Is it time to get rid of homework? Mental health experts weigh in.

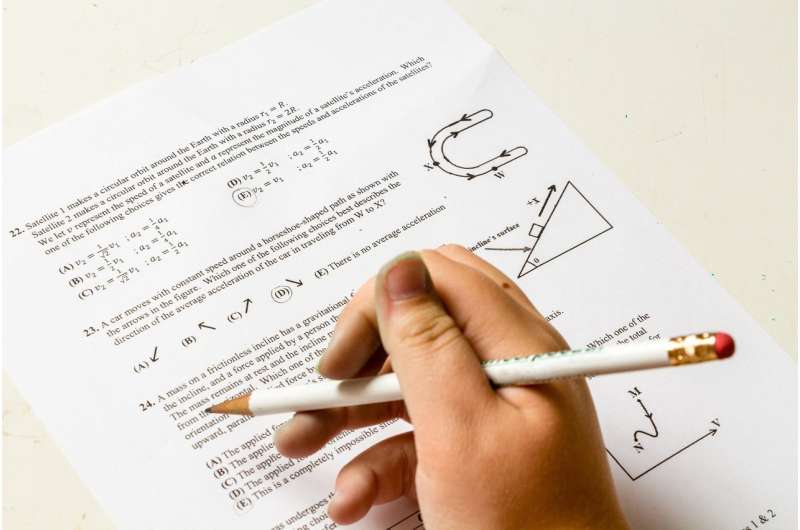

It's no secret that kids hate homework. And as students grapple with an ongoing pandemic that has had a wide range of mental health impacts, is it time schools start listening to their pleas about workloads?

Some teachers are turning to social media to take a stand against homework.

Tiktok user @misguided.teacher says he doesn't assign it because the "whole premise of homework is flawed."

For starters, he says, he can't grade work on "even playing fields" when students' home environments can be vastly different.

"Even students who go home to a peaceful house, do they really want to spend their time on busy work? Because typically that's what a lot of homework is, it's busy work," he says in the video that has garnered 1.6 million likes. "You only get one year to be 7, you only got one year to be 10, you only get one year to be 16, 18."

Mental health experts agree heavy workloads have the potential do more harm than good for students, especially when taking into account the impacts of the pandemic. But they also say the answer may not be to eliminate homework altogether.

Emmy Kang, mental health counselor at Humantold , says studies have shown heavy workloads can be "detrimental" for students and cause a "big impact on their mental, physical and emotional health."

"More than half of students say that homework is their primary source of stress, and we know what stress can do on our bodies," she says, adding that staying up late to finish assignments also leads to disrupted sleep and exhaustion.

Cynthia Catchings, a licensed clinical social worker and therapist at Talkspace , says heavy workloads can also cause serious mental health problems in the long run, like anxiety and depression.

And for all the distress homework can cause, it's not as useful as many may think, says Dr. Nicholas Kardaras, a psychologist and CEO of Omega Recovery treatment center.

"The research shows that there's really limited benefit of homework for elementary age students, that really the school work should be contained in the classroom," he says.

For older students, Kang says, homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night.

"Most students, especially at these high achieving schools, they're doing a minimum of three hours, and it's taking away time from their friends, from their families, their extracurricular activities. And these are all very important things for a person's mental and emotional health."

Catchings, who also taught third to 12th graders for 12 years, says she's seen the positive effects of a no-homework policy while working with students abroad.

"Not having homework was something that I always admired from the French students (and) the French schools, because that was helping the students to really have the time off and really disconnect from school," she says.

The answer may not be to eliminate homework completely but to be more mindful of the type of work students take home, suggests Kang, who was a high school teacher for 10 years.

"I don't think (we) should scrap homework; I think we should scrap meaningless, purposeless busy work-type homework. That's something that needs to be scrapped entirely," she says, encouraging teachers to be thoughtful and consider the amount of time it would take for students to complete assignments.

The pandemic made the conversation around homework more crucial

Mindfulness surrounding homework is especially important in the context of the past two years. Many students will be struggling with mental health issues that were brought on or worsened by the pandemic , making heavy workloads even harder to balance.

"COVID was just a disaster in terms of the lack of structure. Everything just deteriorated," Kardaras says, pointing to an increase in cognitive issues and decrease in attention spans among students. "School acts as an anchor for a lot of children, as a stabilizing force, and that disappeared."

But even if students transition back to the structure of in-person classes, Kardaras suspects students may still struggle after two school years of shifted schedules and disrupted sleeping habits.

"We've seen adults struggling to go back to in-person work environments from remote work environments. That effect is amplified with children because children have less resources to be able to cope with those transitions than adults do," he explains.

'Get organized' ahead of back-to-school

In order to make the transition back to in-person school easier, Kang encourages students to "get good sleep, exercise regularly (and) eat a healthy diet."

To help manage workloads, she suggests students "get organized."

"There's so much mental clutter up there when you're disorganized. ... Sitting down and planning out their study schedules can really help manage their time," she says.

Breaking up assignments can also make things easier to tackle.

"I know that heavy workloads can be stressful, but if you sit down and you break down that studying into smaller chunks, they're much more manageable."

If workloads are still too much, Kang encourages students to advocate for themselves.

"They should tell their teachers when a homework assignment just took too much time or if it was too difficult for them to do on their own," she says. "It's good to speak up and ask those questions. Respectfully, of course, because these are your teachers. But still, I think sometimes teachers themselves need this feedback from their students."

More: Some teachers let their students sleep in class. Here's what mental health experts say.

More: Some parents are slipping young kids in for the COVID-19 vaccine, but doctors discourage the move as 'risky'

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

News and Media

- News & Media Home

- Research Stories

- School's In

- In the Media

You are here

More than two hours of homework may be counterproductive, research suggests.

A Stanford education researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter. "Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good," wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education . The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students' views on homework. Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year. Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night. "The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students' advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being," Pope wrote. Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school. Their study found that too much homework is associated with: • Greater stress : 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor. • Reductions in health : In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems. • Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits : Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were "not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills," according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy. A balancing act The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills. Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as "pointless" or "mindless" in order to keep their grades up. "This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points," said Pope, who is also a co-founder of Challenge Success , a nonprofit organization affiliated with the GSE that conducts research and works with schools and parents to improve students' educational experiences.. Pope said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said. "Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development," wrote Pope. High-performing paradox In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. "Young people are spending more time alone," they wrote, "which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities." Student perspectives The researchers say that while their open-ended or "self-reporting" methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for "typical adolescent complaining" – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe. The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Clifton B. Parker is a writer at the Stanford News Service .

More Stories

⟵ Go to all Research Stories

Get the Educator

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

Improving lives through learning

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

- About the Hub

- Announcements

- Faculty Experts Guide

- Subscribe to the newsletter

Explore by Topic

- Arts+Culture

- Politics+Society

- Science+Technology

- Student Life

- University News

- Voices+Opinion

- About Hub at Work

- Gazette Archive

- Benefits+Perks

- Health+Well-Being

- Current Issue

- About the Magazine

- Past Issues

- Support Johns Hopkins Magazine

- Subscribe to the Magazine

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Credit: August de Richelieu

Does homework still have value? A Johns Hopkins education expert weighs in

Joyce epstein, co-director of the center on school, family, and community partnerships, discusses why homework is essential, how to maximize its benefit to learners, and what the 'no-homework' approach gets wrong.

