the (only if) part of the statement in the lemma.

First recall that, given AGG, we can write

where \(A:[0,1]^{2}\rightarrow \mathbb {R}_{+}\) and \(w_{i}: {\Delta }_{n}\rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) satisfy the conditions specified in AGG.

Let z ≥ 1, we apply INV-S. Note that because of the definition of INV-S, the scaling component \(A\left (\frac {P}{N}, \frac {\bar {P}_{z}}{\bar {N}_{z}}\right )\) of Eq. 5 is not affected by splitting operations. Thus INV-S only affects the component \({\sum }_{i=1}^{z} \frac {N_{i}}{N} \cdot \left (\frac {P_{i}}{N_{i}} - \zeta \right ) \cdot {w_{i}} \left (\frac {N_{1}}{N}, \ldots , \frac {N_{i}}{N}, \ldots , \frac {N_{n}}{N}\right )\) .

We construct the proof in two steps. We first derive the restrictions on the function w 1 (.) and then in a recursive manner we derive also the restrictions on all the other functions w i (.) for i = 2, 3,…, n .

We first note that the function w i (.) does not depend on ζ , and then we set ζ such that for a given \(\mathcal {A} \in {\Omega }\) we have that n = z . Note that for any \(\mathcal {A} \in {\Omega }\) there exist values of ζ such that n = z , for instance this is the case if we let ζ = 0.

Step 1. Suppose that n = z = 2, and assume that \(\frac {P_{1}}{N_{1}} >\zeta \) , while \(\frac {P_{2}}{N_{2}}=\zeta \) . Apply repeatedly the splitting operations over the neighborhood indexed by i = 2. Because of the invariance requirement in INV-S and the specification in Eq. 5 , if we denote by \(\hat {n}_{i}:=\frac {N_{i}}{{N}}\) we obtain that \(\hat {n}_{1} \left (\frac {P_{1}}{N_{1}} - \zeta \right ) \cdot w_{1} (\hat {n}_{1}, 1-\hat {n}_{1}) = \hat {n}_{1} \left (\frac {P_{1}}{N_{1}} - \zeta \right ) \cdot w_{1} (\hat {n}_{1}, \hat {n}_{2}, \hat {n}_{3}, \ldots , \hat {n}_{z})\) with \(\hat {n}_{2} + \hat {n}_{3} + {\ldots } + \hat {n}_{z} = 1-\hat {n}_{1}\) , this result holds for all z = n ≥ 2. Recalling that \(\frac {P_{1}}{N_{1}} - \zeta >0\) , we then obtain

with \(\hat {n}_{2} + \hat {n}_{3} +\ldots +\hat {n}_{z}=1-\hat {n}_{1}\) , for all z = n ≥ 2 and \(\hat {n}_{1}\in (0,1)\) . We can thus define the function \(h:[0,1]\rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) such that \(h(\hat {n}):=\hat {n} w_{1} (\hat {n}, 1-\hat {n})\) . It then follows that by definition

for all z = n ≥ 2 and \(\hat {n}_{1}\in (0,1)\) . Given that by AGG \(\hat {n}_{1} w_{1}(\hat {n}_{1},1-\hat {n}_{1})\) is continuous for \(\hat {n}_{1}\in (0,1)\) then h (.) is continuous on (0,1).

Step 2. Let z = n = 1, and assume to split into two neighborhoods the neighborhood 1 where \(\frac {P_{1}}{N_{1}}-\zeta >0\) , then one obtains two neighborhoods of relative sizes \(\hat {n}_{1}\) and \(1-\hat {n}_{1}\) . INV-S then implies that \(w_{1}(1) = \hat {n} w_{1} (\hat {n},1-\hat {n}) + (1- \hat {n}) w_{2} (\hat {n},1-\hat {n})\) . Let h (1) := w 1 (1), then one obtains for z = n = 2, \((1-\hat {n}) w_{2}(\hat {n},1-\hat {n})=w_{1}(1)-\hat {n} w_{1} (\hat {n},1-\hat {n})\) , that is \((1-\hat {n}) w_{2} (\hat {n},1-\hat {n}) = h(1)-h(\hat {n})\) , in other words \((1-\hat {n}) w_{2}(\hat {n},1-\hat {n})=h(\hat {n}+(1-\hat {n})) - h(\hat {n})\) . This gives the definition of w 2 (.) for z = n = 2.

The argument could be further generalized. Let z = n = 2, assume that \(\frac {P_{1}}{N_{1}}>\zeta \) , while \(\frac {P_{2}}{N_{2}}=\zeta \) . Then split neighborhood 1 of relative size \(\hat {n}\) into two neighborhoods of relative sizes respectively \(\hat {n}_{1}\) and \(\hat {n}_{2}\) such that \(\hat {n}_{1} + \hat {n}_{2}=\hat {n}\) , and, either leave neighborhood 2 unaffected, or split it into many others. According to INV-S it follows that \(\hat {n} \left (\frac {P_{1}}{N_{1}} - \zeta \right ) \cdot w_{1} (\hat {n},1-\hat {n})=\hat {n}_{1} \left (\frac {P_{1}}{N_{1}} - \zeta \right ) w_{1}(\hat {n}_{1},\hat {n}_{2},\hat {n}_{3},\ldots ,\hat {n}_{z^{\prime }}) + \hat {n}_{2} \left (\frac {P_{1}}{N_{1}} - \zeta \right ) w_{2}(\hat {n}_{1},\hat {n}_{2},\hat {n}_{3},\ldots , \hat {n}_{z^{\prime }})\) where \(z^{\prime } = n\geq 3\) and \(\hat {n}_{3}+\ldots + \hat {n}_{z^{\prime }} = 1-\hat {n}=1-\hat {n}_{1}-\hat {n}_{2}\) .

That is, \((\hat {n}_{1}+\hat {n}_{2}) \cdot w_{1} (\hat {n}_{1} + \hat {n}_{2}, 1-\hat {n}_{1}-\hat {n}_{2})=\hat {n}_{1}w_{1}(\hat {n}_{1},\hat {n}_{2},\hat {n}_{3},\ldots ,\hat {n}_{z^{\prime }}) + \hat {n}_{2} w_{2}(\hat {n}_{1},\hat {n}_{2},\hat {n}_{3},\ldots ,\hat {n}_{z^{\prime }})\) . Recalling that \(\hat {n}_{1} w_{1} (\hat {n}_{1},\hat {n}_{2},\hat {n}_{3},\ldots ,\hat {n}_{z}) = h(\hat {n}_{1})\) for all z = n ≥ 2 and \(\hat {n}_{1}\in (0,1)\) , one obtains

for all \(z^{\prime } = n\geq 2\) and \(\hat {n}_{1} + \hat {n}_{2}\in (0,1],\hat {n}_{1},\hat {n}_{2}\in (0,1)\) .

By replicating the same logic and splitting into three neighborhoods the first one, then one can derive the definition of w 3 (.) from

for all \(z^{\prime } = n\geq 3\) and \(\hat {n}_{1}+\hat {n}_{2}+\hat {n}_{3}\in (0,1],\hat {n}_{1},\hat {n}_{2},\hat {n}_{3}\in (0,1)\) .

We can then obtain in general that \(\frac {N_{i}}{\bar {N}_{z}} \cdot w_{i} \left (\frac {N_{1}}{\bar {N}_{z}},\ldots , \frac {N_{i}}{\bar {N}_{z}},\ldots , \frac {N_{z}}{\bar {N}_{z}}\right ) =h \left (\frac {\bar {N}_{i}}{\bar {N}_{z}}\right ) - h\left (\frac {\bar {N}_{i-1}}{\bar {N}_{z}}\right )\) for i = 1, 2,…, z and z = n where \(\frac {\bar {N}_{0}}{\bar {N}_{z}}:=0\) and h (0) := 0. If z = n then we have that \(\bar {N}_{z}=N\) , leading to

for i = 1, 2,…, n where \(\frac {\bar {N}_{0}}{N}:=0\) and h (0) := 0.

As pointed out the function w i (.) does not depend on ζ , therefore even if it is derived under the assumption that ζ is such that z = n , the specification also holds for any ζ ∈ [0, 1), and therefore for any z ≤ n , provided that z ≥ 1 as required in the definition of AGG. □

Let \(\mathcal {A}\in {\Omega }\) , ζ ∈ [0, 1), and z ≥ 1, U P (.; ζ ) satisfies AGG, INV-S, INV-T if and only if there exist a continuous functions \(A:[0,1]^{2}\rightarrow \mathbb {R}_{+}\) and \(\beta _{0},\gamma _{0}\in \mathbb {R}\) such that:

We take the result from Lemma 1 and investigate the implications on the specification of U P (.; ζ ) generated by further imposing INV-T. We leave to the reader to check that the obtained specification of U P (.; ζ ) satisfies all axioms, here we focus on the “only if” part of the lemma.

