Rigour in qualitative case-study research

Affiliation.

- 1 School of Nursing and Midwifery Studies, National University of Ireland, Galway. [email protected]

- PMID: 23520707

- DOI: 10.7748/nr2013.03.20.4.12.e326

Aim: To provide examples of a qualitative multiple case study to illustrate the specific strategies that can be used to ensure the credibility, dependability, confirmability and transferability of a study.

Background: There is increasing recognition of the valuable contribution qualitative research can make to nursing knowledge. However, it is important that the research is conducted in a rigorous manner and that this is demonstrated in the final research report.

Data sources: A multiple case study that explored the role of the clinical skills laboratory in preparing students for the real world of practice. Multiple sources of evidence were collected: semi-structured interviews (n=58), non-participant observations at five sites and documentary sources.

Discussion: Strategies to ensure the rigour of this research were prolonged engagement and persistent observation, triangulation, peer debriefing, member checking, audit trail, reflexivity, and thick descriptions. Practical examples of how these strategies can be implemented are provided to guide researchers interested in conducting rigorous case study research.

Conclusion: While the flexible nature of qualitative research should be embraced, strategies to ensure rigour must be in place.

- Nursing Research / methods

- Nursing Research / standards*

- Qualitative Research*

- Cancer Nursing Practice

- Emergency Nurse

- Evidence-Based Nursing

- Learning Disability Practice

- Mental Health Practice

- Nurse Researcher

- Nursing Children and Young People

- Nursing Management

- Nursing Older People

- Nursing Standard

- Primary Health Care

- RCN Nursing Awards

- Nursing Live

- Nursing Careers and Job Fairs

- CPD webinars on-demand

- --> Advanced -->

- Clinical articles

- Expert advice

- Career advice

- Revalidation

Case-study research Previous Next

Rigour in qualitative case-study research, catherine houghton lecturer, school of nursing and midwifery studies, national university of ireland, galway, dympna casey senior lecturer, school of nursing and midwifery studies, national university of ireland, galway, david shaw lecturer, open university, milton keynes, uk, kathy murphy head of school, school of nursing and midwifery studies, national university of ireland, galway.

Aim To provide examples of a qualitative multiple case study to illustrate the specific strategies that can be used to ensure the credibility, dependability, confirmability and transferability of a study.

Background There is increasing recognition of the valuable contribution qualitative research can make to nursing knowledge. However, it is important that the research is conducted in a rigorous manner and that this is demonstrated in the final research report.

Data sources A multiple case study that explored the role of the clinical skills laboratory in preparing students for the real world of practice. Multiple sources of evidence were collected: semi-structured interviews ( n = 58), non-participant observations at five sites and documentary sources.

Discussion Strategies to ensure the rigour of this research were prolonged engagement and persistent observation, triangulation, peer debriefing, member checking, audit trail, reflexivity, and thick descriptions. Practical examples of how these strategies can be implemented are provided to guide researchers interested in conducting rigorous case study research.

Conclusion While the flexible nature of qualitative research should be embraced, strategies to ensure rigour must be in place.

Nurse Researcher . 20, 4, 12-17. doi: 10.7748/nr2013.03.20.4.12.e326

None declared

This article has been subject to double blind peer review

Received: 02 May 2012

Accepted: 18 September 2012

Multiple case study research - rigour

User not found

Want to read more?

Already have access log in, 3-month trial offer for £5.25/month.

- Unlimited access to all 10 RCNi Journals

- RCNi Learning featuring over 175 modules to easily earn CPD time

- NMC-compliant RCNi Revalidation Portfolio to stay on track with your progress

- Personalised newsletters tailored to your interests

- A customisable dashboard with over 200 topics

Alternatively, you can purchase access to this article for the next seven days. Buy now

Are you a student? Our student subscription has content especially for you. Find out more

01 March 2013 / Vol 20 issue 4

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DIGITAL EDITION

- LATEST ISSUE

- SIGN UP FOR E-ALERT

- WRITE FOR US

- PERMISSIONS

Share article: Rigour in qualitative case-study research

We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience.

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies.

Europe PMC requires Javascript to function effectively.

Either your web browser doesn't support Javascript or it is currently turned off. In the latter case, please turn on Javascript support in your web browser and reload this page.

Search life-sciences literature (43,815,450 articles, preprints and more)

- Available from publisher site using DOI. A subscription may be required. Full text

- Citations & impact

- Similar Articles

Rigour in qualitative case-study research.

Author information, affiliations.

- Houghton C 1

ORCIDs linked to this article

- Houghton C | 0000-0003-3740-1564

Nurse Researcher , 01 Mar 2013 , 20(4): 12-17 https://doi.org/10.7748/nr2013.03.20.4.12.e326 PMID: 23520707

Abstract

Data sources, full text links .

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.7748/nr2013.03.20.4.12.e326

Citations & impact

Impact metrics, citations of article over time, alternative metrics.

Smart citations by scite.ai Smart citations by scite.ai include citation statements extracted from the full text of the citing article. The number of the statements may be higher than the number of citations provided by EuropePMC if one paper cites another multiple times or lower if scite has not yet processed some of the citing articles. Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been supported or disputed. https://scite.ai/reports/10.7748/nr2013.03.20.4.12.e326

Article citations, practitioner perspectives on the use of acceptance and commitment therapy for bereavement support: a qualitative study..

Willi N , Pancoast A , Drikaki I , Gu X , Gillanders D , Finucane A

BMC Palliat Care , 23(1):59, 28 Feb 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38418964 | PMCID: PMC10900636

Factors affecting Accountable Care Organizations' decisions to remain in or exit the Medicare Shared Savings Program following Pathways to Success.

Ying M , Forman JH , Murali S , Gauntlett LE , Krein SL , Hollenbeck BK , Hollingsworth JM

Health Aff Sch , 2(1):qxad093, 05 Jan 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38313161 | PMCID: PMC10830425

Conceptualising the empowerment of caregivers raising children with developmental disabilities in Ethiopia: a qualitative study.

Szlamka Z , Ahmed I , Genovesi E , Kinfe M , Hoekstra RA , Hanlon C

BMC Health Serv Res , 23(1):1420, 15 Dec 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38102602 | PMCID: PMC10722818

A qualitative study of infection prevention and control practices in the maternal units of two Ghanaian hospitals.

Sunkwa-Mills G , Senah K , Breinholdt M , Aberese-Ako M , Tersbøl BP

Antimicrob Resist Infect Control , 12(1):125, 13 Nov 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 37953285 | PMCID: PMC10641978

Unveiling the obstacles encountered by women doctors in the Pakistani healthcare system: A qualitative investigation.

Raza A , Jauhar J , Abdul Rahim NF , Memon U , Matloob S

PLoS One , 18(10):e0288527, 05 Oct 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 37796908 | PMCID: PMC10553294

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Qualitative case study data analysis: an example from practice.

Houghton C , Murphy K , Shaw D , Casey D

Nurse Res , 22(5):8-12, 01 May 2015

Cited by: 12 articles | PMID: 25976531

Evidence-based care: enhancing the rigour of a qualitative study.

Br J Nurs , 17(20):1286-1289, 01 Nov 2008

Cited by: 18 articles | PMID: 19043334

Using Framework Analysis in nursing research: a worked example.