By Vicky Hallett

The necessity of homework has been a subject of debate since at least as far back as the 1890s, according to Joyce L. Epstein , co-director of the Center on School, Family, and Community Partnerships at Johns Hopkins University. "It's always been the case that parents, kids—and sometimes teachers, too—wonder if this is just busy work," Epstein says.

But after decades of researching how to improve schools, the professor in the Johns Hopkins School of Education remains certain that homework is essential—as long as the teachers have done their homework, too. The National Network of Partnership Schools , which she founded in 1995 to advise schools and districts on ways to improve comprehensive programs of family engagement, has developed hundreds of improved homework ideas through its Teachers Involve Parents in Schoolwork program. For an English class, a student might interview a parent on popular hairstyles from their youth and write about the differences between then and now. Or for science class, a family could identify forms of matter over the dinner table, labeling foods as liquids or solids. These innovative and interactive assignments not only reinforce concepts from the classroom but also foster creativity, spark discussions, and boost student motivation.

"We're not trying to eliminate homework procedures, but expand and enrich them," says Epstein, who is packing this research into a forthcoming book on the purposes and designs of homework. In the meantime, the Hub couldn't wait to ask her some questions:

What kind of homework training do teachers typically get?

Future teachers and administrators really have little formal training on how to design homework before they assign it. This means that most just repeat what their teachers did, or they follow textbook suggestions at the end of units. For example, future teachers are well prepared to teach reading and literacy skills at each grade level, and they continue to learn to improve their teaching of reading in ongoing in-service education. By contrast, most receive little or no training on the purposes and designs of homework in reading or other subjects. It is really important for future teachers to receive systematic training to understand that they have the power, opportunity, and obligation to design homework with a purpose.

Why do students need more interactive homework?

If homework assignments are always the same—10 math problems, six sentences with spelling words—homework can get boring and some kids just stop doing their assignments, especially in the middle and high school years. When we've asked teachers what's the best homework you've ever had or designed, invariably we hear examples of talking with a parent or grandparent or peer to share ideas. To be clear, parents should never be asked to "teach" seventh grade science or any other subject. Rather, teachers set up the homework assignments so that the student is in charge. It's always the student's homework. But a good activity can engage parents in a fun, collaborative way. Our data show that with "good" assignments, more kids finish their work, more kids interact with a family partner, and more parents say, "I learned what's happening in the curriculum." It all works around what the youngsters are learning.

Is family engagement really that important?

At Hopkins, I am part of the Center for Social Organization of Schools , a research center that studies how to improve many aspects of education to help all students do their best in school. One thing my colleagues and I realized was that we needed to look deeply into family and community engagement. There were so few references to this topic when we started that we had to build the field of study. When children go to school, their families "attend" with them whether a teacher can "see" the parents or not. So, family engagement is ever-present in the life of a school.

My daughter's elementary school doesn't assign homework until third grade. What's your take on "no homework" policies?

There are some parents, writers, and commentators who have argued against homework, especially for very young children. They suggest that children should have time to play after school. This, of course is true, but many kindergarten kids are excited to have homework like their older siblings. If they give homework, most teachers of young children make assignments very short—often following an informal rule of 10 minutes per grade level. "No homework" does not guarantee that all students will spend their free time in productive and imaginative play.

Some researchers and critics have consistently misinterpreted research findings. They have argued that homework should be assigned only at the high school level where data point to a strong connection of doing assignments with higher student achievement . However, as we discussed, some students stop doing homework. This leads, statistically, to results showing that doing homework or spending more minutes on homework is linked to higher student achievement. If slow or struggling students are not doing their assignments, they contribute to—or cause—this "result."

Teachers need to design homework that even struggling students want to do because it is interesting. Just about all students at any age level react positively to good assignments and will tell you so.

Did COVID change how schools and parents view homework?

Within 24 hours of the day school doors closed in March 2020, just about every school and district in the country figured out that teachers had to talk to and work with students' parents. This was not the same as homeschooling—teachers were still working hard to provide daily lessons. But if a child was learning at home in the living room, parents were more aware of what they were doing in school. One of the silver linings of COVID was that teachers reported that they gained a better understanding of their students' families. We collected wonderfully creative examples of activities from members of the National Network of Partnership Schools. I'm thinking of one art activity where every child talked with a parent about something that made their family unique. Then they drew their finding on a snowflake and returned it to share in class. In math, students talked with a parent about something the family liked so much that they could represent it 100 times. Conversations about schoolwork at home was the point.

How did you create so many homework activities via the Teachers Involve Parents in Schoolwork program?

We had several projects with educators to help them design interactive assignments, not just "do the next three examples on page 38." Teachers worked in teams to create TIPS activities, and then we turned their work into a standard TIPS format in math, reading/language arts, and science for grades K-8. Any teacher can use or adapt our prototypes to match their curricula.

Overall, we know that if future teachers and practicing educators were prepared to design homework assignments to meet specific purposes—including but not limited to interactive activities—more students would benefit from the important experience of doing their homework. And more parents would, indeed, be partners in education.

Posted in Voices+Opinion

You might also like

News network.

- Johns Hopkins Magazine

- Get Email Updates

- Submit an Announcement

- Submit an Event

- Privacy Statement

- Accessibility

Discover JHU

- About the University

- Schools & Divisions

- Academic Programs

- Plan a Visit

- my.JohnsHopkins.edu

- © 2024 Johns Hopkins University . All rights reserved.

- University Communications

- 3910 Keswick Rd., Suite N2600, Baltimore, MD

- X Facebook LinkedIn YouTube Instagram

Are You Down With or Done With Homework?

- Posted January 17, 2012

- By Lory Hough

The debate over how much schoolwork students should be doing at home has flared again, with one side saying it's too much, the other side saying in our competitive world, it's just not enough.

It was a move that doesn't happen very often in American public schools: The principal got rid of homework.

This past September, Stephanie Brant, principal of Gaithersburg Elementary School in Gaithersburg, Md., decided that instead of teachers sending kids home with math worksheets and spelling flash cards, students would instead go home and read. Every day for 30 minutes, more if they had time or the inclination, with parents or on their own.

"I knew this would be a big shift for my community," she says. But she also strongly believed it was a necessary one. Twenty-first-century learners, especially those in elementary school, need to think critically and understand their own learning — not spend night after night doing rote homework drills.

Brant's move may not be common, but she isn't alone in her questioning. The value of doing schoolwork at home has gone in and out of fashion in the United States among educators, policymakers, the media, and, more recently, parents. As far back as the late 1800s, with the rise of the Progressive Era, doctors such as Joseph Mayer Rice began pushing for a limit on what he called "mechanical homework," saying it caused childhood nervous conditions and eyestrain. Around that time, the then-influential Ladies Home Journal began publishing a series of anti-homework articles, stating that five hours of brain work a day was "the most we should ask of our children," and that homework was an intrusion on family life. In response, states like California passed laws abolishing homework for students under a certain age.