For z = 1, INV-T does not hold. Note that when z = 1 the specification of U P (.; ζ ) in the lemma is consistent with the one derived in Lemma 1 where h (1) = β 0 if z = n = 1. While the specification in the lemma for h (.) that is valid also when z = 1 < n , will be obtained in the next general part of the proof.

We set z ≥ 2 and consider the transfers involved in the definition of INV-T. Note that with z = 2, the axiom is satisfied by construction given that it involves two transfers of population taking place in opposite directions and therefore their effects cancel out leading to the initial configuration \(\mathcal {A}\) .

Without loss of generality we assume that there are z ≥ 2 neighborhoods with highly concentrated poverty with \(\frac {P_{i}}{N_{i}} \geq \zeta \) and such that their population size is equal, that is N i = N 0 for i = 1, 2,…, z . It follows that their relative population size within this set of neighborhoods is \(\frac {N_{i}}{\bar {N}_{z}} = \frac {1}{z}\) , with \(\frac {\bar {N}_{i}}{\bar {N}_{z}} = \frac {i}{z}\) .

Moreover, we consider first the case where ζ ∈ [0, 1) is such that for a given \(\mathcal {A}\in {\Omega }\) we have z = n ≥ 2.

Consider the effect of the combined transfers of population in INV-T, and apply them to the specification derived in Lemma 1. Note that these transfers take place among neighborhoods in {1, 2,…, z } and do not affect the components \(A\left (\frac {P}{N}, \frac {\bar {P}_{z}}{\bar {N}_{z}}\right )\) and \(\left [h\left (\frac {\bar {N}_{i}}{N}\right ) - h \left (\frac {\bar {N}_{i-1}}{N}\right )\right ]\) but only the distributions of \(\left (\frac {P_{i}}{N_{i}} - \zeta \right )\) . The application of the transfers in INV-T leads to the following condition

for ε > 0, satisfying the conditions specified in INV-T for all i , j ∈{1, 2,…, z − 1} with z = n ≥ 2.

It then follows that \(\left [h\left (\frac {j+1}{z}\right ) - h\left (\frac {j}{z}\right )\right ] - \left [h\left (\frac {j}{z}\right ) - h\left (\frac {j-1}{z}\right )\right ] = \left [h\left (\frac {i+1}{z}\right ) - h\left (\frac {i}{z}\right )\right ] - \left [h\left (\frac {i}{z}\right ) - h\left (\frac {i-1}{z}\right )\right ]\) for all i , j ∈{1, 2,…, z − 1}, and for all z = n ≥ 2. Thus, we have that \(\left [h\left (\frac {i+1}{z}\right ) - h\left (\frac {i}{z}\right )\right ] - \left [h\left (\frac {i}{z}\right ) - h\left (\frac {i-1}{z}\right )\right ]\) does not depend on i but eventually only on 1/ z . In general, there exists a function g (1/ z ) such that

for all i ∈{1, 2,…, z − 1}, all z = n ≥ 2.

To simplify the exposition, denote \(\frac {1}{z}=\sigma \) and let f ( i ) := h ( i σ ) for a fixed σ . We then have

Let d ( i ) := f ( i ) − f ( i − 1) for i ∈{1, 2,…, z − 1} with by construction f (0) = h (0) = 0. Thus, d (1) + d (2) + … + d ( i ) = f ( i ) − f (0) = f ( i ). We then have

for i ∈{1, 2,…, z − 1}, that leads to d ( j ) = d (1) + ( j − 1) g ( σ ) for i ∈{1, 2,…, z } and all z = n ≥ 2.

Thus, \(f(i)={\sum }_{j=1}^{i}d(j) = {\sum }_{j=1}^{i}d(1) +(j-1)g (\sigma )\) , with f (1) = d (1). It follows that

for i ∈{1, 2,…, z }, z = n ≥ 2. Recalling that f ( i ) := h ( i / z ) we have

for i ∈{1, 2,…, z }, z = n ≥ 2. Given that i and z can take any pair of natural number values such that i ≤ z = n , and that h (0) = 0 by construction, then the above formula is a functional equation that allows to specify the value of the function h (.) for all rational numbers in [0, 1].

Let i = z , we then obtain

note that the value of h (1) is constant and therefore independent from z , rearranging it then follows that for any z = n ≥ 2 it holds that

Recalling the derivation of \(h\left (\frac {i}{z}\right )\) and inserting \(h\left (\frac {1}{z}\right )\) one obtains

for i ∈{1, 2,…, z }, z = n ≥ 2.

Note that \(\frac {i}{z}\) are unaffected if both i and z = n are replicated r times for r ∈{1, 2, 3, 4,…}, we then obtain \(h\left (\frac {i}{z} \right ) = h\left (\frac {ri}{rz}\right ) = h(1) \frac {ri}{rz} - \frac {ri(rz-ri)}{2}g \left (\frac {1}{rz}\right ) =h(1) \frac {i}{z}-r^{2} \frac {i(z-i)}{2}g \left (\frac {1}{rz}\right )\) for all r . As a result it should hold that

for all r , z ∈{2, 3, 4,…} with z = n , thus, \(g\left (\frac {1}{rz}\right ) = \frac {1}{r^{2}}g \left (\frac {1}{z}\right )\) . By switching z with r one obtains \(g\left (\frac {1}{rz}\right ) = \frac {1}{z^{2}}g \left (\frac {1}{ r}\right )\) . As a result \(\frac {1}{r^{2}}g \left (\frac {1}{z}\right ) = \frac {1}{z^{2}}g \left (\frac {1}{r}\right )\) for all r , z ∈{2, 3, 4,…}, that is, \(z^{2}g \left (\frac {1}{z}\right ) =r^{2}g \left (\frac {1}{r}\right )\) for all r , z . Thus, there exists a constant \(\gamma _{0}\in \mathbb {R}\) such that \(z^{2}g\left (\frac {1}{z}\right ) =-\gamma _{0}\) , leading to \(g\left (\frac {1}{z}\right ) =-\frac {\gamma _{0}}{z^{2}}\) for all z ∈{2, 3, 4,…}. By substituting into the definition of \(h\left (\frac {i}{z}\right )\) and letting \(h(1) =\beta _{0}\in \mathbb {R}\) it follows that \(h\left (\frac {i}{z}\right ) =\beta _{0}\frac {i}{z}+\frac {\gamma _{0}}{2} \frac {i}{z} \frac {(z-i)}{z}\) . Note that we have derived the specification of h (.) under the assumption that z = n ≥ 2, then replacing z with n we obtain

Recall that \(\frac {i}{n}\) by construction could be any rational number in (0, 1], with h (0) = 0 already set in Lemma 1. Given that the set of rational numbers is dense in (0, 1] and that h (.) is continuous in that interval the result could be extended to all real numbers in [0, 1], with h (0) = 0. Recalling that \(\frac {\bar {N}_{i}}{N} =\frac {i}{n}\) we can then write more generally

Consider the weighting function \(\left [ h\left (\frac {\bar {N}_{i}}{N}\right ) - h\left (\frac {\bar {N}_{i-1}}{N}\right )\right ]\) from Lemma 1, it can then be specified as:

By substituting into the specification of \(UP(\mathcal {A};\zeta )\) in Lemma 1, one obtains the results presented in this lemma.

Recall that we have derived the result under the assumption that for ζ ∈ [0, 1) we have z = n ≥ 2 and note that the function h (.) does not depend on ζ . In order to extend the result to all cases where n ≥ z ≥ 2 it needs to be checked that the obtained functional form for h (.) allows to satisfy INV-T also when z < n . Note that, as in Eq. 7 , the application of the transfers in INV-T when n > z ≥ 2 requires that the following condition

has to be satisfied for all i , j ∈{1, 2,…, z − 1}, for n > z ≥ 2, for ε > 0. That is, after substituting for the derived specification of \(h\left (\frac {\bar {N}_{i}}{N}\right ) - h\left (\frac {\bar {N}_{i-1}}{N}\right )\) , it should be verified that

Note that \(\left [h\!\left (\frac {\bar {N}_{i}}{N}\right ) - h\!\left (\frac {\bar {N}_{i-1}}{N}\right )\right ] - \left [h\left (\frac {\bar {N}_{i+1}}{N}\right ) - h\!\left (\frac {\bar {N}_{i}}{N}\right ) \right ]\) equals \(\beta _{0} \frac {N_{i}}{N} + \frac {\gamma _{0}}{2} \frac {N_{i}}{N} \!\left (\frac {(N-\bar {N}_{i})-\bar {N}_{i-1}}{N}\right )\! -\) \(\beta _{0} \frac {N_{i+1}}{N} - \frac {\gamma _{0}}{2} \frac {N_{i+1}}{N} \left (\frac {(N-\bar {N}_{i+1})-\bar {N}_{i}}{N}\right )\) , and recall that according to INV-T N i = N j = N i + 1 = N j + 1 it then follows that

This is similarly the case if we consider the neighborhood with index j . As a result INV-T holds also for n > z ≥ 2.