Ward DJ , Furber C , Tierney S , Swallow V

J Adv Nurs , 69(11):2423-2431, 21 Mar 2013

Cited by: 142 articles | PMID: 23517523

Methodological rigour within a qualitative framework.

Tobin GA , Begley CM

J Adv Nurs , 48(4):388-396, 01 Nov 2004

Cited by: 284 articles | PMID: 15500533

Establishing methodological rigour in international qualitative nursing research: a case study from Ghana.

Mill JE , Ogilvie LD

J Adv Nurs , 41(1):80-87, 01 Jan 2003

Cited by: 16 articles | PMID: 12519291

Europe PMC is part of the ELIXIR infrastructure

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 28 March 2019

Attempting rigour and replicability in thematic analysis of qualitative research data; a case study of codebook development

- Kate Roberts 1 ,

- Anthony Dowell 2 &

- Jing-Bao Nie 3

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 19 , Article number: 66 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

107k Accesses

289 Citations

30 Altmetric

Metrics details

Navigating the world of qualitative thematic analysis can be challenging. This is compounded by the fact that detailed descriptions of methods are often omitted from qualitative discussions. While qualitative research methodologies are now mature, there often remains a lack of fine detail in their description both at submitted peer reviewed article level and in textbooks. As one of research’s aims is to determine the relationship between knowledge and practice through the demonstration of rigour, more detailed descriptions of methods could prove useful. Rigour in quantitative research is often determined through detailed explanation allowing replication, but the ability to replicate is often not considered appropriate in qualitative research. However, a well described qualitative methodology could demonstrate and ensure the same effect.

This article details the codebook development which contributed to thematic analysis of qualitative data. This analysis formed part of a mixed methods multiphase design research project, with both qualitative and quantitative inquiry and involving the convergence of data and analyses. This design consisted of three distinct phases: quantitative, qualitative and implementation phases.

Results and conclusions

This article is aimed at researchers and doctoral students new to thematic analysis by describing a framework to assist their processes. The detailed description of the methods used supports attempts to utilise the thematic analysis process and to determine rigour to support the establishment of credibility. This process will assist practitioners to be confident that the knowledge and claims contained within research are transferable to their practice. The approach described within this article builds on, and enhances, current accepted models.

Peer Review reports

Navigating the world of thematic qualitative analysis can be challenging. Thematic analysis is a straightforward way of conducting hermeneutic content analysis which is from a group of analyses that are designed for non-numerical data. It is a form of pattern recognition used in content analysis whereby themes (or codes) that emerge from the data become the categories for analysis. These forms of analysis state that the material as a whole is understood by studying the parts, but the parts cannot be understood except in relation to the whole [ 1 ]. The process involves the identification of themes with relevance specific to the research focus, the research question, the research context and the theoretical framework. This approach allows data to be both described and interpreted for meaning.

In qualitative research replication of thematic analysis methods can be challenging given that many articles omit a detailed overview of qualitative process; this makes it difficult for a novice researcher to effectively mirror analysis strategies and processes and for experienced researchers to fully understand the rigour of the study. Even though descriptions of code book development exists in the literature [ 2 , 3 ] there continues to be significant debate about what constitutes reliability and rigor in relation to qualitative coding [ 1 ]. In fact, the idea of demonstration of rigour and reliability is often overlooked or only briefly discussed creating difficulties for replication.

Research aims to determine the relationship between knowledge and practice through the demonstration of rigour, validity and reliability. This combination helps determine the trustworthiness of a project. This is often determined through detailed explanations of methods allowing replication and thus the application of findings, but the ability to replicate is often not considered appropriate in qualitative research. However, general consensus states that all research should be open to critique, which includes the integrity of the assumptions and conclusions reached [ 4 ]. That considered, a well described qualitative methodology utilising some components of quantitative frameworks could potentially have the same effect.

When research is aimed at informing clinical practice, determining trustworthiness is as an important step to ensure applicability and utility [ 5 ]. It is suggested that validity, one component of trustworthiness in qualitative research, can be established by investigating three main aspects: content (sampling frame and instrument development description); criterion-related (comparison and testing of the instrument and analysis tools between researchers, e.g. inter-rater or inter-coder testing); and, construct validity (appropriateness of data-led inferences to the research question using reflexive techniques) [ 4 ]. It would thus seem then that determining the validity, or ‘trustworthiness’, can be best achieved by a detailed and reflexive account of procedures and methods, allowing the readers to see how the lines of inquiry have led to particular conclusions [ 6 ].

Whilst the development of a codebook is not considered a time efficient mode for analysis [ 2 ], it enables a discussion and possibility of replication within qualitative methods utilising what could be considered a quantitative tool. It also allows reliability testing to be more easily applied. The codebook development discussed in this article formed part of a mixed methods multiphase design research project (mentioned throughout as the “case study”) with the overarching aims of identifying barriers and enhancing facilitators to communication between two health provider groups. The discussion of demonstration of codebook development will include examples from the PhD research project, and whilst a full discussion of the project is not within the scope of this article some background will assist in a grounding of the discussion.

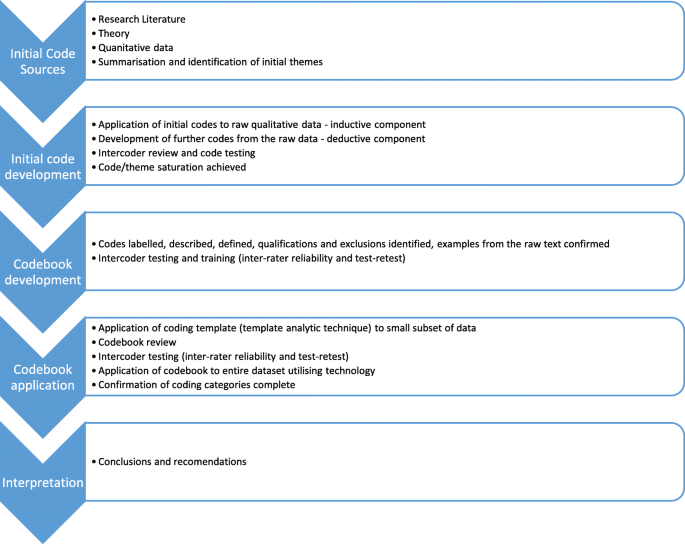

This research project was a mixed methods multiphase design project, with both qualitative and quantitative inquiry and involving the convergence of data and analyses. This design consisted of three distinct phases: quantitative, qualitative and implementation phases. This project’s qualitative thematic analysis utilised the dualistic technique of inductive and deductive thematic analysis informed by the work of Fereday and Muir-Cochrane which included the development and description of an analytical codebook [ 7 ]. (See Fig. 1 for the process followed in the coding process) The deductive component involved the creation of a preliminary codebook to help guide the analysis. This was based on the research question being asked, the initial analysis of the literature, the quantitative survey undertaken as part of the project and a preliminary scan of the raw interview data [ 8 ]. Additionally, the inductive approach followed the creation of the codebook. This allowed for any unexpected themes to develop during the coding process [ 9 ]. Deductive approaches are based on the assumption that there are ‘laws’ or principles that can be applied to the phenomenon. Insight was thus derived from the application of the deductive model to the set of information and searching for consistencies and anomalies. Conversely, inductive approaches searched for patterns from the ‘facts’ or raw data [ 9 ]. This allowed for any unexpected themes with the potential to provide further useful analysis of the data to develop during the coding process. Combining these approaches allowed the development of patterns from the unknown parts that may fall outside the predictive codes of deductive reasoning and allowed for a more complete analysis.