But, as is often the case with education, the tide eventually turned. After the Russians launched the Sputnik satellite in 1957, a space race emerged, and, writes Brian Gill in the journal Theory Into Practice, "The homework problem was reconceived as part of a national crisis; the U.S. was losing the Cold War because Russian children were smarter." Many earlier laws limiting homework were abolished, and the longterm trend toward less homework came to an end.

The debate re-emerged a decade later when parents of the late '60s and '70s argued that children should be free to play and explore — similar anti-homework wellness arguments echoed nearly a century earlier. By the early-1980s, however, the pendulum swung again with the publication of A Nation at Risk , which blamed poor education for a "rising tide of mediocrity." Students needed to work harder, the report said, and one way to do this was more homework.

For the most part, this pro-homework sentiment is still going strong today, in part because of mandatory testing and continued economic concerns about the nation's competitiveness. Many believe that today's students are falling behind their peers in places like Korea and Finland and are paying more attention to Angry Birds than to ancient Babylonia.

But there are also a growing number of Stephanie Brants out there, educators and parents who believe that students are stressed and missing out on valuable family time. Students, they say, particularly younger students who have seen a rise in the amount of take-home work and already put in a six- to nine-hour "work" day, need less, not more homework.

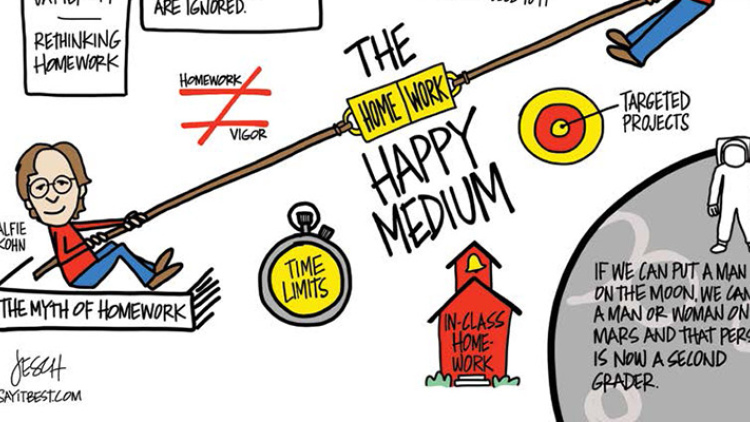

Who is right? Are students not working hard enough or is homework not working for them? Here's where the story gets a little tricky: It depends on whom you ask and what research you're looking at. As Cathy Vatterott, the author of Rethinking Homework , points out, "Homework has generated enough research so that a study can be found to support almost any position, as long as conflicting studies are ignored." Alfie Kohn, author of The Homework Myth and a strong believer in eliminating all homework, writes that, "The fact that there isn't anything close to unanimity among experts belies the widespread assumption that homework helps." At best, he says, homework shows only an association, not a causal relationship, with academic achievement. In other words, it's hard to tease out how homework is really affecting test scores and grades. Did one teacher give better homework than another? Was one teacher more effective in the classroom? Do certain students test better or just try harder?

"It is difficult to separate where the effect of classroom teaching ends," Vatterott writes, "and the effect of homework begins."

Putting research aside, however, much of the current debate over homework is focused less on how homework affects academic achievement and more on time. Parents in particular have been saying that the amount of time children spend in school, especially with afterschool programs, combined with the amount of homework given — as early as kindergarten — is leaving students with little time to run around, eat dinner with their families, or even get enough sleep.

Certainly, for some parents, homework is a way to stay connected to their children's learning. But for others, homework creates a tug-of-war between parents and children, says Liz Goodenough, M.A.T.'71, creator of a documentary called Where Do the Children Play?

"Ideally homework should be about taking something home, spending a few curious and interesting moments in which children might engage with parents, and then getting that project back to school — an organizational triumph," she says. "A nag-free activity could engage family time: Ask a parent about his or her own childhood. Interview siblings."

Instead, as the authors of The Case Against Homework write, "Homework overload is turning many of us into the types of parents we never wanted to be: nags, bribers, and taskmasters."

Leslie Butchko saw it happen a few years ago when her son started sixth grade in the Santa Monica-Malibu (Calif.) United School District. She remembers him getting two to four hours of homework a night, plus weekend and vacation projects. He was overwhelmed and struggled to finish assignments, especially on nights when he also had an extracurricular activity.

"Ultimately, we felt compelled to have Bobby quit karate — he's a black belt — to allow more time for homework," she says. And then, with all of their attention focused on Bobby's homework, she and her husband started sending their youngest to his room so that Bobby could focus. "One day, my younger son gave us 15-minute coupons as a present for us to use to send him to play in the back room. … It was then that we realized there had to be something wrong with the amount of homework we were facing."

Butchko joined forces with another mother who was having similar struggles and ultimately helped get the homework policy in her district changed, limiting homework on weekends and holidays, setting time guidelines for daily homework, and broadening the definition of homework to include projects and studying for tests. As she told the school board at one meeting when the policy was first being discussed, "In closing, I just want to say that I had more free time at Harvard Law School than my son has in middle school, and that is not in the best interests of our children."

One barrier that Butchko had to overcome initially was convincing many teachers and parents that more homework doesn't necessarily equal rigor.

"Most of the parents that were against the homework policy felt that students need a large quantity of homework to prepare them for the rigorous AP classes in high school and to get them into Harvard," she says.

Stephanie Conklin, Ed.M.'06, sees this at Another Course to College, the Boston pilot school where she teaches math. "When a student is not completing [his or her] homework, parents usually are frustrated by this and agree with me that homework is an important part of their child's learning," she says.

As Timothy Jarman, Ed.M.'10, a ninth-grade English teacher at Eugene Ashley High School in Wilmington, N.C., says, "Parents think it is strange when their children are not assigned a substantial amount of homework."

That's because, writes Vatterott, in her chapter, "The Cult(ure) of Homework," the concept of homework "has become so engrained in U.S. culture that the word homework is part of the common vernacular."

These days, nightly homework is a given in American schools, writes Kohn.

"Homework isn't limited to those occasions when it seems appropriate and important. Most teachers and administrators aren't saying, 'It may be useful to do this particular project at home,'" he writes. "Rather, the point of departure seems to be, 'We've decided ahead of time that children will have to do something every night (or several times a week). … This commitment to the idea of homework in the abstract is accepted by the overwhelming majority of schools — public and private, elementary and secondary."

Brant had to confront this when she cut homework at Gaithersburg Elementary.

"A lot of my parents have this idea that homework is part of life. This is what I had to do when I was young," she says, and so, too, will our kids. "So I had to shift their thinking." She did this slowly, first by asking her teachers last year to really think about what they were sending home. And this year, in addition to forming a parent advisory group around the issue, she also holds events to answer questions.