To complete the exposition we consider the case where n > z = 1. In this case INV-T cannot be applied, however we have already derived the required specifications for function h (.) from the previous steps of the proof. □

Let \(\mathcal {A}\in {\Omega }\) , ζ ∈ [0, 1), U P (.; ζ ) satisfies AGG, INV-S, INV-T, INV-PL, MON, TRAN and NOR if and only if there exist β , γ ≥ 0 such that:

with \(\bar {N}_{0}:=0\) , if z ≥ 1, otherwise \(UP(\mathcal {A};\zeta )=0\) .

We consider the result from Lemma 2 and investigate the implications on the specification of U P (.; ζ ) generated by further imposing INV-PL, MON, TRAN and NOR. We leave to the reader to check that the obtained specification of U P (.; ζ ) satisfies all axioms, here we focus on the “only if” part of the lemma. Recall that, if z ≥ 1, then according to Lemma 2 it is possible to write

We first consider INV-PL(i). By applying the scale component λ > 0 one obtains that from \(\mathcal {A}\) to \(\mathcal {A}^{\prime }\) the values \(\left (\frac {P}{N}, \frac {\bar {P}_{z}}{\bar {N}_{z}}, \frac {P_{i}}{N_{i}}, \zeta \right )\) are scaled to \(\left (\lambda \frac {P}{N}, \lambda \frac {\bar {P}_{z}}{\bar {N}_{z}}, \lambda \frac {P_{i}}{N_{i}}, \lambda \zeta \right ) \) , it then follows that \(UP(\mathcal {A};\zeta )=UP(\mathcal {A}^{\prime }; \lambda \zeta )\) if and only if \(A\left (\frac {P}{N}, \frac {\bar {P}_{z}}{\bar {N}_{z}}\right ) = \lambda A\left (\lambda \frac {P}{N}, \lambda \frac {\bar {P}_{z}}{\bar {N}_{z}}\right ) \geq 0\) .

We take into account two cases, first when ζ = 0 and then when ζ ∈ (0, 1).

Case 1: ζ = 0. In this case holds only INV-PL(i). If ζ = 0 then \(\frac {P}{N}=\frac {\bar {P}_{z}}{\bar {N}_{z}}\) . By applying INV-PL(i) it then follows that \(A \left (\frac {P}{N}, \frac {P}{N}\right ) = \lambda A\left (\lambda \frac {P}{N}, \lambda \frac {P}{N}\right )\) for λ > 0. Let \(\lambda \frac {P}{N}=1\) , we obtain \(A \left (\frac {P}{N}, \frac {P}{N}\right ) = \frac {A(1,1)}{\frac {P}{N}}\) , letting A (1, 1) := K ≥ 0, then \(A\left (\frac {P}{N}, \frac {P}{N}\right ) = \frac {K}{\frac {P}{N}}\) .

Case 2: ζ ∈ (0, 1]. In this case \(\frac {P}{N} \leq \zeta \leq \frac {\bar {P}_{z}}{\bar {N}_{z}} \leq 1\) . INV-PL(i) holds if and only if \(A\left (\frac {P}{N}, \frac {\bar {P}_{z}}{\bar {N}_{z}}\right ) = \lambda A\left (\lambda \frac {P}{N}, \lambda \frac {\bar {P}_{z}}{\bar {N}_{z}}\right ) \geq 0\) for λ > 0. Moreover, according to INV-PL(ii) one obtains \(A\left (\frac {P}{N}, \frac {\bar {P}_{z}}{\bar {N}_{z}}\right ) = A\left (\frac {P}{N}, \frac {\bar {P}_{z}}{\bar {N}_{z}} + \theta \right )\) where \(\frac {P}{N}<\zeta \leq \frac {\bar {P}_{z}}{\bar {N}_{z}}\) . By INV-PL(ii) it follows that there exists a continuous function H (.) such that \(A\left (\frac {P}{N}, \frac {\bar {P}_{z}}{\bar {N}_{z}}\right ) := H\left (\frac {P}{N}\right )\) whenever \(\frac {P}{N} < \zeta \leq \frac {\bar {P}_{z}}{\bar {N}_{z}}\) . Note that \(\frac {P}{N} = \frac {\bar {P}_{z}}{\bar {N}_{z}} \frac {\bar {N}_{z}}{N} + \left (1-\frac {\bar {N}_{z}}{N}\right ) \zeta ^{\prime }\) for \(\zeta ^{\prime } < \zeta \) , where \(\zeta ^{\prime }\) denotes the average poverty incidence of the neighborhood with incidence below ζ . By letting \(\bar {N}_{z} \rightarrow 0\) and \({\zeta }^{\prime } \rightarrow {\zeta }\) one obtains the case where \(\frac {P}{N} \rightarrow \zeta \) . We then have that \(A\left (\frac {P}{N}, \frac {\bar {P}_{z}}{\bar {N}_{z}}\right ) = H\left (\frac {P}{N}\right )\) for \(\frac {P}{N} < \frac {\bar {P}_{z}}{\bar {N}_{z}}\) . Thus, by INV-PL(i) we have \(\lambda A \left (\lambda \frac {P}{N}, \lambda \frac {\bar {P}_{z}}{\bar {N}_{z}}\right ) = \lambda H \left (\lambda \frac {P}{N} \right ) = H\left (\frac {P}{N}\right ) = A\left (\frac {P}{N}, \frac {\bar {P}_{z}}{\bar {N}_{z}}\right )\) for \(\frac {P}{N}<\frac {\bar {P}_{z}}{\bar {N}_{z}}\) and for λ > 0 such that \(\lambda \frac {\bar {P}_{z}}{\bar {N}_{z}}\leq 1\) . Suppose that there exists \(\bar {c}\) such that \(\lambda \frac {P}{N}=\bar {c}\) , then \(\lambda H\left (\lambda \frac {P}{N} \right ) = H\left (\frac {P}{N}\right )\) implies that \(\frac {\bar {c}H \left (\bar {c}\right )}{\frac {P}{N}} = H\left (\frac {P}{N}\right )\) . By letting \(\bar {c} H (\bar {c}) := K\geq 0\) one obtains that \(A\left (\frac {P}{N}, \frac {\bar {P}_{z}}{\bar {N}_{z}}\right ) = H\left (\frac {P}{N}\right ) = \frac {K}{\frac {P}{N}}\) for \(\frac {P}{N} < \frac {\bar {P}_{z}}{\bar {N}_{z}}\) .

Thus, we have that both

for \(\frac {P}{N} < \frac {\bar {P}_{z}}{\bar {N}_{z}} \leq 1\) and for \(\frac {P}{N} = \frac {\bar {P}_{z}}{\bar {N}_{z}} \leq 1\) that identify all possible ranges of values of the arguments of A (.).

By applying the result to the specification in Lemma 2, and letting β := β 0 K and γ := γ 0 K /2 one obtains

We now investigate the effects of MON and TRAN. According to MON considering that \(UP(\mathcal {A}^{\prime }; \zeta ) = {\sum }_{i=1}^{z} \left (\frac {\nu P_{i}}{\nu P} - \zeta \frac {N_{i}}{\nu P} \right ) \cdot \left [\beta + \gamma \left (\frac {(N-\bar {N}_{i}) - \bar {N}_{i-1}}{N}\right )\right ]\) for ν > 1, it should hold \(UP(\mathcal {A}^{\prime }; \zeta ) - UP(\mathcal {A}; \zeta )\geq 0\) , this requires that

for all ν > 1, all ζ ∈ [0, 1), all \(\mathcal {A}\in {\Omega }\) . Rearranging the condition, it implies that

for all ν > 1, all ζ ∈ [0, 1), all \(\mathcal {A}\in {\Omega }\) .