- Process of code creation and testing

This combined inductive/deductive approach fits well with both a mixed methods style of methodology and a pragmatic epistemology underpinning, whereby the methods are chosen by the researcher to be best able to answer the research questions. A critical realism ontological approach also meant that while the deductive approach provided an initial sound grounding, the creator of the codebook needed to include an inductive process to allow the reality of others to be clearly represented in the data analysis.

The goal of this article therefore is to highlight the difficulties of the demonstration of rigour in qualitative thematic analysis. It does this by investigating the assumption which states that replicability is not seen as necessary in qualitative research. It then continues this conversation by showing the process of a codebook development and its use as a means of analysing interview data, using a case study and real world data. It also aims to clearly discuss the approach to determining rigour and validly within thematic analysis as part of a research project. The description of analysis is embedded within the philosophical standpoint of critical realism and pragmatism, which adds depth to the utilisation of these methods in previous discussions [ 2 , 7 ]. The clear description of the coding and reliability testing used in this analysis will assist replication and will support researchers and doctoral students hoping to demonstrate rigour in similar studies.

This case study was a project investigating the development of effective communication and collaboration tools between acupuncturists and general practitioners (GPs). A GP (sometimes known as a family doctor or family practice physician) is a medical physician whose practice is not orientated to a specific medical speciality but covers a variety of medical problems in patients of all ages [ 10 ]. The rationale for this project was the fact that the landscape for patient treatment is changing, and rather than rely solely on their GP’s advice, patients are making their own decisions about choice of treatment. Increasing numbers of patients are using complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) either as an adjunct, or as an alternative to standard mainstream care [ 11 ].

There are multiple reasons for the increase in CAM use cited in the literature including dissatisfaction with the biomedical model, increased perceived efficacy of CAM and an increase in training and practice of CAM therapies including biomedical appropriation of CAM skills [ 12 ]. Increasingly patients believe a combined approach of CAM and conventional medicine is better than either on its own, and more and more patients have the desire to discuss CAM with well-informed GPs [ 13 ].

Patient’s extensive use of CAM has the potential to impact doctor-patient communication. Even with the increase in CAM use and a desire to discuss this, up to 77% of patients do not disclose their CAM use to their general practitioners, and GPs tend to underestimate patients use of CAM and may not ask about it [ 14 ]. When CAM is discussed, GPs are being asked about the safety and effectiveness of CAM either on its own or as an adjunct, and additionally many patients have an expectation that their GP will be able to discuss and/or refer to a CAM practitioner [ 15 ].

Communication gaps identified in both the research and evidenced in clinical practice formed the basis of this research questions. The specific questions asked were:

What is the current communication and collaboration between general practitioners and acupuncturists or CAM?

What are the barriers to communication between General Practice and Acupuncture or CAM?

How can communication be improved between General Practice and Acupuncture or CAM?

Does communication and collaboration differ in the landscape of mental health? And if so, why?

The mixed methods project utilised both survey and interview techniques to extrapolate data from the two participant groups (acupuncturists and general practitioners). The research aimed to evaluate and define current practice in order to develop effective strategies to connect the two groups. The tools and strategies allow clinical utility and transferability to other similar clinical groups. Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the The University of Otago Ethics Committee, and additionally the Ngai Tahu Research Consultation Committee approved the research and considered it of importance to Maori health.

The case study example within this article was part of a mixed method project which contained a qualitative approach to interpreting interview data using thematic analysis. It is the analysis of the qualitative component of this study that forms the basis of the discussion contained herewith. These types of qualitative analyses posit that reality consists of people’s subjective experiences or interpretations of the world. Therefore, there is no singular correct pathway to knowledge. This mode of analysis suggests a way to understand meaning or try to make sense out of textual data which may be somewhat unclear. Knowledge is derived from the field through a semi-structured examination of the phenomenon being explored. Thus there is no objective knowledge which is independent of thinking [ 16 ].

The case example utilised a codebook as part of the thematic analysis. A codebook is a tool to assist analysis of large qualitative data sets. It defines codes and themes by giving detailed descriptions and restrictions on what can be included within a code, and provides concrete examples of each code. A code is often a word or short phrase that symbolically assigns a summative, salient, essence-capturing, or attribute for a portion of data [ 17 ]. The use of a codebook was deemed appropriate to allow for the testing of interpretations of the data, and to allow for demonstration of rigour within the project.

Study population

The study population consisted of GPs in current practice registered with the Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners, and Acupuncturists in current practice registered with either the New Zealand Register of Acupuncturists or the New Zealand Acupuncture Standards Authority. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Sample size

The recommendation for sampling size when investigating the phenomena surrounding experience is six participants [ 18 ]. However Guest suggests that thematic saturation is more likely to occur with a sample of twelve [ 19 ]. Therefore a group of 27 (14 GPs and 13 acupuncturists) were invited to participate in the semi structured interviews.

Maximum variation purposeful sampling was used for participant recruitment to allow for the exploration of the common and unique manifestations of the target phenomenon and demographically varied cases [ 20 ]. Demographic norms were mirrored where possible in the sampling technique with regard to sex, age, ethnicity and type and location of practice. This type of sampling is non-random and is based on the researcher’s viewpoint that the participants selected will provide insightful and penetrating information regarding the research question. Participants initially self-selected by indicating a willingness to be interviewed during the survey phase of this project, and further participants were targeted to meet demographic subsets.

Rationale of choice of methods

Semi-structured interviews, utilised in this case study, draw on aspects of descriptive research which allow a comprehensive summary of events in everyday terms, and allow for in-depth exploration of a specific phenomenon. The aim is to understand phenomena through meanings that people assign to them [ 21 ]. Through the ability to investigate this descriptive data, new perspectives, concepts and themes may be uncovered. During analysis researchers stay close to the data and there is no ability to prove causal effects. Although the inquiry may be value-bound, the researcher aims through the adoption of their ontological and epistemological lens to identify a range of beliefs without introducing bias from their own world view.

These descriptive techniques explored the range of attitudes, perceptions, beliefs and behaviours from the sample and ensured subsequent discussions and proposed interventions were applicable and appropriate to both GPs and acupuncturists. The qualitative data obtained from the semi structured interviews refined and explained the numerical and statistical results from earlier components of the study through a more in-depth exploration.

Developing the codebook and stages of data coding and testing

The development, use and testing of codebooks is not often reported in qualitative research reports, and rarely in enough detail for replication of the process. The decision to use and test a codebook was important in the demonstration of rigour in this project, as it allowed a clear trail of evidence for the validity of the study and also allowed ease of inter-rater reliability testing of the data. The combination of the inductive/deductive approach described earlier to codebook development meant that the codebook, in this instance, was deduced a priori from the initial search of the literature, the quantitative survey and the initial read of the raw interview data. The preliminary codebook underwent many iterations through the inductive process before the final version was agreed upon by the researchers. (The process of the codebook development is represented in Fig. 1 ). The utilisation of a codebook allowed a more refined, focused and efficient analysis of the raw data in subsequent reads [ 8 ]. The testing of reliability of codes was complex in the context of qualitative research as it could be seen as borrowing a concept from quantitative research and applying it to qualitative research. Yet when adopting the critical realist lens, it is acknowledged that interpretation would be difficult to infer to a wider group without establishing some line of reliability between testers. As this project was aimed directly at practical utility of its findings, the testing approach seemed appropriate.