Still, not everyone is convinced that homework as a given is a bad thing. "Any pursuit of excellence, be it in sports, the arts, or academics, requires hard work. That our culture finds it okay for kids to spend hours a day in a sport but not equal time on academics is part of the problem," wrote one pro-homework parent on the blog for the documentary Race to Nowhere , which looks at the stress American students are under. "Homework has always been an issue for parents and children. It is now and it was 20 years ago. I think when people decide to have children that it is their responsibility to educate them," wrote another.

And part of educating them, some believe, is helping them develop skills they will eventually need in adulthood. "Homework can help students develop study skills that will be of value even after they leave school," reads a publication on the U.S. Department of Education website called Homework Tips for Parents. "It can teach them that learning takes place anywhere, not just in the classroom. … It can foster positive character traits such as independence and responsibility. Homework can teach children how to manage time."

Annie Brown, Ed.M.'01, feels this is particularly critical at less affluent schools like the ones she has worked at in Boston, Cambridge, Mass., and Los Angeles as a literacy coach.

"It feels important that my students do homework because they will ultimately be competing for college placement and jobs with students who have done homework and have developed a work ethic," she says. "Also it will get them ready for independently taking responsibility for their learning, which will need to happen for them to go to college."

The problem with this thinking, writes Vatterott, is that homework becomes a way to practice being a worker.

"Which begs the question," she writes. "Is our job as educators to produce learners or workers?"

Slate magazine editor Emily Bazelon, in a piece about homework, says this makes no sense for younger kids.

"Why should we think that practicing homework in first grade will make you better at doing it in middle school?" she writes. "Doesn't the opposite seem equally plausible: that it's counterproductive to ask children to sit down and work at night before they're developmentally ready because you'll just make them tired and cross?"

Kohn writes in the American School Board Journal that this "premature exposure" to practices like homework (and sit-and-listen lessons and tests) "are clearly a bad match for younger children and of questionable value at any age." He calls it BGUTI: Better Get Used to It. "The logic here is that we have to prepare you for the bad things that are going to be done to you later … by doing them to you now."

According to a recent University of Michigan study, daily homework for six- to eight-year-olds increased on average from about 8 minutes in 1981 to 22 minutes in 2003. A review of research by Duke University Professor Harris Cooper found that for elementary school students, "the average correlation between time spent on homework and achievement … hovered around zero."

So should homework be eliminated? Of course not, say many Ed School graduates who are teaching. Not only would students not have time for essays and long projects, but also teachers would not be able to get all students to grade level or to cover critical material, says Brett Pangburn, Ed.M.'06, a sixth-grade English teacher at Excel Academy Charter School in Boston. Still, he says, homework has to be relevant.

"Kids need to practice the skills being taught in class, especially where, like the kids I teach at Excel, they are behind and need to catch up," he says. "Our results at Excel have demonstrated that kids can catch up and view themselves as in control of their academic futures, but this requires hard work, and homework is a part of it."

Ed School Professor Howard Gardner basically agrees.

"America and Americans lurch between too little homework in many of our schools to an excess of homework in our most competitive environments — Li'l Abner vs. Tiger Mother," he says. "Neither approach makes sense. Homework should build on what happens in class, consolidating skills and helping students to answer new questions."

So how can schools come to a happy medium, a way that allows teachers to cover everything they need while not overwhelming students? Conklin says she often gives online math assignments that act as labs and students have two or three days to complete them, including some in-class time. Students at Pangburn's school have a 50-minute silent period during regular school hours where homework can be started, and where teachers pull individual or small groups of students aside for tutoring, often on that night's homework. Afterschool homework clubs can help.

Some schools and districts have adapted time limits rather than nix homework completely, with the 10-minute per grade rule being the standard — 10 minutes a night for first-graders, 30 minutes for third-graders, and so on. (This remedy, however, is often met with mixed results since not all students work at the same pace.) Other schools offer an extended day that allows teachers to cover more material in school, in turn requiring fewer take-home assignments. And for others, like Stephanie Brant's elementary school in Maryland, more reading with a few targeted project assignments has been the answer.

"The routine of reading is so much more important than the routine of homework," she says. "Let's have kids reflect. You can still have the routine and you can still have your workspace, but now it's for reading. I often say to parents, if we can put a man on the moon, we can put a man or woman on Mars and that person is now a second-grader. We don't know what skills that person will need. At the end of the day, we have to feel confident that we're giving them something they can use on Mars."

Read a January 2014 update.

Homework Policy Still Going Strong

Ed. Magazine

The magazine of the Harvard Graduate School of Education

Related Articles

Commencement Marshal Sarah Fiarman: The Principal of the Matter

Making Math “Almost Fun”

Alum develops curriculum to entice reluctant math learners

Reshaping Teacher Licensure: Lessons from the Pandemic

Olivia Chi, Ed.M.'17, Ph.D.'20, discusses the ongoing efforts to ensure the quality and stability of the teaching workforce

- Our Mission

Rethinking Homework for This Year—and Beyond

A schoolwide effort to reduce homework has led to a renewed focus on ensuring that all work assigned really aids students’ learning.

I used to pride myself on my high expectations, including my firm commitment to accountability for regular homework completion among my students. But the trauma of Covid-19 has prompted me to both reflect and adapt. Now when I think about the purpose and practice of homework, two key concepts guide me: depth over breadth, and student well-being.

Homework has long been the subject of intense debate, and there’s no easy answer with respect to its value. Teachers assign homework for any number of reasons: It’s traditional to do so, it makes students practice their skills and solidify learning, it offers the opportunity for formative assessment, and it creates good study habits and discipline. Then there’s the issue of pace. Throughout my career, I’ve assigned homework largely because there just isn’t enough time to get everything done in class.

A Different Approach

Since classes have gone online, the school where I teach has made a conscious effort as a teaching community to reduce, refine, and distill our curriculum. We have applied guiding questions like: What is most important? What is most transferable? What is most relevant? Refocusing on what matters most has inevitably made us rethink homework.

We have approached both asking and answering these questions through a science of learning lens. In Make It Stick: The Science of Successful Learning , the authors maintain that deep learning is slow learning. Deep learning requires time for retrieval, practice, feedback, reflection, and revisiting content; ultimately it requires struggle, and there is no struggle without time.

As someone who has mastered the curriculum mapping style of “get it done to move on to get that next thing done,” using an approach of “slow down and reduce” has been quite a shift for me. However, the shift has been necessary: What matters most is what’s best for my students, as opposed to my own plans or mandates imposed by others.

Listening to Students

To implement this shift, my high school English department has reduced content and texts both in terms of the amount of units and the content within each unit. We’re more flexible with dates and deadlines. We spend our energy planning the current unit instead of the year’s units. In true partnership with my students, I’m constantly checking in with them via Google forms, Zoom chats, conferences, and Padlet activities. In these check-ins, I specifically ask students how they’re managing the workload for my class and their other classes. I ask them how much homework they’re doing. And I adjust what I do and expect based on what they tell me. For example, when I find out a week is heavy with work in other classes, I make sure to allot more time during class for my tasks. At times I have even delayed or altered one of my assignments.