This is the case if and only if \({\sum }_{i=1}^{z} \frac {N_{i}}{N} \cdot \left [\beta +\gamma \left (\frac {(N-\bar {N}_{i})-\bar {N}_{i-1}}{N}\right )\right ] \geq 0\) for all \(\mathcal {A}\in {\Omega }\) . This condition depends on the value of z ≥ 1, and in particular, because of the construction of the weighting function w i (.) that satisfies INV-S, the condition depends only on \(\frac {\bar {N}_{z}}{N}\) . In fact, in this case, because of INV-S, without loss of generality, one can consider distributions with two neighborhoods and z = 1. In this case \(N_{1} = \bar {N}_{1} = \bar {N}_{z}\) and recall that \(\bar {N}_{0}=0\) . After substituting, one obtains the condition

for all \(\frac {\bar {N}_{z}}{N}\in (0,1]\) . Letting \(\frac {\bar {N}_{z}}{N} =1\) , that is if z = n , it follows that a necessary condition for MON to hold is β ≥ 0. Moreover, letting \(\frac {\bar {N}_{z}}{N}\rightarrow 0\) , the additional derived necessary condition is β + γ ≥ 0, because otherwise, if γ < − β for sufficiently small values of \( \frac {\bar {N}_{z}}{N}\) is possible to violate the condition in Eq. 10 . Both necessary conditions β ≥ 0 and β + γ ≥ 0 turn out to be sufficient for Eq. 10 to hold for all \(\frac {\bar {N}_{z}}{N}\in (0,1]\) .

We consider now the restrictions required by axiom TRAN. First we consider the case where, because of the transfer, the poverty incidence in neighborhood j does not fall below ζ , that is \(P_{j}^{\mathcal {A}^{\prime }}/{N}_{j}^{\mathcal {A}^{\prime }}\geq \zeta \) .

Recall moreover, that according to TRAN the considered transfer does not affect the ranking of the neighborhoods. Consider Eq. 9 and note that according to TRAN, only P i and P j are modified by the transfer, it should then be verified that

for j > i , with j ≤ z , and ε > 0. Thus

with \(\bar {N}_{j} - \bar {N}_{i}>0\) and \(\bar {N}_{j-1} - \bar {N}_{i-1}>0\) , which implies

as a result should hold γ ≥ 0.

Note that the condition should hold for all i < j ≤ z with z ≤ 2 and therefore letting z = n , should hold for all i < j ≤ n .

We consider now the case where \({P}_{j}^{\mathcal {A}^{\prime }}/{N}_{j}^{\mathcal {A}^{\prime }}<\zeta \) , with j = z , by applying TRAN, it follows that

where \(0\leq \varepsilon ^{\prime } \leq \varepsilon \) with \(\varepsilon ^{\prime } = {\min \limits } \{\varepsilon ,P_{j}-\zeta N_{j} \}\) . The condition can then be simplified as

Recalling that \(\frac {(N - \bar {N}_{i}) - \bar {N}_{i-1}}{N} > \frac {(N-\bar {N}_{j}) - \bar {N}_{j-1}}{N}\) for j > i , that \(\varepsilon ^{\prime } \leq \varepsilon \) , and that β ≥ 0, then γ ≥ 0 is sufficient to verify that \(UP(\mathcal {A}^{\prime };\zeta ) \geq UP(\mathcal {A};\zeta )\) .

Thus, γ ≥ 0 is necessary and sufficient for TRAN to hold. By combining with the parametric restrictions derived by applying MON one obtains β ≥ 0, and γ ≥ 0.

All derivations illustrated so far consider the case where z ≥ 1. Note that for \(\mathcal {A}\in {\Omega }\) and given ζ ∈ (0, 1) it is possible to take into account also configurations where \(\frac {P_{i}}{N_{i}}<\zeta \) for all neighborhoods i . In this case the value of the index is derived by considering axiom NOR. For all these configurations the value of the index coincides with the infimum of the index taken over all the other possible configurations in \(\mathcal {A}\) where z ≥ 1. Consider the obtained derivation of UP for z ≥ 1, where

with β , γ ≥ 0, note that the first term in the summation \(\frac {P_{i} - \zeta N_{i}}{P}\geq 0\) is non-increasing in i , and that the term \(\frac {(N-\bar {N}_{i}) - \bar {N}_{i-1}}{N}\) is also non-increasing in i . It follows that, given that β , γ ≥ 0 also \(\beta +\gamma \left (\frac {(N-\bar {N}_{i}) - \bar {N}_{i-1}}{N}\right )\) is non-increasing in i . The summation in Eq. 11 is then minimized, for each z ≥ 1 if the terms \(\frac {P_{i} - \zeta N_{i}}{P}\) are equalized. Given that \(\frac {P_{i}-\zeta N_{i}}{P}\geq 0\) then the minimum for each z ≥ 1 is obtained for P i − ζ N i = 0 for all i ≤ z . It follows that in this case U P = 0.

Thus, by NOR the value of the index is 0 when \(\frac {P_{i}}{N_{i}}<\zeta \) for all i .

To complete the proof we rearrange the specification of U P (.; ζ ) in Eq. 11 . We can rewrite:

in fact \({\sum }_{i=1}^{z} N_{i} \left (\bar {N}_{z} - \bar {N}_{i} - \bar {N}_{i-1}\right ) = {\sum }_{i=1}^{z} N_{i} \bar {N}_{z} - {\sum }_{i=1}^{z} N_{i} (\bar {N}_{i} + \bar {N}_{i-1}) = (\bar {N}_{z})^{2} - {\sum }_{i=1}^{z} (\bar {N}_{i} - \bar {N}_{i-1}) (\bar {N}_{i} + \bar {N}_{i-1})\) where \({\sum }_{i=1}^{z} (\bar {N}_{i} - \bar {N}_{i-1}) (\bar {N}_{i} + \bar {N}_{i-1}) = {\sum }_{i=1}^{z} (\bar {N}_{i})^{2} - (\bar {N}_{i-1})^{2} = (\bar {N}_{z})^{2}\) . It then follows that the term \({\sum }_{i=1}^{z} \left (\frac {P_{i}-\zeta N_{i}}{P}\right ) \cdot \left (\frac {(\bar {N}_{z} - \bar {N}_{i}) - \bar {N}_{i-1}}{\bar {N}_{z}} \right )\) simplifies to \({\sum }_{i=1}^{z} \frac {P_{i}}{P} \cdot \left (\frac {(\bar {N}_{z} - \bar {N}_{i}) - \bar {N}_{i-1}}{\bar {N}_{z}}\right )\) . Thus, we obtain:

In order to complete the proof of the Theorem one has to link the result in Lemma 3 with the Gini index formula \(G(\mathcal {A};\zeta )\) . Next lemma provides this link.

Let \(\mathcal {A}\in {\Omega }\) , ζ ∈ [0, 1), and z ≥ 1, then

The Gini index G (.; ζ ) can be written as follows:

We now develop the first term appearing in squared brackets in Eq. 12 , denoted \(\max \limits \) in short-hand notation, to show that it can written as a function of the rank weights. First, let develop the double summations term as follows:

After subtracting \({\sum }_{i=1}^{z} \frac {N_{i}}{\bar {N}_{z}} \frac {P_{i}}{N_{i}}\) we obtain

As a result \(\bar {P}_{z}G(\mathcal {A};\zeta )={\sum }_{i=1}^{z} P_{i} \left (\frac {\bar {N}_{z} - \bar {N}_{i}}{\bar {N}_{z}} - \frac {\bar {N}_{i-1}}{\bar {N}_{z}}\right )\) , after dividing both sides by P we obtain the result in the lemma. □

By substituting from Lemma 4 into the specification of Lemma 3 in Eq. 8 for z ≥ 1, we obtain the specification of U P (.; ζ ) in the Theorem for z ≥ 1 :

To complete the proof we show that all axioms are independent , meaning that it is possible to derive alternative functional forms for U P (.; ζ ) by dropping one of the axioms and considering all the others.

Drop NOR: consider Eq. 3 for z ≥ 1 and set U P (.; ζ ) = k < 0 in all other cases.

Drop TRAN: consider Eq. 3 with γ = − 1 and β = 0 for z ≥ 1, and set \(UP(.;\zeta )=-\sup \{\frac {{\bar {N}_{z}}}{N}\frac {\bar {P}_{z}}{P}\cdot G(\mathcal {A};\zeta )+\frac {N{-\bar {N}_{z}}}{N}{\frac {\bar {P}_{z}-\zeta {\bar {N}_{z}}}{P}}:\mathcal {A}\in {\Omega } \) with z ≥ 1} in all other cases.