Summarising the data and identifying initial themes

Following the literature review and suggestion of themes for inclusion in the early codebook a priori, the first read of a sample of the raw data was undertaken. The first read of the data involved highlighting text or ‘codable’ units that the researcher considered may become a ‘codable’ moment. Comments were inserted into the margins with initial thoughts and ideas.

This was then done again using the literature informed codes as a guide to determine whether more codable units fitted within the early codebook, or whether further codes needed to be added to the analytical framework.

Examples of each theme, subtheme and code continued to be reviewed and moved until agreement between the coders as to what determined sufficient demonstration of a true representation of a theme became evident. This involved reading and re reading the subset of transcripts multiple times until theme saturation was achieved. Reoccurring themes were identified, but not necessarily given credence over stand out single comments that really embodied a theme.

Codes were written following the guidelines of Boyatzis [ 9 ] and were classified with the following: label, definition, description, qualifications or exclusions and examples from the raw data. An example of code labels from this research is outlined in Table 1 below.

Applying a template of codes and additional coding

Once the codebook was in a draft form it was applied to a larger data set. This was repeated in an iterative way using the early codebook as a guide to determine whether most codable units fitted within the code guide or whether further codes needed to be added to the analytical framework. Once this was done multiple times with no new codes emerging the codebook was assumed as a valid representation of the data.

Utilising technology: connecting the codes and identifying themes

At this stage the raw data was then transferred into Nvivo software program [ 22 ] to allow for a systematic coding approach with the identified codes being added as nodes, and the coded text being matched to the nodes in a systematic way. This allowed for sorting, clustering and comparison of codes between and within subgroups.

Corroborating and legitimating coded themes

Approaches used for codebook structure analysis were chunking and displaying [ 8 ]. Chunking refers to examining chunks of text that are interrelated and are used for analysis in relation to the research questions and hypotheses. Displaying data is another technique for discovering connections using maps and matrices to contextualise relationships between categories and concepts. Both these approaches allowed for legitimising analysis and to assist in the process of interpretation.

Testing the reliability of the code

Although inter-rater code testing and discussion occurred throughout the codebook development stage, the final codebook continued to be tested for inter-rater reliability before the data reached the interpretation stage. Reliability can be described as the consistency of judgement that protects against or lessens the contamination of projection [ 9 ]. Reliability was tested in this project in two ways:

Consistency of judgment over absence and presence (test-retest reliability); and

Consistency of judgement across various viewers (inter-rater reliability).

Both tests were checked for reliability using this formula suggested by Miles and Huberman [ 23 ]:

This calculation is a much cruder tool than Choen’s kappa, but gives a simple measure of agreement as a percentage value and is able to be applied to small data sets with a high number of variables. As a rule of thumb, the minimum percentage to demonstrate adequate levels of agreement is 75% [ 17 ]. Less than this indicates an inadequate level of agreement.

Inter-rater reliability was tested initially using nominal comparisons of absence or presence of a set of themes and frequency of observation of a single theme (see Table 2 ). This detailed approach to testing of agreement between coders is not always carried out and/or reported whereas it is suggested here as a necessary step. This continued to be tested, with disagreements being recorded, but minimal changes to the codebook were made at this stage unless it was deemed absolutely necessary as the codebook was now deemed to be in its final version. This was in keeping with the critical realism philosophy that states that various realities are possible, and the pragmatic approach which states that there is no one correct way to code a data set. When all coders were in agreement, these sections of data were determined to be key representations of the code. Where more than one, but not a unanimous agreement was made, this section of data would be discussed between coders. When only one coder applied a section of data to a specific code, this was assumed not to be a clear representation of the code.

Examples of how reliability testing was undertaken can be found in Tables 2 and 3 . Once inter-rater testing had been analysed the coding of the data set was seen as complete and key themes and codes were identified and formed the basis for the discussion in relation to the research questions posed. While absolute agreement was not reached, discussion of coding differences continued to inform the codebook development until all coders agreed that the results were reflective of the data. Of interest here, is that even with this detailed and reflexive process undertaken, the final inter-rater calculations still fell below adequate rates of agreement. However, this clear transparency of the process informed the interpretations and from this, conclusions and recommendations were drawn in relation to the research.

Limitations of this method

A key limitation of codebook development is the extensive time required to establish the codebook itself and to train coders in the use of the codebook. Utilisation of a codebook often requires many revisions and iterations during the code development process before coder agreement can be reached. Even then, and as demonstrated by this project, full inter-coder reliability is unlikely to be achieved. Additionally, application of statistical testing, such as kappa coefficients, would require large volumes of data and analysis is unlikely to be undertaken within most qualitative projects. As was the case with this project, as the code number increases the percentage of agreement decreases during calculation. It is therefore unclear whether this form of analysis would reach a different end point to that of other forms of content analysis. To effectively establish this, a comparison of analysis of the same data using different techniques is recommended for future research projects. However, clear guidelines of qualitative methodological processes will strengthen interpretability and applicability of results.

There are also considerable limitations to the utilisation of the percentage agreement calculation of coders. Frequently one category or code is clearer than others. Thus there is likely to be considerable agreement between the two coders about data in this category. Another problem is that the procedure does not take into account that they are expected to agree solely by chance. A correction for this problem is to use a Kappa statistic to measure the agreement between coders. However, as previously mentioned, the more variables and the larger the data set the more problematic this calculation becomes.

Projection is another limitation of this thematic analysis approach. The stronger a researcher’s ideology the more tempted they will be to project. Projection can be reduced through the development of an explicit code and enabling consistency of judgement through inter-rater reliability. It is also necessary to remain close to the raw information during the development of themes and codes [ 9 ]. However, due to the likelihood of different ideologies of coders, it is likely that this will have an impact of the ability to achieve adequate reliability.

Another limitation in thematic analysis can be sampling and the limited scope provided through the use of convenience sampling. In this study the random sample accessed for the quantitative survey did not yield enough voluntary participants for the in-depth interviews hence the sampling framework was modified to purposive convenience sampling. Demographic data was collected to allow for comparison to the larger sample of survey participants and also to the census and workforce survey data carried out nationwide [ 24 , 25 ]. These demographic comparisons need to be explicitly transparent. In this type of study, the sampling will need to always be a convenience sample. This is because a true random sample is unlikely to be feasible as it is necessary for the interviewee to be willing to participate and this usually involves an interest in the subject or in research itself. This may give a somewhat skewed view within the results which must be taken into account in the analysis.

Conclusions

This article has provided a detailed and honest account of the difficulties in demonstrating rigour in thematic analysis of qualitative data. However, the researchers involved in this project found the development and utilisation of a codebook, and the application by a team of researchers of the codebook to the data to be advantageous albeit time consuming. It was thought that the codebook improved the potential for inter-coder agreement and reliability testing and ensured an accurate description of analyses. The approach was consistent with the ontological and epistemological framework which informed the study and allowed the unique perspectives highlighted whilst maintaining integrity of analysis. Whilst the creation of the codebook was time intensive, there is the assurance of a demonstration of rigour and reliability within the process. This article has outlined the steps involved in the process of thematic analysis used in this project and helps to describe the rigour demonstrated within the qualitative component of this mixed methods study. This article does not attempt to present an analysis of the data in relation to the research question, but rather provides a clear description of the process undertaken in a qualitative data analysis framework. This article explains and explores the use of Fereday and Muir-Cochranes’ hybrid approach to analysis which combines deductive and inductive coding whilst embedding it in a differing philosophical standpoint [ 7 ]. The clear description of the coding and reliability testing processes used in this analysis can be replicated and will support researchers wishing to demonstrate rigour in similar studies. We recommend that others embarking on qualitative analysis as a team embrace and enhance the concept of codebook development to guide complex analytical processes.