To be completely transparent, the “old” me is sheepish in admitting that I’ve so dramatically changed my thinking with respect to homework. However, both my students and I have reaped numerous benefits. I’m now laser-focused when designing every minute of my lessons to maximize teaching and learning. Every decision I make is now scrutinized through the lens of absolute worth for my students’ growth: If it doesn’t make the cut, it’s cut. I also take into account what is most relevant to my students.

For example, our 10th-grade English team has redesigned a unit that explores current manifestations of systemic oppression. This unit is new in approach and longer in duration than it was pre-Covid, and it has resulted in some of the deepest and hardest learning, as well as the richest conversations, that I have seen among students in my career. Part of this improved quality comes from the frequent and intentional pauses that I instruct students to take in order to reflect on the content and on the arc of their own learning. The reduction in content that we need to get through in online learning has given me more time to assign reflective prompts, and to let students process their thoughts, whether that’s at the end of a lesson as an exit slip or as an assignment.

Joining Forces to Be Consistent

There’s no doubt this reduction in homework has been a team effort. Within the English department, we have all agreed to allot reading time during class; across each grade level, we’re monitoring the amount of homework our students have collectively; and across the whole high school, we have adopted a framework to help us think through assigning homework.

Within that framework, teachers at the school agree that the best option is for students to complete all work during class. The next best option is for students to finish uncompleted class work at home as a homework assignment of less than 30 minutes. The last option—the one we try to avoid as much as possible—is for students to be assigned and complete new work at home (still less than 30 minutes). I set a maximum time limit for students’ homework tasks (e.g., 30 minutes) and make that clear at the top of every assignment.

This schoolwide approach has increased my humility as a teacher. In the past, I tended to think my subject was more important than everyone else’s, which gave me license to assign more homework. But now I view my students’ experience more holistically: All of their classes and the associated work must be considered, and respected.

As always, I ground this new pedagogical approach not just in what’s best for students’ academic learning, but also what’s best for them socially and emotionally. 2020 has been traumatic for educators, parents, and students. There is no doubt the level of trauma varies greatly ; however, one can’t argue with the fact that homework typically means more screen time when students are already spending most of the day on their devices. They need to rest their eyes. They need to not be sitting at their desks. They need physical activity. They need time to do nothing at all.

Eliminating or reducing homework is a social and emotional intervention, which brings me to the greatest benefit of reducing the homework load: Students are more invested in their relationship with me now that they have less homework. When students trust me to take their time seriously, when they trust me to listen to them and adjust accordingly, when they trust me to care for them... they trust more in general.

And what a beautiful world of learning can be built on trust.

The Cult of Homework

America’s devotion to the practice stems in part from the fact that it’s what today’s parents and teachers grew up with themselves.

America has long had a fickle relationship with homework. A century or so ago, progressive reformers argued that it made kids unduly stressed , which later led in some cases to district-level bans on it for all grades under seventh. This anti-homework sentiment faded, though, amid mid-century fears that the U.S. was falling behind the Soviet Union (which led to more homework), only to resurface in the 1960s and ’70s, when a more open culture came to see homework as stifling play and creativity (which led to less). But this didn’t last either: In the ’80s, government researchers blamed America’s schools for its economic troubles and recommended ramping homework up once more.

The 21st century has so far been a homework-heavy era, with American teenagers now averaging about twice as much time spent on homework each day as their predecessors did in the 1990s . Even little kids are asked to bring school home with them. A 2015 study , for instance, found that kindergarteners, who researchers tend to agree shouldn’t have any take-home work, were spending about 25 minutes a night on it.

But not without pushback. As many children, not to mention their parents and teachers, are drained by their daily workload, some schools and districts are rethinking how homework should work—and some teachers are doing away with it entirely. They’re reviewing the research on homework (which, it should be noted, is contested) and concluding that it’s time to revisit the subject.

Read: My daughter’s homework is killing me

Hillsborough, California, an affluent suburb of San Francisco, is one district that has changed its ways. The district, which includes three elementary schools and a middle school, worked with teachers and convened panels of parents in order to come up with a homework policy that would allow students more unscheduled time to spend with their families or to play. In August 2017, it rolled out an updated policy, which emphasized that homework should be “meaningful” and banned due dates that fell on the day after a weekend or a break.

“The first year was a bit bumpy,” says Louann Carlomagno, the district’s superintendent. She says the adjustment was at times hard for the teachers, some of whom had been doing their job in a similar fashion for a quarter of a century. Parents’ expectations were also an issue. Carlomagno says they took some time to “realize that it was okay not to have an hour of homework for a second grader—that was new.”

Most of the way through year two, though, the policy appears to be working more smoothly. “The students do seem to be less stressed based on conversations I’ve had with parents,” Carlomagno says. It also helps that the students performed just as well on the state standardized test last year as they have in the past.

Earlier this year, the district of Somerville, Massachusetts, also rewrote its homework policy, reducing the amount of homework its elementary and middle schoolers may receive. In grades six through eight, for example, homework is capped at an hour a night and can only be assigned two to three nights a week.

Jack Schneider, an education professor at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell whose daughter attends school in Somerville, is generally pleased with the new policy. But, he says, it’s part of a bigger, worrisome pattern. “The origin for this was general parental dissatisfaction, which not surprisingly was coming from a particular demographic,” Schneider says. “Middle-class white parents tend to be more vocal about concerns about homework … They feel entitled enough to voice their opinions.”

Schneider is all for revisiting taken-for-granted practices like homework, but thinks districts need to take care to be inclusive in that process. “I hear approximately zero middle-class white parents talking about how homework done best in grades K through two actually strengthens the connection between home and school for young people and their families,” he says. Because many of these parents already feel connected to their school community, this benefit of homework can seem redundant. “They don’t need it,” Schneider says, “so they’re not advocating for it.”

That doesn’t mean, necessarily, that homework is more vital in low-income districts. In fact, there are different, but just as compelling, reasons it can be burdensome in these communities as well. Allison Wienhold, who teaches high-school Spanish in the small town of Dunkerton, Iowa, has phased out homework assignments over the past three years. Her thinking: Some of her students, she says, have little time for homework because they’re working 30 hours a week or responsible for looking after younger siblings.

As educators reduce or eliminate the homework they assign, it’s worth asking what amount and what kind of homework is best for students. It turns out that there’s some disagreement about this among researchers, who tend to fall in one of two camps.

In the first camp is Harris Cooper, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University. Cooper conducted a review of the existing research on homework in the mid-2000s , and found that, up to a point, the amount of homework students reported doing correlates with their performance on in-class tests. This correlation, the review found, was stronger for older students than for younger ones.

This conclusion is generally accepted among educators, in part because it’s compatible with “the 10-minute rule,” a rule of thumb popular among teachers suggesting that the proper amount of homework is approximately 10 minutes per night, per grade level—that is, 10 minutes a night for first graders, 20 minutes a night for second graders, and so on, up to two hours a night for high schoolers.