Drop MON: consider Eq. 3 with γ = 0 and β = − 1 for z ≥ 1, and set U P (.; ζ ) = − 1 in all other cases.

Drop INV-PL: consider Eq. 3 multiplied by P / N for z ≥ 1, and set U P (.; ζ ) = 0 in all other cases.

Drop INV-T: consider

with \({\bar {N}_{0}:=0}\) for z ≥ 1, and set U P (.; ζ ) = 0 in all other cases.

Drop INV-S: consider

for z ≥ 1, and set U P (.; ζ ) = 0 in all other cases.

Drop AGG: consider

for z ≥ 1, and set U P (.; ζ ) = 0 in all other cases. QED.

1.2 A.2 Proof of Corollary 4

Let \(p_{i}=\frac {P_{i}}{N_{i}}\) and \(s_{i}=\frac {N_{i}}{N}\) denote the poverty incidence and population share of neighborhood i , respectively.

Let \(\mathbf {p} = \left (p_{1},\ldots ,p_{n}\right )^{T}\) be the n × 1 vector of neighborhood poverty rates sorted in decreasing order and \(\mathbf {s} = \left (s_{1}, \ldots , s_{n}\right )^{T}\) be the n × 1 vector of the corresponding population shares. A urban poverty configuration is fully identified by the pair ( s , p ), and is used interchangeably. Let 1 n being the n × 1 vector with each element equal to 1, P is the n × n skew-symmetric matrix:

where \(\bar {p}\) is the overall poverty rate in the city. The elements of P are the n 2 relative pairwise differences between the neighborhood poverty incidences as ordered in p . Let \(\mathbf {S}=\mathit {diag}\left \{\mathbf {s}\right \}\) be the n × n diagonal matrix with diagonal elements equal to the population shares in s , and G be a n × n G -matrix (a skew-symmetric matrix whose diagonal elements are equal to 0, with upper diagonal elements equal to − 1 and lower diagonal elements equal to 1) (Silber 1989 ). The Gini index of urban poverty is expressed in matrix form:

where the matrix \(\tilde {\mathbf {G}}=\mathbf {S}\mathbf {G}\mathbf {S}\) is the weighting G -matrix, a generalization of the G -matrix introduced by Mussini and Grossi ( 2015 ) to add weights in the calculation of the Gini index. The change in urban poverty from t to \(t^{\prime }\) is measured by the difference between the Gini index in \(t^{\prime }\) and the Gini index in t :

Equation 18 can be broken down into three components by applying the matrix approach used in Mussini and Grossi ( 2015 ) and in Mussini ( 2017 ). The three components separate the contributions of changes in neighborhood population shares, ranking of neighborhoods and disparities between neighborhood poverty rates. Let \(\mathbf {s}_{t|t^{\prime }}\) stand for the n × 1 vector of the t population shares arranged by the decreasing order of the corresponding \(t^{\prime }\) poverty rates. Let \(\lambda = \bar {p}_{t^{\prime }}/\bar {p}_{t^{\prime }|t}\) be the ratio of the actual \(t^{\prime }\) overall poverty rate to the fictitious \(t^{\prime }\) overall poverty rate which is the weighted average of \(t^{\prime }\) poverty rates where the weights are the corresponding population shares in t . After defining \(\mathbf {S}_{t|t^{\prime }} = \mathit {diag} \left \{\mathbf {s}_{t|t^{\prime }}\right \}\) , the Gini index of \(t^{\prime }\) neighborhood poverty rates calculated by using the t neighborhood population shares is

where \(\tilde {\mathbf {G}}_{t|t^{\prime }} = \mathbf {S}_{t|t^{\prime }}\mathbf {G}\mathbf {S}_{t|t^{\prime }}\) is the weighting G -matrix obtained by using the neighborhood population shares in t instead of those in \(t^{\prime }\) . In Eq. 22 , the multiplication of \({\mathbf {P}}_{t^{\prime }}^{T}\) by λ ensures that the pairwise differences between the \(t^{\prime }\) neighborhood poverty incidences are divided by \(\bar {p}_{t^{\prime }|t}\) instead of \(\bar {p}_{t^{\prime }}\) . By adding and subtracting \(G\left (\mathbf {s}_{t|t^{\prime }},\mathbf {p}_{t^{\prime }}\right )\) in Eq. 21 , the contribution to Δ U P due to changes in neighborhood population shares can be separated from that attributable to changes in disparities between neighborhood poverty rates:

where \(\mathbf {W} = \tilde {\mathbf {G}}_{t^{\prime }} - \lambda \tilde {\mathbf {G}}_{t|t^{\prime }}\) . Component W measures the effect of changes in neighborhood population shares. A positive value of W indicates that the weights assigned to more unequal pairs of neighborhoods are larger in \(t^{\prime }\) than in t , increasing urban poverty from t to \(t^{\prime }\) . A negative value of W indicates that the weights assigned to more unequal pairs of neighborhoods are smaller in \(t^{\prime }\) than in t , reducing urban poverty.

The difference enclosed within square brackets on the right-hand side of Eq. 23 can be additively split into two components: one component measuring the re-ranking of neighborhoods, a second component measuring the change in disparities between neighborhood poverty rates. Let \(\mathbf {p}_{t^{\prime }|t}\) be the n × 1 vector of \(t^{\prime }\) neighborhood poverty rates sorted in decreasing order of the respective t neighborhood poverty rates, and B be the n × n permutation matrix re-arranging the elements of \(\mathbf {p}_{t^{\prime }}\) to obtain \(\mathbf {p}_{t^{\prime }|t}\) , that is \(\mathbf {p}_{t^{\prime }|t} = \mathbf {B}\mathbf {p}_{t^{\prime }}\) . Matrix \(\mathbf {P}_{t^{\prime }|t} = \left (1/\bar {p}_{t^{\prime }|t}\right ) \left (\mathbf {1}_{n}\mathbf {p}^{T}_{t^{\prime }|t}-\mathbf {p}_{t^{\prime }|t}\mathbf {1}^{T}_{n}\right )\) contains the n 2 relative pairwise differences between the neighborhood poverty rates as arranged in \(\mathbf {p}_{t^{\prime }|t}\) . The concentration index of the \(t^{\prime }\) neighborhood poverty rates sorted by the t neighborhood poverty rates, calculated by using the t population shares, is defined as follows:

By using permutation matrix B , the concentration index \(C\left (\mathbf {s}_{t},\mathbf {p}_{t^{\prime }|t}\right )\) can be re-written as a function of \(\mathbf {P}_{t^{\prime }}\) instead of \(\mathbf {P}_{t^{\prime }|t}\) . Since \(\mathbf {P}_{t^{\prime }|t}=\mathbf {B}\lambda \mathbf {P}_{t^{\prime }}\mathbf {B}^{T}\) , the concentration index \(C\left (\mathbf {s}_{t}, \mathbf {p}_{t^{\prime }|t}\right )\) expressed as a function of \(\mathbf {P}_{t^{\prime }}\) becomes

By adding \(C\left (\mathbf {s}_{t},\mathbf {p}_{t^{\prime }|t}\right )\) as expressed in Eq. 24 and subtracting it as expressed in Eq. 25 to the difference enclosed within square brackets on the right-hand side of Eq. 23 , we obtain

where \(\mathbf {R}=\tilde {\mathbf {G}}_{t|t^{\prime }}-\mathbf {B}^{T}\tilde {\mathbf {G}}_{t}\mathbf {B}\) and \(\mathbf {D}=\mathbf {P}_{t^{\prime }|t}-\mathbf {P}_{t}\) . Component R measures the effect of re-ranking of neighborhoods from t to \(t^{\prime }\) and its contribution to the change in urban poverty is always non-negative. The nonzero elements of R indicate the pairs of neighborhoods which have re-ranked from t to \(t^{\prime }\) .

Component D measures the effect of disproportionate changes in neighborhood poverty rates. The generic ( i , j )-th element of D compares the relative difference between the t poverty rates of the neighborhoods in positions j and i in p t with the relative difference between the \(t^{\prime }\) poverty rates of the same two neighborhoods in \(\mathbf {p}_{t^{\prime }|t}\) . A positive (negative) value of D indicates that relative disparities in neighborhood poverty rates have increased (decreased) from t to \(t^{\prime }\) , increasing (reducing) urban poverty. If all neighborhood poverty rates have changed in the same proportion from t to \(t^{\prime }\) , then D = 0.