Abbreviations

Complementary and alternative medicine

General practitioner

Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, editors. Sage handbook of mixed methods in Social & Behavioral Research. 2nd ed: SAGE publications; 2010.

Decuir-Gunby JT, Marshall PL, Mcculloch AW. Developing and using a codebook for the analysis of interview data: an example from a professional development research project. Field methods. 2011;23:136–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X10388468 .

Article Google Scholar

Fonteyn ME, Vettese M, Lancaster DR, Bauer-Wu S. Developing a codebook to guide content analysis of expressive writing transcripts. Appl Nurs Res. 2008;21:165–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2006.08.005 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Long T, Johnson M. Rigour, reliability and validity in qualitative research. Clin Eff Nurs. 2000;4:30–7. https://doi.org/10.1054/cein.2000.0106 .

Porter S, Dipn BP. Validity, trustworthiness and rigour: reasserting realism in qualitative research. J Adv Nurs. 2007;60:79–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04360.x .

Seale C. The quality of qualitative research; 1999. https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857020093 .

Book Google Scholar

Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods. 2006;5:80–92.

Crabtree BF, Miller WL (William L. Doing qualitative research. Sage Publications; 1999.

Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information : thematic analysis and code development. Thousand oaks CA: SAGE Publications; 1998.

general practitioner. (n.d.). Medical Dictionary for the Health Professions and Nursing. 2012. https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/general+practitioner . Accessed 13 Jan 2019.

Harris PE, Cooper KL, Relton C, Thomas KJ. Prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use by the general population: a systematic review and update. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66:924–39.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Hollenberg D. Uncharted ground: patterns of professional interaction among complementary/alternative and biomedical practitioners in integrative health care settings. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:731–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.030 .

Jong MC, van de Vijver L, Busch M, Fritsma J, Seldenrijk R. Integration of complementary and alternative medicine in primary care: what do patients want? Patient Educ Couns. 2012;89:417–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.08.013 .

Ben-Arye E, Frenkel M. Referring to complementary and alternative medicine--a possible tool for implementation. Complement Ther Med. 2008;16:325–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2008.02.008 .

Roberts K, Nie JB, Dowell T. From knowing silence to curious engagement: the role of general practitioners to discuss and refer to complementary and alternative medicine. J Interprofessional Educ Pract. 2017;9:104–7.

Gephart R. Paradigms and Research Methods Researh Methods Forum. Summer. 2012;4(1999):1–8.

Google Scholar

Saldaña J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd; 2009.

Morse JM. Determining sample size. Qual Health Res. 2000;10:3–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973200129118183 .

Guest G. How many interviews are enough?: an experiment with data saturation and variability. Field methods. 2006;18:59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903 .

Sandelowski M. Sample size in qualitative research. Res Nurs Health. 1995;18:179–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.4770180211 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Deetz S. Crossroads—describing differences in approaches to organization science: rethinking Burrell and Morgan and Their legacy. Organ Sci. 1996;7:191–207. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.7.2.191 .

QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo qualitative data analysis software. 2015.

Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1994.

Statistics New Zealand. New Zealand Census of Population and Dwellings. 2013.

The Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners. GP Workforce Survey. 2015.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

no funding received as part of this study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Primary Health Care & General Practice, University of Otago, Wellington, New Zealand

Kate Roberts

Anthony Dowell

Bioethics Centre, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand

Jing-Bao Nie

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Conception or design of the work KR, TD, JN. Data collection KR. Data analysis and interpretation KR Drafting the article KR. Critical revision of the article KR, TD, JN. Final approval of the version to be published KR, TD, JN.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kate Roberts .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The University of Otago Ethics Committee approved the survey and interviews for this study, and additionally the Ngai Tahu Research Consultation Committee approved the research and considered it of importance to Maori health.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Roberts, K., Dowell, A. & Nie, JB. Attempting rigour and replicability in thematic analysis of qualitative research data; a case study of codebook development. BMC Med Res Methodol 19 , 66 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0707-y

Download citation

Received : 27 August 2018

Accepted : 11 March 2019

Published : 28 March 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0707-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Thematic analysis

- Qualitative research

BMC Medical Research Methodology

ISSN: 1471-2288

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Technical advance

- Open access

- Published: 17 February 2018

Application of four-dimension criteria to assess rigour of qualitative research in emergency medicine

- Roberto Forero ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6031-6590 1 ,

- Shizar Nahidi 1 ,

- Josephine De Costa 1 ,

- Mohammed Mohsin 2 , 3 ,

- Gerry Fitzgerald 4 , 5 ,

- Nick Gibson 6 ,

- Sally McCarthy 5 , 7 &

- Patrick Aboagye-Sarfo 8

BMC Health Services Research volume 18 , Article number: 120 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

87k Accesses

238 Citations

15 Altmetric

Metrics details

The main objective of this methodological manuscript was to illustrate the role of using qualitative research in emergency settings. We outline rigorous criteria applied to a qualitative study assessing perceptions and experiences of staff working in Australian emergency departments.

We used an integrated mixed-methodology framework to identify different perspectives and experiences of emergency department staff during the implementation of a time target government policy. The qualitative study comprised interviews from 119 participants across 16 hospitals. The interviews were conducted in 2015–2016 and the data were managed using NVivo version 11. We conducted the analysis in three stages, namely: conceptual framework, comparison and contrast and hypothesis development. We concluded with the implementation of the four-dimension criteria (credibility, dependability, confirmability and transferability) to assess the robustness of the study,

We adapted four-dimension criteria to assess the rigour of a large-scale qualitative research in the emergency department context. The criteria comprised strategies such as building the research team; preparing data collection guidelines; defining and obtaining adequate participation; reaching data saturation and ensuring high levels of consistency and inter-coder agreement.

Based on the findings, the proposed framework satisfied the four-dimension criteria and generated potential qualitative research applications to emergency medicine research. We have added a methodological contribution to the ongoing debate about rigour in qualitative research which we hope will guide future studies in this topic in emergency care research. It also provided recommendations for conducting future mixed-methods studies. Future papers on this series will use the results from qualitative data and the empirical findings from longitudinal data linkage to further identify factors associated with ED performance; they will be reported separately.

Peer Review reports

Qualitative research methods have been used in emergency settings in a variety of ways to address important problems that cannot be explored in another way, such as attitudes, preferences and reasons for presenting to the emergency department (ED) versus other type of clinical services (i.e., general practice) [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ].

The methodological contribution of this research is part of the ongoing debate of scientific rigour in emergency care, such as the importance of qualitative research in evidence-based medicine, its contribution to tool development and policy evaluation [ 2 , 3 , 5 , 6 , 7 ]. For instance, the Four-Hour Rule and the National Emergency Access Target (4HR/NEAT) was an important policy implemented in Australia to reduce EDs crowding and boarding (access block) [ 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ]. This policy generated the right conditions for using mixed methods to investigate the impact of 4HR/NEAT policy implementation on people attending, working or managing this type of problems in emergency departments [ 2 , 3 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ].