In Cooper’s eyes, homework isn’t overly burdensome for the typical American kid. He points to a 2014 Brookings Institution report that found “little evidence that the homework load has increased for the average student”; onerous amounts of homework, it determined, are indeed out there, but relatively rare. Moreover, the report noted that most parents think their children get the right amount of homework, and that parents who are worried about under-assigning outnumber those who are worried about over-assigning. Cooper says that those latter worries tend to come from a small number of communities with “concerns about being competitive for the most selective colleges and universities.”

According to Alfie Kohn, squarely in camp two, most of the conclusions listed in the previous three paragraphs are questionable. Kohn, the author of The Homework Myth: Why Our Kids Get Too Much of a Bad Thing , considers homework to be a “reliable extinguisher of curiosity,” and has several complaints with the evidence that Cooper and others cite in favor of it. Kohn notes, among other things, that Cooper’s 2006 meta-analysis doesn’t establish causation, and that its central correlation is based on children’s (potentially unreliable) self-reporting of how much time they spend doing homework. (Kohn’s prolific writing on the subject alleges numerous other methodological faults.)

In fact, other correlations make a compelling case that homework doesn’t help. Some countries whose students regularly outperform American kids on standardized tests, such as Japan and Denmark, send their kids home with less schoolwork , while students from some countries with higher homework loads than the U.S., such as Thailand and Greece, fare worse on tests. (Of course, international comparisons can be fraught because so many factors, in education systems and in societies at large, might shape students’ success.)

Kohn also takes issue with the way achievement is commonly assessed. “If all you want is to cram kids’ heads with facts for tomorrow’s tests that they’re going to forget by next week, yeah, if you give them more time and make them do the cramming at night, that could raise the scores,” he says. “But if you’re interested in kids who know how to think or enjoy learning, then homework isn’t merely ineffective, but counterproductive.”

His concern is, in a way, a philosophical one. “The practice of homework assumes that only academic growth matters, to the point that having kids work on that most of the school day isn’t enough,” Kohn says. What about homework’s effect on quality time spent with family? On long-term information retention? On critical-thinking skills? On social development? On success later in life? On happiness? The research is quiet on these questions.

Another problem is that research tends to focus on homework’s quantity rather than its quality, because the former is much easier to measure than the latter. While experts generally agree that the substance of an assignment matters greatly (and that a lot of homework is uninspiring busywork), there isn’t a catchall rule for what’s best—the answer is often specific to a certain curriculum or even an individual student.

Given that homework’s benefits are so narrowly defined (and even then, contested), it’s a bit surprising that assigning so much of it is often a classroom default, and that more isn’t done to make the homework that is assigned more enriching. A number of things are preserving this state of affairs—things that have little to do with whether homework helps students learn.

Jack Schneider, the Massachusetts parent and professor, thinks it’s important to consider the generational inertia of the practice. “The vast majority of parents of public-school students themselves are graduates of the public education system,” he says. “Therefore, their views of what is legitimate have been shaped already by the system that they would ostensibly be critiquing.” In other words, many parents’ own history with homework might lead them to expect the same for their children, and anything less is often taken as an indicator that a school or a teacher isn’t rigorous enough. (This dovetails with—and complicates—the finding that most parents think their children have the right amount of homework.)

Barbara Stengel, an education professor at Vanderbilt University’s Peabody College, brought up two developments in the educational system that might be keeping homework rote and unexciting. The first is the importance placed in the past few decades on standardized testing, which looms over many public-school classroom decisions and frequently discourages teachers from trying out more creative homework assignments. “They could do it, but they’re afraid to do it, because they’re getting pressure every day about test scores,” Stengel says.

Second, she notes that the profession of teaching, with its relatively low wages and lack of autonomy, struggles to attract and support some of the people who might reimagine homework, as well as other aspects of education. “Part of why we get less interesting homework is because some of the people who would really have pushed the limits of that are no longer in teaching,” she says.

“In general, we have no imagination when it comes to homework,” Stengel says. She wishes teachers had the time and resources to remake homework into something that actually engages students. “If we had kids reading—anything, the sports page, anything that they’re able to read—that’s the best single thing. If we had kids going to the zoo, if we had kids going to parks after school, if we had them doing all of those things, their test scores would improve. But they’re not. They’re going home and doing homework that is not expanding what they think about.”

“Exploratory” is one word Mike Simpson used when describing the types of homework he’d like his students to undertake. Simpson is the head of the Stone Independent School, a tiny private high school in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, that opened in 2017. “We were lucky to start a school a year and a half ago,” Simpson says, “so it’s been easy to say we aren’t going to assign worksheets, we aren’t going assign regurgitative problem sets.” For instance, a half-dozen students recently built a 25-foot trebuchet on campus.

Simpson says he thinks it’s a shame that the things students have to do at home are often the least fulfilling parts of schooling: “When our students can’t make the connection between the work they’re doing at 11 o’clock at night on a Tuesday to the way they want their lives to be, I think we begin to lose the plot.”

When I talked with other teachers who did homework makeovers in their classrooms, I heard few regrets. Brandy Young, a second-grade teacher in Joshua, Texas, stopped assigning take-home packets of worksheets three years ago, and instead started asking her students to do 20 minutes of pleasure reading a night. She says she’s pleased with the results, but she’s noticed something funny. “Some kids,” she says, “really do like homework.” She’s started putting out a bucket of it for students to draw from voluntarily—whether because they want an additional challenge or something to pass the time at home.

Chris Bronke, a high-school English teacher in the Chicago suburb of Downers Grove, told me something similar. This school year, he eliminated homework for his class of freshmen, and now mostly lets students study on their own or in small groups during class time. It’s usually up to them what they work on each day, and Bronke has been impressed by how they’ve managed their time.

In fact, some of them willingly spend time on assignments at home, whether because they’re particularly engaged, because they prefer to do some deeper thinking outside school, or because they needed to spend time in class that day preparing for, say, a biology test the following period. “They’re making meaningful decisions about their time that I don’t think education really ever gives students the experience, nor the practice, of doing,” Bronke said.

The typical prescription offered by those overwhelmed with homework is to assign less of it—to subtract. But perhaps a more useful approach, for many classrooms, would be to create homework only when teachers and students believe it’s actually needed to further the learning that takes place in class—to start with nothing, and add as necessary.

Homework could have an impact on kids’ health. Should schools ban it?

Professor of Education, Penn State

Disclosure statement

Gerald K. LeTendre has received funding from the National Science Foundation and the Spencer Foundation.

Penn State provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation US.

View all partners

Reformers in the Progressive Era (from the 1890s to 1920s) depicted homework as a “sin” that deprived children of their playtime . Many critics voice similar concerns today.

Yet there are many parents who feel that from early on, children need to do homework if they are to succeed in an increasingly competitive academic culture. School administrators and policy makers have also weighed in, proposing various policies on homework .

So, does homework help or hinder kids?