Given Eqs. 23 and 26 , a three-term decomposition of Δ U P is obtained:

Since component D would not reveal changes in neighborhood poverty rates if all neighborhood poverty rates changed in the same proportion, this component is split into two further terms: one measuring the change in the city poverty rate, the second measuring the changes in disparities between neighborhood poverty rates by assuming that the city poverty rate remains the same from t to \(t^{\prime }\) . Let c stand for the change in the city poverty rate by assuming that neighborhood population shares are unchanged from t to \(t^{\prime }\) :

Let \({\mathbf {p}}_{t^{\prime }|t}^{c} = \mathbf {p}_{t} + c\mathbf {p}_{t}\) be the vector of neighborhood poverty rates we would observe in \(t^{\prime }\) if every neighborhood poverty rate changed by proportion c . This implies that \({\bar {p}}_{t^{\prime }|t}^{c} = \bar {p}_{t^{\prime }|t}\) . Vector \(\mathbf {p}_{t^{\prime }|t}\) can be expressed as

where the elements of vector \({\mathbf {p}}_{t^{\prime }|t}^{\delta }\) are the element-by-element differences between vectors \(\mathbf {p}_{t^{\prime }|t}\) and \({\mathbf {p}}_{t^{\prime }|t}^{c}\) . Since \({\mathbf {p}}_{t^{\prime }|t}^{c}=\mathbf {p}_{t}+c\mathbf {p}_{t}\) , \(\mathbf {p}_{t^{\prime }|t}\) can be re-written as

where the elements of \(\mathbf {p}^{e}_{t^{\prime }|t}\) account for disproportionate changes in neighborhood poverty rates from t to \(t^{\prime }\) , as \(\mathbf {p}^{e}_{t^{\prime }|t}\) would equal p t if there were no disproportionate changes in neighborhood poverty rates. Given equations above, matrix \(\mathbf {P}_{t^{\prime }|t}\) can be written as

Since matrix D in Eq. 27 is obtained by subtracting P t from \(\mathbf {P}_{t^{\prime }|t}\) , D can be re-written as

By replacing D in Eq. 27 with its expression in Eq. 31 , the decomposition of the change in urban poverty becomes

1.3 A.3 Proof of Corollary 5

Building on the Rey and Smith ( 2013 ) spatial decomposition of the Gini index and the spatial decomposition of the change in inequality in Mussini ( 2020 ), Δ U P , W , R and E can be broken down into spatial components. Let N t be the n × n spatial weights matrix having its ( i , j )-th entry equal to 1 if and only if the ( i , j )-th element of P t is the relative difference between the poverty rates of two neighborhoods that are spatially close, otherwise the ( i , j )-th element of N t is 0. Using the Hadamard product, Footnote 1 the relative pairwise differences between the poverty rates of neighborhoods that are spatially close can be selected from P t :

For each pair of neighborhoods, the relative difference between their \(t^{\prime }\) poverty rates in \(\mathbf {P}^{e}_{t^{\prime }|t}\) has the same position as the relative difference between their t poverty rates in P t . Thus, N t also selects the relative pairwise differences between neighbors from \(\mathbf {P}^{e}_{t^{\prime }|t}\) :

Since \(\mathbf {E} = \mathbf {P}^{e}_{t^{\prime }|t}-\mathbf {P}_{t}\) , the Hadamard product between N t and E is a matrix with nonzero elements equal to the elements of E pertaining to neighborhoods that are spatially close:

Let \(\mathbf {N}_{t^{\prime }}\) be the n × n spatial weights matrix having its ( i , j )-th entry equal to 1 if and only if the ( i , j )-th element of \(\mathbf {P}_{t^{\prime }}\) is the relative difference between the poverty rates of two neighborhoods that are spatially close, otherwise the ( i , j )-th element of \(\mathbf {N}_{t^{\prime }}\) is 0. The Hadamard product of \(\mathbf {N}_{t^{\prime }}\) and \(\mathbf {P}_{t^{\prime }}\) is the matrix

The nonzero elements of \(\mathbf {P}_{N,t^{\prime }}\) are the relative pairwise differences between the \(t^{\prime }\) poverty rates of neighborhoods that are in spatial proximity.

The decomposition of the change in the neighborhood component of urban poverty is obtained by replacing \(\mathbf {P}_{t^{\prime }}\) and E in Eq. 32 with \(\mathbf {P}_{N,t^{\prime }}\) and E N , respectively:

Let J n be the matrix with diagonal elements equal to 0 and extra-diagonal elements equal to 1, the matrix with nonzero elements equal to the relative pairwise differences between the \(t^{\prime }\) poverty rates of neighborhoods that are not in spatial proximity is

The matrix selecting the elements of E pertaining to the pairs of neighborhoods that are not spatially close is

The decomposition of the change in the non-neighborhood component of urban poverty is obtained by replacing \(\mathbf {P}_{t^{\prime }}\) and E in Eq. 32 with \(\mathbf {P}_{nN,t^{\prime }}\) and E n N , respectively:

Given Eqs. 40 and 37 , the spatial decomposition of the change in urban poverty is

Appendix B: Additional results

Urban poverty calculated by using balanced longitudinal data and raw data on census tracts in American MSAs, from 1980 to 2014

Urban poverty and poverty incidence in the city, from 1980 to 2014

Urban poverty estimates based on poverty thresholds at 75%, 100% and 200% of the official poverty line, years 1980 and 2014

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Andreoli, F., Mussini, M., Prete, V. et al. Urban poverty: Measurement theory and evidence from American cities. J Econ Inequal 19 , 599–642 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-020-09475-2

Download citation

Received : 15 July 2019

Accepted : 03 November 2020

Published : 03 August 2021

Issue Date : December 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-020-09475-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Concentrated poverty

- Decomposition

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 30 May 2024

Escaping poverty: changing characteristics of China’s rural poverty reduction policy and future trends

- Yunhui Wang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8824-6109 1 na1 ,

- Yihua Chen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9089-4172 2 , 3 na1 &

- Zhiying Li ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2219-5473 4

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 694 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

327 Accesses

Metrics details

- Development studies

- Social policy

Eliminating poverty is a shared aspiration of people worldwide. This article analyzes 762 rural poverty-related texts promulgated and implemented by the Chinese Government since 1984 using content analysis based on a three-dimensional framework encompassing the time of policy issuance, policy goals, and types of policy instruments. The study outlines the overall landscape and evolutionary context of the policy system. The results show that, during absolute poverty governance, China’s rural poverty governance can be broadly divided into three stages: regional development-oriented poverty alleviation, comprehensive poverty alleviation, and targeted poverty alleviation. Based on the production-oriented welfare model, economic development became the primary goal of poverty alleviation policies, while insufficient attention was given to service support and capacity-building goals. The alleviation of poverty mainly relied on the propulsive force generated by supply-side policy instruments led by the Government and the external driving force generated by environmental policy instruments, with a significant deficiency in the propulsive force produced by demand-side policy instruments. Entering the phase of relative poverty governance, optimizing poverty governance policy instruments requires breaking free from path dependence, following the evolutionary pattern of poverty governance. It involves ensuring that policy instruments support economic development while emphasizing addressing service support and capacity-building goals. It is crucial to increase the frequency of using demand-side policy instruments, stimulate their pulling force on poverty alleviation, and achieve a trend of evolutionary innovation and the collaborative governance of policy instruments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Does the BRI contribute to poverty reduction in countries along the Belt and Road? A DID-based empirical test

Feminization of poverty: an analysis of multidimensional poverty among rural women in China

The effects of China’s poverty eradication program on sustainability and inequality

Problem statement.

The aspiration to eliminate poverty has been a longstanding societal ideal since ancient times. It represents an intrinsic right for people across the globe in their pursuit of a fulfilling life. The elimination of hunger and poverty, central targets outlined in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, also stands as a cornerstone in the development agendas of numerous nations worldwide. Rowntree’s ( 1902 ) early definition of poverty in 1902 classified it as primary and secondary poverty. He argued that a family is in poverty when its total income fails to meet the essential survival needs of its members. This concept is considered the foundation of research into absolute poverty. Essentially, absolute poverty is a physiological concept that explores the link between nutrition and survival (Lister, 2021 ). As economic and social development advances, Peter Townsend contends that absolute poverty overlooks the social and cultural aspects of ‘human need,’ both ‘need’ and ‘poverty’ are products of social construction. “Both ‘need’ and ‘poverty’ are social constructs.” Townsend ( 1979 ) introduced the concept of relative poverty, which signifies exclusion from typical social lifestyles and activities. However, Sen ( 1982 ) proposed in “Poverty and Famine” that the core of poverty lies in the lack of viability rather than mere low income. Alongside research, countries generally categorize poverty into absolute and relative forms. Research shows that most of the world’s impoverished population resides in rural areas (Poverty and Initiative, 2018 ). The capacity of rural people to elevate themselves from poverty holds profound implications for their daily sustenance and global food security. The United Nations and countries worldwide are working to eradicate rural poverty by promoting inclusive growth and sustainable livelihoods.