The rationale of our study was to address the perennial question of how to assess and establish methodological robustness in these types of studies. For that reason, we conducted this mixed method study to explore the impact of the 4HR/NEAT in 16 metropolitan hospitals in four Australian states and territories, namely: Western Australia (WA), Queensland (QLD), New South Wales (NSW), and the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) [ 18 , 19 ].

The main objectives of the qualitative component was to understand the personal, professional and organisational perspectives reported by ED staff during the implementation of 4HR/NEAT, and to explore their perceptions and experiences associated with the implementation of the policy in their local environment.

This is part of an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NH&MRC) Partnership project to assess the impact of the 4HR/NEAT on Australian EDs. It is intended to complement the quantitative streams of a large data-linkage/dynamic modelling study using a mixed-methods approach to understand the impact of the implementation of the four-hour rule policy.

Methodological rigour

This section describes the qualitative methods to assess the rigour of the qualitative study. Researchers conducting quantitative studies use conventional terms such as internal validity, reliability, objectivity and external validity [ 17 ]. In establishing trustworthiness, Lincoln and Guba created stringent criteria in qualitative research, known as credibility, dependability, confirmability and transferability [ 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ]. This is referred in this article as “the Four-Dimensions Criteria” (FDC). Other studies have used different variations of these categories to stablish rigour [ 18 , 19 ]. In our case, we adapted the criteria point by point by selecting those strategies that applied to our study systematically. Table 1 illustrates which strategies were adapted in our study.

Study procedure

We carefully planned and conducted a series of semi-structured interviews based on the four-dimension criteria (credibility, dependability, confirmability and transferability) to assess and ensure the robustness of the study. These criteria have been used in other contexts of qualitative health research; but this is the first time it has been used in the emergency setting [ 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ].

Sampling and recruitment

We employed a combination of stratified purposive sampling (quota sampling), criterion-based and maximum variation sampling strategies to recruit potential participants [ 27 , 28 ]. The hospitals selected for the main longitudinal quantitative data linkage study, were also purposively selected in this qualitative component.

We targeted potential individuals from four groups, namely: ED Directors, ED physicians, ED nurses, and data/admin staff. The investigators identified local site coordinators who arranged the recruitment in each of the participating 16 hospitals (6 in NSW, 4 in QLD, 4 in WA and 2 in the ACT) and facilitated on-site access to the research team. These coordinators provided a list of potential participants for each professional group. By using this list, participants within each group were selected through purposive sampling technique. We initially planned to recruit at least one ED director, two ED physicians, two ED nurses and one data/admin staff per hospital. Invitation emails were circulated by the site coordinators to all potential participants who were asked to contact the main investigators if they required more information.

We also employed criterion-based purposive sampling to ensure that those with experience relating to 4HR/NEAT were eligible. For ethical on-site restrictions, the primary condition of the inclusion criteria was that eligible participants needed to be working in the ED during the period that the 4HR/NEAT policy was implemented. Those who were not working in that ED during the implementation period were not eligible to participate, even if they had previous working experience in other EDs.

We used maximum variation sampling to ensure that the sample reflects a diverse group in terms of skill level, professional experience and policy implementation [ 28 ]. We included study participants irrespective of whether their role/position was changed (for example, if they received a promotion during their term of service in ED).

In summary, over a period of 7 months (August 2015 to March 2016), we identified all the potential participants (124) and conducted 119 interviews (5 were unable to participate due to workload availability). The overall sample comprised a cohort of people working in different roles across 16 hospitals. Table 2 presents the demographic and professional characteristics of the participants.

Data collection

We employed a semi-structured interview technique. Six experienced investigators (3 in NSW, 1 in ACT, 1 in QLD and 1 in WA) conducted the interviews (117 face-to-face on site and 2 by telephone). We used an integrated interview protocol which consisted of a demographically-oriented question and six open-ended questions about different aspects of the 4HR/NEAT policy (see Additional file 1 : Appendix 1).

With the participant’s permission, interviews were audio-recorded. All the hospitals provided a quiet interview room that ensured privacy and confidentiality for participants and investigators.

All the interviews were transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriber with reference to a standardised transcription protocol [ 29 ]. The data analysis team followed a stepwise process for data cleaning, and de-identification. Transcripts were imported to qualitative data analysis software NVivo version 11 for management and coding [ 30 ].

Data analysis

The analyses were carried out in three stages. In the first stage, we identified key concepts using content analysis and a mind-mapping process from the research protocol and developed a conceptual framework to organise the data [ 31 ]. The analysis team reviewed and coded a selected number of transcripts, then juxtaposed the codes against the domains incorporated in the interview protocol as indicated in the three stages of analysis with the conceptual framework (Fig. 1 ).

Conceptual framework with the three stages of analysis used for the analysis of the qualitative data

In this stage, two cycles of coding were conducted: in the first one, all the transcripts were revised and initially coded, key concepts were identified throughout the full data set. The second cycle comprised an in-depth exploration and creation of additional categories to generate the codebook (see Additional file 2 : Appendix 2). This codebook was a summary document encompassing all the concepts identified as primary and subsequent levels. It presented hierarchical categorisation of key concepts developed from the domains indicated in Fig. 1 .

A summarised list of key concepts and their definitions are presented in Table 3 . We show the total number of interviews for each of the key concepts, and the number of times (i.e., total citations) a concept appeared in the whole dataset.

The second stage of analysis compared and contrasted the experiences, perspectives and actions of participants by role and location. The third and final stage of analysis aimed to generate theory-driven hypotheses and provided an in-depth understanding of the impact of the policy. At this stage, the research team explored different theoretical perspectives such as the carousel model and models of care approach [ 16 , 32 , 33 , 34 ]. We also used iterative sampling to reach saturation and interpret the findings.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was obtained for all participating hospitals and the qualitative methods are based on the original research protocol approved by the funding organisations [ 18 ].

This section described the FDC and provided a detailed description of the strategies used in the analysis. It was adapted from the FDC methodology described by Lincoln and Guba [ 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ] as the framework to ensure a high level of rigour in qualitative research. In Table 1 , we have provided examples of how the process was implemented for each criterion and techniques to ensure compliance with the purpose of FDC.

Credibility

Prolonged and varied engagement with each setting.

All the investigators had the opportunity to have a continued engagement with each ED during the data collection process. They received a supporting material package, comprising background information about the project; consent forms and the interview protocol (see Additional file 1 : Appendix 1). They were introduced to each setting by the local coordinator and had the chance to meet the ED directors and potential participants, They also identified local issues and salient characteristics of each site, and had time to get acquainted with the study’s participants. This process allowed the investigators to check their personal perspectives and predispositions, and enhance their familiarity with the study setting. This strategy also allowed participants to become familiar with the project and the research team.

Interviewing process and techniques

In order to increase credibility of the data collected and of the subsequent results, we took a further step of calibrating the level of awareness and knowledge of the research protocol. The research team conducted training sessions, teleconferences, induction meetings and pilot interviews with the local coordinators. Each of the interviewers conducted one or two pilot interviews to refine the overall process using the interview protocol, time-management and the overall running of the interviews.