For the last 10 years, my colleagues and I have been investigating international patterns in homework using databases like the Trends in Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) . If we step back from the heated debates about homework and look at how homework is used around the world, we find the highest homework loads are associated with countries that have lower incomes and higher social inequality.

Does homework result in academic success?

Let’s first look at the global trends on homework.

Undoubtedly, homework is a global phenomenon ; students from all 59 countries that participated in the 2007 Trends in Math and Science Study (TIMSS) reported getting homework. Worldwide, only less than 7% of fourth graders said they did no homework.

TIMSS is one of the few data sets that allow us to compare many nations on how much homework is given (and done). And the data show extreme variation.

For example, in some nations, like Algeria, Kuwait and Morocco, more than one in five fourth graders reported high levels of homework. In Japan, less than 3% of students indicated they did more than four hours of homework on a normal school night.

TIMSS data can also help to dispel some common stereotypes. For instance, in East Asia, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Japan – countries that had the top rankings on TIMSS average math achievement – reported rates of heavy homework that were below the international mean.

In the Netherlands, nearly one out of five fourth graders reported doing no homework on an average school night, even though Dutch fourth graders put their country in the top 10 in terms of average math scores in 2007.

Going by TIMSS data, the US is neither “ A Nation at Rest” as some have claimed, nor a nation straining under excessive homework load . Fourth and eighth grade US students fall in the middle of the 59 countries in the TIMSS data set, although only 12% of US fourth graders reported high math homework loads compared to an international average of 21%.

So, is homework related to high academic success?

At a national level, the answer is clearly no. Worldwide, homework is not associated with high national levels of academic achievement .

But, the TIMSS can’t be used to determine if homework is actually helping or hurting academic performance overall , it can help us see how much homework students are doing, and what conditions are associated with higher national levels of homework.

We have typically found that the highest homework loads are associated with countries that have lower incomes and higher levels of social inequality – not hallmarks that most countries would want to emulate.

Impact of homework on kids

TIMSS data also show us how even elementary school kids are being burdened with large amounts of homework.

Almost 10% of fourth graders worldwide (one in 10 children) reported spending multiple hours on homework each night. Globally, one in five fourth graders report 30 minutes or more of homework in math three to four times a week.

These reports of large homework loads should worry parents, teachers and policymakers alike.

Empirical studies have linked excessive homework to sleep disruption , indicating a negative relationship between the amount of homework, perceived stress and physical health.

What constitutes excessive amounts of homework varies by age, and may also be affected by cultural or family expectations. Young adolescents in middle school, or teenagers in high school, can study for longer duration than elementary school children.

But for elementary school students, even 30 minutes of homework a night, if combined with other sources of academic stress, can have a negative impact . Researchers in China have linked homework of two or more hours per night with sleep disruption .

Even though some cultures may normalize long periods of studying for elementary age children, there is no evidence to support that this level of homework has clear academic benefits . Also, when parents and children conflict over homework, and strong negative emotions are created, homework can actually have a negative association with academic achievement.

Should there be “no homework” policies?

Administrators and policymakers have not been reluctant to wade into the debates on homework and to formulate policies . France’s president, Francois Hollande, even proposed that homework be banned because it may have inegaliatarian effects.

However, “zero-tolerance” homework policies for schools, or nations, are likely to create as many problems as they solve because of the wide variation of homework effects. Contrary to what Hollande said, research suggests that homework is not a likely source of social class differences in academic achievement .

Homework, in fact, is an important component of education for students in the middle and upper grades of schooling.

Policymakers and researchers should look more closely at the connection between poverty, inequality and higher levels of homework. Rather than seeing homework as a “solution,” policymakers should question what facets of their educational system might impel students, teachers and parents to increase homework loads.

At the classroom level, in setting homework, teachers need to communicate with their peers and with parents to assure that the homework assigned overall for a grade is not burdensome, and that it is indeed having a positive effect.

Perhaps, teachers can opt for a more individualized approach to homework. If teachers are careful in selecting their assignments – weighing the student’s age, family situation and need for skill development – then homework can be tailored in ways that improve the chance of maximum positive impact for any given student.

I strongly suspect that when teachers face conditions such as pressure to meet arbitrary achievement goals, lack of planning time or little autonomy over curriculum, homework becomes an easy option to make up what could not be covered in class.

Whatever the reason, the fact is a significant percentage of elementary school children around the world are struggling with large homework loads. That alone could have long-term negative consequences for their academic success.

- Trends in Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS)

- Elementary school

- Academic success

Faculty of Law - Academic Appointment Opportunities

Operations Manager

Senior Education Technologist

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

share this!

August 16, 2021

Is it time to get rid of homework? Mental health experts weigh in

by Sara M Moniuszko

It's no secret that kids hate homework. And as students grapple with an ongoing pandemic that has had a wide-range of mental health impacts, is it time schools start listening to their pleas over workloads?

Some teachers are turning to social media to take a stand against homework .

Tiktok user @misguided.teacher says he doesn't assign it because the "whole premise of homework is flawed."

For starters, he says he can't grade work on "even playing fields" when students' home environments can be vastly different.

"Even students who go home to a peaceful house, do they really want to spend their time on busy work? Because typically that's what a lot of homework is, it's busy work," he says in the video that has garnered 1.6 million likes. "You only get one year to be 7, you only got one year to be 10, you only get one year to be 16, 18."

Mental health experts agree heavy work loads have the potential do more harm than good for students, especially when taking into account the impacts of the pandemic. But they also say the answer may not be to eliminate homework altogether.

Emmy Kang, mental health counselor at Humantold, says studies have shown heavy workloads can be "detrimental" for students and cause a "big impact on their mental, physical and emotional health."

"More than half of students say that homework is their primary source of stress, and we know what stress can do on our bodies," she says, adding that staying up late to finish assignments also leads to disrupted sleep and exhaustion.

Cynthia Catchings, a licensed clinical social worker and therapist at Talkspace, says heavy workloads can also cause serious mental health problems in the long run, like anxiety and depression.

And for all the distress homework causes, it's not as useful as many may think, says Dr. Nicholas Kardaras, a psychologist and CEO of Omega Recovery treatment center.

"The research shows that there's really limited benefit of homework for elementary age students, that really the school work should be contained in the classroom," he says.

For older students, Kang says homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night.

"Most students, especially at these high-achieving schools, they're doing a minimum of three hours, and it's taking away time from their friends from their families, their extracurricular activities. And these are all very important things for a person's mental and emotional health."

Catchings, who also taught third to 12th graders for 12 years, says she's seen the positive effects of a no homework policy while working with students abroad.

"Not having homework was something that I always admired from the French students (and) the French schools, because that was helping the students to really have the time off and really disconnect from school ," she says.

The answer may not be to eliminate homework completely, but to be more mindful of the type of work students go home with, suggests Kang, who was a high-school teacher for 10 years.

"I don't think (we) should scrap homework, I think we should scrap meaningless, purposeless busy work-type homework. That's something that needs to be scrapped entirely," she says, encouraging teachers to be thoughtful and consider the amount of time it would take for students to complete assignments.