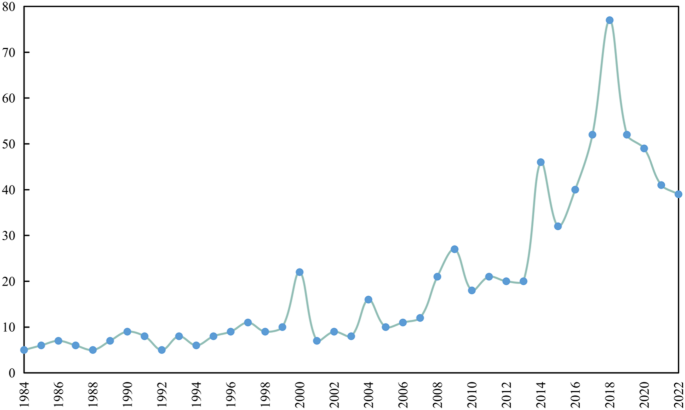

As an agricultural powerhouse with a massive rural populace, China’s countryside constituted over 80% of its total population in the nascent years following the establishment of the People’s Republic. The rapid economic growth brought about by the reform and opening-up has also exacerbated the development gap between urban and rural areas. The natural and economic factors that have long impeded rural development have become more pronounced, with the hollowing out of the countryside, the aging of the population, the abandonment of infrastructure, environmental degradation, and persistent poverty drawing the Government’s attention. In 1978, 250 million rural residents living under the poverty threshold of 100 RMB annual per capita income represented a 30.7% rural poverty rate Footnote 1 (see Fig. 1 ). Alleviating rural poverty thus emerged as an urgent priority fettering China’s socioeconomic advancement. Since the 1980s, the Chinese Government has embarked on large-scale anti-poverty initiatives in the countryside, promulgating numerous policies that achieved remarkable success in eradicating absolute poverty. From 1985 to 2000, the rural absolute impoverished population rapidly declined from 125 million to 32.09 million, with poverty rates plummeting dramatically from 14.8% to 3.5%. Upon entering the 21st century, both the quantity and incidence of rural absolute poverty persisted in substantial decreases. In 2015, the Central Government further proposed targeted poverty alleviation targets. By 2020, China had accomplished its poverty alleviation targets, eliminating destitution under extant standards.

The rural poor population and poverty incidence rate for 1985–2000 were calculated using the 1978 poverty standard per capita net income of 100 yuan; the rural poor population and poverty incidence rate for 2000–2020 were calculated using the 2010 poverty standard per capita net income of 2300 yuan—data from China Statistical Yearbook.

Governance refers to the process by which a variety of governmental and non-governmental institutions and actors work together to establish conditions for social order and collective action (Stoker, 2012 ). It involves diverse approaches employed by individuals and institutions, both public and private, to manage public affairs. This ongoing process entails cooperative actions, including the implementation of formal institutional arrangements and the agreement on informal arrangements that align with their interests (The Commission on Global Governance, 1995 ). Kooiman and Jentoft ( 2009 ) introduced three essential elements of governance: imagery, instruments, and action. Imagery refers to the rationale behind governance, encompassing vision, judgment, beliefs, and goals, typically grounded in systematic values or knowledge systems. Instruments involve the selection and application of governance methods, serving as intermediaries that connect imagery to action. Action, in turn, represents the practical implementation of these “instruments”. Poverty governance in China constitutes a collaborative effort among the government, market, and society, with a focus on people’s interests, aimed at achieving common prosperity. It encompasses both economic and social dimensions, with the goal of reducing poverty, protecting the rights of the impoverished, and enhancing social equity. In this fight against poverty, which is the largest and most robust in the history of human poverty alleviation, China has taken many original and unique major governance initiatives and accumulated a series of replicable and generalizable experiences in poverty alleviation. However, eliminating absolute poverty does not mean there is no poverty in China, and China is still far from achieving high-quality and high-standard poverty alleviation (Zhou et al., 2020 ). Poverty presents dynamic, multifaceted challenges, including policy-dependent severe behaviors (Wan et al., 2021 ) and the objectivity that relative poverty cannot be entirely eradicated (Hagenaars, 2014 ). With China’s elimination of absolute poverty, the Government’s poverty alleviation focus has shifted from abolishing destitution to alleviating relative hardship (Shen and Li, 2022 ). Given the evolving forms and aims of poverty governance, the period of relative poverty alleviation necessitates continued efforts to prevent regression and enact efficacious policies to mitigate dependence. There is an urgent need to clarify questions about optimal relative poverty governance policies and how they differ from periods of absolute poverty governance. However, current literature exhibits limited systematic investigation into the textual content of absolute rural poverty policies. This study offers an original contribution by analyzing policy texts to reveal changes in China’s poverty reduction policy from the absolute to relative poverty governance periods.

This paper examines the Chinese Government’s rural poverty alleviation policies over time, utilizing content analysis to address two key questions: First, what characterized the Government’s poverty governance model during absolute poverty governance, and what was the operational logic? Second, in the relative poverty governance period, how is pro-poor policy logically related to absolute poverty governance, and what policies should the Government adopt? Answering these questions scientifically can delineate dynamic changes in China’s rural absolute poverty policy instruments, analyze the utility and limitations of existing pro-poor instruments, and inform suggestions to optimize relevant policies moving forward. The research aims to contribute Chinese experiences and insights to the broader cause of international poverty alleviation. Examining the evolution of poverty governance models and policy instruments across periods of absolute and relative poverty has implications for developing effective, context-specific poverty reduction strategies tailored to contemporary implementation environments.

Literature review

Research of the typology of policy instruments.

Policy instruments, sometimes called government or governance instruments, represent the government’s strategies and actions to attain policy targets (Hughes, 2017 ). No universal standard exists for categorizing policy instruments, leading researchers to classify them based on distinct characteristics and targets. Dahl and Lindblom ( 1953 ) have proposed a classification of instruments into regulatory and non-regulatory categories based on their authority attributes; Owen E. Hughes categorizes policy instruments into four distinct groups: government supply, production, subsidies, and regulation, based on the Government’s functions (Hughes, 2017 ); Rothwell and Zegveld categorize policy instruments into three groups: supply, environmental, and demand, considering their intended purposes Howlett and Remash distinguish among voluntary, hybrid, and coercive instruments based on the level of coercion (Howlett et al., 1995 ).

Based on typological analyses and investigations of policy instruments, some scholars have also directed their attention to the factors that influence the choice and utilization of policy instruments to better achieve policy targets in intricate public policy decision-making and implementation contexts. Several studies have emphasized the “fit” of policy instruments, whereby the selection of these instruments is associated with policy targets, the development of state capacity, civil society (Howlett et al., 1995 ), temporal characteristics, field-specific attributes, instrument attributes, and policy strength, all of which impact the effectiveness of policy instrument configurations (Zhang et al., 2022 ). This concept captures the degree of alignment between the selection of policy instruments and specific conditions. In line with this notion, research has conducted empirical analyses of the selection and allocation of policy instruments in specific domains, such as China’s research and development of new energy vehicles (Shao et al., 2021 ), low-carbon city pilot programs (Hong et al., 2021 ), and government attention to the power sector (Cheng and Yang, 2023 ).

Chinese scholars emphasize the role of the Government as a policy solution provider and prefer the “supply-demand-environment” policy instrument classification framework proposed by Rothwell and Zegveld (Rothwell and Zegveld, 1984 ) when conducting policy instrument research and apply it to environmental governance (Liao, 2018 ), energy policy (Li et al., 2023 ; Yang et al., 2021 ), and photovoltaic poverty alleviation (Zhang et al., 2018 ), among other policy area studies.

The selection of policy instruments in poverty alleviation research

In several developing countries, the implementation of measures such as increased financial support, infrastructure development, and enhanced educational levels plays a crucial role in elevating the income of impoverished individuals and stimulating economic growth in disadvantaged regions (Arsani et al., 2020 ; Cross and Neumark, 2021 ; Deepika and Sigi, 2014 ; Mugo and Kilonzo, 2017 ; Page and Pande, 2018 ). This pattern extends to China as well. With the growing focus on policy instrument research, the policy instrument perspective has become increasingly prominent in examining various policy domains (Peters, 2020 ). Nonetheless, the literature concerning inductive analysis utilizing policy instrument typology, grounded in the attributes and characteristics of poverty alleviation, remains exceedingly scarce. Although a substantial portion of research related to poverty alleviation centers on specific policy measures, it remains pertinent.