The semi-structured interview procedure also allowed focus and flexibility during the interviews. The interview protocol (Additional file 1 : Appendix 1) included several prompts that allowed the expansion of answers and the opportunity for requesting more information, if required.

Establishing investigators’ authority

In relation to credibility, Miles and Huberman [ 35 ] expanded the concept to the trustworthiness of investigators’ authority as ‘human instruments’ and recommended the research team should present the following characteristics:

Familiarity with phenomenon and research context : In our study, the research team had several years’ experience in the development and implementation of 4HR/NEAT in Australian EDs and extensive ED-based research experience and track records conducting this type of work.

Investigative skills: Investigators who were involved in data collections had three or more years’ experience in conducting qualitative data collection, specifically individual interview techniques.

Theoretical knowledge and skills in conceptualising large datasets: Investigators had post-graduate experience in qualitative data analysis and using NVivo software to manage and qualitative research skills to code and interpret large amounts of qualitative data.

Ability to take a multidisciplinary approach: The multidisciplinary background of the team in public health, nursing, emergency medicine, health promotion, social sciences, epidemiology and health services research, enabled us to explore different theoretical perspectives and using an eclectic approach to interpret the findings.

These characteristics ensured that the data collection and content were consistent across states and participating hospitals.

Collection of referential adequacy materials

In accordance with Guba’s recommendation to collect any additional relevant resources, investigators maintained a separate set of materials from on-site data collection which included documents and field notes that provided additional information in relation to the context of the study, its findings and interpretation of results. These materials were collected and used during the different levels of data analysis and kept for future reference and secure storage of confidential material [ 26 ].

Peer debriefing

We conducted several sessions of peer debriefing with some of the Project Management Committee (PMC) members. They were asked at different stages throughout the analysis to reflect and cast their views on the conceptual analysis framework, the key concepts identified during the first level of analysis and eventually the whole set of findings (see Fig. 1 ). We also have reported and discussed preliminary methods and general findings at several scientific meetings of the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine.

Dependability

Rich description of the study protocol.

This study was developed from the early stages through a systematic search of the existing literature about the four-hour rule and time-target care delivery in ED. Detailed draft of the study protocol was delivered in consultation with the PMC. After incorporating all the comments, a final draft was generated for the purpose of obtaining the required ethics approvals for each ED setting in different states and territories.

To maintain consistency, we documented all the changes and revisions to the research protocol, and kept a trackable record of when and how changes were implemented.

Establishing an audit trail

Steps were taken to keep a track record of the data collection process [ 24 ]: we have had sustained communication within the research team to ensure the interviewers were abiding by an agreed-upon protocol to recruit participants. As indicated before, we provided the investigators with a supporting material package. We also instructed the interviewers on how to securely transfer the data to the transcriber. The data-analysis team systematically reviewed the transcripts against the audio files for accuracy and clarifications provided by the transcriber.

All the steps in coding the data and identification of key concepts were agreed upon by the research team. The progress of the data analysis was monitored on a weekly basis. Any modifications of the coding system were discussed and verified by the team to ensure correct and consistent interpretation throughout the analysis.

The codebook (see Additional file 2 : Appendix 2) was revised and updated during the cycles of coding. Utilisation of the mind-mapping process described above helped to verify consistency and allowed to determine how precise the participants’ original information was preserved in the coding [ 31 ].

As required by relevant Australian legislation [ 36 ], we maintained complete records of the correspondence and minutes of meetings, as well as all qualitative data files in NVivo and Excel on the administrative organisation’s secure drive. Back-up files were kept in a secure external storage device, for future access if required.

Stepwise replication—measuring the inter-coders’ agreement

To assess the interpretative rigour of the analysis, we applied inter-coder agreement to control the coding accuracy and monitor inter-coder reliability among the research team throughout the analysis stage [ 37 ]. This step was crucially important in the study given the changes of staff that our team experienced during the analysis stage. At the initial stages of coding, we tested the inter-coder agreement using the following protocol:

Step 1 – Two data analysts and principal investigator coded six interviews, separately.

Step 2 – The team discussed the interpretation of the emerging key concepts, and resolved any coding discrepancies.

Step 3 – The initial codebook was composed and used for developing the respective conceptual framework.

Step 4 – The inter-coder agreement was calculated and found a weighted Kappa coefficient of 0.765 which indicates a very good agreement (76.5%) of the data.

With the addition of a new analyst to the team, we applied another round of inter-coder agreement assessment. We followed the same steps to ensure the inter-coder reliability along the trajectory of data analysis, except for step 3—a priori codebook was used as a benchmark to compare and contrast the codes developed by the new analyst. The calculated Kappa coefficient 0.822 indicates a very good agreement of the data (See Table 4 ).

Confirmability

Reflexivity.

The analysis was conducted by the research team who brought different perspectives to the data interpretation. To appreciate the collective interpretation of the findings, each investigator used a separate reflexive journal to record the issues about sensitive topics or any potential ethical issues that might have affected the data analysis. These were discussed in the weekly meetings.

After completion of the data collection, reflection and feedback from all the investigators conducting the interviews were sought in both written and verbal format.

Triangulation

To assess the confirmability and credibility of the findings, the following four triangulation processes were considered: methodological, data source, investigators and theoretical triangulation.

Methodological triangulation is in the process of being implemented using the mixed methods approach with linked data from our 16 hospitals.

Data source triangulation was achieved by using several groups of ED staff working in different states/territories and performing different roles. This triangulation offered a broad source of data that contributed to gain a holistic understanding of the impact of 4HR/NEAT on EDs across Australia. We expect to use data triangulation with linked-data in future secondary analysis.

Investigators triangulation was obtained by consensus decision making though collaboration, discussion and participation of the team holding different perspectives. We also used the investigators’ field notes, memos and reflexive journals as a form of triangulation to validate the data collected. This approach enabled us to balance out the potential bias of individual investigators and enabling the research team to reach a satisfactory consensus level.

Theoretical triangulation was achieved by using and exploring different theoretical perspectives such as the carousel model and models of care approach [ 16 , 32 , 33 , 34 ]. that could be applied in the context of the study to generate hypotheses and theory driven codes [ 16 , 32 , 38 ].

Transferability

Purposive sampling to form a nominated sample.

As outlined in the methods section, we used a combination of three purposive sampling techniques to make sure that the selected participants were representative of the variety of views of ED staff across settings. This representativeness was critical for conducting comparative analysis across different groups.

Data saturation

We employed two methods to ensure data saturation was reached, namely: operational and theoretical. The operational method was used to quantify the number of new codes per interview over time. It indicates that the majority of codes were identified in the first interviews, followed by a decreasing frequency of codes identified from other interviews.

Theoretical saturation and iterative sampling were achieved through regular meetings where progress of coding and identification of variations in each of the key concepts were reported and discussed. We also used iterative sampling to reach saturation and interpret the findings. We continued this iterative process until no new codes emerged from the dataset and all the variations of an observed phenomenon were identified [ 39 ] (Fig. 2 ).

Data saturation gain per interview added based on the chronological order of data collection in the hospitals. Y axis = number of new codes, X axis = number of interviews over time

Scientific rigour in qualitative research assessing trustworthiness is not new. Qualitative researchers have used rigour criteria widely [ 40 , 41 , 42 ]. The novelty of the method described in this article rests on the systematic application of these criteria in a large-scale qualitative study in the context of emergency medicine.