The pandemic made the conversation around homework more crucial

Mindfulness surrounding homework is especially important in the context of the last two years. Many students will be struggling with mental health issues that were brought on or worsened by the pandemic, making heavy workloads even harder to balance.

"COVID was just a disaster in terms of the lack of structure. Everything just deteriorated," Kardaras says, pointing to an increase in cognitive issues and decrease in attention spans among students. "School acts as an anchor for a lot of children, as a stabilizing force, and that disappeared."

But even if students transition back to the structure of in-person classes, Kardaras suspects students may still struggle after two school years of shifted schedules and disrupted sleeping habits.

"We've seen adults struggling to go back to in-person work environments from remote work environments. That effect is amplified with children because children have less resources to be able to cope with those transitions than adults do," he explains.

'Get organized' ahead of back-to-school

In order to make the transition back to in-person school easier, Kang encourages students to "get good sleep, exercise regularly (and) eat a healthy diet."

To help manage workloads, she suggests students "get organized."

"There's so much mental clutter up there when you're disorganized... sitting down and planning out their study schedules can really help manage their time," she says.

Breaking assignments up can also make things easier to tackle.

"I know that heavy workloads can be stressful, but if you sit down and you break down that studying into smaller chunks, they're much more manageable."

If workloads are still too much, Kang encourages students to advocate for themselves.

"They should tell their teachers when a homework assignment just took too much time or if it was too difficult for them to do on their own," she says. "It's good to speak up and ask those questions. Respectfully, of course, because these are your teachers. But still, I think sometimes teachers themselves need this feedback from their students."

©2021 USA Today Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Explore further

Feedback to editors

Research team discovers more than 50 potentially new deep-sea species in one of the most unexplored areas of the planet

4 hours ago

New study details how starving cells hijack protein transport stations

New species of ant found pottering under the Pilbara named after Voldemort

5 hours ago

Searching for new asymmetry between matter and antimatter

Where have all the right whales gone? Researchers map population density to make predictions

Exoplanets true to size: New model calculations shows impact of star's brightness and magnetic activity

6 hours ago

Decoding the language of cells: Profiling the proteins behind cellular organelle communication

A new type of seismic sensor to detect moonquakes

7 hours ago

Macroalgae genetics study sheds light on how seaweed became multicellular

Africa's iconic flamingos threatened by rising lake levels, study shows

Relevant physicsforums posts, motivating high school physics students with popcorn physics.

Apr 3, 2024

How is Physics taught without Calculus?

Mar 29, 2024

Why are Physicists so informal with mathematics?

Mar 24, 2024

The changing physics curriculum in 1961

Suggestions for using math puzzles to stimulate my math students.

Mar 21, 2024

The New California Math Framework: Another Step Backwards?

Mar 14, 2024

More from STEM Educators and Teaching

Related Stories

Smartphones are lowering student's grades, study finds

Aug 18, 2020

Doing homework is associated with change in students' personality

Oct 6, 2017

Scholar suggests ways to craft more effective homework assignments

Oct 1, 2015

Should parents help their kids with homework?

Aug 29, 2019

How much math, science homework is too much?

Mar 23, 2015

Anxiety, depression, burnout rising as college students prepare to return to campus

Jul 26, 2021

Recommended for you

Earth, the sun and a bike wheel: Why your high-school textbook was wrong about the shape of Earth's orbit

Apr 8, 2024

Touchibo, a robot that fosters inclusion in education through touch

Apr 5, 2024

More than money, family and community bonds prep teens for college success: Study

Research reveals significant effects of onscreen instructors during video classes in aiding student learning

Mar 25, 2024

Prestigious journals make it hard for scientists who don't speak English to get published, study finds

Mar 23, 2024

Using Twitter/X to promote research findings found to have little impact on number of citations

Mar 22, 2024

Let us know if there is a problem with our content

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Phys.org in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

What’s the Right Amount of Homework? Many Students Get Too Little, Brief Argues

- Share article

Arguments against homework are well-documented, with some parents, teachers, and researchers saying these assignments put unnecessary stress on students and may not actually be helping them learn.

But a new article for the journal Education Next argues that many American students don’t have too much homework—they have too little.

Anxiety about overscheduled students with upwards of three or four hours of homework a night has overshadowed another problem, writes Janine Bempechat, a clinical professor of human development at the Boston University Wheelock College of Education and Human Development: Low-income students aren’t getting enough homework, and they may be suffering academically as a result.

“Eliminating homework is probably not as big a problem for high-income kids, because they have parents who will expose them to what they may not be getting after school,” Bempechat said in an interview with Education Week . “It’s lower-income students who are hurt the most when people argue that homework should be entirely eliminated.”

A widely endorsed metric for how much homework to assign is the 10-minute rule. It dictates that children should receive 10 minutes of homework per grade level—so a 1st grader would be given 10 minutes a day, while a senior in high school would have 120 minutes.

It’s hard to say exactly how closely American teachers hew to those guidelines. A 2013 study conducted by the University of Phoenix found that high school students are assigned about 3.5 hours of homework a night . But results from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s 2012 Programme for International Student Assessment found that 15-year-olds in the U.S. say they have much less than that—about six hours of homework a week .

But the averages obscure the range in assigned work between low-income and high-income students, Bempechat argues. According to the PISA results, disadvantaged students in the U.S. spend three hours less a week on homework than advantaged students (five hours versus eight hours).

Some students may be receiving even less than that. In interviews with low-income students at two low-performing high schools in northern California, Bempechat and her colleagues found that most students reported receiving what she called “minimal homework": “perhaps one or two worksheets or textbook pages, the occasional project, and 30 minutes of reading per night.”

This is a problem, she writes, because high-quality homework—the kind that allows students to problem solve and comes with clear instructions and strategies for working through difficult problems—helps students develop key academic skills. Some research supports this claim: In a 2004 study , researchers at Columbia University and Mississippi State University found that homework can prepare students with the perseverance they would need to hold jobs in the future.

The research on whether homework leads to increased academic achievement is mixed: a 2006 meta-analysis found that at-home assignments led to increased scores on some tests in some grades , but other studies show no relationship for elementary age students.

But goal-setting, self-regulation, and “resilience in the face of challenge” can all be learned through homework, said Bempechat. These skills only become more important as students progress into higher grades with greater expectations for learner autonomy, she said.

Some critics of homework raise concerns that assigning outside work puts low-income students at a disadvantage, because their parents may not be able to offer as much guidance as higher-income parents.

Bempechat writes that it’s more important that parents support homework completion rather than give hands-on help with assignments . She cites a 2014 study by researchers at the City University of New York that found that low-income parents providing structure around homework was a significant predictor of middle school students’ math grades .

But other barriers to home-based assignments persist for low-income students, including the “homework gap:" the inequality between students who have internet at home and those who don’t, and the difficulty that students without access face in completing assignments. About 40 percent of students didn’t have internet access at home as of 2015. But most teachers—70 percent—assign homework that requires connectivity, according to a 2016 survey from the Consortium for School Networking, a national association for school technology leaders.