Promoting industrial development is a paramount strategy in pursuing poverty eradication. As elucidated by Mariara and Kiriti ( 2020 ), the advancement of the industrial sector can bring about more substantial benefits for impoverished communities by facilitating the organization and active participation of rural populations within the industrial framework. It enhances production efficiency and reshapes production dynamics, ultimately culminating in economic development-driven poverty alleviation. Furthermore, Economic development can also be attained through strategic infrastructure development. Zhou et al. ( 2023 ) found that transport infrastructure can significantly enhance economic development, especially public investment in poor areas, and therefore, infrastructure development should be a priority policy option.

Poverty alleviation through education represents an enduring mechanism for sustained poverty reduction. Song ( 2012 ) explored the influence of primary education on China’s labor market, discovering that universal access to primary education yielded a significant reduction in poverty within China, with urban areas particularly benefiting from this effect. Liu et al. ( 2023 ) found that compulsory education more effectively addresses rural poverty than upper-secondary education. The Government should prioritize implementing compulsory education as a long-term policy instrument in rural areas, recognizing its potency in poverty alleviation.

The empowerment of underprivileged individuals can be aptly realized through talent development and expanding employment opportunities. Guo and Wang ( 2021 ) found that rural labor transfer augments the per capita livelihood capital of the remaining population and facilitates the escape from vulnerability and the attainment of stable employment among the impoverished. The significance of government service support for impoverished segments of society should not be underestimated. Yang and Cao ( 2022 ) revealed that augmenting the provision of fundamental public services in rural areas constitutes a crucial strategy for alleviating rural poverty, significantly reducing the incidence of such poverty. Furthermore, Jiang et al. ( 2020 ) uncovered that engaging farmers in underdeveloped and impoverished regions of China in savings and commercial insurance can effectively diminish poverty vulnerability. Deng ( 2019 ) also found that savings and commercial insurance can reduce health expenditures where catastrophic or poverty-inducing levels occur.

The primary approach to poverty alleviation is intricately linked to the formulation and execution of public policies. Government-led initiatives constitute a crucial facet of China’s poverty governance, highlighting the pivotal role of policy instrument selection and allocation. Scholarly investigations have delved into using policy instruments in poverty alleviation, enriching our comprehension of related policies. Nonetheless, research combining policy instruments to scrutinize pro-poor policy evolution remains limited (Zhang et al., 2018 ), with a dearth of comprehensive examinations that draw on policy instrument theory to elucidate pro-poor policy change and optimization recommendations. Consequently, this study commences when the Chinese Government launched large-scale poverty alleviation efforts, focusing on central policy documents closely associated with poverty alleviation between 1984 and 2022. It employs content analysis to conduct text mining of standardized policy documents, dissecting the semantic information conveyed by specific word frequencies and frequencies within the policy texts across various phases. When coupled with coding results, these findings facilitate the categorization and quantitative analysis of policy instruments for poverty alleviation, enabling a comprehensive discussion on their application in poverty governance.

Analytical framework and research methods

Policy text selection.

The sample for this study is primarily obtained from the Peking University-Chinese Laws and Regulations Database. Focus on policy samples regarding poverty alleviation and reduction from 1984 to 2022. First, utilizing the keywords “poverty, poverty reduction, poverty alleviation, help, and special hardship,” examining central laws and regulations, and conducting a full-text search for the timeframe up to November 2, 2022, is necessary. To ensure the comprehensiveness of the policy texts, this study supplemented the selected policies by using the policy repositories on the official websites of the State Council, the State Council’s Bureau of Rural Revitalization, and various government agencies.

Furthermore, this study follows specific policy selection criteria to ensure the representativeness of the selected policy document: first, the government-issued policy texts are heavily linked to poverty alleviation and reduction efforts. To accurately reflect the national Government’s attitudes and actions towards poverty alleviation, the literature must directly outline their measures. The literature’s scope should encompass policy documents from different areas of social development; second, the selected texts mainly include notices, announcements, opinions and methods, decisions, and other policy documents from the central Government and its supervised ministries and commissions. Finally, the study selected 762 policy texts that met its needs.

Policy analysis framework

Policy instruments are one of the most important ways to study and analyze public policies. As the primary means and effective way of government management, policy instruments have an essential impact on the implementation effect of public policies. China’s poverty alleviation policies have been regularly adjusted in response to changing goal circumstances, making the timing of policy implementations a crucial element in tracking the evolution and forecasting future trends of poverty alleviation in the country. The policy target is the core element of public policy, an essential criterion for measuring the degree of response to public problems, and it also determines the means chosen to achieve the target. Hence, this paper examines the trends in China’s anti-poverty policy from three perspectives: policy initiation time, policy targets, and policy instruments.

Time dimension. This paper analyzes the characteristics and influencing factors of China’s poverty alleviation policies in different periods by examining the quantitative trends and evolution of policies over time. Starting from the period of the Chinese Government’s large-scale poverty alleviation efforts, we will examine the development of these policies in a historical context.

Policy goal dimension. In order to sort out China’s anti-poverty policies in a more detailed way, China’s anti-poverty policy targets will be divided into specific categories based on the value of the targets. For a long time, China’s rural poor groups generally have had poor economic conditions, lack of ability, and insufficient support and assistance groups. Given this, this paper divides anti-poverty policy targets into three major categories: economic development category, capacity-building category, and service support category. The economic development category is to improve the infrastructure construction and economic development level of poor areas to drive the poor groups out of poverty and become rich. The service support category provides various services and policy support for developing poor groups, such as employment skills training, policy promotion and interpretation, and information and counseling services for poor groups. Capacity building focuses on the self-development awareness of poor groups and the cultivation and enhancement of their capacities to make up for the shortcomings of development and strengthen the endogenous motivation for poverty alleviation and enrichment.

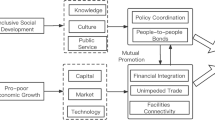

Policy instruments dimension. Each classification of policy instruments has specific application scenarios, and their combination and comprehensive use aims to maximize effectiveness and synergistic value. However, the policy instrument model Roy Rothwell and Walter Zegveld developed is more comprehensive and operational from a comparative standpoint (Dylander, 1980 ). The analytical framework presents a downgraded view of the complex policy system, focusing on the instruments and measures for operationalizing policy instruments. It highlights the dual effectiveness of intra-dimensional aggregation and inter-dimensional differentiation to aid in identifying each policy instrument’s content and boundaries, thus simplifying the presentation of specific operations. Due to the superiority of this policy model, it has been widely used in policy research in many fields, such as economic development (Eisinger, 1988 ), environmental pollution prevention (Qin and Youhai, 2020 ), and public health care (Yue et al., 2020 ). Concurrently, within the realm of rural poverty governance in China, the backing furnished by both central and local governments for poverty alleviation development, the cultivation of a propitious economic, social, and legal milieu through high-level strategic planning to steer and oversee the trajectory of development in the sphere of poverty alleviation, alongside the emphasis placed on the regulatory functions of central and local governments in shaping poverty alleviation policies in line with market and societal demands to address the genuine requirements of impoverished segments of society, all underscore the pivotal role of government macroeconomic control.

These strategies primarily hinge on the implementation paths meticulously devised by policymakers to attain their designated policy targets. They exhibit a substantial congruence with the internal logic and external utility of supply-side, environment-side, and demand-side policy instruments. Consequently, this approach serves as a valuable analytical instrument within this paper.

Supply-side instruments refer to the Government’s role as a provider, taking the necessary measures to ensure the basic livelihood security of people experiencing poverty and to improve the quality of life and development motivation of people experiencing poverty, specifically including financial inputs, information services, talent training, and infrastructure construction. Demand-side instruments measures refer to the Government’s efforts to stimulate consumption in poverty-stricken areas by promoting poverty alleviation markets, expanding poverty alleviation channels, and promoting poverty alleviation industries, including government purchase, service outsourcing, market shaping, and collaborative exchanges. Environment-side instruments refer to the strong guarantee provided by the Government to create a favorable external environment for poverty alleviation, strengthen the elements of poverty alleviation, and stimulate the endogenous impetus, specifically target planning, regulatory control, tax incentives, and guiding publicity. Examining the policy instruments’ specific measures makes it possible to understand the differentiation of the anti-poverty governance approach, the existing problems, and the direction of future improvement.