According to the FDC, similar findings should be obtained if the process is repeated with the same cohort of participants in the same settings and organisational context. By employing the FDC and the proposed strategies, we could enhance the dependability of the findings. As indicated in the literature, qualitative research has many times been questioned in history for its validity and credibility [ 3 , 20 , 43 , 44 ].

Nevertheless, if the work is done properly, based on the suggested tools and techniques, any qualitative work can become a solid piece of evidence. This study suggests that emergency medicine researchers can improve their qualitative research if conducted according to the suggested criteria. The triangulation and reflexivity strategies helped us to minimise the investigators’ bias, and affirm that the findings were objective and accurately reflect the participants’ perspectives and experiences. Abiding by a consistent method of data collection (e.g., interview protocol) and conducting the analysis with a team of investigators, helped us minimise the risk of interpretation bias.

Employing several purposive sampling techniques enabled us to have a diverse range of opinions and experiences which at the same time enhanced the credibility of the findings. We expect that the outcomes of this study will show a high degree of applicability, because any resultant hypotheses may be transferable across similar settings in emergency care. The systematic quantification of data saturation at this scale of qualitative data has not been demonstrated in the emergency medicine literature before.

As indicated, the objective of this study was to contribute to the ongoing debate about rigour in qualitative research by using our mixed methods study as an example. In relation to innovative application of mixed-methods, the findings from this qualitative component can be used to explain specific findings from the quantitative component of the study. For example, different trends of 4HR/NEAT performance can be explained by variations in staff relationships across states (see key concept 1, Table 3 ). In addition, some experiences from doctors and nurses may explain variability of performance indicators across participating hospitals. The robustness of the qualitative data will allow us to generate hypotheses that in turn can be tested in future research.

Careful planning is essential in any type of research project which includes the importance of allocating sufficient resources both human and financial. It is also required to organise precise arrangements for building the research team; preparing data collection guidelines; defining and obtaining adequate participation. This may allow other researchers in emergency care to replicate the use of the FDC in the future.

This study has several limitations. Some limitations of the qualitative component include recall bias or lack of reliable information collected about interventions conducted in the past (before the implementation of the policy). As Weber and colleagues [ 45 ] point out, conducting interviews with clinicians at a single point in time may be affected by recall bias. Moreover, ED staff may have left the organisation or have progressed in their careers (from junior to senior clinical roles, i.e. junior nursing staff or junior medical officers, registrars, etc.), so obtaining information about pre/during/post-4HR/NEAT was a difficult undertaking. Although the use of criterion-based and maximum-variation sampling techniques minimised this effect, we could not guarantee that the sampling techniques could have reached out all those who might be eligible to participate.

In terms of recruitment, we could not select potential participants who were not working in that particular ED during the implementation, even if they had previous working experience in other hospital EDs. This is a limitation because people who participated in previous hospitals during the intervention could not provide valuable input to the overall project.

In addition, one would claim that the findings could have been ‘ED-biased’ due to the fact that we did not interview the staff or administrators outside the ED. Unfortunately, interviews outside the ED were beyond the resources and scope of the project.

With respect to the rigour criteria, we could not carry out a systematic member checking as we did not have the required resources for such an expensive follow-up. Nevertheless, we have taken extensive measures to ensure confirmation of the integrity of the data.

Conclusions

The FDC presented in this manuscript provides an important and systematic approach to achieve trustworthy qualitative findings. As indicated before, qualitative research credentials have been questioned. However, if the work is done properly based on the suggested tools and techniques described in this manuscript, any work can become a very notable piece of evidence. This study concludes that the FDC is effective; any investigator in emergency medicine research can improve their qualitative research if conducted accordingly.

Important indicators such as saturation levels and inter-coder reliability should be considered in all types of qualitative projects. One important aspect is that by using FDC we can demonstrate that qualitative research is not less rigorous than quantitative methods.

We also conclude that the FDC is a valid framework to be used in qualitative research in the emergency medicine context. We recommend that future research in emergency care should consider the FDC to achieve trustworthy qualitative findings. We can conclude that our method confirms the credibility (validity) and dependability (reliability) of the analysis which are a true reflection of the perspectives reported by the group of participants across different states/territories.

We can also conclude that our method confirms the objectivity of the analyses and reduces the risk for interpretation bias. We encourage adherence to practical frameworks and strategies like those presented in this manuscript.

Finally, we have highlighted the importance of allocating sufficient resources. This is essential if other researchers in emergency care would like to replicate the use of the FDC in the future.

Following papers in this series will use the empirical findings from longitudinal data linkage analyses and the results from the qualitative study to further identify factors associated with ED performance before and after the implementation of the 4HR/NEAT.

Abbreviations

Four Hour Rule/National Emergency Access Target

Australian Capital Territory

Emergency department(s)

Four-Dimensions Criteria

Health Research Ethics Committee

New South Wales

Project Management Committee

Western Australia

Rees N, Rapport F, Snooks H. Perceptions of paramedics and emergency staff about the care they provide to people who self-harm: constructivist metasynthesis of the qualitative literature. J Psychosom Res. 2015;78(6):529–35.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Jessup M, Crilly J, Boyle J, Wallis M, Lind J, Green D, Fitzgerald G. Users’ experiences of an emergency department patient admission predictive tool: a qualitative evaluation. Health Inform J. 2016;22(3):618–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/1460458215577993 .

Article Google Scholar

Choo EK, Garro AC, Ranney ML, Meisel ZF, Morrow Guthrie K. Qualitative research in emergency care part I: research principles and common applications. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(9):1096–102.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hjortdahl M, Halvorsen P, Risor MB. Rural GPs’ attitudes toward participating in emergency medicine: a qualitative study. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2016;34(4):377–84.

Samuels-Kalow ME, Rhodes KV, Henien M, Hardy E, Moore T, Wong F, Camargo CA Jr, Rizzo CT, Mollen C. Development of a patient-centered outcome measure for emergency department asthma patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(5):511–22.

Manning SN. A multiple case study of patient journeys in Wales from A&E to a hospital ward or home. Br J Community Nurs. 2016;21(10):509–17.

Ranney ML, Meisel ZF, Choo EK, Garro AC, Sasson C, Morrow Guthrie K. Interview-based qualitative research in emergency care part II: data collection, analysis and results reporting. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(9):1103–12.

Forero R, Hillman KM, McCarthy S, Fatovich DM, Joseph AP, Richardson DB. Access block and ED overcrowding. Emerg Med Australas. 2010;22(2):119–35.

Fatovich DM. Access block: problems and progress. Med J Aust. 2003;178(10):527–8.

PubMed Google Scholar

Richardson DB. Increase in patient mortality at 10 days associated with emergency department overcrowding. Med J Aust. 2006;184(5):213–6.

Sprivulis PC, Da Silva J-A, Jacobs IG, Frazer ARL, Jelinek GA. The association between hospital overcrowding and mortality among patients admitted via Western Australian emergency departments.[Erratum appears in Med J Aust. 2006 Jun 19;184(12):616]. Med J Aust. 2006;184(5):208–12.

Richardson DB, Mountain D. Myths versus facts in emergency department overcrowding and hospital access block. Med J Aust. 2009;190(7):369–74.

Geelhoed GC, de Klerk NH. Emergency department overcrowding, mortality and the 4-hour rule in Western Australia. Med J Aust. 2012;196(2):122–6.